#9 September 1791

Photo

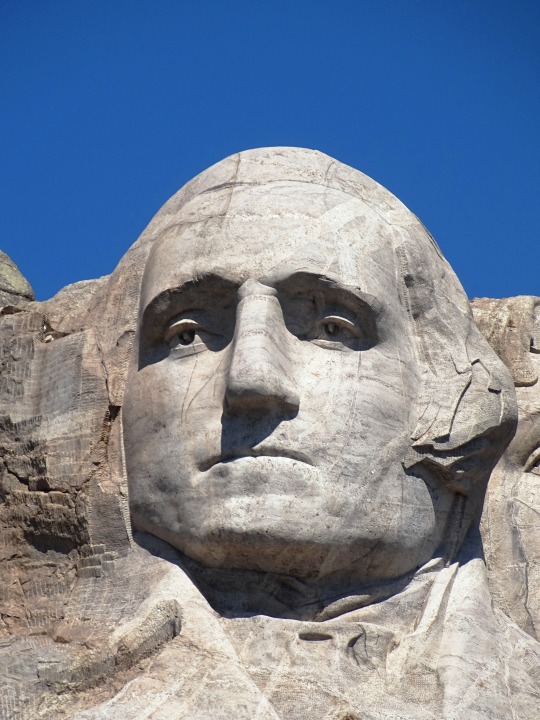

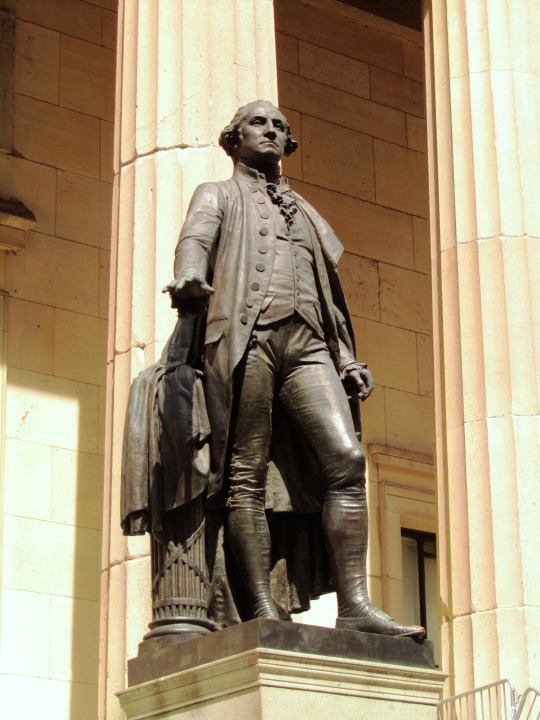

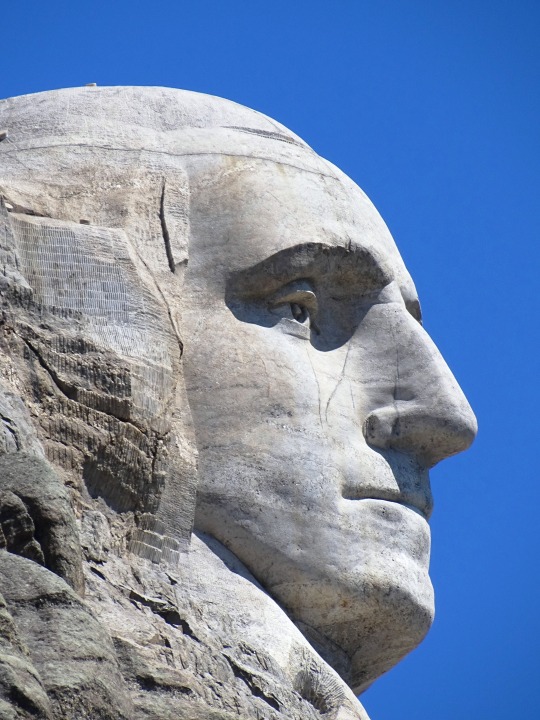

Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, was named after President George Washington on September 9, 1791.

#Washington DC#named#9 September 1791#anniversary#US history#USA#travel#summer 2009#architecture#National Mall#White House#Reflecting Pool#George Washington#Washington Monument#US Capitol#cityscape#original photography#Mount Rushmore National Memorial#Manhattan#New York City#Philadelphia#tourist attraction#landmark#vacation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

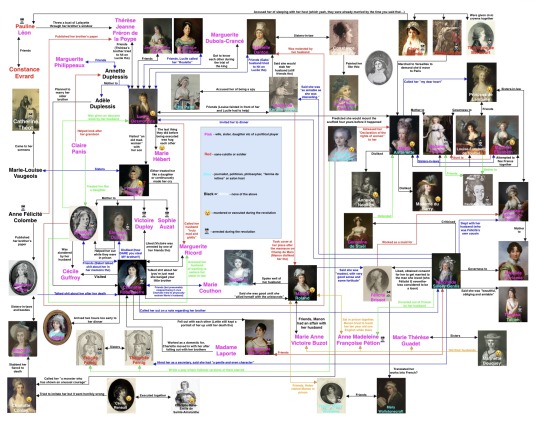

I decided to try this but for the girlies instead.

Are you sure want to click on ”keep reading”?

For Pauline Léon marrying Claire Lacombe’s host, see Liberty: the lives of six women in Revolutionary France (2006) by Lucy Moore, page 230

For Pauline Léon throwing a bust of Lafayette through Fréron’s window and being friends with Constance Evrard, see Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire (2006) by Claude Guillon.

For Françoise Duplay’s sister visiting Catherine Théot, see Points de vue sur l’affaire Catherine Théot (1969) by Michel Eude, page 627.

For Anne Félicité Colombe publishing the papers of Marat and Fréron, see The women of Paris and their French Revolution (1998) by Dominique Godineau, page 382-383.

For the relationship between Simonne Evrard and Albertine Marat, see this post.

For Albertine Marat dissing Charlotte Robespierre, see F.V Raspail chez Albertine Marat (1911) by Albert Mathiez, page 663.

For Lucile Desmoulins predicting Marie-Antoinette would mount the scaffold, see the former’s diary from 1789.

For Lucile being friends with madame Boyer, Brune, Dubois-Crancé, Robert and Danton, calling madame Ricord’s husband ”brusque, coarse, truly mad, giddy, insane,” visiting ”an old madwoman” with madame Duplay’s son and being hit on by Danton as well as Louise Robert saying she would stab Danton, see Lucile’s diary 1792-1793.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Marie Hébert, see this post.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Thérèse Jeanne Fréron de la Poype, and the one between Annette Duplessis and Marguerite Philippeaux, see letters cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife: passages from the history of the dantonists (1876) page 463-464 and 464-469.

For Adèle Duplessis having been engaged to Robespierre, see this letter from Annette Duplessis to Robespierre, seemingly written April 13 1794.

For Claire Panis helping look after Horace Desmoulins, see Panis précepteur d’Horace Desmoulins (1912) by Charles Valley.

For Élisabeth Lebas being slandered by Guffroy, molested by Danton, treated like a daughter by Claire Panis, accusing Ricord of seducing her sister-in-law and being helped out in prison by Éléonore, see Le conventionnel Le Bas : d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve, page 108, 125-126, 139 and 140-142.

