#Frank O'Neill

Text

On Borrowed Time (1939)

As time marches on, certain names that were once synonymous with American drama lose their weight, even among film buffs. In the early twentieth century, the Barrymore siblings – Ethel, John, and Lionel – were celebrated on both Broadway and in Hollywood, each one making a successful transition from the silent era to synchronized sound. The eldest, Lionel, was born in 1878 and was a Hollywood elder statesman when he made 1939’s On Borrowed Time. Directed by Harold S. Bucquet and based on a 1938 play of the same name by Paul Osborn (itself based on a 1937 Lawrence Edward Watkin novel of the same name), On Borrowed Time is a star vehicle for the eldest Barrymore. By the late 1930s, Barrymore had broken his hip twice – never healing properly. As such, he remained wheelchair-bound for the remainder of his life. Physical disablement, even in modern Hollywood, often curtails acting careers. But Barrymore’s home studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), often had their screenwriters find ways to incorporate Barrymore’s disability.

Lionel Barrymore was also in physical pain and depended on cocaine injections to work and sleep. However, this never affected his acting, as he delivers a wonderful lead performance in On Borrowed Time. Those less knowledgeable about this period in Hollywood history will probably only recognize his surname and the acting family he came from. Nowadays, most cinephiles probably only know of Lionel Barrymore through It’s a Wonderful Life (1946; Barrymore played the villainous Mr. Potter). Lionel Barrymore's role as the somewhat foul-mouthed but caring grandfather here offers something completely different.

Mr. Brink (Cedric Hardwicke) is hitchhiking somewhere near a small town in contemporary America. But he is not interested in riding with just anyone:

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: May I give you a lift, sir?

MR. BRINK: Thank you, no. I have an appointment – a lady and gentleman.

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: Oh, I’m sorry. [coughs] I thought you signaled me.

MR. BRINK: No. Not yet...

As you may have guessed, Mr. Brink is a personification of death. A few minutes later, he flags down that lady and gentleman and takes their lives in a car accident. That couple are the parents of John “Pud” Northrup (Bobs Watson; best known as Pee Wee in 1938’s Boys Town), who will now live solely under the care of Gramps and Granny (Barrymore and Beulah Bondi) and their housemaid Marcia (Una Merkel). At the memorial service for Pud’s parents, Gramps donates a substantial sum to the church. After learning of Gramps’ generosity, Pud exclaims that his grandfather doing such a good deed should allow him a wish. Gramps’ wish: as a deterrence local children stealing his apples, he wishes that anyone who climbs up his apple tree will be stuck there until he permits them down. Some time later, Mr. Brink arrives at Northrup grandparent homestead for an appointment with Gramps. Gramps tricks Mr. Brink up the apple tree, trapping him there – setting off a series of developments that put Gramps in a moral bind.

In a cast already headlined by character actors, how about some more? On Borrowed Time also features Henry Travers (the guardian angel Clarence in It’s a Wonderful Life) and Nat Pendleton as neighbors, Grant Mitchell as Gramps’ lawyer, James Burke as the sheriff, Charles Waldron as the reverend, and an uncredited Hans Conried (Captain Hook and Mr. Darling in 1953’s Peter Pan) as the man in the convertible.

Elsewhere, away from the camera, one can’t find much of composer Franz Waxman’s (1935’s Bride of Frankenstein, 1951’s A Place in the Sun) string-dominated score anywhere, but this is one of Waxman’s finest scores of his early career.

The opening half-hour of On Borrowed Time are its weakest. Hardwicke’s Mr. Brink has an eerily charismatic first impression that the scenes immediately following it cannot hope to match. Instead of learning more about the nature of Mr. Brink, the film instead shows us some of Pud’s misadventures and his relationship with his grandparents. Strangely, the loss of his parents seems to have had little effect on Pud at all, although his sadness seems to emerge in his contentious relationships with the other local boys and Aunt Demetria (Eily Malyon). Aunt Demetria, shortly after the Northrup parents’ deaths, hatches a scheme to assume guardianship of Pud and attain access to his considerable inheritance. Her designs are so obvious to all that when Gramps and Pud start calling her a “pismire” (literally, a pissing ant), Granny looks the other way when she might otherwise correct their boorish behavior. All of this takes longer to develop than it should (it does not help that Bobs Watson’s performance as Pud feels disjointed, but more on that shortly), even if the opening act primarily serves to show us how close Pud is to his grandparents. Even though we sense where the dramatic stakes are headed, On Borrowed Time almost seems to splinter into another film before we see Mr. Brink again.

In addition, contemporary reviews of On Borrowed Time lambasted screenwriters Alice D.G. Miller (1929’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey) and Frank O’Neill (no other film credits) for sanitizing the language from the original stage play due to the demands of the Hays Code (the self-censorship code that applied to major Hollywood studios from 1934-1968, repealed in favor of the current MPA ratings system). For the record, the text of the stage play was not freely available as I was writing this piece, so I have no means of comparison. Paul Osborn’s On Borrowed Time has only appeared on Broadway thrice: the 1938 original production and short-lived revivals in 1953 and 1991. The play had also been adapted for radio and television.

Compared to those film reviewers during the film’s 1939 release and many modern writers, I tend to be more forgiving if the Hays Code-enforced changes to a film do not significantly alter the spirit of the text. Sure, it would be funnier to hear disparaging language stronger than “pismire” in a 1939 film, but Pud’s and Gramps’ feelings towards Aunt Demetria, the apple-stealing boys, and Mr. Brink are comprehensible in this movie.

