#old frisian

Text

The word bairn (child), which is used in Scots, Northern and Scottish English, is closely related to born and to the verb to bear. These words all come from a root meaning 'to carry'. When a baby is born it's been carried to term. The infant is then carried around. Click the infographic for more.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#german#dutch#scots#old english#old norse#danish#swedish#norwegian#lingblr#icelandic#proto-germanic#gothic#old high german#old saxon#low saxon#old frisian#frisian#old dutch#middle dutch#proto-indo-european

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northumbrian Rune Poems is now officially available for purchase. Digital and physical copies available here.

Inspired by the Old English Rune Poem, Northumbrian Rune Poems centres its focus on the Early Medieval English Futhorc runerows with additional attention paid to the four runes that were in use in Northumrbia. Mixing free verse poetry with kennings found within Old Norse and Old English poetry, Northumbrian Rune Poems is a magical read that breathes new life into an otherwise neglected runerow. Alongside each poem is an Old English adaptation written in a Northumbrian dialect using Old English alliterative style to capture the spirit of the poems in a new light.

#north sea poet#heathenry#poetry#my poetry#nico solheim-davidson#heathen#runes#futhorc#Northumbria#Heathen Poet#Heathen Poetry#north sea rune poems#northumbrian futhorc#anglo-saxon futhorc#anglo-frisian futhorc#rune poems#old english#anglo saxon

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merseburger Spells

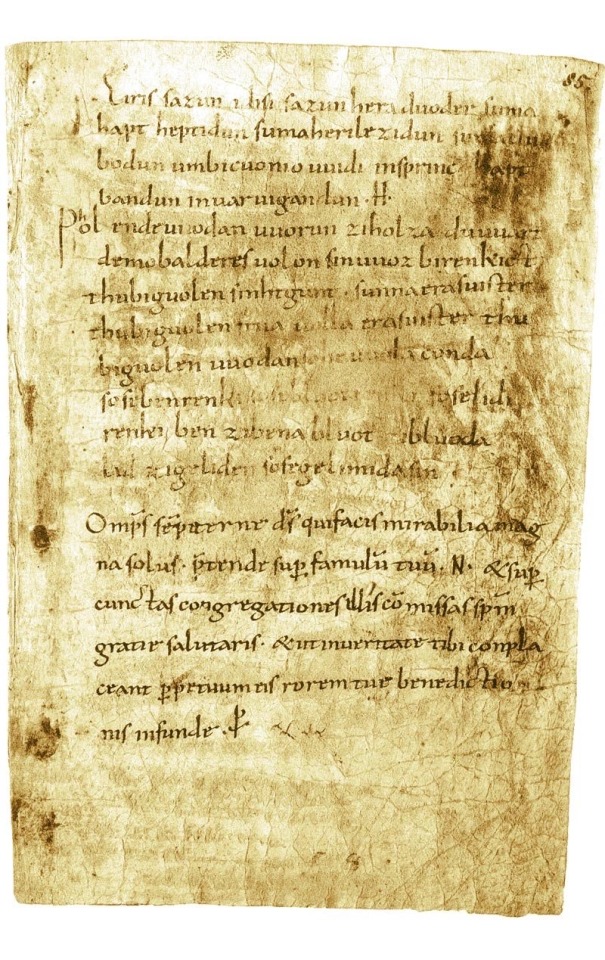

The Merseburg Spells or Incantations are two magic spells found in a Latin Sacramentarium and are written in Carolingian minuskel. The manuscript originates from the Abbey of Fulda, Germany and are dated around 800-900 AD, but only rediscovered in 1841.

The spells do not show any sign of Christian influence and are the only written proof of Germanic mythology in Old High German.

The first spell tells of prisoners of war which are freed by the Idisi. An unknown kind of god-like figures, possibly a Germanic version of Valkyries.

The second spell is a healing incantation. Wotan rides through the woods with Balder, until Balders horse named Phol gets hurt. Wotan, Friia (Freya), her sister Volla and Sinthgund and her sister Sunna sing to the horse; let your wounds be cured.

