#Critical thinking

Text

Pros of reading authors you don't agree with:

You can make informed rants about how wrong they are.

A+ practice for learning to read texts critically and thinking for yourself, even among people you do agree with.

Occasionally, begrudgingly, they may have a point.

Even if they don't, being able to articulate why helps you understand your own beliefs and spot errors in your thinking.

You'll be much more persuasive to the other side if you understand their arguments and aren't just making assumptions based on what you've heard from others.

Academic drama is incredible.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Until you realize how easy it is for your mind to be manipulated, you remain the puppet of someone else's game.

Evita Ochel

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

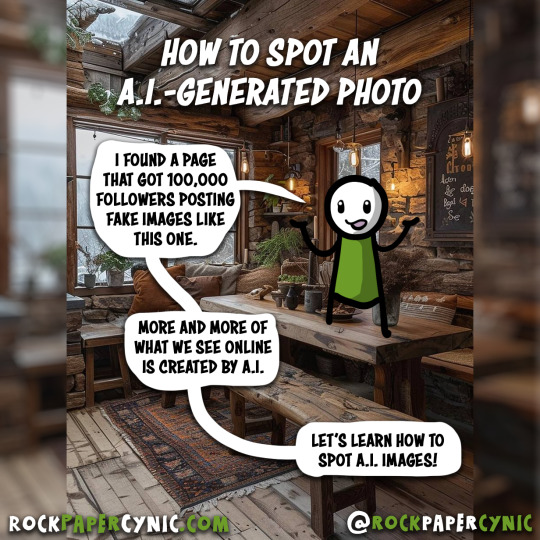

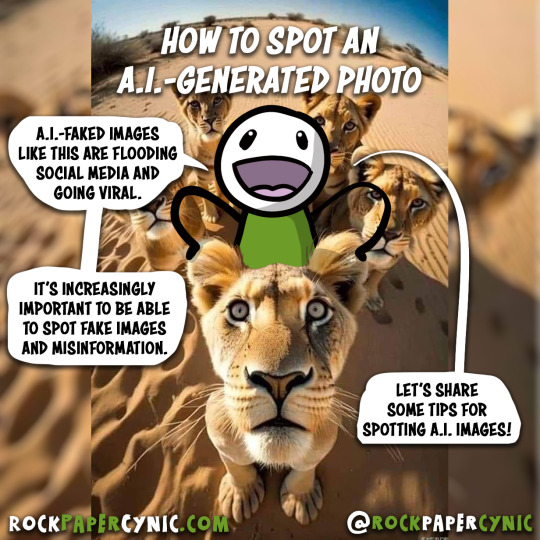

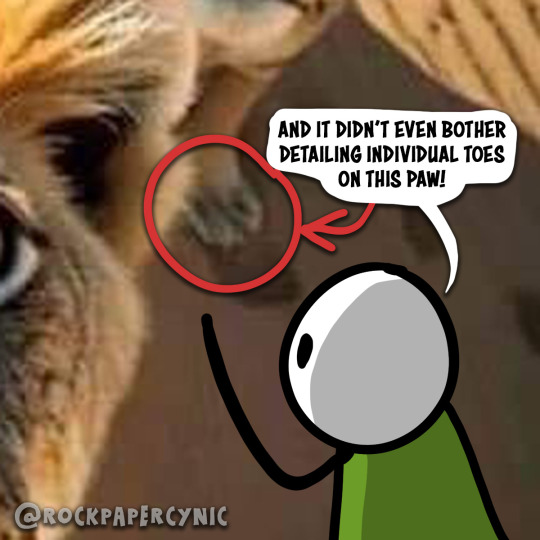

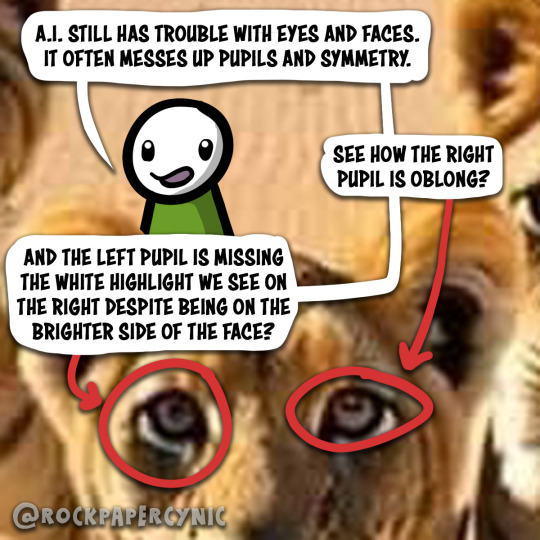

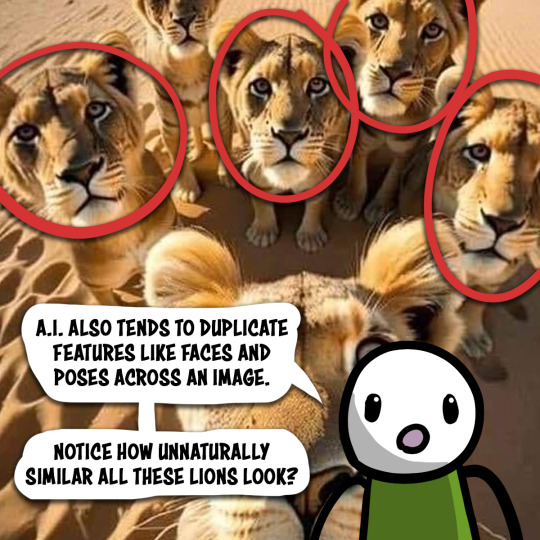

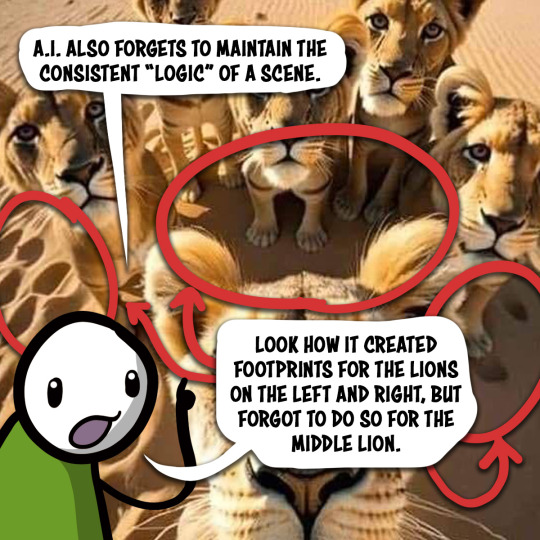

