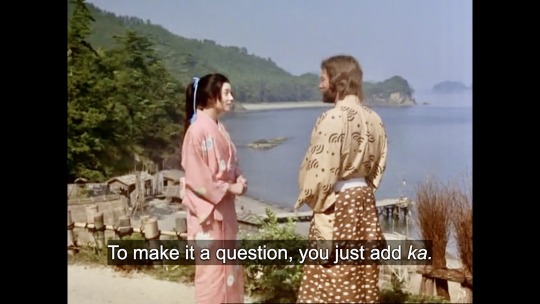

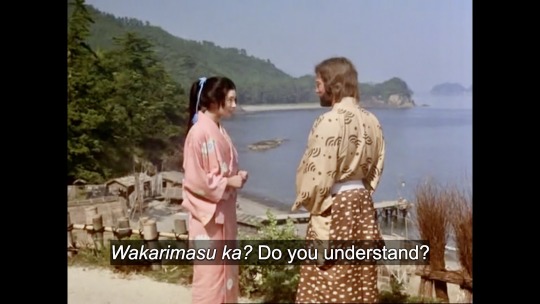

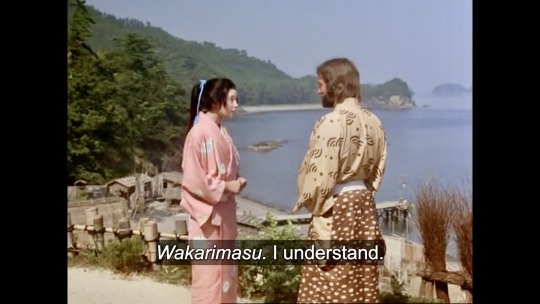

#japanese lesson

Text

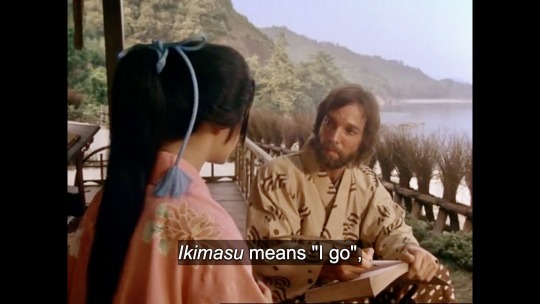

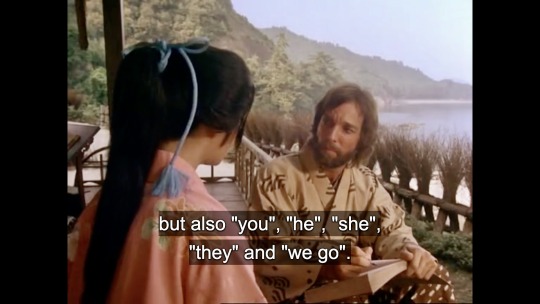

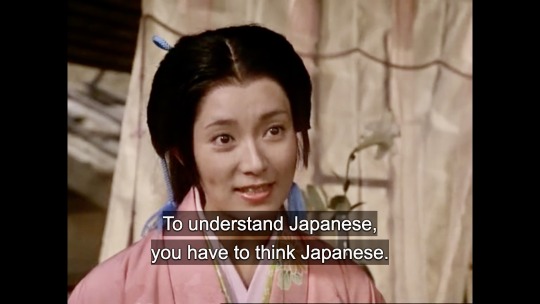

Shogun (1980)

Learning Japanese by the seaside with a pretty teacher. Sign me up. 😆

#shogun#shogun 1980#richard chamberlain#yoko shimada#japan#japanese language#learn japanese#japanese lesson

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Japanese→English] @panmaumau Tweet — Color Coded Translation

————————————————————————

何も知らない生き物の顔

なにもしらないいきもののかお

The face of a living thing that doesn’t know anything.

————————————————————————

Please correct me if I made a mistake

#color coded translation#japanese#japanese vocabulary#study japanese#japanese lesson#easy japanese#beginner Japanese#learning japanese#japanese lingblr#japanese linguistics#learn japanese#japanese langblr#japanese learning#japanese language#japanese vocab

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

The kanji “kei” (系) and its usage

As I still keep seeing it being used in instances where it doesn’t make sense, I thought it would be a good idea to talk a little about the kanji’s actual use within the japanese language.