There are other version of the second spell known, but in different rhyming couplets and turned into a Christian motive.

English and Dutch speakers may identify most of the words without knowing the lyrics first.

Merseburger Domstiftbibliothek, codex 136, f85r

#germanic folklore#Germanic literature#old high German#fulda#merseburg#Merseburg spells#Odin#wodan#uuotan#norse mythology#germanic mythology#field archaeology#archaeology#linguistics#Viking mythology#balder#carolingian#Merovingian#Frisian#charlemagne#frankish

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Frisian Woman * - Friedrich Kallmorgen, 1910

German, 1856-1924

Oil on canvas, 51 x 40 cm.

* Old mother with a coffee cup in her living room in Hindeloopen at the IJsselmeer.

#Friedrich Kallmorgen#german artist#woman portrait#Frisian Woman#black cat#morning coffee#frisian interior scene#Frisland#Friesland#old woman

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

It libben fan 'e bisten. Yn marren en rivieren. Ljouwert 1982

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

178. You Up?

#banter#comedy#crime#english#family#florida#friends#frisian#funny#hilarious#history#interesting#jamison#languages#man#old#rage#road#science#true

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anglo-Frisian Perspective on the Pronunciation of Old Norse Ǫ

Anglo-Frisian Perspective on the Pronunciation of Old Norse Ǫ

Written by Dyami Millarson

Can you imagine the Vikings roaming around in this forest and talking with each other casually in Old Norse and as it so happens, utter a few ordinary Old Norse words that contain the vowel sound ǫ?

Old Norse distinguishes the rounded back vowels o and u-umlaut-derived ǫ (i.e., a + u = ǫ, or more properly according to linguistic convention: a + u > ǫ, where > means…

View On WordPress

#East Frisian languages#Frisian language family#North Frisian languages#Old Norse phonology#phonological reconstruction#reconstructed phonology#u-mutation#u-umlaut#West Frisian languages

0 notes

Text

winter (n.)

Old English winter (plural wintru), "the fourth and coldest season of the year, winter," from Proto-Germanic *wintruz "winter" (source also of Old Frisian, Dutch winter, Old Saxon, Old High German wintar, German winter, Danish and Swedish vinter, Gothic wintrus, Old Norse vetr "winter"), probably literally "the wet season," from PIE *wend-, nasalized form of root *wed- (1) "water; wet"). On another old guess, cognate with Gaulish vindo-, Old Irish find "white." The usual PIE word is *gheim-.

Proto-Indo-European root meaning "winter."

It forms all or part of: chimera; chiono-; hiemal; hibernacle; hibernal; hibernate; hibernation; Himalaya.

fabulous monster of Greek mythology, slain by Bellerophon, late 14c., from Old French chimere or directly from Medieval Latin chimera, from Latin Chimaera, from Greek khimaira, name of a mythical fire-breathing creature (slain by Bellerophon) with a lion's head, a goat's body, and a dragon's tail, a word that also meant "year-old she-goat" (masc. khimaros), from kheima "winter season," from PIE root *gheim- "winter."

As an adjective in Old English. The Anglo-Saxons counted years in "winters," as in Old English ænetre "one-year-old;" and wintercearig, which might mean either "winter-sad" or "sad with years." Old Norse Vetrardag, first day of winter, was the Saturday that fell between Oct. 10 and 16.

spring (n.)

"season following winter, first of the four seasons of the year; the season in which plants begin to rise," by 1540s, a shortening of spring of the year (1520s), which is from a special sense of an otherwise now-archaic spring (n.) "act or time of springing or appearing; the first appearance; the beginning, birth, rise, or origin" of anything (see spring v., and compare spring (n.2), spring (n.3)).

The earliest form seems to have been springing time (early 14c.). The notion is of the "spring of the year," when plants begin to rise and trees to bud (as in spring of the leaf, 1520s).

