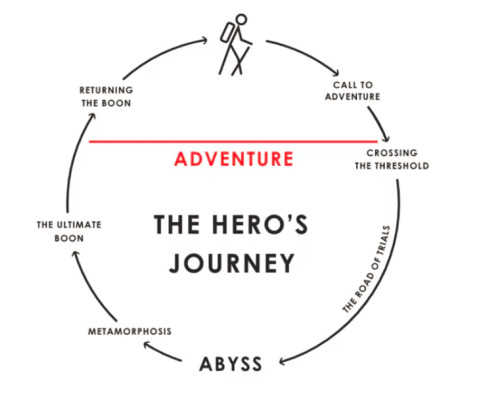

#with an arc that your character(s) need to experience to learn an element (for characters who have yet to understand the pure

Text

you know im starting to think that all this mulling over the disparity and intersectionality inheret to yin and yang and the four elements is less of a hobby funtime hyperfixation and more like a. im discovering the source of my ideology and spirituality

#talk#recently ive been realizing that playing with the different combinations of#active yin and yang (the self. action. by the means of. water and fire)#and passive yin and yang (the world. perception. for the purpose of. earth and air)#and the different paths that a person can take on their journey to reach understanding of all four elements#is a fantastic way to imagine up three dimensional characters. locations. histories. cultures. arcs. stories.#even after achieving all four elements; how do the elements that a character began with that most identify that character?#which elements does a person have? which elements are they missing? how does this create conflict?#line up the elements of a locale (a vast night city. practically unknowable via all its small pieces but easily perceptible as a whole.#THE WORLD. the earth is the foundation of the city. buildings. networks. infrastructure. the air is the freedom of the city.#people doing as they please. gusts of wind blowing on rooftops. lights beaming and flickering separately but as a whole)#with an arc that your character(s) need to experience to learn an element (for characters who have yet to understand the pure#vastness of the world [no earth or air]. for characters who love the freedom but cant stand the form that its built on [only air].#for characters who are familiar with the infrastructure but dont know how to set themselves loose into what it offers [only earth].#and then characters who are equipped to embrace the city in full and offer guidance to the other characters when prompted [earth and air])#ive been setting my mind LOOSE in it and the ONLY thing that i get is interesting and dynamic and real ideas.#it is an absolute story building gold mine and it is by design that its a gold mine

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please explain how you can like b*ruto while criticizing it at the same time we're confused. And then you write about adult nar/sas/ even though they've done the worst. How can you say that era is so great? Just tryna understand here. Usually I get your logic but not this. Also when you think it s done?

Hi Non.e, when did I say that?

I said, I felt like 'Boruto' as a show had a lot of potential. And what I mean with that is that I feel like Kishimoto was definitely on to something with the movie when it comes to a major storytelling element which is 'Theme'. But also the change the world itself had undergone when it comes to technology. How incredibly frustrating it must be how these gremlins suddenly lack the motivation to train because they can simply get every Jutsu they need in a damn mini-scroll anyway. People don't even need any Chakra anymore. It's like people skip the process to get to an end-result as fast as possible. Does it sound familiar??????

That's huge!!

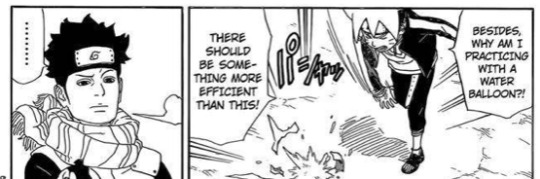

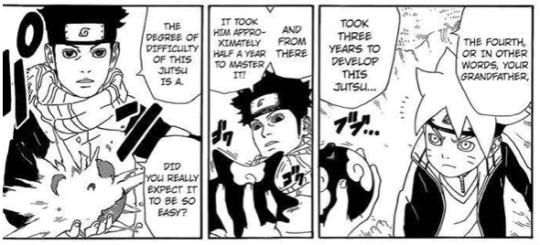

And for some reason these kids learn Jutsu fast as hell.

The kid learns a damn Rasengan immediately. Like in what, 2 days?

This dystopian, cyberpunk'ish-type of vibe has so much potential for so many interesting arcs despite the bitter edge it gives.

But like.. the writers don't even give a damn it seems like. It's almost as if Kishimoto wants to take advantage of the potential but is tired of it too. When things don't go your way or when the people around you don't value the same things.. I mean, I'm just speculating.

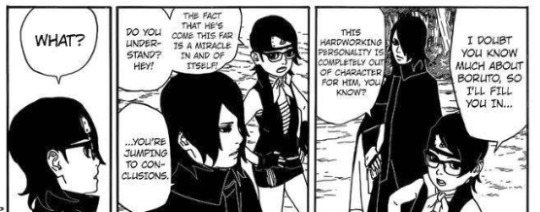

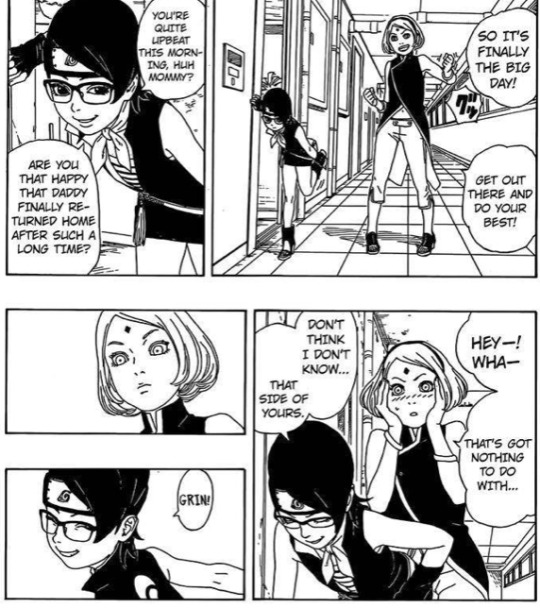

And even if I like the SNS moments, there are parts in the movie and the beginning of 'Boruto' that I really, severely dislike too. You wouldn't hear/read me say that 'Boruto' is great in any way. I liked Sarada in Gaiden for example but she's annoying as hell in 'Boruto'. Her obsession with her father makes me uncomfortable. These kids are literally out of nowhere lecturing Sasuke... Boruto bolts after cutting Sasuke off and Sarada jumps in trying to be all sassy towards her father.

"Do YoU uNdErsTand? HeY!" They irritate me. Have some respect gdi.

Sasuke whose adult character sketches from Kishimoto looked absolutely amazing. Who is at the end of Shippuden together with Naruto one of the most powerful Shinobi and forced to get nerfed to favor an out-of-balance power-scale. One that doesn't even make sense in the slightest. Not even with technology. Whose eyes who see everything can't even see a kid with a kunai coming.

No wonder ms. experiment needs glasses. LoGic. Idc.

And it's not just that, the way they're drawn too...

They're talking about Sasuke, yet the visual focus is so much on Sarada's bare legs in that tiny, TINY dress. Creepy as hell. BARF.

Mind you, I just took your hand briefly and showed you a few panels from just the first 2 Chapters. There are infinitely more moments that annoyed me. The writing is bad, it's visual representation is bad, I don't like these kids although Boruto's growth as a character is okay (I haven't caught up yet)- I'll say it again, you will not hear/read me say that 'Boruto' is great. Ever.

But the world and the era had potential. That's all.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Do I Plan? Tag

Thank you, @elizaellwrites for the tag! Much appreciated.

How do you plot your writing?

Step 1: Beginning with the Characters

No matter how hard I try to start with a plot idea, the characters usually come first (though, this was not the case for my second novel – the plot came first, but I digress). I could be working or simply reading a story and the inspiration for my characters for my own novel(s) run through my mind. Inspiration may also strike when listening to a song, looking at art, in thinking back to my own past experiences – certain traits about them stand out to me, and automatically, I begin to construct a character based on even the simplest of details. If I can’t get it down on paper immediately, I try to make a mental note of the strongest elements that stand out to me about that character. Then I begin to develop them from there.

