#john updike why did you do this to me

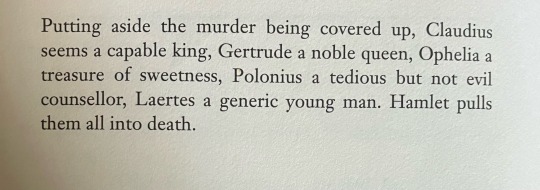

Text

John Updike, "Afterword", Gertrude and Claudius (2000)

Okay. Okay, yeah, I'm fine. Mmhm. I'm fine. This is fine. "Hamlet pulls them all into death. Coolcoolcoolcoolcoolcool. Cool. I am,,,,,

Fine.

#gertrude and claudius#john updike why did you do this to me#it's tragedy enjoyer hours lads#seriously though if you haven't read this book i highly recommend it#it makes some cool choices wrt to different names for the characters#also it understands hamlet (the guy) on a level that few other adaptations do#my guy billy shakes#hamlet

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

ART ISN'T SUPPOSED TO MAKE YOU COMFORTABLE

By Jen Silverman (NY Times)

(Mx. Silverman is a playwright and the author, most recently, of the novel “There’s Going to Be Trouble.”)

When I was in college, I came across “The Sea and Poison,” a 1950s novel by Shusaku Endo. It tells the story of a doctor in postwar Japan who, as an intern years earlier, participated in a vivisection experiment on an American prisoner. Endo’s lens on the story is not the easiest one, ethically speaking; he doesn’t dwell on the suffering of the victim. Instead, he chooses to explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators.

When I say “humanity” I mean their confusion, self-justifications and willingness to lie to themselves. Atrocity doesn’t just come out of evil, Endo was saying, it emerges from self-interest, timidity, apathy and the desire for status. His novel showed me how, in the right crucible of social pressures, I, too, might delude myself into making a choice from which an atrocity results. Perhaps this is why the book has haunted me for nearly two decades, such that I’ve read it multiple times.

I was reminded of that novel at 2 o’clock in the morning recently as I scrolled through a social media account dedicated to collecting angry reader reviews. My attention was caught by someone named Nathan, whose take on “Paradise Lost” was: “Milton was a fascist turd.” But it was another reader, Ryan, who reeled me in with his response to John Updike’s “Rabbit, Run”: “This book made me oppose free speech.” From there, I hit the bank of “Lolita” reviews: Readers were appalled, frustrated, infuriated. What a disgusting man! How could Vladimir Nabokov have been permitted to write this book? Who let authors write such immoral, perverse characters anyway?

I was cackling as I scrolled but soon a realization struck me. Here on my screen was the distillation of a peculiar American illness: namely, that we have a profound and dangerous inclination to confuse art with moral instruction, and vice versa.

As someone who was born in the States but partially raised in a series of other countries, I’ve always found the sheer uncompromising force of American morality to be mesmerizing and terrifying. Despite our plurality of influences and beliefs, our national character seems inescapably informed by an Old Testament relationship to the notions of good and evil. This powerful construct infuses everything from our advertising campaigns to our political ones — and has now filtered into, and shifted, the function of our artistic works.

Maybe it’s because our political discourse swings between deranged and abhorrent on a daily basis and we would like to combat our feelings of powerlessness by insisting on moral simplicity in the stories we tell and receive. Or maybe it’s because many of the transgressions that flew under the radar in previous generations — acts of misogyny, racism and homophobia; abuses of power both macro and micro — are now being called out directly. We’re so intoxicated by openly naming these ills that we have begun operating under the misconception that to acknowledge each other’s complexity, in our communities as well as in our art, is to condone each other’s cruelties.

When I work with younger writers, I am frequently amazed by how quickly peer feedback sessions turn into a process of identifying which characters did or said insensitive things. Sometimes the writers rush to defend the character, but often they apologize shamefacedly for their own blind spot, and the discussion swerves into how to fix the morals of the piece. The suggestion that the values of a character can be neither the values of the writer nor the entire point of the piece seems more and more surprising — and apt to trigger discomfort.

While I typically share the progressive political views of my students, I’m troubled by their concern for righteousness over complexity. They do not want to be seen representing any values they do not personally hold. The result is that, in a moment in which our world has never felt so fast-changing and bewildering, our stories are getting simpler, less nuanced and less able to engage with the realities through which we’re living.

I can’t blame younger writers for believing that it is their job to convey a strenuously correct public morality. This same expectation filters into all the modes in which I work: novels, theater, TV and film. The demands of Internet Nathan and Internet Ryan — and the anxieties of my mentees — are not so different from those of the industry gatekeepers who work in the no-man’s land between art and money and whose job it is to strip stories of anything that could be ethically murky.

I have worked in TV writers’ rooms where “likability notes” came from on high as soon as a complex character was on the page — particularly when the character was female. Concern about her likability was most often a concern about her morals: Could she be perceived as promiscuous? Selfish? Aggressive? Was she a bad girlfriend or a bad wife? How quickly could she be rehabilitated into a model citizen for the viewers?

TV is not alone in this. A director I’m working with recently pitched our screenplay to a studio. When the executives passed, they told our team it was because the characters were too morally ambiguous and they’d been tasked with seeking material wherein the lesson was clear, so as not to unsettle their customer base. What they did not say, but did not need to, is that in the absence of adequate federal arts funding, American art is tied to the marketplace. Money is tight, and many corporations do not want to pay for stories that viewers might object to if they can buy something that plays blandly in the background of our lives.

But what art offers us is crucial precisely because it is not a bland backdrop or a platform for simple directives. Our books, plays, films and TV shows can do the most for us when they don’t serve as moral instruction manuals but allow us to glimpse our own hidden capacities, the slippery social contracts inside which we function, and the contradictions we all contain.

We need more narratives that tell us the truth about how complex our world is. We need stories that help us name and accept paradoxes, not ones that erase or ignore them. After all, our experience of living in communities with one another is often much more fluid and changeable than it is rigidly black and white. We have the audiences that we cultivate, and the more we cultivate audiences who believe that the job of art is to instruct instead of investigate, to judge instead of question, to seek easy clarity instead of holding multiple uncertainties, the more we will find ourselves inside a culture defined by rigidity, knee-jerk judgments and incuriosity. In our hair-trigger world of condemnation, division and isolation, art — not moralizing — has never been more crucial.

#antis#purity culture#purity wank#why I write fanfic#because I can't publish my morally ambiguous OCs

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

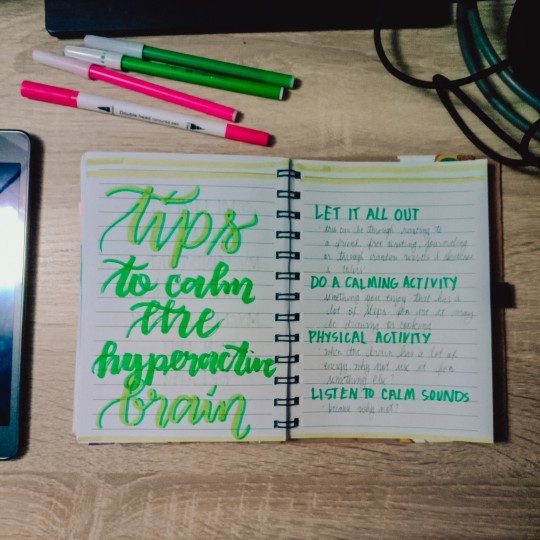

It's been a while! I'm trying to enjoy the holidays but my academic responsibilities are weighing me down. 😣🥲

Did these two spreads because I wanted something colorful to cheer me up. The notebook I used is relatively cheap so the markers can bleed through sometimes but I still like using it. It's cheap so I won't have second thoughts using it for various spreads and for trying something new.

1st Image text:

What art offers is space, a certain breathing room for the spirit - John Updike

Sometimes I have a lot on my mind that I have to remind myself to slow down and breathe

2nd Image text:

Tips to calm the hyperactive brain

Let it all out - by ranting to a friend, free writing, journaling or through random words, sketches and colors

Do a calming activity - something you enjoy that has a lot of steps, for me it's cooking or drawing

Physical Activity - when the brain has a lot of stored energy, why not use it for something else?

