#Targum

Text

Watch "#9 Bright Nature Form - The First Book of Adam and Eve 1-8" on YouTube

youtube

#torah#the frist book of adam and eve#the first and second book of adam and eve#the forgotten books of eden#adam and eve#aramaic tanakh#scriptures#old testament#torah portion#talmud#torah observant#torah observant christianity#aramaic bible#aramaic targum#aramaic targums#aramaic language#talmud stories#the tanak#tanakh#targum#targums#targum pseudo jonathan#targum onkelos#serpent seed#torah class#shabbat#shabbat shalom#jewish scripture#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

IOTS 2024 Call for Papers

Last time in Amsterdam was with Mack and we watched Celtic v. Ajax. He was not happy with the outcome (his club is called Celtic, it was 0-4 to Ajax).

I will be proposing a paper for IOTS and/or iSBL. I hope to see some of you in Amsterdam this summer! I intend to take in an Ajax match, if possible.

1th International Organization for Targumic Studies

Call for Papers

It is a pleasure for the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

What is the primary sacred text of Judaism?

There are 24 books Judaism claims as its holy writings. They are the five books which tell of the origin of the Israelites and discuss the laws their God gave to them, the Torah (law); eight books written by or about the prophets of ancient Israel, the Neviʾim (prophets); and eleven books which contain wisdom and miscellaneous aspects of Israelite history, the Ketuvim (writings). Altogether, these books comprise the Tanakh.

The Christian Old Testament as used by Protestants has the exact same content as the Tanakh, but arranges the constituent books differently and usually splits the books of Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah into two each, and the book of the minor prophets into twelve. Jews are generally uncomfortable with this name, as it implies that the Tanakh is complete without the New Testament, along with different misconceptions on how Christians have translated and presented the Tanakh, discussed below. For the rest of this FAQ, this set of books will be referred to as the Tanakh except in its capacity of a constituent part of the Christian Bible.

Non-Protestant Christians include a number of books written during the Second Temple era or later in their Old Testament canons. These books are collectively known as the Apocrypha or Deutercanon, and are outside the scope of this FAQ.

What language(s) was the Tanakh written in?

Almost the entire Tanakh was written in Hebrew, while parts of the Daniel and Ezra(-Nehemiah), along with words and phrases from throughout the Tanakh, were written in Aramaic.

Was Biblical Hebrew written with vowels?

The Tanakh was originally written in a writing system called the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and other very early examples of Hebrew writing, and retained by the Samaritans. During the time of the Second Temple, the Jews gradually adopted a script derived from the Imperial Aramaic script, and modified it to become the square script, which is now the more familiar "Hebrew script." Both were ultimately derived from the Phoenician alphabet, and operate on similar principles, to the point where there is essentially a one-to-one correspondence. They are both technically defined as abjads rather than proper alphabets, the reason being that they lack letters whose primary use is to express vowel sounds.

Why wasn't Biblical Hebrew written using a system that clearly marked vowels?

Hebrew is a member of a larger family called the Semitic languages, most of which do not have (or did not use to have) many distinct vowels. Arabic only has three, and there is no strong evidence that Akkadian had more than four. Aramaic, Ge'ez and Amharic all have at least five, and there is evidence that Ugaritic did as well, but the additional vowels in these languages do not converge the way they would if they had been inherited from a common ancestor.

At the beginning of its written history, a predecessor of Hebrew, either Proto-Northwest Semitic or an immediate descendant, likely had three vowel qualities /a i u/. Its writing system, the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, accordingly lacked vowel letters, as a given consonant sequence would have been substantially less ambiguous than in other languages with larger vowel inventories.

In the stages between PNWS and Hebrew, and in Hebrew itself, a number of different sound changes caused its vowel inventory to expand, ultimately adding two, possibly three, more vowel sounds /e o (ǝ)/. As Hebrew developed, so did the variant of the Proto-Sinaitic script used to write it, albeit more slowly, giving rise to both the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet and the square script. As the written forms of a language are more conservative than their spoken forms, and the changes which brought about these additional vowels were very gradual, there was no impetus for any group of scholars to sit down and propose the addition of vowel letters to be used in writing Hebrew before it went extinct around the beginning of the fourth century.

That being said, four letters, alpeh א, waw ו, he ה, and yodh י, used ordinarily to express consonants /ʔ w~v h j/, took on a secondary role of expressing vowels in variant spellings. The letters aleph and he were used for essentially any vowels, waw for rounded vowels, and yod for front vowels. In this capacity, such a letter is called an ʾem qriʾa or mater lectionis.

How do we determine the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew if it is extinct and did not have proper vowel letters?

Hebraicists rely on a number of different methods for determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew words. Even though Hebrew went extinct, it was retained liturgically in Judaism, leading to three different vocalizations, the Tiberian, Babylonian, and Palestinian. During the high middle ages, a group of Jewish scholars called the Masoretes developed systems of vowel markings called the niqqud to clarify these vocalizations in Hebrew writing. Only the Tiberian vocalization survived the middle ages or was extensively covered by niqqud, and it is referenced when determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew.

