#Historia animalium

Text

For #GuineaPigAppreciationDay, the two earliest examples I've found of guinea pigs in the European visual record:

1. Painting attributed to Giovanni da Udine, n.d., artist active early 1500s to death in 1564

2. Drawing from the Felix Platter album, collected sometime between 1546-54

Attributed to Giovanni da Udine (Italian, 1487–1564)

Head of a Guinea Pig

oil on canvas laid on panel

6.5 x 7 in. (16.5 x 17.8 cm.)

From Duke's Fine Art Auction catalog, 11th April 2013, Lot 215

Drawing collected by Felix Platter, to be used in Gessner's Historiae animalium. The drawings were made by several artists, mostly anonymous, and were collected between 1546 and 1558 (this one must date to no later than 1554 as it served as a reference for Gessner's woodcut published that year). Bijzondere collectie Universiteit van Amsterdam collection.

#Guinea Pig Appreciation Day#guinea pig#cavy#cavies#European art#early modern European art#painting#oil painting#watercolor#illustration#historical sciart#scientific illustration#zoological illustration#natural history art#Felix Platter#Conrad Gessner#Historia animalium#16th century art#animal holiday#animals in art#Bijzondere collectie Universiteit van Amsterdam#auction#private collection

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A legendary bird from Librum Prodigiosum! The Cinnamologus, a bird which appears in various bestiaries including Aristotle’s Historia Animalium! Said to inhabit Arabia, these large birds build their nests out of cinnamon!

#digital art#digital illustration#fantasy#folklore#mythology#art#librum prodigiosum#monster#mythical creatures#creature#bird art#bird#Aristotle#cinnamon#cinnamologus#historia animalium#the nests must smell lovely#mythologyart