The Middle English noun also was used of sunrise, the waxing of the moon, rising tides, sprouting of the beard or pubic hair, etc.; compare 14c. spring of dai "sunrise," spring of mone "moonrise." Late Old English spring meant "carbuncle, pustule."

As the word for the vernal season it replaced Old English lencten (see Lent). Other Germanic languages take words for "fore" or "early" as their roots for the season name (Danish voraar, Dutch voorjaar, literally "fore-year;" German Frühling, from Middle High German vrueje "early").

In 15c. English, the season also was prime-temps, after Old French prin tans, tamps prim (Modern French printemps, which replaced primevère 16c. as the common word for spring), from Latin tempus primum, literally "first time, first season."

summer (n.)

"hot season of the year," Old English sumor "summer," from Proto-Germanic *sumra- (source also of Old Saxon, Old Norse, Old High German sumar, Old Frisian sumur, Middle Dutch somer, Dutch zomer, German Sommer), from PIE root *sm- "summer" (source also of Sanskrit sama "season, half-year," Avestan hama "in summer," Armenian amarn "summer," Old Irish sam, Old Welsh ham, Welsh haf "summer").

autumn (n.)

season after summer and before winter, late 14c., autumpne (modern form from 16c.), from Old French autumpne, automne (13c.), from Latin autumnus (also auctumnus, perhaps influenced by auctus "increase"), which is of unknown origin.

Perhaps it is from Etruscan, but Tucker suggests a meaning "drying-up season" and a root in *auq- (which would suggest the form in -c- was the original) and compares archaic English sere-month "August." De Vaan writes, "Although 'summer', 'winter' and 'spring' are inherited IE words in Latin, a foreign origin of autumnus is conceivable, since we cannot reconstruct a PIE word for 'autumn'".

Harvest (n.) was the English name for the season until autumn began to displace it 16c. Astronomically, from the descending equinox to the winter solstice; in Britain, the season is popularly August through October; in U.S., September through November. Compare Italian autunno, Spanish otoño, Portuguese outono, all from the Latin word.

As de Vaan notes, autumn's names across the Indo-European languages leave no evidence that there ever was a common word for it. Many "autumn" words mean "end, end of summer," or "harvest." Compare Greek phthinoporon "waning of summer;" Lithuanian ruduo "autumn," from rudas "reddish," in reference to leaves; Old Irish fogamar, literally "under-winter."

summer and winter both with PIE roots, but autumn and spring both without!

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m sure someone else has beaten me to it, but here’s a translation of the ledger Andreas can find in the abbey library, with my translation notes – long post below the cut:

Mother Katharine, Prioress

AD 1459[1]

Sister Hildegard, 16 years old

Named Anna Gölderich, of Ravensburg. Proficient in Latin. Studious and obedient, with a soft, pious voice. 150 florins donated by her father. Additional 15 florins annually.

Mother Hildegard[2]

AD March 1481

Sister Cecilia

Daughter of the Welser family of Augsburg[3]. Named Adelheit. She is wise and learned in Latin and French. 200 florins given by the family before her arrival. Additional promise of 20 florins annually.

AD August 1505

Sister Gertrude

Named Metze[4] Huberyn, born in the Variscan Court[5]. Minimal proficiency in Latin. Kind and knowledgeable about herbal medicine. Most knowledge passed down by her father, an apothecary, who donated six florins to the monastery.

Sister[6] Matilda, 17 years old

From Kempten[7], named Matilda. Moderately proficient in Latin. Calm, disciplined. Daughter of a Frisian merchant who donated ten florins and a large quantity of ultramarine pigment for the Scriptorium’s use.

Mittenwald Ascetarium, May 1515 to September 1515[8]

Sister Illuminata

Named Angelina, from the noble Capocci[9] family of Perugia, who were close to Abbot Rudolf[10]. Extremely learned in Latin as well as French and Germanic languages[11]. Restrained[12], sensible, and perceptive. The Capocci family donated 50 florins before her arrival, with an additional promise of 20 florins annually.

