#martinmas

Text

Feast Days: Martinmas

Anthony Van Dyck ~ "St. Martin Dividing His Cloak" (c.1618)

Happy Martinmas!

Today marks the feast day of St. Martin of Tours, who was bishop there from 371 CE until his death in 397 CE. He is the patron saint of many things, including: against poverty, against alcoholism, the poor, cavalry, Buenos Aires, quartermasters, wool-weavers, soldiers, and tailors, as well as wine growers, makers, and sellers. Whew! He must be very busy.

Keep reading for info about his life, a snitch goose, where the word 'chapel' came from, and how to tell what the weather will be like at Christmas.

His Life

Much of what we know about Martin comes from his hagiographer, Sulpicius Severus, who includes some 'artistic license' that is common in chronicles of the time, and therefore must be taken with a grain of salt.

Martin was born anywhere from 316-336 CE in Savaria, now Szombathely, Hungary. His father was a senior officer in the Roman Army, and as such was given land in northern Italy for his retirement. At the age of 10, Martin attended a Christian church against the wishes of his parents, and became interested in Christianity. Because of his father's status as a veteran, he was required to join the cavalry at 15. Dates surrounding his military service are shaky, but Severus states that, during his time stationed in Gaul, he was riding on horseback when he encountered a poor man with threadbare clothes. Having compassion on him, Martin used his sword to cut his own woolen cloak in two and gave the other half to the man. That night, Jesus Christ appeared to him in a dream, surrounded with angels and wearing half of the cloak. After this, Martin was baptised as a Christian. Though other miracles of his are recorded, this tale is the one most associated with Martin's life. It fits in with depictions of God or his angels in disguise as a beggar, traveller, &c., and is also a narrative found in many other religions and traditions. (Biblical examples include Abraham feeding the three angels in Genesis 18).

Martin dips from the army ~ fresco by Simone Martini (c.1320s)

With his new faith now firmly a part of his life, Martin decided to leave the army. Before a battle near modern-day Worms, Germany, Martin went before Emperor Julian and refused his salary, saying, "I am the soldier of Christ: it is not lawful for me to fight." They threw him in prison for this, but due to ye olde extenuating circumstances, he was released and discharged without further incident.

Martin made his way to modern-day Tours in France and declared himself a hermit, becoming a disciple and friend of Hilary of Tours. Because Christianity was Not OK™ in the Roman Empire, he and Hilary faced a lot of discrimination, including corporal punishment and exile. After converting his mother to Christianity and having numerous adventures, like living pretty much alone on an island, he and Hilary settled down in and around Poitiers, where Martin established Ligugé Abbey. It is the oldest known monastery in Europe! Martin made it his home base while he preached throughout western Gaul.

In 371 CE, the bishop of Tours died, and Martin was considered a good candidate for a successor. However, he liked living as a hermit and monk, and they resorted to tricking him into coming to Tours and then forced him to become the bishop. Legend holds that he tried to hide in a barn, but a honking goose gave him away. Hence he is the patron saint of geese, which I think is adorable. Martin proved true to his hermit ways, living very simply in huts with his monks. He established a rudimentary parish system, through which he visited different Christian communities and established monasteries. He was very determined in his efforts to convert local Pagans, as well as protect Christian institutions from unfriendly sects in the area, and in some cases he was successful. He died in 371 CE, already a venerated man. His popularity was ensured by his adoption by various French royals and by the Third Republic as a national symbol.

Martin has been portrayed by several famous artists, including Van Dyck, Peter Bruegel the Elder, and El Greco. He is usually portrayed on horseback, dividing his cloak for the poor man, though occasionally he can be seen riding a donkey. This references another story in his life about the time where he met the Devil and outwitted him. It also connects him to the image of Jesus riding a donkey into Jerusalem (recounted in Mark 1:1-11).

