#religion of gaul

Text

The gods of Gaul: Cernunnos

Cernunnos is without a doubt one of the most famous gods of Ancient Gaul, and yet he is actually one of the most mysterious Gallic deities. Sure, he definitively marked the imagination of people - I mean he was literaly used as the basis for the Wiccan Horned God, and you will see lots of Cernunnos-copycats in fantasy RPGs and the like. But... we actually do not know the truth about this god, and despite everybody on the Internet trying to make it sound like we have an easy and simple summary of what he is, we only have strong theories and conflicting hypothesis.

I/ What we actually have

As with a lot of Gallic gods, Cernunnos exists not in legends or myths, but through a name and a visual. The name Cernunnos is found three times all on its own in Gallic documents. One was a Greek inscription from Montagnac that only says "This is dedicated to Karnonos of Alisontia". The other two are identical inscriptions found in Luxemburg (near Steinsel), votive inscriptions of wish-offerings merely saying "Deo Ceruninco". There is actually a fourth inscripton of the name Cernunnos - and it is from this one that we get the spelling we use today - but it is a special one. Unlike the other three, this one has a picture alongside it identifying the god visually. It is the famous "pilier des Nautes" found under Notre-Dame-de-Paris, the "pillar of the Nautes", the "pillar of Boatmen", considered one of the most important Gallic monuments (because it depicts a set of divine portraits with their names explicitely spelled out).

It is only thanks to this pillar that we know today that the many depictions of a male horned god found across Gallic art are meant to be Cernunnos. There are too many visual depictions of him to be listed here (sixty or so were found by archeologists), but among the most famous is the one I put a picture of above: the Cernunnos of the Gundestrup cauldron found in Denmark.

Here is what Cernunnos looks like on the pilier des Nautes:

So, we have a name and a bunch of pictures. Let's try to break it all down.

When it comes to the name, Cernunnos/Karnonos, it is commonly agreed by etymologists and those that studied the Gallic language that it means "the horned god". "Carnon/Karnon/Karn" was known to mean "horn", both in the sense of animal's horn and a blowing instrument - it was tied to the Gallic tribes known as the Carni and Carnutes, and to the Celtic carnyx. The "kern" part is also considered to be equivalent to the Old Irish "cern", which was associated with horned beasts. Some have pointed out that if the "Cern" of "Cernunnos" means horn, the "unnos" could be a suffix meaning "beautifully" - so instead of Cernunnos being the "horned god" or the "horned one" it would mean "He who is beautifully horned" or "He with beautiful horns". But all in all, his name stays connected to horns.

[But is it truly his name? This is another debate typical with the gods of Gaul: we do not know the differences between the proper names, the titles and the nicknames. It could be (to take a Greek comparison) like Hestia's case, where he names literaly means "hearth" but is a proper name ; or it could be like the "Old Man of the Sea" which was a generic nickname for a whole group of sea deities.

Now let's talk about the images of the god. Thanks to having so many depictions of him, we can identify recurring traits that define his visual.

Cernunnos always appears with his legs crossed, in a position (the "lotus" or "yoga positon" to take Asian terminology) that is considered, depending on the sources, either "very unusual for a god of Gaul", either "absolutely typical of Celtic representations of gods, warriors and heroes"... Well, he is almost always in the "lotus position" - in rare cases, he can be standing up. Cernunnos is also always wearing a torc, the traditional Gallic ornament, though he isn't always wearing it around his neck as one would expect: sometimes he holds it in his hands, other time it hangs from his antlers. Speaking of antlers: as we said, Cernunnos is a horned god, and he is usually depicted with antlers. But sometimes, more rarely, he rather sports goat horns - maybe it is a Romanization effect, as he got confused with Pan?

Cernunnos is always a male figure, though his actual age is unclear. Sometimes he is a mature and bearded man, but we also have "ephebe" depictions of him as a beardless youth - that some researchers even go as far as to describe as "child-like". Similarly, he keeps oscilatting between being a singular entity, and a triple-god with three heads or three faces. The disposition of the three faces can be really weird and freaky - for example, he can have a regular human head, and two small human faces growing from either side of his neck, or from the top of his head.

He usually always has a bag or basket with him, a bag that he eithers opens or that is simply sitting before him, spilling its content: sometimes the bag is filled with food, other times with coins, and other tims yet with grain. Cernunnos is usually sitting in the middle of a trio (as in two other humaoid or divine figures are by his side), or he is surrounded by various animals - which he can be seen holding with one hand, or petting near his lap. There are various animals he is associated with - we have seen him with stags, with bulls, with rats, with dogs, with lions, with goats... He is most notorious for being often depicted with the symbolic-mythical beast of Gaul known as the cryocephal snake: a ram-headed snake, whose exact meaning is still unclear to this day. However, Cernunnos seems to really like them: sometmes they just sit side by side, sometims he holds it by the throat, sometimes he feeds it, and other times two of them sit on his lap.

(This depiction above lacks any horns, but there are two holes at the top of the head implying that the horns were a different part of the statue added separately - which is very interesting in the theory of Cernunnos having antlers that "fall")

One of the problems with the Cernunnos visuals is that it is not clear where they stop, as we got a wide range of variations between the animal and the man. For example, there are strong theories according to which Cernunnos appears on the Strettweg chariot, as the tiny deer with oversized antlers that two men are holding (which would mean Cernunnos could be depicted as a full stag without human traits):

And on the opposite spectrum, a Gallo-Roman statue was found in Amiens of a fully human deity... except for one deer ear on the side of his face. One of the theories to explain this bizarre statue of the first century claims that it is an hyper-Romanized depiction of Cernunnos - though other theories do exist (for example, when the statue was discovered, it was originally believed to depict Midas, with a variation of the "donkey ear" punishment):

And you also have in Bouray a cross-legged god with deer legs rather than antlers or ears:

Given how "late" the visual depictions of the gods of Gaul was, and how the Romanization of Gaul strongly encouraged and favorized the depiction of deities as humanoids (to fit with the Greco-Roman deities), it is very likely that Cernunnos started as a divine stag, as fully animal, and then slowly, especially under the Roman influence, became more and more humanized... (There's also a fascinating case of antlered-goddesses at Clermont-Ferrand and Besançon, but that's for later).

II/ Some theories

Now that we have the name and the visuals done... What's Cernunnos deal? Again remember we can only make theories based on these fragments and their context - but we do not know for certain if it is the truth.

A: It is agreed that Cernunnos is a nature god, and a god of abundance. The fact he is half-stag, and usually depicted with animals, and even holding them in a gesture of domination or use, shows that he is a fauna god, which prompted some researchers to identify him as one of the avatars of the "Lord of Animals, Master of Wild Things" archetype of Indo-European myths. But more importantly we are certain that he dealt with abundance and prosperity - thanks to him always having a big bag of grain, food or money. He was very clearly a god of riches and wealth - be them natural (grain, food) or manufactured (coins). Some have highlighted the idea that this tied to the symbolism of "forests that have big strong stags in them are bound to be fertile places filled with resources". Cernunnos' ties to abundance cannot be denied because in some Classicized depictions of him (such as the silver goblet above), he is literaly seen holding a cornucopia, aka a horn of abundance.

Some people even want to push the domain further by thinking Cernunnos might have been a god of sexual and reproductive fertility - but this is not based on any visual or religious clue. Rather this theory ties on the European symbolism of the stag as a symbol of virility and reproductive prowess, so it is a purely contextual reading, to be handled carefully. We are only truly certain that Cernunnos offered lots of money, lots of grain, lots of food, and lots of animals (him being surrounded by animals might be an extension of the "I offer you this bag of grain" visual, since animals were hunted down for food, so he isn't just a god of good crops and economic riches, but also one that ensures a plentiful hunt).

