#systems philosophy

Quote

A man is so prone to systems and to abstract conclusions that he is prepared to distort the truth on purpose, prepared to deny the visible and the audible just so he can justify his own logic.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground

#philosophy#quotes#Fyodor Dostoyevsky#Notes from Underground#abstract#abstractions#systems#logic#reason#rationality#truth

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

You know, it's actually surprising that, for all the times science fiction has grappled with the question of "at what point does a simulated consciousness become real?" this isn't ever applied to imaginary friends in fiction.

I mean, when you think about it, the "imagination" is just a simulation the brain makes.

So when the brain can make a simulation that is both independent and self-conscious, seeing itself as separate from the creator, and it's obviously capable of passing a Turing test, what makes that simulation any less of a person than the one that pilots the body?

I'd love to see more fiction writers take on topics like this.

#plural#fiction#writblr#philosophy#artificial intelligence#plurality#endogenic#multiplicity#systems#system#plural system#endogenic system#pro endo#pro endogenic#writing#pluralgang#imaginary friend#imaginary friends#writeblr#writing stuff

682 notes

·

View notes

Text

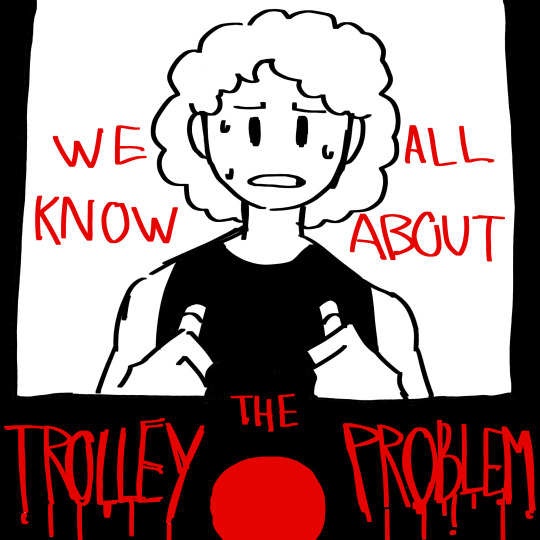

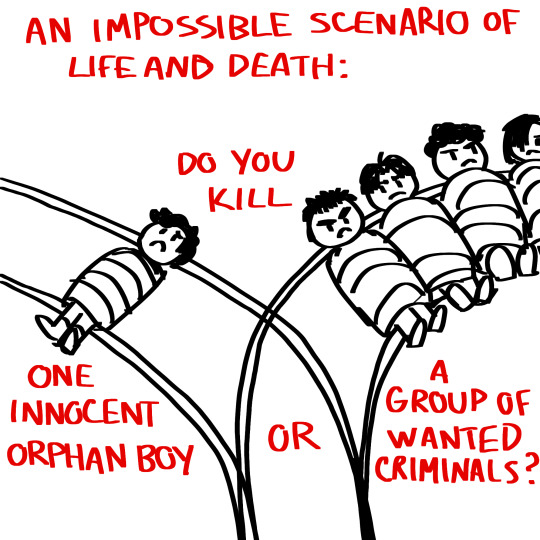

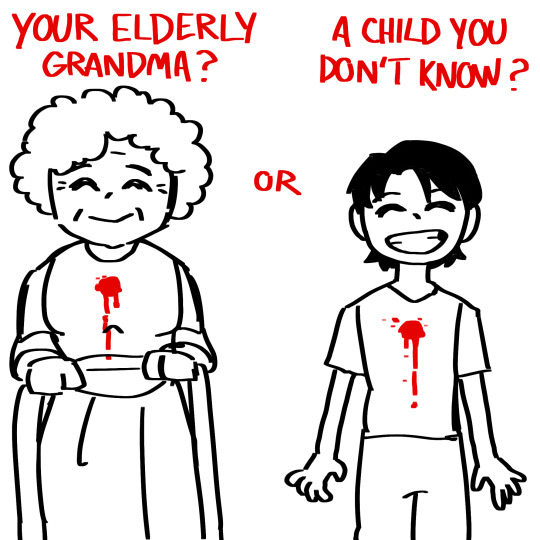

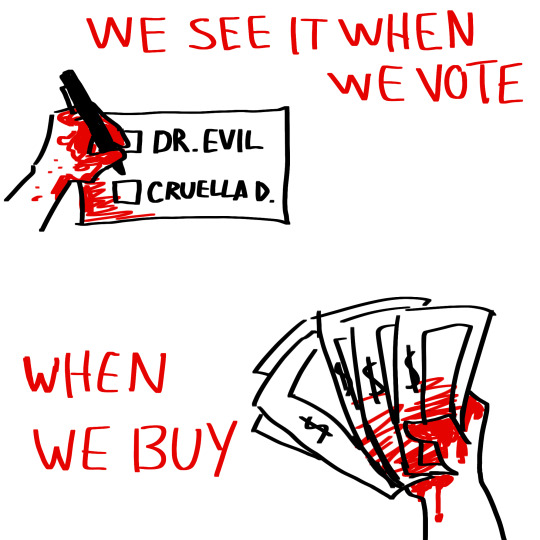

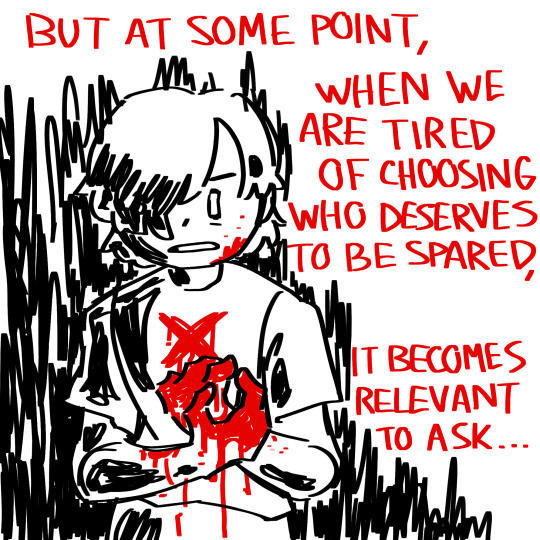

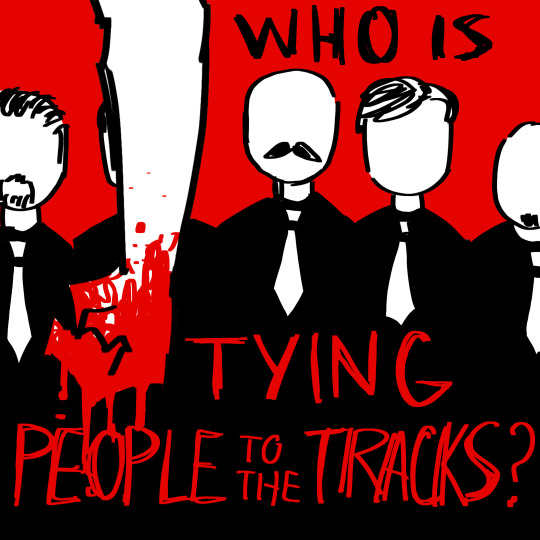

the trolley problem vs. systemic oppression: a comic.

#politics#comics#the trolley problem#philosophy#my art#digital art#alt text#resistance#civil disobedience#capitalism#us politics#us government#american politics#systemic oppression#tw blood#tw implied death#political art

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walks up to a couple: Soo, which one of you is the Prussian-born monarch with emotional baggage and which is the overly dramatic French philosopher they can't help but keep throwing their money at?

#fritz and voltaire#catherine and diderot#if you care to know#obligatory weird that it happened twice reference#history shitposting#voltaire#frederick the great#catherine the great#denis diderot#1700s#the Franco-Prussian patronage/support system/marriage from hell is something that can be so personal#like you don't understand#18th century#history memes#age of enlightenment#prussia#french philosophy#hall of fame

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pursuit of full humanity, however, cannot be carried out in isolation or individualism, but only in fellowship and solidarity; therefore it cannot unfold in the antagonistic relations between oppressors and oppressed. No one can be authentically human while he prevents others from being so. Attempting to be more human, individualistically, leads to having more, egotistically, a form of dehumanization.

— Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Paulo Freire#Pedagogy of the Oppressed#book quotes#quote#quotes#colonization#colonialism#imperialism#neocolonialism#decolonize the university#gradblr#studyblr#philosophy quotes#philosophy#chaotic academia#academia#capitalism#oppression#systems of opression

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What's a Zen?" he said.

The Fool's bells tinkled as he sorted through his cards. Without thinking, he said: "Oh, a sub-sect of the Turnwise Klatch philosophical system of Sumtin, noted for its simple austerity and the offer of personal tranquillity and wholeness achieved through meditation and breathing techniques; an interesting aspect is the asking of apparently nonsensical questions in order to widen the doors of perception."

"How's that again?" said the cook suspiciously. [...]

The Fool hesitated with a card in his hand, suppressed his panic and thought quickly.

"I'faith, nuncle," he squeaked, "thou't more full of questions than a martlebury is of mizzensails."

The cook relaxed.

Terry Pratchett, Wyrd Sisters

