Text

In 1872, Cincinnati Ground To A Halt As The City’s Horses Succumbed To A Virus

It sounds like something out of a science fiction movie. For nearly three weeks in the autumn of 1872, Cincinnati was paralyzed by a virus with no known cure.

Humans were not susceptible to this virus. It only affected horses, but the entire operation of Cincinnati life and business depended primarily on horses. When the city’s horses were incapacitated, Cincinnati screeched into paralysis.

The strange episode began one evening in October when Dan Rice’s circus rolled into town. Four of the horses showed symptoms of some sort of respiratory illness and were taken to veterinarian George W. Bowler for treatment. Dr. Bowler readily identified the affliction as the “Canadian horse disease” that was then infesting the northern tier of states but doubted it would spread beyond his stable on Ninth Street.

Alas, Dr. Bowler’s optimism was unfounded and the next few days found cases throughout the downtown area. Journalists struggled to name the disease. “Epizooty” was a common label, but newspaper reports invoked “equine influenza” or “hippo-typhoid-laryngitis” or “epiglottic catarrh” or “epizootic influenza” and even “hipporhinorrheaeirthus”! Whatever they called it, the disease would hobble a city absolutely dependent on horse power to operate at all.

Josiah “Si” Keck, presiding at the Board of Aldermen, introduced a resolution to draft squads of men for duty at the city’s firehouses. With the horses out of commission, only manpower could replace horsepower to haul the heavy steam-powered fire engines of the day. Thankfully, only a few minor fires were reported during the height of the contagion.

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer [11 November 1872], other horse-dependent companies tried different alternatives:

“The United States Express Company has prepared to follow the example of the Eastern Companies. All of their horses, twenty-two in number, being completely disabled, they will at once substitute steers, and the streets of this city will show the curious spectacle of express wagons drawn by the propelling force of a farmer’s haycart.”

Historian Alvin F. Harlow, writing in the Bulletin of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio [April 1951], noted that the bovine substitutes were simply not cut out for jobs readily accomplished by horses:

“The oxen, with great, wild, pathetic eyes, slobbering, swaying slowly through the streets, were a strange spectacle to city folk, and were followed by crowds of children for a day or two, until the novelty wore off. But as agencies of traction, they were a disappointment. Not all of them were well broken to the yoke; few men in town knew how to drive them, and as they are—with the possible exception of the tortoise and the two-toed sloth—the slowest walkers in the whole zoological category, they did not accomplish much in a day, according to city standards.”

Just think of an entire city operating on the capable talents of horses, now immobilized by an unseen microbe. Garbage piled up as the city’s sanitation wagons stood idle. “Garbage” back then meant kitchen and table scraps which, even in the chill of autumn, ripened malodorously in unattended cans. The situation was even worse at the city’s slaughterhouses. Even though the butchers had stopped working – there were no wagons available to deliver the slaughtered pork and beef – there were likewise no wagons to dispose of the offal and trimmings. The stench was indescribable.

Cincinnati’s streetcars were horsedrawn in 1872. It would be a decade before electrical trolleys debuted. The entire commuter system of the city shut down and the Cincinnati workforce, from C-suite executives to the lowliest laborers, had to hoof it. Harlow describes an exhausting scene:

“Towards dusk each evening the great trek homeward began, and from then until 9 P.M. the streets were thronged with business men, clerks, bookkeepers, warehouse and factory workers, trudging wearily. To reach their work again at 7 or 7:30 next morning, when most people's day began, soon proved too much for some of them, and they took to sleeping in their places of business; which in turn became less and less necessary, as those businesses were compelled to shut down for lack of transportation.”

Even funerals were affected. Teams of undertakers pulled hearses to the depot of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton railroad, whose tracks ran along the front of Spring Grove Cemetery. Mourners followed along on foot until the hearse was loaded on the train, then rode out for the burial. Other cemeteries put interments on hold for the duration.

The city faced the serious prospect of starvation. Food arrived in the city by rail and by river, but there were no carts to carry it from the wharf or the depot. Fresh vegetables rotted down by the river while families went hungry just a few blocks north. Farmers from the suburbs refused to bring their crops into Cincinnati for fear that their own draft animals would succumb to the dread epizooty.

As humans attempted to fill the horse’s role, every wheelbarrow in the city was drafted into use and some sold for astronomical sums. Even so, as noted by Harlow, human power had its very fragile limits:

“If the load was very heavy, as for instance, hogsheads of tobacco, massive machinery or an iron safe of a ton weight, ropes were also attached to each side of the wagon and passed over the shoulders of two files of straining men, while three or four others, their feet striving for toeholds in earth or cobbles, pushed against the wagon's tail until shoulder-bones threatened to wear through the flesh.”

Among the worst effects of the pandemic was the inability to dispose of dead horses. Horses died in Cincinnati at the rate of twenty or thirty a day at the height of the disease in November 1872, and there was nothing available to haul the carcasses out to the reduction plants, where they might be turned into soap fat or fertilizer. Alderman Si Keck, who owned one of these “stink factories,” found a partial solution by renting a small steam-powered truck from one of the city’s pork-packing plants but could still handle only a few of the equine corpses.

By the end of November, new cases and fatalities had diminished considerably. As December opened, the city was almost back to normal, with a new appreciation of the four-legged residents who truly powered our city.

Only one case of a human contracting the epizooty was recorded in 1872. Joseph Einstein was a well-known dealer when Cincinnati’s Fifth Street was the largest horse market in the United States. Einstein spent weeks, around the clock, nursing his stock and developed symptoms remarkably similar to those afflicting his horses. Several local doctors confirmed that he had somehow succumbed to the dread epizooty.

Just as mysteriously as it appeared, the epizooty vanished, and never visited Cincinnati to that degree ever again.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cincinnati Surrendered To The Automobile When Jaywalking Was Outlawed

How many Cincinnatians subscribed to Popular Mechanics magazine in 1912? And how many of those subscribers recognized, in the September issue, a tiny article on Page 414 that laid out the future of the Queen City? It all seemed so innocent:

“The city pedestrian who cares not for traffic regulations at street corners, but strays all over the street, crossing in the middle of the block, or attempting to save time by choosing a diagonal route across a street intersection instead of adhering to the regular crossing, is designated as a ‘jay walker’ in Kansas City. Kansas City recently adopted a new ordinance for the control of foot traffic as well as vehicles, and ‘jay walking’ is to be prevented as rigidly as ‘jay driving.’”

That squib appeared adjacent to another brief item on how the brand-new town of Speedway, Indiana allowed only motorized vehicles on its streets, banning anything pulled by horses. In combination, the two articles sounded the death knell for a way of life that had existed for millennia.

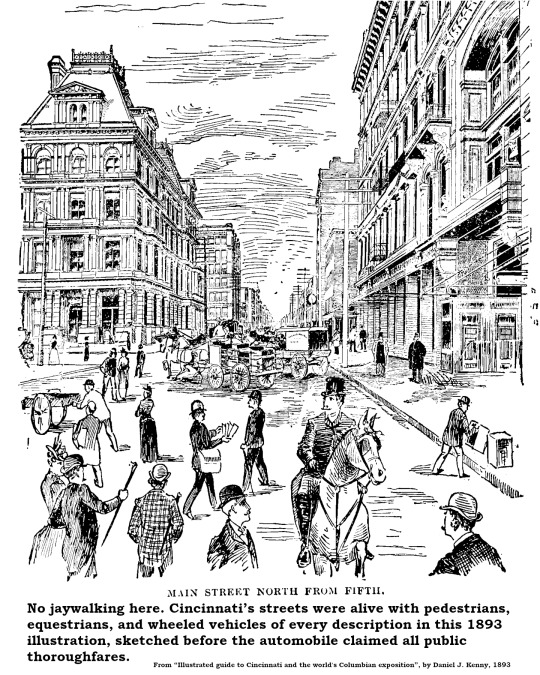

Look at the illustrations that grace the old books about Cincinnati. There is no such thing as jaywalking. The streets were owned and enjoyed by the people. Pedestrians share the road with wheeled vehicles, crossing wherever convenient, even stopping in the middle of the street to chat. Horse-drawn carriages and wagons hauled passengers and freight. Men pulling handcarts and pushing wheelbarrows dodge the throng. The only motorized vehicles were the electric street cars, and they were confined to their tracks.

During election season, Cincinnati’s streets filled with torchlit political parades. On at least one occasion, a parade filled Vine Street from Fourth Street to McMicken with chanting men waving flaming brands, lighting the clouds above with a rosy glow. When any dignitary showed up in town, they were expected to speechify from their hotel balcony and people thronged the street below, halting traffic as they cheered. People crossing the street from any direction weren’t “jay walking.” They were just “walking.” The automobile changed all that.

Horse-drawn vehicles and electric streetcars killed a fair number of people, but the motor car quickly notched more than a hundred fatalities and many more injuries every year. Local media often blamed the victims. The Cincinnati Post [8 January 1916] piled on:

“Fourth-st. is the mecca of Cincinnati’s jay walkers. Most of the jay-walking is done between Vine and Race-sts. The other day we counted 20 persons crossing the street at different points at one time – and none was using a cross-walk. Fortunately accidents are rare on this street because of the extreme care exercised by autoists.”

It appears not to have occurred to the writer that this behavior, just five years previous, would have been considered normal.

The hammer landed in 1917. Cincinnati joined the ranks of other auto-infested cities that criminalized jaywalking. The new law went into effect in May of that year, restricting automobiles to no more than 8 miles per hour in the business district and 15 miles per hour in residential districts. For the first time, pedestrians were restricted to sidewalks and crosswalks. Pedestrians – literally – fought the new law. According to the Post [23 May 1917]:

“Theodore Mitchell, 38, agent, 631 Maple-av, is the first person to be arrested on a charge of jay-walking since the new traffic ordinance went into effect. Traffic Patrolman [Edward] Schraffenberger charged Mitchell attempting to make a short cut at Fifth and Walnut streets. When reminded of his mistake, Mitchell became angry, Schraffenberger said. Mitchell, charged with disorderly conduct and violating the traffic ordinance, was cited to appear in court Thursday.”

If you’d asked the cops, however, they would unanimously aver that the chief violators were women. The Post [21 May 1917] quoted Police Lieutenant Charles Wolsefer:

“The women are awful. They just don’t pay any attention at all. Just take a look at them crossing on Race-st.”

