#Plotting

Text

That brilliant plot idea I had at 3 AM when I try to remember it.

#writblr#writers on tumblr#writing community#writers of tumblr#plot writing#plotting#writer#writers#writing#writing meme#writing humor#creative writing#creative writers#queue

979 notes

·

View notes

Text

old livejournal icon i found

#kittyposting#web finds#bunny#bunnies#sweet lolita#icons#webcore#livejournal#old web#aesthetic#old internet#usakumya#lolita fashion#lolita#baby the stars shine bright#egl community#graphics#i know nothing about lolita and am stealing these tags from rbs lol#btssb#old school lolita#classic lolita#bunny girl#plotting#internetcore#rabbit#rabbits#kumya#egl#greatest hits#500+ notes

576 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 5 Most Essential Turning Points in a Character’s Arc

You spend so much time creating a character because you want them to feel real. You want to connect with them and use them to create an experience for your readers. Their character arc is how that happens.

Don’t miss out on these essential turning points that make an arc feel not only whole, but complete.

1. The Inciting Incident

Your inciting incident gets your plot moving. It isn’t going to be the first sentence of your story (also called your hook), although it could be if you crafted your first sentence for that purpose.

An inciting incident is a plot event that guides your character in a new direction. It’s the successful prison break, the meeting of instant rivals, or the moment your protagonist wins the lottery in your first chapter.

Without the inciting incident, your protagonist’s life would carry on as usual. They wouldn’t start the arc that makes them an interesting person for the reader to stick with throughout your story.

2. Introducing the Protagonist’s Main Flaw

Every protagonist needs a primary flaw. Ideally, they’ll have more than one. People aren’t perfect and they rarely get close enough to only have one negative characteristic. Protagonists need that same level of humanity for readers to connect with them.

There are many potential flaws you could consider, but the primarily flaw must be the foundation for your character’s arc. It might even be the catalyst for the story’s peak.

Imagine a hero archetype. They’re great and well-intended, but they have a problem with boasting. Their arc features scenes where they learn to overcome their need to brag about themselves, but they get drunk and boast in a bar right before the story’s peak. The antagonist’s best friend hears this because they’re at the same bar, so they report the hero’s comment to the main villain. It thwarts the hero’s efforts and makes the climax more dramatic.

Other potential flaws to consider:

Arrogance

Pride

Fear

Anxiety

Carelessness

Dishonesty

Immaturity

3. Their First Failure

Everyone will fail at a goal eventually. Your protagonist should too. Their first failure could be big or small, but it helps define them. They either choose to continue pursuing that goal, they change their goal, or their worldview shatters.

Readers like watching a protagonist reshape their identity when they lose sight of what they wnat. They also like watching characters double down and pursue something harder. Failure is a necessary catalyst for making this happen during a character’s arc.

4. Their Rock Bottom

Most stories have a protagonist that hits their rock bottom. It could be when their antagonist defeats them or lose what matters most. There are numerous ways to write a rock-bottom moment. Yours will depend on what your character wants and what your story’s theme is.

If you forget to include a rock-bottom moment, the reader might feel like the protagonist never faced any real stakes. They had nothing to lose so their arc feels less realistic.

Rock bottoms don’t always mean earth-shattering consequences either. It might be the moment when your protagonist feels hopeless while taking an exam or recognizes that they just don’t know what to do. Either way, they’ll come to grips with losing something (hope, direction, or otherwise) and the reader will connect with that.

5. What the Protagonist Accepts

Protagonists have to accept the end of their arc. They return home from their hero’s journey to live in a life they accept as better than before. They find peace with their new fate due to their new community they found or skills they aquired.

Your protagonist may also accept a call to action. They return home from their journey only to find out that their antagonist inspired a new villain and the protagonist has to find the strength to overcome a new adversary. This typically leads into a second installment or sequel.

Accepting the end of their arc helps close the story for the reader. A protagonist who decides their arc wasn’t worth it makes the reader disgruntled with the story overall. There has to be a resolution, which means accepting whatever the protagonist’s life ended up as—or the next goal/challenge they’ll chase.

-----

Hopefully these points make character arcs feel more manageable for you. Defining each point might feel like naming your instincts, but it makes character creation and plotting easier.

Want more creative writing tips and tricks? I have plenty of other fun stuff on my website, including posts like Traits Every Protagonist Needs and Tips for Writing Subplots.

