Note

why does theatre provide insights into the past? sorry if this is obvious

(re: this post)

so I’m mostly jumping off of Edith Hall, who talks in the intro to her book suffering under the sun about how greek drama is located in the distant (mythical) past and treats stories and characters that were familiar to the audience despite their temporal distance and says “greek tragedy therefore involved a form of communal ghost raising— bringing famous but long-dead figures back to life”. (I think this holds true for the Persians as well even though Xerxes was still alive when it was produced, since it quite literally resurrects the ghost of Darius on stage, but it’s also more generally about people and events that live on in athenian collective memory despite temporal and physical distance.) everyone gets together at the theatre to remember the past together by watching the past enacted on the stage. That all becomes a lot more vivid when actual ghosts appear on stage (clytemnestra in the Eumenides, Darius in the Persians).

I think this holds true for theatre more generally, not just greek tragedy. Partly because of how many plays are still set in the past, but mostly because everything you see on stage has been acted out before, rehearsed before, performed before, written before. Theatre is a repetition of what has already happened and what has already been determined. Its purpose is to play that out again in a way that makes sense and to make it possible to understand what has happened. Theatre puts it into the structure of narrative, and narrative is a way of making sense of things.

I talked some about it on this post

I have yet to read Marvin Carlson’s the haunted stage: the theatre as memory machine but a couple of the articles I read about the oresteia cited it to talk about production history and how the theatre is also filled with the ghosts of every production that has ever taken place there and damn. That’s something. The articles I read pointed mostly to aeschylus’s agamemnon (both the character and the play) haunting sophocles and euripides’s plays on the house of Atreus which is SUPER cool.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

98K notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes

okay strictly speaking “necromancy” is specifically the raising of the dead for the purpose of divining the future (νεκρός/dead + μαντεία/prophecy, same root as bibliomancy or arithmancy), so theatre is therefore… reverse necromancy??? the raising of the dead for the purpose of gaining insight into the past???

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s two ends of the horror spectrum

96K notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell me more about mavka and what her deal is? She reminds me of Scandinavian huldra from thr little I've heard and I'd love to learn more about her!:D

hello friend. a mavka, navka or nyavka is an undead forest spirit, one of type which ukrainians call the covered dead (заложні мерці) — spirits of people that died of unclean, improper death, and therefore couldn't finish the transition and weren't allowed to the orherworld. the name covered undead comes from the fact that in old times they weren't properly buried, and were left in forests covered by leaves and twigs.

generally mavky are envisioned as beautiful girls, although in some regions there are beliefs about male mavky (sometimes called didky). mavka looks perfectly human except for the fact that their backs lack skin and muscle, exposing their innards and spine. they aren't malicious, but are obliviously playful and can hurt people during their plays — tickle or dance you to death, drown, ward you off your tray. in some western regions it's also believed that time goes faster when encountering them — what is felt like several hours could actually be several hundred years.

navky live in forests and mountain caves, and they like to dance, weave, play and prank wanderers, especially young men. to ward off mavky valeriana, garlic and wormwood are used, as well as wearing your shirt inside out. like most undead spirits in ukrainian mythology, navky are most active during the green festival/rusalka week.

there is a ukrainian holiday called navsky velykden, or undead easter, celebrated at the first thursday after easter. in this day all mavky, rusalky, upyri and all the other unclean forces celebrate easter. at night during the holiday it was prohibited to visit churches, since celebrating undead could dismember you if spotted.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

And a last one for the road

Romanian witches: Baba Dochia

Originally I wanted to talk about only one "Romanian hag" from the world of fairytales, but from this one entity I ended up talking about Muma Padurii and Baba Cloantza and many more... Because there is never just one "baba" or one "muma" in Romania. There is a whole series of malevolent hags and magical old women which all embody in one way or another the benevolent, malevolent, or neutral aspects of the archetypal Romanian witch.

I will mention that Wikipedia lists the Muma Padurii/Baba Cloantza in her wicked form as one of the three recurring fairytale villains in Romanian fairytales, alongside the "balaur" (the "dragon", a winged multi-headed evil snake that comes in three variations 1) air-dragon that causes/lives in storms 2) earth-dragon living in chasms and pits and associated with gems 3) water-dragon, usually killed by the saint - see the legend of saint Georges) and the "Zmeu" (Zmei in plural, the Romanian variation of the Slavic creature of the same name, usually a giant sorcerer but which sometimes appear as a dragon)

But now I finally reach the witch I originally wanted to talk about. Baba Dochia. I learned at first about her when looking at an article which covered the Romanian translations of the brothers Grimm "Frau Holle", and this article evoked how in Romanian translations, often the legendary character of Frau Holle was replaced by a Romanian folkloric being: Baba Dochia (which the article did compare to the Baba Cloantza as an aspect of the "fairytale wicked witch"). With the bonus that the Baba Dochia is closely linked to the weather and to seasonal changes, which explains why she can fit the role of Frau Holle.

Here is what the article had to say about the Baba Dochia.

She is one of the many supernatural "babas" of Romanian legends (remember, "baba" simply means "old woman", the same way the German "Frau" means "lady" or "miss"). Baba Dochia ha, like Frau Holle a weather role - Baba Dochia is a manifestation of the cold weather and the winter season. Or, to be more precise, Baba Dochia is only a manifestation of the end of winter. The whole thing of Baba Dochia is that her "weather role" takes places during the beginning of March, a set of nine days that are typically called the "babele" (plural of Baba). This era marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring - a shift of seasons usually symbolized as a fight between two entities. Baba Dochia is supposed to wear nine "cojoace" (coats made of sheep's skin), representing how cold the weather is. During these nine days, when the weather is violent, unpredictable and constantly-shifting, Baba Dochia will remove each of her coats, one per day - and the more coats the take off, the hotter the air becomes and the more snow melts. In fairytales, this "seasonal battle" usually has the spring season symbolized by the "prince Charming" figure.

This is the case of a specific Romanian fairytale that is an equivalent of the Grimm's "The three little men in the woods". In this fairytale the Baba Dochia is a wicked stepmother that sends her martyrized stepdaughter to a frozen stream, to wash black wool until it becomes white. The stepdaughter encounters a beautiful young man named Martisor (I am not adding the accents here because my keyboard is not equiped for it) who embodies spring: not only does he help the girl, he also gives her flowers (we are in winter). When the stepdaughter returns she manages to get her accused of cheating on her husband (because after all you know, she accepted the flowers of a handsome stranger in the woods... It can look bad in an old countryside society) ; but these flowers will cause Dochia's downfall. She believes these flowers mean spring is here (when in fact it is still winter), as such she goes to the mountain with her sheep as she does every spring... but she just ends up frozen to death there, and all her sheep with her. This folktale is tied to the rocky landscape of several mountains - a type of mineral manifestation called "Babele" and which is supposed to be Baba Dochia and her sheep, petrified into stone.

Baba Dochia also appeared in the works of Mihail Sadoveanu, but this author decided to reinvent the character as a less wicked and more tragic character. In his own take on the story of Martisor, Dochia isn't the wickedness of a cruel season that needs to end ; but rather she suffers from the deep gap between the human world and the "otherworld". Otherworld that Baba Dochia represents: she is a witch-like old woman with obscure powers and a shadowy domain, living all alone in a little cabin at the top of the mountain, isolated from all civilization. One day, she adopts a young orphan girl and she raises her with love - but away from all other human presence. The young girl, who is a plain human unlike the otherwordly Baba Dochia, cannot resist her roots, and demands to be allowed to return into humans, in the light-filled world of the valley. Baba Dochia agrees to let her go there to see the humans - but in the valley, the girl falls in love with the titular Martisor and forgets to return to her adoptive mother. The old woman, alone and heartbroken, ends up freezing to death in the coldness of her little dark cabin.

