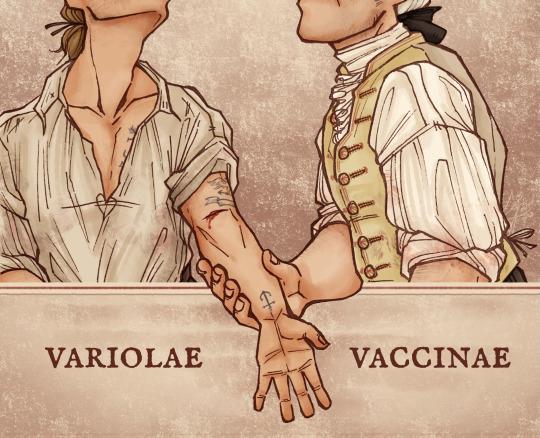

#in fact it is smallpox inoculation!

Text

a little pain now, to save a great deal more pain later

[flintlock fortress is a collaboration with @dxppercxdxver]

#em draws stuff#flintlock fortress#team fortress 2#blood#today on the em cupola show: wild self-indulgence. but hey I feel Bad so I'll draw what I Like. and today that's medical procedures.#someone leaned over my shoulder while I was drawing this and asked 'is that bloodletting' and they were Almost Right so I'm endlessly proud#in fact it is smallpox inoculation!#sorry to everyone who I have bothered with my Smallpox Talk in recent memory but It Will Happen Again.#the game style itself is kind of rockwell and leyendecker-y to me so I wanted to do something with a similar look to their work#had a lot of goals for this piece and I think I really did achieve all of them quite nicely#could I keep these guys recognizable without showing their full faces? yes I think so!#could I make 'getting a mild case of smallpox with the lads' seem a bit romantic even? yes to that too.#also. scout tattoos make an appearance. (do not go looking for them in any other art of him on account of I Forgor)#and a new look for ansel (this man dresses Boring but that is no fun for me to draw)#'backstory relevant' I say as I do not discuss any of these guys' backstories again.#'that's for us to know and for you to find out' I say while giving you no way at all to find out#have been in a constant state of 'by gosh having a little less blood in me would make this situation better' for several days now#and while I am using Normal methods to improve the situation drawing such things does work a bit to heal the mind#'we're doing just fine' says local guy who is madly drawing the same guys over and over again

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ardeo

Caracalla gets a fever. Part IX of my Emperor Caracalla series.

No warnings, unless you're squeamish about smallpox. I'm not an immunologist, so note I'm taking poetic license here for dramatic effect.

Interesting fact: Inoculation was thought to be developed in China more than 1,000 years ago. Who knows if other cultures explored it around that time or earlier.

----

The fever was stealthy, as the worst ones often were. Caracalla was riding, the wind warm on his back, his retinue of Praetorians riding in formation beside him, when he felt light-headed. The sun is in my eyes, he thought, the angle too bright. But when he arrived back at the fort and dipped into the coolest of the three baths, he felt only discomfort.

At that evening’s feast, he felt peckish and cross (more so than usual), unable to muster even a sarcastic retort to Julia Domna’s shrewd analysis of the Legion’s military strategy along the Rhine river. Only Gelvira seemed to sense something was amiss, her fingers quietly brushing his as he poured his fourth cup of wine, his hand shaking as he set the heavy goblet back down on the table with a splash. “Perhaps Caesar needs to rest,” she murmured softly, the only person who could suggest the idea of his vulnerability without him flying into a rage.

Caracalla waved his hand dismissively, but it felt heavy, as if made of iron. The floor swam up toward the middle of his vision and for a moment he wondered if he had accidentally eaten another of the potent mushrooms from the night they had conceived. “Very well,” he said, and rose unsteadily from his chair.

When they entered the chamber, Caracalla bade Decimus to extinguish the fire. He leaned against Gelvira as she led him to the bed and helped him to disrobe. Caracalla fell back against the pillow and felt black exhaustion overcome him.

By morning, he was on fire. The cushions beneath him were wet with his sweat, and a strange sour taste was in his mouth. That day, Gelvira did not leave his side, wiping his brow with fresh cloths dipped in cool water that smelled of crushed peppermint to cool his skin. Decimus brought him mead and wild boar for strength, but he could not eat. His mother glided into the chamber as the sun set and laid her hand above his brow, a stern look on her face. She glanced at Gelvira, who was holding his hand, and tilted her head toward the doorway. “Healer, speak with me.”

“No,” croaked Caracalla. “She stays.” Julia pursed her lips into a thin line, but nodded and exited the chamber. Gelvira turned back to Caracalla and clasped his hands in hers. “I am here, Lucius,” she whispered. “I will not leave you.”

“Let me feel our son,” he asked, his voice thin and stretched. “Let me feel you, Gelvira.”

Wordlessly, Gelvira slid her shift off her shoulder and placed his hands against her belly. They were as hot as tongs from the fire but she did not flinch. Caracalla closed his eyes and pressed into the hardness underneath the soft curves. He is there, he thought. My son grows strong. He is there. Darkness fell upon his thoughts once again.

_____

The next hours were some of the worst Gelvira had ever experienced. Caracalla’s fever worsened and he became delirious. Various Roman doctors and priests came and went, muttering about humors, bodily fluids, and offerings to Serapis. Gelvira did not want to leave his side, but she knew stronger medicines were needed. Caracalla was developing strange blisters around his mouth and on his tongue. Gelvira knew if he didn’t drink he would be dead by the morning, so she coaxed fluid into him as gently as she could, patiently dripping mead or water into the side of his mouth with a spoon so that swallowing was less painful. When Decimus stood in the doorway, unable to attend to Caesar with his usual duties, Gelvira bade him sit by his side and take over the task. “I’ll be back as soon as I can,” she said, gathering her shawl around her. “If he wakes, tell him I am in the next room fetching more water.” Decimus nodded somberly.

Gelvira made her way into the long hallway of the abode, praying that the sisters of the Circle would speak to her, when Julia Domna stepped into her path. Even though the hour was late she remained impeccably dressed, the jewels in her hair and around her neck glowing in the light of the wall sconces.

“What is your plan, healer?” she asked imperiously, but Gelvira sensed her anxiousness. Without one of her sons holding the reins of the Empire her own place was tenuous, her power only permitted by her connection to her firstborn.

“I must confer with my Circle,” said Gelvira. “They hold the wisdom of 1,000 years. If this disease is known to our people, they will know of medicines to cure it.”

“Your people cannot make an offering to Serapis or to Asclepius,” Julia answered. “Only the Gods can heal my son, so that he may rise from the ashes of this disease and fulfill his destiny.”

Careful of what you speak of, thought Gelvira. She had heard the stories of the sick and nearly dead burned alive, to ward off contagion from the plague that had swept through the land in her forefathers’ time. Even now, pits of ash were scattered through lower Alemania, Roman soldiers and barbarian farmers alike. The Suebi would not plow plants in these fields, afraid that the roots would bear bitter fruit and spread death.

“He needs medicine,” Gelvira said again, clenching her jaw in frustration. She daren’t speak of her darkest fear - that Caracalla had somehow contracted the storied plague from before, for his symptoms were troublingly similar. “Please,” she said quietly, “let me help him the way I know how.”

Julia drew a deep breath and her nose flared in disdain, but she stepped aside to let Gelvira pass. “Do your best, healer,” she called after Gelvira. “For my son cannot die.”

—--

Caracalla runs, panting, through the narrow alleys of the northern spur. The Coliseum lies ahead, the roar of the crowd wafting from the distance. They cheer for him but not me, he thinks. I must run faster, be stronger. He overtakes the boy, shoving him aside, and the boy trips and falls. Caracalla looks back triumphantly and the boy raises his head and his face is hauntingly familiar. “Wait,” he calls out. “Wait,” and then vanishes into the mist.

____

Upon the direction of Julia Domna, Gelvira rode to her village with Caracalla’s prefect. “Wait here,” she bade the soldier as he helped her to dismount from the horse. Gelvira ran to the dwelling on the edge of the village.

“Sisters,” she called as she entered. “Sisters, I need your help!”

Gelvira stood, panting, as the women turned toward her silently. None spoke as they gazed upon her, and Gelvira felt her face flush hot with anger. Finally, one of the leaders stepped toward her. “What is it you seek?” she asked.

