Text

Neue Maxburg (1954-57) in Munich, Germany, by Sep Ruf & Theo Pabst. Photo by Hans Baerend.

#1950s#office building#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architektur#munich#sep ruf#theo pabst

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

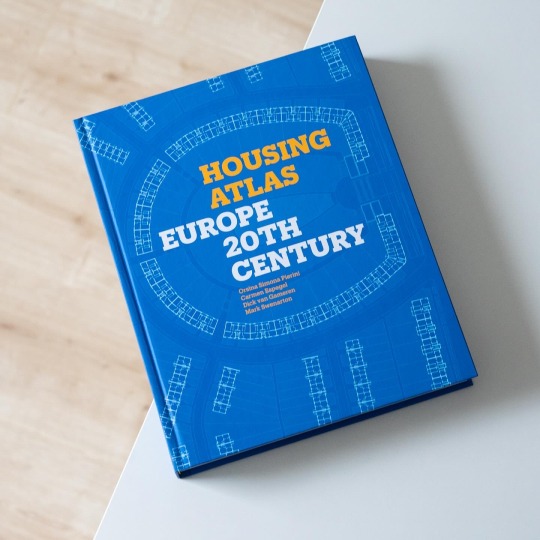

A hundred years ago the question of housing was as pressing as it is today: in view of the unbroken influx of people into the metropolitan areas housing construction is an issue cities, planners and architects intensely struggle with, especially because land costs and thus rents are constantly increasing as well. But the development of housing also is a story of innovation, imagination and progress: not so much in terms of extravaganza but in terms of models that others can build upon. This genealogy, at least in terms of Europe, has been comprehensively processed by Orsina Simona Pierini, Carmen Espegel, Dick van Gameren and Mark Swenarton in their weighty „Housing Atlas: Europe - 20th Century“, published late last year by Lund Humohries. In chronological order the atlas covers 87 projects ranging from Parker and Unwin’s Hampstead Garden Suburb in London to Herzog & De Meuron’s Rue des Suisses in Paris with each project being documented in a uniform set of plans and comprehensive illustrations. The dossiers are further contextualized by four essays penned by each of the contributing authors that address a wide range of topics related to housing in 20th century Europe, e.g. the relationship between the public and the private, the increasingly un-contextual designs of the postwar decades or the translation of past insights into new projects. To these more detailed essays Mark Swenarton provides a bracket by recounting the history of housing and by establishing a sequence of developments that facilitate the understanding of the projects featured.

With the present atlas the authors have written nothing less than a reference work on 20th century European housing: by establishing a canon of exemplary projects and supplementing them with excellent plan material the book qualifies for any professional’s library as a go-to source for inspirational housing designs. Highly recommended!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Purfina Gas Station (1955-57) in Arnhem, the Netherlands, by Sybold van Ravesteyn. Photo by Huib Kooyker.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Town Hall (1967-70) in Sindelfingen, Germany, by Günter Wilhelm & Jürgen Schwarz

#1960s#interior#stairs#concrete#brutalism#brutalist#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#günter wilhelm#jürgen schwarz

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lounge Chair "Model 416" (1957) designed by Wim Rietveld & André Cordemeyer for Gispen

#1950s#design#furniture design#lounge chair#wim rietveld#dutch design#netherlands#modern design#andre cordemeyer

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

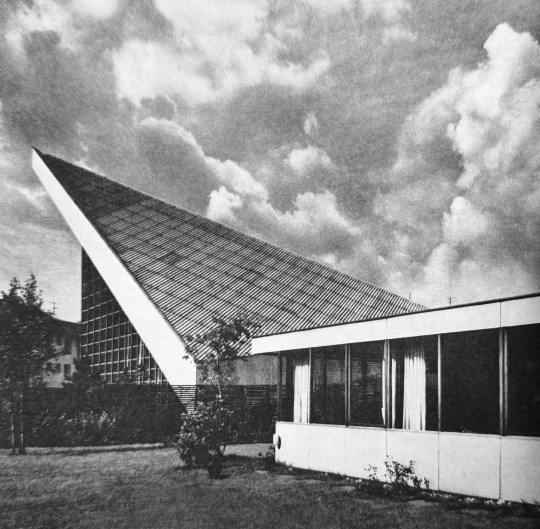

Stephanuskirche (1963-65) in Cologne, Germany, by Fritz G. Winter & Ingeborg Winter-Bracher