#character arcs#creating characters#creating character arcs#character development#writing characters#character concept#plotting#how to plot#writing plot#creative writing#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writing tips#writing advice#writing resources#writing inspiration#writing community#writing help#writing

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Worldbuilding is crazy, like welp guess I'll write an entire wiki page on a rare disease I just made up

#writing#creative writing#fiction writing#worldbuilding#fiction#writeblr#writer problems#write#writer#realistic writing#plotting#story planning#writer's block#writer jokes#writer things#writers#writerscorner

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

scheming

this is the end for now, i will continue if motivation comes,, check tags

#comic#team minato#my art#obito#rin#kakashi#best team#rin is the best wing woman#sketch#doodle#scheming#plotting#obt#rn#kks#big fan of gremlin rin#troublemakers#alcohol#comedy#humor#please#reblog and tell me what u think rin's grand plan#if you want a part two i will need gremlin energy#maximum effort#black and white#monochrome#naruto fanart#fan comic#uchiha obito#nohara rin

542 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Such Thing As Filler

Okay, so yes, this is another post based on something I saw that irritated me, but it seems like this idea keeps coming up, so I need y'all to internalize this. There is no such thing as filler in good writing. None. Do not approach your work thinking you have to fill space in a story, I will beat you with this wiffle bat. Don't ask me where I got the wiffle bat. Don't even worry about it.

The idea of filler comes from a very particular place - when an anime or TV show has to fit in a certain number of episodes, but doesn't have enough content (hasn't caught up with the manga, the source material isn't long enough, etc) to cover those episodes. An episode has to be written, but the characters can't really progress, and so are given something else to do. Many a trope has come from these episodes, and they're sometimes necessary. Filler in this context is something that makes sense.

The dark side of filler is the idea that you need some space between Big Event 1 and Big Event 2 in your story, therefore you need throw anything in there to take up space and make your word count. This is a mistake I've made and I've seen plenty of other writers do it too, but it's a huge waste of your time. You do need something between those big action scenes, but you should always be writing to accomplish something.

Instead of thinking of that writing as filler, try to approach it with three things in mind:

Move Forward With Character Development and Backstory - Your characters barely survived a huge gunfight, and they won't encounter the big bad again for another few chapters. How do your characters decompress from that gunfight, and what does that say about them? Did a cocky character go in guns blazing, only to be deeply shaken by how a real fight works? Did that fight spark a moment of deep trauma for the main character that they have to reflect on afterwards?

Filling this space with meaningless scenes is a huge waste of opportunity. Think about how to dive deeper into your characters.

Move Forward With Plot and Subplot Development - The bad guy beat the heroes to the stolen gem, but they left behind a clue to why they want it. However that clue could reveal some painful truths about the protagonist's beloved great aunt... Carmen Sandiego???

A major goal following a big action scene is having the characters figure out what to do with what they've learned and what to do next. It's where romance subplots or secret relative subplots make progress, when truths are revealed and next steps are taken. You can absolutely do this in any setting - a flirty conversation while at the battling cages, a tense moment of feelings while hunting down a wayward chicken - but your main goal is making progress for both the characters and plot.

Move Forward With Worldbuilding - Worldbuilding has it challenges, believe me. You don't want to write a chapter on how an airship works only to have to cut it later. But you should still try to flesh out your world, and you should do so with the perspective of how to use that worldbuilding to your benefit. Maybe a critical scene hinges on the main characters knowing how that airship works, or that lake your main character often stares at is the setting of the big Act 3 Boat Battle. The weather can play into both perspective and emotions. Knowing what the main character's house and car looks like can reflect a lot on their personal character or backstory.

When you're struggling with a scene or a chapter, rather than writing filler, take a few steps back and think. What can you establish with your worldbuilding? What can you reveal about your characters through their dialogue and actions? What subplot could you explore or add in these between moments?

Filler from a fandom perspective - Now let me make this clear - if you're writing a fanfic just to have a cute moment between the characters you like, or you really want to force everyone to do that weird Twilight baseball scene, that's fine. You don't need a grand goal to achieve for every story, there's no need to justify your fanwork in any way other than you wanted to do it.

But I'd also argue fanwork doesn't fall under the filler label either - something you create, be it a character snapshot or a 'what if the gang meets Slenderman' parody, isn't taking up meaningless space. It's something fun you did that you and others enjoy, and there's nothing wasteful or pointless about that.

