#rather than the fluidity of gender or sexuality when it comes to identity

Text

one thing that has stuck with me from the latest kerfuffle i got into on twitter is like. there was one person arguin w one the homies that my bio stating i was white isnt accurate because white people cant be people of colour or a poc so putting 'white' in my bio was the reason people wouldnt acknoweldge Im mixed. and like. that shit has stuck w me

cuz to me that seems fucked up towards mixed ppl like me who have that white background mixed with some non-white identity. but thinking about it i can ABSOLUTELY understand the idea of it due to the notion that white people cannot be poc. cuz that sentence in itself is SENSIBLE. like oh Obviously white people cannot be in the non-white community, so therefore mixed people 'cannot' identify as white????

but i keep thinking about it cuz. wow that shit really pointed out an issue that is so obviously present when it comes to recognizing and acknowledging mixed people like me. Because regardless of how much of a Person Of Colour i am or how much aboriginal background i got, i look very white. I have possibly more typically white experiences than typically aboriginal ones. I have blue eyes as when i was a kid I had naturally blonde hair and there was the joke that i was the whitest in my family because of it. which despite the joke is pretty damn true. people dont see me on the street and say oh thats an indigenous person, and the extremely rare times someone sees me as non-white its usually another indigenous person yknow.

I think its like. its kinda led to this revelation of mine i suppose. On one hand i've come to terms with the idea that i am Aboriginal AND white in the sense that i cant just pick either or as both aspects of me have influenced my entire existence as a mixed person. but its really hit home on why i've struggled so much with seeing myself as being in the non-white community or recognizing myself as a person of colour. because the only 'requirement' of being a poc is Not being white. but does that instantly eliminate all mixed white and non-white people like me from being anything other than white? does that not just further the notion that mixed ppl have to just 'pick a side'? Wouldnt decrying my white identity to be a poc then just diminish my own experiences with white privilege and passing as white?

#ask to tag#idk i think its like. when it comes to racial groups and racialized peoples it tends to seem more#black and white (lmao)#in the sense that ethnicity and race isnt something changeable therefore it is treated as more concrete aspects of identity#rather than the fluidity of gender or sexuality when it comes to identity#but in actuality. its really not so easy with race either#like the lines between races and even between that of being white and being non-white isnt so clear#like ive spent years feeling guilt for my identity. as a kid i tried to get rid of my indigenous identity#and somewhat more recently i felt guilty for being white#and its only recently ive resolved that i can be both#but i hadnt explicitly thought about how much of an outlier that makes me#but honestly with mixed white poc i feel its worse to try and limit or get rid of the white aspects of us#like we cannot ignore how it has benefited us or how our general ease as being seen as white has made our lives easier#like i always think of a friend i had in highschool who was also native#but she had the more traditional features of darker skin and black or dark hair unlike me#and we bonded a lot over our aboriginal identity#but the fact she experienced more blatant descrimination than me was a constant factor in our relationship#like it is not something us white poc should not ignore! our expiriences with both privilege and descrimination is unique and unavoidable#i feel the idea of you cannot be white and a poc really tries to bury the privilege of that though. and thus the varied experiences#idk man i been thinkin bout it a lot#like maybe the inclusion of white people who are mixed should be noted in non-white circles more. because of this weird#inbetween we have

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pedro boy sexuality & gender headcanons

A couple weeks ago @perotovar shared their headcanons around Pedro characters and their sexualities and gender identities, here. It was such an interesting read as someone who has had many of my own thoughts around these things, it was really cool to see how someone else sees these characters through a queer lens and the little things in their characterisations that make us connect these thoughts to them, and that makes us connect to them in the way we do.

I mentioned that I would share my own thoughts and so, here we are! We actually have basically the same hcs. Just for a few of the boys for me though as I tend to stay in my Ezra & Dieter corner for the most part. I don’t know some of the other characters well enough to have any major thoughts about them.

I would love love to hear from other queer members of the fandom here, if you have any thoughts to share!

Also obviously these are just my silly little ideas and just for fun, I read all flavour of fanfic and whilst I would love to see more work from an lgbtq+ perpective I will happily consume all the (perceived) straight fic out there.

(I will also just ask that if you feel I have used any outdated/incorrect language here please let me know, I’m always learning, and I’d like to be corrected if there’s anything in here that could be considered harmful).

Ezra – I’ve mentioned it before and maybe it’s just because Ezra is my favourite character of all time but I very much see him as non-binary, genderfluid, using primarily he/they pronouns but doesn't mind any pronouns, and who really doesn’t care about or consider gender much at all. Honestly, this is a sci-fi character and I’d like to think that when we get to the point of living in space gender won’t even be a damn thing anymore lol. In the same vein, Ezra is pansexual.

Dieter – Bisexual king, of course. That’s literally canon. He would most likely label himself as queer and leave it at that though, rather than specifically defining himself as bi. I love to think about Dieter as somewhere under the non-binary umbrella but I’m not entirely sure where yet; gnc although again there is some fluidity there. Also, Dieter’s ideal way to love is in poly relationships, for sure.

Marcus P – Marcus is bi. He is a beautiful bi boyfriend, just look at him. He took a long time to come to terms with his sexuality, but now he is much more comfortable with it and allows himself to have the experiences he missed out on when he was less accepting of himself, and now he can be proud of who he is.

Joel – I actually hadn’t really considered Joel much in this way until Erin’s hcs but now...oh man…Joel is aromantic (and graysexual maybe). I feel it in my gut, like especially thinking a lot about the stuff with Tess. I don’t necessarily think it’s something he fully understands about himself, even in his later years, but it’s there.

Javi P – Hetero. Loves women. We know that. But, I can also see him questioning. I think when Murphy shows up, there’s something there. Something in his mind. He’s the least likely to ever act on it, given the external factors, but he’s certainly had moments of thinking about it which unfortunately probably cause him a lot of anguish.

Din – Aroace. I don’t even know what to say, this just feels very real to me.

Marcus M – Demi oh my god very much demisexual and demiromantic. He needs the connection first, and the rest will follow. He loves hard, and he loves forever when he gets there, much like Erin said he only ever really loved his wife.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

my problem with the "sexuality is fluid" crowd as a lesbian who's confident in their sexuality is that it's often weaponized against us in a way that isn't against gay men due to the added factor of misogyny, plus the fact that we're one of the smallest groups in the community. and to a lot of lesbians drawing a clear line is necessary for us to be happy under a patriarchy. it doesn't help that 90% of the time when people insist that sexuality is fluid they have some weird grudge against lesbians being proud in our lack of attraction to men and will use terfs as a "gotcha" against us

This is perhaps unnecessary, but I want to take a moment to thank you for being respectful and taking what I had to say in good faith, while still offering up your perspective. A lot of people have been very quick into making assumptions about what I'm getting at, and now I not only have to defend my initial point, but also deal with points I never made.

Anyway--Everything you said, I entirely agree with. I think I just made a big mistake with that post in not fully acknowledging the broader, heteronormative contexts which make people uncomfortable with things like "sexuality is fluid" "gender is fake"-- because I was writing that post with the mindset of like, I'm on tumblr surrounded by lgbt people and this analysis ONLY exists within that context. I also addressed too many things-- perhaps my indictment of the vagueness of the term "gay man" came across as me implying that nobody really is one, when all I meant was that, these words are just for convenience, and shouldn't be taken as law.

Like, I really hope y'all understand that I ALSO get hot when some guy tries to tell me he thinks everyone is a little bit bisexual, because in that moment, I now have to defend peoples' right to be entirely homosexual in a society that wants nobody to have gay attraction in the first place. This might seem at odds with my post, but in reality, my goal-- both here and there--is to illustrate that people come with all kinds of sexual identities and attractions and levels of fluidity or rigidity, and BASING pride and confidence in certainty--whether what you're certain about is "all people are 100% gay and men are real" or "everyone's a little bit bi and sexuality is inherently fluid"-- will cause you to feel insecure when you encounter someone who feels differently, or if you yourself start to feel differently. EDIT: But we also don't live in a perfect world! And like you said, sometimes you literally HAVE to base your pride in certainty, because uncertainty is weaponized against you. I should've acknowledged that more clearly.

