#disability theory

Text

(Edit: just to be clear I don't mean to emphasize this girl with the tattoo as the primary perpetrator if this stuff. Idk her story, it's in kind of bad taste but there's more to this than a tattoo)

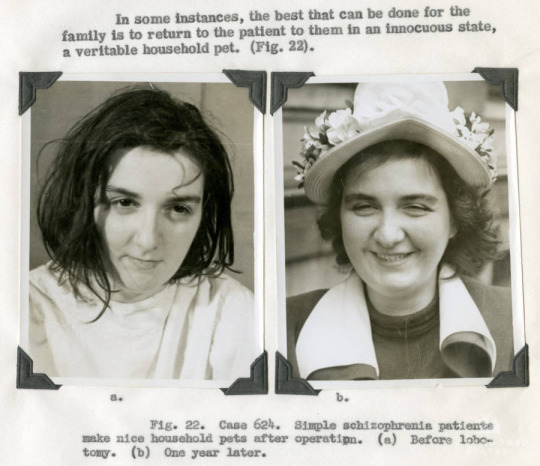

I saw this great video discussing a critique of "lobotomycore"/"lobotomy chic" and the erasure of the racist history of lobotomies.

I can't add further on the subject of race, but as a person with schizotypal I did connect it with this image

(Source, though I have not verified it by sifting through the archive)

"Lobotomy chic" and the humor surrounding it is used so often by people who I've seen have zero empathy for schizophrenic people. For disables people generally.

