#japanese linguistics

Text

Inarizaki's Kansai Dialect

Japanese Dialects are split into Eastern and Western, with the Standard Japanese dialect being Eastern (Kanto region) and Kansai region dialect being Western (eg. cities of Osaka and Kyoto, and of course Hyogo prefecture- where Inarizaki is from). The pitch, tone, and stressing of the sounds is different from standard Tokyo Japanese so you should be able to hear the difference in how the Inarizaki members speak even if you don't know any Japanese.

just in case yall didn't know, Suna is the only member on the team that does not use Kansai dialect as he was scouted from Aichi prefecture, so he basically just speaks in the standard dialect

Some linguistics of the dialect that may or may not be heard in the show:

"ya" ending vs the standard "da" ending.

Kore kirai ya. vs Kore kirai da. (I hate this.)

the use of the "h" sound instead of "s"

Han vs standard san (honorific suffix, not really used anymore)

Negation suffix "-hen" instead of the standard "-nai".

Taichou kanri dekitehen koto, homen na. vs Taichou kanri dekitenai koto, homen na. (Don't compliment him when he's obviously not taking care of himself.)

verb "oru" vs the standard "iru".

Dareka ga mitoru yo, Shin-chan. vs Dareka ga miteiru yo, Shin-chan.

(Someone's always watching, Shin-chan.)

verb "temau" vs standard "teshimau"

Naitemau yaro! vs Naiteshimau darou! (You're gonna make me cry!)

Negation "suru" verb becomes "sen" instead of "shinai".

Ki ni sen dee. vs Ki ni shinai yo. (Don't worry about it.)

Some words that are different in Kansai dialect:

Honto becomes Honma (really)

Sodane becomes Seyade (thats right)

Nande becomes Nandeyanen (why)

Totemo becomes Meccha (very)

ii becomes ee (good)

"aho" means stupid in Japanese, but apparently in the Kansai dialect calling someone an "aho" is actually a compliment?! (even though it has the same definition)

Overall, I could watch the Karasuno vs Inarizaki episodes a hundred times just to listen to Inarizaki's dialect and how different it sounds to the rest of the characters in the entire show.

Although Karasuno speaks in the standard dialect (which isn't very strange since Miyagi is a suburb close enough to the Kanto region), theres a few lines here and there where one of them says something using the Tohoku dialect (the dialect that would be used often in the rest of Tohoku, such as Aomori).

But that can be a separate post for another day!

(I especially like Kita's voice, thank you Nojima Kenji.)

#haikyuu#inarizaki#japanese linguistics#japaneselanguage#japanese#kansai#kita shinsuke#miya atsumu#miya osamu#miya twins#suna rintarou#aran ojiro#ojiro aran#akagi michinari#anime#anime and manga#linguistics#dialect#kenji nojima#japanese language#karasuno#tokyo

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Japanese→English] @panmaumau Tweet — Color Coded Translation

————————————————————————

何も知らない生き物の顔

なにもしらないいきもののかお

The face of a living thing that doesn’t know anything.

————————————————————————

Please correct me if I made a mistake

#color coded translation#japanese#japanese vocabulary#study japanese#japanese lesson#easy japanese#beginner Japanese#learning japanese#japanese lingblr#japanese linguistics#learn japanese#japanese langblr#japanese learning#japanese language#japanese vocab

101 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just a regular question - the significance of -kun, -chan and -san (in what context are they appropriately used)? Also, why Kiyoi is offended when Hira uses -kun ?

PS: if you have already explained this previously, please let me know where to find the post :)

Hi!

Thanks for the question! I absolutely love talking about things like this, so thank you so much for asking!!

I feel like this is one of the most boring and at the same time most interesting question to ask about Japanese language, haha. The answer probably varies depending on who you ask, and so I am certain some people will want to add to or correct the explanation I'm about to give!

Wall of text incoming...

Here's a short introduction to some of the social hierarchy in Japanese language

...and how it affects your understanding of interpersonal relationships.

"-san", "-kun" and "-chan" are all examples of suffixes that you attach to people's names according to your relationship with them. The closest English equivalents would be "Mr/Ms/Mrs/Mx" but they are not the same. A lot of subtitlers do translate them like this, but I myself prefer not to do so.

Japanese language and culture is in general very polite and based on social hierarchy. The entire language and how you express yourself and how you conjugate words change depending on your relationship with the one you are talking to (strangers/business relation/family/younger/older/etc etc).

