#julia mother of mark antony

Text

Some people idolize generals. I idolize Mark Antony's mom.

I'm picturing this petite 60-year-old woman storming up to a big burly triumvir and his 500 armed guards, shouting, "Marcus Antonius, WHAT do you think you are doing?" and the most dangerous man in Rome just winces.

(Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra, chapter 17)

#i love her so much#julia mother of mark antony#mark antony#adrian goldsworthy#antony and cleopatra#ancient rome

244 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any favourite historical couples?

The way my head went spinning when I read this ask anon haha, I have manyy, but I’ll focus here and say the main ones I read/know more about:

- Augustus + Livia Drusilla

- Cesare Borgia + Charlotte d'Albret

- Rodrigo Borgia (pope Alexander VI) + Vannozza dei Cattanei**

- Elizabeth Woodville + Edward IV

- Cleopatra VII + Mark Antony

- Julia Caesaris + Pompey

- Queen Victoria + Prince Albert

- Nicholas II + Alexandra Feodorovna

**There are some questionings and speculations about this relationship and if it was indeed a romantic one, but personally I tend to follow the general/traditional historical line here that posits Rodrigo and Vannozza as a couple (Rodrigo's longest relationship) and the father and mother of the most known Borgia children: Juan, Cesare, Lucrezia and Gioffre Borgia.

#anon ask#ask answered#honestly if i'm reading history i'm finding fav. historical couples lmaoo#i can't help it#:(((((#thank you for asking!#<3

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Julia the Elder was the only child of the first Roman emperor Augustus, who divorced her mother Scribonia the day of Julia’s birth. Julia was soon taken from her mother and raised in the household of her father and stepmother Livia. Augustus was strict and controlling of her education and social life, but he also held her in great affection and is said to have fondly remarked that he had two spoiled daughters to put up with, Rome and Julia.

Like many members of Augustus’s family, Julia was married off several times as part of his dynastic plans. Her first marriage at age fourteen to her cousin Marcellus didn’t last long, as he died two years later in 23 BCE. At eighteen, Julia married her father’s general and closest friend Agrippa, who was twenty-five years her senior. They had five children: Gaius Caesar, Julia the Younger, Lucius Caesar, Agrippina the Elder, and Agrippa Postumus. Augustus adopted Gaius and Lucius as his heirs and oversaw their educations. Shortly after Agrippa’s death in 12 BCE, Augustus arranged for Julia to marry her stepbrother Tiberius. The two reportedly held each other in contempt, and the marriage was unhappy. They only had one child, a son who died in infancy, and they separated in at least 6 BCE, when Tiberius retired to Rhodes without Julia, if not earlier.

Julia’s downfall came in 2 BCE when she was accused of violating Augustus’s anti-adultery laws. Some historians, both Roman and modern, also believe that there was an element of political conspiracy to the actions of Julia and her group. Augustus was furious with her behavior and showed no mercy even though she was his only child. Iullus Antonius, the most notable of Julia’s alleged lovers – and the most politically dangerous, as he was the son of Augustus’s enemy Mark Antony – was forced to commit suicide, and Julia and the rest of her alleged lovers were exiled. Julia was confined to the island of Pandateria with her mother, and five years later was moved to Rhegium on the mainland, but she was never permitted to return to Rome. Augustus also forbade her burial in the family mausoleum. She died in exile in 14 CE, not long after Augustus’s death; some Roman historians claim that Tiberius cut off her food supply after he succeeded Augustus as emperor, and others that she wasted away from grief after hearing of Tiberius’s murder of her youngest son.

While most Roman historians describe Julia as exaggeratedly promiscuous and hedonistic, Macrobius recalls her wit, charm, kindness, and love of literature and writes that she was beloved by the people of Rome. He attributes many witticisms to her, one of the most famous being a response to an observation that she didn’t share her father’s frugal lifestyle: “He forgets that he is Caesar, but I never forget that I am Caesar’s daughter.”

#historyedit#classicsedit#tagamemnon#ancient rome#julia the elder#julia major#julia#i can never remember which one is my tag for her lmao#anyway. LOVE HER!!!!#my favorite julio-claudian lady i'd say#the caption is way too long but i just love her so much i had to put in all this info#mine#i don't usually fancast historical figures but god as soon as i laid eyes on matilda de angelis in leonardo#i was like THAT IS JULIA

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...If any precedent might have preoccupied Livia, especially in her early career, when she was attempting to mould an image fitting for the times, it would have been a negative one, provided by the most notorious woman of the late republic and, most important, a woman who clashed headlong with Octavian in the sensitive early stages of his career. Fulvia was the wife of Mark Antony, and his devoted supporter, no less loyal than Livia in support of her husband, although their styles were dramatically different.

Fulvia’s struggle on behalf of Antony, Octavian’s archenemy, has secured her an unenviable place in history as a power-crazed termagant. While her husband was occupied in the East in 41, Fulvia made an appearance, along with Antony’s children, before his old soldiers in Italy, urging them to remain true to their commander. When Antony’s brother Lucius gathered his troops at Praeneste to launch an attack on Rome, Fulvia joined him there, and the legend became firmly established that she put on a sword, issued the watchword, gave a rousing speech to the soldiers, and held councils of war with senators and knights. This was the ultimate sin in a woman, interfering in the loyalty of the troops.

In the end Octavian prevailed and forced the surrender of Lucius and his armies at Perusia. The fall of the city led to a massive exodus of political refugees. Among them were two women, Livia and Fulvia. Livia joined her husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero, who escaped first to Praeneste and then to Naples. Fulvia fled with her children to join Antony and his mother in Athens. Like Octavia later, she found that her dedicated service was not enough to earn her husband’s gratitude. In fact, Antony blamed her for the setbacks in Italy.

A broken woman, she fell ill at Sicyon on the Gulf of Corinth, where she died in mid-40 bc. Antony in the meantime had left Italy without even troubling himself to visit her sickbed. Fulvia’s story contains many of the ingredients familiar in the profiles of ambitious women: avarice, cruelty, promiscuity, suborning of troops, and the ultimate ingratitude of the men for whom they made such sacrifices. She was at Perusia at the same time as Livia, and as wives of two of the triumvirs, they would almost certainly have met. In any case, Fulvia was at the height of her activities in the years immediately preceding Livia’s first meeting with Octavian, and at the very least would have been known to her by reputation. Livia would have seen in Fulvia an object lesson for what was to be avoided at all costs by any woman who hoped to survive and prosper amidst the complex machinations of Roman political life.

In one respect Livia’s career did resemble Fulvia’s, in that it was shaped essentially by the needs of her husband, to fill a role that in a sense he created for her. To understand that role in Livia’s case, we need to understand one very powerful principle that motivated Augustus throughout his career. The importance that he placed in the calling that he inherited in 44 bc cannot be overstressed. The notion that he and the house he created were destined by fate to carry out Rome’s foreordained mission lay at the heart of his principate. Strictly speaking, the expression domus Augusta (house of Augustus) cannot be attested before Augustus’ death and the accession of Tiberius, but there can be little doubt that the concept of his domus occupying a special and indeed unique place within the state evolves much earlier.

Suetonius speaks of Augustus’ consciousness of the domus suae maiestas (the dignity of his house) in a context that suggests a fairly early stage of his reign, and Macrobius relates the anecdote of his claiming to have had two troublesome daughters, Julia and Rome. When Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae in 2 bc, Valerius Messala spoke on behalf of the Senate, declaring the hope that the occasion would bring good fortune and favour on ‘‘you and your house, Augustus Caesar’’ (quod bonum, inquit, faustum sit tibi domuique tuae, Caesar Auguste).

The special place in the Augustan scheme enjoyed by the male members of this domus placed them in extremely sensitive positions. The position of the women in his house was even more challenging. In fashioning the image of the domus Augusta, the first princeps was anxious to project an image of modesty and simplicity, to stress that in spite of his extraordinary constitutional position, he and his family lived as ordinary Romans. Accordingly, his demeanour was deliberately self-effacing.

