#de vulgari eloquentia

Text

Don’t worry, he realized the mistake after writing 3 books

#I am the same type of delulu#just on other things#3 books out of the 4 he planned on writing#De vulgari eloquentia#dante#dante alighieri#italian literature#letteratura italiana#Italian tag

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

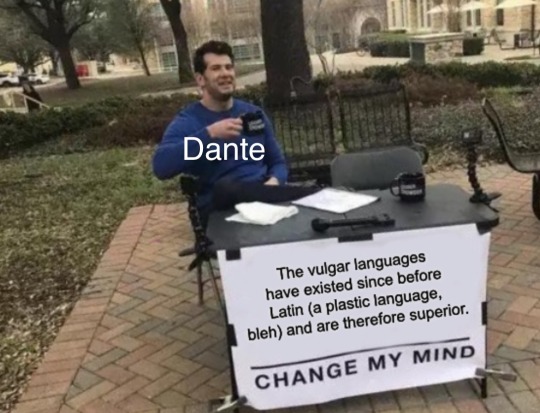

Anteayer he recibido esto. Volumen 4 de Neon Genesis Evangelion, de Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, y Monarchia, Convivio y De Vulgari Eloquentia, de Dante.

El volumen 3 de Evangelion venía con un pegamento diferente a los volúmenes 1 y 2, y se sentía demasiado rígido al abrirlo. Este volumen 4 trae el mismo pegamento que los volúmenes 1 y 2 y se siente bien. Sólo incluye 3 ilustraciones a color, una a doble página. Por lo demás, excelente calidad de impresión y del papel.

A lo largo de los años, he leído un montón de veces la Divina Comedia (la traducción de D. Manuel Aranda y San Juan, con las notas de Paolo Costa y los grabados de G. Doré, reedición de la de 1921), pero no había leído nada más de Dante. Tal vez temía decepcionarme: la Divina Comedia es la última obra de Dante (a su muerte, incluso se temía que no estuviera terminada, porque no encontraban los cantos finales), así que pensaba que tal vez sus obras previas no fueran tan buenas como la Divina Comedia, que, después de todo, es la obra poética más grande de toda la Edad Media.

Pero este año leí la Vita Nuova, y me ha gustado mucho. La leí en una edición de Cátedra, de la colección Letras Universales. Son libros pequeños, pero el papel es bueno, la impresión es clara y la fuente no es excesivamente pequeña. Parecen ediciones muy cuidadas, con introducciones y notas muy trabajadas. El único “pero” es que en México son difíciles de encontrar. Así que, aprovechando que compraba el volumen 4 de Evangelion de Agapea (Málaga, España), he comprado éstos también. (El envío urgente [DHL] es muy rápido).

- - -

La sonrisa en forma de ω

#libros#evangelion#neon genesis evangelion#manga#Yoshiyuki Sadamoto#asuka#shinji#rei#misato#kaji#dante#dante alighieri#convivio#monarchia#de vulgari eloquentia#agapea#cátedra#norma editorial#ω#personal

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

For all that has been written about the author of the Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) remains the best guide to his own life and work. Dante’s writings are therefore never far away in this authoritative and comprehensive intellectual biography, which offers a fresh account of the medieval Florentine poet’s life and thought before and after his exile in 1302.

Beginning with the often violent circumstances of Dante’s life, the book examines his successive works as testimony to the course of his passionate humanity: his lyric poetry through to the Vita nova as the great work of his first period; the Convivio, De vulgari eloquentia and the poems of his early years in exile; and the Monarchia and the Commedia as the product of his maturity. Describing as it does a journey of the mind, the book confirms the nature of Dante’s undertaking as an exploration of what he himself speaks of as “maturity in the flame of love.”

The result is an original synthesis of Dante’s life and work.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

one thing I'd add is that the regularity of sound change is (at least to me) entirely non-obvious. it's an empirical fact, and without investigation the rare exceptions are more likely to be noticed by their blatantness and common use.

you might also want to have a look at Dante's thoughts on linguistics, in the early chapters of the De Vulgari Eloquentia.

he recognizes the Romance family and its subdivisions (and (an overextended) Germanic and Greek as separate families), and that languages change over time and divide over the mgirations of peoples, but doesn't realize that they're descended from Latin, since he thinks of Latin and other standardized languages as artificial creations.

[re] I had no idea Dante wrote on the subject! That's really interesting, too. The Romance languages seem like a smoking gun for language descent/differentiation, if not for regular sound laws, being well-documented and having spread out within historical memory, and I suppose that wasn't lost on people, even in the 13th–14th centuries. "Artificial Latin" is an interesting belief, too—I wonder if that played a role in his decision to write in the vernacular.