Step 2: Research for the Fictional World

Once I’ve created the characters, I tend to rush straight into developing the fictional world. I jot down my ideas (those that I call “cold ideas;" they're without research, only based on my initial thoughts) and determine what could work and not work for my world, for my characters. Research follows swiftly after. I go into a “research frenzy” for months at time (depending on how big my fictional world is and what I decide to put my characters through) before even putting a pen to paper. For my current fantasy series, I spent about 2-3 years researching before I began my first draft. I file all my research and return to it when needed. Even the simplest details are filed away. Once I’ve gotten a general idea of how I want my fictional world to look, I begin to look at the plot.

Step 3: Development (mixing plot, world-building, and characters together)

This is where I begin to mix plot, world-building, and my characters. Always, I ask “What if…?” about a particular theme/issue that I want to address within my plot, and I go from there when working on the plot. I ask the same question of my characters, when fitting the plot around them. If something in the plot doesn’t fit with how I perceive the characters, then I make changes (either to the character or to the plot itself). I also consider how the world I’ve created will affect the plot. I only spend a few weeks to a few months here at a time, creating a rough map of how I want things to go.

Step 4: Outlining

I’ve always hated outlining, but I find that it’s extremely useful, even if writing a short story. I tend to outline in detail, as I like to get all my thoughts out on paper about how a character arc will progress, how the plot will progress, how each affects others in the story. Then I go back and tweak it as I see fit. Of course, outlining doesn’t mean I’m not open to surprises; I am. They generally come, of course, in the writing process itself.

Step 5: Writing

After going back over my notes for weeks to months, I then sit down to write. Surprises, as stated earlier, can happen here. Rewrites happen in increments – if I’m not satisfied with a current chapter in my novel (even if I’m in the first draft phase), I go back and I rewrite it again. The refining and editing process can take a while, so I’ve learned to be patient with myself and remind myself that not everything is going to be perfect on the first – or even second and third – attempt.

What is your favorite part of the writing process?

I have two favorite parts – Constructing my characters/my world, and the writing process itself. With constructing characters, I love seeing how each come together and compliment (or not) one another. I love determining their dynamics, their personalities, their quirks, histories, relationships…you name it. I love making them feel more human, more relatable to my audience. I love seeing how they grow and how they progress over the course of the novel(s), how they mature and change.

In the writing process, I can finally see how everything comes together. I can see where there are plot holes (if I didn’t see them earlier), I can finally see, in written form, how each character interacts with one another or with their environment. I adore seeing if the world I’ve created takes precedence or takes more of a background role (in my books, I’m finding it does more of the latter, but is still…present). I love seeing when the draft (even if it’s the first) is done, and I’m holding a physical copy of it in my hands. Just knowing that a draft is complete is so rewarding.

0 notes

Text

Why did you write two versions of Hunger Pangs?

What’s the difference and is one more “valid” than the other?

I get a lot of questions when people find out I wrote two versions of Hunger Pangs (Phangs). To answer that second question first, the only difference is that one contains explicit sexual content, and the other merely alludes to it.

The Flirting with Fangs edition (red cover) contains multiple scenes that depict sexual acts, either solo or partnered. (link)

The Fluff and Fangs edition (blue cover) is less explicit. I say less because while the scene(s) fade to black, some elements of physical affection are still shown, along with a fairly involved conversation about consent and kink. This is in the latter half of Chapter 28, and as noted on my website, you can skip this part if it makes you uncomfortable and not miss anything important to either the plot or character development. (link)

Both versions contain heat ratings and content warnings on my website. I can’t put it in/on the books themselves because Amazon is going after authors for mentioning content warnings (link), so when in doubt, check www.joydemorra.com or send me a message!

And no, one version is not more “valid” than the other. Both are canon. If it helps, think of them as parallel universes running side by side down the narrative timeline. The plot and character development remain the same; the scenes have just been altered to accommodate reader preference.

Then why do this at all?

As stated above, I wrote two different versions primarily to accommodate reader preference. When I first started writing Hunger Pangs: TLB, I was widely known on Tumblr for being “that erotica editor.” (link) I used to be a ghostwriter for my publishing house, too, so chances are some of you have already read my work under another author’s name*. A large chunk of my professional life has been spent writing sexually explicit content. It’s what I was then known and popular for, so it never occurred to me that anyone who was sex averse or didn’t enjoy reading about sex would be interested in my work.

And then those exact people started messaging me to let me know they were super excited about my work, couldn’t wait to buy a copy and would just skip past the sex parts that made them uncomfortable.

And that didn’t sit right with me.

Phangs is a bit of a weird project. It was started via a Tumblr shitpost (link) and grew from there. It was funded entirely by the support of my Patreon, which people kept supporting even after it took me years longer to finish it than initially planned because my health took a proverbial nose dive into the tenth circle of hell. It is not an exaggeration to say my Patreon and Tumblr kept me alive during that time. You kept our lights on and put what little food I could eat into my fridge. You supported me both physically and emotionally during one of the worst times of my life. And during that time, I wrote the entire Phangs series, assuming it would be edited and published posthumously**. It was both my swan song and a parting gift. A means of saying thank you for all your support over the years and the fervent hope you’d feel my love on every page. Because never doubt this, I wrote Phangs for you. Phangs is a love letter to fandom from start to finish. It’s written specifically to appeal to fandom and all the things we love about it.

So when people told me they were going to buy it but skip parts of it, I felt the need to make sure they were getting equal amounts of content for their money. So the “fluff” version of the narrative was born, replacing the sex-based scenes with more emotional and “fluffy” but still intimate interactions that keep the character arcs and plot intact.

For the first book, I tried to keep the scenes as similar in theme as possible. That’s why Chapter 28 still features a frank discussion around kink and consent, as a large part of Vlad’s character arc is learning that his wants and desires matter, but more importantly, so do his boundaries. But I also purposefully wrote it so that you can skip away after that conversation and not miss anything in the lead-up to the fade to black/implied sex scene. As the series progresses, the scenes may differ more as I play around having fun with it. But the fact remains that the characterization and plot will always stay true.

It’s merely about what kind of reading experience you want.

Do I expect other authors to do this? Absolutely not. This is a labor of love. The “fluff” version being popular is merely a bonus that enables me to keep writing. So thank you. I’m off to keep working on the next story.

*Before anyone asks, no, I can’t tell you who. I signed NDAs that are still in effect.

**Jokes on me, I guess because I lived, and now I have to edit and rewrite all 500-f*cking-k of it.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

INTERVIEW NO. 1: RACHEL @djarinsbeskar

hello hello! i am so happy to announce that rachel — aka the immense talent that is @djarinsbeskar — has agreed to be my first interviewee for this new series! thank you to rach and to each one of you for all of your support. to read more about the project, click here, and to submit an author, click here.

| why rachel? |

Rachel captured my imagination from the first time we interacted as mutuals-in-law. She’s bursting with energy and vivaciousness, with a current of kindness just underneath everything she does. Her work is no exception. Oftentimes gritty, raw, and exposing (in … ahem…more ways than one), Rachel challenges her readers to dig deeper into both the story and themselves. Her smut brings a particular fire as it’s laced with need, desire, and mutual trust that leads us deeper into the characters’ identities and how physical affection can mimic other forms of intimacy. She’s a tour de force in this fandom and an absolute joy.

| known for |

Engaging with and encouraging other authors, cultivating inspo posts, attention to world building & character development

| my favorites |

Stitches

Boxer!Din

Full Masterlist • Ko-Fi

| q & a |

When did you start writing? What was that project, and what was it like? Has that feeling or process ever changed over time? Why?

I can’t remember a time I wasn’t writing. I was an avid reader, as I think most writers are—and I remember, after picking up Lord of the Rings—that I could live so many lives, experience so many things, all from the pages of a book. I could make sense of the world through words and ink and paper. And it offered me a level of peace and clarity I wanted to share with others. So, I started writing.

My first project I remember to this day, was a short story about a dog. I had been so heartbroken when I learned that dogs were colourblind. I must have been about seven or eight at the time, and I was fixated on this idea that dogs couldn’t see the vibrant hues that made the world beautiful. It was something I wanted to change—and with all the righteous anger of a child not getting their own way, I sulked over the fact that I couldn’t. Until I wrote it down.