B: There is a strong theory going around that Cernunnos might be a seasonal god, or a deity of the seasonal cycle. This idea comes from various elements pieced together - and which added with the A theory above, would make this go a sort of "Father Nature" figure. It all starts wth the European symbolism of the antlers and the stag in general: given the antlers fall and grow with the turn of the seasons, the stag has been used heavily in Europe as a way to measure the year or symbolize seasons. Some researchers theorized, based on how the size of Cernunnos antlers changes through depictions, and on how he is sometimes a beardless youth sometimes a bearded mature man, that Cernunnos, like the stag, had a seasonal cycle. For some he just loses and grows back his antlers (there is a Cernunnos depiction at Meaux with what seems to be the stubs growing back after antlers fall, which would support this theory), but others push it further by claiming the god died and was reborn each year with winter/spring - an idea inspired by the Indo-European archetype of the dying/sacrifical vegetation god.

There is a specific depiction of Cernunnos that ties into this whole - and I will have to trust Yann Brekilen's word for this, as I couldn't find any picture of the engravings he described. According to him, on the Gallo-Roman Germanicus Arch/Arc, by Saintes, there is a dual depiction of Cernunnos. On one side of the Arch, he is part of a trio: he is sitting crossed-leg with antlers on his head, but naked (usually Cernunnos s clothed in some ways). By his side there is a man armed with a club/mace (which might be tied to the "god with the mace", we'll see that in later posts), and a woman holding a cornucopia. Now, that's on one side of the monument - but on the opposite side, the scene is reproduced... with both the armed man and the antlers of Cernunnos missing, only leaving a regular cross-legged naked man, and the cornucopia-woman. Speaking of this cornucopia-woman: there are repeated talks and interpretations of any female figure by Cernunnos' side to be a "Mother-Goddess" or Earth-Goddess supposed to be the wife/companion/lover of Cernunnos. This is all part of an effort to make Cernunnos a "father-god" (which makes sense in some ways), and it ties into the whole reading of his myth as being a seasonal cycle (the god dying and resurrecting after impregnating his female counterpart ; something the Wiccan mythology for example reused in their beliefs), but... If you ask me, I am not really convinced? A lot of people insist on there being a "Mother Goddess" clearly by Cernunnos' side, but sometimes you see these people reinterpret a lot of the visuals, and it is not obvious that the female figure is with him (Cernunnos is usually surrounded by male figures rather than female ones). Plus, we know the Mother Goddess of Gaul tended to come in three (the famous Matronae) so... I am a bit doubtful of that, but that's just me and because of a lack of convincing evidence.

III/ Comparisons and equivalences

As I said in my introduction post, a lot of what we know about the Gallic gods comes from the syncretism the Romans operated with their own deities. And with Cernunnos it is... complicated. Because we do not know exactly who was the Roman equivalent of Cernunnos (since the Romans did not speak of him), and based on researches we have two likely candidates. It is very possible Cernunnos might have been split into those two Roman deities, or at least that his attributes led him to be interpreted as two deities mixed in one.

On one side, there is a very strong and popular theory that Cerunnos was the god Cesar, in his description of the religion of Gaul, called the "Dis Pater". "Dis Pater" was the Latin god that was equated and synthesized with the Greek Hades under the share nickname "Pluto", "the rich one". This was because Dis Pater was not originally a god of the dead in the old Italian religion - he was an underground god, indeed, but a chthonic god of riches and wealth, an earth-god of fertility (his very name meant "Rich Father"). This is what tied him to Hades, the richest of the Greek gods - and made him the new god of the underworld and the dead, Pluto. So, equating Dis Pater with Cernunnos makes sense as we do know that both deities were strongly associated with an earthly form of fertility: Cernunnos, just like Dis Pater, brought grain and earth-grown fruit, as well as precious metal (in the form of coins). Not only that, but Cernunnos was strongly associated with the ram-headed snake, and while we don't know much about this mythical being (typically a companion of male gods in Gallic art), it seems to have been a chthonian symbol, and perhaps even a form of guardian of the world of the dead (or a guardian of underground riches cousin of the dragons of legends). This is what led many to interpret Cernunnos as a chthonian deity, perhaps even an afterlife deity - a tradition that seems to have been in early Christian art, where Cernunnos was often associated with the "mouth of Hell" or the "entrance to Hades" (like the 9th century manuscript Stuttsgart Psalter, which illustrates Cernunnos in a depiction of the Christ descending into Limbo.

If Cernunnos is indeed Cesar's Dis Pater, then it would be extremely interesting, because Cesar wrote in his records that the peopleof Gaul believed Dis Pater to be their divine ancestor, and the "father of their race". Aka, the Gallic Dis Pater is meant to be an All-Father, the first ancestor of the Gallic tribes, and the origin of the human race (or at least of the people of Gaul). If Cernunnos is this Dis Pater, it would confirm his role as a "Father-God" and his links to a potential "Mother-Goddess". (It could also explain why he so persistantly wears a torc, as an emblem of the civilization and traditions of Gaul) If Cernunnos is also the Dis Pater, it would give him a role as a nocturnal god, since Cesar resumed in his texts (or rather "recaped" since he was doing a report based on Posidonius own records) that it was because the people of Gaul descended from Dis Pater that the druids measured the time not in "days" but in "nights"...

The other very likely candidate for the Romanized Cernunnos is the one we call the "Gallic Mercury". We know that Mercury was one of the most popular and widespread gods of Gallo-Roman gaul. Cesar did mention him as one of the most important gods venerated by the Gallic tribes before the omans arrive (though this would contadict the is Pater theory, since Cesar identifies Dis Pater and Mercury as two different deities in the Gallic beliefs). Still, Mercury was a god of commerce and riches before all - even more so than his Greek counterpart Hermes - so it makes sense that he would be present in the Gaul province of the Empire, which was big heart of commerce. And where Mercury has a pouch of coins, Cernunnos has a full bag of them... And in several Gallo-Romans depictions one of the two gods that surround Cernunnos is very obviously Mercury... [Several of the images in this post are of the altar of Reims, which depicts Cernunnos surrounded by Apollo on one side and Mercury on the other] And Cernunnos' presence on the Pillar of Boatmen implies he was tied to the fluvial sailors, and to the fluvial commerce and travels... And in Luxembourg we have Gallic depictions of stags vomitting coins, again insisting on how the stag was associated with riches... Even if you take Cernunnos as a chtonian god or death god, it ties to Mercury's role as a psychopomp inherited from Hermes ; and Mercury's presence by Cernunnos side on the altar of Reims for example makes sense if you consider one of the deities Cernunnos was conflated with was Pan (hence the goat horns) - aka, the son of Hermes... Everything is tied together into one big convoluted web of inter-mythologies.

And when it comes to comparisons to other Celtic mythologies, things are a bit... In French we say "vaseux" - basically there were parallels drawn between Cernunnos and Celtic figures of the Isles, but they rely on very meager if not unstable links. For example some have tried to identify the Cernunnos of Gaul with the Irish figure of Nemed (interpreted as a "stag-god" leading "stag-people" or "deer-people"), and in return the battle between Nemed and Balor for the land of Ireland was projected onto the scene depicted on the Arch that I described prior - a battle between the horned god and the god with the mace for the "earth-mother", the cornucopia woman, the land-goddess. The acceptance of this scene between the horned god and the mace god as a battle for the mother-goddess (which, I insist, was not PROVEN in any way and is completely hypothetic and theorized with no definitive proof - maybe the mace god is here to sacrifice the horned god for the cornucopia-woman, or maybe he is just here to cut off his antlers, or maybe the cornucopia woma cheats on Cernunnos wit the mace god, we cannot know), also led to vague comparisons being drawn to the story of Pwyll and Arawn and how they exchange each other's identities, but we are really in a stretch here.