Regarding sound laws, I think the primary thing that makes them non-obvious is probably conditioning, including the need for robust concepts of phonetic features/series, syllable and stress structures, and so on in order to even conceive of many sound changes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello philologists and historians, my lovely sister is looking for primary sources about how people in the Renaissance viewed (the theory of) translation - does anything jump to mind?

All I can think of is (maybe?) Dante's De Vulgari Eloquentia but I feel like some must have considered why they would/should (not) translate things from Latin and Greek??

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

de vulgari eloquentia, liber primus, XI

dante alighieri

ma hanno anche dei difetti!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love dante but reading de vulgari eloquentia is just continuously repeating oh baby you are so stupid you are such an idiot please stop talking now.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from Gravelle's "The Latin-Vernacular Question and Humanist Theory of Language and Culture"

"Most fifteenth-century humanists chose to write in Latin because of their conviction of its superiority to the vernacular for prose composition. This conviction was based on their misgivings about certain features of the vernacular admitted even by its advocates. Leon Battista Alberti, Cristoforo Landino, and Lorenzo de' Medici acknowledged flaws in the vernacular but believed these flaws came not from inherent inferiority but from historical neglect. Their opinion derived from the humanist study of the historical nature of language, not from the opposition of the partisans of the Volgare [vulgar-vernacular] to the classicism of humanism."

"The Volgare was judged inferior to Latin on two counts: vocabulary and grammar. First, its vocabulary was thought to be meager compared to the copia of Latin. The defense of the vernacular had to reckon with the charge that it could only express thought in a crude and clumsy way. These discussions of vocabulary contributed to a theory that linked the growth of language and intellectual capacities. The second count against the vernacular was that it was ungrammatical, an idea inherited from earlier philology and shared by at least one humanist. According to this idea, the modern languages were disordered and ungrammatical; the ancient, regular and grammatical. Before the Volgare could be treated on an equal footing with Latin, the humanists had to come to a better understanding of grammar. And pursuing this inquiry into the nature of grammar, some humanists would link grammar and the structure of thought."

"Although there are a few similarities, fifteenth-century comparisons are different from earlier ones, as Dante's and Boccaccio's ideas about the relative merits of the two languages show. Both see the greater use and currency of the vernacular as an asset, as do later humanists. Indeed, for Dante the vernacular is more noble than Latin because of its greater use. Both Dante and Boccaccio believe its defect to be want of grammar, art, and regularity. Dante justifies his use of the vernacular in the Convivio by saying that the work in Latin would be as useless as gold and pearls buried in the ground. In his Life of Dante Boccaccio praises Dante's decision to write the Divine Comedy in the Volgare for the benefit of his fellow citizens, who had been abandoned by the learned. To write for them in Latin would be like giving a newborn a crust of bread to swallow. Boccaccio says that Dante considered but rejected a Latin version, of which three lines are cited. Still, Dante's choice of the vernacular is not altogether praiseworthy to Boccaccio. The Comedy is likened to a peacock. The peacock's distinctive features are flesh that will not rot, gorgeous form and 'foul feet and noiseless tread.' Where one expects Boccaccio to liken the content of the Comedy to the flesh and its form to the feathers, one is surprised to find the vernacular form compared to the 'foul feet and noiseless tread!'. Moreover, Boccaccio says in his Commentary on Dante that the Comedy would have been 'much more full of art and more sublime in Latin because Latin speech has much more of art and dignity than the maternal speech.'"

"Dante and Boccaccio are both sure that Latin is richer than the

Volgare, and therefore many more things can be conceived in Latin."

"The humanist debates about grammar are the foundations of a new theory of language and culture. This is perhaps most clearly understood by contrast with some prehumanist ideas of grammar and language. The question of grammatical inferiority is different from the question concerning copia. The first considers vocabulary, the second the structure of language. Again it is instructive to compare humanist and prehumanist ideas, as before in the question of copia. In Dante's words, Latin is "perpetual and incorruptible" because grammatical. Grammar is an art that was devised to arrest change and variety. In De Vulgari Eloquentia he says that change motivated 'the inventors of the art of grammar, which is nothing else but a kind of unchangeable identity of speech in different times and places.'"

"Dante believes the vulgar tongue to be governed by mutable usage, to which Latin is impervious because established by art and grammar. Art and grammar give it regularity, and this regularity makes it more beautiful than the vernacular: 'Therefore that language is the most beautiful in which the parts correspond most perfectly as they should, and they do so in Latin more than in the vulgar tongue, because custom regulates the latter, art the former; wherefore it is granted that Latin is the more beautiful, the more excellent, and the more noble.'"