This was all I could get from the article. To this I will add info from a little brief Internet research:

An alternate name of Baba Dochia in Bulgaria and Macedonia is Baba Marta, in reference to the spring celebrations of the first of March, Martenitsi, Bulgarian name of the Romanian Martisoare, from which the "prince" Martisor gets his name. Baba Dochia can also be found under this name in Moldavia on top of Romania. In English a translation is "Old Dokia".

A variation of the "babele" name described above: the fifteen first days of March can be called the "zilele babei" (the days of the old woman) (babei/baba refering to the old woman, the herb-healer and the female witch)

There are actually many versions of the fairytale I described above:

First version: Baba Dochia had a son, Dragobete in Romanian, Dragomir in Bulgarian, who married a young girl against his mother's will. Dochia abuses her daughter-in-law and at the end of February sends her to fetch berries in the woods. She is helped by an old man, who is actually God in disguise and produces the berries by a miracle. When Baba Dochia/Marta sees the berries, she believes spring is here, puts on twelve sheep-skins as coats and goes to the mountain with her son and sheep. But due to the rain her coats get soaked and heavy - so she removes them, but the frost suddenly arrives and freezes her to death, with her ship, and her son who was playing the flute.

Second variation: Pretty similar to the first, with a few details changed. There are only nine coats instead of twelve, and the Baba removes them due to the hot weather before the frost suddenly arrives. Her son doesn't go with her to the mountain. The girl isn't elped by God but by the Virgin Mary or a female saint. The girl is precisely asked to go fetch strawberries. And here the Baba and her sheep don't just freeze to death, they are petrified into the "babele" stones found in the mountains.

Third version: The baba sends her daughter-in-law to the river in winter to clean a very dirty coat until it gets white and shining, but the girl fails to do so and cries. A mysterious man arrives and gives her a snowdrop flower which makes the coat white by magic. When the girl returns with the white coat and the flower in her hair, baba Dochia believes spring is here - and she ends up like in the previous tales, frozen/petrified on the mountain.

Fourth version: Again, Dragobete marries a woman against his mother's will, so the baba Dochia abuses her, and notably sends her wash black wool in a stream until it becomes white (an impossible task). The baba specifically forbids her from returning until the wool is white, and since the girl can only freeze her hands in the cold water she cries about losing her husband (that she loves very much). Jesus then appears and offers her a red flower which makes the wool white. When the girl returns Baba Dochia believes springtime came since a man could pick up a flower - and you know the rest, she goes to the mountain with her nine coats, due to the weather she drops them one by one, and when she gets rid of the last everything suddenly turns cold and she freezes to death. (There's a fifth version which is just this story but with twelve coats instead of nine)

Outside of pure fairytales, if we go more into the folklore and myths, scholars debate the possible origins of the Baba Dochia/Baba Marta. Some believe she might be a character born of the old name of Dacia (Dakia in Latin and medieval Greek, close to "Dochia/Dokia"). Others believe she might have evolved from a Byzantine celebration Eudoxia/Eudokia's martyr on the 1st of March. A third theory is that she is the leftover of an ancient Thracian goddess common to the Romanian and Bulgarian territories, a deity of agriculture, fertility, renewal... But all in all the Baba Dochia/Marta was seen as a weather spirit with a quickly-changing mind and unstable temper, and as a result needed to be appeased with offerings. Only by these gifts will she make sure winter doesn't last too long and spring returns (while in fairytales it turned into the Dochia's death causing the triumph of spring). A folkloric ritual consists of leaving the offerings by fruit-trees or under rocks, and if they are left under rocks, people then look which kind of insect live or takes refuge there. Depending on whether it is a millipede, a spider, a cockroach or any other thing, it will form an omen about how the year to come will unfold, turning the Dochia offering into a divination ritual.

But as I said before, the baba Dochia was mostly seen as a negative entity - it was said she was a spirit of the bad weather who during the nine "babele" (the nine first days of March during which she removes her nine coats) brought snowstorms and cold winds. Another divination ritual had a woman pick up randomly one of the nine babele-days: if the day turns out to be good weather, they are promised to stay fair and nice in their old days ; if the day has bad weather, it means they will age into a bitter hag. There's a lot of proverbs and sayings tied to the weather and Dochia - which makes her similar to the German Frau Holle. Of course when people say "Baba Dochia removes one of her coats", it means the weather is very warm ; but when it snows people also say "Baba Dochia is shaking her coat".

The Baba Dochia also appears in a little story that is told all the way across Europe (I know this because just a few days ago I read a variation of it among fairytales of Bretagne). The story always goes the same: there is an arrogant or wicked old woman/shepherdess who for a reason or another mocks or threatens the month of March (here a sentient entity), who in revenge steals some days from February to come earlier punish the old lady. In Romanian this old lady is Baba Dochia.

There is also a very WEIRD pseudo-historical legend which tries to explain Baba Dochia as having been a person from the Antique history of the land... According to this tale, Dochia was related to the last Dacian king, Decebalus (she was his sister for some, his daughter for others). When the Roman emperor Trajan conquered the Dacians, Dochia fled into the Carpathian mountains because Trajan wanted to marry her. She disguised herself as a shepherd, and all her servants and followers disguised themselves as sheep. But Trajan kept pursuing her and sending his forces after her, so in despair she prayed to the Dacian god Zalmoxis, who turned her and her fake-sheep into the Babele stones we can still see today. Quite a strange story, heh?

There's also a Christianized, benevolent version of the Baba Dochia - because of course, Christianity is VERY strong in Romania and gets its hands onto every folkloric character it can (this is why in the Baba Dochia fairytales the Martisor-Prince Spring figure gets so often replaced by Jesus). In this sanitized, Christianized version, baba Dochia was a pious old woman whose prayers for winter to end brought spring... Quite a far move from the wicked stepmother.

As a last note: Baba Dochia's son, Dragobete, also plays a part in the "weather symbolism/calendar meaning" of the fairytale. Because while Martisor is the beginning of spring and Baba Dochia the end of winter, Dragobete is actually an old Romanian god of love (often called the Romanian Eros/Cupid) who is celebrated during the "Dragobetele" celebrations on the 14th of February... The Romanian Saint Valentine's day. Dragobete was called in old pagan traditions "he who bets on love" and "the godfather of animals", because he protected and blessed all couples upon his day - as such, you had a sort of human "Saint Valentine" celebration on his feast-day, but you also had an homage to what was believed to be the "engagement of birds". There's a whole set of traditions and legends surrounding this which I will not expand upon here, but it makes sense than that this spirit of the love-day of February is symbolized as the loving husband of the heroine and the son of the hag of the end of February...

#self reblog#baba dochia#romanian witches#romanian folktales#romanian legends#romanian fairytales#witches#legendary witches#seasonal myth#weather#weather legends

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continuing my self-reblogs: after the Forest Mother, the Romanian "cousin" of Baba-Yaga (though not just a translated Baba Yaga was some like to claim... Come on guys, respect that each country has its own thing, especially in Romania where there's so much witch-lore and cool witchy figures)

Romanian witches: Baba Cloantza

Last time I talked about Muma Padurii, the Forest Mom. And I promised you Baba Cloantza...

