#does disability? do we Need to pathologize the human condition?

Text

sometimes someone seems autistic and they're literally. just Asian. western medicine does this.

#signs#disorder#stick out#this is a critique#btw#like does neurodivergence need to necessarily be pathologized?#does disability? do we Need to pathologize the human condition?#idk maybe#we can def do smn Better tho....that facilitates more understanding and not just... separation (at best)#anyway thinking ab this lately just cause like.#so when i really figured my shit out in undergrad. i realized i want to go into health and healing#but i wanted a huamnistic perspective and not a pathologizing one#bottom-up so to speak. to appreciate the variety of humanity and alleviate suffering within that framework#so i went into communicationd with concentration in culture and disability#and in this specific instance some of autism (truly i don't think they are Symptoms bc they do not...#like. these traits are not inherent to the condition we just often display them but theyre secondary#they dont describe the core of the condition (which is just a particular neurosystem--everything else is secondary)#but is inherently smn culturally abnormal (theoretically harmful or at least disruptive)#common autistic behaviours like avoiding eye contact; low affect; high or low volume; reservedness#these are Common Traits of Asian cultures! (#obviously Most of the world is Asian so there is CONSIDERABLE variation. but the pt being that these are only abnormal from a WESTERN pov#(also I'm in the United States so i am in particular thinking about Asian Americans but this also applies to like intl interaction)#(like... idk a tiktoker from Hong Kong that ppl think is Autistic who may be allistic)#(also I'm not tryna say only westerners/usa be autistic and Asians can't LMAO)#(its a Human neurotype. just the things that depend on what is circumstantially normative)#anyway.......... hello to the 3 ppl who will see this#actually autistic#mine#critical cultural studies#coms

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Conversation About Demedicalization and Disorders

Let's talk about demedicalization. What is demedicalization? The Open Education Sociology Dictionary defines demedicalization as "The process by which a behavior or condition, once labeled 'sick', becomes defined as natural or normal." It is the process of normalizing a trait of the body or brain or behavior as a normal variance of human existence, rather than a pathological variance in need of treatment or correction.

Put simply, it is no longer looking at something as a sickness in need of treatment, but rather just another way of existing.

Some background info that is needed: the social and medical models of disability.

The medical model posits that the existence of disability is predicated on inherent pathological differences in the bodymind, that it is active physical limitations, some of which can be treated or "corrected", that make a person disabled.

The social model, on the other hand, states that is is a societal lack of access and accommodations that disables a person, and that a person would no longer be functionally disabled were these access barriers to be removed. Keep in mind that this does not mean they believe that people would not still have "impairments" that affect how they are able to function, but that it defines disability as the disadvantages caused by an ableist society treating impairments as needing to be "fixed" rather than accommodated. I defines being abled as being able to participate in society to the full extent an impaired individual wishes to.

I believe in a mixed social-medical model. I believe that some conditions are inherently disabling and that seeking medical treatment for them, while it should be up to disabled individuals, is helpful and good. My ADHD, for example, will still limit my participation in society to the extent I want to, without medication. You could consider medication an accommodation, but there's also the example of my chronic pain and fatigue and POTS that often keeps me housebound or bedbound. There may not be a treatment for that, and I cannot fully participate in the world around me because of that.

"Ultimately, the social model of disability proposes that a disability is only disabling when it prevents someone from doing what they want or need to do."

I am actively prevented from doing what I want or need to do by an inherent feature of my body that no amount of accommodation can allow for. However, some of my conditions would not be disabling with proper accommodation - my autism, for example, I don't generally consider disabling because the people and structures around me DO accommodate for it.

So why is demedicalization helpful or necessary, and how is is applied?

Well, three psychological examples: autism, psychosis, and schizophrenia.

Autism is currently, in the DSM, called autism spectrum disorder. However, autism is a neurotype, and many autistic people do not feel that autism inherently causes them distress or dysfunction, and is therefore not disordered. That is why many of us call ourselves autistic people or say we have autism, rather than ASD. There has been a push for years for the diagnosis itself to be changed to not contain the word "disorder", and to allow for informed self-diagnosis.

Informed self-diagnosis is also an important part of demedicalization, especially of neurodivergence. It says "someone doesn't need a doctorate to know themselves and their own experiences well enough to categorize and classify them. Good research and introspection is enough to trust a person to make the call, and labeling oneself as a specific kind of neurodivergence is harmless, even if they later find out they were wrong.

Psychosis is the next example. There is a growing movement that I've talked about before: the pro-delusion movement. Not everybody experiences distressing delusions, and even when they are distressing, this movement says that only the individual experiencing them has the right to decide whether they should be encouraged or discouraged. It states that it is a violation of autonomy to nonconsensually reality check (tell someone their delusions are not reality) someone, and that as long as a person is not harming others, they can do as they like with their delusions.

This is an example of demedicalization. Treating delusions as something not to be suppressed with medication or ignored or "treated" or "fixed", but as simply another, morally and "healthily neutral" way of existing outside homogenous neurotypical norms.

Finally plurality. Now what's key here is that demedicalization does not mean saying a thing can NEVER be disordered. In fact, that's why I made this post. I saw someone the other day say that they felt their aromantic identity was disordered. Initially, I balked, thinking they were internally arophobic, but I listened to what they had to say. Essentially, they expressed that the identity was never inherently disordered, but that it caused them distress and dysfunction and so they experienced it as such, and crucially, that wasn't a morally bad thing or something they felt they had to correct.

Because here's I think what gets left out of discussions on demedicalization: demedicalization also means no longer treating disorders as something that inherently have to be treated or fixed, that disorders can simply exist as they are if the person with a disorder so chooses; and that anything can be labeled a disorder if it causes distress and dysfunction without being inherently disordered AND without needing to be treated.

And conversely, this means that if you experience something as disordered, demedicalizing it means that you do not have to meet an arbitrary categorical set of requirements to seek treatment, but can do so based on self-reported symptoms. Treatment cannot be gatekept behind a diagnosis that only a "qualified professional" can assign you.

This means if someone wants to, they can label their autism as disordered, but it is never forced on anyone. If someone feels ANY identity - neurodivergent, disabled, queer, alterhuman, paraphilia, whatever - is disordered, they can label it as such, but they also don't have to. There are no requirements to follow through with "treating" anything you label a disorde, either. No strings attached, just the right to self-determination and the right to autonomy hand in hand,

So, back to plurality. You essentially end up with three aspects of demedicalization. You have nondisordered plurality being normalized, you have dissociative disorders that systems can choose not to pursue treatment for without judgment or coercion, and you have disordered systems that can pursue treatment for dissociative symptoms without receiving a difficult-to-access diagnosis. Based on their experiences, they can choose to label themselves as having DID, OSDD, UDD, or related disorders, or to forgo the label and simply seek treatment for whatever distress or dysfunction the disorder is causing.

"But without a specific diagnosis, what if they pursue the wrong treatment and it harms them?"

This is where the importance of recognizing self-reported symptoms as valid comes in. If an OSDD-1b system that hasn't labeled themselves or receives a diagnosis reports that they don't experience amnesia, they won't receive treatment for amnesia.

And since symptoms can mask, if a DID system reports not experiencing amnesia, they simply do not become aware of it or receive treatment for it before they are ready, which is a good thing because recognizing certain symptoms before you are ready to deal with them can be destabilizing and dangerous. More awareness of dissociative disorders will also make it easier for systems to adequately recognize those symptoms, and this isn't saying that someone else can't suggest it to the system experiencing it. It's simply saying the person experiencing a disorder takes the lead and is centered as the most important perspective.

I consider myself to have several disorders and several forms of nondisordered neurodivergence. My BPD is disordered but I am not treating it because I have healthy coping skills already. Same with my schizophrenia. My narcissism, on the other hand, is simply a neurotype. My plurality is both - the plurality itself isn't disordered, but I do have DID on top of it.