The reporter did so, and counted 48 jaywalkers, of whom 37 were women. A few days later, another Post reporter followed another policeman on patrol who confronted 25 jaywalkers, of which only two were men.

Among the first arrested was Miss Ella Bright of 538 Howell Avenue, Clifton, a teacher at Woodward High School. Miss Bright did not care for the attitude of the city policeman who accosted her. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer [7 June 1917]:

“She declared she had been upbraided unduly by an officer because she crossed the street in a manner which was a violation of the traffic laws after alighting from a street car.”

In August of that year, Mrs. John Mongan, 4217 Glenway Avenue, Price Hill, was arrested for striking a police officer who grabbed her arm as she executed a “Dutch Cut” (diagonal jaywalking) across the intersection at Sixth & Race.

Former U.S. President William Howard Taft, then on the law faculty at Yale, was visiting his hometown that year and blithely jogged across Sixth Street near Main, only to be corralled by Officer Joseph Schindler, who gave the law professor a little legal lesson.

The Post even enlisted its “boy reporter,” 12-year-old Freddy Printz, to test the city’s ability to enforce the new jaywalking regulations. On 7 July 1917, Freddy reported his fruitless attempts to get bawled out by a police officer. Despite blatantly jaywalking at five different locations, he only earned a polite reprimand from one officer.

While the local constabulary was doing their best to enforce the new laws, the automobiles were merciless. On 21 May 1918, the Post reported on the 25th traffic fatality of the year. The victim, a 12-year-old girl, was the twelfth child killed by an automobile that year.

Curiously, although Cincinnati outlawed jaywalking, the city had omitted one very important detail that might have contributed to compliance with the new law. A letter signed only “Chicagoan” appeared in the Post on 13 June 1917. The writer suggested that, like other cities attempting to get pedestrians to cross at intersections, Cincinnati should assist pedestrians by painting white lines on the street to mark approved pedestrian crossing paths. Cincinnati’s mandatory crosswalks were unmarked!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

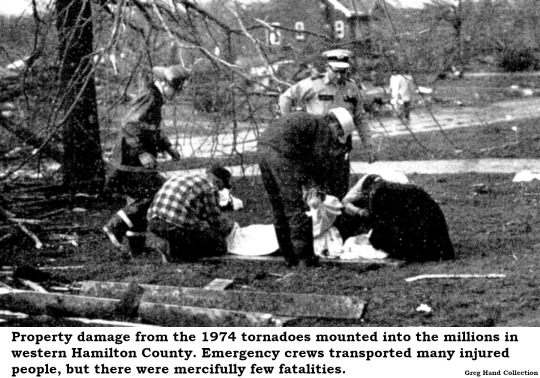

Memories From Half A Century Ago; The Cincinnati Tornadoes of April 1974

On the evening of April 3, 1974, your narrator interviewed a woman who found a perfectly new, pristinely crisp, twenty-dollar bill in her front yard. This random occurrence of good luck became newsworthy because her miraculous benefit had floated down into her yard from a passing cloud that had recently spawned an F5 tornado.

At the time, I was not a reporter exactly but everyone that evening became either a reporter or a source. The memory of that day remains so fresh and clear it seems impossible that it transpired exactly fifty years ago.

In the fading afternoon, a heavy storm blew in as I drove a clunky Ford Econoline van from the Hopple Street Viaduct onto Westwood-Northern Boulevard. I was, at that time, a senior at the University of Cincinnati desperately yearning to graduate and move on to the next chapter in my life. To cover tuition, I worked as a printer for the Western Hills Publishing Company. Our offices were on Davis Avenue in Cheviot and our printing presses occupied a floor in the historic Crosley Building on Arlington Street in Camp Washington. My duties as the junior member of the printing crew involved shuttling copy and page flats from the editorial offices to the typesetting and composing staff.

As I climbed out of the valley toward the English Woods housing development, hail scattered across the road. Hailstones rattled on the van’s roof, then pounded, then stomped. It sounded like some gremlin with a baseball bat hammering on the roof as ice balls the size of oranges smashed into the asphalt all around. Tree branches cracked and split and thatched the roadway.

Somehow, I made it to Cheviot and pulled into the Press parking lot. It was full of people, just standing around. I got out and looked at the van. The roof looked like a moonscape, there were so many dents in it.

“Hey! Look at this,” I shouted. No one turned or said a word. And then I saw why.

Stretching from the horizon halfway to zenith was the tornado. It was impossible to comprehend the scale. More than two miles away, we heard no sound except endless sirens calling to one another from every direction. Where we stood transfixed it did not rain. There was no wind. There was only the tornado.

“Look at all that paper swirling around,” someone said.

“Those are garage doors,” another answered.

We watched as the horrendous vision scraped its way northward, the finger of God plowing a furrow along South Road out in Mack. We watched as it withered and lifted and twisted into nothingness against a pallid sky, waving it seemed in farewell at last as it vanished. We stared at each other, silent, unable to find any words.

Gradually, we realized that all the lights were out. There was no power in the offices. The publisher sent me around the corner to a hardware store to buy all the candles they had in stock. It was going to be a long night.

At this point, for the benefit of readers younger than I, it is necessary to explain a few details. The cash register at the hardware store was mechanical. It did not require electricity, much less Wi-Fi, to operate. The editorial offices were stocked with manual typewriters. The telephones were landlines, on a separate network, and functioned even when the power was out. Everyone had a battery-powered radio.

Anyone with the ability to write a coherent sentence became a reporter. I was sent out, still wearing my printshop uniform, in the divotted Econoline, to gather eye-witness reports. I found a small crowd at the Western Hills Country Club who had been herded into a downstairs bar while the sirens howled. They queued up for every available telephone to check in with their families. I found people in shock, wandering through piles of rubble that had been their homes, clutching any random possessions they recovered. I saw ambulances backed up in a line, waiting for utility poles and power lines to be moved. I saw people wrapped in blankets, standing in the middle of nothing left, sobbing on each other’s shoulders.

There were people who swore they saw two funnel clouds and people who claimed there were four, twisting like snakes in the sky. There were people who confessed to being so transfixed by the surreal wonder of the twister that they stood paralyzed as it swooped down on their houses.

And, in the curious way the universe laughs at we mere humans, I found humor.

There was the guy who, in a dispute with his insurance company, was photographing damage to his roof when the warning sirens erupted. He saw the funnel approaching and dove into his basement. When he emerged, his roof was gone, and so was the rest of his house, but he bragged that he had the photos to press his prior claim.

I talked to one of the rescue workers who told me about a kid, maybe 15 or 16 years old, who approached him and begged him to hide a bottle of vodka. The kid didn’t want his mother to know he had the bottle hidden in his bedroom – the bedroom that was now nothing more than a debris field.

Meanwhile, at the University of Chicago, Dr. Theodore Fujita drafted a questionnaire to be sent to almost every newspaper, every radio station, every television station in the country. Dr. Fujita asked a lot of questions about the duration and intensity of the 148 confirmed tornadoes reported that day. He and Allen Pearson of the National Severe Storms Forecast Center hoped to refine the tornado classification system they had created just three years previously. Someone at the Press filled out the questionnaire and sent it back.

A year later, having graduated from the university and transferred to the newsroom, I found a largish cardboard tube lying amid the usual pile of news releases and complaint letters that constituted our daily mail. On opening the tube – it was addressed to no one in particular – I found a map of the eastern United States titled “Superoutbreak Tornadoes of April 3-4, 1974.” Dr. Fujita, compiling all those questionnaires, had mapped and labeled every one of those 148 tornadoes.

In the center of the map, there was my tornado, the only tornado I have seen with my own eyes, officially designated as an F5 monster.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

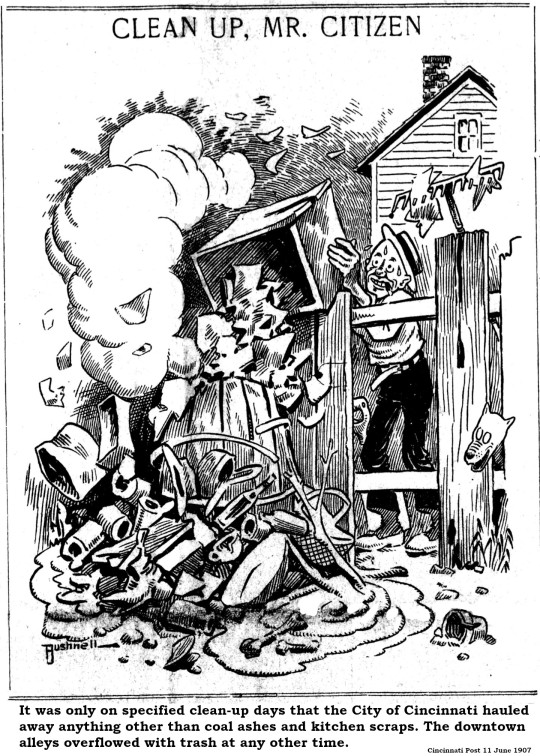

Cincinnati’s Clean-Up Campaigns Remind Us That Our Ancestors Lived Like Pigs

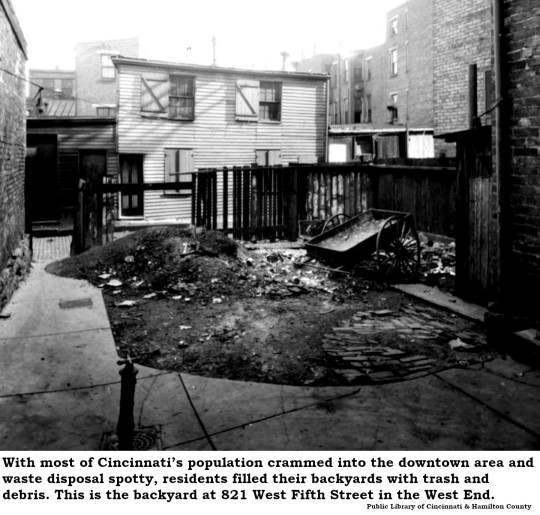

If you had family in Cincinnati a century ago, I have bad news for you: They wallowed in garbage. It wasn’t entirely Grandma’s and Grandpa’s fault. The City of Cincinnati took a long time to figure out trash collection. Back around 1910, for example, the city sanitation wagons picked up only two kinds of refuse – ashes and garbage. Ashes were the remnants of the fuel burned in stoves and furnaces. Garbage had a very specific definition, as set forth in the 1909 Building Code:

“The word ‘garbage’ shall be held to include all refuse of animal, fish or vegetable matter which has been used for food for man, and all refuse animal, fish or vegetable matter which was intended to be so used.”

