#sinosphere

Text

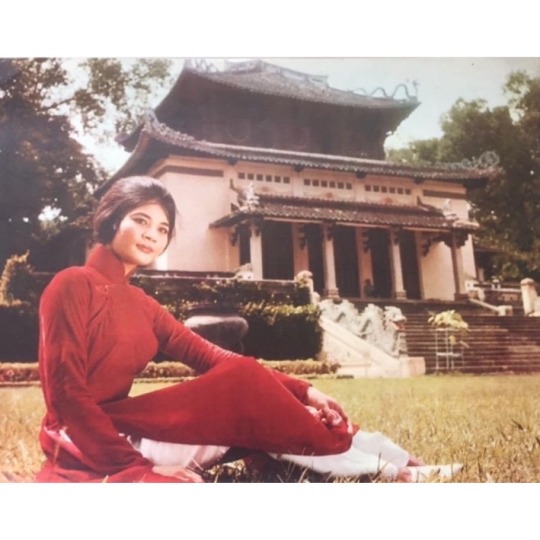

Áo dài. Credit to kemmiethecat (Instagram).

30 notes

·

View notes

Video

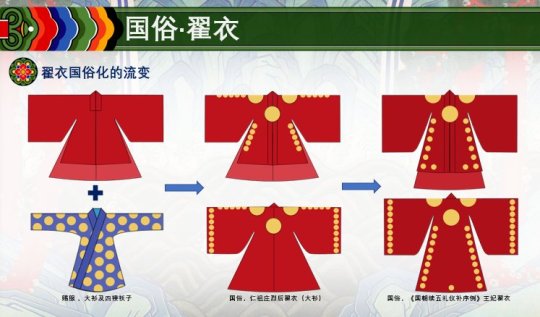

【Historical Artifact Reference】:

Ming Dynasty Royal Portrait:

・Portrait of Empress Xiaoduanxian (Chinese: 孝端顯皇后; 7 November 1564 – 7 May 1620) In ceremonial dress (翟衣/di yi)

・Nine Dragons and Nine Phoenix Crowns of Empress Xiaoduanxian (※This Phoenix Crowns only for important ceremonial occasion which call “礼冠/Li Guan” wear with ceremonial dress(翟衣/di yi)

----

Unearthed from Ming Dynasty royal mausoleum Ming Dingling (明定陵) , is a mausoleum wehre Wanli Emperor, together with his two empresses Wang Xijie and Dowager Xiaojing, was buried.

In addition to this phoenix crown, the Empress has another phoenix crown for other occasions.

----

Collection of the National Museum of China.

This phoenix crown is 35.5 cm high, 20 cm in diameter, and weighs more than 2,000 grams. It is inlaid with hundreds of high-quality gemstones of various colors and decorated with more than 5,000 fine pearls.

[Hanfu・漢服]Chinese Ming Dynasty Traditional Clothing Hanfu (翟衣) & Phoenix Crown (鳳冠) Reference to Ming Dynasty Relics & Empress Portrait

—–

【History Note】

Diyi (Chinese: 翟衣), also called known as huiyi (褘衣) and miaofu (Chinese: 庙服), is the historical Chinese attire worn by the empresses of the Song dynasty and by the empresses and crown princesses (wife of crown prince) in the Ming Dynasty.

The Diyi also had different names based on its colour, such as yudi, quedi, and weidi. It is a formal wear meant only for ceremonial purposes. It is a form of shenyi (Chinese: 深衣), and is embroidered with long-tail pheasants (Chinese: 翟; pinyin: dí or Chinese: 褘; pinyin: hui) and circular flowers (Chinese: 小輪花; pinyin: xiǎolúnhuā). It is worn with guan known as fengguan (lit. 'phoenix crown') which is typically characterized by the absence of dangling string of pearls by the sides. It was first recorded as Huiyi in the Zhou dynasty(1050–221 BCE).

The Diyi follows the traditional Confucian standard system for dressing, which is embodied in its form through the shenyi(深衣) system. The garment known as shenyi(深衣) is itself the most orthodox style of clothing in traditional Chinese Confucianism; its usage of the concept of five colours, and the use of di-pheasant bird pattern.

【 Influence to Other Country】

Korea

Korean queens started to wear the Diyi (Korean: 적의; Hanja: 翟衣) in 1370 AD under the final years of Gongmin of Goryeo,when Goryeo adopted the official ceremonial attire of the Ming dynasty. Same as the early Korea Joseon, were bestowed by the Ming Dynasty.

According to the Annals of Joseon, from 1403 to the first half of the 17th century the Ming Dynasty sent a letter, which confers the korea queen with a title along with the following items: 翟冠(Ming womens whose husband held the highest government official posts can wear this kind of crown,different from Ming Empress Phoenix Crown 鳳冠), a vest called 褙子(Beizi), and a 霞帔(Xiapei). However, the Diyi sent by the Ming dynasty did not correspond to those worn by the Ming empresses as Joseon was considered to be ranked two ranks lower than Ming.