More interestingly there is a Welsh comparison that could indicate a leftover of a Christianized Cernunnos in an Arthurian setting: the Owein tale (Mabinogi): Kynon, a knight of King Arthur's court, describes how in his youth he had to encounter an ugly knight clad in a black armor who had the information he needed to find his enemy. The knight lived by a "fountain" (a water stream) surrounded by wild and ferocious animals - and to give Kynon the information he needed, the ugly black knight struck a stag nearby, and the animal lowers its head in the direction Kynon must follow. It is very plausible that this supernatural knight who hits an informative stag and who lives surrounded by wild animals is a form of Christian censorship or caricature of a Cernunnos figure, going from a wise and benevolent stag-god to an ugly evil knight who abuses animals, and who has his duality human/beast split between the knight and the stag.

There were also tenuous elements that made people consider the Irish Conall Cernach (known for being one of the sidekicks of Cuchulainn) as a diluted version of Cernunnos as a "Master of Beasts" - more precisely an episode in "The Cattle Raid on Fraech" where instead of killing a monstrous snake, Conall somehow tames it and wears it as a belt, has been compared to Cernunnos' handling of snakes and ram-headed snakes. And don't even get me started on the many, MANY saints of Catholicism that are supposed to be leftovers or reinventions of Cernunnos (saint Ciaran of Saighir, because he tamed wild beasts including a stag ; or the saints of Bretagne Edern and Théleau both supposed to ride a stag instead of a horse...).

The complicated thing (well ONE of the complicated things) with Cernunnos is that he is tied to the stag, and the stag was one of the most prominent smbols and images of the medieval and proto-medieval imagery in Western Europe. You had lot of old mythology stuff that survived in modern days, but you also had lots of medieval symbolism and images (like how the flying stag was one of the symbols of the king of France), and a HUGE re-use of the stag by Christianity in various forms (from the antlers falling being used as a symbol of the Resurrection, to the hunt for the white otherwordly stag of Celtic myths suddenly becoming a hunt for Christ incarnate when a glowing cross appears above the stag's head...). As such it is hard to pin-point what the Gauls truly believed the stag meant, versus the stag symbolism that arose in the Middle-Ages.

To conclude this post, while I said I had my doubts with systematic identifications of Cernunnos as a companion of a Mother-Goddess, I want to briefly return about a fascinating trivia of Gallic researches: the existence of a female version of Cernunnos, a "Cernunna" we could jokingly say.

Little figurines and statues were found of a horned goddess - sometimes with antlers! - in both the area of Clermont-Ferrand (which was the domain of the Avernes folk) and around Besançon (the Séquane folk). Who were these goddesses? Local variations of Cernunnos? Sisters, daughters or wives of the god? Or completely unrelated deities? Were they one or several (some are more matronly, motherly figures such as the one with antlers above, others have Venus-like poses unveiling their breast and legs such as the bull-horned below)?

We will probably never know - but while they can be incarnations of this famed "Mother-Goddess" companion of Cernunnos everybody speaks about (and links to the importation of the cults of Demeter and Cybele in Gaul), it is VERY likely these statues date from the Gallo-Roman era and from a Romanized version of the Gallic religion. Indeed, they are all tied by their attributes - they hold a cornucopia, and a "patère" (sacred vase for religious libations). Attributes present in very Romanized Gallic goddesses (such as Rosmerta), but also in typical Roman deities (mainly the lares). Add to that how the adjunction of a male attribute (the stag antlers or bull horns) to a female figure is VERY unusual for Gallic depictions (where the genders are neatly split), while the divine androgyny was a feature of Greco-Roman mythology (the effeminate Apollo and Dionysos, the masculine goddesses Athena and Artemis, the mythical Hermaphrodite...), and it is very likely these statues of the "Cernunna" are the result of the Roman religion "breeding" with the Gallic beliefs...

#gods of gaul#gallic mythology#cernunnos#ancient gaul#religion of gaul#gallic religion#gallic gods#gallic goddesses

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

St Martin and the Beggar by Alfred Rethel

#st martin#saint martin#beggar#art#alfred rethel#cloak#gaul#france#chivalry#roman#cavalry#soldier#knight#knights#christianity#christian#medieval#middle ages#martin of tours#mediaeval#history#europe#european#religion#religious art#white horse#white steed#armour#horse#roman empire

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

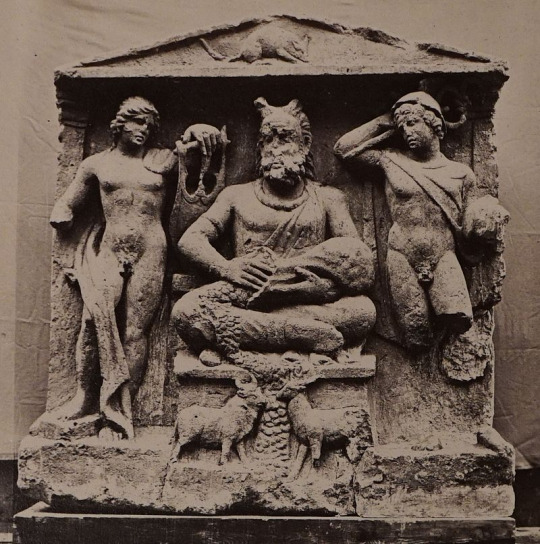

Terracotta mold from Roman Gaul, most likely used to make a relief medallion that would then be applied to pottery from the Rhône valley. On the mold, the god Mercury, seated at right in his sanctuary and holding his caduceus staff, receives a sacrifice of burnt offerings. Artist unknown; 1st cent. BCE/CE. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Rome#Roman Empire#classical mythology#Roman religion#Ancient Roman religion#religio Romana#God Mercury#Gaul#Roman Gaul#art#art history#ancient art#Roman art#Ancient Roman art#Roman Imperial art#Gallo-Roman art#terracotta#sculpture#relief sculpture#Metropolitan Museum of Art

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Look at this photo I took ! It's a part of the Pillar of the Boatmen, a monumental column honoring both Roman and Gallic gods built in ancient Paris in the first century.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

They don't ever mention God in The Hunger Games, right? I have been looking for an exclamation of "oh god!" or something like that but never seen it. In TBOSAS, Gaul dismisses the burial rituals of 2 are superstition, so I assume the Capitol is anti-religion. But it sounds like some of the districts do have some supernatural beliefs (2, obviously and 4 and 10 have similar weddings), we just only see 12 which doesn't seem to have any religion?

Am I wrong?

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Horned Serpent

So before I get started on this one, I have a couple of things to get out of the way. First, I will be using she/her pronouns for the Horned Serpent; this is just because UPG and because I'm used to it. I know someone else who venerates/worships the Horned Serpent, uses they/them pronouns for them, and considers them to be beyond gender / present as whatever gender they feel like. Second, I will be focusing on my interpretation of her on the Gundestrup Cauldron, in part because there's really not a lot of literature on her, even when you include works that specifically analyze Cernunnos' depictions. Third (and related), I will be using the National Museum of Denmark's estimate as to when/where the Gundestrup Cauldron was made, which is roughly in the Danubian or Wallachian Plain(s) around 150 BCE to 1 CE (link).

So first a little historical & cultural context. This area, as far as culture groups, would have been a heck of a melting pot, between the Dacians and Thracians that already lived there, the Scythians coming in and also living near by, the Gauls that moved in around the 300s-200s, the Greeks who came up and started establishing colonies along the Black Sea in the 300s, and the Romans, encroaching on everyone's business around the time the Cauldron was built. A pretty solid primer on the history of the region is A Companion to Ancient Thrace, published by Wiley Blackwell.