His dinner parties were hospitable but not lavish. The private quarters of his home, though not as modest as he liked to pretend, were provided with very simple furniture. His couches and tables were still on public display in the time of Suetonius, who commented that they were not fine enough even for an ordinary Roman, let alone an emperor. Augustus wore simple clothes in the home, which were supposedly made by Livia or other women of his household. He slept on a simply furnished bed. His own plain and unaffected lifestyle determined also how the imperial women should behave.

His views on this subject were deeply conservative. He felt that it was the duty of the husband to ensure that his wife always conducted herself appropriately. He ended the custom of men and women sitting together at the games, requiring females (with the exception of the Vestals) to view from the upper seats only. His legates were expected to visit their wives only during the winter season. In his own domestic circle he insisted that the women should exhibit a traditional domesticity.

He had been devoted to his mother and his sister, Octavia, and when they died he allowed them special honours. But at least in the case of Octavia, he kept the honours limited and even blocked some of the distinctions voted her by the Senate. Nor did he limit himself to matters of ‘‘lifestyle.’’ He forbade the women of his family from saying anything that could not be said openly and recorded in the daybook of the imperial household. In the eyes of the world, Livia succeeded in carrying out her role of model wife to perfection. To some degree she owed her success to circumstances. It is instructive to compare her situation with that of other women of the imperial house.

Julia (born 39 bc) summed up her own attitude perfectly when taken to task for her extravagant behaviour and told to conform more closely to Augustus’ simple tastes. She responded that he could forget that he was Augustus, but she could not forget that she was Augustus’ daughter. Julia’s daughter, the elder Agrippina (born 19 bc?), like her mother before her, saw for herself a key element in her grandfather’s dynastic scheme. She was married to the popular Germanicus and had no doubt that in the fullness of time she would provide a princeps of Augustan blood.

Not surprisingly, she became convinced that she had a fundamental role to play in Rome’s future, and she bitterly resented Tiberius’ elevation. Her daughter Agrippina the Younger (born ad 15?) was, as a child, indoctrinated by her mother to see herself as the destined transmitter of Augustus’ blood, and her whole adult life was devoted to fulfilling her mother’s frustrated mission. From birth these women would have known of no life other than one of dynastic entitlement. By contrast, Livia’s background, although far from humble, was not exceptional for a woman of her class, and she did not enter her novel situation with inherited baggage.

As a Claudian she may no doubt have been brought up to display a certain hauteur, but she would not have anticipated a special role in the state. As a member of a distinguished republican family, she would have hoped at most for a ‘‘good’’ marriage to a man who could aspire to property and prestige, perhaps at best able to exercise a marginal influence on events through a husband in a high but temporary magistracy. Powerful women who served their apprenticeships during the republic reached their eminence by their own inclinations, energies, and ambitions, not because they felt they had fallen heir to it.

However lofty Livia’s station after 27 bc, her earlier life would have enabled her to maintain a proper perspective. She did not find herself in the position of an imperial wife who through her marriage finds herself overnight catapulted into an ambience of power and privilege. Whatever ambitions she may have entertained in her first husband, she was sadly disappointed. When she married for the second time, Octavian, for all his prominence, did not then occupy the undisputed place at the centre of the Roman world that was to come to him later. Livia thus had a decade or so of married life before she found herself married to a princeps, in a process that offered time for her to become acclimatised and to establish a style and timing appropriate to her situation.

It must have helped that in their personal relations she and her husband seem to have been a devoted couple, whose marriage remained firm for more than half a century. For all his general cynicism, Suetonius concedes that after Augustus married Livia, he loved and esteemed her unice et perservanter (right to the end, with no rival). In his correspondence Augustus addressed his wife affectionately as mea Livia.

The one shadow on their happiness would have been that they had no children together. Livia did conceive, but the baby was stillborn. Augustus knew that he could produce children, as did she, and Pliny cites them as an example of a couple who are sterile together but had children from other unions. By the normal standards obtaining in Rome at the time they would have divorced—such a procedure would have involved no disgrace—and it is a testimony to the depth of their feelings that they stayed together. In a sense, then, Livia was lucky.

That said, she did suffer one disadvantage, in that when the principate was established, she found herself, as did all Romans, in an unparalleled situation, with no precedent to guide her. She was the first ‘‘first lady’’—she had to establish the model to emulate, and later imperial wives would to no small degree be judged implicitly by comparison to her. Her success in masking her keen political instincts and subordinating them to an image of self-restraint and discretion was to a considerable degree her own achievement.

In a famous passage of Suetonius, we are told that Caligula’s favourite expression for his great-grandmother was Ulixes stolatus (Ulysses in a stola). The allusion appears in a section that supposedly illustrates Caligula’s disdain for his relatives. But his allusion to Livia is surely a witty and ironical expression of admiration. Ulysses is a familiar Homeric hero, who in the Iliad and Odyssey displays the usual heroic qualities of nerve and courage, but is above all polymetis: clever, crafty, ingenious, a man who will often sort his way through a crisis not by the usual heroic bravado but by outsmarting his opponents, whether the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, or the enchantress Circe, or the suitors for Penelope.

Caligula implied that Livia had the clever, subtle kind of mind that one associates with Greeks rather than Romans, who were inclined to take a head-on approach to problems. But at the same time she manifested a particularly Roman quality. Rolfe, in the Loeb translation of Suetonius’ Life of Caligula, rendered the phrase as ‘‘Ulysses in petticoats’’ to suggest a female version of the Homeric character. But this is to rob Caligula’s sobriquet of much of its force.

The stola was essentially the female equivalent of the toga worn by Roman men. A long woollen sleeveless dress, of heavy fabric, it was normally worn over a tunic. In shape it could be likened to a modern slip, but of much heavier material, so that it could hang in deep folds. The mark of matronae married to Roman citizens, the stola is used by Cicero as a metaphor for a stable and respectable marriage. Along with the woollen bands that the matron wore in her hair to protect her from impurity, it was considered the insigne pudoris (the sign of purity) by Ovid, something, as he puts it, alien to the world of the philandering lover.

Another contemporary of Livia’s, Valerius Maximus, notes that if a matrona was called into court, her accuser could not physically touch her, in order that the stola might remain inviolata manus alienae tactu (unviolated by the touch of another’s hand). Bartman may be right in suggesting that the existence of statues of Livia in a stola would have given Caligula’s quip a special resonance, but that alone would not have inspired his bon mot. To Caligula’s eyes, Livia was possessed of a sharp and clever mind.

But she did not allow this quality to obtrude because she recognised that many Romans would not find it appealing; she cloaked it with all the sober dignity and propriety, the gravitas, that the Romans admired in themselves and saw represented in the stola. Livia’s greatest skill perhaps lay in the recognition that the women of the imperial household were called to walk a fine line. She and other imperial women found themselves in a paradoxical position in that they were required to set an example of the traditional domestic woman yet were obliged by circumstances to play a public role outside the home—a reflection of the process by which the domestic and public domains of the domus Augusta were blurred.

Thus she was expected to display the grand dignity expected of a person very much in the public eye, combined with the old-fashioned modesty of a woman whose interests were confined to the domus. Paradoxically, she had less freedom of action than other upper-class women who had involved themselves in public life in support of their family and protégés. As wife of the princeps, Livia recognised that to enlist the support of her husband was in a sense to enlist the support of the state.

That she managed to gain a reputation as a generous patron and protector and, at the same time, a woman who kept within her proper bounds, is testimony to her keen sensitivity. In many ways she succeeds in moving silently though Rome’s history, and this is what she intended. Her general conduct gave reassurance to those who were distressed by the changing relationships that women like Fulvia had symbolised in the late republic. It is striking that court poets, who reflected the broad wishes of their patron, avoid reference to her. She is mentioned by the poet Horace, but only once, and even there she is not named directly but referred to allusively as unico gaudens mulier marito (a wife finding joy in her preeminent husband).

The single exception is Ovid, but most of his allusions come from his period of exile, when desperation may have got the better of discretion. The dignified behaviour of Livia’s distinguished entourage was contrasted with the wild conduct of Julia’s friends at public shows, which drove Augustus to remonstrate with his daughter (her response: when she was old, she too would have old friends). In a telling passage Seneca compares the conduct of Livia favourably with even the universally admired Octavia. After losing Marcellus, Octavia abandoned herself to her grief and became obsessed with the memory of her dead son. She would not permit anyone to mention his name in her presence and remained inconsolable, allowing herself to become totally secluded and maintaining the garb of mourning until her death.