#writing advice#plotting#filler#writblr#the wiffle bat is a metaphor#for uuuuh something that sounds cool and interesting#let's go with that

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 Alternatives to Popular Writing Advice

Some writing advice get passed off as something every writer has to do. The truth is, these tips might not work for everybody! NaNo participant Nicole Wilbur offers some alternatives to popular writing advice that may be a better fit for your writing needs.

While there are no definitive writing “rules”, there’s certainly writing advice so common it feels like it’s become canon. Most popular writing advice is generally good – but what if it doesn’t light up your brain? What if a particular tip doesn’t resonate with you?

If this popular advice isn’t working - try these alternatives!

Common advice: Make your character want something.

Alternative: Ask what your character is most afraid of.

Your character usually wants something – the MC’s goal driving the story is a common plot, after all. That something needs to be concrete, meaning the audience will know definitively when they’ve achieved their goal.

(Is “found independence” concrete? No. Signed the lease on their first apartment? Yes.)

But if you aren’t sure yet, or what they want doesn’t feel motivating enough to support your inciting incident, start with a different question: what is your character afraid of?

Katniss wants to survive, with her family, yes. But she’s terrified of helplessly watching them die.

Common advice: Identify your story’s theme and stick it on a post- it above your computer.

Alternative: Use the character’s arc to create a main idea statement, and craft several related questions your story explores.

English class really made ‘theme’ feel heavy-handed. In my grade nine English class, we listed the themes of To Kill a Mockingbird as: coming of age, racism, justice, and good vs. evil.

While these are the topics explored in the book, I’ve never found this advice helpful in writing. Instead, I like to use the controlling idea concept (as in Robert McKee’s Story) and exploratory questions (as in John Truby’s Anatomy of Genres).

A controlling idea is a statement about what the author views as the “proper” way to live, and it’s often cause-and-effect. The exploratory question is – well, a question you want to explore.

In It’s a Wonderful Life, the controlling idea is something to the effect of “Life is meaningful because of our relationships” or “our lives feel meaningful when we value our family and community over money.” The question: How can a single person influence the future of an entire community?

Common advice: List out your character’s traits, perhaps with a character profile.

Alternative: Focus on 2-3 broad brushstrokes that define the character.

When I first started writing, I would list out everything I wanted my character to be: smart, daring, sneaky, kind, greedy, etc. I created a long list of traits. Then I started writing the book. When I went back to look at the traits, I realized the character wasn’t really exhibiting any of these.

Instead of a long list of traits to describe your character, try identifying three. Think of these like three brush strokes on a page, giving the scaffolding of your character. Ideally, the combination of traits should be unexpected: maybe the character is rule-following, people-pleasing, and ambitious. Maybe the character is brash, strategic, and dutiful.

Then – and this is the fun part – consider how the traits come into conflict, and what their limits are. What happens when our ambitious rule-follower must break the law to get what she wants? Sure, a character might be kind, but what will make her bite someone’s head off?

Common advice: Create a killer plot twist.

Alternative: Create an information plot.

Readers love an unexpected plot twist: whether a main character is killed or an ally turns out to be the bad guy, they’re thrilling. But plotting towards one singular twist can be difficult.

Instead of using the term plot twist, I like thinking in terms of Brandon Sanderson’s “information” plot archetype.

An information plot is basically a question the reader is actively trying to work out. It could be like Sarah Dessen's Just Listen where we wonder "what happened between Annabel and her ex-best friend?", "why is Annabel's sister acting strangely?" and "who is Owen, really?" Those all have to do with backstory, but information plots can be about pretty much any hidden information. Another popular question is "who is the bad guy?" - or in other words, "who is after the characters?" The Charlie's Angel franchise, for example, tends to keep viewers guessing at who the true antagonist is until the last few scenes.

Nicole Wilbur is an aspiring YA author, writing sapphic action-adventure stories that cure wanderlust. As a digital nomad, she has no house and no car, but has racked up a ridiculous number of frequent flier miles. She chronicles her writing and travelling journey on her YouTube channel and Chasing Chapters substack.

Photo by George Milton

415 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you explain the fichtean curve to me?

The Fichtean Curve is a simple yet effective approach to storytelling that can add tension, drive conflict, and keep your readers hooked!

We've put together this blog post in the Reading Room to help you make sense of what it is and learn how to use it.

