#Denys Lasdun

Text

Keeling House, Bethnal Green, London, 1956-9.

Architect: Denys Lasdun

Photography: Tom Bell

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bankside Twilight 🍹

Bonus and more on the other socials — links below!

Instagram // Twitter // Threads // VK // ArtStation // Mastodon

#artists on tumblr#illustration#architecture#architecture illustration#procreate#brutalism#brutalist architecture#concrete#national theatre#denys lasdun#london#modern architecture#sunset#cyhsal

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

20230225. 【🎭】 // Chiaroscuro: Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre.

Beloved Southbank icon and Lasdun’s magnum opus. This is his finest work. The NT is the most magnificent summation of his favourite tropes and motifs, all synthesised into one great building of austerity and gracefulness — quintessential qualities of the architect imbued into the fabric of his architecture to immense success. A noble building conceived by a noble human being.

Throughout his illustrious career, one of Lasdun’s most enduring architectural loves was Hawksmoor. That influence is most discernible in the NT; at the height of his design capabilities, Lasdun responded to that shadowy genius of the English Baroque with his own profound sensibilities. I have no doubt that if Hawksmoor had lived 300 years later, the respect would have been mutual. Here is an intellectual dialogue across three centuries between one inventive man and another.

Inside the NT, space unfolds and expands endlessly. The bulky concrete columns rise like towering trees of deep woods — perhaps a distant trace of the Gothic — while the strata terraces become labyrinthine levels joined by stairways punctured by expository interstices. One feels infinitesimally small amidst the monolithic world of rough grey concrete, made brilliantly exciting by the beautiful natural finish left by timber formwork.

The spatial complexity renders the public realm another stage, on which unfolds the minutiae drama of human life. There is no better place for people watching, or else spending a peaceful afternoon, immersed in the oxymoronic solitude amongst others made possible by the building.

As night falls, the theatrics of architecture multiply tenfold; discordant shadows elongate and swell across the landscape in sensational gestures. The impressive geometries are also transformed as lights flicker on between the structural lattices. Concrete is a spectacular backdrop for dancing lights, manmade or natural.

But look now, theatregoer, the curtains are falling — time to leave the entrancing realm of elegant Brutalism and retire to the rhythm of society. Tomorrow life carries on as it always has.

☞ studygram

#studyblr#studyblr community#archiblr#architecture studyblr#architecture student#dark academia#dark academia aesthetic#architecture#places#brutalism#brutalist architecture#modern architecture#national theatre#denys lasdun#london#writing#venetianwindow#heyzainab#studyvan#astudentslifebuoy#learnelle#nihaohoney#myhoneststudyblr#heysantiago#heypeachblossom#problematicprocrastinator

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

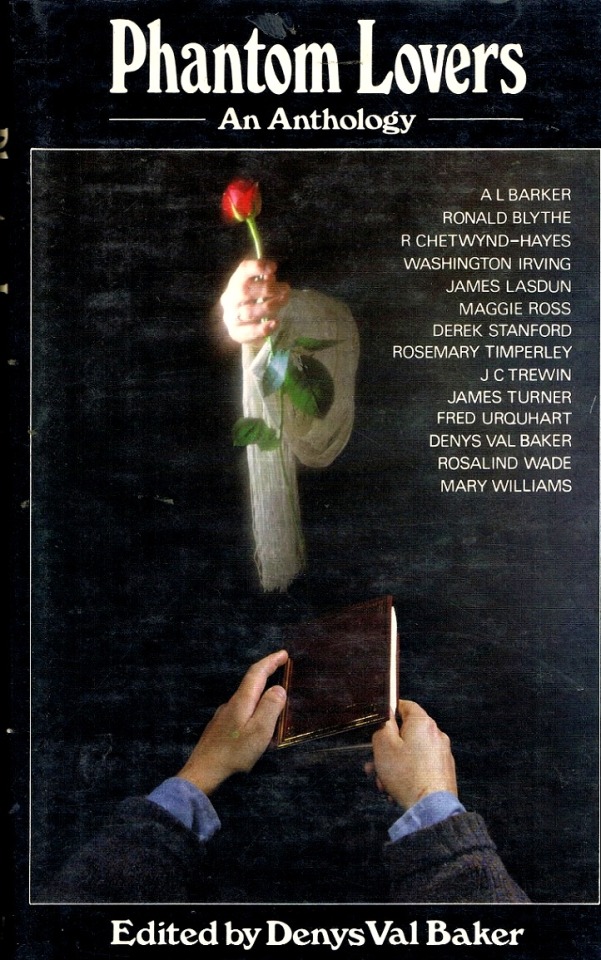

Denys Val Baker (editor) - Phantom Lovers - William Kimber - 1984

#witches#phantom lovers#occult#vintage#phantoms#lovers#william kimber#denys val baker#a.l. barker#ronald blythe#r. chetwynd-hayes#washington irving#james lasdun#maggie ross#derek stanford#rosemary timperley#j.c. trewin#james turner#fred urquhart#rosalind wade#mary williams#1984#anthology

