#African women writers

Text

#African women#African Feminism#African women writers#African women thinkers#Black Women#African Women Scholars#African Women in Art#Radical African Women

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsha Hunt, circa 1970.

#marsha hunt#singer#model#writer#actress#brown sugar#mick jagger#the rolling stones#karis jagger#black is beautiful#1960s#1970s#black beauty#afro#black culture#black woman#black women#black actress#african american#rock & roll#music#vintage#photo#happy birthday#sbrown82

576 notes

·

View notes

Photo

bell hooks (deceased)

Gender: Female

Sexuality: Queer

DOB: 25 September 1952

RIP: 15 December 2021

Ethnicity: African American

Occupation: Writer, activist, professor

Note: Prefers her name to be in lowercase to honour her late grandmother.

#bell hooks#lgbt history#queerness#qwoc#queer women#female#queer#1952#rip#historical#black#poc#african american#writer#activist#teacher#academic#popular#popular post

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

All racism has ever done is slow down the creation of new beauty💜

🇺🇸👩🏾🦱📖

#history#phillis wheatley#poet#united states#boston#african american history#book#black girl magic#historical women#american revolution#female author#womens history#black writers#usa#women empowerment#african american women#girl power#england#black history#educated black women#black empowerment#historical figures#american colonies#american history#education#nickys facts

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

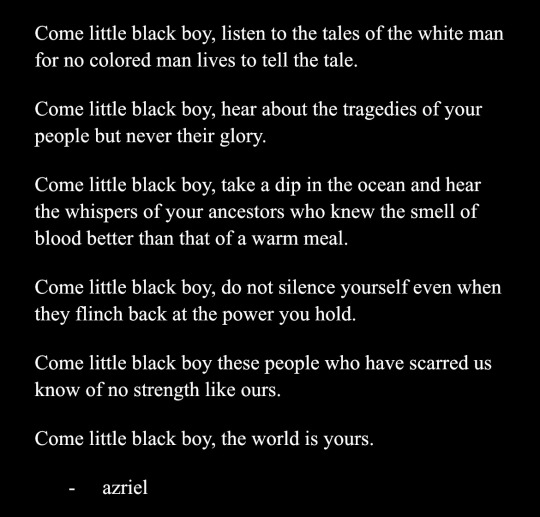

The World is Yours

"Bury me in the ocean, with my ancestors that jumped from the ships, because they knew death was better than bondage." Killmonger, Black Panther

Originally posted on TikTok: @/vitxate

#african american#girlblogging#poetry#young writer#young poets#writers and poets#poets on tumblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writeblr#writing#glory#tragedy#strength#black women#black men#beauty#anger#symbolism#freedom#greatness#all the beauty and the bloodshed#black boy magic#black girl magic#original poem#the world is yours

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Professional Afro-Hispanic Teen Author: where you can find my works

I have two ongoing novels releasing serialized updates.

One is a disability romance novel called "Damsel in the Red Dress" available here on Wattpad:

https://www.wattpad.com/story/365913868-damsel-in-the-red-dress

The other is a YA novel called "Rigamarole" available here on my Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/posts/103159083

#black authors#prize winning writers#teen writers#black writers#female writers#leyelle#my writing#hispanic authors#african american writers#rigamarole#teen authors#writeblr#black hispanic#dominican#Dominican girl#black girls#black girls of tumblr#black girls rock#black women#black girl magic#bookblr#authors#author#authors of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writer#fiction#romance novels#contemporary romance#romance book

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

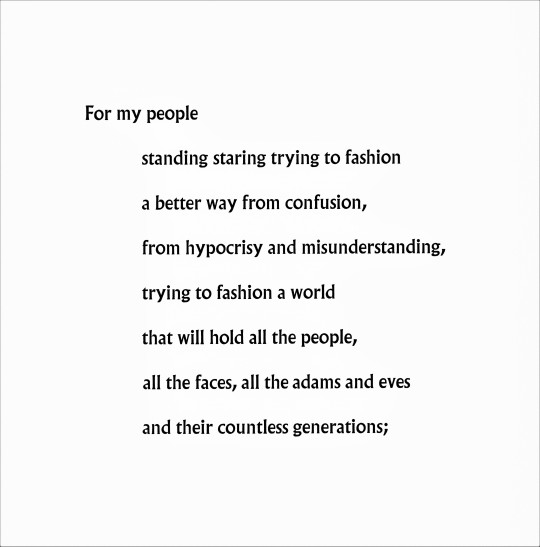

It’s Fine Press Friday!