#king verence ii#wyrd sisters#discworld#terry pratchett#court jester#in disguise#philosophy#zen#questions#meditation#jokes#expectations#suspicion#the philosophical system of sumtin#apparently nonsensical questions#mizzensails

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I look up at the night sky, and I know that, yes, we are part of this Universe, we are in this Universe, but perhaps more important than both of those facts is that the Universe is in us. When I reflect on that fact, I look up. Many people feel small, because they’re small and the Universe is big. But I feel big, because my atoms came from those stars."

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

#neil degrasse tyson#physics#astrophysics#science#space#universe#stars#humans#philosophy#galaxy#the universe#solar system#planets#scientists#galaxies#life

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 4, in the year 1054, Chinese astonomers recorded what they called a “guest star” in the constellation of Taurus, the Bull. A star never before seen became brighter than any star in the sky. Halfway around the world, in the American Southwest, there was then a high culture, rich in astronomical tradition, that also witnessed this brilliant new star.* From carbon 14 dating of the remains of a charcoal fire, we know that in the middle eleventh century some Anasazi, the antecedents of the Hopi of today, were living under an overhanging ledge in what is today New Mexico. One of them seems to have drawn on the cliff overhang, protected from the weather, a picture of the new star. Its position relative to the crescent moon would have been just as was depicted. There is also a handprint, perhaps the artist’s signature.

This remarkable star, 5,000 light-years distant, is now called the Crab Supernova, because an astronomer centuries later was unaccountably reminded of a crab when looking at the explosion remnant through his telescope. The Crab Nebula is the remains of a massive star that blew itself up. The explosion was seen on Earth with the naked eye for three months. Easily visible in broad daylight, you could read by it at night. On the average, a supernova occurs in a given galaxy about once every century. During the lifetime of a typical galaxy, about ten billion years, a hundred million stars will have exploded—a great many, but still only about one star in a thousand. In the Milky Way, after the event of 1054, there was a supernova observed in 1572, and described by Tycho Brahe, and another, just after, in 1604, described by Johannes Kepler,† Unhappily, no supernova explosions have been observed in our Galaxy since the invention of the telescope, and astronomers have been chafing at the bit for some centuries.

#Cosmos#Carl Sagan#astronomy#science#cosmology#atypicalreads#nonfiction#history#space#philosophy#classics#stars#planets#galaxy#solar system#astrobiology#astrophysics#space science#quotes#1980s#universe#scientific method#1980

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

sorry not sorry, I love jjk but the power system doesn't make any sense. it's a lot of hand waving over vague intellectual concepts the author doesn't actually fully understand which makes it sound really smart, complex, and deep. But really it's ricocheting between an ode to classic shounen power systems and a straight up recreation of them with a new coat of paint.

And that's fine! It's cool to get inspiration from philosophy and mathematics and physics, it's fine to use that inspiration without having a deep theoretical understanding of the concept, and jjk is nothing if not an ode to and a new iteration of the essence of the shounen genre.

But it doesn't mean the author's explanations of that power system--in the text itself or in additional materials--make any more coherent sense than the quantum physics in marvel movies. Trying to make sense of this stuff is a futile effort because it's not fully developed to that scale, and I think that leaves a lot of people either filling in the gaps themselves and misremembering that as text, or deciding the author is actually way smarter than them and they would need a lot more information to understand it, which is not true, because it doesn't actually make sense.