“How do dogs see colour?”

And much like my writing today, I answered myself.

“Dogs don’t need to see colour. Dogs smell colour.”

And so, I wrote a story, about a puppy being brought on different walks by its owner. And with every new street it walked down—colour bloomed with scent. Colours more beautiful and vibrant than we could ever hope to see with our eyes. And it gave me solace and helped me work through an emotion that – granted was immature and inconsequential – had affected me. To this day, I still smile seeing dogs sniffing at everything they pass on their walks. Smelling colour. It gave me the key to my favourite thing in life. I don’t think my process has changed much since then. Much of what I write is based on a skeleton plan, but I leave room for characters to speak and feel as they need to. I like to know the starting point and destination of a chapter—but how they get there, that still falls to instinct. I think I’ve found a happy medium of strict planning and winging it that suits me now—and hopefully it will continue to improve over time!

When did you start posting your writing, and on what platform? What gave you the push to do that?

I mean, fanfiction has always been part of my life. I think anyone who was growing up in the late 2000’s and early 2010’s found their way to fanfiction.net at some time or other. The wild west compared to what we have now! My first post was for the Lord of the Rings fandom on fanfiction.net. It was an anthology of the story told through the eyes of the steeds. Bill the Pony, Shadowfax—it was all very innocent. That was probably in 2010 when I was fifteen. I had been wanting to share writing for a long time but was worried about how it would be received. I didn’t really have a gauge on my level or my creativity and – one of the many flaws of someone with crippling perfectionism – I only ever wanted to provide perfection. That was a major inhibitor when I was younger. By wanting it to be perfect, I never posted anything. Until that stupidly cute LOTR fic. It was freeing to write something that no one but me had any interest in, because if I was writing for myself then there was no one to disappoint, right? And that was all it took. I had some pauses over the years between college and life and such, but I’ve never lost that mindset when it comes to posting.

What your favorite work of yours that you have ever written? Why is it your favorite? What is more important to you when considering your own stories for your own enjoyment — characters? fandom? spice? emotional development? the work you’ve put into it? Is that different than what you enjoy reading most in other people’s fics?

I don’t think it’ll come as much of a surprise when I say Stitches. While not original, I mean—it follows the plot of the Mandalorian quite diligently, it is the piece of work I really hold very close to my heart. Din Djarin as a character is what got me back into writing after what must have been five years? He inspired something. His manner, his personality—he resonated with me as a person in a way I hadn’t felt in a long time. And gave me back a creative outlet I had been missing.

It’s funny to say out loud—but I wanted to give him something? I spent so long thinking about his character that half my brain felt like it belonged to him—how he reacted and responded to things etc. and of course, like every dreamy Pisces—I wanted to give him love and happiness. So, Stitches came along. Personally, when writing—it’s a combination of characters, emotional development and spice (I can’t help myself) and when we can follow that development. With Stitches, it’s definitely the spice that is the conduit for development—but I adore showing how the physical can help people who struggle to communicate emotions too complex for words.

I don’t usually read for Din, as most people know—but I do enjoy reading the type of work that Stitches is. Human, damaged—but still with an undercurrent of hope that makes me think of children’s books.

You said, “much like writing today, I answered myself.” Could you talk about that in relation to Stitches?

So, I’m endlessly curious, it has to be said. Especially about why people are the way they are. Why people do A instead of B. Why X person’s immediate thought went to this place instead of that place. And I’m rarely satisfied with superficial explanations. One of the most exciting parts of writing and fanfiction especially, is making sense of that why. There can be countless explanations, some that are content with what is seen on the surface and some that go deep and some that go even deeper still.

Stitches is almost a – very long winded and much too long – answer to the questions I was so intrigued by about Din Djarin, about the Mandalorian and about the Star Wars universe as a whole. I often wondered what happened to people after the Rebellion, the normal people who fought—the people in the background. What did they do next? Did some of them suffer from PTSD? What was the galaxy like right after the Empire fell? That first season of the Mandalorian answered some of those questions, but I wanted to know more. So, I created a reader insert who was a combat medic—and through her, I let myself answer the questions of what happened next.

Regarding Din as a character, I wanted to know what a bounty hunter with a code of honour would do in certain situations—what made him tick, what made hm vulnerable. I wanted to explore the discovery of his identity. Din Djarin didn’t exist after he was taken from Aq Vetina. He became a cog in a very efficient machine of Mandalorians—and it was safe there. I wanted to see what – or who – might encourage him to step into his own. Grogu was that person in a familial sense, but what about romantically? What about individually? There’s so much to explore with this man! So many facets of personality and nuances of character that make him so gorgeous to write and think about.

Talk to me about the Din Djarin Athletic Universe. How does Din as all of these forms of athlete play off who you see him as in canon?

The Athletic Universe! How I adore my athletes. Despite being in a modern setting, I have kept the core of Din’s character in each of them (at least I hope I have!). I like to divide Din’s character into three phases when it comes to canon because he’s not as immovable as people seem to think he is. We discussed this before, how I see Din as a water element—adaptable, but strong enough that he can be as steadfast as rock. But I digress, the first phase is the character we see in the first episode. Basically, before Grogu. There’s an aggressive brutality to Din when we see him bounty hunting. He works on autopilot and isn’t swayed by sob stories or promises. He has the covert but is ultimately separate. Those soft feelings he comes to recognise when he has Grogu are dormant – not non-existent – but they haven’t been nurtured or encouraged. This is the point I extracted Boxer!Din’s personality and story from.

Cyclist!Din on the other hand—is already a father, a biological father to Grogu. And his personality, I took from that moment in the finale of Season two where I believe Din’s transformative arc of character solidified. He was always a father to Grogu, but I do believe that moment where he removes his helmet is the moment, he accepts that role fully in his heart and mind. And that is why I don’t believe for a second, that removing his helmet was him breaking his Creed. In fact, I believe it was the purest act he could do in devotion to his Creed—to his foundling, to his son. The Cyclist!AU is very much the character I see canon Din having should Grogu have stayed with him. This single dad who isn’t quite sure how he got to where he is now—but does anything and everything for his child without thought. It’s a natural instinct for him, and I like exploring those possibilities with Cyclist!Din.

You also said, “he has the covert but is ultimately separate.” What does it take for him — and you — to get to that point of being ‘not separate?’

I mentioned this above, but one of the biggest interests I have in Din as a character is his identity. He’s a Mandalorian, he’s a bounty hunter, he’s the child’s guardian but those are all what he is, not who. I think Din is separate while being part of the covert because he doesn’t know. I don’t think anyone can really be part of something if they don’t know who they are or, they struggle with their identity. It’s curious to me—how you can deceive even yourself to mimic the standard set for the many. In the boxer verse, he identifies himself in relation to his boxing—and every part of his outward personality exhibits those qualities. But when he’s given a softer touch—an outlet of affection, and comfort—we see the softer side of him surface. It’s very much the same with Stitches Din. Identity is like anything, emotions—relationships, bodies. It needs nurturing to thrive, an open door—a safe space. At least, that’s what goes through my mind when I think of him.

Who is your favorite character to read?

Frankie because there are so many ways his character can be interpreted and there are some stellar versions of him that I think of at least once a day. Javi because he reminds me of kintsugi-- golden recovery, broken pottery where the cracks are highlighted with gold. I also adore reading for Boba Fett, Paz Viszla and the clones!

Is there anything else you want your readers to know about you, your writing, or your creative process?

Hmm... only that I am quite literally a gremlin clown who is always here to chat Din, Star Wars, literature, book recs and anything else under the sun! I like to hear people's stories, their opinions etc. it helps me see things from alternative points of view and can truly help the writing process! Other than that, I think I can only thank readers for putting up with my ridiculously long chapters and rambling introspection. Thank you for indulging me always! ❤️

#pedro pascal#din djarin#the mandalorian#the mandalorian x reader#din djarin x reader#din djarin x f!reader#the mandalorian x f!reader#the mandalorian x you#din djarin x you#djarinsbeskar#chat with cris#author interview series#tuserdaniela#userastrid#usernobie#userhai#pedrostories

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m just really confused as to where this idea that Zuko is gaycoded came from. Like people are allowed to have that headcanon but I don’t understand where people are coming from when they try and claim that he was undisputedly gaycoded and trying to deny it is homophobic when he’s only ever shown romantic interest in women.