Listen to calm sounds - because why not?

#art journal#journal spread#notebook#noteblr#journaling#quotes#journal entry#journal#pink#soft pink#green#calligraphy#lettering#adhd hyperactive#tips and tricks#life tips#amethysworld

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Isn’t Supposed to Make You Comfortable

By Jen Silverman

When I was in college, I came across “The Sea and Poison,” a 1950s novel by Shusaku Endo. It tells the story of a doctor in postwar Japan who, as an intern years earlier, participated in a vivisection experiment on an American prisoner. Endo’s lens on the story is not the easiest one, ethically speaking; he doesn’t dwell on the suffering of the victim. Instead, he chooses to explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators.

When I say “humanity” I mean their confusion, self-justifications and willingness to lie to themselves. Atrocity doesn’t just come out of evil, Endo was saying, it emerges from self-interest, timidity, apathy and the desire for status. His novel showed me how, in the right crucible of social pressures, I, too, might delude myself into making a choice from which an atrocity results. Perhaps this is why the book has haunted me for nearly two decades, such that I’ve read it multiple times.

I was reminded of that novel at 2 o’clock in the morning recently as I scrolled through a social media account dedicated to collecting angry reader reviews. My attention was caught by someone named Nathan, whose take on “Paradise Lost” was: “Milton was a fascist turd.” But it was another reader, Ryan, who reeled me in with his response to John Updike’s “Rabbit, Run”: “This book made me oppose free speech.” From there, I hit the bank of “Lolita” reviews: Readers were appalled, frustrated, infuriated. What a disgusting man! How could Vladimir Nabokov have been permitted to write this book? Who let authors write such immoral, perverse characters anyway?

I was cackling as I scrolled but soon a realization struck me. Here on my screen was the distillation of a peculiar American illness: namely, that we have a profound and dangerous inclination to confuse art with moral instruction, and vice versa.

As someone who was born in the States but partially raised in a series of other countries, I’ve always found the sheer uncompromising force of American morality to be mesmerizing and terrifying. Despite our plurality of influences and beliefs, our national character seems inescapably informed by an Old Testament relationship to the notions of good and evil. This powerful construct infuses everything from our advertising campaigns to our political ones — and has now filtered into, and shifted, the function of our artistic works.

Maybe it’s because our political discourse swings between deranged and abhorrent on a daily basis and we would like to combat our feelings of powerlessness by insisting on moral simplicity in the stories we tell and receive. Or maybe it’s because many of the transgressions that flew under the radar in previous generations — acts of misogyny, racism and homophobia; abuses of power both macro and micro — are now being called out directly. We’re so intoxicated by openly naming these ills that we have begun operating under the misconception that to acknowledge each other’s complexity, in our communities as well as in our art, is to condone each other’s cruelties.

When I work with younger writers, I am frequently amazed by how quickly peer feedback sessions turn into a process of identifying which characters did or said insensitive things. Sometimes the writers rush to defend the character, but often they apologize shamefacedly for their own blind spot, and the discussion swerves into how to fix the morals of the piece. The suggestion that the values of a character can be neither the values of the writer nor the entire point of the piece seems more and more surprising — and apt to trigger discomfort.

While I typically share the progressive political views of my students, I’m troubled by their concern for righteousness over complexity. They do not want to be seen representing any values they do not personally hold. The result is that, in a moment in which our world has never felt so fast-changing and bewildering, our stories are getting simpler, less nuanced and less able to engage with the realities through which we’re living.

I can’t blame younger writers for believing that it is their job to convey a strenuously correct public morality. This same expectation filters into all the modes in which I work: novels, theater, TV and film. The demands of Internet Nathan and Internet Ryan — and the anxieties of my mentees — are not so different from those of the industry gatekeepers who work in the no-man’s land between art and money and whose job it is to strip stories of anything that could be ethically murky.

I have worked in TV writers’ rooms where “likability notes” came from on high as soon as a complex character was on the page — particularly when the character was female. Concern about her likability was most often a concern about her morals: Could she be perceived as promiscuous? Selfish? Aggressive? Was she a bad girlfriend or a bad wife? How quickly could she be rehabilitated into a model citizen for the viewers?

TV is not alone in this. A director I’m working with recently pitched our screenplay to a studio. When the executives passed, they told our team it was because the characters were too morally ambiguous and they’d been tasked with seeking material wherein the lesson was clear, so as not to unsettle their customer base. What they did not say, but did not need to, is that in the absence of adequate federal arts funding, American art is tied to the marketplace. Money is tight, and many corporations do not want to pay for stories that viewers might object to if they can buy something that plays blandly in the background of our lives.

But what art offers us is crucial precisely because it is not a bland backdrop or a platform for simple directives. Our books, plays, films and TV shows can do the most for us when they don’t serve as moral instruction manuals but allow us to glimpse our own hidden capacities, the slippery social contracts inside which we function, and the contradictions we all contain.

We need more narratives that tell us the truth about how complex our world is. We need stories that help us name and accept paradoxes, not ones that erase or ignore them. After all, our experience of living in communities with one another is often much more fluid and changeable than it is rigidly black and white. We have the audiences that we cultivate, and the more we cultivate audiences who believe that the job of art is to instruct instead of investigate, to judge instead of question, to seek easy clarity instead of holding multiple uncertainties, the more we will find ourselves inside a culture defined by rigidity, knee-jerk judgments and incuriosity. In our hair-trigger world of condemnation, division and isolation, art — not moralizing — has never been more crucial.

source

0 notes

Text

Love doesn't hurt

In honor of Valentine's Day this week, I am writing about love all week. I especially think we need more love in this world. See, we throw the word love around a lot; it is probably the most overused and underrated word in the universe. Sometimes, I wonder if people even know what love is.

What is love? I'm talking about true love, agape love, and love without boundaries and without restrictions.

Did you know that love is mentioned in the bible 310 times? Love one another, love thy brother, love thy neighbor and there is a reason for this. The bible says,

"Love is patient; love is kind. It does not envy; it does not boast; it is not proud. It does not dishonor others; it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, and it keeps no record of wrongs."

Yet we do none of that when it comes to loving someone. We get mad and keep grudges; we cut them out of our lives for misunderstandings. We say terrible things; we cut them to the core. Some people even kill with their words as words can and will change who a person is.

So many people are so about themselves, their control, or what they can get out of it. It's all about them. Trust me, I've dated and even married a man like that. Where I gave 100%, and they barely gave 10%.

But even knowing all I know, even after all the heart breaks, even after all of that, I still believe in love. I will always be Tinkerbell in my soul. Always believing in happily ever after and that my Prince Charming is out there, somewhere.

I believe in a universe that we can all love one another despite our color, our religion, our political beliefs, or sexual orientation. That we all bleed red, and our only purpose here is to love one another.

I wish for a world where you uplift your sisters or help out your brothers. Where you're kind to strangers, and you have a giving heart to everyone. Yes, to most of you, that sounds like a fairy tale, but I know that I am going to make a difference in this world before I die. We all can make a difference. I will do it by one kind deed, one smile, one kind word. I am going to leave my legacy that I loved everyone.

I even love and pray for my enemies. Yes, that was a hard place for me to get to, but if we can not forgive them, then we can not move on. I want to move on. My only goal is to one day hear, "Good job, my child, good job."

We get one chance, one life here, why spend it bitter and angry. Why waste precious energy on hatred, on unkind words? I have no time for that; I chose to spend whatever time God is going to give me here on spreading as much love and joy as I possibly can. I want the people closest to me to know every day that I love them and not just with my words but with my actions as well. I never hang up the phone or say goodbye to the people I love without telling them I love them.

I write this blog to uplift others, to be that shining light in their dark times, to let them know that there is someone who cares about them and knows what they are going through.

Yes, I will always see the best in people, no matter how many times I may be hurt. I will love unconditionally and with a pure heart. I will keep doing me, the me God birthed me to be.

So today my friends, I will leave you with some famous quotes about love....