A last example, this one physical, of demedicalization: intersex variations. The intersex community has been pushing to recognize that intersex variations are natural variations in human sex, and not medical conditions that need corrected. This doesn't mean that any unpleasant symptoms related to an intersex variation can't ever be treated - in fact, it's important to the community to have that bodily autonomy to access whatever reproductive healthcare is needed - but it does mean treating our sexes as inherently normal and NOT trying to coercively "correct" them.

So in summary, demedicalization is fundamentally about autonomy. It is about considering natural human variations as such, rather than as sickness to be cured, about letting people determine for themselves whether any aspect of themselves is disordered, and the decision on whether or not to pursue treatment for anything being theirs alone. It is about trusting people to be reliable witnesses and narrators of their own subjective internal experiences, and about never forcing anyone to change any aspects of themselves, disordered or not, that aren't harming others. In short, it is about putting power back into the hands of disabled people. And that is what this blog is all about.

#unitypunk#long post#demedicalization#autonomy#social model of disability#medical model#disorders#intersex#self diagnosis

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

FrankensteinWIP - intro

Working title: „Offspring of Unhappy Days”

Genre: adult literary horror

Subgenres: dark academia, queer romance, grounded sci-fi

Themes: academic fraud and ethics, co-dependent relationships, PTSD, fear of death, loneliness, disability/neurodivergency, trans/queer experience in Eastern Europe

Comps: “Leech” by Hiron Ennes, “These Violent Delights” by Micah Nemerever, “Secret History” by Donna Tartt

Protagonist: Kristian Kalina, PhD student, late twenties; trans, queer, autistic; he/him

Short description / pitch:

When two researchers discover a horrifying truth about consciousness and death, their obsessive devotion to each other pushes them to do the unthinkable.

Setting: Kraków, Poland; a fictional institute dealing with several branches of biology situated on the outskirts of the city

Word count: 35k/100k, in drafting stage

First line (after prologue): In our labs, we are small gods, clumsy architects of nature.

Blurb and excerpt under the cut. Reply or reblog with a comment to be added to the tag list!

Blurb:

Kristian is a PhD student at the end of his rope. His scholarship is running out, his supervisor won’t let him defend, and he’s stuck at a third-rate institute with no support. As a last resort, he applies for an assistant position in a newly funded project – and ends up being the only candidate.

A connection quickly develops between him and his new boss, Leith. The two bond over their shared interests, and shared trauma. Soon, the platonic affection transforms into hungry romance. Somewhere deep down, Kristian knows that their love is more of a sick coping mechanism, but is unable to stop himself.

The tension rises when they accidentally discover a gruesome truth about brains, consciousness, and death. Any other scientist would announce this to the world and step away. Kristian and Leith conduct their experiments in secret, pushing the boundaries of ethics to advance the research. And their unquestioning devotion to each other is about to lead them into much darker places.

Excerpt (from chapter 4):

In order to fully assess the effects of a treatment (drug, pollutant, living condition, induced mutation, etc.), a scientist often needs a sample of tissue that has been washed of all unnecessary materials. A clear cut of brain, liver or intestine is best viewed when it has been infused with a fixative before being placed under a microscope. One way to achieve this is transcardial perfusion. I have performed it many times, preparing tissue samples for pathology comparisons. The protocol runs as follows: the animal is anesthetized but kept alive, after which the body is restrained, chest cavity opened, and a major blood vessel is connected to a supply of fixative. The animal’s still beating heart then does the job for you, carrying it to every point, through every capillary, until finally there is no blood left and the heart ceases to beat.

I had never gotten used to it. I am not a squeamish person and the sight of blood, urine, feces, pus, or any other biological substances does not disturb me. Many biology students deal quite well with formaldehyde preserved specimens but falter at freshly sacrificed animals. One young man had described to me the acute drop in blood pressure he felt the first time a dead rat had been placed in front of him. It wasn’t the sight (fluids, viscera, the undigested contents of the rat’s stomach) but the realization of such recent death. The tiny body still warm, motionless. Perhaps the human mind begins searching at once for the causes, and fears the proximity of whatever had killed another animal (and may be searching for its next victim). Regardless, the ability to deal with this horror is what often sorts students into specialties. Luckily, there are plenty of areas in biology that don’t require you come in contact with living vertebrates at all.

What I always wondered is whether it was possible to do transcardial perfusion on a human. Could one take a person, still living, put them under and replace their blood with some sort of protective substance? Perhaps a solution that would allow them to be frozen, preserved in a box like a packet of fish sticks, waiting for a better time. Keep them on the verge between life and death for decades to then defrost them and pump four liters of blood back into their body. Would the brain survive such a process? Would the mind? Could someone do this to me at the shortest notice and keep me asleep until S. would retire (or die) and someone else would be placed on his cases, so that I could graduate at last?

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Society’s interest and responsibility, when it comes to mental health, lie in providing everyone with the ability to access medical care, including psychiatric care, without undue financial hardship

Beyond fighting for this access, society has no business attempting to regulate the emotional lives of its individual members or to protect them from unhappiness and anyway has no meaningful ability to do so

Given that pain and suffering are literally and permanently unavoidable in human life, teaching others to be resilient rather than teaching them to be victims is an act of mercy, and cultivating resilience in yourself is an act of essential personal growth and adult development

Unhappy emotions, even chronic unhappy emotions, are inherent and ineradicable elements of the human condition, with boredom and disappointment something like the default state of adult life for those of us lucky enough to be financially secure in the developed world

Your pain is important and we should all want to help you heal, but everyone else is hurting too and the fact that you are hurting does not give you any special privileges

Human beings are self-deceiving creatures, and what we often need from others is to be told that we are wrong - that what we believe is wrong, that what we want is unrealistic, that the way we’ve behaved is unjustifiable

Not getting what you want is a default and healthy status, not a tragedy, though you are perfectly within your rights to be unhappy about it, and people who do not give you everything you want are not inherently “toxic,” though you’re perfectly within your rights to be unhappy with them

Self-diagnosis is inherently unhealthy, without exception

Acting as though the social and personal rules that apply to children should apply to you when you are an adult ensures that you will behave selfishly and hurt others, and the constant celebration of childish behavior in adults has profound negative consequences for all of us

Many conflicts in life involve multiple people making equally valid attempts to secure what they want in matters that are genuinely zero-sum, meaning that society actually can’t satisfy the desires of everyone, and most of the time, these conflicts are between people who are all principled and decent and who are simply trying to achieve their goals and desires the way we all do

Some people are just assholes, not narcissists, not toxic, not under the influence of the “Dark Triad,” not sociopaths or psychopaths, not BPD, not any other tendentious medicalized term you’ve used to express your distaste for them - they’re just assholes

Sometimes you're the asshole

Disagreement, expressed in language, can never be violence

When you experience trauma or grapple with your mental health, most people around you are trying their best to be kind and respectful to you, and creating long lists of behavioral or communicative standards that they will inevitably be unable to satisfy is your failure, not theirs

Sick people have as much responsibility to manage their disorders as society has to give them the tools to manage them; you cannot ask others to give you accommodation for your disability if you refuse to take accountability for it yourself

The natural place to look for love, acceptance, and affirmation when you need them is your close friends and family, the people with whom you have mutual emotional attachment, as they are the best equipped to help and the people whose opinion you care about the most; expecting strangers or society writ large to care about you the way your loved ones care about you is deluded and disordered

Some talented artists are able to turn their pain into compelling art, and some talented writers and thinkers are able to publicly explore mental illness in an interesting and generative way, but that kind of talent is rare, and trauma and mental illnesses are not only not inherently interesting, they’re usually intensely boring

You are not your pathologies, you are not your sickness, and you must be able to survive as just the person that you are, without a crutch

Once upon a time, there was strong social value in being “cool,” with the concept of cool referring to a studied indifference to the vagaries of fate; turning away from the pursuit of cool to defining ourselves according to our weaknesses and neuroses was a profound mistake, cool was a humane and correct social value, and we should return to it.