For Élisabeth Lebas being given an obscene book by Desmoulins, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre dissing Joséphine, Éléonore Duplay, madame Genlis, Roland and Ricord, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834), page 76-77, 90-91, 96-97, 109-116 and 128-129.

For Charlotte Robespierre arriving two hours early to Rosalie Jullien’s dinner, see Journal d’une Bourgeoise pendant la Révolution 1791–1793, page 345.

For Charlotte Robespierre and Françoise Duplay’s relationship, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 85-92 and Le conventional Le Bas: d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1902) page 104-105

For the relationship between Charlotte Robespierre and Victoire and Élisabeth Lebas, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre visiting madame Guffroy, moving in with madame Laporte and Victoire Duplay being arrested by one of Charlotte’s friends, see Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961)

For Louise de Kéralio calling Etta Palm a spy, see Appel aux Françoises sur la régénération des mœurs et nécessité de l’influence des femmes dans un gouvernement libre (1791) by the latter.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 198-207

For the relationship between Madame Pétion and Manon Roland, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 158 and 244-245 as well as Lettres de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 510.

For the relationship between Madame Roland and Madame Buzot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland (1793), volume 1, page 372, volume 2, page 167 as well as this letter from Manon to her husband dated September 9 1791. For the affair between Manon and Buzot, see this post.

For Manon Roland praising Condorcet, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 14-15.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 1, page 360.

For the relationship between Helen Maria Williams and Manon Roland, see Memoirs of the Reign of Robespierre (1795), written by the former.

For the relationship between Mary Wollstonecraft and Helena Maria Williams, see Collected letters of Mary Wollstonecraft (1979), page 226.

For Constance Charpentier painting a portrait of Louise Sébastienne Danton, see Constance Charpentier: Peintre (1767-1849), page 74.

For Olympe de Gouges writing a play with fictional versions of the Fernig sisters, see L’Entrée de Dumourier à Bruxelles ou les Vivandiers (1793) page 94-97 and 105-110.

For Olympe de Gouges calling Charlotte Corday ”a monster who has shown an unusual courage,” see a letter from the former dated July 20 1793, cited on page 204 of Marie-Olympe de Gouges: une humaniste à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (2003) by Oliver Blanc.

For Olympe de Gouges adressing her declaration to Marie-Antoinette, see Les droits de la femme: à la reine (1791) written by the former.

For Germaine de Staël defending Marie-Antoinette, see Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine par une femme (1793) by the former.

For the friendship between Madame Royale and Pauline Tourzel, see Souvernirs de quarante ans: 1789-1830: récit d’une dame de Madame la Dauphine (1861) by the latter.

For Félicité Brissot possibly translating Mary Wollstonecraft, see Who translated into French and annotated Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman? (2022) by Isabelle Bour.

For Félicité Brissot working as a maid for Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis: sur le dix-huitième siècle et sur la révolution française, volume 4, page 106.

For Reine Audu, Claire Lacombe and Théroigne de Méricourt being given civic crowns together, see Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel, September 3, 1792.

For Reine Audu taking part in the women’s march on Versailles, see Reine Audu: les légendes des journées d’octobre (1917) by Marc de Villiers.

For Marie-Antoinette calling Lamballe ”my dear heart,” see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 197, 209 and 252.

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Madame du Barry, see https://plume-dhistoire.fr/marie-antoinette-contre-la-du-barry/

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Anne de Noailles, see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 30.

For Louise-Élisabeth Tourzel and Lamballe being friends, see Memoirs of the Duchess de Tourzel: Governess to the Children of France during the years 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1795 volume 2, page 257-258

For Félicité de Genlis being the mistress of Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon’s husband, see La duchesse d’Orléans et Madame de Genlis (1913).

For Pétion escorting Madame Genlis out of France, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis…, volume 4, page 99.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume, page 352-354

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Germaine de Staël, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 2, page 316-317

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théophile Fernig, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 300-304

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 106-110, as well as this letter dated June 1783 from Félicité Brissot to Félicité Genlis.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théresa Cabarrus, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume (1857) page 391.

For Félicité de Genlis inviting Lucile to dinner, see this letter from Sillery to Desmoulins dated March 3 1791.

For Marinette Bouquey hiding the husbands of madame Buzot, Pétion and Guadet, see Romances of the French Revolution (1909) by G. Lenotre, volume 2, page 304-323

Hey, don’t say I didn’t warn you!

#french revolution#frev#marie antoinette#pauline léon#claire lacombe#théroigne méricourt#reine audu#charlotte robespierre#éléonore duplay#élisabeth duplay#élisabeth lebas#lucile desmoulins#louise de kéralio#félicité de genlis#félicité brissot#mary wollstonecraft#manon roland#madame royale#charlotte corday#albertine marat#simonne evrard#catherine théot#madame élisabeth#sophie condorcet#françoise duplay#cécile renault#gabrielle danton#louise sebastien danton#theresa tallien#theresa cabarrus

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collaborative Masterpost on Saint-Just

Primary Sources

Oeuvres complètes available online: Volume 1 and Volume 2

A few speeches

L'esprit de la révolution et de la constitution de la France (1791)

Transcription of the Fragments sur les institutions républicaines (1800) kept at the BNF by Pierre Palpant

Alain Liénard's edition and transcription of his works in Théorie politique (1976)

Some letters kept in Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. (1828)

Fragment autographe des Institutions républicaines

Une lettre autographe signée de Saint-Just, L. B. Guyton et Gillet (not his writing but still interesting)

Two files at the BNF with his writing (and other strange random stuff):

Notes et fragments autographes - NAF 24136

Fragments de manuscrits autographes, avec pièces annexes provenant de Bertrand Barère, de V. Expert et d'H. Carnot - NAF 24158

Albert Soboul's transcription of the Institutions républicaines + explanation of what's in these files at the BNF

Anne Quenneday's philological note on the manuscript by Saint Just, wrongly entitled De la Nature (NAF 12947)

Masterpost (inventory, anecdotes, etc.) - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Chronology

Chronology from Bernard Vinot's biography

Testimonies

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas on Saint-Just, as reported by David d'Angers - by frevandrest and robespapier

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas corrects Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des girondins (1847) - by anotherhumaninthisworld

Many testimonies by contemporaries (in French) on antoine-saint-just.fr

Representations

Everything Wrong with Saint-Just's Introductory Scene in La Révolution française (1989) - by frevandrest

On Saint-Just's strange representation of "throwing tantrums" - by saintjustitude and frevandrest

Saint-Just as "goth/emo boy"? - by needsmoreresearch, frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

Recommended Articles

Bernard Vinot:

"La révolution au village, avec Saint-Just, d'après le registre des délibérations communales de Blérancourt", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 335, Janvier-Mars 2004, p. 97-110

Alexis Philonenko:

"Réflexions sur Saint-Just et l'existence légendaire", Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale, 77e Année, No. 3, Juillet-Septembre 1972, p. 339-355

Miguel Abensour:

"Saint-Just, Les paradoxes de l'héroïsme révolutionnaire", Esprit, No. 147 (2), Février 1989, p. 60-81

"Saint-Just and the Problem of Heroism in the French Revolution", Social Research, Vol. 56, No. 1, "The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity", Spring 1989, p. 187-211

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux". Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 183, Janvier-Mars 1966, p. 1-32. (première partie)