#fichtean curve#plotting#plotting tips#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writeblr#writerblr#writing tips#writing advice#writblr#writers corner#plotter#advice for authors#helping writers#writing blog#help for writers#writing asks#let's write#writing resources#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#resources for writers#references for writers#writer#writers block

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some more thoughts about Branch and Brozone

I love all the recovery fics on AO3, can't get enough of them, but a lot of them seem to have something in common: Branch is the most messed up of his brothers.

Which fair enough, we know Branch's story, lots of terrible things happened to him, but he's in recovery, he has a supportive girlfriend, is a pillar of the community, a surprising number of friends, so Branch basically has his life together

Branch is happy with his life, he's settled. Sure he has some grief and regrets he's not quite ready to talk about, but that's normal.

Bruce seems to be basically in the same place, he has some grief and regrets, but he has a loving and supportive family, is a member of his community, and has a few friends.

Except has Bruce actually dealt with anything? Or just pushed it aside because he has to be strong and responsible for his kids?

Then we have Clay, while he is a valued member of the community, he's trapped, there's no option to leave, no freedom, surrounded by a group of traumatised trolls who are terrified of the outside word to the point they're censoring themselves?

Clay's willingness to just throw Poppy to Viva as a distraction so he and his brothers can escape?

Yeah, no way Clay isn't hiding piles of trauma and his insistence of still playing a role, even if that role is completely different from his previous role

We have John Dory, who's living in the past, refusing to see that his brothers have changed. Who returned to the tree and found everyone gone, and was convinced everyone was dead for years? Who put so much pressure on himself and his brothers, he broke?

And Floyd is going to be extremely traumatised by his near death experience, months of captivity. Althrough lots of stories are already covering his recovery, what happened before then?

But the brothers are safe now.

And the funny thing about Trauma? It's easier to break down when you are finally safe, bringing up all the terrible memories again.

I really want to see a fic where Branch is actually the least messed up of his brothers, because he's dealt with his trauma and knows what is likely to trigger him, has strategies in place when things get harder.

Now the adventure is over, do the brothers attempt to be a family again? Can they meet in the middle without setting each other off? Can they learn to be kind to each other? Can they be kind to themselves?

Or is everything swept under the carpet until it explodes?

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

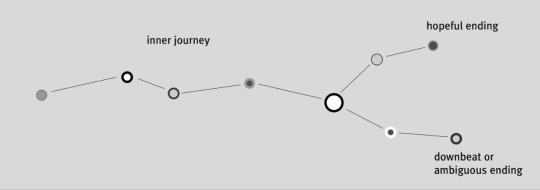

How are literary and Commercial Stories Different?

Literary plots are meant to explore a specific theme/convey a message to the reader.

Literary plots can be slow paced.

Literary plots can have different types of endings.

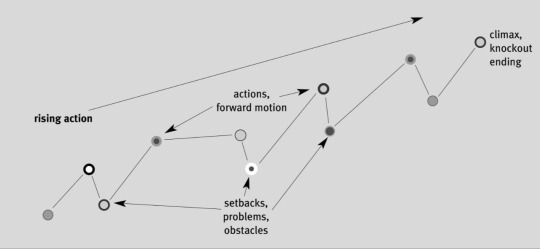

Commercial plots are meant to entertain.

Commerical plots are fast-paced.

Commercial plots must almost always have a happy ending.

For Literary Plots:

detailed characterization: authors explore the inner change and development of the character (which means the external action is going to be slower paced)

use of metaphors, symbols, and presentation of ideas in a way that requires analysis

aims to deliver a message or moral

On the other hand, Commercial Plots:

fast-paced and action oriented, delivers highly emotional scenes so entice the reader rather than ambiguous writing

uses intuitive language, setting and tropes to help readers immerse in the story world quickly

often, the stakes are a lot higher

the ending needs to provide a sense of satisfaction for the readers. Otherwise, they might not feel compensated for all the time they invested in reading.

If you like my blog, buy me a coffee! ☕

Reference: <Write Great Fiction: Plot and Structure (techniques and exercises for craftin a plot that grips readers from start to finish)> by James Scott Bell

#writer#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writeblr#writing tips#writers corner#writers community#poets and writers#writing advice#writing resources#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#helping writers#writing help#writing tips and tricks#how to write#writing life#let's write#resources for writers#references for writers#plot#plotting#story writing#novel writing#authors

141 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiii, I just dicovered your acc and i'm loving it 🥰 I have this lil problem where I have in mind and write scenes but without a plot. And I'm very fond to the characters so I can't put them into a plot because I don't want them to suffer or a think if they do suffer it'll we forced and too much. Any tips for that?