The whole idea of the Baba Cloantza is quite fascinating. When I read the article about the Romanian translations of Frau Holle which prompted me to do this series about Romanian witches (I'll talk more about this in the third part of the series), they evoked Baba Cloanta (yes, without the "z") as the traditional wicked witch and child-eating hag of Romanian fairytales. If you do research about Muma Padurii as I did before, you will sometimes find that "Baba Cloanta" can be an alternate name or identity for the Muma, especially in her "creepy wicked witch eating children soup" fairytale self. But if you research Baba Cloanta/Cloantza on her own, most of the time all you'll find is a mention saying "Baba Cloantza is the Romanian name of Baba-Yaga" or "Baba Cloanta is the Romanian equivalent of the famous Russian witch / she is the Carpathian Baba-Yaga".

Now... I do understand why everybody loves Baba Yaga, but I also understand why having Baba Yaga everywhere can be a problem. There is a reasoning behind saying "Baba-Yaga is a character present throughout all Slavic fairytales" and "Baba Yaga is a character of Eastern Europe fairytales"... But this oversimplification can cause a problem when it sweeps under the rug national "cousins" of the Baba Yaga. Again, remember that the Baba Yaga we know today was defined and shaped by Afanassiev's Russian Folktales... It is a specifically Russian character. Yes she does answer to and manifests an archetype present throughout Eastern Europe, and you have several Eastern European manifestations of a local Baba-Yaga... But then you have characters like Baba Cloantza. Who is indeed an equivalent to the Russian Baba Yaga... But she is still her own character, a specific Romanian entity, and saying she is just "Baba Yaga with a different name" can be a quite problematic claim...

So today I invite you to discover Baba Cloantza, a Romanian witch which yes, can be the Romanian translation of "Baba Yaga", but is also an alternate identity of Muma Padurii, as well as her own character with specific roots in Romanian folklore.

For this post I will rely onto an article written in French by Simona Ferent, "Baba Cloantza, la Yaga édentée" (Baba Cloantza, the Toothless Yaga) - it was published as part of a collection of studies and articles around the figure of Baba Yaga for a Sciences and Literature journal (it was called "Baba Yaga en chair et en os", "Baba Yaga in flesh and bone"). I literaly translated the article a long time ago and I do regret doing so because it might have made it quite unreadable... But if you can read French go check it out because it is one of the most complete resources I could find about Baba Cloantza online.

It is also because of this article that I write Baba Cloantza instead of "Cloanta", which Ferent highlighted as a better transliteration of the Romanian Cloanţa.

Baba Cloantza is one of the central witches of Romanian fairytales, and a well-known figure of the Carpathian folklore. But there is already a difference established between her and the Russian Baba-Yaga by her very name. Indeed "Cloantza" means an old woman, an ugly woman... a toothless woman. Hence the name of the article, "the toothless Yaga". Not only does this name evokes as such a toothless hag, it also insists upon her mouth, because "cloantza" is a pejorative name for a mouth. So the Baba Cloantza is a figure associated with the mouth - as much the decrepit toothless hole of an old ugly woman, as the devouring maw of the fairytale monster... and as the mouth from which ancient wisdom and magical secrets comes from. She is the "frightening wisdom", as Ferent says. Because, as a "baba", she is this ambiguous figure between the demon in human shape and the spiritual guide: the baba is the witch and the wise-woman, the isolated and lonely old woman that lives outside of the village, near or into the woods, the one who holds power over love, healing, divination and the weather... As such in fairytales she is the monster to fight and avoid, as much as the magical woman that will help the hero in his fight against a supernatural power, guide a lost traveller, or assist a woman with a tragic love story.

Ferent's article covers a wide range of sources and domains, as a testimony of the Baba Cloantza's huge presence in Romanian culture. The works of Vasile Alecsandri, where she is a prophet, a healer and a demon ; the ones of George Coşbuc where she is a leftover of an ancient Dacian goddess ; the modern, caricatural, buffoon-like depictions of Tudor Arghezi and Gelu Vlaşin ; and finally the great and iconic fairytale collections of Romania, those of Petre Ispirescu and Ion Creange, where the Baba Cloantza is a needed element within the hero's initiation and journey into the world/otherworld...

Given there is a lot of info, I will put this under a cut.

Simona Ferent identifies seven "faces" or seven "aspects" of the figure of the Baba Cloantza.

First, the Cloantza as the "village's oracle". In 1843, Vasile Alecsandri created a poem called "Kraiu-Nou" taking inspiration from the folktales surrounding the Sburător, a night-haunting supernatural entity embodying the "malevolent seduction", a sort of vampire preying upon sleeping women. This works depicts a countryside dominated by the moon - the "Kraiu-Nou" itself corresponds to the first phase of the moon, which is the most effective moment to formulate wishes (especially love wishes). The story describes Zamfira, which is a Romantic incarnation of the "beautiful, virgin, Romanian peasant girl", whi makes her own love wishes to the moon and becomes the prey of the Sburător. In this story, Baba Cloantza appears as a wise-woman who warns the girl of the danger that threatens her. She performs a divination ritual by looking into forty-one grains of corn, and by doing so she tells him she must flee a beautiful stranger with a soft voice (the vampire). [The poem notably opposes the frightful prediction of the baba with the predictions of the "wise men" and elders of the village who said Zamfira would have a happy life] The Cloantza even appears on a sort of mount that later turns out to be the very grave of the vampire... But despite all those warnings, Zamfira follows the eroticism and charms of the mysterious "lover of the shadows", who ends up stealing her life-force... Here Baba Cloantza is still the "old woman at the limit of the village", the physical margin of the community, and her role as an oracle highlights her ambiguity as the one who warns of the danger, but seems to cause it, since her prophecy is self-fulfilling. She is the first to mention the vampire before it appears, and she sits on what seems to be its grave... She tries to scare the girl away from the monster, but the way she describes him makes him appear seducing and conjures up the first fantasies of romance within Zamfira. As such, the baba Cloantza warns the girl of her doom... while throwing her (accidentaly?) in the arms of her killer. (There is also a whole thing to say about how the first crescent of the moon is strongly associated with the manifestation of ghosts and the apparition of malevolent beings ; and how the baba Cloantza embodies here an archetypal fear and archaic warning of sexuality, that the vampire embodies, as the one who preys upon the pure virgin girl...)

Second, the Cloantza as the "healer". In the folk-poem "Burueana de leac" ("the weed that heals"), we have a traditional depiction of the peasant man adressing a prayer/request to the village baba - in this case, we have the story of a man in love in such a desperate way he is ready to curse. The man, overtaken by a desire that strongly looks like a demonic possession (there are motifs of the extinguished sun , and the grave calling for the man), calls for the "mama Ileana", the only one able to "put out the fire" of his heart. The folklorist Alecsdandri explained that "mother Ileana" is another name for the "village baba" - more specifically it is the name of the healer of Romanian villages, who uses both plants and magical words, and bases her craft on the various times of the folk-calendar which mixes Christian celebrations with pagan feasts. This is all the ambiguity of this specific baba. On one side she refers to the Christian religiousness: she uses religious icons, the village's church, she sings in honor of the Virgin Mary or of God... On the other, her rituals are distinctively pagan: she uses flowers and weeds, she carries a supposedly magical water, her incantations are said to be "witchcraft" and she uses wands made of hazel-tree...