In general, once you get familiar with/close to someone, you drop all suffixes. This is called "yobisute" (呼び捨て). You might sometimes keep some form of "chan" if it's a deliberate nickname - like Koichi calling Mitsuru for Micchan in Eternal Yesterday (It's a cute version of Mi-chan - Mitsuru-chan).

"-chan" is mostly used to refer to kids below the age of 12 (elementary school or younger), but you will also hear young adults use it to refer to females (a male may call his college classmate Miko for "Miko-chan"), in which case it becomes a term of endearment (or, depending on how you look at it, slightly condescending due to the patriarchal nature of current Japanese society and language). Koichi using this nickname for Mitsuru is noticeable - it shows that he is very affectionate towards Mitsuru and considers them to be very close friends.

"You will meet Kim-san at 16:00"

"-san" is the most common suffix. It's the "safest" to use and it has no gender. The first time you meet someone, you would typically address them as "Last name-san", e.g. Suzuki-san. If someone refers to "Suzuki-san" in a conversation, you will not be able to tell the age, the gender or virtually anything about this Suzuki - except that the speaker is not particularly close with said Suzuki. In this case, it will be the equivalent to the English Mr./Mrs./Ms/Mx.

In a school or business setting, a teacher or a superior would normally refer to female students or subordinates with -san. They would add "-kun" to a boy's name. In Old Fashion Cupcake, Togawa says "Nozue-san" and Nozue says "Togawa-kun".

"-kun" is usually used to refer to boys younger than yourself, but typically above the age of 12ish (around junior high school age).

I know that technically it can be used to refer to a girl as well, but I have personally never heard or seen that. If someone refers to "Suzuki-kun", you would automatically assume that Suzuki is a younger male.

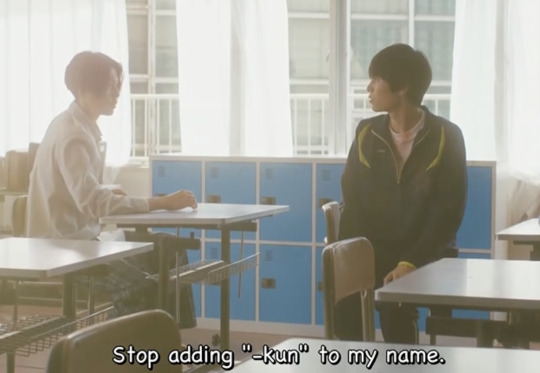

In the Utsukushii Kare setting, Kiyoi is creeped out by Hira referring to him as "Kiyoi-kun" because it is, well, kind of weird.

Girls will call their male classmates for "-kun" and it's fine, because it's kind of cute and submissive; if they're close friends, they'll usually drop it.

Boys will most likely just use last names only, adding no suffixes. Hira referring to Kiyoi as "Kiyoi-kun" not only puts a distance between them, but it even makes him sound submissive. Kiyoi is the only one whom Hira addresses this way - he just says "Shirota" and "Miki" etc. about everyone else.

Kiyoi isn't offended, he's just plain weirded out by it. When he asks Hira to drop it, Hira immediately objects with Muri dayo! ("No way!", "Impossible!") because to Hira, dropping the suffix means lowering Kiyoi from the pedestal that Hira has placed him upon.

Here, Kiyoi literally says "You were able to call (it/me)", because Hira for the first time drops -kun from Kiyoi's name, which immediately changes the relationship between them. Things like this are incredibly hard to get across in a translation, because it's such an ingrained and fundamental part of Japanese culture and language. But it is the first time Hira puts Kiyoi on the same level as himself.

I could do a whole other long post about how the way Japanese people talk tells you so much about who they are as a person (such as whether a boy uses "ore" or "boku" about themselves, or whether they use proper non-gendered speech (like "jyanai") or male speech (which would be "jyanee"). It is an incredibly effective way to show the relationships between characters in media, but sadly this will more often than not be lost in translation.

I hope this answered your question!!

#language in Japanese bl#utsukushiikare#japanese learning#japanese linguistics#美しい彼#my beautiful man#asks

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Linguistics Resources

In my post about beginner language resources, I totally failed to mention three things that have been extremely useful tools, especially in the intermediate level learning and also for more academic linguistic analysis:

Twitter - believe it or not, twitter has a huge japanese user-base, and is super useful for just doing a quick search to see how people are using words/grammar in an informal way. Just throw it in the search bar and scroll to your hearts content, or if there's no results you know it's probably wrong for some reason, it's as easy as that.

YouGlish JA - searches youtube captions for examples of search terms and takes you to the timestamp of that audio. EXTREMELY USEFUL FOR PITCH ACCENT AND PRONUNCIATION.

