#Jokha Alharthi

Text

“ Ahmad aveva la febbre. Strofinare preparati a base di erbe sul suo corpo in fiamme non sortiva alcun effetto. A quel punto, Salima era andata a chiedere aiuto a suo zio Shaykh Sa‘id. Era invecchiato, certo, ma non abbastanza da lasciare che il suo cuore si sciogliesse davanti alle suppliche della nipote. Lo aveva implorato, gli aveva ricordato che era la figlia di suo fratello Shaykh Mas‘ud, l’aveva pregato di avere compassione, di dimostrare la sua fede, la sua signorilità, la sua generosità, magnanimità e saggezza. Si era appellata a tutto quello cui si può appellare una madre con il figlio dilaniato dalla febbre.

Ma la risposta dello shaykh non era cambiata: “La Range Rover non lascerà mai ‘Awafi senza di me.”

Il giorno dopo, la febbre di Ahmad era aumentata, il bambino aveva cominciato a delirare. Salima era tornata dallo zio accompagnata dal marito. ‘Azzan si era trattenuto a lungo con il vecchio, gli aveva spiegato che suo figlio peggiorava e che l’unico ad avere una macchina con cui portarlo all’ospedale al-Sa‘ada di Maskade era lui, Shaykh Sa‘id. Se ci fossero andati a dorso d’asino, ci avrebbero messo quattro o cinque giorni e non sarebbero riusciti a salvare il bambino. Gli disse che avrebbe pagato qualsiasi cifra gli avesse chiesto, compreso il salario dell’autista.

“Non ho altro da dire,” aveva replicato Shaykh Sa‘id. “La Range Rover non esce da ‘Awafi. Tuo figlio guarirà anche senza dottori. Che sarà mai, tutti i bambini hanno la febbre e poi guariscono.”

‘Azzan e Salima erano usciti da casa dello shaykh cercando di non guardare il fuoristrada verde parcheggiato vicino al portone. Quando Shaykh Sa‘id l’aveva comprato, due anni prima, e l’autista l’aveva portato in paese, erano tutti usciti in strada per vederlo. Persino l’anziana madre dello shaykh si era avventurata fuori facendosi sostenere dalle sue schiave ma poi, quando aveva sentito il rombo del motore e visto le ruote nere che giravano velocissime, si era spaventata e gli aveva tirato una pietra urlando ai quattro venti che quella era opera del diavolo. La pietra aveva rotto un finestrino e Shaykh Sa‘id aveva ordinato alle schiave di riportare dentro la madre minacciando di frustarle sotto il sole se solo l’avessero fatta uscire di nuovo. Da quel giorno la Range Rover si era mossa solo quando lo shaykh sedeva al posto del passeggero. E se con lui c’era una delle sue mogli, i finestrini venivano oscurati con delle lenzuola.

Salima aveva pianto per tutta la strada fino a casa e, da quel momento, ‘Azzan aveva nutrito un unico sogno: possedere una macchina. Aveva giurato che avrebbe chiesto al Sultano il permesso di comprarne una, esattamente come aveva fatto Shaykh Sa‘id, e poco importava se avesse dovuto vendere i campi ereditati dal padre.

Ma Ahmad non aveva aspettato che ‘Azzan mantenesse fede al suo giuramento, la febbre era stata più veloce e lo aveva ucciso.

Gli avevano tolto vestiti e amuleti e predisposto la rituale pedana di rami di palma in mezzo al cortile. I vicini avevano portato secchi d’acqua dal canale per lavarlo, l’avevano cosparso di incenso e di olio di oud, lo avevano avvolto in un sudario candido e avevano portato il feretro al cimitero a ovest del paese.

Il giudice Yusuf aveva detto ad ‘Azzan: “Tuo figlio adesso è in paradiso, e quando verrà la tua ora ti porterà dell’acqua fresca per spegnere la tua sete.” ‘Azzan era stato zitto, non aveva detto che lui aveva sperato che suo figlio l’acqua gliela portasse lì, sulla terra, negli anni della sua vecchiaia. Si era mostrato fermo e paziente come si conviene e aveva stretto la mano di chi gli porgeva le condoglianze. Le aveva strette tutte, persino quella di Shaykh Sa‘id. “

Jokha Alharthi, Corpi celesti, traduzione dall'arabo di Giacomo Longhi, Bompiani (collana Narratori Stranieri), 2022¹; pp. 122-124.

