Text

Centrists Are the Most Hostile to Democracy, Not Extremists

“The warning signs are flashing red: Democracy is under threat. Across Europe and North America, candidates are more authoritarian, party systems are more volatile, and citizens are more hostile to the norms and institutions of liberal democracy.

These trends have prompted a major debate between those who view political discontent as economic, cultural or generational in origin. But all of these explanations share one basic assumption: The threat is coming from the political extremes.

On the right, ethno-nationalists and libertarians are accused of supporting fascist politics; on the left, campus radicals and the so-called antifa movement are accused of betraying liberal principles. Across the board, the assumption is that radical views go hand in hand with support for authoritarianism, while moderation suggests a more committed approach to the democratic process.

Is it true?

Maybe not. My research suggests that across Europe and North America, centrists are the least supportive of democracy, the least committed to its institutions and the most supportive of authoritarianism.

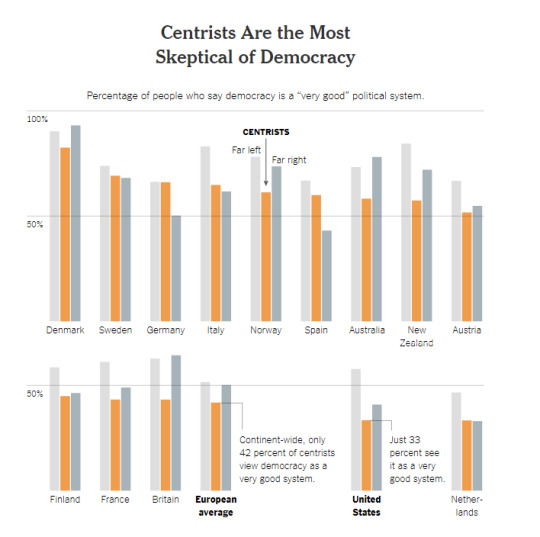

I examined the data from the most recent World Values Survey (2010 to 2014) and European Values Survey (2008), two of the most comprehensive studies of public opinion carried out in over 100 countries. The survey asks respondents to place themselves on a spectrum from far left to center to far right. I then plotted the proportion of each group’s support for key democratic institutions. (A copy of my working paper, with a more detailed analysis of the survey data, can be found here.)

Respondents who put themselves at the center of the political spectrum are the least supportive of democracy, according to several survey measures. These include views of democracy as the “best political system,” and a more general rating of democratic politics. In both, those in the center have the most critical views of democracy.

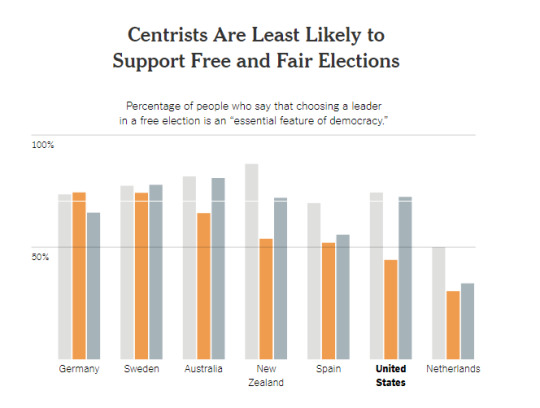

Some of the most striking data reflect respondents’ views of elections. Support for “free and fair” elections drops at the center for every single country in the sample. The size of the centrist gap is striking. In the case of the United States, fewer than half of people in the political center view elections as essential.

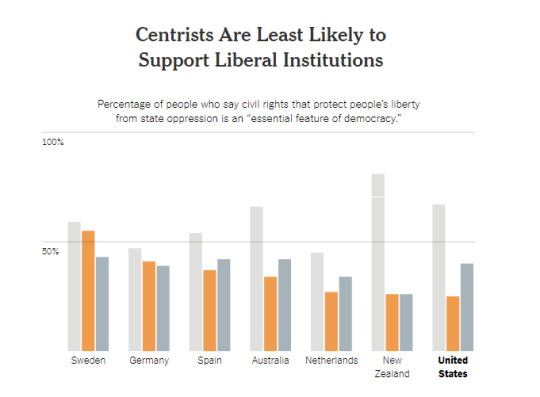

Of course, the concept of “support for democracy” is somewhat abstract, and respondents may interpret the question in different ways. What about support for civil rights, so central to the maintenance of the liberal democratic order? In almost every case, support for civil rights wanes in the center. In the United States, only 25 percent of centrists agree that civil rights are an essential feature of democracy.

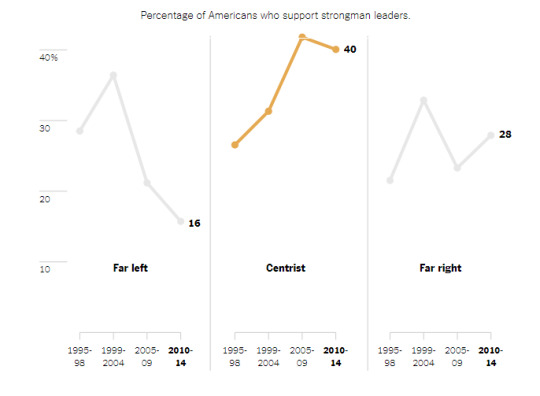

One of the strongest warning signs for democracy has been the rise of populist leaders with authoritarian tendencies. But while these leaders have become more popular, it is unclear whether citizens explicitly support more authoritarian styles of government. I find, however, evidence of substantial support for a “strong leader” who ignores his country’s legislature, particularly among centrists. In the United States, centrists’ support for a strongman-type leader far surpasses that of the right and the left.

Across Europe and North America, support for democracy is in decline. To explain this trend, conventional wisdom points to the political extremes. Both the far left and the far right are, according to this view, willing to ride roughshod over democratic institutions to achieve radical change. Moderates, by contrast, are assumed to defend liberal democracy, its principles and institutions.

The numbers indicate that this isn’t the case. As Western democracies descend into dysfunction, no group is immune to the allure of authoritarianism — least of all centrists, who seem to prefer strong and efficient government over messy democratic politics.

Strongmen in the developing world have historically found support in the center: From Brazil and Argentina to Singapore and Indonesia, middle-class moderates have encouraged authoritarian transitions to bring stability and deliver growth. Could the same thing happen in mature democracies like Britain, France and the United States?”

---from the article Centrists Are the Most Hostile to Democracy, Not Extremists by David Adler

#sociology#politics#centrism#centrists#left wing#right wing#democracy#united states#europe#north america#extremism#authoritarianism#denmark#sweden#germany#italy#norway#spain#australia#new zealand#austria#finland#france#britain#netherlands#civil rights

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Don’t Just Need Nicer Cops. We Need Fewer Cops.

12/04/14

“Protests against the recent police killings of unarmed black men and boys—Eric Garner and Akai Gurley in New York, Michael Brown in Ferguson, John Crawford and 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Ohio—have put the policing of communities of color on the top of the local and national agenda. Signs are even emerging of a new level of social movement activity around racial justice and the criminal justice system that may outlast the current wave of anger and heartbreak.

What stands before us, therefore, is the hard work of both building political power and articulating what that change might look like. So far politicians, police and even many community leaders have trotted out many of the well-worn proposals that have failed to deliver in the past and offer little hope for the future.

While the racial imbalance between the police and the policed in Ferguson was no doubt a contributing factor in the breakdown of community trust in the police, increasing police diversity is unlikely to improve things much on its own. Increasingly, large urban police departments are becoming much more diverse and reflective of the communities being policed. For years, Philadelphia police have had to live in the city, resulting in a department that largely mirrors the city’s demographics. That department, however, has been rife with corruption, mismanagement and excessive use of force. As a result, residents of color have seen little relief from the daily indignities of discourtesy and aggressive criminalization. Even the NYPD has significantly enhanced its diversity in recent years in terms of race, ethnicity, gender and language skills, but few are likely to claim that this has led to a dividend of courtesy or respect.

Recent uproars over the diversity of NYPD leadership in recent months are a further red herring. There is no evidence that black and Latino police executives have been a force for moderation under either Commissioners Kelly or Bratton. Top cops like Phil Banks and Rafael Pineiro oversaw a massive expansion of stop-and-frisk under Kelly and fully embraced the over-policing of communities of color as the primary strategy for crime reduction.