Third, the Cloantza as a caricature. The Romanian poets heavily relied on the figure of baba as the "village healer" - Tudor Arghezi depicted in 1948 a baba performing miracles within her village - said to know the spells of love that unite or separate lovers, as well as the remedies for various aches (from tooth-aches to heart-aches). But the portrait he makes of her is a caricature of a witch: she is a hunchback, who heals everybody with "two coal pellets and three lies", and refuses her services to the poor (due to being a greedy woman). This is no mistake that the poet makes "miracle" (minuni) rhyme with "minciuni", "lie". This baba is a scam. If we move to Gelu Vlaşin, we see baba Cloantza as an hallucination, or a psychological projection. The poet is half-drunk half-delirious, he wants to pay prostitutes but is too poor, so he goes looking for the "baba cloantza" so she can cast a "spell of wealth" onto him. And she appears in a middle of a series of very revealing symbols (dwarfs, circuses, prostitutes, spiders), in what the poet ultimately describes as a "fairytale for morons".

Ferent notably studies here a "variation" of the baba Cloantza, called the Baba Hârca. The Baba Hârca is a folktale character, an old witch who lives alone in a cavern within the depths of the woods, because she is afraid of humans, and who typically uses skulls (human or animal) for her magic rituals. "hârca" is a depreciative term for an old woman, an ugly woman or a wicked woman (or all three at once) - but it also means "skull", hence why the witch uses them to perform her spell. In the fairytales collected by Romanian folklorists we see that Baba Cloantza and Baba Hârca often appear as synonymous, in fact the two names can be used alternatively within a same fairytale. And in a Romanian "small-opera" of Romania created in 1848, by Matei Millo and Alexandru Flechtenmacher, it is under this name that the witch appears. "Baba Hârca, a small opera of witchcraft in two acts and three tableaux". Here the Hârca is actually a comical character appearing as a caricature of a gypsy woman, as well as a transvestite role (since the witch is played by Matei Millo himself).

Fourth, the Cloantza as a "ritualistic sorceress". Ferent reminds her reader that most of what we know of the Baba Cloantza has been "degraded" because it went through the literary imagination of a pastoral world disappeared (by authors who sang in a Romantic way the countryside of old), and through the prism of fairytales simplified for children - but she also reminds the reader of how the Romanian folklorists (such as Alecsdandri in his collect of "Cucul si Turturica") tried to identified the older roots of the folk-beliefs and superstitions. For example, in "Cucul si Turturica", the dialogue between the "cucul", the "cuckoo", a mysterious-dangerous bird son of a wicked witch, and the "turturica", the turtledove, the symbol of angelical love, we see a transcription of rural witchcraft. The "baba" preserved throughout the many proverbs of Romanian language is a supernatural entity within the village, a witch tied to the world of the demons. Baba Cloantza is recognized as different from regular human beings, but still accepted within the system of the community - because the witch is the intermediary between the living and the otherworld, and the catalyst of magical rituals. The baba, as the talented healer, "takes the ill upon her" - she is the mouth, as we saw, but the mouth that "sucks up" the evils to expel them in a symbolical way. The ritual is a manifestation of this "devouring" of the bad things, with an insistance on the power within the baba's words. The Cloantza, the "toothless", performs her magical as a ritualistic digestion (at least according to Ferent): she literaly feeds of the fears of the peasants, and uses as a magical "substance" her very words. This is why, while reflecting a distant, archaic form of hedonism and animism, the character of the baba always causes fear and fatalism... Let's return to the dialogue. The cuckoo is a playful, mischievious, jovial spirit who sings his desire and his determination, and will use the not-so-moral means his witch-mother taught him to seduce and have sex with the one he wants. Here, the malevolent influence of the Cloanta in romance becomes the game ; but a game of seduction filled with dangers, as symbolized by the objects the babas use. When a baba must bewitch a young man, she uses the bones of a bat trapped on Christmas Eve and buried alive in an anthill. With these bones, the Cloantza makes a hook to "hook" the heart of the one we want, and a small shovel to keep away those that are unloved.

Most of the powers of the baba seem to be tied to the element of water. The witch uses the water of rivers ; she can control the rain ; she uses holy water to cast spells, or she uses a "virgin water", "untouched water" (a term for enchanted water). Other elements can be used in baba rituals (the hazel-tree wand, the corn grains, the traditional "batic", the scarf around a peasant woman's head), and all they all call forward the society of the countryside, the world of the peasants where any everyday item can be filled with magic. Ferent reminds here of the importance of the communion with nature in the Romanian countryside. The peasant can sing a "doïna", a melancholic song, to his "spirit-brother", which can be a tree, a flower, a bird, an animal or the entire forest. All sorts of magical beings fill the countryside, such as the ielele (the "sirens of the woods") that inhabit hills and mountains. And if a young man is not careful when walking among the plains or choosing his travel-staff... he might get bewitched by the voice of a Cloantza, wandering forever, or snatched away in the sky "like an arrow flying". Only a knife stuck into the ground can break the spell of wandering.... Ferent also heavily insists upon the importance of recitation in spells: the baba always uses the "descântec", a form of invocation whose name means "a word, sung or recited, which can bewitch or break a spell". We have preserved a lot of these incantations, which were created for many various situations - there was a spell to heal snake-bites, there was another for people who feared to be alone... Or rather the fear of the "urât", a term quite difficult to translate, which literaly means "ugly", but explains a form of anguish towards the idea of being abandoned, mixed to a fear of the "other". Ferent proposes the idea of being "alone in a haunted house": that's the urât. To return to Baba Cloantza: she embodies all of the traits that were given to the village witch. Like them, she was here to offer magical solutions and answers to the very real needs and fears of the peasants.

Fifth, the Cloantza as the "shapeshifting female". The baba is also a manifestation of the archetype of the "Dreaded Mother" and the "Witch-Goddess" (or "Dreaded Goddess/Witch Mother ; or Mother Goddess and Dreaded Witch, however you like to arrange things). [Ferent highlights how there's always a multi-faced archetype of the "female", such as how the witch at the same time recalls ancient figures of priestesses or women initiated to the secrets of nature, and mythological characters such as Gaia, Maia, Circe, Demeter, Isis or Lilith]. The baba Cloantza is what happens when the "supreme female principle" becomes uncanny. For example, a recurring element in folk-mythology is that the baba can give birth to extraordinary physical beings. George Cosbuc, in "Atque nos!", reminds how the baba is the mother of a young man who was said to grow "in one year as much as others did in ten". George Cosbuc notably wrote texts celebrating the "magico-religious alchemy" that give birth in Romania to a rich gallery of female mythical beings: the baba Dochia (with probably Dacian origins), the Mama-Noptii (Mother of Night) surrounded by vampire-being, as well as the female Saints Tuesday, Friday, Wednesday and Thursday (described as pagan phantasm born of a Christianization of the deities of the Greco-Roman pantheon that were Mars, Zeus, Venus and Mercury). In fairytales, the baba usually appears as the embodiment of a wild elemental power.