"Poverty of language is a flaw also frequently imputed to the vernacular in the fifteenth century. However, because of a better understanding of the historical nature of language, the humanists began to argue that the Volgare could become sufficiently copious. Moreover, from the discussions of copia comes a theory of culture: as language grows through certain stages, so do the intellectual powers of a civilization. Valla calls copia "a faculty and a power."" Copia is an important idea in humanist philosophy of language, a concept used to demonstrate the nexus of language and thought. Besides this epistemological motive, copia is used in [theories] of culture."

"Dante's idea is relevant here for two reasons. The first pertains to the question of the two languages, the second to a wider issue of language and reality. The immutability of ancient languages, an ahistorical idea, is described in the first pages of De Vulgari Eloquentia. There he discusses the origin of speech in Eden. He says that language is only necessary to man; neither God nor the angels have need of it. They communicate their ineffable meanings without the clumsiness of speech. Their glorious thoughts are exchanged silently, mind to mind. Only man has need of words: 'Nor does it happen that one man can enter into the mind of another by spiritual insight, like an angel, because the human spirit is hindered by the grossness and opacity of its mortal body.'"

"Dante then conjectures about who spoke the first word and in what speech. He says that the biblical story says Eve spoke the first word but then dismisses the idea that the first recorded speech was made by a woman as contrary to common sense and reason. Adam spoke first; he was moved to utter certain words rendered distinct by Him who has distinguished greater things. Dante says that the first language was Hebrew. Divinely instituted, the connection of word and thing was not arbitrary but established by God, as was the grammar: 'We assert that a certain form of speech was created by God together with the first soul. And I say, 'a form,' both in respect of the names of things and of the grammatical construction of these names, and of the utterance of this grammatical construction.'"

"The unity of language and reality was destroyed at Babel, although Hebrew survived so that Christ 'might use not the language of confusion but of grace.' To measure the originality of humanist philosophy of language, Valla's comments about language, Adam, and Babel should be compared with the passage from De Vulgari Eloquentia. To Valla all meaning is created by man and history, not God and nature: 'Indeed, even if utterances are produced naturally, their meanings come from the institutions of men. Still, even these utterances men contrive by will as they impose names on perceived things … Unless perhaps we prefer to give credit for this to God who divided the languages of men at the Tower of Babel. However, Adam too adapted words to things, and afterwards everywhere men devised other words. Wherefore noun, verb, and the other parts of speech per se are so many sounds but have multiple meanings through the institutions of men.'"

"An idea akin to Dante's of the identity of grammar and Latin persisted in the Quattrocento, when it was rejected by most humanists. In the famous debate about the vernacular in ancient Rome, Bruni takes a position reminiscent of Dante's. This debate took place in 1435 in the antechamber of Eugenius IV among Bruni, Antonio Loschi, Flavio Biondo, Cencio dei Rustici, Andrea Fiocco, and Poggio. The issue was whether there was a vernacular in ancient Rome. Bruni maintained that bakers and gladiators could not have mastered grammar and Latin. Loschi agreed; the others did not. Later other humanists, Guarino, Valla, and Filelfo, heard of the debate and wrote against Bruni. Salvatore Camporeale, among others, has discussed this debate, which is important in the story of humanist thought about grammar and the rival claims of authority and common usage as determinants of language. The debate is one instance of the confrontation of two different concepts of rhetoric. The first concept is that of Antonio Loschi: rhetoric is a formal art, higher than ordinary discourse. He says: 'Eloquence is a higher thing [than the conventions of daily speech] and more removed from vulgar speech and, even if it often concerns uncertainties and common things, still it is contained in its own peculiar and certain principles.' The second concept of rhetoric emphasizes the semantic and linguistic science of speech. The opponents of Loschi and Bruni argue that meaning arises from the historical and mutable conventions of ordinary usage, although they all admit the importance of literate authority in establishing usage. Thus the creative force in language is general cultural conventions."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Main masterlist🕊️

Generale🖋️

Gaspara Stampa not beating the Protestant allegations

Unhinged De Vulgari Eloquentia summary

Foscolo is just delulu

Genshin impact danteification @moonschocolate

Cose più serie 🖋️

Dante and Virgilio in the Camposanto affresco

Dante e Beatrice - Michael Parkes 1993

Dante in Exile - Micheal Parkes 1998

Beatrice Alone - Micheal Parkes 1998

#masterlist#italian literature#Italian tag#roba italiana#italians on tumblr#italian stuff#italian tumblr#letteratura italiana#letteratura#poesia#meme#funny joke#poeti#poetry#poets#dante alighieri#Niccolò Machiavelli#francesco petrarca#torquato tasso#Gaspara stampa#giovanni boccaccio#giacomo leopardi#italian poetry#alessandro manzoni#ludovico ariosto#divina commedia#divine comedy#petrarch#dante

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Este post ha estado en borradores desde Noviembre del año pasado. (Y los libros siguen en lista de espera de ser leídos).