“Knowledge,” answered Gelvira, “for the plague has returned.” There was a murmur among the women and several backed away from Gelvira.

“Gelvira,” said a voice, and the Eldest made her way slowly toward her, leaning on her walking stick. “Tell us everything.”

Gelvira nodded and sat near the hearth as some of the others gathered around her, but most stayed away. Gelvira spoke of Caracalla’s fever, his delirium, inability to eat or drink, the white sores that appeared around and inside his mouth. She feared they were in his throat and inside his body as well, drawing strength from him.

“Do they spread upon his body?” asked the Eldest. “Have others fallen ill?”

“No,” said Gelvira, feeling her exhaustion come across her suddenly. She hugged her arm around her belly, as if she could protect the life growing inside from the threat.

“If the blisters turn black he is dead,” said the Eldest. She intoned the rhyme that had been passed down, Sister to Sister, so that the knowledge was not lost:

Black and blood grows the heat

Until the body covered complete

Eyes are dazed mouth is full

Until the gods of death pull

None should live unless they leap

Into silvery scars that heap

Along the skin that slivers and cracks

Life returns but strength not back

Gelvira scowled at the fire, her mind working furiously in concentration. “So if the blisters fill with blood it is too late, but if they remain white, he will live?”

“I cannot say,” said the Eldest. “I remember it was capricious. Some would suffer terribly and yet recovered from it, others barely showed symptoms but dropped dead without warning. I thought I was spared until the end. I never recovered enough strength to run again.” She looked down at her walking stick for a moment.

“How many died in the village?” asked Gelvira. The Eldest shook her head. “Too many.”

Gelvira wrung her shift in her hands, staring into the fire. She felt lost and unsure what to do. The Eldest laid a soft bony hand upon her lap, startling her from her reverie. “Gelvira,” the Eldest said softly, “you must protect the life you carry. You cannot tend to Caesar in this fashion. I fear it may already be too late.” Gelvira began to shake, and the Eldest took her hand and comforted her as tears began to flow. “We must perform the ritual, without delay. Prepare yourself.” Wiping her face, Gelvira nodded.

_____

Gelvira clung tightly to the bandage around her arm, held (ironically) in place by the golden cuff. She was anxious to get back to the fort, fearing the ritual had taken too long. In her hands she held a small leather pouch. The Praetorian noticed it as he helped her back onto the horse. “Is that for Caesar?” Gelvira shook her head. “No, it is too late. But it is for you, and for others who have touched him. It was given with great sacrifice.”

The Praetorian pursed his lips and muttered something that sounded like ‘barbarian’ but Gelvira had lost any concern of what Caracalla’s prefect thought. Her mind was racing furiously. The Eldest had given the most, but a few others in the Circle had also survived the plague as children, and they too opened their wrists to mix their blood into the pot. Gelvira had gritted her teeth as her arm was sliced and the mixed blood dabbed into her wound. The Eldest spoke to her as another Sister poured the liquid into the pouch. “You must perform the ritual on the others when you return. They all will fall ill but will not die from it. Your Caesar is too far gone to benefit from it. I’m sorry, Gelvira.” She patted her shoulder, and her eyes were kind. “We will pray for you. And pray that whoever rules Rome remembers this kindness from the Suebi. We are counting on you, Gelvira.” Gelvira nodded, too tired to respond.

—--

Caracalla crouches in a thicket of nettles, just beyond Hadrian’s Wall. He’s on the north side, the rugged side. Braver than the others. Let the Caledonians come, he was ready. The nettles itch, the fire from their stingers traveling up his back and surrounding his neck. He has to focus, to concentrate. He senses movement ahead and throws his knife, hitting a young boy in the chest. He rises, making his way to see but the boy sinks into the ground. The nettles are all over his skin, stinging, and the pain begins to take over his senses, driving him mad.

_____

When Gelvira returned to the fort, it was eerily silent. Even on the darkest night there were always one or two soldiers busting about, attending to some matter or drunkenly going about their business, but now it was as still as a tomb. The prefect looked around nervously as he led his horse to the stable and Gelvira ran to Caesar's abode.

She entered Caesar’s chamber to find Decimus sitting next to him with a glazed look in his eyes, sweat pooling down the back of his tunic. I must not delay, she thought. “Decimus,” she said softly, touching his arm and finding it too hot for her liking. “Please fetch Julia Domna and anyone who has entered Caesar’s chamber.” Decimus blinked and nodded, standing unsteadily and making his way out of the chamber as if in a daze.

Gelvira turned to look at Caracalla and she had to clap her hand over her mouth to stop from screaming. In the hours since she had been gone the blisters had spread to his face and neck. She lifted the coverlet to see they were on his back and shoulders as well. His skin was red but the pallor on his face was white.

“What have you brought us, healer?” Gelvira turned as Julia Domna and her retinue entered, followed by Decimus. Gelvira gestured to the pouch in her hand. “Life.”

____

Gelvira worked feverishly over the next hour, dabbing the blood mixture into the arms of more than a dozen people. Decimus went first, holding his arm as the prefect cut it with a knife and Gelvira used the flat of the blade to dab the Sisters’ blood into it. “Rest now,” she said to Decimus, and then attended to the prefect and several of the Praetorian guards who had ridden with Caracalla. Julia Domna and her priests observed as the guards were treated and then Gelvira looked up at them. “Please hurry,” she said, feeling a panicked urge to cover Caracalla’s body with her own. She wanted to lie down on the earth and rest forever, for she was tired beyond imagining. But she could not stop.

“The Praetorians trust you,” said Julia. “You have earned their respect.”

Gelvira said nothing. The sound of Caracalla’s labored breathing filled the chamber.

Julia looked over at her son, and Gelvira saw a torrent of emotions flicker across her face - fear, anger, sorrow and disdain. Finally she turned and sat on the stool placed near Gelvira, and offered up her arm. “I place my faith in your medicine, healer. Rome itself is in your hands tonight.” Gelvira nodded, and carefully took Julia’s arm to make the cut. Julia hissed through her mouth as the blade went through her olive skin, and watched as Gelvira repeated the ritual with her. Gelvira hoped it would be enough, for the blood was beginning to congeal.

“What of my son?” asked Julia as Gelvira bound her arm with a bandage. She shook her head. “He is too far gone. The blood is only for those who have not succumbed yet. You may get sick but will not die, for the blood is taught to fight with this.”

Julia nodded and rose to exit the chamber. Several of her priests followed but one lingered behind. Gelvira waited, to see if he would accept the ritual, but he eventually followed the others. Very well, thought Gelvira, as she looked at the bottom of the bowl. The last of the blood had dried.

_____

Without Decimus to help, Gelvira lugged water from the bath back to Caracalla’s chamber, and continued to dab his skin and trickle it into his mouth. The blisters continued to spread. A strange odor filled the chamber, and Gelvira feared it was the smell of bodily fluid. I must stop the blisters from forming, she thought. But how?

Tired, she put her head into her hands. I must pray to the All Father. But it is so hard to find the words. Closing her eyes, she formed a simple prayer: All Father, please give me wisdom. Please save him, the father of our child, who is the future of our tribe. The gods favor this child, you must spare him. Please, All Father. Give me a sign.

Her exhaustion overcoming her, Gelvira lay her head on the bed next to Caracalla and took his limp hand in her own. “Come back to me,” she whispered. She dozed off to the smell of peppermint combined with the sour stench of his sweat.

—--

Caracalla is lost, crashing through the undergrowth of thick trees, he can’t find his way out-

—--

Gelvira jerked awake. Caracalla had called out, she was sure of it. She leaned forward to hear if there was more, but he had curled away from her, exposing more of his back. Slowly she traced one of the blisters with her finger. If only I could be a balm for him, she thought. Suddenly, the answer came to her in a flash. Her tiredness gone, Gelvira stood up so quickly the stool clattered against the floor, causing a guard to rush into the chamber. “Fetch me your prefect at once,” Gelvira commanded him. “We have work to do.” The guard looked at her for a moment, then bowed his head. “Yes, healer.”

