#south korean literature

Text

There are books that describe really important topics but at the same time they are so uncomfortable for me to read. But not because of the topic itself (which would be actually better because that would mean that I have to face something new and grow) but because of the side things like vulgarity, eroticism and sexuality.

I have two particular books in mind: „Walking practice“ by Dolki Min and „Norwegian Wood“ by Haruki Murakami.

The first one talks about what it means to be human and nonbinary in the binary world and how the binary world works in the mind of a nonbinary spectator.

The second one is an amazing struggle with mental illness and how it is to function in a relationship with a person who struggles. It shows many feelings and problems but also what it means to live in a reality if it actually exists.

But both of them were explicitly (and sometimes extremly) sexual. Needlessly sexual for me.

There was too much intercourse in the „Norwegian Wood“ but while reading „Walking practice“ I felt actually repulsed by the erotic descriptions. Moreover I really felt like it didn’t bring anything to the narrative.

Vulgarity has to play a role to be used but for me it looked like really tasteless sprinkles on top of an important story (here I’m talking speciafically about „Walking practice“). Yes, I’m speaking from the perspective of the aroace person. That’s why even though the sex scenes bugged me a bit, I can accept that it’s a way of displaying deep affections in the „Norwegian Wood”.

Meanwhile the vulgar sexuality of „Walking practice“ made me really uncomfortable not in a I-m-growing-as-a-person uncomfortable but in a I-want-to-stop-reading-immidiately way. Which is sad because as I stated before I consider the story extremly important in the discussion about binary vs nonbinary culture.

#books#japan#japanese#japanese literature#literature#south korean literature#dolki min#walking practice#haruki murakami#norwegian wood#haruki murakami Norwegian wood#Dolki min walking practice#south korean books#south korea#Japanese books#nonbinary#mental illness#mental struggle#book review#critical review

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

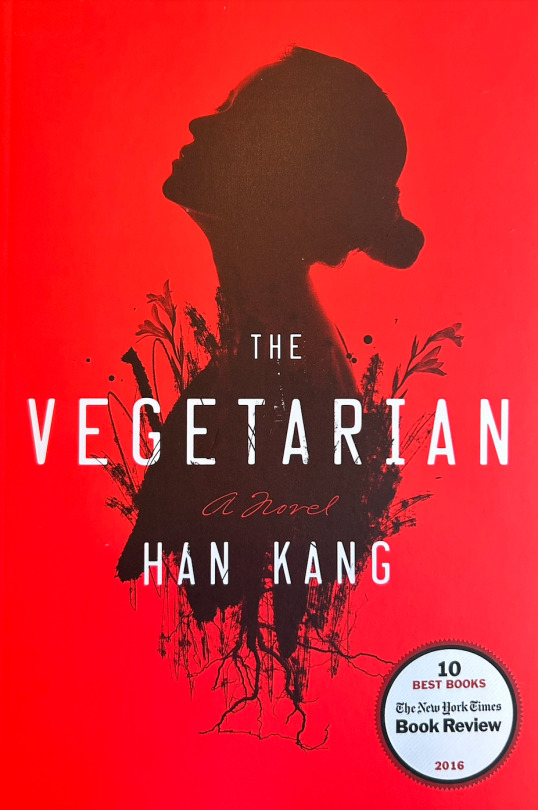

It has been far too long since I wrote one of these. I’ve gotten out of the habit. I’m also out of the habit of reading thoroughly in the way I long to, and best enjoy. It is thorough reading that lends itself to these reflective writing pieces, to tracking my thought process about a book. I have been in the habit of rushing through books for my book clubs during the busy school year. With the advent of summer break, I hope to return to that depth of reading and reflection. Let’s start with The Vegetarian.

I read this because I loved (and was disturb, challenged, and changed by) Human Acts. Han Kang has a new book out that I hope to read this summer as well. This book has much of the same dream-like thinking, gritty realism, complex psychology, and weighty symbolism that made Human Acts so compelling. Like Human Acts, the choices around narrative point of view (who tells their story and whose story gets told) feel deliberate, strategic, and powerful. This book felt a bit less mature as a novel than Human Acts, which makes sense given it’s an earlier work by Han Kang. I felt that the framework of metaphor and meaning was a bit harder to piece together here. There were more different loose threads and more questions remaining for the reader at the end of the book. I left the novel wanting just a bit more clarity, of the type that I had gotten from Human Acts.

That being stated, there was so much in this novel that was evocative and memorable, and which will stick with me—as imagery, as emotions, as concepts—over the years.

We begin with Yeong-hye’s dream. It’s the dream that moves her to stop eating meat early in the novel. The nature of this dream is revealed only in fragments, as Yeong-hye’s narrative point of view is never included (she is never given a voice, in her own story). In fragments scattered among her husband’s narration, we see parts of dreams (some of which, I later realized, draw on real memories from her childhood). This left me unsure of what Yeong-hye’s dream really was: the dog dragged in circles after her father’s motorcycle until death (later, it’s clear this is a memory)? A strange moment of cannibalism (bodies in a barn, teeth sinking into flesh)? A face in pain that repeatedly confronts her? The weight of all the dead things she has eaten settling over her heart, their bodies in her body? The dream that changes Yeong-hye could be all of these things, one of them, or none. The brutality in all these images is clear.