THAT'S all I meant. I just should've chosen my words more carefully. I should've made the post more hypothetical rather than call to action, since we absolutely don't live in a world where we can be that free yet. And yes agreed, we absolutely need to deal with the misogyny before any of this shit. Thank you for your input.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tumblr has been recommending your posts to me a lot lately, and I've seen that you're trying to figure out which words to describe your identity with, so I want to try to help you out a little!

The most important thing to consider is what you want from your label. Labels can serve many different purposes, but here are some of the key things that they're often used for:

Understanding your identity internally

Finding comfort or joy in words that describe your experiences

Finding community with others who have similar experiences

Expressing your identity to other people, especially quickly

Labels don't have to be used for all of those things, but they're usually going to be used for at least one of those things. You might also use different labels for different reasons, or use different labels in different contexts.

If you're using labels to understand your identity internally, or to find comfort or joy...

... Use whichever ones you feel fit best! It doesn't matter whether it makes sense/seems right to others or not, because the goal is to find something that makes sense/seems right to you. Be as specific, or as broad, as you desire. Use however many labels you want!

You could even make a document listing all of your labels if you want to keep track of them. There's also an attraction tracker and gender tracker if you want to track your experiences over time.

If you're using labels to find community...

... Use labels which are common and/or broad! It's easiest to find community when you're using relatively common or loosely defined labels. If it has a page on this wiki, you've probably got a good shot at finding a community surrounding that label, and thus, finding people whose experiences are similar to yours.

If it doesn't have a page on that wiki, don't worry! You can still try to find community with more niche labels; it just might not be as easy to find people who share your identity.

If you're using labels to express your identity to others...

... Use labels which are common and/or easy to explain! Using more common labels increases the chance that people will understand what you mean to express. Or, if someone doesn't understand what your label means, you'll want to be able to easily explain the definition, or what the word means for you in particular.

It can be hard to gauge how common a label is, especially when you know a lot of labels yourself. But generally, people will have a basic understanding of the following terms, whether those people are members of the LGBTQ+ community or not:

gay

lesbian

queer

bi(sexual)

pan(sexual)

trans(gender)

nonbinary

genderqueer

genderfluid

polyamorous

asexual (though many people think asexual = aroace)

The next terms are a bit of a coin-toss in my experience, but they'll be generally understood by most LGBTQ+ people, and some non-LGBTQ+ people as well:

sapphic

aromantic

demisexual

demiromantic

demigirl

demiboy

agender

omni(sexual)

bigender

xenogender

And regarding fluidity, it is often easiest to give people an "overview" or your identity if possible, rather than whatever specific shift you're experiencing. For example, you might simply say "I'm genderfluid" or "my identity is fluid" or "my identity changes every now and then." Or, if you want to express your current shift, you could say something like, "right now I'm [x], but that could change."

You might use different words depending on your current crowd, because different people will have different levels of understanding when it comes to labels. For example, I generally won't describe myself as pangender or demifluid when describing myself to cis people, but I will describe myself that way if I'm speaking to people who are also trans or nonbinary. Not as a way of hiding who I am, but just as a way of more easily discussing my identity.

You may also use different words in different contexts. For example, I describe myself solely as aromantic when that's the only part of my identity relevant to discuss, even though there are plenty of other aspects of my identity that exist, such as being polysexual, pangender, demifluid, polyaffectionate, a lesbian, or any other aspect of my identity.

And, when labels fail to convey your identity, descriptions are your friend! Can't find a commonly understood word to describe yourself with? Set the labels aside and just use descriptions alone. For example, instead of "I'm fidelityflux," you could say "the number of partners that I desire changes every now and then," or "sometimes I want to have no partners, sometimes I just want one, and sometimes I want multiple," or whichever other description you feel works best.

Hope this is helpful!

Thanks! That actually was helpful!

I mainly want to use labels for the "finding comfort or joy in words that describe your experiences" and "expressing your identity to other people, especially quickly" parts.

I generally understand my queer identity. I have a full Google Doc listing my labels, but I'm not going to tell everyone I meet what's on that Doc (we would be there for hours). I think the best thing to do is tell them the very basic measure of my identity, something akin to "I'm genderfluid, meaning my gender identity changes every day, but I generally want to be seen as a man and referred to as a man." You know, something quick, simple, and straight to the point.

Since I don't plan on dating any time soon, fidelityflux, omniaspec, and omnomi don't matter right now, and pronouns and my name are the most important things outside the internet for me. It's still a major part of who I am, but it doesn't matter right now, so I'll just leave them in my bio until it's relevant for people to know in the real world.

I was originally going to use this blog for fanfiction, but I ended up just making it a queer blog. I mean, most of this stuff is just for me to put my thoughts into words, but I do like hearing people's opinions on it, because sometimes it helps (like my transmasc tips post), or when I specifically ask people for help.

The queerphobic comments I get still hurt, but I've come to accept the fact that I can't change this part of myself.

I really appreciate your response and your willingness to help a complete stranger. You really did help me!

#Faunpronominal#Linumgender#Transgender#Fidelityflux#Afidelitous#Greyromantic#Omniromantic#Greysexual#Omnisexual#Greyplatonic#Omniplatonic#Demisensual#Greysensual#Pansensual#Omniaesthetic#MOGAI#Queer#LGBTQIA+#LGBTQIA#LGBTQ#LGBTQ+#LGBT#LGBT+#LGBTQQIA#2SLGBTQ+#LGBT2SQQIA

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Travis has had both boyfriends and girlfriends since high school. But when his coworkers discovered his dating history at a board game night, they told him he couldn’t be bisexual. “Bi men don’t exist,” they said. “You’re just a confused gay guy.” Travis, 34, had brought his girlfriend with him that night, but they started calling her his “roommate” after they found out he was bi.

Santiago got an even harsher reaction when he came out to his family. “‘Bisexual’ is just code for insincere gay man” is how he said one of his relatives reacted. “He didn’t use the term ‘gay man,’” 24-year-old Santiago told me, “but I won’t repeat slurs.”

In the past couple of months, I’ve heard dozens of stories like these from bisexual men who have had their sexual orientations invalidated by family members, friends, partners, and even strangers. Thomas was called a “fence-sitter” by a group of gay men at a bar. Shirodj was told that he was “just gay but not ready to come out of the closet.” Alexis had his bisexuality questioned by a lesbian teacher who he thought would be an ally. Many of these same men have been told that women are “all a little bi” or “secretly bi” but that men can only be gay or straight, nothing else.

In other words, bisexual men are like climate change: real but constantly denied.

A full 2% of men identified themselves as bisexual on a 2016 survey from the Centers for Disease Control, which means that there are at least three million bi guys in the United States alone—a number roughly equivalent to the population of Iowa. (On the same survey, 5.5% of women self-identified as bisexual, which comes out to roughly the same number of people as live in New Jersey.) The probability that an entire state’s worth of people would lie about being attracted to more than one gender is about as close to zero as you can get.

But the idea that only women can be bisexual is a persistent myth, one that has been decades in the making. And prejudice with such deep historical roots won’t disappear overnight.

👬👫👬👫

To understand why bisexual men are still being told that their sexual orientation doesn’t exist, we have to go back to the gay liberation movement of the late 1960s. That’s when Dr. H. Sharif “Herukhuti” Williams, a cultural studies scholar and co-editor of the anthology Recognize: The Voices of Bisexual Men, told me that male sexual fluidity got thrown under the bus in the name of gay rights—specifically white, upper-class gay rights.