Prologue to an Anti-Therapeutic, Anti-Affirmation Movement

0 notes

Text

"You Should Never Tell a Psychopath They Are a Psychopath. It Upsets Them": Villanelle, Joe Goldberg and Feeling Sorry for Psychopaths

What do you envision when you hear the word? I’d hazard a guess it’s your prototypical psychopath with a dead-eye stare and blood-stained knife in hand. Perhaps it’s your conspiracy theorist neighbour, or that — yes, that one — ex. We’ve seen Villanelle’s theatrical murders on ‘Killing Eve’ and we’ve rooted for Joe in ‘You’ despite his murder habit. We’ve read articles with clickbait titles on how to “spot” a psychopath and immediately diagnosed our sibling, colleague or ex-best friend. It’s a term we throw around carelessly, yet it also inspires fear. A real psychopath isn’t like us and they certainly aren’t worth any kind of sympathy. We’re good people and they’re crazy, violent, controlling, unemotional and self-obsessed. Right?

Sweet but a psycho

Popular culture has given us infamous psychopaths throughout the decades and a couple of our contemporary favourites must be Oskana Astankova — the Russian assassin “Villanelle” -from hit TV show ‘Killing Eve’ and Joe Goldberg from Netflix’s ‘You’. Despite their psychopathic tendencies, fans champion their victories.

Psychologist Robert Hare devised the ‘Psychopath Checklist’ back in 1980 and it is now routinely referred to as the PCL-R. Villanelle and Joe would score highly: both characters believe they are of great importance, routinely lie, act impulsively, struggle with control, take zero to little accountability for their actions, lack empathy, and have a history of criminality and behavioural problems.

Hare’s checklist is still doing the rounds in institutions worldwide, usually prisons, but it has come under plenty of criticism for what Willem Martens (2008) deems as being an unethical psychological practice. It’s difficult to diagnose the term “psychopath” but several diagnoses may suggest a fit, from Antisocial Behaviour Disorder to psychopathy and various other personality disorders.

Already, we see how complex a diagnosis it and encounter very different views from psychologists when it comes to the question of the psychopath. Yet, as we progress as a society, so does science. Science isn’t rigid, stuck in a time of Freud and every other straight, white, wealthy, old, neurotypical male philosopher and psychologist from the 20th century. It moves with society and it adapts as our knowledge deepens. Nowadays, some psychologists and mental health practitioners are rejecting the label “psychopath” completely due to the severely negative connotations and even calling psychopathy a mental health issue or disability.

Psychology says what?

Identity is an important factor when it comes to being human. Our identities are important to us, especially as we engage and present these identities online. Psychopaths are said to be so unlike the majority they are unable to make genuine connections with others but as with anyone deemed ‘different’, it is the group that collectively rejects the ‘different’ individual, perpetuating a cycle of low interpersonal integration and marginalisation.

If given an official diagnosis with a working label of “psychopath”, combined with society’s current view of what it means to be a psychopath, a psychopath is quickly forced to the outskirts of society thus lowering their commitment to fulfilling social roles. A self-fulfilling prophecy becomes imminent: when someone is thought of and treated as if they are somehow broken, they often become it.

Noel Smith is the commissioning editor of magazine InsideTime and a former prisoner who has experienced his fair share of mental health difficulties. Writing for InsideTime, Smith says: “If people think you’re MAD, then everything you do, everything you think, will have MAD stamped across it.”

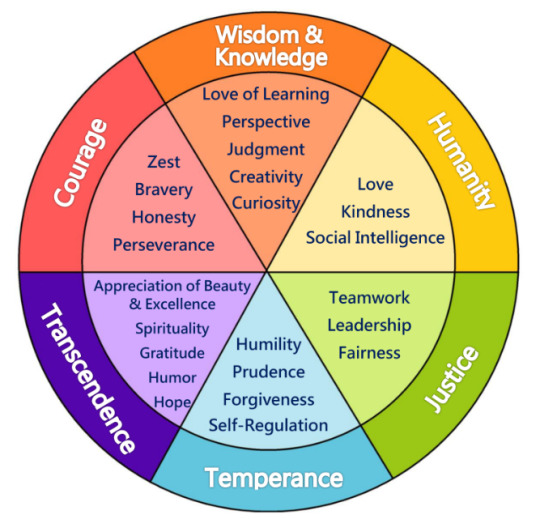

Psychologists Peterson & Seligman (2004), tired of psychology’s tendency to focus on the deviant side of humanity, proposed we all have the ability to express ‘the six common virtues’: wisdom and knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance and spirituality or transcendence.

Here, Peterson & Seligman neatly demonstrated how language can create a narrative. The psychopath according to Hare’s checklist could be grandiose and controlling, but with a slightly different view, they’re confident and courageous leaders. We associate the term so often with negative traits that we ignore the possibility for positives.

Mental health matters — but not for you

“They [psychopaths] are the social snakes in the grass that slither and smile their way into your life and emotions. They feel no empathy, and only care about themselves” says Dr Xanthe Mallett, a forensic anthropologist and criminologist at Newcastle University.

Dr. Mallett’s words reinforce an age-old belief: the psychopath’s only identity is psychopath and they are incapable of being anything other than one-dimensional.

Author Nathan Filer expressed his initial dismay that once his diagnosis was televised by ‘Meet the Psychopaths’ programme on Channel 5, strangers expressed their fear and revulsion immediately. Filer states he “quickly got over” people’s negative opinions but received abuse on the streets with words such as “psycho” and “nutter” shouted at him on a regular basis, reinforcing the rejection by the collective.

Lucy Nichol, writer and mental health support activist, expressed her fears when joining a discussion panel at the Centre for Life Science’s speakeasy programme for adults in 2019. Nichol, rightfully, is anxious about the welfare of those living with psychosis and how they can be discriminated against due to fear. She worries that psychopaths can be “violent and frightening”, and any potential link between psychopaths and people living with psychosis can lead to danger for people with psychosis. Resistant to the movement of psychopathy being welcomed into the family of mental health, Nichol argues it should not be treated as a mental health concern. Her argument is that a classified psychopath lacks empathy and is unable to judge other people’s emotions and this makes the people around the psychopath vulnerable, not the psychopath.

Yet, other mental health conditions and disorders can lead to an individual not necessarily being able to empathise in the way a neurotypical person may empathise. Similarly, an individual with autism, a panic disorder or psychosis may have limited capacity to judge other people’s emotions on occasion. As a society, we tend to understand this and accommodate it.

In contrast to Nichol’s view, there are more and more calls for understanding psychopathy in broader, more compassionate terms.

Dr Luna Centifanti, Lecturer in Psychological Sciences at University of Liverpool classes psychopathy as a mental illness that means the individual experiences “disordered thinking, emotions and behaviour.” She added that psychopathy can lead to struggles with understanding emotions of others and therefore their responses to distress can be “inappropriate”.

Do better, be better

Joseph Newman is a psychologist at Wisconsin University who classifies psychopathy as a disability. Newman explains it as an ‘informational processing deficit’ where individuals have less ability to process cues immediately such as someone else’s fear or upset, inviting us to see the psychopath through a more sympathetic lens.

Campaigners, researchers, activists and those with lived experiences of mental health conditions and illnesses have made huge strides for inclusivity and understanding. As professionals such as Newman and Dr. Centifanti begin to deconstruct the pathological idea of psychopathy, it is being tentatively considered as a mental health issue.