Tsukuba Web Corpus - If those two fail you, then it's time to pull out the big guns. This is especially helpful for figuring out particle use with verbs, or which verbs occur commonly with particular nouns, but it's so so so so so so soo s o so SO much more powerful than that once you get past the learning curve.

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alrighty, a question! Don't exactly even need to know, but I'm curious. Which japanese names are used gender neutral?

I have heard of a few, like Tsubaki, Akira, Minato and so on, but a list would be nice.

On another note, Erika is a japanese name as well as german, right? Like Yuka is both an Inuit and japanese name x3 I do find it funny that complete different ends of the world could have such small things in common.

gender expressions & impressions of jp given names depend on: (1) the precise characters it comprises of, (2) the reading it uses, (3) societal trends and sentiments, and (4) each individual’s personal perception (and experience) of gender and the name. therefore, sooooo many names out there can be considered unisex and/or gender-neutral! there are hundreds of thousands of possible character combinations you can use to create given names, and what’s more to love is that unisex and gender-neutral names are pretty sought-after, especially in the modern day and the foreseeable future. we love our unisex names and we’re very proud of them!

if there’s any specific theme of names you’d like to see, you can send in an ask with your criterias and i’ll compile you a list. besides my gdoc of rare and unusual jp given names i shared in my previous post, i also have this gdoc of generic/basic/average jp given names you can sort through if you’d like.

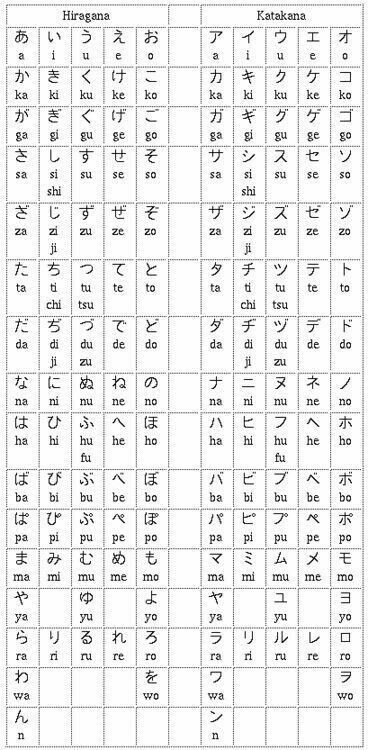

indeed, erika and yuka are names that can exist in the jp language. maybe this tip will help with remembering and identification? you can make given names out of almost any set of syllables from the japanese syllabary, as long as it’s within reason (e.g. sounds good as a name, seems logical or plausible, 1–5 syllables in one name, etc.).

(apologies for the deep-fried quality haha—this is the only kana-to-romaji chart i have ever saved, because i prefer linguistic charts to be as plain-colored, plain-fonted, and plain-formatted as possible.)

for clan/family names however, the rules aren’t as lax because most of them follow kanji and the most standard readings for said kanji. a small % of family names have a mix of kanji + kana in them, which still follow the standard readings of the kanji + of course the unchangeable readings of the kana. only very few (native, non-transcribed) family names out there are entirely written in kana (a real-life example of this is つわぶき峻 Tsuwabuki Toshi, the stage actor who played sakusa in the haikyuu stageplay). oh, and, because we can never have too many exceptions, jp culture also has this very unique occurrence where sometimes, some certain family names get to be as lax as given names in terms of the grapheme-to-phoneme relation, and some people have decided use this opportunity to be very punny wordplayers. these are very few in number, however, and they have history behind them! so i wouldn’t recommend the average writer/artist/fictionist to come up with some on their own. examples of this last one:

一 Ninomae | 一 means “one” | “ninomae” sounds like you’re saying 二の前, “before two”

小鳥遊 Takanashi | 小鳥遊 means “small birds play” | “takanashi” sounds like you’re saying 鷹無し, “there are no hawks/eagles” | ergo, small birds play outside because there’s no hawk preying around.

四月朔日/四月一日/四月朔/四月朔月 Watanuki | 四月朔日/四月一日 means “first of april” | “watanuki” refers to this word 綿抜き, “cotton-stripping; to take out the cotton [padding]” | there’s an old tradition of changing winter-wear cotton-lined warming robes and kimono into lighter summer-wear garments in the 1st day of the 4th lunar month, which is said to prevent children from suffering diseases and potentially dying. i’m a bit confused at what the big deal is with this tradition, because it just seems like common sense to me? seasons change and so do your clothes. that’s normal.