'Kindness in words creates confidence. Kindness in thinking creates profundity. Kindness in giving creates love."

Lao Tzu

'Love’s greatest gift is its ability to make everything it touches sacred."

Barbara De Angelis

"Love is never lost. If not reciprocated, it will flow back and soften and purify the heart."

Washington Irving

"We are most alive when we're in love."

John Updike

"Love recognizes no barriers"

Maya Angelou

"Love yourself first, and everything falls into line."

Lucille Ba

Remember, love is a many splendid thing; love is kind, love is what makes the world go around....

Love does not hurt…

Be the love you want to see.

"Be the change you want to see”

@TreadmillTreats

0 notes

Note

Could you do books that the scps might read?

Books that the SCPs might read

SCP 035

Anna and the French Kiss by Stephanie Perkins

Anna is shipped off to boarding school in Paris where she meets the super-charming Etienne, and that's when things get interesting. I was a squealing, giggly, mush-fest all the while through reading this book. Stephanie Perkins knows just how to turn a seemingly ordinary love story into an unputdownable read.

SCP 040

Your Brain Needs a Hug: Life, Love, Mental Health, and Sandwiches

Just the title of this book by Rae Earl makes us feel a little lighter. And we don’t know about you, but our brains could definitely use a hug right now. While the book is geared towards teens, we found Earl’s advice to be relevant for all ages — particularly for anyone who struggles with depression, anxiety, social media addiction, and self-esteem issues. TBH, pretty much anyone can benefit from this book!

SCP 049

And the Mountains Echoed by Khaled Hosseini

And the Mountains Echoed is such an amazing and heartwarming read. It's about a pair of siblings that fate cruelly separates and then finally reunites. A must-read for its simple yet gripping narration and amiable characters.

SCP 049-j

The Red Notebook by Antoine Laurain

This is a French romance novella, and basically a love letter to book lovers. There's mystery, romance, and some of the most beautifully crafted sentences and paragraphs I have ever read. The ending is so sweet, even though you wonder how you ever got there so soon.

SCP 053

Lulu and the Rabbit Next Door by Hilary McKay

Lulu and her cousin help their neighbor Arthur learn to love and care for his (neglected) rabbit. She doesn’t want her neighbor to feel bad so she writes the rabbit little notes with helpful gifts signed from her own pet rabbit named Thumper. It’s a kind way to show Arthur how to take care of his new pet

SCP 073

HumanKind: Changing the World One Small Act At a Time

Looking for heart-warming stories of kindness and compassion? HumanKind by Brad Aronson was made for you. But the book isn’t only full of uplifting stories that will move you to happy tears, it’s also packed with practical and actionable tips for how to be kinder in your everyday. One thing is for sure: after you put this book down, you’ll feel inspired to do something nice for someone else. And because of that, we think this is one of the best books on the planet!

SCP 076

Do Unto Animals

We absolutely DEVOURED this book by Tracey Stewart. Whether you’re looking for tips on how to better understand skunks and squirrels or read your pet’s body language, every page is full of compassionate wisdom about to treat animals in a way that they deserve. Also, the illustrations are absolutely beautiful — we nearly wanted to pet the pages because the animal drawings were so lovable.

SCP 079

Walden (Henry David Thoreau)

With the outdoorsman renaissance happening as we speak, it is nice to look back at one of the books that probably started it. Walden isn’t the bore you read back in middle school, it takes time to appreciate like a nice bottle of red. Thoreau’s masterpiece tackles so much while quietly nudging your brain into activity. It also makes you want to build a cabin

SCP 096

Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

Told from the perspective of the horse, this story is so beautifully written that it's easy to get lost in it's pages. I laughed and cried, as did my daughter when she read it.

SCP 105

Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury

Warm and fuzzy the whole way through, Dandelion Wine is by far the best story to make you feel good. Though I'm not the correct age to directly relate to the young adult story, I still felt the warm summer days and the wonder of it all.

SCP 106

Catch-22 – Joseph Heller

“War is hell,” is the old adage we all know, but Catch-22 looks to modify that a bit. Instead, war becomes super goddamn weird. The book follows a bomber squadron in the Second World War whose collective sanity is slowly being eroded by whatever passes for power. Throughout it all, the main character keeps trying to prove himself insane enough to be kicked out of the Navy, which is precisely why he can’t

be kicked out. Which is a catch 22 and yes, this is where the phrase comes from. It’s a great extrapolation of quirks and idiosyncrasies we see in day to day life, only this time, they’re affecting war

SCP 134

(I know she don't have eyes . But there is a books for blind people)

A Mango-Shaped Space by Wendy Mass

A Mango-Shaped Space is about a 13-year-old girl with synesthesia (she can see, taste, and hear colors) and her journey in getting a diagnosis and accepting herself and all her differences. It's sort of a coming-of-age story, too.

As someone with multiple chronic illnesses who has gone through the same process at the same age, this really was an incredible reading experience. One of my favorite quotes is "We all do the best we can, trying to keep all the balls in the air at once." I recommend it to everyone.

SCP 173

Rabbit, Run (John Updike)

The greatest mid-life crisis novel of all time doesn’t actually deal with a mid-life crisis at all. Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom is 26 when he decides to leave his wife and son for a new life. Of course, what that new life is, and what exactly he wants out of it isn’t clear to the reader or to Rabbit himself. It will strike a cord with all men who struggle with the idea of settling down.

SCP 239

The Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling

SCP 682

THE WOLF AND THE WATCHMAN BY NIKLAS NATT OCH DAG

If you're the kind of person that can't get enough of Scandi noir films, TV shows and literature, then Niklas Natt och Dag's The Wolf And The Watchman should be next on your reading list. Set in 18th-century Stockholm, this tale is as dark as it gets, following the titular watchman and a detective as they hunt down the killer behind a dismembered corpse that appears in a local pond. As gruesome as it is gripping, it's the perfect literary companion as the nights get longer and increasingly eerie.

SCP 847

The Case Against Satan by Ray Russell

Two priests are called in to examine a girl who might be possessed by the devil. The Exorcist, right? Nope, it’s Ray Russell‘s The Case Against Satan, a novel of theological horror that beat William Peter Blatty’s book to print by eight years. The Case Against Satan is as much the story of a crisis of faith as it is a supernatural tale, and readers looking for a nuanced take on both should give it a try

SCP 953

THE PILLOW BOOK BY SEI SHŌNAGON

If you want to learn a bit more about the Japan of the past – and also, weirdly, all of us in the present – The Pillow Book is a cult classic you should absolutely try. Sei Shōnagon was a lady-in-waiting in the court of Empress Teishi in the year 1000 and here she collects her thoughts and musings about court life. To read a woman more than 1,000 years ago being as philosophical, neurotic and scandalous as anyone is today on social media is a thrill that lasts from the start to the end.

SCP 1678

Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden

Absolutely moving, the struggles Sayuri faces are painted so beautifully by Arthur Golden's masterful craft that you totally empathize with her as she grows and triumphs in a world designed to see her fail. The ultimate conclusion of the novel fills me with such warmth — it's both entirely unexpected and wholeheartedly appreciated.

#scp foundation#scp#scp 035#scp 040#scp 049#scp 049-j#scp 073#scp 076#scp 079#scp 096#scp 105#scp 106#scp 134#scp 173#scp 239#scp 682#scp 847#scp 953#scp 1678#scps#books

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay i googled this question and found the answer on reddit, along with this person's remembrances that could be a john updike short story. title reproduced for accessibility.

"Explain Like I'm 5: Why do some farmers plant crops in big circles, rather than sticking with squares or rectangles? Aren't they losing ~21.5% of crop area?"

u/twelveparsex commented:

area isn't the limiting factor in places they use center pivot irrigation. It may be water, it may be labor, it may be transportation.

u/strange_vagrant commented:

I was in the passanger seat staring out at the farmland. There were long metal bars held up by wheels and anchored somewhere out in the middle of the field. Clearly it was for water but, so odd.

"Wouldn't it only water in a circle? So what, the field is a giant circle?"

"Yeah, I guess," my brother said from the drivers seat.