I made a pretty long post on the topic a while back, but the ultimate gist of it is this: there are a lot of elements of Zuko's status as an abuse victim and trauma survivor that resonate with queer folks. This is understandable and completely fine! However, there are some parts of the fandom who have taken that to the other extreme and will now insist that those elements are uniquely queer, and that they can only be read as some sort of veiled gay/coming out narrative, even though that doesn't make much sense since there is no part of Zuko's narrative which is unique to any sort of queer experience.

I think the problem really does stem from two things being conflated--Zuko's history of abuse and trauma, and trauma&abuse being something a lot of queer people have experienced. I suspect it goes something like 'I see a lot of myself in Zuko, and I was abused for being gay, therefore Zuko must be gay too in order to have had similar experiences.' This can then lead to feeling dismissed or invalidated when other people point out that those experiences are not unique to being queer--but on the flip side, abuse victims and trauma survivors whose abuse&trauma do not stem from queerness (even if they are queer themselves) can feel invalidated and dismissed by the implication that their trauma must be connected to their queerness or it isn't valid.

This is also where the 'people don't actually know what gay coded means' part comes in, and I realize now that I didn't actually get into what gay coding (and queer coding in general) actually means, since I was so hung up on pointing out how Zuko doesn't really fit the mold. (And the few elements that exist which could be said to count are because of the 'villains historically get queer coded bc Hays Code era' thing and mostly occur in Book 1, not because of how he acts as an abuse&trauma survivor.)

Under a cut because I kind of go on a tangent about gay/queer coding, but I swear I get back to the point eventually.

Queer coding (and it is notable that, with respect to Zuko, it is almost always framed as 'he couldn't possibly be attracted to girls', rather than 'he could be attracted to boys as well as girls' in these discussions, for... no real discernible reason, but I'll get into that in a bit) is the practice of giving characters 'stereotypically queer' traits and characteristics to 'slide them under the radar' in an era where having explicitly queer characters on screen was not allowed, unless they were evil or otherwise narratively punished for their queerness. (See: the extant history of villains being queer-coded, because if they were Evil then it was ok to make them 'look gay', since the story wasn't going to be rewarding their queerness and making audiences think it was in any way OK.) This is thanks to the Motion Picture Production Code (colloquially and more popularly known as the Hays Code), which was a set of guidelines which movies coming out of any major studio had to adhere to in order to be slated for public release and lasted from the early 1930s until it was finally abandoned in the late 60s.

The Hays Code essentially existed to ensure that the content of major motion pictures would not 'lower the moral standards' of the viewing public. It didn't just have to do with queerness--cursing was heavily monitored, sex outside of marriage was not allowed to be seen as desirable or tittilating, miscegenation was not allowed (most specifically interracial relationships between black and white people), criminals had to be punished lest the audience think that it was ok to be gay and do crime, etc. Since same-sex relations fell under 'sexual perversion', they could not be shown unless the 'perversion' were punished in some way. (This is also the origin of the Bury Your Gays trope, another term that is widely misunderstood and misapplied today.) To get around this, queer coding became the practice by which movies and television could depict queer people but not really, and it also became customary to give villains this coding even more overtly, since they would get punished by the end of the film or series anyway and there was nothing to lose by making them flamboyant and racy/overly sexual/promiscuous.

Over time, this practice of making villains flamboyant, sexually aggressive, &etc became somewhat separated from its origins in queer coding, by which I mean that these traits and tropes became the go-to for villains even when the creator had no real intention of making them seem queer. This is how you generally get unintentional queer-coding--because these traits that have been given to villains for decades have roots in coding, but people tend to go right to them when it comes to creating their villains without considering where they came from.

Even after the Hays Code was abandoned, the sentiments and practices remained. Having queer characters who weren't punished by the narrative for being queer was exceptionally rare, and it really isn't until the last fifteen or so years that we've seen any pushback against that. Buffy the Vampire Slayer is famous for being one of the first shows on primetime television to feature an explicitly gay relationship on-screen, and that relationship ended in one of the most painful instances of Bury Your Gays that I have ever personally witnessed. (Something that, fourteen years later, The 100 would visually and textually reference with Lexa's death. Getting hit by a bullet intended for someone else after a night of finally getting to be happy and have sex with her s/o? It wasn't remotely subtle. I don't even like Clexa, but that was incredibly rough to witness.)

However, bringing this back to Zuko, he really doesn't fit the criteria for queer coding for a number of reasons. First of all, no one behind the scenes (mostly a bunch of cishet men) was at all intending to include queer rep in the show. This wasn't a case where they were like 'well, we really wanted to make Zuko gay, but we couldn't get that past the censors, so here are a few winks and a nudge', because it just wasn't on their radar at all. Which makes sense--it wasn't on most radars in that era of children's programming. This isn't really an indictment, it's just a fact of the time--in the mid/late 00s, no one was really thinking about putting queer characters in children's cartoons. People were barely beginning to include them in more teen- and adult-oriented television and movies. It just wasn't something that a couple of straight men, who were creating a fantasy series aimed at young kids, were going to think about.

What few instances you can point to from the series where Zuko might be considered to exhibit coding largely happen in Book 1, when he was a villain, because the writers were drawing from typically villainous traits that had historically come from queer coding villains and had since passed into common usage as villainous traits. But they weren't done with any intention of making it seem like Zuko might be attracted to boys.

And, again, what people actually point to as 'evidence' of Zuko being queer-coded--his awkwardness on his date with Jin and his confrontation with Ozai being the big ones I can think of off the top of my head--are actually just... traits that come from his history of trauma and abuse.

As I said in that old post:

making [zuko’s confrontation of ozai] about zuko being gay and rejecting ozai’s homophobia, rather than zuko learning fundamental truths about the world and about his home and about how there was something deeply wrong with his nation that needed to be fixed in order for the world to heal (and, no, ‘homophobia’ is not the answer to ‘what is wrong with the fire nation’, i’m still fucking pissed at bryke about that), misses the entire point of his character arc. this is the culmination of zuko realizing that he should never have had to earn his father’s love, because that should have been unconditional from the start. this is zuko realizing that he was not at fault for his father’s abuse--that speaking out of turn in a war meeting in no way justified fighting a duel with a child.

is that first realization (that a parent’s love should be unconditional, and if it isn’t, then that is the parent’s fault and not the child’s) something that queer kids in homophobic households/families can relate to? of course it is. but it’s also something that every other abused kid, straight kids and even queer kids who were abused for other reasons before they even knew they were anything other than cishet, can relate to as well. in that respect, it is not a uniquely queer experience, nor is it a uniquely queer story, and zuko not being attracted to girls (which is what a lot of it seems to boil down to, at the end of the day--cutting down zuko’s potential ships so that only zukka and a few far more niche ships are left standing) is not necessary to his character arc. nor does it particularly make sense.

And, regarding his date with Jin:

(and before anyone brings up his date with jin--a) he enjoyed it when she kissed him, and b) he was a traumatized, abused child going out on a first date. of course he was fucking awkward. have you ever met a teenage boy????)

Zuko is socially awkward and maladjusted because he was abused by his father as a child and has trouble relating to people as a result. He was heavily traumatized and brutally physically injured as a teenager, and it took him years to begin to truly recover from the scars that left on his psyche (and it's highly likely, despite the strides he made in canon, that he has a long way to go, post series; it's such a pity that we never got any continuation comics >.>). He was not abused for being gay or queer--he was abused because his father believed he was weak, and part of Zuko's journey was realizing that his father's perception of strength was flawed at its core. That his entire nation had rotted from the inside out, and the regime needed to be changed in order for the world--including his people--to begin to heal.

That could be commingled with a coming out narrative, which is completely fine for headcanons (although I personally prefer not to, because, again, we have more than enough queer trauma already), but it simply doesn't exist in canon. Zuko was not abused or traumatized for being queer, and his confrontation with Ozai was not about him coming out or realizing any fundamental truth about himself--it was about realizing something fundamental about his father and his nation, and making the choice to leave them behind so that he could help the Avatar grow stronger and force things to change when he got back.