The closing two acts of On Borrowed Time draw its strengths from the performances and the narrative’s adoption of fairy tale logic (any film beginning with death flagging down folks he has an “appointment” with is almost always operating under the terms of the fantasy genre). In tandem, Lionel Barrymore and Bobs Watson’s good-humored and loving rapport lift the film above its structural flaws. Barrymore’s Gramps – an American Civil War and Spanish-American War veteran* – is a classic small town curmudgeon, only allowing his bitter exterior to crumble when Granny and Pud are around. Looking to protect Pud from Aunt Demetria, Gramps remains defiant towards the wills of Mr. Brink and the insistent neighbors. Perhaps it is not the greatest Lionel Barrymore performance, but he is always effective.

Bobs Watson, as Pud, is inconsistent anytime he does not share the scene with Barrymore. The explanation for his performance comes from Watson himself: “My dad was the one that really directed me, and I think some of the directors resented it a little bit… I trusted my dad implicitly, so I read the dialogue the way he told me.” His father’s influence results in occasionally overcooked line readings against director Harold S. Bucquet’s vision (MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, 1943’s The Adventures of Tartu), more theatrical than what the scene calls for. But when the scene calls for crying, by golly can Watson (who had a reputation for crying on cue) deliver. And his scenes with Barrymore are beautifully acted, convincingly showing the audience the love between grandson and grandfather.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, a noted Shakespearean actor, cuts no corners as Mr. Brink. Mr. Brink is aware that, in time, he will keep all his appointments. Hardwicke plays Brink as slightly menacing, always dignified (no one expects that perfect an English accent in rural America), and somewhat aloof to what he probably thinks are childish trivialities and life’s mundane moments. He is the antagonist, but in no way is he the villain of this movie. That belongs to Eily Malyon as Aunt Demetria, a character some compare to Margaret Hamilton’s Mrs. Gulch/Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz (1939; released a little more than a month after On Borrowed Time) due to her temperament and unbending nature. One wishes the film made more use of the always-underappreciated Beulah Bondi as Granny (Bondi very often played elderly mothers and grandmothers, almost always appearing much older than she actually was), too.

Death and loss are two themes currently popular in modern cinema (see: a vast bulk of Pixar’s filmography, 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, 2019’s The Farewell, and a large selection of pieces from any film festival worldwide), but in the early decades of talkies in Hollywood, you would be hard-pressed to find films in which those themes were truly central, not secondary, to the narrative. And when those themes do appear, they appear in the context of fantasy films, like Death Takes a Holiday (1934) and On Borrowed Time. Anecdotally, I suspect the scarcity of major Hollywood movies revolving around death and loss is partly due to the realities of the 1930s and 1940s. Audiences, concerned with a worldwide Great Depression and soon a Second World War, did not seek films ruminating about death and loss and sought escapist fare instead. There was enough despair to go around.

The film that emerges on the back of these performances is thanks to its ability not to concentrate on the fantastical situation the Gramps and Pud find themselves in, but to raise the moral questions that Mr. Brink’s presence – and eventual entrapment – poses. Mr. Brink’s time in the tree results in consequences that Gramps and Pud could not imagine. Gramps’ decision to delay his death for the love of his grandson is concurrently noble and selfish. It is noble in respect to wanting the best for Pud, so that he may live life away from his aunt’s icy attitude and pernicious designs regarding her nephew’s inheritance. But it is selfish in that, as Gramps learns, that Brink’s inability to make any appointments unless he comes down from the apple tree means that almost no living being can die (for spoiler reasons, I am not listing the exceptions here) – even the ones in physical pain. How is Gramps supposed to navigate this situation, in addition to the communal and legal pressures from his neighbors and the police?

A resolution comes abruptly, in a way that devastates Gramps (but would probably make the Brothers Grimm nod in appreciation). On Borrowed Time’s bittersweet ending is deserved, and – as long as the viewer accepts the film’s fantastical premise and rules – will play quite differently for audiences of different ages.

Lionel Barrymore had two daughters with Doris Rankin, his first wife. Barrymore and Rankin lost both daughters in their infancies; neither ever truly recovered from their losses. One wonders what Barrymore thought while making On Borrowed Time, a film that argues for one coming to terms with death, however unfair or untimely its arrival. For a 1939 release (a legendarily glorious year for American cinema), positioning such ideas as the film’s narrative keystone ensures On Borrowed Time a unique spot in the early years of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* Gramps describes himself as having fought for the Union. This might make Gramps close to ninety years old, give or take, if we are to believe the film’s self-professed setting!

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

NOTE: This is the 800th full-length Movie Odyssey review I have published on tumblr.

#On Borrowed Time#Harold S. Bucquet#Lionel Barrymore#Beulah Bondi#Cedric Hardwicke#Bobs Watson#Una Merkel#Nat Pendleton#Henry Travers#Grant Mitchell#Eily Malyon#James Burke#Charles Waldron#Alice D.G. Miller#Frank O'Neill#Lawrence Edward Watkin#Paul Osborn#Franz Waxman#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

✨caution! Izzy rant ahead✨

Every time I see posts villainizing Izzy I'm kind of baffled. I know i should have gotten over it by now

but making Izzy the villain is kind of missing the heart of the whole story?

"Oh no, Gentlebeard is the heart of the story-"

It's a story about found family. About dysfunctional people. People who err and fail and make horrible decisions and overcome their traumas.

I know that's not lost on the fandom when it comes to Ed, not one little bit. He's all cute and bored when we meet him, right?

Not the man who sets ships alight anymore, with all the people in them?

Not a psychopat, just a tired little boo who's ready to shake off Blackbeard's mantle?