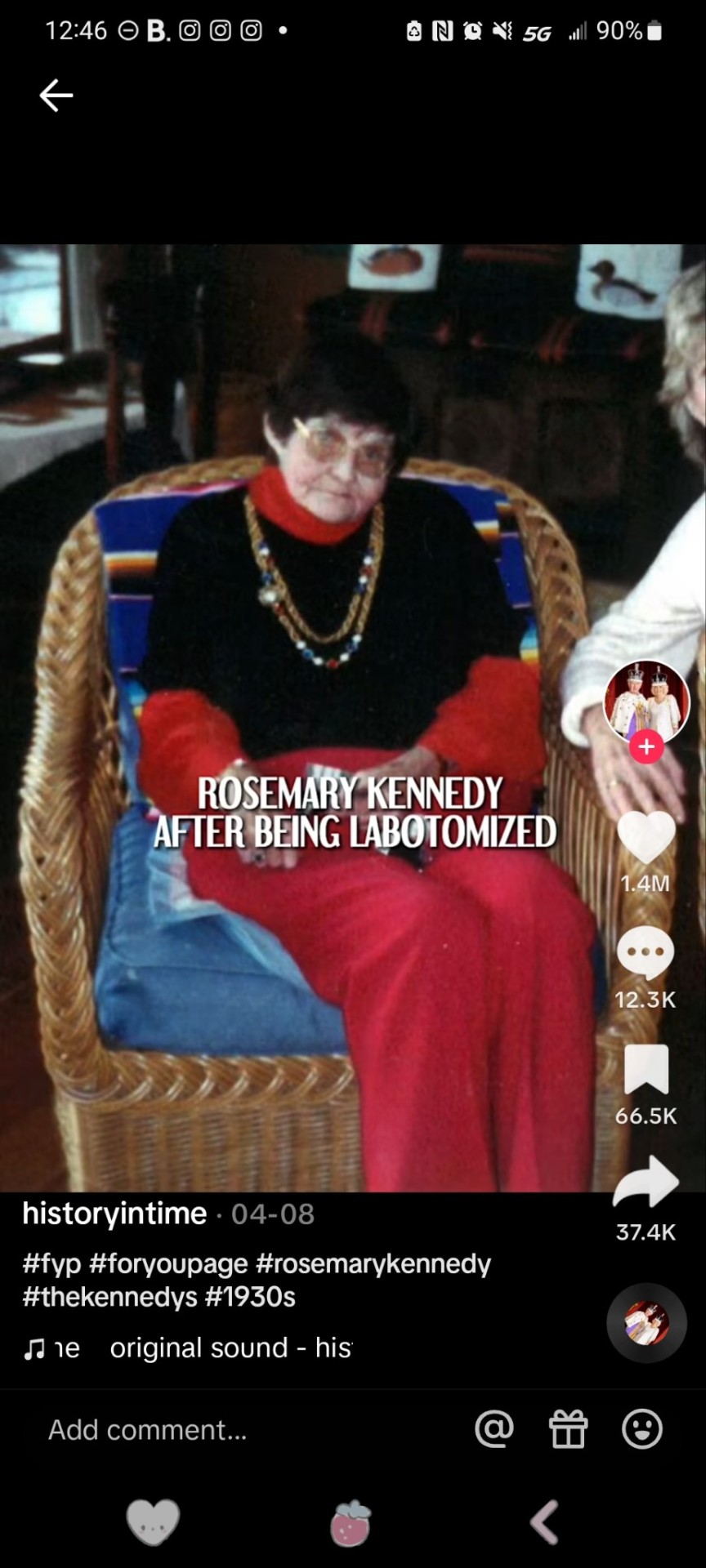

Even just looking at how they treat an actual lobotomy victim, Rosemary Kennedy, even when she's that archetypical 40s white woman. Her disability is erased.

Here's a popular tiktok about her. No context, just images of her younger self and her older self. Simply "she was normal, glamorous, and then she became strange, disabled." Oftentimes, her intellectual disability is treated more as a conspiracy theory than a fact of her not receiving enough oxygen at birth. People are happy to relate to her as a ~poorly behaved woman~, but not as an intellectually disabled one.

It just reminds me how this has become a sort of coquetteish phrase and a universal joke that erases everything except the low support needs disabled white woman's experience. The idea that for your eccentricities, you'd be at risk. That you might be the only one at risk, so there's no need for solidarity with the intellectually disabled, the schizophrenic and psychotic, anyone with profound or uncomfortable disabilities. Times ten thousand if those disabled people are black. And god forbid they are disabled, black, AND homeless.

#disability theory#schizophrenia#actually schizophrenic#schizospectrum#disability rights#disability justice#long post#psychiatric abuse tw#racial abuse tw#ableism tw#medical abuse tw

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, would you be able to give a brief description/explanation of cyborg theory in disability? I tried looking it up but didn’t find anything

absolutely! been struggling a bit with cognition so i’m just gonna paste the relevant section from my essay on disability & technology from about a year ago + the full citations of pieces i reference. hope this helps - feel free to send me a follow up ask if there’s anything else you’re looking for or with your thoughts, & folks are welcome to dm me for the full essay if you want!

One key concept employed by disability studies scholars to explore the relationship between humans and technology is that of the cyborg. Originally developed by Donna Harraway in the 1980s, the cyborg is a figure which “[blurs] the boundaries between human and animal, machine and organism, physical and non-physical” (Kafer, 2013, p.103) and in doing so allows for nuanced discussions of technology beyond the common dual responses of uncritical praise and unlimited fear. Though Harraway’s initial theorization positioned “disability as the site of spectacular technological fixing” (Kafer, 2013, p.112), feminist disability studies scholars have expanded the concept to more fully reflect disabled people’s experiences.

At their best, cyborg subjectivities prompt us to recognize—rather than dismiss—“the inequitable ways in which many people come to disability” (Hamraie and Fritsch, 2019, pp.19-20). War, poverty, pollution, and other consequences of colonisation and exploitation are major causes of impairment among marginalised communities (Meekosha, 2011; Erevelles, 2011), making concepts such as disability culture and pride difficult or undesirable for many people. Not only are the bodies of workers in the Global South disabled by the production of “assistive technology,” as discussed previously, the bodies of marginalised people, especially poor women of colour, are disabled by medical testing (Hans, 2006). While Erevelles questions the value of cyborg subjectivities in the face of these harrowing realities (2011), Kafer argues that their power lies in this very tension (2013). The cyborg, she writes, “refuses easy celebrations of human/technology connections” (Kafer, 2013, p.118) and rather encourages us to confront our complicity in the structures of oppression we seek to resist.

Erevelles, N. 2011. Disability and difference in global contexts: enabling a transformative body politic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hamraie, A. and Fritsch, K. 2019. Crip technoscience manifesto. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience. 5(1), pp.1-34.

Hans, A. 2006. Gender, technology and disability in the South. Development. 49(4), pp.123-127.