I deeply internalized this early explanation of Yeong-hye’s vegetarianism because it is—bizarrely, incredibly—exactly like my story. I became a vegetarian more than 13 years ago after a dream. I woke up the next day and I never ate meat again. Full stop. I have a different explanation I often give for my vegetarianism: that week, my town’s last small farm (one where my family had often volunteered our work efforts, and where we had befriended the generational farmer) went out of business. No longer able to survive as a small-scale, local operation in the face of climbing costs and competition from factory farms, the farmer went bankrupt. She needed to get rid of all her animals—about 200 sheep and 200 chickens, and 100 cattle—in 48 hours. My mom and I had helped with this, strategizing together, and my mom made phone calls to plead with people we knew to take some of these animals, so not every one would be sent to slaughter. This experience forms the backbone of my vegetarianism. Despite raising sheep and seeing other 4-H kids sending animals to slaughter, I understood that the real enemy was the factory farm operations in which animals were raised cruelly and unsustainably in order to drive down costs. I wanted to practice what I preached and one small way to do that was to not eat products I knew were coming out of the factory farming system.

This is the rational explanation I give about my conversion to vegetarianism. Even from myself, at times, I think I have hidden away the dream. The dream is what really changed me because—in the dream—I felt everything. I understood the horror of the factory farm on an emotional, not a rational, level. My dream feels hard to explain or share because words don’t adequately capture what it felt like, still so vivid in my memory all these years later. When the topic of my vegetarianism arises, I spend a lot of time not looking at my dream directly. In my dream, I was in a warm, dark space. There was the breathing of hundreds of other animals all around me. I could feel their presences and their bodies pressing in around me. I’m not sure what form my own body took, but I perceived the dream from the eye-level of the other animals. Among them, I felt a kind of individual invisibility, a kind of blended “togetherness.” But then, I suddenly understood what was coming. I saw with crystalline horror the future just in front of us, as we were being funneled out of this dark enclosure and slaughtered. Sliced at our soft throats, second jaws gapping, dangling. I could smell the blood. I could feel the deep terror in my body, like a cramping pain inside me. The certainty of death washed over me, and the need to stand in that certainty, to just anticipate it. I woke up, shocked awake.

The impossibility of adequately explaining how this dream felt to me, and how I woke up changed from it, makes the early fragmentation of The Vegetarian accessible to me. What is it to try to articulate the dream that redirected an essential thing? It’s better for us, the readers, to stay guessing a bit about what, exactly, is the dream. Anything less than this would feel cheap.

Yet, this novel, it quickly becomes clear, is not really about vegetarianism. Unlike Yeong-hye, my conversion to vegetarianism went that far and no farther. Yes, I know the people in my life responded much better than Yeong-hye’s did (in fact, all my immediate family members subsequently became vegetarians), but Yeong-hye enacts a complete disengagement with the exploitative world humans inhabit and normalize on a daily basis. What is this book really about? It’s about control, and gender. It’s about obsession, and art, and self-awareness. It’s about power, and nature, and what makes a life worth living (or ending).

The three narrators—Yeong-hye��s husband Mr. Cheong, Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law, and Yeong-hye’s sister In-hye—play out different responses, different levels of understanding, and different personal battles in the face of Yeong-hye’s increasing mental, emotional, and physical deterioration. While a key theme across the Han Kang books I’ve read is the problematic nature and impacts of the patriarchy (the violence, both physical and psychological, that men are permitted to enact on women), I felt a surprising amount of sympathy of a key male figure in this text: Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law. While Yeong-hye’s husband’s narration is repulsive in its dismissiveness of Yeong-hye’s inner life and personal experiences, and Yeong-hye’s father is revealed to be a key abuser in her childhood, Yeong-hye’s dynamic with her brother-in-law—while problematic—felt more mutually painful to me as a reader. I mention this because the brother-in-law’s narration feels like an area in the book of incredible nuance worthy of discussion. While it would be difficult to disagree about the problematic and outright morally wrong role of Yeong-hye’s husband and father, the role her brother-in-law plays is more complex. In-hye’s horror at discovering her husband and sister’s affair seems fully justified. She seems right to perceive her husband as taking advantage of her sister as her sister descends into madness. However, the brother-in-law seems to exhibit some striking similarities to Yeong-hye in a way that unites and binds them together. His obsession with the image of her Mongolian mark, and the flowers blooming on her, feels reminiscent of her obsession with the face from her dreams. An obsessive image is destroying him (his destruction includes that of his family, his role in his family, and his societal obligations). Distraught with obsession, both characters have something they want to get from the other, something they believe can be achieved by their union: relief. Viewed in this light, the brother-in-law seems as powerless in their affair as Yeong-hye does. Both are desperate, helpless, and mentally overwhelmed to the point of making choices they would not have made under normal circumstances. This feels like interesting commentary on human psychology, on the lengths we are willing to go to alleviate mental suffering, to distract or regain control of our own minds.

During this section of the novel, I wondered whether this brand of “vegetarianism” (obsession with plants, becoming plant-like oneself) could spreading from Yeong-hye to her brother-in-law. I tried to remember (and later Googled) the kind of fungus that inhabits and controls the human brain (turns out, this is only in Science Fiction…) This infectious plant theory feels like a too-literal explanation for a more figurative arc of the novel: what does it mean to consume or be consumed? What are all the different ramifications of consumption, of eating? In the third part of the novel, there is a similar expansion of Yeong-hye’s mental state to include and impact the person closest to her. In-hye’s does not understand her sister’s condition immediately or easily. She struggles to relate to her sister when she, herself, puts “making it work” and “holding things together” above all things in her life. But she comes to understand as she visits her dying sister in the mental hospitality and witnesses the cruelty of stripping Yeong-hye of her agency, of trying to force her back into life by maintaining her body, when it’s her will to live that is being squashed. As In-hye watches doctors force-fed her sister who refuses to eat, she sees the shadows of their past in which she choose stability over freedom (she chose to return herself and her sister to their abusive father, rather than run). She finally truly sees her sister’s transformation, and longing to change states and forms, the way she is “armored by the power of her own renunciation” of meat and, in this armor—like thick skin, like bark—Yeong-hye becomes incredibly plant-like (and increasingly free from her own mind/subjected to the consumption of others). The proximity of nature, the closeness of tree and woman, returns throughout this novel. Yeong-hye insists she does not need to eat, as she—like a tree—feeds from the sunlight. Her choice to not eat meat eventually becomes a choice to not eat at all, or to not eat in the way we humans understand eating…which involves consumption and eradication, rather than transformation.