[Edizione originale: سيدات القمر (Sayyidat el-Qamar; Le signore della luna), editore Dār al-Ādāb, Beirut, Libano, 2010]

#Jokha Alharthi#Corpi celesti#letture#leggere#libri#Oman#letteratura araba contemporanea#malattia#bambini#superbia#citazioni letterarie#Mascate#crudeltà#egoismo#prepotenza#società tradizionaliste#autoritarismo#genitorialità#automobili#società autoritarie#sopraffazione#avidità#narrativa#schiavi#penisola araba#paternalismo#sottomissione#diritti umani#pietà#schiavismo

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi, translated by Marilyn Booth, is a twisty book telling the story of a generation of sisters and the people who surround them in the village of al-Awafi, Oman.

Mayya marries first—struggling with an anxiety that tries to overwhelm her, finding solace in sleep—she marries Abdallah, a man who is hopelessly in love with her, and who wishes she loved him more. Asma is literary, learned, and wants to be taken more seriously. Khawla has been engaged for years to a boy who moved to Canada, and now she refuses to consider marriage to anyone but him. A web of stories explodes around the three girls. Abdallah’s tortured family history is a particular highlight.

I recommend keeping notes on the family tree at the front of the book. I wish I was kidding, but I’m not—this one is a twisty one, even for me, and it was a little necessary to do it to keep everyone straight. Once I had those notes though, it was an immensely rewarding book. Class, misogyny, heartbreak, slavery, adultery, these issues fracture and braid these people together, making and breaking marriages. It’s all worth it by the time the web of stories all come together at the end—the final pages had a great payoff.

Content warnings for misogyny, sexual assault, domestic abuse, child abuse, homophobia, ableism, classism.

#celestial bodies#jokha alharthi#books in translation#arabic literature#women in translation#my book reviews

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silken Gazelles: A Novel

By Jokha Alharthi.

0 notes

Text

Jenny Erpenbeck für International Booker Prize nominiert

Jenny Erpenbeck hat es mit ihrem Übersetzer Michael Hofmann auf die Shortlist des International Booker Prize geschafft. Die Berliner Autorin ist in der englischsprachigen Welt sehr erfolgreich, manche sehen in ihr bereits die kommende Nobelpreisträgerin.

Die Autorin Jenny Erpenbeck hat es mit ihrem englischen Übersetzer Michael Hofmann auf die Shortlist für den International Booker Prize geschafft. Die Berlinerin ist in der englischsprachigen Welt äußerst erfolgreich, manche sehen in ihr bereits eine kommende Nobelpreisträgerin. Mit dem renommierten Preis wird der beste Roman aus dem nicht englischsprachigen Ausland ausgezeichnet.

Continue…

View On WordPress

#Alfred Döblin#Annie McDermott#Barbara Mesquita#Christian Hansen#David Diop#David Grossman#Durs Grünbein#Ernst Jünger#featured#Franz Kafka#Geetanjali Shree#Georgi Gospodinov#Hang Kang#Hans Fallada#Herta Müller#Hwang Sok-yong#IA Genberg#International Booker Prize#Irmgard Keun#Itamar Vieira Junior#Jenny Erpenbeck#Jente Posthuma#Johnny Lorenz#Jokha Alharthi#Joseph Roth#Kira Joseffson#Lucas Rijneveld#Michael Hofmann#Olga Tokarczuk#Sarah Timmer Harvey

0 notes

Text

L'albero delle arance amare | Jokha Alharthi

Zuhur, ragazza dell’Oman che studia in Inghilterra, si sente sola e fatica a trovare la sua strada in una lingua e una cultura che non sempre le permettono di esprimersi come vorrebbe. Sospesa tra passato e presente, ripensa ai legami più importanti della sua vita e riflette sulle sue radici. In una narrazione fatta di frammenti ripercorriamo con lei la storia di Bint ‘Amir, la sua nonna di…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The feet walk fast for the loving heart’s sake, but when you feel no longing, your feet drag and ache.