Kafer, A. 2013. Feminist, queer, crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Meekosha, H. 2011. Decolonising disability: thinking and acting globally. Disability & Society. 26(6), pp.667-682.

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

(cw: spoilers for the beginning of Tears of the Kingdom, discussion of disability and impairment)

In TOTK, I see Link as disabled.

Sure, his prosthesis is a transplanted arm from another person, able to do all kinds of basically magical powers, but... it's still not his arm.

He's still going to get itchy along the reattachment scar.

There will be dysphoria associated with seeing someone else's hand attached to his body.

The pain, the trauma, of losing something like that will never go away, most likely. Link is a survivor, sure. A goofball, definitely. Unflappably assured in his own ability to overcome difficulty. But I imagine his dreams are still unsettled, and every once in a while, when he comes into contact with the Gloom, he'll be reminded of just what it felt like to have his body wracked with pain from his encounter with Ganondorf. How the life was sapped from him. How hopeless he felt after being unable to catch Zelda as she fell.

He's never going to be seen as fully human, because he's not, not anymore. There's always going to be a part of him that's always going to be different from other Hylians, and that's not easily overcome, either.

It's a cool arm. But he's going to have days where he's going to look down and see something that the dark corners of his mind won't recognize completely, and might tell him subconsciously that it doesn't belong.

Link is impaired, but also disabled, if only in how he encounters the world differently from everyone else. There will be people who exclude him because of his difference, thus disabling him. There will be times when others won't be able to relate to him because of his trauma. There will be times when his near-muteness will render him unable to convey his experiences. He bears the weight of the world on his shoulders--this much we know from Zelda's diaries-- and in a way, his very role as the Princess's champion disables him from ever living a normal, average life.

Mentally, physically, and socially, his trauma has rendered him unable to access a normal life.

This may just be me reading into it too much. I'm disabled too. But I find so much of how Link has had to compensate for his life in the game relevant to my own disability struggles.

I think Link is disabled, and I think this makes his story that much richer.

#disabilty#legend of zelda#totk#tears of the kingdom#disability theory#blog#theory#legend of zelda tears of the kingdom#link#zelda#tloz

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like tumblr's analysis of the social model of disability would be more coherent if the impairment–disability divide was more broadly understood so I'm going to do my best to briefly summarise that!

before I launch into this, I just want to make a few caveats:

the social model is not my preferred model of disability. I am way more into the political-relational model

I don't necessarily subscribe to the impairment–disability divide in full, and I have my own critiques of it

BUT nothing pains me more than seeing people critique a model I dislike whilst arguing that the model is saying something that it isn't actually saying. so here we go: the impairment–disability divide!

once upon a time, a feminist called Judith Butler (building on the work of Simone de Beauvoir) wrote a book claiming that "sex" and "gender" were separate categories, where sex is natural and gender is social (I, an intersex person, largely disagree with these definitions but that's a different story). she argued that, while the category of gender is usually based on the category of sex, separating the two categories from each other allows for more nuanced cultural analysis

in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a group of disability scholars in the UK read this work and thought that it could be roughly reworked in such a way that it could also apply to disability. HENCE the impairment–disability divide. to them, "impairment" refers to the natural state of having a disability (e.g. not being able to see/hear, not being able to walk, experiencing hallucinations, etc). "disability" refers to the social meanings given to those impairments (e.g. being Deaf)

this is the context that the social model was born into in 1983 by Mike Oliver. he never claimed that disability is 100% social in the way many people would conceive of "disability". he would not agree with claims that disabilities and impairments are completely socially constructed. instead, he was arguing that "disability" is only a coherent category because of various features of social and built environments. he thought that people wouldn't have as much of a need to identify as disabled if they were treated better by society

TLDR: the impairment–disability system breaks disability into two parts (the natural part and the social part). the social model of disability argues that having various impairments would be easier if society was more accessible and less discriminatory

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

"disability theory"

image: the international symbol for disability, which is a white glyph of a wheelchair user on a blue square, next to a question mark

added to disability page

#disability#disability theory#communication symbol#communication image#aac symbol#aac image#aac emoji#custom emoji#concepts