A short while later, the wind was rushing against her face, as she rode with the prefect and several soldiers into the forest. The morning sun had risen, and Gelvira spotted what she was looking for growing in a large patch near a birch grove. A sign from the All Father, she thought. It must be. Dismounting, she rushed to the field, her knife already in her hand, and gathered up the lemon balm quickly, cutting the stalks and tossing them into her basket. The soldiers followed suit. After gathering a good half of the patch, they hastened back to the fort.

Gelvira led the soldiers into the kitchen, startling the cook. Gelvira cleared the table so the men could quickly begin to cut the plants into pieces. Gelvira stirred the chopped leaves into a large pot mixed with oil. She bade the cook to boil water and commanded the kitchen slave to gather dozens of cloths and to make sure they were clean. When the kitchen smelled like lemon, Gelvira knew it was time. “Go, bring these to the bath house, and keep them warm,” she said and the slave nodded. Gelvira turned to the soldiers. “Come with me. Hurry.” They ran to Caracalla’s chamber.

The chamber was dark and the air thick with incense, but it did little to mask the foul stench. Julia Domna was on her knees before the rekindled fire, muttering incantentations to a clay figurine. Several of her priests were gathered around Caracalla and Gelvira saw they were preparing to bleed him. Gelvira summoned every bit of authority she had accumulated over the past months into her voice. “No!” she said firmly, and the priests paused in the dim light.

Gelvira turned to the soldiers. “Soldiers of Rome. You must trust me. I have spent many moons healing your brothers. I know a better way. Please. Have faith in my gods and my people. Help me carry him to the bath house. The wounds must be washed.”

There was silence in the chamber, and Gelvira held her breath- Would the soldiers listen? Would Julia and her priests yield?

Without a word, the soldiers moved forward in formation and shoved the priests aside, lifting Caracalla from the bed. Julia Domna rose to standing but said nothing. Caracalla hung limply as the guards carried his naked body out of the room. Gelvira ran after them, followed by Julia and the priests.

When they arrived at the baths, all eyes turned to Gelvira. The Romans were silent as she inspected the pot of simmering lemon balm and the pot of boiled cloths. It was now or never. Gelvira turned to Julia. “We must bathe him, so that his blood will not become poisoned.” Julia nodded and signaled to the soldiers, who lowered him into the water. Gelvira fetched several of the boiled cloths and waded into the pool after them. She began to gently clean the blisters along Caracalla’s face and neck as the men held him. Caracalla’s eyes fluttered open and he seemed disoriented, but he didn’t protest.

Julia waded in as well, and the women worked together, dabbing the hot cloths against the blisters. As they worked, Gelvira called out for the slaves to bring fresh linens and to lay them on the tile. As soon as they did, she bade the men lift Caracalla onto the sheets. Caracalla’s eyes were darting from side to side and his tongue was lolling out of his mouth, but he did not seem to see them. Gelvira knelt down alongside and gestured for the lemon balm leaves to be brought to her. Carefully, she dipped one of the cloths into the pot, wrung it carefully and placed it against his blisters. The Romans watched as she slowly covered Caesar’s body with the bandages, layering them over each other until only his face was visible. She then wrapped the sheet over him tightly, sealing in the steam and balm oil. Her work done, Gelvira wiped her face and sat up.

“It will cool into a salve, to prevent more blisters from forming. He must be kept clean, so the blisters do not fester. If they turn black his blood is poisoned. If they remain white he may-he may live.” She fell forward onto her hands, her braid undone, and let out a shuddering breath.

Silence. Only the sound of water lapping against tile. Gelvira realized that Caracalla’s breathing appeared less labored.

“It will be done, healer.” Julia’s words echoed across the room, and Gelvira felt a surge of relief before she collapsed in exhaustion.

—---

Caracalla was standing in brackish water, green slime gathering along the edge of his toga. The mud between his toes was sticky and he had to fight to lift each foot as he staggered forward. Each step was more draining than the last. After toiling for what seemed like an eternity, he knelt down in the water to rest. Just for a few moments, he thought. I only need to rest a few moments.

“You’re too stubborn to ask for help,” said a voice, and Caracalla turned to see a young girl, barely old enough to be on her own, her shift torn and dirty, standing at the edge of the brackish pond. Though her face was streaked with dirt she had a regal air, and Caracalla saw the wildflower crown in her hair. I know this face, he thought. “Gelvira,” he whispered. “Help me.”

“What’s the magic word?” asked the child.

Caracalla sighed, and black water wafted under his chin. It was soft, and he wondered if he let his head slip underneath whether it would feel like drifting off to sleep. “Please,” he whispered. “Please, my love.”

“Thank you and you’re welcome,” said the child, and tossed him her flower crown. Caracalla held it in his fingers, until the flowers unwound into a long thread, and the child pulled, and Caracalla was lurching forward, climbing, until his feet touched the hard pebbles underneath the surface that led to the edge. He crawled out of the swamp and flopped onto his back. The child stepped over him, her face and long curls blotting out the sun. “You’re silly,” she said, before running back into the meadow.

Caracalla sighed, and drifted off.

____

Gelvira woke at dusk. Slowly, she sat up from the bench in the corner of the bath house, stretching her stiff neck. The slaves were re-applying fresh lemon balm cloths to Caesar’s blisters. Gelvira rose to inspect their work, and she noticed that Caracalla’s coloring seemed better. She knelt and grasped his hand as the slaves continued their ministrations.

“He rests easier,” said one of the slaves. Gelvira nodded, and prayed silent thanks to the gods. Looking around, she asked quietly, “What of the others?”

“They have succumbed,” said a slave, “but it is not as it was with Caesar.”

“Decimus?” Gelvira whispered, afraid to hear the answer.

“He fevers, but no blisters my lady,” answered another.

Lady, thought Gelvira. If they only knew.

Later, after tending to all of the afflicted, she stepped out into the twilight, and took a deep breath of misty evening air. A night swallow flew overhead, and Gelvira took it as a sign that the worst had passed. Quietly, she laid a hand on her belly.

The sound of footsteps startled her, and she turned to see Julia Domna approaching, followed by two priests. Only two, thought Gelvira. Julia’s sharp eyes glanced down at Gelvira’s hand on her belly as she strode past her, followed by the priests and several men carrying a body wrapped in a cloak. They slowly filed toward the courtyard, where soldiers were erecting a pyre.

The body burns until it meets the fire, thought Gelvira. But my Caracalla lives. My lover lives.

#barbarus#caracalla x gelvira#gladiator II#make way for the emperor#joseph quinn#joseph quinn fic#joseph quinn angst#hurt/comfort

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson: The Dying Detective

Crimes in context:

Medical History

Sorry in advance for the medical grossness. Please skip to the cut if you never want to see the words open sores ever again.

First, to piece together Culverton Smith's crimes against humanity and also the murder. Culverton Smith appears to have gone to Sumatra to make a living planting, with the labor primarily done by indentured servants or low wage workers, possibly slaves, from the local population. (I say slaves because although slavery was not officially legal in England or it's colonies at this time, there have been historically a lot of situations that are essentially slavery with some thin veneer of justification, especially when you're occupying a country, and you can make any law you want about requiring people to work for you for nothing, or the next thing to nothing.) To top this off, he was either experimenting on these workers with his favorite tropical disease, or using them to incubate it so that he could keep a stock of the infectious material on hand.

This is how Smallpox stock used to be carried overseas: A chain of people would be infected with a diluted or weakened virus. When one person's symptoms would start to wane, the fluids from their open sore would be transferred via a cut in the skin to the next person in line, who would carry the infection until they began to recover. In the transfer of smallpox for the purposes of creating vaccinations and inoculations, these were volunteers. The carriers also benefitted in many cases from being inoculated in the process, since these cases of smallpox were milder than the wild variants, and being a carrier would give you about the same immunity as an inoculation of the day.

Now, we have refrigeration, glycerol stocks, the ability to use only portions of viruses (usually the proteins in their outer shell) in vaccines and most importantly, sterile fucking needles. I will never be leaving this century, even though we do have covid.

All this to say that Culverton Smith can rot in hell, but I also wanted to cover Watson: why did he write this case up?