Everyone likes the idea of a neighborhood police officer who knows and respects the community and can tell who the good guys and the bad guys are. Unfortunately, this is a mythic understanding of the history and nature of urban policing. What distinguishes the police from other city agencies is the legal authorization to use force. Their primary tools of problem solving are arrest and coercion.

While we need police to follow the law and be restrained in their use of force, we cannot expect them to be significantly more friendly given their current role in society. The reality is that when given the task of enforcing a war on drugs, stamping out quality-of-life violations and engaging in “broken windows” policing, their interactions with the public in high crime and disorder areas is going to be at best gruff and distant and at worst hostile and abusive. When their basic job is to criminalize all disorderly behavior, the public will resist them and view their efforts as intrusive and illegitimate, and the police will react to this resistance with defensiveness and increased assertiveness. Community policing is not possible under these conditions.

Training of police officers is notoriously inadequate and at times laughable. Officers are subjected to paramilitary drilling and discipline, lectured on paperwork and legal procedure, taught how to drive and shoot a gun, and then let loose on the public, where their colleagues quickly tell them to forget everything they learned in the academy. So, yes, training improvements are needed, but their effect on communities of color are unlikely to be significantly beneficial.

While inadequate training and supervision may have played a role in some recent high-profile incidents, the fact remains that the massive criminalization of communities of color is being carried out using “proper procedures.” The tens of thousands of arrests for low-level drug possession, trespassing, jumping subway turnstiles and dozens of other “broken window” offenses are generally carried out consistent with police policy, if not strict legal standards. Eric Garner may have been killed by improper arrest procedures and use of force, but he was also killed because the police were following orders to arrest people for selling loose cigarettes.

Even more radical strategies like calling for community control of the police have serious drawbacks. There are two main problems. The first is that communities are not well suited for this task. Most people have very little interest or expertise in undertaking the role of managing a complex city service. In addition, no matter what it might say on paper, community power is typically no match for the entrenched bureaucratic power of the police. Numerous studies show that even when the community is supposed to be given a role in directing police services, the police quickly come to control the community process. Second, even if communities were to develop the power to direct the police, we might not like the results. Given the highly segregated nature of American cities, enclaves of racialized policing could be expected to emerge, as white communities attempt to wall themselves off from the perceived threats of outsiders. Even in communities of color, local community leaders are not always operating with the best interests of the entire community in mind. Those that tend to populate community institutions tend to be older, more conservative and closely tied to local landlords and businesses. These players are unlikely to be the source of dramatic changes in police policy.

This is a reform that has some potential. But body cameras are only as effective as the accountability mechanisms in place. If local DAs and grand juries are unwilling to act on the evidence, then the courts won’t be an effective tool for accountability, as we have seen in the Garner case and several others. It is possible that cameras will lead to more civil litigation and more internal disciplinary procedures, causing the city to pay out large damages to the Garner family and that one or more of the officers involved may be disciplined or even fired over their actions. Civil judgments can put pressure on departments for change and can even result in settlement agreements that mandate specific changes, as in the stop-and-frisk case. Firings and significant discipline can also alter officer behavior. Finally, the accountability mechanism of last resort is the public. The combination of critical media coverage and protest action can have the effect of shifting public opinion sufficiently or creating a governing crisis that political leaders have to address. This is what happened around stop-and-frisk when the stopping of hundreds of thousands of young men of color was transformed from a policing issue into a civil rights issue.

It is unlikely that criminal prosecution will ever be a significant driver of police reform. There is a fundamental conflict of interest for DAs who must work closely with police and typically rely on their political support for re-election. Also, the legal standards for police use of force are incredibly permissive and give heavy weight to officer perceptions of danger at the time of the incident. We can take steps to strengthen this process. We could take prosecutions out of the hands of local DAs and turn it over to a statewide “Blue Desk.” This office would be responsible for investigating and prosecuting all cases of police misconduct statewide and would ideally develop the expertise and independence necessary for these difficult cases.

What we really need, though, is a major rethink of the police role. A part of the story of over-policing is hundreds of years old and is about slave patrols, Black Codes, and Jim Crow. Another part of the story, however, is more recent. It’s about the war on drugs, the war on crime and “quality of life” and “broken windows” policing. We need to push back on this dramatic expansion of police power and its role in the development of mass incarceration that has radically transformed poor communities of color in profoundly negative ways and is at the heart of the “new Jim Crow.”

For too long, residents in these communities have faced a terrible dilemma. On the one hand, they have suffered the consequences of high crime and disorder. It is their children who are shot and robbed. But they have also had to bear the brunt of aggressive, invasive and humiliating policing that has criminalized huge swaths of the community. There must be an alternative to this.

We have to take steps to dial back our reliance on the police as the primary tool of resolving neighborhood crime and disorder problems. For instance, we have overwhelming evidence that the policing of drugs is a corrosive and counterproductive strategy that has done nothing to reduce the negative impact of drugs on communities. Drugs are a public health problem, not a policing problem. The same approach should be taken for sex work.

Recently Mayor de Blasio announced a new $130 million package to divert people with mental illness from the criminal justice system and to better treat those who are already there. Our nation’s jails and prisons have become massive warehouses for the mentally ill, and this is a welcome development. However, it still rests on a foundation of police intervention. Access to services is still predicated on coming into contact with the police. The tragedy is that police are poorly trained and equipped for this role. They are primarily equipped with the tools of arrest and physical coercion, which can be incredibly counterproductive when dealing with a person in crisis. Instead, we should rely on civilian crisis intervention teams. We also need to develop community-based mental health services that don’t require criminal justice involvement to access. Similar arguments can be made for dealing with homeless people.

Even more serious crime, such as violence committed by youths, may be more receptive to community-based efforts that do not rely on the punitive and coercive power of the police. Across the country community-based organizations in high-crime areas are working with young people to stop the violence using a variety of public health and community empowerment strategies. The overall effectiveness of these strategies is still being evaluated, but we know that they do not come with the many negative collateral consequences of mass criminalization.

Along the same lines, we need to get police out of schools. Numerous studies have shown that criminalizing school children worsens safety in the schools and drives the most needy students onto the streets, where they often become involved in more serious criminality. Enlightened school leaders with adequate resources have shown that they can increase school safety through creative restorative justice programs that involve students in disciplinary procedures and attempt to take home and community conditions into consideration in resolving problems.

Any real agenda for police reform must look not to make the police friendlier and more professional. Instead, it must work to reduce the police role and replace it with empowered communities working to solve their own problems. We don’t need community control of the police. We need community control over services that will create safer and more stable neighborhoods and cities.”

---from the article We Don’t Just Need Nicer Cops. We Need Fewer Cops. by Alex Vitale

#sociology#criminology#criminal justice#police#police brutality#racial bias#racial profiling#racism#united states#criminal justice system#war on drugs#stop and frisk#eric garner#segregation#police reform#broken windows policing#new jim crow#drugs#mental health#mental illness

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why White Americans Call the Police on Black People

“Don’t you fucking walk away! Don’t fucking walk away from me!” the 20-something-year-old woman screamed as she followed after the 20-something-year-old guy who just got out of her car. It was 2 a.m.; only the streetlights were on, but the guy was clearly done with his girlfriend (probably ex-girlfriend at this point) and was just trying to get inside the building.

“You fucking asshole!” she screamed and ran after him, jumping onto his back for the angriest piggyback ride in history. He tussled with her for a bit, managing to slide her off his back with a thud. Then he kept walking to the apartment, cursing at her to leave him alone. This was several years ago—my friend Josh and I were awkwardly watching the whole thing. All we wanted to do was move a few final boxes into my first apartment in Laurel, Md., but this Real Housewives of Potomac cutscene was blocking our path to my second-floor unit.

“I’m gonna call the cops! I’ll tell them you hit me!” the woman screamed, sitting on the grass and pointing at her ex. “I’ll tell them you beat me up. They’ll get your ass.”