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 185, Juillet-Septembre 1966, p. 341-358 (suite et fin)

Louise Ampilova-Tuil, Catherine Gosselin et Anne Quennedey:

"La bibliothèque de Saint-Just: catalogue et essai d'interprétation critique", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 379, Janvier-mars 2015, p. 203-222

Jean-Pierre Gross:

"Saint-Just en mission. La naissance d'un mythe", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, Année 1968, no. 191 p. 27-59

Marie-Christine Bacquès:

"Le double mythe de Saint-Just à travers ses mises en scène", Siècles, no. 23, 2006, p. 9-30

Marisa Linton:

"The man of virtue: the role of antiquity in the political trajectory of L. A. Saint-Just", French History, Volume 24, Issue 3, September 2010, p. 393–419

Misc

Saint-Just in Five Sentences - by sieclesetcieux

On Saint-Just's Personality: An Introduction - by sieclesetcieux

Pictures of Saint-Just's former school, with the original gate - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Saint-Just vs Desmoulins (the letter to d'Aubigny and other details) - by frevandrest

Saint-Just's sisters - by frevandrest

On Thérèse Gellé and Henriette Le Bas - by frevandrest

Saint-Just and Gellé being godparents - by frevandrest and robespapier

On Saint-Just "stealing" and running away to Paris and the correction house - by frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

How was/is Saint-Just pronounced - Additional commentary in French by Anne Quenneday

#saint-just#antoine saint just#saint just#to be updated#masterpost#refs#sources#frev sources#testimonials and commentaries

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the current consensus on the date for SJ’s “embrace Desmoulins for me”… letter ? I thought it was July ‘92, but lately I’ve seen someone (I forget where!) say that 91 had been demonstrated to be more likely .

Hi, it's general consensus now that the letter Saint-Just wrote to his friend from Blérancourt Daubigny where he says this "Embrace Desmoulins for me..." "Tear out my heart and eat it..." (and many other dramatic things) almost certainly predates July 1792 because of the letter's contents. Bernard Vinot, one of the most knowledgeable historians of SJ, believes it probably comes from rather July 1791. And I'd have to agree with him because as Hampson states in his biography, that according to Vinot and other historians:

"... Since Saint-Just asks Daubigny to show something that he had written or published to Lameth and Barnave, important political leaders in 1791, who had disappeared from the scene a year later, when Barnave was no longer in Paris. Most historians have assumed that ‘1792’ was a mistake for 1791 and that Saint-Just was reacting to his failure to get elected to the assembly, but on 20 July of 1792, things seemed to be going well for Antoine and it was not until September that his hopes were suddenly destroyed."

Here's an excerpt of the letter, and I'd recommend checking out Norman Hampson's Saint-Just biography pg. 31-33 and Bernard Vinot's biography of SJ for more information!

"You are a freedman of glory and liberty: preach it in your Sections, and may the peril of it inflame your soul! Go and see Desmoulins; embrace him for me; tell him that he will never see me again; tell him that I esteem his patriotism, but that I despise himself, because I have read his soul, and know that he fears I my betray him. Tell him not to abandon the good cause, and recommend it to him all the more because he has not as yet the courage that comes from great-hearted virtue."

<< ... Compagnon de gloire et de liberté, prêchez-la dans vos sections; que le péril vous enflamme. Allez voir Desmoulins, embrassez-le pour moi, et dites-lui qu'il ne me reverra jamais, que j'estime son patriotisme, mais que je le méprise, lui, parce j'ai pénétré son àme, et qu'il craint que je ne le trahisse. >>

-Letter to Daubigny from Saint-Just discovered and published after 9 Thermidor.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atrocities US committed against WOMEN

In 2022, the US supreme court overturned Roe V Wade, ending a constitutional guarantee to the right to have an abortion, in place for over 50 years. In response, 26 US states are expected to ban abortion in their state. Women who become pregnant in red states, will now have to drive an increased average of over 200 miles to an abortion clinic. Protests erupted in hundreds of US cities, decrying the decision.

US police officers routinely commit sexual assault and rapes: most go unreported, but over 1200 incidents, including over 400 rapes were committed over a 9 year period from 2005-2013.

In the period following WWII, the US capitalist-controlled media, advertising, and consumer products industries propagandized and glorified the ideal of the housewife-consumer, in order to sell products, make labor space for returning soldiers, take advantage of women’s unpaid labor in the home, and to help build a new workforce and potential army to combat the soviet union. This sparked an era of regression with respect to the feminist victories of the previous 50 years, and caused psychological damage and demoralization to an uncountable number of women. Women who remained in the labor force were primarily only allowed in subordinate positions such as secretaries, cleaning women, elementary school teachers, saleswomen, waitresses, and nurses. This is chronicled in the Feminine Mystique.

In September 2020, it was revealed that ICE had performed mass hysterectomies on immigrant women in several detention centers, reminiscent of the long-standing US policy of sterilization of black and brown women.

From the 1880s onward, many US states (27 + Puerto Rico in 1956) operated a system of forced sterilization of women, rooted in white supremacy. The principle targets were the mentally ill, Native Americans, and blacks. For example, in Sunflower County Mississippi, 60% of black women living there were sterilized without their permission. An estimated 3,406 Indian women were sterilized. California eugenicists in 1933 began sending their literature overseas to german scientists and medical workers, sparking the beginnings of Nazi Eugenics. In the end, over 65,000 individuals were sterilized in 33 states, in all likelihood without the perspectives of ethnic minorities. The US enacted a system of forced sterilization in Puerto Rico since its takeover by the US in 1989: a 1965 survey of of Puerto Rican residents found that about one-third of all Puerto Rican mothers, ages 20-49, were sterilized. 148 female prisoners in two California institutions were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in a supposedly voluntary program, but it was determined that the prisoners did not give consent to the procedures. In Madrigal vs. Quilligan, many unsuspecting women were coerced to sign paperwork to perform sterilization, while others were told that the process could be reversed. None of the women were fluent in English. 10 latina women were sterilized, and the doctor was found innocent.

US elites in the 18th and 19th centuries pushed a narrative of domestic purity, or the cult of true womanhood, for women as a way of pacifying her with a doctrine of “separate but equal”-giving her work equally as important as the man’s, but separate and different. Inside that “equality” there was the fact that the woman did not choose her mate, and once her marriage took place, her life was determined. One girl wrote in 1791: “The die is about to be cast which will probably determine the future happiness or misery of my life…. I have always anticipated the event with a degree of solemnity almost equal to that which will terminate my present existence.” Marriage enchained, and children doubled the chains. One woman, writing in 1813: “The idea of soon giving birth to my third child and the consequent duties I shall he called to discharge distresses me so I feel as if I should sink.”

In 2019, it was discovered that US Border patrol had been protecting rapes and abuse of its own members since the 1990s. In one instance, a trainee was forced to give oral sex to 5 officers, and then raped while she was unconcious. At least 35 instances of rape by officers was found.

In May, 2019, Alabama lawmakers banned abortion in the state, providing no exceptions for victims of rape or incest. Those caught performing abortions will face up to 99 years in prison. The bill is part of a larger effort to overturn Roe vs Wade, a long-standing supreme court decision affirming a woman’s right to choose. Alabaman women seeking abortions are now forced to travel across state lines, and hide everything about the procedure from friends and family, in order to avoid legal repercussions from their home state. The American Civil Liberties Union has filed a federal suit against the state.