This week we present a 1992 Limited Editions Club printing of American poet and writer Margaret Walker’s 1942 Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition-winning poem For My People with original lithographs by African American sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett, printed in a limited edition of 400 copies signed by the author and artist. The text was hand-set in Monotype Albertus and printed letterpress on Arches Cover paper by Michael and Winifred Bixler in Skaneateles, N. Y. and the lithographs were pulled by J.K. Fine Art Editions in Union City, N.J. Half the edition was bound at Jovonis Bookbindery in Springfield, Mass. and the other half at the Spectrum Bindery in southern California; we have no idea which binding we hold. But we do know that our copy is a gift from our friends Megan Holbrook and Eric Vogel.

View more posts on African American artists.

View more Fine Press Friday posts.

#Fine Press Friday#Fine Press Fridays#Black History Month#Margaret Walker#black poets#black writers#women poets#women writers#African American poets#African American writers#For My People#Elizabeth Catlett#black artists#African American artists#lithographs#color lithographs#lithography#letterpress printing#Limited Editions Club#poetry#Albertus type#Michael and Winifred Bixler#Arches Cover#J.K. Fine Art Editions#Jovonis Bookbindery#Spectrum Bindery#Megan Holbrook#Eric Vogel

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsha Hunt, circa 1969

#marsha hunt#singer#model#writer#actress#black actress#black woman#black women#african american#brown sugar#the rolling stones#mick jagger#black is beautiful#black beauty#afro#1960s#1969#swinging 60s#london#music#rock & roll#vintage#photo#sbrown82

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

When they say black women/people or any people of color can't rock color/pink.

#Black girl#Black female#black female writers#blacklivesmatter#black women#black beauty#black tumblr#just girly thoughts#just girly posts#girly#Girly girl#pink core#Pink girl#innocent girl#Pink barbie#pink barbie#african american#African woman#my post#just girly things#girly aesthetic#pink aesthetic#plus size women#Any size matters

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before I start I’ll say I have a lot of flaws

A couple of fears,

And some deep rooted issues

But there’s this dream that I have

One that I fall asleep to every night

One that’s so deeply woven in my heart

I don’t care if I’m inadequate

I don’t care if I’m not enough

A life with out my art

I lived it, I can’t fathom it

It’s like I’m walking around with two weights on top of my heart

And that’s not exaggerate

I have to reach the life of my dreams

By any means

Even if I have to fight the earth

Cause I’m only here this one time

And I probably lived more than half of it

So even if the earth decides I’m not enough

And raises the standard above the clouds

Above my reach

Then I’ll go the longest route

I’ll build day by day

I’ll scavenge for pieces

Finding new ways

And if along the way I spill it all

Fall on my face

Even If the earth decides to laugh

I’ll start again from scratch

The reality is I’m not gonna stop

So if we got to go back and forth then so be it

It’ll be that way with me until the curtains close

And when I die

And the earth swallows me whole

It will say this one...this one put up a fight

I will leave on it a scar or two

And when it is asked about it

It will tell the story of a girl

With too much heart

Too much grit

Too much love

I promise you

It will tell the stars and echo into the universe

The story of our fight

#poetry#poems#original poetry#poetry book#poets corner#daily poems#black poets on tumblr#daily poetry#spilled ink#black poets society#poems and quotes#poem#literature#quotes#african writers#african poets#women in poetry#women in literature#books and libraries#poetry blog#poetry and prose#prose poetry#poetry books#poets on tumblr#dead poets society#prose poem#original poem

