#editorial and authorial and fandom

Text

it's a little bit sad how absent babs is from most batfam content considering she was literally one of two headliners on the original 1975 batfam run

#misogynyyyyy#editorial and authorial and fandom#if we're being hashtag real about it#much has changed since then but i think the ways in which they have changed are very telling#the batman family (1975)#batfam#barbara gordon#batgirl#barbara gordon batgirl#babsgirl#dick grayson#robin#dick grayson robin#dc#dc comics#comics

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

re prev post man that's such a real take on the whole doomed by the narrative deal and i think especially in these comic book fandom circles of sparse literary analysis i really have found it interesting to see so many people apply it to character arcs that simply don't fit. my two cents are that the only truly 'doomed by the narrative' characters in detective comics comics are ollie & hal in 1994 where they're literal victims of the larger narrative at play and not actual authorial intent (and the two can be separated because the authors of their respective stories had jumped ship at that point and their deaths were editorial mandates to make way for connor & kyle, as in this wouldn't have been the natural/intended conclusion of the story told before then). and this is why 'emerald twilight' & 'where angels fear to tread' are the single most effective & heartbreaking arcs ever published because there's no other option but death. the tragic hero is complete etc etc

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m guessing no one reading this actually needs to hear this, but for my own peace of mind I wanted to be really clear that while I have made (and will continue to make) comments questioning certain editorial decision in Peter Jackson’s Get Back, they in no way imply a dislike, rejection of, or opinion that the film isn’t good or shouldn’t be enjoyed or that I don’t enjoy it.

The process of interrogating beloved texts is a healthy part of media critique, self-knowledge, and fandom itself. Especially when the media in question purports to tell a true story, parsing out what is true, what is factual, and what is authorial/editorial commentary is in fact a necessary function. Not everyone needs to engage in this function, and shouldn’t be compelled to, but it’s kind of what we, as a society, should do. It’s one aspect of fandom and critical thinking=/=hatred or rejection but in fact its opposite.

Again, I doubt anyone actually reading this requires that explanation, because most of the feedback I’ve gotten is positive, but I feel compelled to give it anyway, because I find it troubling not only in fandom but in many quarters of public discussion, one cannot raise issues or have questions without it being treated as an attack, no matter what mitigating language you put around it. I Love a Thing, Therefore I Must Understand it. That’s all.

#update: I've contacted some folks who have interviewed PJ in the past and they are not unaware of these concerns#so there's that#part of the reason I'm posting this is so that anyone who IS interested in these topics can feel free to converse with me#beatles meta#get back meta#kris talks a lot

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m honestly shocked that so few people talk about how one of DC’s biggest issues in terms of writing is that a lot of their female characters are reduced to often inconsistent plot devices, especially female characters of colour. Like they either ignore it or blame ANYONE but the writers & it just- it baffles me honestly?? Like, yeah editorial plays it’s part but the writers are the ones who will completely contradict everything that’s been established about a female character to make her fit into a man’s storyline better or to move his plot along or give him angst, regardless of who she is as a character in her own right & people refuse to acknowledge how that weakens authorial integrity! Like there are so many examples- Talia, a lot of what happens w Jade, the way a lot of the last couple of decades of Babs content has been written, Selina, Cass, etc- they’ve all been fucked over or nerfed to better fit into the stories male writers wanted to tell about men (stories that often times border on the territory of “illogical power fantasy”) or to fit male writers’ romantisexual fantasies about them. Yet often times the blame is laid onto the female characters themselves (again, this is tenfold for the characters who are woc) even if what was written about them was so wildly out of character it was asinine/smth they never would’ve done it they were a real person w agency based on their previous characterization. & bc fandom won’t even acknowledge this with male writers it’s impossible to get them to acknowledge when white female authors repeat this trend with characters of colour. So, yeah, I don’t really know where I was going with this but I guess I just wanted to say thank you for being one of the few people who’s like actually willing to talk about this despite the shitty anons it gets you. Your commentary on comics is always really insightful & you’re a pleasure to see on my dash lmao. Best wishes!

you really put it into words like it’s so awful having to see so many of these characters mutilated bc of how writers view them! and even worse when readers blame it on the characters and not the writers who carelessly used them

#asks#the more i reread about jade esp the more off putting i find people who hate her#things are almost never in her favor it’s bizarre

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPM ‘Majin’ Drama CD Reviews. Part 0 -- Setting

Introduction

So, because nobody else has, I thought I’d review the set of audio books that ONE produced for OPM in 2017. There were four volumes and the ‘serious’ drama parts are original stories that have been wonderfully transcribed into English for us, available here. They are canon but are funny, informative and more than a little mad. I’ll be posting one every Sunday that there isn’t a manga or webcomic update.

A short note on the dangers of fanon

When I sat down to look over the set as a whole, I had one problem. They all appeared to be set in the interregnum between the end of the alien invasion (which ends as of chapter 37 and the end of volume 7) and the introduction of King (which begins in volume 8 and chapter 38). Except for one. That included in CD2: ‘Genos, Training’. When you go to the fan wiki, you’ll read that it’s been set after Genos gets his G-4 set of upgrades, which puts it much, much later than the rest and a real break with their continuity. This is a fan’s supposition, not an authorial statement and when I sat down to review the series, it stuck out as odd.

So I looked into it, considering even whether to write to ONE to ask for clarification. And then I remembered that Nothing In OPM is Complicated; It May Be Subtle, But Never Complicated.

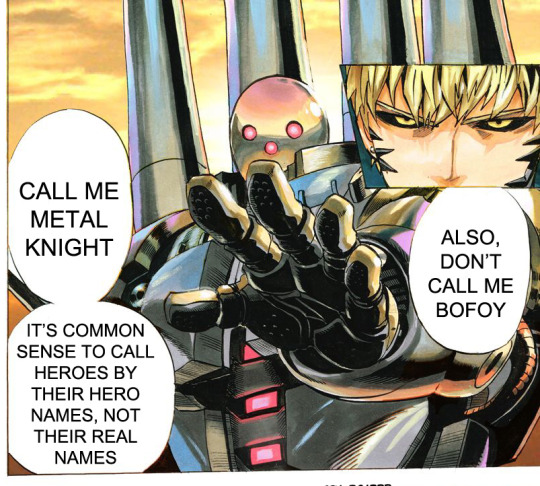

And the subtlety that is right there for the astute fan is this: the heroes Genos recruits all call him Genos. Not Demon Cyborg. Why not? Because he hasn’t yet been given one! Just as is the case in CD1, he’s still without a hero name. Heroes call each other by their hero names. We learned this all the way back in chapter 21:

If one is a keen fan, that’s all the explanation one needs to know that CD2 is set at the same time as CD1 and the rest of the Drama CD set. However, it’s worthwhile explaining further in this instance. So a few possible objections then:

Objection 1: How can you know when Genos got his G-4 upgrade and when he got his hero name?