And it's great that he's ready. People get there. But what I get from many posts is that it's fine for Ed to get there when he's ready but Izzy had to follow him straight away into the land of the mentally healthy or fucking die.

Only Izzy is just as dysfunctional as good old Ed if not more, and he's not ready, and nobody is asking him to be ready when they board the Revenge.

The only person he feels close to in the world ignores him, Stede (understandably) offers him none of the talk-it-through treatment and the crew mocks him.

All within reason, but when you have severe mental issues and trust issues and defense mechanisms your first instinct is not to open yourself up.

It's to lock yourself down. Bite back at those who mock you. Attack those who disdain you. Destroy your chances of happiness, because you think you dont deserve it.

Wrong approach? yes, god, yes, of course it is, but "wrong approach" is basically the title of every other episode in this show.

Now I know that many of you see maiming (not a one time thing either. continuous maiming) as a suitable payback for Izzy's deal with the English.

(Maybe you don't even see what baffles me in that statement)

"I fed your darkness. Blackbeard" has been quoted as a closing statement more times than I can count.

Everybody can read into "I fed your darkness" as they please; I know how I read into it. I've been in love with people who's darkness I fed and they fed mine in return.

And I'm not even going to point any fingers here, regardless of how disproportionally abusive that relationship was.

It's a we thing, it's always a we thing. Darkness feeds on darkness.

Izzy didn't create Blackbeard. Izzy didn't burn that fucking ship with all the people in it. We don't even know if Izzy met Ed before he was Blackbeard or not.

It was most likely a "we" thing, where they built together upon an existing structure, a joint tower of darkness. Feeding the myth, throwing all of their insecurities in it, creating a monster.

Forging a bond not with the touch of silk and gentle fingers but with whatever nightmares you can imagine.

So Izzy playing doctor Frankenstein to Ed's Kraken is…it's wrong, it's simply wrong. Ed was not a corpse when they met. He was not a blank slate. He was probably already a mess of his own

when the darkness-feeding started.

That turned out to be quite the rant but it's important for me to voice it.

Izzy is far from blameless. Ed is far from blameless. A lot of other people in this show are technically far from blameless.

But making a person who's a member of (the ofmd) family your villain?

There are some straightforward villains in this show and then there are those who want to, crave to, strive to belong but have a hard time because they're so genuinely flawed.

#ofmd#ofmd gifs#our flag means death#izzy hands#con o'neill#as you can see I'm an Izzy apologist#I'll be frank for a long time I didnt even know I had to apologize for Izzy#that's how oblivious I can be#but also my reasoning was “why would he need to apologize with that face”

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎃TRICK OR TREAT

Mikey is a mummy, Leo is d'Artagnan, don Seymour from The Little Shop of Horror and Raph wear a t-shirt with costume written on it because he is that type of losers.

I'm gonna do the same for 2003, 2012, Rise and MM.

#shredder#shredder is dressed as Dr. Frank-N-Furter#krang is Rocky#april is cheetah#Irma is wonder woman#tmnt#tmnt 1987#teenage mutant ninja turtles#tmnt 87#87 shredder#krang#87 april o'neil#irma langinstein#teenage mutant ninja turtles 87#oroku saki#tmnt fanart#tmnt leonardo#donatello#raph tmnt#mikey tmnt#donnie#raph#leo#mikey#tmnt michelangelo#raphael#87 leonardo#87 irma#87 raph#krang 1987

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

SO YOURE TELLING ME CON O’NEILL WAS SUPPOSED TO PLAY BILL BUT COULDNT CAUSE HE WAS DOING OFMD JDHDJDJDHSJJSJHDJSJD

I honestly don’t know if I’m happy or not with how it turned out. Cause on one hand is Con the best choice of actor to ever play Izzy? Of course Yes. Did I absolutely bawl my eyes out at Nick Offerman and Murray Bartlett? Absolutely Yes. Would I want to see Con play Bill? ABSO FUCKING LUTELY

#ofmd#tlou#con o'neill#bill and frank#nick offerman#murray bartlett#our flag means death#the last of us#tlou show#hbo#izzy hands

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

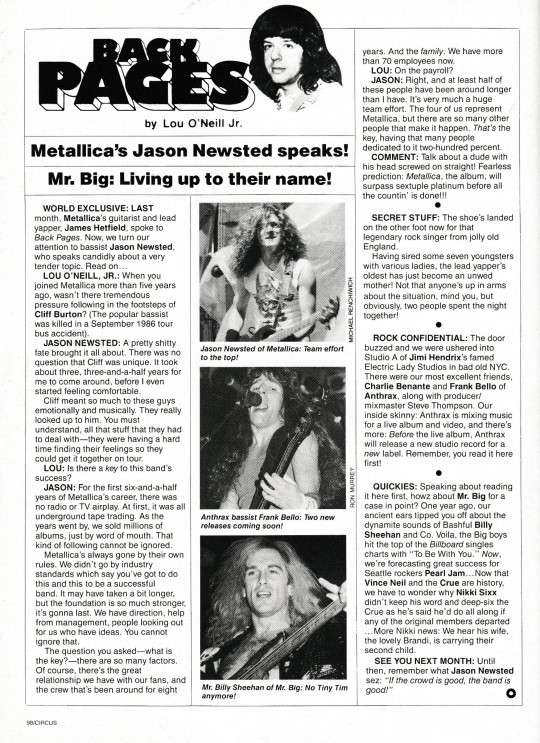

#circus magazine#circus#lou o'neill jr#jason newsted#metallica#frank bello#anthrax#billy sheehan#mr. big

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daredevil by David Mazzucchelli (from 1985's Daredevil #226).