The man stopped dead in his tracks, turned around and gave her a look of shock, anger and then unmitigated fear. He was black. She was white. He knew exactly what she was saying and so did I, and most horrendously, so did she. When white people threaten to call the police on black people—out of anger, out of spite, out of pure vindictiveness—they are effectively saying, “I’ll kill you!” They’re just using a legal extension of white supremacy to do it. It’s high time we start considering these bigots just as much a threat as the police they summon to do their bidding.

This week, black America added “sitting at Starbucks waiting for a white friend” to the list of things that we cannot safely do without fear of police violence. Previous entries included sitting in your car, sitting in someone else’s car, standing on your front porch, standing on your back porch, surviving a car accident, asking for directions to school and, of course, breathing.

As a black man in America who has been harassed by police more times than I can count, I wasn’t surprised by the viral Starbucks video at all. However, my anger is directed not just at the cops but also at the cowardly Starbucks manager who made the call to the police to begin with. The men and women making these outrageous and unwarranted calls to police, which result in the harassment, unfair prosecution and even death of people of color, need to be found, publicly shamed and prosecuted to the full extent that the law allows.

No, I’m not talking about Dave Reiling, the man who reported an actual crimein Sacramento, Calif., that the police used as an excuse to shoot Stephon Clark in his own backyard. Calling the police to report an actual crime that the police overact to is not the citizen’s fault, no matter what color he or she is. I’m talking about the hundreds of cases—that we know about—every year, where white Americans actively and knowingly use the police as an extension of their personal bigotry yet face no consequences.

I’m talking about the white woman at the Red Roof Inn outside of Pittsburgh who called the cops on me because I disputed the charges on my bill and asked to speak to a manager. I’m talking about the white woman who called the cops on me last year even though she knew I was walking with political canvassers for Jon Ossoff’s congressional campaign in North Atlanta. I’m talking about the police officer who followed me behind my house in Hiram, Ohio, asking where I lived because he’d “gotten some calls about robberies.”

In each and every single one of these instances, a white person used the cops as his or her personal racism valets, and I was the one getting served. In each of these instances, I could have been arrested, beaten up or worse based on nothing more than the word of a white person whom I made uncomfortable. As sick as this all is, I still consider myself lucky.

Tamir Rice was killed at the tender age of 12 because a man who admitted to spending the afternoon drinking called 911 to report a “juvenile” who was probably carrying a “fake” gun. Constance Hollinger, the 911 dispatcher, who failed to deliver that information to the cops, got an eight-day suspension but kept her job, and there was no investigation into the caller. Tamir is still dead.

Then there’s Ronald T. Ritchie, who told 911 that John Crawford III was running around Walmart “menacing children” with a shotgun. Crawford, holding a BB gun—sold at Walmart—in the open carry state of Ohio, was shot and killed by police. Despite clear evidence that Ritchie lied to the 911 dispatcher, which is a crime, no charges were filed against him.

You can get arrested for pulling a fire alarm, making fake bomb threats and making false claims of an alien invasion—why not a false police report that results in death? We should be pushing for prosecution against these callers just as much as the cops who pull the trigger.

That’s why I knew Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson’s statement on the Philadelphia incident was trash: “Our store manager never intended for these men to be arrested and this should never have escalated the way it did ... ”

Either Johnson is lying or hasn’t been white in America as long as I’ve been black in America. Calling the police is the epitome of escalation, and calling the police on black people for noncrimes is a step away from asking for a tax-funded beatdown, if not an execution. That Starbucks manager didn’t call the police in hopes that they’d politely ask two black customers to buy a latte or leave, just as the angry woman in front of my apartment wasn’t threatening to call the cops just to get her boyfriend to listen to her. The intent of these actions is to remind black people that the ultimate consequence of discomforting white people—let alone angering them—could be death.

As horrible as the realities of American policing can be for black America, we can’t ever forget that there are even worse people out there. They’re peering out from the curtains of their house, information kiosks and “liberal” coffee counters, surreptitiously dialing their phones, whispering the exaggerations and Trumped-up fears that make America’s violent policing possible.”

---from the article From Starbucks to Hashtags: We Need to Talk About Why White Americans Call the Police on Black People by Jason Johnson

#sociology#police#police brutality#racism#racial prejudice#prejudice#united states#black americans#african americans#white americans#white women#white supremacy#criminal justice#criminology

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Questioning the effectiveness of drug sniffing police dogs

“For young people who attend music festivals, the sight of drug-detection dogs patrolling entrances is a familiar one. But how effective are they in minimising harm, given music festivals in Australia were recently marred by two more deaths by overdose and multiple hospitalisations?

These dogs don’t stop most drug use. And they have been shown to encourage more dangerous practices, criminalise and traumatise marginalised groups, and render all as potential suspects.

In New South Wales, where police also deploy the dogs in bars and clubs, at train stations and on the streets, Labor and Greens MPs have called for the dogs to be banned. A bill to repeal their use is currently before parliament. In Victoria, a parliamentary inquiry is underway to determine whether the dog operations should continue.

Police agencies, however, have defended the dogs, claiming they send an important message to the community that drugs are dangerous and won’t be tolerated.

Such claims overplay the deterrent capacity of the dog programs. They also ignore the negative impacts the dogs have on drug users, marginalised groups and society more broadly.

Unlike “specific” drug-detection work, where dogs assist police to locate drugs on a property following a court-issued search warrant, “general” detection work is where dogs are used in public or institutional settings to home in on people who might be carrying drugs.

In the latter circumstances, a positive dog “alert” is used to constitute, or supplement, the reasonable suspicion necessary to conduct a search.

The use of a dog in these contexts no doubt helps police to increase the odds, compared to a random stop, that someone they search will be carrying drugs. However, these benefits are substantially offset by:

most people found with drugs carrying only small quantities for personal use, rather than traffickable amounts;

most who are carrying drugs not being identified by the dogs; and

the vast majority of those who are identified by the dogs (60-80%) not being found to be carrying any drugs.

False positives may – as police claim – be caused by odour from previous contact with drugs, or drugs that have been stashed in an unsearched internal cavity.

But the dogs can also be affected by the context; they can become tired, hungry, or confused by multiple odours, noises and distractions.

And it is very likely that intentional and unintentional cues by dog handlers, who are trained to profile people based on behaviour, appearance and comportment, are to some degree interfering with the dogs’ identifications.

Dogs are naturally responsive to even the subtlest of human cues. Scent-detection dogs were found to be more likely to falsely alert to locations when their handler believed drugs to be present, with handler beliefs influencing dog alerts even more than food decoys.

In my own observational research, I have documented plain-clothed police at two different festival entrances directing dog handlers to specific persons of interest. Such practices, along with other less explicit biases and cues, may have impacts on alert accuracy.

Such cues may also be exacerbating the discriminatory impacts of general drug-detection dogs. The locations chosen for deployment are having disproportionate effects on certain marginalised groups, such as LGBTI+ people, Aboriginal communities, poorer populations and young people. And potential biases in the cues being given might be compounding these effects.

The dogs’ high false-positive rate in public contexts also has implications for their legality. Australian courts are yet to test whether a 20-40% accuracy is enough to constitute the reasonable suspicion necessary for a search.

In the meantime, police agencies tend to cautiously advise their personnel that a positive dog alert can only be used to form part of that suspicion, without specifying what other grounds can be used to make up the rest.

With more than 15,000 people searched based on drug-dog alerts each year since 2009 in NSW alone, it is not surprising that serious concerns about civil liberties and police-community relations are being raised.

The experience of being searched by police with detection dogs can perhaps be likened to being scanned at an airport, or having your bag searched in a store. Even in the absence of wrongdoing, searches produce a sense of oneself as suspect. It is a feeling no doubt compounded for those whose marginalised identities render them already unduly suspect.

Almost all of those I have interviewed who have been searched, whether carrying drugs or not, experienced some form of embodied emotional trauma, such as anxiety, humiliation, anger, frustration and shame. Others have reported similar experiences of violation and trauma.

Proponents of the drug-dog operations might assume that exposing people to this kind of fear and shame is a good way to deter them from using drugs. Yet fear and shame tend to be very poor motivators of positive behaviour change. Instead, they can have worrying side effectssuch as increased anxiety, reduced health-seeking behaviours, and impacts on broader social relations.