---

Me he encontrado un lugar donde aún tenían cosas de la Editorial Akal. Desde hace algún tiempo libros de esta editorial han escaseado en México, al menos en la colección Clásica y la Universitaria, que son las que me interesan. Creo que la colección Clásica de Akal está a la altura de los Gredos, descontando que la de Akal es formato de bolsillo y tapa blanda.

Himnos y Epigramas, de Calímaco. Epinicios, de Píndaro. Fábulas y Astronomía, de Higino. Saturnales, de Macrobio. Y La estructura moral del Infierno de Dante. Ésta última es obra póstuma de C. López Cortezo.

---

En particular, tengo muchas ganas de leer el volumen de Higino, y el de C. López, aún más. El año pasado he leído, por primera vez, algo de Dante que no era la Divina Comedia (Vita Nuova). Recién he terminado de leer el Convivio y comienzo con De Vulgari Eloquentia. No sabría si recomendar el Convivio.

Contiene ideas interesantes. Sin embargo, depende mucho de un trasfondo filosófico (Boecio, neoplatonismo mediatizado [Liber de Causis], aristótelismo, y escolástica [Alberto Magno, Tomás de Aquino]) y puede resultar cansino para quien no esté familiarizado con los conceptos, principios y métodos de la filosofía antigua y medieval, o para aquellos que, conociendo, no le tienen estima alguna a Aristóteles y los filósofos de la Edad Media.

1 note

·

View note

Note

13, 16, 17, and 27 for the historical asks ❤️

Oh my gosh! So many questions! :D Thank you for the ask, my lovely!

13) Something random about some random historical person in a random era.

Here is an interesting fact about Dante Alighieri, one of my favourite writers/poets.

Dante was the first writer who used a different language other than the commonly used Latin. Instead, he promoted the use of a more easily accessible vernacular language, based on the dialect of his beloved Florence. His treatise De vulgari eloquentia (On the Eloquence of the Vernacular), outlines the ways in which promoting the vernacular language is better for unification of the people. He was essentially a pioneer in this, and his views on language will be instrumental several centuries later, when Italy finally unifies.

Another fun fact, the "Italian" that is typically taught in schools and which is heard on the news is based on Dante's early Florentine vernacular.

16) Do you own some historical item? (coin, clothing, weapons, books, etc) If yes which one is your favourite?

Sadly, I do not. My husband has some fancy printings of famous books, but they're just a fancy version of them. I wish I did, though.

17) What historical item would you like to own?

I answered this question in another ask, but I can try to think of another answer. I really love period clothing. I've been wanting to try and find retro-style clothing for myself because they're just really gorgeous. I really like clothing from the 40s and 50s in particular. So, if I could get like a wardrobe of various period clothing and learn how to wear them, I'd be very very happy. :)

27) Favourite historical “ What if… ” ?

Oh man, this is GOOD one. Ok so I LOVE finding videos on YouTube that dive into these What If... scenarios. It's always fun to look at massive historical events, and see how the patterns of history would have changed had something not happened the way that it did.

One of my favourite What Ifs to follow is about The Black Death and what would have happened if it just never had the massive impact it did, or if it just never occurred.

Now The Black Death (the medieval one) had a DEVASTATING toll on the world. In Europe, it wiped out nearly a third of its entire population. This had an effect on the economy, as now workers were able to demand better wages and respect from their Lords, or simply move out of the farms and into the cities.

During the Black Death, a LOT of people lost faith in the Catholic Church, leading to an era where philosophy flourished, as well as hedonism and an appreciation for beauty. I think you know where I'm going with this... The Renaissance.

But, what if it didn't happen? What would change? The YouTube channel AlternateHistoryHub does a pretty decent dive into the What If scenario here, so I encourage a watch if you're interested. Take care though, he goes in depth about the Plague and its effects, and talks about the rampant anti-sematism that occurred during this time.

youtube

He presents a very bleak alternate history, talking about overpopulation and a severe shortage of food and resources. Feudalism stays in tact, no peasant revolts, no shift in culture. He does makes it clear that it wouldn't mean we'd all be serfs to this day, but that certain shifts would have taken a lot longer to occur.

Really fascinating stuff.

ASK ME THE HISTORY QUESTIONS PLEASE!

#belle babbles#history asks#this is my jam you guys#I have been loving answering all these history questions#ask me the things#ask game

1 note

·

View note

Text

Italian influence on English

Italian influence on English

Italian influence on English, an article that explains the influence of the Italian language, culture and authors on the English language through the centuries.