There are several central images that, as I’ve mentioned, will remain with me. The death of the dog, both memory and dream, is one of these, as Han Kang is excellent at creating literal imagery with powerful metaphorical and philosophical resonance. This brutal scene immediately called to mind Achilles dragging Hector’s body around the walls of Troy, the public viciousness enacted by the victor, the visibility of brutality that is part of the process of control. It is not the same as violence conducted in secret. It is both more honest and more deeply performative. The second wave of metaphorical echo that flowed over me reading this scene was the Stations of the Cross, as Jesus carries the cross to his death and falls the first time, and falls the second time. This echo across the literary ages also highlights the brutality of humans (the acts of violence of which we are capable), but also the longing for redemption which is as fundamentally human as violence. Yeong-hye ate the dog meat. And, years later, her body seeks redemption, a kind of spiritual transformation, to purge that act of violence from the place in which it is held and remembered: the body. The physicality of Han Kang’s writing is as directly confrontational as I could imagine, and she pairs this physicality with deep moral complexity and nuance, so we are left seeking the meaning of these images that we—like Yeong-hye herself—cannot expunge from our minds.

#The Vegetarian#Han Kang#Human Acts#Vegetarianism#tw: descriptions of animal death#important reading#critiques of the patriarchy#South Korean Literature

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

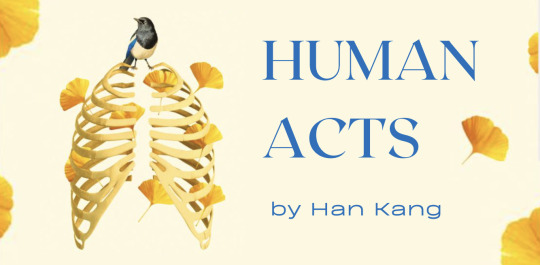

A Reminder That We Are Human: ‘Human Acts’ by Han Kang Review

by Isobelle Cruz [May 21, 2023]

I’ve been hesitant to open up my laptop lately, afraid that I had lost it in me to write a really good article, not in terms of how many likes I receive, but on how much I enjoy the process of making it. My recent works, I admit, have felt passionless and forced for the sake of keeping my blog alive. But this is different. I devoured “Human Acts” by Han Kang over the course of one weekend—my eyes rarely drifting from its pages.

I’d never encountered an interest in the author’s works before, but once I stepped foot in the bookstore, I was suddenly drawn to its cover; simple and clean, silencing the world that surrounded me into muffled echoes.

“Gwangju Uprising” scene in Saedeuldo Sesangeul Teuneunguna at the Yeongwoo Theatre, 1988 [Image Source: Yeongwoo Mudae]

Her lips move, but no sound comes out. Yet Eun-sook knows exactly what she is saying. She recognizes the lines from the manuscript, where Mr. Seo had written them in with a pen. The manuscripts she’s typed up herself, and proofread three times.

Page 101 of Human Acts

The book features the perspectives of seven characters, one of them being an editor in 1985. Eun-sook’s chapter shows her struggle against censorship and how the company overcomes this, still able to deliver the crossed-out lines of the censors through chilling imagery. Han Kang’s writing is delivered almost in the same feels as the play tackled in her book; quiet, slow, but enough to tell the story.

Gym turned mortuary in May 1980. [Image Source: Robin Moyer, Korea JoongAng Daily]

Another perspective that drew my attention closer than the others was of The Boy’s Friend, Jeong-dae. The words of the dead were briefly featured in the book; faceless spirits hovering over their bodies and watching as others live on, unable to do anything but watch.

If I could escape the sight of our bodies, that festering flesh now fused into a single mass, like rotting carcass of some many-legged monster. If I could sleep, truly sleep, not this flickering haze of wakefulness. If I could plunge headlong down to the floor of my pitch-dark consciousness.

Page 56 of “Human Acts”

It was depressing, and made me conscious of the body I still have control over—a blessing that I often take for granted.

Students on the streets of Gwangju, 1980 [Image Source: Lee Chang-seong, May 18 Memorial Foundation]

Is it possible to bear witness to the fact that of a foot-long wooden ruler being repeatedly thrust into my vagina, all the way to the back wall of my uterus? To a rifle butt bludgeoning my cervix? To the fact that, when the bleeding wouldn’t stop and I had gone into shock, they had to take me to the hospital for a blood transfusion?

Page 164 of Human Acts

Human Acts is flinchingly explicit and gory. It tells the stories of victims from different angles, some of which I would forget to consider if I had not opened this book.

It disturbs me to display these photos on here, but I believe that if words are not enough to deliver chills to the blinded eyes of people, photographs will.

The kids in the photo aren’t lying side by side because their corpses were lined up like that after they were killed. It’s because they were walking in a line.

Page 133 of Human Acts

Whether you read this in the rain, or at the beach where life is supposed to be happy, a strike of pain will stay in the back of your chest, the images of agony haunting you even in bed.

Human Acts truly opened my mind much more than the other books I’ve read that spit out facts and statistics, so much so, that I am driven away from what matters most—feeling and sympathizing with the victims. Most books I’ve encountered focus solely on hating the dictator that I finish them feeling sort of empty, that I am the same person as I was when I started the book. But that is not the case with Han Kang’s third novel. It reminded me that I am human, and how much my life should be valued.

#han kang#human acts#south korean literature#korean history#asian literature#asian author#asian history#martial law#chun doo hwan#gwangju massacre#gwangju uprising#May 18

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m waiting. No one is going to come, but still I wait. No one even knows I’m here, but I’m waiting all the same.