月見里 Yamanashi | 月見里 means “moon-viewing village” | “yamanashi” sounds like you’re saying 山無し, “there are no mountains” | ergo, you can see the moon and do some stargazing if your view isn’t obstructed by mountains. although, i have to point out the fallacy in this logic, as someone who lives surrounded by 3 whole mountain ranges, i know fully well that mountains only obscure a very small % to none at all of your ground view of the night sky. “starless” nights are all the clouds and pollution’s fault! so really, this name should’ve been called Kumonashi (from 雲無し, “cloudless”) instead.

i could’ve sworn i knew more than 4 of these punny family names...

(edit: i found more!)

飛鳥 Asuka | 飛鳥 means “flying bird” | “asuka” refers to the place name 明日香 (“tomorrow fragrance”) | basically, what happened here is that the word 飛鳥 (hichou), coming from the phrase 飛ぶ鳥の (tobu tori no, “flying bird of...”), became a pillow word for the place known as Asuka. both spellings were historically interchangeable.

春日 Haruma, Kasuga, Kasuka | 春日 means “spring sun; spring day” | the word 春日 (shunjitsu/haruhi) was used as a pillow word to introduce the place name Kasuga (which presumably had no kanji writing prior to this?). existing logical readings for 春日 include Haruhi and Haruka.

漢 Hata | 漢 means “han chinese”, the worldwide major ethnic group originating in china | “hata” sounds like you’re saying はた/端, “nearby; besides”

日向 Higa, Higano, Hina, Hinada, Hinata, Hiuga (Fiuga), Hyuga, Hyuuga | 日向 means “in the sun; [facing] towards the sun” | (1) for the Hinata reading; this name is composed of 日 (hi, “sun”) + な (na, old japanese possessive particle, equivalent to modern の) + た (ta, “direction; side”, archaic equivalent of 方). (2) for the Fiuga, Hiuga, and Hyuuga readings; dialectal differences shifted old japanese reading “Pimuka” into “Fimuka” → “Fiuga” → “Hiuga”. southern dialects and languages tend to have this fi- sound that’s nonexistent up in the north. (3) Hiruga may be explained as 「昼日」 (hiru + ka, “daytime sun”) with a rendaku 日 (turning the “-ka” into “-ga”, which is unnecessary, because rendaku doesn’t commonly happen to 日, but everything is full of exceptions today, so... 🤷). existing logical readings of 日向 include Hikou, Himuka, Himukai, Himuki, and Nikkou.

陽向 Hizashi | 陽向 means “in the sun; [facing] towards the sun” | “hizashi” sounds like you’re saying 日差し (may also be written 陽差し、日射し、陽射し、日ざし、陽ざし、日差、or 陽射), “sunlight; sunshine; sun rays”

五十嵐 Igarashi | 五十嵐 means “fifty storms/tempests” | “igarashi” sounds like you’re saying 伊賀嵐, “iga [city] storm” | i believe this may be a reference to the huge storm in 1612 which destroyed the famous iga-ueno castle.

五月雨 Samidare | 五月雨 means “fifth [lunar] month rain”, referring to the heavy rains that occur around early summer | “samidare” sounds like you’re saying 早水垂れ, “early rain fall” | this is a word (for the seasonal occurrence), a place name, and a destroyer name; not family name. i just thought it was cool enough to mention here!

時雨 Shigure | 時雨 means “timely rain; winter rainfall” (originally referred to rainshowers in late autumn to early winter, occasionally late summer and all of autumn too, but today, shigure only refers to a winter rainshower) | “shigure” sounds like you’re saying the classical/literary verb 時雨れる, “to rain a shower” | the history is a bit blurry on this one. 時雨, as a word, was an orthographic borrowing from chinese. it happened a hefty long time ago, and was incorporated into old japanese as the classical verb 時雨る (shiguru), which was later given the modern rendering 時雨れる (shigureru), which then presumably became the clan name Shigure.

日本 Yamatono | 日本 means “base/foundation/origin of the sun” and is the modern name for japan | “yamatono” sounds like you’re saying 大和の, “of the yamato people’s” | 大和 (yamato) was the ancient name for japan before it was changed to 日本 (nihon/nippon), and also the name of an ancient province, the name of the current dynasty (and consequently, the imperial family as well), the name of an old battleship, and is sometimes still used to refer to japanese people in a historic way. it’s worth noting that the reading of “yamato” itself isn’t grammatically logical for the kanji 大和. my best theories as to how 大和 became yamato are: (1) homophone of 山都 (“mountain metropolis”), (2) homophone of 山門 (“mountain gateway”), and (3) homophone of 山人 (“mountain people”); but i haven’t seen any proper, in-depth linguistic study done on this, so i can’t guarantee anything. the kanji 倭 [yamato, shitaga.u | wa, i] was likely based on 大和 after it got its “yamato” reading, so 倭 isn’t an important factor in this discussion (as of right now, at least).

hope this answers your curiosity!