Martinmas and its Traditions

Martin lent his legacy to a host of English words and phrases, including those relating to the word 'chapel'. Temporary buildings that held the relic of his cloak (cappa in Latin) were referred to as cappella, and hence the word 'chapel' was born. A similar thing happened to the word 'chaplain', which derived from the word for the priest in charge of the cloak.

Though the Anglo-Saxon church did celebrate St. Martin to some extent, more references to Martinmas celebrations begin to crop up after Norman Conquest of 1066, when the Frenchman William the Conqueror invaded England. Supposedly, he promised to build an abbey dedicated to Martin if his invasion of England was successful. William was very likely familiar with the early Mediaeval association of the battle-hungry rulers of France with St. Martin, and was possibly responsible for his increased popularity in England.

In England and Scotland, and indeed through much of western Europe, Martinmas became a celebration marking the culmination of the harvest and the beginning of winter. From the late fourth century through the late Middle Ages, it also served a similar purpose to Mardi Gras/Carnivale: a period of fasting was ordained for the day after Martinmas through Christmas, so Martinmas was your last chance to stuff your face for a long time! (This period later became Advent, though with much laxer rules). As such, it was a time for feasting, celebration, bonfires, getting really drunk, and even events such as bull-running, as in Stamford, Lincolnshire. It was also a time for the end-of-harvest tasks, such as sowing winter wheat and slaughtering pigs and cattle. An old English saying goes, "His Martinmas will come, as it does to every hog", meaning, "they will get their comeuppance" or "everyone dies someday". Due to Martin's association with geese, some celebrated with a roast goose, but in Britain particularly it was also popular to eat salted pork or beef. For those not rich enough to have a goose, a duck or hen would also suffice. Other traditional fare included black pudding, haggis, and the first wine of the season.

On the business side of things, Martinmas served as a quarter day in Scotland and in parts England. A quarter day was one of four days on which major legal business was conducted. Servants and labourers would be hired or let go, rent was paid, contracts would begin or end, &c. Hiring fairs would be held for agricultural labourers seeking employment, and there would also be entertainment, food, trading, and other scenes of merriment. One of the most famous Martinmas fairs was at Nottingham in England, which lasted eight days.

Like many other English holidays, there is weather folklore associated with Martinmas. To have a warm fall and winter is to have a "St. Martin's Summer". If Martinmas proves an icy day, Christmas (or the rest of the winter) will be very warm. The rhyme puts it more pithily: "If the geese at Martin's Day stand on ice, they will walk in mud at Christmas".

If you stand at the back of the church and observe the congregation on Martinmas, those with a halo of light around their heads will not be alive by next Martinmas.

Interior of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, with a funky window!

The church of St. Martin-in-the-fields in Trafalgar Square in London is named after Martin. Many people commemorated there are associated with his anti-war sentiments -- these include Vera Brittain, a memoirist and pacifist; and Dick Sheppard, founder of the Peace Pledge Union. The church also supports houseless and vulnerably housed people.

The holiday gradually fell out of practice due to the English Reformation (when England split from the Catholic Church throughout the 1500s) and the Interregnum (Puritan republican government, 1649-1660). The observance of Armistice Day on the same day largely overshadowed the holiday in the UK, though many regions in Western Europe still take part in traditional festivities.

Martinmas is celebrated on 12 October in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

If You're Still Interested...

"The Life of St. Martin" by Sulpicius Severus himself! (pdf)

Pot Roast Martimas Beef Recipe by Chatsworth House

Sources

Historic UK

Wikipedia (Martin of Tours)

Wikipedia (St. Martin's Day)

Fisheaters.com

The Encyclopedia of Saints by Rosemary Ellen Guiley

"Medieval English "Martinmesse": The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival" by Martin Walsh (via jstor)

#feast day series#feast day#martinmas#st martin#martin of tours#history#cultural history#english history#british history#saints day#folk history