The Italian language is a Romance language spoken by some 66,000,000 persons, the vast majority of whom live in Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia). It is the official language of Italy, San Marino, and (together with Latin) Vatican City. Italian is also (with German, French, and Romansh) an official language of Switzerland, where it is spoken in Ticino and Graubünden (Grisons) cantons by some 666,000 individuals.

Italian is also used as a common language in France (the Alps and Côte d’Azur) and in small communities in Croatia and Slovenia. On the island of Corsica a Tuscan variety of Italian is spoken, though Italian is not the language of culture. Overseas (e.g., in the United States, Brazil, and Argentina) speakers sometimes do not know the standard language and use only dialect forms. Increasingly, they only rarely know the language of their parents or grandparents. Standard Italian was once widely used in Somalia and Malta, but no longer. In Libya too its use has died out.

Dante, the main Italian poet, in exile about 1300, began a book meant to guide the development of Italian poetics. He dropped it after a few chapters, but what he finished of "De vulgari eloquentia" contains an explanation in medieval terms of the linguistic map of Europe.

In the introduction he begins by stating something obvious to him, and no doubt to his peers, but that might seem strange to us. In most of the world around him, he says, there are two languages in the same place. Call them "low" and "high," or "vulgar" and "classical," or "common" and "learned." Dante calls the first "vulgar" or "vernacular."

We moderns can miss something obvious to Dante: we study the language of Cicero and Caesar, and then assume French, Italian, and Spanish descended from that. They didn't. They descend from the common speech of the people going about their lives in the Empire, the "Vulgar Latin," which always was a separate thing from the artificial literary Latin.

Dante goes on to make a radical, revolutionary statement, by the way, but a necessary one for his purpose: he identifies the common speech as the more valuable, because the more human. Of these two kinds of language, the more noble is the vernacular: first, because it was the language originally used by the human race; second, because the whole world employs it, though with different pronunciations and using different words; and third because it is natural to us, while the other is, in contrast, artificial.

Dante Alighieri

Geoffrey Chaucer, the renowned English poet of the Middle Ages, lived from approximately 1343 to 1400. While there is no direct evidence that Chaucer had personal knowledge of the main literary Italian authors of his time, he was certainly aware of Italian literature and its influence.

Chaucer's most famous work, "The Canterbury Tales," includes several stories and characters that are influenced by Italian literature. For example, his story "The Knight's Tale" is based on the work of the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically his work "Teseida," which tells a similar story of love and chivalry. Chaucer also drew inspiration from Boccaccio's "Decameron" for some of his other tales.

Additionally, Chaucer was familiar with the works of Dante Alighieri, particularly Dante's "Divine Comedy." Chaucer's "The House of Fame" and "The Parliament of Fowls" show signs of Dantean influence.

So, while Chaucer may not have personally known these Italian authors, he was certainly aware of their works and drew inspiration from them, incorporating elements of Italian literature into his own writing. This reflects the broader trend of the influence of Italian literature on English literature during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The Italian Renaissance had a significant influence on English language and culture during the 15th and 16th centuries. This period of intellectual and artistic revival in Italy had several notable impacts. Italian literature in particulary with works by authors like Petrarch and Dante, was translated into English and inspired English writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer. Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales" was influenced by Italian storytelling techniques.

Italian humanistic ideas emphasizing the value of individualism, human potential, and classical learning influenced English scholars and thinkers. This led to a renewed interest in classical Greek and Roman texts, which shaped English intellectual discourse. Then Italian Renaissance art, characterized by realism and perspective, influenced English artists and architects. Renaissance ideas can be seen in English cathedrals, palaces, and paintings of the period.

In this period the English language absorbed many Italian words, especially related to art, music, and cuisine. Words like "piano," "opera," and "spaghetti" entered the English lexicon during this time. What's more Italian Renaissance advances in science and exploration, such as developments in navigation and cartography, indirectly contributed to the growth of English exploration and the expansion of the English language.

Last but not least the Italian Renaissance's political ideas, including the concept of the "Renaissance prince" as described by Machiavelli, influenced English political thought, contributing to discussions on monarchy and governance. In summary, the Italian Renaissance had a multifaceted impact on English language and culture, leaving a lasting imprint on literature, art, language, philosophy, and politics during this transformative period in history.

Italian language and English

John Mullan explores how Italian geography, literature, culture and politics influenced the plots and atmosphere of many of Shakespeare’s plays. John Mullan is Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature at University College London. John is a specialist in 18th-century literature and is at present writing the volume of the Oxford English Literary History that will cover the period from 1709 to 1784. He also has research interests in the 19th century, and in 2012 published his book What Matters in Jane Austen?

