#textual criticism

Text

Iliad proem but I used all the less likely readings

1 Μούσας ἀείδω και Ἀπόλλωνα κλυτότοξον,

ὅππως δὴ μῆνίς τε χόλος θ᾿ ἕλε Πηλείωνα

πολλὰς δ᾿ ἰφθίμους κεφαλας Ἄϊδι προΐαψεν

ἡρώων, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν

5 οἰωνοῖσί τε δαῖτα, Διὸς δ᾿ ἐτελείετο βουλῆι

ἐξ οὗ δὴ τὰ πρῶτα δια στητην, ἐρίσαντο,

Ἀτρεΐδης τε ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν καὶ δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς.

I sing of the Muses and Apollo of the golden bow,

how divine anger and hatred took hold of Peleus’ son,

and he sent to Hades many strong heads

of heroes and made them prey for dogs

and a banquet for the birds, and it was accomplished by Zeus' plan.

From the time when first they both stood away, they all quarreled:

the son of Atreus and godlike Akhilleus.

#tagamemnon#iliad#textual criticism#i actually think δαῖτα is the better reading/difficilior but it’s not in most editions so i used it here

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tuesday September 26th

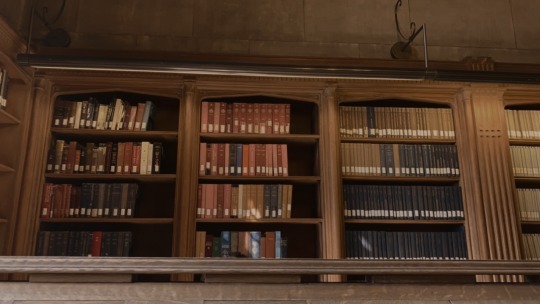

More library photos, as that is where I’m studying this afternoon. I still can’t get over how pretty my college library is. There are several other libraries on campus, but I haven’t yet explored any other than my own because this one is so lovely.

Had New Testament class this morning. I spent almost an hour afterwards talking with the professor about New Testament textual criticism. It was really fun.

I have class again this evening, so I will stay around the college. There’s not really much point in going home; especially since I get more done and less distracted when I’m on campus.

#aelstudies#studyblr#university#dark academia#university studyblr#dark acadamia aesthetic#academia aesthetic#study motivation#books#library#new testament#textual criticism#religious studies#biblical studies

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Paul Teaching an Imminent Eschatology in 1 Corinthians 15:51?

Eli Kittim

Some commentators have claimed that Paul’s language in 1 Corinthians 15:51 is referencing an imminent eschatology. Our primary task is to analyze what the critical Greek New Testament text actually says (not what we would like it to say), and then to ascertain if there are any proofs in it of an imminent eschatology. Let’s start by focusing on a particular verse that is often cited as proof of Paul’s imminent eschatology, namely, 1 Corinthians 15:51. It is alleged that this verse seems to suggest that Paul’s audience in Corinth would live to see the coming of Christ. But we must ask the question:

What in the original Greek text indicates that Paul is referring specifically to his immediate audience in Corinth and not to mankind collectively, which is in Christ? We can actually find out the answer to this question by studying the Greek text, which we will do in a moment.

At any rate, it is often asserted that the clause “We shall not all die" (in 1 Corinthians 15:51) does not square well with a future eschatology. These commentators often end up fabricating an entire fictional scenario that is not even mentioned in the original text. For starters, the plural pronoun “we” seems to be referring to the dead, not to people who are alive in Corinth (I will prove that in a moment). And yet, on the pretext of doing historical criticism, they usually go on to concoct a fictitious narrative (independently of what the text is saying) about how Paul is referring to the people of Corinth who will not die until they see the Parousia.

But, textually speaking, where does 1 Corinthians 15:51 mention the Corinthian audience, the Parousia, or that the Corinthians will still be alive to see it? They have rewritten a novel. None of these fictitious premises can be found in the textual data. Once again, I must ask the same question:

What in the original Greek text indicates that Paul is referring to his audience (which is alive) in Corinth and not to the dead in Christ (collectively)?

We can actually find out the answer to this question by studying the Greek text, which we will do right now!

As I will demonstrate, this particular example does not prove an imminent eschatology based on Paul’s words and phrases. In first Corinthians 15:51, the use of the first person plural pronoun “we” obviously includes Paul by virtue of the fact that he, too, will one day die and rise again. In fact, there is no explicit reference to the rapture or the resurrection taking place in Paul’s lifetime in 1 Corinthians 15:51. In the remainder of this commentary, I will demonstrate the internal evidence (textual evidence) by parsing and exegeting the original Greek New Testament text!

Commentators often claim that the clause “We shall not all die" implies an imminent eschatology. Let’s test that hypothesis. Paul actually wrote the following in 1 Corinthians 15:51 (according to the Greek NT critical text NA28):

πάντες οὐ κοιμηθησόμεθα, πάντες δὲ

ἀλλαγησόμεθα.