Watson's Writing

For those of you who have made it this far into my reread without knowing what is to come: The Final Problem, in which Holmes dies, will occur in April of 1891. All Holmes short stories, and the remaining two novels, were published after this date. Presuming that my date of 1890 is correct for this story (which we can, and will, revisit later as it was NOT my initial impression of the timeline), we can presume that Watson had reasons for not publishing it in his initial collection of 24 short stories, likely grief. Thinking back on this time would have been extremely painful from a variety of directions: as the months go on and on he's further convinced that Holmes is not faking it this time, and Watson probably desperately wished that he was.

Then too, despite the fact that Watson closes the story abruptly without describing his emotions at Holmes' deception, we can deduce them. He's insulted - despite Holmes' words that he never doubted his professional abilities, just his ability to lie, Holmes still disparaged him. He's angry - Holmes has shut him out of his plans and made him believe for the better part of three or four hours that he was about to lose his best friend. He's frustrated because despite the illness being an act Holmes is still harming himself with his denial of his body's limits, i.e. that a human can die if they're dehydrated for three days, and also his casual use of poisons. Belladonna, it turns out, is not good for your eyes, which is why we don't use it anymore, aside from the hideous toxicity.

Watson has been a prop in Holmes' stagings of case conclusions before, but there's a vast difference between being framed for breaking a bowl and playing along, and being deceived, berated, insulted, and isolated to ensure that you play the part correctly. There is a definite possibility that they did have a fight over this - even Baring-Gould's timeline has a gap of over a month between this and the next recorded case. It isn't an unusual amount of time, as no doubt Holmes did not always have cases that were cinematic enough to make the cut, and also Watson had a business and a household to attend to, but it's enough time for them to pointedly not see each other, and for Watson to forgive him and come around for a post Christmas visit.

Ask a microbiologist: WTF is Smith doing with his jars of bacteria?

Hello Tumblr, I grow germs for a living. And based on the description of Smith's lab / study I have a few questions, namely, how is he storing his bacteria? Based on the jars and bottles that he refers to as his "prisons" he's keeping them at uncontrolled room temperature. This probably tracks with best practice at this time, as refrigeration was based on putting things in a box with ice, and iirc although bacteria were known to be the drivers of spoilage, the idea that they would grow, and die, slower at lower temperatures was not part of professional microbiology at the time.

Also based on Smith's own words, he's storing the bacterial colonies in agar, which matches with modern methods... sort of. Agar is solid at room temperature, and when it's liquid (at about 100 Celsius), it's too hot for most bacteria to survive in. This is important because the description of these jars and bottles appears to imply that they are filled with solidified agar, and there's really no reason Smith needs a full jar of solid agar to keep his bacteria in: when we keep bacteria in a liquid it's called a broth and does not have agar in it, because we want it to remain a liquid.

Yes, Smith could be doing a fairly standard setup where he pours a quarter inch of agar into a vessel and, when the agar is solid, "plates" bacteria on top of it. The description does not unambiguously rule it out. But if he's trying to preserve his bacteria by entombing them in solid agar, and then melting the agar to retrieve them, it's a lot funnier. Mostly because it would mean that his pet bioweapon from Sumatra isn't viable anymore.

#Letters from Watson#The Dying Detective#Crimes in Context#crimes against humanity again I'm afraid#human experimentation#self poisoning for reasons of being an extreme dumbass#look another story I coincidentally have professional knowledge vaguely related to

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still reading my book on medical experimentation during the XVII and XVIII century, and I reached a surprising part: the inoculation of smallpox, that was some kind of a vaccination process, but a bit more dangerous. It sparked a great debate over the State risking people's lives to prevent an epidemic event, can it do it or not? And can a parent risk the life of their kid (incapable of consent) to maybe prevent them getting really sick in the future? And that political view saved many many many lives, but there were many deaths too.

I don't think the debate makes as much sense now as it used to, as the rate of death caused by vaccines is close to non-existent, but if I was during those times, would I keep the same idea? I'm not sure.

The argument used for the inoculation was the fact that it could be conceived to consider smallpox epidemics as a battle against an enemy, and that to defend the country people had to get vaccinated just like soldiers were requested to fight.

The question of the "low risks for a certain event, versus high risk for an uncertain event" has been plaguing us for centuries.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi hi hello I figured that perhaps you would enjoy hearing my puppet history theory because I have nowhere else to put it.

I'm thinking that perhaps the professor and the substitute really DID have a Jekyll and Hyde split. If the substitute was a hologram made from the professors hope and dreams and stuff (I admittedly forget the exact wording) maybe... maybe the professor's desire for revenge was extremely strong in the moment he was betrayed. Maybe all the knowledge that he was purposefully sent back in time and accidentally murdered stayed with the substitute.

Maybe the actual professor, with his Dino parents, literally cannot remember that Ryan is the reason he very nearly died, because that part of his mind became part of the hologram.

I mean, he probably (probably) would forgive Ryan bc otherwise how would he have met his parents!

But yeah I don't know if this is the sort of thing that would play into the next season or not! I just wanted to share a thought :)

hi hi! hello!! i am LOVING THIS!!

i think the idea of the professors personalities literally splitting into two different people is such a cool concept. it definitely fits too! the professor is very nice and sweet, especially when ryan and the guests say that theyre nervous or stupid, but he also has a nasty side that comes out when ryan is, uh, being ryan? and sometimes comes out when guests answer questions (puting in trick questions, asking if they would inoculate their troops in the smallpox american revolution episode, exc).

i would definitely say that the substitute definitely characterizes the nasty side of the professor the best, becuase he really just takes the dial of nasty up to a 10.

and obviously everything we've seen from the dino professor has been really sweet.

I would like to think that the dino professor does knows what happened in the s4 finale, becuase that makes it more impactful the fact that the professor still forgave ryan after ryan (kinda, and unknowingly) had him killed. But it is possible that the dino professor didnt know what ryans involvement was! it wasnt explicitly stated, and who knows if the professor could really remember what happened while he was possessed. its possible that everything after he got possessed is blank. or he could have had memory loss after, you know, falling from the sky and being eaten by a fucking t rex.

I love the idea of the substitutes origin story, being that the professor was just so angry at ryan for betryaing him that he 🕯manifested🕯 a revenge hologram to beat ryans ass.

i also like the idea that all the parts that are nasty/hate ryan are stuck with the substitute, and all the parts that are nice and sweet are stuck with the dino professor!! and maybe if the substitute and professor ever interact, they both realize what is going on, and that they are both parts of a whole.

i also think the professor would forgive ryan either way because the professor finally found his family :)

#thanks for the ask!#puppet history#watcher#watcher entertainment#shane madej#ryan bergara#we are watcher#the professor

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

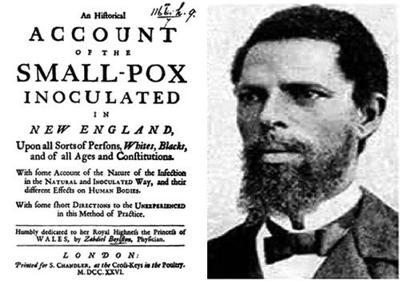

[The slave] answered both Yes and No [when asked if he had had smallpox] and then told me that he had undergone an Operation which had given him something of the smalpox & would forever praeserve him from it; adding that it was often used among the Guaramantese & whoever had the courage to use it, was forever free from the fear of contagion.

Onesimus was speaking of inoculation against smallpox, a successful preventive measure that was widely practiced throughout Africa. Smallpox inoculation took various forms, but the common denominator was that a small amount of the pus in scabs or other infected matter from someone with smallpox was deliberately introduced into the broken skin of a well person. This “variolation,” as Mather called it, evoked mild symptoms, followed by permanent, complete immunity, the Holy Grail of smallpox prevention for Western doctors and scientists. Onesimus showed Cotton Mather the technique used by those in his native country.

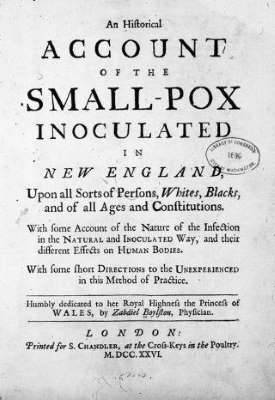

When a smallpox epidemic revisited Boston in the summer of 1721, Cotton Mather and his clerical brethren called for a mass inoculation of the people of Boston. However, the city’s physicians, led by William Douglass, resented being told by a gaggle of ministers that Africans had devised the panacea they had long sought. Zabdiel Boylston was the only physician to embrace inoculation, but not before testing it on 2 black slaves, then 248 more—as well as his own six-year-old son. Boylston then proved they had achieved immunity by exposing them to cases of smallpox.