1507

Mother Cecilia, Prioress

February AD 1510

Sister Sophia

Born to the Hafner family in Birgitz. No knowledge of Latin but gentle and reverent. Parents are humble paupers. Three sacks of flour donated.

AD 1512

Sister Lijsbet, 34 years old

Born in Dutch Trecht[13], from the Hack Woutersen marriage[14]. Moderately proficient in Latin but proficient in Saxon. Hardworking and pious. Merchant parents. She has long been connected to Kiersau through her mother’s family, the Kaufmanns of Rothenburg ob der Tauer. They gave 12 florins, with an additional promise of two florins annually.

AD 1514

Sister Margarete

From the Auer family in Krimml. Mostly blind due to glaucoma. Can see colours. Moderately proficient in Latin. The daughter of wealthy peasants who each donated bags of wool and pastureland in Krimml.

AD 1515

Sister Zdena

The third daughter of the Rožmberk family of Tábor[15]. Very learned and proficient in Latin. The Rožmberks paid 100 florins before her arrival, with an additional promise of 30 florins annually.

---

[1] In the original text, the year is written as MCCCCLVIIII. Typically this would be written as MCDLIX, in accordance with subtractive notation (i.e. how we normally write Roman numerals), but there are historical examples of additive notation sometimes being used, for some reason – sometimes both would be used interchangeably in the same document, or even the same number.

[2] This entry likely documents Hildegard’s promotion as opposed to there being two Hildegards in the abbey, as there’s no other information included and the same is done for Sister, later Mother Cecilia below.

[3] The Latin here is originally pretty clunky and obscure (“Welser daughter of the Augsburg Vindelici”); Andreas explicitly mentions Cecilia’s family as well (and telegraphs other important information for the player this way). The Welsers were a German merchant family that rose to prominence in the 16th century as financiers for the Habsburgs along with another family, the Fuggers. They accumulated their wealth mainly through trade and the German colonisation of the Americas, including enslaved labour, so. Yikes!

The Vindelici were a Gallic people based in present-day Augsburg; I don’t actually know if the Welsers themselves were descended from them, but I’d assume so, given that the region is correct.

[4] Diminutive form of Mechthild.

[5] The contemporary name for Hof, believed at the time to be the seat of the Varisci/Narisci people.

[6] Sister Matilda is an oblate, as are Lijsbet and Magarete. Oblates aren’t professed monks or nuns, and so are technically part of the laity, but have associated themselves with a monastic community. They make formal promises – either annually or for life, depending on their affiliated monastery – to follow the Rule of the Order; as a result, they’re considered an extended part of the monastic community.

[7] I initially was stumped by this word and thought it referred to Matilda’s occupation in the abbey as cellarer, but then remembered Andreas reads she’s from Kempten, the old Latin name for which is, indeed, Cambodunum.

[8] Matilda’s age is either current in 1518, which would’ve meant she was 14 when Lorenz Rothvogel attacked her, or her record was retroactively updated to reflect her leave in 1515, making her 20+. Unfortunately, I think both are equally plausible, though being in her 20s would mean her relationship with Brother Wojslav, who imo appears to be older, has (slightly) less of an age gap.

[9] A quick search reveals the real-life Capocci were mostly associated with Viterbo, which is not Perugia lol.

[10] Another clunker originally.

[11] Theodiscus was the contemporary term referring to West Germanic languages; it comes from a Germanic adjective meaning ‘of the people.’ Since Latin was the language of science and religion, theodiscus was its opposite, i.e. the language spoken by the people.

[12] Retinēre very broadly means ‘to keep or hold back’ and so usually gets translated as either ‘to restrain’ or ‘to uphold.’ In describing a person, it can suggest any number of things: literally, physically restrained, or emotionally restrained, as in temperate or even repressed; someone who is steadfast and firm, or simply just is intelligent – as in, literally retains information well. Illuminata is all of these things, but I think ‘restrained’ suits her most compared to, say, tenacious.

[13] Utrecht. The city takes its name from the Roman fort Traiectum on the Rhine.