How to Plot A Novel If You Only Have Characters & Scenes

So, you have a great cast of characters and some exciting scenes in mind, but you're struggling to put them together into a cohesive plot. Don't worry, you're not alone. Many writers struggle with plotting their novels, especially when they have a strong focus on characters and scenes. I have also been facing difficulties with this recently. But fear not, in this article, I’ll help you explore how you can plot a novel even if you only have characters and scenes to work with.

Why Is Plotting Important?

Before we dive into the how, let's first understand why plotting is important. A well-crafted plot is the backbone of any successful novel. It keeps readers engaged, creates tension and conflict, and ultimately leads to a satisfying resolution. Without a strong plot, your novel may fall flat and fail to capture the attention of readers.

Types of Plots

There are many different types of plots, but they can generally be categorized into three main types: character-driven, plot-driven, and hybrid.

Character-driven plots focus on the internal struggles and growth of the main character. The plot is driven by the character's desires, flaws, and decisions.

Plot-driven plots focus on external events and conflicts that drive the story forward. The characters may still have their own arcs, but the main focus is on the events and how they affect the characters.

Hybrid plots combine elements of both character-driven and plot-driven plots. They have a balance of internal and external conflicts that drive the story forward.

Understanding the type of plot you want to create can help guide your plotting process.

How to Plot A Novel with Only Characters & Scenes

Now that we understand the importance of plotting and the different types of plots, let's explore how you can plot a novel with only characters and scenes.

Start with Your Characters

Since you already have a strong cast of characters, it makes sense to start with them. Take some time to fully develop your characters, including their personalities, motivations, and flaws. This will help you understand how they will react in different situations and what conflicts they may face.

Identify Your Main Conflict

Every novel needs a main conflict that drives the story forward. This could be a physical conflict, such as a battle or a chase, or an emotional conflict, such as a character's internal struggle. Identify what the main conflict in your novel will be and how it will affect your characters.

Create a Story Structure

A story structure is a framework that helps guide the flow of your novel. It typically includes the beginning, middle, and end, and can be broken down further into acts or chapters. Creating a story structure can help you see the bigger picture of your novel and how your characters and scenes fit into it.

Map Out Your Scenes (High Priority) 🚩

Now it's time to map out your scenes. Start by listing all the scenes you have in mind, even if they are not in chronological order. Then, arrange them in a logical order that makes sense for your story. This may require some rearranging and tweaking to ensure a smooth flow of events.

Connect Your Scenes with Conflict (High Priority) 🚩

Once you have your scenes in order, it's time to connect them with conflict. Every scene should have some form of conflict, whether it's internal or external. This will keep readers engaged and drive the story forward. Look at each scene and identify the conflict present, and how it connects to the main conflict of the novel.

Create a Character Arc for Each Character

As your characters go through different conflicts and events, they should also experience growth and change. This is where character arcs come in. A character arc is the journey a character goes through, from their initial state to their final state. Create a character arc for each of your main characters, and make sure their actions and decisions align with their arc.

Add Subplots

Subplots are smaller storylines that run parallel to the main plot. They add depth and complexity to your novel and can help develop your characters further. Look at your characters and see if there are any side stories or relationships that could be explored in a subplot. Just make sure they tie back to the main plot in some way.

Use Plotting Tools

If you're struggling to put all the pieces together, consider using some plotting tools to help you. There are many resources available, such as plot diagrams, beat sheets, and storyboards, that can help you visualize your plot and ensure all the elements are in place. If you need help with scene structure use my new scene workbook here.

Real-World Examples of Plotting with Characters & Scenes

One example of a novel that successfully uses characters and scenes to drive the plot is "To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee. The main conflict is the trial of Tom Robinson, but it is the characters, particularly Scout and Atticus, and their reactions to the events that drive the story forward.

Another example is "The Hunger Games" by Suzanne Collins. The main conflict is the Hunger Games themselves, but it is Katniss' internal struggle and her relationships with other characters that keep readers engaged and invested in the story.

Final Thoughts

Plotting a novel with only characters and scenes may seem daunting, but with the right approach, it can be done successfully. Start by fully developing your characters, identifying the main conflict, and creating a story structure. Then, map out your scenes, connect them with conflict, and create character arcs. Don't be afraid to use plotting tools to help you along the way. With these tips, you'll be on your way to crafting a compelling plot that will keep readers hooked until the very end.