The physicians’ resistance turned uglier—and violent. The popular press played no small role, serving as the battleground while doctors condemned variolation because it was the laughable, “unchristian” product of occult African practices. The fact that inoculation worked seemed not to play into physicians’ assessments, and their bitter attacks were not confined to the intellectual sphere: A lighted grenade was thrown into Mather’s house, along with a note declaring, “Cotton Mather, You Dog, Dam You: I’ll Inoculate you with this, with a pox to you.” This prompted him to complain, “I do not know why it is more unlawful to learn of Africans, how to help against the Poison of the Small-Pox, than it is to learn of our Indians, how to help against the Poison of a Rattle-Snake.”

In the end, the obvious reduction of death rates—from 14 percent to less than 2 percent—convinced doctors that inoculation was the city’s savior. Approximately 8,000 Bostonians became ill and 844 died; but while one in every nine untreated patients succumbed, only one in every forty-eight inoculated people was stricken.

Mather made a scientific report to the Royal Society in 1722. By 1750, inoculation was standard in America and Europe, as it long had been in Africa. Historians hailed it as “the earliest important experiment in America in preventive medicine,” but Onesimus came to share the fate of nearly every slave who contributed to medical research: facelessness.

#onesimus#smallpox#18th century#medecine#healthcare#racism#health#book : medical apartheid#Cotton Mather#William Douglass#Zabdiel Boylston#slavery#abuse#usa

1 note

·

View note

Text

South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation by Imani Perry

In the light, the corners crinkle. Feet hurt; life is a hustle. And that is Atlanta, too. There are lots of poor folks, particularly among the residents whose families have been there the longest. And whether it's in comparison to the nouveau riche or the old money, there is a resentment there as well as an attraction to the unfulfilled promise. The kids who wander around Lenox mall, often with very little in their pockets, have eyes filled with possibility. Hotlanta, ATL, ATLiens, ALANNA. . . the major metropolis of the South doesn't have a sufficient mass transit system or a polyglot culture yet. What it does have is a lot of really nice shit. And listen, dirt roads will not let you forget to appreciate that. (King of the South, p. 151)

***

That's who my people are. You hold your people close, but that, too, is a matter of understanding that they have been ripped out of your arms again and again over generations: sold away, killed by a grinding gear, a careening car, off in the labor camp, off on the chain gang, down from the lynching tree, away to the prison, dead from the sugar, from sepsis, from cancer, from a broken heart. The way life kills, with unapologetic abandon, is precisely why we hold each other so close. And get so angry when our love is riven. In Ralph Ellison's "Harlem is Nowhere," he thinks about how the Black Southerner is ill equipped for the North. According to Ellison, his subtle devices become laughable or even simpleminded there. I doubt that was true, even at the time. But in any case, a Black mind built to handle absurdity is a wonderful thing to maintain. And you need your people to show you how. (More Than a Memorial, p. 156)

***

The driver's gentility, despite the fact that he could have, could still, string me up without the world flinching? That toothless smile that could easily accompany either mirth or murderousness, depending on the eyes? This is what Black folks mean when we say we prefer the Southern White person's honest racism to the Northern liberal's subterfuge. It is not physically more benign, or more dependable. But it is transparent in the way it terrorizes. You never forget to have your shoulders hitched up a little and taut, even (and especially) when they call you "sweetheart." Cold comfort. (More Than a Memorial, pp. 168-69)

***

In the town cemetery, Jonathan Edwards is buried. A president of Princeton, father of the Great Awakening, he met his maker after a bad smallpox inoculation. The sarcophagus, heavy gray and stone, bears a few stilted words. It belies the man. Edwards always had a great deal to say. He wrote on everything. And among his possessions, on the other side of a paper that he had cut into quadrants to write four good sermons, was a bill of sale for an African woman named Venus. What a fascinating example of reuse and resourcefulness: a sermon on top of human trafficking. Historians know nothing of the transit of Venus. Just that she was here and some other there, as Edwards preached the imminent destruction of a reprobate American people who yelled "What shall I do to be saved?!” He thought he knew. (Pearls Before Swine, pp. 179-80)

***

Keep going and make a left on Calhoun, named for, you already know, the South Carolinian vice president of the United States who loved slavery and built the architecture of Indian removal to the West. If you took a right, you would eventually come to Liberty Square. But left, you get to Mother Emanuel Church. Long before Dylann Roof came, I had visited Mother Emanuel Church. As with Savannah's First African Baptist, it is hallowed ground, a church made by a fire-and-brimstone resistance. The self-effacement of the Black and holy is only one side of the story, and if you think all they ever did was pray and forgive, you really do not know the story.

Denmark Vesey, one of the South Carolina's most significant enslaved insurrectionists, was once a member of Mother Emanuel. It had been founded in 1816. City leaders forced them to close their doors in 1818. Too much freedom happened there. And after Vesey's revolt, the building was burned to the ground in 1822, only to be rebuilt. The parishioners persisted.

But you also have to understand that, before Dylan Roof, the termites had taken over. They had eaten Mother Emanuel from the inside out. The wood could have been struck, and it would have given way, bending back into the imprint of a hand or a foot. History sometimes tends and sometimes distends. Sometimes repairs are done to physical structures that also ought to be done to human ones. And Dylann Roof is and was the product of an American house eaten out by its choices and built atop the graveyard of what came before. He, too, was called an outsider by locals, rather than an alarming testimony to American violence. This vanity of innocence is like guarding a gate when the warriors are already inside.

Roof says he thought that his prison sentence would not be carried out because of the coming race war. Denmark Vesey could never have approached "the Rising," what he and his compatriots called their planned slave insurrection, with such confidence. It was always a gamble for freedom. Vesey had bought his own freedom with his earnings from a local lottery, but hadn't been able to free his first wife and children, or the members of his church. The revolt he planned had the ultimate goal of, after freeing the enslaved, sailing to Haiti. The plan was squashed before it began. Thirty-five Black people, Vesey among them, were hanged in penalty for plotting their freedom.

Roof is alive. I'm not saying he shouldn't be, just that he is.

Historians think Vesey was born in Bermuda in 1757. He was sold to a planter in Haiti, who ultimately returned Denmark to his original owner because he had epilepsy. Once Vesey's master settled in Charleston, a cosmopolitan hub, Vesey became literate. At a crossroads of history, his story is yet another reminder of the breadth of the antebellum Southern world. After Vesey was executed, one of his sons was deported to Cuba. One of his wives went to Liberia. One of his children helped rebuild the historic African Methodist Episcopal Church, where Roof enacted a time-warp revenge against Black freedom.

Long before Vesey, there was the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, in 1739. Those insurrectionists, led by an enslaved Angolan named Jemmy, planned to go to Florida, another nation then, where freedom had been promised. But they were intercepted and killed, or deported as slaves to the Caribbean. Prohibitions on gatherings, education, and group movement for Black people were legislated. A ten-year moratorium on importing Africans was implemented. The point is that there were, of course, cycles of repression and cycles of resistance. I suppose the thing I most want to say is that it is rarely acknowledged that every time that group of parishioners gathered in Mother Emanuel, they stood in a tradition of refusing to be rendered soulless and unfree. No gentrifiers, no hierarchies, no displacement, no new arrivals, and no, not even massacres that laid bodies low, one on top of another, can erase that. Their testimony is already embedded in the land. (Home of the Flying Americans, pp. 276-78)

***

I cannot help but think about sweetness born of the violence of slavery as a metaphor for New Orleans, which is a cradle holding together the South and its strands at the root. Like its native drink, a Sazerac, it's sweet and strong enough to knock you on your ass or knock you out. And of course, as often as people try to cut it off from the rest of the South, it functions like a phantom limb, one that we feel everywhere in the fabric of the country, even when we don't see it right there on us. The graves in New Orleans sit above-ground because of potential flooding. And so the dead are raised and decorated with stunningly bright mausoleums and abundant flowers. The spirits hear the music and might be swaying, too. New Orleans choreography often feels like a dance at the Kongo cross-roads. (Magnolia Graves and Easter Lilies, pp. 342-43)

***

Whatever the case, visiting holy people soothes my spirit. I won't share the details of what [the babalawo, a Yoruban priest] told me; just know that it was all true and useful. And if there is a dramatic difference, besides language, between there and here, it is that the Cubans, no matter how white their skin, do not deny the fundamental Africanness of who they are the way Southern White people do, assiduously. Visiting this babalawo helped me think about that fact. What exhaustion must be required to passionately deny that which has shaped so much of who you are? Maybe this is part of the White evangelical discipline of prayer. To absolve the self-denial. To drown it in catharsis. White Cubans have no need. But I do not think that is a mark of virtue as much as it is a marker of nationalisms. Countries get accorded races, no matter how multiracial they are. And Cuba is Blackish brown. The US is White; we (Black people) are its built-in other. (Paraíso, p. 367)

0 notes

Text

FUN OCCULT FACTS!