On November 25, 2017, Yang Song died after falling from a 4th floor balcony during a targeted police raid. Her personal messages revealed that in 2016, she was raped at gunpoint by an undercover police officer, and was subsequently harrassed, threatened with deportation, and then likely murdered by the NYPD.

In the 1830s, The Lowell Mill Girls were female workers who came to work in industrial factories in Lowell, Massachusetts, during the Industrial Revolution, and who despite living in cramped boarding houses and working from 5am-7pm every day, developed a culture of defiance against the factory owners, and created reform associations, and began strikes in 1834 and 1836.

#radical feminist safe#anti capitalism#socialism#anarchy#leftism#communism#radical feminists do touch#radical feminists do interact#social commentary#radical feminist community#radical feminism#american history#rip twitter#ronald reagan#imperialism#us history#us politics#radical feminists please touch#radical feminists please interact#serious

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect

Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide

for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure

the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do

ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of

America.

Article I.

Section 1. All legislative Powers herein granted shall be

vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist

of a Senate and House of Representatives.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

* * * * *

\1\This text of the Constitution follows the engrossed copy signed by

Gen. Washington and the deputies from 12 States. The small superior

figures preceding the paragraphs designate clauses, and were not in the

original and have no reference to footnotes.

* * * * *

The Constitution was adopted by a convention of the States on September

17, 1787, and was subsequently ratified by the several States, on the

following dates: Delaware, December 7, 1787; Pennsylvania, December 12,

1787; New Jersey, December 18, 1787; Georgia, January 2, 1788;

Connecticut, January 9, 1788; Massachusetts, February 6, 1788;

Maryland, April 28, 1788; South Carolina, May 23, 1788; New Hampshire,

June 21, 1788.

* * * * *

Ratification was completed on June 21, 1788.

* * * * *

The Constitution was subsequently ratified by Virginia, June 25, 1788;

New York, July 26, 1788; North Carolina, November 21, 1789; Rhode

Island, May 29, 1790; and Vermont, January 10, 1791.

* * * * *

In May 1785, a committee of Congress made a report recommending an

alteration in the Articles of Confederation, but no action was taken on

it, and it was left to the State Legislatures to proceed in the matter.

In January 1786, the Legislature of Virginia passed a resolution

providing for the appointment of five commissioners, who, or any three

of them, should meet such commissioners as might be appointed in the

other States of the Union, at a time and place to be agreed upon, to

take into consideration the trade of the United States; to consider how

far a uniform system in their commercial regulations may be necessary

to their common interest and their permanent harmony; and to report to

the several States such an act, relative to this great object, as, when

ratified by them, will enable the United States in Congress effectually

to provide for the same. The Virginia commissioners, after some

correspondence, fixed the first Monday in September as the time, and

the city of Annapolis as the place for the meeting, but only four other

States were represented, viz: Delaware, New York, New Jersey, and

Pennsylvania; the commissioners appointed by Massachusetts, New

Hampshire, North Carolina, and Rhode Island failed to attend. Under the

circumstances of so partial a representation, the commissioners present

agreed upon a report (drawn by Mr. Hamilton, of New York) expressing

their unanimous conviction that it might essentially tend to advance

the interests of the Union if the States by which they were

respectively delegated would concur, and use their endeavors to procure

the concurrence of the other States, in the appointment of

commissioners to meet at Philadelphia on the second Monday of May

following, to take into consideration the situation of the United

States; to devise such further provisions as should appear to them

necessary to render the Constitution of the Federal Government adequate

to the exigencies of the Union; and to report such an act for that

purpose to the United States in Congress assembled as, when agreed to

by them and afterwards confirmed by the Legislatures of every State,

would effectually provide for the same.

scared you, didn’t I?

This is MY JOKE, McTALLISTER

I’M THE ANON WHO SENDS THESE

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

do u have any info on Thèrése Gellé and SJ's relationship?

I have all the info there is! Which... is not much. What we know is that something likely did exist in terms of a romantic relationship in their teens (and maybe later, but that one is not proven). Some things could be extrapolated from little that we know, but we have only a few facts. What we know is the following:

Thérèse Gellé was born in 1766 in Blérancourt, as an illegitimate child of a local merchantess and a powerful royal notary Gellé. She was legitimized at 12, when her parents married each other.

SJ moved to Blérancourt at the age of 9. Thérèse was 10. We don't know when they met but since this was a super small community, I assume they knew each other (or at least, knew of each other) as kids.

At some point during their teen years, they seemed to have started a romantic relationship. There are no concrete sources for it except that it’s generally accepted that it happened. What we know is that in December 1785, they were godparents to a child in the village. Some historians see this as a sign that they were seen as a future married couple and chosen together because of this. I am not sure how sound this theory is, but I do think it’s interesting that they were chosen together.

Interestingly, most of the proof/sources for the relationship come from SJ’s early writing (namely, Organt and Arlequin-Diogène). While Thérèse is not mentioned by name, the context and certain (auto)biographical details that appear in these works strongly point out that the main female characters were based on her. (If anyone wants me to talk about what SJ’s writing (potentially) says of Thérèse and/or their relationship, I’d love to do that - I just have to do it in a different post because this one is getting super long).

According to some, SJ asked Gellé for a permission to marry Thérèse and was refused. Not sure if this is true, but since SJ was 18 at the time and still in school, AND not particularly rich, it’s not surprising that Gellé wanted a more “prosperous” option for his daughter.

Which brings us to 25 July 1786. While SJ was away at the boarding school, Thérèse married Emmanuel Thorin, a young notary from a rich family. Historians agree that this marriage (done seemingly in a hurry) was specifically to prevent SJ from marrying her.

SJ graduated and returned from school a few weeks later, and he lost it. Reportedly, he had a huge fight with his mother (for not telling him that Thérèse was getting married? For not presenting him as a good option to Gellé?) Soon after, in early September 1786, he took that infamous silver and ran away to Paris. (I assume this episode is familiar. It resulted with his mother putting him in the correctional house where he stayed for six months, until early 1787).

We don’t know what - if anything - happened between SJ and Thérèse after these events. What we do know is that the Revolution started and Gellé was a royalist who tried to stop revolutionary efforts in the village (he was the one who outed SJ as being too young to be elected for the Legislative Assembly in 1791). So yes, there was a lot of animosity between SJ and Gellé on the political grounds, but we don’t know anything about Thérèse during these years or how she might have reacted to all of this.

But there is a significant event in summer 1793. On the 7th anniversary of her marriage, Thérèse left Thorin and went to Paris. She stayed in a hotel very close to SJ’s place. We know this because SJ’s friend, Victor Thuillier, wrote a much-quoted letter about it. In the letter, he informs SJ that the village believes that SJ had kidnapped Thérèse (not against her will?) and also gives SJ Thérèse’s address in Paris. To which SJ replied basically: “I have no idea what you’re talking about. Tell everyone (in the village) that it’s not true. I am very busy, bye”. (Not direct quotes - you can read more in the link above, though not sure if it’s the best way to translate these letters).

Historians are divided over what happened. Those who are sympathetic towards SJ want to defend him against accusations of having an affair with a married woman, so they trust his word on it. Those unsympathetic towards SJ generally think that he lied and that he was totally behind Thérèse’s escape to Paris.

