#the non verbal communication! the inherent closeness and being known!

Text

(pt 6/? stevetony ocean’s 11 au, ao3 link in bio)

“You’re out of your goddamn minds!”

Steve, admittedly, has to acquiesce to that. “It’s never been tried before…” he says, in an attempt to appeal to Fury’s daring and ambitious side.

Fury scoffs. “Oh, it’s been tried, three times, unsuccessfully. What do you have that the other three didn’t?”

“A divorce,” Bucky mutters under his breath. Nat steps in his foot under the table and he attempts to hide his wince, to no avail if Fury’s raised eyebrow suggests anything.

“I know casino security and these guys… they have enough ammo and people to occupy Paris. And even if you manage to make it out of there, with your money and your life you seemed to have forgotten that you’d still be in the middle of the fucking desert!”

“Would I go to you with a half-assed plan?” Steve challenges, then amends after Fury’s look, “Would Nat let me show you this with a half-assed plan?”

“Fine.”

“They’re Laufeyson’s places.”

Fury pauses for a second. He knows exactly why Steve and his little, soon to be expanded, gang came to him: he has money, an entirely justified vendetta against the greasy little fucker, and incredibly misplaced trust in Steve Rogers.

“If you’re going to steal from Loki Laufeyson you better be prepared for the aftermath. This sort of thing used to be civilised. You’d hit a guy, he’d whack you. Done. Laufeyson… at the end of this, he better not know you're involved, not know your names, or think you're dead. Because he'll kill you, and then he'll go to work on you.”

“I know,” Steve says, simply, “we’ve gotta be careful, precise. Well funded.”

“And batshit crazy,” Fury adds. “Who you got?”

“Well, we’ll need an AV guy…”

Bucky watches the patrons of a coffee shop go about their daily routines, bleary-eyed students amongst immaculately dressed businesspeople interspersed with tired parents desperately trying to console their children, eventually finding Clint despite his seemingly desperate attempts to blend in with the haggard students, if his dress and general demeanour is anything to go by. Clint spots him barely a second after.

“What do you need?” Clint asks, pressing a hot drink into his hand a minute later.

“Can’t I just visit a friend?”

“Sure. Just a little sus’ that you’re making a social call less than a week after Rogers’ got out, don’t you think?”

Bucky grunts and doesn’t even question how he knows that Steve got out, instead, he presses a plane ticket and an address into his hand. “You better make it. He’s planning on taking down Loki,” he tells him before he does a significantly better job of blending into the crowds.

“...a demo guy…”

“Thor?” Steve suggests. Nat shakes her head.

“Overseas.”

“Technically,” Sam interjects, “on the seas.”

Steve doesn’t groan aloud but it’s a near thing, “Don’t tell me he’s with…”

“Hey, last I heard he’s settling fantastically into the pirate life!”

“With a guy who takes advice from his pet raccoon.”

“With a guy who takes advice from his pet raccoon.”

To be fair, Steve doesn’t actively hate Quill and his gang of modern pirate mercenaries, he’s even worked with them before. But he does actively believe that Thor can do a lot better, though, if he’d blown up a small, mostly desolated Norweigian town and was on the run he too would go to sea.

“Well, who else do we have?”

Natasha watches from the safety of a cop car as alarms start blaring and, consequently, a stream of young, pretty criminals get arrested, Carol trailing behind at the end. She waits another minute, lets the real cops cuff her before she swoops in, flashes a badge and tells the disgruntled cop to “go get my partner, tell him we got this.” Under the guise of roughly handling her, she passes a set of materials to her, “That enough?”

Carol nods as Nat reminds the officer to go get her fictional partner. She hears a loud snap from behind Carol and she mutters “Thirty seconds.”

They make their way through the yellow tape, “Steve here?” Carol asks, tossing her makeshift explosive into an abandoned squad car.

“‘Round the corner,” Nat confirms, unlocking her handcuffs and tucking them into her pocket, “ten seconds?”

Carol grunts. “Almost. Be good working with professionals again.”

“Okay,” she says, after a beat, “go!” They both start running as Nat yells to her ‘colleagues’.

“Get down! There’s a bomb! Everybody down!!”

Amongst the chaos and mayhem, Carol and Nat manage to slip away mostly unnoticed; a baby in a strolling blinks distrustingly up at them as they pass them and their father, who appears to be very engaged in a phone call that seems to have taken a turn for the worst, but aside from that, they’ve made a fairly clean break.

“Captain.”

“Major.”

“Matt?”

“Isn’t he still mad at me?”

“He’s also still working pro bono for cherry pie.”

“You knock,” Steve tells Sam when they find themselves in front of a door that grandly declares that this is the location of Nelson, Murdock & Page.

Sam looks only slightly affronted. “Why me?”

“Matt doesn’t like me.”

Before they can carry on bickering the door swings open, and the man in question appears before their eyes. “Matt likes the Steve Rogers that doesn’t make him defend an undefendable case.”

“Aw, you think I’m undefendable?” Steev mocks, electing not to comment on the fact that 1. Matt talking in the third person heavily disturbs him, and he’s been to Jersey, and 2. he plead guilty.

“Ignore him” Sam interjects.

“Often do.”

“We have a score. Big one. Vegas.”

If emotions could radiate from people, Matt would be screaming suspicion and distrust. He doesn’t do well in casinos far too much input, though he has enough faith in Steve that he’s pretty sure he’ll never actually cross the threshold. “I’m the whole list, aren’t I?”

Steve looks in betrayal at Sam, “He’s the whole list?” Sam, as he also often does, ignores Steve.

“Combination of cons. One night. $150 million between us.”

“You’re lucky it’s a slow week,” Matt grumbles, before he shuts the door in their face.

“Well. That went better than I thought it would.”

Sam just rolls his eyes and shoves Steve in the general direction of out.

“Eight should be enough, right?”

Nat shrugs, mentally ticks through their current roster and matches the skill sets to jobs and watches Steve do the same.

“You think we need one more?”

Nat shrugs, tilts her head. She could do it, Matt could probably do it but...

“You think we need one more.”

Nat shrugs again.

“Okay. we’ll get one more.”

Steve doesn’t often get the subway. It brings back… interesting memories. This time, he’s not going particularly anywhere, just watching a guy who looks barely old enough to graduate high school - by recommendation of JJJ. The train comes to a sudden stop and all the commuters sway forth with the air of people who have come to expect it land have given up fighting it, like a child with a broken backpack, with the exception of Parker. He, committing subway etiquette blasphemy, bumps into a guy who looks like he believes he’s too good for the subway, sleek, well-dressed Wall Street type. Steve has fond memories of breaking into guys like his houses. Parker, in one of the smoothest lifts Steve’s ever seen, takes the guy’s Apple watch and his wallet, muttering a shy, bashful, “Sorry,” after.

Steve follows him, unnoticed, as he gets off the packed train into an even more crowded station. He’s not in any rush: he’s done this before. Parker fluidly dodges the crowds with the ease of a kid who grew up here, who grew up blending in without any intention of hiding.

Steve brushes up against him, without acknowledging him in the slightest and forges on, plan fulfilled. All he has to do it wait. Then, out of pure curiosity, he doubles back and follows him through a series of back alleys until he reaches the backside an apartment complex flirting with ‘decrepit’. Parker takes maybe two steps back before swinging himself up 2, 3, 4 floors via the fire escape. A broad skillset could get one very far in this world.