Complex ideas can be explained at very accessible levels in very simplistic ways when they are deeply and fully understood. If someone actually knows more than you, they won't make you feel like you can't understand the things they know. If they do, it's because they don't understand it well enough to explain it.

#i get that it excites people that it seems so deep and I don't want to rain on that parade#but this is a phenomenon that really annoys me in media#and it's not even anything against akutami in particular#i think it's cool that he takes inspiration from things like zeno's paradox for gojo's infinity#and that he references philosophy with junpei and mahito#but i watched the anime and thought “this power system sounds like nonsense” but the anime is really fast paced#so i went to the manga to see if it was better explained or if i just needed it slowed down#and it was still nonsense gobbledygook but with interesting ideas behind it#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#and that's fine but it's not more than it is just because it sounds cool or the author references things that sound smart#if you're confused it's because it's confusing#not because it's above you#jjk critical

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

ID: Screenshot reading "You will recognise it as an arguable point as soon as you switch the victim to a species that you think morally matters. Humans will inevitably die too" followed by a comma before the screenshot cuts off. It is not shown who the author is.

Preface: This will be a long post, but I think it's worthwhile as part of my efforts to open up real conversation about psychopathy and the stigma + misinformation surrounding it. The main reason I'm making a separate post instead of reblogging is that this post is not really intended to be about veganism. I'm more using the contents of the above screenshot to dive more into a topic I've touched on a few times recently.

Humans being "a species that you think morally matters" is an interesting assumption I often see vegan activists make. I've been undecided for a while about talking about this because I know how controversial this is and don't feel a strong desire to deal with the fallout of posting it/saying it outright, but seeing as I've always tried to be as honest and open as possible in here: I do not actually think humans "morally matter." I do not think killing is inherently wrong, either, regardless of species. Just about every creature on Earth engages in killing, either of each other or of members of other species, if not both. I don't think humans are sacred or special in any way, and thus are no exception. I don't see humans killing each other as any more INHERENTLY (this word is incredibly important here... obviously) wrong than, say, leopards killing each other. My culture used to engage in religious human sacrifice, so I have thought about this a whole lot, and it is a bit of a discourse topic in my community to this day (some even think we would be better off today if we had not stopped giving human sacrifices to the gods).

Most arguments for killing being inherently immoral that I've encountered are directly or indirectly rooted in religion, a societal value accepted without question, and/or the result of emotional reactions. One response I often get to this is that if I don't think killing is inherently wrong, I'm not allowed to be sad about it or grieve when people are killed - the idea being that this is somehow hypocritical. This is nonsense. I don't believe abortion is wrong in any way, but I'd never dream of telling someone who had mixed feelings about her abortion that she was a hypocrite for it*. Having complex, mixed, or even negative emotions about something does not make that thing immoral. Not to jump too far into moral philosophy**, but my view is that emotional responses are not - or at least should not be - an indicator of morality in any capacity. I suspect that more people agree with me on this than realize they do, and here is an example of why: Some people feel badly about killing an insect in their home, but most people do not consider this wrong. Even when it comes to humans, many - if not most - people would likely experience negative emotions when they kill out of genuine necessity, such as in self-defense, but very few people will argue that this is morally wrong, that you should just allow yourself to be harmed or killed if someone attacks you.

In this sense, it would be most logically consistent for me to view hunting wild animals in their own territory (as opposed to shit like when rich people transport animals to a personal hunting ground so they're guaranteed not to lose their prey) for food as morally superior to livestock farming, and I very much do. Traditional hunting is the method of killing for food most similar to that of other animals, as far as I understand. That said, I'm not remotely an expert on the topic beyond having hunted before as a kid and having a general understanding of animal behavior at the college level.

However, I will not pretend like I always behave consistently with the moral conclusions I come to. Like I've discussed before, I don't have an emotional response to violating my own morals. I simply didn't come wired with that feature. I don't really feel guilt or shame, so when I do something "bad," whether by my standards or others' standards, I either don't care at all or make a deliberate effort to cognitively "scold" myself, depending on the circumstances. I do consume meat that I have not personally hunted in the wild. While I do not think that livestock farming, especially modern livestock farming, is good in any way (ethically but also environmentally and health wise), because I don't have an emotional reaction to that thought (but do receive dopamine when I eat tasty food), I have so far been unable to convince myself to stop consuming meat.

I have said previously that I am glad that I am the way that I am, and that remains true; I do think my psychopathic traits are overwhelmingly more beneficial than not. This, however, is one example of the ways it actually is a negative to me - I really can't force myself to care about something I don't care about by default, and often have a hard time making conscious decisions that run counter to what produces dopamine. For this same reason, I have repeatedly failed to cut out gluten despite my doctor's insistence that I need to, and despite knowing how much better I feel (no daily migraines!) when I do abstain from it for a while. I tried to go vegan before and found that I latched onto very unhealthy junk food that was vegan by nature, like Oreos, and was eating incredibly badly. It does not help that I don't know how to cook, partly because my genetic disabilities make cooking a difficult endeavor for several reasons.

I am well aware that some people may be upset by this post, and may feel a need to label me a bad person for being this way. This is your prerogative, and I am certainly open to hearing your responses to this post, within reason. If all you want is to "punish" me for this, send me hate anons and insults, feel free, but I'll go ahead and let you know it doesn't do anything to me... not to mention I'm very used to it already as a radfem blogger. If you still want to do so because it makes you feel righteous or something, by all means go ahead, just be aware that it will not elicit a response from me in any way you'd desire, and definitely won't change my thought processes or behaviors. If you want to have an actual conversation, though, I'm more than happy to engage, answer questions, and hear your perspectives.