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

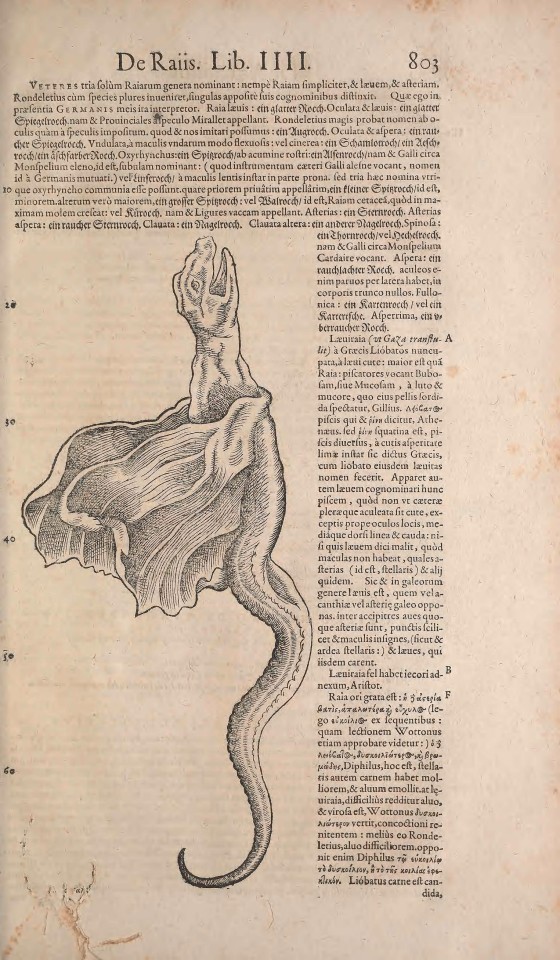

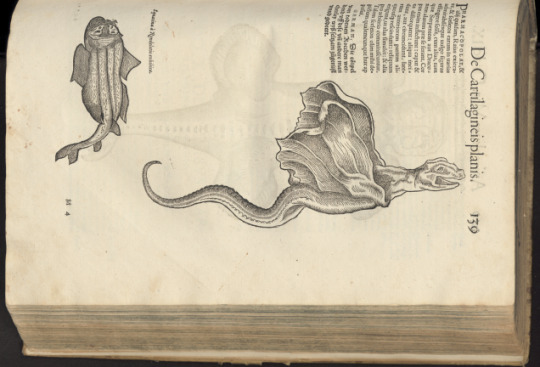

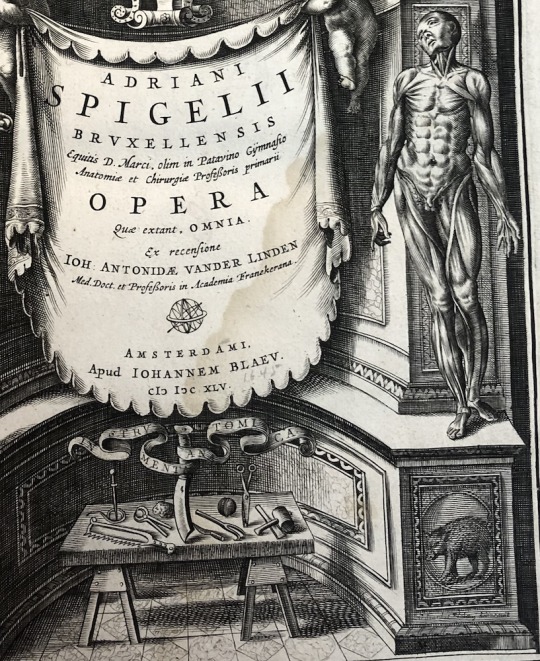

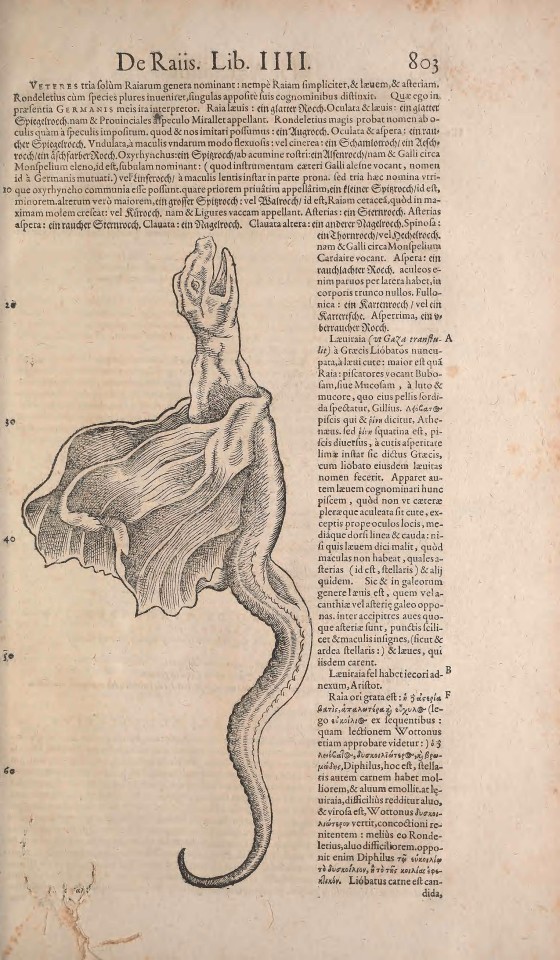

🧜♀️ Conradi Gesneri medici Tigurini Historiae animalium liber IV: . Francofurti: In Bibliopolio Andreae Cambieri, anno MDCIIII [1604].

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long-Beaked Jug with Paper Nautilus

Mycenaean, 1420-1370 BCE (Late Helladic IIIA1)

Objects seen in nature can be abbreviated into patterns and motifs that still evoke the whole. Three spiraling tentacles signify the paper nautilus (argonauta argo), a type of octopus; the motif is repeated three times around the body of the jug. The row of curving brown petals at the neck of the vessel mimics the unusual papery shell of the creature in shape and color, giving the illusion that the jug is the shell from which the tentacles emerge. The names for the octopus (nautilus and argonaut) are related to Greek terms for “sailor,” and in his treatise on animals (Historia Animalium), the late Classical philosopher Aristotle described the thin shell of this octopus as a boat, with tentacles as oars and sails.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jenny Haniver

Today i have something spooky for you. What looks like a creature from Alien is a so-called Jenny Haniver. These are preparations that are supposed to represent a dragon, an angel, a devil or even a sea creature.

Jenny Haniver, date unknown (x)

Where the name comes from is not clear, but it seems to have originated in France, where it was called jeune d'Anvers (girl from Antwerp) and presumably this is the starting point from where these figures were first made. The name was then changed by British sailors to Jenny Haniver and the usage spread to other countries.

Jenny Haniver as a little dragon, date unknown (x)

Traditionally, sailors carved such figures and then painted them. By selling these figures to visitors, compatriots and passing ships, they earned extra income. The earliest depiction of a Jenny Haniver appears in Konrad Gessner's Historia Animalium Volume 4 from 1558. At that time, it was assumed that these creatures were indeed real.