The matries lectionis produced variant spellings of certain words, which also clarifies the pronunciation.

In ancient times, a Greek translation of the Tanakh was produced called the Septuagint (abbreviated LXX). Its origins are shrouded in fable, but it is generally agreed by historians of the Bible that in the mid-third century BC, about seventy rabbis gathered in Alexandria and translated at least the Torah into Hebrew, with the rest of the Old Testament completed by the first century. As Greek is written in a proper alphabet, the vowels used in proper nouns and loanwords give insight into how these words would have been pronounced in Hebrew.

Around the middle of the third century AD, a critical edition of the Tanakh called the Hexapla was produced. Consisting of six columns, it placed the Hebrew text alongside an attempt to write the Hebrew text with the Greek alphabet (in the second column, this text is called the Secunda), and four different Greek translations. Though it exists in fragmentary condition, the Secunda gives some insights into the pronunciation of Hebrew.

Syllable timing can be predicted based on Biblical poetry.

Finally, as it is part of a larger language family, Hebrew can be compared with other Semitic languages that have been spoken constantly since antiquity. Special emphasis is put on comparison to its closest living relatives, Aramaic and Arabic.

What is the Tetragrammaton?

It is a name for God used well over 6000 times in the Tanakh, spelled using four Hebrew letters, יהוה.

Have any of the above methods been useful in determining the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton?

Judaism developed a taboo against pronouncing the Tetragrammaton during the Second Temple Period. For this reason, except for one possible exception (and even that is doubtful), no LXX manuscript presents a genuine effort to transliterate the Tetragrammaton; the only remaining fragments of the Secunda which include sections featuring the Tetragrammaton replace it with the Hebrew form amidst the Greek letters; and Tiberian vocalization lacks a pronunciation for it. In addition, all four of its letters can be matries lectionis, and it lacks known cognates in other Semitic languages.

Samaritanism developed the taboo later, and a group of Jewish mystics that survived a century or so after the destruction of the Second Temple never had it. In the fourth century, Theodoret, in his Quaestiones in Exodum, records a Samaritan pronunciation of /i.a.ve/, consistent with Clement of Alexandria recording a mystic pronunciation of /i.a.we/ in the fifth book of his Stromata. Since /v/ and /w/ were never distinguished readily in any form of Hebrew, this points to a pronunciation /jah.weh/, hence the spelling Yahweh.

The name "Jehovah" was an earlier rendering of the name, produced from a misconception among Christian Hebraists when encountering the Tetragrammaton in Masoretic texts. To prevent anyone from even accidentally saying the name aloud, a practice arose of saying it with the vowels in the word for "Lord," אדוני adonai. Christian Hebraicists did not realize this was a hybrid word and thought it was God's actual name, producing /ja.ho.vah/, eventually Jehovah.

Is Lashawan Qadash as promoted by various Black Hebrew Israelite groups remotely authentic to the actual pronunciation of ancient Hebrew?

As with almost all other particular teachings of the BHIs, the Lashawan Qadash lacks any kind of historical evidence and is easily disproven.

For example, under LQ, the name of God is not "Elohim," but rather "Alahayam." However, the first element is cognate with Arabic إله /ʔi.laːh/ and is an element of a mile-long list of different theophoric names from the Tanakh, such as Elijah, Daniel, etc, consistently spelled ηλ /eːl/ in the LXX. This points to a front vowel, both long before Hebrew became a distinct language, and towards its extinction. The second vowel is confirmed by the spelling variant which includes a waw, indicating a rounded vowel. However, the BHIs who employ LQ do not use a variant "Alahawayam." The word itself is the plural of the word "eloah" (please note that verbs always indicate grammatical number in Hebrew, and that the actions of the God of Israel are described using singular verbs in the Tanakh) which has always had a letter waw. The same plural ending shows a consistency with vowels in Aramaic plural endings. The pronunciation of the entire word is consistent with the form ελωειμ as found in the Secunda for Psalm 72:18. Black Hebrew Israelitism is usually conspiratorial, and BHIs will suggest the pronunciations of Hebrew proposed through accepted methods of historical methods are actually some kind of wicked plot perpetrated by the Jesuits, Masoretes, adherents of Babylonian mystery religion, or some combination thereof, usually in cahoots with each other. Whatever shadowy force(s) which acted to produce the pronunciation "Elohim" would have had to alter every last Hebrew scroll and carving which contains the singular "eloah," waw in tow, and every last Septuagint and New Testament manuscript containing a theophoric name containing "El" to include the letter ēta, including those manuscripts which laid in dark caves and buried in the desert for centuries; every remaining Secunda fragment to spell the name as ελωειμ; convinced millions of Arabic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to say "ilah" and write accordingly; and convinced millioned of Aramaic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to use front vowels when saying nouns in the plural, and write accordingly, centuries before anyone seriously proposed that Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew were related languages. This is all that would have had to have been done just to deceive the whole world of the pronunciation of just one word. There are far more words which also present a host of problems under LQ.

The existing evidence suggests that LQ originated in 20th-century Harlem, without any historical precedent whatsoever, and does not belong in any serious discussion of Biblical Hebrew.