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

11th November

Martinmas

Source: The Enchanted World, The Book of Christmas, Time-Life Books

Today is Martinmas or St Martin’s Day. Martin was a fourth century saint allocated to the traditional feast day of the Roman god of wine, a debauched character called Bacchus. This probably explains the copious amount of ale and wine traditionally drunk at Martinmas and the legend that Martin could cure drunkenness. He was also the patron saint of vintners. Martin also became associated with the transition from autumn to winter. At Martinmas, in commemoration of Martin’s alleged death after being gored by a bull, cattle were slaughtered in large numbers, which in actual fact was probably a holy connection with the necessary practice of laying down salted beef to help the peasantry survive the hard medieval winters. Martin was also supposed to have given away his cloak to a beggar shivering in the winter cold. This tradition is behind the belief that on his feast day, St Martin can be seen on horseback riding across the fields and meadows bringing the first snow of winter billowing out from the folds of his cloak.

Most Martinmas traditions have been replaced by the sombre commemoration of Armistice Day in the U.K., when wreaths are laid at the Cenotaph in memory of the British dead of the two World Wars and later conflicts. The Last Post is sounded at the ceremony and a two minute silence is observed from 11am. The Armistice that effectively ended the First World War was signed at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autumn feasts of France: La Saint-Martin

From "L'inventaire des fêtes de France d'hier et aujourd'hui"

La Saint-Martin (in English Martinmas), celebrated on the 11th of November, used to mark the end of the agricultural work and the beginning of winter in Europe. On this day, there were autumn fairs in the countryside. A thanksgiving mass was organized, followed by a heavy meal centered around a goose dish. It was during this meal that the new wine was tasted (in France there was a verb based on Martin's name, meaning "to drink the new wine": "martiner"). Just like Halloween, another celebration of this time period, Saint-Martin was, in northern France and in Germany, a day during which groups of children with lanterns walked around the town, to conjure away the dangers of the days shortening. Nowadays, the 11th of November is the day of the 1918 Armistice.

Saint Martin (the person) was famous all across Europe, and gave his name to numerous villages. More than three thousand churches and chapels in France are dedicated to him. Born in 316 in Pannonia (current Hungary), saint Martin was part of the Roman army. A famous episode of his life is how he split his coat in two, to share it with a poor man who was cold, near Amiens (in the Somme region). The following night, he dreamed that the man was actually the Christ in disguise. Converted to Christianity, he was baptized in 356 and became priest under the bishop of Poitiers, saint Hilaire. Martin founded the Ligugé abbey (in Vienna) and was elected bishop of Tours in 372. He died at Candes (Indres-et-Loire region) in 397 - his grave is still a very popular place of pilgrimage.

Martinmas was a celebration surrounded by numerous autumn traditions, and evoking the fact that the granaries and cellars were full. For example, a thanksgiving meal was organized to thank God for the harvest (or, in more pagan ways, to celebrate the harvest god). This tradition was maintained in America with the Thanksgiving celebration - when American families gather on the last Thursday of November to eat a turkey. In Dunkerque, the evening of Martinmas, children organized a procession, holding lanterns while walking behind saint Martin riding his donkey. According to the legend, children were rewarded for finding back the lost donkey of the saint - said reward took the form of pastries placed during the night on the doorway of houses, and known as "donkey poop".

#autumn celebrations#autumn feasts#saint martin#martinmas#french folklore#european folklore#french holidays#french celebrations#france

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have nothing to show for Martinmas except my Wild Hunt candle from @wildbeautycandles and the strong feelings of gender in the second photo. I prayed to the wilds, pulled cards, danced, made trecks to visit old trees and haunted places for today. Nothing which I originally planned for Martinmas but certainly felt the most appropriate given it's my first year incorporating it into my practice as part of the patronage of the Wild Lord.

May The Animals have enough to eat, may The Wild Hunt move freely and cause us no harm, and may The Beasts we tend both inside and out brace against the coming winter.