Instead the Diyi which was bestowed corresponded to the Ming women's whose husband held the highest government official posts. In the early Ming Dynasty period, the Diyi were given to Korea Joseon By Ming, but after the Ming Dynasty reformed the clothing system, The Ming Dynasty bestow the 大衫( Dà shān) to the Korean queen instead of Diyi. The Diyi worn by the Korean queen and crown princess was originally made of red silk; it then became blue in 1897 when the Joseon king and queen were elevated to the status of emperor and empress.

it then became blue in 1897 when the Joseon king and queen were elevated to the status of emperor and empress.

After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, the system of China granting clothing to Korea was interrupted. Korea Joseon were forced to become tributary state of the Qing Dynasty. Korea Joseon carried out "nationalization" based on the costumes bestowed by the Ming Dynasty in the past. But according <Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty Volume 46> "嬪宮冊禮時, 旣有翟衣, 則當有翟冠, 而我國匠人不解翟冠之制。 考諸《謄錄》, 則宣廟朝壬寅年嘉禮時, 都監啓以: ‘七翟冠之制, 非但匠人未有解知者, 各樣等物, 必須貿取於中朝, 而終難自本國製造, 何以爲之?’ 云則宣庙有: ‘冠則制造爲難。’ 之敎。 “

Although Korea Joseon has Diyi,but no craftsman know how to make 翟冠(Di Guan), and the materials needed for make 翟冠(Di Guan) need to be taken from China (which need money for that). After all, it is difficult to manufacture in Korea. Therefore, Korea Joseon has not worn 翟冠(Di Guan) since the fall of the Ming Dynasty and change it to 대수머리(大首머리)

Korea "nationalization" process↓

대수머리(大首머리)

Japan

In Japan, the features of the Tang dynasty-style huiyi was found as a textile within the formal attire of the Heian Japanese empresses.

————————

📝Recreation Work & Hanfu: @执月传统服饰 & @鱼墨呀

📸Photo: @执月传统服饰 & @鱼墨呀

🛍️Tabao:https://item.taobao.com/item.htm?spm=a230r.1.14.16.1edc69a6bumOJ8&id=636369495576&ns=1&abbucket=16#detail

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/7454398796/K4mehzhsg

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Ming Dynasty#chinese fashion history#Chinese Culture#Phoenix Crown 鳳冠#Di yi/翟衣#chinese#chinese historical fashion#Empress Xiaoduanxian#Nine Dragons and Nine Phoenix Crowns#Sinosphere#hanfu history#China History

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

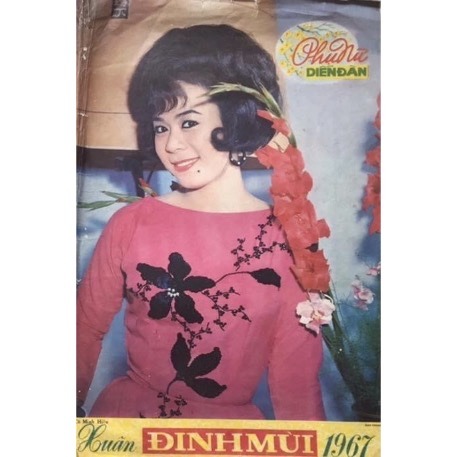

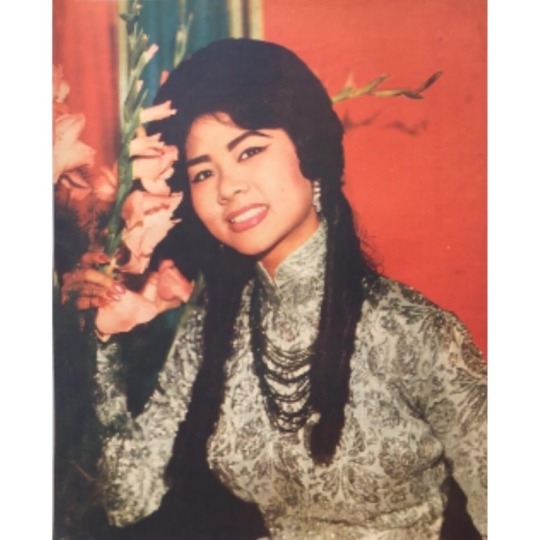

1960s áo dài.