The manga tells us precisely which upgrade is the G-4 one in black and white (outlined in red for emphasis):

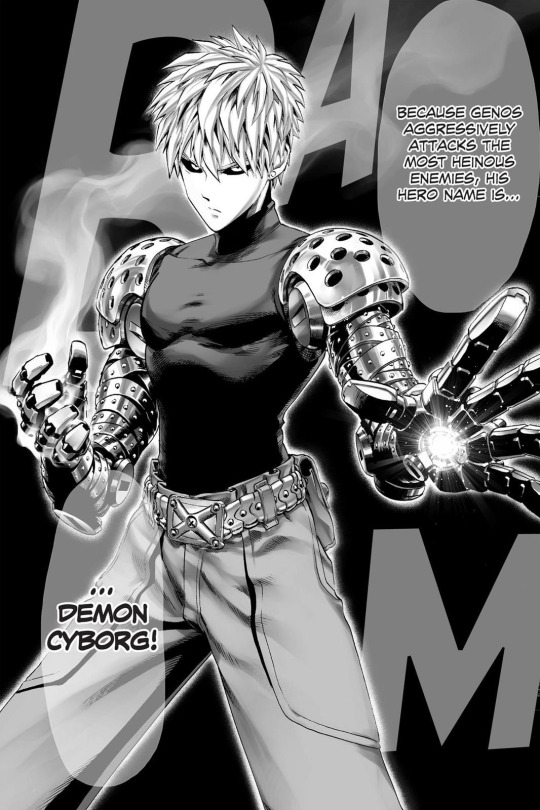

At the same time that the G-4 upgrades appear, Genos and Saitama get their hero names. Not before.

After Genos gets a hero name, only the heroes who knew him personally beforehand keep calling him Genos. Bang and Saitama will always call Genos Genos because he’ll always be that damn kid to them, King calls him Genos to his face, but calls him Demon Cyborg when talking about him to others, and Fubuki calls him both in the best possible passive-aggressive manner.

Objection 2: Right, so it’s not the G-4 one but couldn’t it be after Genos defeats the G-4 robot anyway?

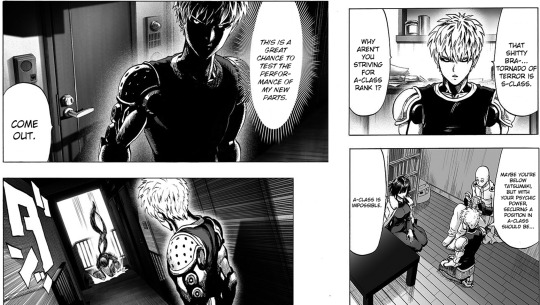

ONE has anticipated this possibility. When Sonic shows up, Genos goes out to face him precisely because it’d give him a chance to test out his interim set. Which he discarded IMMEDIATELY afterwards, going back to his spare arms literally the moment he got back inside the apartment.

He tests them out on Sonic (left) and they’re gone by the time Fubuki gets inside to tell her tale of woe (right). Because sometimes, Genos is a spoiled brat.

The set he had before G-4 is the only one he would have had long enough to do the several days of testing that Drama CD2 takes place over.

Only this set is in the right place and the right time and for the right amount of time to logically fit in the story.

Objection 3: I can’t actually tell the difference between one arm set and another.

Genos does indeed go through a lot of arm sets and it’s an easy detail to miss. Thankfully, a hyper fan has done the work for us with extremely nice schematic drawings. However, a very easy way to tell the G-4 upgrade apart from the rest is that it’s the one that looks like you could unscrew it with a coin. If you had a very large coin and a place to stand.

Schematic drawings of arm sets. Left: interim arm set used on Sonic. Right: G-4 upgrade arm set.

Objection 4: Isn’t this all rather subtle?

The clues as to when the other episodes are set are just as subtle. In all of them, King is not yet in attendance. Once Saitama meets King, the latter is with them almost all the time and he and Saitama are frequently to be found playing video games. In CD1, Saitama doesn’t have a hero name yet, so we’re happy to assign it to before King. In CD3, Sonic doesn’t recognise Genos, so we’re happy to accept that they’ve not clashed yet and put it before King. In CD4, Garou bumps into Charanko without recognition, so we’re happy to accept that he’s not yet made his declaration of war yet.

But I’m going to bet that there’s going to be an incredible amount of push-back to the idea of setting CD2 with the rest of the stories that bracket it. Push-back that wouldn’t be present if it were about a character who enjoys more fannish favour, like Metal Bat (where the response would be one of relief ‘I thought as much!’). The fanon view of Genos is that he’s extremely weak, barely a Class S hero, and it’s taken him several upgrades to be barely adequate.

Objection 5: Truthfully, I just don’t care.

I can believe that. That is indeed the truth! Well, it’s half the truth. The full truth is that faced with an ambiguity, the fannish bias against Genos became clear -- it had to be later, rather than sooner. And no one questioned it or pushed back. That’s how bias works: it’s not mindless opposition at all times, but a lean towards or against whenever you have a choice. It’s a danger inherent in fanon -- when popularly-accepted notions gain near canonical status. In universe, it’s how King works too: because he could be anything, characters project onto him their own internal character and biases.

It’s worth getting these things right. No individual fan has to care, but sites like the fandom wiki do. Editorial remarks are all too easily mistaken for authorial ones and that’s misleading.

Objection 6: What’s your problem, anyway?

I’m writing this as much because I’m annoyed with myself as with anyone else for not taking the time to look into it until I came to review the stories where how little sense the supposition actually made became clear.

It does come down to what fandom is about, doesn’t it? Fandom is as much a social activity driven by the need to cohere and to agree as it is about enjoying a work. And sometimes the truth suffers for it. It’s a salutatory reminder to myself to always, always do my own thinking, cross-check carefully and take no one’s word as gospel.

The Take Away

Anyway, what the take away is this: all four ‘Serious’ Drama episodes are set in the period between when one fit of madness -- the alien invasion -- ends, and then next fit of madness -- the monster uprising -- begins.