Even highly publicised drug-dog operations tend to be ineffective as a deterrent. Rather than reducing or stopping their drug use in response to drug-dog operations, people have reported taking actions such as:

consuming drugs quickly if dogs are present;

using their drugs in advance;

stashing drugs in internal cavities;

using drugs thought to be less detectable; or

buying drugs inside a venue.

Visible, zero-tolerance-style drug policing has a negative impact on drug-user health outcomes. Drug-detection-dog operations are no different.

When drug users are shaping their drug-use behaviours in order to best avoid police dogs problems inevitably arise, including heightened risk of overdose death. At least two deaths have been directly associated with panicked ingestion after seeing drug dogs.

The negative impacts of drug detection dog use far outweigh any benefits associated with the confiscation of generally small amounts of drugs from a small proportion of drug users. Police services should look at ending these operations now.”

---from the article Why drug-detection dogs are sniffing up the wrong tree by Peta Malins

#sociology#criminal justice#criminology#police#police dogs#prejudice#racial prejudice#bias#lgbt#aboriginal#working class#drugs#drug use#australia

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saving Jewish Children, but at What Cost?

01/09/05

“In October 1946, just a year after the defeat of the Nazis, the Vatican weighed in on one of the most painful episodes of the postwar era: the refusal to allow Jewish children who had been sheltered by Catholics during the war to return to their own families and communities.

A newly disclosed directive on the this subject provides written confirmation of well-known church policy and practices at the time, particularly toward Jewish children who had been baptized, often to save them from perishing at the hands of the Nazis. Its tone is cold and impersonal, and it makes no mention of the horrors of the Holocaust.

Its disclosure has reopened a raw debate on the World War II role of the Catholic Church and of Pope Pius XII, a candidate for sainthood who has been excoriated by his critics as a heartless anti-Semite who maintained a public silence on the Nazi death camps and praised by his supporters as a savior of Jewish lives.

The one-page, typewritten directive, dated Oct. 23, 1946, was discovered in a French church archive outside Paris and made available to The New York Times on the condition that the source would not be disclosed. It is a list of instructions for French authorities on how to deal with demands from Jewish officials who want to reclaim Jewish children.

"Children who have been baptized must not be entrusted to institutions that would not be in a position to guarantee their Christian upbringing," the directive says.

Continue reading the main story

It also contains an order not to allow Jewish children who had been baptized Catholic to go home to their own parents. "If the children have been turned over by their parents, and if the parents reclaim them now, providing that the children have not received baptism, they can be given back," it says.

Even Jewish orphans who had not been baptized Catholic were not to be turned over automatically to Jewish authorities. "For children who no longer have their parents, given the fact that the church has responsibility for them, it is not acceptable for them to be abandoned by the church or entrusted to any persons who have no rights over them, at least until they are in a position to choose themselves," the document says. "This, obviously, is for children who would not have been baptized."

The document, written in French and first disclosed last week by the Italian daily newspaper Corriere della Sera, is unsigned but says, "It should be noted that this decision taken by the Holy Congregation of the Holy Office has been approved by the Holy Father."

The publication of the document is likely to embolden those who do not think Pius XII is worthy of becoming a saint. Some prominent Jews and historians have attacked the document for its insensitivity to the Holocaust.

The Rev. Peter Gumpel, a Rome-based Jesuit priest and a leading proponent for the beatification of Pius XII, the first step toward sainthood, said he was convinced that the document did not come from the Vatican. He pointed out that it is not on official Vatican stationery, that it is not signed and that it is written in French, not Italian. "There is something fishy here," he said.

But Étienne Fouilloux, a French historian who is compiling Pope John XXIII's diaries during his years in France, said that the document had been discovered recently in church archives outside of Paris by a serious researcher and that it is genuine. John has been beatified, the last formal step toward sainthood.

At the time, Pope John XXIII was Monsignor Angelo Roncalli, Pope Pius XII'S representative to France. During the war, Monsignor Roncalli was credited with saving tens of thousands of Jews from Nazi persecution by using diplomatic couriers, papal representatives and nuns to issue and deliver baptismal certificates, immigration certificates and visas, many of them forged, to Jews. He also helped gain asylum for Jews in neutral countries.

"This document is indicative of a mind-set at the Vatican that dealt with problems in a legal framework without worrying that there were human beings involved," Mr. Fouilloux said. "It shows that the massacre of Jews was not seen by the Holy See as something of importance."

He said he would include the document in the next volume of the diaries.

The document underscores the sanctity with which the Vatican treated the sacrament of baptism at the time -- no matter how or why it was administered.

The church's stance that a baptized child is irrevocably Christian was established nearly a century before the Holocaust, when, in 1858, papal guards took Edgardo Mortara, 6, from his family in Bologna when word spread that he had been clandestinely baptized by a Catholic maid. It was relaxed only in the 1960's.

More important, the directive captures the church's failure to grasp the enormous implications of the Nazi extermination of the Jews. "It shows the very bureaucratic and very icy attitude of the Catholic Church in these types of things." said Alberto Melloni, an Italian historian with the John XXIII Foundation for Religious Studies in Bologna, who is working with Mr. Fouilloux to publish the diaries of Pope John XXIII. He called the tone of the directive "horrifyingly normal."

A second document that was also discovered by the French researcher is a letter in July 1946 to Monsignor Roncalli that noted his pledge to intervene to return Jewish-born children to their community and asked for his help to return 30 Jewish-born children living in a Catholic charity.

"Almost two years after the liberation of France, some Israelite children are still in non-Jewish institutions that refuse to give them back to Jewish charities," said the letter, which was signed by the Grand Rabbi of France and the head of the Jewish Central Consistory. It added, "We are in advance, grateful for your help."

It is not known whether there was a reply.

No reliable figures exist on how many French Jewish children were saved by the church from the Nazis, or affected by its decision to prevent them from rejoining their families and communities after the war. The French Jewish population had limited success in recovering Jewish children who had been adopted by non-Jews.

In the most well-documented case in France, two Jewish boys, Robert and Gerald Finaly, were sent in 1944 by their parents to a Catholic nursery in Grenoble. The parents perished at Auschwitz. Family members tried to get the boys back in 1945, but in part because they had been baptized, it took an additional eight years and a long legal battle to prevail over the church.

"Look, I know that for the church, baptism means the child belongs to the church, you can't undo it," said Amos Luzzatto, the president of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities. "But given the circumstances they could have made a human decision."

Mr. Luzzatto described himself as "speechless" that the Vatican directive on the children does not mention the Holocaust and questioned the worthiness of Pius XII to be made a saint.

"If they beatify him, don't ask us to applaud," he said.

Some corners of the Catholic Church are suspicious that the document, and the ensuing debate that has played out in Italian newspapers, was produced to create obstacles in Pius XII's march toward sainthood.

But Pope John Paul II strongly supports the campaign to make Pius XII a saint, and in February 2003, the Vatican announced the opening of some secret archives to help clear Pius XII's name, although the papers do not deal with his activities as pope.”

---from the article Saving Jewish Children, but at What Cost? by Elaine Sciolino and Jason Horowitz

#sociology#history#catholic church#Catholocism#jewish#jewish people#judaism#antisemitism#world war II#holocaust#the holocaust#nazism#france

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

45,000 deaths annually linked to lack of health coverage in the U.S.

“Nearly 45,000 annual deaths are associated with lack of health insurance, according to a new study published online today by the American Journal of Public Health. That figure is about two and a half times higher than an estimate from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2002.

The study, conducted at Harvard Medical School and Cambridge Health Alliance, found that uninsured, working-age Americans have a 40 percent higher risk of death than their privately insured counterparts, up from a 25 percent excess death rate found in 1993.

“The uninsured have a higher risk of death when compared to the privately insured, even after taking into account socioeconomics, health behaviors, and baseline health,” said lead author Andrew Wilper, M.D., who currently teaches at the University of Washington School of Medicine. “We doctors have many new ways to prevent deaths from hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease — but only if patients can get into our offices and afford their medications.”

The study, which analyzed data from national surveys carried out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), assessed death rates after taking into account education, income, and many other factors, including smoking, drinking, and obesity. It estimated that lack of health insurance causes 44,789 excess deaths annually.