🙄 Aleister Crowley was against vaccines, particularly smallpox inoculation. This was because he believed such diseases would, by culling the weak, strengthen the human race. Naturally, like most people who say such things, he was absolutely certain that he could be counted amongst the strong who would survive. 🙄

I’ve seen a small influx of people into pagan spaces hoping to find a religious vaccine exemption. Weirdly enough, they’d be better served by cozying up to Crowley, I guess.

I’m still (mostly) on hiatus from writing here. The cyberpunk game I made (and am now running) takes up a lot of my time, and it’s unclear if it’ll exceed its planned four-month run.

#witchblr#witch#witchcraft#occult#magic#pagan#vaccine#covid#antivaxxers#Aleister crowley#crowley#thelema#eliza.txt#eliza reads

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An African slave taught America to vaccinate from smallpox

In April 1721, a smallpox outbreak swept through Boston. This was the latest in a string of six epidemics that had, since, 1630, laid waste to the city. Cotton Mather, a local slave owner and preacher, claimed to be in possession of a way of preventing contraction of the disease. Mather, who had first come to public prominence as one of the thinkers behind the Salem Witch Trials, had gotten the method from one of his former slaves.

Fifteen years earlier, Mather’s congregation had purchased for him an African slave, a “Young Man, who is a Ne***, of a promising aspect and temper.” Mather named him Onesimus, after a slave in the Bible whose name meant “useful.” Mather described Onesimus as being Guramantese, but it is unclear what ethnic group exactly this refers to. One account suggests them to be the Garamante, who correspond to the Berber peoples of southern Libya. Another places Onesimus among the Coromantee from the coastal areas of modern-day Ghana.

Since smallpox was a common scourge in the 18th century, a slave’s value was predicated on his ability to stave off infection. One of the features of smallpox is that a person can only contract it once. Mather asked Onesimus if he had ever suffered from the disease. Mather describes the conversation that followed:

“Enquiring of my Ne*** man, Onesimus, who is a pretty intelligent fellow, whether he had ever had the smallpox, he answered, both yes and no; and then told me that he had undergone an operation, which had given him something of the smallpox and would forever preserve him from it; adding that it was often used among the Guramantese and whoever had the courage to use it was forever free of the fear of contagion.”

The operation Onesimus described was a common procedure in certain parts of the world. What happened was that pus from an infected person was rubbed into an open wound of a person uninfected with smallpox. If one survived this procedure, one was thus inoculated against smallpox, and could never contract it. The procedure was done in different places. In Africa, in China, in India, in the Ottoman empire. Most accounts place the origin of inoculation in either China (where they would blow scabs up a person’s nose) or India, and in both places, it was largely a secret procedure whose technique was passed down mostly in families.

By 1721, inoculation was not entirely unknown in the Western world. It was practiced in Wales and Scotland, and slave traders were known to look for inoculation scars on their slaves. The prices of slaves with the scars would then be hiked up. However, in colonial Boston, as smallpox decimated the population, very few of the inhabitants knew about the procedure. In haste, Mather wrote to the city’s physicians, urging them to perform the procedure so as to save lives.

The resistance was immense. Local newspapers vilified him. A grenade was thrown into his house, the throwers angered that he had dared to inoculate his own son, who almost died. His fellow ministers decried his sin, declaring that it was against God’s will to expose his creatures to dangerous diseases. All the physicians in the town, except one, Zabdiel Boylston, refused to carry out the procedure. The moment Boylston announced his intention to do so, Bostonians took to the streets in protest. Cue the first manifestations of the American anti-vaxxer movement.

The first people Boylston inoculated were his son, and two of his slaves. He was promptly thrown in jail, accused of recklessly trying to spread disease

At the core of Boston’s resistance to inoculation was a heavy racial bias. Mather had made no secret of the fact that he learnt of the procedure from his former slave, and this was the stick the town used against him. Inoculation existed in scientific documents where it was described as a “heathen practice” from Africa. The white puritans of Boston refused to defile their bodies with African heathenisms. To do so would be against God’s will, against predestination. Let God’s will be done. If the Lord God Almighty had decided that it was your day, that was it. Amen. As Peter Manseau notes, “This was not just a health crisis; it was also a theological one. The majority of Puritan clergy regarded the epidemic as divine will.”

The bias made the impact of the smallpox more severe than it should have been. In the end, Boylston was able to inoculate only 248 of the city’s 11,000 residents. Of these 248, only six died, a rate of one in 40. For the rest of Boston, the mortality rate was one in seven, with 844 people dead by the end of the epidemic.

#boston#african americans#north african#berber#berbers#small pox#onesimus#african#african culture#vacciantions#inoculation#boylston#africa#china#wales#scotland#guramantese#1721#india#ottoman empire#new england#libya#smallpox#zabdiel#zabdiel boylston#kemetic dreams#white purtains#racism#white racism#european racism

874 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about the fact that the word vaccine comes from the latin word for cow, vacca; “vaccinae” basically means “from/of a cow”. because it once referred to cowpox as an inoculation against smallpox. this in the context of pathologic’s mother boddho…. almost too perfect a connection

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Conan Doyle on Anti-vaxxers

From time to time some champion of the party which is opposed to vaccination comes forward to air his views in the public Press, but these periodical sallies seldom lead to any discussion, as the inherent weakness of their position renders a reply superfluous. When, however, a gentleman of Colonel Wintle's position makes an attack upon what is commonly considered by those most competent to judge to be one of the greatest victories ever won by science over disease, it is high time that some voice should be raised upon the other side. Hobbies and fads are harmless things as a rule, but when a hobby takes the form of encouraging ignorant people to neglect sanitary precautions and to live in a fool's paradise until bitter experience teaches them their mistake, it becomes a positive danger to the community at large. The interests at stake are so vital that an enormous responsibility rests with the men whose notion of progress is to revert to the condition of things which existed in the dark ages before the dawn of medical science.

Colonel Wintle bases his objection to vaccination upon two points: its immorality and its inefficiency or positive harmfulness. Let us consider it under each of these heads, giving the moral question the precedence which is its due. Is it immoral for a Government to adopt a method of procedure which experience has Proved and science has testified to conduce to the health and increased longevity of the population? Is it immoral to inflict a Passing inconvenience upon a child in order to preserve it from a deadly disease? Does the end never justify the means? Would it be immoral to give Colonel Wintle a push in order to save him from being run over by a locomotive? If all these are really immoral, I trust and pray that we may never attain morality. The colonel's reasoning reminds me of nothing so much as that adduced by some divines of the Scottish Church, who protested against the induction of chloroform. "Pain was sent us by Providence," said the worthy ministers, "and it is therefore sinful to abolish it." Colonel Wintle's line of argument is that smallpox has been also sent by Providence and that it becomes immoral to take any steps to neutralise its mischief. When once it has been concisely stated, it needs no further agitation.

In the second place is the mode of treatment a success? It has been before the public for nearly a hundred years, during which time it has been thrashed out periodically in learned societies, argued over in medical journals, examined by statisticians, sifted and tested in every conceivable method, and the result of it all is that among those who are brought in practical contact with disease, there is a unanimity upon the point which is more complete than upon any other medical subject. Homoeopath and allopath, foreigner and Englishman, find here a common ground for agreement. I fear that the testimony of the Southsea ladies which Col. Wintle quotes, or that of the district visitors which he invokes, will hardly counter-balance this consensus of scientific opinion.