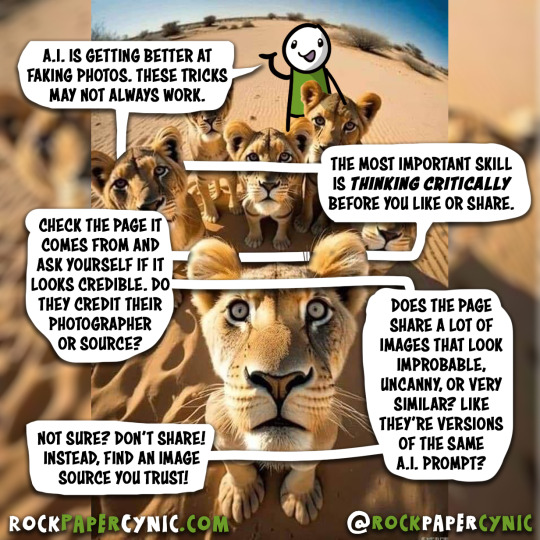

A.I. photos are flooding social media and contributing to an Internet where we can't believe what we see. Spotting A.I. 📷s is an important media literacy skill.

None of us have time to research every image we see. We just need people to notice BEFORE THEY LIKE OR SHARE that an image might be fake. If unsure, check it or don't share.

I've started drawing some comics explaining the basic of AI spot-checking and media literacy in the age of disinformation. Follow along here or on my Twitter.

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Robin After Becoming Robin: omg bruce didn’t replace you!!!! your literally perfect in his eyes. you can do no wrong. and he looks at me and ……. he sees all the ways you were better. he loves you ….. i cant replace you when we dont even compare !

Every Robin When Someone Else Becomes Robin: this mf replaced me

#like guys come on#critical thinking#batfam#batfamily#batman#bruce wayne#robin#batman and robin#dick grayson#Jason Todd#Tim Drake#stephanie brown#damian wayne#2k

