#greek lessons

Text

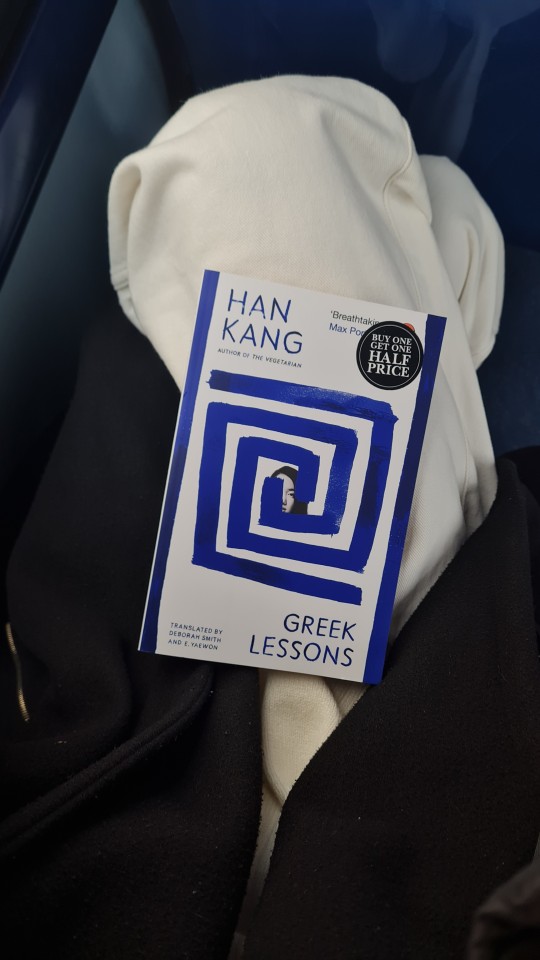

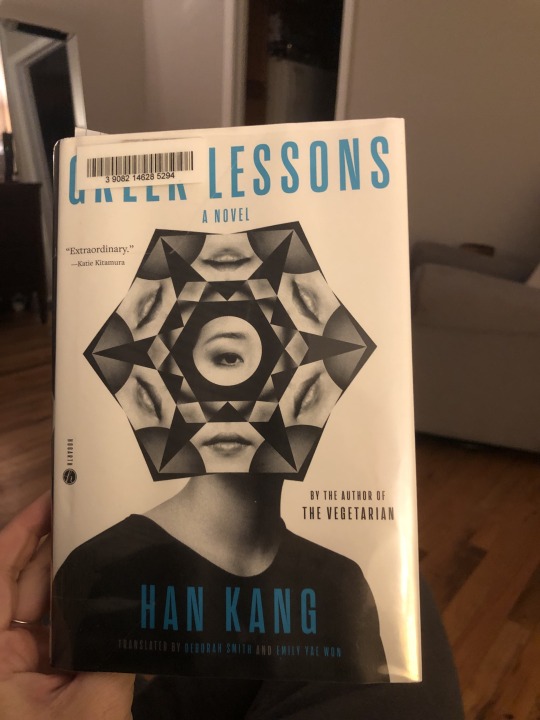

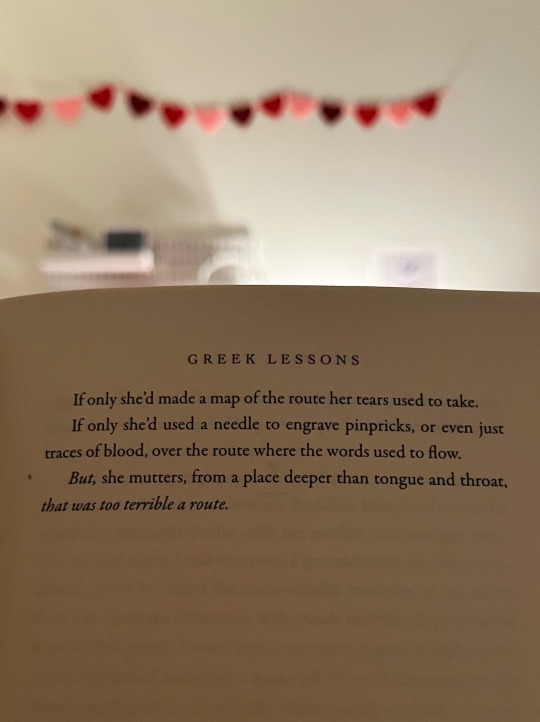

supposed to be on a book buying ban, but i just couldn't resist — 🤍

#photo diary#photo diaries#haul#book haul#greek lessons#han kang#literature aesthetics#books#book#bookish#bookblr#bookworm#bookstagram#dark academia#booklover#books and libraries#fitzcarraldo#study#study space#studyblr#study hard#studying#study motivation#study blog#study aesthetic#college student#lifestyle#retro#vintage#fit