#daredevil#david mazzucchelli#moody#frank miller#denny o'neil#gladiator#kingpin#wilson fisk#fisk tower#matthew murdock#foggy nelson#Melvin potter#just before born again#80's#80s#1980s

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

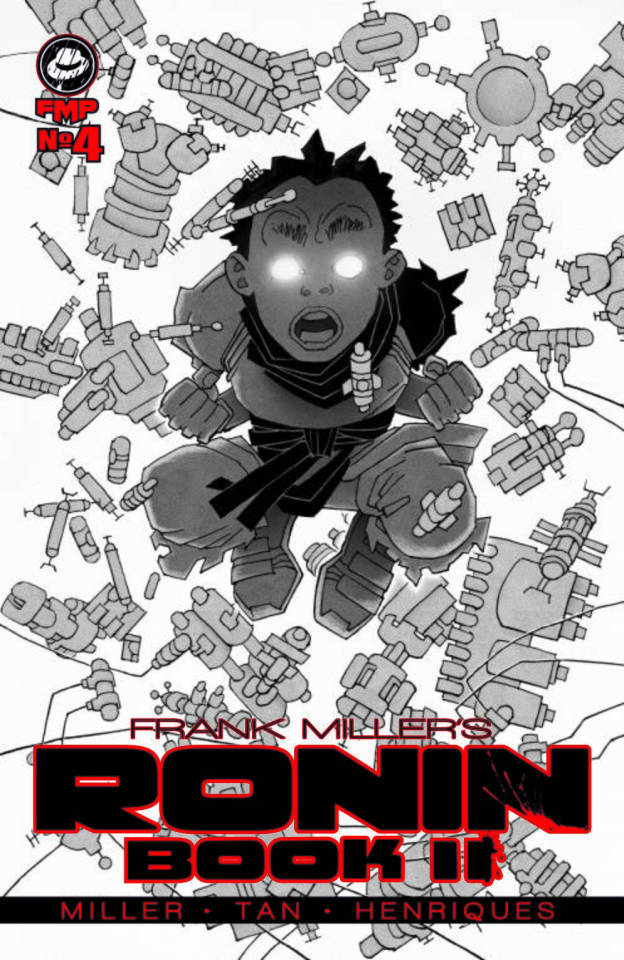

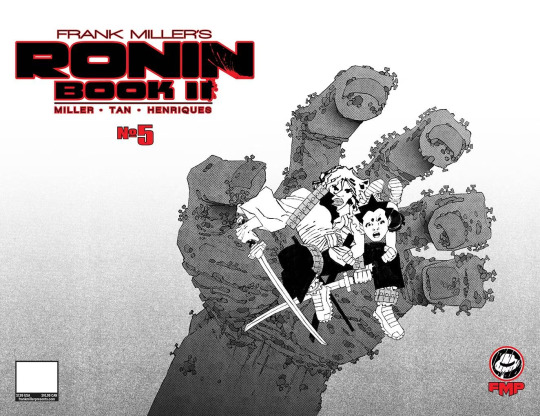

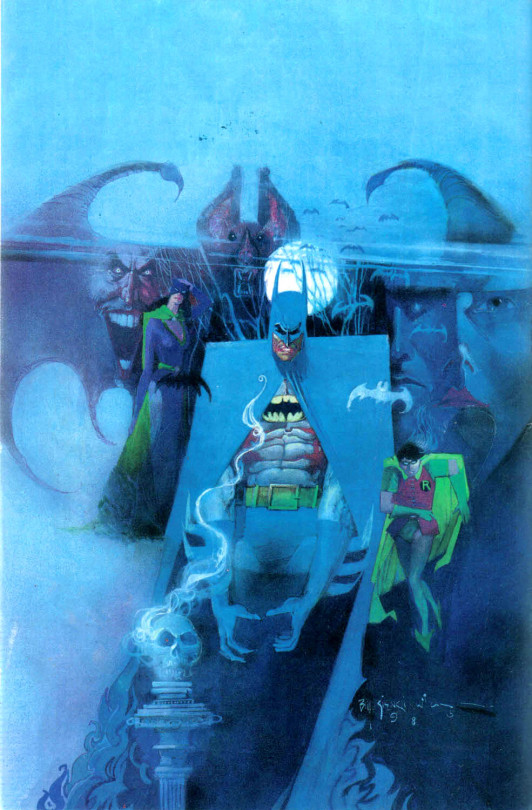

Frank Miller's variant covers for Ronin Book Two.

And here's a great little write up by Tegan O'Neil at The Comics Journal about the original and it's sequel.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daredevil #18 - "There Shall Come a Gladiator!" (May 1966)

Written by Stan Lee and Dennis O'Neil

Art by John Romita Sr. (pencils), Frank Giacoia (inks)

#daredevil#daredevil comics#foggy nelson#john romita sr#frank giacoia#dennis o'neil#frank ray#marvel#marvel comics#stan lee#back issues box#oh foggy foggy foggy... i love you... take off the suit before you do something foolish! (he will not take off the suit and will be foolish

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

#literally the blueprint for every character i love#they're all like this?!?#steve rogers#captain america#derek hale#jim hopper#rip#john mcclane#frank castle#the punisher#stiles stilinski#steve harrington#evelyn salt#harley quinn#wonder woman#jack o'neill#teal'c#to name a few

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jellycat plushies I think LWA characters would have (I do not take constructive criticism)

Akko:

Lotte:

Sucy:

Diana:

Amanda:

Constanze:

Jasminka:

Andrew:

Frank:

#lwa#little witch academia#atsuko kagari#lotte jansson#sucy manbaravan#diana cavendish#amanda o'neill#constanze amalie von braunschbank albrechtsberger#jasminka antonenko#andrew hanbridge#frank lwa#alternatively frank would just have the dumbest one known to man#like the goofy looking shrimp i found while googling this lmao

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the World a Stage ch. 16

In the aftermath of disaster, those still able must pick up the pieces and make the best of a terrible situation. After all, no matter the casualties they sustained, tomorrow was still going to come and had to be met head on.