#OPM#reviews#Majin Drama CDs#Genos#fandom discourse#correcting stupid mistakes accepted as canon is always a pain

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWC No.28: The Future of Fandom

Editorial

TWC Editor, TWC, past and future

Theory

Paul Booth, Framing alterity: Reclaiming fandom’s marginality

David Peyron, Fandom names and collective identities in contemporary popular culture

Bonnie Ruberg, Straight-washing "Undertale": Video games and the limits of LGBTQ representation

Eric Andrew James, Using rhetorical criticism to track Twitch Plays Pokémon fans' attachment to sacrifice

Sarah Elizabeth Lerner, Fan film on the final frontier: Axanar Productions and the limits of fair use in the digital age

Praxis

Naomi Jacobs, Live streaming as participation: A case study of conflict in the digital and physical spaces of "Supernatural" conventionsSky LaRell Anderson, Extraludic narratives: Online communities and video games

Melissa A. Hofmann, Johnlock meta and authorial intent in Sherlock fandom: Affirmational or transformational?

Dorothy Lau, Donnie Yen's star persona in amateur-produced videos on YouTube

Symposium

Casey Fiesler, Owning the servers: A design fiction exploring the transformation of fandom into "our own"

Nicolle Lamerichs, The next wave in participatory culture: Mixing human and nonhuman entities in creative practices and fandom

Bridget Kies, The ex-fan's place in fan studies

Brianna Dym, Casey Fiesler, Generations, migrations, and the future of fandom's private spaces

Shannon K. Farley, Further future fandom: A conversation with middle school-age fans

Robin S. Rosenberg, Andrea M. Letamendi, Personality, behavioral, and social heterogeneity within the cosplay community

Bri Mattia, Rainbow Direction and fan-based citizenship performance

Megan Vaughan, Theater criticism, "Harry Potter and the Cursed Child," and online community

Deborah Krieger, Jewish identity, fan representation, and Yehuda Goldstein in the Potterverse

Cody T. Havard, The impact of the phenomenon of sport rivalry on fans

Review

Melanie E.S. Kohnen, "Old futures: Speculative fiction and queer possibility," by Alexis Lothian

Lorraine M. Dubuisson, "The fanfiction reader: Folk tales for the digital age," by Francesca Coppa

J. Caroline Toy, "Participatory memory: Fandom experiences across time and space," by Liza Potts et al.

Louisa Ellen Stein, Roundtable with Paul Booth, Melissa A. Click, and Suzanne Scott

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

Original Work and Original Plan - Japanese Peritext

There are several typical terms that signify authorship and other noteworthy credentials within the paratext [peritext] of Japanese produced works. Some simply have the same meaning for intent and purpose, while some have a certain nuance that creates a different understanding depending on the development of the material. Either way, it’s there to provide essential production information that tells us about the making of the text.

To cover my bases, paratext is essentially information that communicates something about a text (e.g. a book, film, or video game’s story). This information is delivered through the forms of epitext and peritext—the latter, which is information that “surrounds the text” (e.g. title, author name, publisher name, copyright, foreword/afterword, etc.). This paper will mostly be focusing on the peritext side of things. **See Paratext for Fiction and Fandom for more, on Tumblr.

Alongside the title of a product, the most noticeable form peritext takes is that of authorial information. There are two basic ways in which authorial credits are typically noted.

For one way, it’s very common that a sole author of a given work, especially for a printed book, will simply have their name placed on the front cover without any accompanying identifying credentials. It’s implied that whatever name is present is the primary author [and/or artist] of the work, and thus it would be unnecessary to include any extra identifying paratext that signifies this. It would also be fair to assume, then, that there aren’t any other significant parties involved or relevant in the conception of the work, outside of the credited publishers and other editorial roles that might be spoken for on the cover or copyright section.

However, for the second basic way, that doesn’t stop “Author: X”, “Story and Art: X”, “Book by: X”, “Whatever: X”, etc. from being a viable, albeit blunt, way to list authorial credits on a front cover. There are even situations where this specification isn’t made on the front cover (where just the author/artist name will be), but instead it might be written somewhere else inside the book for...reasons. Between the author, editors, designers, and publishers—the way the peritext is presented will vary. Still, there are pretty understood traditional ways in which this should be done in general, even if for the sake of creating a recognizable uniformity for potential consumers.

In the case of the second way, the Japanese language has its own use for authorial peritext, though interestingly enough, you’ll still see products include some English language designation for authorship at times.

For identifying the author of a work, you’ll see terms consisting of:

著 cho - work/book (by)

著者 chosha - author/writer

文 bun/fumi - text/writing (by)

漫画 manga - manga (by)

作画 sakuga - art/drawings (by)

Etc.

The first three have such a close meaning and functionality to each other in what they signify that they’re understood as interchangeable in most contexts. I also haven’t seen 文 used as often as the other two for the typical published material, but it has popped up, like for the Ultimania Guide novellas. In regards to the last two (漫画/作画) for a manga, if there is a sole author/artist, you’d often find only 漫画 (Manga by) being used. Alternatively, we still know that doing the first basic way of just listing the author/artist’s name is still applicable.

This is all very cut n’ dry in the peritext world—the conventional ways of designating authorship, and by extension originality, is apparent here.

But as you know, not every story is this simple.

Is it a manga with a different artist than the author? A novel that is based on another work or is using its setting? Or perhaps, there was a supervisor or another collaborator heavily involved? There are a number of Japanese terms specifically meant to cover the grounds of identifying those given credentials, which naturally goes beyond just the direct authorial—staff credits in an opening/ending sequence of an anime or movie will have a myriad of different designations. Sometimes, there might then be a certain obscurity for the previously understood connection between authorship and originality. If going by the peritext alone, this can wholly be due to the different types of terms being used.

For an adaptation or derivative work, having just 著 or 著者 for the actual author wouldn’t simply suffice as it would with an entirely new original work, mostly if the originality of the context isn’t applicable to the author listed. Or, consider the situation where a manga has a different author and artist. Both 漫画 or 作画 would be used to refer to the illustrator. So, surely one of the other words like 著 or 著者 would be used to identify the party responsible for the story of the manga, right?

Not exactly, and that’s where all the fun begins.

In Japanese peritext, I’ve learned that’s where two other common words come into play: Original Work (原作) and Original Plan (原案). These two have such versatile meaning to their usage in paratext that they can somewhat cause confusion in whether or not they mean the same thing.

原作 (Original Work)

原作 noun

gensaku [げんさく]

- an original work (such as the source of an adaptation or translation)

Example:

そのドラマは原作と違っている。

The drama differs from the original story.

原案 (Original Plan)

原案 noun

gen'an [げんあん]

- original plan, original bill (in a legislative body)

- draft plan, original proposal or motion

Example:

彼は原案に固執した。

He adhered to the original plan.

As it turns out, 原作 and 原案 are simple by the textbook definition, and they also have a pretty different span of definitive meaning. With that being said, they’re both often used as useful credentials for fictional works.