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

...like the omen

I am not here

I am clearly not

I could cry

Fill a mug

And it would empty

To you

But the age would strip cup

Alchemize it to glass

I am not here

I am clearly not

The crawl over my skin

The deep rooted knots

An illusion of the worst kind

Pain so crippling

But you dont believe it

I am not here

I am clearly not

Unless I leave for good

Now you have these thoughts

Lies I suspect

Because I cant reply back

To remind you of your silence

And your lack

The empty responses

"You'll be alright"

But all of the sudden

You knew something wasnt right

Oh now you care

Or you wish you were there

Or I'd come to you

Like I wasnt right there

I am not here

Clearly I am not

In the dark I drown

In the brown I rot

I lacked the desire to mask

You feign fear to ask

I reached out my hand

The side you can see

Funny how seen the unseen

Can be

Until seeing is noticing

Humanity

I am not here

I am clearly not

D. Ondria

03022024

#ecosystem of creatives#african american writers#blackgirlmagic#african american authors#originalbydondria#black writers#creative writing#black creatives#black women writers#original by d ondria

3 notes

·

View notes

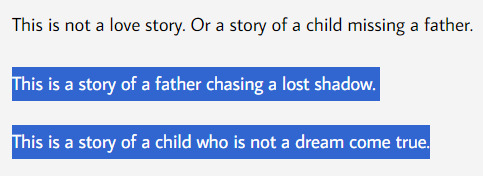

Text

excerpts from My Daddy's Daughter by Noni Selma

#enlarge the image for better quality#typography#typo#lgbt#lgbtqia#african literature#queer literature#non-fiction#transgender#transgirl#transgender women#transfemme#transfem#trans woman#noni selma#nigerian literature#african non-fiction#queer#*edits#*#*mine#african writers#african women#queer women#queer writers#lgbtqia+#trans literature#my edit#mine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toni Cade Bambara

Writer and activist Toni Cade Bambara was born in New York City in 1939. Bambara published her first short story in 1959. She was editor of the revolutionary 1970 anthology, The Black Woman, which included poems, stories, and essays from influential Black women such as Nikki Giovanni, Grace Lee Boggs, and Audre Lorde. Bambara also edited the 1971 anthology Tales and Stories for Black Folks. She wrote two short story collections, Gorilla My Love and Seabirds are Still Alive. Bambara's 1980 novel The Salt Eaters won the American Book Award.

Toni Cade Bambara died in 1995 at the age of 56.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