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

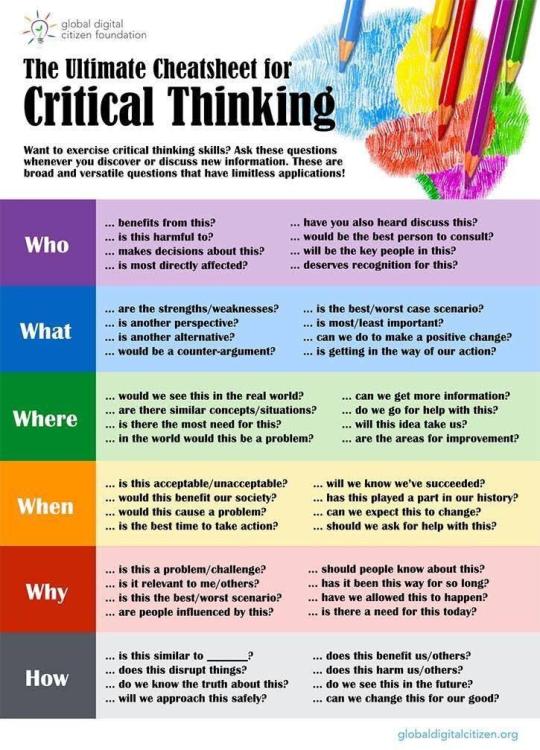

Critical Thinking Cheatsheet

#critical thinking#analysis#problem solving#thinking#life hacks#life tips#life lessons#motivation#mindset#psychology#educational

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

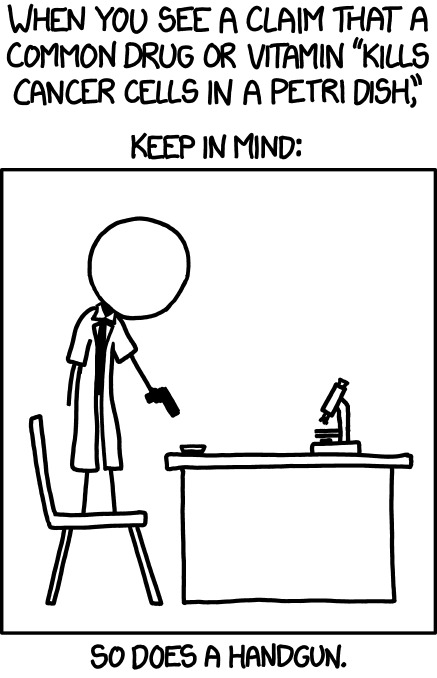

This has been a reminder

#don't trust miracle cures#critical thinking#health#medicine#cancer#cancer ment cw#misinformation#supplements#xkcd#if anyone still doesn't quite get it because i didn't for a hot second lol: you could literally dump a bucket of 'miracle cure' on cells#in a petri dish but if that amount of 'miracle cure' gets into human tissue it might kill em#in other words 'in a petri dish' means nothing because all the rules doses etc that would apply to actual human administration are out#fave

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some hints about evaluating scientific studies

Firstly, understand that something being published in a scientific journal (or an academic journal for the social sciences) does not automatically make it true. Publishers profit from publishing novel, eye-catching, surprising research, which means they are more likely to publish positive results than ones that didn't find a connection between given variables. This means that scientists' careers benefit when they get positive results. Certain institutions also benefit from certain findings above others (a committee for research on "obesity" that is funded by a government organisation tasked with ending it, for example, is likely to try to stretch the evidence to find a link between body weight and poor health outcomes). So how do people evaluate scientific studies, especially without being scientists themselves?

Literature reviews

Literature reviews, which aim to assemble and summarise most of the available or influential papers on a given issue, can be a good place to start when trying to research that issue. Typically, scientific studies shouldn't only be evaluated on a case-by-case basis (since even well-designed studies can be contradicted by other, equally well-designed studies), but a full survey of the different results people have gotten should be taken.

Background information and conflicts of interest

Try to find out who funded a given study. Who published the study? What do these people stand to gain from the results of the study being accepted? (For example: you might pay special attention to the experimental design on a study on whether a certain essential oil helps to reverse hair loss that was carried out by a company that sells that oil.)

In theory, many journals call for study authors to declare any conflicts of interest they may have in a special section of the paper. This section should also list funding sources. You might also look up the authors on linkedin or something to find where they're employed; also look into whether another conglomerate owns that company, &c.

Experimental design

If the study involves a survey, have the authors of the paper provided the questions that people were asked, so that you can evaluate them for potential ambiguity or confusing wording? Not being transparent about the exact wording of questions is a sign that a study isn't trustworthy.

What's the sample size? Is it large enough for the claim the study is making to be reasonable? (More on this in the next section.)

Does the experimental design make sense with what the researchers wanted to study? Are the claims that they make in the conclusion section something that could reasonably be proven or suggested by the experiment that they performed?

Does the experimental design "bake in" an assumption of the truth of its hypothesis? (For example, measuring skeletons to argue that they fall into statistically significant size groupings by sex, using skeletons that you sorted into "male" and "female" groups based on their size, is clearly circular).

How was data collected? People might change their answers to a survey, for example, if they have to speak to a person to give them, rather than writing them down anonymously. Self-reported information (such as a survey aiming to figure out average height or average penis size) is also subject to bias. A good study should be transparent about how the authors collected their data, and be clear about how this could have affected their results.