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

A place in shadow, obscured and difficult to tread. A sentence in which Plato, no longer young, ponders and stalls for time. The indistinct voice of someone whose mouth is hidden behind their hand.

—Han Kang, Greek Lessons tr. Deborah Smith and Emily Yae Won

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

You said, This thing we call life mustn’t ever become something endured

Greek Lessons, Han Kang

#greek lessons#han kang#book suggestions#book#academia#chaotic academia#dark academia#currently reading#quotes

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently reading.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

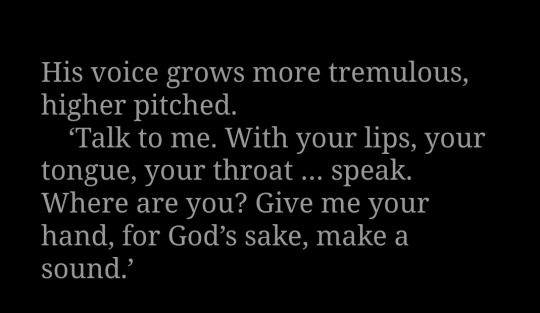

Han Kang, Greek Lessons tr. Deborah Smith & Emily Yae Won

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I saw in your language tag that for learning Modern Greek, you recommend the beginner/intermediate party on Duolingo. I was wondering if you had any opinions on the Kypros.org Greek course (http://www.kypros.org/LearnGreek/)?

Hi! I didn't know about it, I just checked it out. In short, I believe it can only help as a side way to improve your Greek but I wouldn't choose it as the main course.

It is old, apparently. I can tell by the way the speakers pronounce words and the music chosen that it is a course originally created sometime in the second half of the 20th century. Let alone the audio quality. I went straight ahead right to the middle, in an intermediate lesson and I believe they move a little bit too fast. The audio is fairly fast but at least there is a transcript of what's being said. There is also a forum with comments since 2021-2022, so you might be able to discuss topics with people.

In any case, I don't recommend it as the base of your studies. I believe Duolingo is still better for that. But this could be good as a side course to train your listening skills. It is free after all! And it reaches an advanced level which is also good.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

greek lessons, han kang

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Around the period her child—the child she had borne eight years ago and for whom she had now been deemed unfit to care—first learned to speak, she had dreamed of a single word in which all human language was encompassed. It was a nightmare so vivid as to leave her back drenched in sweat. One single word, bonded with a tremendous density and gravity. A language that would, the moment someone opened their mouth and pronounced it, explode and expand as all matter had at the universe’s beginning. Every time she put her tired, fretful child to bed and drifted into a light sleep herself, she would dream that the immense crystallized mass of all language was being primed like an ice-cold explosive in the center of her hot heart, encased in her pulsing ventricles.”

—Han Kang, Greek Lessons

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes she thinks of herself as more like some form of substance, a moving solid or liquid, than like a person. […] At the same time she knows that she is […] some harsh, solid substance that will never commingle with any being, living or otherwise.

—Han Kang, Greek Lessons tr. Deborah Smith and Emily Yae Won

#han kang#greek lessons#deborah smith#emily yae won#w#2023 reads#upl#i who am substance of shadow#loneliness

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

082623

fall is in the mf tree!!

today was such a big day for me bc the asbestos in my house got encapsulated!!

i just had a little bit in my attic. a learning experience!

roses of sharons:

worked today for my newest family

and was just reading this.....it is good but this author is not the easiest to read! or u rly have to take ur time and savor every word and decipher? idk

then i went to paramita to see something blue and sabetye and it was great!

i went alone and found syd who was w a group of friends and i was kind of just sitting near them alone at the bar hanging out i stayed basically til the end and as everyone was walking away i said bye to syd and her group lmao but why did one of the girls in the group was like "where are you going?" i was like to my car and to her friends she was like " i thought we were guarding her!!" hahahaha i was rly tickled by that but tbh they did a great job guarding me bc no man spoke to me or touched me all night!!!!!!! LOVE THAT!!!!!!!!

sadly had to cover this outfit w jacket bc of the cold! but one thing i love about paramita is going to the bathroom in the siren and passing by candy bar to see what is going on in there <3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Han Kang does it again! And I am obliterated every single time.