系 is commonly used as a suffix to categorize and describe various things by their “type”, therefore can also be translated as such. For example, your nationality would be “country+kei+person”, stating the color of something “color+kei+object”, describing a song “genre+kei+music”, and specifying the style of your outfit “style+kei+coord”. However, in the overseas jfashion community there still persists the misunderstanding that it means “style” or “fashion”.

So where does this misunderstanding come from?

The very first instance of “kei” being used in a fashion context overseas was “visual kei” (ヴィジュアル系). During the late 90s, western media outlets discovered the genre and introduced it as unique fashion style from Japan heavily tied to music while also translating its name as “visual style”. This was the beginning of the whole misunderstanding as visual kei is only used to label a band as “visual-type”, meaning there is a heavy focus on a visual aspect. This is also why you will have a hard time shopping for the so-called visual kei fashion because it doesn’t really exist, and what is considered that overseas usually falls under the japanese goth punk (ゴスパンク) style that bangya wear.

After this, many years passed and “fairy kei” (フェアリー系) appeared within the jfashion online sphere, strenghtening the overseas conclusion that “kei” must mean “style” and therefore refers to fashions. While fairy kei is indeed used as a name for this specific 80s-inspired pastel fashion, it’s a lot more common to see it being refered to as just “fairy fashion” in japanese because “fairy-type” is also used to describe plenty of unrelated things. Meanwhile calling it fairy fashion would have been useless overseas for a similar reason and it made a lot more sense to use “fairy kei” instead.

From that point on, the international jfashion community would coin one “kei fashion” after another regardless of the styles actually being known by those names within Japan. Searching the majority of them in their japanese spelling would result in a dead end with many not even making any sense in relation to fashion, such as “mori kei” literally referring to forest types and “pop kei” to anything that’s popular at the moment.

Basically, the lesson of this post is that there is no need to include “kei” in the names of japanese fashion styles unless they are unrecognisable without it, because you are not writting in japanese using the kanji to categorize something by its style. In context of the fashion featured on this blog, it is used to differentiate the overall style genre from the english adjective that is “girly”, but not for its substyles as their names are distinct on their own.

I hope this little language lesson was useful to my readers, and if you have any requests for other jfashion-related terms to introduce or explain - just hit me up in my inbox!

#系#kei#semi-related#japanese#jfashion#term#japanese language#japanese lesson#kei fashion#information

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

にくい - Difficult to, Hard to

Verb in noun form[ます]+ にくい

Polite: Verb in noun form[ます]+ にくい + です

Like 易い (やすい), にくい is an い-Adjective that is regularly attached to the ます stem of verbs, communicating the difficulty of performing the verb that precedes it. In other words, the verb, aka whatever is difficult to do, will always come before にくい.

The nuance of にくい is that a task is difficult to do because of the required skill level or similar factors.

私には英語の「Literally」という単語がとても言いにくい。For me, the English word ‘literally’ is very hard to say. (Hard due to the individual's skill level)

アフリカには行きにくいです。It is hard to go to Africa.

This is different from づらい, which focuses more on a task that is difficult due to being unbearable/hard to endure for some other reason (such as emotional). For example:

お前には本当に言いづらいけど、お前のギターを壊した。ごめん。This is very difficult for me to say to you, but I broke your guitar. I'm sorry. (Hard because the speaker knows that telling the listener will cause a negative response)

#japanese#learn japanese#japanese studyblr#how to learn japanese#studyblr#learning japanese#hiragana#japanese beginner#japanese langblr#japanese for beginners#N4#n4 grammar#japanese n4#japanese lesson#japanese grammar#learn how to speak japanese

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

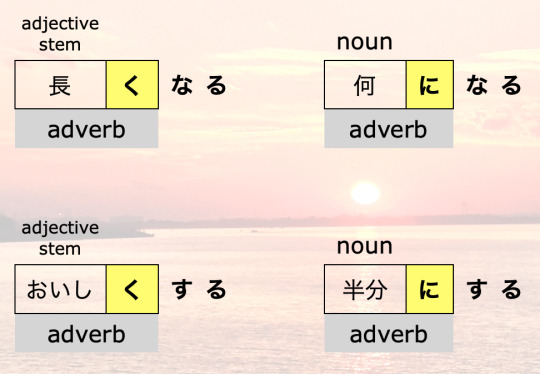

JLPT N5 - くなる and くする

This grammar point is very simple. You use くなる when the condition of something becomes a certain way by itself. On the other hand, くする is used when the condition of something is changed by an outside agent (either a person or a thing). In this post, let’s look at these two very basic constructions and how the Japanese works.

