#17th c. costume

Text

17th century mule shoes;

Women's mule. Velvet, embroidered with raised silver thread, leather heel. England, c. 1650

Mule. Possibly man's, silk, embroidered with raised work in silk and silver thread, leather heel. Britain, 1660s-70s

Mule shoe. Silk and embroidered with raised work in silk and silver thread and leather heel. England, 1660-80

#shoes#mules#costume#17th century#mdpcostume#17th c. costume#footwear#britain#17th c. Britain#1650s#1660s#late 17th century#1670s#mid 17th century

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s that time of the year when I pretend I’m not a trash goblin

#carnevale 2023#carnevale#carnevale di venezia#historical costume#historical costuming#baroque#17th century#17th C#1790s#1790s fashion#regency era#italian renaissance#late 1400s#early 1500s

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early 18th (and late 17th) century fashions are so under-utilized in vampire media and I think it's a damn shame.

I don't actually think I've ever seen a single image of a vampire character in an early 18th century suit. Hardly any movies set in that era either, and hardly any historical costumers who do it.

(Even my beloved gay pirate show set in 1717 takes nearly all of its 18th century looks from the second half of the century. Not enough appreciation for baroque fashion!!)

Yes I love late 18th century fashion as much as anyone, and 19th century formal suits are all very well and good, but if you want something that says old, dead, wealthy, and slightly dishevelled, then the 1690's-1730's are where it's at.

(Retrato del Virrey Alencastre Noroña y Silva, Duque de Linares, ca. 1711-1723.)

There was so much dark velvet, and so many little metallic buttons & buttonholes. Blood red linings were VERY fashionable in this era, no matter what the colour of the rest of the suit was.

(Johann Christoph Freiherr von Bartenstein by Martin van Meytens the Younger, 1730's.)

The slits on the front of the shirts are super low, they button only at the collar, and it's fashionable to leave most of the waistcoat unbuttoned so the shirt sticks out, as seen in the above portraits.

(Portrait of Anne Louis Goislard de Montsabert, Comte de Richbourg-le-Toureil, 1734.)

Waistcoats are very long, coats are very full, and the cuffs are huge. But the sleeves are on the shorter side to show off more of that shirt, and the ruffles if it has them! Creepy undead hands with long nails would sit so nicely under those ruffles.

(1720's-30's, LACMA)

Embroidery designs are huge and chunky and often full of metallic threads, and the brocade designs even bigger.

(1730's, V&A, metal and silk embroidery on silk satin.)

Sometimes they did this fun thing where the coat would have contrasting cuffs made from the same fabric as the waistcoat.

(Niklaus Sigmund Steiger by Johann Rudolf Huber, 1724.)

Tell me this look isn't positively made for vampires!

(Portrait of Jean-Baptiste de Roll-Montpellier, 1713.)

(Yeah I am cherry-picking mostly red and black examples for this post, and there are plenty of non-vampire-y looking images from this time, but you get the idea!)

And the wrappers (at-home robes) were also cut very large, and, if you could afford it, made with incredible brocades.

(Portrait of a nobleman by Giovanni Maria delle Piane, no date given but I'd guess maybe 1680's or 90's.)

(Circle of Giovanni Maria delle Piane, no date given but I'd guess very late 17th or very early 18th century.)

Now that looks like a child who's been stuck at the same age for a hundred years if I ever saw one!

I don't know as much about the women's fashion from this era, but they had many equally large and elabourate things.

(1730's, Museo del Traje.)

(Don't believe The Met's shitty dating, this is a robe volante from probably the 1720's.)

(Mantua, c. 1708, The Met. No idea why they had to be that specific when they get other things wrong by entire decades but ok.)

(Portrait of Duchess Colavit Piccolomini, 1690's.)

(Maria van Buttinga-van Berghuys by Hermannus Collenius, 1717.)

Sometimes they also had these cute little devil horn hair curls that came down on either side of the forehead.

(Viago in drag Portrait of a lady, Italian School, c. 1690.)

Enough suave Victorian vampires, I want to see Baroque ones! With huge wigs and brocade coat cuffs so big they go past the elbow!

#long post#vampires#fashion#history#18th century#17th century#someday. SOMEDAY I will make a black/red/dark orange/metallic gold 1720's suit#I've got nearly all the materials I just need to:#1. Learn how to make early 18th century metallic thread buttons‚ preferably without having to buy the super expensive kind of thread#2. get a wig and style it appropriately

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketches of all my redone designs for my Phantom Thieves from my AU, Icarus! Lots of info down below on the cut, so if you want to know more about the details and inspiration, feel free to keep reading!

This includes Akechi’s design for his Princely/Robin Hood attire, BEFORE his Icarus attire you might have seen from my other posts! Check out the Icarus AU tag for more info! Icarus has a main focus on Akechi and his relationship to the thieves, but the AU is actually an entire rewrite with new designs, 3rd semester and epilogue/strikers/tactica stories, hence Zenkichi and Sophia’s inclusion.

Read below for individual info:

I decided to include more motifs towards their persona’s and general vibes; and also just my own personal touches haha.

AKIRA - Not much has changed, I really like his design overall. I raised his boots to be like Arsene’s and changed his neck area.

MORGANA - I hate the OG pill shaped head, his new design is based heavily on the shape of Palico’s from Monster Hunter. Added a little more nod to Zorro/His persona motifs and also just made him cuter! Little hamburger headed cat.

RYUJI - I made him a little bulkier and gave some more weight to his outfit overall. I gave him heavier boots and a slightly buffer build to relate back more to his sporty style.

ANN - honestly was never too big on her latex outfit, I wanted to call back to a personal favorite female lead; Christine Daae, and used one of the versions of her Don Juan costume as inspiration. I remember seeing Phantom live and in many stage versions of her character, the Don Juan scene was a pure moment of female control, and she was truly working the Phantom and controlling every movement on the stage. Her presence is commanding, and I thought it was a very fitting tribute to Ann’s character as feminine strength. (I’m absolutely not referring to the movie iteration of Daae btw.)

YUSUKE - I referred to some historical art and legend of Goemon to add more elements of design to his outfit. When I color them, I want to add some really strong pops of color to his clothing to really drive the aesthetics and artistry home.

MAKOTO - Another totally redid outfit, I opted to give her a design which relates back to Popess Joan, and also Anat. I gave her a clawed hand on her right side and an uncovered hand on her left as both a nod to Anat’s hand raised in iconography of her from art history, but also to show the duality of Anat’s title as both a goddess of war, and of love. It also relates to the mythology of Joan and her nature as both a leader and a martyr. I changed her mask to a Venetian Commedia mask as well.