Found on AO3, 16324 words. Co-written with @ameliamircalla

CW: Some extra blood this chapter... surgical suites can get messy.

#little witch academia#diana cavendish#akko kagari#diakko#hannah england#amanda o'neill#barbara parker#lotte jansson#frank lwa#zatanna zatara#anna lwa#batwoman#supergirl#like words on the page#all the world a stage#I am very tired#let me rest

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

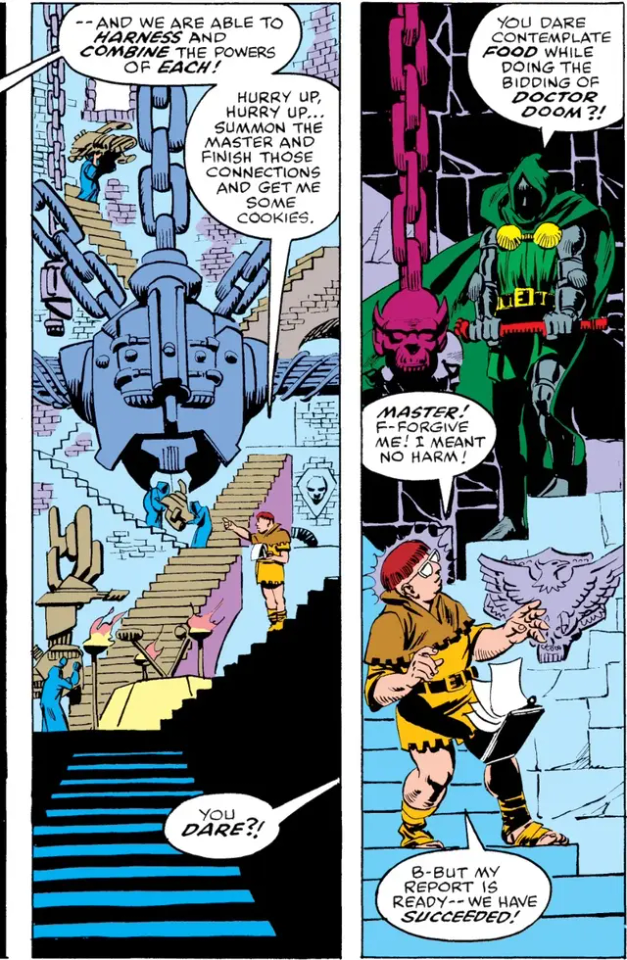

No Cookies While Working For Doom:

Source: Amazing Spider-Man Vol 1 Annual #14 by writer Denny O'Neill and artist Frank Miller.

#doctor doom#victor von doom#spider-man#funny#denny o'neill#frank miller#marvel#comics#marvel comics

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Death in the Family, or: How DC Comics Let a Phone Vote Kill Robin

[reposted from r/HobbyDrama on Reddit]

DC Comics has published literally thousands of Batman comics in the character's eighty-odd years of existence, but few are more infamous than A Death in the Family, when DC let fans decide whether Jason Todd, the second character to use the identity of Robin, lived or died.

An apology in advance: many primary sources for this drama have been lost to the annals of history: this was the 1980s, the Internet wasn't really a thing yet, so fan discussion around comics mostly took place in Usenet newsgroups and comic book letter columns, both of which are very difficult to find archives of today. I've reconstructed the story as best as I can, but I wish I could find more quotes from fans at the time.

Also, SPOILER WARNING. There are unmarked spoilers for Batman comics from the 1980s below. Don't say I didn't warn you.

Who was Jason Todd?

Jason Todd was a character introduced in 1983's Batman #357 by writer Gerry Conway and artist Don Newton and under the auspices of editor Len Wein, as a replacement for Dick Grayson as Robin. Grayson had outgrown the pixie boots and scaly shorts of the Robin identity, and graduated to his own identity as Nightwing, over in The New Teen Titans. But Conway felt that Batman still needed a Robin, so Todd was born:

Gerry Conway (writer, Batman and Detective Comics, 1981-1983): I always felt that Batman worked really well with a sidekick like Robin. My interest in the character was the version of Batman as a detective, the version of Batman as a guardian of Gotham. This was prior, I believe, to the deep-dive into the “dark knight” kind of concept of Batman, so, for that end, the idea of a younger sidekick who could bring out a little more levity in the character seemed useful. But Dick Grayson as a character had grown into a young adult and was integral to the Teen Titans series, and had his own life and his own storylines that were developing separately from Batman, and [he] couldn’t really play that secondary role that I was interested in exploring. [1]

Todd was introduced as the son of two acrobats who had been murdered by Batman's enemy Killer Croc, in a striking similarity to Dick Grayson's origin written forty years prior. Todd would officially become the new Robin in Batman #368, published February 1984, and would continue to go on adventures (written by Conway and then by Doug Moench) with Batman until 1986's Batman #400. During this period, he's probably best remembered for a. being involved in a custody battle between Batman and a vampire, and b. getting the drop on Mongul in the classic Superman story "For the Man Who Has Everything" by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons.

But then the Crisis happened, and everything changed for Jason.