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week on things Lettie is becoming insane about: Modernist architecture and industrial design

#unpopular tumblr opinion but I really do like modernism and a bit of minimalism here and there#I do love postmodernist architecture too and that’s probably next on the schedule#denys lasdun is my favourite architect btw#I guess because I’ve seen so many of his works in person in comparison to other architects#the design behind keeling house is quite pleasant and refreshing and finding out they went from council houses to luxury apartments sucks

1 note

·

View note

Text

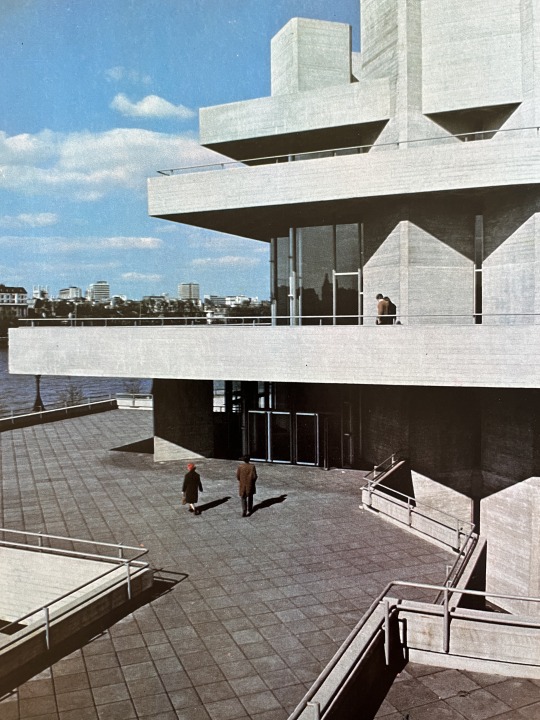

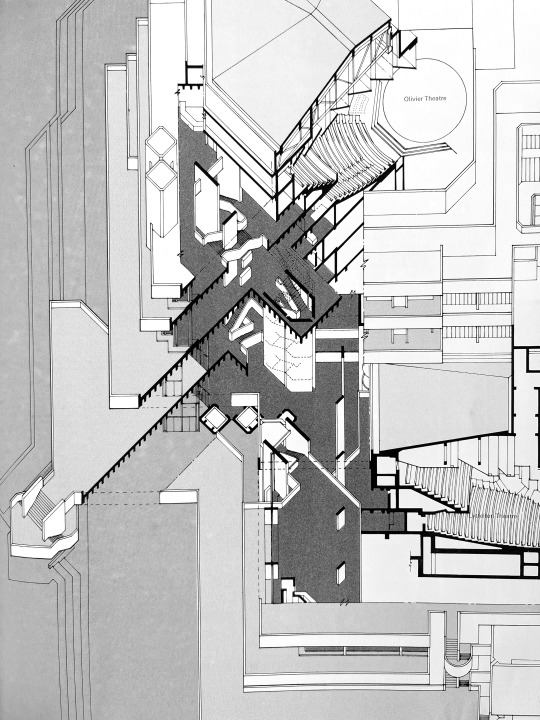

National Theatre, South Bank

1969-76

Denys Lasdun & Partners

Denys Lasdun

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

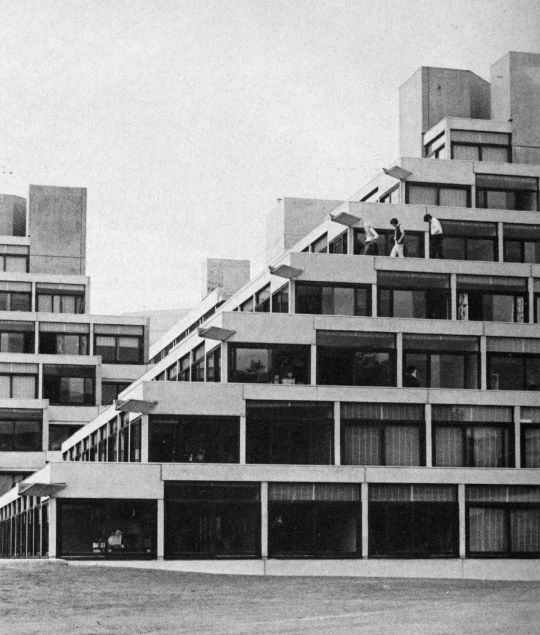

University of East Anglia / Norwich / 1970

Denys Lasdun

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

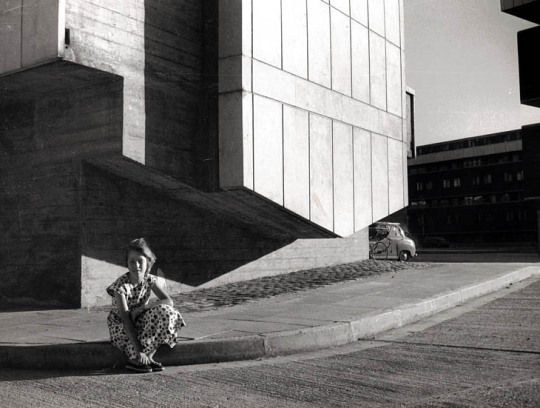

Denys Lasdun, Keeling House housing, Claredale Street, Bethnal Green, 1956-9, London, UK.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

For almost four decades Elain Harwood (*1958) has been researching and writing about British postwar architecture, greatly contributing to their protection and creating awareness of their quality. Her magnum opus „Space, Hope and Brutalism: English Architecture 1945-1975“, published by Yale University Press in 2015, is a 700+ page tome in which she recounts the better and lesser-known currents of English postwar architecture. Although prominent figures like Peter & Alison Smithson, Denys Lasdun or Basil Spence naturally receive the space they deserve based on their importance Harwood sheds particular light on the unsung architects working in local authority offices, e.g. Rosemary Stjernsted, who designed a broad range of buildings and structures for their local areas of responsibility.

Against the background of a generally bad reputation of postwar architecture and urbanism in Britain Harwood also discusses the conflicts within planning processes: flaws have often been associated with a dogmatic omnipotence infused with Corbusian thoughts, an assumption that is very much unsustainable as architects and planners operated in a complex context of underfunding, last-minute alterations and lack of materials. The often young architects responsible for the execution of these lackluster plans themselves regularly quarreled with their position within the system and the high hopes they initially had. Accordingly the circumstances for the realization of ambitious plans couldn’t have been worse.