Why is it said that Hebrew "went extinct" when it has been in constant use by the Jews until the present day?

The term "extinction" in linguistics is used of languages without living native speakers. When the last native speaker of a language dies, that language is then extinct. Sumerian is extinct. Ancient Egyptian is extinct. Gaulish is extinct. Wampanoag is extinct. Ubykh is extinct. No informed person disputes any of these languages are actually extinct. However, many Jews and philosemites take offense at the term "extinction" when used to describe the ultimate fate of Biblical Hebrew.

The fact of the matter is that Assyria dispersed most of the tribes of Israel, and Babylon captured what was left. We do not know what happened to the 10 lost tribes, but the members of Judah and Levi began to speak Aramaic. Even after Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to resettle Judaea, most Jews continued to speak Aramaic and teach it to their children. Through the Second Temple Era, Hebrew went from threatened to endangered. It did not matter that Hebrew was used in the synagogues; whether a language is alive or dead is determined at the cradle rather than the altar.

Bar Kochba attempted to reinvigorate Hebrew during his revolt around AD 130. After this revolt was suppressed by the Romans, any hope of Hebrew continuing were essentially dashed. The Mishnah, thought to have been among the final documents written in Hebrew during the lifetime of any native speakers, was completed around the turn of the third century, and was in a form that showed obvious changes one would expect of a language approaching extinction. There is not a shred of evidence that there were any native speakers more than a century after the Mishnah.

Extinct languages find use liturgically in different religious traditions throughout the world. No Jewish person or philosemite would deny, given sufficient information, that Avestan is extinct, despite its continuing use in Zoroastrianism. Nor would they deny the same about Coptic, Latin, Ge'ez, or Sanskrit, nor would they deny that Sumerian was in use by various pagan groups as long as 2000 years after it went extinct. Yet, for these same people, it is "inaccurate" or even "bigoted" to suggest the same regarding Hebrew. The knowledge of Hebrew during late antiquity and the middle ages was restricted almost exclusively to rabbis and Jewish literati, exactly 100% of whom spoke some other language natively. Yes, Hebrew was revived during the modern period, but it took great effort in creating enough vocabulary to describe the modern world, and there are enough difference between modern and Biblical Hebrew to motivate Avraham Ahuvya to create a modern Hebrew translation (for lack of a better term) of the Tanakh.

Simply put, if these people want to discuss historical linguistics, they need to use terms which are found in historical linguistics, as they are defined by historical linguistics, terms which specialists in the field, Jew and gentile, accepted a long time ago. This includes the term “extinction.”

Why don't Christians use Hebrew source texts when translating the Tanakh?

They do, and have been doing so constantly since the Reformation.

The printed Hebrew edition of the Tanakh, by Daniel Bomberg, was arranged from several Masoretic manuscripts collected and collated by Jacob ben Hayyim. This was the primary base text of the Old Testament in all Protestant English translations of the Bible from at least the Geneva Bible (first published 1557) up until at least the Revised Version (published 1885), and seemingly the Darby Bible of 1890 and American Standard Version of 1901. Only Catholic Bibles used the Vulgate as a source, and an obscure translation of the LXX by Charles Thompson was printed in 1808; this translation made its source clear on the title page, not that almost anyone paid attention to it.

A scholar of the Tanakh named Rudolph Kittel collated an even greater set of Masoretic manuscripts, creating the Biblia Hebraica Kittel (BHK), first published 1906. Later, it was determined that a manuscript, which had been produced in Cairo, mysteriously ended in the possession of a Russian Jewish collector named Abraham Firkovich, was displayed in Odessa, and then later in St. Petersburg (later Leningrad) was in fact the oldest complete copy of the Tanakh in Hebrew. It is now known as the Westminster-Leningrad Codex, and was made the primary source of printings of the BHK from 1937 onward, and by extension the OT of the Revised Standard Version. It later became the primary basis of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), first published 1968, and by extension the OT in the New American Standard Bible, New International Version, Good News Bible, New RSV, New KJV, Contemporary English Version, World English Bible, English Standard Version, and New Living Translation, just to name a few. Another printed edition of the Old Testament in Hebrew, the Biblia Hebraica Quinta, was completed last year, also derived from the WLC, and there is no reason to believe it will not serve as the basis of future translations.

The LXX, Targumim, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Samaritan Pentateuch are occasionally consulted, mostly to illuminate the meaning of obscure Hebrew words or phrases, or solve inconsistencies among Masoretic manuscripts. The translators invariably place conspicuous footnotes to indicate such. If you do not believe Jewish translators of the Tanakh do the same thing, you need to explain how “amber” appears three separate times in the book of Ezekiel (1:4, 1:27, and 8:2) in the JPS Tanakh, in exactly the same places as it appears in Christian translations, despite the mystery which would surround the meaning of the base word, חשמל apart from the LXX.