The ravages made by smallpox in the days of our ancestors can hardly be realised by the present sanitary and well-vaccinated generation. Macaulay remarks that in the advertisements of the early Georgian era there is hardly ever a missing relative who is not described as "having pock marks upon his face." It was universal, in town and in country, in the cottage and in the palace. Mary, the wife of William the Third, sickened and died of it. Whole tracts of country were decimated. Now-a-days there is many a general practitioner who lives and dies without having ever seen a case. What is the cause of this amazing difference? There is no doubt what the cause appeared to be in the eyes of the men who having had experience of the old system saw the Jennerian practice of inoculation come into vogue. When in 1802 Jenner was awarded £30,000 by a grateful country the gift came from men who could see by force of contrast the value of his discovery.

I am aware that Anti-Vaccinationists endeavour to account for the wonderful decrease of smallpox by supposing that there has been some change in the type of the disease. This is pure assumption, and the facts seem to point in the other direction. Other zymotic diseases have not, as far as we know, modified their characteristics, and smallpox still asserts itself with its ancient virulence whenever sanitary defects, or the prevalence of thinkers of the Colonel Wintle type, favour its development. I have no doubt that our recent small outbreak in Portsmouth would have assumed formidable proportions had it found a congenial uninoculated population upon which to fasten. In the London smallpox hospital nurses, doctors and dressers have been in contact with the sick for more than fifty years, and during that time there is no case on record of nurse, doctor, or dresser catching the disease. They are, of course, periodically vaccinated. How long, I wonder, would the committee of the Anti-Vaccination Society remain in the wards before a case broke out among them?

As to the serious results of vaccination, which Colonel Wintle describes as indescribable, they are to a very large extent imaginary. Of course there are some unhealthy children, the offspring of unhealthy parents, who will fester and go wrong if they are pricked with a pin. It is possible that the district visitors appealed to may find out some such case. They are certainly rare, for in a tolerably large experience (five years in a large hospital, three in a busy practice in Birmingham, and nearly six down here) I have only seen one case, and it soon got well. Some parents have an amusing habit of ascribing anything which happens to their children, from the whooping-cough to a broken leg, to the effects of their vaccination. It is from this class that the anti-vaccinationist party is largely recruited.

In conclusion I would say that the subject is of such importance, ancestors call and our present immunity from small pox so striking, that it would take a very strong case to justify a change. As long as that case is so weak as to need the argument of morality to enforce it I think that the Vaccination Acts are in no great danger of being repealed.

It was Yours faithfully,

A. CONAN DOYLE, M.D., C.M.

Bush Villa, July 14th, 1887(x)

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

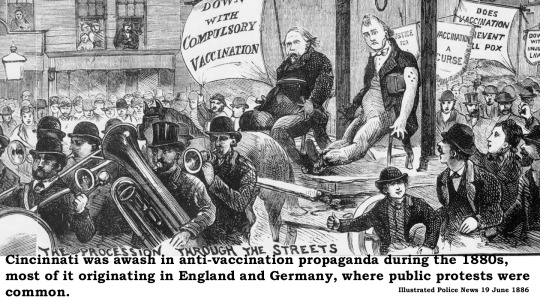

In The 1880s, Cincinnati Strongly Supported Vaccination To Fight A Deadly Virus

Smallpox was dreadfully common in the 1880s, killing hundreds of Cincinnatians every year. Health officers confined anyone who contracted smallpox, and their entire family, to the pest house, fumigated their residence, and waited for everyone to die. Vaccination was available and effective, but an international movement worked to sour public opinion on this preventive method.

Most of the anti-vaccination propaganda throughout the 1880s originated in England and Germany. With a substantial German population, one might expect Cincinnati to be fertile ground for planting the anti-vaccination impulse. In general, this was not the case. A couple of Cincinnati’s German-language newspapers groused about the “vaccination humbug,” and the Catholic Telegraph, with a heavy German readership, sat on the fence for decades, but they were overshadowed by the majority of Cincinnati newspapers.

A fair summary of Cincinnati opinion in the 1880s was provided by the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune [11 May 1882]:

“A parcel of cranks in this country and England have been preaching against vaccination. Their false and foolish pamphlets are flying in every mail. If it were not for vaccination, the small-pox would be a devastating plague. The fools who are fighting the scientific defense against it, are flagrant mischief makers, and amount to public enemies.”

That sentiment was echoed by the Cincinnati Daily Gazette, normally a political opponent of the Commercial Tribune, on 20 February 1882:

“It is the darling object of the ‘antis’ to abolish compulsory vaccination in Germany and England, and to prejudice people everywhere against it. They are no doubt sincere, but their misrepresentation of facts and distortion of statistics appear to show that they think the end justifies the means. A more cruel work was never undertaken than this deliberate attempt to induce whole communities to take a course which is little better than suicide.”

By 1880, vaccination for small-pox was anything but new. Vaccination in one form or another had been practiced in Asia and Africa for centuries before Western medicine paid attention. Edward Jenner, an English physician generally credited with creating the first safe vaccine, inoculated his first patient in 1796. Cincinnati newspapers began promoting vaccination as early as 1805.

Vaccination, although commonly practiced, was mysterious and haphazard throughout the 1800s. No one understood the mechanism that propelled smallpox into such a lethal disease. Viruses were not discovered until well into the Twentieth Century. Medical doctors lacked a monopoly on vaccinations – or any medical treatments for that matter. Barbers, midwives, patent-medicine quacks and sometimes outright amateur inoculators wandered the city “vaccinating” patients for a small fee. The result was a morass of misinformation caused by “vaccinated” residents who died from smallpox. On investigation, it was proven that these unfortunate victims had been so improperly exposed to the smallpox virus that they developed no immunity at all.

There was no standardization and no quality control because no one, at that time, had any idea what was in the vaccine. This uncertainty spawned a plethora of myths, repeated continually by the anti-vaccination organizations. The Cincinnati Gazette [24 February 1882] summarized the anti-vax arguments:

“An effusion which reached us yesterday from the office of the Anti-Vaccination League endeavors to prove that it is foolish to be alarmed over the prevalence of smallpox, since it is not nearly so ‘catching’ as most people believe; that it does not increase the number of deaths, but merely replaces other diseases which would be present did it not appear; that vaccination is as much a humbug as magical arts, resulting only in discomfort and danger to the person who undergoes the operation; and, finally, that the attacks of smallpox are limited to a small portion of any population, chiefly its dregs.”

All this debate swirled through the pages of local newspapers while residents died by the hundreds. In 1882, Cincinnati lost 1,249 people to the depredations of smallpox. Periodic outbreaks were common: 640 deaths in 1868; 1,179 deaths in 1871; 927 deaths in 1876. The Cincinnati Post [23 November 1882] claimed most of the deaths from smallpox afflicted the immigrant community:

“Foreigners coming to Cincinnati refuse to be vaccinated. It is feared that small-pox will rage disastrously among this class of citizens. A prominent Hebrew said to a Penny Paper reporter yesterday that he would not be surprised to see every Russian refugee in this city die of small-pox this winter. They live in thickly populated tenement houses, and refuse to be vaccinated, even so far as to give up their positions in stores and factories where vaccination is made obligatory.”

Many of Cincinnati’s fatalities involved unvaccinated children. In his annual report for 1882, Cincinnati health officer Dr. D.D. Bramble emphasized this horrendous statistic:

“It is in the young, unvaccinated portion of our population that small-pox mortality chiefly occurs. Statistics show fifty-six per cent of deaths are in children under five years of age, and as much as seventy per cent in children under ten years that have neglected vaccination. It is needless for me to illustrate how recklessly the loathsome contagion is spread among the people.”

And, of course, there were ironies. As reported in the Commercial Tribune [12 October 1883]:

“The London Medical News reports the suicide of a leading anti-vaccine agitator in England. Last summer the small-pox broke out in his family and carried off his wife and three children. The loss preyed upon his mind, and he completed the extinction of his family by self-destruction.”