The architectural quality of those buildings and plans still existing is nonetheless striking and ranges from sleek Scandinavian-influenced early postwar modernism to Brutalism and early High-Tech, an immense degree of breadth that leaves the reader indeed astonished.

In view of the incredible richness of the book’s information it is a publication to frequently return to in order to read about a certain time period rather than something to consume in one go, a circumstance that in no way diminishes the enjoyable reading experience.

#architecture#england#english architecture#architecture book#yale university press#book#monograph#brutalism

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Royal National Theatre, London / Denys Lasdun, 1976

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Go For It, Lasdun! 💖

Tell me why he has the most incredible range of canon pairings and why all of them are good 🍒

(Featuring Susan Lasdun, Patrick Gwynne, Laurence Olivier, Lindsey Drake, Ove Arup, and Berthold Lubetkin)

Instagram // Twitter // Threads // Bluesky // VK // ArtStation // Mastodon

#artists on tumblr#illustration#digital illustration#architecture#digital art#procreate#denys lasdun#go for it nakamura#ganbare nakamura kun#ガンバレ中村くん#syundei#redraw#character illustration#character art#cyhsal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

220923 • 6:03pm 👩🏫

Denys Lasdun’s Institute of Education.

☞ studygram

#studyblr#studyblr community#archiblr#architecture studyblr#architecture student#bookblr#library#libraries#brutalism#brutalist architecture#dark academia#dark academia aesthetic#light academia#light academia aesthetic#venetianwindow#heyzainab#studyvan#astudentslifebuoy#myhoneststudyblr#heysantiago#heypeachblossom#architectingly#tusermelissa

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The National theatre, London. Designed by Denys Lasdun and completed in 1976. This is one (of many) of my favourite buildings in London. I acually worked here, in the prop-shop on the "Drum Road" and loved it. Such a wonderful example of "Brutalist" achitecture. This sketch was prepared for a film, but ended up on the cutting room floor. Pen sketch using a TWSBI fountain pen and De Artrementis ink.