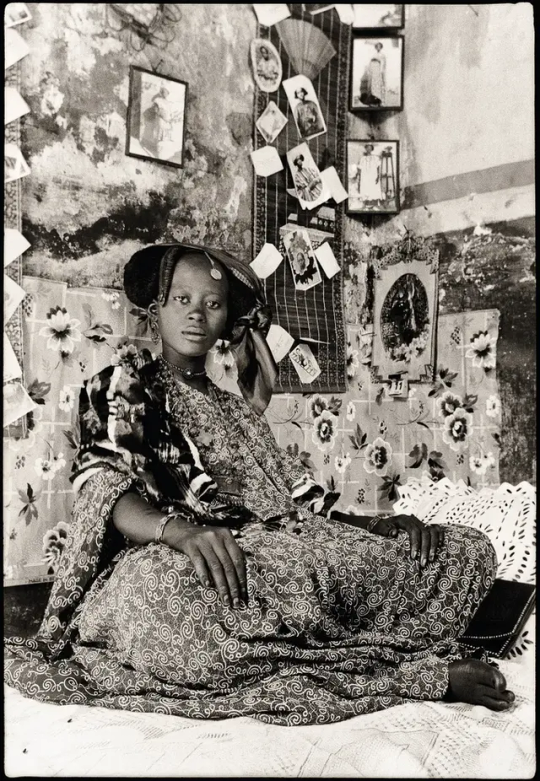

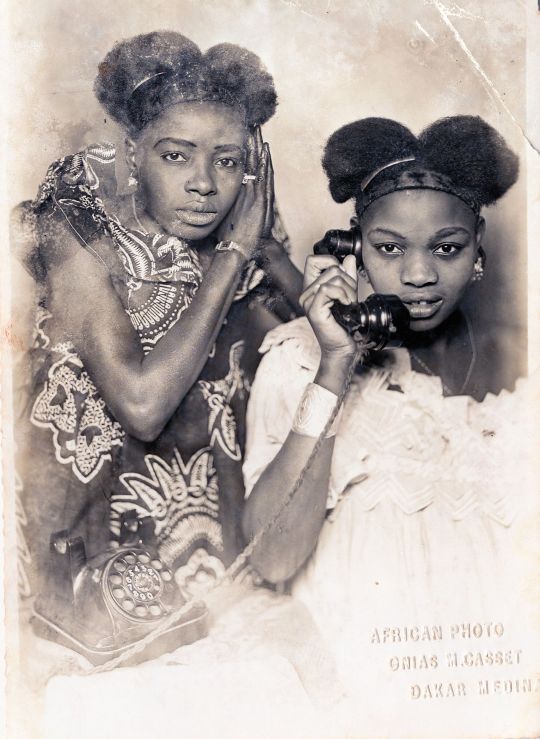

Rediscovering Senegal's Photographic Heritage

By Jemimah Chungu

A captivating narrative of Senegal's rich photographic legacy emerges from the pages of a new book authored by Guilia Paoletti, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia's Department of Art. In a revelatory exploration, Paoletti delves into the vibrant tapestry of Senegalese photography, unearthing a treasure trove of previously unseen images that illuminate the country's historic modernity and cultural richness.

At the heart of Paoletti's narrative lies a visual journey spanning centuries, capturing the essence of Senegal's socio-cultural evolution through the lens of pioneering photographers. From the earliest surviving daguerreotypes dating back to the 1800s to the dawn of modern studio photography, the book offers a window into a bygone era characterized by elegance, sophistication, and artistic expression.

Speaking with CNN, Paoletti challenges conventional narratives surrounding the history of photography, debunking the notion of it being solely a Western invention. Instead, she highlights Senegal's pivotal role in shaping the medium's trajectory, with indigenous photographers asserting agency and creativity in capturing the essence of their society.

Central to Paoletti's narrative are the remarkable stories of Senegalese women, such as the signare – a class of Black or mixed-race women who wielded significant influence and commissioned portraits as a means of self-expression. Through their patronage, these women defied traditional gender norms and asserted their social status, leaving an indelible mark on Senegal's photographic heritage.

However, alongside tales of empowerment and agency, Paoletti also uncovers instances of colonial prejudice and erasure. The encounter between Belgian explorer Adolphe Burdo and the "King of Dakar" serves as a poignant reminder of the clash between modernity and colonial hegemony, with European perceptions often overshadowing African agency.

Despite the challenges of colonialism and cultural hegemony, Senegal's photographic tradition endures as a testament to resilience and creativity. From the decorative collages known as "xoymets" that adorned wedding ceremonies to the proliferation of studio photography in the 20th century, Paoletti paints a vivid portrait of a society deeply intertwined with the art of image-making.

As Senegal's photographic legacy finds renewed recognition and appreciation, Paoletti's book serves as a beacon of cultural revival, offering a fresh perspective on the country's rich heritage. With each image and anecdote, it invites readers to embark on a journey of discovery, celebrating the ingenuity and creativity of Senegal's past and present photographers.