Let’s go back to Villanelle. Her history is relatively secret, but the viewer knows she’s spent time in Russian prison and has no family, therefore little connection to others. Her violent, ‘psychopathic’ actions are a result of her occupation as an assassin as opposed to something she does simply for the joy of enacting violence.

A recent soundbite suggests the show’s writers are no longer calling Villanelle a “psychopath” after astute fans have criticised the way it reduces her to a label.

Be more psychopath

A merge of popular culture, sociology and psychology has begun to turn the connotations of ‘psychopath’ on its head somewhat. The Wisdom of Psychopaths by Kevin Dutton (2012) looks to diagnosed psychopaths to teach us how to care less about other people’s emotions and our own, be fearless in our jobs and have an unwavering belief in ourselves. Western culture is a key culprit in promoting the idea that an impressive salary equals success or showing emotion at work is unprofessional, so, maybe it’s true — we could learn a lot about success from a psychopath.

On the flip side, while these traits have the potential to lead to fantastical financial and business success in aggressively capitalist societies, that doesn’t make them inherently good. Now more than ever seems to be a time where we need to cultivate harmony, compassion and vulnerability for all people regardless of individual status, label or identity.

“It isn’t hard to convince someone you love them if you know what they want to hear”

An eyebrow raising sentence from everyone’s favourite cute psychopath, You’s Joe Goldberg. It is wonderfully inclusive to change the narrative on psychopathy but surely there’s a reason for its fierce reputation. Maybe Dr. Mallet was right in that the psychopath is always a sneaky snake, ready to pounce and sink their psychopathic poison into our blood.

Manipulation is one of the terms we regularly hear associated with psychopathy. If psychopaths are prone to manipulating others, it can be argued that simple survival instincts mean non psychopathic individuals want to protect themselves and society from such behaviour. However, by perpetuating the hype of how dangerous psychopaths are, we just come back to an earlier point made in this article that the collective ostracises the psychopath and therefore impacts their ability to comply with social norms.

Hug your local psychopath

It seems that one of the prevailing mainstream perspectives on psychopathy is that a psychopath is someone evil: they were born evil; they are evil, and they’ll die evil. Hopefully you’ll now join me in disagreeing with that sentiment and see psychopathy as a complex mental health issue where everyone experiencing it is different and deserves to have the chance to be defined beyond a label.

No one is innately criminal or violent. While yes, there are links between criminality, violence and psychopathy, it’s worth remembering that we live in a time of mass media consumption that loves to sensationalise. The need to sell and to exaggerate often win over the need to be patient, analyse and truly understand complex parts of the human experience.

Psychology’s flirtations with neuroscience have revealed fascinating results: the brain, what a non-scientist would likely assume is a fixed and unchangeable organ, does and can change. Our brains are individual and through theories of neuroplasticity we can understand the vitality of our social environment on our brain and therefore behaviour. Psychopaths cannot be excluded from this.

Psychology and sociology are working to explore links between criminality and disadvantage or oppression. If criminality is linked to psychopathy, we must ask why, and be prepared to look at an individual’s history and their social environment.

Frankly, many of the accusations thrown at psychopaths do not work for neurodiverse people. Whether it’s an anxious person unable to understand why their habits, born from their anxiety, frustrate their travel buddy or a psychopath who — as Dr. Newman believes — can’t recognise their words or behaviour has upset someone until much later, the world can be a confusing puzzle for those of us who do not fit neatly into the expected norm.

In expanding compassion and understanding to others regardless of what condition or disorder they may have, we can be instruments of change. Once we look to others and try to understand them, we deconstruct labels that lead to marginalisation and instead, we can bring people together by saying: you are not alone.

**

#xan youles#psychology#personality disorder#psychopathy#psychopath#mental health#mental health activism#anti stigma#psychologist#neuroscience#academia#academic#essay#original essay#original writing#writer#don't use terms you don't understand sweetheart#inclusive language#inclusion#inclusivity#professional#villanelle#killing eve#joe goldberg#you netflix

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are somethings to think about!

Is there a significant decrease in the well-being of individuals on the experience of living in highly urbanized areas? Why?

Is living in highly urbanized area increases chances of having poor lifestyle, affects family more negatively than positively? (stress, alcohol, smoking, drug addiction, etc.)

The following are the data sets I considered to further validate the possible results of my hypothesis:

1. For the data on the experiences in living situations and environments in urban areas – I chose the data from National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health

2. For the comparison of data on the employment rate, income, quality of life in the urban places of different countries – I chose Gapminder data

3. For the association of epidemiological effects of drug use and other health conditions by living in urban areas - I chose the data from The U.S. National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)

Some findings in related literatures will also gave evidences and variables that can be contributory to the quality or kind of life some people have in urban areas.

Let’s see some researches that gives light to the reality of our questions above.

Urbanization's physical and social impacts on health and disease are known. Although causal relationships are not fully established, poor health is associated with poverty, malnutrition, poor housing, inadequate sanitation, pollution, and economic and psychological stresses, as well as with inadequate health services. Urbanization in industrialized and developing countries has brough about increased human exposure to health hazards: biological, chemical, physical, social, and psychological… but urban congestion and pollution threaten the health of people in all countries.

Statistics provided by the United Nations Center of Human Settlements show that the contribution to housing stock by the informal sector (not registered by the authorities, do not keep accounts, and employ mostly casual labour for sites and construction) is significant: for example in the Philippines 86% of the housing stock increase was produced by the informal sector, in Brazil 82%, in Venezuela 77%, in Colombia 64%, and in Chile 44% (UNCHS, 1988b).

(Urbanization, Health and well-being: A Global Perspective by G. Goldstein, 1990)

The impact of socio-economic effects on health can be complex in urban populations. High income should theoretically improve many health outcomes, but it may also support an unhealthy lifestyle, as poor early conditions increase the risk of obesity in a subsequently more socio-economically developed environment.

Increasing socio-economic status may result in an elevated risk of chronic pathologies.

Urban consumerism can be associated with a markedly elevated generation of anthropogenic pollutants, either through lifestyle choices (e.g., car usage) or industry (e.g., factories, e-waste dismantling).

Many standard air pollutants increase with degree of urbanization. These include particulate matter (PM), which has been among the highest in the world in China since economic expansion began in the 1980s, and products of combustion. Urbanization may affect water quality through an excess of contamination including endocrine disrupting chemicals, antibiotics, steroid hormones, and excess nutrients. Elevated exposures to chemicals can also arise in indoor environments (e.g., from new building materials or furnishings).

(Understanding and Harnessing the Health Effects of Rapid Urbanization in China by Yong-Guan Zhu, John P.A. Ioannidis, Hong Li, Kevin C. Jones, and Francis L. Martin, 2011)

Urban socialization leads to two characteristics, Individualistic and materialistic in their outlook. Furthermore, cities can also offer so many other negative ideologies including hedonistic cultures such as entertainment, clubbing, free sex, drugs phonographic and so on, ad search for instant gratification.

Competing for space leads to the emergence of squatter and slum areas. Concisely, urbanization trend today may be seen as nothing less than the urbanization of poverty and deprivation. This scenario is one of growing unemployment, weak social services, lack of adequate shelter and basic infrastructure as well as increasing disparities resulting in a high degree of social exclusion. These are, of course, the well-known causes of social dysfunction, crime, and violence.

Malaysian gov't is having difficulties trying to solve several social problems such as 'mat rempit', free sex and abortion that have not been heard before. Mat Rempit (illegal motorbike racing). They do not only engage in racing among themselves but also challenge other road users to race with them or they will fight with those who try to stop them. These problems are associated with dense population as well as low moral values.