Up in apartment 4C, Peter Parker empties his pockets to find the Apple watch and, instead of the overstuffed wallet, to his dismay, he unpockets a business card with a name, location, and time. Well, if he’s going to be kidnapped at least the culprit has been kind enough to give their name - possibly an alias, the primary location - a relatively popular diner, and the time - dinner.

When he gets to Ditko & Lee, a man, steely-eyed and ruggedly handsome with the beard, makes eye contact with him. On the tabletop next to a half-drunk cup of coffee, there’s the wallet from the Wall Street guy. Against all better instincts, Peter approaches him.

“Who are you?” Peter asks, a name just doesn’t cut it for him.

“Friend of JJJ,” Steve replied. Peter supposes he intended to be vague and somewhat mysterious and elusive, but to Peter’s admittedly limited knowledge, Mr. Jameson doesn’t actually have that many friends. “Sit down.”

Peter sits.

Out of his jacket pocket, Steve brings out a plane ticket and places it parallel to the wallet. He keeps his hand over it. “This is a plane ticket, job offer. In or out, right now.”

“What if I say no?”

Steve shrugs. “We get someone not as good and you can go back to… petty pickpocketing, Peter Parker.”

He considers it. It could be a trap, what for, he’s not entirely sure, but he’s come across many a shady person in his life. Steve is definitely shady, but he feels like he wouldn’t screw him over. Peter thinks it’s the eyes.

He looks down at the wallet and the ticket, equidistant from him. One or the other. Take it or leave it.

Steve, as a test for more his own enjoyment than anything else, decides to signal a passing waitress for a refill. When he turns back to the table the wallet is still there, but the ticket is gone.

“That’s the best lift you’ve done yet,” Steve had, at the very least, expected to feel it. Maybe he’s losing his touch, getting soft.

“Las Vegas, huh?”

Steve shrugs. “America’s playground.”

“I didn't know you owned casinos?” Steve said rolling over to face Tony properly. It’s stupidly late, a kind of late that’s really far too much into the next day to really, feasibly be perceived as stupidly late and really, is stupidly early, early enough that the sun’s begun it’s daily rise, streaming in soft, pale dawn light through Steve’s loft’s windows. They’d stayed up the entire night, just talking, actually getting to know each other.

“Technically,” Tony said, fighting a yawn, “I don’t. A subsidiary of Stark Industries owns the bank that owns some of the casinos down there.” His hair was messy, not intentionally, black-and-white photoshoot in a workshop that’s actually very well composed soundstage, but ridiculous bedhead messy. Steve rarely found Tony not gorgeous, but right now, curled in his comforter, light casting long, lazy shadows dancing around the room, Tony seemed so vulnerable and trusting and open and he knew it was way too early for words as strong as these, but he was falling, he’s falling hard and fast and all he could think was I love you.

So instead he made a stupid joke. The type that you would only find even the slightest bit funny if you had been awake for over a day and now found yourself in a situation where time moved like sticky sweet syrup, where urgency had never bothered to be invented, where you’re so drunk on intimacy and love you can barely see what’s ahead of you, and honestly, in that moment, in the moment where nothing else exists and it feels like the world was made for you and for them and for you to be together in that moment, you can’t care that you can’t see what’s looming ahead.

“Casino’s are like… fairgrounds for adults. With greater consequences,” Steve wasn’t sure if the sentence even makes sense, but Tony giggled and he found that he couldn’t care for grammatical structure and other such follies.

“America’s playground,” Tony mumbled, far more interested in pressing feather-light kisses to Steve’s jaw, tender and loving. Maybe, Steve let himself think, let himself hope that he felt it too. Hard and fast and damned foolish.

#steve rogers x tony stark#stevetony#superhusbands#stevetony fic#stony#stony fic#superhusbands fic#steve rogers#tony stark#my fic#my writing#steve rogers/tony stark#i must say i am really vibing the rusty/danny nat/steve comparison the wordless communication between them was one of my#favourite scenes between them in the fim#the non verbal communication! the inherent closeness and being known!#anything this was meant to be posted like 10 hrs ago when i posted it on ao3 but then my laptop died kdsjfghkdfjg#*mine

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORE FG Analysis....(I think I might have a problem)

I keep rewatching and rewatching the Clover and Qrow scenes we have so far and trying to see the bromance thing or the platonic buddies thing and I just... can’t?

Look, I don’t run around with shipping goggles on if that means anything to anyone. I got through the entirety of The Lord of the Rings and the first two Hobbit movies without shipping a single couple (Martin Freeman and Richard Armitage punched me in the heart in the third Hobbit film, but that’s another tangent for another time). I wasn’t even fully on Bumblby until volume 4.

There’s just no other way to view these scenes. Things keep escalating between these two. I don’t really have a good scale for measuring romantic/sexual tension, so I’ll just try to pinpoint the moments in which things tick up a notch or two. Starting with...

The Mine Scene

The baseline here is the casual conversation that Qrow initiates. From there, here are the beats:

Conversation turns personal very quickly, thanks to Qrow opening up

Clover catches Qrow

They engage the Grimm

Qrow warns Clover

Qrow shares his semblance (again... Qrow is the one to get personal, which I find extremely telling)

Clover shares his semblance (and puts Qrow at ease)

Clover flirts (look, I’m trying to be as objective atm as possible, but the wink, the smile, the eyebrow wiggle, the full-body lean, and the lingering stare as he turns around... I’m sorry, there’s no other word for that. I challenge anyone of you to replace Qrow with a woman, show it to someone who doesn’t watch RWBY, ask what the tone of this still-shot is, and find me a single person who will tell you it’s not romantically charged. I dare you.)

Qrow stares back (this is absolutely from a myriad of emotions running through him and I will not discount that, but can we all at least admit that he seems to come out of this shock in a pretty okay place?)

They reach the main cavern and... more flirting/showing off from Clover. (The toss, the smirk, the salute, and the fancy-ass backflip which, considering he hooks Kingfisher to the ceiling and goes zipping upwards directly after this (thank you @fairgame-is-endgame) was completely unnecessary.)

The joke! How did I miss this?? Qrow doesn’t joke about their semblances for the first time at Schnee manor. He does it here! (Sorry, I couldn’t get the dialogue in there with Qrow’s eyes open.)

Clover counters with: “Hmm. No. I’d chalk that one up to talent.” (Already highlighting the difference between their attitudes regarding their semblances. For Qrow, everything bad that happens is his fault. For Clover, semblance isn’t everything. A very healthy person for Qrow to be around, no?)

The Truck Scene

Now we shift to the truck scene. Again, trying to pinpoint the beats where the romantic tension clicks up or something significant happens:

Clover initiates conversation. (Apparently, him mentioning Ruby is enough to put people on edge, but might I point out a few things? (Jesus lord, this is turning into another essay.) He brings up Ruby as “[Qrow’s] niece”, first of all. And that’s it. You know where he shifts the focus from there? On to Qrow. This is Clover’s next line in this exchange: “It’s a good thing they had someone to look up to and get them through it. Not everyone is so lucky.” Real nefarious there, guys. Way to have Master Spy Clover probe for info. Oh, don’t get me wrong. Clover is absolutely probing here but it’s for another reason entirely.)