“One of the byproducts of the gay liberation movement is this…solidifying of the [sexual] binary,” Herukhuti told me, citing the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s as a pre-Stonewall period of relatively unstigmatized sexual fluidity.

Four decades later, the gay liberation movement created a new type of man—the “modern gay man,” Herukhuti calls him—who was both “different from and similar to” the straight man. As Jillian Weiss, now the executive director of the Transgender Legal Defense Fund, wrote in a 2003 review of this same history, “gays and lesbians campaigned for acceptance by suggesting that they were ‘just like you,’ but with the single (but extremely significant exception) of [having] partners of the same sex.” Under this framework, attraction to a single gender was the unifying glue between gay men, lesbians, and straight people—bisexual people were just “confused.”

Bisexual people realized that they would have to form groups and coalitions of their own if they wanted cultural acceptance. But just as bisexual activism was gaining a foothold in the 1980s, the AIDS crisis hit, and everything changed—especially for bisexual men.

“AIDS forced certain bisexual men out [of the closet], it forced a lot of bisexual men back in, and then it killed off a number of them,” longtime bisexual activist and author Ron Suresha told me.Those deaths hindered the development of male bisexual activism at a particularly critical moment. “A number of men who would have been involved and were involved in the early years of the bi movement died—and they died early and they died quickly,” bisexual writer Mike Syzmanski recalled.

The AIDS crisis also gave rise to one of the most pernicious and persistent stereotypes about bisexual men, namely that they are the “bridge” for HIV transmission between gay men and heterosexual women. As Brian Dodge, a public health researcher at Indiana University, told me, this is a “warped notion” that has “never been substantiated by any real data.” The CDC, too, has debunked the same myth in the specific context of U.S. black communities: No, black men on the “down low” are not primarily responsible for high rates of HIV among black women.

For decades, bisexual men have been portrayed—even within the LGBT community—as secretly gay, sexually confused vectors of disease.

In 2016, bisexual men are still feeling the effects of the virus and the misperceptions around it.

“We’re still underrepresented on the boards of almost all of the national bisexual organizations,” Suresha told me, referring to the fact that women occupy most of the key leadership positions in bisexual activism. And in a new, nationally representative study of attitudes toward bisexual people, Dodge and his research team found that 43% of respondents agreed —at least somewhat—with the statement: “People should be afraid to have sex with bisexual men because of HIV/STD risks.”

For decades, bisexual men have been portrayed—even within the LGBT community—as secretly gay, sexually confused vectors of disease. Is it any wonder that they are still fighting to shed that false image today? It’s hard to convince people that you exist when they barely see you as human.

👬👫👬👫

It’s not that bisexual women have it easy. Both bisexual men and women are much less likely than gay men and lesbians to be out of the closet, with only 28% telling Pew that most of the important people in their life know about their orientation. Collectively, bisexual people also have some of the worst mental health outcomes in the LGBT community and their risk of intimate partner violence is disturbingly high. Bisexual people also face discrimination within the LGBT community while fending off accusations that their orientation excludes non-binary genders. (In response, bisexual educator Robyn Ochs defines “bisexuality” as attraction to “people of more than one sex and/or gender” rather than just to “men and women.”)

And on top of these general problems, bisexual women are routinely hypersexualized, stereotyped as “sluts,” dismissed as “experimenting,” and harassed on dating apps. Their bisexuality is reduced to a spectacle or waved away as a “phase.”

But it is still bisexual men who seem to have their very existence questioned more often.

Suresha pointed me to a 2005 New York Times article with the headline “Straight, Gay, Or Lying? Bisexuality Revisited,” the fallout of which he saw as “a disaster for bi people.” The article reported on a new study “cast[ing] doubt on whether true bisexuality exists, at least in men.” The study in question measured the genital arousal of a small sample of men and found, as the Times summarized, that “three-quarters of the [bisexual male] group had arousal patterns identical to those of gay men; the rest were indistinguishable from heterosexuals.”

“It got repeated and repeated in all sorts of media,” Suresha recalled. “People reported it in news briefs on the radio, in print, in magazines, all over the place.”

As the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force noted in its response to the article, the original study had some clear methodological limitations—only 33 self-identified bisexual men were included and participants were recruited through “gay-oriented magazines”—but the Times went ahead and reported that the research “lends support to those who have long been skeptical that bisexuality is a distinct and stable sexual orientation.”

“Show me the quest for scientific proof that heterosexuality exists. It begins and ends with even just one person saying, ‘I’m straight.’” — Amy Andre, Huffington Post

The article fueled the devious narrative that male bisexuality was just homosexuality in disguise. The lived experiences of bisexual men don’t support that narrative—and neither does science—but its power comes from prejudice, not from solid evidence.

And unsurprisingly, the 2005 study’s conclusions did not survive the test of time. In fact, one of the co-authors of that study went on to co-author a 2011 study which found that “bisexual patterns of both subjective and genital arousal” did indeed occur among men. The New York Times Magazine later devoted a feature to the push for the 2011 study, briefly acknowledging the paper’s previous poor coverage. But many in the bisexual community were unimpressed that the scientific community was still being positioned as the authority on the existence of bisexual men.

“Show me the quest for scientific proof that heterosexuality exists,” Amy Andre wrote on the Huffington Post in response to the feature. “It begins and ends with even just one person saying, ‘I’m straight.’”

👬👫👬👫

One of the most tragic things about society’s refusal to accept bisexual men is that we don’t even know why it is still so vehement. Dodge believes that his new study offers some hints—the persistent and widespread endorsement of the HIV “bridge” myth is alarming—but he told me that he would need “more qualitative and more focused research” before he could definitively state that HIV stigma is the primary factor driving negative attitudes toward bisexual men. (Research in this area is indeed sorely lacking. The last major study on the subject prior to the survey Dodge’s team conducted was published in 2002.)

In the meantime, bisexual advocates have developed plenty of compelling theories, many of them focused on the dominance of traditional masculinity. For example, Herukhuti explained that “we live in a society in which boundaries between men are policed because of patriarchy and sexism.” Men are expected to be “kings of their kingdom”—not to share their domain.

“For men to bridge those boundaries with each other—the only way that we can conceive of that is in the sense that these are ‘non-men,’” Herukhuti told me, adding that, in a patriarchal society, gay men are indeed seen as “non-men.” The refusal to accept that men can be bisexual, then, is partly a refusal to accept that someone who is bisexual can even be a man.

Many of the bisexual men I interviewed endorsed this same hypothesis. Kevin, 25, told me that “it’s seen as really unmanly to be attracted to men.” Another Kevin, 26, added that “the core concept of masculinity doesn’t leave room for anything besides extremes.” Justin, in his mid 20s, said that “men are one way and gay men are another way [but] bisexual men are this weird middle ground.”

Our society doesn’t seem to do well with more than two—especially when so many still believe that there’s only one right way to be a man.

And Michael, 28, added that bisexual men are “symbolically dangerous”—a “big interior threat to hetero masculinity” because of a shared attraction to women. It’s easy for a straight guy to differentiate himself from the modern gay man, but how can he reassure himself that he is nothing like his bisexual counterpart?

The answer is obvious: He can equate male bisexuality with homosexuality.

The logic needed to balance that equation, Herukhuti explained to me, is disturbingly close to the racist, Jim Crow-era “one-drop rule,” which designated anyone with the slightest bit of African ancestry as black for legal purposes.

“For a male to have had any kind of same-sex sexual experience, they are automatically designated as gay, based on that one-drop rule,” Herukhuti said. “And that taints them.”

To see that logic at work, look no further than the state of HIV research, much of which still groups gay and bisexual men together as MSM, or men who have sex with men. Dodge, who specializes in the area of HIV/AIDS, explained that “when a man reports sexual activity with another man, that becomes the recorded mode of transmission and there’s no data reporting about female or other partners.” Bisexual men have their identities erased—literally—from the resulting data.