[14] Imma be real with you chief, other than Hack and Woutersen both being Dutch names, I have no fucking clue what this references – if anything – and I’ve found nothing that would help shed some light on it, either.

[15] The Rožmberk (Rosenberg) family was one of, if not the most powerful noble family in Bohemia from the 13th century until the early 17th century. Zdena is RICH rich, but her story is also pretty sad; it’s little wonder she’s Like That.

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

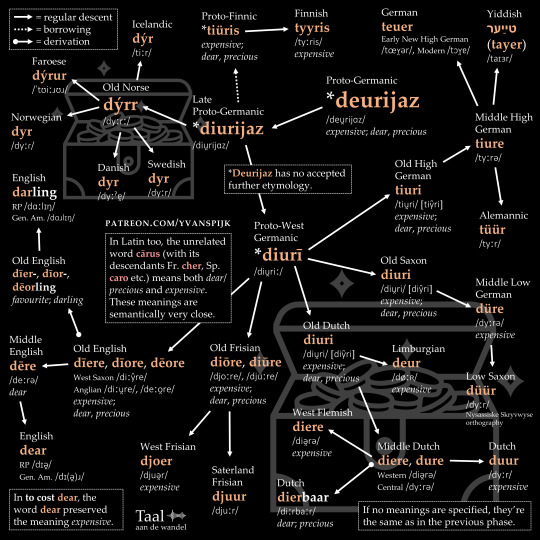

Dear means 'valued; precious; beloved'. However, in certain expressions it also means 'expensive', such as in to cost dear. This meaning, inherited from Proto-Germanic, became dominant in cognates of dear, such as Dutch duur, German teuer, and Swedish dyr. The infographic tells you the whole story.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#dutch#german#low saxon#frisian#old frisian#old saxon#old high german#old english#old dutch#middle high german#middle dutch#middle english#middle low german#lingblr#proto-germanic#proto-west germanic#yiddish#west flemish#limburgian#saterland frisian#faroese#icelandic#norwegian#swedish#danish

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonus post: second Merseburg spell - song lyrics

Phol ende uuodan

Phol and Wodan (Odin)

uuorun zi holza

were in the woods

du uuart demo balderes uolon

sin uuoz birenkict

Than Balder’s foal hurt his foot

-

thu biguol en sinhtgunt

Then Sinthgunt sang

sunna era suister

Sunna her sister

thu biguol en friia

Then Friia (Freya) sang

uolla era suister

Volla her sister

thu biguol en uuodan,

Then sang Wodan

so he uuola conda

So he well could

-

sose benrenki

Like bone-sprain

sose bluotrenki

Like blood-sprain

sose lidirenki

So joint-sprain

ben zi bena

Bone to bone

bluot zi bluoda

Blood to blood

lid zi geliden

Joint to joints

sose gelimida sin

Let them be glued

Explanation post

Merseburger Domstiftbibliothek, codex 136, f85r

#merovingian#viking archaeology#frankish#viking mythology#archaeology#field archaeology#germanic mythology#norse mythology#carolingian#charlemagne#frisian#vikings#viking#field archaeologist#history#linguistics#Merseburg#german mythology#old high German#German linguistics#heilung#germanic archaeology#anglo saxon

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A look at the etymology of the "arithmonyms" from the Locked Tomb series by Tamsyn Muir, arranged by difficulty level.

Easy:

-Deuteros = Ancient Greek δεύτερος (deúteros) "second"

-Dve = Pan-Slavic две/dvě "two"

-Tettares = Ancient Greek (Attic) τέττᾰρες (téttares) "four"

-Chatur = Sanskrit चतुर् (catur) "four"

-Pent = Ancient Greek πέντε (pénte) "five"

-Quinque = Latin quīnque "five"

-Sextus = Latin sextus "sixth"

-Hect = Ancient Greek ἕκτος (héktos) "sixth"

-Sex = Latin sex "six"

-Septimus = Latin septimus "seventh"

-Asht = Sanskrit अष्ट (aṣṭa) "eight"