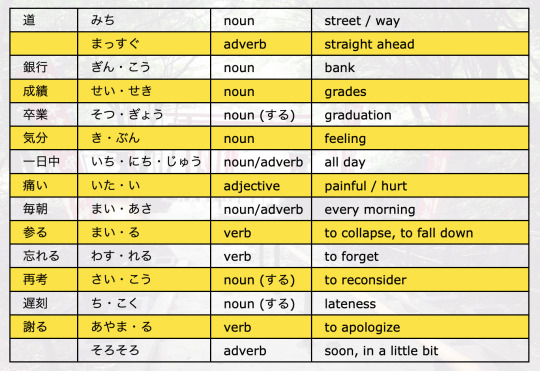

Here is your vocabulary:

【The Grammar】

The grammar is very simple. First, you take an adjective or a noun and change them to their adverbial forms. For example, the adjective 長い has an adverbial form of 長く. The noun ひま has an adverbial form of ひまに.

After you make the adverbial forms of the adjective or the noun, you just put it before either なる or する. That’s it!

We talked about the く connector in this post and about the adverbial に in this post.

I should point out that while this grammar point appears in most JLPT books and websites as くなる and くする, as you can see in the picture above, nouns don’t use く! For that reason, I choose to call this point adverb ✙ なる and adverb ✙ する.

【adverb + なる】

Here are some examples with なる:

① 熱が下がって、気分がだいぶ{よくなりました}。

=fever will go down and then feeling became considerably better

= My fever went down and then I felt much better.

② この仕事が終わったら、少し{ひまになる}と思います。

= when work finishes, a little bit, will become free, I think

= I think that when work finishes, I’ll have more time.

③ このごろ仕事が減って、前ほど{忙しくなくなった}。

= these days, work decreased and so as much as before, became not busy

= These days, I have less work and so I’m not as busy as before.

④ きみは{大人になったら}、{何になりたい}の。

= when you become an adult, what want to become

= When you grow up, what do you want to be (and explain)?

Some things to notice:

In example 1, the sense is that when the fever went down, the person’s mood got better by itself.

In example 2, the condition of having more free time arises naturally when work decreases. (ひま can have the connotation of having absolutely nothing to do and can be considered rude by some people. I use the word for myself sometimes, but I never seriously refer to other people as ひま.)

Concerning example 3, the negative form of 忙しい is with 忙しくない. If you want to make THAT into an adverb, it will become 忙しくなく. This was very difficult for me when I was just beginning Japanese.

Finally, Example 4 shows that the question word of 何 can be treated as a noun. This makes sense if you think of it as a placeholder for whatever answer the listener will give. Also, because the speaker uses the word きみ we know that the speaker and listener are close. It would make sense if it were a parent-child relationship. きみ is NOT used with people that you have just met or that you don’t know well!

【adverb + する】

Here are some examples with する:

⑤(父が子どもに)もっと部屋を{きれいにしなさい}。

= father to his child: a little bit more the room, make it clean

= Clean up your room a bit more.

⑥ このケーキ、ちょっと大きいから、{半分にして}ください。

= this cake, a bit big and so make it half please

= This cake is a bit (too) big so please cut it in half.

⑦ スカートを5センチぐらい{短かくして}ください。

= this skirt, about 5 centimeters make it short please

= Please shorten this skirt about 5 centimeters.

Notice that examples 5, 6 and 7 all include someone (other than the speaker) making a thing (a room, a cake, and a skirt) a different condition than the current one. This is when you will want to use adverb + する.