Whether you’re looking at a cover of a JPN manga, novel, or the opening credits of an anime, you’ll see one of these words eventually. In applicable cases, you might see them both at the same time to give the credit to the corresponding parties involved. There’s a meaning they retain specifically as paratext for a fictional work—which is where the actual confusion comes into play of whether they’re conveying the exact same thing.

Any problems distinguishing the two from one another can mostly be alleviated by understanding what functionality they typically encompass in the context of fictional material in identifying authorship.

After consulting with some of my native Japan friends and taking a careful look at different Japanese materials and marketing, I’ve discovered that this particular functionality in context mainly refers to either (or both of) these two attributes:

The 原作/原案 of the author/company for the external, original source

Function #1 is a “based on” meaning, and arguably the most common functionality the two words use.

Applied typically for direct adaptations of the same given story, 原作/原案 are meant to convey what could be understood as a formality of sorts (along with legality aspects) in designating originality, if not just that, to showcase contribution in some form.

原作 (Original Work—sometimes translated as “Story by” or “Based on Story by”), close to its textbook definition, refers to the original source that the given adaptation or related work is based on.

原案 (Original Plan—often translated as Original Concept), which refers specifically to the original idea, proposal, concepts, setting, story drafts, etc. behind the origin source work the adaptation or related work is based on.

*Keep in mind that when these two are used as paratext, they’ll typically list the appropriate original creator/company of the origin work/plan, NOT the actual title of the work. There are the rare cases, however, where the actual title of the origin work will be used instead of the creator/company name. Also, while those translations are what the official ENG localizations will often do, the JPN will retain their actual terms (Original Work/Original Plan) when providing the ENG wording on JPN versions of their products.

Anywho, you might find 原作 used more than that of 原案 because of its defining “based on” traits. Still, both of these can be used even for a work that is telling its own story in any capacity (whether the story is abiding by a specific continuity or not), or for a work that may be its own series altogether, but still associated with an original source. Whether there is actual involvement from those credited or not is up to investigation, but there are a lot of cases where involvement by either (or both of) the creator/company is clearly understood by other production credentials.

In Function #1 when a work has the 原作/原案 paratext identifiers, this is to accompany that of who is designated as the primary author and/or artist—the one who is responsible for the actual storytelling composition of the material. The most common example would be if a company hired an external author to write a novel adaptation for their anime or game series, instead of having the original creator/writer do it. They would be the author, while the creator/company is credited with 原作/原案.

Examples:

Death Mark (死印) novel—Spirit Hunter series

{Japanese}

著: 雨宮 ひとみ

原作: エクスペリエンス

{English}

Work by: Hitomi Amamiya

Original Work: Experience

Fate/Zero manga series

{Japanese}

漫画: 真じろう

原作: 虚淵玄(ニトロプラス)/TYPE-MOON

{English}

Manga by: Shinjiro

Original Work: Gen Urobuchi (Nitroplus)/TYPE-MOON

PERSONA -trinity soul- anime

{Japanese}

原案: プレイステーション2用ソフト『ペルソナ3』(アトラス)

シリーズ構成: むとうやすゆき

{English}

Original Plan: PlayStation 2 Software “Persona 3” (Atlus)

Series Composition: Yasayuki Mutō

Kingdom Hearts novel series

{Japanese}

著者: 金巻ともこ

原案: 野村哲也

イラスト: 天野シロ

{English}

Author: Tomoco Kanemaki

Original Plan: Tetsuya Nomura

Illustration: Shiro Amano

2. The 原作/原案 of the author/company for the internal, present source

Function #2 is relative to the production of the present material specifically, treating it as if it’s the origin source.

While the “based on” mentality can be understood as possibly only a formality for designating originality, this function implies that those cited were much more hands on in the conception of that given work through the usage of 原作/原案.

原作 (Original Work—often translated as just “Story (by)” in this context) is more equivalent to the meaning of being the author for the given material, as opposed to that of an external original source—pretty much how “author” would function normally. If to understand it in tandem of the word itself, “this is an original work by X” is the mindset to have.

原案 (Original Plan—still translated “Original Concept”, usually) is dedicating the story contents much more to that of the given material, as opposed to completely referring to the contents of another external original source. To note, 原案 would still be credited towards the origin creator/company of said story content, while accompanying another writer(s).

In most cases, Function #2 is understood naturally if the present material isn’t simply functioning as an adaptation of the same story, but is acting as an original source itself as it applies to the given series—this could be the case regardless if it’s a preexisting series or not. In the case of an origin manga series that always had a different author to the artist, 原作 (Original Work) will most often, if not always, be used to refer to the author, while either 漫画 (Manga by)/作画 (Art by) will be used to describe the artist. I’m sure there exists some situations where 原案 would be used instead of 原作 for original manga, but I haven’t come across that yet myself.

In addition, Function #2 would also be the case of supplemental material that acts as a part of the given series as an additional story, but it may have the circumstance of involving other parties other than the original writers/artists to where 原作/原案 is needed to cite them. This is similar to what was described in Function #1, but this supplemental material doesn’t simply have to be an adaptation of a previously told story.

Examples:

Final Fantasy XV -The Dawn of the Future-

{Japanese}

著者: 映島 巡

原案: 『FINAL FANTASY XV』開発チーム

{English}

Author: Jun Eishima

Original Plan: “Final Fantasy XV” Development Team

The Promised Neverland

{Japanese}

原作: 白井カイウ

作画: 出水ぽすか

{English}

Story: Kaiu Shirai

Art by: Posuka Demizu

High School Fleet anime

{Japanese}

原案: 鈴木貴昭

原作: AIS

シリーズ構成・脚本: 吉田玲子

{English}

Original Plan: Takaaki Suzuki

Original Work: AIS

Series Composition/Script: Reiko Yoshida

One Punch Man

{Japanese}

原作: ONE

漫画: 村田雄介

{English}

Story: ONE

Manga by: Yusuke Murata

**********************************************************************

While ultimately having different meanings, 原作 (Original Work) and 原案 (Original Plan) can function similarly as paratext in indicating authorship—the difference lays where the former represents the general origin source/series ("work/原作") and the latter represents the origin idea/concept ("plan/原案") of the credited author/company. This is understood even when both 原作/原案 are used at the same time for the different people who fulfill those representations. This is seen in the High School Fleet example, and it’s actually applicable towards the Fate/Zero anime series as well where both are also used.