Prejudice and discrimination would certainly develop in this kind of environment and social conflict will erupt at any time.

The issue of crim and violence also draws the same concern. We are aware that security and safety is paramount for human wellbeing. In the same vein, crime and violence disproportionately affect the psychology of urban residents.

Neighborhoods isolate their families because of danger. Together the populations and spaces of cities present both opportunities and challenges to well-being and healthy development. This leads to the theoretical and practical question for urban psychology i.e. the consequences of urban life for mental health, well-being, and development.

Much psychological research has documented the relationship between stress and health outcomes. Because of the nature of the urban environment (i.e., high density, diversity, environmental pollutant), many types of stress-related cases occur more frequently among its residents in comparison to rural or suburban residents.

In Malaysia, residence, or home for most of urban dwellers would means flat, condominium, apartment or terrace house with building scenario and manmade landscape which is often poorly laid out. This kind of environment would certainly affect the psychological wellbeing of the urban folks.

(Urbanism, Space and Human Psychology: Value Change and Urbanization in Malaysia by Zaid B. Ahmad, Haslinda Abdullah and Nobaya Ahmad, 2009)

Urbanization brings with it a unique set of advantages and disadvantages. This demographic transition is accompanied by economic growth and industrialization, and by profound changes in social organization and in the pattern of family life. Urbanization affects mental health through the influence of increased stressors and factors such as overcrowded and polluted environment, high levels of violence, and reduced social support.

Impact of urbanization is associated with an increase in mental disorders. The reason is that movement of people to urban area needs more facilities to be made available and infrastructure to grow. This does not happen in alignment with the increase of population Hence, lack of adequate infrastructure increases the risk of poverty and exposure to environmental adversities. Further this also decreases social support (Desjarlais et al., 1995) as the nuclear families increase in number. Poor people experience environmental and psychological adversity that increases their vulnerability to mental disorders (Patel, 2001).

A report by World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization) has enumerated that mental disorders account for nearly 12% of the global burden of disease. By 2020, these will account for nearly 15% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost to illness. Incidentally, the burden of mental disorders is maximal in young adults, which is considered to be the most productive age of the population. Developing countries are likely to see a disproportionately large increase in the burden attributable to mental disorders in the coming decades (WHO Mental Health Context 2003).

When we refer to psychiatric disorders anxiety and depression are more prevalent among urban women than men and, are believed to be more prevalent in poor than in non-poor urban neighborhoods (Naomar Almeida-Filho et al 2004). The meta analysis by Reddy and Chandrashekhar(1998) revealed higher prevalence of mental disorders in urban area i.e., 80.6%, whereas it was 48.9% in rural area. Mental disorders primarily composed of depression and neurotic disorders.

Increase of nuclear families in urban society has led to increase in cases of violence against women in general. Among them, intimate-partner violence links to alcohol abuse and women’s mental health. Analysis of community-based data from eight urban areas in the developing world indicates that mental and physical abuse of women by their partners is distressingly common with negative consequences for women’s physical and psychological well being (Lori L. Heise et al 1994). Poverty and mental health have a complex and multidimensional relationship. The urbanization leads to forming set of group as “fringe population” who earn on daily basis (Mursaleena Islam etal 2006)

Women are particularly vulnerable and they often disproportionately bear the burden of changes associated with urbanization. Domestic violence is also highly prevalent in urban areas. In both developed and developing countries, women living in urban settings are at greatest risk to be assaulted by their intimates (Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995)

(Urbanization and Mental Health by Kalpana Srivastava, 2009)

With the evidences studied all over the world about the effects of urban living to the individual wellbeing can be cautiously frightening and something that we should all be aware about specially for those who are already living in big cities.

We can find ways to use the researches and studies on urban living and make meaning to it for the improvement of life.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gatekeeping neurodiversity is artificial, socially constructed, and subjective

In modern progressive thought, there are two co-existing ways of looking at atypical brains:

1) Mental illness

2) Neurodiversity

The orthodoxy is that mental illness is bad, while neurodiversity is good.

How do we define mental illness? Well, for starters, do we even? The WHO, for example, prefers the term “mental disorders”, defined:

Mental disorders comprise a broad range of problems, with different symptoms. However, they are generally characterized by some combination of abnormal thoughts, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others. Examples are schizophrenia, depression, intellectual disabilities and disorders due to drug abuse. Most of these disorders can be successfully treated.

The charity Mind also does not use the phrase “mental illness”, instead defaulting to “mental health problems”. For their part, they say:

In many ways, mental health is just like physical health: everybody has it and we need to take care of it.Good mental health means being generally able to think, feel and react in the ways that you need and want to live your life. But if you go through a period of poor mental health you might find the ways you're frequently thinking, feeling or reacting become difficult, or even impossible, to cope with. This can feel just as bad as a physical illness, or even worse.

So mental health issues, or mental disorders, involve:

Some combination of abnormal thoughts, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others.

The ways you frequently think, feel, or react become difficult or even impossible to cope with.

Mental health is changeable - you can go through periods of good or bad mental health.

By contrast, neurodiversity is defined by academic Nick Walker as follows:

Neurodiversity is an essential form of human diversity. The idea that there is one “normal” or “healthy” type of brain or mind or one “right” style of neurocognitive functioning, is no more valid than the idea that there is one “normal” or “right” gender, race or culture.

The classification of neurodivergence (e.g. autism, ADHD, dyslexia, bipolarity) as medical/psychiatric pathology has no valid scientific basis , and instead reflects cultural prejudice and oppresses those labeled as such.

The social dynamics around neurodiversity are similar to the dynamics that manifest around other forms of human diversity. These dynamics include unequal distribution of social power; conversely, when embraced, diversity can act as a source of creative potential.

(My formatting)

Now note that Walker’s definition doesn’t create a harsh separation between “neurodivergence” and “mental illness”. Indeed, it specifically includes a condition - bipolarity - which most people would happily class as a mental illness.

Of course, Walker isn’t the oracle of truth - he has informed opinions, but they’re just opinions, and his definition is a statement of what he considers the best definition to be, rather than a worked explanation of how he came to that definition. So, how could we separate neurodiversity from poor mental health?

First, I recently raised this question with someone who said the answer was that mental health is “not neurological”. This is not true. Depression, for example, has a big impact on your neural development, and our most effective treatments involve messing around with neurotransmitters. Your mind is entirely neurological, therefore your mental health is entirely neurological.

Second, the notion that mental illness is a thing you don’t want, while neurodiversity is a thing you do want. But some people dislike being autistic, ADHD, dyslexic, or dyspraxic, and those are supposed to be the friendly faces of neurodiversity. Meanwhile, there are plenty of people who embrace being bipolar, OCD, schizophrenic, and even depressed or anxious.

Third, the idea that neurodiversity involves talents, gifts, or valuable alternative viewpoints, while mental illness does not. Again, this quickly runs into trouble. For starters, an extreme version expects neurodivergent people to have wonderful abilities like Stephen Wiltshire. This is both untrue, and somewhat patronising. Neurodiversity is ordinary. But moreover, many conditions often deemed mental illnesses once again can come with advantages. A friend of mine with anxiety says that although she sometimes finds it unpleasant, she’s glad she has anxiety as she feels it motivates her to be nicer to other people. This is not my personal experience of anxiety, but her viewpoint is just as valid. The same clichés you hear about autistic people also apply to schizophrenics - famous schizophrenics include Jack Kerouac, Syd Barrett and John Nash, and probably Vincent Van Gogh, and in all cases their condition is routinely associated with their talent. Kanye West calls being bipolar his “superpower”.

Fourth, the idea that neurodiversity is permanent whereas mental illness is transient. Again, this doesn’t work. Many mental illnesses are not transient. As with autism, most mental illnesses have genetic components. And would we not class someone who became autistic due to a brain injury as “neurodiverse”?