#1960s#church#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architektur#cologne#fritz g. winter#ingeborg winter-bracher

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Municipal Library (1973) in Neumarkt, Germany, by Franz Xaver Heid

#1970s#library#concrete#brutalism#brutalist#architecture#germany#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur#franz xaver heid#sosbrutalism

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bagsværd Church (1973-76) in Bagsværd, Denmark, by Jørn Utzon

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

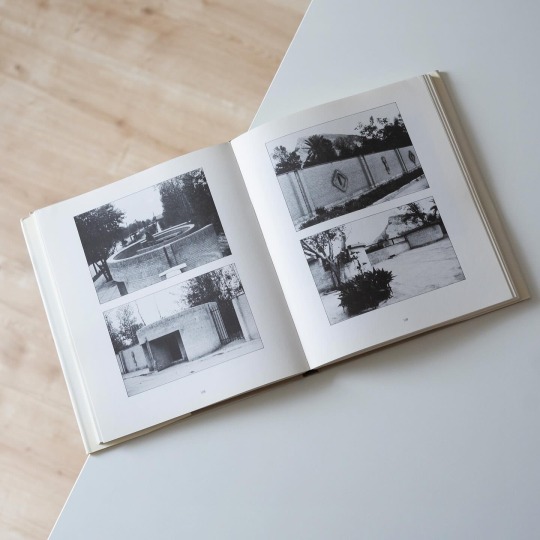

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran not only hides an incredible collection of modern art in its depots but itself also is a piece of art: designed by Kamran Diba (*1937), cousin of the then wife of Shah Reza Pahlavi and founding director of the museum, it is a fascinating blend of western modernism and Persian tradition. Diba studied architecture at Howard University in Washington D.C., USA, and after graduating graduated in 1964 and in 1966 returned to Iran where he became President and Senior Designer of DAZ Consulting Architects, Planners and Engineers and also served as urban planning consultant to Iran's Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. Until 1977, the year he left Iran to become Visiting Critic at Cornell University, Diba realized not only the aforementioned museum but also, although only partially, the Shushtar New Town, several buildings of the Jondi Shapour University at Ahvaz as well as several smaller mosques and prayer spaces.

These works are summarized in the present volume, published in 1981 by Hatje: „Kamran Diba - Buildings and Projects“, penned by the architect himself, provides a comprehensively illustrated overview of Diba’s Iran projects with which he certainly put an end to his Iranian works since the post-revolution Iran was in no way a healthy environment for his architectural ideas. In his introduction Diba in detail explains his aim to design buildings that stimulate social encounters and exchange, a tendency that he attributes to both his growing up in high-density Tehran but also his admiration for Italian old towns that ultimately led him to examining old Persian town structures.

Although the book contains little text, the illustrations and plans nonetheless offer deep insights into Kamran Diba‘s spatial organization and how he designs buildings as sociable, even friendly, entities that are imprinted with a deeply humane character. A wonderful antiquarian find!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kunsthalle (1956-57) in Darmstadt, Germany, by Theo Pabst

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hofplein Station (1956) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, by Sybold van Ravesteyn

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sports Hall “Glaspalast” (1975-77) in Sindelfingen, Germany, by Behnisch & Partner. Photo by Christian Kandzia.

#1970s#sports hall#glass#steel#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#günter behnisch

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Church St Christophorus (1965-67) in Neu-Isenburg, Germany, by Helmut Bilek

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galka Scheyer House (1934) in Los Angeles, CA, USA, by Richard Neutra

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armchair (1932-33) designed by Rudolph M. Schindler for Sardi's Restaurant and manufactured by Warren McArthur Corporation.

#1930s#armchair#modern design#american design#furniture design#design history#design#usa#rudolph michael schindler

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Home for the Elderly "Karenhuizen" (1916-19) in Alkmaar, the Netherlands, by Jan Duiker & Bernard Bijvoet

#1910s#amsterdamse school#brick#modernism#modernist#architecture#netherlands#alkmaar#jan duiker#bernard bijvoet

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapel (1961-63) of the St Klemens School Campus in Ebikon, Switzerland, by Max & Werner Ribary

98 notes

·

View notes