Han Kang, Human Acts, tr. Deborah Smith

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘔𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘐’𝘮 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘢𝘨𝘢𝘪𝘯 🍊

Dear, M.

#busan south korea#vogue korea#south korea#korean#Korea#South Korea aesthetic#travel#Asia#travel aesthetic#South Korea travel#academia#chaotic academia#classic academia#dark academia#literature#aesthetic#english literature#uni#college#her#i miss them#I miss her#persimmon#Busan#Seoul#Daegu#kimchi#sunset#korean bbq#dear m.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

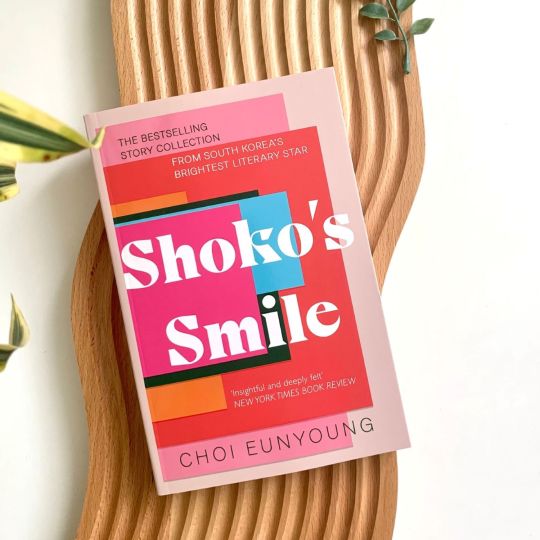

Time passes, people leave, we become alone again. If we don't accept that fact, memory erodes the present and exhausts the mind until it ages us and ails us.

- Choi Eunyoung, Shoko's Smile

#book quotes#books#life#life quotes#tumblr milestone#book tumblr#tbr#literature#positivity#korean literature#korean novel#south korean#shoko's smile#choi eunyoung#contemporary

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoko's Smile by Choi Eunyoung - Review

rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5)

”I was watching someone who'd had a piece of her mind shattered and found myself basking in an odd sense, of superiority.”

Shoko’s Smile is a short story collection about the lives of women in South Korea. The collection shows the hardships of what is expected of you as a woman single or married, the hard relationships that sometimes exist within family and even if you, as a woman, should speak about crimes the government has committed or if it would be better (and safer) to keep quiet.

It also explores the concept of having friends across different cultures, and how that can be challenging, especially if your countries do not have an amicable past with each other. Those differences can break or make a relationship.

I really enjoyed reading different perspectives of how one’s culture can be damaging in people’s upbringing and how it can shape their way of thinking.

”Despite my two feet resting on such uncertainty, (…) I had deluded myself into could plan my future.”

One thing shoko’s smile does perfectly is showing a real depiction of a lost and confused person in their twenties. As you read, the characters go through different struggles as they themselves navigate and discover their potential in a nation that is so unequal and that offers little opportunities. All of this while trying to make your family proud by doing what is expected of you as a korean woman.

”I was given constant warnings that women in particular needed to be careful about how they were perceived, that their future as a researcher was doomed once people started disparaging them behind their back.”

To get the full potential of this book and comprehend it you need to know Korea’s history and culture. These stories go in detail about some incidents that affected the lives of South Korean people. The last two stories are about the ferry incident in 2014 where more than 300 people lost their lives, most of them being high school students, and they’re two of the most heartbreaking stories i’ve ever read.

conclusion: This book is beautifully written and each story is deeply touching, you feel connected to each one. A great debut and i can't wait to read Choi Eunyoung's next work.

#my reviews#book review#booklr#book quotes#books#reviews#shoko's smile#choi eunyoung#korean literature#south korea#reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“When criticizing others, one assumes that one’s own level of refinement is the standard. No matter how lustrous a tradition something might have, when compared to one’s own standards all manner of highbrow criticisms become possible. On the other hand, this is the kind of freedom that an individual can enjoy.”

Endless Blue Sky — Lee Hyoseok.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the late 1990s, the dispute over the hoju system (the traditional family registration scheme, in which all members of a family must be registered under the patriarch) began in earnest with the emergence of organizations arguing for its abolition. Some people publicly used both of their parents’ surnames, and a few celebrities revealed their painful childhood memories of being picked on for having a different family name to their fathers. At the time, a very popular TV show about a single mother at risk of losing custody of her child, whom she’d been raising all on her own, to a deadbeat dad taught Jiyoung about the absurdity of the hoju system. But there were still those who thought its abolition would turn blood relations into strangers and make Korean society savage.

The hoju system was finally abolished in January 2008 and replaced with a new law. This was possible after the Constitutional Court found hoju incompatible with the constitution’s gender equality clause in February 2005.

Today, there is no such thing as “family registry,” and people are living their lives with the new individual identification system. It’s not compulsory for a newborn to take the patriarch’s last name anymore, and a couple has the option to decide—upon signing their marriage registration— to give the mother’s surname and family origin to their children.

Technically, it is possible, but there have been only 200 cases in which children took their mother’s name since the abolition of the hoju system in 2008.

“Most people still take their father’s last name. People will think that there’s some story behind the kid if they have their mother’s last name. There will be a lot of explaining and correcting and confirming to do if the child takes the mother’s last name,” Jiyoung said and Daehyun nodded. Jiyoung did not feel good as she checked “NO” with her own hand. The world had changed a great deal, but the little rules, contracts, and customs had not, which meant the world hadn’t actually changed at all. She mulled over Daehyun’s idea that registering as legally married changes the way you feel about each other. Do laws and institutions change values, or do values drive laws and institutions?