FUTABA - ok. I’ll be honest. I never liked her skin-tight outfit, it just doesn’t match her personality at all. Also, the high tech Egyptian feel never really sold me. I totally understand the tomb thing, but I truthfully think a dungeon/palace which was more like… tech/nerd themed would have been much more “futaba” the inspiration for this new outfit relates back to her persona, the Necromomicon, as well as her nerdy personality, and her affiliation as Alibaba (Ali Baba.) I wanted to go more lovecraftian, long sleeves and patterning designed to look more like lovecraftian tendrils, and big baggy pants and her classic shoes to match. The patterning on her undershirt will resemble a rib cage, both as a reference to her deathly “tomb” iconography, but also to Lovecraftian and Necronomicon lore. I think she matches the description of a nerdy, techie DND dungeon master more than the initial outfit, so that’s the route I took personally.

HARU - relating back to some fashions from 17th c France, where Milady’s story (the three musketeers) takes place, I kept her design relatively similar. I just gave her a little more iconography relating to the three musketeers and that general timeframe.

AKECHI - in his pre-Icarus outfit, I’ve given him a princely sort of outfit befitting of his two faced nature, and edited it to relate to Robin Hood a little more. I tried to keep it sleek and just generally very concealing and layered.

SUMIRE - i gave her some iconography relating back to one of her personas, who is an inference to Freya. I also included some more nods to classic Cinderella, with fantasy gown elements. Overall, relatively similar.

ZENKICHI - again, relatively similar, I really like his outfit. I just opened up the face some to show more personality and spiced up the outfit generally to keep it matching. honestly, les mis/Valjean was a hard one, but I also think his character could be heavily related back to Edmond Dante (Monte Cristo.) so I gave some nods to that as well.

SOPHIA - I turned her into a FINGIE!!!! I made her whole dress as a nod to her persona/to pandora’s tiles around her/the pillars. I wanted to make her small and almost unnatural since she’s an AI, and I thought having a little guy on the team would add some more variation.

#persona 5 icarus au#persona 5#p5#persona 5 au#persona 5 royal#akira kurusu#ren amamiya#p5 Mona#p5 morgana#ryuji sakamoto#ann takamaki#yusuke kitagawa#makoto nijima#futaba sakura#haru okumura#akechi goro#goro akechi#zenkichi hasegawa#p5 Sophia#sumire yoshizawa#persona 5 strikers#persona#akechi#shin megami tensei#art#digital art#akeshu#shuake#gavaladraws

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

16th c. Costume Books, a Problematic Source for Dress History

But did they really dress like this?

Costume books and costume albums are a popular source for dress historians, historical costumers, and reenactors researching 16th and early 17th c. Europe. There are good reasons for this. They are primary source documents (at least sometimes), and they show the clothing of cultures and social groups that are difficult-to-impossible to find in other types of period art, like the Irish and rural peasants. Examples of these books include Trachtenbuch des Christoph Weiditz, Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il Mondo di Cesare Vecellio, and Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers. These books are, however, deeply problematic as a dress history source for several reasons. In this post, I will discuss the ways they are problematic and how those of us researching historical dress can gain a better understanding of what the people shown in these books were actually wearing. I have broken down the problems with using these images into 4 areas.

Embodied biases:

The creators of these books were, at least sometimes, prejudiced against the cultures they were portraying, and these biases may have affected how they characterized these cultures. Hans Weigel, author of Habitus praecipuorum populorum, characterized his native German fashion as modest and virtuous and characterized elaborate Italian fashions as decadent and corrupt. Weigel considered these 'strange' foreign fashions a threat to the 'civilized' German fashion he favored (Bond 2018). This bias might have motivated Weigel to idealize his portrayal of German fashion or to exaggerate the strangeness of Italian fashion in order to scare his readers away from trying it.

Weigel's dislike of flashy foreign fashions seems mild in comparison to the bigotry of some of his peers. Flemish artist Lucas de Heere and French artist François Desprez both labeled the Scottish 'savages' in their books. Jost Amman's description of a purported Turkish sex worker in the German edition of Gynaeceum, sive Theatrum mulierum, is appallingly bigoted:

"A Turkish Wh*re: This is a prostitute, who sells her impure body for dirty money to a lover that pleases her. With the earnings of this sin she dresses herself prettily and beautifully, in order to attract the Turks even more easily with her false ornaments." (translation from Ilg 2004)

Considering the blatant bigotry he shows here, I wouldn't anything about trust Amman's depictions of sex workers, Turks, or any other non-Western Europeans. Or any other women, really.

Sights unseen:

Even when costume book creators weren't actively trying to perpetuate their biases through their work, their ignorance could still cause problems. These artists did not always visit the countries whose costumes they painted. They relied on other artists' work or even just verbal descriptions to fill in the gaps in their knowledge. The resulting images can distort the cut, construction, and material of the clothing.

For example, the Turkish women in this original woodcut by Pieter Coecke van Aelst are wearing shawls or scarves with long fringe wrapped around their heads and shoulders. In the Christoph von Sternsee costume album's illustration based off Coecke van Aelst's print, the fringed shawl has become a strange, tailored hood with a panel of pleated cloth attached to either it or the gown below.

(Coecke van Aelst's woodcuts were identified as the source for the von Sternsee album's illustration in Katherine Bond's 2018 dissertation.)

Copy of a copy of what?

In spite of the problems it causes, copying from other artists' work was common in costume albums (Bond 2018). Considering that the artists did not visit all the cultures they illustrated, this is unsurprising. Some images were copied repeatedly, and the artist misunderstanding the source material wasn't the only source of distortion. Artists also made up details to compensate for bare-bones source material.

This simple line black-and-white print of an Irish woman wearing a léine (linen tunic), brat (Irish mantle), and headwear was used by several artists, all of whom made changes and additions. The first copy in this post is the most faithful to the original, but it still adds long sleeves and eyelet holes on the neckline to the léine. The coloring of the headwear suggests a wool hat crested with a tuft of horsehair and having a linen roll at the bottom. The coloring also gives the brat a contrasting lining.