Fifth, the idea that we can determine what is an “illness” and what is merely a “condition” by leaving it to psychiatrists or other professionals. Alas, we can’t - they routinely get it wrong. Diagnosis with a “mental illness”, a neurodivergence, or nothing at all is very much dependent on when and where you live. This is not meant to knock psychiatrists by any means, but we should not pretend that they are objective - they know a lot, but the founding purpose of the neurodiversity movement was to push back against common psychiatric assumptions.

I will skip over, for now, neurodegenerative conditions such as MS, ME, or dementia, but please do bear them in mind.

So, what definitions might work?

Well, try these on for size:

- Conditions are always neurodiversity. Neurodivergence is always good, but sometimes an individual will be distressed by one or more symptoms arising due to that neurodivergence and will seek treatment for those symptoms. Sometimes those symptoms could be understood as mental health difficulties.

or:

- A person can use neurodivergence and mental illness as they feel is appropriate to refer to themselves. Maybe they’re a person with chronic depression who is nonetheless glad they have a mind prone to depression. Maybe they have ADHD and want it cured. Maybe those two people are the same person. We, the neurodiversity community, should not gatekeep who gets to be part of our community.

What I’m suggesting is that, just as race, sexuality, and gender can be understood as social constructs, so too can the divide between “good neurodiversity” and “bad mental illness”.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jasbir K. Puar, Bodies with New Organs: Becoming Trans, Becoming Disabled, 33 Social Text 45 (2015)

“Transgender rights are the civil rights issue of our time.” So stated Vice President Joe Biden just one week before the November 2012 election. This article critically reframes calls such as this by foregrounding a historical trajectory not celebrated by national LGBT groups or media or explicitly theorized in most queer or trans theory: the move from the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act to the present moment of trans hailing by the US state. Such a trajectory helps map the ways that neoliberal mandates regarding productive, capacitated bodies entrain the trans body to recreate an abled body not only in terms of gender and sexuality but also in terms of economic productivity and the economic development of national economy. Rather than argue for a better form of discretion between the categories of trans and disability, this article analyzes the ontological irreducibilities of such categories, irreducibilities that dissolve them through multiplicity. In following the implications of such an argument, this article unfolds trans and disability studies' concerns within a broader analysis of the geopolitics of racial ontology.

“Transgender rights are the civil rights issue of our time.” So stated Vice President Joe Biden just one week before the November 2012 election. Months earlier President Barack Obama had publicly declared his sup- port for gay marriage, sending mainstream LGBT organizations and queer liberals into a tizzy. Though an unexpected comment for an election season, and nearly inaudibly rendered during a conversation with a concerned mother of Miss Trans New England, Biden’s remark,1 encoded in the rhetoric of recognition, seemed logical from a now well-established civil rights–era teleology:2 first the folks of color, then the homosexuals, now the trans folk.3

What happens to conventional understandings of “women’s rights” in this telos? Moreover, the “transgender question” puts into crisis the framing of women’s rights as human rights by pushing further the relationships between gender normativity and access to rights and citizenship. I could note, as many have, that failing an intersectional analysis of these movements, we are indeed left with a very partial portrait of who benefits and how from this according of rights, not to mention their tactical invocation within this period of liberalism whereby, as Beth Povinelli argues, “potentiality has been domesticated.”4 As Jin Haritaworn and C. Riley Snorton argue, “It is necessary to interrogate how the uneven institutionalization of women’s, gay, and trans politics produces a transnormative subject, whose universal trajectory of coming out/transition, visibility, recognition, protection, and self-actualization largely remain uninterrogated in its complicities and convergences with biomedical, neoliberal, racist, and imperialist projects.”5 In relation to this uneven institutionalization, Haritaworn and Snorton go on to say that trans of color positions are “barely conceivable.” The conundrum here, as elsewhere, involves measuring the political efficacy of arguing for inclusion within and for the same terms of recognition that rely on such elisions. There is a tension between the desires for trans of color positions to become conceivable and their bare inconceivability critiquing and upending that which seems conceivable.

Biden’s remarks foreshadow the steep cost for the intelligibility of transgender identity within national discourses and legal frames of recognition. Does his acknowledgment of transgender rights signal the uptake of a new variant of homonationalism—a “trans(homo)nationalism”? Or is transgender a variation of processes of citizenship and nationalism through normativization rather than a variation of homonationalism? In either instance, such hailings, I argue, generate new figures of citizenship through which the successes of rights discourses will produce new biopolitical failures—trans of color, for one instance. Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura call the “production of transgender whiteness” a “process of value extraction from bodies of color” that occurs both nationally and transnationally.6 Thinking of this racial dynamic as a process of value extraction highlights the impossibility of a rights platform that incorporates the conceivability of trans of color positions, since this inconceivability is a precondition to the emergence of the rights project, not to mention central to its deployment and successful integration into national legibility. Adding biopolitical capacity to the portrait, Aizura writes that this trans citizenship entails “fading into the population . . . but also the imperative to be ‘proper’ in the eyes of the state: to reproduce, to find proper employment; to reorient one’s ‘different’ body into the ow of the nationalized aspiration for possessions, property [and] wealth.”7 This trans(homo)nationalism is therefore capacitated, even driven by, not only the abjection of bodies unable to meet these proprietary racial and gendered mandates of bodily comportment but also the concomitant marking as debilitated of those abjected bodies. The debilitating and abjecting are cosubstancing processes.

In light of this new but not entirely unsurprising assimilation of gender difference through nationalism, I want to complicate the possibilities of accomplishing such trans normativization by foregrounding a differ- ent historical trajectory: one not hailed or celebrated by national LGBT groups or the median or explicitly theorized in most queer or trans theory. This is the move from the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to the present moment of trans hailing by the US state.8 Historically and contemporaneously, the nexus of disability and trans has been fraught, especially for trans bodies that may resist alliances with people with dis- abilities in no small part because of long struggles against stigmatization and pathologization that may be reinvoked through such an affiliation. But stigmatization is only part of the reason for this thwarted connection.

Neoliberal mandates regarding productive, capacitated bodies entrain the trans body to recreate an abled body not only in terms of gender and sexuality but also in terms of economic productivity and the economic development of national economy.9 Thus, trans relation to disability is not simply one of phobic avoidance of stigma; it is also about trans bodies being recruited, in tandem with many other bodies, for a more generalized transformation of capacitated bodies into viable neoliberal subjects.

Given that trans bodies are reliant on medical care, costly pharmacological and technological interventions, legal protections, and public accommodations from the very same institutions and apparatuses that functionalize gender normativities and create systemic exclusions, how do people who rely on accessing significant resources within a political economic context that makes the possessive individual the basis for rights claims (including the right to medical care) disrupt the very models on which they depend in order to make the claims that, in the case of trans people, enable them to realize themselves as trans in the first place? I explore this conundrum for trans bodies through the ambivalent and vexed relationship to disability in three aspects: (a) the legal apparatus of the ADA, which sets the scene for a contradictory status to disability and the maintenance of gender normativity as a requisite for disabled status; (b) the fields of disability studies and trans studies, which both pivot on certain exceptionalized figures; and (c) political organizing priorities and strategies that partake in transnormative forms not only of passing but also of what I call “piecing,” a recruitment into neoliberal forms of fragmentation of the body for capitalist profit. Finally, I offer a speculative differently imagined affiliation between disability and trans, “becoming trans,” which seeks to link disability, trans, racial, and interspecies discourses to make boundaries porous through the overwhelming force of ontological multiplicity, attuned to the perpetual differentiation of variation and the multiplicity of affirmative becomings. What kinds of assemblages appear that might refuse to isolate trans as one kind of specific or singular variant of disability and disability as one kind of singular variant of trans? What kind of political and scholarly alliances might potentiate when each takes up and acknowledges the inhabitations and the more generalized conditions of the other, creating genealogies that read both as implicated within the same assemblages of power? The focus here is not on epistemological correctives but on ontological irreducibilities that transform the fantasy of discreteness of categories not through their disruption but, rather, through their dissolution via multiplicity. Rather than produce conceptual interventions that map onto the political or produce a differently political rendering of its conceptual moorings, reflected in the debate regarding transnormativity and trans of color conceivability, I wish to offer a generative, speculative reimaging of what can be signaled by the political.