Of the Han Kang novels I’ve read, this one felt the most hopeful, and also the most personally relevant to me. I think this is because the focus is literary and linguistic: the painful power of words, the impossibility of creating them, the tension between witnessing the world and embodying a self—these central themes are questions and confusions I have also confronted throughout my life. Both characters, therefore, felt relatable in a way that is not the norm for my encounters with Han Kang characters. That being said, both characters are pushed to their emotional extremes through situations I can’t relate to: growing blindness and silence. Yet, the questions that come from these experiences felt familiar (and perhaps there are things in my life and my nature that have led me to a similar set of questions).

As is always the case, I barely know where to start with writing about a Han Kang novel, as the individual threads of the book, and even individual words and phrases, are so powerful and charged as to send my thinking and feelings off into so many different directions. I’m glad, at least, to be writing this sitting at a table in a sunlight-infused cabin, by myself, with a beautiful view of saturated green trees in Bancroft, Ontario. This was a great book to read on my self-designated “writer’s retreat,” as it is so deeply introspective and so centering in the types of concerns I share as a writer and human being.

Early on in my reading, I quickly began a kind of meta-analysis, tracking symbols and relevance to the process of literary creation. Yet, this is something that Han Kang cautions us against, I believe. In the very beginning of the novel, the Greek lecturer describes the symbol of the sword that Borges requested on death’s door be used as his epitaph, and which was taken by critics to be a symbolic key to unpacking Borges’s writing. Yet, the Greek lecturer feels this request to be far more personal, not a key to one’s career and creation, but a key to one’s self: it’s the sword that calves the world from self. Is Han Kang cautioning us in this moment against the appeal of symbolic analysis? Reminding us that sometimes symbols are not charged with literary power, but personal resonance? Sometimes objects just are; they are not symbols at all… We make symbols of our own objects and memories, like we make narratives to understand and articulate ourselves…and that can be dangerous. My instinct to search for and read for symbols is so deep, just as it is to make them of my own life, that I know I cannot resist this process in my reading of this novel. However, I did want to state that I recognize this as an approach, and not, inherently, the right or best one through which to read books and to read one’s own life. I think Han Kang might struggle with a similar tension…how are we both embracing this understanding of language (isn’t language inherently symbolic?) and rejecting it? Like our silent protagonist student, the terror of words quickly overwhelms as we start to confront the inherent contradictions in speaking or writing at all…

This caveat being given (weak, weak), I jump into my analysis. Does the original impulse of this novel come out of writer’s block for the author? It’s terrifying to reach inside and find no words. It’s terrifying to spit out words, to force them out. It’s terrifying to look at each word and find it to be so deeply insufficient for the complex concept/emotion it is supposed incapsulate. It’s terrifying to try honestly and still be misunderstood. It’s terrifying to realize the harmful power of words, where even a small mistake can cause devastation…and what would happens if you tried to harness that harm into language? Irreversible. What is the response but to retreat into silence?

Yet, in the face of this crisis of language, there is true fascination with language and words. The descriptions of tenses in Greek unlock layers of articulation, the parting of roads under sheets of ice. The way Greek’s “middle voice” operates, referring to the self, reflexive, inspires a meditation on impact and change. Just so, the concepts in words become the concepts in our selves, or the reverse. To change something is to change the self, the Greek lecturer reflects, and he applies this to love/foolishness (recalling his first love that went south when he spoke a question he should not have asked). Love/foolishness: two sides of the same coin in which his foolishness destroys love and love destroys his foolishness (himself). The student (neither protagonist is ever given a name—perhaps names are too personal, too specific and insufficient) feels a similar fascination with the structure and nature of language, as it was a singular new word, bibliothèque, that drew her out of her silence as a teenager, that gave her words again. She pays attention to grammar, to language itself, to the act of translation. Both the Greek lecturer and the student have this in common, although the Greek lecturer longs more for literature, for narrative, for world (as it fades from his eyes, as it is relegated to dreams and memories). The student exists in a more immediate and practical sphere, experiencing the necessity of language itself.