The second knockoff is the most famous. It comes from Lucas De Heere's illustration which purportedly shows Irish people in service to King Henry VIII. This is some thing De Heere couldn't have actually seen, as he moved to England 20 years after Henry VIII died and never went to Ireland at all. De Heere took the most liberties with his version. His Irish woman appears to be topless under her brat. The bottom of her léine has much less volume than the original, and De Heere has added an apron. For the hat, De Heere has replaced the crest with triangles of green wool.

Unlike De Heere's version, the final version is mostly loyal to the cut shown in the original, but it makes some unlikely suggestions for the materials. The léine appears to be green silk brocade. The brat also appears to be silk. Accounts from people who actually went to Ireland in the 16th and early 17th centuries state that these garments were made of linen and wool, respectively. Both the hat and its crest are now completely made of linen.

Chronological distortion:

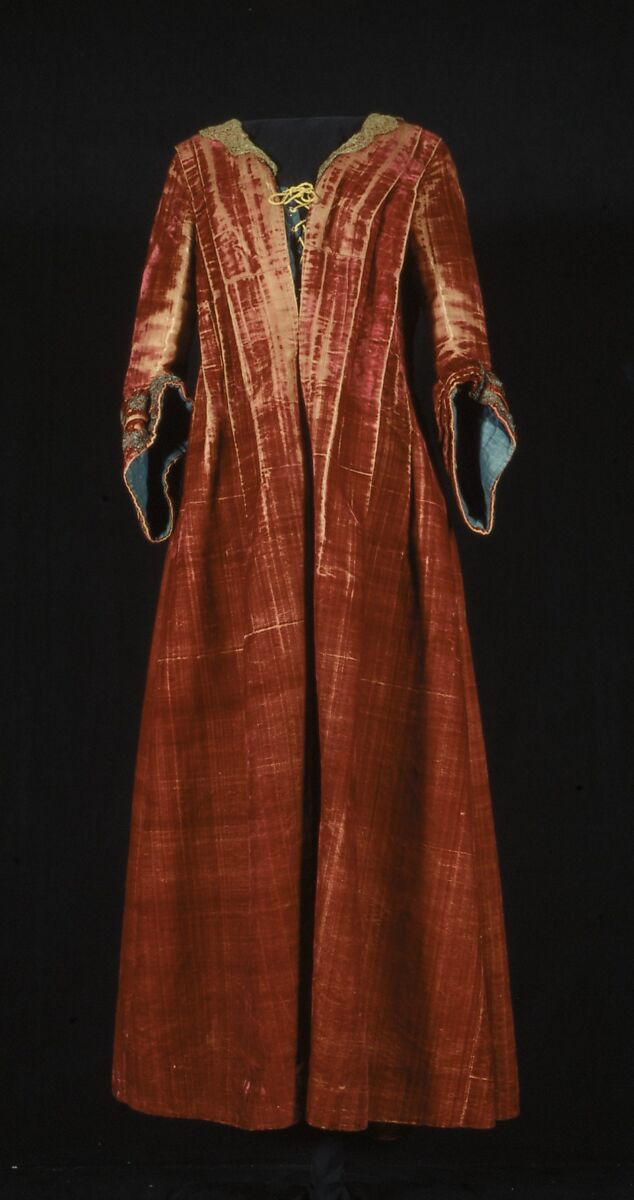

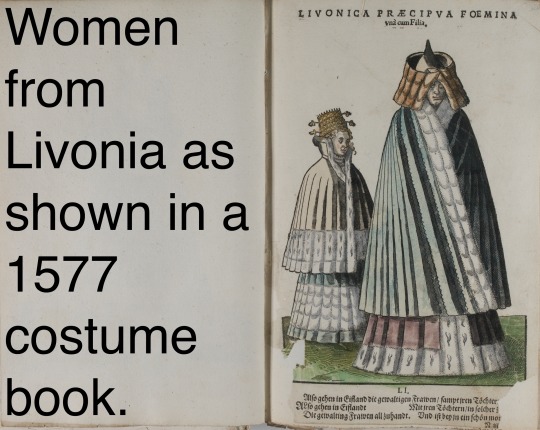

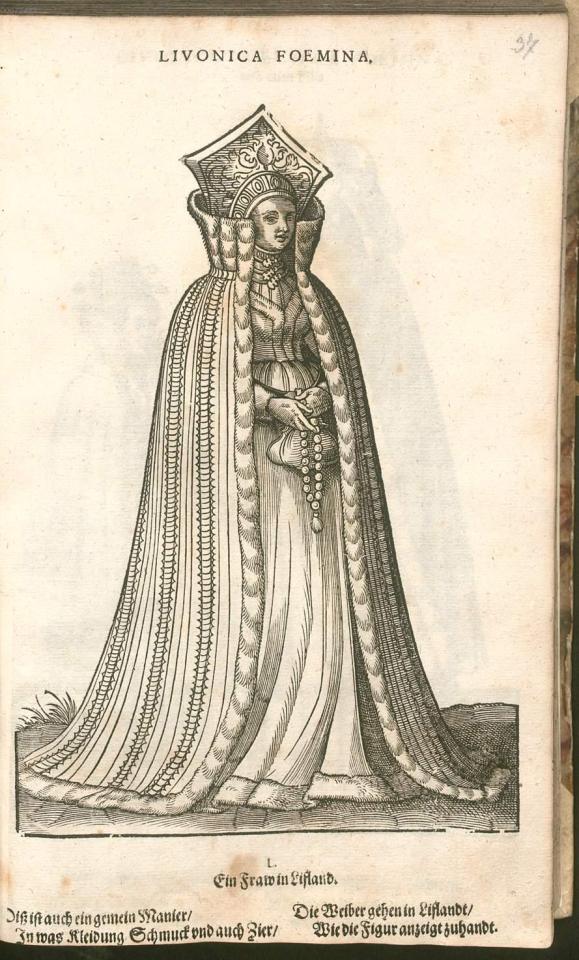

The heavy use of copying in costume books also has the potential to mislead us in terms of when these fashions were worn, because the original images may be significantly older than publication year of the books that copy them. For example, the dress of Livonian women shown in Hans Weigel's 1577 book was almost certainly copied from Albrecht Dürer's 1521 watercolors. Weigel used references that were more than half a century old, but described them as if they were contemporary fashion in 1577.

Even when costume book images are accurate portrayals of their source material, many of them lack the detail needed to identify seams, fabric types, or garment understructures. How do we deal with these problems when attempting to reconstruct what the people shown in these books actually wore?

What do we do about it?