If you require assistance with developing your scene structure, you can access my Scene Workbook for Writers at no cost.

I am sorry to the individual who sent me this question. I have a lot of questions in my Tumblr inbox and have only recently come across this nice question. I apologize for the 4-month delay.

#thewriteadviceforwriters#writeblr#writing#on writing#writing tips#creative writing#writers block#how to write#writers and poets#writing plot#plot points#plotting#character building#writing characters#aspiring author#writerscommunity#writerscorner#indie author#novel writing#writer#author#writersblock#writers on tumblr#writerslife#writersociety#female writers#writer things#character sheet#original character#character idea

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

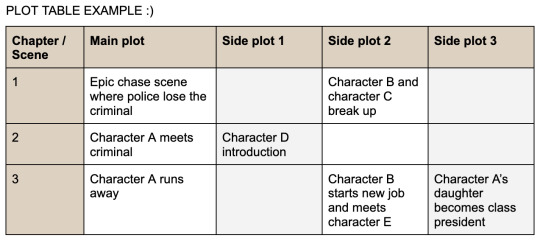

Plot tables: Mapping out and organizing all your plots and storylines

Can't organize your plot and are juggling between several plot lines? I got your back, I present: Plot tables!

(I'm probably not the only person to use these, but I have no idea if these are commonly used and I just don't know about it or I actually did something with this)

Here's a loose example I threw together. It's just a normal table where each column represents a different storyline within the same story. It shows you roughly what should happen in each chapter / scene.

e.g., from the example table, we see that in chapter / scene 1, there's a chase scene where the police lose track of the criminal they're following, as well as in the same chapter we see character B and C break up.

It's nothing groundbreaking, but it's something I want to share considering the amount of people I see complaining about juggling 50 million storylines and having no orderly way to keep track of it

#writers#writers on tumblr#writeblr#writing inspiration#your local sewer rat#navigation#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#creative writing#writing#plotting#writing plot#storylines#storyline#organizing plot#planning plot#planning a story#story planning

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Connecting With Your Reader's Emotions

We’ve all read a book or story that captured our hearts and made us feel things very deeply. It’s a superpower writers have, but it isn’t something we’re born with.

Connecting with your reader’s emotion happens when you’ve practiced writing. It becomes easier after each rough draft, each great draft, and each terrible draft.

But—if you want to save yourself some time, these are a few perspectives you can use to sharpen your writing tools.

1. Display Your Protagonist’s Inner Emotions

Your readers want to experience a character’s journey by connecting with them emotionally. We pick up books to feel things while learning something or just taking a break from life.

Displaying your protagonist’s inner conflict could look something like: She saw the ghost in the hallway, which scared her.

Your reader will feel more engaged if you describe how fear makes your protagonist feel instead of them feeling fear generally: She saw the ghost in the hallway and fear shot through her body like lightning.

You don’t need tons of flowery language to make your reader feel the same things as your character. Sometimes a minor descriptor or simile can do the job.

2. Show Your Protagonist’s Feelings Through External Reactions

Emotions don’t solely exist inside our hearts and minds. We also have external reactions to them. That could be nodding in confusion, shifting uncomfortably in a chair, or bending over laughing.

Consider this example:

“I love your laugh,” Anita said to Alice. “It makes my heart skip a beat.”

Heat spread through Alice’s cheeks as she smiled.

“Oh, you don’t mean that.”

You don’t need to mention how it feels to receive a compliment from a crush or why flattery is nice to hear. The physical reaction of blushing is something the reader can relate to and understand.

3. Make Your Reader Feel Something Your Character Doesn’t

This is a fun one. Sometimes characters have to figure something out, but the reader already knows what’s going on.

This could happen when you’re writing a horror story that is supposed to teach the reader about the joy of recognizing your own strength. The protagonist has the skills in the beginning to defeat the evil antagonist, but must reach rock bottom before cheering himself on. The whole time, the reader knows they can beat the antagonist and survive because they have the brains/strength/creativity, etc.

You could also write an enemies-to-lovers arc where it’s obvious to the reader that both characters are in love with each other long before they realize it. The reader should want them to embrace the scary feeling of falling in love, because that’s what you’re trying to teach through your story.

Consider Your Story’s Purpose

Writers have a purpose behind every story. What do you want readers to learn, consider, or experience through your own? You can use these methods of connecting with your reader’s emotions to make your plot’s purpose that much more powerful and engaging.