In addition, there is an understanding that both functions can be at play simultaneously—most specifically if Function #1 is primarily understood, but aspects of Function #2 had occurred in development, going beyond the sake of “based on” formality alone. This depends on the amount of involvement the credited representatives have in the conception of the materials that are based on their work. While it’s definitely applicable for completely new works, this can even happen for an adaptation where the amount of involvement can correlate to either meaning of 原作/原案 in either functionality.

But, as you’ve probably been thinking, the paratext of either function looks pretty similar, if not downright identical to one another (especially the novel or manga examples).

Additionally, how can you tell which function 原作/原案 is being communicated when simply looking at the paratext alone? Especially in the case of a manga—is the 原作 on a manga significant of it being an adaptation, or of just signifying the author of the manga?

If just by sight, you reliably can’t in most circumstances—cue the fun of research!

When determining what functionality is happening or is best applicable, investigation and/or having prior knowledge of the material is imperative in not only ultimately understanding which functionalities are at play, but also for understanding the level of involvement that those credited have within the project. In other words, what needs to be discerned is how much weight 原作/原案 carry. In a lot of cases, this is actually rather easy.

Finding out whether the work is an adaptation or a new, supplemental work is the best start—identifying who exactly the credited parties are, the purpose of the material and what storytelling it is covering, and even investigating other paratext [epitext—interviews, advertisements, referential materials, etc.] from proper authorities that speak on the material/production itself can help find the truth, or at the least, the most applicable truth.

These two words are indeed different and can’t be used interchangeably, but they can function similarly. They’re not as straightforward as accompanying credentials like 監修 (Supervision) or 協力 (Cooperation/Collaboration) alone, which you'll also see often as identifying paratext and even those are still open to investigation to determine involvement. However, 原作/原案 are very versatile words that hold a significance in authorship, so much to where 監修/協力 can be implied for those under 原作/原案 when applicable and vice versa.

漫画 (Manga) and 作画 (Art/drawings) are almost similar to that of 原作/原案, in that they are pretty similar in comparison, but their difference is much easier to understand in how they’re used for manga. They are pretty interchangeable only in the situation where there is another author to credit, otherwise, 漫画 (Manga) by itself would be the only word expected to refer to both the author/artist for manga. Because of this, 漫画 (Manga) carries a certain nuance that, even with another author in charge of the story, it has a chance of implying that the artist still weighs in their own storytelling ideas as well. This could be understood even for 作画, but I’ve been told 漫画 is the heavier of the two with this implication. It’s also something that, for the practical sake of making a manga, makes sense—the artist weighing in on how the story is told as a manga is appropriate. If it’s just the more “Based On” meaning, however, then this might even be more true depending on if the original author is involved or not.

Anyway, a big question probably asked at the very beginning of this whole thing: why is this important?

Other than understanding the differences, its importance is the same reason why identifying who the author or publisher of a work is important. Really, it’s why any paratext is important for that matter, whether purely for the formal or legality aspects associated with publishing.

Most, if not all, paratext exists to be informative with a purpose. 原作/原案 signifies the presence of originality from the accredited persons. With further investigation of the nature and purpose of the material, it also acts as a clear sign of involvement within the present work, and 原作/原案 is there to cover that ground as well. What then is understood initially for the sake of formality becomes more telling about the production process—this works in tandem with all other significant paratext. Without it, the present work is more likely to be taken fully as an original work of the only listed author, whether the prior knowledge of it being based on, or associated with, a preexisting work or not is at play.

It’s just as natural as seeing any work that simply lists an author’s name alone—this signifies prominent originality to that author specifically for that work. A work that doesn’t have either 原作/原案 listed when it should thus is very likely significant of informing the audience that the product is an original work or interpretation. A work should have 原作/原案 when it’s applicable, but sometimes it isn’t listed in those, perhaps, deliberate cases. I have strong reasons to believe that the lack is for the emphasis of originality to the listed author, but this also doesn’t mean 原作/原案 still isn’t understood on a technical level when applicable.

If you’re an external author writing for a preexisting series, you’re typically going to want that paratext (along with the marketing value that comes with it), just as much as you’d want to work with the official authorities and authors at hand on said project. The original parties themselves would want this too for their own record of originality designation. Whatever adds to the accredited authenticity of the work and authorship is highly valuable for those involved. A reason they wouldn’t could be because of designations of originality to that author, which isn’t bad, but it also isn’t bad to just include that paratext.

This doesn’t take away from those credited as the actual authors—this especially in the examples where the external writer/artist is hired to write for a preexisting series by the proper authorities. The expectation is of the creative endeavors of the author and their writing/drawing capabilities as it would even if it was their original work. It’s as much their product as it is who is credited for either 原作/原案.

And (as you’ve probably been waiting for it), this doesn’t directly speak on canonicity.

When exploring paratext for the sake of canonicity, this will be an important piece of knowledge to take in when observing the Three A’s of Authenticity (authority, authorship, and application). Since these are very common pieces of paratext for Japanese based material, it would be a good idea to get in the habit of recognizing their functionality and impact on the given material.

***See Concept of Canon in Fiction on Tumblr or Google Doc.

However, the mention of 原作/原案 is all about what is being communicated through paratext about originality—it isn’t always going to provide the end all answer to the designated author’s authenticity to the canon or the levels of interpretation/creativity they may or may not put into the work. Originality, not authenticity. However, it can certainly affect the understanding depending on how much information is available that the use of 原作/原案 can supplement, especially if attributes from Function #2 are involved.

But there is a “food for thought” kind of idea: the more originality that is placed on an external source, the more the validation of authenticity is needed if it hasn’t been already.

If there is a strong emphasis of originality for a work written by an author who doesn’t have any information regarding their authenticity, then that is a telling component that researchers can use to address the work’s canonical standing. But, if this originality is accompanied by the direct involvement from the authentic parties, then we’re getting somewhere at the least in evaluating canonicity.

Either way, it’s mostly about the observance of originality initially.

That’s it for the main post, but since Tumblr’s formatting is kind of wonky, I’m just going to leave the extended examples of 原作 and 原案 uses in the Google Doc in the “Paratext Examples” section. There’ll be some extra things like extending commentary on certain examples, other words commonly used with 原案, and something on the use of Supervision (監修) as well that correlates with OG Work/Plan. Everything is much more neatly organized on there already, which is always better than trying to format things on Tumblr. lol

See you soon.