#aodai#ao dai vietnam#ao dai#culture#aodai vietnam#asia#asian#tradition#girl#national costume#vietnam#vietnamese#fashion#historical fashion#history#sinosphere#1950s#1950s fashion

295 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Languages With Hotel Del Luna

☆ scroll ☆ down ☆ for ☆ random ☆ vocab ☆

안영하세요, I've been on hiatus a bit because I'm been ill. But I'm back now and I'm really happy because I've basically found a way to hack my language learning to the point I can actually use it to not only maintain but also improve my Mandarin level (the language I really don't want to lose)

你们好! 我没有写那么多因为我生病了。但是,我会过,和我很喜欢因为我发现能侵截我的语言学习的办法。这让我不但保持我的中文水平,而且提高我的普通话能力,因为我非常不想失去这个语。

Ok, so Hotel Del Luna is a bit old at this point but I wanted to use something where I didn't feel any time pressure because I'm using it to learn languages.

对,现在,满月路管比较老,但是,我想过我没有感觉任何时间压力的事,因为我用它学语言。

☆ scroll ☆ for ☆ vocab

Conveniently, netflix has the option to add simplified chinese subtitles. As I already know mandarin, this means I can watch in Korean and follow along in simplified chinese. I'm semi fluent but it is still pretty hard at this point, so I'm also watching at a reduced speed. Just not so slow that it looks weird or is impossible to watch.

随手,netflix 有加普通话字幕的机会。因为我已经学到足够普通话,这让我看到这个电视剧在韩语,同时,蹑踪(niezong)用普通话。我一半流利,但是,还艰难在这个时点; 所以我也用更慢的速度。就是不太慢,否则看一下比较怪,不能看到。

The process is when I come across mandarin vocab I don't know, I look it up and note it down, creating a vocab list. At my current mandarin level, I'm roughly able to figure out the meanings of words based off the radicals in the characters, so I don't need so many repetitions to remember the vocab.

当我发现不知道的普通话词汇时候,我的办法包括看一看在词典和写到,创造词汇目录用普通话。我现代汉语的水平让我弄懂(nongdong)词汇的意思用汉子的偏旁,所以,我不需要爱那么多重复记得这个词汇。

This vocab is then serving as a list I can look up in Japanese and Korean (my two target languages!) These ones are a completely different story as they're totally new to me.

这次会然后为我能在韩语,日本语(我两个目标语言)检索的目录。这都是很不一样的故事,因为她们对我完全新的。

☆ scroll ☆ for ☆ vocab ☆

Along with Vietnam, Korea and Japan are part of what has been known historically as the sinosphere, a geoup of countries which have been influenced by china. But this doesn't mean the languages are similar at all!

跟越南,韩国,日本,都是中国领过国的一部分,也被中国影响。但是,他们的语言非常不一样。

By combining them here, I've tried to use the show as a theme for my studies and for compiling vocab, not due to any similarities between the languages. However it seems to be working, because I'm genuinely feeling motivated to study for the first time in a while.

为了结合他们这里,我尝试用电视剧为学习题目,汇集词汇,但是这不由于任何期间语言的相思。然而,看来工作的很好,因为我第一个时间感觉激励学习。

☆ THE VOCAB LIST ☆

한국어 🇰🇷

나무 - tree

닫다 - to shut

잊다 - to forget

즐겁게 하다 - to entertain

특별한 - special

운명 - fate

빈둥거리다 - to loiter

정영 - passion (as in enthusiasm or excitement)

열망 - passion (as in sexual desire or romantic attraction)

강렬한 - intense

日本語 🇯🇵

術 、 しゅ - tree

閉じる、とじる - to shut

忘れる、わすれる - to forget

楽しむ、たのしむ - to entertain

特別な、とくべつな - special

運命、うんめい - fate

彷徨う、さまよう - to loiter

情熱、じょうねつ - passion (enthusiasm, enjoyment)

欲望、よくぼ - passion (romantic or sexual desire)

激しい、はげしい - intense

普通话 🇨🇳 🇭🇰

树 - shu - tree

闭上嘴 - bi shang zui - shut your mouth

遗忘 - yi wang - forget

戴 - dai - to entertain

殊 - shu- special

缘分 - yuan fen - fate

徘徊 - pai huai - to loiter

痴情 - chi qing - passion (romantic or sexual with connotations of foolishness coming from the first character, meaning 'stupid')

强烈 - qiang lie - intense

#iu kpop#hotel del luna#mandarin langblr#korean langblr#japanese langblr#japanese vocab list#mandarin vocab#korean vocab list#sinosphere#study aesthetic#studying with kdrama#hong sisters#lee ji eun#yeo jin gu#勉強法#学习#공부하다#sorry for no pinyin#i cant find the tone mark for the third tone#and I hate using numbers#jang man wol#goo chan seong

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alrighty, a question! Don't exactly even need to know, but I'm curious. Which japanese names are used gender neutral?

I have heard of a few, like Tsubaki, Akira, Minato and so on, but a list would be nice.