#folk magic#the wild hunt#martinmas#divine androgyne#devotionals#lord of wolves#him#traditional withcraft

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am not a particular devotee of St. Martin, but I had a special favor to ask, so I made a special offering for his feast day: wine, cheese, nuts, and homemade dulce de membrillo made from fallen quinces. the dulce de membrillo didn't come out the reddish color i prefer because the quinces people plant here don't have the right tannins required to make the flesh change color when cooked. anyway, wine and cheese for the wine saint (over matters related to wine) felt appropriate!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I choose the name Martín, I didn't looked onto the saints with this name. But when I read about Martinmas on @graveyarddirt tumblr casually, I got to look, both San Martín Caballero and Martín de Porres and fuuuuuuuuck, everything fell on place.

Me, after 4 years looking for the right name and "choosing" Martín less than 24 hours after thinking in this name, discovering about San Martín:

I have this belief that sometimes, a name is not exactly chosen, but given. My son have a very neutral name, and since he is 17, I explained that if he wants to change his name, it's his right. (we got some good laws about it recently).

Because names have power, and names are signs. Signs about who is you, and what is your place in the world.

(sometimes it's just a stupid adult shit choice, and that's how people end with other names, or with nicknames and alias that totally substitute their law names)

But Saint Martín has so much connections with my practices and world visions.

( that I'm totally the person that will hide in a goose pen to avoid been bishop is already the joke in my house about why I got so moved by figuring this San Martín situation)

And today found me making preparations to my first Martinmas/ Dia de San Martín Caballero, reading about his celebrations across the world, and loving every minute of it.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Original here

#martinmas#st martin's day#laterns#st martin#has that little one something hanging out of their mouth?#must be a good festival then :)#aww i also want to goooo#this one is in#dormagen#germany#culture#tradition

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘If ducks do slide at Martinmas

At Christmas they will swim;

If ducks do swim at Martinmas

At Christmas they will slide’

‘Ice before Martinmas,

Enough to bear a duck.

The rest of winter,

Is sure to be but muck!’

‘If the geese at Martin’s Day stand on ice, they will walk in mud at Christmas’

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the tangled roots of Hallowe'en...

I've noticed a ten-year-old Washington Post article making the rounds again. It theorises that British colonialism determines whether or not other countries celebrate Hallowe'en. While the timing of various waves of colonisation and immigration (and for one thing, it seems important not to treat those as identical) from Britain can often be used to trace certain cultural or linguistic patterns, with Hallowe'en, the story is a bit more convoluted than is often thought.

The ways in which Hallowe'en has spread and changed over the centuries can't be understood through just ones lens. It needs the context of other autumn and winter calendar customs, the agricultural year, the Reformation, and - especially over time - the urban/rural divide.

Let's take a deep dive...

The author seems to assume that the Hallowe'en chaos (and associated crackdowns) in parts of the US in the 19th century also occurred in Victorian Britain, and then makes the further assumption that English immigration during a resulting period of Hallowe'en not being celebrated in England is the reason for its absence in places Britain colonised at that time.

Aside from the fact that 19th century migration from Britain to the US took place in a very different context from the centuries-earlier colonisation by Britain, this seems to illustrate the pitfalls of applying the term "Victorian" to countries where Victoria was not actually Queen, and people didn't identify as Victorians, any more than Americans in 2023 would call themselves "Carolingians" on the grounds of existing while Charles III is on the throne in the UK.

In Victorian England, there was no big pushback against Hallowe'en - that would've been out of step with the spirit of the age. The Victorians lived in the century when the word "folklore" was coined, after all, and there was huge interest in cataloguing and preserving traditions, most famously those of Christmas, which by 1810 had declined, before being rehabilitated by antiquarians and given new life, above all, by Charles Dickens. The Victorians half-reconstructed, half-invented an idea of Christmas in much the same way that that we have ransacked history, folklore, fiction and commerce for Hallowe'en customs of yore in the hope of celebrating it in its ideal form.