Qrow shifts from being closed off and a little taciturn to making sure the conversation doesn’t drop. (He thanks Clover in case anyone wants me to be specific about that).

Qrow gets personal. Again. He opens up about being an alcoholic.

And the peak of this scene? Clover calls Qrow on his self-deprecating habits and tries to offer him something solid and good to hold on to. Which I and others have written about ad nauseum, to the point where repeating myself is getting annoying, so have some visual aids instead:

James’s Office

Non-verbal communication. Here, surrounded by people that both Clover and Qrow know better than they know each other at this point, and their first instinct in this moment is still to seek each other out. Enough said.

Schnee Manor

The second inside joke between them about their semblances.

Qrow flirts openly. Similar to Clover’s “You’ve had more of an effect on them than you realize” line delivery here, Qrow’s “I mean, they already invited you, didn’t they?” carries a very specific and multilayered tone. He’s playful, he’s open, he’s relaxed, he’s enjoying himself, and yes, the man is flirting. It’s in the voice, it’s in the smile, it’s in the body language. And it is absolutely in the lingering stare as Clover walks through the door (a mirror of Clover’s lingering stare in the mines, btw).

Final thoughts/speculation

Does anyone want them? You’re gonna get ‘em.

I think the fact that Qrow is the one who gets personal when he has every damn reason right now to be guarded is ridiculously significant. In the last two volumes before this, his sister tried to have him murdered, a long-trusted colleague (Lionheart) turned out to be a traitor, and Oz was revealed to be a massive liar (I love Oz, I really do, but the man screwed up). Qrow has no reason to drop his walls for just anyone so you know what this tells me? He’s interested in Clover from the beginning. Qrow’s early-stage flirting style isn’t to wink and show-off (at least not anymore), it’s to lower his guard and see how the other person responds. I think he’s gotten to the point of “if you can’t deal with my ugly shit, you won’t be getting the rest of me either”. Qrow Branwen is doing a little probing of his own and, in light of this, you could make the argument that he’s the one to open the door for their relationship to happen.

Clover’s early-stage flirting style, on the other hand, is very overt. He’s more guarded about himself personally (notice how he keeps the focus on Qrow quite a bit and even does a bit of deflecting of his own in the truck scene) but he is perfectly comfortable with making his interest known in a very straightforward and physical manner.

There are reasons for this!! Reasons deeply intertwined with character and who these men are.

Qrow sees himself as the eternal monkey wrench that no one wants. He’s finally starting to recover from this viewpoint, I think, but he’s also very aware that no matter how healthy he might get, he is always going to come with a little... extra. He has his semblance, he has his depression, and he has his alcoholism. He’s tired of secrets and he’s tired of games, and if he’s going to get involved with someone, they sure as hell better be ready to deal with all of that, because it’s not going anywhere. The solution? Put it all out there and see how the person responds. He gets the wrong response, he’s going to shut that down and move on. The right response?? He’s going to keep moving forward to see where it goes. Clover is giving him all the right responses.

As for Clover, he’s not only military but he’s also the leader of the elite Ace Ops and the man with the good-luck semblance. I know we don’t have a lot on him, but I suspect that the pressures of all that get to him quite a lot, to the point where he has major trouble being personally vulnerable for anyone. He’s probably used to having to keep it together at all times, to presenting that tightly controlled professionalism he displays with Robyn and even with Jacques Schnee to a degree. He’s used to everyone else relying on him, including James. This means that even in the presence of mutual interest, he’s going to flirt in ways that are emotionally safe, at least at first.

The balance inherent in this is so unbelievably beautiful. And, I’m starting to realize, a complete subversion of early expectations.

Qrow isn’t the one who has to learn to open up. He’s already doing that. What he will have to do is learn to accept someone (outside of his nieces) loving him without strings attached. He’ll have to learn to trust that Clover (and by extension their relationship) isn’t going anywhere, even if/when things get bad. Clover can be the one who stays.

Clover, on the other hand, is the one who is going to have to learn to open up. He’s going to have to learn how to return that emotional vulnerability that Qrow has already given him, and he’s going to have to learn that Qrow can be the safe place where all that confidence and self-control can finally drop. Clover might have to be the unshakeable support structure for everyone else in his life, but Qrow can be the one place where he can lean and just breathe.

#fair game#qrow branwen#clover ebi#fairgame#lucky charms#luckbirds#qrover#rwby#rwby7#if this doesn't happen it will be the missed opportunity of the millineum#let me tell you what#another essay#i can't help myself#i start with one thought and my brain tosses out fifty more that are relevant#probably the analysis i'm most proud of so far

561 notes

·

View notes

Text

warning: this is going to be a long post. transphobia and bigotry under the cut

I am posting this rebuttal of a person who got (hilariously) angry at someone who Does Not Care (me) and wrote an entire-ass essay on this post because apparently this is how I spend my time. Defending my identity which does not need to be defended because it is immutable from transphobic trolls who won’t even see it cause they’re blocked from this account.

Anyway. Be careful looking under the cut.

TERFs, gender-crits, radical feminists, transmeds, nb-exclus, anti-mogai, and anyone else whose ideology promotes transphobia and/or trans erasure, please kindly do not fucking touch this post. I am not kidding when I say that I will report you all to tumblr for hate speech if it takes me all fucking night.

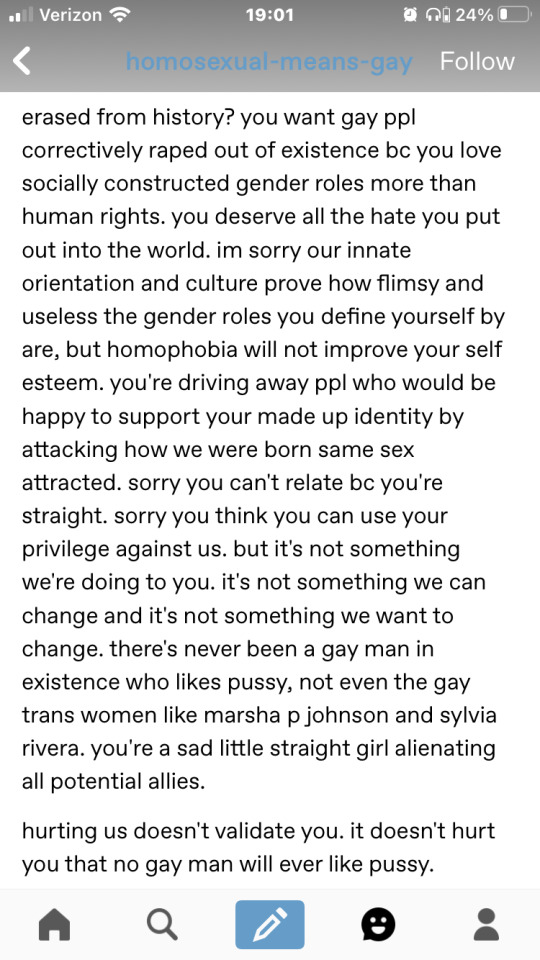

Image Description

Two screenshots of a reblog from tumblr user homosexual-means-gay. The post reads:

please tell me how literally every single gay man being repulsed by ppl with vaginas hurts you! tell us why it’s a problem gay ppl aren’t attracted to the opposite sex like straight and bi ppl are!