So frequent and thorough is Shakespeare’s engagement with Italy in his plays that it has been suggested that he travelled to Italy some time between the mid-1580s and the early 1590s – the so-called ‘lost years’ when we have no reliable information about his whereabouts. There is no evidence to support this claim, but it is clear that Italy was his primary land of the imagination. Unlike other countries – such as France, Austria or Denmark – in which he set particular plays, his representations of Italy are diverse and usually precise. Different cities in Italy are chosen for different plays and given distinct qualities and associations.

When he so often chose Italian settings for his plays, Shakespeare was exploiting his contemporaries’ lively interest in the country. It was the destination of many Elizabethan travellers and the subject of many travel writings. (In As You Like It, when Jaques tells Rosalind that he has the ‘humorous sadness’ of a ‘traveller’, she naturally assumes ‘you have swam in a gundello ’ (4.1.19–21). Any serious traveller would have been to Venice.) If Shakespeare did not know Italian, many of his educated contemporaries did. It is likely that he encountered educated Italians in London – he might well have known leading humanist scholar John Florio, an Italian who was tutor to his patron, the Earl of Southampton.

Italy had a special hold on poets. The very forms of Elizabethan verse and the terminology of its patterns (stanza, sestina) often came from Italy. The sonnet (from the Italian sonetto) was introduced to English in the 1550s in explicit imitation of Italian models, and especially of the Italian poet Petrarch. In Romeo and Juliet, a play whose very prologue is a sonnet, Mercutio, mocking Romeo for his lovelorn posturing, tells Benvolio to expect from him the poetry of unrequited passion: ‘Now is he for the numbers that Petrarch flow’d in’ (2.4.38–39). The 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca (known as ‘Petrarch’ in English) was greatly admired in England, especially for his sonnets, which elaborately expressed his hopeless love for the nearly divine ‘Laura’.

John Florio was an Italian-born linguist and scholar who played a significant role in influencing the English language through his works. His influence primarily stems from his contributions to English lexicography and his translations of Italian literature. In 1598 and in 1611 he published the first two Italian-English dictionaries: A World of Words, and Queen Anna's New World of Words.

Unlike the lexicographers that preceded him, he didn't use just Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch, but as a wide a variety of works as possible. This dictionary was a valuable resource for English speakers seeking to learn Italian and helped introduce numerous Italian words and phrases into the English language. It facilitated cross-cultural communication and enriched English vocabulary with terms related to art, music, literature, cuisine, and daily life.

This scholar also translated several Italian literary works into English, most notably the essays of Michel de Montaigne. His translation of Montaigne's essays introduced English readers to Montaigne's humanist philosophy and literary style, influencing English prose writing in the process. He is recognised as the most important humanist in Renaissance England.

John Florio contributed to the English language with 1,149 words, placing third after Chaucer (with 2,012 words) and Shakespeare (with 1,969 words), in the linguistic analysis conducted by Stanford professor John Willinsky. He was also the first translator of Montaigne into English, the first translator of Boccaccio into English and he wrote the first comprehensive Dictionary in English and Italian (surpassing the only previous modest Italian–English dictionary by William Thomas published in 1550).

Firenze Tuscany Italy

Florio was also known for his playful and inventive use of language. He often incorporated puns, wordplay, and creative expressions into his writing. His linguistic experimentation contributed to the development of a more flexible and expressive English language.

Some scholars suggest that Florio's translations and linguistic style may have inspired aspects of Shakespeare's works, including the use of Italian words and phrases in Shakespearean plays like "Romeo and Juliet" and "Othello."

On December 2020, Bbc aired a documentary titled "Scuffles, Swagger & Shakespeare: The Hidden story of English", in which Dr John Gallagher uncovered the real, complex story of how English conquered the world. John Florio was there too, described as a man who wanted to bring European culture and literature to the English masses.

Gallagher reminded the audience that while in Italy and France a renaissance had been transforming art and literature, in England it had struggled to put down roots, and some thinkers were worried that the country was falling behind. But John Florio was determined to change that. He made his mission to bring continental ideas in England. Gallagher showed the difficulties that immigrants faced in Elizabethan England, by reading the words John Florio wrote in 1591: "I know they have a knife at command to cut my throat. An Englishman in Italian is a devil incarnate."

Italian literature, and indeed standard Italian, have their origins in the 14th-century Tuscan dialect - the language of its three founding fathers, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. The thread of literature bound these pioneers together with later practitioners, such as the scientist and philosopher Galileo, dramatist Carlo Goldoni, lyric poet Giacomo Leopardi, Romantic novelist Alessandro Manzoni, and poet Giosuè Carducci.