【Conclusion】

The grammar points of adverb ✙ なる and adverb ✙ する are pretty simple to understand. That is why they are considered Level N5. Adverb ✙ なる shows a person or a thing becoming a different condition by itself. Adverb ✙ する shows a person or a thing changing to a different condition by a different person or thing.

Thanks for reading, and see you next time!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#japanese#japanese grammar#learn japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese study#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#japanese verbs#studying Japanese#japaneselessons#learnjapanese#japanese studyblr#japanese langblr#JLPT#JLPT N5#jlptn5#にほんご#日本語#日本語の勉強#一緒日本語#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#IsshoNihongo

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

奥さん or 嫁さん?

I confess - I am so obsessed with this story that I’ve even started Duolingo for Japanese. While I’ve enjoyed other anime series and Studio Ghibli for years, nothing motivated me to try to learn the language before Mahoutsukai no yome. I have some notion that if I understood the original Japanese I would be that much closer to understanding what Elias x Chise means or what Yamazaki is trying to say about marriage. Of course, that probably isn’t true - it’s probably just as ambiguous in Japanese as it is in English.

Source: https://www.japanesewithanime.com/2018/05/yome.html

My other fandom, the Phantom of the Opera, is also a story with an ambiguous central relationship that raises questions about love and what it means to be married. The first English translation of the original French novel has some major translation issues that are both frustrating and fascinating when trying to understand whether Christine is really meant to love Erik or not. While I’m not fully fluent in French, I can read it well enough to compare the original with the various English translations and consider the details that were left out and how they change the meaning of the story. I want to be able to do this with Mahoutsukai no yome too. There are various English translations of the manga, and then there are the anime subtitles which are not the same as the English dub script. There are endless possibilities for small changes that might alter the meaning of certain scenes. I want to be able to look back at the original when I have doubts.

I’ve learned that there are numerous ways to say wife or bride in Japanese. From what I can tell, the anime most often uses some variation of yome (嫁), meaning bride. But in the very first episode, when Elias first mentions, very casually, that Chise is his future wife, he uses okusan (奥さん), which I understand can mean wife, but also housewife, or any married woman. Bride and wife are certainly related words, but even in English they carry nuanced meanings.

Do Elias and Chise use other words for “wife” that carry other meanings in the story? My Japanese is not good enough to listen for other words yet, but I’d love to hear what other readers and viewers of the series know.

As the story is called Mahoutsukai no yome (Ancient Magus Bride) Chise’s status as Elias’ bride is at the center of the story. At the end of the first arc they have what could be called a symbolic wedding. But was it a real wedding and is it a real marriage? These are the kinds of questions that are never directly answered by Yamazaki, not even in the lovely rooftop scene in which they discuss the various roles they hold in each other’s lives. Is she his okusan, his yome, or some other third thing that doesn’t have any title because it is so unique to this human and her monster husband? It’s maddening and delicious.

#ancient magus bride#mahoutsukai no yome#elias x chise#kore yamazaki#japanese lesson#translation issues#what makes a bride a wife?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌸My Edit🌸

Hiragana - う - u

#my edit#japanese lesson#hiragana#う#u#pink aesthetic#pink edit#cute#kawaii#pink manga#pastel#manga edit#manga#manga cap

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The struggle is real (Sorry Hugo)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

「どうしてピカチュウはピカチュウという名前なの?」

「それはね、ピカチュウは電気ネズミだからだよ。日本語でピカは電気が光る様子を表す音で、チュウはネズミの鳴き声なんだ」

「そうなの?!なるほど~!」

"Why is Pikachu called Pikachu?"

"That's because Pikachu is an electric mouse. In Japanese, ”pika” is the sound that represents the way electricity shines, and ”chu” is the sound of a mouse."

"Is that so?! Now I see~!" 😊👌👌👌

— Почему Пикачу зовут Пикачу?🤷♂️

— Это потому, что Пикачу — это электрическая мышь. По-японски Пика — это звук, вырожающийся света электричества, а чу — это звук мыши».

— Это так?! Теперь понял!

🐭⚡💕

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Japanese is funny. Warui (悪い) means bad, Waluigi is just bad guy Luigi (just like Wario is bad guy Mario).