#square enix#final fantasy#final fantasy vii#nier automata#kingdom hearts#final fantasy xiii#persona 5#final fantasy xv#fate/stay night#manga#anime#video games#analysis#paratext#japanese

0 notes

Text

Before We Go [A Crisis on Earth X Fix-Fic]

Summary | Foreword:

In 2017, Barry Allen and Iris West attempted to get married to far too many interruptions. One of those interruptions was controversial, loved by some and despised by others, apparently including at least one of the lead writers for the show which chronicles the lives of Barry Allen and Iris West(-Allen). In order for Felicity Smoak and Oliver Queen to marry at last, also after too many attempts, an executive decision was made that the former's quirkiness and tendency to put her foot in her mouth be turned up to 11 and in full effect. This hurt fans, Iris West, and, in this author's opinion, some credibility among those called the Powers That Be. This documents an exactly 37% canon divergence which attempts to reconcile some irreconcilable discomfort in the fandom. It is for fans of both couples. It is for fans of canon-only-with-couples-tacked-on. It is for multishippers. It is also for those who, as in the immortal words of the 2004 film Mean Girls, wish we could all get along like we used to in middle school and bake a (wedding) cake filled with rainbows and smiles and that everyone would eat it and be happy.

On AO3.

Tags on AO3: Episode Novelization Excerpt, Fix-It, Marriage, Weddings, Episode Fix-it, Episode Tag, Alternate Universe - Canon Divergence, Canon Dialogue, Fix-It Dialogue, Consent, Explicit Consent, Meta

Ships: WestAllen and Olicity

Resources: This is the original scene, which I used, transcribed, and altered: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wQuddq7zt0

This is someone's sound extract of the background/music track of the scene so you can, if you wish, read this fic with it in the background to see if it works for you: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm6qnvV3egE And a listenonrepeat link of the same: https://listenonrepeat.com/?v=rm6qnvV3egE#Crisis_on_Earth_X_Soundtrack%3A_Double_Wedding_(LOT_3x08)

I hope you enjoy my little project. It's much too meta and whatever, but I did it for me and hope it does something for you.

Long author’s note, then fic below the read-more or on AO3 linked above.

Note 1: This is an honest attempt to offer a possible solution to some really unfortunate writing in a scene that I want to like and mostly-do but which I know causes a lot of discomfort for a lot of people. If you hate one pairing or the other or have come here to see Olicity (or WestAllen) called out or pedestalized beyond their station, this fic is not for you. This fic is for those who almost like the way things are but would like for there to have been a bit more tact. This fic is a peace offering. This fic is something I wrote to give myself catharsis and a writing challenge on a Saturday afternoon because I felt that I owed it to people.

Disclaimer A/A personal statement: I am not in the Olicity Fandom. I am not in the WestAllen Fandom. I am in the DCTV fandom. If I ever was in one of these capital-F fandoms, I would have come closer to being in the WestAllen Fandom, back during S1, but I only just recently got back into the DCTV universe. I'm happy, and I hate seeing so many people unhappy and feeling put off. This is meant to be something good that, if it fosters anything, will foster good-will. Because of that, hateful or heavily-biased in a negative way comments will be ignored/deleted/their posters blocked depending on the place where they are posted. If you want to engage in thoughtful, articulate meta discussion that is critical of my take on this, feel free to message me separately or elsewhere, but in this particular thread/place/time I am not going to let that be the most-vocal takeaway from it, and I hope you will respect the spirit with which it is written and my authorial wishes. Thanks!

Disclaimer B: It goes without saying on all my fics, but this fic has a lot of canon dialogue in it, and I mostly tried to avoid excessive editorializing on the things I was just literally going through a clip and transcribing. This fic is mostly from an almost-objective third person POV as a result, because I'm trying to be as respectful to the source material as I think it deserves while "fixing" it to my better-liking.

Note 2: I did do my level best to give Iris the space to feel something about her day not going at all according to plan. I also tried to make it so Felicity could actually confirm some kind of peace with this. I let her ramble, and I tried to make her apologetic enough, but I'm not about to put her on the chopping block after what she went through as a Jewish woman facing a horde of alternate-Earth Nazis including a terrible, nightmare version of her now-husband. I am all about lady positivity, and I hate that strange (and arguably really bad for a moment there) writing threatens them remaining friends, and that was a big part of my motivation too.

“Well, if you want it to be personal, I think we know a guy who's ordained,” Felicity said, looking up for Oliver and some expression of recognition. He gave her one and swallowed an unspoken word.

In the space of less than a second, Barry thought it over and agreed. He was in Star City and back again in the space of a breath or two, hardly a wrinkle in his or in John Diggle's clothes.

John took stock of his surroundings and tried to steady his irregular breathing. He smiled a brave smile and lifted his hand in an already placating gesture. He thought he had this.

“It's a good thing I didn't vomit, right?” he asked, looking into Barry and Iris's faces. The former looked skeptical, on the verge of a wince, while the latter looked equal parts surprised, glowing, happy. He really didn't want to do this, but the moment he thought he had it, he managed to turn away and retch onto the ground. He could feel the collective discomfort and sensed his friends' efforts to close their eyes, to turn away.

“Are you okay?” Felicity asked in a strained, dutiful tone that was a little louder than necessary from the force behind it.

John scrubbed his hands over his face and tried to recover his center – both his dignity and his equilibrium. He turned to Barry and pointed at him, giving a mild order but not before he pressed a loose fist to his mouth and made absolutely certain that nothing else but words wanted to come up.

“A little warning, next time?”

“Sorry,” Barry said, a little contrite and flat. Iris gave him a look of blended sympathy and disgust.

“What's up?” John managed to ask, glancing between all four of his friends.

“You got ordained to marry your brother and Carly, right?” Felicity asked, still tucked tightly against Oliver's side.

“Yeah,” John rasped out.

“We were... hoping that you could give us the same treatment,” Iris interjected, a little strain in her lips and mouth as if she were nervous to ask or to have it answered.

John looked at Iris, then at Barry, and Iris again. He hadn't had much time to process, but he quickly got up to speed.

“Wow, really? I'm honored,” he replied.

“Yeah?” Barry asked.

“I am,” John insisted.

Iris smiled without any attempt to hide it while Barry glanced away, a little bashful and a little smug at once, pressing his lips together as they tried to form a smile, too. He stopped fighting it when his eyes got to Iris. His hand moved along her shoulder and he met her eyes. They shared a kind of silent agreement and confirmation.

“Alright, well let's... do it,” Barry said.

“Okay, that's great,” John said, sincerely before launching into a very quick logistical assessment. “Uhm...” he said, turning to Oliver and Felicity, “I guess that makes you the best man,” he decided, pointing and Oliver before shifting the gesture to Felicity with a nod, “you the maid-of-honor.”

Felicity gave an audible, excited gasp. At the same time, Oliver gently started to lower his hand from Felicity's back and to square his posture.

“Honored is correct,” Oliver said with a little lowering of his head.