Women writers of the Renaissance such as Veronica Gàmbara, Vittoria Colonna, and Gaspara Stampa were also influential in their time. Rediscovered and reissued in critical editions in the 1990s, their work prompted an interest in women writers of all eras within Italy.

Italian music has been one of the supreme expressions of that art in Europe: the Gregorian chant, the innovation of modern musical notation in the 11th century, the troubadour song, the madrigal, and the work of Palestrina and Monteverdi all form part of Italy’s proud musical heritage, as do such composers as Vivaldi, Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini, and Bellini.

Music in contemporary Italy, though less illustrious than in the past, continues to be important. Italy hosts many music festivals of all types - classical, jazz, and pop - throughout the year. In particular, Italian pop music is represented annually at the Festival of San Remo. The annual Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto has achieved world fame. The state broadcasting company, Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI), has four orchestras, and others are attached to opera houses; one of the best is at La Scala in Milan. The violinists Uto Ughi and Salvatore Accardo and the pianist Maurizio Pollini have gained international acclaim, as have the composers Luciano Berio, Luigi Dallapiccola, and Luigi Nono.

Contemporary productions maintain Italy’s eminence in opera, notably at La Scala in Milan, as well as at other opera houses such as the San Carlo in Naples and La Fenice Theatre in Venice, and the annual summer opera productions in the Roman arena in Verona. Tenors Luciano Pavarotti and Andrea Bocelli were among Italy’s most acclaimed performers at the turn of the 21st century.

As Michael Ricci explains in an article, Italian-American citizens have influenced both our language and our society. With the immigration of many Italians to our country, they not only have contributed to our language, but also to our culture. Words used in English that are borrowed from the Italian language are commonly known as loan words.

Venice in Italy

Our language contains many Italian loans words. These words encompass many areas of our society like food, music, architecture, literature and art, the military, commerce and banking. The Italian loan words are the most dominantly descriptive in the subject area of our foods. We are all familiar with pizza, ravioli, pasta, bologna (baloney), coffee, pepperoni, salami, soda, artichoke and broccoli, but the more discriminate gourmets might find many other foods and drinks found here to excite their palates.

Other delicious offerings are available at many choice Italian restaurants like panini, an Italian sandwich made usually with vegetables, cheese, and grilled or cooked meat. Ciabatta an open textured bread made with olive oil. Foccacia is a flat Italian bread traditionally flavored with olive oil and salt, and often topped with herbs and onions. Fish items are available like calamari, a squid prepared as food; or scampi, which are large shrimp boiled or sautéed and served in garlic and butter sauce.

Most people in our society who are not Italian-Americans refer to all kinds of macaroni as pasta; we Italian-Americans like to call them macaroni. Some macaronis are used with soup and are often given to infants because of their small size, like acite de pepe and pastina. Besides servings being given to babies, these are also used in soup. These small macaronis are sometimes used as toppings on salads. Other macaronis like spaghetti, linguini and ziti are cooked in seasoned tomato sauce. Manicotti is stuffed with ricotta or other soft cheeses. Lasagna is a favorite as a baked macaroni, which is layered with cheese, and ground beef baked between the sheets of precooked lasagna. Tortellini is a specialty pasta in small rings, stuffed usually with meat or cheese, and served in soup or with a sauce. Pesto is a tomato sauce consisting of, usually, fresh basil, garlic, pine nuts, olive oil and grated cheese.

Many of these meals are topped off with many delicate sweet foods like biscotti, crisp Italian cookies flavored with anise, and often containing almonds and filberts. Tiramisu is a dessert of cake infused with a liquid, such as coffee or rum. Tortoni is a rich ice cream often flavored with sherry. Amaretto is a sweet, almond-flavored liqueur. Maraschino is a bittersweet clear liqueur with marasca cherries.

Food words are only the tip of the Italian-American iceberg. Other Italian loan words can be found in music. By far, music seems a topic dominated by Italian loan words. The more familiar musical ones are alto, soprano, basso (voice ranges); cello, piano, cello, piccolo, viola, oboe, violin and harmonica (musical instruments); largo, andagiettio and fermata (musical tempos); crescendo, forte and sforzando (volume); agitato, bruscamente and affettuoso (mood); molto, poco and meno (musical expressions); and altissimo, acciaccatura and pizzicato (musical techniques).

Examples in the literature category are novel and scenario; in art, fresca (fresh painting) and dilettante (amateur); in architecture, balcony and studio; in banking, bank and bankrupt; military: alarm, colonel and sentinel; politics: ballot, ghetto and bandit. Italians formerly used balls in their voting, and the word “ball” eventually became “ballot.”