So I'm gonna try to make sense but it might be a little disorganized going forward. Anyway, onto the actual thoughts & stuff. So anyone who's taken even a passing glance at Cernunnos is well aware of the Horned Serpent, since she is present in basically every ancient art you can find with him. On the Gundestrup Cauldron, she appears three times, all on the interior panels. One is at the Hero's heel, who's holding the wheel; a second is at the end of a line of heroic riders, which seems to be a Thracian horseman motif; and of course the famous Cernunnos panel. In Thracian Tales of the Gundestrup Cauldron, published by Najade Press, Jan Best presents an interpretation of the interior panels as a story, and assumes that Cernunnos is singing in his famous panel, specifically about the secrets of immortality, a concept which was very popular at the time. I agree with this and I also assume that the depiction of Taranis / the wheel god is that he is also singing, and if he is singing then the lions and griffins - both predators associated with kingship (griffins were protectors of the pharaoh, and also decorated certain tombs out in ancient Persia), then the action of passing off the Wheel must have symbolic meaning, such as being handed the Wheel of Heaven.

The Gundestrup Cauldron's exterior also has very clear influence from the Scythians, you can almost 1:1 map the gods based on Herodotus's retelling of the Pontic stories. I believe there are also thematic parallels going on here on the Wheel God panel, featuring a new god/king being given the symbol of his domain. Wikipedia actually has some relatively thorough articles on Scythian religion as well as the genealogical myth specifically, which is the myth that I personally associate with the wheel-giving panel. As well, the animals in this panel don't appear to be particularly concerned with attacking anyone - if anything, the griffins and lionesses are slightly tilted from one to the next, which makes me think it's more likely that they are dancing, especially if the human/divine subjects are singing, especially if the human with the helmet is receiving a high honor, potentially his rank amongst the gods. In this panel, she is just at the hero's feet, not really joining the parade if the animals, but clearly not ready to attack either, but her attention does seem to be drawn towards the hero.

The final panel she is on is the panel featuring the nine soldiers and the heroized dead, represented by the "Thracian horseman" motif. After Alexander the Great and his penchant for having statues of himself be on horseback, it became popular for wealthy men and nobles to depict themselves riding horseback to a goddess or sacred tree (unfortunately my best source discussing this in English is also not great and he comes up with some..... questionable theories), but the popularity seems to have blown up to the point where even deities such as Zeus were depicted on horseback in a similar manner. There are also mentions in a few other sources that the Thracians believed in the ability for people to essentially become immortal after death. Unfortunately, I'm having trouble sorting out my notes and this essay has been nagging me for weeks now.

Anyway, I interpret this panel as what is expected to happen to us after we die - the "ordinary", so to speak, are lead to a deity, likely to be reincarnated (this is honestly just a guess on my part largely due to the popularity of that in Greece for ever, and Grecian influence was in full swing by the time the Cauldron was made), meanwhile the "extraordinary" are lead by the Horned Serpent.

This is where I tie all three together to my upg/theology: The Horned Serpent is a friend and ally to Cernunnos. He teaches the secrets of life after death to those who will listen. The Horned Serpent is by his side during his teaching, and when we die, if we have proven ourselves worthy during life, she guides us through the trials of the afterlife. If we succeed in these trials, we are awarded with apotheosis - becoming a god or godlike - and she stands by our side as we earn this prize.

@musingmelsuinesmelancholy sorry it took me so long x.x & I hope this makes sense!

#cernunnos#thracian polytheism#gaulish polytheism#dacian polytheism#scythian polytheism#the horned serpent#balkan paganism#celtic paganism#paganism

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Know any good sources on Celtic (specifically Gaulish practices)? I know it’s not your area, but you seem like someone who might know some people who dabble in that sort of stuff. The area I live in has some celtic archeological sites, but sadly not much is known about the local religion or culture. I am trying to put together a Romano-Celtic hearth cult, but it’s difficult finding practices and deities that feel right.

Gaul is a larger Celtic area of Western Europe (modern-day France and parts of modern-day Belgium, Germany, and Northern Italy). I say this because the Celts, when invaded by Rome, took in a lot of Roman religion including Hellenic and (rarely) Kemetic beliefs as well. When the Celts did this, so did the Gauls.

If it helps at all, the specifics you're looking into is called Gallo-Roman, which is part of the larger Romano-Celtic area.

This selective acculturation manifested in several ways. One of the main ways we see this is with the melding of Greco-Roman deities with Gaulish (Celtic) deities. Gaulish epithets for Roman gods (Jupiter Poeninus) and Roman epithets for Gaulish gods (Lenus Mars). Roman gods were given Gaulish god partners (Mercury and Rosmerta & Apollo and Sirona). Towards the east of the Gauls, many mysteries were formed, including one for the Greek hero Orpheus, the Iranian (or Persian) god Mithras, and the Egyptian goddess Isis. In other words, a whole lot of syncretism.

When it came to the Gauls (and the Celts overall) a main part of their belief system was the heavy use of animal imagery. More specifically, zoomorphic deities. However, we see a lot more human-looking representations of the gods because the Romans (and Greeks) weren't too keen on the idea (see Greco-Egyptian).

As for specifically Gallo-Roman hearth religious beliefs, the Lares (Lar singular) is a good place to start. They're the equivalent of Agathos Daimon in Greek religion (Hellenism). Essentially, they're personal household deities that are connected to the hearth.

A majority of the information we have about the Gaelic culture and the eventual melding of the Gallo-Roman culture stems from two sources: artifacts and Julius Ceasar, who wrote all about in what we now call the "Commentarii de Bello Gallico". The gods that he mentions the Gauls worship (like Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, and Minerva) aren't really the Roman gods that the Gauls are worshipping at that time but rather the closest thing Ceasar can connect. For example, Caesar may say that the Gauls worshipped Mars, when in reality they were worshipping Lenus, a healing god that quickly became associated with Mars because of Caesar and the Roman Empire. However, not all of them were caught. Gobannus is the most well-known example we have, with him being the equivalent to the Roman god Vulcan or the Greek god Hephaestus and yet Caesar makes no comment on the Gaulish god.

One other thing, the specific time we are taking a look at was prior to the overtaking by the Anglos, Saxons, and Jutes (aka pre-Anglo-Saxon times). Because of this, Germanic (Norse) gods weren't known to these people yet. Odin, Thor, and Freyja were unknown to them at this point in time.

Other than that, the last thing I can give to you are articles and books that I stumbled upon that may pique your interest. I do recommend a couple of Wikipedia links, but just know that I recommend using Wikipedia as a jumping-off point. Hope this helps! :^)

Becoming Roman: the origins of provincial civilization in Gaul -- Greg Woolf

https://archive.org/details/becomingromanori0000wool

The gods of the Celts -- Miranda Green

https://archive.org/details/godsofceltsar00mira

Gallo-Roman Religious Sculptures -- A.N. Newell

https://www.jstor.org/stable/640758

Fifth-Century Gaul: A Crisis of Identity? -- John Drinkwater & Elton Hugh

https://www.loc.gov/catdir/samples/cam031/91018375.pdf

Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War: literally translated -- Frederick Holland Dewey, A.B.

https://archive.org/details/caesarscommentar07caes

Category:Gaulish gods -- Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Gaulish_gods

Category:Gaulish goddesses -- Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Gaulish_goddesses

sources:

https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/1999/1999.10.34/

http://www.deomercurio.be/en/dii.html

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Celtic-religion/The-Celtic-gods

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lares

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lar-Roman-deities

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallo-Roman_culture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallo-Roman_religion

#ask#witch#witchcraft#witchblr#pagan#celtic#gaulish#roman#celtic deities#celtic pantheon#gaulish deities#gaulish pantheon#roman pantheon#roman gods#ancient rome#gallo-roman#romano-britain#romano-celtic#hearth

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would Francis be catholic or atheist today ? Hard to say anything about his religion. There's no official census like that to base his faith on the population's, so it's hard to say. However, as a french, I think this is how he would describe himself as : "Traditionally catholic"

A lot of people I know around me, including the French side of my family, don't believe in god. However, some of them would still practise catholic rituals (don't know the word sorry eidheje) like (mostly) baptism. So when it comes to polls, they'd vote catholic even though they don't believe in god. Of course a lot also simply say they're atheist (close family in my case).