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam Joo

#kim jiyoung born 1982#apollo quotes#cho nam joo#literature#reading recs#feminist quotes#book quotes#books#booklr#feminist literature#feminism#south korea#quotes#study blog#reading#studyblr#academia#hoju system#korean academia

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanfic kpop pro projeto ❤

Uma chuva não é tão ruim agora"

– Aonde Jay e Won se presenteiam no dia dos namorados

• Postada no Wattpad no perfil do @candylandproject

• Não quero e nem queria ofender nenhum dos membros do grupo, é apenas um conteúdo de fã para fã.

• Curtam, compartilhem e comentem, é minha primeira obra para o projeto 🤧

Capa feita por: @lipoesw

Estória de minha autoria, não permito a repostagem sem qualquer consentimento meu

!! Para entrar em contato comigo me chame pelo:

Pv: Instagram

E-mail: [email protected]

wattpad ou spirit: @hangstkitty

Estarei sempre olhando !!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

East Asian literature/movies/shows I've been currently enjoying:

The housekeeper and the professor (or my preferred title: Professor's beloved equation) by Yöko Ogawa – Japanese slice of life (find my short review here)

My neighbor Totoro by Studio Ghibli

Revenge: Eleven dark tales by Yöko Ogawa – slice of life-ish horror, truly grew on me

First Love: Hatsukoi – slice of life Japanese romance (find my analysis here), best thing I’ve ever watched

Little Forest – Korean slice of life movie, lots of food shots

Something in the rain – Korean slice of life romance

If cats disappeared from the world by Genki Kawamura – Japanese slice of life meets Goethe's Faust (but executes the trope better)

The guest cat by Takashi Hiraide – the most slice of life book I've read, very meditative

When the weather is fine – korean slice of life romance (find my posts about it here and here)

The Memory Police by Yöko Ogawa – dystopian fiction (if you enjoyed Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury you'll love that too)

I will be your bloom – Japanese... I don't even know how to describe the genre, it was wild, weird and wonderful, but won’t be everyone’s cup of tea

Sweet bean paste by Durian Sukegawa – Japanese slice of life, excellent in every detail

Your eyes tell – Japanese drama/romance – it wrecked me thank you very much, can't recommend it enough

Please look after my mom by Kyung-sook Shin – Korean drama, very emotional

Norwegian wood by Haruki Murakami – Japanese romance, psychological drama, but I wouldn’t call it a favorite

Crash course in romance – Korean rom com, quite enjoyable and fun to watch, really adorable and funny

Nowhere to be found by Bae Suah – a parabolic slice of life short story

Walking Practice by Dolki Min – a horror existential story about being human, not for everyone (tbh not really for me, but I was the editor of the translated version in my country)

Summer strike – aesthetic, calming and full of kdrama (fits the canon 100%), if it wasn’t for the murder case it would be perfect

Turn to me, Mukai-kun – honestly it felt like 90% of the characters on that show were either aro, ace or both and I’m so here for it

The setting sun by Osamu Dazai – a classic when it comes to today’s Japanese literature, I see the value of the story, but didn’t love it as I thought I would

Diary of a Void by Emi Yagi – weird, creepy at times, both comforting and confusing, gave me the same kind of chills as Revenge by Yōko Ogawa

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata – an amazing short story about intolerance, surface level relationships and the incredible mechanism where men feel entitled to use women both when they conform to social expectations and when they decide to live against them

Doctor slump – heartwarming and emotional, I laughed, I cried, despite being a romance it had a great plot line about mental illnesses

Welcome to Samdal-ri – for everyone who feels overwhelmed by the world and needs a place to return to, very emotional, I cried like a baby more than once, would watch three more seasons of it

#Japanese#japanese literature#japanese movie#Japanese show#Japanese movies#Japanese tv shows#Japanese shows#Korean#South Korean#South Korean books#South Korean literature#korean literature#korean show#korean series#Korean drama#Japanese drama#Japan#South Korea#first love hatsukoi#crash course in romance#something in the rain#aromantic asexual#aroace#convenience store woman#the setting sun#osamu dazai#yōko ogawa#summer strike

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Han Kang does it again! And I am obliterated every single time.

Of the Han Kang novels I’ve read, this one felt the most hopeful, and also the most personally relevant to me. I think this is because the focus is literary and linguistic: the painful power of words, the impossibility of creating them, the tension between witnessing the world and embodying a self—these central themes are questions and confusions I have also confronted throughout my life. Both characters, therefore, felt relatable in a way that is not the norm for my encounters with Han Kang characters. That being said, both characters are pushed to their emotional extremes through situations I can’t relate to: growing blindness and silence. Yet, the questions that come from these experiences felt familiar (and perhaps there are things in my life and my nature that have led me to a similar set of questions).

As is always the case, I barely know where to start with writing about a Han Kang novel, as the individual threads of the book, and even individual words and phrases, are so powerful and charged as to send my thinking and feelings off into so many different directions. I’m glad, at least, to be writing this sitting at a table in a sunlight-infused cabin, by myself, with a beautiful view of saturated green trees in Bancroft, Ontario. This was a great book to read on my self-designated “writer’s retreat,” as it is so deeply introspective and so centering in the types of concerns I share as a writer and human being.