Jokha Alharthi

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bittersweet Books: Fiction Picks

The Scent of Burnt Flowers by Blitz Bazawule

When the windshield of his Chevy Impala shatters in a dark diner parking lot in Alabama, Melvin moves without thinking. A split-second reaction marrows in his bones from the days of war, but this time it is the safety of his fiance, Bernadette, at stake. Impulse keeps them alive, and yet they flee with blood on their hands. What is life like now that they are fugitives? Pack passports. Empty bank accounts. Set their old life on fire. The couple disguise themselves as a pastor and a reluctant pastor's wife who's hiding a secret from her fiance. With a persistent FBI agent on their trail, they travel to Ghana to seek the help of Melvin's old college friend who happens to be the country's embattled president, Kwame Nkrumah.

The couple's chance encounter with Ghana's most beloved highlife musician, Kwesi Kwayson, who's on his way to perform for the president, sparks a journey full of suspense, lust, magic, and danger as Nkrumah's regime crumbles around them. What was meant to be a fresh start quickly spirals into chaos, threatening both their relationship and their lives. Kwesi and Bernadette's undeniable attraction and otherworldly bond cascades during their three-day trek, and so does Melvin's intense jealousy. All three must confront one another and their secrets, setting off a series of cataclysmic events.

Steeped in the history and mythology of postcolonial West Africa at the intersection of the civil rights movement in America, this gripping and ambitious debut merges political intrigue, magical encounters, and forbidden romance in an epic collision of morality and power.

The Next Thing You Know by Jessica Strawser

As an end-of-life doula, Nova Huston’s job—her calling, her purpose, her life—is to help terminally ill people make peace with their impending death. Unlike her business partner, who swears by her system of checklists, free-spirited Nova doesn’t shy away from difficult clients: the ones who are heartbreakingly young, or prickly, or desperate for a caregiver or companion.

When Mason Shaylor shows up at her door, Nova doesn’t recognize him as the indie-favorite singer-songwriter who recently vanished from the public eye. She knows only what he’s told her: That life as he knows it is over. His deteriorating condition makes playing his guitar physically impossible—as far as Mason is concerned, he might as well be dead already.

Except he doesn’t know how to say goodbye.

Helping him is Nova’s biggest challenge yet. She knows she should keep clients at arm’s length. But she and Mason have more in common than anyone could guess… and meeting him might turn out to be the hardest, best thing that’s ever happened to them both.

Monster in the Middle by Tiphanie Yanique

When Fly and Stela meet in 21st Century New York City, it seems like fate. He's a Black American musician from a mixed-religious background who knows all about heartbreak. She's a Catholic science teacher from the Caribbean, looking for lasting love. But are they meant to be? The answer goes back decades--all the way to their parents' earliest loves.

Vibrant and emotionally riveting, Monster in the Middle moves across decades, from the U.S. to the Virgin Islands to Ghana and back again, to show how one couple's romance is intrinsically influenced by the family lore and love stories that preceded their own pairing. What challenges and traumas must this new couple inherit, what hopes and ambitions will keep them moving forward? Exploring desire and identity, religion and class, passion and obligation, the novel posits that in order to answer the question "who are we meant to be with?" we must first understand who we are and how we came to be.

Bitter Orange Tree by Jokha Alharthi, Marilyn Booth (Translator)

The eagerly awaiting new novel by the winner of the Man Booker International Prize, Bitter Orange Tree is an extraordinary exploration of social status, wealth, desire, and female agency. In prose that is at once restless and profound, it presents a mosaic portrait of one young woman’s attempt to understand the roots she has grown from, and to envisage an adulthood in which her own power and happiness might find the freedom necessary to bear fruit and flourish.