The writer Ion Creangă, in the famous fairytale "Povestea porcului" (The tale of the pig), fragments the "baba" in three steps. First, she is the elderly peasant-woman who, despaired by her own sterility, adopts a pig she raises as a son (and will turn out to be a Prince Charming under a curse). Second, she is the Three Saints (Saint Wednesday, Saint Friday and Saint Sunday), three witches that will guide the heroine in her initiation-journey to find back her husband (the pig/prince she lost by throwing his pig-skin/pig-disguise into the fire). In a third time, the baba is "baba Cloantza the Toothless", the hag that keeps the prince her prisoner with malevolent powers. The pig-prince-hero not only will manage to outwit the Cloantza and find back his beloved, he will also free her from the spell that prevented her from givng birth (a four-year spell!). This story is haunted by the idea of the "cursed procreation", declined in three aspects. 1) the sterility of the old woman 2) the spell that prevents the heroine from giving birth to the child she is pregnant with 3) the idea of giving birth to a demon. When the pregnant heroine travels to the baba Cloantza's domain, she goes through a hellish-landscape filled with dragons and 24-headed otters, but especially in a world ruled by greed, cunning and wickedness. Here the wicked witch is formed as the antithesis of the naive young princess. The fairytale calls baba Cloantza "Hârca" (the name is invoked when the narration insists upon her old age, her crooked mind, and ugliness), but it also gives her the name Talpa Iadului (The Mole of the Devil). And the Mole of the Devil is actually one of the most evil beings of Romanian mythology, because it was believed to be the mother of all the demons, and renowned for its intelligence and treacherous nature. In the end of the fairytale, the Toothless baba/Skull/Mole of the Devil ends up punished by being tied to the tail of a horse - bringing back the comical and extravagant tone that opened the fairytale, and prevents it from falling into too much darkness.

But this structure of the youngest daughter of a king undergoing an initiation journey can be found in many fairytales. Petre Ispirescu, a great fan of Romanian folklore, published in 1676 "Porcul cel Fermecat" (The bewitched pig), a story that his own mother had told him, and that reuses the antithesis of the Baba Cloantza (here, a mother of dragons) with a young women (who discovers against her will the magical powers and the devious tricks of the witch). In this fairytale, the baba embodies a trial of Fate that the heroine must overcome to reach happiness (symbolized by a wedding out of love). The story tells the story of the youngest daughter of a king who, following her two older sisters, enters a room of the castle his father had forbidden her to go into. The princesses discover there an oracle-book which predicts royal weddings for the older sisters, a wedding with a pig for the third. The prophecy will come true and the princess is forced to leave her house to follow a pig, with a human voice so beautiful everybody suspects a spell is at work. The princess comes to love her strange husband, who removes his pig skin every night to become a man, but right as she was getting used to her new life she meets baba Cloantza who tells her she can break the spell by tying up her husband to the bed with a magical rope. Trusting the hag, the young bride uses the rope, but it breaks and her husband disappears - but not without telling her that, had she not obeyed the witch, he would have been set free from his curse in three days. The young wife, her newborn child in her arms, undergoes a quest to find her husband. Throughout hostile lands she obtains the advice and gifts of 1) the Moon and her sisters 2) the mother of the Sun and 3) the mother of the Wind. Arriving at the house of the cursed prince, the girl proves her intelligence and determination by making a ladder out of the magical chicken bones the three supernatural women gave her, and even cuts her own little finger to complete it. When she finds back her husband, he reveals her the full truth, and how his curse was caused by the Cloantza, because he had killed a dragon that was the baba's son. As we can see with all those stories, the idea is the same: to obtain her happy end and eternal bliss, the young woman must journey through a desert that symbolizes a journey outside of the real world ; the strange journey always begins with the girl breaking the law imposed by the father, and each time the baba Cloantza appears as the embodiment of the crime the girl must expiate/the evil she must vanquish.

Petre Ispirescu also depicted the baba Cloantza as the mother of a dragon in another fairytale, where the prince must kill it to free an enslaved princess. In this fairytale called "Poveste Taraneasca", "Peasant tale", the character of the Cloantza lives within a hellish world, with her courtyard surrounded by impaled human heads. In this tale, the Cloantza shows a trait that makes her close to the vodou sorcerers: she gains her strength and her immortality by swallowing, or rather "drinking", spirits that she keeps locked up in a barrel. By extension, we see that in this tale, the main threat of the story are the various vampires that live within her domain, and who try to steal away the soul of the old king.

Sixth, the Cloantza as the "devilish witch". An old proverb of Romania recalled by Alecsandri says "Baba-i calul dracului". Literaly "the Baba is the horse of the devil". Literary: "Old witch, bearer of Satan!". This proverb notably opens a poem of Alescandri called "Baba Cloantza" and written in 1842 - a folklore-inspired work that Alecsandri considered one of his best improvisations. In this text, the baba is reconstructed in the style of a Shakespearian witch. The Cloantza appears mad with lust for a beautiful young boy. The poem drifts into an infernal rural night, where malevolent ghosts fill the night-clouds, and snakes slither among the flowers of bewitched ponds. In this perverse Eden, under a "pale and blond moon", the Cloantza invokes several demons while threatening the young man with the worst torments if he ever resists to her charms. However, when the demons fail to perform their deed, the old Cloantza uses Satan himself, and offers him her soul without thinking about the consequences. The deal with the devil makes her act in a way that recalls a possession or insanity (running around, jumping, flying in the sky, screaming exorcism rituals). The "mad Kloantza", surrounded by the "thousand infernal spirits", fails to notice the laugh in the woods that announces her doom. Right as she arrives "two steps" away from her beloved, the Cloantaza's dream becomes a nightmare: the rooster's chant wakes up the village-folks, the ghosts of the night fade away, and we conclude on an aquatic final scene: Satan snatches his prey, the baba, and the two jump away into the depths of the pond... Nature returns to a seren and calm state, but the danger is not gone, because the poem adds that a "melancholic voice" can still be heard by the pond, calling and seducing the men that walk near it late in the evening, promising them to protect them "by my exorcisms of the evil eye, of cruel fate and snake bites." Critics have pointed out a dual reading of the poem. On one side, it is the epic depictions of an unhealthy love, the inappropriate passion of an elderly woman for a woman, doubled by the fairytale figures of the wicked witch in love with the Prince Charming ; on the other side, there is an humoristic reading of the poem as a display of petty feuds, vain quarrels annoying demands and bothersome requests. As such, the baba's original duality returns: a devilish character, and a spirit of mischief.

Seventh, the Cloantza as "the avatar of Death". In a very old folk-song of Romania, "Holera" (Cholera, collected by Alecsandri in 1853), the Cloantza appears with the imagery of the Roman Furies, with snakes in her hair. We find back around the witch another syncretism of Christianity and paganism, mixing the Furies of Ancient Rome with the vengeful angels of the Bible: wild hair, a dry skin, a "venomous" body, a sword of fire in one hand... Here, the Cloantza is the embodiment of death. More precisely, she represents the deadly disease of the cholera that appears on the path of the carefree and joyful young man Vâlcu. No negociation is possible: the Cloantza is a Grim Reaper. In fact, in the song she is exclusively referred to as "cloantza", the term "baba" disappears, removing any form of humanity.

In conclusion, Baba Cloantza throughout the Romanian folktales is a multi-faced, multi-voiced entity. She is the baba that heals or mutilates, she is the old woman that makes people cry or laugh. She is an oracle who sometimes has to work to make sure her prophecies come true. And Ferent concludes that somehow, the baba Cloantza acts as a double of the storyteller itself, as an entity that represents the "power of fiction". Because one of the main powers of the Cloantza is to turn the fears and anxieties of those that seek her into prophecies - aka into tales that will orientate the person's mind towards the future and force them to think about their own role in the world. The storyteller lacks a "real" power, and as such is as "toothless" as the Cloantza, but they still are the owner of a form of magic - a magic of illusions that can nourish or poison. As such, when the storyteller describes the baba, somehow they are describing themselves, presenting their own self within their fictional world. And as such, the baba kept evolving and changing throughout the centuries, going from a mystical therapeutic character in ancient days to a subversive but harmless entity in contemporary fiction.