Even if England in the 19th century had been on some perverse mission to bury Hallowe'en, there was little enough left to bury. It had for some time been in decline in most parts of England for a variety of reasons, notably the Protestant Reformation that began in the 16th century, but also the shifting of various Hallowe'en customs (notably bonfires) to Guy Fawkes Night on 5th November in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot.

The Protestant/Catholic distinction is significant because Allhallowtide - the period encompassing All Hallows' Eve on 31st October, All Saints' Day on 1st November, and All Souls' Day on 2nd November - was a Catholic tradition. And in rural Ireland, where Catholicism remained strong - and unsurprisingly, Guy Fawkes Night was not a folk celebration - the old tradition of bonfires remained attached to Hallowe'en. So the popularity of Hallowe'en in the US and Canada has less to do with what the English who settled there in the 19th century weren't doing, than it does with what Irish and Scottish settlers at the time were doing - they came from cultures in which Hallowe'en traditions remained strong.

This is particularly obvious when you read accounts of late 19th century and early 20th century Hallowe'en parties in the US, which combined aspects of the harvest home tradition (which had deep roots in Britain and Ireland) with the custom - strong in Ireland and Scotland - of divination rituals related to who you would marry and which relationships would succeed or fail. Women's magazines of the time, in their advice for hostesses, drew strongly on those traditions. In their focus on sweethearts and romantic divination, the party ideas may strike modern readers as evoking Valentine's Day rather than spooky season.

This was much more encouraged than the wilder aspects of the day. On the scale of small, rural Irish communities where everyone knew each other, Hallowe'en pranks had their place - and usually, reasonable limits. You could disassemble the village curmudgeon's cart and then reassemble it, donkey and all, in his farmhouse kitchen, but you knew nobody would be laughing if you burned his house down. And the goodwill (however strained) with which villagers tolerated absurd pranks by their neighbours' sons did not translate to city contexts, where large groups of youths engaging in higher-stakes pranks and vandalism caused real harm and real fear. It's this expression of Hallowe'en traditions that was attracting pushback in the 19th century - just not in England.

The Washington Post article cites this Quartz map to further its claims. The logic is supposed to be that countries which today have a bump in sweet imports in October must celebrate Hallowe'en. But it's a weak argument, as many of those countries - notably those in continental Europe - did not see large-scale, culture-changing British immigration in the 19th century, But they do have their own centuries-old traditions of children going from door to door - perhaps disguised, perhaps rhyming, sometimes with lanterns and often begging for sweets by way of a song.

These range from Pão-por-Deus, a souling custom children perform on All Saint's Day in Portugal, to St. Martin's Day, wherein parts of Flanders and the Netherlands, and most of Germany, Switzerland and Australia, children travel from house to house with lanterns, singing in exchange for treats. The bump in sweet imports seems more likely to be due to their own homegrown traditions, combined with more recent adoption of Hallowe'en, and the tendency for major retail chains to stockpile ahead for Christmas.

And these autumnal singing/guising/begging traditions in themselves are part of a broader, older and geographically widespread tradition of guising and mumming (by adults, also), often during the darker months - one that often coalesces around Christmas or New Year (as in mummers' plays).

We think of Hallowe'en as occurring squarely in the autumn, particularly with climate change causing unaccustomed mild weather and the shops bringing out Hallowe'en products earlier and earlier. But it traditionally marked the start of winter, and it's not coincidence that St. Martin's Day, as celebrated in various parts of mainland Europe, falls on what was originally Samhain Eve.

This makes more sense when you understand that the calendar itself has changed over the centuries. In Jack Santino's book The Hallowed Eve: Dimensions of Culture in a Calendar Festival in Northern Ireland, he observes that:

"In the old Celtic calendar, November 12 was the first day of the year. The adoption of the Gregorian calendar in 1752, with its dropping of twelve days, meant that some traditions associated with November 11, Samhain Eve (later known as Old Halleve), were now observed on October 31. Hiring fairs were held on November 12 and May 12, and parties were given on Old Halleve to celebrate the end of the six-month hiring term. The tradition was also related to the potato harvest."