Read the full article

#Boccaccio#Bocelli#canzone#Chaucer#cinema#commedia#Dante#Decameron#divina#English#Europe#festival#Florio#food#influence#Italian#Italy#language#latin#literature#music#opera#pasta#Pavarotti#Petrarca#Pizza#poet#Poetry#Renaissance#SanRemo

1 note

·

View note

Text

For all that has been written about the author of the Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) remains the best guide to his own life and work. Dante’s writings are therefore never far away in this authoritative and comprehensive intellectual biography, which offers a fresh account of the medieval Florentine poet’s life and thought before and after his exile in 1302.

Beginning with the often violent circumstances of Dante’s life, the book examines his successive works as testimony to the course of his passionate humanity: his lyric poetry through to the Vita nova as the great work of his first period; the Convivio, De vulgari eloquentia and the poems of his early years in exile; and the Monarchia and the Commedia as the product of his maturity. Describing as it does a journey of the mind, the book confirms the nature of Dante’s undertaking as an exploration of what he himself speaks of as “maturity in the flame of love.”

The result is an original synthesis of Dante’s life and work.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gustav Sjöberg: una proposta

Neri Pozza propone un libro di poetologia, una sorta di attuale De vulgari eloquentia: La fiorente materia del tutto di Gustav Sjöberg, tradotto dal tedesco da Monica Ferrando.

Per sostenere una tesi veramente audace l’autore ha messo in piedi un coro di voci potentissimo, tale da far tremare la “cattedrale dell’arte” di Sklovskij: in un mondo dominato da un esperanto inadeguato a esprimere la complessità e la ricchezza delle culture del pianeta, attraverso la rete alla portata immediata di tutti, ma strutturata esclusivamente a una comunicazione di potere, la domanda di quale sia il compito della poesia (in quale lingua, con quale materia verbale?) è centrale. G.S., poeta il cui idioma materno (lo svedese) è condiviso da uno sparuto sei milioni di individui, avanza una sua proposta sulla base di una conoscenza profonda del pensiero occidentale e soprattutto del grande contributo offerto da quello italiano. L’autore ne dimostra una sorprendente conoscenza: in campo filosofico e letterario spazia da Dante fino ad Agamben, in quello visivo da Emilio Villa a Prini e affronta la questione appoggiandosi alla sponda di studiosi del calibro di Carchia e Melandri. Partendo da Dante e Campanella, la sua analisi poetologica prende le distanze con Giordano Bruno dal petrarchismo storico e, per rimanere all’attualità, dalla ”pappa omogeneizzata che si può modellare e tenere in forma nel modo più utile” (Jesi): la cultura di destra. Una qualsiasi sintesi di questo librino densissimo è un azzardo. Comunque…il suo obiettivo mi è sembrato quello di risuscitare un concetto di natura impostato dal grande nolano bruciato vivo appunto dal potere di allora: “non più subtrato passivo su cui si debba intervenire con un lavoro formale, bensì al contrario una molteplicità di forme che genera se stessa e con cui combacerebbe” (dall’introduzione della traduttrice). La questione è veramente complessa e rischia l’astrattezza in un mondo, l’attuale, in cui tutto (l’arte e la poesia in testa) è “destinato a edificare edifici funebri alle individualità che meglio si sono espresse” perché “…non è entrato nel corteo loquace della storia”. Personalmente, non essendo come lui “caduto sulla via di Nola”, mi limito a domandare: non è il vuoto assoluto che occorre perseguire, il vuoto per eccellenza, certo per prima cosa della materia del visivo che ha invaso di immagini il pianeta, ma anche della verbosità dilagante? Ma sempre il vuoto ha ancora un corpo, è ancora materia. E quale è la materia del vuoto in poesia? La morte in poesia si esorcizza con la perdita del controllo su di sé e questo forse è proprio un altro modo di esprimere l’abbandono alla fiorente materia del tutto. E’ senz’altro merito di S l’aver sottolineato con autorità e competenza l’importanza a questo proposito del pensiero del nolano. Fa piacere comunque che esistano persone che avanzano una coraggiosa proposta all’ipotesi che, per sottrarsi alla fagocitazione della cultura dilagante “nella società di mercato, sia necessario cessare di scrivere poesia”.

FDL

0 notes

Note

Totally talking out of my ass here (I'm not a philologist, nor a Renaissance specialist), but if you considered De vulgari eloquentia, maybe Dialogo delle lingue, by Sperone Speroni? And while I think about Sperone, he inspired La défense et illustration de la langue française, by Joachim du Bellay from La Pléiade (which opposes the idea of translating the French language)... But I think these works are more about the theory of language itself than the theory of translation… Maybe Etienne Dolet, still for the French language, with works such as Manière de bien traduire d'une langue à l'autre?

Oooh thank you very much!!!! I'll forward these to my sister 😊

1 note

·

View note