#self reblog#romanian folklore#baba cloantza#baba cloanta#romanian witches#romanian mythology#romanian folktales#romanian literature

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isekai with male protags: "I was a loser on earth but now I'm super fucking strong and gettin mad bitches"

Isekai with female protags:

Reincarnated princess uses earth knowledge to make magitech a thing and romances sad girl

Girl romantically pursues her video game waifu

Girl is tasked to teach actual fucking gods to be more empathetic to humans

Woman reincarnated as the daughter of a magic item crafter uses earth knowledge to advance her trade

"Straight" girl is sucked into a world with zero men and lesbians everywhere and finds out she's sapphic (there's like actual plot but the gay is what matters.... to me)

A ghibli film. Need I say more

Woman reincarnated in video game as doomed villainess desperately tries to change her story

Girl reincarnated as a tiny baby spider kills monsters to level up

Like the male protag one but the lame guy's mom got isekaid with him and she's the op one.

Two normal girls fight urban legends in terrifying danger dimension

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

It is so infuriating when people keep depicting Zeus or Poseidon as old men because... that's the very opposite of what the gods are supposed to look like in the Greek myths.

One of the very basis of Greek mythology is that the gods are ever-young. They never age. They can put on the illusion of being an old person, but in their true form they cannot be old.

The whole "old white-bearded Zeus and Poseidon" is a mix of visual misinformation (due to the "white statue" phenomenon), projection of other figures onto the ancient gods (like the "Old Father Sea" projected onto Poseidon) and Christanization of Greek mythology (because it is easier to accept a vision of the "pagan" gods that fits the idea of the "Father-God" as the "old bearded white guy in the sky").

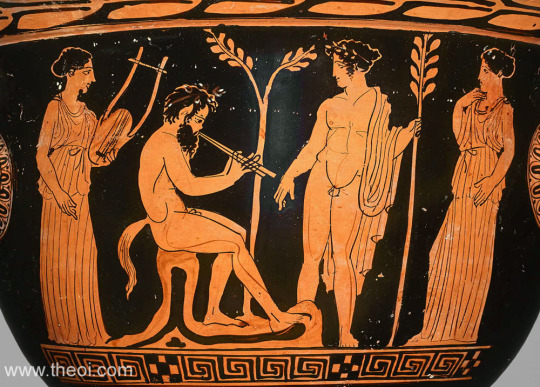

If you want to know what Zeus could have looked like, just check this famous painting:

No grey hair, no white beard. That's how the Ancient Greeks depicted Zeus, with colored hair and beard. Yes that's ageism, but heck the entirety of Ancient Greece was ageist as f*ck, so either you stick with the source material or you just move on to a different religion/mythology.

What is even more infuriating is that media that tend to do the whole "Let's age Zeus and Poseidon into grandpas" can't even keep consistent with the age of the gods because they always make Hades have a fully-colored hair and/or beard, making him look younger than Zeus... DESPITE ZEUS BEING THE YOUNGEST BROTHER COME ON PEOPLE READ THE FRIGGIN' BOOKS!

And here's a black-bearded Poseidon for the road:

(Mind you, of course, making the gods look elderly by default can make sense if you MAKE IT make sense. Like... how in American Gods we see weakened versions of the old gods starving for faith and offerings and worn-out by modern days and the forgetfulness of humans. There's a whole trope about old worn-out gods reduced to crumbling little old grandpas and grandmas that dates back to at least the mid-19th century literature.

But if you want to illustrate or put into visuals an actual Greek legend, within Ancient Greece, in a faithful way... Making Zeus white-bearded or Poseidon white-haired makes no sense. Except if Zeus' beard is made of clouds, and Poseidon's hair made of foam.)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Apollo (3)

A continuation of these posts.

III/ Towards the perfection of the divine

With Plato, the perception of the god changes completely. The philosopher doesn’t see in Apollo just one Olympian among others: he makes him THE god by excellence. The evolution that Pindar started now reaches its peak. Closely associated with Helios (so closely in fact that we can almost talk of an assimilation), Plato’s Apollo becomes the supreme god, the unique god, the “divine essence” of which the other deities are mere aspects of. Through the character of Apollo it is the Platonic doctrine that is expressed, in a symbolical ay. It is why, despite their ludic function, the various etymologies of the “Cratylus” must be considered very carefully (see the article “Apollo, the mythical sun”). As Apolouon, the god who washes, he represents purification of both the body and the mind, and reminds us of “Phaedo”. As Aploun, he highlights the link between unity and truth, and reminds us of “Parmenides” and “Philebus”. As Aei ballôn, he who always hits/reaches, he is infallibility and perfection. As Homopolôn, the simultaneous movement, he is harmony – as musical as celestial, the harmony of the spheres and the celestial bodies ; and we think of the “Timaeus”, or of the myth of Er at the end of the “Republic”. The respect carried here for the religion of Delphi is not a passive submission to the tradition: piety becomes the foundation of metaphysics. In this context, we can understand why Plato violently rejects the image of a lying, grudge-bearing, bloodthirsty Apollo as he appears within Thetis’ speech in the fragment of Aeschylus’ “Judgement of the Weapons” (quoted before) – a fragment which was preserved only because Plato denounced it within his “Republic”.

Prepared by Pindar, ensured by Plato, the greatness of the god, now the incarnation of the divine unity, will now definitively impose itself. The killer of Achilles, Koronis or Cassandra is now far away: with might now comes moral perfection, and unity replaced multiplicity. It is what Plutarch means when, during his list and comment about the various explanation of the mysterious “E” inscribed in the temple of Delphi, he finally concludes that it means: “You are”.

IV/ The Roman Apollo: politics and religion

We know the famous sentence of Horace: “The conquered Greece conquered its fierce vanquisher” (Epistles). The history of the Greek Apollo within Rome illustrates this line. It is true that we have to account for other influences that nuanced and “filtered” the Delphic presence and adapted it to the mentality of the Roman people: the Falisci beliefs and rites, the Etruscan legends and cults, the fact that the Cumae Sibyl originally belonged to an ancient chthonian goddess… But we can still easily follow a clear progression of the god. Beginning of the 5th century BCE: Tarquin the Superb (Tarquinius) sends two of his sons to the Pythian oracle. 433: a temple is dedicated to Apollo on the Field of Mars. 212: The first “ludi Apollinares” are celebrated. The 2nd of September of 31 BCE: Octave crushes in the waters of Actium the ships of Antony and Cleopatra under the sight of Apollo, who is honored on the promontory that dominates the entrance of the Ambracian gulf.

From this moment on truly begins the entrance of Apollo within Latin literature. (Ennius, Naevius and Lucilius all evoked him, but in a shy and discreet way). Octavius, who will soon be called Augst, cleverly organizes the propaganda. He has a rumor spread according to which Atia, the mother of the new sovereign, conceived him with Apollo. The victory of Actium becomes the “miracle of Actium”. In the year 28, a temple is dedicated to Actian Apollo on the Palatine Hill, right next to the palace the prince had built for himself. On the cuirass of August’s statue (the one found at Prima Porta), Apollo is depicted riding a griffin with a lyre in his hand, while facing his sister Diana, riding a stag and holding a quiver. Apollo, after being the one who caused the victory, becomes associated with the work of peace, the “Pax Augusta” – for he is the god of harmony.

