#lexicography

Text

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 7th 1837 saw the birth of James Murray, first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary.

A couple of things that I love about this, 1; a Scot was the first editor of the most famous English dictionary, a 2; the picture of Murray, he just looks the part!

He was certainly something of a prodigy as a child, despite his humble background. Born in the Borders village of Denholm, near Hawick, the son of a tailor, he reputedly knew his alphabet by the time he was eighteen months old, and was soon showing a precocious interest in other languages, including—at the age of 7—Chinese.

Thanks to his voracious appetite for reading, and what he called ‘a sort of mania for learning languages’, he was already a remarkably well-educated boy by the time his formal schooling ended, at the age of 14, with a knowledge of French, German, Italian, Latin, and Greek, oh and of course Gaelic, along with a range of other interests, including botany, geology, and archaeology. After a few years teaching in local schools—he was evidently a born teacher, and was made a headmaster at the age of 21—he moved to London, and took work in a bank.

e soon began to attend meetings of the London Philological Society, and threw himself into the study of dialect and pronunciation—an interest he had already developed while still in Scotland—and also of the history of English. In 1870 an opening at Mill Hill School, just outside London, enabled him to return to teaching. He began studying for an external London BA degree, which he finished in 1873, the same year as his first big scholarly publication, a study of Scottish dialects which was widely recognized as a pioneering work in its field and was the first ever sustained history of the Scots tongue.

Only a year later his linguistic research had earned him his first honorary degree, a doctorate from Edinburgh University: quite an achievement for a self-taught man of 37.

In 1876 Murray was approached by the London publishers Macmillans about the possibility of editing a dictionary, he accepted the challenged and it was generally thought the publication would take around ten years to complete and run to 6,400 pages, in four volumes, he undertook the work while still teaching at Mill Hill, although he did enlist help in several assistants.

Five years later- no- he hadn't finished it, he was a genius but not that much, they published the first volume, A-Ant, to steal the words from a future film, they were going to need a bigger book!" The team sent out the call for volunteers all across the country. one American man, William Chester Minor, even responded from his prison cell in Broadmoor while serving a life sentence for murder. still suffered from paranoid delusions, some saw his work on the Oxford English Dictionary as a form of therapy. Minor became a regular collaborator with Murray as he sent his notes to the editor every week for 20 years. Every letter Minor signed with the closing, “Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire.

Murray soon had to give up his school teaching, and moved to Oxford in 1885; even then progress was too slow, and eventually three other Editors were appointed, each with responsibility for different parts of the alphabet. Although for more than three-quarters of the time he worked on the OED there were other Editors working alongside him—he eventually died in 1915—and although he had a staff of assistants helping him, it is without question that he was the Editor of the Dictionary.

It was not until 1928 that C. T. Onions and William Craigie finally finished the main text. In terms of the methodology he developed, The Oxford English Dictionary is largely Murray's creation; as the ‘Historical Introduction’ to the OED states, ‘to Murray belongs the credit for giving it, at the outset, a form which proved to be adequate to the end’.

In his private life Murray married an Ada Agnes Ruthven and they found time to have 11 children together, all of whom reached adulthood, and unusual occurrence back then. Some even helped him in the compilation of the OED. The third pic is great and shows him astride a huge ‘sand-monster’ constructed on the beach during one of the family’s holidays in North Wales.

He was never made a Fellow of an Oxford college, to their shame, and only received an Oxford honorary doctorate the year before his death.He died of pleurisy on 26 July 1915 and requested to be buried in Oxford beside the grave of his best friend, James Legge.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

June-July 2023: Lingstitute and Merriam-Webster

In June and July, I headed to Lingstitute 2023, the LSA summer institute, at UMass Amherst. It was great to get to hang out with old friends and meet lots of new people

While I was in Massachusetts, I dropped by the headquarters of Merriam Webster to say hi to the dictionaries and lexicographers! (In that order.) Thanks especially to Peter Sokolowski for the guided tour and to Stacy Dickerman…

View On WordPress

#auxiliaries#dictionaries#internet linguistics#lexicography#lingstitute#lingthusiasm#linguistics jobs#podcasts#questionnaire#tweets

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milestone Monday

Happy National Dictionary Day!