My Translation:

“We will not all sleep, but we will all be

transformed.”

In the original Greek text, there is no separate word that corresponds to the plural pronoun “we.” Rather, we get that pronoun from the case endings -μεθα (i.e. κοιμηθησόμεθα/ἀλλαγησόμεθα). The Greek verb κοιμηθησόμεθα (sleep) is a future passive indicative, first person plural. It simply refers to a future event. But it does not tell us when it will occur (i.e. whether in the near or distant future). We can only determine that by comparing other writings by Paul and the eschatological verbiage that he employs in his other epistles. Moreover, it is important to note that the verb κοιμηθησόμεθα simply refers to a collective sleep. It does not refer to any readers in Corinth!

Similarly, the verb ἀλλαγησόμεθα (we will all be transformed) is a future passive indicative, first person plural. It, too, means that all the dead who are in Christ, including Paul, will not die but be changed/transformed. The event is set in the future, but a specific timeline is not explicitly or implicitly given, or even suggested. Both expressions (i.e. κοιμηθησόμεθα/ἀλλαγησόμεθα) refer to all humankind in Christ or to all the elect that ever lived (including, of course, Paul as well) because both words are preceded by the adjective πάντες, which means “all.” In other words, Paul references “all” the elect that have ever lived, including himself, and says that we will not all perish but be transformed. We must bear in mind that the word πάντες means “all,” and the verb “we will all be changed” (ἀλλαγησόμεθα) refers back to all who sleep in Christ (πάντες κοιμηθησόμεθα). Thus, the pronoun “we,” which is present in the case endings (-μεθα), is simply an extension of the lexical form pertaining to those who sleep (κοιμηθησόμεθα). So, the verb κοιμηθησόμεθα simply refers to all those who sleep. Once again, the adjective πάντες (all/everyone)——in the phrase “We will not all sleep”—— does not refer to any readers in Corinth.

There is not even one reference to a specific time-period in this verse (i.e. when it will happen). Not one. And the plural pronoun “we” specifically refers to all the dead in Christ (πάντες κοιμηθησόμεθα), not to any readers alive in Corinth (eisegesis).

And that is a scholarly exegesis of how we go about translating the meanings of words accurately, while maintaining literal fidelity. It’s also an illustration of why we need to go back to the original Greek text rather than to rely on corrupt, paraphrased English translations (which often include the translators’ theological interpretative biases).

Conclusion

What commentators often fail to realize is that the first person plural pronoun “we” includes Paul because he, too, is part of the elect who will also die and one day rise again. Koine Greek——the language in which Paul wrote his epistles——is interested in the so-called “aspect” (how), not in the “time” (when), of an event. First Corinthians 15:51 does not suggest specifically when the rapture & the resurrection will happen. And it strongly suggests that the plural pronoun “we” is referring to the dead, not to the readers who, by contrast, are alive in Corinth.

Some commentators are simply trying to force their own interpretation that doesn’t actually square well with the grammatical elements of 1 Corinthians 15:51 or with Paul’s other epistles where he explicitly talks about the Day of the Lord (2 Thessalonians 2:1-12) and the last days (1 Timothy 4:1; 2 Timothy 3:1 ἐν ἐσχάταις ἡμέραις), a time during which the world will look very different from his own. The argument, therefore, that 1 Corinthians 15:51 is referring to an Imminent Eschatology is not supported by the textual data (or the original Greek text).

What is more, if we compare the Pauline corpus with the eschatology of Matthew 24 & 2 Peter 3:10, as well as with the totality of scripture (canonical context), it will become quite obvious that all these texts are talking about the distant future!

If anyone thinks that they can parse the Greek and demonstrate a specific time-period indicated in 1 Corinthians 15:51, or that the phrase “all who sleep” (πάντες κοιμηθησόμεθα) is a reference to the readers in Corinth, please do so. I would love to hear it. Otherwise, this study is incontestable/irrefutable!

The same type of exegesis can be equally applied to 1 Thessalonians 4:15 in order to demonstrate that the verse is not referring to Paul’s audience in Thessalonica, but rather to a future generation that will be alive during the coming of the Lord (but that's another topic for another day):

ἡμεῖς οἱ ζῶντες οἱ περιλειπόμενοι εἰς τὴν

παρουσίαν τοῦ κυρίου.

“we who are alive, who are left until the

coming of the Lord.”

If that were the case——that is, if the New Testament was teaching that the first century Christians would live to see the day of the lord——it would mean that both Paul and Jesus were false prophets who preached an imminent eschatology that never happened.