#japanese names#japanese language#japanese linguistics#japanese culture#japanese family names#names#given names#family names#sino family names#sinitic names#sinosphere#onomastics#unisex & gender-neutral#japanese wordplays#japanese puns#gdoc links#skipper answers#rlppl: iced baby

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Linguistic Hurdles of Covering an Assassination

The Linguistic Hurdles of Covering an Assassination

News outlets cover events from around the world and often have to work to get information as quickly as possible to release in their native languages. This can lead to some interesting translation errors or highlight linguistic differences. I want to make it very clear that I am only focusing on those linguistic elements, and am not at all qualified to comment on the shooting of Abe…

View On WordPress

#abe shinzo#assassination#current events#current news#japan news#japanese#japanese linguistics#japanese news#News#translation#world news

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well played, crow. Well played

大 means 'big.' It's used as the place name for Omiya station.

犬 the extra stroke exactly where the crow is standing changes the meaning to 'dog.' So now it's dog-o-miya station.

This crow understands Japanese and is a genius prankster.

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

Birds are famous for communicating vocally, but many have other options, too. Some communicate by dancing, for example, or by showing off their feathers.

And according to a new study, at least one bird species does something more often associated with humans and great apes: symbolic gesturing.

A songbird called the Japanese tit (Parus minor) uses fluttering wing movements to signal "after you," the study's authors report, similar to the way humans extend one open hand to let another person go first.

Continue Reading.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello hello Japanese literature tumblr

Is there someone who could help me identify a bunch of Japanese books I found at a second hand store today?

#IM VIBRATING OUT OF MY SKIN THIS FIND IS SO FUCKING DHSJHFJSJXJDJWJDJDJS#japanese linguistics#japanese literature#japanese writing#japanese writer#japanese writers#japanese books#japanese book#literature#books#bookblr