On another note, Erika is a japanese name as well as german, right? Like Yuka is both an Inuit and japanese name x3 I do find it funny that complete different ends of the world could have such small things in common.

gender expressions & impressions of jp given names depend on: (1) the precise characters it comprises of, (2) the reading it uses, (3) societal trends and sentiments, and (4) each individual’s personal perception (and experience) of gender and the name. therefore, sooooo many names out there can be considered unisex and/or gender-neutral! there are hundreds of thousands of possible character combinations you can use to create given names, and what’s more to love is that unisex and gender-neutral names are pretty sought-after, especially in the modern day and the foreseeable future. we love our unisex names and we’re very proud of them!

if there’s any specific theme of names you’d like to see, you can send in an ask with your criterias and i’ll compile you a list. besides my gdoc of rare and unusual jp given names i shared in my previous post, i also have this gdoc of generic/basic/average jp given names you can sort through if you’d like.

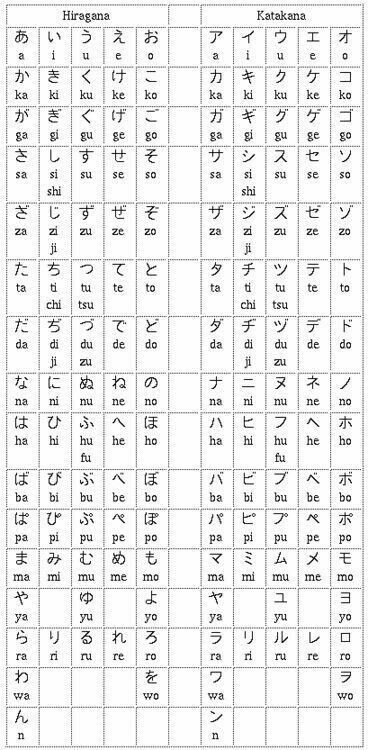

indeed, erika and yuka are names that can exist in the jp language. maybe this tip will help with remembering and identification? you can make given names out of almost any set of syllables from the japanese syllabary, as long as it’s within reason (e.g. sounds good as a name, seems logical or plausible, 1–5 syllables in one name, etc.).

(apologies for the deep-fried quality haha—this is the only kana-to-romaji chart i have ever saved, because i prefer linguistic charts to be as plain-colored, plain-fonted, and plain-formatted as possible.)

for clan/family names however, the rules aren’t as lax because most of them follow kanji and the most standard readings for said kanji. a small % of family names have a mix of kanji + kana in them, which still follow the standard readings of the kanji + of course the unchangeable readings of the kana. only very few (native, non-transcribed) family names out there are entirely written in kana (a real-life example of this is つわぶき峻 Tsuwabuki Toshi, the stage actor who played sakusa in the haikyuu stageplay). oh, and, because we can never have too many exceptions, jp culture also has this very unique occurrence where sometimes, some certain family names get to be as lax as given names in terms of the grapheme-to-phoneme relation, and some people have decided use this opportunity to be very punny wordplayers. these are very few in number, however, and they have history behind them! so i wouldn’t recommend the average writer/artist/fictionist to come up with some on their own. examples of this last one:

一 Ninomae | 一 means “one” | “ninomae” sounds like you’re saying 二の前, “before two”

小鳥遊 Takanashi | 小鳥遊 means “small birds play” | “takanashi” sounds like you’re saying 鷹無し, “there are no hawks/eagles” | ergo, small birds play outside because there’s no hawk preying around.

四月朔日/四月一日/四月朔/四月朔月 Watanuki | 四月朔日/四月一日 means “first of april” | “watanuki” refers to this word 綿抜き, “cotton-stripping; to take out the cotton [padding]” | there’s an old tradition of changing winter-wear cotton-lined warming robes and kimono into lighter summer-wear garments in the 1st day of the 4th lunar month, which is said to prevent children from suffering diseases and potentially dying. i’m a bit confused at what the big deal is with this tradition, because it just seems like common sense to me? seasons change and so do your clothes. that’s normal.

月見里 Yamanashi | 月見里 means “moon-viewing village” | “yamanashi” sounds like you’re saying 山無し, “there are no mountains” | ergo, you can see the moon and do some stargazing if your view isn’t obstructed by mountains. although, i have to point out the fallacy in this logic, as someone who lives surrounded by 3 whole mountain ranges, i know fully well that mountains only obscure a very small % to none at all of your ground view of the night sky. “starless” nights are all the clouds and pollution’s fault! so really, this name should’ve been called Kumonashi (from 雲無し, “cloudless”) instead.

i could’ve sworn i knew more than 4 of these punny family names...

(edit: i found more!)

飛鳥 Asuka | 飛鳥 means “flying bird” | “asuka” refers to the place name 明日香 (“tomorrow fragrance”) | basically, what happened here is that the word 飛鳥 (hichou), coming from the phrase 飛ぶ鳥の (tobu tori no, “flying bird of...”), became a pillow word for the place known as Asuka. both spellings were historically interchangeable.