I am not saying that we should discard these things completely as sources. Dress historians as respected as Patterns of Fashion author Janet Arnold and The Tudor Tailor authors Jane Malcolm and Ninya Mikhaila have used costume book illustrations. I definitely know less about 16th c. dress history than Jane and Ninya. I am just saying we shouldn't use them uncritically.

First, do some research on the costume book you're looking at. When was it created? Do the illustrations look suspiciously similar to those in other books? (Google image search and pinterest can be helpful for identifying this.) Did the creator, like Hans Weigel, have a particular bias they were advancing? Did they actually visit the cultures they portrayed? Christoph Weiditz actually traveled quite a bit, but he did not visit the British Isles, so his Irish and English women are probably based on someone else's art (Bond 2018). A lot of the scholarly publications about costume books are frustratingly paywalled, but some of them can be accessed for free via researchgate or academia.edu.

Avoid using copies when possible, even if the copies are more realistic-looking or more detailed art. As I discussed in the examples above, artists change things when they copy. Publication dates of copies can also be misleading in terms of dating clothing styles.

Find other sources such as: written descriptions from the time period, extant historical garments, more detailed art depicting similar fashions in related cultures, and art made by people from the culture you are studying. Period written descriptions can yield information about materials used, colors, and other details. Extant garments are your best source for information on cut and construction (unless you are lucky enough to have an extant tailor's manual from your period and culture). Detailed art depicting similar fashions can offer suggestions to fill in for missing information on construction, materials, and embellishments. Art created by the culture is valuable for identifying inaccuracies created by bigoted or ignorant artists.

Finally, remember that it's okay to not know everything. There are gaps in our knowledge about what people wore 500 years ago that will probably never be filled without a time machine. Sometimes you just have to make a plausible guess and move on. Don't let yourself get so paralyzed by doing research that you never complete the garment reconstruction/art/tumblr post you were doing the research for.

Bibliography:

Bond, K. L. (2018). Costume Albums in Charles V’s Habsburg Empire (1528-1549). https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.25054

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Ilg, Ulrike. (2004). The Cultural Significance of Costume Books Sixteenth-Century Europe. In Catherine Richardson (ed.), Clothing Culture, 1350-1650 (p. 29-47). Ashgate.

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McClintock, H. F. (1953). Some Hitherto Unpublished Pictures of Sixteenth Century Irish People, and the Costumes Appearing in Them. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 83(2), 150-155. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25510871

Costume Books mentioned:

Amman, Jost. Gynaeceum, sive Theatrum mulierum.

The Costume Album of Christoph von Sternsee. not available on-line. Katherine Bond's research is your best source for this one.

Desprez, François. Recueil de la diversité des habits.

De Heere, Lucas. Corte Beschryvinghe van Engheland, Schotland, ende Irland.

Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers, tant anciens que modernes, diligemment depeints au naturel par Luc Dheere peintre et sculpteur Gantois.

Vecellio, Cesare, and Gratilianus, Sulstatius. Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il Mondo di Cesare Vecellio.

Trachtenbuch des Christoph Weiditz

Weigel, Hans, and Amman, Jost. Habitus praecipuorum populorum, tam virorum quam foeminarum singulari arte depicti.

Kostüme der Männer und Frauen in Augsburg und Nürnberg, Deutschland, Europa, Orient und Afrika

Kostüme und Sittenbilder des 16. Jahrhunderts aus West- und Osteuropa, Orient, der Neuen Welt und Afrika

costume prints by an unknown artist, in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Cabinet des Estampes. I cannot find this one online. image taken from McClintock 1953.

#dress history#historical fashion#art#16th century#17th century#historical costuming#historical dress#cw whorephobia#cw racism#irish dress#leine#irish mantle#reenactment#costume album

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch "HOW TO GET DRESSED IN A 1610S SUIT: The Modern Maker Workroom BASICS" on YouTube

youtube

Just a huge fan of this video. Mathew Gnagy begins in his underwear, which is a long shirt similar in construction to early 19th century men's shirts, but even more gigantic, and a pair of drawers which he compares to Venetians (knee breeches c. 1570-1620). He rolls up the shirt beneath the drawers to pad his hips and the effect is amazing. It really looks so good when he completes the ensemble!

I have been reading Phillis and C. Willett Cunnington's Handbook of English Costume in the 17th Century and The History of Underclothes by the same authors. They mention 17th century breeches stuffed with bombast of "horsehair, flock, wool, rags, flax, bran or cotton" to give the desirable silhouette. (Before bombast referred to an inflated vocabulary it referred to inflated pants.) Quoting Benjamin Jonson: "Stay let me see these drums, these kilderkins, these bombard slops, what is it crams them so? Nothing but hair." (The Case is Altered, 1609).

The video is a great demonstration of "trussing the points" i.e. using ribbons or tape ties to attach the breeches and doublet, which held them together and kept the breeches on. After so much lacing and lacing I couldn't help but wonder how the clothes could come off in a timely manner—but he takes the suit off and strips to his underwear to show how quick it is to undress! (Much to consider).

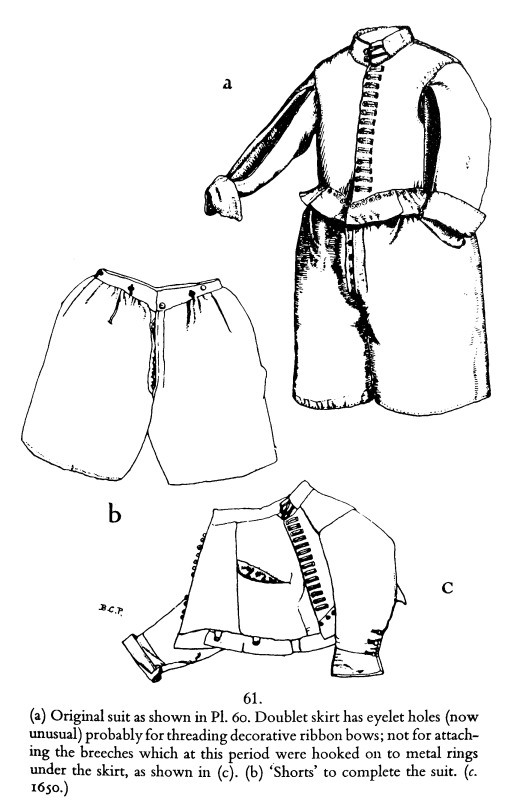

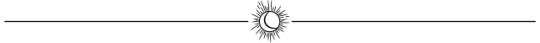

An illustration from Handbook of English Costume in the 17th Century shows that the basic suit-shape is the same at midcentury, but the breeches are now held up by metal rings under the doublet skirt and the ribbon bows peeking out are decorative.