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I remembered you saying that it was: Tanjirou, Muichirou and many other names ending in 'u' after an 'o' and that it actually is Giyuu not 'Giyu' how is that like this?

I'm a Japanese student. Have been studying the Japanese language for nine years. And when you see an U at the end of a name ending in O. That's a prolongation of sounds. The Kanji for Tanjirou has the U at the end. So the real way to write his name is Tanjirou. Same for Muichirou, Kyoujurou, Senjurou, ect.

And it is Giyuu. Not Giyu. In official arts and stuff for KnY they also have his name be Giyuu. In my honest opinion it bothers me when the names aren't written the right way.

I read kanji and know how to write their names.

#japanese lesson#kny#demon slayer#TANJIROU not tanjiro#GIYUU not giyu#and so on with the other names

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

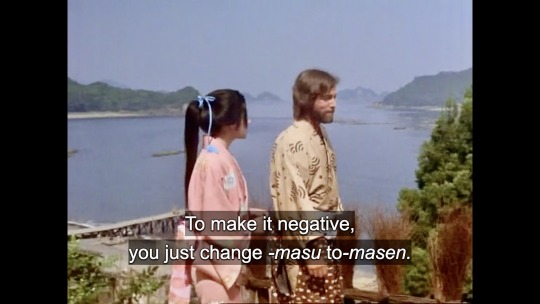

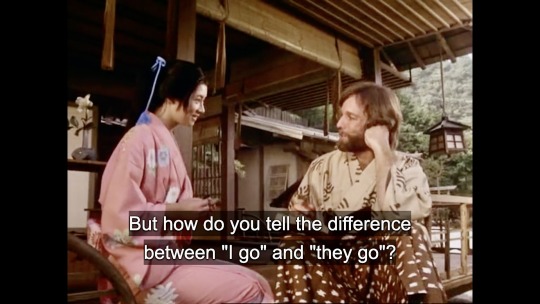

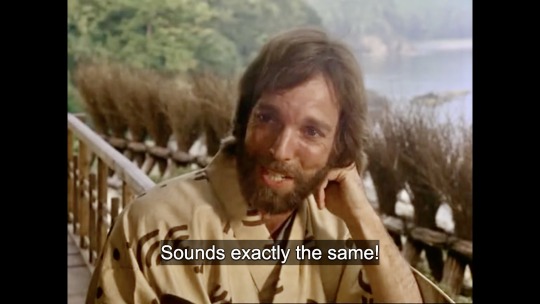

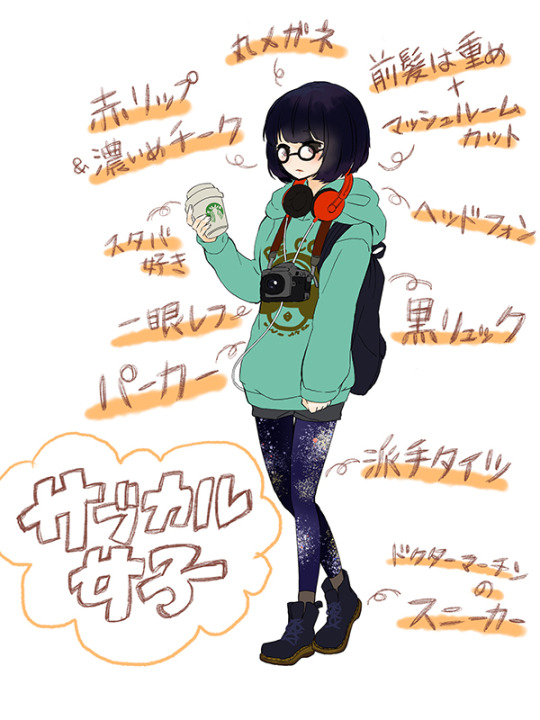

Shogun (1980)

Learning Japanese be like... I'm as confused as he is. 🤣

#shogun#shogun 1980#richard chamberlain#yoko shimada#japan#japanese language#learn japanese#japanese lesson

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Japanese→English] @unico_uniuni 6:00 AM October 11th 2023 Post - Color Coded Translation

HAPPY HALLOWEEN!!!!! 🎃👻🍂🧛🏻🦇🕷🕸

Link to original post

—

うにの儀式です。

うにのぎしきです。

Uni’s ritual.

