Text

we should talk more about cities that are vampires. cities that are cold and wet and sink into your bones and stay there. cities that are hungry and want to live. dead cities that dont know they're dead and suck the life force of their people to maintain the delusion. cities with harbors that are actually mouths; one-way entries. cities that are devastatingly lonely and see consumption as love

45K notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephen Dunn, from “Mon Semblable”, Between Angels

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Endangered Indian sandalwood. British war to control the forests. Tallying every single tree in the kingdom. European companies claim the ecosystem. Spices and fragrances. Failure of the plantation. Until the twentieth century, the Empire couldn't figure out how to cultivate sandalwood because they didn't understand that the plant is actually a partial root parasite. French perfumes and the creation of "the Sandalwood City".

---

Selling at about $147,000 per metric ton, the aromatic heartwood of Indian sandalwood (S. album) is arguably [among] the most expensive wood in the world. Globally, 90 per cent of the world’s S. album comes from India [...]. And within India, around 70 per cent of S. album comes from the state of Karnataka [...] [and] the erstwhile Kingdom of Mysore. [...] [T]he species came to the brink of extinction. [...] [O]verexploitation led to the sandal tree's critical endangerment in 1974. [...]

---

Francis Buchanan’s 1807 A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar is one of the few European sources to offer insight into pre-colonial forest utilisation in the region. [...] Buchanan records [...] [the] tradition of only harvesting sandalwood once every dozen years may have been an effective local pre-colonial conservation measure. [...] Starting in 1786, Tipu Sultan [ruler of Mysore] stopped trading pepper, sandalwood and cardamom with the British. As a result, trade prospects for the company [East India Company] were looking so bleak that by November 1788, Lord Cornwallis suggested abandoning Tellicherry on the Malabar Coast and reducing Bombay’s status from a presidency to a factory. [...] One way to understand these wars is [...] [that] [t]hey were about economic conquest as much as any other kind of expansion, and sandalwood was one of Mysore’s most prized commodities. In 1799, at the Battle of Srirangapatna, Tipu Sultan was defeated. The kingdom of Mysore became a princely state within British India [...]. [T]he East India Company also immediately started paying the [new rulers] for the right to trade sandalwood.

British control over South Asia’s natural resources was reaching its peak and a sophisticated new imperial forest administration was being developed that sought to solidify state control of the sandalwood trade. In 1864, the extraction and disposal of sandalwood came under the jurisdiction of the Forest Department. [...] Colonial anxiety to maximise profits from sandalwood meant that a government agency was established specifically to oversee the sandalwood trade [...] and so began the government sandalwood depot or koti system. [...]

From the 1860s the [British] government briefly experimented with a survey tallying every sandal tree standing in Mysore [...].

Instead, an intricate system of classification was developed in an effort to maximise profits. By 1898, an 18-tiered sandalwood classification system was instituted, up from a 10-tier system a decade earlier; it seems this led to much confusion and was eventually reduced back to 12 tiers [...].

---

Meanwhile, private European companies also made significant inroads into Mysore territory at this time. By convincing the government to classify forests as ‘wastelands’, and arguing that Europeans would improves these tracts from their ‘semi-savage state’, starting in the 1860s vast areas were taken from local inhabitants and converted into private plantations for the ‘production of cardamom, pepper, coffee and sandalwood’.

---

Yet attempts to cultivate sandalwood on both forest department and privately owned plantations proved to be a dismal failure. There were [...] major problems facing sandalwood supply in the period before the twentieth century besides overexploitation and European monopoly. [...] Before the first quarter of the twentieth century European foresters simply could not figure out how to grow sandalwood trees effectively.

The main reason for this is that sandal is what is now known as a semi-parasite or root parasite; besides a main taproot that absorbs nutrients from the earth, the sandal tree grows parasitical roots (or haustoria) that derive sustenance from neighbouring brush and trees. [...] Dietrich Brandis, the man often regaled as the father of Indian forestry, reported being unaware of the [sole significant English-language scientific paper on sandalwood root parasitism] when he worked at Kew Gardens in London on South Asian ‘forest flora’ in 1872–73. Thus it was not until 1902 that the issue started to receive attention in the scientific community, when C.A. Barber, a government botanist in Madras [...] himself pointed out, 'no one seems to be at all sure whether the sandalwood is or is not a true parasite'.