春日 Haruma, Kasuga, Kasuka | 春日 means “spring sun; spring day” | the word 春日 (shunjitsu/haruhi) was used as a pillow word to introduce the place name Kasuga (which presumably had no kanji writing prior to this?). existing logical readings for 春日 include Haruhi and Haruka.

漢 Hata | 漢 means “han chinese”, the worldwide major ethnic group originating in china | “hata” sounds like you’re saying はた/端, “nearby; besides”

日向 Higa, Higano, Hina, Hinada, Hinata, Hiuga (Fiuga), Hyuga, Hyuuga | 日向 means “in the sun; [facing] towards the sun” | (1) for the Hinata reading; this name is composed of 日 (hi, “sun”) + な (na, old japanese possessive particle, equivalent to modern の) + た (ta, “direction; side”, archaic equivalent of 方). (2) for the Fiuga, Hiuga, and Hyuuga readings; dialectal differences shifted old japanese reading “Pimuka” into “Fimuka” → “Fiuga” → “Hiuga”. southern dialects and languages tend to have this fi- sound that’s nonexistent up in the north. (3) Hiruga may be explained as 「昼日」 (hiru + ka, “daytime sun”) with a rendaku 日 (turning the “-ka” into “-ga”, which is unnecessary, because rendaku doesn’t commonly happen to 日, but everything is full of exceptions today, so... 🤷). existing logical readings of 日向 include Hikou, Himuka, Himukai, Himuki, and Nikkou.

陽向 Hizashi | 陽向 means “in the sun; [facing] towards the sun” | “hizashi” sounds like you’re saying 日差し (may also be written 陽差し、日射し、陽射し、日ざし、陽ざし、日差、or 陽射), “sunlight; sunshine; sun rays”

五十嵐 Igarashi | 五十嵐 means “fifty storms/tempests” | “igarashi” sounds like you’re saying 伊賀嵐, “iga [city] storm” | i believe this may be a reference to the huge storm in 1612 which destroyed the famous iga-ueno castle.

五月雨 Samidare | 五月雨 means “fifth [lunar] month rain”, referring to the heavy rains that occur around early summer | “samidare” sounds like you’re saying 早水垂れ, “early rain fall” | this is a word (for the seasonal occurrence), a place name, and a destroyer name; not family name. i just thought it was cool enough to mention here!

時雨 Shigure | 時雨 means “timely rain; winter rainfall” (originally referred to rainshowers in late autumn to early winter, occasionally late summer and all of autumn too, but today, shigure only refers to a winter rainshower) | “shigure” sounds like you’re saying the classical/literary verb 時雨れる, “to rain a shower” | the history is a bit blurry on this one. 時雨, as a word, was an orthographic borrowing from chinese. it happened a hefty long time ago, and was incorporated into old japanese as the classical verb 時雨る (shiguru), which was later given the modern rendering 時雨れる (shigureru), which then presumably became the clan name Shigure.

日本 Yamatono | 日本 means “base/foundation/origin of the sun” and is the modern name for japan | “yamatono” sounds like you’re saying 大和の, “of the yamato people’s” | 大和 (yamato) was the ancient name for japan before it was changed to 日本 (nihon/nippon), and also the name of an ancient province, the name of the current dynasty (and consequently, the imperial family as well), the name of an old battleship, and is sometimes still used to refer to japanese people in a historic way. it’s worth noting that the reading of “yamato” itself isn’t grammatically logical for the kanji 大和. my best theories as to how 大和 became yamato are: (1) homophone of 山都 (“mountain metropolis”), (2) homophone of 山門 (“mountain gateway”), and (3) homophone of 山人 (“mountain people”); but i haven’t seen any proper, in-depth linguistic study done on this, so i can’t guarantee anything. the kanji 倭 [yamato, shitaga.u | wa, i] was likely based on 大和 after it got its “yamato” reading, so 倭 isn’t an important factor in this discussion (as of right now, at least).

hope this answers your curiosity!

#japanese names#japanese language#japanese linguistics#japanese culture#japanese family names#names#given names#family names#sino family names#sinitic names#sinosphere#onomastics#unisex & gender-neutral#japanese wordplays#japanese puns#gdoc links#skipper answers#rlppl: iced baby

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally managed to translate this Chinese Butchlander video edit set to Eason Chan's Ten Years. Full credit goes to 哥谭名侦探, who made the clip and originally posted it on Bilibili.