*I chose this specific example not because anti-choicers think abortion is killing, but because I have seen women be told that their sadness or grief about an abortion (which, btw, does NOT mean she regrets it!) is somehow "pro life" and that she can't talk about how she feels or else the right wing will use it against us. This is also nonsense, and fucked up nonsense at that. The right wing will use whatever they can; I'm in no way disagreeing with that. However, silencing women and girls to serve a narrative is not the answer. The lived experiences of women and girls (or any marginalized persons) cannot ever be devalued or concealed just because the enemy would use them against us. Actually, this is the same response I have given when told I should hide the fact that I didn't regret my mastectomy, or even that I should pretend that I did regret it. My story, my truth, is mine to own and discuss as I choose, whether it could be weaponized by ideological opponents or not. Same is true for all marginalized persons.

** If you are interested in moral philosophy, specifically where morals come from/what people base morals in, this page and the following pages (there's a Next button in the bottom right corner) sum it up pretty well on Page 1, then dive in a good bit more thoroughly with individual pages for each "root cause" of moral systems.

Side note: I will be reblogging this later because it's 6:30am EDT and a lot of my audience is in the USA. I worked hard and spent a lot of time on this, so I'd like it to actually be seen. Not much point trying to educate/inform/raise awareness if nobody sees it lmao

#mine#emotionality#morality#moral philosophy#moral systems#anchor system#personal#vegan discourse#long post#text post#psychopathy

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once More With Feeling (buffy the vampire slayer) pisses me off so much because Wish I Could Stay is a fucking bop and it gets stuck in my head all the time but unfortunately i vehemently disagree philosophically with everything in it

which is sort of the problem with btvs as a whole tbh, a very well made, very compelling show that is nonetheless wrong in so many irritating ways i dont even know where to start bitching about it

#fan wank /#giles voice: oooh youre so depressed clearly the problem is me giving you too much support#ripping away someone's support system and forcing them into high stress situations is obviously good trauma treatment for DYING#and dont even get me STARTED on the magic addiction plotline#or FUCK everything to do with anya and xander#btvs is definitely one of those shows that i fully understand love-hating#like damn great characters great world now give them to me because you did a bad job#its not even that its poorly written! it's not!#but the THEMES. the PHILOSOPHIES. they are BAD.#(not all of them. but a lot of them.)

56 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The condition that gives birth to the rule is different from the condition the rule gives birth to.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Assorted Opinions and Maxims, 392

#philosophy#quotes#Friedrich Nietzsche#Assorted Opinions and Maxims#rules#norms#conditions#systems#morality

96 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In the eyes of many human beings, life appears to be a unique and special phenomenon. There is, of course, some truth to this belief, since no other planet is known to bear a rich and complex biosphere. However, this view betrays an "organic chauvinism" that leads us to underestimate the vitality of the processes of self-organization in other spheres of reality. It can also make us forget that, despite the many differences between them, living creatures and their inorganic counter parts share a crucial dependence on intense flows of energy and materials. In many respects the circulation is what matters, not the particular forms that it causes to emerge.

Manuel DeLanda, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History

#quote#Manuel DeLanda#A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History#life#DeLanda#philosophy#organism#science#self-organization#biosphere#biology#energy#systems#systems theory

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been having a recent thought about the whole Underworld saga. and it involves Odysseus and that phrase "And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you." by Nitch. But I still haven't elaborated enough to post something concrete about my theory.

#I'm using this post as a note#One day maybe I'll post more about#or maybe I forget#but maybe someone has already thought this and I'm just going crazy#like#I study philosophy#what fun would it be to not be crazy and not think things like that about a musical...#lol... I miss my sanity#epic the musical spoilers#epic the ocean saga#epic the cyclops saga#epic the troy saga#epic the musical#epic the circe saga#epic the underworld saga#jorge rivera herrans#odysseus#the odyssey#my f* god I'm struggling with this tumblr tag system

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter VI. Fourth Period. — Monopoly

1. — Necessity of monopoly.

Thus monopoly is the inevitable end of competition, which engenders it by a continual denial of itself: this generation of monopoly is already its justification. For, since competition is inherent in society as motion is in living beings, monopoly which comes in its train, which is its object and its end, and without which competition would not have been accepted, — monopoly is and will remain legitimate as long as competition, as long as mechanical processes and industrial combinations, as long, in fact, as the division of labor and the constitution of values shall be necessities and laws.

Therefore by the single fact of its logical generation monopoly is justified. Nevertheless this justification would seem of little force and would end only in a more energetic rejection of competition than ever, if monopoly could not in turn posit itself by itself and as a principle.

In the preceding chapters we have seen that division of labor is the specification of the workman considered especially as intelligence; that the creation of machinery and the organization of the workshop express his liberty; and that, by competition, man, or intelligent liberty, enters into action. Now, monopoly is the expression of victorious liberty, the prize of the struggle, the glorification of genius; it is the strongest stimulant of all the steps in progress taken since the beginning of the world: so true is this that, as we said just now, society, which cannot exist with it, would not have been formed without it.

Where, then, does monopoly get this singular virtue, which the etymology of the word and the vulgar aspect of the thing would never lead us to suspect?

Monopoly is at bottom simply the autocracy of man over himself: it is the dictatorial right accorded by nature to every producer of using his faculties as he pleases, of giving free play to his thought in whatever direction it prefers, of speculating, in such specialty as he may please to choose, with all the power of his resources, of disposing sovereignly of the instruments which he has created and of the capital accumulated by his economy for any enterprise the risks of which he may see fit to accept on the express condition of enjoying alone the fruits of his discovery and the profits of his venture.

This right belongs so thoroughly to the essence of liberty that to deny it is to mutilate man in his body, in his soul, and in the exercise of his faculties, and society, which progresses only by the free initiative of individuals, soon lacking explorers, finds itself arrested in its onward march.

It is time to give body to all these ideas by the testimony of facts.

I know a commune where from time immemorial there had been no roads either for the clearing of lands or for communication with the outside world. During three-fourths of the year all importation or exportation of goods was prevented; a barrier of mud and marsh served as a protection at once against any invasion from without and any excursion of the inhabitants of the holy and sacred community. Six horses, in the finest weather, scarcely sufficed to move a load that any jade could easily have taken over a good road. The mayor resolved, in spite of the council, to build a road through the town. For a long time he was derided, cursed, execrated. They had got along well enough without a road up to the time of his administration: why need he spend the money of the commune and waste the time of farmers in road-duty, cartage, and compulsory service? It was to satisfy his pride that Monsieur the Mayor desired, at the expense of the poor farmers, to open such a fine avenue for his city friends who would come to visit him! In spite of everything the road was made and the peasants applauded! What a difference! they said: it used to take eight horses to carry thirty sacks to market, and we were gone three days; now we start in the morning with two horses, and are back at night. But in all these remarks nothing further was heard of the mayor. The event having justified him, they spoke of him no more: most of them, in fact, as I found out, felt a spite against him.