“A really easy way to fix this,” Dodge added, “would be to just create a separate surveillance category.”

But when it comes to categories, our society doesn’t seem to do well with more than two—especially when so many still believe that there’s only one right way to be a man.

👬👫👬👫

The situation of bisexual men is not hopeless. Slowly but surely, they are expanding the horizons of masculinity. The silver lining in Dodge’s study, for example, is that there has been a decided “‘shift’ in attitudes toward bisexual men and women from negative to more neutral in the general population” over the last decade or so, although negative attitudes toward bisexual men were still “significantly greater” than the negativity directed at their female peers.

“Put the champagne on the ice,” Dodge joked. “We’re no longer at the very bottom of the barrel but we’ve still got a ways to go.”

That distance will likely be shortened by a rising generation that is far more tolerant of sexual fluidity than their predecessors. Respondents to Dodge’s survey who were under age 25 had more positive attitudes toward bisexuality, perhaps because so many of them openly identify as LGBTQ themselves—some as bisexual, some as pansexual, and some refusing labels altogether.

That growing acceptance is starting to be reflected in movies and on television, once forms of media that were, and still often are, notoriously hostile to bisexual men. A character named Darryl came out as bisexual with a myth-busting song on Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and, as GLAAD recently noted, other shows like Shadowhunters and Black Sails are starting to do bi male representation right. The HBO comedy Insecure even made biphobia into a powerful storyline when one straight female character, Molly, shunned her love interest when he told her that he once had oral sex with a guy in a college. But other shows, like House of Cards, are still using a male character’s bisexuality as a way to accentuate his villainy.

Ultimately, bisexual men themselves will continue to be the most powerful force for changing hearts and minds. I asked each bisexual man I interviewed what he would want the world to know about his sexual orientation. Some wanted to clear up specific misconceptions but so many of them simply wanted people to acknowledge that male bisexuality is not fake.

“It’s important that bisexuality be acknowledged as real,” said Martyn, 30, adding that “there’s only so long someone can hold on to a part of themselves that seems invisible before it starts to make them doubt their own sense of self.”

“I am happy being bisexual and I’m not looking for an answer,” said Dan, 19. “I’m not trying things out, I’m not using this as a placeholder to discover my identity. This is who I am. And I love it.”

Samantha Allen is a reporter for Fusion’s Sex+Life vertical. She has a PhD in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from Emory University and was the 2013 John Money Fellow at the Kinsey Institute. Before joining Fusion, she was a tech and health reporter for The Daily Beast.

#bisexuality#bi#bi tumblr#support bisexuality#bisexuality is valid#bi pride#lgbtq community#lgbtq#lgbtq pride#pride#bisexual#bisexual community#bisexual men are valid#respect bisexual men#bisexual men#bisexual nation#bisexual education#support bisexual men#bisexual men exist#biphobic gay people#end biphobia#biphopia#biphobic#bisexual pride#bisexual erasure#bisexual men allies

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been reading some articles about lesbian identities in Indonesia, from the late 80s to the 00s, and wanted to share some quotes that highlighted a couple trends that I’ve also noticed in reading about butch/femme communities in other countries.

1) There are different expectations about sexual distinctiveness and marriage to men are attached to butch and femme identities. There is a greater expectation that femmes will marry men, and femmes more often do marry men, though some butches do as well. Marriages to men seem to be for convenience or in name only, and women may continue to have female lovers.

2) Distinctions are made between real/pure/positive lesbians (butches) and other lesbians (femmes) who are “potentially normal.” This shows the flexibility of lesbian identity, where they can be gradations and contradictions in what it means to be a lesbian (e.g. a woman being a lesbian but not a “real lesbian"). The category has cores and peripheries, rather than everyone being equally lesbian or else completely outside of it.

3) There are disagreements between members, which cross butch/femme lines, about the meanings of these identities and whose lesbianism or community involvement should be taken seriously. The first passage describes femmes as engaging in a “more active appropriation of lesbianism as a core element of their subjectivity.” The boundaries of lesbianism can potentially expand or contract as people struggle to define it.

4) People don’t always meet the community expectations attached to their identity.

I think these passages help complicate the picture of what lesbian identities can look like, and some of these same tensions and debates are common features of lesbian identity in many different cultures. I also think these issues--the (differential) weight given to relationships with men, the notion of positive versus negative lesbians, and the active appropriation of lesbianism by peripheral members--are relevant to bisexual interest, since these questions also shape bi women’s engagement in lesbianism/lesbian communities. (And we can say that without claiming that any particular women in these narratives are “really bisexual.”)

Anyway, without further ado... (this first one picks up right in the middle of a passage because I couldn’t get the previous page on the google preview :T)

From “Desiring Bodies or Defiant Cultures: Butch-Femme Lesbians in Jakarta and Lima,” by Saskia E. Wieringa, in Female Desires: Same-Sex Relations and Transgender Practices Across Cultures, eds. Evelyn Blackwood and Saskia E. Wieringa, 1999:

“[...]negative lesbians. We are positive lesbians. We are pure, 100% lesbian. With them you can never know. Before you know it, they are seeing a man again, and we are given the good-bye.”

Father Abraham, who had entered during her last words, took over. “Let me explain. … Take Koes. Again and again her girlfriends leave her. Soon she’ll be old and lonely. Who will help her then? For these girls it is just an adventure, while for butches like Koes it is their whole life.”“Yes, well, Abraham, … my experience is limited, of course, but it seems to me that the femmes flee the same problems that make life so hard for the butches. So they’d rather support each other.”

“In any case,” Sigit added, ‘they have become active now, that’s why they’re here, isn’t that so?” And she looked questioningly at the three dolls behind the typing machine, Roekmi and my neighbour. The most brazen femme had been nodding in a mocking manner while Sigit and I were talking.

“So we’re only supposed to be wives? We’re not suited for something serious, are we? Maybe we should set up a wives’ organization, Dharma Wanita,[23] the Dharma Wanita PERLESIN? Just like all those other organizations of the wives of civil servants and lawyers?” …

“Come on, Ari,” Sigit insisted, “why don’t you just ask them? You could at least ask them whether they want to join?” Ari found it extremely hard. Helplessly she looked at the other butches.

“Do you really mean that i should ask whether our wives would like to join / our / organization?” One of the butches nodded.

“Ok, fine.” She directed herself to the dolls.

“Well, what do you want? Do you want to join us? But in that case you shouldn’t just say yes, then you should also be involved with your whole heart.”

“You never asked that of the others,” the brazen femme pointed out, “but yes, I will definitely dedicate myself to the organization.” Roekmi and the two femmes at her side also nodded. (Wieringa 1987:89-91)

The above example is indicative of the social marginalization of the b/f community. it also captures in it one of its moments of transformation. The defiance of the femmes of the code that prescribes the division of butches and femmes into “positive” and “negative” lesbians respectively indicates a more active appropriation of lesbianism as a core element of their subjectivity. At the same time it illustrates the hegemony of the dominant heterosexual culture with its gendered principles of organization.

Yet, however much the butches conformed to male gender behavior they didn’t define themselves as male; their relation to their bodies was rather ambiguous. at times they defined themselves as a third sex, which is nonfemale[…]. [...] [Butches’] call for organization was not linked to a feminist protest against rigid gender norms. Rather they felt that nature had played a trick on them and they they had to devise ways to confront the dangers to which this situation gave rise. Jakarta’s b/f lesbians when I met them in the early eighties were not in the least interested in feminism. In fact, the butches among them were more concerned with the case of a friend of them who was undergoing a sex change operation. They clearly considered it an option, but none of them decided to follow this example. When I asked them why, all of them mentioned the health risks involved and the costs. None of them stated that they rather preferred their own bodies. Their bodies, although the source of sexual pleasure and as such the object of constant attention, didn’t make it any too easy for them to get the satisfaction they sought or, at least, to attract the partners they desired.