Previous estimates from the IOM and others had put that figure near 18,000. The methods used in the current study were similar to those employed by the IOM in 2002, which in turn were based on a pioneering 1993 study of health insurance and mortality.

Deaths associated with lack of health insurance now exceed those caused by many common killers such as kidney disease. An increase in the number of uninsured and an eroding medical safety net for the disadvantaged likely explain the substantial increase in the number of deaths, as the uninsured are more likely to go without needed care. Another factor contributing to the widening gap in the risk of death between those who have insurance and those who do not is the improved quality of care for those who can get it.

The researchers analyzed U.S. adults under age 65 who participated in the annual National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) between 1986 and 1994. Respondents first answered detailed questions about their socioeconomic status and health and were then examined by physicians. The CDC tracked study participants to see who died by 2000.

The study found a 40 percent increased risk of death among the uninsured. As expected, death rates were also higher for males (37 percent increase), current or former smokers (102 percent and 42 percent increases), people who said that their health was fair or poor (126 percent increase), and those who examining physicians said were in fair or poor health (222 percent increase).

Steffie Woolhandler, study co-author, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and a primary care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance, noted: “Historically, every other developed nation has achieved universal health care through some form of nonprofit national health insurance. Our failure to do so means that all Americans pay higher health care costs, and 45,000 pay with their lives.”

“The Institute of Medicine, using older studies, estimated that one American dies every 30 minutes from lack of health insurance,” remarked David Himmelstein, study co-author, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and a primary care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance.

“Even this grim figure is an underestimate — now one dies every 12 minutes.”

---from the article New study finds 45,000 deaths annually linked to lack of health coverage by David Cecere

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Men’s-Rights Activism Is the Gateway Drug for the Alt-Right

08/17/17

“Christopher Cantwell has a knack for getting himself noticed. The 36-year-old white supremacist with an internet radio show and a long history of violent rhetoric was one of the most visible figures at this past weekend’s #UniteTheRight rallies in Charlottesville.

The overgrown skinhead managed to thrust himself again and again into the center of the action, caught in one photo circulated on Twitter striking a dramatic pose as he sprayed anti-fascist counterprotesters with mace. He played a starring role in a Vice News mini-documentary on the event, helpfully providing the Vice crew with a never-ending supply of incendiary quotes. “We’re not nonviolent,” he declared at one point during the protests. “We’ll fucking kill these people if we have to.” In a later sit-down interview with Vice he coldly announced that the ISIS-style car attack that left activist Heather Heyer dead was “more than justified … I think a lot more people are going to die before we’re done here, frankly.”

Cantwell has not always been a figurehead of the alt-right. The Long Island native first gained notoriety as a cop-hating libertarian after moving to Keene, New Hampshire, in 2012 to take part in the the Free State Project, a quixotic political movement with the goal of turning the state into a haven for “free people.” He’s affixed various labels to himself over the years as his politics have transmogrified: anarchist, anarcho-capitalist, atheist, asshole. Perhaps the most revealing of his political past selves? Christopher Cantwell, men’s-rights activist.

During 2014 and 2015, Cantwell posted regular men’s-rights screeds to his blog on subjects ranging from Elliot Rodger’s murder spree to the reasons why men and women “are not, cannot, and should not be equals.” In one particularly overwrought post on “rape accusation culture” that was later republished on the then-popular men’s-rights site A Voice for Men, he warned fellow men of the alleged dangers of false accusations from vengeful women.

“No evidence necessary, just point your finger, ladies, and men will go to prison,” he declared. “Just say the word and their reputations and careers will be ruined. Simply bat your eyes at a policeman and he’ll snatch up any ex-boyfriend you feel jilted by.”

Cantwell is hardly the only alt-rightist with a past as a men’s-rights activist. Media gadfly, “sick Hillary” conspiracy theorist, and self-help guru Mike Cernovich was known for his men’s-rights talk before he turned to Trump and the alt-right — though he now claims to have broken with the movement. Canadian YouTube “philosopher” Stefan Molyneux declared himself an MRA long before he became a darling of the alt-right (and he recently conducted an interview with the author of that notorious Google memo, James Damore). Peter Tefft, a young man with a fashy hairdo who was famously disowned by his family after being outed as one of the torch-carrying marchers in Charlottesville, went through a men’s-rights phase before declaring himself a fascist, according to his nephew in an interview with CNN.

There are good reasons why men’s-rights activism has served for so many as a gateway drug to the alt-right: Both movements appeal to men with fantasies of violent, sometimes apocalyptic redemption — and, like Cantwell, a tendency to express these fantasies in bombastic prose. And both movements are based on a bizarro-world ideology in which those with the most power in contemporary society are the true victims of oppression.

In other words, if you can convince yourself that men are the primary victims of sexism, it’s not hard to convince yourself that whites are the primary victims of racism. And it’s similarly easy for members of both movements to see white men as the most oppressed snowflakes of all.

(This is not to say that men alone benefit from a white-supremacist ideology, or that men alone are responsible for the toxic doctrine. Women have a long history of involvement in the KKK and played a critical role in spreading the movement.)

Neo-Nazis rail endlessly about the danger of Western civilization — always defined as inherently white — being overrun with brown and black “savages,” and speak of the need to “physically remove” — that is, exile or simply murder — the nonwhite interlopers. Despite their violent fantasies — which sometimes lead to violent actions, as they did this past weekend — they see themselves as the victims, engaging in violence only to defend themselves and their race from destruction.

The men’s-rights movement indulges in similar fantasies. Several years back, A Voice for Men founder Paul Elam infamously suggested that “Domestic Violence Awareness Month” should be replaced with “Bash a Violent Bitch Month” in which “men who are being attacked and physically abused by women [can] beat the living shit out of them.”

Men’s-rights activists love to imagine apocalyptic scenarios in which this sort of retributive violence plays out on a global scale. In a comment on his own website, Elam warned feminists and other uppity women that “treating half the population, the stronger half at that, with too much continuing disregard is [not] a very good idea. Thinking they will never come out swinging is a stupid, stupid way to go.”

Both MRAs and alt-rightists are so adept at playing the victim that both groups have convinced themselves that they are oppressed by the mere presence of women in “male spaces” (in the case of MRAs) and nonwhite people in “white countries” (in the case of alt-rightists).

MRAs throw a fit whenever they discover women trying to set aside a place of their own — raging against such alleged oppression as women-only gyms — but they insist that their own “male spaces” should remain forever free of lady taint. Alt-rightists similarly rail against what they call “white genocide” — which doesn’t refer to the forcible ethnic cleansing of white people but rather to demographic changes rendering mostly white countries somewhat less white. They’re so acutely sensitive to the slightest hint of “white genocide” that they can be sent into paroxysms of indignation upon catching sight of diaper boxes festooned with pictures of nonwhite babies and ads for sweatpants featuring interracial couples.

The danger of both of these ideologies isn’t just that they’re both based on bizarro-world fantasies that bear little resemblance to reality. It’s also that, with Trump in the White House, they may have a chance to impose some of their bizarro-world logic on the rest of us. Let’s hope that reality prevails.”

---from the article “Men’s-Rights Activism Is the Gateway Drug for the Alt-Right” by David Futrelle

#sociology#mens rights activism#mra#alt-right#alt right#misogyny#sexism#White Supremacy#fascism#terrorism#white men

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incels aren’t really looking for sex. They’re looking for absolute male supremacy.

“Lately I have been thinking about one of the first things that I ever wrote for the Internet: a series of interviews with adult virgins, published by the Hairpin. I knew my first subject personally, and, after I interviewed her, I put out an open call. To my surprise, messages came rolling in. Some of the people I talked to were virgins by choice. Some were not, sometimes for complicated, overlapping reasons: disability, trauma, issues related to appearance, temperament, chance. “Embarrassed doesn’t even cover it,” a thirty-two-year-old woman who chose the pseudonym Bette told me. “Not having erotic capital, not being part of the sexual marketplace . . . that’s a serious thing in our world! I mean, practically everyone has sex, so what’s wrong with me?” A twenty-six-year-old man who was on the autism spectrum and had been molested as a child wondered, “If I get naked with someone, am I going to take to it like a duck to water, or am I going to start crying and lock myself in the bathroom?” He hoped to meet someone who saw life clearly, who was gentle and independent. “Sometimes I think, why would a woman like that ever want me?” he said. But he had worked hard, he told me, to start thinking of himself as a person who was capable of a relationship—a person who was worthy of, and could accept, love.