I. Disability Law and Trans Discrimination

The legal history that follows matters because it both re ects and enshrines a contradictory relationship of trans bodies that resist a pathological medicalized rendering and yet need to access bene ts through the medical industrial complex. The explicit linkages to the trans body as a body either rendered disabled or (perhaps and, given the teleological implications) rehabilitated from disability have been predominantly routed through debates about gender identity disorder (GID). Arriving in the DSM-III (third edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published in 1980, on the heels of the 1974 DSM-II depathologization of homosexuality, GID was eliminated in the DSM-5 released in May 2013, now replaced with gender dysphoria.10 These complex debates have focused largely on a series of explicit inclusions and exclusions of GID in relation to the DSM and the ADA. The inclusion of GID in 1980 and its focus on childhood behavior were largely understood as a compensatory maneuver for the deletion of homosexuality, thus instating surveillance mechanisms that would perhaps prevent homosexuality.11 In contrast, a notable passage in the ADA details the speci c exclusion of “gender identity disorders not resulting from physical impairments” as a disability—couched in an exclusionary clause that included “transvestitism, transsexualism, pedophilia, exhibitionism, voyeurism, . . . ‘other sexual disorders,’” and completely arbitrary “conditions” such as compulsive gambling, kleptomania, pyromania, and substance use disorders involving illegal drugs.12 This clause was largely understood (unlike the specific exclusion of homosexuality) as an entrenchment of the pathologization of GID. This deliberate inclusion of the terms of exclusion is a crucial piece of the story, in part because to date the ADA is “the most extensive civil rights law to address bodily norms.”13

Given the ADA’s hodgepodge of excluded conditions, many of which carry great social stigma and/or are perceived as criminal activity, most commentators concur with L. Camille Herbert’s sentiment that “while one might argue for the exclusion of certain conditions from the definition of disability as justified by not wanting to pathologize certain individuals and conditions, this does not appear to have been the motivation of Congress.”14 The process by which Congress arrived at these exclusions also appears marred by moral panic discourses about diseased and debilitated bodies, discourses that the ADA was produced in part to ameliorate. Former senator Jesse Helms (R-NC), writes R. Nick Gorton, “raised the specter that the law would provide disability protections to numerous politically unpopular groups,” concluding that most people who are HIV positive are drug addicts, homosexuals, bisexuals, pedophiles, or kleptomaniacs, among others, and that the exclusion was enacted “as a direct result of Helms’s efforts.”15 Noting that the ADA “unequivocally” endorses the use of the DSM in recognizing conditions of disablement, Kari Hong argues that “understanding why a dozen conditions were removed becomes an important task,” as the exclusion not only disqualifies certain conditions from consideration as a disability but also “isolate[s] particular conditions from medical authority.” Hong also points out that Helms’s “bifurcation of disability into ‘good’ (wheelchairs) and ‘bad’ (transvestitism) categories echoes a disturbing misuse of medicine.”16 Ultimately, Congress capitulated and sacrificed these excluded groups in exchange for holding onto the protection of another vili ed “minority” group: individuals with HIV.17 This move of course insists on problematic bifurcations, perhaps strategically so, between individuals diagnosed with GID and individuals diagnosed with HIV.

Thus, Kevin Barry argues, “the ADA is a moral code, and people with GID its moral castaways.” He adds, “GID sits at the uneasy cross- roads of pathology and difference,”18 an uneasy crossroads that continues to manifest (especially now as GID has been eliminated in the DSM-V).19 Adrienne L. Hiegel elaborates this point at length, with particular emphasis on how this exclusion recodes the labor capacities of the transsexual body. In segmenting off “sexual behavior disorders” and “gender identity disorders” from the ADA’s definition of disability, the “Act carves out a new class of untouchables. . . . By leaving open a space of permissive employer discrimination, the Act identifies the sexual ‘deviant’ as the new pariah, using the legal machinery of the state to mark as outsiders those whose noncompliant body renders them un t for full integration into a working community.”20

In essence, the ADA redefines standards of bodily capacity and debility through the reproduction of gender normativity as integral to the productive potential of the disabled body. Further, the disaggregation, and thus the potential deflation, of political and social alliances between homosexuality, transsexuality, and the individual with HIV is necessary to the solidi cation of this gender normativity that is solicited in exchange for the conversion of disability from a socially maligned and excluded status to a version of liberal acknowledgment, inclusion, and incorporation. The modern seeds of what Nicole Markotic and Robert McRuer call “crip nationalism”—the hailing of some disabilities as socially productive for national economies and ideologies to further marginalize other disabilities—are evident here, as the tolerance of the “difference” of dis- ability is negotiated through the disciplining of the body along other normative registers of sameness, in this case gender and sexuality.21 And further, what Sharon Snyder and David Mitchell term “ablenationalism”— that is, the ableist contours of national inclusion and registers of productivity—ironically underwrites the ADA even as the ADA serves as groundbreaking legislation to challenge it. Snyder and Mitchell describe ablenationalism as the “implicit assumption that minimum levels of corporeal, intellectual, and sensory capacity, in conjunction with subjective aspects of aesthetic appearance, are required of citizens seeking to access the ‘full benefits’ of citizenship.”22 In reorganizing the terms of disability, ablenationalism redirects the pathos and stigma of disability onto different registers of bodily deviance and defectiveness, in this particular instance that of gender nonnormativity. In that sense, crip nationalism goes hand in hand with ablenationalism; indeed, ablenationalism is its progenitor. While these details about the passage of the ADA are obviously not with- out implications regarding racial and class difference, the specific details of the exclusionary clause might gesture toward the multifaceted reasons that, as Snyder and Mitchell observe, “queer, transsexual, and intersexed peopled . . . exist at the margins of disability discourse.”23

It is not simply that the ADA excludes GID and, by extension, trans from recognition as potentially disabling but, rather, that transsexuality— and likely those versions of transsexuality that are deemed also improperly raced and classed—is understood as too disabled to be rehabilitated into citizenship, or not properly enough disabled to be recoded for labor productivity. Further, the ADA arbitrates the distinctions between homosexuality and transsexuality along precisely these pathologized lines. Contrary to what Hiegel claims, the sexual “deviant” is hardly the “new pariah.” Rather, there is a new sexual deviant in town, demarcated from an earlier one. Indeed, the enthusiastic embracing of the ADA by some gay and lesbian activists and policy makers for the exclusion of homo- sexuality as a “sexual behavior disorder” did not go unnoticed by trans activists who felt differently about the ADA.24 Proclivities toward queer ableism are therefore predicated in the ADA’s parsing homosexuality from other “sexual disorders,” as well as in the histories of political organizing. Zach Strassburger describes the process of homonationalism by noting that “as the gay and lesbian rights movement gained steam, the trans- gender movement grew more inclusive to cover those left behind by the gay and lesbian movement’s focus on its most mainstream members and politically promising plaintiffs.”25 Given the political history of parsing trans from queer through the maintenance of gender normativity, can disability function proactively and productively, as a conversion or translation of the stigma through which trans can demarcate its distance from aspects of LGBT organizing that are increasingly normative?26