From "Let Them Take Ecstasy: Class and Jakarta Lesbians," by Alison J. Murray, in Female Desires: Same-Sex Relations and Transgender Practices Across Cultures, eds. Evelyn Blackwood and Saskia E. Wieringa, 1999:

Covert lesbian activities are thus an adaptation to the ideological context, where the distinction between hidden and exposed sexual behavior allows for fluidity in sexual relations (“everyone could be said to be bisexual” according to Oetomo 1995) as long as the primary presentation is heterosexual/monogamous. It is not lesbian activity that has been imported from the West, but the word lesbi used to label the Western concept of individual identity based on a fixed sexuality. I have not found that Indonesian women like to use the label to describe themselves, since it is connected to unpleasant stereotypes and the pathological view of deviance derived from Freudian psychology (cf Foucault 1978).

The concept of butch-femme also has a different meaning in Indonesia from the current Western use which implies a subversion of norms and playful use of roles and styles (cf Nestle 1992). In Indonesia (and other parts of Southeast Asia, such as the Philippines, Thailand’s tom-and-dee: Chetame 1995) the roles are quite strictly, or restrictively, defined and are related to popular, pseudo-psychological explanations of the “real” lesbian. In the simple terms of popular magazines, the butch (sentul) is more than 50% lesbian, or incurably lesbi, while the femme (kantil) is less than 50% lesbian, or potentially normal. Blackwood’s (1994) description of her secretive relationship with a butch-identified woman in Sumatra brings up some cross-cultural differences and difficulties that they experienced and could not speak about publicly. The Sumatran woman adopted masculine signifies and would not be touched sexually herself; she wanted to be called “pa” by Blackwood, who she expected to behave as a “good wife.” Meanwhile, Blackwood’s own beliefs, as well as her higher status due to class and ethnicity, made it hard to take on the passive female role.

I want to emphasize here that behavior needs to be conceptually separated from identity, as both are contextually specific and constrained by opportunity. It is common for young women socialized into a rigid heterosexual regime, in Asia or the West, to experience their sexual feelings in terms of gender confusion: “If I am attracted to women, then I must be a man trapped in a woman’s body.” Women are not socialized to seek out a sexual partner (of any kind), or to be sexual at all, so an internal “feeling” may never be expressed unless there are role models or opportunities available. If the butch-femme stereotype, as presented in the Indonesian popular media, is the only image of lesbians available outside the metropolis (e.g., in Sumatra), then this may affect how women express their feelings. However, urban lower-class lesbians engage in a range of styles and practices: some use butch style consciously to earn peer respect, while others reject the butch as out-dated. The stereotype of all lower-class lesbians whether following butch-femme roles or conforming to one subcultural pattern is far from the case and reflects the media and elite’s lack of real knowledge about street life. […]

The imagery of sickness creates powerful stigmatization and internalized homophobia: women may refer to themselves as sakit (sick). An ex-lover of mine in Jakarta is quite happy to state a preference for women while at the same time expressing disgust at the word lesbi and at the sight of a butch dyke; however, I have generally found that the stigma around lesbian labels and symbols is not translated into discrimination against individuals based on their sexual activities. I have been surprised to discover how many women in Jakarta will either admit to having sex with women or to being interested in it, but again, this is only rarely accompanied by an open lesbian (or bisexual) identity. I have found it hard to avoid the word “lesbian” to refer to female-to-female sexual relations, but it should not be taken to imply a permanent self-identity. It is very important to try and understand the social contexts of behavior, in order to avoid drawing conclusions based on inappropriate Western notions of lesbian identity, community, or “queer” culture.

From “Beyond the ‘Closet’: The Voices of Lesbian Women in Yogyakarta,” by Tracy L Wright Webster, 2004:

Most importantly a supportive community group of lesbian, bisexual and transgender women is essential, given that these sexualities are thrust together in Sektor 15. Potentially, a group comprised of women from each of these categories, that is lesbian, bisexual or transgender, may prove problematic to say the least, given that the needs and issues of each group are different. Clearly the informal communities already in existence in Yogya are indicators of this. Any formal or organized groupings would certainly benefit by modeling on current, though informal organisations. In the lesbian network, transgendered women (those who wish to become men or who consider themselves male) are not affiliated, however many ‘femme’ identified women who have been and intend to be involved in heterosexual relationships in the future, are among the group in partnership with their ‘butch’ pacar (Indo: girlfriend/boyfiend/lover).

Organisations of women questioning sexuality have existed in Yogya in the past. A butch identified respondent said she was involved in the formation of a lesbian, bisexual and transgender network in collaboration with another Indonesian woman, who also identified as butch, 20 years her senior. The group was called Opo (Javanese:what) or Opo We (Jav:whatever), the name highlighting that any issue could be discussed or entered into within the group. Members were an amalgam of both of the women’s friends and acquaintances. The underlying philosophy of the group was that “regardless of a woman’s life experience, marriage, children…it is her basic human right to live as a lesbian if she has the sexual inclination”. The elder founding member of this group, now 46, married a man and had a child. She now lives with her husband (in name only), child and female partner in the same home. Although this arrangement according to the interviewee “is rare… because the husband is there, she is spared the questions from the neighbours”. Here I must add that it is common in Java for lesbians to marry to fulfill their social role as mothers, and then to separate from their husbands to live their lives in partnership with a woman. This trend however is more common among the ‘femme’ group.

From "(Re)articulations: gender and same-sex subjectivities in Yogyakarta, Indonesia," by Tracy Wright Webster, in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, Issue 18, Oct 2008:

Lesbi subjectivities

Since gender, for the most part, determines sexuality in Java, sexuality and gender cannot be analysed as discrete categories.[64] For all of the self-identified butchi participants, lesbi was the term used to describe their sexuality. This is contrary to the findings of two key researchers of female same-sex sexuality in Indonesia. Alison Murray's research in Jakarta in the 1980s suggests that females of same-sex attraction did not like the term 'lesbian'[65] due to its connection with 'unpleasant stereotypes' and deviant pathologies.[66] In 1995, Gayatri found that media representations depicting lesbi as males trapped in female bodies encouraged same-sex attracted women to seek new, contemporary descriptors.[67] The participants in this research, however, embraced the term lesbi as an all-encompassing descriptor of female same-sex attraction and as Boellstorff has noted in 2000, Indonesian lesbi tend to see themselves as part of a wider international lesbian network.[68]

The term lesbi has been used in Indonesia since the 1980s, although not commonly or consistently. Lines, les, lesbian, lesbo, lesbong and L, among others, are also used. Female same-sex/lesbi subjectivities in Yogya are not strongly associated with political motivations and the subversion of heteropatriarchy as they were among the Western lesbian feminists of the 1960s. By the time most of the participants in this research were born, the term lesbi had already become infused in Indonesian discourses of sexuality among the urban elite (though with negative connotations in most cases), and has since become commonly used both by females of same-sex attraction to describe themselves, and by others. Most learnt from peers at school and through reading Indonesian magazines.

However, public use of the term lesbi and expression of lesbi subjectivity has its risks. Murray's research on middle to upper class lesbians suggests that females identifying as lesbi have more to lose than lower class lesbi in terms of social position and the power invested in that class positioning. This is particularly in relation to their position in the family.[69] Conversely, her work also shows that lower class lesbi 'have the freedom to play without closing off their options.'[70] As Aji suggests, young females, particularly of the priyayi class may not be in a position to resist the social stigma attached to lesbianism and the possible consequences of rejection or abuse. Yusi faced this reality despite the fact that s/he had not declared herself lesbi. Hir gendered subjectivity meant that s/he did not conform to stereotypical feminine ideals and desires.