We were heading to a skydiving site. I've never done it before. I'm not some sorta adrenalin junkie, but I will try anything once. This week it was skydiving.

My brother lamented months back that we should go, we never do anything. We were just wasting away on the back end of my parents' trailer. Life passing us by. So this day was to help us take life back. Grab it by the horns and all that, I guess. Sort of naive but we were.

People ask what it's like, skydiving. I tell them, "it's like scrolling in on the satellite image of Google maps, but with a lot of wind."

As I plummeted through the air, strapped to some 6'7" Scandinavian, I had to focus and learn how to breath again. With that done, I watched the ground. It looked like wall paper.

*I'm thousands of feet above this weird paper image. It's changing slowly, I almost can't even tell it's because I'm getting closer to it. It's just all farmland. Hey, these fields are all circles... wait- so that's how it works, huh? Weird. Seems like a waste of surface area but I guess its easier. I have to remember to tell my brother.*

"Hey, how is it?!" Vlad, or whatever his name was, was shouting at me through the rippling wind and all my silence.

"Yeah. Pretty cool." I shout back. Aw, damn, I hope he doesn't think I don't appreciate him jumping out of a plane for me.

On the ground, my girlfriend waits in the field. I do as Bjorn says, tucking up on the landing. He unhooked me, asking if I had fun.

"Yeah, I'm glad I did that. Thanks." I shake his hand, turn around and peer through the glaring sun.

My girlfriend rushes in, taking a photo. I dont like ohotos of me, but that is a decent one. You can see how uncomfortable those harness are, but despite my calm demeanor, I got a big grin on my face.

In the following years, my brother slaved away at his job, working his way up to earn a great position through sheer force of will. I decided to go to school, again. I married the girl and took a job after graduating at the same company as my brother. I get to travel a lot. Ive eaten donkey, ants, been to the louve, bought weed in Frankfurt from some shady expat, all the fun life experiences I could ask for. Now the girl and I have a daughter. My wife complains she misses her when we go to work. She wants to stay home and cuddle her. At work, everyone asks if I'm related to my brother. He's really well liked there and made a solid living doing what he loves.

Oh, we don't live in my parents' trailer anymore. No, we moved out and on to much better things. That skydiving day marks when we decided a few things that would lead to the lives we have now. I guess it was a bit of a turning point, nieve or not.

Driving past the fields, with my little family in the car, I look out at the long metal bars, drooping across the rigging. That field is a circle. I know that now. I've seen it from the air.

Sorry, maybe that's off topic but that's what I think about whenever I see those things out there.

21 notes

·

View notes

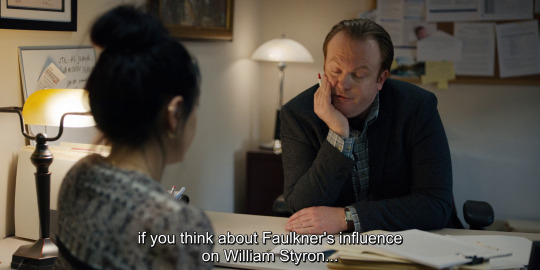

Photo

IT’s been 86 years since I read Sophie’s Choice, and also Faulkner (oh shit that reminds me I need to update the book list--I’ve been in a very weird place lately and need to remind myself I’m allowed to read without writing a review of everything) and so I can’t directly argue with literally anything going on here, but I hate when I feel talked at about literature and what it MUST mean instead of engaging about what it CAN mean.

And I mean, like, the eyes of Dr. TJ Eckleberg are pretty transparent and all, but even when I was writing papers, I wanted to talk about what the possibilities were instead of ask my teacher what the answer was. I did not go into literary analysis to be told my own opinion, and maybe, upon reflection, this is why I have so much trouble with internet lock-step. Hm. Anyway, you may argue, “He might just be advancing his own theory” and I might be onto that IF this wasn’t the guy from the beginning who droned on fucking ENDLESSLY about John Updike and his theory of marriage, and so I KNOW that he’s delivering ANOTHER monologue to a woman, and honestly, this must be her advisor and WHY DO WOMEN FUCK THESE KIND OF MEN???

WHY

WHY

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y’all I might have fucked up a little on my writing assignment. We had to read a horrible piece and then respond to questions about it. I may have let too much sass through before I hit the send button... So anyway, here is my response to "A & P" by John Updike. Enjoy.

I hate this story. I hate everything about it. From the writing style to the narrator, this entire thing rubbed me the wrong way and made my skin crawl. Let me say that I understand why we had to read and analyze this piece. I get it, I really do. But I hate this so much I was actually making audible sounds of annoyance and rolling my eyes the entire time. I am so sorry you had to sit there and read this rant of mine, but if I have to sit here and critically analyze this story, I’m going to take this opportunity to express my thoughts on it.

Now, on to the assignment.

What is different about the day when the story takes place?

The day the story takes place is different because our slack jawed narrator Sammy can’t keep his eyes and opinions under control when three women who are friends enter a store to buy herring snacks. The day this story takes place is different because Sammy decides on that day, despite the fact that he’s done nothing but sexualize and dehumanize these women in his mind, that his boss being equally sexist and embarrassing to the women is the perfect excuse to quit his job. I don’t know if he was trying to be the white knight here and stand up for them in the hopes of getting ‘Queenie’s’ number, but it didn’t work, and so it was just a selfish, self-gratifying, childish display for nothing other than to stroke his own ego. When I say he did it to stroke his own ego, I mean it. The girls didn’t even see his halfhearted display. Sammy didn’t bother to stand up for them when they were around, so the gesture was as meaningless as the opinions Sammy has of women.

What is the main character's underlying problem, and how does the story bring this problem into sharper focus?

Sammy’s underlying problem, as I have stated in the earlier segment, is that he is a sexist, self-absorbed, child. The story brings this into focus by showing the first thing that happens is that Sammy mis-rings a customer because he can’t stop starting at, sexualizing, making assumptions about, and objectifying the three women who came into the store. He then thinks to himself that the customer he’s just double charged is the villain, or a witch, or a harpy, or some other equally sexist and annoying thing despite the fact that he’s the one who made the error, and she simply called him out on this. He even goes into great detail to describe her appearance (as he seems to do with every woman in the story but never the men) and uses the way she looks to justify his assumptions about her. Sammy does this multiple times where he looks at women and makes assumptions about them, from their personalities to their voices, based on nothing but their appearances. He dehumanizes them so often I’m actually half tempted to write to the author and ask if he (the author) even likes women or sees them as humans at all, especially when he says ‘You never know for sure how girls' minds work (do you really think it's a mind in there or just a little buzz like a bee in a glass jar?)’. I digress. Sammy’s underlying problem is that he is a sexist person and lets his mind get so distracted by the women in swimsuits that he can’t even do his job right. He is so self absorbed that he can't even take a moment to think about the consequences of his actions. He just acts without consideration for what his actions mean.

Why is this story in the point of view that it is?

I want to say this story is written this way just to torment me specifically, but then I would be as self-absorbed as Sammy is. I know this story is written this way to show us his adolescent mind, how hypocritical and irrational he is, and how he does not think about the consequences of his actions (and how they may affect his family or his own future). He calls his manager out for making the women blush, but if they were telepaths and were able to hear what Sammy had just been thinking about them, the women would have had the same reaction or even a stronger one to Sammy’s thoughts about them. I can’t figure out if this is an extremely clumsy, off putting, and bizarre attempt to make me, the reader, feel like Sammy is a good person, or if the author did this finally scene ironically to draw attention to how hypocritical Sammy actually is. The story was written in 1961 so I really can’t be sure what the intent of that final scene was. Either way, I don’t care for it.

How is this story different from other stories you've read?

This story is different than others I’ve read because I know there is deeper meaning to the story but I am just so distracted by the sheer amount of sexism that I actually had a hard time ferreting out the deeper meaning. I really did not want to have to reread this story, but I did it because I was pretty sure that a story written by a man in 1961 wasn’t about sexism, and that the author was trying to convey a different message. I very begrudgingly reread this and have concluded that it is supposed to be about societal expectations and deviating from them. The girls are deviating from societal expectations by wearing their swimsuits in the store where Sammy deviates from the expectations set for him by quitting his job without putting in notice even though it could potentially have negative consequences for his family and himself. I would say this story is different from any others I’ve read because of just how annoyed and distracted I was the entire time I was reading it. I think the actual message of the story got buried beneath Sammy’s never-ending, self indulgent observations of his customers, and his thoughts about what 'sheep' they are. This piece did not age well in the fifty years since its publication.