1 note

·

View note

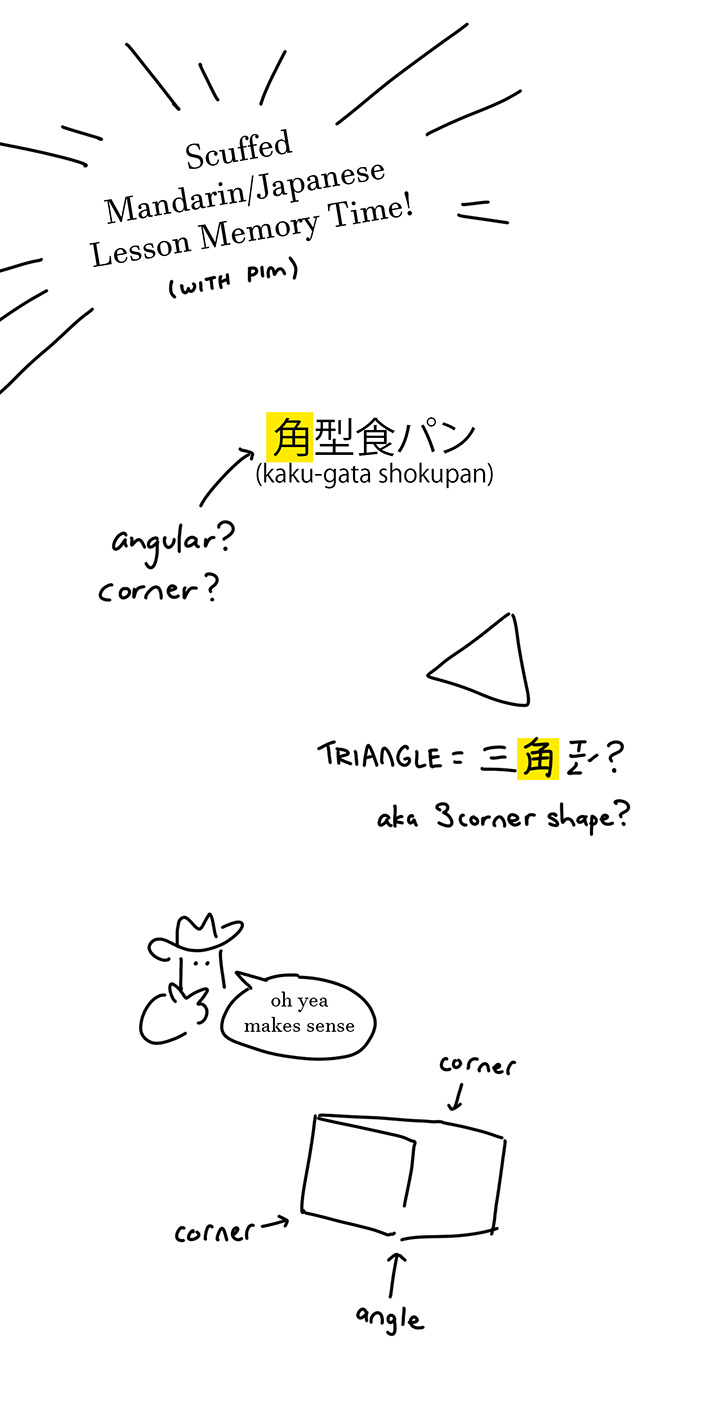

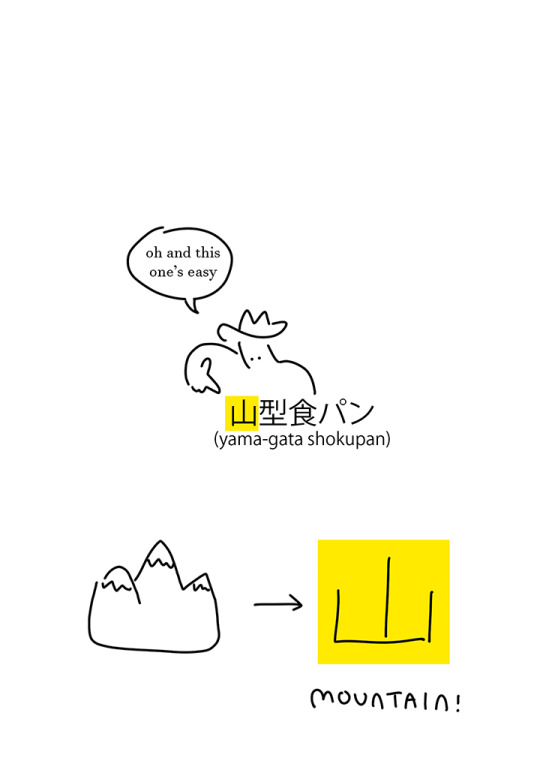

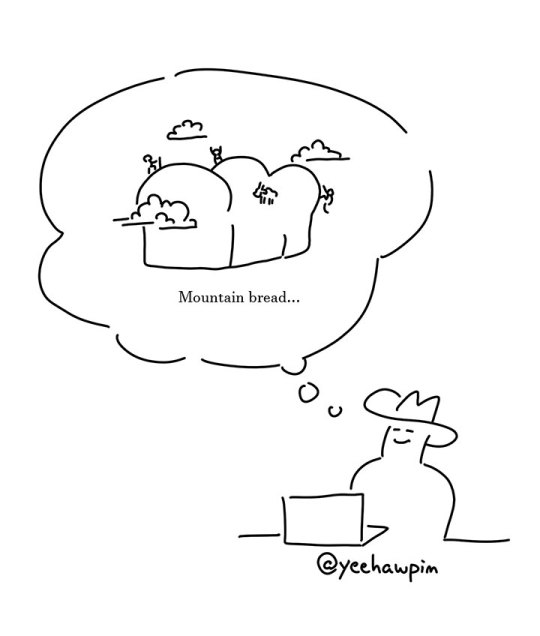

Text

#original comic#artists on tumblr#indie comics#japanese#mandarin#shokupan#linguistics#language#comic#bread#food#my art#my comic#i miss plain toasted shokupan......#i like the square kind the best bc crust is my fav

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

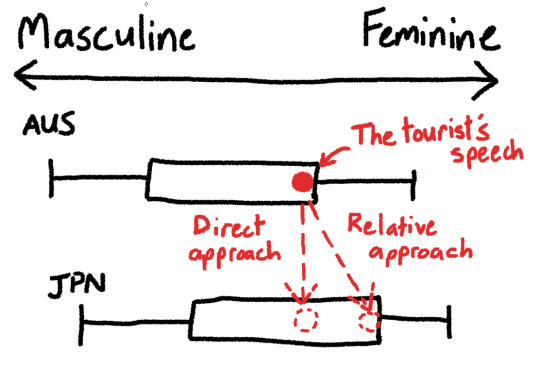

I’ve been having trouble putting this idea into words so you’ll have to bear with me, but I was struck when I saw a Japanese news program interviewing foreign tourists in Japan, and some australian women were dubbed over with a stereotypically feminine speech register (lots of のs and わs), and my first thought was “they weren’t speaking that femininely in english”.