#17th century#dress history#fashion history#historical men's fashion#1610s#1650s#fashion#living history#1600s board shorts my beloved#also i love seeing how the lace collar is put on!#bring back men padding their hips and butts#back that thing up king

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little subtle things that touch on racism in young royals: the 17-18th century costumes for the valentines ball. Not only are the costumes hearkening back to an exclusionary ‘golden age’ the costuming includes makeup that makes the skin appear lighter. We see at least Wille and Maddison in. Having this kind of make up is so so exclusionary - because like the wigs that Felice refuses to wear, to engage with the activity properly non-white students are being tacitly encouraged to lighten their skin and white students are being tacitly encouraged to value whiteness

And yes it’s a fun dress up heritage activity that includes make up for the reenactment purposes - I get that heritage is literally what I’m studying BUT one of the big discussions within the heritage field is the ongoing question of whose heritage is celebrated and why?

For example - it makes no sense for Hillerska to host a 17th Century ball, the school opened in 1901, there is no 17th century heritage of the school, it’s imagined heritage that they are utilising. If the ball was a turn of the 20th century ball (the Edwardian fashion era in English parlance) that would make sense as an engagement with the schools heritage. This heritage may still be racially charged but not as racially charged as the imagined 17th Century heritage ball.

So why 17th C? Well I think the school is invested in training up nobility and royalty, individuals who do have heritage dating back to that period, who are likely to imagine that period as the golden era before the class system began to be (slightly) more equal. Hillerska despite having none of its own 17th C heritage is imagining heritage for its students to help maintain an increasingly shaky class and racial system that has it’s students at the top.

It’s therefore pretty significant that Simon is not in a 17th C costume. He has no 17th C noble heritage and unlike Sara (and Alexander, and Nils) is not interested in pretending that he does.

It is also interesting that Felice, who is on a journey of self acceptance and identity beyond her social climbing white family, only partially dresses in the pretence of 17th C noble glory.

Finally, it is interesting that Wille, desperately does not want to put this costume on, and is crying as he does so. He does not want this awful legacy, it keeps him from Simon and it makes him transform himself into something he doesn’t want to be.

#young royals#the show is about the class system#the show is about power#there is also a sprinkling of racial commentary#that I for one hope they increase#young royals analysis#this sprang to life as I was writing it#because I notice that Maddison had the white powder make up on and had a brainwave#Wilhelm#Simon#Felice#Sara

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

¡Navigatio Veneris!

Welcome to VenusofVolterra! While I may exhibit a clear bias for a certain pair of Volturi vamps, requests/ asks are open for all Twilight vamps.

This blog is primarily for character analysis, headcanons, and discussing Twilight from a historical lens!

Notes-On Series

Demetri Volturi

Sadism & Violence — Part Two

Medieval Navigation & Astronomy As It Pertains to Tracking

Other/Gen

Vampires and Beauty Standards

Costuming Notes & Observations

Where They Got Demetri Right - In Addition

From the Main Gallery in Volterra

A Young Man Named for Demeter, painted by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1594

Felix de Volturi, as painted by Orazio Gentileschi, C. early 17th century

Girl With Piercing Eyes, painted by Johannes Vermeer, 1663

Headcanons/ficlets/musings

Demetri Volturi

Demetri Participates in Organized Crime, for the Greater Good, of Course!

Demetri’s Pillow Talk Includes Poking Fun at the Cullens

Demetri Takes in Strays

The Picture

Demetri’s Room is a Mess

Demetri’s Ideal Vs. Real Mate

Demetri’s Messy Notebooks

Demetri Would be a Toxic Partner

Demetri and Platonic Bonds

On Demetri’s wife’s death

Felix Volturi

“Let’s Stay In Tonight, Little One”

Felix’s Mate is a Menace to Vases

Wife-Guy Felix

Felix is Goth - In Addition

Felix’s Psychology and Kinks

A Bit on Melissa, Felix’s Lover in Human Life

Heidi Volturi

Heidi and Rosalie Shouldn’t Meet the Same Beauty Standards

Heidi x Rosalie

Other/gen/multi-character

The Volturi & The Culinary Arts

Felix & Demetri: Renaissance Buddy Cops

Mate Bond HCs

Volturi Religion HCs

Demetri, Felix, & Toxic Relationships

Scene Packs

Felix Volturi Scene Pack

Demetri Volturi Scene Pack

Demetri Volturi/Charlie Bewley clips — Interview with the Volturi

Felix Volturi/ Daniel Cudmore — Interview with the Volturi

Demetri tells us what’s the issue with newborns

Historical Asks

Felix Volturi’s Human Life and Romantic/Sexual Preferences

Misc. Asks

Why is VenusofVolterra called VenusofVolterra?

How can any of the vampires be poc if venom sucks the pigment from their skin?/ Felix and Demetri may have been intended to be POC.

How would one even win Demetri’s heart if in the Twilight universe?

How I Make My Vampire Visualizations

How old are the Volturi?

What are the Guard’s Kinks?

Sexuality HCs for the Volturi

How the Volturi Works

Do the Volturi Care When They Hear Each Other Having Sex?

How Often Do Members of the Guard Have Sex?

Character tags

Demetri • Felix • Heidi • Jane • Alec • Aro • Caius • Marcus • Amun

Other tags to check out

Musings • Volturi playlist • historical twilight • vampire visualization

#PLEASE let me know if something here doesn’t work right#twilight#demetri volturi#the volturi#felix volturi#aro volturi#alec volturi#jane volturi#volturi#caius volturi#the twilight saga#amun twilight#twilight breaking dawn#twilight eclipse#masterlist

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your dolls are all from different materials, but do you have any opinions or interesting pieces of information on (historical) cloth dolls? Or alternatively, doll clothes? My main interest in dolls is sewing related, so these are the first two things I had on my mind

Okay, here's my favorite piece of info about doll clothes:

There's at least one type of garment that only survives in doll sizes. No examples for humans are known to still exist. Namely, the incredibly popular late 17th century fontange cap.

This is Lady Clapham, made c. 1680 and currently owned by the Victoria and Albert museum in London. See that ruffly thing on her head? That is a fontange cap. Easy to see why none of the real ones survive- that much lace would definitely be picked out of its configuration and reused when the fashions changed.