What specific technique(s) would you most readily take from this story and try in your own story?

I really don’t know what I would take from this story to improve my own writing. I’d maybe consider giving my narrator/protagonists more of an opportunity to have internal monologue and thoughts on display for the readers to have at their disposal. I typically don’t go into my protagonist's thoughts in the extreme way this story did. Sammy was an open book from start to finish. I usually keep my character’s thoughts to one or two lines of monologue, and while the content of Sammy’s thoughts were mind numbing to me, it’s not a bad technique to use when trying to build and craft a character. It allows the reader full access with little or no secrets kept between them and the protagonist.

#personal#college#my writing#lord help me I think I done fucked up#but my grade in this class is 100% so I can take a minor hit in my grade to get my very sassy point across

1 note

·

View note

Text

Death Quotes That Will Bring You Instant Calm

There can’t be life without death, and these quotes prove just that.

He is terribly afraid of dying because he hasn’t yet lived. Franz Kafka

Our culture’s zeal for longevity reveals our incredible collective fear of death. Ram Dass

I do not believe that any man fears to be dead, but only the stroke of death. Francis Bacon

Some people are so afraid to die that they never begin to live. Henry Van Dyke

Suppose that a god announced that you were going to die tomorrow “or the day after”. Unless you were a complete coward you wouldn’t kick up a fuss about which day it was – what difference could it make? Now recognize that the difference between years from now and tomorrow is just as small. Marcus Aurelius

Don’t look down on death, but welcome it. It to is one of the things required by nature. Like youth and old age. Like growth and maturity. Like a new set of teeth, a beard, the first gray hair. Like sex and pregnancy and childbirth. Like all the other physical changes at each stage of life, our dissolutions is no different. Marcus Aurelius

The more you transform your life from the material to the spiritual domain, the less you become afraid of death. A person who lives a truly spiritual life has no fear of death. Leo Tolstoy

You know, what’s so dreadful about dying is that you are completely on your own. Vladimir Nabokov (Lolita)

Not only are selves conditional but they die. Each day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all the time? John Updike (Self-Consciousness)

Be sure the safest rule is that we should not dare to live in any scene in which we dare not die. But, once realise what the true object is in life — that it is not pleasure, not knowledge, not even fame itself, ‘that last infirmity of noble minds’ — but that it is the development of character, the rising to a higher, nobler, purer standard, the building-up of the perfect Man — and then, so long as we feel that this is going on, and will (we trust) go on for evermore, death has for us no terror; it is not a shadow, but a light; not an end, but a beginning! Lewis Carroll

Guilt is perhaps the most painful companion to death. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

I believe that fear of life brings a greater fear of death. David Blaine

The typical human behaviour is to seek security and certainty. We fear death because it’s the unknown and nobody can give us answers. Maxime Lagacé

Death anxiety is greater in those who feel they have lived an unfulfilled life. Irvin Yalom

One regret dear world, that I am determined not to have when I am lying on my deathbed is that I did not kiss you enough. Hafiz of Persia

The bitterest tears shed over graves are for words left unsaid and deeds left undone. Harriet Beecher Stowe

Dying is like coming to the end of a long novel – you only regret it if the ride was enjoyable and left you wanting more. Jerome P. Crabb

Many of us crucify ourselves between two thieves – regret for the past and fear of the future. Fulton Oursler

Life will undertake to separate us, and we must each set off in search of our own path, our own destiny or our own way of facing death. Paulo Coelho

People die all the time. Life is a lot more fragile than we think. So you should treat others in a way that leaves no regrets. Fairly, and if possible, sincerely. It’s too easy not to make the effort, then weep and wring your hands after the person dies. Haruki Murakami

If I can see pain in your eyes, then share with me your tears. If I can see joy in your eyes, then share with me your smile. Santosh Kalwar

I think death is equally terrible for everyone. Young people, old people, the good, the bad; it’s always the same. It’s rather fair in its treatment. There’s no such thing as a terrible death, that’s why it’s frightening. Sunako

Do not seek death. But do not fear it either. There cannot be life without death, it is inescapable. Keisei Tagami

It is the unknown we fear when we look upon death and darkness, nothing more. J.K. Rowling (Harry Potter)

If you are a fan of horror, then you need to check out www.ribemedia.com.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How We Grieve: Meghan O’Rourke on the Messiness of Mourning and Learning to Live with Loss

“The people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created.”

John Updike wrote in his memoir, “Each day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all the time?” And yet even if we were to somehow make peace with our own mortality, a primal and soul-shattering fear rips through whenever we think about losing those we love most dearly — a fear that metastasises into all-consuming grief when loss does come. In The Long Goodbye (public library), her magnificent memoir of grieving her mother’s death, Meghan O’Rourke crafts a masterwork of remembrance and reflection woven of extraordinary emotional intelligence. A poet, essayist, literary critic, and one of the youngest editors the New Yorker has ever had, she tells a story that is deeply personal in its details yet richly resonant in its larger humanity, making tangible the messy and often ineffable complexities that anyone who has ever lost a loved one knows all too intimately, all too anguishingly. What makes her writing — her mind, really — particularly enchanting is that she brings to this paralysingly difficult subject a poet’s emotional precision, an essayist’s intellectual expansiveness, and a voracious reader’s gift for apt, exquisitely placed allusions to such luminaries of language and life as Whitman, Longfellow, Tennyson, Swift, and Dickinson (“the supreme poet of grief”).

O’Rourke writes:

“When we are learning the world, we know things we cannot say how we know. When we are relearning the world in the aftermath of a loss, we feel things we had almost forgotten, old things, beneath the seat of reason.

[…]

Nothing prepared me for the loss of my mother. Even knowing that she would die did not prepare me. A mother, after all, is your entry into the world. She is the shell in which you divide and become a life. Waking up in a world without her is like waking up in a world without sky: unimaginable.

[…]

When we talk about love, we go back to the start, to pinpoint the moment of free fall. But this story is the story of an ending, of death, and it has no beginning. A mother is beyond any notion of a beginning. That’s what makes her a mother: you cannot start the story.”

In the days following her mother’s death, as O’Rourke faces the loneliness she anticipated and the sense of being lost that engulfed her unawares, she contemplates the paradoxes of loss: Ours is a culture that treats grief — a process of profound emotional upheaval — with a grotesquely mismatched rational prescription. On the one hand, society seems to operate by a set of unspoken shoulds for how we ought to feel and behave in the face of sorrow; on the other, she observes, “we have so few rituals for observing and externalising loss.” Without a coping strategy, she finds herself shutting down emotionally and going “dead inside” — a feeling psychologists call “numbing out” — and describes the disconnect between her intellectual awareness of sadness and its inaccessible emotional manifestation:

“It was like when you stay in cold water too long. You know something is off but don’t start shivering for ten minutes.”

But at least as harrowing as the aftermath of loss is the anticipatory bereavement in the months and weeks and days leading up to the inevitable — a particularly cruel reality of terminal cancer. O’Rourke writes:

“So much of dealing with a disease is waiting. Waiting for appointments, for tests, for “procedures.” And waiting, more broadly, for it—for the thing itself, for the other shoe to drop.”

The hallmark of this anticipatory loss seems to be a tapestry of inner contradictions. O’Rourke notes with exquisite self-awareness her resentment for the mundanity of it all — there is her mother, sipping soda in front of the TV on one of those final days — coupled with weighty, crushing compassion for the sacred humanity of death:

“Time doesn’t obey our commands. You cannot make it holy just because it is disappearing.”