The Crisis

You don't have a comic book company for almost fifty years without running into some hurdles along the way, especially where characters and continuity are concerned. In 1954, psychologist Frederick Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a book asserting that comic books were harming the children of the day, causing them to turn into delinquents. As a result, the bustling superhero genre of comics at the time slowed to a crawl, with most of DC's (then known as National Periodical Publications) characters, such as the Green Lantern and the Flash, ceasing publication and being replaced with comics about talking animals, romance stories, and giant alien monsters.

Just a few short years later, in October 1956, creators Robert Kangher and Carmine Infantino would introduce a new version of the Flash in Showcase #4, and the Silver Age of comics had begun. Eventually, the Golden Age Flash was reintroduced, and it was established that the Silver Age characters resided on Earth-One, while the Golden Age characters were from Earth-Two. Everything was fine and dandy, until DC decided things had become too confusing and that they needed to kill their multiverse.

In 1986, DC published one of the very first comic crossover events - Crisis on Infinite Earths, an earth-shattering story that pitted almost every hero in company history against the threat of the Anti-Monitor. The outcome was that all the characters and stories from Earth-One, Earth-Two, and several other alternate Earths that had appeared over the years were consolidated into a single, streamlined universe, and with that came changes for several other characters, Jason Todd among them.

The New Jason Todd

After Crisis, new blood was in the Batman editorial offices. Former Batman writer Denny O'Neil had taken over as editor of the Batman family of titles, and he had a different opinion on Robin than that of Wein and Conway before him.

O’Neil: There was a time right before I took over as Batman editor when he seemed to be much closer to a family man, much closer to a nice guy. He seemed to have a love life and he seemed to be very paternal towards Robin. My version is a lot nastier than that. He has a lot more edge to him. [1]

In keeping with the desire for a darker, edgier Dark Knight (it was the 1980s, after all), this version of Batman debuted without a Robin by his side. Dick Grayson was still Nightwing, but Jason Todd was nowhere to be seen. This darker interpretation of Batman was only solidified once Frank Miller put his touch on the franchise with "Batman: Year One" in Batman #404-407, and the standalone graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns, the impact of which cannot be understated.

The Dark Knight Returns was a pivotal moment in the formation of what we would consider a recognizably “modern” incarnation of Batman, someone who is brooding and dark, a loner who isolates himself from society to obsessively carry out his one man crusade by any brutally violent means necessary. It was also an important milestone for comics a medium when it landed on top of the Young Adult Hardcover New York Times bestsellers list—a feat it only qualified for thanks to its release as a trade paperback in bookstores. For the first time, mainstream audiences were zeroing in on Batman, and not because of a popular TV show or serialized movies, but because of a comic book. 2

Immediately following "Year One," O'Neil asked writer Max Allan Collins to reintroduce Jason Todd as Robin into the continuity, in a storyline titled "Batman: The New Adventures" starting in Batman #408. The new Todd was a delinquent orphan, caught by Batman when he tried to steal the tires from the Batmobile and taken in and trained to be the new Robin.

At first, the change was controversial among the fandom, especially given the wildly contrasting takes between Mike W. Barr's softer portrayal of the Dynamic Duo in Detective Comics and the harsher portrayal from creators such as Collins, Jim Aparo, and Jim Starlin (best known now as the creator of Thanos) in Batman. But nobody was clamoring for his death yet, and the intensity of debates around the new Jason Todd, fought out through comic book letter columns, were milder in comparison to those around whether there should be a yellow oval on the Batsuit or not. [3]

Over the next few years, fan hatred for Jason began to grow, as the new incarnation of the character was not only a replacement for a highly beloved character, but also had a lot of anger issues to sort through. But then came the boiling point - Batman #424, written by Starlin and pencilled by Mark Bright, released October 1988. In that story, Todd confronts Felipe, son of a South American diplomat who was heavily involved in the cocaine trade. Batman reasons that, because Felipe has diplomatic immunity, there's nothing he can do to stop him, but Todd thinks otherwise. Felipe falls from a skyscraper to his death, leaving Batman to wonder: "did Felipe fall... Or was he pushed?"

(Starlin, for what it was worth, hated Todd from the get-go, and specifically wrote this story to play to the controversy:

Starlin: In the one Batman issue I wrote with Robin featured, I had him do something underhanded, as I recall. Denny had told me that the character was very unpopular with fans, so I decided to play on that dislike. [1]

He had also tried to have Todd killed beforehand, of AIDS:

Well, I always thought that the whole idea of a kid side-kick was sheer insanity. So when I started writing Batman, I immediately started lobbying to kill off Robin. At one point DC had this AIDS book they wanted to do. They sent around memos to everybody saying “What character do you think we should, you know, have him get AIDS and do this dramatic thing” and they never ended up doing this project. I kept sending them things saying “Oh, do Robin! Do Robin!” <laughs> And Denny O’Neill said “We can’t kill Robin off”. [4]

A Death in the Family

By 1988, though, O'Neil had changed his tune. Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's The Killing Joke had left longtime supporting character Batgirl brutally paralyzed, to major praise from fans and critics alike, and there was blood in the water. Sales for Batman were at levels not seen for over a decade thanks to the works of Miller and Moore, Tim Burton's Batman feature film was on the horizon, far removed from the camp aesthetic of Adam West and Burt Ward and entirely Robin-free, and fan hatred for Todd was at an all-time high.