Bitter Orange Tree tells the story of Zuhur, an Omani student at a British university who is caught between the past and the present. As she attempts to form friendships and assimilate in Britain, she reflects on the relationships that have been central to her life. Most prominent is her bond with Bint Amir, a woman she has always thought of as her grandmother, who passed away just after Zuhur left the Arabian Peninsula. Bint Amir was not, we learn, related to Zuhur by blood, but by an emotional connection far stronger.

As the historical narrative of Bint Amir’s challenged circumstances unfurls in captivating fragments, so too does Zuhur’s isolated and unfulfilled present, one narrative segueing into another as time slips, and dreams mingle with memories.

#Fiction#Historical Fiction#to read#tbr#booklr#book blog#booktok#sad stories#bittersweet#Book Recommendations#reading recommendations#book recs#books to read#library books

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

28 Family Sagas by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, & People of Colour) Authors

Every month Book Club for Masochists: A Readers’ Advisory Podcasts chooses a genre at random and we read and discuss books from that genre. We also put together book lists for each episode/genre that feature works by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, & People of Colour) authors. All of the lists can be found here.

Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi

An Unlasting Home by Mai Al-Nakib

Salt Houses by Hala Alyan

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

These Ghosts Are Family by Maisy Card

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo

Caramelo by Sandra Cisneros

The Antelope Wife by Louise Erdrich

Woman of Light by Kali Fajardo-Anstine

Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Calling for a Blanket Dance by Oscar Hokeah

And the Mountains Echoed by Khaled Hosseini

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama

Kintu by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison

Things We Lost to the Water by Eric Nguyen

The Mountains Sing by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai

Evening is the Whole Day by Preeta Samarasan

A Kind of Freedom by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

Memphis by Tara M. Stringfellow

Cane River by Lalita Tademy

The Valley of Amazement by Amy Tan

Daughters of the New Year by E.M. Tran

The Strangers by Katherena Vermette

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

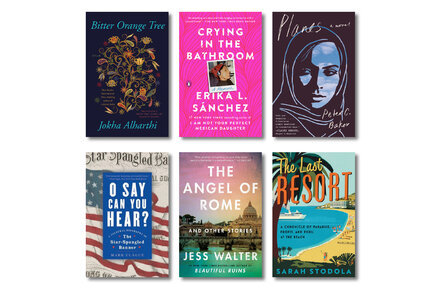

Antonio Velardo shares: 6 New Paperbacks to Read this Week by Shreya Chattopadhyay

By Shreya Chattopadhyay

Recommended releases from the Book Review, featuring books by Erika L. Sánchez, Jess Walter, Jokha Alharthi and more.

Published: June 30, 2023 at 03:52PM

from NYT Books https://ift.tt/1lu2RNo

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

“ Il 25 settembre 1926, ‘Ankabuta detta Canna di bambù stava facendo legna nel deserto quando, senza preavviso, le iniziarono le doglie. In quel preciso momento, mentre lei dava alla luce la sua bambina e con un coltello arrugginito tagliava il cordone ombelicale che le univa, alcuni uomini riuniti a Ginevra firmavano la convenzione che aboliva la schiavitù e dichiarava reato la tratta di esseri umani. Quel giorno, ‘Ankabuta compiva quindici anni e di certo non sapeva niente di quel trattato, così come ignorava bellamente che esisteva una città chiamata Ginevra.

‘Ankabuta strappò in due il velo impolverato che le copriva la testa, avvolse la bambina in una delle metà, si risistemò l’altra sulle spalle e tornò ad ‘Awafi scalza e a capo scoperto. Quando arrivò a casa di Shaykh Sa‘id – che con quella nascita guadagnava una schiava in più – le altre donne l’aiutarono a entrare e a sdraiarsi su una stuoia. Una di loro strofinò un dattero sulle labbra della neonata. Poi gliela posarono accanto e ‘Ankabuta, vedendo quel corpicino grinzoso avvolto nel suo velo, scoppiò in lacrime. Era l’unico che non si era ancora strappato impigliandosi in qualche ramo. Non l’aveva tinto con l’indaco scuro per farlo diventare blu come l’altro che aveva e che ormai era tutto sbrindellato, però la trama teneva ancora bene e, a parte la polvere che scuriva il bianco, poteva passare per nuovo. Ed ecco, adesso era rovinato. Una settimana dopo, lo shaykh annunciò che la bambina appena nata si sarebbe chiamata Zarifa. Disse, però, che non avrebbe sacrificato nemmeno un animale per lei perché quell’anno, purtroppo, la raccolta dei datteri era andata male.