Then there was the question of the body — the object of so much social and personal anxiety in real life, suddenly stripped of control in the surreal experience of impending death. Reflecting on the initially disorienting experience of helping her mother on and off the toilet and how quickly it became normalised, O’Rourke writes:

“It was what she had done for us, back before we became private and civilised about our bodies. In some ways I liked it. A level of anxiety about the body had been stripped away, and we were left with the simple reality: Here it was.

I heard a lot about the idea of dying “with dignity” while my mother was sick. It was only near her very end that I gave much thought to what this idea meant. I didn’t actually feel it was undignified for my mother’s body to fail — that was the human condition. Having to help my mother on and off the toilet was difficult, but it was natural. The real indignity, it seemed, was dying where no one cared for you the way your family did, dying where it was hard for your whole family to be with you and where excessive measures might be taken to keep you alive past a moment that called for letting go. I didn’t want that for my mother. I wanted her to be able to go home. I didn’t want to pretend she wasn’t going to die.”

Among the most painful realities of witnessing death — one particularly exasperating for type-A personalities — is how swiftly it severs the direct correlation between effort and outcome around which we build our lives. Though the notion might seem rational on the surface — especially in a culture that fetishises work ethic and “grit” as the key to success — an underbelly of magical thinking lurks beneath, which comes to light as we behold the helplessness and injustice of premature death. Noting that “the mourner’s mind is superstitious, looking for signs and wonders,” O’Rourke captures this paradox:

“One of the ideas I’ve clung to most of my life is that if I just try hard enough it will work out. If I work hard, I will be spared, and I will get what I desire, finding the cave opening over and over again, thieving life from the abyss. This sturdy belief system has a sidecar in which superstition rides. Until recently, I half believed that if a certain song came on the radio just as I thought of it, it meant that all would be well. What did I mean? I preferred not to answer that question. To look too closely was to prick the balloon of possibility.”

But our very capacity for the irrational — for the magic of magical thinking — also turns out to be essential for our spiritual survival. Without the capacity to discern from life’s senseless sound a meaningful melody, we would be consumed by the noise. In fact, one of O’Rourke’s most poetic passages recounts her struggle to find a transcendent meaning on an average day, amid the average hospital noises:

“I could hear the coughing man whose family talked about sports and sitcoms every time they visited, sitting politely around his bed as if you couldn’t see the death knobs that were his knees poking through the blanket, but as they left they would hug him and say, We love you, and We’ll be back soon, and in their voices and in mine and in the nurse who was so gentle with my mother, tucking cool white sheets over her with a twist of her wrist, I could hear love, love that sounded like a rope, and I began to see a flickering electric current everywhere I looked as I went up and down the halls, flagging nurses, little flecks of light dotting the air in sinewy lines, and I leaned on these lines like guy ropes when I was so tired I couldn’t walk anymore and a voice in my head said: Do you see this love? And do you still not believe?

I couldn’t deny the voice.

Now I think: That was exhaustion.

But at the time the love, the love, it was like ropes around me, cables that could carry us up into the higher floors away from our predicament and out onto the roof and across the empty spaces above the hospital to the sky where we could gaze down upon all the people driving, eating, having sex, watching TV, angry people, tired people, happy people, all doing, all being—”

In the weeks following her mother’s death, melancholy — “the black sorrow, bilious, angry, a slick in my chest” — comes coupled with another intense emotion, a parallel longing for a different branch of that-which-no-longer-is:

“I experienced an acute nostalgia. This longing for a lost time was so intense I thought it might split me in two, like a tree hit by lightning. I was — as the expression goes — flooded by memories. It was a submersion in the past that threatened to overwhelm any “rational” experience of the present, water coming up around my branches, rising higher. I did not care much about work I had to do. I was consumed by memories of seemingly trivial things.”

But the embodied presence of the loss is far from trivial. O’Rourke, citing a psychiatrist whose words had stayed with her, captures it with harrowing precision:

“The people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created.”

In another breathtaking passage, O’Rourke conveys the largeness of grief as it emanates out of our pores and into the world that surrounds us:

“In February, there was a two-day snowstorm in New York. For hours I lay on my couch, reading, watching the snow drift down through the large elm outside… the sky going gray, then eerie violet, the night breaking around us, snow like flakes of ash. A white mantle covered trees, cars, lintels, and windows. It was like one of grief’s moods: melancholic; estranged from the normal; in touch with the longing that reminds us that we are being-toward-death, as Heidegger puts it. Loss is our atmosphere; we, like the snow, are always falling toward the ground, and most of the time we forget it.”

Because grief seeps into the external world as the inner experience bleeds into the outer, it’s understandable — it’s hopelessly human — that we’d also project the very object of our grief onto the external world. One of the most common experiences, O’Rourke notes, is for the grieving to try to bring back the dead — not literally, but by seeing, seeking, signs of them in the landscape of life, symbolism in the everyday. The mind, after all, is a pattern-recognition machine and when the mind’s eye is as heavily clouded with a particular object as it is when we grieve a loved one, we begin to manufacture patterns. Recounting a day when she found inside a library book handwriting that seemed to be her mother’s, O’Rourke writes:

“The idea that the dead might not be utterly gone has an irresistible magnetism. I’d read something that described what I had been experiencing. Many people go through what psychologists call a period of “animism,” in which you see the dead person in objects and animals around you, and you construct your false reality, the reality where she is just hiding, or absent. This was the mourner’s secret position, it seemed to me: I have to say this person is dead, but I don’t have to believe it.

[…]

Acceptance isn’t necessarily something you can choose off a menu, like eggs instead of French toast. Instead, researchers now think that some people are inherently primed to accept their own death with “integrity” (their word, not mine), while others are primed for “despair.” Most of us, though, are somewhere in the middle, and one question researchers are now focusing on is: How might more of those in the middle learn to accept their deaths? The answer has real consequences for both the dying and the bereaved.”

O’Rourke considers the psychology and physiology of grief:

“When you lose someone you were close to, you have to reassess your picture of the world and your place in it. The more your identity is wrapped up with the deceased, the more difficult the mental work.

The first systematic survey of grief, I read, was conducted by Erich Lindemann. Having studied 101 people, many of them related to the victims of the Cocoanut Grove fire of 1942, he defined grief as “sensations of somatic distress occurring in waves lasting from twenty minutes to an hour at a time, a feeling of tightness in the throat, choking with shortness of breath, need for sighing, and an empty feeling in the abdomen, lack of muscular power, and an intensive subjective distress described as tension or mental pain.”

Tracing the history of studying grief, including Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s famous and often criticised 1969 “stage theory” outlining a simple sequence of Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance, O’Rourke notes that most people experience grief not as sequential stages but as ebbing and flowing states that recur at various points throughout the process. She writes:

“Researchers now believe there are two kinds of grief: “normal grief” and “complicated grief” (also called “prolonged grief”). “Normal grief” is a term for what most bereaved people experience. It peaks within the first six months and then begins to dissipate. “Complicated grief” does not, and often requires medication or therapy. But even “normal grief”… is hardly gentle. Its symptoms include insomnia or other sleep disorders, difficulty breathing, auditory or visual hallucinations, appetite problems, and dryness of mouth.”

One of the most persistent psychiatric ideas about grief, O’Rourke notes, is the notion that one ought to “let go” in order to “move on” — a proposition plentiful even in the casual advice of her friends in the weeks following her mother’s death. And yet it isn’t necessarily the right coping strategy for everyone, let alone the only one, as our culture seems to suggest. Unwilling to “let go,” O’Rourke finds solace in anthropological alternatives:

“Studies have shown that some mourners hold on to a relationship with the deceased with no notable ill effects. In China, for instance, mourners regularly speak to dead ancestors, and one study demonstrated that the bereaved there “recovered more quickly from loss” than bereaved Americans do.

I wasn’t living in China, though, and in those weeks after my mother’s death, I felt that the world expected me to absorb the loss and move forward, like some kind of emotional warrior. One night I heard a character on 24—the president of the United States—announce that grief was a “luxury” she couldn’t “afford right now.” This model represents an old American ethic of muscling through pain by throwing yourself into work; embedded in it is a desire to avoid looking at death. We’ve adopted a sort of “Ask, don’t tell” policy. The question “How are you?” is an expression of concern, but as my dad had said, the mourner quickly figures out that it shouldn’t always be taken for an actual inquiry… A mourner’s experience of time isn’t like everyone else’s. Grief that lasts longer than a few weeks may look like self-indulgence to those around you. But if you’re in mourning, three months seems like nothing — [according to some] research, three months might well find you approaching the height of sorrow.”