TL;DR: at the end of the day, none of the traits, scenes, or behavior Zuko exhibits which shippers tend to use to claim he was gay-coded are actually evidence of coding--they aren't uniquely queer experiences, as they stem from abuse that was not related in any way to his sexuality, and they are experiences that any kid who suffered similar abuse or trauma could recognize and resonate with. (Including straight kids, and queer kids who were abused for any reason other than their identity.) And, finally, Zuko can be queer without erasing or invalidating his canon attraction to girls, and it's endlessly frustrating that the 'Zuko is gay-coded' crowd refuses to acknowledge that.

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life is Strange: True Colors

Leading up to the release of Episode 1 of TellTale's The Walking Dead game, I was working freelance for GameRevolution at the time, lived in the area, and had the chance to play a build of the game to write a preview on it. I remember comparing it to Mass Effect because, at the time, there just...weren't games of that subgenre. Of course, by now we've seen an explosion of this type of game - the 'narrative/choice-driven game,' spearheaded and even oversaturated by Telltale to their own demise.

Out of all of the games that have come from that initial boom, Life is Strange by DontNod was and still is the most influential on my life, but I also have always harbored really conflicted feelings about it - especially with how it resolved its narrative. Hell, if you're reading this, you're probably aware that I spent a few years of my life creating a sequel fanstory which I even adapted a chunk of into visual novel format. Hundreds of thousands of words, days and days of life spent essentially trying to process and reconcile my conflicted feelings about this game's conclusion(s). Since then, I've been experimenting with interactive fiction and am currently developing my own original visual novel using everything I've learned from both creating and playing games in this genre. It's a subgenre of game I have a lot of interest and passion for because, when handled well, it can allow a player to sort of co-direct a guided narrative experience in a way that's unique compared to strictly linear cinematic experiences but still have a curated, focused sense of story.

Up until this point, I've regarded Night in the Woods as probably the singular best game of this style, with others like Oxenfree and The Wolf Among Us as other high marks. I've never actually put any Life is Strange game quite up there - none of them have reached that benchmark for me, personally. Until now, anyway.

But now, I can finally add a new game to that top tier, cream of the crop list. Life is Strange: True Colors is just damn good. I'm an incredibly critical person as it is - and that critique usually comes from a place of love - so you can imagine this series has been really hard to for me given that I love it, and yet have never truly loved any actual full entry in it. I have so many personal issues, quibbles, qualms, and frustration with Life is Strange: with every individual game, with how it has been handled by its publisher (my biggest issue at this point, actually), with how it has seemingly been taken away from its original development studio, with how it chooses to resolve its narratives...

But with True Colors, all of those issues get brushed aside long enough for me to appreciate just how fucking well designed it is for this style of game. I can appreciate how the development team, while still clearly being 'indie' compared to other dev teams working under Square-Enix, were able to make such smart decisions in how to design and execute this game. Taken on its own merits, apart from its branding, True Colors is absolutely worth playing if you enjoy these 'telltale' style games. Compared to the rest of the series, I would argue it's the best one so far, easily. I had a lot of misgivings and doubts going in, and in retrospect, those are mostly Square-Enix's fault. Deck Nine, when given the freedom to make their own original game in the same vein as the previous three, fucking nailed it as much as I feel like they could, given the kinds of limitations I presume they were working within.

I'm someone who agonizes every single time there is news for Life is Strange as a series - someone who essentially had to drop out of the fandom over infighting, then dropped out of even being exposed to the official social media channels for it later on (I specifically have the Square-Enix controlled channels muted). I adore Max and Chloe, and as a duo, as a couple, they are one of my top favorites not just in gaming, but in general. They elevated the original game to be something more than the sum of its parts for me. And while I have enjoyed seeing what DontNod has made since, it's always been their attention to detail in environmental craftsmanship, in tone and atmosphere, which has caught my interest. They're good at creating characters with layers, but imo they've never nailed a narrative arc. They've never really hit that sweet spot that makes a story truly resonate with me. Deck Nine's previous outing, Before the Storm, was all over the place, trying to mimic DontNod while trying to do its own things - trying to dig deeper into concepts DontNod deliberately left open for interpretation while also being limited in what it could do as a prequel.

But with True Colors, those awkward shackles are (mostly) off. They have told their own original story, keeping in tone and concept with previous Life is Strange games, and yet this also feels distinctly different in other ways.

Yes, protagonist Alex Chen is older than previous characters, and most of the characters in True Colors are young adults, as opposed to teenagers. Yes, she has a supernatural ability. And yes, the game is essentially a linear story with some freedom in how much to poke around at the environment and interact with objects/characters, with the primary mechanic being making choices which influence elements of how the story plays out. None of this is new to the genre, or even Life is Strange. But the execution was clearly planned out, focused, and designed with more caution and care than games like this typically get.

A smaller dev team working with a budget has to make calls on how to allocate that budget. With True Colors, you will experience much fewer locales and environments than you will in Life is Strange 2. Fewer locations than even Life is Strange 1, by my count. But this reinforces the game's theming. I suspect the biggest hit to the game's budget was investing in its voice acting (nothing new for this series) but specifically in the motion capture and facial animation.

You have a game about a protagonist trying to fit in to a small, tightly knit community. She can read the aura of people's emotions and even read their minds a little. And the game's budget and design take full advantage of this. You spend your time in a small main street/park area, a handful of indoor shops, your single room apartment. It fits within a tighter budget, but it reinforces the themes the game is going for. Your interactions with characters are heightened with subtle facial cues and microexpressions, which also reinforces the mechanic and theming regarding reading, accepting, and processing emotions. And you get to make some choices that influence elements of this - influenced by the town, influenced by the emotions of those around you, which reinforce the main plot of trying to navigate a new life in a small town community.

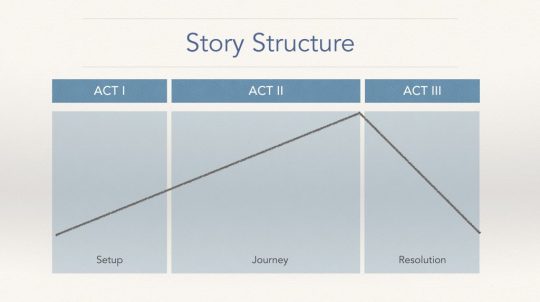

When I think about these types of games, the conclusion is always a big deal. In a way, it shouldn't be, because I usually feel it's about the journey, not the destination. And as an example, I actually really dislike the ending of the original Life is Strange. I think it's a lot of bullshit in many ways. The setpiece is amazing and epic, sure, but the actual storytelling going on is...really hollow for me. Yes, the game does subtly foreshadow in a number of ways that this is the big choice it's leading up to, but the game never actually makes sense of it. And the problem is, if your experience is going to end on a big ol' THIS or THAT kind of moment, it needs to make sense or the whole thing will fall apart as soon as the credits are rolling and the audience spends a moment to think about what just happened. When you look at the end of Season 1 of Telltale's The Walking Dead, it's not powerful just because of what choice you're given, but because through the entire final episode, we know the stakes - we know what is going to ultimately happen, and we know the end of the story is fast approaching. All of the cards are on the table by the time we get to that final scene, and it works so well because we know why it's happening, and it is an appropriate thematic climax that embodies the theming of the entire season. It works mechanically, narratively, and thematically, and 'just makes sense.'

The ending of Life is Strange 1 doesn't do that, if you ask me. The ending of most games in this genre don't really hit that mark. When I get to the end of most game 'seasons' like this, even ones I enjoy, I'm typically left frustrated, confused, and empty in a way.

The ending of True Colors, on the other hand, nails everything it needs to. Handily, when compared to its peers.

If you're somehow reading this and have not played this game but intend to, now is probably where you should duck out, as I will be

discussing SPOILERS from the entire game, specifically the finale.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Firstly, since I don't know where else to put this, some criticisms I found with the game. And honestly, they're all pretty damn minor compared to most games of this type.