Early on in my reading, I quickly began a kind of meta-analysis, tracking symbols and relevance to the process of literary creation. Yet, this is something that Han Kang cautions us against, I believe. In the very beginning of the novel, the Greek lecturer describes the symbol of the sword that Borges requested on death’s door be used as his epitaph, and which was taken by critics to be a symbolic key to unpacking Borges’s writing. Yet, the Greek lecturer feels this request to be far more personal, not a key to one’s career and creation, but a key to one’s self: it’s the sword that calves the world from self. Is Han Kang cautioning us in this moment against the appeal of symbolic analysis? Reminding us that sometimes symbols are not charged with literary power, but personal resonance? Sometimes objects just are; they are not symbols at all… We make symbols of our own objects and memories, like we make narratives to understand and articulate ourselves…and that can be dangerous. My instinct to search for and read for symbols is so deep, just as it is to make them of my own life, that I know I cannot resist this process in my reading of this novel. However, I did want to state that I recognize this as an approach, and not, inherently, the right or best one through which to read books and to read one’s own life. I think Han Kang might struggle with a similar tension…how are we both embracing this understanding of language (isn’t language inherently symbolic?) and rejecting it? Like our silent protagonist student, the terror of words quickly overwhelms as we start to confront the inherent contradictions in speaking or writing at all…

This caveat being given (weak, weak), I jump into my analysis. Does the original impulse of this novel come out of writer’s block for the author? It’s terrifying to reach inside and find no words. It’s terrifying to spit out words, to force them out. It’s terrifying to look at each word and find it to be so deeply insufficient for the complex concept/emotion it is supposed incapsulate. It’s terrifying to try honestly and still be misunderstood. It’s terrifying to realize the harmful power of words, where even a small mistake can cause devastation…and what would happens if you tried to harness that harm into language? Irreversible. What is the response but to retreat into silence?

Yet, in the face of this crisis of language, there is true fascination with language and words. The descriptions of tenses in Greek unlock layers of articulation, the parting of roads under sheets of ice. The way Greek’s “middle voice” operates, referring to the self, reflexive, inspires a meditation on impact and change. Just so, the concepts in words become the concepts in our selves, or the reverse. To change something is to change the self, the Greek lecturer reflects, and he applies this to love/foolishness (recalling his first love that went south when he spoke a question he should not have asked). Love/foolishness: two sides of the same coin in which his foolishness destroys love and love destroys his foolishness (himself). The student (neither protagonist is ever given a name—perhaps names are too personal, too specific and insufficient) feels a similar fascination with the structure and nature of language, as it was a singular new word, bibliothèque, that drew her out of her silence as a teenager, that gave her words again. She pays attention to grammar, to language itself, to the act of translation. Both the Greek lecturer and the student have this in common, although the Greek lecturer longs more for literature, for narrative, for world (as it fades from his eyes, as it is relegated to dreams and memories). The student exists in a more immediate and practical sphere, experiencing the necessity of language itself.

This difference in desire is reflected in the narrative structures of the interwoven stories of both protagonists. The Greek lecturer’s sections take a direct “you” address to different figures in his life: his first love, his sister, his best friend in college. Each of these letters (missives, unsent) captures an array of memories and a portrait of deep love, which sustained and drove him. Each is also infused with tragedy and loss—the break-up with his first love after he asked her to speak, using the experiences she had at speech therapy as a young deaf child; the distance from his sister after he moved back to South Korea from Germany; the death of his college friend at age thirty-eight—and in unfolding each confessional, it is clear how much the Greek lecturer wants to say to each of these people. Some is shared, much is left unsaid. His is a different kind of silence.

The portrait of sibling-hood in the section addressed to the sister moved me deeply, both in its portrait of connection and in its individual lines: “it was in the company of your scowling, crying, laughing face that my childhood cracked, broke, was put back together unharmed, and so passed” (pg. 73). These siblings understand each other deeply, beyond language, having passed through their alienation in “togetherness.” This section—and the description of the shock of the father’s loss of eyesight, the Greek lecturer’s dread of his future—made me remember something I don’t think about often (I think I blocked it from my mind) that happened maybe seven or eight years ago. My younger sister had a disturbing eye doctor appointment and, for a brief time, we all thought she was going to go blind. During the two or three weeks until her follow-up, she wore dark sunglasses every time we went outside. I recall the devastation of this news—it was a kind of tragedy I would have never seen (ah) coming. I thought a lot at the time about how my sister was so fundamentally someone who saw the world; I thought about her life-long love of colors, visual art, drawing and painting, and her field work as a scientist in which she excelled at identifying plants, particularly grasses with nuances in green that no one else could see. She lived with, honed, and internalized an advanced ability to see and transmute her seeing—through details, lines, colors, and shapes—into both art and science. Seeing was part of her identity. Who would she be without this? The happy ending of this story is my sister had only a fleeting condition and the first optometrist she visited was overly dire. Her eyes recovered fully. It feels impossible to imagine the inverse narrative, and yet I did for a brief window of time.

While the Greek lecturer’s story hinges on introspective accounts of memories, the story of the student is revealed to us in little practical bursts: she has recently lost her mother (to cancer) and her son (in a legal battle with her ex-husband). She experienced a similar silence as a teenager, so that when she cannot force out the next word as she lectures at the blackboard her first thought is, it’s happening again. Throughout the book—until the very end—she is silent, and her sections are written in third-person, as if experiencing her life externally. Her words that we do hear, that she says “from a deeper place than throat and tongue,” are italicized and few. When she begins to communicate with the Greek lecturer by writing on his palm, her words are focused on practicalities, caring for him and helping him. This practicality feels both part of her nature and a part of the minimalist relationship she has developed with words. Words are, for her, so deeply buried that she can’t speak even to say her child’s name. She can’t speak in order to stand up for her son when he tells her he’s going away for a year, as his father has planned. In this moment, the language she wishes to use on her ex-husband is violent, angry. Which thing, I wondered, between silence and fury is powerlessness? In silence, we cannot defend ourselves. In anger, the words take over us and, bursting into the world, cut in ways that are terrible and unforeseen and final. We’re at the mercy of words. I wondered whether her silence (a removal of language) was an attempt to buffer herself from feeling? If we cannot put voice to feelings, does silence destroy feelings, just as feelings destroy silence (another set of reflexive inverses, interlocked, and self-impacting)? She dreams, in horror, of a singular word that contains all language. This is not a promising possibility, but a kind of nuclear bomb of language, with the power for infinite destruction if unleashed. This is the thinking of someone who understands how powerful and central language inherently is to ourselves.