Also regarding surveys: do the categories that the authors have divided respondents into make sense? Are these categories really mutually exclusive? If respondents were asked to sort themselves into categories (e.g., to select their own race or ethnicity), is there any guarantee that they all interpreted the question / the boundaries of these categories the same way? How would this affect the results?

Interpretation of results

Could anything other than the conclusion that the authors came to explain the results of their experiment? For example, a study finding a correlation between two variables and assuming that this means one variable causes the other ("being in a lot of stress causes short stature" or vise versa) could be missing a secret third thing which is in fact causing both of those things (e.g., poverty). Check to make sure that the authors considered other explanations for their findings and ruled them out (for example, by controlling for other variables such as socioeconomic status).

Are the results of the study generalisable to the population that the authors claim they're generalisable to? For example, the results may not be true for the entire population if only cisgender men between the ages of 30 and 40 were tested. Sampling biases can also affect generalisability—if I surveyed my college to try to find out the percentage of women in the total population, you might ask "but is your college sure to have the same percentage of women as the Earth does?"

Statistics

Are the results statistically significant, or are they within expected margins of error?

Many studies provide a p-value (a number between 0 and 1) for their results. In theory, a p-value represents the chance that the study's results could have been achieved by random chance. If you flip a coin ten times (so, your sample size is 10), it's not very odd to get heads six times and tails four times, and you wouldn't accept that as proof that the coin lands on heads more often than tails. The p-value for that result would be high (that is, there's a high chance that the coin appears unfair only because of random chance). On the other hand, if you flip a coin 100,000 times and it lands on heads 60,000 of those times, that's much better evidence that the coin is not a fair one. The p-value would be much lower. Typically, a p-value lower than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

In practice, there's more than one way to calculate p-values, and so studies sometimes claim p-values that seem absurdly low. A low p-value is not proof of a claim in and of itself. Check to make sure that the authors of the paper also provide the raw data, and not just the p-values; this indicates a concern with other people being able to independently evaluate their results, rather than just trying to get The Best Numbers.

Citations

If the study cites something that seems foundational to their claims or interpretation, try tracing it back to the paper that was cited. Does the source actually claim what the authors of the first study said it did? Does the source provide proof or support for the claim, or does it seem flimsy, like a "common-sense" assumption?

Replication

Check the studies that cite the one you're currently looking at. Has anyone else tried to replicate the study? What were their results?

What if I really, really don't want to read scientific studies?

That's fine. Not everyone is concerned enough with specific scientific questions for regularly reading scientific papers to be reasonable for them. Just keep in mind that not everything in a scientific journal is necessarily true; that profit motives and personal and institutional bias impact results (e.g. when some studies revealed a lack of poor health outcomes for "obesity," and many scientists responded by calling it a "paradox" that needed to be "solved"); and that pop science and journalistic reporting on science are subject to distortions from the same sources.

Try finding commentators on scientific matters whose output you like, and evaluate their writing the same way you would evaluate any other critical writing.

#feel free to add on!#this doesn’t really incorporate the extent of my cynicism wrt to scientific establishment but. lol#reading comprehension#critical thinking

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

tools not rules: the importance of critical thinking

More than once, I’ve talked about the negative implications of Evangelical/purity culture logic being uncritically replicated in fandom spaces and left-wing discourse, and have also referenced specific examples of logical overlap this produces re, in particular, the policing of sexuality. What I don’t think I’ve done before is explain how this happens: how even a well-intentioned person who’s trying to unlearn the toxic systems they grew up with can end up replicating those systems. Even if you didn’t grow up specifically in an Evangelical/purity context, if your home, school, work and/or other social environments have never encouraged or taught you to think critically, then it’s easy to fall into similar traps - so here, hopefully, is a quick explainer on how that works, and (hopefully) how to avoid it in the future.

Put simply: within Evangelism, purity culture and other strict, hierarchical social contexts, an enormous value is placed on rules, and specifically hard rules. There might be a little wiggle-room in some instances, but overwhelmingly, the rules are fixed: once you get taught that something is bad, you’re expected never to question it. Understanding the rules is secondary to obeying them, and oftentimes, asking for a more thorough explanation - no matter how innocently, even if all you’re trying to do is learn - is framed as challenging those rules, and therefore cast as disobedience. And where obedience is a virtue, disobedience is a sin. If someone breaks the rules, it doesn’t matter why they did it, only that they did. Their explanations or justifications don’t matter, and nor does the context: a rule is a rule, and rulebreakers are Bad.

In this kind of environment, therefore, you absorb three main lessons: one, to obey a rule from the moment you learn it; two, that it’s more important to follow the rules than to understand them; and three, that enforcing the rules means castigating anyone who breaks them. And these lessons go deep: they’re hard to unlearn, especially when you grow up with them through your formative years, because the consequences of breaking them - or even being seen to break them - can be socially catastrophic.