The authors participate to the Augustinian work. Already, well before Actium, in the year 40, in his fourth “Bucolic”, Virgil was announcing the rule of Apollo. Within the “Aeneid”, Apollo plays a major role: it is him that gives to Aeneas and his companions the order to regain the land of their ancestors. He is also Aeneas’ protector, and just as beautiful as the Greek poets painted him: “ the god walks on the yokes of Cynthia, his flowing hair softly pressed with foliage and crowned with a gold diadem ; ad his arrows rustle on his shoulder”. He finds back all of his old functions: he is a prophet, a musician, an archer and a healer. He is “the greatest among the gods”. As for Horace, he opens his “Carmen Saeculare” by an invocation to the two children of Leto – the “Carmen Saeculare” being sung on the 3rd of July of the year 17 BCE for the celebration of the secular games organized by Augustus: “Phebus, and you, Diana, queen of the forests, luminous jewel of the sun, you, always adorable and always adored”.

During the episode of Daphne, in the first book of his “Metamorphoses”, Ovid does treat the god with some disrespect. Apollo is vanquished by the child-Cupid that he disdained. Overtaken with desire for Daphne, he hopes to be able to unite himself with her, “fooled by his own oracles”. He gives her a very eloquent speech, that the nymph refuses to listen to as she flees away from him. And right as Apollo is about to reach for her, Daphne, turned into a laurel tree, escapes him forever. However, if we look at the way Ovid treats the gods in the entirety of his “Metamorphoses”, we do note that Phoibos-Apollo has a more important role than the others. The others gods are not presented with any kind of dignity and do not seem to fit their ranks: they are only seen embroiled in romances or taking part in petty quarrels. On the contrary, Ovid’s Apollo, just like the one of Virgil, has all of his Antique functions – he is an oracle, he is a medicine spirit, he is a musician, and to all of this is added the art of the metamorphoses, an art pushed to a level of science. He is the god of harmony and of light. His identification with the sun which, throughout the previous century was sometimes clear sometimes underlying, is here expressed with no hesitation in the speech Ovid gives to Pythagoras. With the Augustan Apollinism, the depiction of the god shifts to a solar theology, that the successors of Augustus will all make use of. The god of Lycia, the god of the wolves, is forgotten. Apollo is now the figure of light, the harmonious and perfect spirit, and it is as such that he is now forever imprinted in our cultural subconscious.

#greek mythology#roman gods#apollo#roman mythology#apollon#greek gods#plato#ovid#virgil#helios#the myth of apollo

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare's Cymbeline obviously has some story elements in common with Snow White. A princess heroine, a wicked queen stepmother, a servant is ordered to kill the princess but instead lets her go, she finds the home of some men in the wilderness and lives with them, but then she succumbs to "poison" from her stepmother and is mourned as dead, yet she isn't really dead, and eventually there's a happy ending.

In the play, the character of Belarius, the foster father who takes Imogen in (and whose foster sons turn out to be her long-lost brothers), goes by the pseudonym Morgan.

In the Let's Pretend radio adaptation of Snow White (or rather Snowdrop, as it's called), the leader of the seven dwarfs, basically a more dignified version of Disney's Doc, is named Morgan.

I see what you did there, Nila Mack. I see what you did there.

#shakespeare#reblog#snow-white#cymbeline#snow white#the amount of fairytale material within shakespeare is crazy

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hesitated posting this on my main blog - but instead I will reblog this here for all to see

Romanian witches: Muma Padurii

(Note: I unfortunately cannot add the accents needed for the writing of those names since my keyboard is not equiped. So know that there are accents missing)

I originally made a post about one Romanian fairytale figure... which turned into a post about two fairytale figures... which became a post about three fairytale figures... So ultimately I decided to split this post into a whole series because it was getting too big. I want to explore with you three characters tied together in Romanian folklore and all present within Romanian fairytales, but each fascinating in their own right. And I want to begin with the first of these ladies... Muma Padurii.

Muma Padurii means "The Forest Mom", or "The Mother of the Forest" (Muma is an archaic form of "mom").

In fairytales, Muma Padurii is an antagonist. She is an embodiment of the wicked witch, or rather of the hag. She is a very old and very ugly woman (so ugly the expression "You look like Muma padurii" is an insult) who lives all alone in a little, dark and scary house in the depths of the woods. She is not a normal woman: she is a witch gifted with various supernatural powers (including shapeshifting), and she is also an ogress who loves to eat children. It is as a children-predator that she usually appears within Romanian fairytales, luring kids to her house to kill and cook them. One of the most famous Muma Padurii fairytales is the Romanian version of "Hansel and Gretel", which mostly differs by A) having the witch named B) the house not being made of candy and C) the genders are reversed (here it is the girl that is to be boiled alive into a soup, while it is the boy that pushes the hag into the oven).

But the thing with Muma Padurii is that, in a similar way to Frau Holle, she is an entity that was "split" between fairytales and legends. There is a Muma Padurii of folktales which is the evil hag I presented above, but there is also a Muma Padurii of beliefs and legends which is quite different and much more neutral.

This Muma Padurii is still an old, ugly, shapeshifting witch - but she is presented as amoral rather than wicked, with a personality mixing a fairy-like mischieviousness and just pure insanity. The name "Muma Padurii" is also very revealing... In the fairytales this name is used in the typical motif of the witch/hag as the "false mother" or "anti-mother", but in the Romanian mythology, this name indicates what Muma Padurii is. She is the Mother of the Forest, as in the spirit of the forest. Her main role, and the reason for her hostility towards humankind, is her function as the guardian of the woods. She still lives in a remote and hidden location - but it is not always a little cabin, it can just be a tree, and it is usually within a virgin-woodland at the heart of the forest, untouched by human hands. She still brews potions - but they are good potions, that she uses to heal injured animals and sick trees. For Muma Padurii always keeps the forest alive. She does attack humans - but only those that destroy the fauna and flora, or that trespass within forbidden areas where only wild things are supposed to be. This was why those that entered the woods were warned to not go too far and to respect what surrounded them: else Muma Padurii would at best scare them away, at worst drive them to insanity with her magic. As such, it was forbidden to pick up certain wild fruits and berries in the forest during certain times of the year - they were for the animals to replenish their strength, and Mama Padurii made sure this rule was followed. In the most extreme cases she would kill the trespassers and devour their corpses like a wild animal - a bogey-version of Muma Padurii that explains her role as a child-eating crone in fairytales...

Muma Padurii is present all across Romania, sometimes in local variations (Padureanca, Muma Huciului), and this explains why there are so many different incarnations of her. Sometimes she is an angry ghost of the woods, a vengeful spirit which can be heard crying among the trees for all the plants that mankind destroyed, and if a house built near the forest isn't carefully locked up at night, she will enter in them at midnight and kill all those inside... Other times she is depicted as a young and beautiful fairy of light, who will be kind and helpful to children but will trick adults into being lost, having their body paralyzed or dying in various ways. This specific idea of the "young faced Muma Padurii" is notably present in another folktale/fairytale, where it is said that the Muma Padurii is a witch that needs to eat human hearts to keep herself young and alive - as such she takes on the appearance of a beautiful woman to lure young men into the woods, but once they are isolated enough she turns into a giant monster and rips their hearts away.