Sedici anni dopo l’avrebbe venduta al mercante Sulayman, che avrebbe fatto di lei la sua schiava, poi la sua concubina e, infine, l’unica donna che fosse mai stata vicina al suo cuore. Lui, il mercante Sulayman, sarebbe stato l’unico uomo che Zarifa avrebbe amato e rispettato fino alla fine dei suoi giorni. In lui avrebbe visto per sempre la persona che l’aveva liberata dalle angherie dei figli di Shaykh Sa‘id, l’amante che le aveva insegnato i piaceri del corpo, l’uomo che le aveva insegnato il sottile gioco della crudeltà e della gelosia. Nonché il vecchio che era tornato da lei per morire tra le sue braccia. “

Jokha Alharthi, Corpi celesti, traduzione dall'arabo di Giacomo Longhi, Bompiani (collana Narratori Stranieri), 2022¹; pp. 147-148.

[Edizione originale: سيدات القمر (Sayyidat el-Qamar; Le signore della luna), editore Dār al-Ādāb, Beirut, Libano, 2010]

#Jokha Alharthi#Corpi celesti#letture#leggere#libri#Oman#letteratura araba contemporanea#citazioni letterarie#schiavitù#Convenzione sulla schiavitù#diritti umani#maternità#Mascate#diritti delle donne#Ginevra#deserto#penisola araba#avidità#storia degli Arabi#sottomissione#crudeltà#Giacomo Longhi#storia della schiavitù#sopraffazione#patriarcato#paternalismo#tratta di esseri umani#scrittrici#romanzi arabi#narrativa

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coming in May: Books by Maya Abu al-Hayyat, Jokha Alharthi, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra & More

Coming in May: Books by Maya Abu al-Hayyat, Jokha Alharthi, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra & More

Book publication dates shift, and thus we are supplementing the annual list of forthcoming literature in translation with monthly lists, which we hope are more accurate. If you know of other works forthcoming this month, please add them in the comments or email us at [email protected].

*

Solitaire: A Novel, by Hassouna Mosbahi, tr. William Maynard Hutchins

This novel takes readers into one day…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

But the one text she had found truly memorable and compelling was the passage she had memorised without even really understanding what it meant. Something about spirits or souls that were perfectly round once upon a time but had been split apart. For as long as they were separated they would search out their other half until they found it. That is how she imagined love: a meeting of spirit-twins.

-Jokha Alharthi, Celestial Bodies, 2010

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Booth’s translation honors the elliptical rhythms of Arabic and the language’s rich literary heritage. She imbues the book’s numerous poetic extracts with lyricism and devotedly preserves the rhymes and cadences of its proverbs. (“The feet walk fast for the loving heart’s sake, but when you feel no longing, your feet drag and ache.”) Yet there is no doubt that this is a contemporary novel, insistent and alive.”

#celestial bodies (book)#jokha alharthi#beejay silcox#nytimes#Marilyn Booth#catapault#omani literature#Arabic literature#man booker international prize#womenintranslation

17 notes

·

View notes

Quote

How could the house ever be spacious enough to hold all of my passion? How did its single balcony bear up under me, as I stood there alone, weighted down by so much love, without collapsing onto the dirt street or fragmenting, to be carried off by the breezes into God’s heavens? How did the small room bear the tons of clouds I kept stored away in there, simply so that I could walk across them? How did the walls stay still and unshakeable, never once quaking with the torment of my unbearable joy?

Jokha Alharthi, Celestial Bodies trans. by Marilyn Booth

#currently reading#jokha alharthi#celestial bodies#love#man booker international#booker prize winner

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And it wasn’t possible to change anything. What was written, was written. “All your tears and begging don’t erase a single line of what is written.”

Jokha Alharthi (born 1978), from “Bitter Orange”, translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth

48 notes

·

View notes