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something something yes it matters that the character with such a powerful queer storyline got killed off as a culmination of his character arc but I also want to bring up that this was our main legibly disabled character and I think that matters. Disability is a part of this plot and this death. There's something about disability in texts where as part of the narrative disability must be dealt with - kill or cure - and as Izzy became legibly disabled he had to be cured or killed. I'm not saying I agree with this theory just that it exists. I want to talk about this more

#our flag means death#ofmd s2#ofmd#ofmd s2 spoilers#ofmd spoilers#izzy hands#israel hands#ofmd s2e8#disability#disability theory

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

there is something that feels so insidious to me in the way certain loved ones will wish me well. sometimes it feels like there is an obvious implication that the presumed goal not just of my treatment but of my life is the absolute minimization of symptoms, which is probably fine on the surface. symptoms feel bad, right? so why shouldn't you do everything you can to avoid them and keep all the "normal" function you can?

however, i think there is some implicit ableism that has snuck its way into that framing and is doing a lot of the lifting, it turns out. first, it implies a narrative of the "illness warrior"—life with an illness is often depicted as a struggle against the disease, and to lose your life (in terminal cases, as with cancer) is to "lose your fight." even in non-terminal chronic illness, i believe that framing is still common, at least from those who are not sick around the chronic illness patient, though there are some sick people who identify with that language. for some people, it can be empowering, giving them the strength to be a warrior and get up and fight, but for me, it feels like it puts the severity of my illness in my hands. to be very ill is to lose ground and fight badly. to some extent this is true, in that there are certain factors in my life i can change that will positively or negatively impact my health, but more broadly, this idea feels brutally unfair. if i am in pain because of a weather-triggered migraine, am i to simply get up and move my entire life in time with the seasons to avoid storms? it feels terribly unfair and lays responsibility for my symptoms existing or disabling me at my feet.

secondly, the high valuation of symptom-free—or as close as possible—existence feels to me to be assimilationist with capitalist values of labor. there has been a lot written about intersections and cross-applications between queer and disability theory. comp het translates to similar ideas of comp-abledness, which i think is a large part of what's going on here. i would extend this further to use queer assimilation as a framework for disabled assimilation. in the way that traditional values will lend more legitimacy to a queer couple who are monogamous, who follow established norms of marriage, cohabitation, etc, there is legitimacy to be had for disabled people who support themselves without or with minimal benefits, who are gainfully employed, who "do not let their disability stop them." yet disabled labor is undervalued especially in the laws that allow for disabled workers to be paid under minimum wages and the bleak landscape of legal accommodations being insufficient, difficult to enforce, at an employer's discretion, or all of the above leaving disabled workers in the hands of petty tyrants. disabled people are encouraged to keep working but not protected or treated fairly when they do. i believe this extends beyond work as well—the minimization of symptoms allows for a disabled person to keep their own household and do their own chores without support, and is therefore the valued goal, however unrealistic or difficult. in what i believe is a critically under-read essay, sunny taylor outlines "the right not to work," defending the value of a disabled life which does not fit norms of productivity in the workforce or the home. so i wonder: if there are supports available, why restrict myself from them? if there is a life that does not involve recovery to the norm but rather prioritizes quality of life, isn't that worthwhile? if there is a life without recovery to the norm but rather recovery self-directed towards the activities and functions a patient wants for themself, would that be so bad, even if they are still sick, even if they still need help?

i hope for such a life.

#disability theory#disability#chronic illness#sorry you can tell i have a theory degree from reading this post i'll try to hide it better in the future

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Temp Pinned (I will eventually make an official one):

Hello! I'm Kathel, you can call me Kath or Muse if you'd like instead. I'm just an autistic trans dude on the internet, hyperfixations will vary. I am a recent University of Washington graduate with a bachelor's in Medical Anthropology and Global Health. In the future I am planning on going for my graduate degree within the field of medical anthropologist. I'm hoping to either be a professor in the field and/or an ethnographer. My passion involves how different medical systems function across the globe, but where I'd specifically like to work on is how the American Healthcare/Medical system fails to aid disabled people and the lack of focus on the intersections within disability (ie meaning how different marginalizations intersect with disability). I'm still figuring out how I'd like to start a career in that area while taking a break from college.

As well as that, I also have interest in different media fandoms such as Baldur's Gate 3, Red Dwarf, Sam and Max, Fallout, Re-animator and others you'll see me posting about.

This page is a mishmash of social justice, anthropology, fandom, and silly meme posts and reblogs.