Felicity's hand rested over her heart for a moment. Then, she brought both hands together and bowed to Iris a little before laughing with her and bounding to her with open arms.

Meanwhile, John gestured to bring both his arms to cross briefly in front of him.

“Alright, let's get into position,” he said. “You're here,” he told Barry, then he pointed to each respective position for Oliver, Felicity, and Iris, “and there and there.”

Barry looked at Iris across from himself and added, dryly: “Oh, I see.”

Iris laughed at her husband-to-be, visibly overjoyed.

“You guys write vows or you just want the boilerplate?” John asked.

“Oh!” Iris exclaimed softly, reaching into her pocket to retrieve the little slip of paper that had already been through so much. “Yes, I, um, wrote mine,” she said as she unfolded them.

“Um, I tried to write mine, uhm...” Barry said, glancing at Oliver for remembered commiseration's sake before snapping his attention back to Iris, “but then I realized that I didn't need to.”

Iris gave him a little look of concern, but there was no fear there at all.

“Uhm,” Barry said again, gathering his nerve and thoughts together, “my entire life has been marked by two things. The first one is change. From when I was a kid to when I was an adult, things were always changing, but no matter how different things became or what new challenges I had to face, I always had the other thing that my life was marked by. And that's you. You've always been there. As a friend, as a partner, as the love of my life. You're my home, Iris. And that's one thing that will never change.”

Iris smiled and pressed her lips together, emotion lifting her to the tips of her toes as she seemed to hold back happy tears, lowering herself back down flat onto her feet.

“That was really nice,” she said with composure and then a soft laugh. She was grinning at him.

Beyond them, Felicity glanced from Iris up to Oliver. He glanced up at her from attentive listening, but by the time he had, she had already returned her gaze to Iris.

“Uhm,” Iris prefaced her vows, gathering her voice and mirroring Barry, “when I was nine years old, I wanted to be a ballerina, remember?” she asked, pausing for Barry to nod while he watched her eyes. “And though I was not a very good dancer,” Iris said, momentarily turning to look at Felicity and Oliver to draw them into the wry truth of it. She licked her lips before she continued speaking. “And the day of the recital, I froze.” She shook her head a little. “I couldn't move,” she said, looking into Barry's face. “And I wanted to die,” she said, aside in Felicity's direction for just a second. She anchored her gaze on Barry. “And then, I looked in the audience, and I saw you. And you got up and you climbed onto stage and you did that whole routine with me,” she said, smiling and shaking her head at once. “And we killed it!” she insisted, drawing soft laughter from everyone around her. “I mean, we brought the house down.” She glanced down briefly. “And from that moment I knew that with you by my side, anything was possible. The Flash may be the city's hero, but you, Barry Allen, you're my hero. And I am... happy,” she announced, pausing with another soft bounce to her tiptoes as she restrained her urge to cry, “excited, and honored to be your wife.”

John paused for a moment to let Iris's words hold their own weight.

“Wonderful,” he added after a few, reverent seconds. “Well, then I pronounce you both – Bartholomew Henry Allen,” he said, carefully making sure not to fumble his unfamiliar, full name. Barry hummed an affirmation that he had gotten it right as he continued, “and Iris Ann West – husband and wife. Barry – please – kiss your bride.”

There, in that park, before the water, three of their friends, and an inopportune puddle of sick that made neither of them want this any less, Barry Allen took her hands and drew her in. He kissed Iris West-Allen – officially – for the first time.

Iris squeezed Barry's hands and tiptoed to lean into the kiss which she returned wholeheartedly, finally married after another, different kind of near-end-of-the-world which might have been more jarring than some of the rest. He was still here; she was still here; and he was still her hero.

When they broke apart, both smiling until it might have ached for them or in the chests of anyone watching, John lifted his hands in another gesture to conclude the ceremony and break into less formal congratulations and proceedings. John opened his mouth, but the sound never made it out because of a sudden, startling interjection.

“Wait,” Felicity interjected, desperately. “Wait, wait,” she pleaded. “Just one second. Um, if you guys don't mind,” she said, quickly indicating Barry and Iris.

Iris squeezed Barry's hand she still held tighter, startled but turning to Felicity, too.

“Or, I mean, if you don't mind,” Felicity said, gesturing and leaning toward Oliver just a little. “Really, if you don't mind,” she said, in a blanket way.

Iris glanced from Felicity's face up at Oliver's for a second, following whatever was happening and quickly seeing the shape of it.

“But, before we go, would you marry us, too?” Felicity asked John, wheeling her gaze back around to Oliver almost frenetically. Then, almost as an afterthought, she looked at Oliver. “Will you marry me?”

“I thought... I mean, I thought you didn't believe in marriage,” Oliver said in an even tone, neither hoping nor drawing back from it.

“No,” Felicity agreed mildly, “but I believe in you,” she said, hands pressed tightly together in low, restrained supplication. “And I believe that no matter what life throws at us, our love can conquer it, married or unmarried. I love you. My greatest fear – my greatest fear in life is losing you—”

“Yes,” Oliver said, without hesitation when he decided to speak.

“Okay,” Felicity accepted quickly.

“Yeah?” Felicity asked at the same time Oliver smiled and simply said: “Yeah.”

“I do,” Oliver said as he reached for her hand. And again: “I do,” when he took it.

Barry grinned tightly, perhaps proud that his earlier advice and faith had finally paid off. That he had been right, even in the face of an all-knowing mentor who had known, in a very dark hour and before, that he would never have the same kind of happiness, strength, and security that Barry could feel settling over his shoulders, tearing away other weight with it.

Iris's face went through several emotions. First, she was confused and a little anxious. Her wedding had been interrupted once, but now it was done and all that remained was to walk away a married woman. She watched Felicity, perplexed as she often was with her, but then she saw Oliver's reaction and couldn't help smiling at him. Once upon a time, he had been a handsome stranger that Barry had inexplicably known. Now, he was a man that looked very anxious and relieved at once to finally be with the woman he loved. And today, after everything, it made her smile at him, too.

“Uh, John... what do you... what do you say?” Oliver asked, no longer the picture of decisive and calm leader that he had needed to be for so many hours now.

“Wait—” Felicity said, holding up her finger to indicate her need of another moment.

Oliver frowned, possibly terrified, but he looked back down at her.

“Wait, it's okay, I promise, but,” she said quickly. Then she looked at Iris, taking her free hand and reaching up for her arm, below her shoulder. “There's a certain order this usually goes in. And I never really paid attention, because I was never the kind of girl who fantasized about this happening to me. But... I know this is sudden, and I know... none of this went how anyone planned, but... Iris, will you be my maid-of-honor, too?”