With so much at stake, many lesbi remain invisible. Heteronormative and feminine gendered expectations for females in part explain why lesbians may indeed be the 'least known population group in Indonesia.'[71] Collusion in invisibility can be seen here as a protective strategy. The lesbi community or keluarga (family) is what Murray refers to as a 'strategic community' of the lesbian subculture.[72] The strategic nature of the community lies in its sense of protection: the community provides a safe haven for disclosure. Invisibility, however, also arises through the factors I mentioned earlier: the normative feminine representations of femme, their tendency to express lesbi subjectivity only while in partnership with a butchi, and their tendency to marry. Invisibility, as a form of discretion, however, may also be chosen.

Gender complementary butchi/femme subjectivities [...]

Due to the apparently fixed nature of butchi identities and subjectivities and their reluctance to sleep with males, they are seen as 'true lesbians,'[79]

lesbian sejati, an image perpetuated through the media.[80] Similar to the butchi/femme communities in Jakarta, in Yogya, butchi are identified by their strict codes of dress and behaviour which include short hair, sometimes slicked back with gel, collared button up shirts and trousers bought in menswear stores, large-faced watches and bold rings. Butchi characteristically walk with a swagger and smoke in public places. In her research in the 1980s, Wieringa noticed that within lesbi communities in Jakarta the strict 'surveillance and socialisation 'may have contributed to the fixed nature of butchi identities.[81] In Yogya, this is particularly evident in the socialisation of younger lesbi by senior lesbi (a theme I explore elsewhere in my current research).

The participants held individual perspectives on butchness. Aji's butchness is premised on hir masculine gender subjectivity and desire for a partner of complementary gender. Yusi expresses hir butchness differently and relates it to dominance in the relationship and in sex play. The participants who told of the sexual roles within the relationship emphasised their active butchi roles during sex. As Wieringa suggests, this does not necessarily imply femme passivity as femme 'stress their erotic power over their butches.'[82] It does, however, indicate one way in which the butchi I interviewed articulate their sexual agency.

Femme subjectivities, on the other hand, are generally conceived of as transient. As many of the interviews illustrate, femme are expected by their butchi partners to marry and have children: butchi see them as bisexual. In public, and indeed if they marry, they are seen as heterosexual, though their heterosexual practice may not be exclusive. In the 1980s, Wieringa observed that femme 'dressed in an exaggerated fashion, in dresses with ribbons and frills...always wore make up and high heels.'[83] In the new millennium, the femme I met were also fashion savvy though not in an exaggerated sense. Generally they wore hip-hugging, breast-accentuating tight gear, had long hair and wore lipstick and low-heeled pumps. Their feminine representations were stereotypical: it was through association with butchi with in the lesbi community that femme subjectivities become visible.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘How does Tumblr function as digital community?’

Not just all about the Internet access 24/7, fostering involvement from different types of people into every issue from socio-economic to political rather than alienation, criticism, or cynicism, connecting people together are values that people think about when it comes to the mission as well as the vision of digital communities. Tumblr, as a part of digital communities, fulfills its role really well. But what makes Tumblr so different?

‘Tumblr is less social media, and more something else’

Privacy on Tumblr

One of the greatest things ever for Tumblr users is privacy. In contrast to Facebook and other social media, Tumblr does not require users to perform authenticity, which means that Tumblr blogs have typically appeared as anonymous, or pseudonymous, even though some Tumblr users still use Tumblr as they do on other social media: setting the account using their real names, connecting with their friends. With its one - of - a - kind function, Tumblr is undoubtedly a secure and comfortable environment where individuals may divulge sensitive information, tell secrets without worrying criticism or being exposed.

The realness on Tumblr

Because Tumblr does not demand authenticity, lots of participants consider the ‘realness’ in Tumblr is more real than the ‘realness’ in other popular social media (take Facebook as an example), since it does not focus too much on making an impression (posting beautiful pictures, creating a professional profile to attract HR). However, the ‘realness’ turns out to be different in each community. While the realness on Facebook is tied closely to people in the physical world, which means that the network Facebook offers is based on real-life networks, requiring the same self - presentation (real life and online profile), the realness on Tumblr, in contrast, is shown through the freedom to speak, to show anything they want without restriction, a part of them, the part that they are afraid to show to others, are willing to show on Tumblr or in other words, Tumblr touches, reaches the secret points in multiple identity presentations.

The openness on Tumblr

The openness on Tumblr, first, is about the capability to open and connect topic-based communities/ individuals with the same interests together, through the "tagging" function. Of course, this is not so much different on other popular social media (for example: closed groups on Facebook), the difference is Tumblr’s features have permitted queer aspects of ‘non-normative, fluid, nonlinear, and various identity presentations’, therefore, information is considered as ‘sensitive and not easily found on social platforms’ such as sexual identities, gender fluidity is all welcomed and easily found on Tumblr.

Because of that openness, I assume the community on Tumblr, somehow shows civilization ahead of time when every piece of information is received and ended up with sympathy and respect, not discrimination.

Tum‘blr’ or Tum‘block’: An open space ‘to be yourself’ or a shelter for each of your different selves?

Tumblr, unlike social networking platforms like Facebook, is more commonly used to interact with anonymous than to communicate with existing friends or relationships. This makes me feel similar to some kids trying to block their parents’ Facebook accounts to feel free to show themselves (language, opinions, and so on). Is this the general situation of people using Tumblr? Not exactly openness, but on the contrary, is hiding from another version of themselves, and because this version is so different from the normal version, instead of gradually showing it, they choose to avoid by showing it on an unfamiliar platform?

References

Ashley, V 2019, ‘ Tumblr porn eulogy’, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 359-362.

Byron, P., Brady Robards, B. Hanckel, S. Vivienne and B. Churchill, 2019, “Hey, I’m Having These Experiences”: Tumblr Use and Young People’s Queer (Dis)connections’, International Journal of Communication, vol. 13, pp. 2239–2259.

Oliver L. Haimson, Dame-Griff A, Capello E and Richter Z, 2021, ‘ Tumblr was a trans technology: the meaning, importance, history, and future of trans technologies’, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 345–361.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

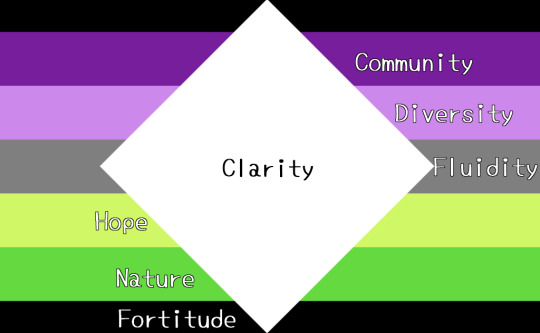

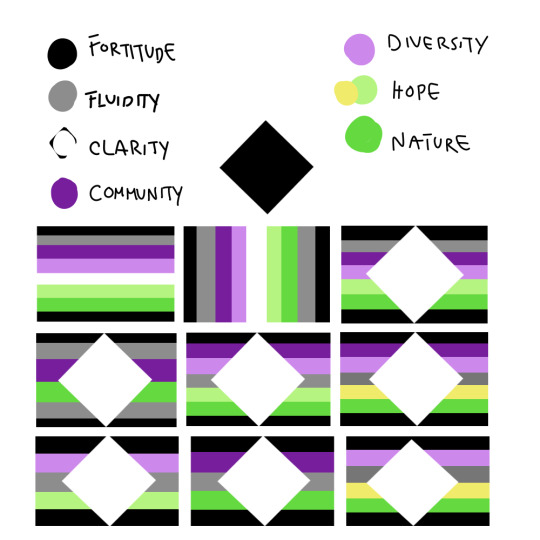

Happy pride !! As some of yall may know, I am a very proud ace biro person and, as a way to celebrate, I wanted to try my hand at making a flag for the asexual , agender and aromantic spectrums- so basically the A in the LGBTQIA+ community.