The average household also accumulated stacks of paper and piles of rags – no paper towels back then! – and the Rag Man hauled this stuff away for sale to the local paper mills.

That left several miscellaneous categories of rubbish or trash that no one had any interest in: broken bottles and crockery, old wooden barrels, scrap lumber, anything metallic like tin cans or buttons, bricks and stones, tree branches, and so on. All of this junk just piled up in the backyard or basement or both.

In the early 1900s, a few progressive organizations tried to organize city-wide clean-up campaigns to eliminate all the junk from residential backyards. In addition to aesthetic concerns, there was a strong financial incentive for hauling away this trash. Cincinnati’s fire-insurance underwriters applauded [Cincinnati Enquirer 5 January 1906] a report demonstrating that a 1905 clean-up effort had resulted in 200 fewer fires than were recorded in the previous year. Insurers actually lowered rates for the downtown businesses after clean-up campaigns and Captain Jack Conway of the Cincinnati Salvage Corps requested regular campaigns to remove trash:

“He advocates the ‘clean up’ campaign be continued with unabated vigor until all rubbish is removed from cellars, old waste from under benches, &c., which are the most prolific source of fires.”

The Cincinnati Woman’s Club led the charge in 1907 and talked Mayor Edward J. Dempsey into supporting a thorough spring cleaning for the downtown area. The mayor asked residents to haul all that backyard and basement debris out to the curb on one fine day in June. Problem was, all of the city’s street-cleaning wagons were already committed to hauling ashes and garbage that day. It was only when Mayor Dempsey talked the very reluctant Street Repair Department into donating their 40 wagons that the campaign was made possible. Even a fleet that large was not enough to handle the accumulated detritus. According to the Cincinnati Post [10 June 1907]:

“As the Cincinnati Street-cleaning Department has not enough teams and men to clean up all that district in one day, the Woman’s Club, for which the city is making the experiment, has appealed to all firms and corporations and all individuals having wagons and teams to assist in the work Wednesday, June 12. That is the day upon which all the hauling will be done.”

Annual “house cleaning days” gathered enough support to continue for several years, but the Woman’s Club had other initiatives to support and leadership for the campaign transferred to the Chamber of Commerce, which super-sized the operation. For the 1914 campaign, the Chamber set aside several weeks in the spring for the clean-up, followed by a city-wide inspection. The Chamber paid for 100,000 lapel buttons promoting the effort and printed 250,000 circulars informing residents how to participate.

The Chamber even coughed up a $25 prize for the best “Clean Up and Paint Up” song. The winning lyrics were composed by Dr. Stephen E. Slocum, professor of applied mathematics at the University of Cincinnati, whose words were set to music by Walter H. Aiken, director of music for the Cincinnati Public Schools. The local schools stepped up to promote the clean-up campaign, not only by distributing brochures and flyers, but by planting gardens in most of the city’s schoolyards.

In addition to aesthetics and fire safety, the 1914 campaign encouraged sanitary measures to stop the spread of flies. At a time when the majority of vehicles on Cincinnati’s roads were horse-drawn, manure piled up all through the city, supporting an infestation of flies unimaginable today.

After weeks of encouraging residents to tidy up their properties, the Chamber coordinated a city-wide inspection to document compliance and results. According to the annual report, some citizens were none to happy about having their domestic habits evaluated:

“There were some people with a misconception of the meaning of personal liberty who refused to allow inspection of their premises and some preferred not to aid in a general ‘clean up’ for fear it would be only spasmodic and not result in permanent good.”

Despite scattered opposition, the Chamber bragged that the 1914 campaign resulted in a $600,000 reduction in fire loss, from $1.3 million in 1913 to less than $800,000 in 1914. Nearly 8,000 wagonloads of trash were hauled out of residential areas. That success led to an even more ambitious campaign plan for 1915. In fact, the Chamber may have become a victim of its own success. A report suggests that few of the campaign’s ambitious goals were achieved in 1915, although the results were still impressive.

At the conclusion of the 1915 clean-up period, the Chamber coordinated city-wide inspections. More than 42,000 premises received a visit, with 30,000 earning a clean certification. The remaining 12,000 properties appalled the inspectors, who identified nearly 35,000 defects ranging from unsecured garbage and ash cans to obstructed fire escapes to overflowing privy vaults and unsanitary toilets to open manure piles.

More than 300 buildings were found in such deplorable condition that they were ordered razed. The city located nearly 1,300 illegally maintained backyard outhouses and ordered them replaced with flush toilets that could still be located in the backyard if preferred!

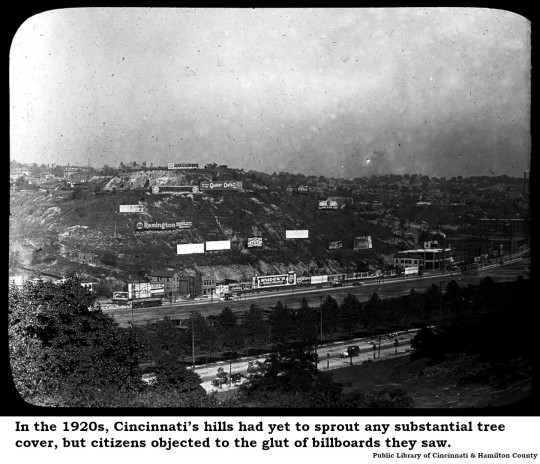

Thanks to the generosity of the Mabley & Carew Company, clean-up participants planted more than 84,000 trees on Cincinnati’s barren hillsides.

While congratulating itself on a job well done, the Chamber dinged the city administration for outdated and ineffective procedures for removing garbage and other refuse:

“The city has made no step forward for the disposal of its waste, except garbage, since its first log cabin was built in January 1789. As the population has increased, the dumps have grown in size and become nearer to built up residence sections. This has resulted in strenuous complaints from time to time, and the elimination of those dumps against which pressure has become too strong to be resisted by city officials.”

Alas, with the city administration still under the thumb of the Boss Cox machine, city officials could resist any level of public pressure without even breaking a sweat.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

For More That Twenty Years, Billy Guthrie Fought The Law, But The Law Won

Billy Guthrie built a career flouting the legal authorities. He spent almost as much time in Cincinnati’s courtrooms as he did in his notorious saloons. He died, apparently unrepentant, having created a Cincinnati legend that stretched from the Gay Nineties into Prohibition.

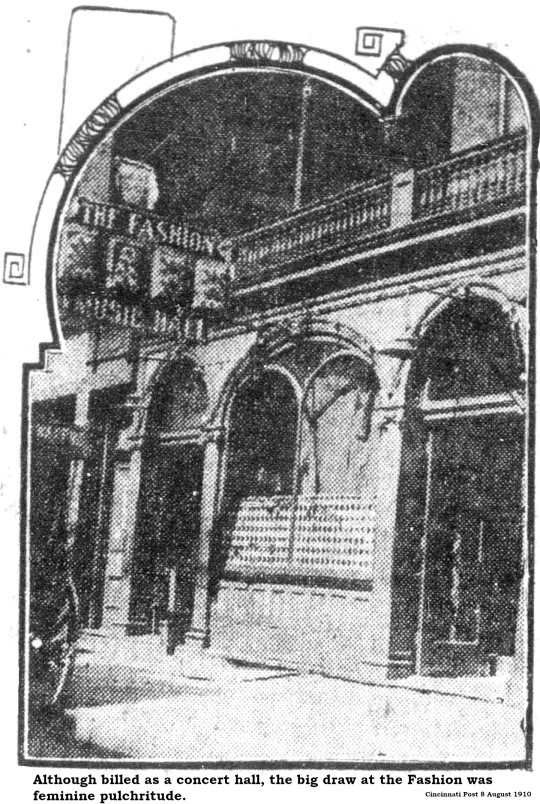

If you had asked William W. Guthrie, he would have claimed to be a put-upon proprietor of some humble cultural establishments. If you asked Cincinnati’s progressive reformers, Guthrie was the devil incarnate, spewing vice and degradation from the noxious hellholes he referred to as “concert halls.”

For the first decade of the Twentieth Century, Guthrie operated a disreputable resort named The Fashion on Opera Place, just off Vine Street below Sixth Street. Allegedly, the building had once housed a synagogue. The Cincinnati Post [16 March 1910] captured the atmosphere and allure of The Fashion:

“The patrons of The Fashion are neither lovers of good music nor dancing, and they do not go there for either. Between the acts at The Fashion the women performers can be found drinking with the men at the tables in the loges. Their value to the house is purely in the drinks that men buy for them. They prefer bottle beer and mixed drinks. They sit at the tables in their short stage skirts and can be seen from the outside.”

While the crusading Cincinnati Post sputtered in indignation, Guthrie operated without any interference from the authorities so long as the city was controlled by George “Boss” Cox and his minions. Guthrie owned a city “concert hall” license and waved it in the face of anyone who suggested that his dive was anything but that.

In 1910, a reform-minded Republican, Henry Hunt, was elected county prosecutor despite Boss Cox’s obstruction. He launched a campaign against gambling and vice and was so successful that he was later elected mayor and even prompted Boss Cox to issue a public statement that he was retiring from politics.

While Hunt may have rattled The Boss, Billy Guthrie shrugged off Hunt’s efforts to shutter The Fashion. Hunt saw to it that Guthrie’s concert hall license was not renewed, but the saloonist quickly adapted. According to the Cincinnati Post [14 August 1911]:

“Guthrie’s place was formerly licensed as a concert hall. The license was taken away from him and now he is running the same kind of hall without a license. Formerly, Guthrie employed singers, who, when they did not sing, ‘sat in’ and promoted the sale of drinks. When his license was revoked Guthrie abolished the singers and installed an orchestra. Presto! It ceased to be a concert hall, but became merely a saloon with a music box.”

This “saloon with a music box” continued to employ women of negotiable affection who greeted their admirers and encouraged them to buy abundant drinks. While they no longer sang on The Fashion’s stage, it was reported that they hummed along with the popular tunes performed by the “orchestra,” which was usually a piano accompanying a violin.