A Jenny Haniver in Konrad Gessner’s (1516-1565) Nomenclator aquatilium animantium, 1560 (x)

But Konrad explicitly pointed out that these figures were not small dragons or monsters, but rather taxidermied rays and guitar fish. In the end, they remained a popular whimsical collector's item (especially in Victorian times) and were also often the subject of good sailor's yarns.

#naval history#naval mythology#sailors handicraft#jenny haniver#sea monster#16th-19th century#maybe earlier#medieval seafaring#age of discovery#age of sail#age of steam

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Jenny Haniver is the carcass of a ray or a skate that has been modified by hand then dried, resulting in a mummified specimen intended to resemble a fanciful fictional creature, such as a demon or dragon.

One suggestion for the origin of the term was the French phrase jeune d'Anvers ("youth of Antwerp"). British sailors "cockneyed" this description into the personal name "Jenny Haniver".

Jenny Hanivers have been created to look like devils, angels and dragons. Some writers have suggested the sea monk may have been a Jenny Haniver. The earliest known picture of Jenny Haniver appeared in Konrad Gesner's Historia Animalium vol. IV in 1558. Gesner warned that these were merely disfigured rays and should not be believed to be miniature dragons or monsters, which was a popular misconception at the time.

The most common misconception was that Jenny Hanivers were basilisks. As basilisks were creatures that killed with merely a glance, no one could claim to know what one looks like. For this reason it was easy to pass off Jenny Hanivers as these creatures, which were still widely feared in the 16th century. In Veracruz, Jenny Hanivers are considered to have magical powers and are employed by curanderos in their rituals. This tradition is similar to one in Japan, where fake taxidermy ningyo (similar to Fiji mermaids) were produced and kept in temples.

Read More

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conrad Gessner (1516-65) - Le lièvre/The hare in Historia animalium, 5 vols 1551, 1558 and 1587.

© Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Fondation François Sommer, Paris

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

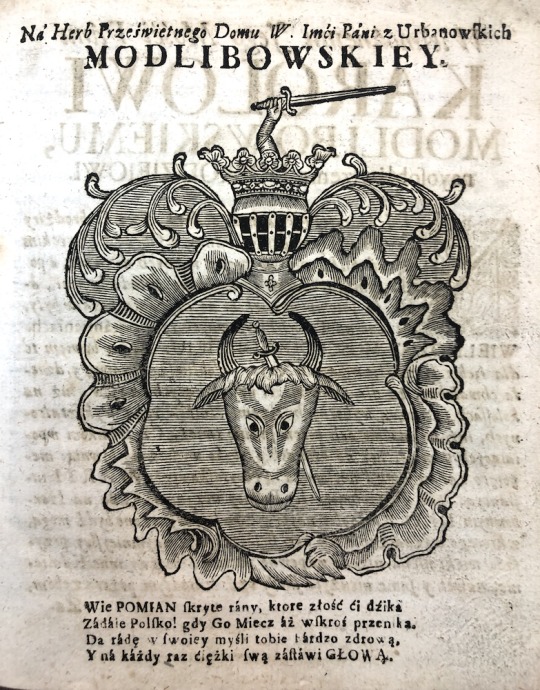

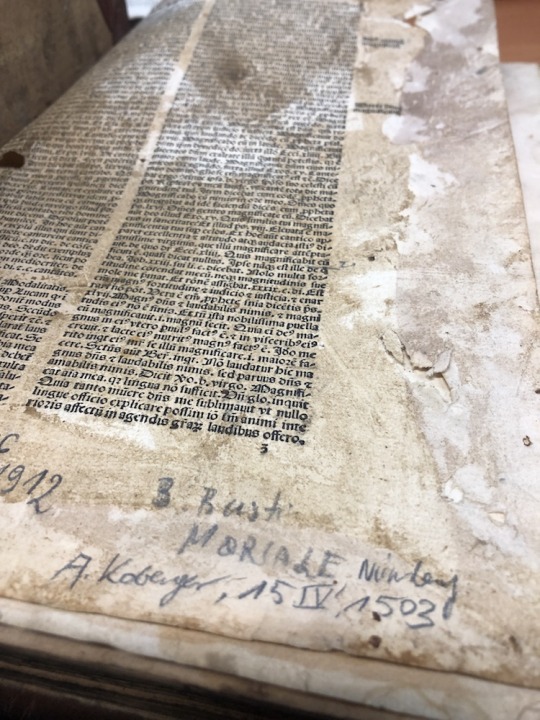

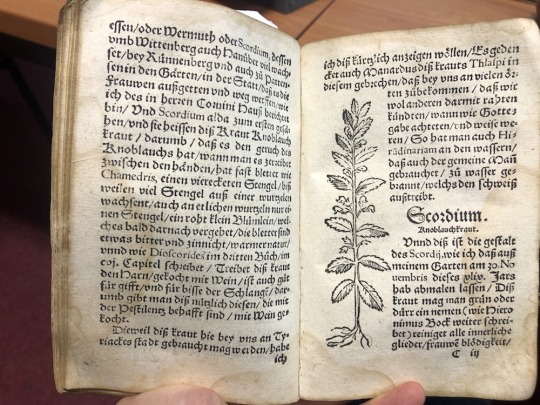

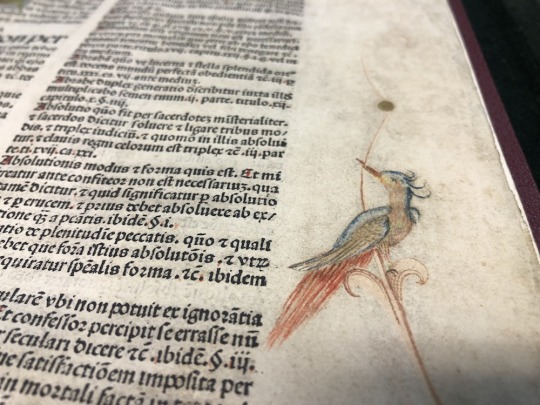

Dziś po raz pierwszy dotknęłam (w przeciągu godziny): starodruków, pergaminu i papieru czerpanego z XVII wieku (zrobionego ze starych szmat! To jest dopiero zero waste level pro). Chciałabym zobaczyć na własne oczy tę papiernię ze wsi Zawady koło Poznania, w której robiono taki papier z lnianych koszul w 1531 roku…

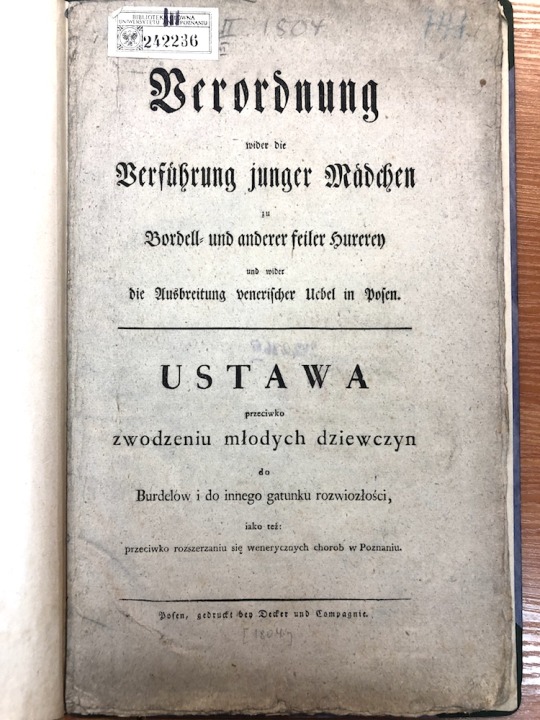

I muszę przyznać, że to co zobaczyłam tuż po dotknięciu tych szlachetnych papierów było jeszcze lepsze. Ręcznie malowany inicjał i floraturę! Odręczne dopiski na kartach z XVII wieku! Ścieżkę papierowego żywota XVI-wiecznego kornika! Faksymile pierwszego druku polskiego z najstarszej oficyny krakowskiej (to jest boski horoskop!). Skrytki w książkach! Miedzioryty w księdze „Nauka y informatia o strzelbie y o Rzeczach do niey należących”! Ustawę przeciwko zwodzeniu młodych dziewczyn z 1807 roku (osobliwe)!