So what about Francis? [Read it through my headcanon that he is born a gaul] Well, he's seen the birth of Christianity, but he would have had gone through two religions by then (Celtic->Roman). So, it might be me looking at it through an atheist point of view, but I don't think Francis would have believed that much in Christianity—at first. When the Franks came, he finally got baptised and adopted the Christian faith. But I want to say he did so more put of a will to stay close to his people, the gallo-roman, he who was a gaul before. Faith might have come to him later on. He might not have been the strongest believer, but he was attached to Christianity (especially Catholicism) because it's what he saw as a link between him and the people (see Jeanne d'Arc!).

When the religion wars started, he was devastated, because the thing he thought was bringing him peace was now tearing him apart. But he still called himself Catholic. When the French Revolution started, he saw how the clergy were seen by the people, and began to doubt his faith. With the other revolutions of the XIXth century, he ended up not trusting the Church anymore and grew distant with his faith. It's not like his people would hate him for it anyway, a lot of them did so as well.

And here he is now. Not quite Christian, not quite Atheist. Did he ever truly believe in god? No idea, and I don't know if I will ever make up my mind about it. Agnostic theist/atheist would be the closest bet. He can't deny how much Christianity has impacted his and his people's lives, for better of for worse. But as a french, Traditionally Catholic seems to be the best term to describe it.

#hetalia#aph france#hws france#accidental self promoting (yes) but i do talk about it in my fic#him and his struggle to identify with his people#(if i offend someone i'm sorry)#(ive never posted anything about religion before nor is it a subject back here at home–so i don't know what's offensive or not rip)#mes blogs#hetalia headcanons

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Legends and myths about trees

Celtic beliefs in trees (5)

Druids - Immortality of the spirits

The Celts worshipped nature, especially trees. They set aside a place surrounded by trees and nature as a sanctuary, which they called 'Nemeton'. Religious ceremonies were officiated by druids and took place in sanctuaries with oak trees, the trees most venerated by the Celts.

The druids were adept at magic and witchcraft, had the ability to foretell the future. They had specially recognised privileges and the inhabitants of the community did not go against the decisions of the druids.

We do not know with certainty what their doctrines (Druidism) were, as the druids placed great emphasis on oral tradition and left no written records. We can rely on the Greek and Roman classical writers:

According to Posidonius (135-51 BCE, Greek politician, philosopher and historian), “the Celts believed that the human soul is immortal and that the soul moves to another body and lives another life”. Strabo ( 64 or 63 BCE – c. 24 CE) also notes that the Druids' “the human soul and the world are immortal. But sometimes fire and water prevail", recording a similar idea to Pythagoras.

The Pythagorean doctrine prevails among the Gauls' teaching that the souls of men are immortal, and that after a fixed number of years they will enter into another body.

Caesar made similar observations:

The main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed. Subsidiary to the teachings of this main principle, they hold various lectures and discussions on the stars and their movement, on the extent and geographical distribution of the earth, on the different branches of natural philosophy, and on many problems connected with religion.

One cannot help but think that at the heart of Druidism was the theory of the 'immortality of the spirit'.

If the Druidism is valid, then there would be a mixture of people around us today who have inherited the spirit of the ancient Druids as various other lives all over the world. For example, a star football player who gives people hope for life or ....... maybe just a tea lady.

木にまつわる伝説・神話

ケルト人の樹木の信仰 (5)

ドルイド〜霊魂の不滅

ケルト人は自然、特に樹木を崇拝した。木々と自然に囲まれた地を聖域として確保し、「ネメートン」とと呼んだ。宗教的儀式はドルイドが司祭となって、ケルト人が最も崇拝した樹木であるオークの木のある聖域で行われた。

ドルイドは魔法や呪術に通じ、未来を予言する能力があった。彼らは特別に認められた特権をもち、共同体の住民は、ドルイドの決定に逆らうことはなかった。

ドルイドは口承を重視し、文字記録を残さなかったので、ドルイドたちの教義 (ドルイディズム) がどのようなものであったか確実なことはわからない。ギリシャ・ローマの古典作家たちに頼れば:

ポシドニウス (紀元前135~51年、ギリシャの政治家・哲学者・歴史家)によれば「ケルト人は人間の魂は不滅であり、魂は別の体へと移り、別の生を生きる」と考えた。また、ストラボン (紀元前64年または63年 - 紀元24年頃) は、ドルイドの「人間の魂と世界は不滅である。しかし、時に火と水が勝つことがある」というピタゴラスと同じような考えを記録している。

ピタゴラス学派の教義はガリア人の間で広まっており、人の魂は不滅であり、一定の年月が経てば別の肉体に入るという教えである。

シーザーも同様の考察をしている:

あらゆる教えの主目的は、彼らの意見によれば、人間の魂の不滅性に対する確固たる信念を学者に植え付けることであり、それは彼らの信念によれば、死によって一つの天幕から別の天幕へと移るにすぎない。なぜなら、死の恐怖をすべて取り除くこのような教義によってのみ、人間の最高の勇気が育まれると彼らは言っている。この大原則の教えに付随して、彼らは星とその動き、地球の広さと地理的分布、自然哲学のさまざまな分野、宗教に関連する多くの問題について、さまざまな講義や討論を行っている。

ドルイドの教義の中核には「霊魂の不滅」説があったと思わざるを得ない。

もし、このドルイドたちの教義 (ドルイディズム) が有効であるならば、現代の私たちの周りにも、古代ドルイドの精神を受け継いだ人々が、世界中のさまざまな生として混在していることになる。たとえば、人々に生きる希望を与えるサッカーのスター選手とか...... あるいは、ただの給仕係のおばさんかもしれない。

#druid#celtic belief#forest people#tree spirit#tree myth#legend#wisdom#mythology#nature worship#immorality#philosophy#nature#druidsim

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there! Hope you're well - 🔮 and ⭐ for the ask game please!

Hello hello! Same to you friend :)

🔮 What is something you wish people outside your practice knew more about?

Hmm, I’d have to say the value of oneiric work. I don’t see much talk of oneiric magic outside the traditional craft scene. nor do I see much talk about spirit flight, which I personally believe is rather important to the practice of witchcraft.

As far as Gaul polytheism is concerned there’s not anything in particular I wish people knew more about, rather I hope that people understand just how little we know about the Gauls. Gaulpols have, or should have, a good academic understanding of Gaulish religion but the practice itself will be created by the polytheist or the custom/house/tradition they belong to.

⭐️ Do you delve into topics like the occult or the mysteries? Do you do anything esoteric?

Yes! I’ve been a witch far longer than I’ve had an interest in polytheism.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The gods of Gaul: Introduction, or why it is so hard to find anything

As I announced, I open today a series of post covering what some can call the "Gaulish mythology": the gods and deities of Ancient Gaul. (Personal decision, I will try avoiding using the English adjective "Gaulish" because... I just do not like it. It sounds wrong. In French we have the adjectif "Gaulois" but "Gaulish"... sounds like ghoulish or garrish, no thank you. I'll use "of Gaul", much more poetic)

[EDIT: I have just found out one can use "Gallic" as a legitimate adjective in English and I am so happy because I much prefer this word to "Gaulish", so I'll be using Gallic from now on!]