But what I am more concerned about is how things worked form Thérèse’s POV. She left her husband, AND the village thought that it was because of SJ. This ruined her reputation beyond repair. Even if she did not cheat on Thorin, she was the one who was seen as leaving.

As for SJ, nobody really talks about a possibility that he did help her, but not necessarily as a lover but as a friend - he wrote so much about protecting women from abuse and unwanted marriages that it wouldn’t be so impossible that he helped a childhood friend (tbh, it would be more shitty if he refused after writing so much about helping women). As for the affair... We don’t have any proof either way (except his reply to Thuillier). I disagree with historians who claim that “SJ would never”, because most of his writings actually point out that he was fine with women performing marital infidelity and the like. But this is not a proof either. So we just don’t know.

Thérèse and Thorin had a divorce hearing in September 1793. Historians point out that the reason for the divorce they listed was not adultery, but Thorin didn’t seem to ask for a no-fault, mutual decision divorce either. He seemed to ask or a divorce based on the fact that she left him. In the hearing, Thérèse said that the divorce was mutually desired and she seemed to have asked for her dowry back. Their divorce was decided then, but they had to wait for about 11 months for it to become legal. They were legally divorced in July 1794 (18 days before Thermidor).

That is basically it. We have no idea if SJ and Thérèse had any contact or what she did between this divorce hearing and Thermidor. We do know that she was kind of shunned in the village, while Thorin remarried and had children. Thérèse died in 1806, at the age of 39.

There is one thing, written by SJ near Thermidor, that some people argue could be related to Thérèse, but there is absolutely no proof of it: that strange “story” about a lovers’ misunderstanding. It was the last item written in the notebook found on SJ during Thermidor, and it is super unusual because he left no other writing of this kind, but it’s impossible to say whether it has anything to do with Thérèse or not.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

M. d’orleans Can not Recover Himself from the Muddy Swamp into which I have Kicked Him By the Middle of October 1789—and Whatever Happens to all Around Him, He Hardly Can Raise His Head Above the dirty Heap which Entangles Him on Every Side.

The Marquis de La Fayette to George Washington, January 22, 1792

Strong words my dear, strong words ...

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 22 January 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 493–495.] (09/29/2022)

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#french revolution#american history#history#letter#george washington#1792#founders online#1789#duc d'orléans

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

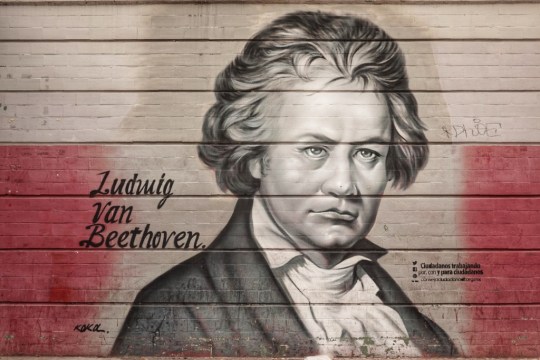

MEXICO CITY, MEXICO STREET ART: LEGENDARY MUSICAL ICONS by KOKA

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period.

José Juventino Policarpo Rosas Cadenas (25 January 1868 – 9 July 1894) was a Mexican composer and violinist.

Adelina Patti (19 February 1843 – 27 September 1919) was an…

View On WordPress

#art#cdmx#Graffiti#life#mexico#mexico city#murals#nomad#photography#Street Art#TOKIDOKI Nomad blog#TOKIDOKI Nomad travel blog#Travel#urban art#World Travel

0 notes

Text

Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, was named after President George Washington on September 9, 1791.

#Washington DC#named#George Washington#9 September 1791#US history#anniversary#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#architecture#cityscape#New York City#USA#Mount Rushmore National Memorial#Gutzon Borglum#John Quincy Adams Ward#Lincoln Memorial#White House#US Capitol#Smithsonian Institution#sculptur

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pauline Léon timeline

A timeline over the 70 year old life of Pauline Leclerc née Léon, based primarily on the article Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire (2006) by Claude Guillon.

-

19 October 1767 — Mathurine Téholan and Pierre Paul Léon are married in the parish of Saint-Severin in Paris. Pierre Paul runs a small chocolate business on 356 rue de Grenelle. The couple settles on rue du Basq.

28 September 1768 — birth of Anne Pauline Léon, the couple’s first child. They later have four more children — Antoine Paul Louis (1772-1835), Marie Reine Antoinette, (1778), François Paul Mathurin (1779) as well as a child who’s sex and year of birth remains unknown. Pauline later describes her father as: ”a philosopher” and adds: ”If his lack of fortune did not allow him to give us a very brilliant education, at least he left us with no prejudices.”

1784 — death of Pierre Paul Léon. Pauline, aged sixteen, now starts helping her mother with keeping the chocolate business running in order to provide for the family.

14 July 1789 — Fall of the Bastille. Pauline claims to upon this event have felt ”the liveliest enthusiam, and although a woman I did not remain idle; I was seen from morning to evening animating the citizens against the artisans of tyranny, urging them to despise and brave aristocrats, barricading streets, and inciting the cowardly to leave their homes to come to the aid of the fatherland in danger.”

February 1791 — Pauline is introduced to several popular societies in Paris. She herself claims she would frequent the Cordelier Club up until 1794 (though there doesn’t seem to exist any trace of her in the debates held there), the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes (where again, we have few documents that mention any direct activity from her part), as well as the section of Mucius Scaevola. The same month, Pauline defenestrates a bust of Lafayette “at Fréron’s”. It seems unlikey for this attack to have been aimed at the journalist Stanislas Fréron, who frequently denounced Lafayette in his l’Orateur du Peuple, but rather his mother Anne Françoise Fréron, who handled the publishing of the royalist paper L’Ami du Roi.

21 June 1791 — Pauline, her mother and their neighbor Constance Évrard are near the Palais Royal loudly protesting the king’s ”infamous treason” (his flight) when they, according to her, are ”almost assassinated by Lafayette’s mouchards” and are saved by other sans-culottes who manage to snatch them ”from the hands of these monsters” (National guardsmen)

17 July 1791 — Pauline takes part in the demonstration on the Champ-de-Mars. On the way home, she uses her fists to defend a friend against the family of a national guard. This last incident is witnessed by Constance Evrard, another sans-culotte woman and friend of Pauline, who reports it during an interrogation. This is the first conserved trace of any militant activities from Pauline.

Late February 1792 — l’Adresse individuelle à l’Assemblée nationale par des citoyennes de la capitale, a petition regarding women’s right to bear arms, is penned down. It was most likely written by Pauline herself, seeing as the first signature on the bottom of the handwritten version kept in the National Archives, as well as the only one appearing in the version printed by order of the Assembly, is “fille Léon.” After Pauline’s name about 310 more follow, including that of her mother and many other daughter-mother couples. The petition is first read out before the Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, which, under the presidency of Tallien, orders its printing and distribution.

March 9 1792 — the Patriotic Society of the Luxembourg section sends a delegation to the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes to request affiliation. The latter club grants the request and appoints five auditors to attend the former’s next meeting, among which are three women: Pauline Léon, Constance Evrard and Marie-Charlotte Hardon. Pauline will actively participate in the recruitment of members for the Patriotic Society, personally presenting or supporting at least seven candidates between October 1792 and September 1793

June 1792 — Pauline, along with many other men and women, signs Pétition individuelle au corps législatif pour lui demander la punition de tous les conspirateurs that calls for ”a quick vengeance” against monarchist ministers.