#Hebrew#Hebrew language#Hebraicist#Hebraicists#Hebrew studies#Tetragrammaton#Language death#Tanakh#Old Testament#Seputagint#LXX#Dead Sea Scrolls#DSS#Targum#Targumim#Masoretes#Masoretic#Textual criticism#History of the Bible

0 notes

Link

About This TextComposed: Talmudic Israel, c.150 – c.250 CE

Targum Pseudo-Jonathan is a western targum (translation) of the Torah (Pentateuch) from the land of Israel (as opposed to the eastern Babylonian Targum Onkelos). Its correct title was originally Targum Yerushalmi (Jerusalem Targum), which is how it was known in medieval times. But because of a printer's mistake it was later labeled Targum Jonathan, in reference to Jonathan ben Uzziel. Some editions of the Pentateuch continue to call it Targum Jonathan to this day. Most scholars refer to the text as Targum Pseudo-Jonathan. This targum is more than a mere translation. It includes much Aggadic material collected from various sources as late as the Midrash Rabbah as well as earlier material from the Talmud. It is effectively a combination of a commentary and a translation. In the portions where it is pure translation, it often agrees with the Targum Onkelos. The date of its composition is disputed. It cannot have been completed before the Arab conquest as it refers to Mohammad's wife Fatima, but might have been initially composed in the 4th Century CE. However, some scholars date it in the 14th Century

0 notes

Text

Gay Big Chested Indian Cums on Cam

Audible Cum (TM) Compilation - Cumshots So Big You Can Hear / Cumpilation

Johnny Montana comendo amigo viadinho

Gay bondage porn movie xxx Sean is like a lot of the dominant boys,

Video rubato amatoriale veneto

Walmart Flashing in a Mini Dress - Upskirt - Lydia Luxy

Old man small girl and blonde woman Her Wet Dream

SMOKING HOT ASIAN SLUT RIDING ALIEN DILDO IN BATHROOM (Like, Comment, Subscribe!)

Cute latina maid Rebeca Linares with huge tits blowing big shlong

new asian teen girl

#psittacomorphic#MindelMindel-riss#fig-tree#crawfishing#incrementalist#courtepy#galleted#oppugns#Targum#anaunter#telodendrion#nailers#Pro-colombian#kindredness#olater#duoden-#splanchnopathy#antipode's#crengle#aberuncator

1 note

·

View note

Text

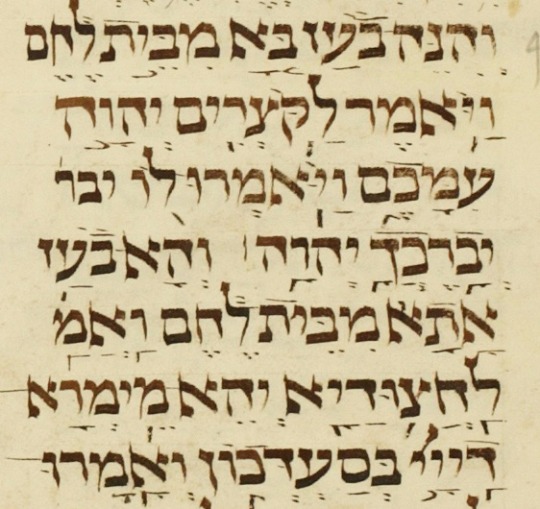

Balaam Sets His Face Towards the Calf — A Targum Tradition

By Dr. Shlomi Efrati

The Jewish Aramaic renderings of the Hebrew Bible, collectively known as “Targum”—the Hebrew/Aramaic word for both “interpretation” and “translation”—were composed over several centuries, in various places and for different purposes. While the earliest Targums for the Pentateuch and the Prophets, known as Onqelos and Jonathan respectively, were presumably composed during the first centuries of the common era in an Aramaic speaking environment, the latest Targums—for (most of) the books of the Writings—were probably composed sometime towards the end of the first millennium C.E., in a place and time where Aramaic was no longer a spoken language.

Unlike biblical translations into most other languages, which simply became “the Bible” for their respective communities, the Targums have always accompanied, but never replaced, the (Hebrew) Bible. This may partly explain why the Targums are both more, and less, than simply translations. Less—because in many cases they fail to offer a straightforward rendering of the Hebrew text; More—because they tend to interpret, paraphrase, or expand the Hebrew text in various ways.

How, why, and for what reason(s) these interpretative renderings originally came into being is not altogether clear, and it is likely that different answers apply to different Targums. At any rate, the earliest rabbinic sources (dating from the beginning of the 3rd century C.E.) attest to—and attempt to regulate—the liturgical reading of Targums. Furthermore, throughout rabbinic literature various Targums are quoted and discussed—not always approvingly—as objects of study. Both these functions—the liturgical and literary-intellectual—continue to be relevant (in varying degrees) until this very day.

Targum Onqelos

The plurality of Targums is perhaps most apparent in the Targums for the Pentateuch. First there is Targum Onqelos (hereafter simply Onqelos), which offers a complete, continuous, and relatively literal translation for the whole Pentateuch. Onqelos’ Aramaic has close affinities to the “international” or “official” Aramaic dialect, which was in use across the Near East during the last centuries B.C.E.