This mayor acted after the manner of Aristides. Suppose that, wearied by the absurd clamor, he had from the beginning proposed to his constituents to build the road at his expense, provided they would pay him toll for fifty years, each, however, remaining free to travel through the fields, as in the past: in what respect would this transaction have been fraudulent?

That is the history of society and monopolists.

Everybody is not in a position to make a present to his fellow-citizens of a road or a machine: generally the inventor, after exhausting his health and substance, expects reward. Deny then, while still scoffing at them, to Arkwright, Watt, and Jacquard the privilege of their discoveries; they will shut themselves up in order to work, and possibly will carry their secret to the grave. Deny to the settler possession of the soil which he clears, and no one will clear it.

But, they say, is that true right, social right, fraternal right? That which is excusable on emerging from primitive communism, an effect of necessity, is only a temporary expedient which must disappear in face of a fuller understanding of the rights and duties of man and society.

I recoil from no hypothesis: let us see, let us investigate. It is already a great point that the opponents confess that, during the first period of civilization, things could not have gone otherwise. It remains to ascertain whether the institutions of this period are really, as has been said, only temporary, or whether they are the result of laws immanent in society and eternal. Now, the thesis which I maintain at this moment is the more difficult because in direct opposition to the general tendency, and because I must directly overturn it myself by its contradiction.

I pray, then, that I may be told how it is possible to make appeal to the principles of sociability, fraternity, and solidarity, when society itself rejects every solidary and fraternal transaction? At the beginning of each industry, at the first gleam of a discovery, the man who invents is isolated; society abandons him and remains in the background. To put it better, this man, relatively to the idea which he has conceived and the realization of which he pursues, becomes in himself alone entire society. He has no longer any associates, no longer any collaborators, no longer any sureties; everybody shuns him: on him alone falls the responsibility; to him alone, then, the advantages of the speculation.

But, it is insisted, this is blindness on the part of society, an abandonment of its most sacred rights and interests, of the welfare of future generations; and the speculator, better informed or more fortunate, cannot fairly profit by the monopoly which universal ignorance gives into his hands.

I maintain that this conduct on the part of society is, as far as the present is concerned, an act of high prudence; and, as for the future, I shall prove that it does not lose thereby. I have already shown in the second chapter, by the solution of the antinomy of value, that the advantage of every useful discovery is incomparably less to the inventor, whatever he may do, than to society; I have carried the demonstration of this point even to mathematical accuracy. Later I shall show further that, in addition to the profit assured it by every discovery, society exercises over the privileges which it concedes, whether temporarily or perpetually, claims of several kinds, which largely palliate the excess of certain private fortunes, and the effect of which is a prompt restoration of equilibrium. But let us not anticipate.

I observe, then, that social life manifests itself in a double fashion, — preservation and development.

Development is effected by the free play of individual energies; the mass is by its nature barren, passive, and hostile to everything new. It is, if I may venture to use the comparison, the womb, sterile by itself, but to which come to deposit themselves the germs created by private activity, which, in hermaphroditic society, really performs the function of the male organ.

But society preserves itself only so far as it avoids solidarity with private speculations and leaves every innovation absolutely to the risk and peril of individuals. It would take but a few pages to contain the list of useful inventions. The enterprises that have been carried to a successful issue may be numbered; no figure would express the multitude of false ideas and imprudent ventures which every day are hatched in human brains. There is not an inventor, not a workman, who, for one sane and correct conception, has not given birth to thousands of chimeras; not an intelligence which, for one spark of reason, does not emit whirlwinds of smoke. If it were possible to divide all the products of the human reason into two parts, putting on one side those that are useful, and on the other those on which strength, thought, capital, and time have been spent in error, we should be startled by the discovery that the excess of the latter over the former is perhaps a billion per cent. What would become of society, if it had to discharge these liabilities and settle all these bankruptcies? What, in turn, would become of the responsibility and dignity of the laborer, if, secured by the social guarantee, he could, without personal risk, abandon himself to all the caprices of a delirious imagination and trifle at every moment with the existence of humanity?

Wherefore I conclude that what has been practised from the beginning will be practised to the end, and that, on this point, as on every other, if our aim is reconciliation, it is absurd to think that anything that exists can be abolished. For, the world of ideas being infinite, like nature, and men, today as ever, being subject to speculation, — that is, to error, — individuals have a constant stimulus to speculate and society a constant reason to be suspicious and cautious, wherefore monopoly never lacks material.

To avoid this dilemma what is proposed? Compensation? In the first place, compensation is impossible: all values being monopolized, where would society get the means to indemnify the monopolists? What would be its mortgage? On the other hand, compensation would be utterly useless: after all the monopolies had been compensated, it would remain to organize industry. Where is the system? Upon what is opinion settled? What problems have been solved? If the organization is to be of the hierarchical type, we reenter the system of monopoly; if of the democratic, we return to the point of departure, for the compensated industries will fall into the public domain, — that is, into competition, — and gradually will become monopolies again; if, finally, of the communistic, we shall simply have passed from one impossibility to another, for, as we shall demonstrate at the proper time, communism, like competition and monopoly, is antinomical, impossible.