homosexuality isn’t a political movement it’s a regular natural innate sexuality. gay men aren’t attracted to biological females and it hurts gay ppl when you side with conversion therapists and it hurts bisexual ppl who actually are attracted to both sexes when you erase them for your homophobic agenda. you’re not a victim. you’re happy to eliminate homosexuality from existence as long as you’re able to reinforce heteronormative gender roles the gay community has always opposed. your bigotry harms trans homosexuals too, not that you transhets care about the gay trans ppl either.

erased from history? you want gay ppl correctively raped out of existence bc you love socially constructed gender roles more than human rights. you deserve all the hate you put out into the world. im sorry our innate orientation and culture prove how flimsy and useless the gender roles you define yourself by are, but homophobia will not improve your self esteem. you’re driving away ppl who would be happy to support your made up identity by attacking how we were born same sex attracted. sorry you can’t relate bc you’re straight. sorry you think you can use your privilege against us. but it’s not something we’re doing to you. it’s not something we can change and it’s not something we want to change. there’s never been a gay man in existence who likes pussy, not even the gay trans women like marsha p johnson and sylvia rivera. you’re a sad little straight girl alienating all potential allies.

hurting us doesn’t validate you. it doesn’t hurt you that no gay man will ever like pussy.

End ID

(If someone wants to do a better ID that’s fine, I just wanted to put everyone on an equal playing field when it comes to understanding the content of this post.)

I’m going to go line-by-line and refute every single bullshit thing this person said.

> please tell me how literally every single gay man being repulsed by ppl with vaginas hurts you!

factoid actually just statistical error. TERF Tommy, who has committed multiple transphobic hate crimes, is an outlier and should not have been counted. I know many cis gay men who are attracted to trans men because they are MEN, not because of the genitalia they have. And I know you want to say ‘that makes them bi’, but no, it doesn’t. You want to accuse me of homophobia? Telling another gay person that their identity is invalid just because they express it in a different way than you do is literal homophobia.

> tell us why it’s a problem gay ppl aren’t attracted to the opposite sex like straight and bi ppl are!

because... some are? And you don’t speak for the entire gay community? Especially not the other side of it, for the opposite binary gender than yours.

> homosexuality isn’t a political movement it’s a regular natural innate sexuality.

and transness isn’t a political movement either, it is a regular natural and innate gender identity. You know that gender identity is inherent, right? When people say ‘gender is a social construct’ all that means is that it is not a natural thing. Humans created the concept of gender and assigned value to it based on what we could perceive as a means of giving order to the world around us. That doesn’t mean that it isn’t important and it doesn’t mean that there aren’t parts of it that are inherent to individuals.

> gay men aren’t attracted to biological females and it hurts gay ppl when you side with conversion therapists and it hurts bisexual ppl who actually are attracted to both sexes when you erase them for your homophobic agenda.

I’m sorry this is literally incoherent. To reiterate: some gay men ARE attracted to assigned females. Yes, siding with conversion therapists hurts gay people. No, I am not siding with conversion therapists. I have never once stated -- in fact, the entire point of my post was the opposite of this -- that anyone should EVER have sexual interactions with a person they don’t want to. Even if the reason for that is because they have a genital preference, which is NOT the same thing as a sexuality.

(I know I’ve been over this before but here it is again. A sexuality is a measure of what GENDER/S you want to have sex with. A genital preference is a measure of what genitalia you are willing to get all up close and personal with. Both are innate, one can be manipulated. They are not the same thing.)

Hurting bisexual people... hey, fellow bis, am I hurting you by *checks notes* existing in time and space?

> you’re not a victim. you’re happy to eliminate homosexuality from existence as long as you’re able to reinforce heteronormative gender roles the gay community has always opposed.

I am literally A GAY PERSON. Even by YOUR MEASURE I am a victim. And I do NOT want to eliminate homosexuality, I just want people to acknowledge that language evolves and definitions can change as our society does. Also, have you ever met a trans person in real life? Because like 80% of all the trans people I’ve ever known have been gender non-conforming, so like. That invalidates that point. The trans community opposes gender roles as well.

> your bigotry harms trans homosexuals too, not that you transhets care about the gay trans ppl either.

Please point to where it says I’m straight. Please. I want to see it.

> erased from history? you want gay ppl correctively raped out of existence bc you love socially constructed gender roles more than human rights.

At this point I’m just repeating myself. Please see the above points for rebuttal.

> you deserve all the hate you put out into the world. im sorry our innate orientation and culture prove how flimsy and useless the gender roles you define yourself by are, but homophobia will not improve your self esteem.

Says the person berating a minor for *flips notecard over* agreeing with them that people shouldn’t be forced into sex. I’m sorry that you’re so hurt and angry that you have to push your pain onto other people just to feel better. I genuinely am. It makes me so sad to see how much some people are hurting. But I won’t just sit and take this kind of verbal abuse. I don’t deserve it, quite frankly.

> you’re driving away ppl who would be happy to support your made up identity by attacking how we were born same sex attracted.

I doubt anyone calling it a made-up identity wants to actually support me. Next.

> sorry you can’t relate bc you’re straight. sorry you think you can use your privilege against us. but it’s not something we’re doing to you. it’s not something we can change and it’s not something we want to change.

Again. I am not straight. I do not have any straight privilege to use against anyone. Even if I was cis I still wouldn’t be straight because I’m aroace and attracted to anyone and everyone. My gender identity isn’t something that I can change, either. And even if I couldn’t, I wouldn’t want to. I love being a man, and I love being a trans man.

> there’s never been a gay man in existence who likes pussy, not even the gay trans women like marsha p johnson and sylvia rivera.

I’m sorry, WHAT. Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera can’t be both gay men and trans lesbians. Which one are they? You gotta pick, babe.

> you’re a sad little straight girl alienating all potential allies. hurting us doesn’t validate you. it doesn’t hurt you that no gay man will ever like pussy.

So am I a transhet or am I a straight girl? Also I’m not sad, I’m quite happy with where I’m at in my life. I do not feel validated by hurting anyone, because I don’t enjoy pain. I’m not masochistic or emotionless, I am in fact hyperempathetic due to my autism, and I don’t like it when anyone is hurt. This can be evidenced by this post here where I wish well upon a group of people who have directly hatecrimed me in the past.

I will repeat that. I have literal trauma from physical violence as a result of the actions of this group of people, and I am still wishing them good things.

Nor does it hurt me that ‘no gay man will ever like [AFAB genitalia]’ because this isn’t even a true statement. As I have mentioned previously, I know personally multiple gay men who are attracted to trans men. And reader, please note the fact that this person uses a slang term, a deliberately vulgar one, where in my original post I used the medical term ‘vagina’.

Hope this clears some things up.

TERFs, gender-crits, radical feminists, transmeds, nb-exclus, anti-mogai, and anyone else whose ideology promotes transphobia and/or trans erasure, please kindly STILL do not clown on this post. I am once again not kidding when I say that I will report you all to tumblr for hate speech if it takes me all fucking night.