It is a horrible thing to feel unwanted—invisible, inadequate, ineligible for the things that any person might hope for. It is also entirely possible to process a difficult social position with generosity and grace. None of the people I interviewed believed that they were owed the sex that they wished to have. In America, to be poor, or black, or fat, or trans, or Native, or old, or disabled, or undocumented, among other things, is usually to have become acquainted with unwantedness. Structural power is the best protection against it: a rich straight white man, no matter how unpleasant, will always receive enthusiastic handshakes and good treatment at banking institutions; he will find ways to get laid.

These days, in this country, sex has become a hyper-efficient and deregulated marketplace, and, like any hyper-efficient and deregulated marketplace, it often makes people feel very bad. Our newest sex technologies, such as Tinder and Grindr, are built to carefully match people by looks above all else. Sexual value continues to accrue to abled over disabled, cis over trans, thin over fat, tall over short, white over nonwhite, rich over poor. There is an absurd mismatch in the way that straight men and women are taught to respond to these circumstances. Women are socialized from childhood to blame themselves if they feel undesirable, to believe that they will be unacceptable unless they spend time and money and mental effort being pretty and amenable and appealing to men. Conventional femininity teaches women to be good partners to men as a basic moral requirement: a woman should provide her man a support system, and be an ideal accessory for him, and it is her job to convince him, and the world, that she is good.

Men, like women, blame women if they feel undesirable. And, as women gain the economic and cultural power that allows them to be choosy about their partners, men have generated ideas about self-improvement that are sometimes inextricable from violent rage.

Several distinct cultural changes have created a situation in which many men who hate women do not have the access to women’s bodies that they would have had in an earlier era. The sexual revolution urged women to seek liberation. The self-esteem movement taught women that they were valuable beyond what convention might dictate. The rise of mainstream feminism gave women certainty and company in these convictions. And the Internet-enabled efficiency of today’s sexual marketplace allowed people to find potential sexual partners with a minimum of barriers and restraints. Most American women now grow up understanding that they can and should choose who they want to have sex with.

In the past few years, a subset of straight men calling themselves “incels” have constructed a violent political ideology around the injustice of young, beautiful women refusing to have sex with them. These men often subscribe to notions of white supremacy. They are, by their own judgment, mostly unattractive and socially inept. (They frequently call themselves “subhuman.”) They’re also diabolically misogynistic. “Society has become a place for worship of females and it’s so fucking wrong, they’re not Gods they are just a fucking cum-dumpster,” a typical rant on an incel message board reads. The idea that this misogyny is the real root of their failures with women does not appear to have occurred to them.

The incel ideology has already inspired the murders of at least sixteen people. Elliot Rodger, in 2014, in Isla Vista, California, killed six and injured fourteen in an attempt to instigate a “War on Women” for “depriving me of sex.” (He then killed himself.) Alek Minassian killed ten people and injured sixteen, in Toronto, last month; prior to doing so, he wrote, on Facebook, “The Incel Rebellion has already begun!” You might also include Christopher Harper-Mercer, who killed nine people, in 2015, and left behind a manifesto that praised Rodger and lamented his own virginity.

The label that Minassian and others have adopted has entered the mainstream, and it is now being widely misinterpreted. Incel stands for “involuntarily celibate,” but there are many people who would like to have sex and do not. (The term was coined by a queer Canadian woman, in the nineties.) Incels aren’t really looking for sex; they’re looking for absolute male supremacy. Sex, defined to them as dominion over female bodies, is just their preferred sort of proof.

If what incels wanted was sex, they might, for instance, value sex workers and wish to legalize sex work. But incels, being violent misogynists, often express extreme disgust at the idea of “whores.” Incels tend to direct hatred at things they think they desire; they are obsessed with female beauty but despise makeup as a form of fraud. Incel culture advises men to “looksmaxx” or “statusmaxx”—to improve their appearance, to make more money—in a way that presumes that women are not potential partners or worthy objects of possible affection but inconveniently sentient bodies that must be claimed through cold strategy. (They assume that men who treat women more respectfully are “white-knighting,” putting on a mockable façade of chivalry.) When these tactics fail, as they are bound to do, the rage intensifies. Incels dream of beheading the sluts who wear short shorts but don’t want to be groped by strangers; they draw up elaborate scenarios in which women are auctioned off at age eighteen to the highest bidder; they call Elliot Rodger their Lord and Savior and feminists the female K.K.K. “Women are the ultimate cause of our suffering,” one poster on incels.me wrote recently. “They are the ones who have UNJUSTLY made our lives a living hell… We need to focus more on our hatred of women. Hatred is power.”

On a recent ninety-degree day in New York City, I went for a walk and thought about how my life would look through incel eyes. I’m twenty-nine, so I’m a little old and used up: incels fetishize teen-agers and virgins (they use the abbreviation “JBs,” for jailbait), and they describe women who have sought pleasure in their sex lives as “whores” riding a “cock carousel.” I’m a feminist, which is disgusting to them. (“It is obvious that women are inferior, that is why men have always been in control of women.”) I was wearing a crop top and shorts, the sort of outfit that they believe causes men to rape women. (“Now watch as the level of rapes mysteriously rise up.”) In the elaborate incel taxonomy of participants in the sexual marketplace, I am a Becky, devoting my attentions to a Chad. I’m probably a “roastie,” too—another term they use for women with sexual experience, denoting labia that have turned into roast beef from overuse.

Earlier this month, Ross Douthat, in a column for the Times, wrote that society would soon enough “address the unhappiness of incels, be they angry and dangerous or simply depressed or despairing.” The column was ostensibly about the idea of sexual redistribution: if power is distributed unequally in society, and sex tends to follow those lines of power, how and what could we change to create a more equal world? Douthat noted a recent blog post by the economist Robin Hanson, who suggested, after Minassian’s mass murder, that the incel plight was legitimate, and that redistributing sex could be as worthy a cause as redistributing wealth. (The quality of Hanson’s thought here may be suggested by his need to clarify, in an addendum, “Rape and slavery are far from the only possible levers!”) Douthat drew a straight line between Hanson’s piece and one by Amia Srinivasan, in the London Review of Books. Srinivasan began with Elliot Rodger, then explored the tension between a sexual ideology built on free choice and personal preference and the forms of oppression that manifest in these preferences. The question, she wrote, “is how to dwell in the ambivalent place where we acknowledge that no one is obligated to desire anyone else, that no one has a right to be desired, but also that who is desired and who isn’t is a political question.”

Srinivasan’s rigorous essay and Hanson’s flippantly dehumanizing thought experiment had little in common. And incels, in any case, are not actually interested in sexual redistribution; they don’t want sex to be distributed to anyone other than themselves. They don’t care about the sexual marginalization of trans people, or women who fall outside the boundaries of conventional attractiveness. (“Nothing with a pussy can be incel, ever. Someone will be desperate enough to fuck it . . . Men are lining up to fuck pigs, hippos, and ogres.”) What incels want is extremely limited and specific: they want unattractive, uncouth, and unpleasant misogynists to be able to have sex on demand with young, beautiful women. They believe that this is a natural right.

It is men, not women, who have shaped the contours of the incel predicament. It is male power, not female power, that has chained all of human society to the idea that women are decorative sexual objects, and that male worth is measured by how good-looking a woman they acquire. Women—and, specifically, feminists—are the architects of the body-positivity movement, the ones who have pushed for an expansive redefinition of what we consider attractive. “Feminism, far from being Rodger’s enemy,” Srinivasan wrote, “may well be the primary force resisting the very system that made him feel—as a short, clumsy, effeminate, interracial boy—inadequate.” Women, and L.G.B.T.Q. people, are the activists trying to make sex work legal and safe, to establish alternative arrangements of power and exchange in the sexual market.