#emotional fiction#writing tips#writing advice#writing emotions#plotting#plotting tips#character creation

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

the best way to end a love triangle plot line is with polyamory

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tips - What Kind Of Writer Are You?

Not all writing tips work for everyone, you need to learn to give things a try and accept when they aren’t helpful. Ask yourself these questions to see what writing practices might work best for you - and be sure to experiment if you want a better understanding!

1. Does your word count motivate or discourage you?

If seeing your word count motivates you, stick it everywhere! I like to constantly check word counters, add up my chapter word counts, section word counts and total word count, calculate what my word count will be by the time I’m done with my current writing session, etc

But if the word count is intimidating and discouraging to you, like it is to many people, measure your productivity by time spent on your project rather than the word count; dedicate a certain amount of time to the project every day/week/whatever works for you, try writing sprint videos on YouTube, anything that doesn’t mention your word count. It can always be edited later on

2. How much/often can you write before it’s a chore?

It’s well-known that the vast majority of people can’t consistently keep up with NaNoWriMo’s 1667 words per day practice, so how far can you push the metrics before it gets overwhelming? I personally find that writing daily isn’t something I can do without it feeling like I’m forcing myself to do a task rather than engaging in a fun project, but I can commit easy enough to meeting a weekly goal. At the moment I’m on 1000 words per week, but you can also change how many words are needed, you just need to be able to consistently meet said goal without feeling overwhelmed by it, even if it feels too small

3. Where do you fall on the plotter scale?

A true pantser has no plan for their story and goes in head-first with a confidence I envy - a good amount of writers aren’t that. Chances are you’re a plotter of some variety, but how much so? It’s always worth testing the waters with how much or how little you can work with as a set plan. Personally, I like to plot five chapters in advance and then write them before plotting the next five - it gives me the freedom to see where my writing deviates from my anticipated plan and adapt it from there, which has been critical to many big changes in the story

#question#quiz#plotting#pantsing#writing#writers#writeblr#bookblr#book#my writing#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#original#writers of tumblr#how to write#on writing#creative writing#writing prompt#writer#write#writers and poets#writblr#female writers#writer things#writerscreed#writing is hard#writing advice#writing life#original writing#writer problems

104 notes

·

View notes

Note

I noticed many of the protagonists I wrote or thought of writing had either no personality or one too self-inserted (sometimes somewhere in between) and now I can't really connect with the protagonists I write so I wanted to know if you have any advice to help me craft more distinct characters and get attached to them.

First, some homework - pluck out about five pieces of media and nail down what you like about the protagonists within.

What about them appeals to you in particular?

Did you like how they grew and changed?

What struggles did they tackle that only they could handle?

Doesn't have to be neat and orderly, just try to nail down what really appeals to you about your favorite characters. When it comes to your own characters, here are some more things to think about:

Are you writing the character you want to write, or are you writing the character you think you should write? You may not be able to connect to your characters because you're trying to make them something you think they should be rather than what you'd feel more comfortable writing.

Are you projecting your feelings on a larger canvas (aka write what you know)? Are you thinking about how your characters would feel in bombastic circumstances (fighting a dragon, running from the cybercops) based on experiences and emotions you've had (facing off with a teacher, hopefully not running from the real cops but hey, you do what you gotta). The best way to infuse your characters with appeal is to take an emotion or an experience you can relate to and projecting it onto your characters.

Do your characters have internal struggles to go with their external ones? Is that high-stakes heist also paired with the character's struggle to display his real emotions? Does the fight with the evil wizard reflect the character's struggles to connect to their dad? If your story is external-plot heavy, a good way to flesh out the characters within is to connect their internal wants/needs/desires with the events going on around them. That zombie fight could be all the more enticing if the main couple is having a massive break-up during it.

Figuring out how to write a protagonist is often more than filling out a character sheet. Great if you can do that (I can't so like, go brag about it somewhere else), but often times you'll have to flesh out the character the hard way, but plotting out their journey before you write it. Work on their inner needs and emotional battles to draw them out as people.

Don't know where to start with figuring out a character at all? Grab an archetype list and get mixing and mashing. You may not come up with usable ideas right away, but you'll be able to pick out the ideas that appear to you until you have a handy list of things to lean on. Tropes are tools to be used, after all, and anything that could add to your characters is a tool with keeping. Good luck!

499 notes

·

View notes