Mainly, I just wish the whole Typhon thing was handled a bit more deliberately. It's a bit weird to do the 'big evil corporation' thing (especially when a big corporation like Square Enix occupies as much as or even more of the credits to this game than the people who actually MADE it?) without offering more explanation and subtlety. The game certainly makes some efforts but they're mostly small and mostly optional, like background chatter or a handful of one-off bits of documentation/etc. you can find in the environment. I feel like Diane in particular needed to be fleshed out just a little bit more to really sell us on how and why things like this happen, why corporations make decisions that cost people their happiness, security, and lives and they just get to keep on doing it. I think just a little bit that is unavoidable to the player that puts emphasis on maybe how much the town relies on the money/resources Typhon provides would've helped. Again, this is minor, but it stands out when I have so little else to critique.

I would've liked to get more insight on why Jed is the way he is. No, I don't think we really needed to learn more about his backstory, or even really his motivations. I think we get enough of that. I just think it would've been great to somehow highlight more deliberately how/why he's built up this identity overtop of what he's trying to suppress. Maybe even just having Alex internally realize, "Wait, what the hell, Jed has been hiding these emotions and my powers haven't picked up on it?" or something to that effect could have added an extra oomph to highlight how Jed seems to be coping with his emotions by masking/suppressing them. Also really minor complaint, but again...there's not much else here I can think to really improve on within the confines of what's in the game.

The game doesn't really call Alex's power into question morally. Like. Max has an entire meltdown by the end of her story, second-guessing if she's even helped anyone at all, if she has 'the right' to do so, how her powers might be affecting or expressing her own humanity and flaws...this story doesn't really get into that despite a very similar concept of manipulating others. There's like one bit in a document you can choose to read in Alex's 'nightmare' scene, but that's really it. I feel like this sentiment and how it's executed could have easily been expanded upon in just this one scene to capture what made that Max/Other Max scene do what it did in a way that would address the moral grayness of Alex's powers and how she uses them, and give players a way to express their interpretation of that. Also, very small deal, just another tidbit I would've liked to see.

When I first watched my wife play through Episode 5 (I watched her play through the game first, then I played it myself), I wasn't really feeling the surreal dreamscape stuff of Alex's flashbacks - which is weird, because if you're read my work from the past few years, you'll know I usually love that sort of shit. I think what was throwing me off was that it didn't really feel like it was tying together what the game was about up until that point, and felt almost like it was just copying what Life is Strange did with Max's nightmare sequence (minus the best part of that sequence, imo, where Max literally talks to herself).

But by the time I had seen the rest of the story, and re-experienced it myself, I think it clicked better. This is primarily a story about Alex Chen trying to build a new life for herself in a new community - a small town, a tightly knit place. Those flashbacks are specifically about Alex's past, something we only get teeny tiny tidbits of, and only really if we go looking for them. I realized after I gave myself a few days to process and play through the game myself that this was still a fantastic choice because it reinforces the plot reasons why Alex is even in the town she's in (because her father went there, and her brother in turn went there looking for him), and it reinforces the theme of Alex coming to accept her own emotions and confront them (as expressed through how the flashbacks are played out and the discussions she has with the image of Gabe in her mind, which is really just...another part of herself trying to get her to process things).

By the time Alex escapes the mines and returns to the Black Lantern, all of the cards are on the table. By that point, we as the audience know everything we need to. Everything makes sense - aside from arguably why Jed has done what he has done, but put a pin in that for a sec. We may not know why Alex has the powers she does, but we have at least been given context for how they manifested - as a coping mechanism of living a life inbetween the cracks of society, an unstable youth after her family fell apart around her (and oof, trust me, I can relate with this in some degree, though not in exactly the same ways). And unlike Max's Rewind power, the story and plot doesn't put this to Alex's throat, like it's all on her to make some big choice because she is the way she is, or like she's done something wrong by pursuing what she cares about (in this case, the truth, closure, and understanding).

When Alex confronts Jed in front of all of the primary supporting characters, it does everything it needs to.

Mechanically: it gives players choices for how to express their interpretation of events, and how Alex is processing them; it also, even more importantly, uses the 'council' as a way of expressing how the other characters have reacted to the choices the player has made throughout the game, and contributes to how this climax feels. We're given a 'big choice' at the end of the interaction that doesn't actually change the plot, or even the scene, really (it just affects like one line of dialogue Alex says right then) and yet BOTH choices work so well as a conclusion, it's literally up to your interpretation and it gives you an in-game way to express that.

Thematically: the use of the council reinforces the game's focus on community; and the way the presentation of the scene stays locked in on Alex and Jed's expressions reinforces its focus on emotion - not to mention that the entire scene also acts as a way to showcase how Alex has come to accept, understand, and process her own emotions while Jed, even THEN, right fucking at the moment of his demise, is trying to mask his emotions, to hide them and suppress them and forget them (something the game has already expressed subtly by way of his negative emotions which would give him away NOT being visible to Alex even despite her power).

Narratively: we are given a confrontation that makes sense and feels edifying to see play out after everything we've experienced and learned. We see Alex use her powers in a new and exciting way that further builds the empowering mood the climax is going for and adds a cinematic drama to it. No matter what decisions the player makes, Alex has agency in her own climax, we experience her making a decision, using her power, asserting herself now that she has gone through the growth this narrative has put her through. Alex gets to resolve her shit, gets to have her moment to really shine and experience the end of a character arc in this narrative.

Without taking extra time to design the game around these pillars, the finale wouldn't be so strong. If they didn't give us enough opportunities to interact with the townspeople, their presence in the end wouldn't matter, but everyone who has a say in the council is someone we get an entire scene (at least one) dedicated to interacting with them and their emotions. If they didn't implement choices in the scene itself, it would still be powerful but we wouldn't feel as involved, it'd be more passive. If they didn't showcase Alex's power, we might be left underwhelmed, but they do so in a way that actually works in the context through how they have chosen to present it, while also just tonally heightening the climax by having this drastic lighting going on. If they didn't have the council involved, we'd lose the theming of community. If they didn't have the foil of Alex/Jed and how they have each processed their emotions, we'd miss that key component. And if we didn't have such detailed facial animations, the presentation just wouldn't be as effective.

Ryan/Steph are a little bit like, in this awkward sideline spot during the climax? Steph always supports you, and Ryan supports you or doubts you conditionally, which is unsurprising but also ties into the themes of Ryan having grown up woven into this community, and Steph being once an outsider who has found a place within it. They're still there, either way, which is important. The only relevant characters who aren't present are more supporting characters like Riley, Ethan, and Mac. Ethan being the only one of those who gets an entire 'super emotions' scene, but that also marks the end of his arc and role in the story, so...it's fine. Mac and Riley are less important and younger, as well, and have their own side story stuff you have more direct influence on, too.

But damn, ya'll, this climax just works so well. It especially stands out to me given just how rarely I experience a conclusion/climax that feels this rewarding.

And then after that we get a wonderful montage of a theoretical life Alex might live on to experience. Her actions don't overthrow a conglomerate billionaire company. She doesn't even save a town, really. If the entire council thinks you're full of shit, Jed still confesses either way - because it's not up to the council whether he does this, it's because of Alex, regardless of player choice. Honestly, even after a playthrough where I made most choices differently from my wife, there weren't really many changes to that montage at the end. It'd have been great if it felt more meaningfully different, but maybe it can be. Even if not, the design intent is there and the execution still works. It's a really nice way to end the story, especially since it's not even a literal montage but one Alex imagines - again, her processing what she's gone through, what she desires, expressed externally for us to see it.

And for once, the actual final 'big decision' in a game of this type manages to be organic, make sense, and feel good and appropriate either way. You choose to either have Alex stay in Haven Springs and continue building her life there, or you can choose to have her leave and try to be an indie musician, with the events of the game being yet another chunk of her life to deal with and move on from (I haven't really touched on it, but music, especially as a way to express and process emotions, is a recurring thing, much like photography was in the original game, or Sean's illustrations in LiS2). For once, a climactic 'pick your ending' decision that doesn't feel shitty. It's pretty rare for this genre, honestly.