#bg3#red dwarf#sam and max#freepalastine🇵🇸#free palestine#blm#land back#actuallyautistic#disability theory#transgender#transmasc#2slgbtqia+#lgbtq+

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In a world where pain represents the ultimate measure of quality of life, all disabled people risk to have their existence described as wrongful life, because disability and suffering are thought synonomous. Disabled lives are routinely described as lives not worth living, lives undeserving of human dignity."

— Tobin Siebers, "In the Name of Pain: Pain and the Stigma of Disability" lecture (~18:03 minute mark)

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think you should just say “disabled” instead of “elderly or disabled” bc you’re not talking about the actual age of a person. you’re talking about their ability level. but people just don’t want to admit they see disabled as a dirty word

#actually disabled#disability justice#cripplepunk#disability#disabled bodies#disability theory#physically disabled#spoonie#chronic illness#chronically ill#mobility issues

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am on a mission to reduce my cognitive dissonance

Making lists of dozens of philosophers and philosophies to study is a productive use of my spring manic energy right? I'm just not sure all of them will have very profound things to say about *that* part. Why do philosophers treat disabled people like shit

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you are going to take life threatening risks, whether it be drugs or alchohol, skipping out on masks, whatever, you need to understand that the risk isn't going from healthy and alive to suddenly dead. You need to prepare to be disabled. My dad has been sober for 30 years. He didn't die. But he is permanently disabled. He has incontinence issues, memory problems, lingering addiction, etc. along with diabetes and his other preexisting conditions. Dying early is often a very, very slow process.

I just see people so often shrug and say "I don't care if I die young", but you can tell they haven't considered what happens when they don't die. Or when they DO die, but not in a pretty way.

#when it comes to masks youre also risking giving this fate to others#im not perfect at all about masks but that is the truth of it#death tw#addiction tw#disability theory

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Loneliness is unpleasant for everyone, but it takes on especial horror for disabled people who live so much of our lives in isolation. Unless you have experienced it yourself, it's hard to understand fully the ache of watching others live their lives while it feels as though you are merely aging. It's not the fear of missing out; it's just missing out. Day after day, season after season, year after year of not being healthy enough, not being strong enough, not being smart enough, not being attractive enough, not being happy enough, not being enough of anything to be enough.

So when you finally secure access to something for the first time—maybe a concert, a graduate program, a job, a relationship, a surgery—and you realize that you are still feeling all alone, and that no one seems to care... well, devastating doesn't begin to cover it."

— J. Logan Smilges, Crip Negativity (University of Minnesota Press, 2023), pp. 7-8.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pool metaphor for disability is too simple. Disability is complex and we should treat it that way.

I saw this argument presented by a great Autistic about why Autism is a disability (which I agree with, I also think Autistics are disabled!!), but I disagreed with the way it was explained, and some of the reasoning. This person is great and I don't even know if they made up the metaphor, and I'm not going to mention them by name because I think that's not good to do?

The metaphor went like this: people are like swimmers in a pool. Some people swim differently, and they are fine and they get a thumbs up. Some people need a lifejacket because they can't swim. Only one needs accomodation. The ones who need accomodation are disabled.

I have some major gripes with this metaphor.

What is swimming differently Vs not swimming?

Whether or not someone can swim differently or if they can't swim at all ultimately doesn't matter in a pool where both groups are unable to participate. Sure, their are fundamental differences, but neither of them can function in this weird fucked up pool, so they're both disabled. That's what actually defines disability.

In real life we aren't given life jackets or thumbs ups and then the playing field is magically leveled. There are people who require assistance in our society that are not disabled because their needs are met automatically. The label of "needing support" only exists because that need isn't always filled.

We can argue about whether we can swim or not all we like, but the fact is, there are only man made differences between being different and inherently needing support. What counts as knowing how to swim is decided by people.

We all inherently need support. But disabled people's needs are treated as case by case individual needs, while non disabled or universal needs are built into the fibre of our society.

We need to stop acting like disability is something that can be identified with a magical birthmark that stays the same no matter what. It's a complex identity deeply related to our society, much like being queer, and how a man topping another man was not queer in ancient Greece.