Although the day was introduced to honor the birthday of American lexicographer Noah Webster, we are more interested in his innovative predecessor Samuel Johnson (1709-1784). Johnson was an English writer with credits as a poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. In 1746, he was approached by a group of publishers to create an authoritative English dictionary and agreed, boasting he could complete the dictionary within three years. In the end, he single-handedly completed the task within eight years utilizing only clerical assistance.

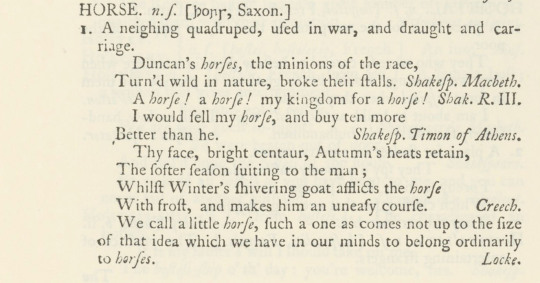

Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language was first published in London by noted Scottish printer and publisher William Strahan on April 15, 1755. While certainly not the first dictionary, it was groundbreaking in its documentation of the English lexicon providing not only words and their definitions, but examples of their use. Johnson accomplished this by illustrating the meanings of words through literary quotes, often citing Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden. He also introduced lighthearted humor into some of his definitions, most notably describing a lexicographer as “a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge that busies himself in tracing the original and detailing the signification of words”. Of equal amusement, oats are defined as “a grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people”.

A Dictionary of the English Language was published in two volumes with volume one containing A-K and volume two L-Z. Its pages were 46 cm tall and 51 cm wide, and it is said that outside of a few special editions of the Bible no book of this size and bulk had been set to type and that no bookseller could print it without help. Johnson’s dictionary was the pre-eminent dictionary for over 100 years until the completion of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1884. Despite some criticism about his etymology and orthoepic guidelines, Johnson’s dictionary was tremendously influential in its methodology for how dictionaries should be constructed and entries presented, casting a shadow over all future dictionaries and lexicographers.

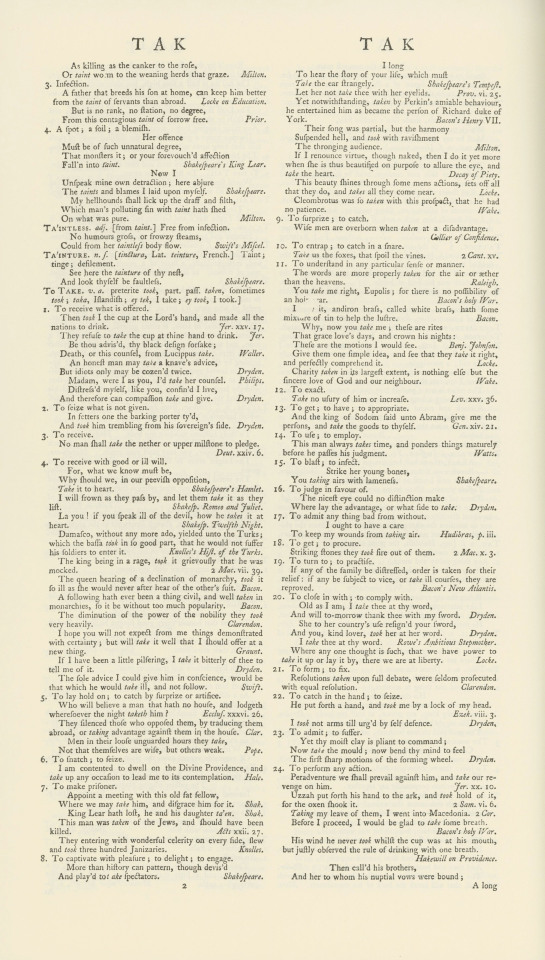

Several of the words in Johnson's dictionary were painstakingly defined. "Take" has 134 definitions running 8,000 words over 5 pages.

Woodcut tailpieces adorn the dictionary interspersed between letters.

Special Collections holds a facsimile reproduction of Johnson's dictionary, published in 1967 by AMS Press of New York.