Some version of Onqelos served as the standard Targum for the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud (roughly 3rd–5th centuries C.E.), who also preserved—or created—the tradition that a certain proselyte named Onqelos translated the Pentateuch (though in fact the Babylonian Talmud never refers to this Targum as “Targum Onqelos”). The Babylonian Geonim, during the last centuries of the first millennium CE, referred to Onqelos as “the Targum of our Rabbis” (תרגומא דרבנן), and for most medieval Jewish communities Onqelos was the common—and in many cases the only—Targum, thus simply referred to as “The Targum.”

Onqelos was (and still is) widely read, studied and copied, and its text is remarkably uniform throughout its many manifestations. It is preserved in more than 450 relatively complete manuscripts (mostly dating from the 13th–15th centuries), which differ mainly in matters of orthography or occasional scribal mistakes. Only rarely and sporadically do revisions or additions appear, and even these usually concern single words or very short phrases.

The Palestinian Targums (“Targum Yerushalmi”)

Another branch of Targum to the Pentateuch is, or more accurately are, the Palestinian Targums (also collectively referred to as Targum Yerushalmi). These Targums were composed in an Aramaic dialect similar to that of both the Palestinian Talmud and the midrashic and poetic literature of the rabbis from Byzantine Palestine (about the 3rd–7th centuries CE). They tend to be far more interpretative in nature, and contain many expansions of various types, such as exegetical, narratival, and even poetic.

The Palestinian Targums are attested in only a handful of manuscripts, which vary greatly in both form and content. Some manuscripts offer a continuous Targum text. Others contain excerpts of Targum—for single words, phrases, or verses—and are thus called “Fragment Targums.” A third group, which preserves small selections of Targum expansions, is commonly referred to as “Tosefta” (literally—“addition”). Lastly, there also exists another complete Pentateuchal Targum—apparently representing a late compilation, which among other sources also made extensive use of the Palestinian Targums—commonly known today as Targum pseudo-Jonathan.

Among these various sources, textual variation is the norm, not the exception. Though they do seem to have a common textual basis, in many cases it is a base for changes, such as rephrasing, reordering, additions, omissions, and so on.

Cross-Pollination

Onqelos and the Palestinian Targums are radically different in their language, transmission, and reception. And yet, they are also interrelated in several ways, starting with their earliest stages of composition throughout their transmission and reception in various medieval communities. One of the manifestations of this complex relationship are additions to Onqelos which have close parallels in the Palestinian Targums.

Such additions can be, and many times are, easily discarded as mere interpolations. Seen as secondary to the fuller Palestinian Targum versions, and foreign to the “real” Onqelos, they tend to be considered of little value for the study of either Onqelos or the Palestinian Targum tradition. Yet this issue is both more complex and more intriguing.

Balaam Sets His Face Toward the Wilderness

One of the most widely attested additions to Onqelos appears in the story of Balaam’s oracles (Numbers 22–24). According to the biblical narrative, when the Israelites came near Moab towards the end of their 40 years of wandering in the wilderness, Balak king of Moab got worried and hired Balaam to curse them. Yet—as Balaam expressly informed the king—he was only able to pronounce the words God put in his mouth (Numbers 22:38), and so he ended up blessing Israel rather than cursing them. Numbers 24:1 reports that, after having offered two oracles full of blessings and praise to Israel,

במדבר כד:א וַיַּרְא בִּלְעָם כִּי טוֹב בְּעֵינֵי יְ־הוָה לְבָרֵךְ אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל וְלֹא הָלַךְ כְּפַעַם בְּפַעַם לִקְרַאת נְחָשִׁים וַיָּשֶׁת אֶל הַמִּדְבָּר פָּנָיו.

Numbers 24:1 Balaam saw that it pleased YHWH to bless Israel. So he did not go, as previous times, to look for omens(?),[13] but set his face toward the wilderness.

Why Balaam decided to turn to the wilderness remains unexplained in the biblical narrative.

Balaam Sets His Face Toward the Calf: Onqelos

Following its usual manner, Onqelos faithfully renders the Hebrew text וישת אל המדבר פניו into the Aramaic ושוי למדברא אפוהי “and he set his face toward the wilderness”—a simple, literal translation. This translation, which can be found in common modern editions of the Pentateuch with Onqelos, is also attested in multiple early and reliable manuscripts. Yet this is not the only version of Onqelos to be found. Numerous manuscripts (over 90 in my current database), as well as some early printed editions, preserve an expanded version of Onqelos:

ושוי לקבל עגלא דעבדו ישראל במדברא אפוהי

He set his face towards the Calf that the Israelites made in the wilderness.

According to this version, “the wilderness” in the biblical text refers to the infamous incident of the Golden Calf. Yet the link between Balaam and the Calf remains rather vague. It is not clear if Balaam intended to evoke Israel’s sinfulness, in the hope of kindling God’s anger at them and thus allowing him to harm them with his curses; or alternatively, if he was trying to employ some malignant power symbolised by, or residing in, the Golden Calf itself.

Last but not least, as the incident of Balaam takes place almost forty years after the Golden Calf is destroyed, having Balaam “set his face toward the (actual) Calf” is puzzling. Perhaps what is meant is that Balaam set his face in the direction where the Calf once stood and the sinful act took place, though there are simpler ways to convey this meaning.