10 August 1792 — Pauline takes part in the Insurrection of August 10. She describes her activities in the following way: "On August 10, 1792, after spending part of the night in the Fontaine-de-Grenelle section, I joined the next day, armed with a pike, the ranks of the citizens of this section to go and fight the tyrant and his satellites. It was only at the request of almost all the patriots that I consented to give up my weapon to a sans-culotte; I gave it to him, however, only on the condition that he would use it well.”

December 1792 — Pauline, together with 3 other women and 88 men, signs the Adresse au peuple par la Société patriotique de la section du Luxembourg which demands the death of the king and pronounces threats against eventual monarchist deputies.

2 February 1793 — During a session at the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, Pauline is welcomed as mandated by the Defenders of the Republic of the 84 departments. At the same session, Pauline’s future husband Théophile Leclerc (1771-1820) is charged with writing a petition against commodity money. This is the first known meeting between the two.

3 February 1793 — during the session at The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, ”Citoyenne Léon” takes the floor to continue a denounciation against Dumouriez that Hébert has just made. Le Créole patriote reports that ”she thinks, like him, that [Dumouriez] is nothing more than an intrigant; she accuses him of several things, notably the persecution he inflicted on two patriotic battalions unjustly accused by him.”

10 February 1793 — Le Créole patriote reports the following regarding the session at The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes:

Citoyenne Léon informs of an important denunciation made to the Commune and to the society of defenders of the republic, one and indivisible of the 84 departments. This denunciation, signed, states that on the 6th of the month a dinner was held at the house of Garat, minister of justice, provisionally exercising the functions of minister of interior, where Brissot, Barbaroux, Louvet and other noirs, composing the great and famous right side of the National Convention; plus, Bournonville, new minister of war. She calls on the society to monitor the latter, and asks that two of its members be sent to that of the Jacobins to communicate to them this fact, to which the most serious attention must be paid. Boussard makes the motion that the president be instructed to write to Bournonville, so that he can give the company explanations on this subject. These three proposals are adopted.

At the Jacobin Club the same day, ”a citoyenne,” in the name of the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, makes the following intervention: ”Citizens, I denounce to you Garat, minister of justice, who last Wednesday had thirty people to dinner, among which were Brissot, Barbaroux, Louvet and Beurnonville. The patriots do not have entry to this minister, and Brissot comes and goes there all the time.” It is very likely this speaker was Pauline.

17 February 1793 — Le Créole patriote reports that, during the session at The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, ”citoyenne Léon reads a denunciation from Citizen Godchaux against General Félix Wemphen. Several members believe that this denunciation is well founded, and urge the society to tear off the mask from all the intriguers.”

10 May 1793 — Pauline is a co-founder of the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women (Société des Républicaines révolutionnaires or Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires de Paris), a club which only admits women as members and holds its meetings at the libary of the Jacobins, rue Saint-Honoré. Claire Lacombe, who often gets mentioned as another co-founder, actually doesn’t have her first attested appearance as a member of the society until June 26. Already on the May 12, the club presents itself at the Jacobins, proposing to arm patriotic women between ages 18 and 50 in order to organize them against the Vendée. A week later, May 19, a delegation made up of members from both the Cordeliers and Revolutionary and Republican Women present themselves before the Jacobins yet again, asking for the arrest of all suspect people, the establishment of both revolutionary tribunals in all departments and a revolutionary sans-culotte army in every town, an act of accusation against the girondins, the extermination of “the stockbrokers, the hoarders and the selfish merchants” who are responsible for a conspiracy attempting to starve the people, that the revolutionary army of Paris be increased to 40,000 men, that land be distributed to the soldiers, as well as the send forth of the petition to the Convention. Though Pauline’s presence can be supposed for both of these occasions, we don’t have any hard evidence for it.

2 June 1793 — Pauline leads a delegation from the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women wishing to be admitted to the Convention, carrying a request in her own handwriting. They are however quickly forgotten in the tumult caused by the Insurrection of May 31, which this day ends with 22 girondins being put under house arrest. During this same insurrection, several Revolutionary and Republican Women are arrested, and Pauline, as president of the Society, signs a warrant by which they demand the liberation of one of them, detained for having threatened three men with a knife.

June 1793 — Pauline is the author of a denounciation against the grocer Le Doux, rue du Sépulcre, accused of “bad comments,” mainly consisting of complains about the looting. We don’t know if the denounciation had any consequences.

9 July 1793 — Le Réglement de la Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires de Paris is published. The document is signed by president Rousaud and four secretaires: Potheau, Monier, Dubreuil och Pauline Léon.

July 10 1793 — Pauline goes to the Jacobin club, where she, ”in the name of the Revolutionary and Republican Women, presents a petition demanding the exclusion of nobles from all employments.”

July 20 1793 — A Délibération de la Société des Républicaines révolutionnaires, relative à l’érection d’un obélisque à la mémoire de Marat, sur la place du Carrousel, is signed by Pauline. The text is read at the Jacobins on July 26, by a deputation from the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women.

July 31 1793 — Réglement de la Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires de Paris is published. The document is signed by the president, Rousaud, and four secretaries: Potheau, Monier, Dubreuil and Pauline Léon.

15 August 1793 — At the Jacobin club, ”citoyenne Léon, at the head of a deputation from the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women, comes to request assimilation and correspondence for said Society. She also asks that the Jacobins contribute to the costs of the obelisk erected in Marat’s honor.”

30 October 1793 — Jean Pierre André Amar, member of the Committee of General Security, announces the dissolution of the Society of Revolutionary Women to the National Convention.

12 November 1793 — the marriage contract between Pauline Léon and Théophile Leclerc is signed. Through it, we see that the husband brings property valued at 300 livres, while the wife holds 1000 livres consisting of both money and effects. Pauline was in other words richer than Leclerc. She declares to after her marriage have returned to the chocolate making business and ”devoted myself entirely to the care of my household and given the example of conjugal love and the domestic virtues which are the basis of love of the homeland.”

March 17 1794 — Pauline joins Leclerc at La Fère (Aisne), where the latter is mobilizing.

April 3 1794 — the Leclerc couple are arrested on orders given by the Committee of General Security. They are taken to Paris and locked up in the Luxembourg prison three days later.

4 July 1794 — At the Luxembourg prison, Pauline either writes or dictates Précis de la conduite révolutionnaire de dame Pauline Léon, femme Leclerc, which is adressed to the Committee of General Security. It is from this document we learn almost all the details regarding her militant activities and private life. Unfortunately, I’ve not been able to find it published in full.

5 August 1794 — Pauline writes to ”sensible Tallien” and pleads for the cause of ”800 imprisoned people.” One day later she adresses herself to to ”the representatives” and asks them to at least consider a prompt examination of their case. Pauline claims that Leclerc and Pierre-François Réal were imprisoned for having "collected evidence against the accomplices of the tyrant Robespierre who were to have their throats slit." The following day, the two men are brought before the Committee of General Security. Réal is immediately set free, Pauline and Théophile joins him on August 22.