But outside these sorts of strict environments - and, honestly, even within them - that much rigidity isn’t healthy. Life is frequently far more complex and nuanced than hard rules really allow for, particularly when it comes to human psychology and behaviour - and this is where critical thinking comes in. Critical thinking allows us to evaluate the world around us on an ongoing basis: to weigh the merits of different positions; to challenge established rules if we feel they no longer serve us; to decide which new ones to institute in their place; to acknowledge that sometimes, there are no easy answers; to show the working behind our positions, and to assess the logic with which other arguments are presented to us. Critical thinking is how we graduate from a simplistic, black-and-white view of morality to a more nuanced perception of the world - but this is a very hard lesson to learn if, instead of critical thinking, we’re taught instead to put our faith in rules alone.

So: what does it actually look like, when rule-based logic is applied in left-wing spaces? I’ll give you an example:

Sally is new to both social justice and fandom. She grew up in a household that punished her for asking questions, and where she was expected to unquestioningly follow specific hard rules. Now, though, Sally has started to learn a bit more about the world outside her immediate bubble, and is realising not only that the rules she grew up with were toxic, but that she’s absorbed a lot of biases she doesn’t want to have. Sally is keen to improve herself. She wants to be a good person! So Sally joins some internet communities and starts to read up on things. Sally is well-intentioned, but she’s also never learned how to evaluate information before, and she’s certainly never had to consider that two contrasting opinions could be equally valid - how could she have, when she wasn’t allowed to ask questions, and when she was always told there was a singular Right Answer to everything? Her whole framework for learning is to Look For The Rules And Follow Them, and now that she’s learned the old rules were Bad, that means she has to figure out what the Good Rules are.

Sally isn’t aware she’s thinking of it in these terms, but subconsciously, this is how she’s learned to think. So when Sally reads a post explaining how sex work and pornography are inherently misogynistic and demeaning to women, Sally doesn’t consider this as one side of an ongoing argument, but uncritically absorbs this information as a new Rule. She reads about how it’s always bad and appropriative for someone from one culture to wear clothes from another culture, and even though she’s not quite sure of all the ways in which it applies, this becomes a Rule, too. Whatever argument she encounters first that seems reasonable becomes a Rule, and once she has the Rules, there’s no need to challenge them or research them or flesh out her understanding, because that’s never been how Rules work - and because she’s grown up in a context where the foremost way to show that you’re aware of and obeying the Rules is to shame people for breaking them, even though she’s not well-versed in these subjects, Sally begins to weigh in on debates by harshly disagreeing with anyone who offers up counter-opinions. Sometimes her disagreements are couched in borrowed terms, parroting back the logic of the Rules she’s learned, but other times, they’re simply ad hominem attacks, because at home, breaking a Rule makes you a bad person, and as such, Sally has never learned to differentiate between attacking the idea and attacking the person.

And of course, because Sally doesn’t understand the Rules in-depth, it’s harder to explain them to or debate with rulebreakers who’ve come armed with arguments she hasn’t heard before, which makes it easier and less frustrating to just insult them and point out that they ARE rulebreakers - especially if she doesn’t want to admit her confusion or the limitations of her knowledge. Most crucially of all, Sally doesn’t have a viable framework for admitting to fault or ignorance beyond a total groveling apology that doubles as a concession to having been Morally Bad, because that’s what it’s always meant to her to admit you broke a Rule. She has no template for saying, “huh, I hadn’t considered that,” or “I don’t know enough to contribute here,” or even “I was wrong; thanks for explaining!”

So instead, when challenged, Sally remains defensive: she feels guilty about the prospect of being Bad, because she absolutely doesn’t want to be a Bad Person, but she also doesn’t know how to conceptualise goodness outside of obedience. It makes her nervous and unsettled to think that strangers could think of her as a Bad Person when she’s following the Rules, and so she becomes even more aggressive when challenged to compensate, clinging all the more tightly to anyone who agrees with her, yet inevitably ending up hurt when it turns out this person or that who she thought agreed on What The Rules Were suddenly develops a different opinion, or asks a question, or does something else unsettling.

Pushed to this sort of breaking point, some people in Sally’s position go back to the fundamentalism they were raised with, not because they still agree with it, but because the lack of uniform agreement about What The Rules Are makes them feel constantly anxious and attacked, and at least before, they knew how to behave to ensure that everyone around them knew they were Good. Others turn to increasingly niche communities and social groups, constantly on paranoid alert for Deviance From The Rules. But other people eventually have the freeing realisation that the fixation on Rules and Goodness is what’s hurting them, not strangers with different opinions, and they steadily start to do what they wanted to do all along: become happier, kinder and better-informed people who can admit to human failings - including their own - without melting down about it.