We can’t redistribute women’s bodies as if they are a natural resource; they are the bodies we live in. We can redistribute the value we apportion to one another—something that the incels demand from others but refuse to do themselves. I still think about Bette telling me, in 2013, how being lonely can make your brain feel like it’s under attack. Over the past week, I have read the incel boards looking for, and occasionally finding, proof of humanity, amid detailed fantasies of rape and murder and musings about what it would be like to assault one’s sister out of desperation. In spite of everything, women are still more willing to look for humanity in the incels than they are in us.”

---from the article The Rage of the Incels by Jia Tolentino

#sociology#incel#incels#misogyny#sexism#feminism#male supremacy#men#women#sex#sexual revolution#white supremacy#terrorism

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Instances of the United States overthrowing, or attempting to overthrow, a foreign government since the Second World War

from Overthrowing other people’s governments: The Master List by William Blum

“China 1949 to early 1960s

Albania 1949-53

East Germany 1950s

Iran 1953 *

Guatemala 1954 *

Costa Rica mid-1950s

Syria 1956-7

Egypt 1957

Indonesia 1957-8

British Guiana 1953-64 *

Iraq 1963 *

North Vietnam 1945-73

Cambodia 1955-70 *

Laos 1958 *, 1959 *, 1960 *

Ecuador 1960-63 *

Congo 1960 *

France 1965

Brazil 1962-64 *

Dominican Republic 1963 *

Cuba 1959 to present

Bolivia 1964 *

Indonesia 1965 *

Ghana 1966 *

Chile 1964-73 *

Greece 1967 *

Costa Rica 1970-71

Bolivia 1971 *

Australia 1973-75 *

Angola 1975, 1980s

Zaire 1975

Portugal 1974-76 *

Jamaica 1976-80 *

Seychelles 1979-81

Chad 1981-82 *

Grenada 1983 *

South Yemen 1982-84

Suriname 1982-84

Fiji 1987 *

Libya 1980s

Nicaragua 1981-90 *

Panama 1989 *

Bulgaria 1990 *

Albania 1991 *

Iraq 1991

Afghanistan 1980s *

Somalia 1993

Yugoslavia 1999-2000 *

Ecuador 2000 *

Afghanistan 2001 *

Venezuela 2002 *

Iraq 2003 *

Haiti 2004 *

Somalia 2007 to present

Honduras 2009 *

Libya 2011 *

Syria 2012

Ukraine 2014 *”

#united states#sociology#history#imperialism#us imperialism#china#albania#germany#iran#guatemala#costa rica#syria#egypt#indonesia#british guiana#iraq#vietnam#cambodia#laos#ecuador#congo#france#brazil#dominican republic#cuba#bolivia#ghana#chile#greece#australia

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

US War Crimes in Vietnam

“Massacres of civilians by U.S. forces in Vietnam were not rare aberrations but everyday occurrences, an authoritative new book on the subject charges.

Worse, the massacres were a result of deliberate Pentagon policies handed down from the very top, often to build false “body count” figures that could lead an officer to promotion. The inflated body counts reported civilian dead as combatant Viet Cong when they were actually women, children and old men.

The massacre of more than 500 civilians at My Lai on March 15, 1968, by the Americal division’s Charlie company, 1st battalion, 20th infantry, has long been portrayed as a solitary episode ordered by Lieutenant William Calley. He was the only one of 28 officers involved who was convicted and although sentenced to life imprisonment was paroled after just 40 months.

Yet episodes of such barbarism “were virtually a daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam,” writes Nick Turse in his new book, “Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam”(Metropolitan Books). Turse is a fellow at The Nation Institute whose investigations of U.S. war crimes in Vietnam have gained him a Ridenhour Prize for Reportorial Distinction and a fellowship at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. He writes that he spoke with more than 100 American veterans across the country “both those who had witnessed atrocities and others who had personally committed terrible acts.”

Turse reports the Pentagon has gone to great lengths to cover up the true record of U.S. atrocities in Vietnam: “Indeed an astonishing number of Marine court-martial records of the era have apparently been destroyed or gone missing. Most Air Force and Navy criminal investigation files that may have existed seem to have met the same fate.”

“The stunning scale of civilian suffering in Vietnam is far beyond anything that can be explained as merely the work of some ‘bad apples,’ however numerous,” writes Turse. “Murder, torture, rape, abuse, forced displacement, home burnings, specious arrests, imprisonment without due process---such occurrences were a virtually daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam...they were the inevitable outcome of deliberate policies, dictated at the highest levels of the military.”

In researching his book, Turse said some of the veterans he tried to contact wanted nothing to do with his questions and would slam down their phone receiver. “But most were willing to speak to me, and many even seemed glad to talk to someone who had a sense of the true nature of the war,” he added.

Some veterans told Turse of operation Speedy Express where civilians from Dec., 1968, through May, 1969, were systematically slaughtered in huge numbers by U.S. 9th Division troops in the Mekong Delta, “month after month, hamlet after hamlet.” As one veteran told Turse, “A Cobra (helicopter) gunship spitting out 600 rounds a minute doesn’t discern between chickens, kids, and VC.”

“Trigger-happy Americans hovering in their gunships weren’t the only threat to Vietnamese civilians during Speedy Express,” Turse writes. The military ordered almost 6,500 tactical air strikes, dropping at least 5,078 tons of bombs and 1,784 tons of napalm. “It was the epitome of immorality,” said Air Force Captain Brian Willson, who made bomb-damage assessments in so-called “free-fire” zones in the region. “One of the times I counted bodies after an air strike---which always ended with two napalm bombs which would just fry everything that was left---I counted 62 bodies...women between 15 and 25 and so many children---usually in their mothers’ arms or very close to them---and so many old people.” When Willson later read the official report of the dead, he said it listed them as 130 VC killed.”

Turse says, “The jellied incendiary napalm, (used in Vietnam) engineered to stick to clothes and skin, had been modified to blaze hotter and longer than its World War II-era variant. An estimated 400,000 tons of it were dropped in Southeast Asia, killing most of those unfortunate enough to be splashed with it. Thirty-five percent of the victims died within 15 to 20 minutes, according to one study. Another found that 62 percent died before their wounds healed. For those not asphyxiated or consumed by fire, the result could be a living death.”

Gang rapes, quite apart from the rapes reported at My Lai, also “were a horrifyingly common occurrence,” Turse continued. One army report detailed the allegations of a Vietnamese woman who said she was detained by troops from the 173rd Airborne brigade and then raped by 10 soldiers. In another incident, 11 members of the 23rd Infantry division raped a Vietnamese girl, and in another incident, an Americal GI recalled seeing a Vietnamese woman hardly able to walk after being gang-raped by 13 soldiers. These assaults were anything but isolated. One 198th Light Infantry brigade testified he knew of 10 to 15 incidents within a 7-month span in which soldiers from his unit raped young girls. Another GI told of his buddies raping women every couple of days.

Turse writes that he found atrocities were committed by members of “every infantry, cavalry, and airborne division...by every major army unit in Vietnam.” In Chapter Four of his book, Turse lists “A Litany of Atrocities,” some on a scale comparable to My Lai, some of them involving fewer civilians, but all of them war crimes. Selected here are just few the villages Turse cited that were subjected to U.S. attack:

Chan Son: Attacked Aug. 2, 1965, with 1,000 shells, followed by invasion of U.S. Marines, one of whom shouted, “Kill them. I don’t want anyone moving.” U.S. sources said 25 civilians were killed; the National Liberation Front reported more than 100.

Phu Nhuan: On June 4, 1967, American troops killed scores of civilians, including one woman roped to an armored vehicle and dragged around the hamlet.

Thy Thi Ly: U.S. troops opened fire on the villagers in their homes, killing 52, wounding 13, most of the dead were children, elderly men, and women.

Phi Phu: In 1967, U.S. troops killed 32 women and children, including the massacre of 20 non-combatants who were forced into a trench and blown up.

Dien Nien: On Oct. 19, 1966, U.S. and Korean troops massacred 112 civilians, some of the wounded drowned in nearby rice paddies by the boots of pursuing soldiers pressing their faces into the water.