Be that as it may, this awkward phrasing seems to reflect the secondary nature of the expanded version, as the phrase “he set his face” was left unaltered even when the expansion regarding the Calf was inserted.

Onqelos, Rashi, and Ramban

Secondary though it may be, the expansion concerning the Calf was integrated into Onqelos’ text at a relatively early stage—much earlier, in fact, than most Onqelos manuscripts at our disposal. Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki, France, latter half of the 11th century) commented on the opaque phrase “(he set his face) to the wilderness” simply by adding a single word: כתרגומו “according to its Targum.” This is Rashi’s usual way to refer to Onqelos, as he quite extensively does.

However, such a reference would not make much sense if Rashi had the (presumably) original text of Onqelos in front of him, which does not add any interpretation or clarification to the biblical text. It is far more likely that Rashi is referring here to the expanded version of Onqelos, and—following that version—considered Balaam’s act to be somehow related to the incident of the Golden Calf. Thus, already by Rashi’s time this expanded version was both common and well known, so that Rashi could refer to it simply as “its Targum” without having to add any further clarification or qualification.

Several generations later, and in a different geographical and cultural setting, Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nahman, Spain, mid-13th century) offered a more critical evaluation of both Rashi’s interpretation and the Targum he referred to:

כי היה הרב מתרגם בו "ושוי למדברא דעבדו ביה בני ישראל עגלא אנפוהי." ואין בנוסחאות מדוקדקות מתרגומו של אונקלוס כן, אבל הוא כתוב בקצתן שהוגה בהן מן התרגום הירושלמי.

For the Master (Rashi) had for this verse the Targum: “And he set his face toward the wilderness, where the Israelites had made the calf.” But accurate copies of Onqelos do not contain this, yet it is written in a few of them, in which it was glossed from Targum Yerushalmi.

Ramban quotes in full the expanded version of Onqelos, which Rashi only hinted to, and further asserts that the expansion concerning the Calf was derived from “Targum Yerushalmi,” and is thus not genuine to Onqelos (and hence, by implication, also unreliable). In his literary-critical analysis—and to some extent also in his dismissive attitude—Ramban predates much of the modern scholarship regarding “Palestinian”(-like) additions to Onqelos.

Balaam Causes the Sin of the Calf to be Remembered: Palestinian Targums

Although Ramban does not bring further evidence to support his claim regarding the expansion to Onqelos being derived from “Targum Yerushalmi,” an examination of the Palestinian Targum sources at our disposal seems to affirm his observation. With some variations, these Targums offer the following expanded rendering for Numbers 24:1:

ושוי למדברה אפוי והוה מדכר להון עבדה דעגלה

He set his face toward the wilderness and was causing the deed of the calf to be remembered against them.

Like the expanded version of Onqelos, the Palestinian Targum also paraphrases the Hebrew text, linking “the wilderness” to the sin of the Golden Calf. However, these versions are not identical in content or in form:

Onqelos

ושוי למדברא אפוהי

He set his face toward the wilderness.

Expanded Onqelos

ושוי לקבל עגלא דעבדו ישראל במדברא אפוהי

He set his face toward the Calf that the Israelites made in the wilderness.

Palestinian Targum

ושוי למדברה אפוי והוה מדכר להון עבדה דעגלה

He set his face toward the wilderness and was causing the deed of the calf to be remembered against them.

The table above demonstrates, first and foremost, the formal differences between the two versions: though their content is similar, each uses different words and is structured in a different manner. These formal differences are consistent: none of the (few) Palestinian Targum sources we possess presents the version found in Onqelos’ manuscripts, while the additions to Onqelos never seem to adopt the versions found in the Palestinian Targums. Hence it could be concluded that the numerous manuscripts attesting the addition to Onqelos represent a self-standing, independent line of transmission, rather than recurring cases of copying from direct sources of Palestinian Targum.

Of course, it is still possible that the addition to Onqelos was derived from a certain Palestinian Targum early on and continued to be transmitted separately. However, a careful examination of the content of both versions shows that a direct dependence between them is unlikely. Whereas the expanded version of Onqelos states that Balaam “set his face towards the Calf” itself—even though it was destroyed almost forty years earlier—the Palestinian Targum version explains that Balaam looked toward the wilderness to evoke the sin of Israel, and thus, presumably, turn God against them.

In this way, this version manages to avoid the “anachronism” of directly linking Balaam and the Calf, while explaining in which manner Balaam intended to employ the Calf. And this is precisely the reason why it seems unlikely that this version is the direct source of the expanded version of Onqelos, which neither removed the “anachronism” nor bothered clarifying the function of the Calf.

As I mentioned above, the expanded version of Onqelos allows for the possibility that Balaam intended to employ some magical or demonic power associated with the Calf. In the Palestinian Targum version such an interpretation is impossible. Thus, while from a literary point of view the expanded version of Onqelos may seem inferior to the version of the Palestinian Targums, this does not mean it is secondary or corrupt. Quite the contrary. It might imply that the addition to Onqelos represents a less developed—and thus, perhaps, more rudimentary—form of the expansion than that which is found in the Palestinian Targums we have at hand.