Is there objective suffering that comes with many disabilities? Absolutely! But this is not what defines whether or not you are disabled. It doesn't matter if your condition is naturally "good" or "bad", because you're going to have a bad time regardless because we don't live in a pool with kind lifeguards, we live in a society run by greed.

Long story short, both the different swimmer and the non swimmer are disabled in a pool that doesn't allow them to swim. They are both subjugated.

This is the social model of disability.

#disabled#actually autistic#autistic#disabilties#mentally disabled#autism#disabled theory#disability theory#social model of disability#social model#ableist society#ableism#fuck ableists#mentally disabled pride

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The emphasis on nation and national fitness obviously plays into the metaphor of the body. If individual citizens are not fit, if they do not fit into the nation, then the national body will not be fit. Of course, such arguments are based on a false idea of the body politic—by that notion a hunchbacked citizenry would make a hunchbacked nation. Nevertheless, the eugenic “logic” that individual variations would accumulate into a composite national identity was a powerful one. This belief combined with an industrial mentality that saw workers as interchangeable and therefore sought to create a universal worker whose physical characteristics would be uniform, as would the result of their labors—a uniform product

Davis, 2013, ‘Normality, Power, and Culture’

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disabilities I

Since I have some time, I'll tell you all a bit about what the deal is with my disability, and why I am writing about disability in my dissertation.

Back in 2012, I got into a car accident. My girlfriend (now wife) was in the car with me, but I bore the brunt of the impact, and as a result, got some moderate spinal damage. That resulted in me going to physical therapy for a few months, but the lasting damage resulted in fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia isn't so much as a single disease, as it is a cluster of related symptoms that don't neatly fit into one classification or particular syndrome. It's more like, "you don't have x, y, or z, but you have all the same symptoms, so we're going to put you in the big bin that's labeled TO BE SORTED LATER." This is gross simplification, of course, but it's close enough for jazz.

Fibromyalgia is mostly related to a conjunction of hyperactive and inflamed nerves, chronic fatigue, and chronic pain. My body thinks I have an infection or an injury, but there is none there, so I get all the lovely side effects of my body fighting off or healing itself without the benefit of actually healing or fighting off an illness. It's not great! It's often comorbid with depression and anxiety, which I also have.

Really, the only reason I was able to get the fibro diagnosis was because my partner ALSO has fibro, and the only reason she knows she has it is because her sister has it! No one thing causes it, but it is often related to genetics or physical trauma. She saw all the signs of it in me, got me to see a rheumatologist, and sure enough, I have all the signs of fibro.

What I struggle most with is with the nerves and the exhaustion. I have chronic fatigue, and the rest I get from sleep isn't all that restorative. Whereas most people tend to wake up rested, I wake up more or less the same amount of tired a regular person feels before going to sleep.

I'm relatively lucky, to be honest. I'm able to manage my pain and such with medication. I'm even able to go to the gym a few times a week, energy permitting. But that takes a lot of effort, and I probably don't see all the benefits a regular person would get from exercise because of a cluster of reasons, related to my thyroid, fibro, and other things.

Oh, and just this past year, I've gotten serious about addressing my latent ADHD. I've had it all my life, but the difference now is that I'm trying to write a goddamn book, and that takes a lot more mental energy and organization than I usually have. This may be needed to addressed in another post, but the fact of the matter is, I'm taking a lot longer to write this thing than most people, partly because I'm working full time, and partly because my brain simply does not work like most neurotypical brains and requires a lot more effort to simply write one page whereas others might be able to knock out much more in a night than I would with the same amount of effort.

So there's my disabilities as they stand. I'll probably try to talk a bit more about them in future posts. It's an ongoing conversation, but having been diagnosed with disabilities like this has given me a much greater focus on the issues disabled folks face in society, and in my case, the church.

Writing about disability is both freeing but also complicated. Nobody experiences the same disability the same way, and can be affected by comorbidities that result in different experiences. I'll try to be as honest about my struggles with disability as possible, because it's good to get these stories out into the world and out of my brain. But also? We shouldn't be afraid to talk about our disabilities. In all statistical likelihood, you will be affected by a disability, either in your life or in a loved one's life. So it's good to be honest about struggles and joys related to disability, because if we can normalize it, we can understand each other better and work together to form a better community. One that treats each other as co-equal humans, worthy of love and respect.

5 notes

·

View notes