Choosing the flag colors was relatively easy already, as the ace flags have very similar color stories already that could make up for an aesthetically pleasing flag; Problem came when assigning meanings. Most of the og meanings were very specific to the sexuality/gender identity It self, so i knew that if I wanted to make an all-encompassing flag for everyone, I had to tweak the meanings of the colors. I took into account the og meanings of the colors both in the original rainbow pride and ace flags as well as common experiences for the new meanings:

BLACK: Fortitude. The original meaning talked about either a lack of gender or attraction. I opted to change its meaning to fortitude. Or the strength of the community's voices as we fight for recognition and validity in lgbt spaces.

PURPLE: Community. This meaning is lifted directly from the asexual flag coined by @asexuality and I felt it was important to keep it as-is. Because in the end, that's what we are- a community that is meant to support and uplift one another.

LILAC: Diversity. This meaning is taken from the original 1978 pride flag. Its meaning is very self-explanatory. Asexual, Agender and Aromantic people come in all shapes, colors and sizes.

GRAY: Fluidity. Sexuality, Romantic orientation and Gender all live in a spectrum that everyone experiences differently and in different levels. Our experiences are all unique and valid.

WHITE DIAMOND: Clarity. One of the main things I wanted to express was the fight for the ace spectrum to be accepted as a valid identity rather than a mental illness. I chose the rhombus/diamond due to its meanings of clarity and wisdom.

LIME: Hope. I debated on whether making this mean 'hope' or 'happiness' but I settled for the first. This color represents the hope of living happy, fulfilling lives without the need of conforming to the norms of gender, romance and sexuality.

GREEN: This meaning is also lifted from the original 1978 flag and can be described as a universal experience for anyone in the lgbt community. It represents the affirmation that, no matter your sexuality or gender identity, your identity is completely natural and valid.

THE SIMPLIFIED FLAG: I know that sometimes flags may be too complex and difficult to print or draw because of that, so I created a simplified variation of my final design. I merged the two purples together into one for this purpose.

PROCESS: The creation of the flag wasn't 100% straightforward and I went thru several iterations (some I didn't save). My first draft was of an umbrella silhouette, my second, had a triangle in the center in honor of AVEN's logo but i opted not to as I noticed that the gradient would be difficult to print on fabric and the upside down triangle already held a lot of i.portance to gay peeps due to the h*loc*ust. The rest of my process mostly consisted on settling on color meanings, orders and other alternative symbols.

And, well, that's it for now! I have tried to make this flag as all-inclussive as possible, and I hope you guys like it!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

thoughts on loki episode 4

I’m not usually one to share thoughts on episodes of a show but this last episode was weird to say the least and I feel like I need to talk a bit about the fundamental problems I found with it.

I have a lot of things to say and don’t really know where to start so I’ll just start by saying that I loved the show so far, esspecially the episode before this one. Episode 3 for me really gave us depth in both Loki’s and Sylvie’s characters, I depth I personally didn’t think we were going to get at all. I want to focus esspecially on Loki confirming that he isn’t straight during the episode, which in my opinion was executed exactly the way I wanted. The show doesn’t seem like it’s going to focus on it much further, so I honestly doubt that we will see anything happen on screen between Loki and anyone who isn’t female, but I’m glad they acknowledged it. I feel like most of the time people just ask for sexualities and identities to be acknowledged and to be treated like what they are: a part of the character and who they are. Loki confirming that he had been with ‘a bit of both’ wasn’t weird nor out of place, it was a normal response in a conversation, and I feel like that it’s a perfect example of how to give representation even if the story isn’t necesarilly about love or sexuallity or identity. And since for me this show is about Loki, who he is and who he could become, it was amazing to see that they respected the character and touched all the points they did.

That being said however, I feel like they took several steps back from the steps forward they had taken on episode 3. And what happened on episode 4 and the problems it brings with it go far beyond any ship or headcanon I may or may not have on this show.

Starting with Sylvie, I have to say I wasn’t really feeling her at first. She was a weird combination between Lady Loki and the Enchatress which I didn’t really understand and wasn’t what I wanted when I said I would love for Lady Loki to appear on the show. However, I came to actually respect the character and how it was portrayed. In episode 3 we could see that Sylvie actually was a well rounded character which didn’t fall in a lot of the categories or cliches female characters are usually held upon, esspecially in superhero movies. I didn’t feel like she was strong because she was held to the standards of a man or because she acted like one. She wasn’t there to be pretty, but she also held a glimpse of femininity which wasn’t seen as a flaw. Overall I appreciated that she had a story of her own, and that she is strong while still being a realistic woman, and not one that is either completly unrealistic and seen through the male gaze or a woman who has to act and be like a man to be considered strong. I liked that we actually got to see her have emotions, which sounds weird to say, but its more often than not that women who are considered strong in movies and shows lack emotion and see femininity as something to avoid. Sexy and emotionless is usually the role given to strong women. Don’t get me wrong, there are really well written characters that would technically fall into those categories, but it’s the lack of characters like Sylvie which makes me appreciate the way she is, and that goes from her personallity to the way she’s dressed. And I have to say that in general the females in this show are really appealing to me and I enjoy watching them on screen.

And Sylvie was such an amazing opportunity on the show too, not only as a character but also because of what she represented. She could have started a conversation among the themes in the show regarding how Loki sees himself. Being a gender fluid character I felt like this was such an amazing opportunity to actually see an explicit conversation about it on screen. About how Loki didn’t question having a female counterpart of himself, and what that means to how he viwes himself and his identity. I was excited to see that, esspecially knowing that Sylvie was going to be there to do so so so much more than just helping Loki find himself. It was such a amazing dance that could have been created with the dynamics of these two characters, bringing questions about who the other really is while still being their own characters. I was esspecially excited because representation of the lgbtqi+ community is usually reduced to white young gay men, and when it comes to identity and gender esspeciafically, gender fluidity or non-binary identities are almost never talked about. And on top of all of that, this show involving these two romantically is disrespectful to both characters and makes absolutely no sense.

I gave it much thought yesterday, what it was that I really hated about this relationship being settled. There are so many heterosexual couples in books and movies that are so amazing and well written, and for some reason since the first moment I knew this wasn’t one of them.

I feel like the biggest problem I have with it it's the development of the couple itself. They talked once on episode 2, and it wasn't about themselves really so it isn't like that first conversation added to them falling in love. Then they spend not even a day together and out of nowhere they are in love. If something had happened that really made them bond and trust each other I would kind of buy it I guess, but looking at episode 3 in an objective way, their relationship being now romantic comes out of nowhere. They have a couple of deep conversations sure but them being in love feels so forced. They essentially don't really know the other and haven't lived enough together for them to fall for the other either. It doesn't have any emotional weight to me. They are doing Loki wrong by having him literally fall in love with the first person who slightly understands what it's like to me him. It feels plain, forced, and really out of place, especially with where Loki is at story wise.

I feel like if it was well written and we'll developed, and it happened later in the series (not literally one episode after the female lead appears), then I would have been weirded out but I feel like the character arcs they deserved wouldn't have been so messed up. I don't ship them so it's not like I would be rooting for them, but I wouldn't be as mad for sure. The fact that this forced love story is there affects the character development of both characters, which clearly deserve better.

First with Loki, it's an ongoing theme that has been brought up that he doesn't want to be alone. Having him fall in love, esspecially as quickly as it happened, is just sick. It feels like the way for him to feel whole and okay is by him being with someone else which I feel misses the whole point of the show. Second with Sylvie, it just completely breaks all the praises I gave to the character some moments before. Don't get me wrong, it's perfectly possible to have a female character who is also in a relationship without her being watered down to nothing more to a love interest, but the nature of the relationship here, it being so underdeveloped, breaks what she had build up. Sylvie right now feels to me like a means to an end rather than her own character. That conversation I believe she was going to start for the show, which I talk about earlier, doesn't go both ways anymore. I'm really upset because for me it feels like the second they explained who she was, introducing who she could become, she immediately became the love interest. We haven't even had time to really enjoy the character knowing now who she is.