When her therapist attributes her silence to the recent losses in her life, the student says, “it’s more than that” about her silence, but throughout the novel the losses of her child and her mother seem so acute. Later, the memory of the violent words her husband said to her—labeling her as insane, a “crazy bitch,” and ill-fit to care for her child—are recalled. She doesn’t want to remember this and she doesn’t want to feel the emotions of that memory. She also recalls the violence with which she wanted to respond in that moment, and the words cutting her up inside before they ever had a chance to get out. This memory may be the heart of her silence, yet, it is, as she herself shared, so much more complex than any one moment: an all-encompassing realization of the terrible nature of language.

While the unfamiliar and awe-inspiring grammar and structure of the Greek language is what the student seeks as a cure to her silence, time is also given in this book to the content of the writings of Plato and the philosophy of Socrates. These two thinkers form a compelling backdrop for this book, and the Greek lecturer views them as key thinkers that he circles around and around, facing his impending darkness. The Greek lecturer demonstrates the nearly identical verbs in Greek: to suffer and to learn. In pointing out their visual and aural proximity, the Greek lecturer points out how Socrates brings these words together, asking us to see the similarities in their actions. This was one of many moments in the first part of this book that reminded me of BTS (thinking here of RM’s word play with live/love in Trivia: Love). This was the point at which I realized this wasn’t a new Han Kang book—just a new translation—and she actually wrote this back in 2011. So, I came to conclusion that I just see BTS in it (the organizing narrative/symbolism of my brain), although perhaps RM has read this book. I found it interesting to consider Socrates’s famous reframe and philosophical position, “I know nothing,” as the basis for this book…beginning from a state of “knowing nothing” is an approach that takes the teeth out of words and language, by positioning oneself as not an authority or cause, but as a recipient or effect. Yet, I think Plato was the more central philosopher for the Greek lecturer. His longing for the “Forms” of things, of Beauty, which can only be understood cognitively and not seen in this world seems like a poignant obsession for the thoughts of a man on the brink of blindness. And the Greek lecturer is, like my sister, a man so in love with sight, with seeing, with imagery, with the visuals of the world: his memory of the beauty of the Buddha’s Birthday night, when he sat underneath the strings of lanterns with his mother and sister, and which he tries to revisit years later, is his most formative early memory.

During the Buddha’s birthday scene, I reflected on my life-long impulse to write. I think I have encountered writing as a response to the kind of desperation brought on by the sublime that the Greek lecturer experiences in this scene. What are we to do with those transcendent moments that haunt and transform us? That seem beyond our ability to contain inside ourselves? That will drive us to insanity, we fear, if we just hold them inside. I’ve tried to write that feeling out of myself. I’ve tried to transmute that experience I had into words. I have treated my writing as alchemy. I have tried to state change the memory moment into language. I have tried to reach across the “separateness of persons” and will that memory moment into you, or at least summon up your parallel moment with identical feelings. There is a similar self-intrinsic need to speak for Plato who the novel describes once as “know[ing] this is a dangerous soliloquy, that he is, in fact, answering his own question, as do we who are reading” (pg. 85). Writing feels like trying get into some impossible space, to leap and hope you find the parachute on the way down. For the Greek lecturer, like for Plato, words remain the impulse, as what else can he use to search for answers in the face of gigantic questions? For the student, words are smothered by the questions, by the horror of the answers. Both understandings of language can coexist.

The student remembers a kaleidoscope she made in school as a child, and she uses this memory to explain the way the worlds appears to her—“fragmented, each piece distinct and separate” (pg. 91)—once she loses words. I began to treat the kaleidoscope as the symbolic key to this text, operating like the scholar of Borges who I mentioned above. Han Kang writes, “The shards of memories shift and form patterns. Without particular context, without overall perspective or meaning. They scatter; suddenly, decisively, they come together” (pg. 92). Yet, borrowing the Greek lecturer’s interpretation of Borges’s epitaph as deeply personal, I strove to see the kaleidoscope symbol operating on a personal level in addition to a literary one. As the Greek lecturer writes to his loved ones, and accumulates their memories by jumping around in space and time, the structure of the writing mirrors the fragmentation of a kaleidoscope, making a point of the structure of memories contained within a singular being. Yet, isn’t it the very self, too, that is in fractals? Fascinatingly, as the Greek lecturer and the student arrive at his home and he begins to tell her the stories of his life, her memories, too, start to interweave and intersperse, again like the fracturing effect of a kaleidoscope.

While the first half of the novel assembles the characters and their situations, like a reverse kaleidoscope effect of bringing the pieces together, it is the sprint to the finish—after the bird incident, when our two protagonists come together—that is so powerful. I had to read the second half of this novel in one sitting because the momentum builds, like two magnets drawn closer and closer together, invisibly and forcefully. As one being, our two protagonists navigate the world together, pairing an outpouring of words with close observation, pairing dream-like intensity with practical reality. In this scene, they remind me of a poem by Mary Szybist called The Cathars Etc.:

The Cathars Etc.

By Mary Szybist

loved the spirit most

so to remind them of the ways of the flesh,

those of the old god

took one hundred prisoners and cut off

each nose

each pair of lips

and scooped out each eye

until just one eye on one man was left

to lead them home.

People did that, I say to myself,

a human hand lopping at a man's nose

over and over with a dull blade

that could not then slice

the lips clean

but like an old can opener, pushed

into skin, sawed

the soft edges, working each lip

slowly off as

both men heavily, intimately

breathed.

My brave believer, in my private re-enactments,

you are one of them.

I pick up in the aftermath where you're being led

by rope

by the one with the one good eye.

I'm one of the women at the edge of the hill

watching you stagger magnificently,

unsteadily back.

All your faces are tender with holes

starting to darken and scab

and I don't understand how you could

believe in anything that much

that is not me.

The man with the eye pulls you

forward. You're in the square now.