—

「何の儀式かは内緒です」

なんのぎしきかはないしょです

“What kind of ritual it is, is a secret.”

—

#ミヌエット

#Minuet (a cat breed)

—

#猫好きさんとつながりたい

ねこすきさんとつながりたい

#I Want To Connect With People Who Like Cats

—

#にゃんすたぐらむ

#Nyanstagram

or

#Meowstagram

—

#猫写真

ねこしゃしん

#Cat photo

—

#一眼レフのある生活

いちがんレフのあるせいかつ

#Life with a single-lens reflex camera

—

#くつしたねこ

#Cats Who Have Shoes

or

#Cats With Boots

—

Please correct me if I made a mistake

Created October 2023

#color coded translation#japanese vocab#learn japanese#learning japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese#日本語#日本語の練習#study japanese#uni#cat#halloween#halloween vocabulary#cat meme

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

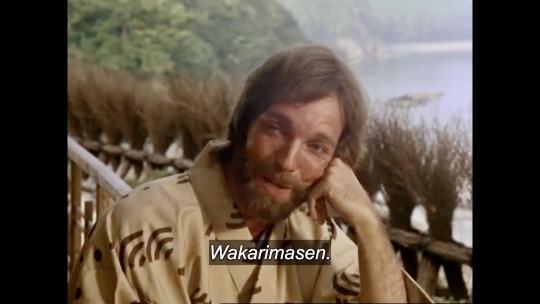

So... What is Sabukaru/Subcul?

You might have seen images like these all over twitter and instagram lately, tagged as "サブカル" or "サブカル系" and assumed that these tracksuit coords are an up-and coming jfashion with that name - but you'd be wrong.

Sabukaru doesn't mean subculture/subcultural fashion.

Although Google Translate seems to think otherwise, サブカル ≠ subculture. Sabukaru is a slang term refering to a specific type of hipster - people who are into niche trends within subcultures (サブカルチャー) not because they particularly care about a given subculture, but rather want to stand out from the others. This isn't something someone would call themselves - a hipster wouldn't call themselves one, right? No actual sabukaru would tag their pictures that way.

So what's this current fixation on mizuiro and yamikawa?

In 2022, quite a few trends started to appear seemingly out of the nowhere. One is a particular light blue x white colorway (水色 aka mizuiro), another is cutified tracksuits (ジャージ), and then there is also maid aprons being worn over those or oversized yamikawa tops. Initially, they were only popular among people who are considered sabukaru, and therefore became known as sabukaru trends.

If they're popular now, how can those trends be associated with hipsters? Why do people still tag them as sabukaru despite having gone mainstream?

Well... because originally, it was sabukaru creating those trends. Much like how by the time the "American hipster aesthetic" became known in the 2010s, actual hipsters had moved on from chunky glasses, typewriters, handlebar mustaches and craft beers, sabukaru no longer associate with the trends currently associated with them, as they have become mainstream. It's yet another person stereotype with associations that change every once and a while, much like ryousangata. As a matter of fact, the main reason as for why Sabukaru-chan (of the Menhera-chan comics) is named Sabukaru-chan is because she fits older sabukaru stereotypes.

A few older "anatomy-of-sabukaru" pictures are below:

In conclusion:

Despite what online translators says, sabukaru ≠ subculture. Despite what some people claim, sabukaru isn’t a specific style or look. As said, it’s only a slang for someone into niche alternative fashion trends.

Thanks for reading!

#サブカル#サブカル系#天使界隈#水色#sabukaru#subcul#tenshi kaiwai#mizuiro#semi-related#japanese#stereotypes#japanese language#japanese lesson#term

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

でも

Meanings:

Or something

Any... (with question words)

Noun + でも + Suggestion

だれでも - Anyone

どこでも - Anywhere

なんでも - Anything

いつでも - Anytime

Behaves like a regular 助詞 (じょし) [particle]. However, it can have more specific purposes. Today, the use I'll be focusing on is presenting examples, or 例示 (れいじ). This results in a translation similar to ‘even’, or ‘or something’.

お茶でも飲みましょうか。Shall we drink some tea or something?