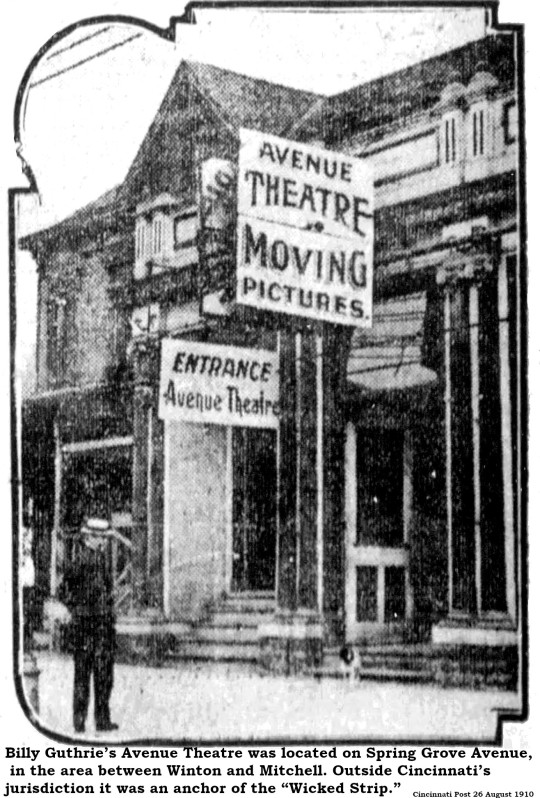

While Guthrie jousted with the Cincinnati reformers, he took out a sort of insurance policy by opening another saloon outside the city limits, almost directly across from the entrance to Chester Park. Chester Park itself usually attracted a mainstream clientele with a variety of rides, a huge lake for swimming and boating and theaters staging opera and musical comedy. On occasion, Chester Park brought in a very different sort of customer when it hosted prize fights that were illegal in Cincinnati. The whole area around Winton Road and Spring Grove Avenue had not yet been annexed to the city and was colonized by saloons eager to escape Cincinnati’s more restrictive regulations. The Post christened that neighborhood “The Wicked Strip” and Billy Guthrie fit right in.

In 1910, motion pictures were still a very new medium, inspiring some legislative reactions we find amusing today. For example, as noted, prize fighting was prohibited within the Cincinnati city limits. Apparently, the city administration saw no difference between real pugilists pounding each other in the ring and cinematic boxers pounding each other on the silver screen. So, indeed, Cincinnati prohibited motion pictures showing prize fights.

Billy Guthrie was happy to provide a venue for a film capturing the highlights of what was then billed as “The Fight of the Century” between the first African American heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and the former heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries. The Post [26 August 1910] went apoplectic:

“The whole country rose in opposition to the Jeffries-Johnson fight pictures. Mayor Schwab prohibited them. The pictures were driven out of Covington. Banished everywhere in the neighborhood, they found a wide-armed welcome in the Wicked Strip that knows no law and doesn’t care. The pictures were placed on exhibition in Guthrie’s Avenue Theater – Guthrie being the man whose disreputable Fashion Concert Hall on Opera-pl. has been driven off the street by the force of public sentiment.”

Billy Guthrie found that the wages of sin provided quite a comfortable income. It’s a toss-up whether his name appears more often in the criminal court logs or the real estate columns of the newspapers. Back then, with banks regularly going insolvent with no deposit insurance, land was where people parked their cash. Guthrie bought or sold a parcel or two almost every week.

Curiously, it seems that Guthrie, an otherwise savvy businessman, was a poor judge of character. On at least two occasions, it was reported that he posted bail for a defendant (presumably one of his customers) who stiffed him by failing to appear in court. In each case, Guthrie forfeited more than a thousand dollars.

What the local constabulary could not do, national legislation achieved. The dawn of Prohibition marked the end of Billy Guthrie’s lucrative saloons. He made a half-hearted attempt to keep a dive bar going in the West End but was busted by federal agents and settled into retirement. Guthrie turned the Avenue Theater over to his son, who operated it as a more-or-less law-abiding café. The location, at the corner of Mitchell and Spring Grove, is now occupied by a car wash.

Billie Guthrie died, aged 66, in 1929 from a heart condition and is buried just down the road from the “Wicked Strip” in Spring Grove Cemetery.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birdless Ballot Boosters Marked The End Of Boss Cox’s Cincinnati Political Machine

For better or worse, mostly worse, no history of Cincinnati can be written without significant attention to the reign of George Barnsdale Cox, the man known as Boss Cox. For forty years, from the 1880s into the 1920s, Cox and his minions ran Cincinnati like a private fiefdom. It is remarkable that the Cox Machine was brought low by a bunch of birds.

Cox ruled from his position as chairman of the Hamilton County Republican Party and during his reign no one got elected in Hamilton County without the Boss’s approval. To keep the votes rolling in for his chosen politicians, Cox dispensed county funds where loyalty could be bought. Cox ignored the city's parks where squirrels didn't vote. Cox bled the schools because teachers didn't vote and, as one of Cox's lieutenants was quoted, "most of them are women, anyway."

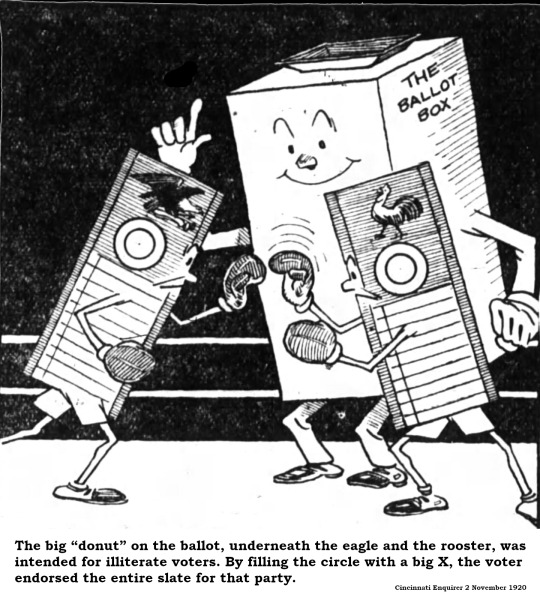

Cox’s favorite voters were dependable machine constituents who voted a straight Republican ticket. It mattered not whether they knew who they were voting for. In fact, it was probably preferable that they didn’t care who they elected. Through bribes and favors, Cox owned the illiterate vote in Cincinnati. Cox’s ward heelers had one simple task – to vote a straight Republican ticket. To do so, voters didn’t need to read. They need only remember to vote the eagle.

Voting was a lot more complicated 100 years ago than it is today. In 1920, each party had its own ballot, and each ballot had a symbol or logo on the top. There were no Elephants or Donkeys. Republican ballots showed an eagle at the top, while Democratic ballots were emblazoned with a rooster. The Socialists employed a hand holding a torch. Prohibitionists used a rose.

Under the party symbol, each ballot showed a big circle. If a voter wanted to vote a straight party ticket, all they had to do was mark a big, bold X through that circle and drop the ballot in the appropriate box. That big circle was extremely convenient for illiterate voters and Cincinnati had a lot of them. These voters cared not a whit about any candidate. All they knew was that a beer or a fifty-cent piece awaited once a poll monitor signaled to the ward boss that the voter had marked the correct ballot. For illiterate voters, the non-partisan judicial ballot was indecipherable and fist fights broke out at various polls when party hacks offered to “help” illiterate voters translate the judicial ballots.

One hundred years ago, in January 1924, a group of Cincinnati reformers organized the Birdless Ballot League to eliminate party ballots. It proved to be the death knell for the Boss Cox machine. Although the idea had been circulated before, it was lawyer Henry Bentley who made the birdless ballot his personal crusade. Bentley’s proposal was simple: Eliminate the party emblems from the ballot and force voters to individually select candidates by name. If adopted, the birdless ballot would effectively disenfranchise anyone who couldn’t read and thereby remove a big tool from the Cox Machine’s toolbox.

By the time Bentley got involved, the Cox Machine was a sputtering hulk of its former magnificence. Cox himself had died in 1916. His lieutenants, grown fat and happy with the spoils of graft and corruption, found interests outside the grind of municipal politics. Mike Mullen, whose influence extended well beyond his homebase in the Fifth Ward, died in 1921. August "Garry" Herrmann had all but retired from politics to oversee the Cincinnati Reds. Only Rudolph “Rud” Hynicka was still in control, and he had long since relocated to New York City, where he managed a string of burlesque theaters.

It was left to local party stalwarts to gin up the opposition to Bentley’s proposal. Gilbert Bettman, a Republican of the Cox camp, fumed during a speech to the Women’s City Club [Cincinnati Post 18 April 1924]:

“The birdless ballot, historically unsound, illogical and wholly negative, judged by this single standard, would not tend to bring better or more capable men into the public service. In-so-far as it would have any effect, it would weaken the structure of parties, creating a political hodge-podge, bloc or minority government.”

Bettman’s speeches that year were reminders that the old Cox Machine had chewed up reformers before and expected to easily dispense with Bentley and his ilk. And yet, despite its invulnerable reputation, the Cox gang had endured occasional, if temporary, revolts almost from the moment it seized control of the city. The Machine had learned to bend a little when necessary but to snap back once the reformers relaxed. In 1924, they complacently ignored a groundswell that had been gaining strength over the past decade. Consequently, the Machine underestimated the opposition.

Simultaneous with Bentley’s call for birdless ballots, the Cincinnatus League, another group of reformers, including future mayors Murray Seasongood and Russell Wilson, agitated for a charter establishing a city manager form of government. Seasongood and his allies recognized that the birdless ballot was step in the right direction, but the ultimate goal needed to be a complete reform of city government. At the urging of the Cincinnati Post, which had built its reputation as the anti-Cox newspaper in town, the charter supporters and the ballot reformers joined forces.

It is all but forgotten today, but the Charterite reformers succeeded largely because of Cincinnati’s Socialists, particularly Herbert Bigelow, pastor of the non-denominational People’s Church. That congregation provided many of the volunteers essential to the reform movement. It was they who circulated petitions, got out the vote and lobbied for change at public meetings.