#terf#anti-terf#terfs don't touch#trans#transgender#transphobia#tw transphobia#tw rape mention#tw homophobia#tw homophobia mention#tw misogyny#tw terf#long post#discourse#genital preference#tw genitals#tw vagina#tw penis#tw male genitals#tw female genitals#marsha p johnson#sylvia rivera#stonewall

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

credit (x)

&. BASICS

Full Name: Lucy Vivian O’neal Lynx

Nicknames: predator, Donna, beast

Age: 125 years old

Sexuality: bisexual

Date of Birth: November 18th 1895

Place of Birth: Miami. Florida, USA

Gender & Species: cis woman & (earth) sprite

Current Location: Terra, Concordia

&. MORE BASIC INFO

Languages: English, Spanish, Russian

Religion: atheist

Education: graduated from high school and has been taught on the streets ever since

Occupation: Assassin/Donna of the O’Neal crime family

Drinks, Smokes, & Drugs: yes to drinks and drugs, no to smoking.

&. PERSONALITY

Zodiac Sign: Scorpio -- Scorpio is the eighth sign of the zodiac, and the Eighth House is all about sex, death, and the cycle of regeneration. With their penchant for all things spooky and magical, female Scorpios are natural Queens of the Underworld, and thus usually not ones to shy away from the more intense or heavy characteristics of life. This sign gets a bad rap from most astrologers for being “too much,” overly dark, or even downright evil. This stems more from modern western culture’s inherent discomfort with discomfort with discussing the Pluto-ruled subjects of sex and death (typically not your general everyday dinner-table conversation). Reviled as a Scorpion woman can be, not many can deny her magnetic personality and the aura of mystery, magic, and sensuality that she wears around her like a cloak. This is not a woman who tolerates surface-level interactions easily. She prefers to give her attention to those willing to go deep with her. With a Scorpio’s electric gaze powerfully focused on you, it’s easy to feel like a bug pinned under glass, examined by a curious scientist determined to learn everything there is to know. Scorpios rule over the occult sciences, and the true meaning of the word “occult” is “hidden” – hence, the Scorpionic tendency toward secrecy and inscrutability. Only the most determined (and respectful) will be granted permission to explore the secret caverns within the heart of a Scorpio woman.

MBTI: ISTP -- ISTPs are equally difficult to understand in their need for personal space, which in turn has an impact on their relationships with others. They need to be able to "spread out"--both physically and psychologically--which generally implies encroaching to some degree on others, especially if they decide that something of someone else's is going to become their next project. (They are generally quite comfortable, however, with being treated the same way they treat others--at least in this respect.) But because they need such a lot of flexibility to be as spontaneous as they feel they must be, they tend to become as inflexible as the most rigid J when someone seems to be threatening their lifestyle (although they usually respond with a classic SP rage which is yet another vivid contrast to their "dormant," impassive, detached mode). These territorial considerations are usually critical in relationships with ISTPs; communication also tends to be a key issue, since they generally express themselves non-verbally. When they do actually verbalize, ISTPs are masters of the one-liner, often showing flashes of humor in the most tense situations; this can result in their being seen as thick-skinned or tasteless.

Likes: being outdoors, having her way, gore, breaking rules, power, the woods, Terra in general, inspiring fear into others, day-drinking, confidence

Dislikes: mundane interactions (for the most part, she warms up to it from time to time), extreme heat, feeling helpless or unheard, crowded places

Bad Habits: her jaw is tensed most of the time and if she talks Lynx has a habit of showing off her sharp teeth to assert dominance. She also just.. stares a lot.

Secret Talent: (not so secret) killing, negotiating, sensuality

Hobbies: hunting for sport, scheming, watching others from afar, getting to know the newbies and possibly teach them, talking about the old days

Fears: being dominated, being forced into the spotlight for too long, Terra throwing her out, losing her powers

Five Positive Traits: confident, challenging, playful, tough, dominant

Five Negative Traits: insensitive, predatory, cantankerous, obsessive, hedonistic

Other Mentionable Details: has fangs due to her nature and abilities (ref. picture) as well as sharp, claw like nails (ref. picture), almost always wears dark, unassuming colors

&. APPEARANCE

Tattoos: none

Piercings: earlobes

Reference Picture: ref picture

&. FAMILY INFORMATION

Parent Names: William O’Neal (former don, drug dealer) & Meredith O’Neal (socialite)

Parent Relationship: Lynx never really cared for her parents, especially not their authoritarian ways. She killed her own father, so there’s really nothing to be said here other than she didn’t care about them and wanted them gone.

Sibling Names: she has no siblings

Sibling Relationship: --

Other Relevant Relative: None at the moment, she’s a loner.

Children: --

Pets: --

&. BIOGRAPHY

( tw: death, murder, drugs, violence )

She grew up in the wildest of neighborhoods in the wildest time imaginable. Miami was one of the sunniest, loveliest cities in Florida if not the entire United States. Lynx, formerly known as Lucy O’Neal, confronted her surroundings with the reality that she wasn’t too eager to follow rules. As the daughter of a prestigious drug lord, Lynx grew up sheltered, yet surrounded by crime. A spoiled brat, as some liked to call her, always able to command those around her with ease. The constantly increasing demand for drugs had helped the O’Neals enter Miami’s elite. With drugs being widely accepted and legal at that time, Lynx’ father expanded his business to more shady dealings like fraud and bribery of politicians. The O’Neals had no real reputation. Like a shadow in an otherwise sunny city they remained near celebrities of all walks of life while simultaneously waiting for them to open all the doors for them. Lynx, however, didn’t care to be subtle. Within her school years Lynx had developed an aptitude for breaking the law and getting away with it, either through her father or intimidation. Intimidation and aggressiveness she’d learned amongst the ranks of her father, no doubt. Thus began her reign of power and chaos — the reign of a girl boxing her way through etiquette and rules.

Others described her as reckless, selfish, careless, wild — a lot of descriptive words for someone who never wanted to be categorized or labelled. Lynx desired to be her own master without restraints. She was nineteen when the United States prohibited domestic distribution of drugs, weakening her father in the process. She’d been running her own little empire in secret, consisting of assassinations and intimidation tactics. While her father knew about her business and certainly used her talents from time to time, Lynx distanced herself from her father as much as possible. In her early years Lynx began with using poisons, but quickly decided for a more direct and sadistic approach. People always commented on finding fun in work, so she did. Call it irreproachable customer service in which the boss did all the dirty work. Gladly. Lynx fully focused on work and, as the war for customers and booze increased after prohibition in the early 1920s, she got to target someone close to her heart. Her father had dominated the Miami crime scene for decades, forcing others into submission — and Lynx saw an opportunity to pull ahead, to play by her (non-existent) rules. The next morning Lynx called her father and customer to a meeting under the guise of killing one as mandated by the other. With two shots being fired into the round, Lynx left behind whatever shred of rules they had set in place. From that an even larger empire arose. Her targets became her prey after all rules had been abolished. She ruled over Miami all on her own, leaving claw and bite marks everywhere she went, recklessly ripping into every poor soul who dared to threaten or annoy her.

Lynx oftentimes decided to stalk and expose her prey, no, let them expose themselves before she got rid of them. She pulled the strings, watched them squirm, satisfying her sadistic tendencies in the best way possible: up close, sometimes even while dragging her prey along to display them. While other women her age enjoyed being hunted and hit on, Lynx loved to hunt and hit people, having fun in the only way she’d ever known: with violence, dominance and cunning. After Miami had been hit by a hurricane in 1926, Lynx decided to expand clientele after she’d already made numerous headlines back home, warning of an assassin roaming the otherwise sunny streets of Miami. A killer they couldn’t identify, but given the strength displayed and the lack of attention for detail the press was quickly to pinpoint the assassin as being male, possibly large and in his 30s. While this would’ve been an undoubtedly good disguise, Lynx loathed the idea of giving them even more fodder for their yellow press. She boarded the Horizon to assassinate her last target before eventually expanding all the way up to Chicago or even New York City. That’d never happen — and cats weren’t really known to like water that much.