This difference in desire is reflected in the narrative structures of the interwoven stories of both protagonists. The Greek lecturer’s sections take a direct “you” address to different figures in his life: his first love, his sister, his best friend in college. Each of these letters (missives, unsent) captures an array of memories and a portrait of deep love, which sustained and drove him. Each is also infused with tragedy and loss—the break-up with his first love after he asked her to speak, using the experiences she had at speech therapy as a young deaf child; the distance from his sister after he moved back to South Korea from Germany; the death of his college friend at age thirty-eight—and in unfolding each confessional, it is clear how much the Greek lecturer wants to say to each of these people. Some is shared, much is left unsaid. His is a different kind of silence.

The portrait of sibling-hood in the section addressed to the sister moved me deeply, both in its portrait of connection and in its individual lines: “it was in the company of your scowling, crying, laughing face that my childhood cracked, broke, was put back together unharmed, and so passed” (pg. 73). These siblings understand each other deeply, beyond language, having passed through their alienation in “togetherness.” This section—and the description of the shock of the father’s loss of eyesight, the Greek lecturer’s dread of his future—made me remember something I don’t think about often (I think I blocked it from my mind) that happened maybe seven or eight years ago. My younger sister had a disturbing eye doctor appointment and, for a brief time, we all thought she was going to go blind. During the two or three weeks until her follow-up, she wore dark sunglasses every time we went outside. I recall the devastation of this news—it was a kind of tragedy I would have never seen (ah) coming. I thought a lot at the time about how my sister was so fundamentally someone who saw the world; I thought about her life-long love of colors, visual art, drawing and painting, and her field work as a scientist in which she excelled at identifying plants, particularly grasses with nuances in green that no one else could see. She lived with, honed, and internalized an advanced ability to see and transmute her seeing—through details, lines, colors, and shapes—into both art and science. Seeing was part of her identity. Who would she be without this? The happy ending of this story is my sister had only a fleeting condition and the first optometrist she visited was overly dire. Her eyes recovered fully. It feels impossible to imagine the inverse narrative, and yet I did for a brief window of time.

While the Greek lecturer’s story hinges on introspective accounts of memories, the story of the student is revealed to us in little practical bursts: she has recently lost her mother (to cancer) and her son (in a legal battle with her ex-husband). She experienced a similar silence as a teenager, so that when she cannot force out the next word as she lectures at the blackboard her first thought is, it’s happening again. Throughout the book—until the very end—she is silent, and her sections are written in third-person, as if experiencing her life externally. Her words that we do hear, that she says “from a deeper place than throat and tongue,” are italicized and few. When she begins to communicate with the Greek lecturer by writing on his palm, her words are focused on practicalities, caring for him and helping him. This practicality feels both part of her nature and a part of the minimalist relationship she has developed with words. Words are, for her, so deeply buried that she can’t speak even to say her child’s name. She can’t speak in order to stand up for her son when he tells her he’s going away for a year, as his father has planned. In this moment, the language she wishes to use on her ex-husband is violent, angry. Which thing, I wondered, between silence and fury is powerlessness? In silence, we cannot defend ourselves. In anger, the words take over us and, bursting into the world, cut in ways that are terrible and unforeseen and final. We’re at the mercy of words. I wondered whether her silence (a removal of language) was an attempt to buffer herself from feeling? If we cannot put voice to feelings, does silence destroy feelings, just as feelings destroy silence (another set of reflexive inverses, interlocked, and self-impacting)? She dreams, in horror, of a singular word that contains all language. This is not a promising possibility, but a kind of nuclear bomb of language, with the power for infinite destruction if unleashed. This is the thinking of someone who understands how powerful and central language inherently is to ourselves.