The Cox/Hynicka syndicate tried to confuse voters by promoting their own charter issues on the 1924 ballot. If either of those measures passed, city council would have been reorganized but no substantial changes would have taken place.

As it developed, Cincinnati’s voters were inspired by the idea of a ballot without birds. On November 4, 1924, the Charterite referendum received more than 88,000 votes, with only 39,000 votes in opposition. The new charter streamlined city council to just nine city-wide seats instead of an unwieldy legislative body with a representative from all 32 wards. The new council selected a weak, mostly ceremonial, mayor to preside at council, and hired a city manager to conduct most city business. Overnight, Cincinnati’s reputation as one of the worst-governed cities in America was transformed and the city became known as one of the best and most efficiently run municipalities in the country.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

While The Wright Brothers Toiled, Cincinnati’s Flying Machine Fanatics Tanked

Ohio license plates proclaim the Buckeye State as the “Birthplace of Aviation.” Had fate turned out differently, that sobriquet could have applied to Cincinnati. Over the years, several Cincinnati tinkerers tried unsuccessfully to loft a heavier-than-air craft.

As far back as 1834, a Cincinnati resident named Albert Masson constructed a vehicle he described as an “aerial steam boat.” According to a writer signed only as “J.L.” (possibly John Laughlin, secretary of the Ohio Mechanics Institute), in the Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Gazette newspaper [3 July 1834]:

“The boat is about ten feet long; the ribs being covered in silk, in order to render it very light. – The engine, of two horse power, is placed in the middle, and turns four vertical shafts projecting over the bow and stern, into each of which are fixed 4 spiral silken wings, which are made to revolve with a sufficient velocity to cause the vessel to rise.”

According to “J.L.”, the entire apparatus weighed about 60 pounds and Mr. Masson intended to fly the contraption on July 4 – the very next day. At the time of publication, the aerial steam boat was on display “on Race street, nearly opposite the old Lath Factory, below Third street.”

Mr. Masson did not go airborne on Independence Day and, in August, his flying machine was on earthbound display at the Commercial Exchange. The Daily Cincinnati Republican reported, “There is nothing of the balloon principle connected to the apparatus.” and that it was “a beautiful and ingenious piece of mechanism.”

As beautiful and ingenious as it was, the aerial steam boat appears not to have ever achieved flight and all references to it cease after 1834. Tom D. Crouch, curator of aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum and a former chief of education for the Ohio Historical Society, has researched Masson’s invention extensively, publishing his findings in the Journal of the American Aviation Historical Society [Spring 1974]. According to Mr. Crouch:

“If we are to believe the articles published in the Cincinnati papers, and there seems no reason to doubt them, then Albert Masson was the first person in history to produce a heavier-than-air craft, powered by a prime mover, that was actually intended to fly.”

Although Mr. Masson vanished into the mists of history, between 1840 and 1902, Cincinnati newspapers printed at least 404 articles with the phrase "flying machine." Some of these reports featured home-grown Cincinnati aeronauts.

Cincinnatians awoke on 27 Oct 1889 to learn that a local man, one Ferdinand W. Randall of Main Street, had built a flying machine. In fact, this inventor had quite a surprise for the scientific community. As related by the Cincinnati Enquirer:

"He not only has a flying machine, but claims to have discovered perpetual motion."

The newspaper goes on to relate that Mr. Randall's inventions have "something lacking." That "something" was, of course, money.

Mr. Randall, approximately 35 years in age at the time, was a photographer. His workshop was on Main Street. His flying machine was described as a "peculiar-looking sail-boat" suspended by a wire from the ceiling. It was basically a boat hull, with a screw propeller and rudder at the rear, four wheels and an "intricate mass of fans and wire cables." Two black wings, wider and longer than the boat, were suspended above. According to the Enquirer,

"The beauty about Mr. Randall's machine is that it can move on land, in the water, or in the air."

Randall told the Enquirer he had read every book available on aeronautics and is "undoubtedly well posted on the subject." Well posted or not, Mr. Randall joined the roster of inventors whose aircraft never left the ground.

Curiously, just 18 months later, the Cincinnati newspapers found yet another potential flying machine. This one was created by a mechanic named John Randall, of 322 Vine Street, who had built a flying machine remarkably similar to the airship unveiled by Ferdinand Randall - a boat 18 feet long with a mass of wires attached.

Similar flying machines and identical names? Not a coincidence. The Randalls were brothers who had operated Randall Brothers Outdoor Photographers for several years. The younger brother struck out on his own and got work as a mechanic and electrician.

Ferdinand apparently gave the flying machine to his brother because the machine described in 1891 is almost identical to the 1889 machine with one exception. John replaced the two black wings atop Ferdinand’s machine with a large canvas balloon. In other words, it was no longer a heavier-than-air machine, but only a mechanically propelled lighter-than-air craft. Not the same thing at all.

Had another local man succeeded, Kennedy Heights or Norwood might be known as the birthplace of manned flight. Alas, Charles M. Mallory did not succeed. In fact, he failed again and again and again. Sometimes spectacularly.

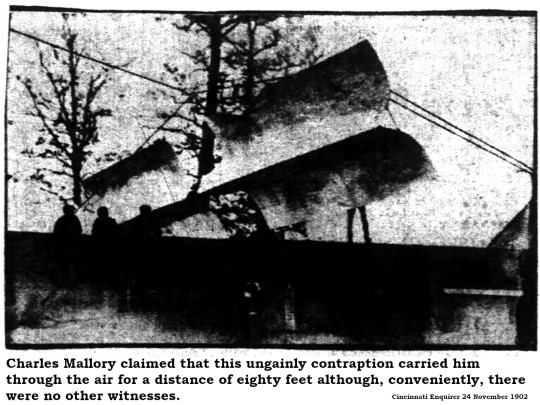

In August 1902, the 40-year-old Mallory, a pattern maker with the Bullock Electric Manufacturing Company, announced that he would launch a new flying machine into the air from a vacant lot in Kennedy Heights. With a large crowd observing, he rolled out a contraption described by the Cincinnati Enquirer:

"It was as if two monster Mexican hats had been inverted and joined together by a framework that had wings on either side. At one end was a rudder."

With a squad of volunteers tugging away, Mallory's monstrosity "scudded along the scaffolding for a few feet and then toppled over on one side."

Mallory tried again in November 1902 at the grounds of the old Norwood Inn. This time, instead of human volunteers, Colonel James E. Fennessy, a local theatrical impresario, volunteered to tow the contraption aloft with his automobile. Col. Fennessy got bored waiting for Mallory to prepare his flying machine and drove home. Fennessy sent a chauffeur out to Norwood with another automobile, but he, too, lost patience.

When Mallory was finally ready, no automobiles could be found, despite messengers and phone calls. While waiting in vain for another runabout, Mallory agreed to pose for photographs in his machine, hoisted to the top of a derrick. The wind caught the contraption and dashed it to the ground from a height of 25 feet. Although Mallory was unhurt, his flying machine was in tatters.

Mallory attempted another flight in August 1903 off Lookout Mountain in Tennessee but, again, the wind dashed his contraction to flinders. Interestingly, Mallory told the Cincinnati Post at that time that he had achieved an 80-foot flight in Norwood, a feat suspiciously unseen by any other witness.

Four months later, the Wright boys grabbed the prize.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wendell P. Dabney’s Lifelong Efforts To Preserve The History Of Black Cincinnati

Anyone who studies Cincinnati’s history owes a debt of gratitude to Wendell Phillips Dabney. Nearly one hundred years ago, Dabney published one of the most important books ever written about the Queen City.

“Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens” appeared in 1926 and is still essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the rich history of our city. At a time when Black people faced unrelenting persecution and segregation, Dabney compiled an exhaustive and almost encyclopedic record of African Americans in Cincinnati. His book highlights the accomplishments and points of pride of a thriving community derided and stereotyped by the majority power structure.

On page after page, Dabney documented hundreds of Black citizens raising respectable families, owning solid and profitable businesses and residing in homes better than those occupied by many of Cincinnati’s white residents. He demonstrated that Black professionals thrived in Cincinnati despite legal and societal prejudice, and he showcased charitable institutions created, constructed and funded by Black generosity, including an orphanage, social clubs, churches, schools and homes for the elderly. Almost a century later, Dabney’s book is the only available source for information about Black Cincinnatians before the civil rights era.

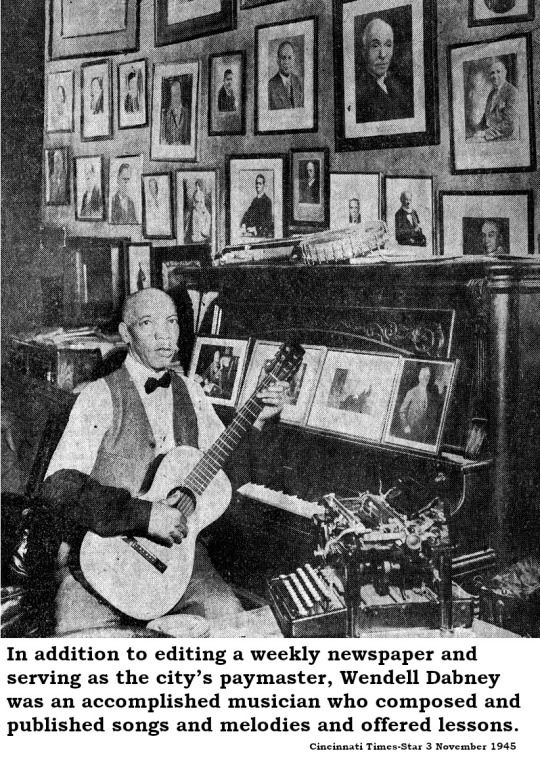

Dabney promoted his personal political agenda through his own newspapers. Dabney’s were Cincinnati’s first newspapers aimed at an African American audience. He published the inaugural issue of The Ohio Enterprise in 1902, changed the name of the paper in 1907 to The Union, and single-handedly published that paper until his death in 1952.

A big fan of Dabney’s was Alfred Segal, the Cincinnati Post writer known by his byline as “Cincinnatus.” Segal often shared items from Dabney’s columns with his own readers. According to Segal [27 August 1950], The Union was less a news medium and more of a lectern for the irrepressible Dabney:

“It hasn’t been really a newspaper in the sense of handing out the latest news; it has been more of a reflection of Wendell P. Dabney himself and how he thinks and feels about everything. It is a paper for colored citizens but many white ones read it just to get the flash of Mr. Dabney’s mordant humor.”