In shedding light on Senegal's photographic heritage, Paoletti's work transcends the confines of academia, offering a poignant reflection on the power of imagery to shape narratives and reclaim lost histories. Through her meticulous research and storytelling prowess, she invites us to reimagine Senegal's past and embrace its photographic legacy as a source of inspiration and cultural pride. (Some excerpts from CNN)

#cnn news#cnn#magazine#africa#my writing#panafrican#senegal#afrofuturism#africa fashion#photography#photographers on tumblr#rural photography#queer writers#african writers#fashion#african politics#writers#afri#women writers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Unofficial Black History Book

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner (1912-2006)

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner is a forgotten black inventor who changed the way menstrual pads operated, but her idea was turned down because of the color of her skin, and she was later not given credit for her invention.

This is her story.

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner was born on May 17th, 1912, in Monroe, North Carolina. She came from a family of inventors. Her father, Sidney Nathaniel Davidson (1890–1958), patented a clothing press that would fit into suitcases but never made money off of the invention, which failed. Her grandfather invented a light signal for trains, and her sister, Mildred Davidson Austin Smith (1916–1993), invented and commercially sold board games.

As a child, Kenner was interested in creating tools to make everyday life more convenient. She had her first idea when she was six years old—a self-oiling door hinge—but the idea never came to fruition. She would draw her ideas throughout her childhood. One of her ideas was a portable ashtray that would attach to the cigarette carton and a sponge tip that would soak the rainwater off an umbrella.

When Mary turned 12, her family moved to Washington, D.C., and she would often visit the United States Patent and Trademark Office to see if anyone had beaten her to patent any of her ideas.

Side Note: The Patent System - that started in 1787, was not open to African Americans who were born into slavery, even if freed, as it did not consider them citizens.

After graduating high school, Mary enrolled at Howard University but later dropped out when she couldn't afford tuition. She took on odd jobs and became a federal employee during WWII. She worked for the Census Bureau and later for the General Accounting Office. Mary also chaperoned younger women who attended dances at military bases in the Washington, D.C., area.

She met soldier and renowned boxer James "Jabbo" Kenner and married him in 1951. They adopted five boys but had no kids of their own. She retired from government work and opened a flower shop while continuing to work on her inventions.

By 1957, Kenner had saved enough money to file her first patent for an elastic belt that held sanitary napkins in place. Adhesive Maxi Pads didn't exist at the time.

How the invention worked was that a moisture-proof napkin pocket was built into the belt, which prevented more leaks than the cloth pads and rags women were using at the time.

One company. 'The Sonn-Nap-Pack' was interested in her invention and offered to market it. But when they discovered she was a black woman, they turned her down instantly.

"One day, I was contacted by a company that expressed an interest in my marketing idea. I was so jubilant...I saw houses, cars, and everything else about to come my way. Sorry to say, when they found out I was black, their interest dropped." She said in Laura F. Jeffery's Book, 'Amazing American Inventors of the 20th Century'

Because of racism, they did not patent the sanitary belt until 30 years after Kenner introduced it. But her invention was a crucial step for women's comfort and revolutionized menstrual hygiene during a time when women had limited options.

Between 1956 and 1987, Kenner received five total patents for her household and personal inventions. A backwasher that one could mount on the shower or bathtub wall was among Kenner's inventions for which she received a patent. When her sister was confined to a bed due to multiple sclerosis in 1976, it inspired her to file her third patent.

A special attachment for a walker or wheelchair that included a hard-surfaced tray and a soft pocket for carrying items. Also, a toilet paper holder that made sure the loose end of the roll was always reachable.

Kenner never became rich from her inventions, but her ideas centered on accessibility and ease and paved the way for more inventions in the future.

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner died at the age of 93 on January 13th, 2006.

__

Previous

Juneteenth

Next

The Tulsa Race Massacre

__

My Resources

https://www.diversityinc.com/womens-history-month-profiles-mary-beatrice-davidson-kenner-inventor/

#the unofficial black history book#mary beatrice davidson kenner#black history matters#black history 365#black stories#herstory#blackblr#little known black history#forgotten black figures#black figures#for the culture#black activism#black women#black inventors#black female writers#black tumblr writers#writing community#know your history#learn your roots#african american inventors#african american history#writers on tumblr#women of black history#women in history

6 notes

·

View notes