In order not to involve the social wealth in an unlimited and consequently disastrous solidarity, will they content themselves with imposing rules upon the spirit of invention and enterprise? Will they establish a censorship to distinguish between men of genius and fools? That is to suppose that society knows in advance precisely that which is to be discovered. To submit the projects of schemers to an advance examination is an a priori prohibition of all movement. For, once more, relatively to the end which he has in view, there is a moment when each manufacturer represents in his own person society itself, sees better and farther than all other men combined, and frequently without being able to explain himself or make himself understood. When Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, Newton’s predecessors, came to the point of saying to Christian society, then represented by the Church: “The Bible is mistaken; the earth revolves, and the sun is stationary,” they were right against society, which, on the strength of its senses and traditions, contradicted them. Could society then have accepted solidarity with the Copernican system? So little could it do it that this system openly denied its faith, and that, pending the accord of reason and revelation, Galileo, one of the responsible inventors, underwent torture in proof of the new idea. We are more tolerant, I presume; but this very toleration proves that, while according greater liberty to genius, we do not mean to be less discreet than our ancestors. Patents rain, but without governmental guarantee. Property titles are placed in the keeping of citizens, but neither the property list nor the charter guarantee their value: it is for labor to make them valuable. And as for the scientific and other missions which the government sometimes takes a notion to entrust to penniless explorers, they are so much extra robbery and corruption.

In fact, society can guarantee to no one the capital necessary for the testing of an idea by experiment; in right, it cannot claim the results of an enterprise to which it has not subscribed: therefore monopoly is indestructible. For the rest, solidarity would be of no service: for, as each can claim for his whims the solidarity of all and would have the same right to obtain the government’s signature in blank, we should soon arrive at the universal reign of caprice, — that is, purely and simply at the statu quo.

Some socialists, very unhappily inspired — I say it with all the force of my conscience — by evangelical abstractions, believe that they have solved the difficulty by these fine maxims: “Inequality of capacities proves the inequality of duties”; “You have received more from nature, give more to your brothers,” and other high-sounding and touching phrases, which never fail of their effect on empty heads, but which nevertheless are as simple as anything that it is possible to imagine. The practical formula deduced from these marvellous adages is that each laborer owes all his time to society, and that society should give back to him in exchange all that is necessary to the satisfaction of his wants in proportion to the resources at its disposal.

May my communistic friends forgive me! I should be less severe upon their ideas if I were not irreversibly convinced, in my reason and in my heart, that communism, republicanism, and all the social, political, and religious utopias which disdain facts and criticism, are the greatest obstacle which progress has now to conquer. Why will they never understand that fraternity can be established only by justice; that justice alone, the condition, means, and law of liberty and fraternity, must be the object of our study; and that its determination and formula must be pursued without relaxation, even to the minutest details? Why do writers familiar with economic language forget that superiority of talents is synonymous with superiority of wants, and that, instead of expecting more from vigorous than from ordinary personalities, society should constantly look out that they do not receive more than they render, when it is already so hard for the mass of mankind to render all that it receives? Turn which way you will, you must always come back to the cash book, to the account of receipts and expenditures, the sole guarantee against large consumers as well as against small producers. The workman continually lives in advance of his production; his tendency is always to get credit contract debts and go into bankruptcy; it is perpetually necessary to remind him of Say’s aphorism: Products are bought only with products.

To suppose that the laborer of great capacity will content himself, in favor of the weak, with half his wages, furnish his services gratuitously, and produce, as the people say, for the king of Prussia — that is, for that abstraction called society, the sovereign, or my brothers, — is to base society on a sentiment, I do not say beyond the reach of man, but one which, erected systematically into a principle, is only a false virtue, a dangerous hypocrisy. Charity is recommended to us as a reparation of the infirmities which afflict our fellows by accident, and, viewing it in this light, I can see that charity may be organized; I can see that, growing out of solidarity itself, it may become simply justice. But charity taken as an instrument of equality and the law of equilibrium would be the dissolution of society. Equality among men is produced by the rigorous and inflexible law of labor, the proportionality of values, the sincerity of exchanges, and the equivalence of functions, — in short, by the mathematical solution of all antagonisms.

That is why charity, the prime virtue of the Christian, the legitimate hope of the socialist, the object of all the efforts of the economist, is a social vice the moment it is made a principle of constitution and a law; that is why certain economists have been able to say that legal charity had caused more evil in society than proprietary usurpation. Man, like the society of which he is a part, has a perpetual account current with himself; all that he consumes he must produce. Such is the general rule, which no one can escape without being, ipso facto struck with dishonor or suspected of fraud. Singular idea, truly, — that of decreeing, under pretext of fraternity, the relative inferiority of the majority of men! After this beautiful declaration nothing will be left but to draw its consequences; and soon, thanks to fraternity, aristocracy will be restored.

Double the normal wages of the workman, and you invite him to idleness, humiliate his dignity, and demoralize his conscience; take away from him the legitimate price of his efforts, and you either excite his anger or exalt his pride. In either case you damage his fraternal feelings. On the contrary, make enjoyment conditional upon labor, the only way provided by nature to associate men and make them good and happy, and you go back under the law of economic distribution, products are bought with products. Communism, as I have often complained, is the very denial of society in its foundation, which is the progressive equivalence of functions and capacities. The communists, toward whom all socialism tends, do not believe in equality by nature and education; they supply it by sovereign decrees which they cannot carry out, whatever they may do. Instead of seeking justice in the harmony of facts, they take it from their feelings, calling justice everything that seems to them to be love of one’s neighbor, and incessantly confounding matters of reason with those of sentiment.

Why then continually interject fraternity, charity, sacrifice, and God into the discussion of economic questions? May it not be that the utopists find it easier to expatiate upon these grand words than to seriously study social manifestations?

Fraternity! Brothers as much as you please, provided I am the big brother and you the little; provided society, our common mother, honors my primogeniture and my services by doubling my portion. You will provide for my wants, you say, in proportion to your resources. I intend, on the contrary, that such provision shall be in proportion to my labor; if not, I cease to labor.

Charity! I deny charity; it is mysticism. In vain do you talk to me of fraternity and love: I remain convinced that you love me but little, and I feel very sure that I do not love you. Your friendship is but a feint, and, if you love me, it is from self-interest. I ask all that my products cost me, and only what they cost me: why do you refuse me?

Sacrifice! I deny sacrifice; it is mysticism. Talk to me of debt and credit, the only criterion in my eyes of the just and the unjust, of good and evil in society. To each according to his works, first; and if, on occasion, I am impelled to aid you, I will do it with a good grace; but I will not be constrained. To constrain me to sacrifice is to assassinate me.

God! I know no God; mysticism again. Begin by striking this word from your remarks, if you wish me to listen to you; for three thousand years of experience have taught me that whoever talks to me of God has designs on my liberty or on my purse. How much do you owe me? How much do I owe you? That is my religion and my God.