THIS is what we mean when we talk about puritan logic being present in fandom and left-wing spaces: the refusal to engage with critical thinking while sticking doggedly to a single, fixed interpretation of How To Be Good. It’s not always about sexuality; it’s just that sexuality, and especially queerness, are topics we’re used to seeing conservatives talk about a certain way, and when those same rhetorical tricks show up in our fandom spaces, we know why they look familiar.

So: how do you break out of rule-based thinking? By being aware of it as a behavioural pattern. By making a conscious effort to accept that differing perspectives can sometimes have equal value, or that, even if a given argument isn’t completely sound, it might still contain a nugget of truth. By trying to be less reactive and more reflective when encountering positions different to your own. By accepting that not every argument is automatically tied to or indicative of a higher moral position: sometimes, we’re just talking about stuff! By remembering that you’re allowed to change your position, or challenge someone else’s, or ask for clarification. By understanding that having a moral code and personal principles isn’t at odds with asking questions, and that it’s possible - even desirable - to update your beliefs when you come to learn more than you did before.

This can be a scary and disquieting process to engage in, and it’s important to be aware of that, because one of the main appeals of rule-based thinking - if not the key appeal - is the comfort of moral certainty it engenders. If the rules are simple and clear, and following them is what makes you a good person, then it’s easy to know if you’re doing the right thing according to that system. It’s much, much harder and frequently more uncomfortable to be uncertain about things: to doubt, not only yourself, but the way you’ve been taught to think. And especially online, where we encounter so many more opinions and people than we might elsewhere, and where we can get dogpiled on by strangers or go viral without meaning to despite our best intentions? The prospect of being deemed Bad is genuinely terrifying. Of course we want to follow the Rules. But that’s the point of critical thinking: to try and understand that rules exist in the first place, not to be immutable and unchanging, but as tools to help us be better - and if a tool becomes defunct or broken, it only makes sense to repair it.

Rigid thinking teaches us to view the world through the lens of rules: to obey first and understand later. Critical thinking teaches us to use ideas, questions, contexts and other bits of information as analytic tools: to put understanding ahead of obedience. So if you want to break out of puritan thinking, whenever you encounter a new piece of information, ask yourself: are you absorbing it as a rule, or as a tool?

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

#ethics#critical thinking#capitalism#society#economics#poverty#homelessness#class struggle#inequality#class war#corporatism#working class#class warfare#authoritarianism#communism#anarchism#socialist#antifascist#anarchocommunism#revolution

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

There was never going to be any form of Jewish self defense that the world would deem acceptable, and there was never going to be any act of anti-Jewish terrorism that the world would deem unacceptable.

There is nothing Israel could ever do to defend itself that wouldn’t be accused of going too far, of being “way beyond self defense.” There is no method of Israeli self defense that wouldn’t be maligned as “genocide.”

Inversely, there is no atrocity that could ever be committed against Jews that wouldn’t be denied/excused/justified. There is no level of violence against Jews, however gruesome, however blatant in its goal of genocide and targeting innocents, however many children and babies are burned alive and kidnapped, that wouldn’t be justified as “resistance,” as something that the Jews must have provoked, as the very least that Jews deserve, as something that the terrorists were driven to and couldn’t possibly be expected not to do.

No act of violence against Jews was ever not going to be called “resistance,” and no response from Israel was ever not going to be called a “genocide.”

The only Jewish country in the world was never not going to be maligned as the worst country in the world.

For fuck’s sake, use some critical thinking skills.

#for thousands of years everyone thought they had a really good reason to hate and kill the Jews#that they were even righteous for it#you are not immune to propaganda#antisemitism#israel#jumblr#media bias#critical thinking#critical thinking skills

489 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things I look for in history books:

🟩 Green flags - probably solid 🟩

Has the book been published recently? Old books can still be useful, but it's good to have more current scholarship when you can.

The author is either a historian (usually a professor somewhere), or in a closely related field. Or if not, they clearly state that they are not a historian, and encourage you to check out more scholarly sources as well.

The author cites their sources often. Not just in the bibliography, I mean footnotes/endnotes at least a few times per page, so you can tell where specific ideas came from. (Introductions and conclusions don't need so many citations.)

They include both ancient and recent sources.

They talk about archaeology, coins and other physical items, not just book sources.

They talk about the gaps in our knowledge, and where historians disagree.

They talk about how historians' views have evolved over time. Including biases like sexism, Eurocentrism, biased source materials, and how each generation's current events influenced their views of history.

The author clearly distinguishes between what's in the historical record, versus what the author thinks or speculates. You should be able to tell what's evidence, and what's just their opinion.