By contrast, Livia, similarly devastated by the death of Drusus, did not offend others by grieving excessively once the body had been committed to the tomb. When the grief was at its worst, she turned to the philosopher Areus for help. Seneca re-creates Areus’ advice. Much of it, of course, may well have sprung from Seneca’s imagination, but it is still valuable in showing how Livia was seen by Romans of Seneca’s time. Areus says that Livia had been at great pains to ensure that no one would find anything in her to criticise, in major matters but also in the most insignificant trifles. He admired the fact that someone of her high station was often willing to bestow pardon on others but sought pardon for nothing in herself.

…Perhaps most important, it was essential for Livia to present herself to the world as the model of chastity. Apart from the normal demands placed on the wife of a member of the Roman nobility, she faced a particular set of circumstances that were unique to her. One of the domestic priorities undertaken by Augustus was the enactment of a programme of social legislation. Parts of this may well have been begun before his eastern trip, perhaps as early as 28 bc, but the main body of the work was initiated in 18.

A proper understanding of the measures that he carried out under this general heading eludes us. The family name of Julius was attached to the laws, and thus they are difficult to distinguish from those enacted by Julius Caesar. But clearly in general terms the legislation was intended to restore traditional Roman gravitas, to stamp out corruption, to define the social orders, and to encourage the involvement of the upper classes in state affairs. The drop in the numbers of the upper classes was causing particular concern. The nobles were showing a general reluctance to marry and, when married, an unwillingness to have children. It was hoped that the new laws would to some degree counter this trend.

The Lex Iulia de adulteriis coercendis, passed probably in 18 bc, made adultery a public crime and established a new criminal court for sexual offences. The Lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus, passed about the same time, regulated the validity of marriages between social classes. The crucial factor here, of course, was not the regulation of morality but rather the legitimacy of children. Disabilities were imposed on the principle that it was the duty of men between twenty-five and sixty-five and women between twenty and fifty to marry. Those who refused to comply or who married and remained childless suffered penalties, the chief one being the right to inherit. The number of a man’s children gave him precedence when he stood for office.

Of particular relevance to Livia was the ius trium liberorum, under which a freeborn woman with three children was exempted from tutela (guardianship) and had a right of succession to the inheritance of her children. Livia was later granted this privilege despite having borne only two living children. This social legislation created considerable resentment—Suetonius says that the equestrians staged demonstrations at theatres and at the games. It was amended in ad 9 and supplemented by the Lex Papia Poppaea, which seems to have removed the unfair distinctions between the childless and the unmarried and allowed divorced or widowed women a longer period before they remarried.

Dio, apparently without a trace of irony, reports that this last piece of legislation was introduced by two consuls who were not only childless but unmarried, thus proving the need for the legislation. Livia’s moral conduct would thus be dictated not only by the already unreal standards that were expected of a Roman matrona but also by the political imperative of her husband’s social legislation. Because Augustus saw himself as a man on a crusade to restore what he considered to be old-fashioned morality, it was clearly essential that he have a wife whose reputation for virtue was unsullied and who could provide an exemplar in her own married life.

In this Livia would not fail him. The skilful creation of an image of purity and marital fidelity was more than a vindication of her personal standards. It was very much a public statement of support for what her husband was trying to achieve. Tacitus, in his obituary notice that begins Book V of the Annals, observes that in the matter of the sanctitas domus, Livia’s conduct was of the ‘‘old school’’ ( priscum ad morem). This is a profoundly interesting statement at more than one level. It tells us something about the way the Romans idealised their past. But it also says much about the clever way that Livia fashioned her own image.

Her inner private life is a secret that she has taken with her to the tomb. She may well have been as pure as people believed. But for a woman who occupied the centre of attention in imperial Rome for as long as she did, to keep her moral reputation intact required more than mere proper conduct. Rumours and innuendo attached themselves to the powerful and prominent almost of their own volition. An unsullied name required the positive creation of a public image. Livia was despised by Tacitus, who does not hesitate to insinuate the darkest interpretations that can be placed on her conduct.

Yet not even he hints at any kind of moral impropriety in the narrow sexual sense. Even though she abandoned her first husband, Tiberius Claudius, to begin an affair with her lover Octavian, she seems to have escaped any censure over her conduct. This is evidence not so much of moral probity as of political skill in managing an image skilfully and effectively. None of the ancient sources challenges the portrait of the moral paragon. Ovid extols her sexual purity in the most fulsome of terms. To him, Livia is the Vesta of chaste matrons, who has the morals of Juno and is an exemplar of pudicitia worthy of earlier and morally superior generations. Even after her husband is dead she keeps the marriage couch (pulvinar) pure. (She was, admittedly in her seventies.)

Valerius Maximus, writing in the Tiberian period, can state that Pudicitia attends the couch of Livia. And the Consolatio ad Liviam, probably not a contemporary work but one at least that tries to reflect contemporary attitudes, speaks of her as worthy of those women who lived in a golden age, and as someone who kept her heart uncorrupted by the evil of her times. Horace’s description is particularly interesting. His phrase unico gaudens marito is nicely ambiguous, for it states that Livia’s husband was preeminent (unicus) but implies the other connotation of the word: that she had the moral superiority of an univira, a woman who has known only one husband, which in reality did not apply to Livia.

Such remarks might, of course, be put down to cringing flattery, but it is striking that not a single source contradicts them. On this one issue, Livia did not hesitate to blow her own trumpet, and she herself asserted that she was able to influence Augustus to some degree because she was scrupulously chaste. She could do so in a way that might even suggest a light touch of humour. Thus when she came across some naked men who stood to be punished for being exposed to the imperial eyes, she asserted that to a chaste woman a naked man was no more a sex object than was a statue. Most strikingly, Dio is able to recount this story with no consciousness of irony.

Seneca called Livia a maxima femina. But did she hold any real power outside the home? According to Dio, Livia believed that she did not, and claimed that her influence over Augustus lay in her willingness to concede whatever he wished, not meddling in his business, and pretending not to be aware of any of his sexual affairs. Tacitus reflects this when he calls her an uxor facilis (accommodating wife). She clearly understood that to achieve any objective she had to avoid any overt conflict with her husband.

It would do a disservice to Livia, however, to create the impression that she was successful simply because she yielded. She was a skilful tactician who knew how to manipulate people, often by identifying their weaknesses or ambitions, and she knew how to conceal her own feelings when the occasion demanded: cum artibus mariti, simulatione filii bene composita (well suited to the craft of her husband and the insincerity of her son) is how Tacitus morosely characterises that talent. Augustus felt that he controlled her, and she doubtless was happy for him to think so.

Dio has preserved an account of a telling exchange between Augustus and a group of senators. When they asked him to introduce legislation to control what was seen as the dissolute moral behaviour of Romans, he told them that there were aspects of human behaviour that could not be regulated. He advised them to do what he did, and have more control over their wives. When the senators heard this they were surprised, to say the least, and pressed Augustus with more questions to find out how he was able to control Livia. He confined himself to some general comments about dress and conduct in public, and seems to have been oblivious to his audience’s scepticism.

What is especially revealing about this incident is that the senators were fully aware of the power of Livia’s personality, but recognised that she conducted herself in such a way that Augustus obviously felt no threat whatsoever to his authority. Augustus would have been sensitive to the need to draw a line between Livia’s traditional and proper power within the domus and her role in matters of state. This would have been very difficult. Women in the past had sought to influence their husbands in family concerns. But with the emergence of the domus Augusta, family concerns and state concerns were now inextricably bound together.

…Although Livia did not intrude in matters that were strictly within Augustus’ domain, her restraint naturally did not bar communication with her husband. Certainly, Augustus was prepared to listen to her. That their conversations were not casual matters and were taken seriously by him is demonstrated by the evidence of Suetonius that Augustus treated her just as he would an important official. When dealing with a significant item of business, he would write things out beforehand and read out to her from a notebook, because he could not be sure to get it just right if he spoke extemporaneously. Moreover, it says something about Livia that she filed all Augustus’ written communications with her.