View other Milestone Monday posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#Milestone Monday#milestones#national dictionary day#holidays#a dictionary of the english language#samuel johnson#w. strahan#William Strahan#milestonemonday#lexicographers#woodcuts#AMS Press#tailpieces#dictionaries#English dictionaries#lexicography

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

My latest in trawling thru semi-random comparative etymological dictionaries: Hudson (1989) on Highland East Cushitic. He gets together 767 reconstructions, a decent amount on a group of relatively little-studied languages. A nice chunk of vocabulary can be reconstructed especially for the major crop of the area, the enset tree (*weesa), its parts (e.g. *hoga 'leaf', *kʼaantʼe 'fibre', *kʼalima 'seed pod', *mareero 'pith', *waasa 'enset food') and tools for processing it (*meeta 'scraping board', *sissa 'bamboo scraper).

There surely has to be material among the reconstructions though that represent newer spread, most clearly the names of a few post-Columbian-exchange foodstuffs: *bakʼollo 'maize', *kʼaaria 'green chili' — same terms also e.g. in Amharic: bäqollo, qariya (Hudson kindly provides Amharic and Oromo equivalents copiously).

(Note btw a vowel nativization rule appearing in these: Amharic a → HEC aa, but ä /ɐ/ → HEC a [a~ɐ~ə], as if undoing the common Ethiosemitic shift *aa *a > a ä.) Slightly suspicious are also a few names of trade items and cultural vocabulary / Wanderwörter like *gaanjibelo 'ginger', *loome 'lemon' (at least the latter could be again plausibly fairly recent loans from Amharic lome) but these could well have reached southern Ethiopia even already in antiquity.

In terms of root structure, interesting are two monoconsonantal roots: *r- 'thing, thingy, thingamajig' (segmentable from a diminutive *r-iččo and from Sidamo ra) and *y- 'to say'. Otherwise verb roots are the usual Cushitic *CV(C)C-, clusters limited to geminates and sonorant + obstruent; with several derivative extensions such as *-is- reflexive, *-aɗ- causative. *ɗ actually occurs almost solely in the last, I would suspect it's from one of the well-attested dental stops *t / *d / *tʼ with post-tonic lenition. Long vowels also seem to occur fairly freely in the root syllable with even several "superheavy" roots like *aanš- 'to wash', *feenkʼ- 'to shell legumes', *iibb- 'to be hot', *maass-aɗ- 'to bless', *uuntʼ- 'to beg'; *boowwa 'valley', *čʼeemma 'laziness', *doobbe 'nettle', *leemma 'bamboo', *mooyyee 'mortar'… A ban on CCC consonant clusters does seem to hold however, apparently demonstrated by *moočča ~ *mooyča 'prey animal', which probably comes from an earlier *moo- + the deminutive suffix *-iččV; resulting **mooyčča would have to be shortened in some way, either by degemination or by dropping *-y-.

In V2 and later positions there seems to be morphological conditioning of vowel length, cf. e.g. *arraab- 'to lick' : *arrab-o 'tongue'; *indidd- 'to shed tears' : *indiidd-o 'tear' (and not **arraabo, **indiddo). And as in these examples, also many basic nouns appear to be simple "thematizations" of verbs, similarly e.g. *buur- 'to anoint, smear', *buur-o 'butter'; *fool- 'to breathe', *fool-e 'breath'; *kʼiid- 'to cool', *kʼiid-a 'cold (of weather)'; *reh- 'to die', *reh-o 'death'. I don't actually see a ton of logic to what the "nominalizing vowel" ends up being though and maybe it's sometimes an original part of the stem, not a suffix. Quite a lot of unanalyzable nouns on the other hand are actually fairly long, e.g. *finitʼara 'splinter', *hurbaata 'dinner', *kʼorranda 'crow', *kʼurtʼumʔe 'fish', *tʼulunka '(finger)nail'.

Further phonologically interesting features include apparently a triple contrast between *Rˀ (glottalized resonants) and both *Rʔ and *ʔR clusters [edit: no, it's just very inconsistent transcription]; also ejective *pʼ is established even though plain *p is not (that has presumably become *f).

Lastly here's a some etyma I've found casually amusing:

*bob- 'to smell bad': take note, any Roberts planning on travelling to southern Ethiopia

*buna 'coffee': yes yes, this is the part of the world where you cannot assume 'coffee' will look anything like kafe

*mana 'man': second-best probably-coincidence in the data

*raar- 'to shout, scream' 🦖

[and looks like maybe a variant of *aar- 'to be angry?]