Her link to the forest is highlighted by how she is often said to disguise herself as a tree, to be a part-tree woman, or a hag clothed in moss (she also can appear as a cow, a horse or an ox) ; her function as a "Romanian fairy" is also highlighted by how in various legends she either makes babies sick, or replaces them by changelings (and as such they were several folk-spells and rituals Romanian country-folks used to protect their babies from the Forest-Mom). But mostly Muma Padurii stays an embodiment of the woods in what they have of dangerous and scary. She can be kind and helpful - but only towards the "innocent", animals, plants and (sometimes) children. However she stays an ancient woman of the woods, the mistress of the wild animals, the embodiment of a state of non-civilizations, and as such she is the fright that drives one mad and the savage force that will kill and eat men. And even then, the fauna and flora itself is not always escaping her wrath - some records say that Mama Padurii knows the name of every tree of the forest, but that she can get angry at some and curse them to fall either by the woodsman's axe or by lightning.

The last interesting difference between the fairytale Muma and the legendary Muma is that, while the fairytale Muma is usually a lonely entity, in beliefs Muma Padurii was part of a large family. Sometimes Muma Padurii herself was multiplied into several "Muma" - there was notably a belief about many of them sometimes visiting the cabins of those that lived near the woods, asking to have their hair brushed and cleaned, with a comb and butter (which isn't an easy feat since she had her hair dirty, tangled in snake-like braids and so long it touches the floor). Anyone who agreed to the task and performed it well could receive a wish from the Mother of the Woods - but the rule was that they could only pronounce three words in total as long as she was here, if a fourth was pronounced, she would take your voice and leave you mute. Sometimes Muma Padurii was given a male counterpart of companion called "The Father of the Forests", or the "Woods Papa".

Muma Padurii was also said to have several sons, which were the spirits of the woods and/or of the night (going by names such as Decuseara, Zorila, Murgila, Mamornito or "Midnight"). She is also linked to a set of female forest spirits known as the Fata Padurii (Fata being of course linked to the "fairies", "fées", "fatum" - but here it is to be understood as "The Daughters of the Forest", "The Girls of the Woods, and fittingly they are said to be the daughters of Muma Padurii) ; and to an entity I personaly do not know much about, "Mosul Codruilui" (she is said to be her mother, and "Mosul" means "old woman")

Finally, there was a certain Christianization of the Muma (as some tales started saying her task as a guardian of the forest was given to her by God), and a modern attempt at explaining how she could be such an ambiguous entity, benevolent and malevolent at the same time: most modern storytellers highlight how protective she is of the fauna and flora, and how she was said to wail and cry for the destroyed wood, to explain her "transformation" as her becoming more and more bitter, and angrier and fuller of hate the more humans destroyed her domain, harmed her trees and wounded her "children". A true ecological fable.

Some people point out that Muma Padurii could be a "Romanian equivalent" of the Russian Baba-Yaga which is... not quite exact and not quite true. The two characters seem to derive from a same old "forest mother-goddess" but there are too many differences between Muma Padurii and Baba-Yaga for them to be consideed one and the same. There is however a interesting link between the two, which will be the subject of my next post... about Baba Cloantza.

#self reblog#romanian folklore#romanian mythology#romanian witches#witches#folkloric figures#hag#mythical witches#romanian legends#muma padurii

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know... It is REALLY easy to do the whole "voodoo doll" trope or practice while avoiding any cultural appropriation, religious misrepresentation or racist cliche. Just... don't call it "voodoo".

Because if you are not aware, this practice of using a doll or figurine to bewitch or curse or put a spell onto a person, is actually older than the creation of vodou and its various branches. It can be found in medieval Europe. Several European countries have their own specific words and terms for this magical practice - a pratice attested since very early days. Heck it was even present in Greco-Roman Antiquity!

So... there is nothing forcing you to constantly say "voodoo doll" when talking about a spell-through-puppet. Except a bad habit that the United-States media imposed onto the rest of the world, I guess...

And, as the bitter old cynical soul that I am, I will definitively grumble something about how it is very telling that Americans did not choose to pick one of the several European terms and words for this magical practice and rather latched desperately onto a term related to a discriminized, fantasized and misrepresented Black religion... grumble grumble grumble.

But I will be fair to Americans and leave the possibility of the doubt. Because we all know the common American is a bit too lazy to do thorough research or be interested in anything outside of its own country, and so it is possible that all those people did sincerely believe that the idea of "magical bewitching figurines" was created on American land - because as we ALL know, everything was invented in America and for or by Americans, right? So of course it is bound to be the "voodoo doll" because it can't possibly have existed before the United-States were founded right?

Grumble grumble grumble.

#yeah i'm bitter about it#voodoo doll#it is especially obvious for me because I'm French right#and there's a lot of books about the history of witches in Europe right#magic#and they all carefully avoid any anachronism by not using the term voodoo doll#cause its overuse is REALLY something very American#witchcraft#spell#bewitching#european magic#language#european witchcraft#magical practices#my rant of the day

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Poppins is probably the first progressive Disney movie. It marks an interesting start of a long process that would lead from the cultural conservatism of Walt Disney himself to the more progressive liberal values from today's age.

Yeah, the film still ends with the nuclear family established almost like the perfect family structure. But noticed how the family isn't fixed by the father gaining even more control over the them, what would be expected from the time period, but by the father letting go of the strict hierarchy that he himself put over them in the beginning.

The film puts a lot of the blame for the family's situation on Mr. Banks himself. Mrs. Banks first wave feminism is played for laughs, but the film is more sympathetic and supportive of her than of Mr. Banks.

Mr. Banks believes in order and discipline, and strict gender and class roles, and that is what leads his family to intense suffering. Even his wife, Winifred, a suffragette mind you, is still highly submissive to him in the beginning.

Mary Poppins represents an element of unabashed fun, optimism, and chaos, clashing with Mr. Banks' strict order several times, breaking apart with the strict gender and class roles, at least for a little while.

Mary Poppins manipulates, subverts, and slightly mock Mr. Bank's sense of order and discipline several times over the film. Mr. Banks himself describe Mary Poppins' philosophy as "sugary female nonsense".

Mary Poppins is strict and disciplined herself, but around her all rules bend, and even the upper classes can dance happily with the working classes as if they are all equal.

Heck, the final scene, Let's Fly a Kite, it's literally all class rules being broken for the final time. Even the greedy bank executives are flying a kite, as happy as children, not exclusively thinking of money for the very first time.

Mary Poppins, intentionally or accidentally, is a very progressive family film for its time.

@ariel-seagull-wings @thealmightyemprex @princesssarisa @the-blue-fairie @tamisdava2 @theancientvaleofsoulmaking @mask131

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily reminder that the legend of Sweeney Todd (I am talking about the 19th century fiction, long before any movie or Broadway musical) is actually a British modern reinvention of an older "urban legend" - a 17th century French legend about the murderous barber and cannibalistic baker (male this time) of the rue des Marmousets, a legend that stood strong and famous until the 19th century.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trivia of the day: Unlike the traditional image of the dragon as a fire-spitting entity associated with burning, lava, and whatnot, the French dragons are all mostly aquatic entities or monsters associated with waters.

From the Vouivre to the Drac, passing by the dragon of the Bièvre and the gargoyle of the Seine, without forgetting the Tarasque and many others... The French dragons are not renowned for spitting fire, and usually dwell by rivers, lakes and swamps in underwater lairs, embodying or manifesting the dangers of floods, watery storms and drowning.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

119 notes

·

View notes