If you are French, you are bound to have heard of them one way or another. Sure, we got the Greek and Roman gods coming from the South and covering up the land in temples and statues ; and sure we had some Germanic deities walking over the rivers and mountains from the North-East to leave holiday traditions and folk-beliefs... But the oldest gods of France, the true Antiquity of France, was Gaul. And then the Roman Gaul, and that's already where the problems start.

The mythology of Gaul is one of the various branches of the wide group known as Celtic mythology or Celtic gods. When it comes to Celtic deities, the most famous are those of the British Isles, due to being much more preserved (though heavily Christianized) - the gods of Ireland and the Welsh gods are typically the gods every know about when talking about Celtic deities. But there were Celts on the mainland, continental Celts - and Gaul was one of the most important group of continental Celts. So were their gods.

Then... why does nobody know anything about them?

This is what this introduction is about: how hard it actually is to reconstruct the religion of Gaul and understand its gods. Heck we can't ACTUALLY speak of a Gaulish mythology because... we have no myth! We have not preserved any full myth or complete legend from Ancient Gaul. The pantheon of Gaul is the Celtic pantheon we probably know the least about...

Why? A few reasons.

Reason number one, and the most important: We have no record of what the Gauls believed. Or almost none. Because the people of Gaul did not write their religion.

This is the biggest obstacle in the research for the gods of Gaul. It was known that the art of writing was, in the society of Gaul, an elite art that was not for the common folks and used only for very important occasions. The druids were the ones who knew how to read and write, and they kept this prerogative - it was something the upper-class (nobility, rulers) could know, but not always. Writing was considered something powerful, sacred and magical not to be used recklessly or carelessly. As a result, the culture of Gaul was a heavily oral one, and their religion and myths were preserved in an oral fashion. Resulting in a great lack of written sources comng directly from the Gallic tribes... We do have written and engraved fragments, but they are pieces of a puzzle we need to reconstruct. We have votive offerings with prayers and demands inscribed on it - and while they can give us the names of some deities, they don't explain much about them. We have sculptures and visual representations of the deities on pillars and cups and jewels and cauldrons - but they are just visuals and symbols without names. We have calendars - but again, these are just fragments. We have names and images, and we need to make sense out of it all.

To try to find the explanations behind these fragments, comparisons to other Celtic religions and mythologies are of course needed - since they are all branches of a same tree. The same way Germanic mythology can be understood by looking at the Norse one, the same way Etruscan, Greek and Roman mythologies answer each other, the mythology and religion of Gaul has echoes with the Celtic deities of the Isles (though staying quite different from each other). The other comparison needed to put things back into context is reason number 2...

Reason number two: The Romans were there.

Everybody knows that the death of Ancient Gaul was the Roman Empire. Every French student learns the date of Alesia, the battle that symbolized the Roman victory over the Gallic forces. Gaul was conquered by the Romans and became one of the most famous and important provinces of the Roman Empire: it was the Gallo-Roman era.

The Romans were FASCINATED by Gaul. Really. They couldn't stop writing about them, in either admiration or hate. As a result, since we lack direct Gallic sources, most of what we know about Ancient Gaul comes from the Romans. And you can guess why it is a problem. Some records of their religion were written in hatred - after all, they were the barbarian ennemies that Romans were fighting against and needed to dominate. As such, they contain several elements that can be put in doubt (notably numerous references to brutal and violent human sacrifices - real depictions of blood-cults, or exaggeratons and inventions to depict the gods of Gaul as demonic monstrosities?) But even the positive and admirative, or neutral, records are biased because Romans kept comparing the religion of the Gauls to their own, and using the names of Roman deities to designate the gods of Gaul...

Leading to the other big problem when studying the gods of Gaul: the Roman syncretism. The Gallo-Roman era saw a boom in the depictions and representations of the Gallic gods... But in their syncretized form, fused with and assimilated to the Roman gods. As such we have lots of representations and descriptions of the "Jupiter of Gaul", of the "Mercury of Gaul", of the "Gallic Mars" or "Gallic Minerva". But it is extremely hard to identify what was imported Roman elements, what was a pure Gallic element under a Roman name, and what was born of the fusion of Gallic and Roman traditions...

Finally, reason number three: Gaul itself had a very complicated approach to its own gods.

We know there are "pan-gallic" gods, as in gods that were respected and honored by ALL the people of Gaul, forming the cohesion of the nation. But... Gaul wasn't actually a nation. It was very much like the many city-states of Greece: Ancient Gaul was unified by common traditions, a common society, a common religion and a common language... But Gaul was a tribal area divided into tribes, clans and villages, each with their own variations on the laws, each with their own customs and each with their own spin on religion. As a result, while there are a handful of "great gods" common to all the communities of Gaul, there are hundreds and hundreds of local gods that only existed in a specific area or around a specific town ; and given there were also many local twists and spins on the "great gods", it becomes extremely hard to know which divine name is a local deity, a great-common god, a local variation on a deity, or just a common nickname shared by different deities... If you find a local god, it can be indeed a local, unique deity ; or it can be an alternate identity of a shared divine archetype ; or it can be a god we know elsewhere but that goes by a different name here.

To tell you how fragmented Gaul was: Gaul was never a unified nation with one king or ruler. The greatest and largest division you can make identifies three Gauls. Cisalpine Gaul, the Gaul located in Northern Italy, conquered by the Romans in the second century BCE, and thus known as "the Gaul in toga" for being the most Roman of the three. Then there was the "Gaul in breeches" (la Gaule en braies), which borders the Mediterranean sea, spanning between the Alps and the Pyrenean mountains, and which was conquered in the 117 BCE (becoming the province of Narbonne). And finally the "Hairy Gaul", which stayed an independant territory until Cesar conquered it. And the Hairy Gaul itself was divided into three great areas each very different from each other: the Aquitaine Gaul, located south of the Garonne ; the Celtic Gaul located between the Garonne and the Marne (became the Gaul of Lyon after the Roman conquest) ; and finally the Belgian Gaul, located between the Marne and the Rhine. And this all is the largest division you can make, not counting all the smaller clans and tribes in which each area was divided. And all offering just as many local gods or local facets of a god...

And if it wasn't hard enough: given all the sculptures and visuals depictions of the gods of Gaul are very "late" in the context of the history of Gaul... It seems that the gods of Gaul were originally "abstract" or at least not depicted in any concrete form, and that it was only in a late development, shortly before the Roman invasions, that people of Gaul decided to offer engravings and statues to their gods, alternating between humanoid and animal forms.

All of this put together explains why the gods of Gaul are so mysterious today.