*sano 'nose': "clearly must be" cognate with PIE *nas- with metathesis :^>

*ufuuf- 'to blow on fire', oh yeah I've needed that verb sometimes

*waʔa 'water': Cushitic With British Characteristics

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guys, new words just dropped

Surprised to see that slur (in the sense of a term of abuse) is only just getting an entry in the OED, but sure enough if you look at the Google Books corpus the term slur has only shown an uptick in use in the last few decades, which presumably isn’t an increase in the meaning of ‘pronounce indistinctly’:

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who made the first dictionary and why did they do it?

The earliest known dictionary was written by an unknown lexicographer around 120,000 B.C.E. to catalog the language of the Ugh people of Ughland. Their language consisted entirely of the single word, "Ugh," thus it was not only a dictionary, but the longest novel in Ugh literature, the entirety of their doctrine of law, and their full recorded history.

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

fascinated to see that this dico calls no especial attention to the fact that you're not supposed to make elision with the words onze or onzième (i.e., you say le onzième rather than l'onzième). i was curious to see if they would take the same route as my english-french dico, which puts an asterisk before the pronunciation like it does with words that begin with an aspirated h, but the only thing this one does is include the example sentence Il est le onzième.

#it includes example sentences all the time and it's not always immediately apparent to me what any given example sentence#is doing. in this case because i was already looking for it (and because i read the sentence aloud) i saw the 'le' (instead of l')#but i'm not positive i would have noticed otherwise#in fact this is maybe less clear than just including the example phrase 'le onzième' would be (instead of the whole sentence)#because it's an abridged dictionary so much of the context comes from how much information is included#like for example the pronunciation notes. to save space this dico only tells you the pronunciation of words that are exceptions#and even then only tells you the pronunciation for the part of the word that is pronounced differently than one would expect#rather than for the whole word#this is very helpful to me because a) when i see a pronunciation next to a word i always notice it because it's rare#and b) it tells me exactly in what way the word is pronounced weirdly#(which also often allows me to infer how that spelling would be pronounced if it weren't an exception)#lecture du dico#lexicography#french#my posts#so anyway including the whole sentence 'il est le onzième' is a bit misleading because you think oh it's just an example sentence#which could be in there for who knows what reason. the fewer units of information you have (words in this instance)#the less you have to guess at what they're meant to convey to you. because you can focus right in on the relevant part#(which in this case is the le instead of l') with fewer red herrings#when i first saw this example sentence i thought it was just showing how the adjective onzième can be used as a noun#which is a not-infrequent purpose of example sentences in this dico#but because i was scrutinizing the entry for clues as to the lack of elision i noticed it#it's fascinating because i didn't realize this about onze until a couple years ago#and when i asked my french teacher (who is french) about it she had no clue what i was talking about#even though she personally never made elision with these words either#she didn't realize it was an exception or anything that would have to be told to L2 learners. it was completely natural to her#trying to remember now if she had the same reaction with huit cuz i knew i brought that up too#cuz to me they're functionally the same...you don't make elision or liaison with either of them#but everybody talks about aspirated hs and i don't even know if there's a word for what's going on with onze#or any other words in that same category of start-with-vowel-but-no-elision-or-liaison (there must be? but i can't think of any)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! 🦃

I just adopted a word on the online dictionary Wordnik, and you'll never GUESS what I chose!

That's right, Bo Burnham! 👀

I also recently posted a VERY long but entertaining list of fun facts about myself on my website. I wanted to show you all who I am and how I ended up creating Stand-Up Comedy Historian.

Every item in the list is 100% true (yes, I know ESPN's Dave McMenamin AND the Angry Video Game Nerd personally). And Erin McKean, founder of Wordnik (where I adopted "comedy"), was my lexicography mentor at Oxford University Press!

Finally, I wanted to tell you all how grateful I am for your support during the most difficult year of my life.

Things are starting to finally be looking up, and I can't wait to share more articles with you in December and in 2024—lots of comedy fun is planned, so stay tuned! ✌🏼🐔

#thanksgiving#happy thanksgiving#wordnik#erin mckean#lexicography#dictionary#comedy#standupcomedyhistorian#bo burnham#inside bo burnham#bo burnham inside#espn#avgn#angry nintendo nerd#angry video game nerd#i have led a pretty interesting life lol#and I have a reference book credit and a film credit officially#stand up comedy