Enjoy!

youtube

#butchlander#billy butcher#homelander#video edits#Eason Chan#Ten years#陳奕迅#Perfection#Not mine#I am only the translator#The Sinosphere's Butchlander game is strong!#Youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

ive been trying to figure out the anja/lilith divide because its so strange and i think its mostly just to signify that isa's mom never actually receives a concrete personal appearance or name and that everything we see is purely isa's own internalizations of things which are never depicted or even overtly described

#because the only two characters who like Are Real are isa and erika and both those are actual japanese names#which by coincidence are also german names#and every other character is given a german first name despite every character being associated with the sinosphere#which seems to serve to indicate distance and alienation from the Real#and the literal in universe replication of isa's mother is all but thrown away containing only a single appearance in a note#in which she instructs you how to get into the book shop#vs lilith being an incredibly obviously unrealistic name for someone to actually have by birth due to its connotations#and alongside the fact that alina is already a semi mythical invented character within isa's own head#likely from a picture of someone she saw with her mother without ever learning her actual name

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Manchu music I listen to on youtube has a pretty large Korean fanbase which is interesting to me bc iirc our Qing dynasty was kind of the worst for historic relations with Joseon? I wouldn't expect them to much like the now basically defunct Manchu culture. Like the last reblog mentions, Ming and Joseon were pretty close w/ Joseon being a second in command of sorts (apparently Ming was on good terms with a lot of places haha Qing was both not acknowledged for being 'barbarians' + had to win the acknowledgment w a lot of force) while Joseon really really hated the Qing. Along with Japan and mayyybe Dai Viet (not sure abt this one?) they treated the initial rise of the Qing as the fall of Rome, basically, where they decided that meant they were the ones to inherit the Hua civilization bc China doesn't exist anymore. Apparently certain documents coming out of then Korea and Japan would describe themselves as 'huaxia' to signify their place as the heir to the fallen empire XD In general, though some of the tropes are surely anti-Qing history that arose later, it doesn't seem like Qing was very good for foreign relations, although 'falling' and being treated badly for a century may have redeemed Manchu in the eyes of many non hanzu lolol

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

> malleus description

> yuuya notes he has almond eyes specifically

> almond eyes are commonly associated with the features of sinospheric country natives

This is how Chinese Malleus can still win and beat the allegations from Yuuya's previous description of him you guys🤓☝️😹💔💔💔💔

#twst#malleus draconia#savanaclaw novel spoilers#not that serious post#im too far gone because instead of noticing the malleyuu for once i zeroed in on the almond eyes detail😭😭😭

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hanoi, Vietnam. Credit to Marcus Lacey.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

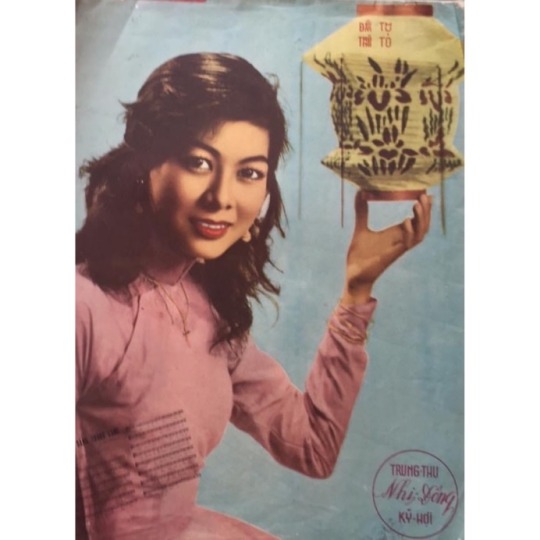

Áo dài.

#aodai#ao dai vietnam#ao dai#culture#aodai vietnam#asia#asian#tradition#girl#national costume#vietnam#vietnamese#fashion#historical fashion#history#sinosphere

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

ngl, i'm a subscriber to the "yong-soo is older than kiku" club too...i know canon says he's 15 or 16 but...eh. i do like some aspects of canon, like its depiction of him being tall and capable of projecting a photogenic image (more so than yao and kiku). but...is there justification for him being that young? old man yong-soo feels like it fits in way better with Korean history imo, and please i cannot resist the whole "the old master and his rival apprentices" dynamic between yao, yong-soo and kiku, with yong-soo being the "older" apprentice—given Korea's tremendously important role as the route through which several Chinese cultural elements were transmitted to Japan in real life (kanji, for one). that is on top of other elements of Korean culture that Japan imported, or Korea being the source of iron weapons and armour during japan's kofun period (300 to 538 AD)—and later, also advanced ship-building techniques.

i feel like it adds further dimension to how we might otherwise have a simplified view of the sinosphere as a universe where yao is the one who turns the wheel of "civilisation": it's also yong-soo taking those influences in. not passively, but actively incorporating his own cultural elements, before they're all passed on by his monks, traders, philosophers, mariners and soldiers to kiku. and in the modern era, Japanese imperial ascendency and ambition isn't just a yao-kiku dynamic of a weary old master and his talented, regicidal protégé, but with yong-soo, about a total inversion and desecration of the confucian hierarchy of seniority too. more than one older nation has had to endure imperial subjugation to a younger one—but in the shadow of meiji japan's naval power, there's the additional sting that it was him once teaching kiku ship-building a long time ago.