The Many Faces of a Targum Tradition

The formal differences and change in content suggest that the expanded version of Onqelos is not (directly) derived from the Palestinian Targum sources known today. Rather, it seems that both the expanded version of Onqelos and the Palestinian Targum sources preserve parallel, yet distinct, versions of an expansion concerning the Calf. Put differently, the expansion to Onqelos on one hand, and the Palestinian Targum sources on the other, represent different versions of the same tradition, though what was the nature of this tradition is difficult to say.

It could have been an isolated elaboration on this specific verse, which was incorporated, in slightly different forms, in both textual traditions. Or it might have been derived from an alternative (complete) Palestinian Targum. Either way, the addition to Onqelos could offer a glimpse into the diverse nature of the Palestinian Targum tradition, whose currently available sources—divergent as they might be—still represent only one of its various, now all but lost, manifestations. Therefore, the addition to Onqelos in Numbers 24:1 may very well be derived from the Palestinian Targum tradition—but, I would argue, not the specific Palestinian Targum sources currently known to us.

Source (and find footnotes at): https://www.thetorah.com/article/balaam-sets-his-face-towards-the-calf-a-targum-tradition

1 note

·

View note

Text

Concept for a new tranformers oc named Targum, Who's like bubblegum themed racecar

Shoots colorful balls of tar at people, used to be a repair bot before the war and got swept up with the autobots when it started, but the actual killing and violence and devastation of her planet was too much for her to handle

So a medic gave her like a visor that made everything more akin to a videogame, she still knows the enemies in her games are actual people half the time, but shed much rather ignore it and pretend her videogame reality was her real one than be racked with the guilt and panic of her world literally going up in flames, and what she's had to do to try and protect it

#patramble#transformersocs#transformeroc#targum🏁🎭#🏁🎭#oc concept#girls girls girls#robots robots robots

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The best article I’ve seen yet describing what ‘First Kill’ actually is and how well it does it.

This vvvvv

“That might seem like the show is directionless if one moment can switch it up, but in reality, sometimes a moment is all it takes for your life to change. The same can be said about the "Big Bad," as it’s called in these kinds of shows. It can change from episode to episode, and it constantly seems to be smirking and saying “oh, you thought.” Every character can be a villain or a hero — and if that isn’t like real life, I don’t know what could be.”

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

another fun biblical anecdote is that despite the story of David and Goliath being very well known the bible itself is very unclear as to how it happened. the most famous description is of course the one in 1 Samuel 17, which was redacted by the deuteronomistic historian and goes into detail about the duel and so on. but 2 Samuel 21:19 which was written earlier actually says “Elhanan son of Jaare-oregim the Bethlehemite” killed Goliath. it would be logical to conclude that Elhanan is another name of David as both are said to be from Bethlehem. but then 1 Chronicles 20:5 several centuries later (4th century vs 7th) kinda ruins that by claiming that “Elhanan son of Jair killed Lahmi, the brother of Goliath the Gittite” where Jaare-oregim seems to be a corruption of Jair and “oregim” (=beam, to refer to the spear) but Lahmi is a corruption of “Bethlehmite”, which in ancient hebrew would be “beit ha-lahmi” so there’s no great way to like, coordinate all of these. the KJV being what it is just cheats and has in 2 Samuel 21:19 that Elhanan killed the brother of Goliath, just as in Chronicles, for convenience, even though the original hebrew (and not the septuagint either but i didnt check) makes no mention of brothers

#bibleposting#interestingly they're all very consistent on Goliath and Goliath being from Gath#the samaritan targum though identifies david with elhanan but also their killing of goliath take place at different times and places#david's and elhanan's that is#there was also a Elhanan son of Dodo who was one of king David's elite fighters so thats also confusing

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Adam Targum is an American film and television producer and writer. He is best known for his work on Eleventh Hour (2008), CSI: NY (2004) and Banshee (2013).

0 notes

Text

Watch "#7 Part 3 Targum Pseudo-Jonathan Genesis 2:4-3:24" on YouTube

youtube

#scriptures#torah portion#fe#talmud#torah observant#torah observant christianity#old testament#torah#targum#targums#targum pseudo-jonathan#aramaic targum#aramaic targums#aramaic bible#tanakh#aramaic tanakh#jerusalem#torah observant wisconsin#flat earth#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Jesus’ metaphorical saying about new wine bursting old wineskins coheres with Job 32:19: ‘My heart is like wine that has no vent; like new wineskins, it is ready to burst.’ The Job Targum parallels it even more closely ..." #Intertextuality

intertextual.bible/t/2855

0 notes

Text

Guest on the Daily Dose of Aramaic Podcast

I was honored to be a guest on the Daily Dose of Aramaic show with Dr. Scott Callaham. It was an enjoyable wide-ranging conversation about the Targumim and kicks off their study of the Targumim and Targumic Aramaic. Be sure to go back and see his interview with Ed Cook.

youtube

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Mikvah Stories by Chaya Raichik

Mikvah Stories by Chaya Raichik

A Collection of True Stories of Women Overcoming Today’s Challenges

“In our very tight-knit Moroccan community all everyone was talking about was how dangerous it was. How would women be able to use the mikvah?”