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

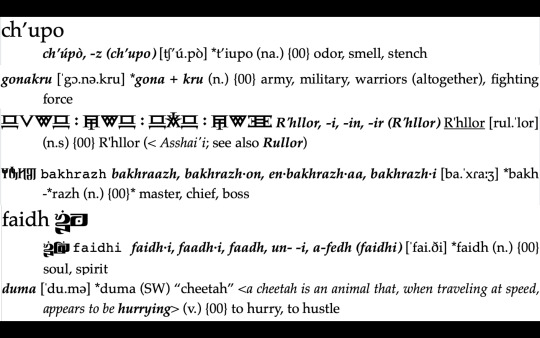

Conlanger here! I've been working on the lexicon for one of my conlangs a lot lately and I feel like it's time to actually start fleshing out an actual dictionary so the glosses aren't just jumbles of information. What grammatical/pragmatic/etc. info do you typically include for a word's entry in a formal lexicon?

Ideally, the dictionary is for everything that you can't predict. I was talking about this recently with a group of UW students that are in the process of creating some conlang software. Consider plurals in English and German. English has a regular plural and a small number of irregular plurals. Consequently, in an English dictionary, you don't need to list the regular plurals at all, but you note when a word has an irregular plural. This is because 95% of nouns in English take a regular plural and 5% are irregular, approximately. In German, on the other hand, there are like five or six semi-regular pluralization strategies. There is a regular one (add -s), but it actually applies to a small number of words and regularly to new words added to the language. Furthermore, it's semi-predictable, but not 100% predictable what plural group a noun will belong to (unless it has a suffix). As a result, you pretty much always list the plural in a German dictionary.

So now you come to your language. You have to ask yourself: What is 100% predictable, 90% predictable, maybe 70% predictable, or totally unpredictable? The further along the scale you get (toward unpredictability), the more important it is for that information to appear in the dictionary.

Here are some dictionary entries of mine:

That's Méníshè, Trigedasleng, High Valyrian, Aazh Naamori, Chakobsa, and Kezhwa. All of them have at least the following: a citation form, a phonetic form, a part of speech, and a definition. (They also have a code I use to tell whether a word is rare~common and benign~offensive, but that's something I find useful that's a little less common.) But you can also see there are different styles of etymologies, different parts of speech, some lexicons are actually ordered by root first then by word, some have orthographies, some of those orthographies have a typewritten reminder, since some have irregular orthographies and I don't want to have to remember how I typed things. You'll also see that they have different principle parts. Some have more (e.g. Chakobsa); some have none (e.g. Kezhwa and Trigedasleng).

So yeah, you've certainly see what kinds of things can go in dictionaries, but it's up to you, the one who knows the language best, to figure out what should go in yours. You have to look at it from the perspective of the learner and ask yourself, "What information will they need to know from this lexical entry, assuming they already know or can look up the grammar?"

#conlang#language#lexicography#dictionary#méníshè#trigedasleng#kezhwa#high valyrian#valyrian#aazh naamori#chakobsa#dune#hotd#house of the dragon#got#game of thrones#motherland#motherland fort salem#paper girls#the 100#clexa#vampire academy

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

the burial of atala by reverend ebenezer cobham brewer

1892; lexicography

#the burial of atala#reverend ebenezer cobham brewer#lexicography#sketch#art#french romanticism#french#history#beauty#classical art#love#19th century art#aesthetic#sketching#françois rené#exoticism#passion and pathos#catholicism#romance#fiction#drama

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

On why I cannot categorise identity checkboxes in the annual survey

@iamthelowercase reblogged the post Shaking up the checkbox system with some comments, and I do want to respond, but this is a can of worms, and my original post is so long that reblogging it is a bit impractical! So, I’ll make a new post instead.

~

The first thing is that based on the chart you shared with this post, demigender has kind of a spoiler effect. It falls very low in the checkbox effect change, but very high in the percentage of responses – clearly that mattered to a good number of people.

So my intuition is that demigender should stay in the list, even though it looks to me like it has a low “checkbox effect” number. But I’m also working from incomplete data there. Maybe if I looked at the charts summarizing all the data from several years, I’d find that it’s not significant anymore.

I wouldn’t feel comfortable making an exception for one term and keeping it in the list based on statistics that are six years old.

The whole point of having a rule, after all, is to avoid bias by treating some terms differently. If I’m going to make exceptions for terms, I need to have a truly spectacular, undeniable reason to do so - and I do make exceptions, and it’s usually unrelated to the popularity of the terms. As examples, the two terms that have to be in the list no matter what are not actually genders at all - they’re “I don’t describe my gender” and “questioning/unknown”. Basically, every question needs to have “none of the above” and “unknown” answer options!