#1Corinthians15v51#1Thessalonians4v15#imminent eschatology#preterism#realized eschatology#the little book of revelation#koineGreek#PaulineCorpus#historicalcriticism#parousia#historicalgrammaticalmethod#futurism#paul the apostle#Τομικροβιβλιοτηςαποκαλυψης#futureeschatology#resurrection#Biblicaleschatology#bible prophecy#textual criticism#KoineGreekgrammar#inauguratedeschatology#rapture#parsingkoineGreek#EK#last days#day of the lord#eschaton#bible study#ελκιτίμ#elkittim

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

New gospel of Matthew just dropped before winds of winter

#syriac#syriac gospels#winds of winter#new testament#matthew#gospel of matthew#textual criticism#greek#language#scholarship#bible#christian#atheist

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

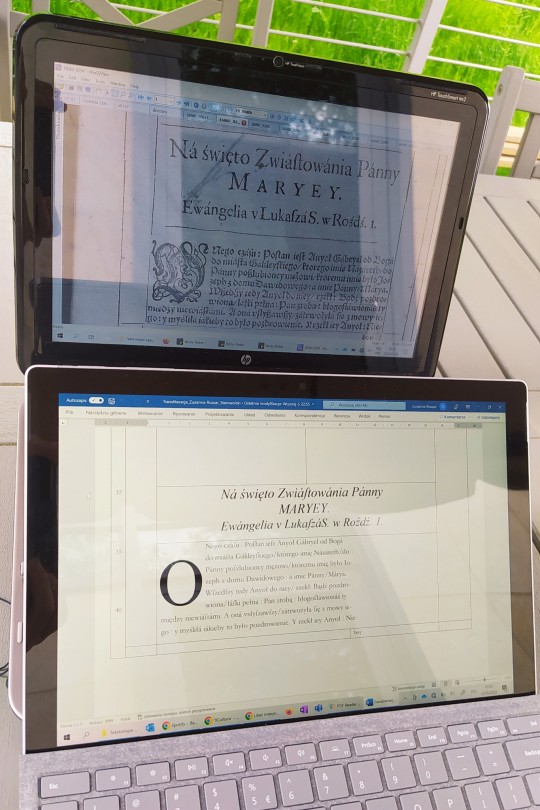

Textual criticism is very interesting, but it sure is a lot of work! (and also knowledge...)

On Friday, we had a free day so I went to the library. If it weren't for the very high temperature combined with lack or a very low-level air conditioning, I think I would've transcribed the whole text that day. As it was, I've managed to do around 80% during five hours there, and then decided I'm done for the day. I finished the rest yesterday evening, and today I'm once again going through everything to make sure I don't leave any mistakes. (I've already found too many for my liking). There are a couple of questions to my professor to be asked tomorrow and then I think I can send the file to my examinator.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

"As one playful formulation has it, rather than being straightforwardly 'about' something in particular, every text is inevitably surrounded by a 'vibrating aboutness cluster'. The context, content and range of that cluster must be accounted for as part of an analysis.

Some writers in some situations may strain against rhetorical shenanigans, for example striving for the specificity of logical notation: the cluster of reasonable meanings of such texts may well thus be less diffuse than for those which, say, revel in pun and performance.

But a text with one 'true' meaning is a chimera. Analysis is not closure, but an attempt to discern reasonable meaning(s) close to the core of that cluster, and to contest those that range too far from it."

- China Miéville, from A Spectre, Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto, 2022.

#china miéville#quote#quotations#textual criticism#academia#textual analysis#classics studies#meaning#critical thinking#literature#sunyata

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This idea that everything goes around The Text as a fixed point and, God forbid, one wants to research other possible sources or investigate the background on which such Text comes into creation or the author’s set up/implied knowledge/references/echoes and will ... because that’s not the Text itself!!!11!!! and removing the ever fascinating question of “What should be included in the text?” “Who is the Author?” “What is the text?” which is the reason why people got curious about literature in the first place and it’s always a question and never a fixed answer ... you don’t have to become like a walking, boring, neverending human version of a French genetic edition, but ffs! Expand your horizons a bit!

#textual criticism#literature#in other news i'm over the bullshit tumblerinas' way of understanding the death of the author thing#gorlies that's not it#meta

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Bruce Metzger, one of the world's leading authorities on New Testament textual criticism, states that not one doctrine of the church is in jeopardy because of a variant reading in the New Testament.

Mark Pickering, Peter Saunders

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

An introduction to textual criticism, illustrated by the stemma of the manuscripts of Herodotus’ Histories

“Textual criticism

Textual criticism: the study of medieval manuscripts in order to reconstruct ancient texts.

Ancient sources have been passed down to us in medieval manuscripts, which were copied manually. Unfortunately, it is impossible for humans to copy a long text without making errors, which means that our manuscripts are imperfect. The Italian scholar Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494, “Politian”) was the first to realize that if you looked carefully at the errors in existing manuscripts, you might reconstruct a lost original. His own discovery was that all manuscripts of Valerius Flaccus’ Argonautica had been derived from the same book, which had contained several pages in the wrong sequence. All manuscripts contained the same error, proving that it had been in the original text (“archetype”).