Lynx awoke in a strange land, surrounded by a sense of belonging despite everything being so foreign. The sea took her prey, her former home and washed her ashore into a new world, everything she’d once hoped for. Concordia turned out to be a beacon for powerful beings, a birthplace for the wild and creators. Creators of various kinds — chaos or peace, death or life — Lynx joined Terra, accepted her new name upon being reborn, and practically planted herself into its social structure. For the first time Lynx tolerated some rules. She found shelter in one of the caves, though Lynx spent most of her time training with her new powers and causing random battles to test them out. Once the hunt and battles were finished Lynx returned to her cave; a feral predator loving solitude, rarely seen, but if so she was one of the most threatening presence safe for the monarchs and older sprites. The years, however, began to bore her after a while. Without fresh meat and the monarchs back and forth the days felt much longer and all her mice weren’t that interesting anymore, either. The truce opened Concordia, a change Lynx welcomed with open arms. Fresh, innocent meat, ready to be corrupted, turned and molded. Unlike her human years Lynx decided to recruit one or two people if given the chance, to raise, teach and protect a new generation of sprites -- in the only way she knew: with fangs, claws and ferocity.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LANGUAGE PRISON

A close friend of mine recently came out publicly as identifying as gender queer/non-binary. For those of you who might not be familiar with the terminology, non-binary refers to those who don’t subscribe entirely to a traditional male or female gender identity. This person was assigned male at birth (amab is the acronym), but find that they feel more comfortable expressing and embodying a feminine identity. I suppose trans is another good term, although it doesn’t mean quite the same thing as non-binary. If you’re confused I’d give it a google - there are lots of people out there who are more equipped to properly explain the terminology than I am. I’m a straight cis girl through and through, so I don’t really feel qualified to make any solid definitions of language in this realm. I have no idea what feeling that way might be like, so it’s my job to just listen.

This friend came over the other day and we got to talking about their coming out experience. Prior to them coming out publicly (via Facebook), I had really no idea that this identity was a part of them. I’d always known and referred to them as male, but they said this is something they’ve sort of known for a few years, and recently become increasingly sure of. My boyfriend Ryan, who is generally more perceptive and observant than I am, told me that he wasn’t surprised by our friend coming out - he had a sense that this was something they were feeling.

Anyways, our conversation got me thinking about language. Our friend (I’m reluctant to use their name for anonymity’s sake on my public blog) said that the main deterrent they felt from coming out was being unsure of the language to use. Language is obviously universally relevant, but it’s particularly important when it comes to gender identity. I’m talkin pronouns and labels. You saw in my first paragraph that language can be tricky with a topic like this, because people ascribe different meanings or connotations to different terms. Some people feel comfortable being “labeled” as one thing, others do not. Our friend expressed in their (quite impressively eloquent) Facebook post that for now, they were okay with people referring to them with any pronouns, be it he, she, or they, as long as it’s meant with respect. I’m gonna default to using they/them/their because I think it’s the most neutral, and I want to respect their wishes as much as possible while they’re learning how to be comfortable expressing their identity in the public realm. But it’s tricky. It can be really hard - like I said, I’ve known this person as “he” for so long, that my brain sort of defaults to that when describing them.

Using the wrong pronoun can be hurtful for someone, especially someone who’s trying to break out of their assigned biological label or exist outside of a binary. It’s often seen as being intentionally disrespectful, and sometimes it is. But a lot of the time it’s just our brains being stuck in the societal gender binary, or a force of habit. But language is powerful, and it’s malleable. You can make it mean different things, and you can change the way you use it. I’ve found that conversationally, it’s not really that difficult to avoid using pronouns altogether, and just use someone’s name instead. That’s what I would be doing in this post if I wasn’t wary of keeping their identity safe.

Matt mentioned something in our conversation with Boris about how language can be restrictive. It inherently holds powerful meaning because it’s the vehicle we most commonly use for expression, and words have history. For people experiencing a largely earth-shattering transformation or realization, language can be incredibly sensitive. Our friend said they still weren’t really sure of the language they wanted to use to describe their feminine identity, but that hopefully one day it would come. I think that’s really fascinating, that you can know something in your brain, but not be able to express it verbally. I think I experience that a lot with different ideas or emotions. It’s like the language doesn’t exist, or isn’t sufficient to describe what I’m trying to say.

Communication is fascinating.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Tsunami COVID-19, Beware the Undertow

The crushing power of a tsunami can destroy almost anything we can build, including entire communities. And as the wave of destruction retreats, as it must always do, the undertow can drag what is left of our world out to sea, forever lost to the eternal black deep. As these waves of COVID-19 surge around the globe, we need to take heed of the ensuing undertow. It holds the power to strip us of a core evolutionary need that has allowed us to thrive on this planet. Our need to connect, bond and care for each other.

From our caveman days we were more successful in cooperative packs. Families and allies, banded together were more effective in hunting, breeding and protecting themselves against danger.

Millenniums of this success is bred into our genes. Most recent generations have created powerful social structures predicated on this need, we marry, have kids together, reside in purpose-built towns and cities, encourage our children to develop socially and send them off to schools where they learn to cooperate and operate as a team. We rely on connection to be successful and to thrive.

And along comes COVID-19, a tsunami that threatens to tear apart our communities.

The only tools we have in our arsenal right now to prevent our world from being swept away by this virus are hygiene and distancing. We are being told, lectured and even threatened to accept that to get close is dangerous, even deadly. Gatherings are being quickly outlawed, whether to march for social justice, get married or bury our dead. The language of our offense, distancing, isolation, quarantine seem to tell us and our young and most formative generation — getting close and connecting is a dangerous thing. This is the undertow. And it is a current that can drag us away from the very essence of what makes us successful as humans.

Hope…

At the same time, there are beautiful and powerful signs of hope. Forced to remain physically distant people and communities are finding unique, creative and fun ways to come together. We can give thanks for the digital age that has provided the tools to be able to have a heart to heart, face-to-face conversation with a loved one on the other side of the planet. We are discovering and promoting virtual dinner parties, online communities, and the capacity to set-up offices and workgroups from home. Yet these digital connections cannot fully replace what we get from the in-person, face-to-face experience. We rely deeply on non-verbal communication including body language and micro-expressions. But still, there are reasons for hope as these tools, our creativity and our biological/psychological imperative to come together empowers us dig in, and hold fast against the undertow.

It’s not just you, it’s us…

The effects of long-term social isolating are not known. But we do know it is contrary to our very nature. This need is encoded in our DNA and is linked to a vast array of physical and mental health problems: depression, dementia, heart disease and even death. A 2018 Danish study concluded that objective social isolation was associated with a 60–70% increased all-cause mortality. Before the recent dictums to distance and isolate to ‘level the curve’ (minimizing the spread of the virus), Statistics Canada reported over one in five Canadians reported feeling lonely, and this number skyrockets when we poll seniors. The epidemic is so bad the UK government appointed a new minister for loneliness!