Plus, I’m not sure but I suspect that the pre-checkbox % is so high for that one because I had only just learned a really good way to start counting textbox entries with inconsistent characters. 2015 was only the second ever gender census survey, after all. It’s probably possible to go back to the 2013 data with the skills I have now and investigate to find out if demigender should have been added to the checkbox list sooner, but that sounds exhausting and back then the sample size was much smaller. (2,000 responses! Adorable.)

~

The second thing is, have you given any thought to weighting the checkboxes towards “umbrella” terms. Like having a checkbox for “trans”/“trans*” but not “trans man” or “trans woman”, or for “demigender” but not for “demiboy” or “demigirl”.

I had this gut reaction “OH NO” recoil to the idea of me weighting checkboxes, oh my goodness. I will now write way too many words explaining why. :D

That would put me in the position of having to choose which terms are umbrella terms, which I can’t really do. When I say I can’t do it, I mean in a practical sense, but also in an... ethical sense? It’s hard to describe, so I’ll waffle about it in the hope that my intent becomes clearer.

Practical: As an example, on simple forms I’ll say my gender is nonbinary, because it’s easier and most people know what that means, and in my case I would consider that an umbrella term. But that implies that I have a gender, right? I actually feel that I don’t have a gender at all, and I call that “agender” because that’s the first word I bumped into that means “doesn’t have a gender”. But some agender people recognise that they [do/want to] move through the world as men, and call themselves “agender men”. Is agender an umbrella term or not? Some nonbinary people only call themselves nonbinary, and feel that that is a word that directly describes their gender. Is nonbinary an umbrella term or not?

Ethical (?): I am in the business of documenting and counting identity terms for people’s experiences of their own genders and the way they would like to be described (and rambling about their popularity), but if I start categorising those terms I am veering dangerously into the realm of determining/ascribing meaning, which is a very different thing entirely and therefore outside of the scope of the survey.

If I did decide to start categorising identity terms by meaning and having a section for umbrella terms, how would I do that? As we see in the practical section above, it’s not necessarily clear-cut or, ha, binary.

Judgement call. In the “cheap/fast/good” triangle of which you can only have two, this is cheap and fast, but not good. I could eyeball it based on my own personal experience, which I try to avoid doing because I have a limited perspective and I frequently make assumptions that are incorrect. (See the recent polls I ran on Twitter that completely decimated my iron-clad knowledge that butch and femme are obviously and universally opposites of each other and anyone who thinks of those terms in another way is wrong!)

Decision based on statistics. In the “cheap/fast/good” triangle of which you can only have two, this is somehow only good, because it is neither cheap (in energy expenditure) nor fast. I could run a special survey - and I would have to do it every year because meaning changes over time - that determines whether or not each term that made the list is an umbrella term, and choose an arbitrary line to divide terms into Umbrella and Not Umbrella, based on the results of that special survey. First of all that sounds exhausting, but second, how would that survey be designed in such a way that participants were not accidentally led by the design? How should I word the question? “Is this an umbrella term” is leading, so “choose the statement that is most true from the following options” is preferable, but what should the radio button for Not Umbrella be called? Because “Not Umbrella” is also leading. And I’d need to include an “it depends” option because it does depend on the context - and what if 95% of respondents choose “it depends”? Would I then need three categories of terms in the survey? And this is only the start of the design questions, I’m sure I would run into many more.

As you can see, I have learned that the researcher’s responsibility and work to remove their own ego from the research is never-ending!

And then, on choosing which words to remove:

having a checkbox ... for “demigender” but not for “demiboy” or “demigirl”

When I do stuff like that, people say things like “I’m a demiboy but not demigender” etc. in textboxes so much that it affects the quality of the data very badly. (E.g. I had to separate “man/boy” into “man” and “boy” because so many people ignored the “man/boy” checkbox and typed in a unique way of saying “I’m a boy but not a man actually” and that, like, broke the data.)

The reason words are added to the checkbox list is because people need to check the box! People have painstakingly typed in words that fit them even though there is a checkbox in the list that already sort of almost fits, and when 1% of people do that it’s kind of a big deal. Arbitrarily removing words that already have close-ish meanings in the checkbox list is shaped by my own perception of the meanings of those words, and that’s me wayyyy overstepping. In the past when I’ve done it I thought I was making an obvious choice using common sense, but it turns out that’s not universal, which was a humbling experience.