大丈夫だよ、お前でも出来るよ。It's okay, even someone like you can do it.

As you can see, when grouped with typical nouns, でも helps to express an example/suggestion (and that there are other choices/possibilities). But, when the noun is a word like 誰 (だれ), どこ, 何 (なん), or いつ, the translation becomes much closer to English words like ‘anyone’, ‘anywhere’, ‘anything’, or ‘anytime’.

この簡単 (かんたん)な漢字は誰でも分(わ) かるよ。Everyone knows this easy kanji.

「明日はどこに行きたい?」「どこでもいいよ。」 ‘Where do you want to go tomorrow?’ ‘Anywhere is fine.’

お前は本当に何でも食べるね。You really do eat anything.

いつでも電話してね。Please, call me anytime.

*To remember: When grouped with 何, the pronunciation will almost always change to なん.

どこでもいいよ。Anywhere is good.

いつでも家に来てください。Please come to my house anytime.

誰でも彼の名前を知っています。Everyone knows his name.

#Bunpro#peistudies#Japanese#Learn Japanese#Japanese Grammar#N4#Japanese N4#Japanese vocabulary#Japanese lesson#Study Japanese#Japanese for beginners#Beginner Japanese#Langblr#Japanese Langblr#Japanese studyblr#studyblr#learning japanese#how to learn japanese#日本語

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

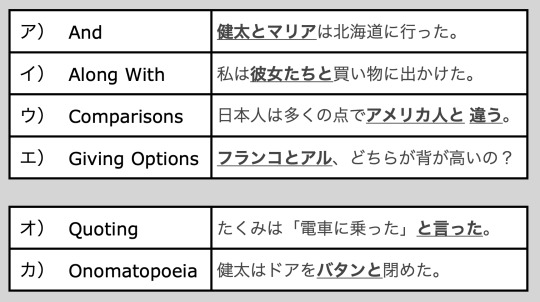

14.4) Conditional Forms (と)

The last conditional form we will talk about is the conditional と particle. First though, it’s important to distinguish between this usage and other usages of the と particle. Just like に and で, there are many ways you will see/hear the conditional と used!

Below are 6 sentences that use the と particle, but NOT the conditional と.

If you want to read about these uses, check out these posts I made about them:

【Examples ア-エ】

【Examples オ and カ】

Also, I already wrote a post about the conditional と particle that you can read here. In this post I’m going to be looking at conditional と in a different way. Here is your vocabulary:

【The Grammar of と】

The conditional と particle can attach to verbs, adjectives and noun-copula pairs (but only in the form of noun+だ).

【Did It Happen Or Not?】

When you look at sentences with the conditional と, there are two possibilities when it comes to the second clause:

If we think of this with English counterparts, here are two examples:

[Case1] When / If water reaches 100℃, it boils.

[Case2] When I walked in the room, the students stopped talking.

In case 1, the event in the first clause (water reaching 100℃) inevitably leads to the event in the second clause (it boiling). That is to say, the second clause hasn’t actually happened yet... but if the first clause happens, it will.

Compare that to case 2, where both events have already happened. This is a big difference between the two cases. Now, here are some Japanese examples:

①{この道をまっすぐ行くと}、{銀行があります}。

= when/if the/this street go straight, there will be a bank

= When/if you go straight down this street, there will be a bank.

②{成績が悪いと}、{学校を卒業できないよ}。

= when/if grades are bad, can’t graduate from school, you know

= When/if your grades are bad, you can’t graduate.

③{学校に行くと}{休みだった}。

= when go to school, it was rest

= When I went to school, it was closed.

【The Timing of と】

Another thing to think about when using the conditional と is the timing of the events. と gives the nuance that both happen almost at the same time.

④{天気がいいと}{気分がいい}。

= when/if the weather is good, feel good

= I feel good when/if the weather is good.

Example 4 is saying that the weather being good directly leads to the speaker also feeling good. The nuance of the timing is that as soon as or soon after the weather is good, the speaker feels good. Sometimes, this means that you can translate the と as “once”.

We will come back to this idea of timing when we compare the conditional forms. 😉

【When or If?】

In general, if the second clause is in past form, the English translation will use “when”.