Well into the early decades of twentieth century, silviculture of sandal proved a complete failure. The problem was the typical monoculture approach of tree farming in which all other species were removed and so the tree could not survive. [...]

The long wait time until maturity of the tree must also be considered. Only sandal heartwood and roots develop fragrance, and trees only begin developing fragrance in significant quantities after about thirty years. Not only did traders, who were typically just sailing through, not have the botanical know-how to replant the tree, but they almost certainly would not be there to see a return on their investments if they did. [...]

---

The main problem facing the sustainable harvest and continued survival of sandalwood in India [...] came from the advent of the sandalwood oil industry at the beginning of the twentieth century. During World War I, vast amounts of sandal were stockpiled in Mysore because perfumeries in France had stopped production and it had become illegal to export to German perfumeries. In 1915, a Government Sandalwood Oil Factory was built in Mysore. In 1917, it began distilling. [...] [S]andalwood production now ramped up immensely. It was at this time that Mysore came to be known as ‘the Sandalwood City’.

---

Text above by: Ezra Rashkow. "Perfumed the axe that laid it low: The endangerment of sandalwood in southern India." Indian Economic and Social History Review 51, no. 1, pages 41-70. March 2014. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Italicized first paragraph/heading in this post added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

205 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Three Gorgons and Sickness, Madness, and Death from the Beethoven Frieze - Gustav Klimt, 1902. Painted for the 14th Vienna Secessionist Exhibition, and now permanently located in the Vienna Secession Museum

21K notes

·

View notes

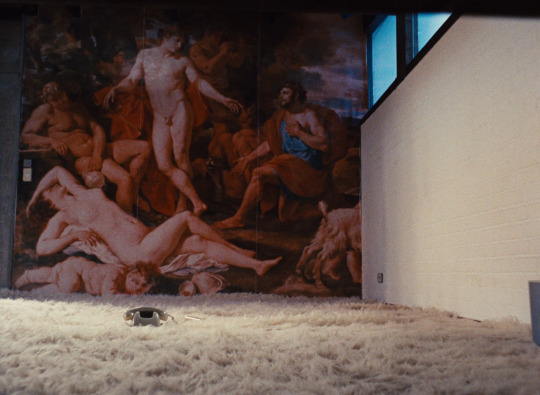

Photo

Fanny och Alexander - Ingmar Bergman - 1982 - Sweden/France/West Germany

174 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wall painting originally from the Temple of Isis in Pompeii,depicts a priest with a mask of Anubis.

Naples National Archaeological Museum

By: Amphipolis (CC BY-SA 2.0)

829 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s not that the past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on the past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation. In other words, image is dialectics at a standstill. For while the relation of the present to the past is a purely temporal, continuous one, the relation of what-has-been to the now is dialectical: is not progression but image, suddenly emergent. – Only dialectical images are genuine images…and the place where one encounters them is language.

—Walter Benjamin, ‘Awakening’, The Arcades Project tr. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin

#walter benjamin#the Arcades Project#Kevin McLaughlin#howard eiland#w#upl#not reading but found in an epigraph... v beautiful

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

lets give it up for pleasures of the flesh !!

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

Will St. John (American, b. 1980) “Hari in Profile”

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

dolce + gabbana 2013 and 'our lady of guápulo' in heavenly bodies: fashion and the catholic imagination - andrew bolton (2018)

172 notes

·

View notes

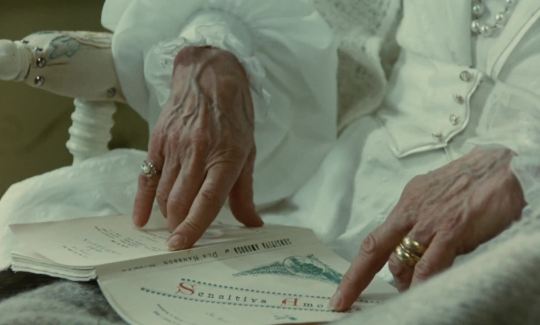

Text

Reliquary hand of Saint Teresa de Jesús, Spanish nun and poet, 16th Century.

515 notes

·

View notes

Photo

the bitter tears of petra von kant (1972)

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suehiro Maruo’s depiction of Saint Sebastian

8K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Angelina Jolie photographed by David LaChapelle for Rolling Stone, 2001

4K notes

·

View notes