After his death, during a dispute with her son, she angrily brought the letters from the shrine where they had been archived and read them out, complete with their criticisms of Tiberius’ arrogance. Despite Tacitus’ claim that Livia controlled her husband, Augustus was willing to state publicly that he had decided not to follow her advice, as when he declined special status to the people of Samos. Clearly, he would try to do so tactfully and diplomatically, expressing his regrets at having to refuse her request. On other issues he similarly reached his own decision but made sufficient concessions to Livia to satisfy her public dignity and perhaps Augustus’ domestic serenity.

On one occasion Livia interceded on behalf of a Gaul, requesting that he be granted citizenship. To Augustus the Roman citizenship was something almost sacred, not to be granted on a whim. He declined to honour the request. But he did make a major and telling concession. One of the great advantages of citizenship was the exemption from the tax (tributum) that tributary provincials had to pay. Augustus granted the man this exemption. When Livia apparently sought the recall of Tiberius from Rhodes after the Julia scandal, Augustus refused, but did concede him the title of legatus to conceal any lingering sense of disgrace.

He was unwilling to promote Claudius to the degree that Livia wished, but he was willing to allow him some limited responsibilities. Thus he was clearly prepared to go out of his way to accede at least partially to his wife’s requests. But on the essential issues he remained very much his own man, and on one occasion he made it clear that as an advisor she did not occupy the top spot in the hierarchy. In ad 2 Tiberius made a second request to return from exile. His mother is said to have argued intensively on his behalf but did not persuade her husband. He did, however, say that he would be willing to be guided by the advice he received from his grandson, and adopted son, Gaius.”

- Anthony A. Barrett, “Wife of the Emperor.” in Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome

#livia drusilla#livia first lady of imperial rome#octavian#fulvia#history#roman#ancient#anthony a. barrett

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Antonia Minor, also known as Julia Antonia Minor or Antonia the Younger (31 January 36 BC - September/October 37 AD)

#antonia minor#julia antonia minor#antonia the younger#daughter of mark antony#wife of nero claudius drusus#mother of claudius#history#women in history#roman empire#roman history

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some of my wind has returned to me, so to speak, for working on this blog. Not that I’ve stopped, as all of those following can tell, nor will I soon be returning to 4 original posts each day – 3 is enough, with one reblog to bring up old information. In fact, that is part of the discussion for today, in a way.

Returning to work has allowed me to return to my love of reading, and while today I will be going to get the new Junji Ito manga (Sensor – I write this on 8/17/21), I have been working my way through the Masters of Rome series by Colleen McCullough.

I’ve suggested reading autobiographies and diaries, and that suggestion doesn’t change.

What I’d now like to suggest are reading stories – fictional or historical, or that strange mix of both – that carry over the lives of multiple people.

The only way I can think to explain that, is to use my current example. The series begins with telling the stories of Gaius Marius and Sulla, two men who set in motion dramatic changes for historical Rome. It goes through to their deaths (along with a host of other side characters), into the life of Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Gaius Octavius – the future Augustus. I’m only on the 4th book right now, but I have already observed an entire generation die off.

My beloved Sulla, the ever-graceful Julia wife of Marius, and of course, Marius himself, are all gone. Their impact continues to be mentioned, to be remembered, but with every book it fades. Even that of Servilia (mother of Brutus), who as a child was terribly impacted by her mother’s adultery, seems to recognize that influence less and less. She has more influences, more nuances, to her life.

And these, too, will fade. Octavius is not yet born, but hinted at in Caesar noting he should find a husband for Atia, mother of Octavius. This will circle back. Another generation will fall, and another rise.

I do not believe this is a common occurrence in series; they tend to focus on one set of characters, and do not show the progression to the rise of others. A Song of Ice and Fire may get close to that, one day, but as of yet I cannot say if it will; nor can I suggest it for such reading as the series is not yet complete.

Masters of Rome is the only series I am familiar with that does this, though I have never sought it out as a thing before. I imagine it may be more common in historical fiction than it is in other genres.

The only other I can think of that may do this (I have not read it so I cannot confirm) is Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

So my suggestion is, if you like history, find a period you enjoy that spans around 100 years, and see if there are any historical fiction written about it. Or, if you’re not into history, I’m certain there are sci-fi and fantasy stories that span generations.

Why do I make this suggestion?

Simply because I do not believe we are ever truly exposed to this. We know it occurs, as we know death occurs, but we are rarely involved in stories that go through multiple perspectives of changing generations and times. We certainly see it around us – my grandparents, my parents, and gradually, the children of friends (maybe my brother – who knows!), and perhaps even their children! We experience it, but I believe we are so close to it, that it often blinds us.

This is a way to remove oneself from the narrative, and look at it through other eyes. Experience it, in a way we live. I feel Masters of Rome captures that. I know the names Nixon and Reagan, the way many in Rome may have known the names Sulla and Marius after a few decades went by – where to the people left who lived with them, they remain huge, notable! To someone like me? Not so much. In my time, I suppose it’ll be figures like Barack and Trump who stand high in my memory, as far as politics go.

Innovations in my mom’s time seem simply normal, or even outdated, like the VHS. Now we have Blu-ray and digital!

I do not think we truly experience multiple generations in the way a novel or even a show, can allow us to – all at once, quickly, and to thus be more keenly aware of the shifts because by our time our reckoning with it – a few hours, a few days, weeks, depending on how fast we read – is far shorter than the time changes occur through generations, which is years. It’s fresh. We wonder at how things are forgotten, so easily cast aside, when it happens all the time.

In a way, it brings us to confront that true horror of thanatophobia that many like to hide behind: that we are not truly dead until we are forgotten. Here we see forgetting even within the same, and next, generations.

Here, we see death. As normal. And here we see moving on, as normal. Here we see lives untouched by the tragedies of these earlier losses. Would my brother’s children, ever be impacted by the loss of great-grandparents they never knew? No. No more than I am, and of those, there is only my father’s grandfather I think I would have liked to know, because he saw something in my dad that my dad should have seen earlier.

Exposure to generational stories and the death inherent in them, the change inherent in them, I think is important. In some ways it is as comforting as it is terrible, because for those with loved ones they’ll leave behind, it shows how families can grow and flourish and be happy after losses. It shows that “moving on”.

I browsed a Reddit thread for ideas (https://www.reddit.com/r/booksuggestions/comments/wdy5f/can_anyone_suggest_fiction_novels_that_span_over/), and so I am including these thoughts as well:

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

Roots by Alex Haley

House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

Kane and Abel by Jeffrey Archer (a part of a series followed by The Prodigal Daughter)

The Mists of Avalon by Marion Bradley

The Sackett series by Louis L’amour

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu

Some of these look quite promising, so hopefully some will appeal. If there are other ideas, I certainly welcome reblogs with contributions!

#death anxiety#death anxiety talk#book recommendation#book recommendations#masters of rome#colleen mccullough#historical fiction#thanatophobia

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Octavius Capp: Son of Caesar

Word Count: 1,429

As mentioned in his genetic profile, Octavius Capp’s hair and eye colors only work should you use hypothetical genetics. For the hair, it would be to assume Julius had either a red or blond allele in his genetic code. For the eyes, it would be to assume that one of his parents (preferably Calpurnia if you want to use as few hypothetical genes as possible) had an allele for light blue eyes somewhere in their genetic code.

That said, if we take external sources into account, there may be another way to explain these errors without using any hypothetical genetics.

Julius & Octavius

The historical Julius Caesar was a father of three children, though he only personally fathered two of them. His eldest biological child was Julia, whose mother was Caesar’s first (or maybe second) wife, Cornelia. His youngest biological child was Caesarion, whose mother was his then-lover Cleopatra VII Philopater.

Unlike Julia and Caesarion, Octavius was not Caesar’s biological son. Instead, he was posthumously adopted by him. Octavius was the son of Gaius Octavius and Atia Balba Caesonia, the latter of whom was the daughter of Caesar’s sister, Julia Caesaris Minor. As such, while related to Julius Caesar by blood, Octavius was initially his great-nephew rather than his son (Caesar would name him his heir in his will filed in 45 BC).