(I personally like authors who are opinionated, and self-aware enough to acknowledge when they're being biased, more than those who try to be perfectly objective. The book is usually more fun that way. But that's just my personal taste.)

Extra special green flag if the author talks about scholars who disagree with their perspective and shows the reader where they can read those other viewpoints.

There's a "further reading" section where they recommend books and articles to learn more.

🟨 Yellow flags - be cautious, and check the book against more reliable ones 🟨

No citations or references, or references only listed at the end of a chapter or book.

The author is not a historian, classicist or in a related field, and does not make this clear in the text.

When you look up the book, you don't find any other historians recommending or citing it, and it's not because the book is very new.

Ancient sources like Suetonius are taken at face value, without considering those sources' bias or historical context.

You spot errors the author or editor really should've caught.

🟥 Red flags - beware of propaganda or bullshit 🟥

The author has a politically charged career (e.g. controversial radio host, politician or activist) and historical figures in the book seem to fit the same political paradigm the author uses for current events.

Most historians think the book is crap.

Historical figures portrayed as entirely heroic or villainous.

Historical peoples are portrayed as generally stupid, dirty, or uncaring.

The author romanticizes history or argues there has been a "cultural decline" since then. Author may seem weirdly angry or bitter about modern culture considering that this is supposed to be a history book.

The author treats "moral decline" or "degeneracy" as actual cultural forces that shape history. These and the previous point are often reactionary dogwhistles.

The author attributes complex problems to a single bad group of people. This, too, is often a cover for conspiracy theories, xenophobia, antisemitism, or other reactionary thinking. It can happen with both left-wing and right-wing authors. Real history is the product of many interacting forces, even random chance.

The author attempts to justify awful things like genocide, imperialism, slavery, or rape. Explaining why they happened is fine, but trying to present them as good or "not that bad" is a problem.

Stereotypes for an entire nation or culture's personality and values. While some generalizations may be unavoidable when you have limited space to explain something, groups of people should not be treated as monoliths.

The author seems to project modern politics onto much earlier eras. Sometimes, mentioning a few similarities can help illustrate a point, but the author should also point out the limits of those parallels. Assigning historical figures to modern political ideologies is usually misleading, and at worst, it can be outright propaganda.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. "Big theory" books like Guns, Germs and Steel often resort to cherry-picking and making errors because it's incredibly hard for one author to understand all the relevant evidence. Others, like 1421, may attempt to overturn the historical consensus but end up misusing some very sparse or ambiguous data. Look up historians' reviews to see if there's anything in books like this, or if they've been discredited.

There are severe factual errors like Roman emperors being placed out of order, Cleopatra building the pyramids, or an army winning a battle it actually lost.

When in doubt, my favorite trick is to try to read two books on the same subject, by two authors with different views. By comparing where they agree and disagree, you can more easily overcome their biases, and get a fuller picture.

(Disclaimer - I'm not a historian or literary analyst; these are just my personal rules of thumb. But I figured they might be handy for others trying to evaluate books. Feel free to add points you think I missed or got wrong.)

933 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wading through native plant gardening resources and trying to inform other people, both through posts and in real life, has shifted my point of view on what misinformation is and does.

I don't really know what to do with it yet. But I've realized that it's often impossible to be accurate when teaching people who know very little about a subject. You have to simplify incredibly complex, nuanced things to the point where it feels like a total hack job. If you specify every complexity of the thing you're explaining, the people you're talking to don't absorb the core principle.

Various posts i've made about ecology and gardening stuff have been called "misinformation" and I'm just like. Think of it as a highschool textbook. Half of what it says is wrong but you must understand the "wrong" model to move beyond it.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