“I counted three times. No way could this coincide with mikvah night.”

Here are modern-day Mikvah stories.

Women just like you who persevered to keep the mitzvah of Taharas…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

For a school assignment, I'm assembling an anthology around the theme of queer divinity and desire, but I'm having a hard time finding a fitting essay/article (no access to real academic catalogues :/ ), do you know of any essays around this theme?

below are essays, and then books, on queer theory (in which 'queer' has a different connotation than in regular speech) in the hebrew bible/ancient near east. if there is a particular prophet you want more of, or a particular topic (ištar, or penetration, or appetites), or if you want a pdf of anything, please let me know.

essays: Boer, Roland. “Too Many Dicks at the Writing Desk, or How to Organize a Prophetic Sausage-Fest.” TS 16, no. 1 (2010b): 95–108. Boer, Roland. “Yahweh as Top: A Lost Targum.” In Queer Commentary and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Ken Stone, 75–105. JSOTSup 334. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2001. Boyarin, Daniel. “Are There Any Jews in ‘The History of Sexuality’?” Journal of the History of Sexuality 5, no. 3 (1995): 333–55. Clines, David J. A. “He-Prophets: Masculinity as a Problem for the Hebrew Prophets and Their Interpreters.” In Sense and Sensitivity: Essays on Reading the Bible in Memory of Robert Carroll, edited by Robert P. Carroll, Alastair G. Hunter, and Philip R. Davies, 311–27. JSOTSup 348. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002. Graybill, Rhiannon. “Yahweh as Maternal Vampire in Second Isaiah: Reading from Violence to Fluid Possibility with Luce Irigaray.” Journal of feminist studies in religion 33, no. 1 (2017): 9–25. Haddox, Susan E. “Engaging Images in the Prophets: Feminist Scholarship on the Book of the Twelve.” In Feminist Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Retrospect. 1. Biblical Books, edited by Susanne Scholz, 170–91. RRBS 5. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013. Koch, Timothy R. “Cruising as Methodology: Homoeroticism and the Scriptures.” In Queer Commentary and the Hebrew Bible, edited by Ken Stone, 169–80. JSOTSup 334. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2001. Tigay, Jeffrey. “‘ Heavy of Mouth’ and ‘Heavy of Tongue’: On Moses’ Speech Difficulty.” BASOR, no. 231 (October 1978): 57–67.

books: Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006. Bauer-Levesque, Angela. Gender in the Book of Jeremiah: A Feminist-Literary Reading. SiBL 5. New York: P. Lang, 1999. Black, Fiona C., and Jennifer L. Koosed, eds. Reading with Feeling : Affect Theory and the Bible. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2019. Brenner, Athalya. The Intercourse of Knowledge: On Gendering Desire and “Sexuality” in the Hebrew Bible. BIS 26. Leiden: Brill, 1997. Camp, Claudia V. Wise, Strange, and Holy: The Strange Woman and the Making of the Bible. JSOTSup 320. Gender, Culture, Theory 9. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. Chapman, Cynthia R. The Gendered Language of Warfare in the Israelite-Assyrian Encounter. HSM 62. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2004. Creangă, Ovidiu, ed. Men and Masculinity in the Hebrew Bible and Beyond. BMW 33. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2010. Eilberg-Schwartz, Howard. God’s Phallus: And Other Problems for Men and Monotheism. Boston: Beacon, 1995. Huber, Lynn R., and Rhiannon Graybill, eds. The Bible, Gender, and Sexuality : Critical Readings. London, UK ; T&T Clark, 2021. Guest, Deryn. When Deborah Met Jael: Lesbian Biblical Hermeneutics. London: SCM, 2005. Graybill, Rhiannon, Meredith Minister, and Beatrice J. W. Lawrence, eds. Rape Culture and Religious Studies : Critical and Pedagogical Engagements. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019. Graybill, Rhiannon. Are We Not Men? : Unstable Masculinity in the Hebrew Prophets. New York, NY: Oxford University Press USA, 2016. Halperin, David J. Seeking Ezekiel: Text and Psychology. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. Jennings, Theodore W. Jacob’s Wound: Homoerotic Narrative in the Literature of Ancient Israel. New York: Continuum, 2005. Macwilliam, Stuart. Queer Theory and the Prophetic Marriage Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible. BibleWorld. Sheffield and Oakville, CT: Equinox, 2011. Maier, Christl. Daughter Zion, Mother Zion: Gender, Space, and the Sacred in Ancient Israel. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2008. Mills, Mary E. Alterity, Pain, and Suffering in Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. LHB/OTS 479. New York: T. & T. Clark, 2007. Stökl, Jonathan, and Corrine L. Carvalho. Prophets Male and Female: Gender and Prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Ancient Near East. AIL 15. Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2013. Stone, Ken. Practicing Safer Texts: Food, Sex and Bible in Queer Perspective. Queering Theology Series. London: T & T Clark International, 2004. Weems, Renita J. Battered Love: Marriage, Sex, and Violence in the Hebrew Prophets. OBT. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1995.

78 notes

·

View notes