Octavius & the Tria Nomina

Caesar adopting Octavius is reflected in his pre- and post-adoption names. According to Roman naming conventions, or “tria nomina,” a Roman male’s name is made up of three elements — the praenomen, nomen, and cognomen, though not every male possessed all three.

The praenomen was a personal name given to a child by their parents. In many cases, the eldest male child often shared his praenomen with his father. The historical Octavius was his parents’ only son, as he had two sisters Octavia Major and Octavia Minor. As such, his praenomen, Gaius, follows this trend since it was his biological father’s praenomen as well.

The nomen was a “gentile name,” which designates a Roman as a member of a gens (similar to modern-day families). Octavius’ full name reflects this, as his nomen, “Octavius,” denotes him as part of the Octavia gens. This is why both of his biological sisters were named Octavia. For the most part, women in Ancient Rome did not have praenomen, being officially identified by their nomen instead. That said, Roman women could be distinguished from one another using something like numeral adjectives or with suffixes.

The cognomen was another personal name. Unlike a praenomen, which someone received at birth, an individual received a cognomen due to either personal factors or because they earned it. Unlike the hereditary nomen, the cognomen could be either hereditary or bestowed upon an individual. Being used by members of a Julii branch, “Caesar” is an example of a hereditary cognomen. Octavius’s post-adoption cognomen reflects this as he only gained the Caesar cognomen afterward, discarding his former cognomen, Thurinus, as a result.

Julius & Calpurnia

Contrary to the Capp family tree, Caesar and Calpurnia’s actual marriage was ultimately childless. There could be many reasons for this, but the most popular is likely that Calpurnia was supposedly barren. This theory is so popular that Shakespeare alluded to Calpurnia's barren status in Julius Caesar. In the play, Caesar instructs the ceremonial runner, Mark Antony, to touch Calpurnia during the Feast of the Lupercal, which is, according to Roman superstition, supposed to cure infertility.

The Adoption Theory

Octavius Capp being the adopted son of Julius and Calpurnia Caesar makes a lot of sense from both a historical and a Shakespearean perspective. Not only that, but it could easily explain any discrepancies in Octavius’ genetic profile without having to resort to implementing hypothetical genetics for said discrepancies to make sense.

Like all of the theories I post on here, you are not obligated to agree with this one. That said, this is a theory that I personally ascribe to. If you’ve read any of my past essays, you’ve probably realized that my interpretation of Veronaville takes inspiration from external sources, and that is definitely reflected here.

With that in mind, the rest of this essay will be rather headcanon heavy.

Octavius’ Adoption

The first step is to figure out why the Caesars initially adopted Octavius Capp. Personally speaking, I believe the best way to answer this question is by looking at our external sources. As I mentioned earlier, Julius Caesar fathered two children. His only legitimate child, Julia, died in childbirth in 54 BC. Since that child died a few days later, and Julia did not have any other living children, Caesar did not have any descendants through his daughter that he could have named his heir. His biological son, Caesarion, was born in 47 BC, though Caesar never acknowledged him as such despite Caesarion reportedly having Caesar's "looks and manner."

With his daughter dead, and his son unacknowledged, Caesar did not have a true heir, hence why he named Octavius as such in his 45 BC will. Even if Caesar did acknowledge Caesarion, it doesn't change that he was still a toddler when his father named Octavius his heir, so his young age might have caused Caesar to overlook him.

As you can also see, neither of Caesar’s biological children were born from his marriage to Calpurnia. Out of all the historically-inclined Capp ancestors, this trait is unique to the Caesars.

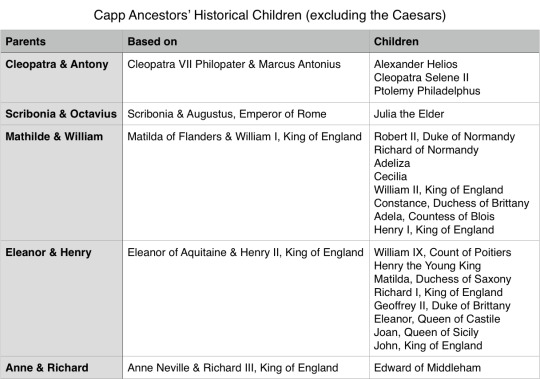

To prove this point, here are all of the other couples who fall under this category, plus any biological children their historical inspirations had together:

While this interpretation is not completely necessary, I also view the Caesars and most other Capp relatives as being not too keen on adoption due to their desire to keep their blood blue. As such, Julius and Calpurnia's decision to adopt may have resulted from their failure to conceive an heir.

When considering the historical context, one could assume that Octavius Capp was also related to Julius Caesar (the sim) by blood. Had Octavius already been part of the Caesar family in some way, then Julius could have ascertained that his adopted son had the blue, Caesar blood required to be his heir.

Lineage and Marriage

When it comes to this theory, it works best if we assume Veronaville’s Caesar family was patrilineal (which I do). This is because, if the Caesars were matrilineal, there would not be any reason for them to forgo any future adoptions after Octavius joined the family.

The question remains, however, as to why the game lists both Octavius and his daughter Contessa as Capps rather than Caesars. Since the game establishes the Capps as matrilineal, I believe that Octavius and Scribonia both kept their original surnames when they got married. Sure, this isn’t possible in a mod-free game, but this can easily be ignored from a story-perspective, especially if you find a way to justify his last name changing later on.

As for Contessa, I interpret that Scribonia and Octavius’ marriage agreement stated that any children they had would inherit the surname of their parent who shares their biological sex. That said, this idea only works if you interpret Contessa as a cisgender female.

Finally, I interpret Octavius’ last name changing as Scribonia’s doing. If you read my feud theory, you might recall that I interpret Scribonia and Octavius’ marriage not being that great. As such, I interpret Scribonia having changed Octavius’ surname after he died by bribing some political officials to get it done.

As a side note, I also believe that she left a provision in her will to ensure that any other male who marries into the Capp family takes the Capp name upon marriage. This belief only really exists to explain why Albany and Cornwall, two sims from other patrilineal families, became Capps when they married into the family rather than retaining their surnames.

Final Thoughts

As a whole, this theory works well enough on its own when taking genetics and external sources into account. That said, I feel the proper headcanons are also required for it to work from a neighborhood narrative angle.

As usual, this is just a theory, so you don’t have to agree with anything I’m saying here. That said, I figured I’d share it as part of the GVGP because it relates to Octavius’ genetic profile.

Once again, thank you so much for reading this extra essay. I’m still working on the next set of sims’ GVGP entries, and I hope to make some progress over the coming days.<3

#octavius capp#veronaville#sims 2#sims#veronaville vault#great veronaville genetics project#gvgp#julius caesar#calpurnia caesar#caesar family

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

91 total Romans and Roman ally/enemies:

Julius Caesar

Pompey Magnus

Crassus

Marcus Brutus

Lucius Brutus

Servilia

Cato the younger

Cato the elder

Cassius

Decimus

Octavian

Augustus

Agrippa

Atia

Sulla

Marius

Bibulus

Sextus Pompey

Gnaeus Pompey

Scipio Africanus

Metellus Scipio

Scipio Salvito

Cornelia (Mother of Gracchi)

Gaius Gracchus

Tiberius Gracchus

Cicero

Quintus Cicero

Labienus

Trebonius

Mark Antony

Lepidus

Ovid

Virgil

Horace

Propertius

Curio

Julia (Caesar’s daughter)

Cornelia (Caesar’s wife)

Caesarion

Sertorius

Fabius Maximus

Clodius Pulcher

Caelius

Catullus

Fulvia

Atticus

King Numa

Cincinnatus

Procillus

Emperor Tiberius

Emperor Caligula

Emperor Claudius

Emperor Nero

Agrippina

Vercingetorix

Ariovistus

Ambiorix

Cleopatra

Hannibal Barca

Hamspicora

Mithridates

Plutarch

Deiotarus

Catalina

Gaius Oppius

Sallust

Masintha

King Juba

Aulus Hirtius

Boduognatus

Cinna

Pliny the elder

Lucullus

Porcia

Mago Barca

Tibullus

Ptolemy XIII

Apuleius

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Major

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Minor

Tigellius

Lycophron

Romulus

Remus

Germanicus

Arminius

Varus

Vespasian

Titus

Scipio Aemilianus

Flavus

Notes:

I am constantly updating this list ^_^

While Octavian and Augustus are the same person, their designs are very different so I counted it as separate.

My list is mostly Romans but I have designed many Greeks as well! I have designed most of the Iliad characters ^,^b

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

You said, "I’m surprised you didn’t ask Mark Antony ;P" and you know what? You're right, I totally should have! So I'm doing it now, if you're willing to answer. ^^

✰ What made you fall in love with them?

I wasn’t actually really interested about Mark Antony until Julius Caesar became one of my historical faves. Reading and watching things about Caesar made me become better acquainted with Mark Antony and I came to really like him. I find him to be an interesting historical figure, and I love his relationship/friendship with Caesar!

✰ Favorite anecdote involving them?

During Caesar’s funeral, Mark Antony agreed to stay calm and reasonnable and not saying anything against Caesar’s murderers. He ended up taking Caesar’s bloody toga to present it to the crowd and pretty much gave a speech in which he accused Caesar’s murderers, which provoked the crowd’s fury as people loved Caesar. I pretty much imagine Mark Antony madly cackling as the crowd rioted and burnt down the conspirators’ houses.

✰ Your favorite thing about them?

he’s a bi icon, loveable idiot and actual human disaster who loves to party and loved Caesar and Cleopatra a lot

While he’s seen as a drunkard who can’t compare with Caesar and Cleopatra and wasn’t a military genius, he was Caesar’s faithful lieutenant and friend, he loved Cleopatra more than his life, was a member of the second triumvirat, and was a deeply human and flawed man who enjoyed life and made no secret of it. He was deeply human, who also loved Greek’s culture, and that’s this humour and humanity I love so much in him.

✰ Your least favorite thing about them?

Aside from the fact he committed suicide and died in the arms of his queen, thus breaking my heart?

✰ Best books about them?

I only know one, in French, Marc-Antoine : Un destin, de Pierre Renucci, thought I read good reviews about Mark Antony: A Life, by Patricia Southern.

✰ Favorite place associated with them?

Rome, of course!

✰ Who do you ship them with?

Caesar Cleopatra!

✰ Favorite friendship?

I love his friendship with Caesar! They were good friends and also relatives, and Mark Antony was often, if not always, supporting Caesar in Rome and during military campains.

✰ Favorite outfit?

I don’t really know…

✰ Favorite event they were involved with?

I would say the Gallic Wars.

✰ Favorite portrayal in film, television, etc? If there isn’t one, who could play them?

I love his portrayal in the mini-series Cleopatra (1999) as well as his portrayal in HBO Rome. It’s actually how I picture him!

actual sunshine boy

✰ Favorite quote about them?

"Mark Antony is an idiot alright, but he’s my idiot” ... what do you mean, this isn’t a quote Julius Caesar said??

✰ Favorite quote by them?

“My heart is in the coffin there with Caesar”

Okay, this isn’t a quote Mark Antony actually said, it’s from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar but this quote gives me a lot of feels!

✰ Three random facts about them?

* Few people know it but he was a distant relative of Julius Caesar! His mother, Julia Antonia, was a distant cousin of Caesar.

* While he’s famous for his romance with Cleopatra, he actually had several wives! His first wife was his cousin, Antonia. His second wife was Fulvia and became a major influence on his political decisions. His third wife was Octavia, Octavius/Augustus’s sister as a political decision, she was the peacemaker between her husband and her brother, and ultimately raised the children Mark Antony had with his fourth and last wife, Cleopatra, after their death.

* He hated Cicero as much as Cicero hated him. Cicero made several speechs against Mark Antony. Thus, the latter ordered his assassination in 43 BC and to nail Cicero’s hands in the Forum (it seemed Mark Antony also never forgave Cicero for ordering Mark Antony’s father in law years before).

✰ Favorite picture/painting of them?

I don’t have one yet, expect the pictures above.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Important Historical Figures and their Zodiacs

Aries: Thomas Jefferson, Bach, Charlamagne

Taurus: Leonardo da Vinci, Adolf Hitler, William Shakespeare, Queen Elizabeth the Second, Florence Nightingale, Ulysses S. Grant, Sigmund Freud, Harry S. Truman, Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Socrates, Malcolm X, Tchaikovsky , Machiavelli

Gemini: Queen Victoria, Ann Frank, Anastasia, John F. Kennedy, George H.W. Bush, Donald Trump

Cancer: Helen Keller, Malala Yousafazi, Alexander the Great, Julias Caesar, George Bush, John Quincy Adams, Emmeline Pankhurst, Rousseau, Henry the 8th, Nelson Mandela, Nikola Tesla, Gregor Mendel

Leo: Napoleon Bonaparte, Barack Obama, Neil Armstrong, Mussolini, Emmett Till, Fidel Castro, Amelia Earhart, Louis the 16th, Bill Clinton, Alexander Fleming, The Virgin Mary

Virgo: Elizabeth the First, Mother Theresa, Lyndon B. Johnson, Augustus, Jesse James, Henry Hudson, Caligula, Genghis Khan, Michael Faraday, John Locke

Libra: Eleanor Roosevelt, Gandhi, Confucius, Jimmy Carter, William Penn, Virgil

Scorpio: Marie Curie, Marie Antoinette, Bill Gates, Christopher Columbus, Teddy Roosevelt, John Adams, Martin Luther, Leon Trotsky, St. Augustine, Voltaire

Sagittarius: Beethoven, Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill, Walt Disney, Mark Twain, Noam Chomsky, Mary Queen of Scots, Jane Austen, Billy the Kid, Nero

Capricorn: Martin Luther King Jr., Mark Antony, Michelle Obama, Isaac Newton, Richard Nixon, Andrew Johnson, Robert E. Lee, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Nostrodomus, Stephen Hawking, Joan of Arc

Aquarius: Abraham Lincoln, Ronald Reagan, Charles Dickens, Thomas Edison, Mozart, Rasputin, Charles Darwin, Frederick Douglass, Rosa Parks, Magellen, Francis Bacon

Pisces: George Washington, Albert Einstein, Galileo, Alexander Graham Bell, Steve Jobs, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Constantine the Great, Nicolaus Copernicus, Michelangelo, Andrew Jackson, Jesus Christ

Source: avoidantgarde

#aries#taurus#gemini#cancer#leo#virgo#libra#scorpio#sagittarius#capricorn#aquarius#pisces#zodiac sign#fun facts#horoscope#zodiac#astrology#facts#fact#weird#weird sign#zodiac signs#aries facts#taurus facts#gemini facts#cancer facts#leo facts#virgo facts#libra facts#scorpio facts

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

for @kinguponthesea‘s c.aesarion

muse: j.ulia c.aesaris | historically divergent au

29 B.C.

Ever since their father had died, Julia and her younger half-brother ( whom Caesar had recognized and legitimized in his will ) had lived together in Rome. Even his mother, the exotic queen, had called Caesar’s villa her home, and it was there where she and her lover, Mark Antony, often held court. Julia’s first memory of little Caesarion was of a small boy hiding behind his mother, his dark hair similar to her father’s. With Caesar’s great assets equally divided between them, it was only natural for there to be no discord between the half-siblings.

While the rest of the Julii protested the legitimacy of the will and of the boy’s, she’d considered him a welcome addition to an otherwise stuffy villa. Antony and Cleopatra could have their parties, and she and Caesarion had their adventures and stories, which grew infrequent as the years passed. Then, he was soon sent off to Athens to study and to receive an education befitting Caesar’s heir, and she...she was left to learn under Cleopatra herself and her father’s widow, Calpurnia.

One taught her how to be a Roman, and the other taught her how to survive in a world dominated by men. She would never raise a sword herself, but her political astuteness was similar to that of her father’s. Her brother was, no doubt, thriving in Athens, and they all eventually received word that he was finished with his studies and was sailing home. Naturally, she and Cleopatra chose to meet him on the coast instead of waiting for him in Rome. She didn’t know what to expect once she saw the ship sail into port, but when she glimpsed a tall, young man of eighteen, she immediately knew who it was.

“Brother. You’ve grown.” She smiled fondly at him, cupping both his cheeks in her hands. He was taller than she was now, and the similarities between him and their father were clear. He did have a few of his mother’s features, but the profile was that of a man of the Julii. Those who still criticized the decision to name him, and not Octavian, as heir, would certainly refuse to see or accept, but such was the will of a dictator. Now, only time could really tell if he lived up to all of their lofty expectations. She, on the other hand, was just glad to have her brother back. “Welcome home.”

As she wasn’t the only one waiting for him, she stepped back to give Cleopatra the chance to see her son. She’d learned how to read, write, and speak Egyptian over the years, so she could easily follow their conversation. However, she made it seem like she didn’t understand, if only to remain polite.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3 generations of antonii + the lovers they committed treason with

mark antony rose to power after the death of julius caesar and allied himself with queen cleopatra vii of egypt; the two soon became lovers, which scandalized rome. antony’s rival, octavian, used his affair with cleopatra as proof that he was a slave to egypt and a traitor to rome. octavian defeated antony and cleopatra in the civil war, and they both committed suicide in 30 BCE. octavian would soon become known as augustus, the first emperor of rome.

iullus antonius, the son of mark antony and fulvia, was involved in a scandal with augustus’s daughter julia and several other elite men in 2 BCE. ostensibly their crime was adultery, but both ancient writers and modern scholars have speculated that there was some degree of political conspiracy to the group’s activities. iullus was put to death and julia was sent into exile, where she died in 14 CE of unknown causes, perhaps starvation.

livilla, the daughter of drusus and antonia minor and therefore the granddaughter of mark antony, was married to emperor tiberius’s son drusus the younger, whom she allegedly poisoned with the help of her lover, the ambitious praetorian prefect lucius aelius sejanus. in 31 CE tiberius had sejanus arrested for plotting to overthrow him. sejanus was strangled and his body thrown down the gemonian steps, and shortly afterwards livilla either committed suicide or was starved to death by her mother.

#historyedit#classicsedit#tagamemnon#ancient rome#mark antony#cleopatra#iullus antonius#julia#livilla#sejanus#rome @ the gens antonia: could you not be dumb treasonous hoes FOR FIVE MINUTES?!#god i love this family

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...While on his travels Augustus would have continued to be preoccupied with the old issue of what would happen after his death. He had clearly demonstrated at the time of his departure that he could not manage without Marcus Agrippa, married at the time to Marcella, Octavia’s daughter. Agrippa now divorced her (her compensation was to be married to Iullus Antonius, the son of Antony and Fulvia), so as to be free in 21 to marry the widowed Julia. Plutarch says that this marriage came about through Octavia’s machinations and that she prevailed upon Augustus to accept the idea. It is not clear what her motives would have been.

If we are to believe Seneca we might see pure spite. He claimed that Octavia hated Livia after the death of Marcellus because the hopes of the imperial house passed now to Livia’s sons. This could well be no more than speculation, and Seneca does not even hint at any specific action by Octavia against her supposed rival. The whole story sounds typically Senecan in its denigration of dead individuals who are easy targets. Once again, we are told nothing about Livia’s reaction to the marriage. She might not have been able to object to the earlier marriage between Julia and Augustus’ nephew Marcellus, but in 21 the situation was different. Her older son, Tiberius, who was not yet married, had been passed over in favour of an outsider to the family.

But whatever his sense of obligation to his wife, Augustus probably felt that he had little choice in the matter. Agrippa’s earlier reaction to having to take second place to Marcellus, a blood relative of Augustus, would have provided a good hint to Augustus of how his friend would have taken to playing second string to Tiberius. Agrippa was now a key figure in the governing of Rome. He was not a man to be provoked. If Livia had been entertaining hopes that this early stage of a preeminent role for either of her sons (and such a suggestion, while reasonable, is totally speculative), such hopes would have faded with the birth of two sons to Julia and Agrippa.

Gaius Caesar was born in 20 bc, and, as if to confirm the line, a second son, Lucius Caesar, arrived in 17. Augustus was delighted, and soon after Lucius’ birth signalled his ultimate intentions by adopting both boys. He thus might envisage himself as being ‘‘succeeded’’ by Agrippa, who would in turn be succeeded by either Gaius and Lucius, who were, in a sense, sons of both men. In late 16 bc Augustus set out on an extended trip to Gaul and Spain, where he established a number of veteran settlements. Livia may have accompanied him. Dio does report speculation that the emperor went away so as to be able to conduct his affair with Terentia, the wife of his close confidant Maecenas, in a place where it would not attract gossip.

Even if the rumours were well founded, the implication need not necessarily follow that he had left Livia behind. Livia had a reputation as a femme complaisante, and Augustus may simply have wanted to get away from the prying eyes of the capital. Certainly at one stage Livia intervened with Augustus to argue for the grant of citizenship to a Gaul, and this trip provides the best context. Moreover, Seneca dates a famous incident to this trip, Livia’s plea on behalf of the accused Gaius Cornelius Cinna. It could well be that Seneca misdated the Cinna episode, but he at any rate clearly believed that Livia had been in Gaul with her husband at the relevant time.

…Agrippa lived to see the birth of two other children, his daughters Julia and Agrippina. The first (born about 19 bc) is the namesake of her mother, and, in the historical tradition, cut from the same cloth; the second was to be somewhat eclipsed in the same tradition by her own daughter and namesake, the mother of the last Julio-Claudian emperor, Nero. Agrippa thus became the natural father of four of Augustus’ grandchildren during his lifetime (a fifth would be born posthumously), and his stock rose higher with each event. He had served his princeps well, and could now take his final exit. In 13 he campaigned in the Balkans. At the end of the season he returned to Italy, where he fell ill, and in mid-March, 12 bc, he died.

His body was brought to Rome, where it was given a magnificent burial, and the remains were deposited in the Mausoleum of Augustus, even though Agrippa had earlier booked himself another site in the Campus Martius. In the following year Octavia died. She is celebrated by the sources as a paragon of every human virtue, whose only possible failings had been the forgivable ones of excessive loyalty to an undeserving husband and excessive grief over the death of a possibly only marginally more deserving son. As noted earlier, we should be cautious about Seneca’s claim that Octavia nursed a hatred for Livia after the death of Marcellus. But there can be no doubt that her death was in a sense advantageous to Livia, for it removed one of the main contenders for the role of the premier woman in the state. Only Augustus’ daughter Julia might now lay claim to a precedence of sorts, but she in fact became an agent in furthering Livia’s ambitions, rather than an obstacle. Once her formal period of mourning was over, Julia would need another husband. Suetonius says that her father carefully considered several options, even from among the equestrians.

Tiberius later claimed that Augustus pondered the idea of marrying her off to a political nonentity, someone noted for leading a retiring life and not involved in a political career. Among others he supposedly considered Gaius Proculeius, a close friend of the emperor and best known for the manner of his death rather than of his life: he committed suicide by what must have been a painful technique—swallowing gypsum. This drastic action was apparently not in response to the prospect of marriage to Julia but in despair over the unbearable pains in his stomach.

In 11 bc, the year of Octavia’s death, Augustus made his decision. He could hardly pass over one of Livia’s sons again. They were the only real choices, given the practical options open to him. Both were married, and Drusus’ wife was the daughter of Octavia, someone able already to produce offspring linked, at least indirectly, by blood to the princeps. Divorce in this case would not have been desirable. Augustus had already demonstrated his faith in Livia’s other son, Tiberius, by appointing him to replace Agrippa in the Balkans. He was the inevitable candidate for Julia’s next husband. In perhaps 20 or 19 Tiberius had married Agrippa’s daughter Vipsania, to whom he had long been betrothed. Their son Drusus was born in perhaps 14. In 11 Vipsania was pregnant for a second time, but Tiberius was obliged to divorce her, although he seems to have been genuinely attached to her. Reputedly when they met after the divorce he followed her with such a forlorn and tearful gaze that precautions were taken that their paths would never cross again.

He was now free to marry Julia. This marriage marks a milestone in Tiberius’ career and in the ambitions that Livia would naturally have nursed for her son. Augustus was clearly prepared to place him in an advantageous position, and the process could be revoked only with difficulty. It is inevitable that there should be speculation among modern scholars that Livia might have played a role in arranging the marriage. Gardthausen claimed that she brought it off in the teeth of vigorous opposition. Perhaps, but the suggestion belongs totally to the realm of speculation. If Livia did play some part in winning over Augustus, she did it so skilfully and unobtrusively that she has left no traces, and the sources are silent about any specific interference on this occasion.

Nor can it be assumed that Augustus would have needed a great deal of persuading. No serious store should be placed in the claims in the sources that he held Tiberius in general contempt and was reduced to turning to him faut de mieux. Suetonius quotes passages from Augustus’ correspondence that provide concrete evidence that the emperor in fact held his adopted son in high regard. Suetonius chose the extracts to show his appreciation of Tiberius’ military and administrative skills, but his words clearly suggest a high degree of affection that seems to go beyond the merely formulaic.

He addresses Tiberius as iucundissime, probably the equivalent in modern correspondence of ‘‘my very dear Tiberius.’’ He reveals that when he has a challenging problem or is feeling particularly annoyed at something, he yearns for his Tiberius (Tiberium meum desidero), and he notes that both he and Livia are tortured by the thought that her son might be overtaxing himself. Livia’s other son, Drusus, although arguably his brother’s match in military reputation and ability, seems to have been quite different from him in temperament. Where Tiberius was private, inhibited, uninterested in courting popularity, Drusus was affable, engaging, and well-liked, and there was a popular belief, probably naive, that he was committed to an eventual restoration of the republic. He had found a perfectly compatible wife in Antonia the Younger, a woman who commanded universal esteem and respect to the very end.

They produced two sons, both of whom would loom large on the stage of human events: Germanicus, who became the most loved man in the Roman empire and whose early death threatened to erode Livia’s popularity, and Claudius, whose physical limitations were an embarrassment to Livia and to other members of the imperial family, but who confounded them all by becoming an emperor of considerable acumen and ability. They also had a daughter, Livilla, who attained disrepute through her affair with the most loathed man in the early Roman empire, the notorious praetorian prefect Sejanus.

Drusus dominated the landscape in 9 bc. The year seemed to start auspiciously for Livia. In 13 bc the Senate had voted to consecrate the Ara Pacis, one of the great monuments of Augustus’ regime, as a memorial to his safe return from Spain and the pacification of Gaul. The dedication waited four years and finally took place in 9, on January 30, Livia’s birthday, perhaps her fiftieth. The honour was a profound one, but indirect and thus low-key, in keeping with Livia’s public persona. Her sons continued to achieve distinction on the battlefield. A decorated sword sheath of provincial workmanship has survived from this period.

It represents a frontal Livia with the nodus hairstyle, and shoulder locks carefully designed so as to flow along her shoulders above the drapery. She appears between two heads, almost certainly her sons, and the piece pictorially symbolises Livia at what must have been one of the most satisfying periods of her life. To cap her sense of well-being, Tiberius, after signal victories over the Dalmatians and Pannonians, returned to Rome to celebrate an ovation. Following the usual practice after a triumph or ovation, a dinner was given for the Senate in the Capitoline temple, and tables were set out for the people in front of private houses.

A separate banquet was arranged for the women. Its sponsors were Livia and Julia. Private tensions may already have arisen between Tiberius and Julia, but at least at the public level they were sedulously maintaining an outward image of marital harmony, and Livia was making her own contribution towards promoting that image. Similar festivities were planned to celebrate Drusus’ victories. Presumably in his case Livia would have joined Antonia, Drusus’ wife, in preparing the banquet, as she had joined Tiberius’ wife on the earlier occasion.

While Tiberius had been engaged in operations in Pannonia, Drusus had conducted a highly acclaimed campaign in Germany. By 9 bc he had succeeded in taking Roman arms as far as the river Elbe. So awesome were his achievements that greater powers felt the need to intervene. He was visited by the apparition of a giant barbarian woman, who told him—she conveniently spoke Latin—not to push his successes further. Something was clearly amiss in the divine timing. Suetonius implies that Drusus heeded the warning, but calamity befell him anyhow. In a riding accident Drusus’ horse toppled over onto him and broke his thigh. He fell gravely ill.

His deteriorating condition caused consternation throughout the Roman world, and it is even claimed that the enemy respected him so much that they declared a truce pending his recovery. (Similar claims were later made about his son Germanicus.) Tiberius had been campaigning in the Balkans at the time but had returned to Italy and was passing through Ticinum after the campaign when he heard that Drusus was sinking fast. Travelling the 290 km in a day and a night, a rate that Pliny thought impressive enough to record, he rushed to be with his brother. He reached him just before he died in September, 9 bc. Drusus was universally liked, and his death at the age of twenty-nine could not seriously be seen as benefitting anyone.

Nevertheless, it still managed to attract gossip and rumours. The death of a young prince of the imperial house would usually drag in the name of Livia as the prime suspect. In this instance such a scenario would have been totally implausible, and Augustus became the target of the innuendo instead. Tacitus reports that the tragedy evoked the same jaundiced reactions as would that of Germanicus, three decades later in the reign of Tiberius, that sons with ‘‘democratic’’ temperaments—civilia ingenia—did not please ruling fathers (Germanicus had been adopted by Tiberius).

Suetonius has preserved a tradition that Augustus, suspecting Drusus of republicanism, recalled him from his province and, when he declined to obey, had him poisoned. Suetonius thought the suggestion nonsensical, and he is surely correct. Augustus had shown great affection for the young man and in the Senate had named him joint heir with Gaius and Lucius. He also delivered a warm eulogy after his death. Even Tiberius’ grief was portrayed as twofaced. To illustrate Tiberius�� hatred for the members of his own family, Suetonius claims that he had earlier produced a letter in which his younger brother discussed with him the possibility of compelling Augustus to restore the republic.

But events seem to belie completely the notion of any serious fraternal strife. Tiberius’ anguish was clearly genuine. His general deportment is of special interest, because of the light that it might throw on his and Livia’s conduct later, at the funeral of Germanicus. According to Seneca, the troops were deeply distressed over the death and demanded Drusus’ body. Tiberius maintained that discipline had to be observed in grieving as well as fighting, and that the funeral was to be conducted with the dignity demanded by the Roman tradition. He repressed his own tears and was able to dampen the enthusiasm for a vulgar show of public grief.

Tiberius now set out with the body for Rome. Augustus went to Ticinum (Pavia) to meet the cortege, and because Seneca says that Livia accompanied the procession to Rome, it is probably safe to assume that she went with her husband. As she travelled, she was struck by the pyres that burned throughout the country and the crowds that came out to escort the funeral train. The event provides one of the few glimpses of Livia’s private emotions. She was crushed by the death and sought comfort from the philosopher Areus. On his advice, she uncharacteristically opened herself up to others. She put pictures of Drusus in public and private places and encouraged her acquaintances to talk about him.

But she maintained a respectable level of grief, which elicited the admiration of Seneca. Tiberius may well have learned from his mother the appropriateness of self-restraint in the face of private anguish. It was an attitude that was later to arouse considerable resentment against both of them. During the funeral in Rome, Tiberius delivered a eulogy in the Forum and Augustus another in the Circus Maximus, where the emperor expressed the hope that Gaius and Lucius would emulate Drusus.

The body was taken to the Campus Martius for cremation by the equestrians, and the funeral bier was surrounded by images of the Julian and the Claudian families. The ashes were deposited in Augustus’ mausoleum. The title of Germanicus was posthumously bestowed on Drusus and his descendants, and he was given the further honour of statues, an arch, and a cenotaph on the banks of the Rhine. Augustus composed the verses that appeared on his tomb and also wrote a prose account of his life. No doubt less distinguished Romans, of varied literary talent, would have written their own contributions.

The anonymous Consolatio ad Liviam represents itself as just such a composition, intended to offer comfort to Livia on this very occasion, although it was probably composed somewhat later. Livia was indeed devastated, but as some form of compensation for her terrible private loss, she now, after some thirty years in the shadows, came into greater public prominence. The final chapter of Drusus’ life seems to have opened up a new one in his mother’s.”

- Anthony A. Barrett, “In the Shadows.” in Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arrivals & Departures

01 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus [Claudius]