-Oct = Latin octō "eight" or Ancient greek ὀκτώ (oktṓ) "eight"

-Nav = Sanskrit नव (nava) "nine"

Intermediate:

-Dyas = Ancient Greek (late medieval pronunciation) δῠᾰ́ς (duás) "the number two, couple, pair, diad"

-Tern = Latin ternī "three each, three at a time"

-Trinit = Latin trīnitās "the number three, triad, trinity"

-Tetra = Ancient Greek τετρᾰ́ς (tetrás) "the number four, the fourth day", or τετρα- (tetra-), prefixed form of τέττᾰρες (téttares) "four"

-Quinn = Latin quīnī "five each, five at a time", or quīn-, prefixed form of quīnque "five"

-Shodash = Sanskrit षोडश (ṣoḍaśa) "sixteen"

-Ebdoma = Ancient Greek (Koine pronunciation) ἑβδομάς (hebdomás) "a group of seven"

-Nonagesimus = Latin nōnāgēsimus "ninetieth"

-Novenarius = Latin novēnārius "containing or consisting of nine things"

-Novenary = Latin novēnārius (see above)

Advanced:

-Tridentarius = Neo-Latin tridēntārius "like a trident", from Latin tridēns "three teeth"

-Zeta = Sixth letter of the Greek Alphabet (although in Ancient Greek numerals it actually represents the number 7, because the original sixth letter was the now disused digamma)

-Heptane = Neo-Greek-Latin compound heptane, "saturated aliphatic hydrocarbon C7H16" (more literally "pertaining to the number seven, seven-like")

-Nonius = Latin Nōnius, a first name derived from the Nōnia plebeian family, ultimately from nōnus "ninth"

-Nova = Latin novem "nine" and/or nova "new" (it's been suggested that the Proto-Indo-European root *h₁néwn̥ "nine" is derived from the root *néwos "new")

Expert:

-Octakiseron = Ancient Greek ὀκτᾰ́κῐς (oktákis) "eight times" + unclear suffix, could have been constructed by analogy with -τερον (-teron, as in δεύτερον (deúteron) "second") and -μερον (-meron, as in ἑξαήμερον (hexaḗmeron) "six days"); alternatively based on or reinforced by the French diminutive suffix -eron, an extension of the diminutive -on (itself a merger of several Latin and Frankish suffixes), built by analogy with words like quarteron "quadroon" (from quartier "quarter, district" + -on); yet another possibility is Ancient Greek εἴρων (eírōn) "one who says less than they think, dissembler, pretender"

-Noniusvianus = not clear, perhaps a portmenteau of Latin Nōnius (see above) and noviēs "nine times", with an adjectival ending -(i)ānus.

-Nigenad = perhaps based on Proto-West Germanic *nigundō "ninth" (variant of the more common *neundō), or one of its descendants (Dutch negende, Middle English nyghend, West Frisian njoggende…); possibly reinforced by Old English nigonfeald "ninefold"

#the locked tomb#gideon the ninth#harrow the ninth#nona the ninth#arithmonym#etymology#tamsyn muir#linguistics#latin#greek#sanskrit#numbers#germanic#indo european#slavic#worldbuilding

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Play-By-Blog #0: The Isle by Luke Gearing

Let's try something out. I am going to do weekly play-by-post style posts here on Tumblr where you, my dear readers, get to act as my players via polls. I'll roll dice and act as a referee as needed, but the core choices will be up to you! Think of it as a choose-your-own-adventure blog but with a bit more TTRPG backend on my part. Let's see how it goes! If you are interested in this, please vote in the poll below!

I'll be running Luke Gearing's The Isle which is wonderfully written, mysterious, strange, and honestly quite grotesque so be ready for a wild ride!

The Isle is tiny, a mere 40 acres of forbidding rock and low grasses. Seen from the sea, the monastery buildings stand adjacent to the peak of the isle, lit by a fire atop a tower. The monks never let the fire go out.