Monopoly owes its existence both to nature and to man: it has its source at once in the profoundest depths of our conscience and in the external fact of our individualization. Just as in our body and our mind everything has its specialty and property, so our labor presents itself with a proper and specific character, which constitutes its quality and value. And as labor cannot manifest itself without material or an object for its exercise, the person necessarily attracting the thing, monopoly is established from subject to object as infallibly as duration is constituted from past to future. Bees, ants, and other animals living in society seem endowed individually only with automatism; with them soul and instinct are almost exclusively collective. That is why, among such animals, there can be no room for privilege and monopoly; why, even in their most volitional operations, they neither consult nor deliberate. But, humanity being individualized in its plurality, man becomes inevitably a monopolist, since, if not a monopolist, he is nothing; and the social problem is to find out, not how to abolish, but how to reconcile, all monopolies.

The most remarkable and the most immediate effects of monopoly are:

1. In the political order, the classification of humanity into families, tribes, cities, nations, States: this is the elementary division of humanity into groups and sub-groups of laborers, distinguished by race, language, customs, and climate. It was by monopoly that the human race took possession of the globe, as it will be by association that it will become complete sovereign thereof.

Political and civil law, as conceived by all legislators with-out exception and as formulated by jurists, born of this patriotic and national organization of societies, forms, in the series of social contradictions, a first and vast branch, the study of which by itself alone would demand four times more time than we can give it in discussing the question of industrial economy propounded by the Academy.

2. In the economic order, monopoly contributes to the increase of comfort, in the first place by adding to the general wealth through the perfecting of methods, and then by CAPITALIZING, — that is, by consolidating the conquests of labor obtained by division, machinery, and competition. From this effect of monopoly has resulted the economic fiction by which the capitalist is considered a producer and capital an agent of production; then, as a consequence of this fiction, the theory of net product and gross product.

On this point we have a few considerations to present. First let us quote J. B. Say:

The value produced is the gross product: after the costs of production have been deducted, this value is the net product.

Considering a nation as a whole, it has no net product; for, as products have no value beyond the costs of production, when these costs are cut off, the entire value of the product is cut off. National production, annual production, should always therefore be understood as gross production.

The annual revenue is the gross revenue.

The term net production is applicable only when considering the interests of one producer in opposition to those of other producers. The manager of an enterprise gets his profit from the value produced after deducting the value consumed. But what to him is value consumed, such as the purchase of a productive service, is so much income to the performer of the service. — Treatise on Political Economy: Analytical Table.

These definitions are irreproachable. Unhappily J. B. Say did not see their full bearing, and could not have foreseen that one day his immediate successor at the College of France would attack them. M. Rossi has pretended to refute the proposition of J. B. Say that to a nation net product is the same thing as gross product by this consideration, — that nations, no more than individuals of enterprise, can produce without advances, and that, if J. B. Say’s formula were true, it would follow that the axiom, Ex nihilo nihil fit, is not true

Now, that is precisely what happens. Humanity, in imitation of God, produces everything from nothing, de nihilo hilum just as it is itself a product of nothing, just as its thought comes out of the void; and M. Rossi would not have made such a mistake, if, like the physiocrats, he had not confounded the products of the industrial kingdom with those of the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms. Political economy begins with labor; it is developed by labor; and all that does not come from labor, falling into the domain of pure utility, — that is, into the category of things submitted to man’s action, but not yet rendered exchangeable by labor, — remains radically foreign to political economy. Monopoly itself, wholly established as it is by a pure act of collective will, does not change these relations at all, since, according to history, and according to the written law, and according to economic theory, monopoly exists, or is reputed to exist, only after labor’s appearance.

Say’s doctrine, therefore, is unassailable. Relatively to the man of enterprise, whose specialty always supposes other manufacturers cooperating with him, profit is what remains of the value produced after deducting the values consumed, among which must be included the salary of the man of enterprise, — in other words, his wages. Relatively to society, which contains all possible specialties, net product is identical with gross product.

But there is a point the explanation of which I have vainly sought in Say and in the other economists, — to wit, how the reality and legitimacy of net product is established. For it is plain that, in order to cause the disappearance of net product, it would suffice to increase the wages of the workmen and the price of the values consumed, the selling-price remaining the same. So that, there being nothing seemingly to distinguish net product from a sum withheld in paying wages or, what amounts to the same thing, from an assessment laid upon the consumer in advance, net product has every appearance of an extortion effected by force and without the least show of right.

This difficulty has been solved in advance in our theory of the proportionality of values.

According to this theory, every exploiter of a machine, of an idea, or of capital should be considered as a man who increases with equal outlay the amount of a certain kind of products, and consequently increases the social wealth by economizing time. The principle of the legitimacy of the net product lies, then, in the processes previously in use: if the new device succeeds, there will be a surplus of values, and consequently a profit, -that is, net product; if the enterprise rests on a false basis, there will be a deficit in the gross product, and in the long run failure and bankruptcy. Even in the case — and it is the most frequent — where there is no innovation on the part of the man of enterprise, the rule of net product remains applicable, for the success of an industry depends upon the way in which it is carried on. Now, it being in accordance with the nature of monopoly that the risk and peril of every enterprise should be taken by the initiator, it follows that the net product belongs to him by the most sacred title recognized among men, — labor and intelligence.

It is useless to recall the fact that the net product is often exaggerated, either by fraudulently secured reductions of wages or in some other way. These are abuses which proceed, not from the principle, but from human cupidity, and which remain outside the domain of the theory. For the rest, I have shown, in discussing the constitution of value (Chapter II, section 2): 1, how the net product can never exceed the difference resulting from inequality of the means of production; 2, how the profit which society reaps from each new invention is incomparably greater than that of its originator. As these points have been exhausted once for all, I will not go over them again; I will simply remark that, by industrial progress, the net product of the ingenious tends steadily to decrease, while, on the other hand, their comfort increases, as the concentric layers which make up the trunk of a tree become thinner as the tree grows and as they are farther removed from the centre.