When her therapist attributes her silence to the recent losses in her life, the student says, “it’s more than that” about her silence, but throughout the novel the losses of her child and her mother seem so acute. Later, the memory of the violent words her husband said to her—labeling her as insane, a “crazy bitch,” and ill-fit to care for her child—are recalled. She doesn’t want to remember this and she doesn’t want to feel the emotions of that memory. She also recalls the violence with which she wanted to respond in that moment, and the words cutting her up inside before they ever had a chance to get out. This memory may be the heart of her silence, yet, it is, as she herself shared, so much more complex than any one moment: an all-encompassing realization of the terrible nature of language.

While the unfamiliar and awe-inspiring grammar and structure of the Greek language is what the student seeks as a cure to her silence, time is also given in this book to the content of the writings of Plato and the philosophy of Socrates. These two thinkers form a compelling backdrop for this book, and the Greek lecturer views them as key thinkers that he circles around and around, facing his impending darkness. The Greek lecturer demonstrates the nearly identical verbs in Greek: to suffer and to learn. In pointing out their visual and aural proximity, the Greek lecturer points out how Socrates brings these words together, asking us to see the similarities in their actions. This was one of many moments in the first part of this book that reminded me of BTS (thinking here of RM’s word play with live/love in Trivia: Love). This was the point at which I realized this wasn’t a new Han Kang book—just a new translation—and she actually wrote this back in 2011. So, I came to conclusion that I just see BTS in it (the organizing narrative/symbolism of my brain), although perhaps RM has read this book. I found it interesting to consider Socrates’s famous reframe and philosophical position, “I know nothing,” as the basis for this book…beginning from a state of “knowing nothing” is an approach that takes the teeth out of words and language, by positioning oneself as not an authority or cause, but as a recipient or effect. Yet, I think Plato was the more central philosopher for the Greek lecturer. His longing for the “Forms” of things, of Beauty, which can only be understood cognitively and not seen in this world seems like a poignant obsession for the thoughts of a man on the brink of blindness. And the Greek lecturer is, like my sister, a man so in love with sight, with seeing, with imagery, with the visuals of the world: his memory of the beauty of the Buddha’s Birthday night, when he sat underneath the strings of lanterns with his mother and sister, and which he tries to revisit years later, is his most formative early memory.

During the Buddha’s birthday scene, I reflected on my life-long impulse to write. I think I have encountered writing as a response to the kind of desperation brought on by the sublime that the Greek lecturer experiences in this scene. What are we to do with those transcendent moments that haunt and transform us? That seem beyond our ability to contain inside ourselves? That will drive us to insanity, we fear, if we just hold them inside. I’ve tried to write that feeling out of myself. I’ve tried to transmute that experience I had into words. I have treated my writing as alchemy. I have tried to state change the memory moment into language. I have tried to reach across the “separateness of persons” and will that memory moment into you, or at least summon up your parallel moment with identical feelings. There is a similar self-intrinsic need to speak for Plato who the novel describes once as “know[ing] this is a dangerous soliloquy, that he is, in fact, answering his own question, as do we who are reading” (pg. 85). Writing feels like trying get into some impossible space, to leap and hope you find the parachute on the way down. For the Greek lecturer, like for Plato, words remain the impulse, as what else can he use to search for answers in the face of gigantic questions? For the student, words are smothered by the questions, by the horror of the answers. Both understandings of language can coexist.

The student remembers a kaleidoscope she made in school as a child, and she uses this memory to explain the way the worlds appears to her—“fragmented, each piece distinct and separate” (pg. 91)—once she loses words. I began to treat the kaleidoscope as the symbolic key to this text, operating like the scholar of Borges who I mentioned above. Han Kang writes, “The shards of memories shift and form patterns. Without particular context, without overall perspective or meaning. They scatter; suddenly, decisively, they come together” (pg. 92). Yet, borrowing the Greek lecturer’s interpretation of Borges’s epitaph as deeply personal, I strove to see the kaleidoscope symbol operating on a personal level in addition to a literary one. As the Greek lecturer writes to his loved ones, and accumulates their memories by jumping around in space and time, the structure of the writing mirrors the fragmentation of a kaleidoscope, making a point of the structure of memories contained within a singular being. Yet, isn’t it the very self, too, that is in fractals? Fascinatingly, as the Greek lecturer and the student arrive at his home and he begins to tell her the stories of his life, her memories, too, start to interweave and intersperse, again like the fracturing effect of a kaleidoscope.