Even garments that do remain in Real People Scale often survive in greater numbers on dolls. Because, as with the fontange cap, the larger examples could be taken apart and reused. A doll's garment wouldn't have enough material to be worth the trouble- and dolls are inherently much gentler on their clothing than people, who have to move about, eat staining foods, walk through muddy streets, etc.

So with correct preservation, a doll's wardrobe could be a more complete representation of an era's fashion than some human-sized costume collections.

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🇹🇹🔥CAPTION THIS‼️🔥🇹🇹 @superstarriri #Vibes #WhenItHitsYouFeelNoPaim #CarnivalisLife #Queen #jamishness #WhenWeRollWeDontRollAlone #IwantToPumpWithPLANtnt Photo credit: @plan_tnt . 🤸Book Trinidad Carnival 2023 Now and Experience True Happiness!!🎉🇹🇹 #TrinidadCarnival2023 #bestfriendgoals #Party #TheGreatestShowOnEarth . STAY! PLAY! PUMP! With PLAN TnT! . We are pleased to offer you our packages which run for 5 Nights/6 Days (Friday 17th February - Wednesday 22nd February 2023) :- . A. Basic Trinidad 2023 Package includes: 1. Bed and Breakfast accommodation. 2. All-inclusive Monday and Tuesday Mas. 3. Fetes/parties. 4. All-inclusive J'Ouvert experience. 5. Liaison services (inclusive of costume & tickets collection) 6. Ground transportation to & from the airport and all PLAN TnT scheduled events. . B. Premium Trinidad 2023 Package includes: 1. Hotel accommodation at one of the best hotels within the Capital, Port of Spain. 2. All-inclusive Monday and Tuesday Mas. 3. Fetes/parties. 4. All-inclusive J'Ouvert experience. 5. Liaison services (inclusive of costume & tickets collection) 6. Ground transportation to & from the airport and all PLAN TnT scheduled events. . C. Jus Fete Trinidad 2023 Package (for those of you who already have accommodation; visitors & locals alike) which can include: 1. All-inclusive Monday and Tuesday Mas. 2. Fetes/parties. 3. All-inclusive J'Ouvert experience. 4. Liaison services (inclusive of costume & tickets collection) . 🇹🇹Book Trinidad Carnival 2023 now!🇹🇹 👉🏿It's always easier earlier!👍🏿 👉🏿Take advantage of easy monthly payments!👍🏿 👉🏿Visit www.plantnt.com👍🏿 #TrinidadCarnival #SocaMusic #StayPlayPump #Travel #Trinidad #Carnival #Caribbean #happy #soca #BookPlanTnt #BookPlanTnt2023 #PLANtnt #DifferentFlagsOnePeopleOneSoca #VisitTrinidad #VisitTrinidadAndTobago @visitlondon @nycgo @seetorontonow @wtmlondon @visitbarbados @tourismtt @ctotourism @tripadvisor @travelocity @expedia @kayak @hotwire @orbitz @trivago @forbes @trip @iflycaribbean @easterncaribbeanbreeze @essence (at Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago) https://www.instagram.com/p/CiLG5_VuCto/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#vibes#whenithitsyoufeelnopaim#carnivalislife#queen#jamishness#whenwerollwedontrollalone#iwanttopumpwithplantnt#trinidadcarnival2023#bestfriendgoals#party#thegreatestshowonearth#trinidadcarnival#socamusic#stayplaypump#travel#trinidad#carnival#caribbean#happy#soca#bookplantnt#bookplantnt2023#plantnt#differentflagsonepeopleonesoca#visittrinidad#visittrinidadandtobago

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Dodge James as Monsieur d'Artagnan at the Devonshire House Fancy Dress Ball, 1897

#devonshire ball#mdpcostume#historical costume#fancy dress#masquerade#19th c. britain#britain#mdptheatre#fete#17th c. costume#17th century

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

a 17th c. plague doctor costume i've been working on for the past few months! everything made by me except the mask, hat and shoes. the stays were made using the 1670s-1720s stays pattern from Reconstructing History, the petticoat is from a Simplicity pattern, eveything else was drafted by me. i'm wearing a bum roll for that nice silhouette 😎 excited to wear it to Elfia next month!

#costume#plague doctor#historical fashion#17th century#my sewing#wish me luck getting on public transport :')

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Becoming Elizabeth, 2022 Costume design by Bartholomew Cariss

Alicia von Rittberg as Elizabeth in Embroidered smock similar to a 17th Century smock in the V&A collection

English Smock, c.1615-1630 Linen embroidered with Silk in Stem Stitch

#embroidery#embroidery in film#needlework#costume design#embroidery on screen#film costume#costume#becoming Elizabeth#starz#Elizabeth I#tudor#tudor drama#tudor Costume#tudor fashion#alicia von rittberg

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patterning a 16th c. Irish léine sleeve

Mid-16th c. images of the léine from "Drawn after the Quick" and Codice de Trajes

The léine of 16th century Ireland had huge, iconic sleeves. Sadly, we have neither surviving examples of this garment, nor detailed period documentation, so we don't know how these sleeves were made. I have seen a couple different sewing patterns purposed, but none of these match the voluminous, gathered sleeves shown in the Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee. This is my attempt to create a sleeve pattern that better matches the surviving evidence.

The cut of léine sleeves probably varied across 16th c. Ireland, potentially impacted by factors like a person's wealth or where in Ireland they lived. It almost certainly changed over time as more of Ireland fell to English colonial conquest. The wearing of the large-sleeved léine was banned by King Henry VIII (McClintock 1943). Lucas de Heere’s circa 1575 illustrations show women with much smaller sleeves than earlier images. However, at least during the early part of the century, sleeves did not vary by gender. According to Laurent Vital, the only difference between a man's léine and a woman's léine was that the woman's had gores in the bottom it make it fuller (Vital 1518).

My goal with this project is to create a léine sleeve pattern for an early to mid-16th c. Irish person living outside of the Pale. Since none of the period images or texts are very detailed, I am combining information from several sources.

Englishman Edmund Campion who visited Ireland in 1569 gave the following derisive description of the léine: “Linnen shirts the rich doe weare for wantonnes and bravery, with wide hanging sleeves playted, thirtie yards are little enough for one of them” (Campion 1571).