I offer this brief historical overview to lay out the stakes for the debate between demedicalizing trans bodies (favoring the use of gender discrimination law to adjudicate equality claims) and successfully using disability law to access crucial medical care. What is evident from these discussions is that trans identity, straddling the divide between the bio- medical model and the social model of disability, challenges the postulation that disability studies is “postbinary,” especially given that vociferous debates about the utility of the medical model in trans jurisprudence persist. Strassburger, who argues for an “expanded vision of disability” based on the social model that could be applied for trans rights, notes nonetheless that the medical model of trans has often been more successful than sex and gender discrimination and sexual orientation protection, and that the transgender rights movement in its emphasis on demedicalization (despite reluctantly admitting the success of medical strategy) ignores the pragmatic aspects of litigation. Further, Strassburger notes the historical effects of stigma, writing that “demedicalization would mirror the gay rights movement’s very successful efforts to frame gayness as good rather than a disease.”27

For others, the debate between medicalization and demedicalization forestalls a broader conversation about access to proper medical care, one that has been foregrounded by feminist struggles over reproductive rights, for example.28 Proponents of the use of disability law further note that difficult access to medical care is not a complete given for all disenfranchised populations. For example, Alvin Lee argues that the “unique aspects of incarceration and prison health care justify and indeed compel the use of the medical model when advocating for trans prisoners’ right to sex reassignment surgery.”29 Lee notes that the usual bias against lower- income populations in the use of the medical model does not apply to the “right-to-care” prison context, where medical evidence is the best way to demonstrate serious and necessary rather than elective health care, given the “general principle that individual liberties should be restricted in prison.”30 Other legal practitioners such as Jeannie J. Chung and Dean Spade are curious about the success of social models of disability in transgender litigation. Spade, for example, has carefully elaborated his ambivalence about the use of disability law and the medical mode in relation to his rm social justice commitment to the demedicalization of trans, arguing for a “multi-strategy approach.”31

II. Trans Exceptionalism: Passing and Piecing

In addition to the robust debates about jurisprudence on trans and disability, transgender studies and disability studies are often thought of as coming into being in the early 1990s in the US academy, a periodization that reflects a shift in practices of recognition, economic utility, and social visibility that obscures prior scholarship. In terms of trans, for example, Stryker and Aizura note that “to assert the emergence of transgender studies as a eld only in the 1990s rests on a set of assumptions that permit a differentiation between one kind of work on ‘transgender phenomena’ and another, for there had of course been a great deal of academic, scholarly, and scientific work on various forms of gender variance long before the 1990s.” Among the various historical changes they list as significant to this emergence are “new political alliances forged during the AIDS crisis, which brought sexual and gender identity politics into a different sort of engagement with the biomedical and pharmaceutical establishments.”32

This emergence of disability and trans identity as intersectional coordinates required exceptionalizing both the trans body and the disabled body to convert the debility of a nonnormative body into a form of social and cultural capacity, whether located in state recognition, identity politics, market economies, the medical industrial complex, academic knowledge production, subject positioning, or all of these. As a result, both fields of study—trans studies and disability studies—suffer from a domination of whiteness and contend with the normativization of the acceptable and recognizable subject. The disabled subject is often a body with a physical “impairment”; the wheelchair has become the international symbol for people with disabilities. In trans identity, the more recently emergent trajectory of female-to-male (FTM) enlivened by access to hormones, surgical procedures, and bodily prostheses has centralized a white trans man subject. While the disabled subject has needed to reclaim forms of debility to exceptionalize the transgression and survivorship of that disability, the transnormative subject views the body as endlessly available for hormonal and surgical manipulation and becoming, a body producing toward ableist norms. Further, transgender does not easily signal within “conventional notions of disability” because it is not a “motor, sensory, psychiatric, or cognitive impairment” or a chronic illness.33

The disabled body can revalue its lack, but the transnormative body might desire to rehabilitate itself to a status of nondisabled. Eli Clare, a trans man with cerebral palsy, has generated perhaps the most material on the specific epistemological predicaments of the disabled trans subject or the trans disabled subject, providing much-needed intersectional analysis.34 Clare writes of the ubiquity of this sentiment: “I often hear trans people—most frequently folks who are using, or want to use medical technology to reshape their bodies—name their trans-ness a disability, a birth defect.”35 Here Clare emphasizes the trans interest in a cure for the defect, a formulation that has been politically problematized in dis- ability rights platforms, reinforces ableist norms, and alienates potential convivialities: “To claim our bodies as defective, and to pair defect with cure . . . disregards the experiences of many disabled people.”36 Disability here is not only the “narrative prosthesis”37 through which the trans body will overcome and thus resolve its debility but also the “raw material out of which other socially disempowered communities make themselves visible.”38 Seen through this mechanism of resource extraction, disability is the disavowed materiality of a trans embodiment that abstracts and thus effaces this materiality from its self-production.

Toby Beauchamp adds to the conversation about cure the notion of concealment via legal (identity documents) and medical intervention, stating: “Concealing gender deviance is about much more than simply erasing transgender status. It also necessitates altering one’s gender presentation to conform to white, middle-class, able-bodied, heterosexual understandings of normative gender.”39 The cure, then, revolves around rehabilitation to multiple social norms. Beauchamp further notes that of course the pro- cess of diagnosis and treatment inevitably reinforces this rehabilitation: “Medical surveillance focuses rst on individuals’ legibility as transgender, and then, following medical interventions, on their ability to conceal any trans status or deviance.”40 While access to adequate and sensitive health care for trans people can be a daunting if not foreclosed process, emergent conversations on “transgender health” can also function to reassert neoliberal norms of bodily capacity and debility.41 The transnormative subject might categorically reject the potential identification and alliance with disability, despite the two sharing an intensive relation to medicalization, and perhaps because of the desire for rehabilitation and an attendant indebtedness to medicalization. Clare avers that while the “disability rights movement fiercely resists the medicalization of bodies” to refuse the col- lapsing of the body “into mere medical condition,” in his estimation “we haven’t questioned the fundamental relationship between trans people and the very idea of diagnosis. Many of us are still invested in the ways we’re medicalized.”42

Even in politically progressive narrations of transgender embodiment, for example, an unwitting ableism and the specter of disability as intrinsic disenfranchisement often linger as by-products of the enchantment with the transformative capacities of bodies. For example, Eva Hayward’s take on the “Cripple” toggles a very tenuous line between the “Cripple” as a metaphor of regeneration and the crippling effects of amputation.43 Likewise, Bailey Kier, describing an instance of fishes’ ability to transsex in response to toxic endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), wonders if such transformations are a “technology beyond our grasp,” disregarding the uneven biopolitical distribution of such toxins that render his desires for a global “embracing [of] our shared transsex” violently idealistic: “EDCs are part of the food, productive and re/productive chain of nonhuman and human life and we will need to devise ways, just like sh, to adapt to their influence.”44

I would thus argue that there is a third element here that produces disability as the disavowed material co-substance of trans bodies. While there are understandable desires to avoid stigma and, as the ADA demonstrates, a demand for bodies with disabilities to integrate into a capitalist economy as productive bodies, the third factor involves aspirational forms of trans exceptionalism, one version of which is about rehabilitation, cure, and concealment. However, this exceptionalism is not only about pass- ing as gender normative; it is also about inhabiting an exceptional trans body—which is a different kind of trans exceptionalism, one that gestures toward a new transnormative citizen predicated not on passing but on “piecing,” galvanized through mobility, transformation, regeneration, flexibility, and the creative concocting of the body. Regarding “piecing” as an elemental aspect of neoliberal biomedical approaches to bodies with disabilities now globalized to all bodies, Snyder and Mitchell argue that the body has become “a multi-sectional market” in distinction to Fordist regimes that divided workers from each other: