#father of history

Text

#classics memes#classics#ancient history#herodotus#ancient history memes#homer's odyssey#the odyssey#classical studies#greek mythology#tagamemnon#ancient greece#ancient greek#ancient rome#herodotus blogging#ancient literature memes#herodotus’ histories#odysseus#father of history#history memes#homer#the iliad#the illiad memes#illiad memes

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seminars of “Herodotus Helpline”in April-June 2023

“Upcoming seminars

April-June 2023

18 April (NB: Tuesday): Maurizio Giangiulio (Trento)

After so many years. From Herodotus’ sources to oral tradition and social memory

26 April: Jan Haywood (Leicester)

Reading Herodotus

3 May: NO SEMINAR

10 May: Giusto Traina (Sorbonne)

Media and Armenia in Herodotus’ list of satrapies

17 May: Reading session: 5.42-48 (the fall of Sybaris)

24 May: NO SEMINAR

31 May: Claudio Felisi (Sorbonne)

Where do the names of the Greek gods come from? For a (partly) new reading of Herodotus’ answer

7 June: Alexander Schütze (Munich), Andreas Schwab (Kiel) and others

Herodotean soundings: the Cambyses logos

14 June: NO SEMINAR

21 June: Paul Cartledge (Cambridge)

Commentating on Herodotus: the Cambridge Green and Yellows

28 June:Translating the Histories”

Source: https://herodotushelpline.org/seminar-schedule/

HERODOTUS HELPLINE

A world-wide community dedicated to the father of history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

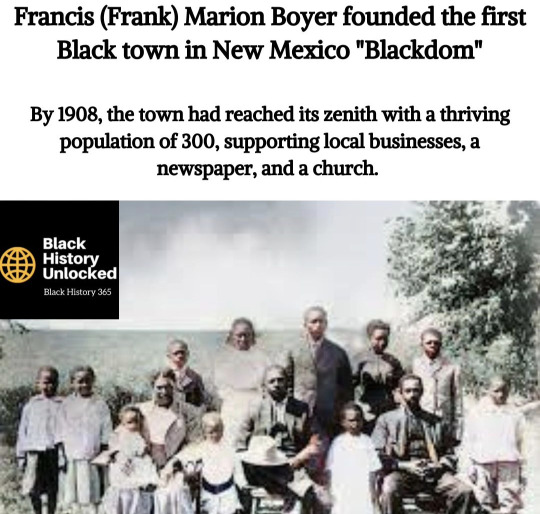

#blackmen#melaninpoppin#blackcouples#blackwomen#blacklove#blackfamily#blackfathers#melaninrich#marriedandblack#blackexcellence#black history#black man#black fathers

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Linda Martell - "Color Him Father" (1970)

**Beyoncé's latest album 'Cowboy Carter' spotlights Linda Martell, a pioneer and trailblazer who paved the way for Black country music artists, as she was the first commercially successful Black female artist in the genre.

#linda martell#color him father#1970#color me country#the linda martell show#beyoncé#beyonce#cowboy carter#renaissance act ii#music#country music#black music#black artists#black history#black women#african american#paying homage#icon#video#sbrown82

861 notes

·

View notes

Text

referencing this comic bc i realized klav would probably tell apollo,, bc he love loves apollo,,, and this

#klapollo#klavier gavin#kristoph gavin#apollo justice#ace attorney#what ever happened to the young young brothers? father took a shot and ma got poisoned coughing blood on the sheets blo blood on her knees#bloody history#mein bruders got a gun#you'd better run#bad kid bad kid#had to do it#but he had to do it he had to do it#he had to kill ma#they couldnt not#they had to face off#hes not a bad kid but he had to do it#aa4

469 notes

·

View notes

Text

pietà

#TY LETTIE FOR THE COMM AND FOR THIS ABSOLUTE TREASURE OF A REQUEST. IM SO ILL ITS SO SICK AND TWISTED (POSITIVE)#silver in the depths of despair but still holding his father close. with love and compassion and mourning who he is and what has happened#surrounded by the nothingness. nothing but blot and misery. lilia still untouched and kept safe. the lil halo glow OUGUGHH#the RING being blotted. the blot winding up his arm like the pricked finger on the spindle iM GNAWINF THE BARS OF MY CAGE GRGAHGAHH#WHEN I TELL U THIS IS THE SINGLE BEST COMM REQUEST IN THE HISTORY OF EVER. WHEN I TELL U LETTIES MIND IS SO POWERFUL#im normal. ty b i love u so much <3#twst#twisted wonderland#twst silver#lilia vanrouge#suntails#i will never be normal again. hope this helps

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

#dinosir#puppet history#garrett watts#the professor#watcher#shane madej#all hail the watcher#shane and ryan#watcher entertainment#ryan bergara#steven lim#father's day

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#black community#original photographers#black people#graphic design#black art#fashion#outfit#artwork#america#black culture#black men#black power#black history#black history month#black woman#blacklivesmatter#black tumblr#african art#father and son#black fathers

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was just looking into the notion that widowers only had to mourn for 1 year after their wives' deaths, during the Victorian era, while widows had to mourn for two. because I've heard that a lot, but it seems to jive more with the Pop History version of the era where mourning existed because Imposing Rules On People Is Fun and All Marriages Were For Money than with the real version, inhabited by real people who idealized love matches and theoretically practiced formal mourning to show that they were going through something and needed gentle treatment

what I've gathered from a brief search for period sources seems to be:

one source from 1839 mentioned the "widows = 2 years; widowers = 1 year" thing

every other source I read (about 7, from various points in the era) implied or stated that the minimum normal period of mourning for widows and widowers was the same

That's a small sample size, but I still think it's significant

men's clothing could often be harder to visibly alter to reflect mourning, relying heavily on things like black cufflinks and collar studs that could be trickier to notice at first glance than. you know. a bonnet with a black veil over someone's face

a lot of sources talking about mourning clothes were fashion magazines aimed at women, and thus would be more likely to talk about women's mourning attire than men's

so my takeaway is that while some people at some parts of this 60-year period felt it acceptable for widowers to mourn for half the period of widows, many others at other times expected any bereaved spouse regardless of gender. obviously, in a highly misogynistic society, women's adherence to ettiquette could be much more scrutinized than men's; a widower who married six months after his wife's death would be looked askance at, but probably not subject to as much censure as a widow who did the same. and obviously, things don't go according to plan and the formal mourning system could of course backfire- forcing a woman into months of social seclusion for an abusive husband, for example

but.

the overall goal was to convey "handle with care" to the outside world. for many people, widowers were expected to need as much care as widows- and therefore to mourn for the same length of time

#victorian#victorian mourning#history#social history#a friend in my costumer circle said she wished she'd had a better way to signal her bereavement when her father died (she was 17)#because nowadays there really isn't a way to convey the same 'handle with care' message#so she really saw the utility of codified mourning signals

577 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are not the same.

Some folks: SJM foreshadowed a blood duel between Azriel and Lucien in the Bonus Chapter to win Elain’s heart/claim his mate.

Me, an intellectual: SJM foreshadowed the blood duel in regard to Lucien because he will use it to save Elain’s life, likely from Beron, because this time he will be powerful enough to stop Jesminda’s fate from repeating itself again.

#elucien#pro elucien#elain x lucien#elucien head canon#anti e/riel#yall this is called a red herring#this is clearly Zuko’s story from ATLA where he was helpless and lost everything to exile by failing to fight his father in a duel#but when faced in a duel again he will prove his power against his horrible dad#Lucien was willing to lay down his life for Feyre his friend#don’t you realize he is going to do the same for his mate?#and he’s going to WIN and save her because there’s no way in hell he will let history repeat itself#especially for his mate#Lucien would never blood duel out of jealousy#he acts with honor and loyalty#yall will see#this is a story of his growth and coming into his own power too and getting justice from his father#and I just know Elain is going to help him in some way#pro lucien vanserra

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

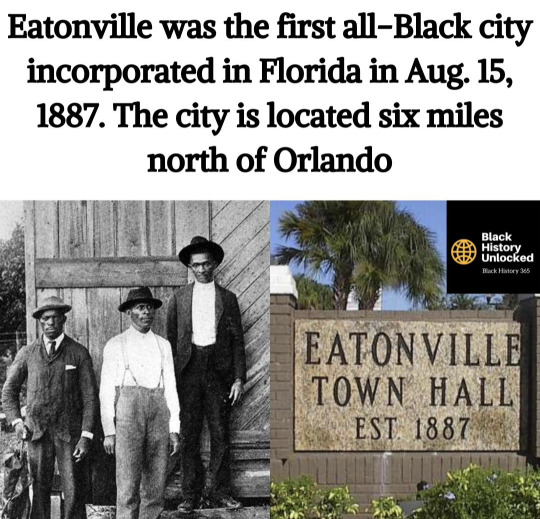

My goodness!!!

#incel#violence against black women#violence against black girls#Samyia Spain#brooklyn#new york#deli#stabbing#twin sisters#veo kelly#park slope#assault#murder#criminal possession of a weapon#rejection#aggression#tragedy#violence#investigation#search#criminal history#robbery charges#community reaction#vigil#grieving father#women's safety#pressure to give phone numbers#public gathering place#neighborhood impact#emotional toll

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

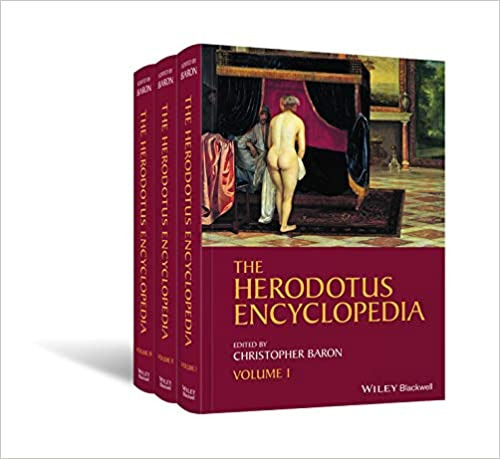

A second review of the Herodotus Encyclopedia in Syllogos, by Dr. Maren Elisabeth Schwab (with some thoughts of mine on it)

“REVIEW DISCUSSION

BARON, Christopher. 2021. Herodotus Encyclopedia, 3 vols. Hoboken NJ: Wiley Blackwell. $595.00. 9781118689646.

Maren Elisabeth Schwab

The Herodotus Encyclopedia, three volumes edited by Christopher Baron and published in 2021 with Wiley-Blackwell, is dedicated to no less a figure than Herodotus himself: ‘To Herodotus: 2,500 years and still going strong.’ Is he really? And, one might ask, was he always? But the massive volumes, amounting to 1653 pages, speak for themselves: at least for now, Herodotean studies are thriving. There are good reasons to toast his birthday.

A total of 181 scholars have contributed thousands of entries to the Encyclopedia from universities all around the world, mostly Anglo-Saxon and European. It is particularly fortunate that scholars from institutions in Herodotus’ home countries, Turkey and Greece, are also among the contributors. Their aim — as ambitious as it is welcome to any future reader of the Encyclopedia — was to be as comprehensive as possible and at the same time up to date with today’s Herodotean studies.

The topics are wide-ranging: the history of the text; scholarship and reception; the historical, intellectual and social background of Herodotus’ world, including religion and warfare; Herodotus’ historical method and literary techniques; and prominent themes in the work. In addition, every single one of the 2,000 names that occur in the Histories is covered by an entry. Indeed, the very first article is the result of this decision: the letter ‘A’ starts with ‘Abae’, a sanctuary that rivalled Delphi during the Archaic period. The location of Herodotus’ Abae, and thus of one of the six oracles tested by Croesus (1.46.2), was only identified by the excavator Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier in 2010. The article further refers to the keywords ‘Dedications’, ‘Temples and Sanctuaries’ and ‘Warfare’. We already find ourselves zigzagging through Herodotean topics and worlds.

In fact, each article of the Encyclopedia is accompanied by an inspiring ‘see also’ section as well as an often admirably detailed bibliography, although the reader is warned in the introduction that bibliographical references will only extend to works published before 2016. This should not come as a surprise to anyone: as is usual with venerable ancient authors in general, Herodotus too has instigated a long torrent of scholarship that has stretched over the past 600 years. The average scholar of today only occasionally hits the tip of this enormous iceberg, but the contributors to the Herodotus Encyclopedia have clearly done their best to let this first collision lead to a far-reaching expedition into the beauties and furrows of the unknown continent below.

This whole new world has a map: the introduction to the Encyclopedia provides an interesting insight into its making by showing the template or synopsis that served as a finely meshed net to identify the topics of the entries. It reveals three main headings: ‘Text’, ‘Context’ and ‘Histories’. For me, as a scholar fascinated by the history of reception, it was most interesting to see that the heading ‘Text’ not only includes the obvious sections on transmission and editions, but also translations as well as scholarship on Herodotus of all ages (except medieval): antiquity, renaissance, early modern, modern 1 and 2 (fittingly using the end of the Second World War to mark a divide: 1750–1945, 1945–2018). This is separated from a second section in the same chronological order that is dedicated explicitly to ‘Reception’, thus making sure any engagement with Herodotus and his work is considered — that every little bit of plankton that has ever emanated from the enormous iceberg to float around the ocean is captured by the mesh. What is before us is clearly one of the boldest undertakings in Herodotean scholarship that has ever seen the light of day.

In the fifteenth century Herodotus met Hesiod and strolled through Ferrara with him. Or rather, this is what Girolamo Castelli, later the medical doctor of the Este family in Ferrara, envisioned in a poem that he wrote for his teacher of ancient Greek, Guarino da Verona.1 In the poem, Herodotus told Hesiod about his work: the beginnings of great kingdoms, the damage they caused in his Asia, and what first led the barbarian hosts to Europe and involved the various forces in battles. Finally, he listed the rivers, peoples and places that he described in the Histories. Indeed, most recipients did not read Herodotus for his battle accounts or his judgement on the Persian war. They read him for his astounding stories about travels to unknown countries that reached the ends of the world. Just like Hesiod in Castelli’s poem, most readers found it hard to believe what Herodotus had to say about them. From Cicero onwards, he had the ambiguous reputation of being both the father of history and the father of lies. Accordingly, the term ‘Liar School’ has earned itself its own entry in the Encyclopedia. In modern times, as the author Melina Tamiolaki informs us, it was first coined by W. Kendrick Pritchett in 1993, who then defended Herodotus against this unfavourable image (Encyclopedia, p. 804). Its main advocate had been Detlev Fehling who, in the 1970s and 1980s, argued that Herodotus deceived his audience through fictitious testimonies and witnesses. Still, the issues of ‘Source Citations’ as well as ‘Deception’ and ‘Reliability’ receive their own entries in the Encyclopedia — hence we may excuse the fact that we can only find the entry ‘Father of History’ (Cic. Leg. 1.5), while the term ‘father of lies’, which was added later by Jean Luis Vives,2 is omitted. It still seems like a legitimate approach to follow one’s curiosity and fascination for the other, the foreign and the barbarian. What is it, then, that our storyteller Herodotus said about peoples and their customs on the periphery? And what can we find out about it when consulting the Encyclopedia, even though this information earned Herodotus the reputation of being a notorious liar?

Browsing the Encyclopedia, we quickly learn some astonishing details, such as that the Ethiopians owed their longevity (on average, 120 years) to a diet of boiled meat and milk, while the Persians were forced to eat themselves during their failed attempt to conquer the Ethiopians — just look up ‘Anthropophagy’ and follow the threads. It is also fun to look up one of the best-known and most debated passages in Herodotus’ Histories: the giant gold-digging ants from India (3.102–5). Since the story is very much worth reading in the Herodotean original, Klaus Karttunen, the author of the entry ‘Ants, Giant’, wisely only gives a very short summary. What he provides is a survey of the attempts to explain the phenomenon described by Herodotus that has made many scholars scratch their heads. According to Karttunen, ‘a number of theories have been proposed as explanation, but few seem convincing’ (Encyclopedia, p. 92). We get to know that the most popular was proposed by the Dano-French geographer Conrad Malte-Brun (1775–1826) who suggested that we identify the ants with marmots. Apparently, he had already found himself in a similar situation as Karttunen: ‘Si l’on nous demandoit de faire un choix entre ces diverses explications, nous serions fort embarrassés, car aucune d’elles n’est exempte d’objections le plus graves; nous sommes donc tentés d’en proposer une nouvelle dans laquelle on peut faire entrer ce que les autres offrent de plus plausible.’3 In the following, Malte-Brun carefully addressed the animals as certain ‘quadrupèdes qui s’y creusaient des terriers’4 and referred to an article on the travels of William Moorcroft, who among those animals that he had seen described one as being ‘de couleur fauve, deux fois gros comme un rat, ayant les oreilles plus longues, mais n’ayant pas de queue’. The question of whether these creatures should be identified with simple marmots is then discussed in a lengthy footnote.5 Karttunen does not seem convinced, as ‘it is not clear how peaceful marmots were turned into ferocious ants’. He prefers the sober explanation that it was ‘a story invented by traders bringing gold from Siberia or somewhere else in order to hide its real origin’ (Encyclopedia, p. 92). Going through the original Herodotean text, we find a short remark at the end saying that ‘this is how the Indians mine part of their gold, as the Persians say’ (3.105.2). It was they who brought the difficult riddle into the world!

One famous passage that, from the Renaissance on, has often been cited to illustrate Herodotus’ technique of telling remarkable tales through the voices of other people is the story of King Mycerinus and his twenty wooden figures of concubines (2.129–131). Ian Moyer, in his entry on ‘Mycerinus’, appreciates the passage in a striking way: ‘In a moment of rational criticism, however, Herodotus points out that the hands of the statues lay on the ground nearby and had simply fallen off. The origin of these stories is uncertain, but they certainly show the extent to which Herodotus structured his account of Egypt around the monuments and material remains he saw’ (Encyclopedia, p. 944). The tension between uncertainty and certainty, even though it is sometimes difficult to bear, is part of the beauty of Herodotus’ writing.

Herodotus’ first important defender against the critical voices who had damaged his reputation, from antiquity on, was Henricus Stephanus (or Henri Estienne), the renowned printer from Paris who published his Apologia pro Herodoto in 1566 together with the revised Latin translation of the Histories by Lorenzo Valla. Lacking an article of his own, he is mentioned eight times in the Encyclopedia. He might surely have deserved more. A little more heart-warming is the treatment of the next big figure, who revived (or should we even say reinvented?) serious Herodotean scholarship in the twentieth century: Arnaldo Momigliano, who taught us to read the Histories. Not only can the scholar who coined the famous phrase ‘There was no Herodotus before Herodotus’ boast of his own two-page entry (written by John Marincola), but he can also be seen face to face in a portrait illustration, from which he fixes the reader with his stern gaze (Encyclopedia, p. 925). Wearing thick glasses and a large collection of pens in his jacket pocket, he presents a constant reminder that Herodotus’ practices and methods are neither entirely known to us nor outdated. This is one of fifty-four illustrations in the Encyclopedia that mostly show archaeological findings, such as inscriptions, reliefs or vase paintings.

Maybe it is a matter of good fortune, after all, that the Encyclopedia, spanning three volumes, is so expensive that it will only be bought by big university libraries. That way, more readers will hopefully access the slightly more affordable e-version of the book and thereby overlook the cover illustration. In the face of such a wealth of appropriate illustrations, we may wonder why it prominently shows the naked body of the unnamed wife of King Kandaules from a seventeenth century Dutch oil painting by Eglon van Neer. True, the story was told by Herodotus in the first book of the Histories (1.8–13) — but so are many more. The Encyclopedia does not need to introduce itself with any illustration at all, not to mention one like this, which immediately brings to the fore so many controversial topics that go far beyond Herodotus and his fascinating work. Herodotus was not a schoolboy eager to get a glimpse at a female body, as the picture suggests. Herodotus was the ‘Father of History’. His Encyclopedia is a milestone. It will be helpful to students and teachers, scholars and enthusiasts. May it have many readers in the future. And may it show its readers the way to the original: Herodotus’ Histories: ‘2,500 years and still going strong’.

1 Sabbadini 1916: ii. 423, verses 11–18 (no 778A).

2 Vives 1612: ii. 87: Herodotus, quem verius mendaciorum patrem dixeris, quàm quomodo illum vocant nonnulli, parentem historiae (emphasis mine)

3 See Malte-Brun 1819: ii. 380 (‘If we were asked to choose between these various explanations, we would be greatly embarrassed, for none of them is free of the most serious objections; we are therefore tempted to propose a new one in which we can include what the others offer that is more plausible’).

4 Malte-Brun 1819: ii. 380 (‘Quadrupeds that dig themselves burrows there’).

5 See Malte-Brun 1819: i. 311–12 (‘of fawn colour, twice as big as a rat, having longer ears, but not having a tail’).

Bibliography

Malte-Brun, Conrad (1819), Nouvelles annales des voyages, 2 vols. (Paris).

Sabbadini, Remigio (1916), Epistolario di Guarino Veronese, vol. 2 (Venice).

Vives, Jean Luis (1612), Libri XII De Disciplinis (London).

Source: https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/syllogos/article/view/92813/87445

Dr. Maren Elisabeth Schwab (source: https://www.klassalt.uni-kiel.de/de/abteilungen/mlat/eschwab)

Very informative review of a monumental work!

Moreover, I agree totally with Dr. Schwab that the cover illustration of the Encyclopedia is unfortunate. However, I think that her presentation of “Turkey and Greece” as Herodotus “home countries’ is also unfortunate: if Halicarnassus, a Greek colony on the SW coast of Asia Minor and Herodotus hometown, is now in Turkey, Herodotus was Greek and the term “Turkey” was unknown to him and to all his contemporaries (the Turks invaded Anatolia and reached the Aegean sea and Halicarnassus only 1500 years after Herodotus’ demise). I doubt, moreover, that Herodotus (a pre-Islamic pagan author, and a Greek one) is seen by most Turks today, whether they are Islamists or secular nationalists, as an important figure and part of their heritage. These remarks don’t mean of course that I reject contributions by Turkish scholars to the Herodotean studies.

I add also the observation that the characterization “father of lies” was not a creation of Vives, but of Plutarch (or perhaps Pseudo-Plutarch), who as Boeotian aristocrat was very angry at Herodotus because the latter described (correctly!) the shameful attitude of the Boeotian oligarchs during Xerxes’ invasion, but also because Herodotus would be philobarbaros (”barbarian lover’!).

More particularly concerning the intriguing story with the giant ants to which Dr. Schwag refers with well justified humor, I will repeat here with some modifications what I had written in an older post of mine, because I think that it contains useful information about what important scholars said on this story and its context (https://aboutanancientenquiry.tumblr.com/post/651614780088598528/google-scholar-and-the-very-admirable-methodology ):

The story is reported in 3.103-104 of “Histories” and I will not reproduce it in its entirety here, as this would have made too long an already long text.

In summary, it is reported that there are in the desert of NW India ants of a size smaller than a dog, but larger than a fox, which are digging their dwellings under the ground, mounting thus up the sand of the desert, which is rich in gold. The Indians come with camels, they gather this sand, and they ride back the swiftest possible, as the ants are extremely fast and dangerous. This is how they obtain the gold which are obliged to send as tribute to the Great King of Persia.

Now, first of all Herodotus never says that he visited India and observed himself the giant ants. He attributes this story to the Persians (”as the Persians say”, and he specifies that some ants have been captured and brought to the Persian court, obviously according to his source). We have seen moreover that he has warned his audience that he includes in his work stories that he does not necessarily believe, although he finds that they must be recorded.

Secondly, India is for Herodotus and more generally for the Greeks of his time a part of the “fringes” of the world, a place so far away and so exotic that many extraordinary things may happen there and for which obviously there was not available much reliable information.

Thirdly, scholars have proposed some explanations for the origin of the story. Thus, the French ethnologist M. Peissel has recorded a tradition among tribal people in N. Pakistan, according to which their ancestors were collecting for generations the gold dust brought to the surface by marmots digging their burrows in the gold rich ground of the Deosai Plateau. For Peissel, Herodotus’ story with the giant ants may be the result of a confusion of his source, caused by the fact that the old Persian words for “marmot” and “mountain ant” sound similar, an explanation that a note of The Landmark Herodotus edition finds “ingenious and plausible”.

Other scholars (among them D. Asheri, p. 498-499 of the Oxford “Commentary on Herodotus Books I-IV” of Ashari-Lloyd-Corcella) link the giant ants story to folk tales about tresors guarded by dangerous fabulous animals and more particularly to the “gold of the ants” of the great Indian epic Mahabharata.

But let’s not lose from our sight what is more generally the Book III of “Histories”, in which the giant ants story is placed.

Book III, despite its part concerning geography and ethnography of the “fringes” of the known to the Greeks world, is not just or mainly a collection of marvels, fables, and fabulous stories about mythical animals, as some see more generally Herodotus’ work, and should not be judged exclusively or mainly on the basis of the story of the “giant ants”.