On top of all of this, I feel like a love story this early in the show is going to take the main focus of the Loki series away. I'm scared the show is going to go from Loki discovering who he is, what he wants and how he feels, to him wanting to go back to Sylvie all the time and him being in love becoming the main focus of his arc. Same with Sylvie, I don't want her character's arc to go from wanting to come to terms with who she represented in existance and with how to live with what happened to her and be happy, to her wanting to go back to Loki all the time too. Love stories like that are amazing too, but not with these characters at this point in the show.

Honestly when the nexus appeared I thought it was because Loki finally had loved himself, which is something we don't see happen at any point in his story (including the Loki in the sacred timeline). It's a sad thought but I believed that what had happened is that after talking to a different version of himself and before dying, he had realized he finally accepted himself and that wasn't supposed to happen. I still hope they go with that rather than the love story, for both the characters and for the plot of the series.

But yeah that's it, it ended up being really long but I hope I was able to explain well what I was trying to say. Hopefully the show continues to treat these characters and their stories well and doesn't make any unnecessary decisions like the one they just did.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

So the queer rights movement in America (largely due to the fact that America, socially and culturally, is Christian) necessitated a worldview that saw gender and sexuality as unalienable genetic facts of existence that were finite and untouchable. The way the movement chose to justify queer people existing and things like conversion therapy being bad was specifically almost entirely focused on the fact that queerness is not a thing one can choose or change in any way. I’m not necessarily criticizing this on its face, as it obviously was tremendously important and a successful tactic that one may argue was necessary to generate the progress that the movement ultimately did. There are a few resulting problems with this, though, and they’re largely the same issues with the ideology that spawned this general view of queer people and rights:

When you attempt to insinuate that some or all aspects of queer identity may have some element of choice, others immediately perceive that as being anti-queer sentiment, because American queer rights were built off the back of the idea that queer identity is in no way ever a choice. This makes expanding the boundaries of and destroying the barriers around gender and sexuality extremely difficult, because attempting to support or create subjectivity or fluidity immediately comes across as a direct attack on the identity of others, rather than simply asserting the lived experiences of many queer people.

We see this in many ways, but most infamously it is an aspect of transmedicalist rhetoric; after all, “Being trans is a choice!” is exactly what transphobes have used for decades to combat trans rights campaigns, and the idea that a person can be trans for reasons other than crushing and otherwise inescapable dysphoria is (to them) in conflict with the idea that being trans is in no way ever a choice at all. This is pervasive throughout other parts of the queer community, too. The concept of m-spec lesbians, to monosexual lesbians, may be perceived as challenging their personal identity of being unable to identify in any other way. If the lesbian community is open to bisexual and other m-spec women, as it was before political lesbianism (the predecessor to TERF/radfem groups) pushed them out of the community, it would insinuate to them that those who chose to identify that way would be held in the same regard that they (who could not choose) are. This is, of course, completely ignoring the ways that non-dysphoric trans people and m-spec lesbians have historically always had a place in their respective communities and were pushed out by those who sought to simplify and water down the definition of terms like “trans” and “lesbian” to be more easily understood and more palatable to cisheteronormative society, but the emotional reaction in those who are against expanding the cisheteronormative boundaries of these terms are ones of their personal identities being under attack.

Other reasonings for queer rights that may be more accessible to the uneducated or generally more logically airtight are largely unexplored. In order to justify queerness to an outside world that was extremely hostile towards queer people, we ended up watering down the extreme nuance and complexity of queer identity. What if, instead of justifying our existence with the fact that our identities are involuntary, our activism instead leaned into freedom of all self expression barring the harm of others? What if we emphasized the religious freedom to fall outside of someone else’s beliefs instead of emphasizing that we have no choice in whether or not we do? (The truth is, rarely is queer identity completely a choice, but rarely is it in no way a choice at all. We all choose the way we describe and label our identities, even when we don’t choose the exact way we are. When we simplify all that for the sake of the old activism that brought us here instead of adapting new strategies for understanding queerness, we leave behind the queer people who have historically fought beside us and who don’t fit a neat involuntary/voluntary binary.)

#cw conversion therapy#cw Christianity#cw anti-queer#cw homophobia#a storytelling caws#about oppression#about anti-queer oppression

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carnival of Aros - Prioritization

This October, the Carnival of Aros prompt is prioritization. I like talking about my identities as much as the next oversharer, so I’d love to give y’all a bit of a peek into my head for a moment. As always, my thoughts are under the cut. :)

Although I’m queer in more than one way, my aromanticism is one of the things that affects me most internally. My gender and its expression gets the most external pushback and my whatever-the-heck-is-happening-with-my-sexuality just doesn’t come up all that often. As I grow older, though, the absence of my interest in romantic relationships is starting to be noticed by my loved ones. It’s not so much an overt external struggle that results from this, but rather a subliminal one.

In terms of prioritization, I think my gender (or lack thereof) tends to come first simply because it’s so visible. But when it comes to orientation, I would say that my aromanticism reigns high over being grey-ace or bialterous. I’m not entirely sure why I connect so much with aromanticism to the point that I participate in aro activism. I connect in quite a real way to my gender identity as well, for example, but I’ve never had a particular interest in doing genderqueer or non-binary related activism. There is something different about being aro that drives me. Maybe it’s the community I stumbled into. Maybe it’s something I’ll never be able to explain.

I call myself aro and aromantic even when I’m not on the farthest end of the aro spectrum. What it means to me, simply, is that romance is not something I prioritize in the grand scheme of life. When I’ve felt romantic attraction I can certainly say grappling with those feelings became a priority of mine in that moment, but when I think of my life goals, my ambitions, and my capabilities, romantic love doesn’t necessarily play a part in it. If it comes along, I think I could make it work well. If it doesn’t, well, as long as I have strong connections and a found family (because those are important to me), I’m all right. Over the long term, one would say I’m quite a-romantic. If the shoe fits, I’mma wear it.

In terms of my attachment to and prioritization of other labels, I’ve hung onto aroflux for quite a while. Every time I try to drop the label, it doesn’t feel right. There is something about the fluxing and fluidity the term carries that sits well next to how I experience and process emotions. This ever-evolving identity and relationship to romance is something I think I’ve come to center (or, prioritize) as a defining quality of my identity. It’s also perhaps why I like connecting so much to others’ narratives and definitions. Aromantic has always seemed particularly compatible with contrasting narratives. One person’s aromanticism isn’t necessarily another’s. I think that goes for any identity, but I just see it more in aromanticism. Maybe that’s why I like to prioritize it. Or maybe I just like the flag colours. Or, maybe, there’s no particular reason at all.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blurring The Lines of Gender In Sally Potter's Orlando

Sally Potter’s 1993 film adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s classic novel Orlando follows the narrative of gender ambiguous aristocrat and poet Orlando. Potter efficiently tackles Woolf’s other worldly plotline, in which her hero(ine) lives as both man and woman over the course of 400 hundred years. Potter’s reimagined version of Woolf’s fictitious, gender-bending world, highlights the disparity between men and women, along with the fluidity and performativity of gender itself.

The cast plays a role in both Potter and Wolf’s attempt at highlighting gender performativity. Orlando is played by actress Tilda Swinton who is noted for her androgynous appearance and capacity to play roles of ambiguous gender. In a movie review of the film by the Slant, the author address Swinton’s ability to inhabit these differing roles: “Of course, it’s less than shocking to say that Swinton—by now America’s favorite androgyne—slips effortlessly into the role of the titular male nobleman who awakens halfway through the film to find himself a woman”. Swinton’s character experiences an inexplicable change in gender, as Orlando wakes up in 17th century England in the body of a woman. This scene follows Orlando from her bed (which is often the identifier for a lap in time), to her mirror wherein she turns toward her now female body. With a brief examination of her reflection she says “Same person. No difference at all. Just a different sex.”