160 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was looking into some stuff and came across a post talking about WWX’s arrogance. It was about WWX’s character and how the fandom insists that his arrogance was one of his main flaws when that’s not true and so on. Then I saw some people saying that arrogance is not inherently bad in Chinese novels and that I might have to do with the way the novel was translated.

I was just wondering if you had some insight on this. Thanks!

On some level, it can be considered a translation issue. But the real reason why WWX's characters, as well as countless other details in MDZS specifically (and Chinese novels broadly speaking), tend to be misunderstood on such a massive scale is... cross-cultural value mismatch.

Consider this:

1/ There is a tendency in the international fanbase to judge WWX (and other characters) on a modern Western moral standard. I don't have to tell you how illogical this is. Imagine if you come into the world of Game of Thrones and start spouting 21st-century judgment. You are likely to become human shishkebabs in less than five minutes. Most people who watch Game of Thrones or read the book understand that's not something you do unless you are a moron or looking to start shit. But for some reason, this is not the case for the MDZS fandom (and many other Chinese media fandoms out there). I'm not sure why this is the case. It might be because of the cultural distance making people not really realize they are coming into an entirely different world, and then they forget to check their modern expectations at the door. Like how tourists become obnoxious when they come to a foreign country, expecting the foreign country to cater to their whims.

I've once seen someone made an addition on TV Tropes saying WWX is a mass murderer that never got punished for his crime. I... I don't know what to say to that really. My expectation is that the person who wrote that is someone under 30, never left America, and never served in the military. For somebody who has never had this kind of experience, no amount of words will explain to them that for major parts of the world and for the vast majority of mankind's history, you have to be able to kill to survive. In fact, for most of our history, killers are our heroes. War is a reality that we live in. The ones who survive are the ones who win wars, the really accomplished killers.

2/ MDZS was not written for an international audience. That is to say, it's written with the expectation that it doesn't have to explain its intricacies and tropes to its intended readers. Because its readers already know. MDZS is xianxia danmei. Danmei has only had about 2 decades of modern history. But xianxia as a genre has stretched back millennia. Its tropes are very set. Chinese (and Sinosphere) readers don't need an explanation because we grow up consuming this kind of stories.

We don't need to be told in plain words to know WWX's only crime is to be possession of the Yin Tiger Tally, and the Jin's scheme is the real reason behind his tragedy. Because it's such a standard trope in our culture that there are millennia-old proverbs about it.

匹夫无罪,怀璧其罪 - pǐ fū wú zuì,huái bì qí zuì. Lit. The commoner is innocent, but his possession of treasure is a sin.

We don't need to be told that it doesn't matter if WWX goes along with the cultivation world's ceaseless demands (keep Suibian with him, consult more with Jiang Cheng before he does things) to know that none of that matters. Because none of those are actual rules, just trivial bullshit made up and used to socially isolate WWX and manipulate the public opinion against him. WWX's true crime is that he is alone. He is an orphan. No one will stand up for him. And unlike his big mouth, he's a real softie. Because if he wasn't then all of them would be dead ten times over with the kind of martial power WWX possess. Only WWX's good heart holds him back from really using his ability. Therefore, you can spit on him, you can cut him, you can trample on him without fearing retaliations.

Nie Mingjue has no sword. Ain't nobody try to lip him about it. Yu Furen has no sword. She uses a whip. Ain't nobody lip her about it.

WWX's undead cultivation is also not really the problem. That kind of cultivation is vanilla as girl scout's cookies. It's only made out that way because it's a method of cultivation that is very easy to learn and does not require enormous resources (i.e. caste issue, not class, caste) to cultivate. Which means it's a method that can be practiced far and wide by poor commoners. Which means it's an infringement on the cultivator House's power and financial base. That's its real crime. Not all that justice bullshit.

For many international fans out there, MDZS is their introduction to danmei (and xianxia). So they come in not knowing these things. They don't see the caste issues, the tragedy, the difference of philosophies and choices between WWX and JC. Their conclusion is built on ignorance and misunderstanding.

It doesn't help that most know little to nothing about Chinese culture which is a high-context culture, the polar opposite of most Western cultures (low-context culture). Something that may seem small and insignificant for a Western reader base can be a really big deal for the Chinese reader base, because it's inbuilt in five thousand years of history and culture. Like why Jin Guangyao buried his mother's corpse in the Guanyin temple and why he needed to reclaim it and take it with him when he tried to flee to Japan.

So it's no surprise there is such a massive divide in fandom opinion.