The women are hysterical,

the men are making terrible sounds

from unclosable mouths.

And I don't know if I can do it, if I can touch

a lipless face that might

lean down, instinctively,

to try to kiss me.

White rays are falling through the clouds.

You are holding that imbecile rope.

You are waiting to be claimed.

What do I love more than this

image of myself?

There I am in the square walking toward you

calling you out by name.

Poetry is the right place to go during this unspooling of the novel, during this near-magical coming together of the protagonists into one strange, incredible, better being. The interspersing or memories and dreams becomes stranger…the student leaves, and the lecturer’s memories become dreams. She returns and the descriptions grow even more fragmented, like poetry in their structure— solitary words in a line down the page. Is this spaced-out writing mirroring what the lecturer’s eyesight has become—fragmented, seeking space for clarity—like the concept of writing in the dark that the novel describes, handwriting with cautious extra space, so that no lines overlap, so that each word can be understood? The logic of this novel, whether kaleidoscope or sword, linguistic or literary, is inherently deeply poetic, I feel.

The novel’s ending is stunning as the protagonists progress into a hopeful interwoven state, described like rising to the surface of a lake. And, on the final page, we resolve with a section labeled 0 and, for the first time, narration is included in the first person point of view of the student. Language seems to bubble up in her in this final moment, in a reclamation of herself, but the book ends and we are left to interpret, to reach our own conclusions, in silence. It’s a powerful ending that feels less literal than gestural and emotional. I think there is so much I could get out of this book from re-reading it, from reading it in reverse, from reading it out of order. It raises more questions than it supplies answers, but it does demonstrate a central enduring faith in human connection, which both relies on and rejects language in order to be born, to bloom.

#greek lessons#han kang#important reading#why we write#reflections on human connections and intimacy#the world and the self#powerful books#reading reflection#south korean literature

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

so much grief in han kang's human acts (trans. deborah smith) when she writes, “after you died I could not hold a funeral, and so my life became a funeral.”

#korean literature#translated literature#literature#quotes#book quote#han kang#korea#south korea#quoteoftheday#east asia#asian literature

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You are the one to decide. If you consider it to be no big deal, then it is no big deal.

If you don’t consider it to be important, then other people won’t either. and if you consider it as something serious, then others will think of it that way, too. that’s how everything work. what happened in the past, it’s not a big deal. you’re the one who decides that.

-Park Dong-Hoon

#my mister#iu#lee jieun#my mister kdrama#drama my mister#kdrama#korean drama#korean#korea#south korea#literature

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕸𝖔𝖔𝖉𝖇𝖔𝖆𝖗𝖉 𝖔𝖋 𝖒𝖞 𝖋𝖗𝖎𝖊𝖓𝖉 𝕳𝖆𝖓

Met him in Korea. The coolest guy

#academia#classic academia#aesthetic#chaotic academia#dark academia#literature#english literature#uni#college#moodboard aesthetic#moodboard#music#musician#boy moodboard#boy aesthetic#musician aesthetic#piano#guitar#talented#star#glasses#cat#Korean#south korea aesthetic#south korea travel#friend moodboard#my friends#cat lover#sleepy boy#sleepy

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

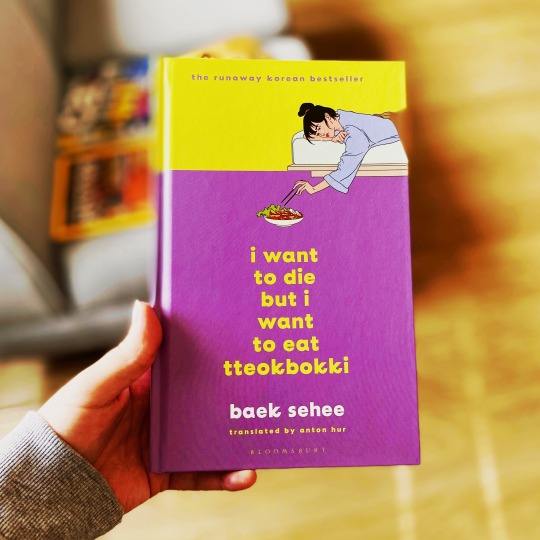

☀︎🌶.* I WANT TO DIE BUT I WANT TO EAT TTEOKBOKKI*.☀︎🌶

"

"THE PHENOMENAL KOREAN BESTSELLER

TRANSLATED BY INTERNATIONAL BOOKER SHORTLISTEE ANTON HUR

PSYCHIATRIST: So how can I help you?

ME: I don't know, I'm - what's the word - depressed? Do I have to go into detail?

Baek Sehee is a successful young social media director at a publishing house when she begins seeing a psychiatrist about her - what to call it? - depression? She feels persistently low, anxious, endlessly self-doubting, but also highly judgemental of others. She hides her feelings well at work and with friends; adept at performing the calmness, even ease, her lifestyle demands. The effort is exhausting, overwhelming, and keeps her from forming deep relationships. This can't be normal.

But if she's so hopeless, why can she always summon a desire for her favourite street food, the hot, spicy rice cake, tteokbokki? Is this just what life is like?

Recording her dialogues with her psychiatrist over a 12-week period, Baek begins to disentangle the feedback loops, knee-jerk reactions and harmful behaviours that keep her locked in a cycle of self-abuse. Part memoir, part self-help book, I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is a book to keep close and to reach for in times of darkness."

☀︎Check out my current read and help me to find my next read☀︎

#korean#amreading#books#bibliophile#book#bookstagram#book tumblr#bookish#reading#book aesthetic#booksbooksbooks#seoul#south korean#i want to die but i want to eat tteokbokki#baek sehee#anton hur#translated#literature#international#depression#self help#self care#healing#rap mon bts#rap monster#bts#bangtan#namjoon#taehyung#jin

5 notes

·

View notes