Campion’s claim that the sleeves were pleated initially struck me as strange. English and continental European shirts from this period frequently had gathered sleeves (Mikhaila and Malcolm-Davies 2006, Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008), but pleating isn’t the same thing as gathering. However, other period writers made similar claims. Writing in 1596, Edmund Spenser mentioned "thicke foulded lynnen shirtes” as a garment worn by the Irish (Spencer 1633).

Similarly, Fynes Moryson described the léine as being made of “thirty or forty ells [of linen] in a shirt all gathered and wrinkled,” elsewhere he described it as “folded in wrinckles” (Moryson 1617).

In The Image of Irelande, John Derricke gave the following description of the léine:

Their shirtes be verie straunge,/ not reachyng paste the thie:/ With pleates on pleates thei pleated are,/ as thicke as pleates maie lye./ Whose sleves hang trailing doune/ almoste unto the Shoe (Derricke 1581)

Assuming that Derricke’s description is not just poetic license, I know of one 16th century construction method that matches the description “pleats on pleats [. . .] as thick as pleats may lie,” and that is cartridge pleating. Cartridge pleating is a technique that is more commonly used on thick fabrics like woolens, because a lot of fabric bulk is needed to keep the pleats standing properly, but extant 16th and early 17th c. neck ruffs use cartridge pleating to join massive lengths of fine linen to a neck band (Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008).

Cartridge pleating on a thick woolen fabric

A person unfamiliar with sewing methods and terms might well describe cartridge pleating as looking like folds, gathers, or wrinkles.

The léine sleeve patterns commonly used in modern reconstructions are completely flat, like a Japanese kimono sleeve with rounded corners. (There’s also a version which has a drawstring or gathering running along the top of the sleeve. This is a 20th c. Ren Fair invention which has no historical basis.)

The end-on views of the sleeve openings in the recently-discovered images from Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee clearly show that this is not correct. The rounded shape they show for the sleeve end can only be achieved through gathering.

Archer from the von Sternsee costume album and the O’Brien messenger from The Image of Irelande

The best illustration of a léine in The Image of Irelande, the messenger on plate 7, also provides evidence for a gathered sleeve. The way the fabric drapes in the middle of the sleeve suggests that the sleeve is gathered at both ends. Furthermore, the way the mass of a léine sleeve centers under the wearer’s arm when the wearer holds their arm out straight, like the O’Brien messenger, but hangs down like a trumpet when the wearer lowers their arm, like on von Sternsee’s archer also suggests that the sleeve is a symmetrical shape that is gathered at both ends and not a trumpet shape that is only gathered at the wrist end.

With these elements in mind, I went looking for a pattern which would create the correct shape. I used Jean Hunnisett's 15th c. bagpipe sleeve pattern from Period Costume for Stage and Screen and the sleeve pattern from this 1630s English waistcoat (published in Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns) as a starting point.

1630s waistcoat sleeve pattern

I replaced the curved sleeve heads in these patterns with the straight sleeve end and square underarm gusset typical of mid-16th-18th c. shirts, since the léine, like the shirt, is an unfitted linen garment, and because the straight edge is much easier to gather all the way around. I don't have any actual evidence for square gussets in 16th c. Ireland, but this pattern definitely needs an ungathered piece at the underarm. Anyone who is bothered by the lack of evidence can use a triangular gusset like the one on the 15th c. Moy gown instead.

After that, I experimented with mock-ups until I figured out how to get the correct proportions. I don't have any training in patterning or draping, so this took several tries. I used my 1/3 scale ball-jointed doll (24 inches tall) as model, because he required a lot less fabric and sewing. Since this was just a mock-up, I used random linen remnants from my stash, and I didn't bother to finish most of the edges.

Here is the final sleeve with the seams sewn together, but before doing the gathering:

This sleeve, on his right arm, is based on the gathered-wrist cuff version of the léine from Codice de Trajes, the von Sternsee album, and The Image of Irelande.

This sleeve ended up with me having to gather 31 inches of fabric into a 5-inch armscye. So yeah, cartridge pleating became necessary, because there is no way to make that kind of reduction work with regular gathering. I also had to do some smocking to get the giant mass of fabric better controlled before I could attach it to the body of the léine.

While this pattern might seem absurd, (it does call for a sleeve end wider than the wear is tall to be pleated into the armscye,) a close examination of John Michael Wright's 1680 portrait of Sir Neil O'Neill shows remarkably similar sleeves.

While this painting is from a century later than my target time period and the clothing clearly shows changes like the addition of English-style shirt sleeve ruffles, the shirt still has elements which I have seen no where else in late 17th c. fashion that are probably derived from earlier Irish dress.

The doublet worn over top prevents it from hanging down properly, but this shirt sleeve has the same bagpipe shape as the 16th c. léine. I have highlighted it in magenta to make this easier to see. The fine, regular folds near the top of the sleeve (highlighted in yellow) are probably the result of smocking or cartridge pleating, indicating that this sleeve, like my purposed pattern, has a large amount of fabric gathered or pleated to the armscye. The wrist end of the sleeve has 3 rows of smocking stitches sewn with silk thread, which shows that the sleeve cuff has a huge amount of fabric gathered into it.

Historically, silk was the thread of choice for smocking, because it is smoother and has greater tensile strength than wool, linen, or cotton. Several 16th c. sources note that the Irish used silk thread when making their léinte (Gresh 2021). Laurent Vital described Irish women as wearing, "chemises with wide sleeves, worked around the collar and in the seams with silk needlework of different colours" (1518). The presence of smocking on O'Neill's shirt combined with my experience trying to recreate this sleeve makes me think that at least some of that 16th c. silk needlework was smocking.

For the left sleeve of my mock-up, I tried to recreate the flatter sleeves from "Drawn After the Quicke". These sleeves do not have a gathered wristband.

This sleeve used basically the same pattern, but the lack of gathering at the wrist opening meant that the whole sleeve was slightly smaller, so I only had to pleat 26 in of fabric into the armscye instead of 31 in. This was just enough of a difference that I could set the sleeve without smocking it first, unlike the right sleeve. I guess this is the more budget-friendly option for your less wealthy kern.

I also made the curve at the bottom of the sleeve wider to give this one a more square shape.

Some of my failed experiments:

I would like to thank my friend Nikki for loaning me her smocking machine. This project would have been a much bigger pain if I had to do all those gathering stitches by hand.

Since this post has gotten rather long, I am putting the actual drafting instruction for this sleeve pattern in a separate post.

If anyone would like to support my work financially, I now have a ko-fi page.