Although Cincinnati officials and the State of Ohio legislature declined to mandate vaccinations for everyone, eventually the schools and employers required vaccination, which amounted to the same thing. Data piled up ever higher to prove that vaccination really did stop the fatal consequences of smallpox, typhus and other diseases. The Enquirer [8 December 1882] stated its hope that logic, facts and proof would ultimately prevail against the disinformation, rumors and balderdash that constituted the anti-vaccination platform:

“During his official term the Health Officer has examined into one hundred small-pox cases for the purpose of gathering some data regarding the efficacy of vaccination. Of the one hundred people suffering from the loathsome disease he found that seventy had never been vaccinated, while the remaining thirty had suffered the simple ordeal so long ago that its virtue had entirely died out. These figures ought to prove a blow to the anti-vaccination society.”

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flower of Princesses

Back once again on my bullshit, today i’m obsessed with reading about Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange

This lovely lady was born in 1709 and died in 1759. Ready for some fun facts?

~Anne was taught music by Georg Friedrich Händel. Although he didn’t like teaching he said he would “make the only exception for Anne, flower of princesses”

~Anne contracted and survived smallpox, then went on to help popularize an early type of inoculation against smallpox

~In 1727 she was created the Princess Royal, a title that hadn’t been used since 1642

~Anne refused to marry King Louis XV of France because she would not convert to Roman Catholicism.

~She married William IV, Prince of Orange in 1734 at a mature 25 years old. Händel composed Parnasso in Feste in honor of the wedding. I now have a goal to have a famous composer compose a piece just for my wedding, is that setting my sights too high?

~Anne was arrogant and believed that the British were superior to the Dutch, which obviously made her unpopular with many of her courtiers

~She died of dropsy in 1759 while serving as regent for her son

~Princess Anne, Maryland is named after her!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here we go...

"Those who don't learn from history are destined to repeat it." Right? That's the saying? I've seen versions of that tossed around a lot (two words) on social media over the last year or so. Usually accommodated by some photo of a screaming eagle ridden by a president wrapped in a flag with lasers shooting out of their eyes...or something like that.

Anyway, that was SO 2020. Now we have vaccinations and mask mandates because of a legitimate world public health risk(Keyword: "world"). I've also seen those same people post lately about segregation, freedoms being taken away, and not being treated equally. They're also planning protests and demonstrations so they can be heard. So. Much. Irony.

Staying the course, the same thing happened when the Supreme Court issued a historic 1905 ruling that legitimized the government’s authority to “reasonably” infringe upon personal freedoms during a public health crisis by issuing a fine to those who refused vaccination. 116 years ago. We've learned a lot in that time, and science has evolved through technology, and technology is producing technology at a faster rate every day. Sometimes it's easier just to ignore everything and go yell at a cloud. But surprisingly, just because you stopped evolving your thinking and way of life, that didn't make the issues you have with living in the present go away.

Anyway, let's do that. Let's move forward and learn from history and evolve. This morning I chose an excerpt found at the Library of Congress. Apparently, it's a good library. I wanted to learn about presidents. But I couldn't decide on who. If you ask anyone, "Who is the greatest President in the history of the United States?" - my guess would be that George Washington would make the Top 4. After all, he is on the literal Mount Rushmore of presidents. Figured that's a good place to start.

He was considered a military genius. So much, that The Continental Congress commissioned George Washington as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army on June 19, 1775. Washington was selected over other candidates such as John Hancock because of his previous military experience and the hope that a leader from Virginia could help unite the colonies.

In came the British and a new virus called Variola (smallpox). Smallpox is still around, but usually in 3rd world countries. Don't worry though, much like the British, you've had your vaccine (you got it to go to school) and have an immunity built up to fight it. You see, historically, according to the CDC the vaccine has been effective in preventing smallpox infection in 95% of those vaccinated. In addition, the vaccine was proven to prevent OR SUBSTANTIALLY LESSEN infection when given within a few days after a person was exposed to the variola virus. That gave them an enormous advantage against the vulnerable colonists in this revolution. But George had a plan to level the playing field...

"...Weighing the risks, on February 5th of 1777, Washington finally committed to the unpopular policy of mass inoculation by writing to inform Congress of his plan. Throughout February, Washington, with no precedent for the operation he was about to undertake, covertly communicated to his commanding officers orders to oversee mass inoculations of their troops in the model of Morristown and Philadelphia (Dr. Shippen's Hospital). At least eleven hospitals had been constructed by the year's end.

Variola raged throughout the war, devastating the Native American population and slaves who had chosen to fight for the British in exchange for freedom. Yet the isolated infections that sprung up among Continental regulars during the southern campaign failed to incapacitate a single regiment. With few surgeons, fewer medical supplies, and no experience, Washington conducted the first mass inoculation of an army at the height of a war that immeasurably transformed the international system. Defeating the British was impressive, but simultaneously taking on Variola was a risky stroke of genius."

Legend.

Of course, we all know the rest of the story. In 1789 he took the oath that made him the first president.

Once elected to office, no one knew what to call him though. VP Adams then proposed calling Washington, “His Highness, the President of the United States, and Protector of the Rights of the Same.” He should have been shot out of a cannon. Thankfully, George said, "How about just Mr. President?"

For more fun facts that don't require deworming, visit https://www.loc.gov/.../GW&smallpoxinoculation.html...

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When the blue checks—synecdoche for the managerial class at large—aren’t issuing sociopathic taunts to the unvaccinated, whose ranks include not only the Trumpist rubes of flyover country but also such stars of the Democratic coalition as African-Americans, the young, and people with Ph.D.s, they high-mindedly appeal to the now-trending 1905 Jacobson v. Massachusetts Supreme Court decision, which allows compulsory vaccination on the sound basis that personal liberty must have a limit if we are to live in an organized society at all. In question was the smallpox inoculation, a sterilizing vaccine (i.e., it confers immunity to the disease, not just prophylaxis against its ravages) that, notwithstanding its side effects on poor Jacobson, had existed for over a century—not a non-sterilizing vaccination with a track record of less than a year.

Because our discourse is so polarized, the “other side” (there are more than two sides) prefers to cite the never-overturned 1927 Supreme Court decision Buck v. Bell, which affirmed eugenics. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., based his judgment on the case of an institutionalized woman thought to be “incorrigible” because she’d borne a baby out of a wedlock in her teens, though it turned out she’d in fact been raped by her adoptive cousin and then committed to save her family’s reputation. Holmes, echoing the Jacobson decision’s call to civic responsibility, concludes:

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

“Muh freedumb!” indeed. The spirit of our times inclines more to Holmes’s intellectual arrogance. For example, the sitting president threatens the governors in our federalist system: “if these governors won’t help us beat the pandemic, I’ll use my power as President to get them out of the way.”

There are not only two sides. I am not anti-vaxx, not even anti- this vaxx, which I have myself received. I do not believe in a New World Order conspiracy to microchip or genocide us all. I believe only in the cynical conceit of large corporations and the flailing authoritarianism of desperate governments. There are, however, cautions voiced by dissident experts in the relevant fields that may (I am not an expert) contraindicate the present policy, to wit, it might be irresponsible and potentially dangerous to universally mandate a non-sterilizing vaccine, because it threatens to provoke mutations deadlier than those induced by the ordinary spread of the illness. A more appropriate treatment might resemble what we already do for influenza: make inoculations available (even here not mandatory) for the elderly or otherwise vulnerable and focus on treatments for the rest of the populace.

The context is sufficiently distinct to render Jacobson v. Massachusetts an irrelevant precedent, while the warning of Buck v. Bell echoes in the vicious preening of the expert class and the swaggering mandates of the federal government.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

From the people’s point of view, there was no need for the preventives that were thrust upon them. The need was wholly on the side of the medicos for some pretext for squeezing money from the people or from the government. The very first of all the prophylactics to be introduced was against smallpox, which, seen in the perspective revealed by statistics, was of little importance as a cause of death. Mr Arnold Lupton, M. P., in his book on vaccination, gives a table of deaths from various diseases in England and Wales, showing that each of five diseases, measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, diarrhoea, and cancer, caused deaths running into five figures, whereas smallpox deaths rarely ran to three figures, and disappeared entirely in the face of the rising tide of true sanitation.