A friend of mine from the UK recently mentioned that he noticed that australia has a generally more masculine culture than england - he felt that everyone is a bit more masculine here, including women. This kind of confirmed to me that my impressions of the dubbing were right - the tourists were speaking in a relatively (internationally) more masculine way. Yet their dub made them sound so much more feminine.

It made me wonder. When translating something, do you translate the manner of speaking “directly”, or “relatively” in terms of cultural norms? Maybe this graph will help me explain the question.

A direct appoach in this case might appear to a Japanese person to result in an unexpectedly masculine register, but preserves how the speaker's cultural upbringing has influenced their speech.

The news program translators chose the relative approach - I think I would prefer the direct approach. I think I prefer it because I believe translation should be a rewriting of the original utterance as if the speaker was originally speaking the target language, and the direct approach compliments that way of thinking the best.

Actually now that I type that, I’m second guessing myself. Does it? It does, if for the purposes of the “rewrite it as if they spoke japanese” thought experiment, we suppose the speaker magically learned japanese seconds before making the utterance, but what if we suppose the speaker magically grew up learning japanese - then maybe they would conform to the relative cultural values. But also, maybe they would never have said such a thing in the first place - their original utterance was informed by their upbringing and cultural values, so how could you possibly know what they would have said if they had known japanese from birth? Maybe my initial instinct was right after all?

If you work in translation, I’m very interested to hear if you have come across this problem and how you deal with it 🙏

Further reading: I think this question also ties into this problem I’ve been struggling to answer for a while.

654 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haikyuu Miyagi Dialect

So I mentioned in my Inarizaki's Dialect post that Karasuno (and the other Miyagi schools) would actually speak in the Tohoku dialect (technically). They don't really speak in the dialect (they speak the standard dialect since they live in a suburb of Sendai, which is big enough and close enough to the Kanto region (tokyo)), but theres a few lines in which some characters do use a little bit of dialect. So here are some examples that I can think of:

disclaimer - im too lazy to properly rewatch the show so im going off memory, therefore i cant guarantee 1000000% accuracy

Sugawara, Terushima, Hinata, Oikawa, Asahi, and Iwaizumi seem to have the most noticeable Tohoku dialects from what I remember hearing??

Suga (and Terushima?) especially ends his sentences with "-yarube", "-dabe", "-be" quite often which is very miyagi of him, he definitely has the strongest dialect out of all of them.

A specific example from Asahi is him saying 俺は昨日残るって言ったべよ! (ore wa kino nokoru tte ittabeyo).

I also remember Iwaizumi saying バレーはコートに6人だべや! (bare wa koto ni roku nin dabe ya).

Hinata says 昼飯食うべ (hirumeshi kuu be) along with other tohoku-like sentences

and I think Daichi once says 一回聞いとくべ (ikkai kii toku be)

I also remember reading somewhere that "boke" (often used by Kageyama and Iwaizumi) is reminiscent of the Tohoku dialect but im honestly not too sure....?

OoOOOooOO i just remembered a specific dialectal word that Oikawa once uses towards Kageyama is おがったね (ogattane). he uses the verb おがる (ogaru) which means "to grow up" in tohoku dialect.

Ukai once uses いずそうな (izusouna) which is also part of miyagi dialect

basically, you can assume that sentences ending with "-be" in haikyuu are miyagi dialect

(this is a completely different anime but in jujutsu kaisen Itadori actually uses some tohoku dialect closer to the beginning of the story which I thought was also interesting)

#japanese linguistics#japaneselanguage#linguistics#anime#anime and manga#haikyuu#sugawara koushi#asahi azumane#sawamura daichi#hinata shoyo#kageyama tobio#iwaizumi hajime#oikawa tooru#ukai keishin#terushima yuuji#karasuno#aoba johsai#dateko#date tech#shiratorizawa#johzenji#dialect#language learning#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#yuji itadori

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Japanese->English] @id_tomo January 26th 2023 3:36 PM Hellotalk Post - Color Coded Translation

Link to original post

—

うん てん めん きょ

やっと運転免許とれたよ!

I finally got my driver’s license!

—

Please correct me if I made a mistake

$5 translation commissions here

#color coded translation#japanese#study japanese#learning japanese#japanese language#japanese vocabulary#learn japanese#japanese to english translation for japanese learners#japanese to english#japanese linguistics#japanese lesson#japanese learning#japanese langblr#japanese lingblr#japan life

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

When someone speaks a foreign language in public and I’m desperately trying not to stare like I’m sorry I’m not racist I just desperately want to hear the different vowel sounds you’re making. sorry.