22 July 1804 — Pauline writes the following letter (cited in full within the article Un sans-culotte parisien en l’an XII: François Léon, frère de Pauline Léon (1982) by Michael David Sibalis) to Réal, by now one of those in charge of the general police, asking for the liberation of her younger brother François Paul Mathurin, imprisoned since three and a half months back for having written and published leaflets critical of Napoleon. Through the letter, we learn about some things that have happened in her life during the ten years since the last trace of her:

4 Thermidor [year 12]

Monsieur,

A month ago I presented a petition to the Grand Judge; at the same time I had the honor of writing to you, to request the release of my brother, named François Léon, imprisoned in the Bicêtre for a bad verse; I would ask for your indulgence, today I appeal to your justice; four months of such harsh detention had to atone for his fault; moreover his friend guilty of the same extravagance, since of two verses, one wrote the first and the other the second, was released; my brother is not more guilty, perhaps he is less; his delicacy did not allow him to justify himself at the expense of his friend; which certainly does not deserve punishment. Based on this, Monsieur, I believe I have the right to ask for his release; and I have the firm confidence that you will grant it to us; if you could still deign to think of his mother, who is old and more punished than him. This poor woman is exhausted trying to help and console him. She who needs help for herself, I am not talking to you about the grief her family is experiencing at the loss of my time (which is precious since it must be used to feed my son and relieve my mother), having, Monsieur, the advantage of having known you, I think you will not disdain these considerations.

Salut and respect,

Femme Leclerc

Teacher (Instritutrice)

Rue Jean Robert No. 4

François will be set free and leave Paris, the police having labeled him as a ”pronounced anarchist, difficult to correct.” In his interrogation, held May 2 1804 (it too cited in full within Un sans-culotte parisien en l’an XII…) he reveals that he is a tailor living alone on rue du Vieux Colombier N. 744 and ”very republican.”François’ accomplice Jean Sorret did in his interrogation claim that his friend was ”a pronounced jacobin, as is the rest of his family.”

October 5 1838 — death of Pauline in Bourbon-Vendée, rue de Bordeaux, one week after her seventieth birthday. She had moved there to settle with her sister Marie Reine Antoinette and her family somewhere between 1812 and 1835.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five steps of Wikipedia for Wednesday, 27th March 2024

Welcome, ongi etorri, bienvenue, ยินดีต้อนรับ (yin dee dtôn rab) 🤗

Five steps of Wikipedia from "Jean-Pierre Reveau" to "1792 French National Convention election". 🪜👣

Start page 👣🏁: Jean-Pierre Reveau

"Jean-Pierre Reveau (born 1932) is a French politician...."

Step 1️⃣ 👣: National Assembly (France)

"The National Assembly (French: Assemblée nationale; pronounced [asɑ̃ble nɑsjɔnal]) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (Sénat). The National Assembly's legislators are known as députés (French pronunciation: [depyte]),..."

Image by The Government of the French Republic, specifically, the National Assembly of France. Vector image by Mnmazur

Step 2️⃣ 👣: 1795 French legislative election

"Legislative elections were held in France between 12 and 21 October 1795 (20 to 29 Vendémiaire, Year IV) to elect one-third of the members of the Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Ancients, the lower and upper houses of the legislature. The elections were held in accordance with the..."

Step 3️⃣ 👣: 1791 French legislative election

"Legislative elections were held in France between 29 August and 5 September 1791 and were the first national elections to the Legislature. They took place during a period of turmoil caused by the Flight and Arrest at Varennes, the Jacobin split, the Champ-de-Mars Massacre and the Pillnitz..."

Step 4️⃣ 👣: 1793 French constitutional referendum

"The French Constitution of 1793 was approved by a referendum in the summer of 1793. It was held via universal male suffrage, with voting on different days in different departments, in some cases after the result was proclaimed in Paris on 9 August 1793. While most voters abstained, of those who..."

Step 5️⃣ 👣: 1792 French National Convention election

"Legislative elections were held in France at the end of August and in September 1792 to elect deputies to the National Convention. Primary elections to elect members of electoral colleges were held in August, with the electoral colleges subsequently voting from 2 to 19 September. The elections..."

0 notes

Text

Study memo: the French Revolution

Book<The Oxford History of the French Revolution>

Read on 2024/1/

*Introduction:*

Embark on a captivating exploration of the tumultuous era that defined France's destiny - the French Revolution. Unravel the layers of history as we delve into the pivotal moments that shaped a nation.

**1. France under Louis XVI**

- Step into the challenges of Louis XVI's reign, where soaring flour and bread prices ignited protests, unveiling deep-seated social issues.

**2. Enlightened Opinion**

- Immerse yourself in the world of Enlightenment thinkers whose progressive ideas rewired the fabric of governance, society, and individual rights.

**3. Crisis and Collapse**

- Navigate the storm as France faced formidable problems, triggering a cascade of events marked by uncertainty and instability.

**4. The Estates-General, September 1788-July 1789**

- Witness the birth of change as representatives from diverse social groups convened, laying the groundwork for a transformative journey.

**5. The Principles of 1789 and the Reform of France**

- Encounter the revolutionary principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity that emerged in 1789, sparking reforms to address social inequalities.

**6. The Breakdown of the Revolutionary Consensus, 1789-1791**

- Navigate through internal conflicts among revolution supporters, revealing the challenges within the heart of change.

**7. Europe and the Revolution, 1788-1791**

- Explore the ripple effect as other European nations keenly observed and responded to the revolutionary waves, shaping international relations.

**8. The Republican Revolution, October 1791-January 1793**

- Witness the metamorphosis from monarchy to republic, a monumental shift in governance that echoed across the pages of history.

**9. War against Europe, 1792-1797**

- March alongside France as it engages in conflicts with neighboring nations resisting revolutionary ideas, a chapter defined by war.

**10. The Revolt of the Provinces**

- Feel the pulse of regional discontent as various parts of France express their rebellion against central authority.

**11. Government by Terror, 1793-1794**

- Enter a phase marked by a potent government response, including the stark reality of the guillotine, designed to suppress opposition and maintain control.

**12. Thermidor, 1794-1795**

- Experience a period of transformation following intense government control, signaling a departure from extreme measures.

**13. Counter-Revolution, 1789-1795**

- Witness the opposition that brewed against revolutionary changes, leading to counter-revolutionary movements.

**14. The Directory, 1795-1799**

- Explore the emergence of a new governance model striving to stabilize France after the turbulent storms of revolution.

**15. Occupied Europe, 1794-1799**

- Follow France's expansion of influence, as it extends its grasp over parts of Europe during this defining period.

**16. An End to Revolution, 1799-1802**

- Witness the gradual conclusion of the revolutionary era, marking a transition towards a more stable phase in history.

**17. The Revolution in Perspective**

- Reflect on the entirety of the revolutionary canvas, evaluating its profound impact and drawing lessons from its enduring legacy.

*Conclusion:*

Conclude our journey through history, summarizing the poignant moments and enduring impact of the French Revolution that continue to echo through the corridors of time.