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pagan religion did not depend on a very elaborate institutional structure, and the cults of each city were all organized locally; rabbinic Judaism, too, was very decentralized (Jews did have a single patriarch until around 425, but it is unclear how wide his powers were). Christianity, however, had a complex hierarchy, partly matching that of the state. By 400 there were four patriarchs, at Rome, Constantinople (since 381), Antioch and Alexandria (a fifth, Jerusalem, was added in 451), who oversaw the bishops of each city... Bishops were soon arrayed in two levels, with metropolitan bishops (called in later centuries archbishops) at an intermediate level, overseeing and consecrating the bishops of each secular province. Inside the dioceses of each bishop, which normally covered the secular territory of their city, bishops had authority over the clerics of other public churches... The church in the fourth and fifth centuries became an elaborate structure, with perhaps a hundred thousand clerics of different types, more than the civil administration, and steadily increasing in wealth as a result of pious gifts. It was not part of the state, but its wealth and empire-wide institutional cohesion made it an inevitable partner for emperors and prefects, and a strong and influential informal authority in cities; the cathedral church by 500 was often the largest local landowner (and therefore patron), and, unlike in the case of private family wealth, its stability could be guaranteed – bishops were not allowed to alienate church property... Even in a church context, bishops generally identified themselves with their diocese first, with wider ecclesiastical institutions only secondarily. But they were linked to the wider church hierarchy all the same: they could be called to order and dismissed by metropolitans and by the councils of bishops that steadily became more frequent, whether empire-wide (the ‘ecumenical’ councils) or at the regional level, in Spain or Gaul or Africa. The fact that this institutional structure did not depend on the empire, and was above all separately funded, meant that it could survive the political fragmentation of the fifth century, and the church was indeed the Roman institution that continued with least change into the early Middle Ages; the links between regions became weaker, but the rest remained intact.

Chris Wickham, chapter 3 of The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400-1000.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (March 28)

On March 27, the Catholic Church remembers the monk and bishop, Saint Rupert, whose missionary labors built up the Church in two of its historic strongholds, Austria and Bavaria.

During his lifetime, the “Apostle of Bavaria and Austria” was an energetic founder of churches and monasteries.

He was also a remarkably successful evangelist of the regions, which include the homeland of the Bavarian native, Pope Benedict XVI.

Little is known about Rupert's early life, which is thought to have begun around 660 in the territory of Gaul in modern-day France.

There is some indication that he came from the Merovignian royal line, though he embraced a life of prayer, fasting, asceticism, and charity toward the poor.

This course of life led to his consecration as the Bishop of Worms in present-day Germany.

Although Rupert was known as a wise and devout bishop, he eventually met with rejection from the largely pagan population, who beat him savagely and forced him to leave the city.

After this painful rejection, Rupert made a pilgrimage to Rome.

Two years after his expulsion from Worms, his prayers were answered by means of a message from Duke Theodo of Bavaria, who knew of his reputation as a holy man and a sound teacher of the faith.

Bavaria, in Rupert's day, was neither fully pagan nor solidly Catholic.

Although missionaries had evangelized the region in the past, the local religion tended to mix portions of the Christian faith – often misunderstood along heretical lines – with native pagan beliefs and practices.

The Bavarian duke sought Rupert's help to restore, correct, and spread the faith in his land.

After sending messengers to report back to him on conditions in Bavaria, Rupert agreed.

The bishop who had been brutally exiled from Worms was received with honor in the Bavarian city of Regensburg.

With the help of a group of priests he brought with him, Rupert undertook an extensive mission in Bavaria and parts of modern-day Austria.

His missionary journeys resulted in many conversions, accompanied by numerous miracles including the healing of diseases.

In Salzburg, Rupert and his companions built a great church, which they placed under the patronage of St. Peter and a monastery observing the Rule of St. Benedict.

Rupert's niece became the abbess of a Benedictine convent established nearby.

Rupert served as both the bishop of Salzburg and the abbot of the Benedictine monastery he established there.

This traditional pairing of the two roles, also found in the Irish Church after its development of monasticism, was passed on by St. Rupert's successors until the late 10th century.

St. Rupert died on March 27, Easter Sunday of the year 718, after preaching and celebrating Mass.

After the saint's death, churches and monasteries began to be named after him – including Salzburg's modern-day Cathedral of St. Rupert (also known as the “Salzburg Cathedral”) and the Church of St. Rupert, which is believed to be the oldest surviving church structure in Vienna.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feast Days: Martinmas

Anthony Van Dyck ~ "St. Martin Dividing His Cloak" (c.1618)

Happy Martinmas!

Today marks the feast day of St. Martin of Tours, who was bishop there from 371 CE until his death in 397 CE. He is the patron saint of many things, including: against poverty, against alcoholism, the poor, cavalry, Buenos Aires, quartermasters, wool-weavers, soldiers, and tailors, as well as wine growers, makers, and sellers. Whew! He must be very busy.

Keep reading for info about his life, a snitch goose, where the word 'chapel' came from, and how to tell what the weather will be like at Christmas.

His Life

Much of what we know about Martin comes from his hagiographer, Sulpicius Severus, who includes some 'artistic license' that is common in chronicles of the time, and therefore must be taken with a grain of salt.

Martin was born anywhere from 316-336 CE in Savaria, now Szombathely, Hungary. His father was a senior officer in the Roman Army, and as such was given land in northern Italy for his retirement. At the age of 10, Martin attended a Christian church against the wishes of his parents, and became interested in Christianity. Because of his father's status as a veteran, he was required to join the cavalry at 15. Dates surrounding his military service are shaky, but Severus states that, during his time stationed in Gaul, he was riding on horseback when he encountered a poor man with threadbare clothes. Having compassion on him, Martin used his sword to cut his own woolen cloak in two and gave the other half to the man. That night, Jesus Christ appeared to him in a dream, surrounded with angels and wearing half of the cloak. After this, Martin was baptised as a Christian. Though other miracles of his are recorded, this tale is the one most associated with Martin's life. It fits in with depictions of God or his angels in disguise as a beggar, traveller, &c., and is also a narrative found in many other religions and traditions. (Biblical examples include Abraham feeding the three angels in Genesis 18).

Martin dips from the army ~ fresco by Simone Martini (c.1320s)

With his new faith now firmly a part of his life, Martin decided to leave the army. Before a battle near modern-day Worms, Germany, Martin went before Emperor Julian and refused his salary, saying, "I am the soldier of Christ: it is not lawful for me to fight." They threw him in prison for this, but due to ye olde extenuating circumstances, he was released and discharged without further incident.

Martin made his way to modern-day Tours in France and declared himself a hermit, becoming a disciple and friend of Hilary of Tours. Because Christianity was Not OK™ in the Roman Empire, he and Hilary faced a lot of discrimination, including corporal punishment and exile. After converting his mother to Christianity and having numerous adventures, like living pretty much alone on an island, he and Hilary settled down in and around Poitiers, where Martin established Ligugé Abbey. It is the oldest known monastery in Europe! Martin made it his home base while he preached throughout western Gaul.

In 371 CE, the bishop of Tours died, and Martin was considered a good candidate for a successor. However, he liked living as a hermit and monk, and they resorted to tricking him into coming to Tours and then forced him to become the bishop. Legend holds that he tried to hide in a barn, but a honking goose gave him away. Hence he is the patron saint of geese, which I think is adorable. Martin proved true to his hermit ways, living very simply in huts with his monks. He established a rudimentary parish system, through which he visited different Christian communities and established monasteries. He was very determined in his efforts to convert local Pagans, as well as protect Christian institutions from unfriendly sects in the area, and in some cases he was successful. He died in 371 CE, already a venerated man. His popularity was ensured by his adoption by various French royals and by the Third Republic as a national symbol.

Martin has been portrayed by several famous artists, including Van Dyck, Peter Bruegel the Elder, and El Greco. He is usually portrayed on horseback, dividing his cloak for the poor man, though occasionally he can be seen riding a donkey. This references another story in his life about the time where he met the Devil and outwitted him. It also connects him to the image of Jesus riding a donkey into Jerusalem (recounted in Mark 1:1-11).

Martinmas and its Traditions

Martin lent his legacy to a host of English words and phrases, including those relating to the word 'chapel'. Temporary buildings that held the relic of his cloak (cappa in Latin) were referred to as cappella, and hence the word 'chapel' was born. A similar thing happened to the word 'chaplain', which derived from the word for the priest in charge of the cloak.