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

The cash or qian was a type of coin of China and the Sinosphere, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD, characterised by their round outer shape and a square center hole (Chinese: 方穿; pinyin: fāng chuān; Jyutping: fong1 cyun1; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: hong-chhoan). Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast, but during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

"why do white people dig into their ancestry for a smidgen of culture" because they think they're not allowed to meaningfully associate with anything outside their own immediate cultural context. Even *universalist* traditions like, idk, buddhism, are tainted by the perception of cultural appropriation because their most recent adherents tend to come from the sinosphere or SE asia

#with buddhism its doubly ironic#because some of the earliest converts were greeks#who they're totally happy to associate with as western/northern europeans#at least *classical* greeks#East asian buddhism was appropriated. i mean transmitted. from central asian sources who in turn received it from northern india#though of course in those days india didnt even exist. so they received it from Gandhara as did the Greeks#I get that white adoption of subaltern cultural elements is fraught#but if you dont want a culture exclusively derived from whitebread protestantism and odinist larping#you will need to be somewhat more nuanced in how you talk about it

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something that I think is interesting about Japanese history, at least as far as I know it, is (and I would of course caution, as I do in general, against reading any sociological conclusions into this) that there do not seem to be many socially/historically salient events or conditions around which a national narrative for the value of "freedom" can be constructed.

What I mean by this is as follows. In both classical antiquity around the Mediterranean, and as far as I know also in Northern Europe and the ancient Near East, you had a robust system of slavery which undergirded most of the economy. To be a slave or a free man was an important social distinction, perhaps the most important, and so this ideal of "freedom" could be constructed and narrativized—although I think in very much a different way than e.g. modern Americans do it. In the (European) middle ages my impression is that there was much less slavery, with the feudal economy now organized around the lords and peasants, which of course presented its own kind of unfreedom but seems not so often to have been framed in the same propertarian terms. And the narratives of virtue that were built up were focused on individual loyalty, fealty to one's lord and so on. I'm not saying it had to be this way, that social narratives necessarily follow from economic conditions or what have you, I'm just saying (to my eye, as a layman, for whatever that's worth) it seems like the economic system changed and the social narratives changed too, in a sort of corresponding way.

And then in the Renaissance you get a revival of interest in classical antiquity, and a few centuries after you get the development of new systems of slavery, and around the same time you get a revival in people talking about "freedom" as an ideal. I don't know if these things are related, and to be honest I don't really know if my impressions of the ebb and flow of the narratives around freedom are really accurate here. Maybe people were talking about it just as much in the middle ages. This is just the impression I've gotten.

Right, so in the West and in the Islamic world you get a lot of talk about freedom, that's my point. Being "free" is a big deal. Maybe for the above reasons, or maybe not.

Another place you can get narratives about freedom is in terms of national self-determination, contrasted with imperialism or national subjugation. So being "free" is something which applies to a state or a people (though it can certainly be extended to the individual, just as narratives about individual freedom can be extended to the nation). When I hear people talk about freedom in the context of regions that, to my knowledge, never had economies built on slavery-as-such (e.g. most of the Sinosphere), this is the frame I most often hear it put in. In Vietnam, from what I gather, freedom is most saliently talked about as freedom from external oppressors of the nation—the Chinese, the French, the Americans. This is the salient historical event around which narratives of freedom are built.

Ok, I want to make very clear what I am not saying. I am not saying that nobody in Vietnam cares about individual freedom, or that nobody in the West cares about national self-determination (both demonstrably false). I am not claiming that people in different countries are even more inclined to think about freedom in one way or the other—how would you even measure that? And I am not claiming that any differences between perception or narrative that do exist between regions are in any predictable or straightforward way products of history. I am merely claiming this: within the discourse that I have been exposed to, "freedom" as an ideal is framed in different ways, and narrativized in terms of different historical events, in different cultural contexts. That is, the above is how I see people talking about things.

Right, so, this really struck me in the context of Japan, where I don't think there really is a salient narrative around "freedom" as an ideal. Japan has never been colonized, save for a brief occupation by the Americans, and it has never had much in the way of slavery-as-such. Even the American occupation is usually framed in the discourse as an indignity, not principally an unfreedom. And obviously narratives around loyalty have a fair amount of currency. Again, I am certainly not claiming that Japanese people value freedom less than people from elsewhere. Posts like this are maybe a bit dangerous because I don't want to play into stereotype, and the presence of such stereotypes in addition often seems to dull the epistemic senses that might otherwise lead people to question such sweeping and difficult to quantify generalizations.

Anyway, the point is that it seems to me that in the Japanese political discourse there is not so salient a historical example to draw on to, you know, make people's hearts swell for freedom as an ideal as there are in many places in the world. And I think that's kind of interesting. Could be totally wrong though—maybe there is one and I'm just missing it.

17 notes

·

View notes