While it is true that his newspaper published many wry examples of the editor’s humor, Dabney was an untiring opponent of segregation. For much of Dabney’s life, integration was a controversial position among Blacks as well as whites. Many in the Black community believed that segregated schools, hospitals and other institutions provided protective environments for African Americans. Dabney would have none of it. He wrote [30 December 1922]:

“This drawing of the color line in public institutions and establishment of ‘jim crowism’ is largely done by Negroes themselves, either through ignorance or desire for money. Civic rights legally belong to all citizens. Segregation of people is not necessary to fit them for civic duties. We have here and in other cities, colored people in nearly every profession and department of public life. ‘The Caste System’ has never done anything but degrade.”

Dabney’s health began to fail as he reached his eightieth birthday in 1945 and made noises that he would soon give up publishing The Union, but soldiered on. Soon after achieving that eight-decade milestone, Dabney hopped up from his sickbed and demonstrated that he was still capable of the old buck and wing as well as some clog dances. A celebration of Dabney’s 84th birthday in 1949 attracted more than 350 guests. The Union maintained its weekly publishing schedule until Dabney died in 1952. In an obituary of sorts, Al Segal of the Post [4 June 1952] observed:

“He never made any money out of being a publisher; it was pay-off enough for him to hear people laughing with him.”

Wendell Dabney was born in Richmond, Virginia just after the South surrendered in defeat to end the Civil War. His parents, John M. Dabney and Elizabeth Foster Dabney, had been enslaved but built a successful catering business after achieving freedom.

Dabney graduated high school in Richmond and began appearing on stage, sometimes with tap-dance legend Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, a childhood companion. He later attended Oberlin College in Ohio and performed in that school’s orchestra.

After teaching for a couple of years in Virginia, Dabney relocated to Cincinnati to manage property inherited by his mother, including the Dumas House, the only Cincinnati hotel that accepted Black guests.

Intending to stay in Cincinnati only long enough to stabilize his mother’s properties, Dabney was introduced to a young widow with two children, Nellie Foster Jackson. They married in 1897 and Dabney credited Nellie with his later accomplishments. In Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens, he wrote about her:

“The loyalty and courage of his wife through twenty-five years of storm and stress engendered that domestic harmony and inspiration to which whatever success he may have attained is indebted.”

Dabney integrated himself into Cincinnati’s social and political fabric and excelled at several endeavors. He was an accomplished musician who composed and published songs and melodies and offered lessons through Cincinnati’s Wurlitzer emporium. He published a biography of his friend, Maggie L. Walker, the first African American woman to charter a bank and the first African American woman to serve as a bank president. Dabney was the first president of the Cincinnati chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and was, for many years, a stalwart in the local Republican organization. With the rise of the progressive Charter Committee in the 1920s, Dabney switched his allegiance to that organization.

For 26 years, he served as paymaster for the City of Cincinnati. Dabney noted dryly that, although he had been entrusted with dispersing a total of $80 million over the course of his career, his personal salary was only $150 a month. Such was the nature of political appointments under George Barnsdale “Boss” Cox. As founder and leader of the Douglass League of Negro Republicans, Dabney was an essential factor in getting out the Black vote. The Cox machine rewarded key influencers like Dabney with spots at City Hall.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overwhelmed By Advertising? The Battle For Cincinnati Consumers Has Raged For More Than A Century

Depending on the source, it is estimated that each American is confronted by 6,000 to 10,000 advertising messages every single day. That immersive media onslaught swelled as we started carrying little video screens around wherever we go, but invasive and obnoxious marketing has bothered Cincinnatians for much more than a century.

For example, on 20 July 1871, a correspondent for the Cincinnati Times related an enjoyable voyage he had undertaken down the Ohio River. After praising the service of his riverboat’s staff, the remarkable scenery along the river, the picturesque little town he floated by, the writer registered one complaint, about a cliff near the town of Hanging Rock:

“High up on the face of this wall of white sandstone, hundreds of feet beyond the reach of a scaling ladder, I noticed a patent medicine advertisement. It was penciled there by a man let down with ropes from above, and the letters are large enough to be read from the deck of a steamer two miles distant. I was sorry to see this defacement. It is bad enough that all the fences throughout the land should be made to lie for patent medicines without debasing the hill-sides with such marking. I suppose that when the ‘chemical affinity necessary to be the motor of some immense flying machine’ shall be discovered, some enterprising patent medicine man will be plastering the face of the moon with some of his ‘wonderful remedies.’”

If only the poor man knew what lay ahead! Even in the 1870s, almost every vertical surface in Cincinnati was slathered with posters, placards and bills advertising shows at the local theaters, patent medicines and political candidates. Cincinnati was the center of the bill-posting world. For one thing, Cincinnati was among the top printing cities of the United States, with the mighty Strobridge Lithographing Company dominating the poster industry.

Also, Billboard magazine was headquartered here in Cincinnati. What we now think of as a music magazine, Billboard was founded in Cincinnati as a trade publication for men who posted “bills” on walls. From its first issue in 1894, Billboard covered the entertainment industry, such as circuses, fairs and burlesque shows, and also created a mail service for travelling entertainers. Initially it covered the advertising and bill-posting trade and was known as Billboard Advertising.

Far from inspiring civic pride, advertising rankled Cincinnati residents as they witnessed visual pollution encrusting the region’s hillsides. Leading the opposition was the Municipal Art Society – a sort of ad-hoc predecessor to today’s Urban Design Review Board. The opening shot was fired 24 August 1896 when the Enquirer reported:

“A matter that will undoubtedly be of interest to the business men is the fact that war has been declared by the Cincinnati Municipal Art Society against advertising signs on fences along the car routes and drives of the city. The art society maintains that these signs mar the beauty of the city, especially in the case of landscape scenes on the hills and in the suburbs, and that they are offensive to the public taste.”

The Society was persistent. It took five years but the Cincinnati Post reported [24 November 1901] that the Baldwin Piano Company had demolished 200 feet of billboards erected on company property along Gilbert Avenue. The Post described this as the “first result” of the Society’s campaign.

The Municipal Art Society was soon joined by some strange bedfellows. The Cincinnati Business Men’s Club, among whose members were certainly a number of advertisers who employed billboards to disseminate their messages, created its own Municipal Art Committee to lobby for restrictions on outdoor advertising. On 1 June 1907, the committee circulated a postcard illustrated with a photo of signage clogging the view from the Grand Central Depot, with the sarcastic caption, “A Nice Welcome To Cincinnati.”

As early as 1895, the city chased the Fountain saloon’s advertising off Fountain Square, but appears not to have drafted a comprehensive law about outdoor advertising until 1909 when, as part of a broader safety ordinance, the city adopted limitations on the size of billboards, their placement near thoroughfares and the materials to be used in their construction.

While the city pondered how to encourage commerce while maintaining attractive views, the entire billboard industry was gaining momentum through a Cincinnati entrepreneur named Philip Morton. Before Morton, “bill boards” were basically fences on which bill posters slapped printed advertisements glued up with a flour-water paste. Morton took outdoor advertising to a new level, according to Jay Gilbert, who has researched his influence on marketing [Cincinnati Magazine September 2016]:

“By 1898 he’d become the Steve Jobs of roadside blight. Doing business as Ph. Morton, Phil was an early pioneer of putting ads into free-standing frames called ‘bill-boards’ and plunking them down everywhere. Eventually every railroad route and motorway in America had its view ruined by a Ph. Morton billboard.”

Even the powerhouse Morton found himself in the city’s crosshairs. Parks Superintendent John W. Rodgers, according to the Enquirer [20 September 1907], exasperated by Morton’s billboards blocking the view of Inwood Park, erupted.

“Park Superintendent Rodgers yesterday tore down over 12,000 feet of big billboards that stretched along for a distance south of Hollister street, facing Vine street, in front of Inwood Park. The billboards were 12 feet high, about 1,000 feet long and contained the advertisements of leading firms of the city, and were illuminated at night with electric lights. They had been at that place for years.”

All of those billboards were leased by Philip Morton who, as coincidence would have it, dropped off a check to pay the lease while workmen were busily engaged demolishing his thousand feet of signage. This was the Boss Cox era in Cincinnati where the right hand was very often ignorant of the left hand’s activity. And so it was, while the Park Superintendent was demolishing billboards on Vine Street, the Board of Public Service pondered a lease for billboards along Gilbert Avenue. That’s right – the same Gilbert Avenue divested of billboards just six years earlier.

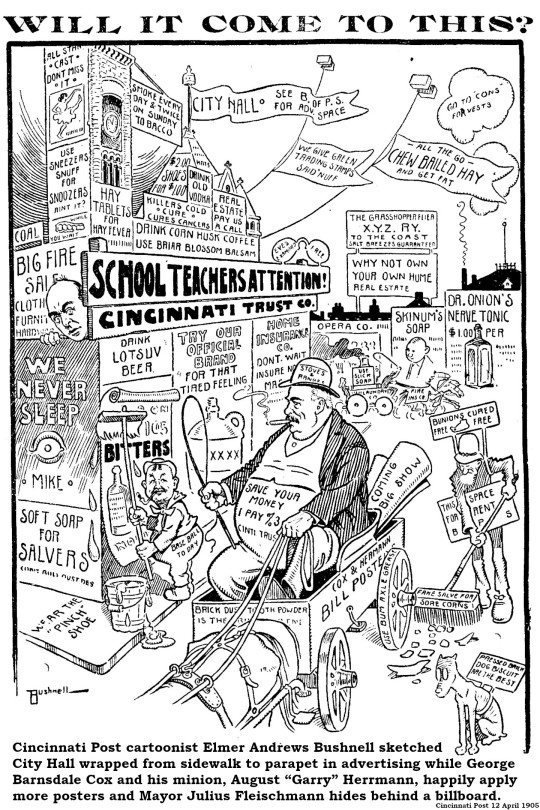

A common theme of cartoon artists at that time was the eventual coverage of all available exterior surfaces with advertising signs and slogans. In response, Cincinnati Post cartoonist Elmer Andrews Bushnell sketched City Hall wrapped from sidewalk to parapet in advertising while George Barnsdale Cox and his minion, August “Garry” Herrmann, happily apply more posters and Mayor Julius Fleischmann hides behind a billboard.