#sketching #dailysketch #drawing #penandink #sketchjournal #london #urbansketchers #drawingoftheday #pen #journalingl #pendrawing #pensketch #architecture #building #London #nationaltheatre

www.charlesleon.uk/books

1 note

·

View note

Text

...and he built a crooked house

Barnabas Calder’s book Raw Concrete deals with the brutalist architecture of substantial British buildings of the 60s and 70s—housing and other institutional buildings, for the most part. But it starts with a description of the author’s pilgrimage to Hermit’s Castle, near Achmelvich on the Atlantic Coast of the Scottish highlands. Built in 1955 by an unknown young architect called David Scott, with his own hands, the so-called castle is a perplexing example with which to start the book. Expressive and irrational, it exists outside of the canon of architecture, and can be seen as a raw exercise of the young architect’s causal powers, uncontaminated by considerations of prestige or professional acceptance. No divine inspiration or sacred purpose appears to have been behind the construction: he built it over a period of six months, and then immediately left the area for good. We don’t know whether he considered the concrete structure to be an achievement or a failure. It seems that he was somehow possessed with a mania for concrete, and built, concerned with the process rather than product, drawing all of his materials (except for Portland cement) and possibly his inspiration from the barren landscape. Solitude, monomania, the monolithic in-situ mixing, pouring, dripping, concrete event: this is closer to fetishistic sculpture than it is to architecture. As Vasari put it, an artist can be distinguished by invention “facile and peculiar to himself”. Scott’s personal folly contained only space for one person; once he departed, it became redundant. There is a crassness to this gesture of leaving behind a pile of useless concrete for others to deal with.

It seems fair to disqualify Hermit’s Castle from the category of architecture because it lacks organisation; perhaps it is inhabitable (though I am not sure how well the fireplace functions) but it lacks the coherence and consistency that are essential to all architecture. It was neither consecrated as some kind of hermitage nor sanctioned as a real dwelling; although, as Calder observes, its function is absolutely fixed by the solidity of its concrete walls, it is not dedicated to any purpose. In the history of brutalist architecture, the problematic adjective “bloody-minded” recurs. The notion that the architect is being awkward, obdurate, and producing buildings that reflect the same mood, has never seemed accurate to me. Though the (in my opinion bad) brutalist architect Owen Luder claimed to believe that his buildings could speak, they would say “sod you”, this seems to compound the misunderstanding that the term brutalism caused. As Calder records, Denys Lasdun (a much better architect) was unhappy with the label brutalist. His buildings seem to me instead to reflect a cosmopolitan broadmindedness—hardwearing, perhaps, but cultured and democratic. Brutalism names a felt desire to épater les bourgeois, 'a brick-bat flung in the public's face’ (Reyner Banham) but the intention was to open minds and make an architecture worthy of the circumstances in which it was created. It is difficult to look at the Hermit’s Castle and detect any political affiliation inscribed in its constructional details. It is painterly, perhaps casual, “informal” like the art of the time, but ultimately just one man’s self-expression.

T.H. White wrote a book for children called The Master, which was published in 1957. It describes the operations of the titular proto-Bond-supervillain, who has hollowed out the islet of Rockall, far out in the Atlantic. His plan for world domination is to use sci-fi vibrator units pointing outward from Rockall to incapacitate the whole of Europe and America. It’s not a particularly good book, but it comes to mind for its combination of megalomania, remoteness, and the basic problem of creating inhabitable space in extremely inhospitable conditions. As in the case of Bond villains, the scale of the operation, and how it has been built up, is not fully explained. Did the Master have an architect?

The quiet, clean, warm and dry interior of his Rockall is an intriguing image. The rock has been crammed with equipment and accommodation, but remains disguised, like Tracy Island or any other classic Volcano Lair.

David Scott was not a villain, though he built a crooked house for himself. His labour in building the Hermit’s Castle was presumably not alienated from his own objective—he was working for himself on a project of his own devising. It must have been hard work, much more akin (obviously) to a building site than to the quiet cleanliness of an architect’s office. The brutalist impulse to build in an unsoftened, direct way must have something to do with the founding trauma of architecture. As soon as the profession of architect emerged, the two key places of the construction process, the building site and the drawing table, started to drift apart. The exaggeratedly rough and tough credentials of brutalism can be seen as attempt by architects to reclaim the immediacy of the building site—which is not so far away from what happened at Hermit’s Castle. But Hermit’s Castle is not a success story, and there is good reason to doubt the authenticity of the brutalist impulse. Calder describes the corruption and greed of developers the 70s. Brutalism claimed at first to be concerned with truth to materials, but evolved into a style like any other—a wasteful style and one that was imposed thoughtlessly.

Perhaps the way to think about this is to consider whether it matters that David Scott’s concrete folly is robust; whether it is sincere. It may genuinely be these things, while still being an eyesore. It maybe an unimpeachably “straight shot” at elemental architecture that still misses its target. Like the brutalist buildings of the 60s and 70s, it falls into the category of relics, some beautiful, some grim, some adaptable, some unusable.

0 notes