Another Western hegemony in the culture of grief, O’Rourke notes, is its privatisation — the unspoken rule that mourning is something we do in the privacy of our inner lives, alone, away from the public eye. Though for centuries private grief was externalised as public mourning, modernity has left us bereft of rituals to help us deal with our grief:

“The disappearance of mourning rituals affects everyone, not just the mourner. One of the reasons many people are unsure about how to act around a loss is that they lack rules or meaningful conventions, and they fear making a mistake. Rituals used to help the community by giving everyone a sense of what to do or say. Now, we’re at sea.

[…]

Such rituals… aren’t just about the individual; they are about the community.”

Craving “a formalisation of grief, one that might externalise it,” O’Rourke plunges into the existing literature:

“The British anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer, the author of Death, Grief, and Mourning, argues that, at least in Britain, the First World War played a huge role in changing the way people mourned. Communities were so overwhelmed by the sheer number of dead that the practice of ritualised mourning for the individual eroded. Other changes were less obvious but no less important. More people, including women, began working outside the home; in the absence of caretakers, death increasingly took place in the quarantining swaddle of the hospital. The rise of psychoanalysis shifted attention from the communal to the individual experience. In 1917, only two years after Émile Durkheim wrote about mourning as an essential social process, Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” defined it as something essentially private and individual, internalising the work of mourning. Within a few generations, I read, the experience of grief had fundamentally changed. Death and mourning had been largely removed from the public realm. By the 1960s, Gorer could write that many people believed that “sensible, rational men and women can keep their mourning under complete control by strength of will and character, so that it need be given no public expression, and indulged, if at all, in private, as furtively as... masturbation.” Today, our only public mourning takes the form of watching the funerals of celebrities and statesmen. It’s common to mock such grief as false or voyeuristic (“crocodile tears,” one commentator called mourners’ distress at Princess Diana’s funeral), and yet it serves an important social function. It’s a more mediated version, Leader suggests, of a practice that goes all the way back to soldiers in The Iliad mourning with Achilles for the fallen Patroclus.

I found myself nodding in recognition at Gorer’s conclusions. “If mourning is denied outlet, the result will be suffering,” Gorer wrote. “At the moment our society is signally failing to give this support and assistance... The cost of this failure in misery, loneliness, despair and maladaptive behaviour is very high.” Maybe it’s not a coincidence that in Western countries with fewer mourning rituals, the bereaved report more physical ailments in the year following a death.”

Finding solace in Marilynne Robinson’s beautiful meditation on our humanity, O’Rourke returns to her own journey:

“The otherworldliness of loss was so intense that at times I had to believe it was a singular passage, a privilege of some kind, even if all it left me with was a clearer grasp of our human predicament. It was why I kept finding myself drawn to the remote desert: I wanted to be reminded of how the numinous impinges on ordinary life.”

Reflecting on her struggle to accept her mother’s loss — her absence, “an absence that becomes a presence” — O’Rourke writes:

“If children learn through exposure to new experiences, mourners unlearn through exposure to absence in new contexts. Grief requires acquainting yourself with the world again and again; each “first” causes a break that must be reset… And so you always feel suspense, a queer dread—you never know what occasion will break the loss freshly open.”

She later adds:

“After a loss, you have to learn to believe the dead one is dead. It doesn’t come naturally.”

Among the most chilling effects of grief is how it reorients us toward ourselves as it surfaces our mortality paradox and the dawning awareness of our own impermanence. O’Rourke’s words ring with the profound discomfort of our shared existential bind:

“The dread of death is so primal, it overtakes me on a molecular level. In the lowest moments, it produces nihilism. If I am going to die, why not get it over with? Why live in this agony of anticipation?

[…]

I was unable to push these questions aside: What are we to do with the knowledge that we die? What bargain do you make in your mind so as not to go crazy with fear of the predicament, a predicament none of us knowingly chose to enter? You can believe in God and heaven, if you have the capacity for faith. Or, if you don’t, you can do what a stoic like Seneca did, and push away the awfulness by noting that if death is indeed extinction, it won’t hurt, for we won’t experience it. “It would be dreadful could it remain with you; but of necessity either it does not arrive or else it departs,” he wrote.

If this logic fails to comfort, you can decide, as Plato and Jonathan Swift did, that since death is natural, and the gods must exist, it cannot be a bad thing. As Swift said, “It is impossible that anything so natural, so necessary, and so universal as death, should ever have been designed by Providence as an evil to mankind.” And Socrates: “I am quite ready to admit… that I ought to be grieved at death, if I were not persuaded in the first place that I am going to other gods who are wise and good.” But this is poor comfort to those of us who have no gods to turn to. If you love this world, how can you look forward to departing it? Rousseau wrote, “He who pretends to look on death without fear lies. All men are afraid of dying, this is the great law of sentient beings, without which the entire human species would soon be destroyed.”

And yet, O’Rourke arrives at the same conclusion that Alan Lightman did in his sublime meditation on our longing for permanence as she writes:

“Without death our lives would lose their shape: “Death is the mother of beauty,” Wallace Stevens wrote. Or as a character in Don DeLillo’s White Noise says, “I think it’s a mistake to lose one’s sense of death, even one’s fear of death. Isn’t death the boundary we need?” It’s not clear that DeLillo means us to agree, but I think I do. I love the world more because it is transient.

[…]

One would think that living so proximately to the provisional would ruin life, and at times it did make it hard. But at other times I experienced the world with less fear and more clarity. It didn’t matter if I was in line for an extra two minutes. I could take in the sensations of colour, sound, life. How strange that we should live on this planet and make cereal boxes, and shopping carts, and gum! That we should renovate stately old banks and replace them with Trader Joe’s! We were ants in a sugar bowl, and one day the bowl would empty.”

This awareness of our transience, our minuteness, and the paradoxical enlargement of our aliveness that it produces seems to be the sole solace from grief’s grip, though we all arrive at it differently. O’Rourke’s father approached it from another angle. Recounting a conversation with him one autumn night — one can’t help but notice the beautiful, if inadvertent, echo of Carl Sagan’s memorable words — O’Rourke writes:

“The Perseid meteor showers are here,” he told me. “And I’ve been eating dinner outside and then lying in the lounge chairs watching the stars like your mother and I used to” — at some point he stopped calling her Mom — “and that helps. It might sound strange, but I was sitting there, looking up at the sky, and I thought, ‘You are but a mote of dust. And your troubles and travails are just a mote of a mote of dust.’ And it helped me. I have allowed myself to think about things I had been scared to think about and feel. And it allowed me to be there — to be present. Whatever my life is, whatever my loss is, it’s small in the face of all that existence… The meteor shower changed something. I was looking the other way through a telescope before: I was just looking at what was not there. Now I look at what is there.”

O’Rourke goes on to reflect on this ground-shifting quality of loss:

“It’s not a question of getting over it or healing. No; it’s a question of learning to live with this transformation. For the loss is transformative, in good ways and bad, a tangle of change that cannot be threaded into the usual narrative spools. It is too central for that. It’s not an emergence from the cocoon, but a tree growing around an obstruction.”

In one of the most beautiful passages in the book, O’Rourke captures the spiritual sensemaking of death in an anecdote that calls to mind Alan Lightman’s account of a “transcendent experience” and Alan Watt’s consolation in the oneness of the universe. She writes:

“Before we scattered the ashes, I had an eerie experience. I went for a short run. I hate running in the cold, but after so much time indoors in the dead of winter I was filled with exuberance. I ran lightly through the stripped, bare woods, past my favourite house, poised on a high hill, and turned back, flying up the road, turning left. In the last stretch I picked up the pace, the air crisp, and I felt myself float up off the ground. The world became greenish. The brightness of the snow and the trees intensified. I was almost giddy. Behind the bright flat horizon of the treescape, I understood, were worlds beyond our everyday perceptions. My mother was out there, inaccessible to me, but indelible. The blood moved along my veins and the snow and trees shimmered in greenish light. Suffused with joy, I stopped stock-still in the road, feeling like a player in a drama I didn’t understand and didn’t need to. Then I sprinted up the driveway and opened the door and as the heat rushed out the clarity dropped away.