Book III is a work which covers events of great importance, which happened on three continents in the decade of 530-520 BCE. These are mainly the Persian conquest of Egypt, the subsequent entreprises and the “madness” of the Persian king Kambyses, his death and the usurpation of the throne by a Pseudo-Smerdis with the help of the Magi, the killing of Pseudo-Smerdis by a group of conspirators, the extremely important Constitutional Debate among the conspirators after the killing of the usurper, the crisis of the Persian Empire and its restabilization by Darius I, but also the rise and fall of Polycrates of Samos and of his “thalassocrassy” and the expansion of the Persian domination in the Eastern Aegean sea, which paved the way for the conflict between the Persian Empire and the city-states of continental Greece. It contains also rich information about the organization and administration of the Persian Empire and on the tributes of the subjugated peoples to the Great King of Persia.

According again to D. Asheri (Introduction to the Book III in the “Commentary” of Asheri-Lloyd-Corcella, p. 394) :

“Book III is therefore not only a masterpiece of ancient narrative art, but also an indispensable source for every historical reconstruction of the Persian Empire and of Eastern Aegean in the decade between 530 and 520 BCE. In all of ancient historiography there does not exist a work of superior or equal value. “

But I will close this review of a review by reproducing once more some very pertinent, true, and beautiful remarks of Dr. Schwab about the monumental Herodotus Encyclopedia:

...the massive volumes, amounting to 1653 pages, speak for themselves: at least for now, Herodotean studies are thriving. There are good reasons to toast his birthday.

...Herodotus was the ‘Father of History’. His Encyclopedia is a milestone. It will be helpful to students and teachers, scholars and enthusiasts. May it have many readers in the future. And may it show its readers the way to the original: Herodotus’ Histories: ‘2,500 years and still going strong’

...

1 note

·

View note

Text

Medieval peasants did not behave in a manner modern social scientists think of as optimal for their circumstances.

--Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England.

(Dr. Hanawalt explains that there is no real evidence that English peasants were living in or even particularly acknowledging the existence of extended kinship groups in the 14th-15th century, no matter how much anthropologists think they should have been.)

#barbara a hanawalt#the ties that bound: peasant families in medieval england#history#england#kinship#medieval history#english did not have a word for COUSIN until borrowing it from french#english did not have a word for AUNT#there was a word for a father's brother#for nuclear family#and that was IT

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

He is THE ideal man and I’ve been ensnared

#twst#twisted wonderland#twst trein#twst mozus trein#mozus trein#twst mozus#would I fuck that old man?#would#I’m sorry he can’t be a great father great (widowed) husband AND age like fine wine AND!! be a history man like cmon

575 notes

·

View notes

Text

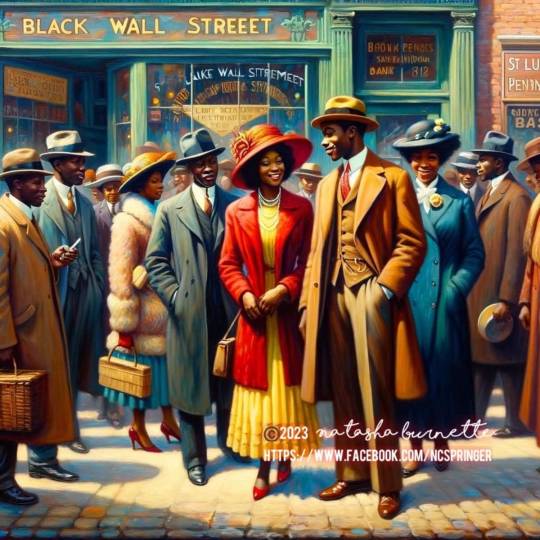

#black art#black artist art#black wall street#Art work by Natasha Burnette#History#Black advancement#Black Elagence#1921#Tusla#oklahoma#Racism#Racist white people who did not like black people to do better than them.#Mass murder of innocent black people#Started by a lie by a white person#Destroy and burning of a black advanced black section of town called Greenwood.#Innocent people loss they family members#Innocent children of that tragedy loss they mother or father.#Innocent children where force to grow up with out a mother or father.

378 notes

·

View notes