Nhon Hoa: U.S. troops and their Korean allies on March 22, 1967, herded together, and killed, 86 villagers, plus 18 more at a nearby site.

My Khe: At a hamlet near My Lai and about the same time, 155 civilians were killed by men from Bravo company, 4th Battalion, 3rd infantry, which one soldier described “was like being in a shooting gallery.”

Accounts of the torture of Vietnamese civilians and military captured by the U.S. are too numerous to cite in this essay, except to note that in 1971 an Army investigation concluded that violations of the Geneva Convention were “widespread” and that torture by U.S. troops was “standard practice,” Turse reports. A Pentagon task force, however, called war crimes allegations against General William Wesmoreland “unfounded,” explaining that while isolated criminal acts may have occurred “they were neither widespread nor extensive enough to render him criminally responsible for their commission.”

Terming this a brazen rewriting of history, Turse says Westmoreland was never judged by the policies associated with his tenure, namely: “search-and-destroy operations, free-fire zones, and the ‘application of massive firepower.’”

In “Kill Anything That Moves,” Turse has given the public a factual, if distressing, picture of the real Vietnam war, with all the barbarian brutality inflicted by U.S. forces so reminiscent of Nazi atrocities during World War II. It should be made compulsory reading in every high school classroom, particularly in those regions or places where the arrogant philosophy exists that the U.S. has some divine right to refer to this as “the American Century” on grounds that Americans have somehow earned the right to lead the world. It should be remembered that two million Vietnamese civilians didn’t die by accident.”

from the article US War Crimes in Vietnam by Sherwood Ross

#sociology#history#kill anything that moves#vietnam war#united states#war#vietnam#military#united states military#war crimes#my lai#My Lai Massacre#united states war crimes#asia#rape#gang rape

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Report: The Number of Anti-LGBTQ Homicides Nearly Doubled in 2017

1/23/17

“On Monday, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs released its annual report, which documented an alarming spike in hate-related homicides against LGBTQ individuals over the last year.

According to the report, anti-LGBTQ homicides in the United States rose 86 percent in 2017, compared to the previous year. The report found 52 instances of anti-LGBTQ homicides in 2017, and 28 in 2016, but this count does not include the Pulse Nightclub shooting that killed 49 people in 2016, as it only calculates single-incident homicides.

Here are some more of the study’s key findings, as reported by HuffPo.

“67 percent of the victims were age 35 and under.

59 percent of the victims were killed with guns.

45 percent of the homicides of queer, bi or gay cisgender men were related to hookup violence, typically related to ads placed on personal websites and apps.”

In addition, the overwhelming majority—71 percent—of victims were people of color, and 60 percent of the victims were black.

Beverly Tillery, NCAVP’s executive director, told HuffPo that they will be releasing a second report later in the year that covers all incidents of hate-based violence, and that it already appears those numbers are rising, too.

Tillery also told HuffPo, “I don’t know whether all this is based on Trump’s beliefs or not, but at this point, it feels hard to imagine not.

Read the full report here.”

from the article Report: The Number of Anti-LGBTQ Homicides Nearly Doubled in 2017 by Hannah Gold

#sociology#criminology#lgbt#lgbtq#violence#murder#hate crimes#black americans#black women#people of color#united states#gay americans#gay#bisexual

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obese patients receive worse care solely based on their weight

”You must lose weight, a doctor told Sarah Bramblette, advising a 1,200-calorie-a-day diet. But Ms. Bramblette had a basic question: How much do I weigh?

The doctor’s scale went up to 350 pounds, and she was heavier than that. If she did not know the number, how would she know if the diet was working?

The doctor had no answer. So Ms. Bramblette, 39, who lived in Ohio at the time, resorted to a solution that made her burn with shame. She drove to a nearby junkyard that had a scale that could weigh her. She was 502 pounds.

One in three Americans is obese, a rate that has been steadily growing for more than two decades, but the health care system — in its attitudes, equipment and common practices — is ill prepared, and its practitioners are often unwilling, to treat the rising population of fat patients.

Continue reading the main story

The difficulties range from scales and scanners, like M.R.I. machines that are not built big enough for very heavy people, to surgeons who categorically refuse to give knee or hip replacements to the obese, to drug doses that have not been calibrated for obese patients. The situation is particularly thorny for the more than 15 million Americans who have extreme obesity — a body mass index of 40 or higher — and face a wide range of health concerns.

Part of the problem, both patients and doctors say, is a reluctance to look beyond a fat person’s weight. Patty Nece, 58, of Alexandria, Va., went to an orthopedist because her hip was aching. She had lost nearly 70 pounds and, although she still had a way to go, was feeling good about herself. Until she saw the doctor.

“He came to the door of the exam room, and I started to tell him my symptoms,” Ms. Nece said. “He said: ‘Let me cut to the chase. You need to lose weight.’”

The doctor, she said, never examined her. But he made a diagnosis, “obesity pain,” and relayed it to her internist. In fact, she later learned, she had progressive scoliosis, a condition not caused by obesity.

Dr. Louis J. Aronne, an obesity specialist at Weill Cornell Medicine, helped found the American Board of Obesity Medicine to address this sort of issue. The goal is to help doctors learn how to treat obesity and serve as a resource for patients seeking doctors who can look past their weight when they have a medical problem.

Dr. Aronne says patients recount stories like Ms. Nece’s to him all the time.

“Our patients say: ‘Nobody has ever treated me like I have a serious problem. They blow it off and tell me to go to Weight Watchers,’” Dr. Aronne said.

“Physicians need better education, and they need a different attitude toward people who have obesity,” he said. “They need to recognize that this is a disease like diabetes or any other disease they are treating people for.”

The issues facing obese people follow them through the medical system, starting with the physical exam.

Research has shown that doctors may spend less time with obese patients and fail to refer them for diagnostic tests. One study asked 122 primary care doctors affiliated with one of three hospitals within the Texas Medical Center in Houston about their attitudes toward obese patients. The doctors “reported that seeing patients was a greater waste of their time the heavier that they were, that physicians would like their jobs less as their patients increased in size, that heavier patients were viewed to be more annoying, and that physicians felt less patience the heavier the patient was,” the researchers wrote.

Other times, doctors may be unwittingly influenced by unfounded assumptions, attributing symptoms like shortness of breath to the person’s weight without investigating other likely causes.

That happened to a patient who eventually went to see Dr. Scott Kahan, an obesity specialist at Georgetown University. The patient, a 46-year-old woman, suddenly found it almost impossible to walk from her bedroom to her kitchen. Those few steps left her gasping for breath. Frightened, she went to a local urgent care center, where the doctor said she had a lot of weight pressing on her lungs. The only thing wrong with her, the doctor said, was that she was fat.

“I started to cry,” said the woman, who asked not to be named to protect her privacy. “I said: ‘I don’t have a sudden weight pressing on my lungs. I’m really scared. I’m not able to breathe.’”

“That’s the problem with obesity,” she said the doctor told her. “Have you ever considered going on a diet?”

It turned out that the woman had several small blood clots in her lungs, a life-threatening condition, Dr. Kahan said.

For many, the next step in a diagnosis involves a scan, like a CT or M.R.I. But many extremely heavy people cannot fit in the scanners, which, depending on the model, typically have weight limits of 350 to 450 pounds.

Scanners that can handle very heavy people are manufactured, but one national survey found that at least 90 percent of emergency rooms did not have them. Even four in five community hospitals that were deemed bariatric surgery centers of excellence lacked scanners that could handle very heavy people. Yet CT or M.R.I. imaging is needed to evaluate patients with a variety of ailments, including trauma, acute abdominal pain, lung blood clots and strokes.

When an obese patient cannot fit in a scanner, doctors may just give up. Some use X-rays to scan, hoping for the best. Others resort to more extreme measures. Dr. Kahan said another doctor had sent one of his patients to a zoo for a scan. She was so humiliated that she declined requests for an interview.

Problems do not end with a diagnosis. With treatments, uncertainties continue to abound.

In cancer, for example, obese patients tend to have worse outcomes and a higher risk of death — a difference that holds for every type of cancer.

The disease of obesity might exacerbate cancer, said Dr. Clifford Hudis, the chief executive officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.