Jenette Kahn (publisher, DC Comics, 1976-1989; president, 1981-2003; editor-in-chief, 1989-2003) : Many of our readers were unhappy with Jason Todd. We weren’t certain why or how widespread the discontent was, but we wanted to address it. Rather than autocratically write Jason out of the comics and bring in a new Robin, we thought we’d let our readers weigh in. [1]

O'Neil and his team of editors brainstormed how they could remove Jason from the story, and the answer was clear: kill him, just as Starlin had suggested time and time again. Recalling the success of a 1982 Saturday Night Live sketch in which Eddie Murphy let viewers vote via phone on whether he would cook or spare a live lobester, O'Neil proposed a similar system to Kahn, who loved the idea.

So, A Death in the Family began in Batman #426, written by Starlin and illustrated by Jim Aparo. When Jason receives word that his missing mother is alive, he follows a set of leads across the world to find her, only to discover that she was being blackmailed by the Joker. Jason's mother hands him over to the Clown Prince of Crime, and that's how Batman #427 ends. On the back cover of that issue, DC ran a full-page ad, proclaiming: "Robin Will Die Because the Joker Wants Revenge, But You Can Prevent It With a Telephone Call" and giving two 1-900 numbers: one to call to save Jason, and one to kill him.

Two versions of issue #428 were written and drawn. One where Jason lived, and another, where he died. Both went into a drawer in O'Neil's desk, and the fans would choose which one would ever see the light of day.

The fans went rabid. One letter, published in Batman #428, read as follows:

"Dear Denny, I heard some of what you are planning for "A Death In the Family" story line, including the phone-in number wrinkle, and I don't want to take any chances whatsoever. Kill him. Your pal, Rich Kreiner."

From 9:00 in the morning on Thursday, September 15, 1988 until 8:00 in the evening on Friday, September 16, fans could call in to either of the two numbers for fifty cents a call and cast their vote. In the end, the votes were tallied: 5,271 voted for Todd to survive, and 5,343 voted for him to die. By a margin of 72 votes, Robin died in the pages of Batman #428, beaten to death with a crowbar by the Joker. The image of Batman cradling Robin's dead body became immediately iconic.

The Reaction

Fan reaction to the story was mixed, despite the seeming fervor for Todd's death and the blood that was on their hands. The letters pages for Batman #430 (1, 2) show a mixture of celebration over Jason's death, remorse over individuals' decisions to vote for death, and hope that Robin's absence would lead to more mature Batman stories in the future. However, every issue of A Death in the Family was a best-seller, and a collected edition was rushed out in early December of 1988, only a week after the final issue in the arc was released to stores.

But now that the fan feeding frenzy was (mostly) over, the media feeding frenzy had begun. You don't just kill Robin and get away with it without media attention. USA Today and Reuters ran articles on the story, and DC was besieged with interview requests from radio and TV stations.

O’Neil: I spent three days doing nothing but talking on the radio. I thought it would get us some ink here and there and maybe a couple of radio interviews. I had no idea—nor did anyone else—it would have the effect it did. Peggy [May], our publicity person, finally just said, “Stop, no more, we can’t do anymore,” or I would probably still be talking. She also nixed any television appearances. At the time, I wondered about that but now I am very glad she did, because there was a nasty backlash and I came to be very grateful that people could not associate my face with the guy who killed Robin. [1]

Internally at DC, there were suspicions that the vote had been rigged in some fashion.

O'Neil: "I heard it was one guy, who programmed his computer to dial the thumbs down number every ninety seconds for eight hours, who made the difference." [5]

But regardless of whether it was or not, Jason Todd was dead, and he would remain dead for as long as O'Neil stayed at DC - long enough for the phrase to be coined: "nobody in comics stays dead except for Uncle Ben, Bucky, and Jason Todd." But he wouldn't remain dead forever.

Legacy

Jason would be succeeded by a new Robin, less than a year after his death. In a crossover storyline between Batman and New Titans written by Marv Wolfman and illustrated by George Perez and Jim Aparo, entitled "A Lonely Place of Dying", the character of Tim Drake would be introduced. Unlike Todd and Grayson before him, Drake would challenge the assumptions made about the character of Robin - he figured out Batman's secret identity on his own, and deduced that Batman needed a Robin by his side, to ensure he wouldn't take unneeded risks.

Gone were the short pants of yesteryear - Drake wore a full-body suit with an armored cape, and was more of a detective than a fighter. He debuted to mixed reactions, although fans soon grew to love him under the pen of Chuck Dixon, who would be one of the major architects of Batman in the 1990s.

Todd would get a second chance at life seventeen years later. In 2005, writer Judd Winick wrote the storyline "Under the Hood," published in Batman #635-641, 645-650, and Annual #25. There, it's revealed that Todd returned to life thanks to an alternate version of Superboy punching reality (it's comics, don't ask) and the aid of R'as al Ghul's Lazarus Pits, and donned the identity of the crime lord the Red Hood in his quest for revenge against the Joker.

Todd, as the Red Hood, persists as a popular character today, a lasting symbol of Batman's failure, as he operates as a pragmatic vigilante, willing to take risks Batman isn't.

#thekillingvote#DC Robin#Robin DC#DC Comics#Jason Todd#Batman comics#Batman#DC Joker#Joker DC#Batman A Death in the Family#The Dark Knight Returns#Frank Miller#Jim Starlin#Dennis O'Neil#1988#Pre Crisis#Post Crisis#serophobia#Jason Todd meta#comics#Batfamily#Batfam#Bat family#Batkids#Batbros#Batsibs#Batsiblings#comics history#Jim Aparo#ADitF

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 1972. Although the cover of DETECTIVE COMICS #426 is by Mike Kaluta, the Batman story inside — aptly entitled "Killer's Roulette!" — is both written and drawn by Frank Robbins.