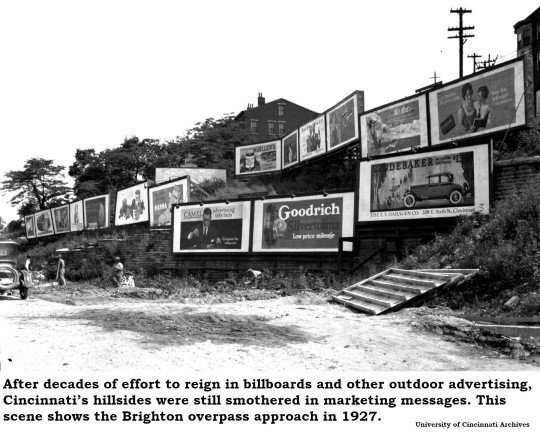

The battle raged for decades. Photographs from 1927 show dozens of billboards crowding the hillside over the Brighton overpass to Central Parkway and the Enquirer [24 March 1929] begged for relief because billboards and other unsightly structures had a negative effect on property values:

“What of the gaudy billboard that intrudes itself into a residential district, the sign which girds the tree or telephone pole, the roadside ‘shack’ which is made more ugly with bizarre advertisements? Do they affect values?”

A century later, we hardly notice billboards anymore. We’re too busy texting while we drive.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Grandparents Canoodled In Passionate Petting Parties Along Cincinnati’s Country Lanes

Around one hundred years ago, a new theme was introduced to the long-established images decorating paper Valentines. While hearts and flowers, little birds and rosy-cheeked children still predominated, the Valentines of 1924 often featured something new – the motor car.

While innocent enough when surrounded by lace and flowers, the motor car had already begun to arouse the suspicions of Cincinnati parents. The old fogies suspected that automobiles represented much more than transportation to the kids. Those jalopies might be nefarious vehicles of illicit lust!

Well, the old folks were correct. Young people throughout Cincinnati were tootling out to the nearest country byway and canoodling in extended make-out sessions known as “petting parties.” The Cincinnati Business Women’s Club got together to grumble about “rolled stockings, petting parties and abbreviated bathing suits as they affect the adolescent girl.” The Cincinnati Post [4 April 1924] quoted Alma Hillhouse, educational director of Cincinnati’s Social Hygiene Society:

“The child gets its instinct for petting from the mother. When a babe she is held on the mother’s knee and fondled. When she grows up she seeks satisfaction in petting parties. It is the standards in the home that count. The daughter of the wise mother will come through petting parties unscathed; the uncontrolled girl comes to grief.”

You will notice that neither Dad nor any adolescent males are assigned any sort of accountability in this matter. Some things never change.

While the Business Women’s Club debated, the Indian Hill Rangers, organized, according to the Enquirer [3 June 1924], to “trail horse thieves, cattle rustlers and pillagers of hen roosts,” were confronted with a new threat to village security.

“Indian Hill Rangers are after motorists who have been using the shady lanes and sylvan retreats of that pretty hilltop east of the city and the adjoining countryside for ‘petting’ and gin parties.”

One evening, the Rangers encountered a limousine parked on Drake Road, its windows curtained with newspapers. While not disturbing the occupants, the Rangers copied the license number and mailed a letter to the owner, a woman living in Avondale. They never saw that particular vehicle again.

While Indian Hill was dealing with limousines, the real action was out in the Western Hills among the still-rural expanses of Delhi and Green townships. According to the Enquirer [14 October 1924]:

“For months residents have complained that autoists have forsaken the dim-lighted parlor and its sofa for the moonlit roadside and the cushioned seats of the automobile. Even private driveways and lawns have been converted into trysting bowers by these seekers for seclusion, who have openly defied property owners to the extent of drawing weapons on them, it has been stated.”

Alfred Bennett of Green Township blamed the recent crackdown on Cincinnati’s “red light” district in the West End for the flight of depraved and lustful characters into the hinterlands. He told the Enquirer [25 October 1924} that illicit smooching was just the beginning:

“‘Much of the objectionable practices in country districts is not entirely “petting parties,”’ Mr. Bennett stated, ‘but gross immoralities that shock the residents.’”

So gross were these alleged immoralities that they inspired a flurry of ecumenism between the Catholic and Protestant congregations of Bridgetown, with the Rev. Paul Schmidt of the Evangelical Protestant Church standing shoulder to shoulder with Father William Spickerman of Saint Aloysius Catholic Church in demanding more patrols by the county sheriff. The clergymen offered to recruit volunteer deputies from among their flocks. In neighboring Delhi Township, Justice of the Peace M.J. Roebling lumped petting party participants among nuisances such as “bootleggers, bandits and hold-up men.”

The Delhi magistrate wasn’t that far off, it seems. Widespread outrage about romantic parkers, combined with very public statements by the county sheriff that he did not have the budget nor the manpower to patrol the county’s lovers’ lanes, suggested a business opportunity for the local footpads. The Enquirer [28 July 1924] reported that outlaws impersonating county deputies were robbing couples caught on deserted roads:

“Two more hold-ups were committed late last night by a gang of five bandits who are blamed for a total of 17 known hold-ups and who, it is said, have collected hundreds of dollars by swooping down on ‘petting parties’ on county highways and extorting money under the guise of deputy officers.”

Many of the township roads favored by passionate petters led to roadhouses established outside city limits to avoid enforcement of Prohibition laws. Cincinnati’s Juvenile Protective Association claimed that the immoral environment promoted by these roadhouses spilled over into steamy backseats. And, of course, the media were blamed as well. A new film, “Daughters of Today,” written by a one-time Cincinnati newspaper reporter named Lucien Hubbard and starring Zazu Pitts, opened that year. According to the Enquirer [29 September 1924]:

“It is an ultra jazz production, with petting parties, cocktail shakers and syncopation distributed throughout the length of its half dozen or more reels.”

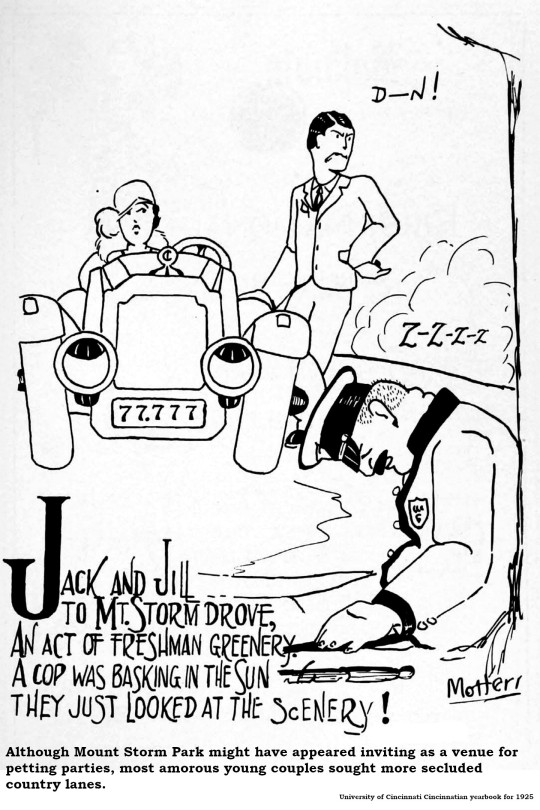

By October 1924, the scandal had reached such an extremity that the Cincinnati Automobile Club passed a strongly worded resolution condemning “petting parties” as a safety hazard and demanding more patrols by the sheriff. So vehement was the public condemnation of “petting parties” that the Enquirer actually editorialized in favor of passionate parking because a total crackdown would force hormonal youngsters into petting while driving and thereby endanger pedestrians!

Although it is unlikely the Automobile Club’s wrath had any effect, by the next year the Cincinnati Post [20 July 1925] reported that petting parties, the bane of 1924, seemed to be passé in 1925. Two deputy sheriffs spent a long and fruitless summer evening looking for lovers along the East Miami River in Anderson Township:

“In two hours, we found only one spooner. That was on Broadwell-rd, where a boy and his sweetie were spooning in the moonlight to the strains of a victrola on the back seat of their machine.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not Exactly Vampires, Many Cincinnatians Indulged A Craving For Fresh Blood

A curious article appeared in the Cincinnati Medical Advance for November 1875, alerting local doctors that a number of their patients had adopted a peculiar diet.

“It may not be generally known that, like New York, Cincinnati has its blood drinkers – consumptives and others who daily visit the slaughterhouses to obtain the invigorating draught of ruddy life-elixir, fresh from the veins of beeves. Lawrence’s slaughter house, opposite the Oliver Street Police Station, has its daily visitants who drink blood; and the slaughter houses of the Loewensteins on John Street, a few squares away have perhaps half a dozen visitants of the same class.”

Yes, you read that correctly. Back when Cincinnati butchers operated abattoirs all over the fringes of the downtown area, they provided free blood to anyone who stopped by and asked for a glass. It is no surprise that a macabre practice such as this would attract Cincinnati’s legendary chronicler of the bizarre, Lafcadio Hearn, and indeed it did. Hearn published his report of a visit to the Loewensteins in the 26 July 1876 edition of the Cincinnati Commercial.

“Between the hours of 2 and 4 o’clock almost any afternoon, the curious visitor may observe many handsomely dressed ladies and others enter the cleanly, well-kept establishment in question, and waiting, glass in hand, for a draught of crimson elixir, yet warm from the throat of some healthy bullock. Just as soon as the neck of the animal is severed by one rapid slash of the ‘Schochet’s’ long blade, glass after glass is held to the spouting veins and quickly handed to the invalids, who quaff the red cream with evident signs of pleasure, and depart their several ways.”

Hearn’s reference to a Schochet identifies the Lowenstein slaughter house as following kosher practices. The Schochet is a ritual slaughterer, certified by the local rabbi to practice his craft. That the Loewenteins followed kosher practice was an important distinction for Hearn, who had previously described his displeasure while observing gentile butchery.

“Many who can drink the blood of animals slaughtered according to the Hebrew fashion, can not stomach that of bullocks felled with the ax. The blood of the latter is black and thick and lifeless; that of the former bright, ruddy and clear as new wine.”