1 note

·

View note

Link

#AdmiralNelson#Armut#Aufstieg#Briefe#deutsch#England#Flotte#Gesellschaft#Krieg#LadyHamilton#Liebe#Lust#Neapel#Reichtum#Romanze#Schönheit#Verführung#Verrat

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Sufferings of the Queen of France

Die Hinrichtung Marie-Antoinettes, anonymes Gemälde, 1793

"Marie Antoinette (* 2. November 1755 in Wien; † 16. Oktober 1793 in Paris) wurde als Erzherzogin Maria Antonia von Österreich geboren. Durch Heirat mit dem Thronfolger Ludwig August wurde sie am 16. Mai 1770 Dauphine von Frankreich. Nach der Thronbesteigung ihres Gatten als Ludwig XVI. war sie vom 10. Mai 1774 an Königin von Frankreich und Navarra; während der Französischen Revolution trug sie vom 4. September 1791 bis zum 10. August 1792 den Titel Königin der Franzosen. Anfänglich beliebt, wurde sie schon unter dem Ancien Régime zum Ziel massiver, teils polemischer, Kritik. Neun Monate nach ihrem Ehemann wurde sie mit der Guillotine hingerichtet."

(Quelle)

Jean-Étienne Liotard: Erzherzogin Maria Antonia von Österreich im Alter von sieben Jahren, 1762 (Musée d’art et d’histoire, Genf)

"The Sufferings of the Queen of France (Die Leiden der Königin von Frankreich), auch bekannt unter den Titeln La Mort de Marie-Antoinette und Le tableau Marie-Antoinette, ist ein Klavierzyklus des böhmischen Komponisten und Pianisten Johann Ladislaus Dussek (1760–1812), welcher in zehn programmatischen Einzelstücken den Leidensweg und die Apotheose der französischen Königin Marie-Antoinette beschreibt."

Der Zyklus besteht aus folgenden zehn Einzelnummern:

No. 1, The Queen’s Imprisonment (Largo, c-Moll, 4/4)

No. 2, She reflects on her former Greatness, (Maestosamente, Es-Dur, 4/4)

No. 3, They separate her from her Children, (Agitato assai, c-Moll, 2/2)

No. 4, They pronounce the Sentence of Death, (Allegro con furia, Es-Dur, 3/4)

No. 5, Her Resignation to her Fate, (Adagio innocente, Es-Dur, 3/4)

No. 6, The Situation and Reflections the Night before her Execution, (Andante agitato, As-Dur/d-Moll, 3/4)

No. 7, March, (Lento, d-Moll, 4/4)

No. 8, The savage Tumult of the Rabble, (Presto furioso, B-Dur, 3/4)

No. 9, The Queen’s Invocation to the Almighty just before her Death, (Molto adagio, E-Dur, 3/4)

No. 10, The Apotheosis, (Allegro maestoso, C-Dur, 4/4)

(Quelle)

Freut mich ungemein, von diesem total vergessenen Werk eine Aufnahme von Andreas Staier gefunden zu haben. Lange nicht mehr an ihn gedacht und er ist mir als sehr gefühlvoller Schubert-Interpret in Erinnerung:

The Sufferings of the Queen of France, Op. 23, Andreas Staier

youtube

0 notes

Text

The story of the Extra Regiment's ordinary soldiers: From McCay to Patton [Part 10]

Continued from part 9

Giles Thomas, a Virginian, and Thomas Gadd, Marylander

In August 1832, Giles Thomas appeared before justices of the court saying that he he was 68 years old, having no evidence of his service "except a certificate for a lot of bounty land of Fifty acres" and that his name "is not on the pension roll of the agency of any State." He would be dead by 1850, as he is in censuses from 1810 to 1840. Living in Montgomery County, Virginia, he would die by 1842, with reports that he enlisted at the age of 16. Even a paperback book by W. Conway Price and Anne Price Yates titled Some Descendants of Giles Thomas, Revolutionary Soldier claims to go over his life story, and is available through the Virginia Tech University Libraries.

Reprinted from my History Hermann WordPress blog.

By 1840, Giles, age 76, was still living in Montgomery County as a census of pensioners made clear. Originally from Charles County, Maryland, he had at least one child with his wife Nancy: a daughter named Elenor/Eleanor who had married into the Barnett family, living from about 1791 to 1853. Some within the DAR (Daughters of American Revolution) have clearly done research on him since he is represented by one member in a New York chapter. Then we get to his Find A Grave entry which says his spouse was Nancy Ann Wheeler (1762-1845) and that they had two children named William Jenkins (1796-1863), and Elias (1801-1877) and describes him as a person born on November 30, 1763 in Baltimore County, Maryland and married Nancy on June 04, 1786 in Blacksburg, Montgomery County, Virginia. On March 21, 1842, he died, with his gravestone describing him as a private within the Maryland line:

Courtesy of Find A Grave

Then we get to Thomas Gadd, who was born January 1760 in Baltimore and reportedly died in Rockcastle, Kentucky. Some say he died in 1832 (probably based on pages out of this book), but this is incorrect. His entry on Find A Grave says he died in 1834 and was put in an unmarked grave. In 1833, he was put on Kentucky Pension Rolls, and was age 74, living in Rockcastle County. [31] Other genealogical researchers seem to indicate that he had at least five children, including William. This cannot be further confirmed. [32]

However, a number of realities are clear. He seems to have been living in the county as early as 1810. Additionally, he was was alive as late as May 23, 1833 when he made the following deposition in Jesse Williams's pension:

I Thomas Gadd state, that I was in the Revolutionary War, and served in the same Batalion mentioned by the above applicant [Jesse Williams] in his original declartion but under diferent Captains. but I was well acquainted with the officers named by said applicant. I was not personally acquainted with the applicant in the service, but from a long acquaintance with him since and from conversations with him years ago and having served the same kind of service myself I have no doubt but he has stated the truth in his declaration & that he served as he states. Given under my hand this 23d day of May 1833

Hence, he could have died in 1834 after all.

The 1830s and 1840s: William Elkins, Giles Thomas, and William Patton

In 1835, William Elkins was on the pension roll and was living in Jefferson County, Ohio. [33] Sometime later on, he was buried somewhere in Jefferson County, although the location is not altogether clear.

Five years later, Giles Thomas is still alive and breathing in Montgomery, Virginia. A census that year describes Giles as a revolutionary pensioner who is 76 years old, basically saying he was born in 1764, putting his age 16 when joining the extra regiment. [34]

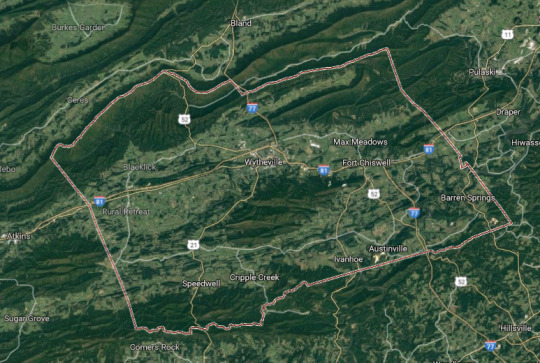

Jump forward another five years. William Patton appeared before magistrates in Wythe County, Virginia, aged 90 years, 8 months, and six days, putting his birthday sometime in September 28, 1754 by my calculations. The following year he says he was age 91, meaning he was born in 1755, differing from what he said the previous year. Hence, his age is not fully clear.

Map of Wythe County Virginia. Courtesy of Google Maps.

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#virginia#maryland#1830s#19th century#1810s#1760s#pensions#gravestones#tombstones#extra regiment#regiment extra#maryland history

0 notes