Robbins was a comics veteran whose primary occupation from 1944 to 1977 was the syndicated newspaper strip JOHNNY HAZARD, which he created after a stint on SCORCHY SMITH. The latter strip was created by Noel Sickles, who was also a friend and former studio mate of Milt Caniff, on whose style Sickles had a strong influence. Robbins, unsurprisingly, had an adjacent style. Here's one of his relatively early JOHNNY HAZARD strips, from late 1945:

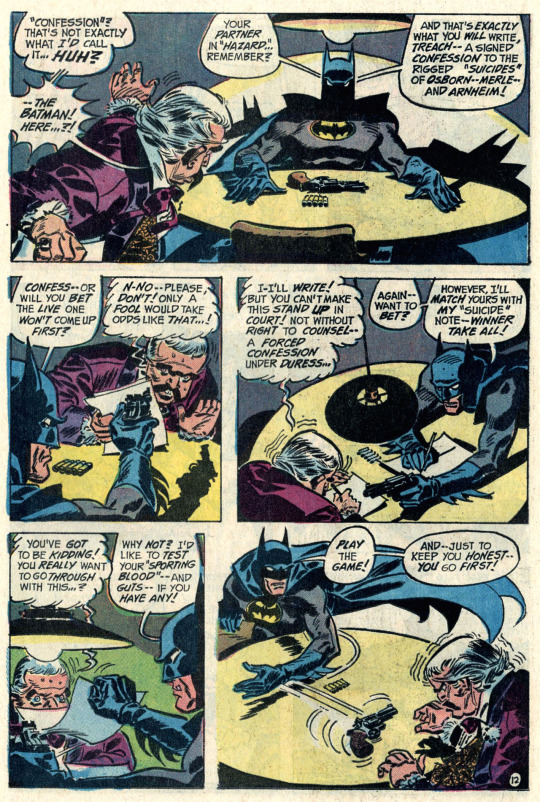

Between 1968 and 1974, Robbins became one of the regular writers of BATMAN and DETECTIVE COMICS, perhaps best-known today for writing the early appearances of Man-Bat. Robbins drew a handful of Batman stories himself, which always polarized readers expecting Neal Adams-like realism. However, all of those stories stand out for their atmosphere, energy, and storytelling skill. Let's look at a couple of pages of "Killer's Roulette!" as Batman confronts Conway Treach, a gambler with a taste for Russian roulette who's been linked to three apparent suicides in Gotham City:

The "partner in 'Hazard'" line is Robbins' in-joke: Bruce had previously introduced himself to Treach, while mildly disguised but out of costume, as a gambler calling himself "John T. Hazard" (which of course was Johnny Hazard's full name). Treach had invited "Hazard" to play Russian roulette, producing the revolver on the table for that purpose.

(Batman seems surprisingly unconcerned about the possibility of Treach recognizing "Hazard" as Bruce Wayne, which in an earlier era would probably have become a major preoccupation of the story.)

The revolver-chamber montage feels like something from the Batman stories of the early 1950s, with their fascination with oversize props, although it's certainly dramatic. As you may have surmised, Batman has deduced that Treach's revolver is gimmicked, which is why he remains so unflappable; both of them are actually in very little danger, although Treach is hoping Batman doesn't know that (and seems more than a little nervous about making a potentially lethal mistake with his own trick).

Denny O'Neil, the other principal Batman writer of this period, would not have written this story, at least not like this — O'Neil treated Batman as having a more or less pathological aversion to guns rather than simply disdaining them — and this sequence is surprisingly ruthless for Batman, gimmick or no. However, it's tightly constructed and quite tense, and it provides a greater-than-usual payoff of the issue's provocative cover.

#comics#detective comics#mike kaluta#frank robbins#batman#bruce wayne#johnny hazard#noel sickles#scorchy smith#suicide tw#guns tw#o'neil is much better known today#but i think robbins was the better writer

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

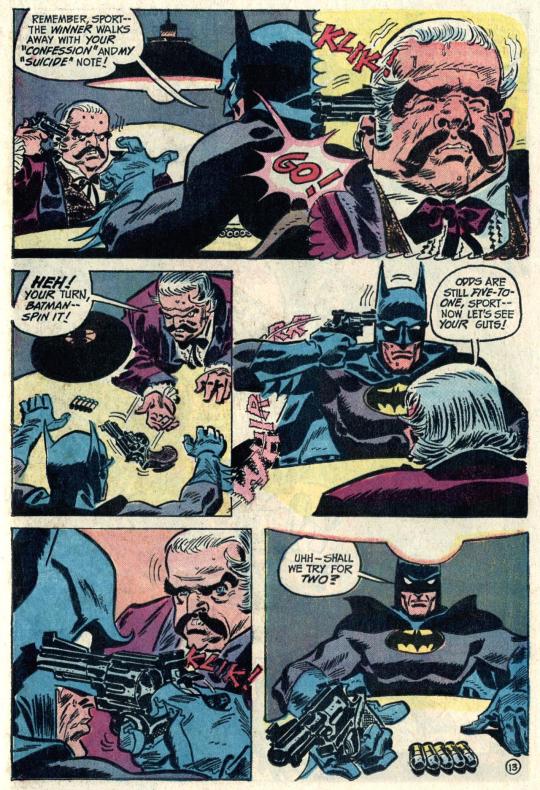

Bill Sienkiewicz's cover for 1986's Batman #400.

#batman#anniversary issue#mid 80s#crisis#frank miller#denny o'neil#DC#robin#joker#catwoman#1980s comics#bruce wayne#1986#big year fo the medium

34 notes

·

View notes