Though the Anglo-Saxon church did celebrate St. Martin to some extent, more references to Martinmas celebrations begin to crop up after Norman Conquest of 1066, when the Frenchman William the Conqueror invaded England. Supposedly, he promised to build an abbey dedicated to Martin if his invasion of England was successful. William was very likely familiar with the early Mediaeval association of the battle-hungry rulers of France with St. Martin, and was possibly responsible for his increased popularity in England.

In England and Scotland, and indeed through much of western Europe, Martinmas became a celebration marking the culmination of the harvest and the beginning of winter. From the late fourth century through the late Middle Ages, it also served a similar purpose to Mardi Gras/Carnivale: a period of fasting was ordained for the day after Martinmas through Christmas, so Martinmas was your last chance to stuff your face for a long time! (This period later became Advent, though with much laxer rules). As such, it was a time for feasting, celebration, bonfires, getting really drunk, and even events such as bull-running, as in Stamford, Lincolnshire. It was also a time for the end-of-harvest tasks, such as sowing winter wheat and slaughtering pigs and cattle. An old English saying goes, "His Martinmas will come, as it does to every hog", meaning, "they will get their comeuppance" or "everyone dies someday". Due to Martin's association with geese, some celebrated with a roast goose, but in Britain particularly it was also popular to eat salted pork or beef. For those not rich enough to have a goose, a duck or hen would also suffice. Other traditional fare included black pudding, haggis, and the first wine of the season.

On the business side of things, Martinmas served as a quarter day in Scotland and in parts England. A quarter day was one of four days on which major legal business was conducted. Servants and labourers would be hired or let go, rent was paid, contracts would begin or end, &c. Hiring fairs would be held for agricultural labourers seeking employment, and there would also be entertainment, food, trading, and other scenes of merriment. One of the most famous Martinmas fairs was at Nottingham in England, which lasted eight days.

Like many other English holidays, there is weather folklore associated with Martinmas. To have a warm fall and winter is to have a "St. Martin's Summer". If Martinmas proves an icy day, Christmas (or the rest of the winter) will be very warm. The rhyme puts it more pithily: "If the geese at Martin's Day stand on ice, they will walk in mud at Christmas".

If you stand at the back of the church and observe the congregation on Martinmas, those with a halo of light around their heads will not be alive by next Martinmas.

Interior of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, with a funky window!

The church of St. Martin-in-the-fields in Trafalgar Square in London is named after Martin. Many people commemorated there are associated with his anti-war sentiments -- these include Vera Brittain, a memoirist and pacifist; and Dick Sheppard, founder of the Peace Pledge Union. The church also supports houseless and vulnerably housed people.

The holiday gradually fell out of practice due to the English Reformation (when England split from the Catholic Church throughout the 1500s) and the Interregnum (Puritan republican government, 1649-1660). The observance of Armistice Day on the same day largely overshadowed the holiday in the UK, though many regions in Western Europe still take part in traditional festivities.

Martinmas is celebrated on 12 October in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

If You're Still Interested...

"The Life of St. Martin" by Sulpicius Severus himself! (pdf)

Pot Roast Martimas Beef Recipe by Chatsworth House

Sources

Historic UK

Wikipedia (Martin of Tours)

Wikipedia (St. Martin's Day)

Fisheaters.com

The Encyclopedia of Saints by Rosemary Ellen Guiley

"Medieval English "Martinmesse": The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival" by Martin Walsh (via jstor)

#feast day series#feast day#martinmas#st martin#martin of tours#history#cultural history#english history#british history#saints day#folk history

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mysterious 12-Sided Roman Object Found in Belgium

A fragment of a mysterious artifact known as a Roman dodecahedron has been found in Belgium.

A metal detectorist in Belgium has unearthed a fragment of a mysterious bronze artifact known as a Roman dodecahedron that is thought to be more than 1,600 years old.

More than a hundred of the puzzling objects — hollow, 12-sided geometric shells of cast metal about the size of baseballs, with large holes in each face and studs at each corner — have been discovered in Northern Europe over the past 200 years. But no one knows why or how they were used.

"There have been several hypotheses for it — some kind of a calendar, an instrument for land measurement, a scepter, etcetera — but none of them is satisfying," Guido Creemers (opens in new tab), a curator at the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren, Belgium, told Live Science in an email. "We rather think it has something to do with non-official activities like sorcery, fortune-telling and so on."

Creemers and his colleagues at the Gallo-Roman Museum were given the fragment by its finder and identified it in December. It consists of only one corner of the object with a single corner stud, but it is unmistakably part of a dodecahedron that originally measured just over 2 inches (5 centimeters) across.

Metal detectorist and amateur archaeologist Patrick Schuermans had found the fragment months earlier in a plowed field near the small town of Kortessem, in Belgium's northern Flanders region.

Creemers said the Gallo-Roman Museum already displays a complete ancient bronze dodecahedron found in 1939 just outside Tongeren's Roman city walls, and the new fragment will go on display next to it in February.

Mysterious dodecahedrons

The first Roman dodecahedron to be discovered in modern times was found in England in the 18th century, and roughly 120 have been found since then in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

It's not possible to date the metal itself, but some dodecahedrons were found buried in layers of earth that date them to between the first and fifth centuries A.D.

The mystery doesn't end there; archaeologists cannot explain the geometric artifact's function, and no written record of the dodecahedrons has ever been found.

It's possible they were used in secret for magical purposes, such as divination (telling the future), which was popular in Roman times but forbidden under Christianity, the religion of the later Roman Empire, Creemers said. "These activities were not allowed, and punishments were severe," he explained. "That is possibly why we do not find any written sources."

Several explanations for the mysterious artifacts have been suggested over the years. Initially, they were described as "mace heads" and were thought to be part of a weapon. Other ideas are that they were tools for determining the right time to plant grain (opens in new tab); that they were dice, or other objects for playing a game; and that they were instruments for measuring distance (opens in new tab), possibly for finding the right range for Roman artillery, such as ballistas.

A recent suggestion is that dodecahedrons were knitting patterns for Roman gloves.

But most archaeologists think the objects were probably used in magical rituals. The dodecahedrons have no markings indicating how they were used, as might be expected for measuring instruments, and they all have different weights and sizes, ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 inches (4 to 11 centimeters) across.

Roman dodecahedrons are also found only in the Roman Empire's northwestern areas, and many were unearthed at burial sites. These clues suggest that the cult or magical practice of using them was restricted to the "Gallo-Roman" regions — the parts of the later Roman Empire influenced by Gauls or Celts, according to Tibor Grüll (opens in new tab), a historian at the University of Pécs in Hungary who has reviewed the academic literature (opens in new tab) about dodecahedrons.

Ancient puzzle

Creemers said the dodecahedron fragment found near Kortessem could shed more light on these mysterious metal objects. Many other Roman dodecahedrons were first recognized for what they were in private or museum collections, so their archaeological context is unknown, he said.

But the location of the Kortessem fragment is well documented, he said; and subsequent archaeological investigations have revealed mural fragments at the site, indicating that it may have been a Roman villa.

A translated statement by the Flanders Heritage Agency (opens in new tab) said the fractured surfaces of the fragment indicate that the dodecahedron had been deliberately broken, possibly during a final ritual.

The location will now be monitored for further finds.

"Thanks to the correct working method of the metal detectorist, archaeologists know for the first time the exact location of a Roman dodecahedron in Flanders," the statement said. "That opens the door for further research."

By Tom Metcalfe.

#Mysterious 12-Sided Roman Object Found in Belgium#archeology#archeolgst#metal detector#metal detecting finds#roman dodecahedron#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

25 notes

·

View notes