I’d had an intuition like this once before, as a child in Vermont. I was walking from the house to open the gate to the driveway. It was fall. As I put my hand on the gate, the world went ablaze, as bright as the autumn leaves, and I lifted out of myself and understood that I was part of a magnificent book. What I knew as “life” was a thin version of something larger, the pages of which had all been written. What I would do, how I would live — it was already known. I stood there with a kind of peace humming in my blood.”

A non-believer who had prayed for the first time in her life when her mother died, O’Rourke quotes Virginia Woolf’s luminous meditation on the spirit and writes:

“This is the closest description I have ever come across to what I feel to be my experience. I suspect a pattern behind the wool, even the wool of grief; the pattern may not lead to heaven or the survival of my consciousness — frankly I don’t think it does — but that it is there somehow in our neurons and synapses is evident to me. We are not transparent to ourselves. Our longings are like thick curtains stirring in the wind. We give them names. What I do not know is this: Does that otherness — that sense of an impossibly real universe larger than our ability to understand it — mean that there is meaning around us?

[…]

I have learned a lot about how humans think about death. But it hasn’t necessarily taught me more about my dead, where she is, what she is. When I held her body in my hands and it was just black ash, I felt no connection to it, but I tell myself perhaps it is enough to still be matter, to go into the ground and be “remixed” into some new part of the living culture, a new organic matter. Perhaps there is some solace in this continued existence.

[…]

I think about my mother every day, but not as concertedly as I used to. She crosses my mind like a spring cardinal that flies past the edge of your eye: startling, luminous, lovely, gone.”

The Long Goodbye is a remarkable read in its entirety — the kind that speaks with gentle crispness to the parts of us we protect most fiercely yet long to awaken most desperately. Complement it with Alan Lightman in finding solace in our impermanence and Tolstoy on finding meaning in a meaningless world.

Source: Maria Popova, brainpickings.org (9th June 2014)

#quote#women writers#love#life#loss#grief#existential musings#all eternal things#love in a time of...#the places you have come to fear the most#the same deep water as you#laid bare#intelligence quotients#depth perception#melancholy skies#this is how it feels#stands on its own#elisa english#elisaenglish

1 note

·

View note

Photo

SOUTH HAVEN’S CELEBRITY OF THE MONTH

OUR FEMALE CELEBRITY OF THE MONTH IS: ZENDAYA COLEMAN! @zendayaxcoleman

For our second Celebrity of The Month! Haveners have chosen Zendaya to be our second female celebrity! We got to hang out with this great gal for a few hours and ask her some cool and juicy questions at A Girl and A Diner, not to mention those damn good milkshakes, but those weren’t the only thing stirring!

Read Zendaya’s Questions Below

So Zendaya let’s get this out of the way before we get into the awesome questions. Hi love, how does it feel to be SHGOSSIP’S very first celebrity of the month?!

Absolutely amazing! I was so nervous about moving here, especially worried about making friends since I’m not always too good at that. But this is such a confidence boost, honestly. I try to put out kindness and hopefully get it back, and I’m glad it isn’t going unnoticed. I’ve gotten to connect and become friends with so many people I never would’ve gotten close to without moving to South Haven, and I’m so happy that people think of me when they think of South Haven!

Alright now for some juicy stuff. We know there are many gorgeous celebrities around South Haven, can you name someone you might have your eye on?

You’ve got that right! Everyone around here is gorgeous, I don’t even know how it’s possible for one town to be so good looking. One thing I didn’t anticipate when moving to South Haven was reconnecting with old friends, but I can’t say I’m upset about it. I guess I kind of have my eye on Zac, but I think we’re just taking things kind of slow right now.

You’ve been in SH for quite a while right? How has it been for you? And why did you come here?

It’s been wonderful so far, it’s only been a few months I think, I honestly don’t know because it feels like I’ve been here forever! I have always been such an introvert and whenever I wasn’t working when I was living in LA, I would just stay home. But South Haven and the people here have really pulled me out of my shell and I find myself going out and exploring all the time. I came here to get away from the toxic environment of Los Angeles, honestly. The rumors about Tom Holland and I were getting so crazy and there were paparazzi all the time, I’m glad I came somewhere where other people can relate and understand what I’m going through. Plus I used this move as a way to open up a new chapter of my life. I’m working less, my mental health is getting better, and hopefully, I can stay here and live a semi-normal life for many years to come.

Now some cool and fun questions. Do you think you could settle down in SH? Maybe have a couple of kids, get married, blah blah blah?

That’s honestly a big reason why I came here. When I do have kids someday, I want them to at least try to have a normal life and South Haven seems like the perfect place for them to do it. I guess I should worry about marriage first, but I’m sure that’s still pretty far down the road. Especially after seeing some wonderful couples get engages and eventually married here, it’s giving me wedding fever and I can’t wait until I have one myself someday.

And lastly, let’s get a little personal. On our very own SH Daily you were mentioned to have been getting very close with one blue eyed beauty Zac Efron, care to give us a little more insight on that?

Zac and I were really close when we worked together for The Greatest Showman, both literally and figuratively. It was actually one of the best ice breakers ever to be attached to each other in mid-air, but we bonded really well during that, constantly checking in on each other after a take to make sure we were both alright. I guess that was kind of the start of something a little more than a friendship. But we were both so busy after that we kind of lost touch, and now that we both live in South Haven we’ve reconnected which has been nice. We’ve hung out a few times, maybe shared a blanket at movie night, and we’re rooming together on the cruise. There’s definitely been some flirting and I think we’re on the way to something more serious but right now we’re just kind of enjoying each other’s company.

QUICK FACTS & FAVORITES

FAMILY: I have a really big family, my parents visit all the time. My siblings are my best friends, and my little nieces and nephews are basically my kids too at this point because I force them to hang out with me.

PETS (if not do you want some?): I have a miniature schnauzer named Noon and I hope to get a few more!

FAVORITE SPOT IN TOWN: How could I ever pick? I guess I’ll say Central Park, but there’s really not a bad spot in town!

BEST FRIEND IN SH: Either Tessa or Camila, I could never pick!

BEST FOOD PLACE: This is such a hard choice but I guess I’m going to have to say Italia’s, I’m definitely a pasta girl.

CELEB’S LIFE YOU WANT: Either Beyonce or Rihanna

BEST DATE PLACE: Definitely watching the sunset from the Pier with some takeout!

TO US

Recommended Song: “Hold Up” Beyonce

Quote To Live By: “Dreams come true; without that possibility, nature would not incite us to have them.” John Updike

Recommended Movie: All of the Harry Potter movies!

Thank you so much Zendaya for settling down with us into some juicy questions! You will great bragging rights for a month on being the best celebrity of the month! Now I am going to head to the Pier, for a date that I don’t have, get takeout and binge watch all the Harry Potter movies! Until next time, stay juicy!

Xoxo South Haven Daily.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dos and Don’ts of Beginning a Novel: An Illustrated Guide

I’ve had a lot of asks lately for how to begin a book (or how not to), so here’s a post on my general rules of thumb for story openers and first chapters!

Please note, these are incredibly broad generalizations; if you think an opener is right for you, and your beta readers like it, there’s a good chance it’s A-OK. When it comes to writing, one size does not fit all. (Also note that this is for serious writers who are interested in improving their craft and/or professional publication, so kindly refrain from the obligatory handful of comments saying “umm, screw this, write however you want!!”)

So without further ado, let’s jump into it!

Don’t:

1. Open with a dream.

“Just when Mary Sue was sure she’d disappear down the gullet of the monstrous, winged pig, she woke up bathed in sweat in her own bedroom.”

What? So that entire winged pig confrontation took place in a dream and amounts to nothing? I feel so cheated!