~

This has been a ramble, but I hope it helps you and others understand my motivations and responsibilities, and I hope it is interesting or thought-provoking or something! Also, I’ve had a lot of suggestions in the consultation and in the ask box about categorising words to make them easier to go through, and it’s a much bigger explanation/topic than most people realise, so I think a response to those was a good idea so that I can refer back to it later.

#meta#identity#meaning#lexicography#iamthelowercase#just in case iamthelowercase is tracking the tag of their username??#i find Tumblr username tag notifications to be very unreliable so

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

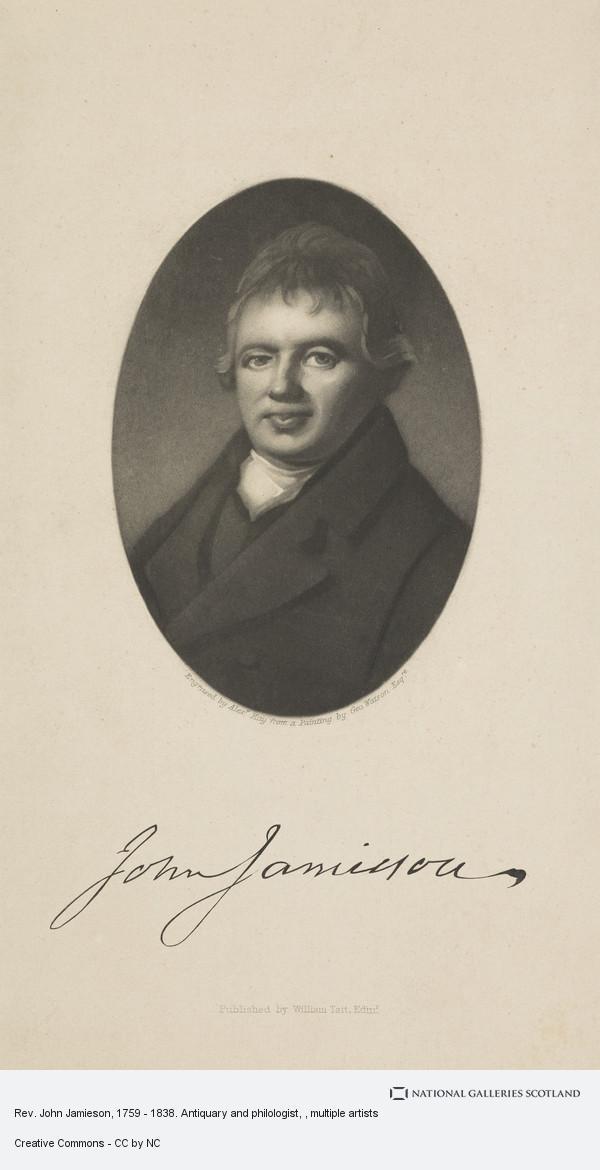

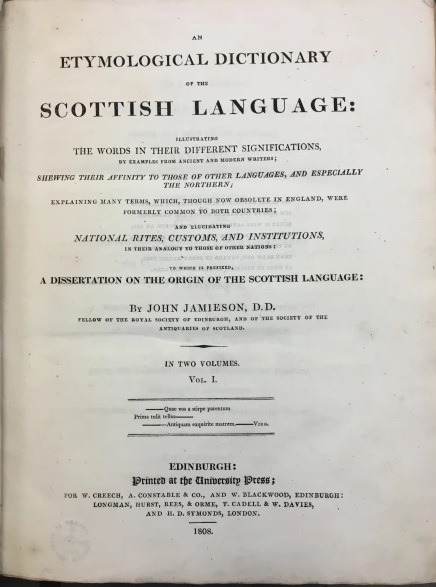

On March 5th 1759 the lexicographer and church minister John Jamieson was born in Glasgow.

I know most of you will not have heard of Jamieson, but his publication, Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language, is credited with keeping the language alive. He was a bit of a polymath though and learned in many fields.