By the side of net product, the natural reward of the laborer, I have pointed out as one of the happiest effects of monopoly the capitalization of values, from which is born another sort of profit, — namely, interest, or the hire of capital. As for rent, although it is often confounded with interest, and although, in ordinary language, it is included with profit and interest under the common expression REVENUE, it is a different thing from interest; it is a consequence, not of monopoly, but of property; it depends on a special theory., of which we will speak in its place.

What, then, is this reality, known to all peoples, and never-theless still so badly defined, which is called interest or the price of a loan, and which gives rise to the fiction of the productivity of capital?

Everybody knows that a contractor, when he calculates his costs of production, generally divides them into three classes: 1, the values consumed and services paid for; 2, his personal salary; 3, recovery of his capital with interest. From this last class of costs is born the distinction between contractor and capitalist, although these two titles always express but one faculty, monopoly.

Thus an industrial enterprise which yields only interest on capital and nothing for net product, is an insignificant enterprise, which results only in a transformation of values without adding anything to wealth, — an enterprise, in short, which has no further reason for existence and is immediately abandoned. Why is it, then, that this interest on capital is not regarded as a sufficient supplement of net product? Why is it not itself the net product?

Here again the philosophy of the economists is wanting. To defend usury they have pretended that capital was productive, and they have changed a metaphor into a reality. The anti-proprietary socialists have had no difficulty in overturning their sophistry; and through this controversy the theory of capital has fallen into such disfavor that today, in the minds of the people, capitalist and idler are synonymous terms. Certainly it is not my intention to retract what I myself have maintained after so many others, or to rehabilitate a class of citizens which so strangely misconceives its duties: but the interests of science and of the proletariat itself oblige me to complete my first assertions and maintain true principles.

1. All production is effected with a view to consumption, — that is, to enjoyment. In society the correlative terms production and consumption, like net product and gross product, designate identically the same thing. If, then, after the laborer has realized a net product, instead of using it to increase his comfort, he should confine himself to his wages and steadily apply his surplus to new production, as so many people do who earn only to buy, production would increase indefinitely, while comfort and, reasoning from the standpoint of society, population would remain unchanged. Now, interest on capital which has been invested in an industrial enterprise and which has been gradually formed by the accumulation of net product, is a sort of compromise between the necessity of increasing production, on the one hand, and, on the other, that of increasing comfort; it is a method of reproducing and consuming the net product at the same time. That is why certain industrial societies pay their stockholders a dividend even before the enterprise has yielded anything. Life is short, success comes slowly; on the one hand labor commands, on the other man wishes to enjoy. To meet all these exigencies the net product shall be devoted to production, but meantime (inter-ea, inter-esse) — that is, while waiting for the new product — the capitalist shall enjoy.

Thus, as the amount of net product marks the progress of wealth, interest on capital, without which net product would be useless and would not even exist, marks the progress of comfort. Whatever the form of government which may be established among men; whether they live in monopoly or in communism; whether each laborer keeps his account by credit and debit, or has his labor and pleasure parcelled out to him by the community, — the law which we have just disengaged will always be fulfilled. Our interest accounts do nothing else than bear witness to it.

2. Values created by net product are classed as savings and capitalized in the most highly exchangeable form, the form which is freest and least susceptible of depreciation, — in a word, the form of specie, the only constituted value. Now, if capital leaves this state of freedom and engages itself, — that is, takes the form of machines, buildings, etc., — it will still be susceptible of exchange, but much more exposed than before to the oscillations of supply and demand. Once engaged, it cannot be disenaged without difficulty; and the sole resource of its owner will be exploitation. Exploitation alone is capable of maintaining engaged capital at its nominal value; it may increase it, it may diminish it. Capital thus transformed is as if it had been risked in a maritime enterprise: the interest is the insurance premium paid on the capital. And this premium will be greater or less according to the scarcity or abundance of capital.

Later a distinction will also be established between the insurance premium and interest on capital, and new facts will result from this subdivision: thus the history of humanity is simply a perpetual distinction of the mind’s concepts.

3. Not only does interest on capital cause the laborer to enjoy the fruit of his toil and insure his savings, but — and this is the most marvellous effect of interest — while rewarding the producer, it obliges him to labor incessantly and never stop.

If a contractor is his own capitalist, it may happen that he will content himself with a profit equal to the interest on his investment: but in that case it is certain that his industry is no longer making progress and consequently is suffering. This we see when the capitalist is distinct from the contractor: for then, after the interest is paid, the manufacturer’s profit is absolutely nothing; his industry becomes a perpetual peril to him, from which it is important that he should free himself as soon as possible. For as society’s comfort must develop in an indefinite progression, so the law of the producer is that he should continually realize a surplus: otherwise his existence is precarious, monotonous, fatiguing. The interest due to the capitalist by the producer therefore is like the lash of the planter cracking over the head of the sleeping slave; it is the voice of progress crying: “On, on! Toil, toil!” Man’s destiny pushes him to happiness: that is why it denies him rest.

4. Finally, interest on money is the condition of capital’s circulation and the chief agent of industrial solidarity. This aspect has been seized by all the economists, and we shall give it special treatment when we come to deal with credit.

I have proved, and better, I imagine, than it has ever been proved before:

That monopoly is necessary, since it is the antagonism of competition;

That it is essential to society, since without it society would never have emerged from the primeval forests and without it would rapidly go backwards;

Finally, that it is the crown of the producer, when, whether by net product or by interest on the capital which he devotes to production, it brings to the monopolist that increase of comfort which his foresight and his efforts deserve.

Shall we, then, with the economists, glorify monopoly, and consecrate it to the benefit of well-secured conservatives? I am willing, provided they in turn will admit my claims in what is to follow, as I have admitted theirs in what has preceded.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

One must imagine Sisyphus in late stage capitalism.

#struggling to find joy in pointless toil that you’ll never directly reap the rewards of seems like some late stage capitalism bullshit#Albert Camus I respect the hustle but sometimes the joy isn’t in the climb but in the fall and refusal to push again#(this is a joke - I know Camus is more building off of nihilistic discussion on the search for meaning & religion. not economic struggle)#(but the repeated application of this philosophy as a way to cope with the horror of an exploitative system is…disturbing..)#*exploitative economic system#philosophy#gods damned greeks#lunch hour thoughts

19 notes

·

View notes