I'm writing this as the clock ticks from the 11th to the 12th of November, and it certainly does feel more wintry now. By this stage of the year, back in the days of the old calendar, the days would have been shorter and darker for a good while, your crops and your cattle would be safely gathered in, and whether you marked the turn of the year with Hallowe'en or St. Martin's Day, a lantern was a welcome thing in the cold and dark.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Martinmas

According to an old Huntingdonshire proverb, a north west wind on Martinmas was a sign of a severe winter to come. Another thing to look for on this day which predicts a severe winter is the leaves still being on the trees.

10 Martinmas customs:

0 notes

Text

13th November

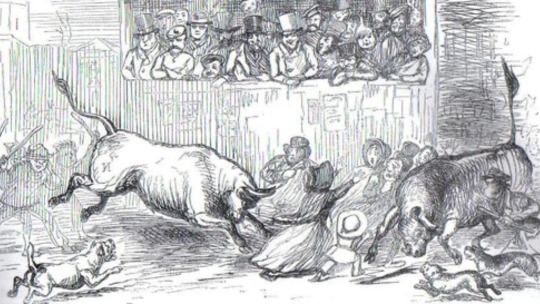

Stamford Bull Running

Source: The Lincolnite website

On this day the Stamford Bull Running once took place. Until this exercise in animal cruelty and danger to human life was banned in 1839, every 13th November a bull was hounded through the streets of Stamford in Lincolnshire by the bullards, drivers who risked life, limb and being covered in bull dung by eventually forcing the enraged animal off the bridge and into the River Welland where it usually drowned, before it was hauled out and butchered for a mass collective night feast. The ritual originally began, tradition has it, when William the Earl of Warren observed two rogue bulls devastating his lands and hired local butchers to chase them down, during which one of the animals stampeded through Stamford. There may be truth in this tale, but the event’s accompanying folk songs and the general orgiastic glee on display at the Stamford Bull Run, hint at a darker origin in Martinmas pagan bull sacrifice. The general feel of primitive license and excess associated with the Run was summed up by a bullard’s speech in which he insisted:

‘On this day there is no King in Stamford, we are every one of us high and mighty… a Lord Paramount, a Lord of Misrule, a King of Stamford… We are punishable for no crime but murder, and that only of our own and no other species.’

No mercy for the bull, then.

0 notes

Photo

In many parts of Germany it is traditional for children to participate in a procession of paper lanterns in remembrance of St. Martin. They make their own little lanterns in school or kindergarten and then gather on city streets to sing songs about good old Marty and their lanterns.

Art: http://astampaday.blogspot.com/2013/11/sinte-maarten.html

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have decided i am not someone who does summer holidays. it's too hot and when it isn't Danger Heat i'm working. i will instead be taking a solid two months for yule, maybe more who knows

#maybe yule begins at martinmas and ends and candlemas who's gonna stop me the cops????#anyway happy lammas to people who aren't sweating to death#babbles

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rolf Dieter Meyer-Wiegand (German, 1929-2006) - Martinmas

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today (Nov. 11th) is Martinmas, the feast of St Martin of Tours, an important festival in medieval Europe on the very cusp of winter.

A 4th century Pannonian (present day Hungary) soldier, Martin's conversion to Christianity led him to give up his life in the Roman army. As Bishop of Tours he founded the famous abbey of Marmoutiers. Well known for his charity, here St. Martin is depicted cutting his cloak in half to share with a beggar.

Today he is venerated in the church as the patron saint of the poor, soldiers and conscientious objectors.

(Source: BnF NAF 16251: Images de la vie du Christ et des saints. 13th century (c. 1280-1290); f.89r)

163 notes

·

View notes