Iris watched Felicity and squinted. It was all so-fast, and with her husband she knew fast.

“I—” she started to say, but she hesitated.

Felicity looked more and more like a deer caught in headlights.

“I just... really wanted this to be okay. All of this,” Felicity explained. “And the world being invaded by Nazis – more than it already is – was too-much for everyone. I just know that... I've spent all this time now... waiting and hoping that it wasn't too late for me to undo what I did. Hoping that the last thing I said to the man I love wasn't to break his heart because of stupid, selfish fear. And you helped me see that. I... I would be honored if you would witness my wedding, just as I was honored to witness yours.” She reached up and hesitated, glancing at Barry as if for permission. Then, without waiting much, she just barely thumbed against the apple of Iris's cheek for a split second. “Like your dad said... at that beautiful rehearsal dinner where I... also lacked the necessary volume control for... anything—” she added, with a guilty glance toward but not quite to Oliver, “your love is... inspirational. In a way mine might not be, but—”

“Felicity,” Iris interjected. She was almost convinced about halfway into Felicity's talking, but seeing her nerves and hearing her reasons and just wanting her to breathe, she settled herself in her conviction. Like Barry had said, everything in life changed – even the best of plans – and if this changed for them, maybe it would be for the better. That was what marriage was. It was something to fight for, and it was a promise of hope. “Yes. Yes, I'll be your maid-of-honor.” She grinned, more than she expected to. She took Felicity's hand and tugged her closer before almost as quickly letting go.

“Thank you,” Felicity breathed so earnestly that it sounded almost like her knees might buckle.

Oliver looked at Barry with only slightly inclined eyebrows.

Barry lifted his free hand, not yet thinking of letting go of Iris.

“Hey, it was my advice that put us here, wasn't it?” he responded to Oliver's look.

“Something like that,” Oliver agreed, a little wryly and with a returning smile that gained a little confidence.

“Now,” Felicity said after a moment. She swung her hand in Oliver's a little to draw his attention and nodded back to John. “Better,” she said.

“... So what do you say?” Oliver supplied, now that it was time, according to Felicity.

Arms folded across his chest, Diggle exhaled and was ready with his reply.

“Are you kidding me, Oliver? I'm the guy for the past six years that's been trying to keep you two together.

“It's true,” Oliver murmured toward Felicity, smile no longer fading at the first opportunity.

“It's only fitting that I marry you,” John said over some collective, nervous, knowing, and joyful laughter. “Okay,” he said with an instant of bowing his head, arms still crossed. “Vows?” he asked two of his oldest, best friends without clear expectation.

Oliver looked down into Felicity's face.

“No,” he said, without regret.

“No,” Felicity agreed, warm and steady.

“And we can't do better than them,” Oliver said decisively.

“Definitely not,” Felicity said. “We kind of did those fake vows when we had that fake wedding with that psychopath-serial-killer-archer-lady.”

“I remember saying something along the lines of... you're the very best part of me,” Oliver said, it becoming obvious that the memory or the thought hadn't been forgotten or dimmed at all.

Felicity smiled tightly, her lower lip lifting a little with suppressed emotion.

“Felicity, I'm a better human being just because I've loved you.”

Felicity lost her ability to repress her smile and grinned until her mouth opened in a sound that mimicked a quiet sob but which was its perfect, warm opposite.

“Well,” John said, “since we don't have any rings just yet,” he said, lacing his hands together, perhaps remembering that he hadn't recalled to ask if Barry and Iris had carried them through all of this, doubtful as it was. “I'll skip right to the part where I say this: Oliver Jonas Queen, Felicity Megan Smoak, I now pronounce you husband and wife.” He paused for a long, long moment until he got Felicity and then Oliver to glance at him with sharp, nervous curiosity. “Oliver,” he said, “kiss your bride,” he said with a satisfied, accomplished smile.

Felicity leaned in and Oliver reached to cup her jaw on either side. He held her while they kissed, fear of losing each other again forgotten for a little while. They had won again; they had lived and found their way back to each other. And if they kissed long enough for Iris to grow impatient and pull her husband down into another kiss, it wasn't long enough until, at last, for John's sake, it was.

#crisis on earth x fic#dctv fic#westallen#olicity#dctv#this is tagged for both because it is positive toward both#if you don't like one or the other just kindly go on and realize this post isn't for you thanks#mine#myfic#tumblr fic#ao3 fic#Iris West#Iris West Allen#Barry Allen#Felicity Smoak#Oliver Queen#John Diggle

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWC No. 25 is published

Table of Content

Editorial

Editor, Copyright and Open Access

Theory

Catherine Coker, The margins of print? Fan fiction as book history

E. J. Nielsen, Christine de Pizan's The Book of the City of Ladies as reclamatory fan work

Lesley Autumn Willard, From co-optation to commission: A diachronic perspective on the development of fannish literacy through Teen Wolf's Tumblr promotional campaigns

Shannon Howard, Surrendering authorial agency and practicing transindividualism in Tumblr's role-play communities

Milena Popova, "When the RP gets in the way of the F": Star Image and intertextuality in real person(a) fiction

Dan Vena, Rereading Superman as a trans f/man

Praxis

Lauren B. Collister, Transformative (h)activism: Breast cancer awareness and the World of Warcraft Running of the Gnomes

Ludi Price and Lyn Robinson, Fan fiction in the library

Rachel Elizabeth Linn, Bodies in horrifying hurt/comfort fan fiction: Paying the toll

Victoria Godwin, Theme park as interface to the wizarding (story) world of Harry Potter

Sophie Gwendolyn Einwächter amd Felix M. Simon, How digital remix and fan culture helped the Lego comeback

Seth M. Walker, Subversive drinking: Remixing copyright with free beer

Symposium

Kevin D. Ball, Fan labor, speculative fiction, and video game lore in the Bloodborne community

Babak Zarin, "Can I take your picture?"—Privacy in cosplay

Kelli Marshall, Milk and mythology in Singin' in the Rain

Liza Potts, A case of Sherlockian identity: Irregulars, feminists, and millennials

Review

Bethan Jones, Post-object fandom: Television, identity and self-narrative, by Rebecca Williams

Amanda D. Odom, Role playing materials, by Rafael Bienia

Kathryn Hemmann, Anime fan communities: Transcultural flows and frictions, by Sandra Annett

Sandra Annett, Boys love manga and beyond: History, culture, and community in Japan, edited by Mark McLelland et al.

Transformative Works and Cultures (TWC), ISSN 1941-2258, is an online-only Gold Open Access publication of the nonprofit Organization for Transformative Works. TWC is a member of DOAJ. Contact the Editor with questions.

137 notes

·

View notes