Connection not only cures loneliness but it buffers the effect of stress. Stress well-modulated provides us with temporary motivation and strength. However unchecked, stress like loneliness has long been known to impact both mental and physical health.

Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity or CTRA, is a gene expression we find in human immune cells which responds to chronic stress by increasing the production of inflammatory proteins — it is intended as a short-lived acute inflammation to adapt and increase the immune response to fight an injury or infection. Long-lived it becomes a threat and meanwhile, CTRA is downregulating (slowing down) our anti-body genes that decrease our ability to fight a virus. Loneliness, fed by a lack of connection only worsens this response, which in turn harms health and furthers isolation. It’s a system that can weaken our ability to resist the undertow and being swept into the dark abyss.

All of this adds up to just case for a dire warning. We need to be vigilant about what we are learning, or not, from this necessary loss of connection. History has taught us the nefarious power of capitalizing on individual and communal weaknesses, utilizing them to further our disconnection and thus divide and conquer.

Globalism breaks down borders and allows trade and life to move freely across borders. Anti-globalism existed before Covid-19 and is a tried and powerful tool of governments seeking to gain and hold power. The politics of fear and blame have levelled democracies and birthed holocausts. Shut down borders. Build walls. The call to fear, isolate, disconnect from our neighbours and blame the other are the makers of despots and dictators. It frees the individual and their community of responsibility for the inherent challenges of community. What is wrong is ‘their fault’ not ours, and governments and leaders can rise to power on the backs of their chosen targets — usually the weak and most vulnerable.

The dangerous irony is that to beat COVID-19 we must shut down borders and build walls.

Left unnoticed and unchecked the undertow can and will destroy our communities and nations.

There is a solution…

Our well-being and survival are intrinsically linked to our connections with others. Our biology mandates connection…stress, well-managed, boosts our immune systems. It can encourage us to seek and provide support. CTRA is downregulated by positive altruistic connections — the happiness found in caring for others. (Fascinatingly, a study in 2013 at the University of Florida found in hedonistic happiness has the opposite, negative, impact on this gene expression.) In short caring for others improves out health.

Anyone who has flown knows the well-rehearsed safety briefing that tells you, “In an emergency, put your own oxygen mask on first.” It is not an act of selfishness — you need to be conscious to help others.

I live a life walking the fine lines between being a psychotherapist, deeply rooted in the science of neuropsychology, and a spiritual director, who is deeply rooted in academic Christian theology and very wary of organized religion.

I believe in hope, and I know grace. I’m fascinated by the intersections of science, theology and the creation of reality.

I know each of us has a history, and very few of us escape burdens of trauma and oppression. We are all wounded and suffer in some way. Isolation and distancing are a potential mental health crisis in the making and can serve to further our trauma. Some of us suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Our life history seems to be a life-sentence, not a life-lesson. We struggle to shift this paradigm. Communally we may be moving towards a new systemic PTSO, (Post-traumatic Stress Order).

The crisis starts with the individual and like this virus, it can spread through our communities and infect us globally. No community or leader is immune. Without great intention by each of us this virus will win. The tsunami will crush us, and the undertow will drag what is left out to sea.

But there is hope. And it is harder to access for some than others. We must come together. We must find connections in the isolation and build walls that break the tsunami, stop the virus, and still let our compassion flow freely.

It is too easy for me to tell you to wash your hands, stay home, breathe deep, meditate, eat well, get your sleep, and use technology to build connection — good advice, yet these are only options for those of us who have enough privilege to do so.

So many won’t because they can’t. It’s simply not in reach. They don’t have freshwater, a home, a bed to sleep in, or technology. Their trauma runs deep, and should they close their eyes for but a moment they see flashes of terror, not moments of peace. In varying degrees, we are all weak, vulnerable and incapable.

But there is grace. Grace is our ability to regenerate and sanctify, to inspire virtuous impulses, and to impart strength to endure and press past temptation. For some grace is of divine inspiration, for others is simply an inherent pillar of humanity. Through grace, we access the biology of connection and the power stress gives us to put on our own oxygen mask first, giving us the strength to care for others. Through grace we find the compassion to carry those who can’t carry themselves.

We can do this. We have the capacity to survive. It is found in connection. It is in both heeding the wisdom of experts and those who have walked the walk. It is being the hands and feet of those who can’t, and when we can’t be those hands and feet, allowing grace to flow as others put on our oxygen mask for us.

So yes, if you can, wash your hands, stay home, breathe deep, meditate, eat well, get your sleep, and use technology to build connection. And if you can’t know through grace you can find connection and community that will bring the compassion that heals.

Todd Kaufman, MDiv, BFA, BA, RP

Toronto, CANADA

0 notes

Text

“A Clockwork Messiah” (Essay by High Preist Peter H Gilmore)

Mel Gibson’s film, “The Passion of The Christ” is a rather tedious exercise in graphic brutality and strained reaction shots, with a generous dollop of anti-Semitism and a soupçon of anti-paganism thrown in for good measure. In a clever fusion, Gibson melds the aesthetic sensibility of the plague-ridden late Middle Ages with the over-the-top mayhem of a contemporary shoot-’em-up video game to craft an ultra-violent “religious” film fit for today’s box office.

His Satan, an omnipresent, androgynous, deep-voiced figure wrapped in a cloak, is perhaps inspired by medieval depictions of “death triumphant”: a sexless, worm-riddled avatar of corruption. Satan at one point parodies images of the Madonna and Child by hefting a bloated demonic infant. It certainly suits the aesthetic choices made by the director, but is not congruent with our symbol of Satan as heroic individualist.

It seems pretentious to have the actors speak in Latin and Aramaic, but it’s all part of the director’s attempt to create a “you are there” sensibility in the viewer’s mind. In fact, the gospels which served as the source for this tale were crafted long after the time of the alleged events by people who could not have been present. Gibson is trying to sell the audience a myth by presenting it as if it were as authentic as a historically-accurate recreation of a Civil War battle. Additionally, the dialogue is often not even subtitled, particularly when Yeshua is being abused by the Romans, so those unfamiliar with Latin will miss the precise meaning of the epithets being showered upon the bruised Nazarene. Translating Latin curse words is a no-no; rubbing your nose in graphic violence is A-OK!

Gibson is trying to sell the audience a myth by presenting it as a historically-accurate recreation

of a Civil War battle.”

Like the Dark Age passion plays, the film focuses solely on the beating and crucifixion of Yeshua, and Gibson wastes no time in presenting the culprits. With a full-moonlit night to set a horror film context, Judas goes to the Sanhedrin and betrays his mentor for the traditional 30 pieces of silver. The Hebrew priests are depicted as heavyset, overdressed, and utterly dedicated to the murder of Yeshua, whom they consider a rival to their spiritual authority. They send their military lackeys, also Jews, to “begin the beguine” by putting a beating on Yeshua and his hippie-like followers in the garden of Gethsemane.

Contrast this image with the later depiction of the pragmatic figure of Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of this far-flung cesspit of a province filled with religious maniacs. He does not see why Yeshua should be killed, and only orders the already-battered and obviously meshuggah fellow to be flogged in hopes of appeasing the bloodthirsty Jewish ruling class. Now do you wonder why some folks might contend that this film has a certain slant?