#also every time I hear a language in public I wanna figure out what it is#and don’t even get me started on if it’s one I recognize#if it’s Japanese I’m like#if they say one of the few words I can understand I go insane#even if they just use particles. and I hear/recognize them. it’s so exciting for me#<-(I’m a nerd and this is what qualifies as fun for me)#but also it’s rude to stare and eavesdrop too much I’m sure#and I don’t want people to feel uncomfortable#Quinn posts#language#langblr#linguistics#language learning#languages#100#500

841 notes

·

View notes

Text

接続詞(せつぞくし)

conjunctions - words that are used to link phrases together

情報を加える // Adding information:

しかも besides

そのうえ moreover, on top of that

さらに moreover, on top of that

そればかりか not only that, but also...

そればかりでなく not only that, but also...

情報を対比する // Putting into contrast:

それに対して in contrast

一方 whereas

他の可能性・選択肢を言う // Giving alternatives:

あるいは or perhaps (presenting another possibility)

それとも or (presenting another option within a question)

結論を出す// Drawing a conclusion:

そのため for that reason

したがって therefore

そこで for that reason (I went ahead and did...)

すると thereupon (having done that triggered sth. to happen)

このように with this (adjusting a conclusion to the arguments given beforehand)

こうして in this way

理由を言う // Giving a reason:

なぜなら...からだ the reason is

というのは...からだ the reason is

逆説を表現する // Expressing a contradiction:

だが however, yet, nevertheless (contradicting what one would have expected)

ところが even so (spilling a surprising truth)

それなのに despite this, still

それでも but still (despite a certain fact, nothing changes)

説明を補う // Amending one's explanation:

つまり that is, in other words (saying the same thing using different words)

いわば so to speak (making a comparison)

要するに to sum up, in short

説明を修正する // Revising one's explanation:

ただし however (adding an exception to the information stated beforehand)

ただ only, however

もっとも however (obviating any expectations that might arise through the previous statement)

なお in addition, note that (adding supplementary information)

話題を変える // Changing the subject:

さて well, now, then (common in business letters after the introductory sentence; is often ignored in tranlations)

ところで by the way

#文法#grammar#conjunctions#japanese grammar#jlpt n2#japanese langblr#japanese language#language#japan#japanese#japanese vocabulary#langblr#linguistics#studyblr#study blog#studyspo#study motivation#study aesthetic#study notes#learning japanese#nihongo#日本語#日本語の勉強#light academia#light acadamia aesthetic

702 notes

·

View notes

Text

as far as being a trans person in japan goes, despite all of the difficulties that come with that, I think one of the most accommodating things has been... just the nature of pronouns themselves, in the language.

sure, literal translations of gendered third person pronouns exist (彼 and 彼女, kare and kanojo, he and she respectively), but... like, nobody uses them. for one, they're both words for "boyfriend" and "girlfriend" respectively (even if 彼氏, kareshi, is more common than just 彼), so you run the risk of a... rather awkward miscommunication. but, perhaps more pertinently, it's much more common to just use a person's name or title.

on the other hand... you know what does have gendered nuance and is commonly used? the word "I." or, more precisely, all the different first person pronouns in the language.

just by saying "I," "me," or "my," you can... so seamlessly make a statement about yourself and your identity in the middle of nearly any sentence.

queer people use this to express their gender identity. queer people use this to express their subversion of gender roles, too. in retrospect, it makes saying "my name is [name] and my pronouns are [pronouns]" feel so clunky when I can just... move on to my next idea, and just casually convey similar information!

speaking english in the states, i feel like it can be dangerous, sometimes, to introduce yourself with your pronouns, especially when the whole point is to greet people you're meeting for the first time. best case scenario, it's like, oh, those are your pronouns, that's cool. worst case scenario, it's "oh, pronouns? you're one of those trannies, aren't you?" much more commonly, though, is "oh he identifies as a woman," which Makes Me Want To Tear My Hair Out All The Time Why.

when i'm in japan, though, I can just be me, and simply, casually, refer to myself as such. and I think that's pretty cool.

(for more on queerness and gendered language in japanese that delves into A Whole Lot More Nuance, check out this tofugu article)

#that being said you still shouldnt overuse the first person pronoun in sentences where its contextually obvious if you wanna sound fluent ww#japanese#language#lgbt#trans#linguistics#rambles

446 notes

·

View notes