While the first half of the novel assembles the characters and their situations, like a reverse kaleidoscope effect of bringing the pieces together, it is the sprint to the finish—after the bird incident, when our two protagonists come together—that is so powerful. I had to read the second half of this novel in one sitting because the momentum builds, like two magnets drawn closer and closer together, invisibly and forcefully. As one being, our two protagonists navigate the world together, pairing an outpouring of words with close observation, pairing dream-like intensity with practical reality. In this scene, they remind me of a poem by Mary Szybist called The Cathars Etc.:

The Cathars Etc.

By Mary Szybist

loved the spirit most

so to remind them of the ways of the flesh,

those of the old god

took one hundred prisoners and cut off

each nose

each pair of lips

and scooped out each eye

until just one eye on one man was left

to lead them home.

People did that, I say to myself,

a human hand lopping at a man's nose

over and over with a dull blade

that could not then slice

the lips clean

but like an old can opener, pushed

into skin, sawed

the soft edges, working each lip

slowly off as

both men heavily, intimately

breathed.

My brave believer, in my private re-enactments,

you are one of them.

I pick up in the aftermath where you're being led

by rope

by the one with the one good eye.

I'm one of the women at the edge of the hill

watching you stagger magnificently,

unsteadily back.

All your faces are tender with holes

starting to darken and scab

and I don't understand how you could

believe in anything that much

that is not me.

The man with the eye pulls you

forward. You're in the square now.

The women are hysterical,

the men are making terrible sounds

from unclosable mouths.

And I don't know if I can do it, if I can touch

a lipless face that might

lean down, instinctively,

to try to kiss me.

White rays are falling through the clouds.

You are holding that imbecile rope.

You are waiting to be claimed.

What do I love more than this

image of myself?

There I am in the square walking toward you

calling you out by name.

Poetry is the right place to go during this unspooling of the novel, during this near-magical coming together of the protagonists into one strange, incredible, better being. The interspersing or memories and dreams becomes stranger…the student leaves, and the lecturer’s memories become dreams. She returns and the descriptions grow even more fragmented, like poetry in their structure— solitary words in a line down the page. Is this spaced-out writing mirroring what the lecturer’s eyesight has become—fragmented, seeking space for clarity—like the concept of writing in the dark that the novel describes, handwriting with cautious extra space, so that no lines overlap, so that each word can be understood? The logic of this novel, whether kaleidoscope or sword, linguistic or literary, is inherently deeply poetic, I feel.

The novel’s ending is stunning as the protagonists progress into a hopeful interwoven state, described like rising to the surface of a lake. And, on the final page, we resolve with a section labeled 0 and, for the first time, narration is included in the first person point of view of the student. Language seems to bubble up in her in this final moment, in a reclamation of herself, but the book ends and we are left to interpret, to reach our own conclusions, in silence. It’s a powerful ending that feels less literal than gestural and emotional. I think there is so much I could get out of this book from re-reading it, from reading it in reverse, from reading it out of order. It raises more questions than it supplies answers, but it does demonstrate a central enduring faith in human connection, which both relies on and rejects language in order to be born, to bloom.

#greek lessons#han kang#important reading#why we write#reflections on human connections and intimacy#the world and the self#powerful books#reading reflection#south korean literature

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"But she knew that if she followed that reasoning the rest of her life would be one long struggle to find a response to the question that constantly threatened to destroy her fragile equilibrium"

Han Kang, Greek Lessons

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read GREEK LESSONS by Han Kang if you love classrooms, dual narratives, loss, language, Plato's Republic, walking, being uncertain of your place in the world, silence, wearing black, words, tangerines, letters, dreams, communicating, kaleidoscopes, and memory.

(I received an advance copy of the book from the publisher, through NetGalley.

The expected publication date is 18 Apr 2023).

#book#books#bookreccs#book reccomendation#book review#book cover#Greek Lessons by Han Kang#Han Kang#Greek Lessons#bookish#bibliophile#read#reader#readers of tumblr#read more#Read this if...#readingismagic#I read books#bookworm#booknerd#advance copy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek Lessons by Han Kang

0 notes