Bibliography:

Arnold, Janet, Tiramani, J., & Levey, S. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4. Macmillan, London.

Campion, Edmund. (1571). A Historie of Ireland, Written in the Yeare 1571. Dublin. https://archive.org/details/historieofirelan00campuoft/historieofirelan00campuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

Derricke, John. (1581). The Image of Irelande, with the discoverie of a Woodkarne. John Daie, London. https://archive.org/details/imageofirelandew00derr/page/n29/mode/2up?view=theater

Hunnisett, Jean. (1996). Period Costume for Stage & Screen: Patterns for Women's Dress, Medieval-1500. Players Press, Inc, Studio City.

Gresh, Robert. (2021). The Saffron Shirt, Part 1: Saffron and Silk, Urine and Grease. Wilde Irish. https://www.wildeirishe.com/post/the-saffron-shirt-part-1-saffron-and-silk-urine-and-grease

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2008). The Invention of Drawstrings and Pleated Sleeves. Reconstructing History. https://reconstructinghistory.com/blogs/irish/the-invention-of-drawstrings-and-pleated-sleeves-1

Mikhaila, Ninya, & Malcolm-Davies, Jane (2006). The Tudor Tailor. Quite Specific Media Group, Ltd, London.

Moryson, Fynes. (1617). An Itinerary Containing His Ten Yeeres Travell through the Twelve Dominions of Germany, Bohmerland, Sweitzerland, Netherland, Denmarke, Poland, Italy, Turky, France, England, Scotland & Ireland. volume 4. https://ia801307.us.archive.org/16/items/fynesmorysons04moryuoft/fynesmorysons04moryuoft.pdf

North, Susan and Jenny Tiramani, eds. (2011). Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns, vol.1, V&A Publishing, London.

Spencer, Edmund. (1633). A View of the present State of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E500000-001/index.html

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#irish dress#dress history#leine#art#gaelic ireland#irish history#historical men's fashion#historical dress#historical women's fashion#sewing

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am a little bit obsessed with the 1600s men's pants that look like board shorts. Handbook of English Costume in the 17th Century by C. Willett Cunnington and Phillis Cunnington simply calls them "open breeches unconfined at the knee" and adds that "these somewhat resembled modern 'shorts' and were a Dutch fashion from 1585 and an English from 1600 to 1610 and again from 1640 to 1670's."

ſurf's upp!

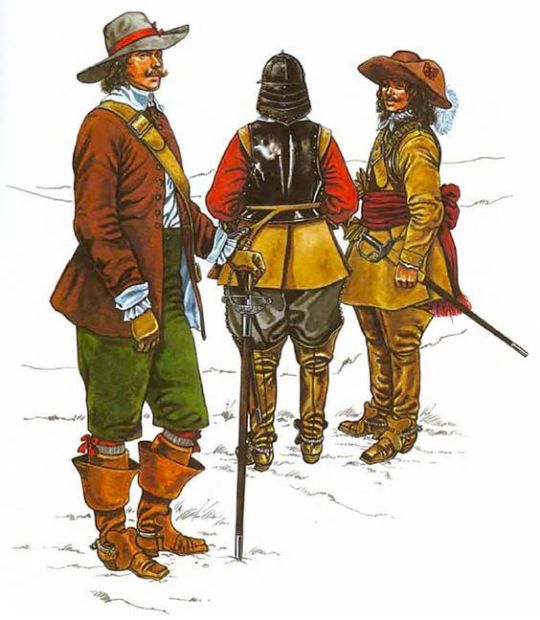

Of course cavaliers sometimes wore them; they're cool and sexy. The mid-1600s cavalier drawing by Nicolaes Pieterszoon Berchem has this type of breeches.

But I'm also finding them shown on the Parliamentary soldiers in the English Civil War?

Obviously these illustrations are from modern uniform reference books and might be questionable; but literally Cromwell himself is shown in breeches unconfined at the knee in a 1652 satire print (Rijksmuseum)!

I don't think this particular style of breeches has a necessarily foppish appearance (unless you put ribbons all over them), they can also be plain.

Here's a Puritan of 1649 in the Cunningtons' book, with the source given as "Reproduced in Planché 'Cyclopaedia of Costume.' (1876-9) vol. I, p. 109." He has the board shorts AND bucket-top boots? Anyway I am dying for more period illustrations and portraits showing this style.

#17th century#men's fashion#fashion history#historical men's fashion#english civil war#cavaliers#1600s board shorts

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

The actor Joseph Brady was born on October 9th 1928 in Glasgow.

One of a large Glaswegian working-class family, Brady spent five years in the Merchant Navy, before, encouraged by his sister, deciding to become an actor. In 1958, he graduated from the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama as “best comedy actor” and “most promising male actor”.

He was given a year’s contract at the Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre, and spent a year at Perth Theatre before joining the cast of the popular police drama Z Cars as PC Jock Weir.

Brady’s character, a rugby-playing Scot, was one half of the Z-Victor 1 team, with “Fancy” Smith (Brian Blessed). The series began with a newly formed group of uniformed officers, driving the then fashionable Ford Zephyrs and dealing with violence, robbery and domestic issues in “New Town”. During his time on the show Joseph recorded two songs by his fellow countryman Tommy Scott.

After leaving the police series in the late 1960s, he played the lead in the BBC’s 17th-century costume drama The Borderers, which ran for 26 episodes from 1969 to 1970. This gave him the opportunity to dye his hair red - and, enthusiastically, to learn to ride a horse.

After that, he alternated between stage and television. His television appearances included Dr Finlay’s Casebook, Taggart, The Bill The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, Casualty and Gramps in Rab C Nesbit

His Scottish theatre works mainly centred around Edinburgh’s Lyceum where he appeared in many productions, including Hadrian VII, The Taming Of The Shrew, and the epic Satire Of The Third Estates. In 1974, he joined very strong casts in Bill Bryden’s plays Benny Lynch and Willie Rough at the Lyceum. Other plays included The Bevellers, written by fellow Scot Roddy McMillan.

In 1985, he was in The Seagull, with Vanessa Redgrave, at the Haymarket, London and in 1988, he was in Billy Roche’s big success, A Handful Of Stars, at the Bush Theatre, west London. One of his favourite roles was that of the young boxer Joe Bonaparte’s father in the National Theatre’s 1984 production of Clifford Odets’s Golden

Joseph ‘Joe’ Brady died June 12th 2001 in London.

6 notes

·

View notes