Cliffs rise above the bitter sea, mauled by waves and weather. Fallen stones jut like Frisian horses, big enough to skewer whales. The abbot knows this, because he has seen it.

First, character creation! We'll be sticking to some version of Jared Sinclair's The Vanilla Game (a streamlined old DnD-like core this adventure was written for). The biggest decision is as follows:

After this poll expires, I'll roll up a character randomly for you all to collectively inhabit as we venture deep into the dirty depths of The Isle, starting next week!

EDIT: Play-By-Blog #1 can be found HERE!

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like finding words where you go "I wonder what the etymology on this is" and as far back as the reconstructions manage, the word means the same thing.

Like, "horse" derives from PIE *ḱr̥sós (“vehicle”), from PIE *ḱers- (“to run”). So somewhere in the record, someone saw a running thing and said "I could ride that". Or "squirrel" comes from Greek σκίουρος (skíouros) "shadow-tail"

In contrast, you have "cow":*

From Middle English cou, cu, from Old English cū (“cow”), from Proto-West Germanic *kū, from Proto-Germanic *kūz (“cow”), from Proto-Indo-European *gʷṓws (“cow”).

So as far back as we can tell, our ancestor saw a cow and went "yup, that's a cow".

Some of the same things happen for basic words like "fire", "water", "sun" (but not "sky", which seems to go back and forth with the meaning of "cloud"). Which makes sense. Super basic words are most likely to be preserved. It's just interesting to see which ones ended up getting Darkmok'd along the way.

*The entire Indo-European language family is in agreement that, yes, that is a cow.

Cognate with Sanskrit गो (go), Ancient Greek βοῦς (boûs), Persian گاو (gâv)), Latvian govs (“cow”), Proto-Slavic *govędo (Serbo-Croatian govedo, Russian говядина (govjadina) ("beef")), Scots coo (“cow”), North Frisian ko, kø (“cow”), West Frisian ko (“cow”), Dutch koe (“cow”), Low German Koh, Koo, Kau (“cow”), German Kuh (“cow”), Swedish ko (“cow”), Norwegian ku (“cow”), Icelandic kýr (“cow”), Latin bōs (“ox, bull, cow”), Armenian կով (kov, “cow”).

The Sumerian word is also close enough that linguists think it is related. But nobody is entirely sure which direction the borrowing would have gone (from the Sumerian language to an early Proto-Indo-European, or the other way around).

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

More horses for the card series!

[ID: A set of four illustrations featuring horses as follows: first one is of a grey horse with very long flowy mane whisked up by wind overlooking a steamy cauldron out of which two golden birds made out of smoke fly out. The background is blue and various colorful particles float about.

Second is a black Frisian horse jumping down a discharge of lightning. The background is a mass of stormy clouds in shades of grey, blue and purple and there are droplets on the edges of picture the way they would appear on a window during rain.

Third is of an old bay warrior horse still dressed in armor as he overlooks the fallen head of a statue depicting a hero of myth. It is midday; there are fluffy clouds and pieces of other ruins in the background.

And last is of a robust white stallion with long mane whisked up towards the sky as he jumps around on a lush, green hill where further in the background there's ruins of stone columns.]

417 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Are the Branches of Old Norse?

What Are the Branches of Old Norse?

Written by Dyami Millarson

Old Norse or Old Scandinavian is classified as North Germanic, which is distinct from West Germanic and East Germanic. Gothic belongs to East Germanic. East Germanic went extinct with Gothic in the past and East Germanic is being revived Gothic in the present. West Germanic includes English and Scottish, the Frisian languages, Luxembourgish, Dutch, German, and Swiss…

View On WordPress

#dialects are unequal#Fårö Gutnish#Fårögotländska#Frisian languages#Gotlandic#Gutnish#Insular Gutnish#languages are equal#Lau Gutnish#Laugotländska#Mainland Gutnish#Modern North Germanic languages#North Germanic#Old East Norse#Old Gutnish#Old Nordic#Old Norse#Old North Germanic#Old Scandinavian#Old West Norse

0 notes