Here are two more examples:

⑤ 一日中{パソコンを使うと}、{目が痛くなります}。

= all day when/if use a computer, eyes hurt

= When / If I use the computer all day, my eyes hurt.

⑥ 毎朝{起きると}{コーヒーを飲む}。

= every day when wake up, drink coffee

= Every day when I wake up, I drink coffee.

For example 5, there won’t be a difference if you think of the と as “if” or as “when”. However, there is a HUGE difference between “when I wake up” and “if I wake up”! This shows that the action or adjective in the first clause is the key to the English translation. Some words will naturally translate to “if”, and some words will naturally translate to “when”. Many words though, can use either and make sense.

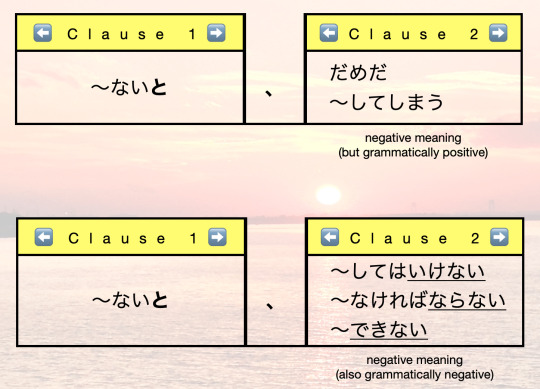

【〜ないと】

The last thing we should talk about is the “warning” usage of conditional と. Because the conditional と expresses a natural consequence or an inevitability, it is often attached to the negative form of a verb in order to warn the listener of some... negative consequence. An extension of this is indicating the speaker’s responsibility or duty to do something.

There are three kinds of clauses you will see / hear after a ないと clause: (1) a grammatically positive phrase with a negative meaning or (2) a grammatically negative phrase with a negative meaning. Here are some examples:

だめ simply means “it’s not good”.

〜してしまう has a nuance of something unexpected happening. For example if you use the verb 参る with しまう, you get 参ってしまう which means “unexpectedly collapse or fall down”.

〜してはいけない is a roundabout way of saying “don’t do 〜”. For example if you use the verb 忘れる in this construction you get 忘れてはいけない. This basically means “don’t forget”.

〜なければならない means “have to do 〜”. If you use the word 再考する in this construction, you will get 再考しなければならない。This means “have to reconsider”.

Finally, 〜できない means “can’t do 〜”

Here are some examples with Japanese sentences:

⑦{早く起きないと}{遅刻するよ}。

= in an early way, if don’t get up, will do lateness

= If I don’t get up early, I’ll be late!

⑧{アンに謝らないと}{いけない}。

= to Ann, if I don’t apologize, it won’t go/do

= I have to apologize to Ann.

Notice how clause 2 in example 7 is grammatically positive (遅刻する) but has a negative meaning. On the other hand, clause 2 in example 8 is negative (いけない) and also has a negative meaning. This is something you will see quite often after a ないと phrase.

The third possibility for what comes after a ないと clause is... nothing! Japanese often avoids being direct by simply not saying a phrase or a word. With ないと clauses, everyone knows that the following clause is something negative so it’s ok to just not say anything. The listener or reader can use their imagination to figure out the negative consequence(s). Here is an example:

⑨{そろそろ寝ないと}。

= well... soon if don’t sleep...

= Well... I need to sleep soon.

First off, we don’t actually know who the subject is in example 9 but we can assume that it is the speaker though. The speaker intentionally leaves off the second clause. We don’t actually know what will happen if he/she doesn’t sleep but because of the ないと, we know it won’t be good!

【Conclusion】

And that is what you should know about using the conditional と. I hope this post was helpful and informative. As always, if you have any questions, let me know!

The next post will be the last one in this conditional forms section, so look out for that. Good luck with your Japanese learning adventure!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

#japanese#japanese grammar#learn japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese study#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#japanese verbs#studying Japanese#japanese particles#japaneselessons#japanese langblr#learnjapanese#japanese studyblr#japanese conjunctions#japanese conditionals#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語#日本語の勉強#一緒日本語#IsshoNihongo

154 notes

·

View notes