I could - and already have, and likely will - have so much more to say about this game and its details, but I really wanted to focus on touching upon a main element that has left me impressed: the way the entire game feels designed. It feels intentionally constructed but in a way that reinforces what it is trying to express as a story. It's not just trying to make people cry for the sake of 'emotions.' It is a game literally about emotions and it comes to a conclusion in a way that is clearly saying something positive and empowering about empathy and self-acceptance.

Storytelling is a craft, like any other, and it entails deliberate choices and decisions that can objectively contribute to how effective a story is for its intended audience.

A good story isn't something you find, after all.

It's something you build.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TL;DR warning: TFATWS Ep. 6 / Finale

There’s a lot to unpack in this series finale, and I sure as hell am not the expert to do this, but I thought I’d highlight some particular issues I have. Much of this, admittedly, will be coming from the high character tenors of the previous episodes, whereas this episode is really where the “MCU kind of movie denouement” kicks in. If you can call/criticize something as “Disney formula” writing, this might be it. Did it hamper/dampen my enjoyment of this series? Not THAT much, but it really stands out and suggests it could have been better.

So let me do a few numbers.

1. PRO: A very acceptable execution of selling not only Sam’s first outing as ‘Captain America’, not only the affirmation of Bucky Barnes’ commitment to heroism, but the apotheosis long-denied to Isaiah Bradley.

I’m getting the impression much of the gushing here in Tumblr will be focusing on that--and to an extent, I am in agreement. their characters were very well fleshed out and to be honest, I wouldn’t have it any other way. There may be still other things I would recommend as a better laid-out recognition for Isaiah (something more faithful to the Truth comic miniseries), but that’s a minor quibble compared to the others below.

2. CON: Falling into the trap of a “GOT-layout” series ending

Ok, that description might be too harsh. After all, point # 1 is near perfect.

However, and this is a very big HOWEVER...

A really good show does not rely solely on giving your main characters the best ending possible. Their supporting cast deserves at least a fair amount of character development (understandable motivations, a good appreciation of their character arcs, more moments which make you empathize with them especially if you are trying to experiment with moral ambiguity on their characters). The fact that the action sequence ate up more than half of the final episode’s near-50 minute runtime really prevented any further character development moments.

How, to some extent, this became insufficient with Karli Morgenthau and John Walker become really apparent in the end.

3. CON: Under-served Character Denouements

Karli and the Flag-Smashers, in practice, were basically given the “Killmonger” treatment: they’ll have to die, but the validity of their moral argument will be recognized. As someone with a very limited set of fandoms I follow, the only other place I’ve seen this done is Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans. The protagonist cast was left to die, but the tragedy of their situation led their world to improve things for the better. (For those familiar with this fandom, many will understand that this did not go down well.) Compare this, in turn, to how Breaking Bad gives even the supporting cast and side-characters understandable character endings.

The reason of complaint here, being, that this kind of story flow robs these characters of agency not only in their tragedy--but also how they choose to go out. Sympathetic tragic characters, to an extent, are at least given some dignity in how they go out. The fact that Karli and the Flag-Smashers are practically disposed of by a) Sharon, now fully revealed as the criminal Power-Broker and b) Zemo, whose butler is no less capable in extreme action even while he was in prison further highlights how they are basically reduced into ‘plot elements’, not a fully-realized group/faction of people.

John Walker, for his part, is also given very little to do (and indeed, what little he was able to do in the entire fight sequence is laughable). Even his one spark of “good choice” (seeking to save the falling vehicle’s occupants), even if he failed, was ultimately overshadowed by Sam’s more flamboyant rescue.

One might be able to make argument, perhaps, that that is the point: Walker’s arc in this episode, perhaps, is to finally learn why exactly he can’t become Captain America: because he remains primarily a soldier, and only good at that. Witnessing Sam arguing and pontificating in front of the cameras, perhaps, is what hammers it home to him--and why perhaps his last scene in the series is him accepting his new role as U.S. Agent. If his world is going to be small and he is going to be pigeonholed into what he is good at, so be it. If he can’t be Captain America (now that he knows why exactly that symbol is powerful, and what is required of it), he’ll find his way with people who will let him be what he can be.

Notice, however, how even between these two underserved characters, John Walker has a more understandable progression. I don’t think I’ll really be able to fault ‘left-wing’ viewers of the show who will be left dissatisfied by this ending (especially those who are sympathetic to the Flag-Smashers’ demands--especially as to some extent (due to my own line of work and leanings, I’m kind of one of those).

And then there’s the reveal of Sharon as the Power-Broker--its own can of worms, but I’ll fold it in the next item.

4. MIXED BAG: How the show’s social layout closes

The fact that the MCU’s undercurrent politics remains to be “institutions are bad, mob/grassroots action will always be misguided, let media-chosen/private individuals and orgs show you the ‘right way’ of doing things”--it isn’t really as helpful as it could be. The show basically ends with Sam and Bucky’s individual arcs and moral world-views affirmed. It is definitely a happy ending for them. It is, however, pretty difficult to swallow that it ends well for them when the bigger picture is left unaddressed. (For those who may be interested in this line of critique, this video essay, “Imagining the Tyrant” by Kyle Kallgren / Brows Held High / oancitizen should be helpful.)

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in 2 instances: the setting of Walker’s rechristening as U.S. Agent, and Sharon’s “pardon” scene--now that we know she is in fact the Power Broker. Both events happen in the U.S. Senate Committee hearing hall--basically making the statement that even with a new Captain America that is more ‘home-grown’ and closer to the ground and common people (even as he literally flies high), the institutions of the U.S. government is still as impervious and clueless to its corruption and enabling of crime and injustice. Criminal elements like Valentina de Fontaine and the Power Broker foster the underground economy with impunity, and the U.S. government allows them to for a number of unbuilt/unestablished reasons.

It’s a valid/backed-up argument to make, and with historical/real life basis at that, but this is the kind of plot development difficult to credibly sell within a 6-episode miniseries already crammed with character arcs--and it shows. Compare this, for example, with how the Netflix series The Punisher built throughout its Season 1 run how exactly can black market profiteering grow under the CIA in a believable way. There, you see exactly what needs to happen for a previously-established upstanding character living in a grey environment to turn grey--even full on black (be it Frank Castle/the Punisher himself, Dinah Madani, or even Billy Russo).

I’d want to chalk this up to the possibility of merging/reintroducing that world--and by god, imagine Jon Bernthal’s Punisher returning in this kind of gray area--interacting with Captain America AND the Winter Soldier, as this series is now likely to be titled--should be very interesting.

----

These are the top points in my head after my first watch of this finale. I may be rewatching this again--who knows if I get to come back. Still, it’s been a pretty meaningful ride.

P.S. I should probably admit to my Filipino background here again, but it’s hilarious how the closing shot of this series (Sam and Bucky having a party with their family/community near the Louisiana seaside) is basically how mosts 80′s/90′s era Filipino action and comedy films end (either a beach party or a wedding/outing near a beach/swimming pool). The presence of Pinoy shout-outs in this series (”Amatz” and “Isang Tao, Isang Mundo”) really emphasize how this might not be an accident.

#tfatws#the falcon and the winter soldier#sam wilson#bucky barnes#james buchanan barnes#sharon carter#helmut zemo#marvel cinematic universe#mcu#john walker#us agent#isaiah bradley#truth red white and black#philippines#the punisher#gundam iron-blooded orphans#breaking bad#game of thrones#karli morgenthau#flag smashers#power broker#contessa valentina allegra de fontaine#erik killmonger#black panther#captain america#marvel

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Press: Streaming, With Only a Little Trepidation

“I’ve never had more fun on a job before,” says the WandaVision lead who spoke with the Ted Lasso star about their shows, the Scarlett Johansson lawsuit, and what happens to the theatrical moviegoing experience now.

In Reunited, Awards Insider hosts a conversation between two Emmy nominees who have collaborated on a previous project. Here, we speak with WandaVision star Elizabeth Olsen and Ted Lasso co-creator and star Jason Sudeikis, who previously starred in the 2017 film Kodachrome.

VANITY FAIR: Elizabeth Olsen and Jason Sudeikis met for the first time just before filming their 2017 indie Kodachrome, but they already had at least one thing in common: a “big old crush” on Ed Harris, as Olsen describes it. “He did not disappoint at all,” adds Sudeikis. “He stuck up for us. He cared about us. He cared about the movie.”

A guide to Hollywood’s biggest races

Now, the two have much more in common, as first-time Emmy nominees. Olsen is nominated for lead actress for her work as Wanda Maximoff in WandaVision, a Disney+ limited series that explores grief and loss, through a superhero story wrapped in a parody of TV sitcoms. Sudeikis earned four Emmy nominations for Apple TV+’s darling Ted Lasso, which he cocreated, cowrote, and stars in as Ted, a cheery American football coach who attempts to coach an English Premier League soccer team.

In early August, Olsen and Sudeikis reunited over Zoom to chat with Vanity Fair about transitioning these characters to TV, their views on the new streaming empires, and what they think of the lawsuit Scarlett Johansson recently brought against Disney regarding the strategy to stream Black Widow simultaneously with its theatrical release.

Vanity Fair: It’s been quite a few years since you shot Kodachrome. What do you remember about where you were on your trajectories at that time?

Elizabeth Olsen: Of life? It was when I was at a down trajectory.

Jason Sudeikis: Personally or professionally? I feel like from the outside, it only seems like you operate in one direction [motions upward].

Olsen: From a personal standpoint. So, I was excited to get to do a small movie, an intimate job that had some levity. And that was really nice. And I have a big old crush on Ed Harris and I still do.

Sudeikis: Yeah. To know that the director was like, “hey, we’re thinking about Jason Sudeikis for this role” and then Ed Harris stayed on, It was like, “all right, pleasant surprise. Pleasant surprise.”

Your current projects, WandaVision and Ted Lasso, may seem very different but do have one thing in common: they both feature characters that originated elsewhere. Wanda is obviously from the Marvel films and Jason you played Ted Lasso in commercials. Why did you feel these characters would work on a TV series?

Olsen: I got really comfortable in the Marvel movies, taking up my piece of the story and my piece of, how does my little arc work in this much larger arc with 30 other characters? And so the idea of all the focus being on me and Paul [Bettany] totally freaked me out. And that it was on television felt weird because these characters are superheroes and maybe they should be seen on big screens and not televisions. But the entire DNA of the show was meant for television. It was written for television. The arc has to be told through television. And from an actor’s point of view, it was something I’d never done. I’ve never done sitcom acting, let alone go through the decades with it.

And I’ve never had more fun on a job before. We got to go to work and just feel like an idiot all the time. And all of us, we’d be like hamming, hamming, hamming, and use each other as these barometers of “are we doing this too much? Is this now just a parody? Is this a joke? At what point are we supposed to dial it back?” And at one point I did, I think, a quadruple take, and that was the first time the director asked me to pull it back and just do a double take. So it was pretty incredible to get to expand on the character and this world, but do it from a totally different perspective. I’m so grateful for that job.

Sudeikis: Have you hosted SNL yet?

Olsen: God no!

Sudeikis: No? Well, I’m not going to agent you and be like, “if they ask, would you ever want to?” But, look, I know you’re funny. It was really fun to watch you do multi-cam sitcom acting. And then the genre thing, it made me be like, “oh, she would crush on SNL”. You’re always going to internalize stuff because you’re, in my opinion, very, very talented and very, very smart. So then even when you externalize things, like a quadruple take, it would be joyful to watch even in the attempt. Watching the show, it didn’t seem at all like an aberration or like you were putting it on. It felt well conceived and well thought out. And it almost made me wonder if the creator was aware of that or was it all just an act of faith on their part.

Olsen: It was a total act of faith. What they did is they took comedy actors who are really funny and gave them the more dramatic stuff. Because they thought that would balance out when we failed. And we’re like, “You guys are very smart for doing this.”

Sudeikis: Now, are you putting that on them or was that articulated to you day one?

Olsen: We talked about it. We were so open about it. We’re like, “this is very clever that you guys put some of the funniest actors in MCU in these dramatic parts.” But SNL, I watch it every Saturday when it’s live. I’m obsessed with SNL and that’s why I would never! It’s like the ocean. I respect the ocean so much and that’s why I don’t need to go in it.

Sudeikis: I don’t know. I think we’ll see. This is going to be like Charles Foster Kane’s declaration of principles. “I would never host SNL.” And then, “And your host, Elizabeth Olsen.”

Olsen: So tell me about Lasso: small to big.

Sudeikis: Me and my buddies, Joe [Kelly] and Brendan [Hunt], did those commercials in 2013, 2014, and we then sat down to talk about it in 2015. And it was kind of like, “okay, is it another set of commercials? Is it a movie?” I knew what the character was and we all grew up with great sports films, by Ron Shelton and Rudy and Hoosiers and things like that. But then also liked Nora Ephron, you know? We wanted to make something that had a little bit of romance. And romance may not be sexual, it’s also a platonic version of romance. And the story just sort of spooled out of us in a way that garnered a pilot episode and then a well-beat-out outline for a season. Because we were kind of modeling it after the British Office where it’d be like six episodes, six episodes, and then maybe an hour and a half special, like a movie type thing. Not wanting to take up too much space and not knowing how long it would go. And so it only could be a TV show, was the way it felt.

And so then it went away for a while because that was in 2015. And then lo and behold, it comes back around when I met Bill Lawrence for this other project. That one didn’t work out, but he was like, “Do you have anything?” I said, “Well, we have this.” And I remember having a whole bunch of stuff in this office, more work than I think he realized. He’s like, “Oh yeah, this is definitely, this is a whole thing. Okay. Wow. You guys have really thought this through.”

Olsen: Did you have a [writers] room or did you already write most of it?

Sudeikis: No, we definitely had a room. It was like I knew the chords, I knew the structure of things. We had a great room of 11 people for the first season. With hiring people, we just had good fortune. I didn’t know it was interesting at the time, but asking people during the interview process who their mentors were, who were the people that encouraged them, who made you think you could do this for a living—you can learn a lot about a person by listening to them talk about their mentors, their heroes.

Olsen: With the jokes, I feel like they’re so quick, but they’re so specific to people who watch sports and who knows sports. Well, not all of them, but a lot of the jokes are. Do you have a list of ones that you want to get in there or are these coming up in the room? Because it gets me as a big sports person.

Sudeikis: It really depends on it. There’s some ideas that I’d had for years and years that are just from old notebooks that I used to carry around when I worked on SNL before you would type things into a phone. And storylines and themes and characters that have just been ruminating in my head based on other ideas for either movies or sketches that didn’t make it. And then a big part of the room is that we have this collective consciousness that isn’t all sports.

And then with specific soccer jokes, we do try to include jokes that we call “two percenters” that only football fans would like. Just as our little tip of the cap because we wouldn’t be here without that group of people digging our shit back in the commercial days.

Your shows were on Disney+ and Apple TV+. Did you have any concerns about them being on streaming services, which were relatively new at the time, and finding an audience?

Sudeikis: It’d probably be more so if it was like Goodyear TV+, if it was some brand that didn’t already rule the world of entertainment and technology.

Olsen: I did a version of that with Facebook. And I didn’t like that experience. I loved my show [Sorry for Your Loss] and I loved everyone that I worked with. But the Facebook relationship was frustrating because of the lack of television experience and how the platform is organized. When we went to season two, we had a meeting that our show called for Facebook to have with us, so that we can give them our notes about their platform and why we think it’s really hard to find our show on their platform and how it’s congested. So I was anxious going into Disney+. But I knew it was Disney. And I think I was more anxious with the Marvel characters being on television than I was about the Disney+ element.

Sudeikis: Golly, I didn’t even consider that. And you’re absolutely right, because Facebook would be closer to Apple. Truth is we didn’t have a choice. We pitched it to a bunch of different places. They were the only ones that would open the door and say, “yeah, come in out of the rain, you can hang out in here. You can do your little show in here.” And so, the trepidation was alleviated by the fact that there was nowhere else open to us.