This was the beginning of what is now called “textual criticism”. Modern editions of ancient texts always have a list of the manuscripts and a history of the way in which the text has been passed down, the “tradition”. Usually, there’s also a family tree (“stemma”) of the available and reconstructed manuscripts. If there are many texts, classicists can even recognize families that go back to different archetypes, which can be used to reconstruct an archetype behind the archetypes. Here is an example, based on the manuscripts of Herodotus' Histories. There are, in fact, forty-six manuscripts, but most of them can be eliminated, leaving only seven relevant manuscripts, called A, B, C, D, R, S, and V.

In this stemma, manuscripts A, B, and C are related to each other, because they are based on the same manuscript, which is lost but can be reconstructed. It is indicated as [a]. Something similar can be said of R, S, and V, which are derived from [r]. These are two families. Comparison of D and [r] helps us reconstruct [d], which in turn can be compared to [a]. In this way, we can make a reconstruction of the archetype, [x]. All known manuscripts are based on this archetype, which does not mean that this is the original text, as written by Herodotus himself. However, [x] comes closer to the original than any of the existing manuscripts.

A modern edition of an ancient text usually has a "critical apparatus". An example can be seen in the picture: the prologue of the Gospel of John. The main text is the best reconstruction the editors could make, and at the foot of the page, you can see variant readings. In the column to the right, you can see references to related Biblical texts.

A real scholar is, of course, satisfied only if there is independent proof that this method is correct. Fortunately, this exists. Among the papyri discovered in the Egyptian desert, texts have been discovered that were identical to reconstructions that had been made much earlier. It is, of course, only a small test, but it sufficient to prove that the principles of reconstruction are sound.

Politian was the first to realize the potential and later classicists have improved this method. His younger contemporary Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) introduced the rule known as lectio difficicilior potior. Another improvement was the recognition of “horizontal tradition”, which takes place when a copyist uses more than one manuscript to make his own text. In its simplest form, he copied one text and inserted variants of the second text in the margin of his book. This is of course easy to recognize, but things can be quite difficult when the copyist, on every occasion, chose the variant he thought best, now preferring the first and then the second text.

Textual criticism has been increasingly refined and the results have become progressively better. In its present form, it was proposed by the Swedish jurist Carl Johan Schlyter (1795-1888). It was so enthusiastically propagated by the German classicist Karl Lachmann (1793-1851), that it often called the Lachmann Method. It was the model for the biological theory that humans and monkeys have the same ancestor; in other words, modern evolutionism is inspired by textual criticism.

This page was created in 2014; last modified on 12 October 2020.”

Source: https://www.livius.org/articles/theory/textual-criticism/

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

#God#Christ#Jesus#Bible#religion#Christianity#forgiveness#repentance#redemption#Codex Sinaiticus#St. Catherine's Monastery#Tischendorf#Mt. Sinai#textual criticism#ancient manuscript#3rd century#4th century

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Believe, or Not (Mark 16:9-18)

There are some who may search for evidence their entire lives, never to find it, because they want confirmation by means of their own mentally contrived and culturally conditioned constructs.

The risen Jesus appears to his disciples, by Unknown Italian artist, 1476

[Note: The earliest manuscripts and some other ancient witnesses do not have verses 9–20.]

When Jesus rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had driven seven demons. She went and told those who had been with him and who were mourning and weeping. When they heard that…

View On WordPress

#belief#believe#bible#christ&039;s disciples#christ&039;s resurrection#christian belief#christian disciples#christian discipleship#christian life#christianity#eastertide#epistemology#gospel of mark#holy bible#holy scripture#jesus christ#mark 16#resurrection#risen christ#risen lord#textual criticism#unbelief

0 notes

Text

Book Review: A New Literary History Of America

A New Literary History Of America, edited by Reil Marcus and Werner Sollors

Does this book need to exist? This is a weighty question to ask of a weighty book that is about 1050 pages long or so. There is no doubt that this book does exist, much to my own disappointment when I was slogging my way through it, but does it need to exist? There are several ways to answer this question. One way is to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Historicity of Jesus Christ's Crucifixion - James Bishop - Revisited and Updated

For many the crucifixion of Jesus Christ is one of the most widely known things about his life. However, what are the historical reasons and evidences for accepting it as a genuine fact of history?

There are two links for this particular post, a longer, well documented link and a shorter summary overview link.

The well documented link is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

🔥 Was the Septuagint Destroyed When the Library of Alexandria Was Burnt Down in 48 BC❓🔥

By Author Eli Kittim 🎓

The Argument

Some people (typically Jewish apologists) claim that the Septuagint doesn’t exist because it was destroyed when the Library of Alexandria was burnt down in 48 BC.

This conclusion, however, is both textually misleading & historically erroneous.

First

The Alexandrian Library and its collection were not entirely destroyed. We have evidence that there was only partial damage and that many of its works survived. According to Wiki:

The Library, or part of its collection, was

accidentally burned by Julius Caesar during

his civil war in 48 BC, but it is unclear how

much was actually destroyed and it seems

to have either survived or been rebuilt

shortly thereafter; the geographer Strabo

mentions having visited the Mouseion in

around 20 BC and the prodigious scholarly

output of Didymus Chalcenterus in

Alexandria from this period indicates that

he had access to at least some of the

Library's resources.

Second

The Septuagint had already been written and disseminated among the diaspora since the 3rd century BC, and so many of its extant copies were not housed in the Library of Alexandria per se.

Third

Textual Criticism confirms that the New Testament authors used the Septuagint predominantly and quoted extensively from it. If the Septuagint didn’t exist, where did the New Testament authors copy from? And how do you explain the fact that the New Testament and the Septuagint often have identical wording in their agreements?

Fourth

The Dead Sea Scrolls also demonstrate that the Septuagint was far more accurate than the 10th-century-AD Masoretic text. See, for example, the textual controversy surrounding Deuteronomy 32:8. Both the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Septuagint have “sons of God.” The Masoretic text is demonstrably inaccurate because it has “sons of Israel,” a later redaction. Israel didn’t even exist at that time!

Fifth

Emanuel Tov, a leading authority on the Septuagint who has explained the various textual families (or text-types) of the Old Testament, never once mentioned that we lost the Septuagint, or that it was destroyed, or that it was no longer in circulation. On the contrary, he claims that it continued to be in use during the Christian period and that it is much more older than the 10th-century-AD Masoretic text, which the Jews call the “Hebrew Bible.”

Sixth

If the Septuagint was completely destroyed, as some have erroneously suggested, from where were the later revisionists and translators copying from? We have historical evidence that they were, in fact, copying from the Septuagint itself. Wiki writes:

Theodotion … was a Hellenistic Jewish

scholar, … who in c. 150 CE translated the

Hebrew Bible into Greek. … Whether he was

revising the Septuagint, or was working

from Hebrew manuscripts that represented

a parallel tradition that has not survived, is

debated.

So there’s evidence to suggest that the Theodotion version is a possible *revision* of the Septuagint. This demonstrates that the Septuagint existed in the second century AD! Otherwise, where was Theodotion copying from if the Septuagint didn’t exist?

Seventh

The great work of Origen, Hexapla, compiled sometime before 240 AD, is further proof that the Septuagint was still in use in the 3rd century AD! Wikipedia notes the following:

Hexapla … is the term for a critical edition

of the Hebrew Bible in six versions, four of

them translated into Greek, preserved only

in fragments. It was an immense and

complex word-for-word comparison of the

original Hebrew Scriptures with the Greek

Septuagint translation and with other Greek

translations.

Encyclopedia Britannica adds:

In his Hexapla (“Sixfold”), he [Origen]

presented in parallel vertical columns the

Hebrew text, the same in Greek letters, and

the versions of Aquila, Symmachus, the

Septuagint, and Theodotion, in that order.

Eighth

Besides Origen’s Hexapla, we also have extant copies of the Septuagint. According to wiki:

Relatively-complete manuscripts of the

Septuagint postdate the Hexaplar

recension, and include the fourth-century-

CE Codex Vaticanus and the fifth-century

Codex Alexandrinus. These are the oldest-

surviving nearly-complete manuscripts of

the Old Testament in any language; the

oldest extant complete Hebrew texts date

to about 600 years later, from the first half

of the 10th century.

Ninth

There’s also historical and literary evidence that the Greek Septuagint was in wide use during the Christian period and beyond. Wiki says:

Greek scriptures were in wide use during

the Second Temple period, because few

people could read Hebrew at that time. The

text of the Greek Old Testament is quoted

more often than the original Hebrew Bible

text in the Greek New Testament

(particularly the Pauline epistles) by the

Apostolic Fathers, and later by the Greek

Church Fathers.

Tenth

Today, Biblical scholarship has a *critical edition* of the Septuagint. If it was destroyed in 48 BC, where did the critical edition come from? The Göttingen Septuaginta (editio maior) presents *a fully critical text* and should silence the skeptics and critics who try to mislead the public. They deliberately mislead the public by trying to discredit the far more reliable and much older Septuagint in order to get people to accept the much later Hebrew Masoretic text from the Middle Ages❗️

#lxx#septuagint#Library of Alexandria#Strabo#textual criticism#Masoretic#EliKittim#NewTestamentGreek#dead sea scrolls#Deuteronomy32v8#EmanuelTov#SBL#Theodotion#the little book of revelation#HebrewScriptures#origen#Hexapla#aquila#julius caesar#IOSCS#Symmachus#ελικιτίμ#GreekOldTestament#critical edition#ΜετάφρασητωνΕβδομήκοντα#biblicalgreek#GöttingenSeptuaginta#τομικρόβιβλίοτηςαποκάλυψης#ΕλληνιστικήΚοινή#ΑγίαΓραφή

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is the primary sacred text of Judaism?

There are 24 books Judaism claims as its holy writings. They are the five books which tell of the origin of the Israelites and discuss the laws their God gave to them, the Torah (law); eight books written by or about the prophets of ancient Israel, the Neviʾim (prophets); and eleven books which contain wisdom and miscellaneous aspects of Israelite history, the Ketuvim (writings). Altogether, these books comprise the Tanakh.

The Christian Old Testament as used by Protestants has the exact same content as the Tanakh, but arranges the constituent books differently and usually splits the books of Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah into two each, and the book of the minor prophets into twelve. Jews are generally uncomfortable with this name, as it implies that the Tanakh is complete without the New Testament, along with different misconceptions on how Christians have translated and presented the Tanakh, discussed below. For the rest of this FAQ, this set of books will be referred to as the Tanakh except in its capacity of a constituent part of the Christian Bible.

Non-Protestant Christians include a number of books written during the Second Temple era or later in their Old Testament canons. These books are collectively known as the Apocrypha or Deutercanon, and are outside the scope of this FAQ.

What language(s) was the Tanakh written in?

Almost the entire Tanakh was written in Hebrew, while parts of the Daniel and Ezra(-Nehemiah), along with words and phrases from throughout the Tanakh, were written in Aramaic.

Was Biblical Hebrew written with vowels?

The Tanakh was originally written in a writing system called the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and other very early examples of Hebrew writing, and retained by the Samaritans. During the time of the Second Temple, the Jews gradually adopted a script derived from the Imperial Aramaic script, and modified it to become the square script, which is now the more familiar "Hebrew script." Both were ultimately derived from the Phoenician alphabet, and operate on similar principles, to the point where there is essentially a one-to-one correspondence. They are both technically defined as abjads rather than proper alphabets, the reason being that they lack letters whose primary use is to express vowel sounds.

Why wasn't Biblical Hebrew written using a system that clearly marked vowels?

Hebrew is a member of a larger family called the Semitic languages, most of which do not have (or did not use to have) many distinct vowels. Arabic only has three, and there is no strong evidence that Akkadian had more than four. Aramaic, Ge'ez and Amharic all have at least five, and there is evidence that Ugaritic did as well, but the additional vowels in these languages do not converge the way they would if they had been inherited from a common ancestor.

At the beginning of its written history, a predecessor of Hebrew, either Proto-Northwest Semitic or an immediate descendant, likely had three vowel qualities /a i u/. Its writing system, the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, accordingly lacked vowel letters, as a given consonant sequence would have been substantially less ambiguous than in other languages with larger vowel inventories.

In the stages between PNWS and Hebrew, and in Hebrew itself, a number of different sound changes caused its vowel inventory to expand, ultimately adding two, possibly three, more vowel sounds /e o (ǝ)/. As Hebrew developed, so did the variant of the Proto-Sinaitic script used to write it, albeit more slowly, giving rise to both the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet and the square script. As the written forms of a language are more conservative than their spoken forms, and the changes which brought about these additional vowels were very gradual, there was no impetus for any group of scholars to sit down and propose the addition of vowel letters to be used in writing Hebrew before it went extinct around the beginning of the fourth century.

That being said, four letters, alpeh א, waw ו, he ה, and yodh י, used ordinarily to express consonants /ʔ w~v h j/, took on a secondary role of expressing vowels in variant spellings. The letters aleph and he were used for essentially any vowels, waw for rounded vowels, and yod for front vowels. In this capacity, such a letter is called an ʾem qriʾa or mater lectionis.

How do we determine the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew if it is extinct and did not have proper vowel letters?

Hebraicists rely on a number of different methods for determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew words. Even though Hebrew went extinct, it was retained liturgically in Judaism, leading to three different vocalizations, the Tiberian, Babylonian, and Palestinian. During the high middle ages, a group of Jewish scholars called the Masoretes developed systems of vowel markings called the niqqud to clarify these vocalizations in Hebrew writing. Only the Tiberian vocalization survived the middle ages or was extensively covered by niqqud, and it is referenced when determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew.

The matries lectionis produced variant spellings of certain words, which also clarifies the pronunciation.

In ancient times, a Greek translation of the Tanakh was produced called the Septuagint (abbreviated LXX). Its origins are shrouded in fable, but it is generally agreed by historians of the Bible that in the mid-third century BC, about seventy rabbis gathered in Alexandria and translated at least the Torah into Hebrew, with the rest of the Old Testament completed by the first century. As Greek is written in a proper alphabet, the vowels used in proper nouns and loanwords give insight into how these words would have been pronounced in Hebrew.

Around the middle of the third century AD, a critical edition of the Tanakh called the Hexapla was produced. Consisting of six columns, it placed the Hebrew text alongside an attempt to write the Hebrew text with the Greek alphabet (in the second column, this text is called the Secunda), and four different Greek translations. Though it exists in fragmentary condition, the Secunda gives some insights into the pronunciation of Hebrew.

Syllable timing can be predicted based on Biblical poetry.

Finally, as it is part of a larger language family, Hebrew can be compared with other Semitic languages that have been spoken constantly since antiquity. Special emphasis is put on comparison to its closest living relatives, Aramaic and Arabic.

What is the Tetragrammaton?

It is a name for God used well over 6000 times in the Tanakh, spelled using four Hebrew letters, יהוה.

Have any of the above methods been useful in determining the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton?

Judaism developed a taboo against pronouncing the Tetragrammaton during the Second Temple Period. For this reason, except for one possible exception (and even that is doubtful), no LXX manuscript presents a genuine effort to transliterate the Tetragrammaton; the only remaining fragments of the Secunda which include sections featuring the Tetragrammaton replace it with the Hebrew form amidst the Greek letters; and Tiberian vocalization lacks a pronunciation for it. In addition, all four of its letters can be matries lectionis, and it lacks known cognates in other Semitic languages.

Samaritanism developed the taboo later, and a group of Jewish mystics that survived a century or so after the destruction of the Second Temple never had it. In the fourth century, Theodoret, in his Quaestiones in Exodum, records a Samaritan pronunciation of /i.a.ve/, consistent with Clement of Alexandria recording a mystic pronunciation of /i.a.we/ in the fifth book of his Stromata. Since /v/ and /w/ were never distinguished readily in any form of Hebrew, this points to a pronunciation /jah.weh/, hence the spelling Yahweh.

The name "Jehovah" was an earlier rendering of the name, produced from a misconception among Christian Hebraists when encountering the Tetragrammaton in Masoretic texts. To prevent anyone from even accidentally saying the name aloud, a practice arose of saying it with the vowels in the word for "Lord," אדוני adonai. Christian Hebraicists did not realize this was a hybrid word and thought it was God's actual name, producing /ja.ho.vah/, eventually Jehovah.

Is Lashawan Qadash as promoted by various Black Hebrew Israelite groups remotely authentic to the actual pronunciation of ancient Hebrew?

As with almost all other particular teachings of the BHIs, the Lashawan Qadash lacks any kind of historical evidence and is easily disproven.

For example, under LQ, the name of God is not "Elohim," but rather "Alahayam." However, the first element is cognate with Arabic إله /ʔi.laːh/ and is an element of a mile-long list of different theophoric names from the Tanakh, such as Elijah, Daniel, etc, consistently spelled ηλ /eːl/ in the LXX. This points to a front vowel, both long before Hebrew became a distinct language, and towards its extinction. The second vowel is confirmed by the spelling variant which includes a waw, indicating a rounded vowel. However, the BHIs who employ LQ do not use a variant "Alahawayam." The word itself is the plural of the word "eloah" (please note that verbs always indicate grammatical number in Hebrew, and that the actions of the God of Israel are described using singular verbs in the Tanakh) which has always had a letter waw. The same plural ending shows a consistency with vowels in Aramaic plural endings. The pronunciation of the entire word is consistent with the form ελωειμ as found in the Secunda for Psalm 72:18. Black Hebrew Israelitism is usually conspiratorial, and BHIs will suggest the pronunciations of Hebrew proposed through accepted methods of historical methods are actually some kind of wicked plot perpetrated by the Jesuits, Masoretes, adherents of Babylonian mystery religion, or some combination thereof, usually in cahoots with each other. Whatever shadowy force(s) which acted to produce the pronunciation "Elohim" would have had to alter every last Hebrew scroll and carving which contains the singular "eloah," waw in tow, and every last Septuagint and New Testament manuscript containing a theophoric name containing "El" to include the letter ēta, including those manuscripts which laid in dark caves and buried in the desert for centuries; every remaining Secunda fragment to spell the name as ελωειμ; convinced millions of Arabic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to say "ilah" and write accordingly; and convinced millioned of Aramaic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to use front vowels when saying nouns in the plural, and write accordingly, centuries before anyone seriously proposed that Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew were related languages. This is all that would have had to have been done just to deceive the whole world of the pronunciation of just one word. There are far more words which also present a host of problems under LQ.

The existing evidence suggests that LQ originated in 20th-century Harlem, without any historical precedent whatsoever, and does not belong in any serious discussion of Biblical Hebrew.

Why is it said that Hebrew "went extinct" when it has been in constant use by the Jews until the present day?

The term "extinction" in linguistics is used of languages without living native speakers. When the last native speaker of a language dies, that language is then extinct. Sumerian is extinct. Ancient Egyptian is extinct. Gaulish is extinct. Wampanoag is extinct. Ubykh is extinct. No informed person disputes any of these languages are actually extinct. However, many Jews and philosemites take offense at the term "extinction" when used to describe the ultimate fate of Biblical Hebrew.

The fact of the matter is that Assyria dispersed most of the tribes of Israel, and Babylon captured what was left. We do not know what happened to the 10 lost tribes, but the members of Judah and Levi began to speak Aramaic. Even after Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to resettle Judaea, most Jews continued to speak Aramaic and teach it to their children. Through the Second Temple Era, Hebrew went from threatened to endangered. It did not matter that Hebrew was used in the synagogues; whether a language is alive or dead is determined at the cradle rather than the altar.

Bar Kochba attempted to reinvigorate Hebrew during his revolt around AD 130. After this revolt was suppressed by the Romans, any hope of Hebrew continuing were essentially dashed. The Mishnah, thought to have been among the final documents written in Hebrew during the lifetime of any native speakers, was completed around the turn of the third century, and was in a form that showed obvious changes one would expect of a language approaching extinction. There is not a shred of evidence that there were any native speakers more than a century after the Mishnah.

Extinct languages find use liturgically in different religious traditions throughout the world. No Jewish person or philosemite would deny, given sufficient information, that Avestan is extinct, despite its continuing use in Zoroastrianism. Nor would they deny the same about Coptic, Latin, Ge'ez, or Sanskrit, nor would they deny that Sumerian was in use by various pagan groups as long as 2000 years after it went extinct. Yet, for these same people, it is "inaccurate" or even "bigoted" to suggest the same regarding Hebrew. The knowledge of Hebrew during late antiquity and the middle ages was restricted almost exclusively to rabbis and Jewish literati, exactly 100% of whom spoke some other language natively. Yes, Hebrew was revived during the modern period, but it took great effort in creating enough vocabulary to describe the modern world, and there are enough difference between modern and Biblical Hebrew to motivate Avraham Ahuvya to create a modern Hebrew translation (for lack of a better term) of the Tanakh.

Simply put, if these people want to discuss historical linguistics, they need to use terms which are found in historical linguistics, as they are defined by historical linguistics, terms which specialists in the field, Jew and gentile, accepted a long time ago. This includes the term “extinction.”

Why don't Christians use Hebrew source texts when translating the Tanakh?

They do, and have been doing so constantly since the Reformation.

The printed Hebrew edition of the Tanakh, by Daniel Bomberg, was arranged from several Masoretic manuscripts collected and collated by Jacob ben Hayyim. This was the primary base text of the Old Testament in all Protestant English translations of the Bible from at least the Geneva Bible (first published 1557) up until at least the Revised Version (published 1885), and seemingly the Darby Bible of 1890 and American Standard Version of 1901. Only Catholic Bibles used the Vulgate as a source, and an obscure translation of the LXX by Charles Thompson was printed in 1808; this translation made its source clear on the title page, not that almost anyone paid attention to it.

A scholar of the Tanakh named Rudolph Kittel collated an even greater set of Masoretic manuscripts, creating the Biblia Hebraica Kittel (BHK), first published 1906. Later, it was determined that a manuscript, which had been produced in Cairo, mysteriously ended in the possession of a Russian Jewish collector named Abraham Firkovich, was displayed in Odessa, and then later in St. Petersburg (later Leningrad) was in fact the oldest complete copy of the Tanakh in Hebrew. It is now known as the Westminster-Leningrad Codex, and was made the primary source of printings of the BHK from 1937 onward, and by extension the OT of the Revised Standard Version. It later became the primary basis of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), first published 1968, and by extension the OT in the New American Standard Bible, New International Version, Good News Bible, New RSV, New KJV, Contemporary English Version, World English Bible, English Standard Version, and New Living Translation, just to name a few. Another printed edition of the Old Testament in Hebrew, the Biblia Hebraica Quinta, was completed last year, also derived from the WLC, and there is no reason to believe it will not serve as the basis of future translations.

The LXX, Targumim, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Samaritan Pentateuch are occasionally consulted, mostly to illuminate the meaning of obscure Hebrew words or phrases, or solve inconsistencies among Masoretic manuscripts. The translators invariably place conspicuous footnotes to indicate such. If you do not believe Jewish translators of the Tanakh do the same thing, you need to explain how “amber” appears three separate times in the book of Ezekiel (1:4, 1:27, and 8:2) in the JPS Tanakh, in exactly the same places as it appears in Christian translations, despite the mystery which would surround the meaning of the base word, חשמל apart from the LXX.

#Hebrew#Hebrew language#Hebraicist#Hebraicists#Hebrew studies#Tetragrammaton#Language death#Tanakh#Old Testament#Seputagint#LXX#Dead Sea Scrolls#DSS#Targum#Targumim#Masoretes#Masoretic#Textual criticism#History of the Bible

0 notes

Text

so I just asked my thesis supervisor to point me to some book/article on transcribing/modernising Latin since I unfortunately have some Latin in the book I'm preparing an edition of as my MA and I do not trust myself in doing it by ear, at all. And he just sent me his own rules he has created for some edition or another and I'm just wow, thanks a lot <3

#university#academia#thesis#master's thesis#latin#textual criticism#can I just be done for today after writing two emails?#probably not

0 notes