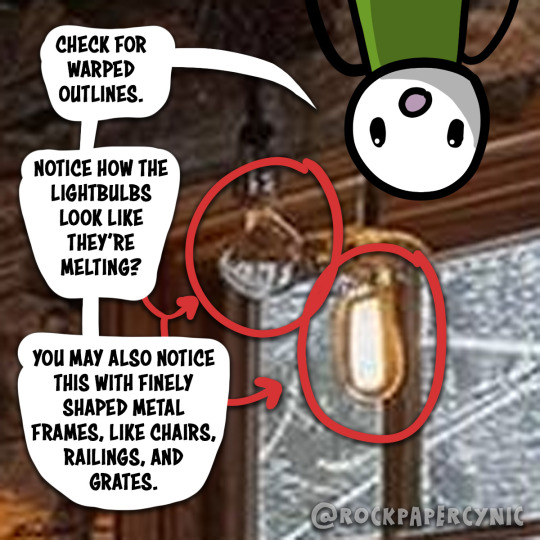

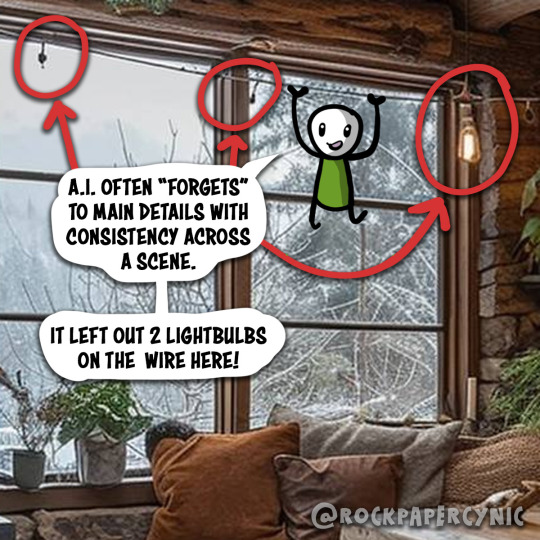

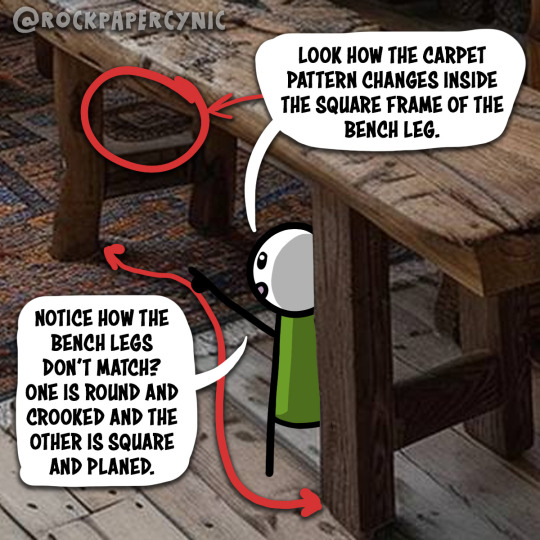

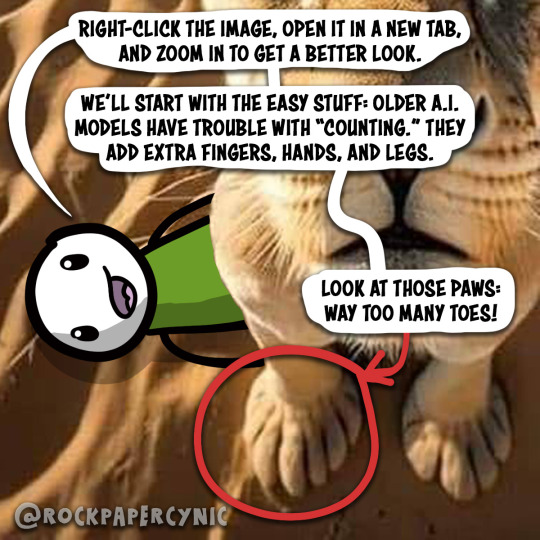

The internet is flooded with AI-generated photos and they're getting harder to spot.

Most of the time AI is used for click-farming, but lately images have been used in fake news stories and product scams.

Most important: THINK CRITICALLY. AI will eventually get too good to make obvious mistakes. Being media literate means checking not just if an image is real, but if the source is trustworthy.

If you're not sure, don't share! You might be spreading misinformation.

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

There's no coming to consciousness without pain.

Carl Gustav Jung

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

seeing people consider their own critical thinking skills in response to Plagiarism and You(tube), i'd like to share the SOAPSTone analysis framework i learned in AP lang & comp.

Speaker: who is this person? what are their credentials? any obvious motivations, personal or financial?

Occasion: when did the speaker say/write this thing? yesterday? a decade ago? was it for a specific event, or perhaps part of a larger series?

Audience: who did the speaker expect their message to reach? a certain age group? a specific fanbase? people with certain political opinions?

Purpose: why did the speaker say/write what they did on this occasion? what did they want the audience to think or do in response to their message?

Subject: what is the speaker talking about? is there a reason to take them seriously on this topic? why did they bring it up on this occasion?

Tone: how did the speaker choose to address their target audience? as a friend? a supplicant? an authority? why did the speaker choose this tone?

#was gonna write an example using this framework to describe hbomberguy's video but YIKES i should be asleep in bed already#i'd describe his tone as a combination of professional outrage and heartfelt grief though#suz yells#hbomberguy#plagiarism and you(tube)#critical thinking

995 notes

·

View notes

Text

idk at this point you should know every article, every history book, every science book, etc. is using data or in some cases outright fabricating data to make an argument. and you do need to learn how these arguments are formed and whether or not you agree with the framing.

333 notes

·

View notes