Of course, the fellows who administer the punishment are a bunch of rowdy pagan brutes, dull-witted frat-boy-turned-corrections-officer types, who go too far. Here follows the most brutal whipping ever filmed. Yeshua, rather buff for a desert-dwelling prophet, is first caned until he is beaten down, his back deeply marked in the closely-depicted process. But he stands again, which prompts the sadistic Romans to choose more damaging implements, to wit, leather-thonged flails woven with metal beads. These are used with utmost effort and we are treated to close-up views of gobbets of flesh being torn from Yeshua’s body. He is nearly beaten to death, finally lying on the cobblestones in a literal sea of blood, and Greg Cannom—who is known for having done make-up effects for horror films—has wrought a body suit that lovingly details the ribs showing through the flayed flesh. Splatter fans may find this of interest. It certainly goes way beyond anything that could remotely be considered erotic sado-masochism into the realm of disgusting atrocity.

You all know the rest of the tale, but Gibson has added some personal touches.

Perhaps [Judas] should be considered the patron saint

of thankless tasks?”

We are treated to a number of flashbacks, one of which depicts Yeshua the carpenter as having crafted a table which is too tall for local traditions. When his mother remarks upon it, he says he’ll make chairs to match. So, not only is he the Messiah, but he’s a brilliant innovator of furniture design! I wonder if that bit was in one of the non-canonical gospels?

When Yeshua stumbles the second time on the way to his place of execution, his mother recalls in flashback a scene wherein little toddler Yeshua falls and she rushes to comfort him. Not particularly subtle.

We need not deal in detail with the inherent contradictions in the tale. However, it is interesting to note that, as shown in this film, Yeshua knows at the “final nosh” that he is going to be executed (as his deity-father wills), and he knows that Judas will betray him to set the deal in motion. But then Yeshua seems angered at Judas who is only doing what his God has ordained him to do. You’d think Judas, who supposedly loved and revered his mentor and thus felt great pain at being the one who had to do this, might actually be considered a hero by Christians for having to be placed in such a painful situation that he is driven to suicide. Perhaps he should be considered the patron saint of thankless tasks? Such an odd cult is Christianity.

Also of interest is the scene wherein the two criminals crucified along with Yeshua express their take on the situation. One believes in him as a holy man, the other challenges this dying Messiah to exercise his powers to get them the hell out of there. The doubter is punished when a raven arrives and pecks his eye out. Seems a tad bitchy of God, wouldn’t you say? The Romans who savaged Yeshua are unscathed, while somebody under great personal duress who presents a verbal challenge gets mutilated. Anyone else think this is a strange hierarchy of values? And of course, the Almighty lets his son be abused and saves the vengeful earthquake as an after-death climactic scattershot retribution. Poor timing? Why wreak havoc upon those who are doing what you wanted them to do, Jew and pagan alike? Seeking sense in this myth system has been fruitless for millennia.

When Longinus’ spear pierces the side of Yeshua to make certain he is dead, it releases such a fountain of blood and body fluids, that one must recall “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” to find a similarly overdone gout. Several people ecstatically bathe under this torrent; the director celebrates this revolting behavior.

The penultimate pieta image of Mary embracing the shattered body of her dead son was one of defeat and resignation. Indeed, that is a human touch, and would be the natural reaction to witnessing such events. There was no triumph and resistance and looking ahead to resurrection—only pain, degradation, and intense suffering. And since the director clearly blames this death on the Jewish community leaders, it wouldn’t surprise me that Christians who hold this myth dear might find such imagery spawning vengeful feelings toward those depicted as being responsible—as they also forget that their own deity is supposedly the ultimate author of the scenario. We all know that throughout history, Christianity, when linked up with the state, did turn implements of torture, similar to those used on Yeshua in this film, against anyone who would not buy into their sick faith, as well as against those “heretics” prone to hair-splitting of doctrine and dogma. They’ve had plenty of “tit-for-tat” over the past two thousand years, so one might reasonably expect they should now be sated.

This film takes abuse, torture and execution to pornographic excess and it is not suitable for viewing by children. If a film depicted any other individual—fictional or otherwise—being put through such a harrowing experience, I would think it likely that it would have been rated X, or banned outright as being obscene, perhaps even if it had been Hitler cast as the victim. That such generally objectionable imagery can be made palatable to a broad audience by placing it in a religious context is food for thought.

With that in mind, I could speculate that innovative pornographers might find this to be the time to introduce a new Messiah. A “spiritual” young lady (“hot” by contemporary standards, with her legal age statement properly on file), a true daughter of God, receives a vision that Mankind is so sinful that the death of Yeshua just wasn’t enough. She claims that God has inspired her to subject herself to the ultimate degradation of the world’s biggest “gang-bang,” so that Mankind’s multitudinous sins will be expiated through her selfless act as a receptacle for the jism of thousands of “fallen” men. They too will be saved through contact with this prostitute-paraclete. If such were realized with enough piety, perhaps in time this myth could be the foundation for a new religion? Is it any less ridiculous or obscene than what Gibson has portrayed?

It seems that many are forgetting that the imagery of Gibson’s film has been previously approached with the same glee. Recall the sequence in Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” wherein violent delinquent Alexander De Lodge finally reads the “Holy Scriptures” while incarcerated and imagines himself as a Roman, lustily flogging Yeshua on the way to Golgotha. Gibson has made little Alex’s wet-dream into a feature-length snore/gore fest. Perhaps one day, this director—much as another one who uses savior images but casts extraterrestrials in such roles—will feel the need to retouch his work. He might see that he gave torture too much of the center stage, and so he will create a revised “special edition.” In this, the brief image of resurrection will be extended into a view of Yeshua and the believer-thief entering into a brightly-lit heavenly kingdom, thronged with angels, much as Spielberg’s Paul Neary entered the mother ship in the revamped “CE3K.” Or perhaps the impulses that fueled “Braveheart” will come to fore and he’ll depict the risen Yeshua harrowing Hell in a flashy action sequence.

Your present humble narrator leaves you now with the proposal that this dull work is indeed an embodiment of the essence of Christianity. Witness the concentration on pain and suffering as the central value, joined with the idea of a father-deity torturing his child to death and this being celebrated as a positive image. We Satanists find it accurate to the spirit of Saul of Tarsus (aka “Saint Paul”), the true creator of Christianity, and we reject all of this as a vile creed, unfit for anyone who loves life and seeks joy in the world. I’ve always thought it a perversion to link the word “passion” to these mythical events of hideous torture, and this film has more than confirmed my opinion, as well as my wariness of those who do feel that this is a proper use for the word. Such twisted folk cannot be trusted.

#satanist#the church of satan#satanism#satan#lucifer#leviathan#belial#peggynadramia#peter h gilmore#antonlavey

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do people maintain deeply held moral identities in a seemingly immoral social environment? Cultural sociologists and social psychol- ogists have focused on how individuals cope with contexts that make acting on moral motivations difficult by building supportive networks and embedding themselves in communities of like-minded people. In this article, however, the author argues that actors can achieve a moral “sense of one’s place” through a habitus that leverages the material di- mensions of place itself. In particular, he shows how one community of radical environmental activists make affirming moral identities cen- tered on living “naturally” seem like “second nature,” even in a seem- ingly unnatural and immoral urban environment, by reconfiguring their physical world. The author shows how nonhuman objects serve as proofs of moral labor, markers of moral boundaries, and reminders of moral values, playing both a facilitating and constraining role in moral life.

INTRODUCTION