The language I am talking about here is Scots, the Scot’s Tongue as it is often referred to, If you have read some of my posts I like to dig out documents etc from days gone by, a most of these are written in Scots, you only have to read the poetry of Robert Fergusson or Rabbie Burns, the vast majority which is written in the language, or up to modern times if you have read any of Irvine Welsh’s books, you will know that as a language it is distinctly different to what is termed as “proper English”

Anyway a bit about the man, Jamieson grew up in Glasgow as the only surviving son in a family with an invalid father, he entered Glasgow University aged at the staggeringly young age of just nine! From 1773 he studied the necessary course in theology with the Associate Presbytery of Glasgow, and in 1780 he was licensed to preach.

Jamieson was appointed to serve as minister to the newly established Secession congregation in Forfar, and stayed there for the next eighteen years, during which time he married Charlotte Watson, the daughter of a local widower, and started a family. Their marriage lasted fifty-five years and they had seventeen children, ten of whom reached adulthood, although only three outlived their father. He next became minister of the Edinburgh Nicolson Street congregation in 1797 where he guided the reconciliation of the Burgher and Anti-Burgher sects to a union in 1820.

In 1788 Jamieson’s writing was recognised by Princeton College, New Jersey where he received the degree of Doctor of Divinity. His other honours included membership of the Society of Scottish Antiquaries, of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh, of the American Antiquarian Society of Boston, United States, and of the Copenhagen Society of Northern Literature. He was also a royal associate of the first class of the Royal Society of Literature instituted by George IV.

Jamieson’s chief work, the Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language was published in two volumes in 1808 and was the standard reference work on the subject until the publication of the Scottish National Dictionary in 1931. He published several other works, but it is the dictionary he is best known for.

He had a particular passion for numismatics, and it was their mutual interest in coins which led to the first meeting between Jamieson and Walter Scott, in 1795, when Scott was only twenty-three and not yet a published author. Jamieson was also a keen angler, as the many entries relating to fishing terms in the Dictionary attest; and published occasional works of poetry, including a poem against the slave trade which was praised by abolitionists in its day. Entries provided by Scott include besom, which he described as a “low woman or prostitute,” and screed, defined as a “long revel” or “hearty drinking bout”. I wonder how many Scottish females have been called “a wee besom” by their mothers with neither really knowing it’s true meaning!

Jamieson’s association with Walter Scott was a two way thing, he wrote a Scots poem ‘The Water Kelpie’ for the second edition of Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.

It was through his antiquarian research that Jamieson developed his practice of tracing words (particularly place-names) to their earliest form and occurrence: a method which was to be the foundation of the historical approach he would use in the Dictionary.

Jamieson wrote on other themes: rhetoric, cremation, and the royal palaces of Scotland, besides publishing occasional sermons. In 1820 he issued edited versions of Barbour’s The Brus and Blind Harry’s Wallace.

Revered by authors including Hugh MacDiarmid, who used it to shape his poetic output, Jamieson’s dictionary has long been regarded as a crucial groundwork which kept alive the Scots language at a time when it was in danger of falling into obscurity.

John Jamieson died on July 22nd 1839 and has a fine gravestone in St Cuthbert’s graveyard in Edinburgh, as seen in the fourth pic.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just so you know, when it comes to language, this blogger is a Descriptivist

Words mean what the people who use them say they mean. Words are spelled how the people who use them say they are spelled.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sterling Martin was in grad school, studying C. elegans worms, when COVID19 hit and suddenly he found himself in lexicography, as part of a team creating a Navajo-English dictionary of science terms.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A thing I think everyone should know about dictionaries is that they are descriptive and not prescriptive. "What does that fucking mean, Casper?" You ask, for the purposes of this rhetorical example. "Can you take the time out of your schedule and thoughtfully provide linguistic knowledge?" No one has asked me ever, but indeed I can.

A dictionary exists to describe a language as it exists. A fun fact about the dates of words in the dictionary— when they were first used in writing— is that they are Always Wrong. Words are always used in spoken language before written language, and particularly in the case of crass language or language used by the lower classes, this gap can be even longer.

Now, the distinction. A lot of people think that dictionaries are prescriptive. That means they exist to tell people which words are "correct". They Do Not. A fun fact about English as a language is that we don't have an "Academy"— that is, an official body that decides which grammar forms and spellings and words are the correct ones. What this means is that... There isn't a correct construction of English grammar, and anyone who tells you that there is is being an elitist twat. And if they tell you that the words you're using aren't in the dictionary? You tell 'em not yet. Or hit them with one. Either.

98 notes

·

View notes