While most of Cincinnati’s blood drinkers were satisfied with a single tumbler of fresh blood, Hearn relates the experience of a “short, well-built but pallid-looking” man who downed glass after glass of blood and strolled away, apparently satiated. When he next reappeared, ten days later, he was asked if all that blood had made him queasy or nauseous. He replied that he could drink gallons of blood at a time but confessed that his latest sanguinary binge had caused him to go blind for a week.

“Yet, having recovered his vision, he believed that he could see better than ever.”

Hearn interviewed several doctors who insisted that drinking fresh beef blood could never produce blindness, temporary or otherwise. In fact, most of Hearn’s medical informants told him they discouraged their patients from imbibing in slaughter-house blood at all.

“I have always warned my consumptive patients against drinking blood,” one doctor told Hearn. “The latter practice is both morally and physically detrimental.”

Despite medical objections, Hearn gulped a tall glass of blood himself and provided detailed tasting notes.

“Fancy the richest cream, warm, with a tart sweetness, and the healthy strength of the pure wine ‘that gladdeneth the heart of man!’ It was a draught simply delicious, sweeter than any concoction of the chemist, the confectioner, the winemaker – it was the very elixir of life itself.”

A decade later, according to an article in the Cincinnati Times [12 February 1885] Cincinnatians were still lining up for bloody drinks. The Times reporter asked an emaciated man how his unusual dietary supplement tasted.

“Like salted milk,” he replied. “And some put salt in the blood, but I do not feel that it makes it more palatable.”

The Times recorded a visit to the slaughter house by a man of eighty years in age, who had walked three miles to get a glass of blood. He claimed that he had been a near invalid when a friend suggested a regular glass of the stuff. The old man boasted he now walked six miles a day and felt stronger than he had when he was fifty.

The proprietor informed the Times that his slaughter house always kept a supply of dark blue glasses on hand for new patients. The tinted glass disguised the color of the drink they were offered and allowed them to get used to the taste. After a few visits, the very demeanor of the blood drinkers changed, often radically.

“I know of one person whom it did change in that way. At first she could not bear even the sight of blood, and was weak, sickly, delicate and timid, but finally she got all over this and liked to see a steer killed, especially if the beast was game.”

One bloody quaff certainly had a dramatic effect on Lafcadio Hearn, who sailed off into a rhapsodic endorsement of this strange elixir, tempered by a premonition that a taste of blood might result in a decidedly unwanted transformation of character.

“No other earthly draught can rival such crimson cream, and its strength spreads through the veins with the very rapidity of wine. Perhaps this knowledge originated that terrible expression, ‘drunk with blood.’ That the first draught will create a desire for a second; that a second may create an actual blood-thirstiness in the literal sense of the word; that such a thirst might lead to the worst consequence in a coarse and brutal nature, we are rather inclined to believe is not only possible, but probable.”

The Schochet informed Hearn that he himself, following Mosaic law, had never tasted blood. Hearn, after pondering the effects of a single warm glass, advised the “healthy and vigorous” to follow the instructions of Moses and abstain. Hearn feared that blood-drinking, while beneficial to the sickly and infirm, would drive healthy individuals onto a bestial quest for even more vile excesses.

“Perhaps it was through occasional indulgence in a draught of human blood (before men’s veins were poisoned with tobacco and bad liquor) that provoked the monstrous cruelty of certain Augustinian Emperors.”

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Special Delivery! Here Are 17 Curious Facts About The Cincinnati Post Office

On The Barrelhead

The Cincinnati Post Office was established in 1794 and received soon after its first mail delivery, consisting of sixteen letters, two newspapers and a snuff box. All mail then was “collect on delivery” or COD – recipients paid the postage. Postage for a simple letter was 25 cents. The postmaster displayed all mail on top of a barrel at his house. Anyone wanting to collect mail paid the postmaster.

Returned To Sender

Cincinnati’s first postmaster was an attorney and Revolutionary War veteran named Abner Dunn, who ran the local post office out of his house at the corner of Second and Butler streets. Postmaster Dunn died in 1795 after only a year in office and was buried in the backyard of his house, which was also the backyard of the post office. The site is now a parking lot near Sawyer Point Park.

Everybody Knew Your Business

From 1799 up until Cincinnati adopted free home delivery in the late 1860s, the Post Office regularly published a list of all letters awaiting collection, so everybody in town knew when you had mail. If you ignored the published list for three months, your mail was sent to the dead letter office. The lists were extensive, occupying, in small type, as much as half a page in the Cincinnati Commercial or Gazette.

Keep It Under Your Hat

Cincinnati’s fifth postmaster was an eccentric Methodist minister named William Burke, who served a very long term from 1814 to 1841. Possessed of a deep, guttural voice attributed to his lifelong addiction to chewing tobacco, Burke is remembered for personally delivering mail around town while making social calls. He kept the items to be delivered in his hat. It is said that “Father Burke,” as he was known, also delivered wise counsel to his patrons along with the mail.

Penny For Your Thoughts

During the 1840s, Cincinnati experimented with home delivery, but charged for the service. Two “penny postmen” divided the downtown area, with Joseph Haskell taking the route north of Fourth Street, and Hiram Frazer delivering south of Fourth. Recipients, in addition to the standard postage, coughed up a penny for each letter delivered to their front door.

Inaugural Air Mail?

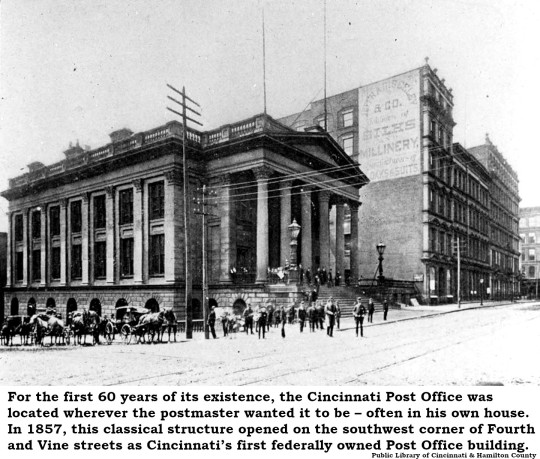

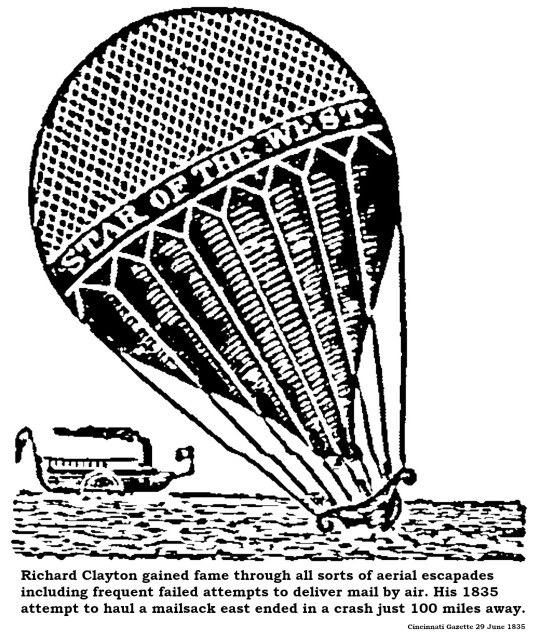

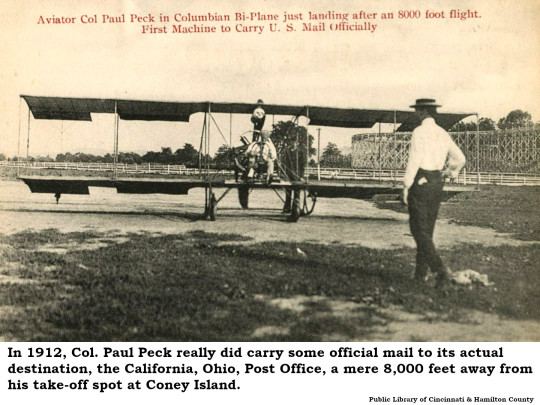

The first mail at least partially delivered by air left Cincinnati on Independence Day 1835. Obviously, no airplane was involved. The pilot was the “Prince of Aeronauts,” Richard Clayton, and the vehicle was his renowned balloon, the Star of the West. Clayton ascended from an amphitheater constructed in the middle of Court Street between Race and Elm with, among other cargo, a satchel of mail intended for eastern cities. He crashed 100 miles away in Pike County and had the post office in Waverly, Ohio, send the letters the rest of the way. A trial involving an airplane in 1912 was really a gimmick in which mailbags picked up at Coney Island were dropped at the California Post Office, just 8,000 feet away.

What The Dickens?

By 1825, stagecoaches had replaced pack horses as the primary vehicle for transporting mail throughout the Ohio Valley and nascent Midwest. In addition to letters and newspapers, mail coaches carried passengers and were often the most reliable means of travel available outside the East Coast. When Charles Dickens visited Cincinnati in 1842, he arrived by mail coach.

Postmaster Is The ‘Last Man’

On 6 October 1855, Cincinnati Postmaster John L. Vattier sat down to a most unusual dinner. His table was set for seven, but every place setting, excepting one, was empty. Vattier was the last of seven young Cincinnatian men who survived the 1832 cholera epidemic, bought a pricey bottle of wine, and pledged to meet each year for dinner, saving the bottle for the last of them to survive. On that evening, following the funeral of his last colleague, Vattier dined alone and drank the bottle in memory of his friends.

Postal Currency – What A Riot!

As the United States struggled to finance the Civil War, an unintended consequence was a shortage of coins. The Post Office stepped up to alleviate the shortage by issuing postal currency in the form of “shinplaster” paper bills in fractions of a dollar. Public demand was so great in Cincinnati that a riot broke out at the distribution center on 5 November 1862. Although no one was seriously injured, federal troops called in to disburse the 2,000 rioters drew swords and attached bayonets to their rifles until calm was restored.

Shillito Becomes A Worthy Investment

Cincinnati merchants, notably John Shillito of department store fame, devised creative ways to issue change when coins were scarce. During the coin-scarce Civil War, Shillito noted that his customers often used postage stamps as currency. Shillito crafted special circular cases to contain one-cent, three-cent or five-cent stamps and used them just like coins in providing change to customers. Today, an 1862 Shillito “encased postage” coin can bring as much as $1,250 at auction.

Hier wird Deutsch gesprochen