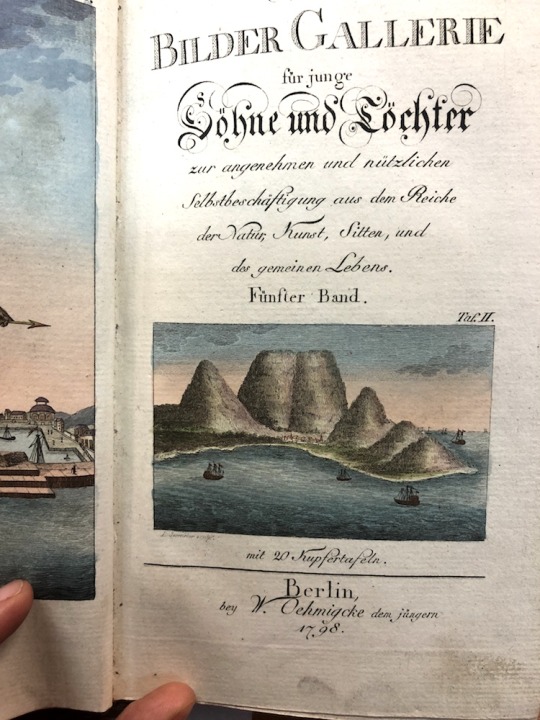

Bank rozbiło: „Obwieszczenie o Karach na Psujących Drzewa przy drogach zasadzone” z 1797 roku (skopiuję to i porozwieszam!), podręcznik kaligrafii z XVIII wieku oraz album o historii naturalnej „Historiae Animalium Liber II”. A o starodruku - wielkiej księdze, która jest atlasem anatomicznym - napiszę oddzielnie, bo to sztos.

Niesamowite jak trudno odróżnić rękopisy od niektórych inkunabułów. Czcionkę od pisania z ręki! I jakie to charakterystyczne, że papier, na którym drukowano w XVI czy XVII wieku jest trwalszy od tego, na którym drukujemy książki dzisiaj. Więc za parę wieków te starodruki znowu ktoś będzie oglądać, a o nas nie dowie się niczego, bo nasze książki pewnie nie przetrwają…

Chciałabym być zecerką w XVI-wiecznej drukarni…

#books#old books#inkunabuł#starodruk#biblioteka#skarby#old#paper#papier#floratura#inicjał#art#artwork#miedzioryty#drukarnia#papiernia#zecer#książki#sztuka#historia

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

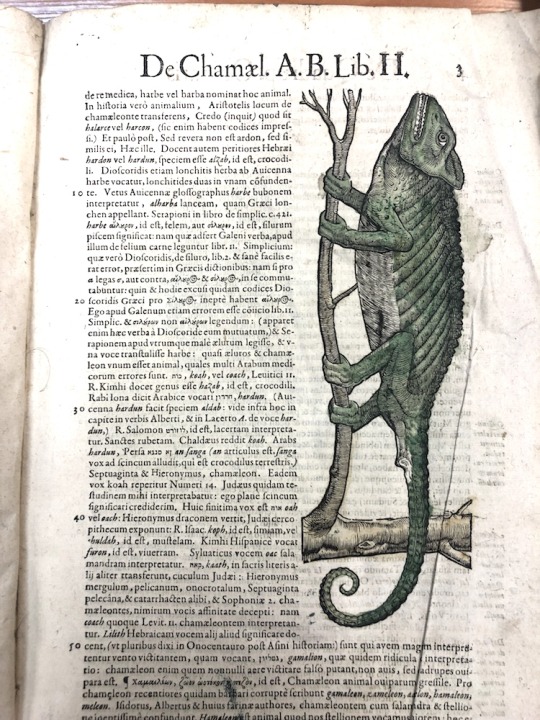

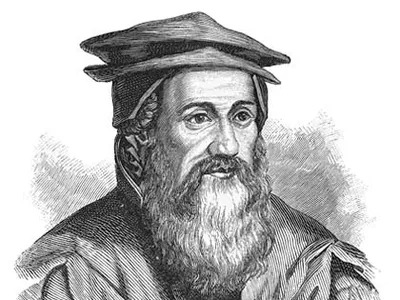

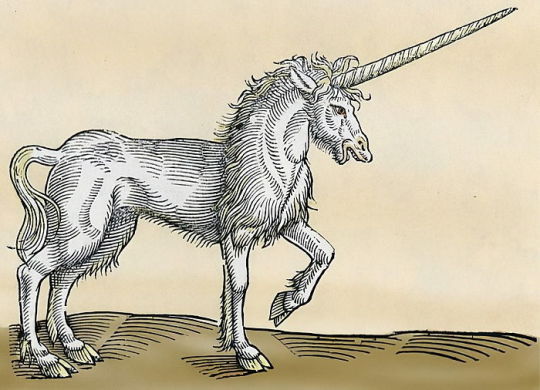

On This Day in Cryptid History

December 13th: In 1565, Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner died, known as the father of biology and author of Historiae Animalium, which featured cryptid-like creatures such as Unicorns, Sea Monsters and Dragons.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sea-Bishop

The sea bishop or bishop-fish was a type of sea monster reported in the 16th century. According to legend, it was taken to the King of Poland, who wished to keep it. It was also shown to a group of Catholic bishops, to whom the bishop-fish gestured, appealing to be released. They granted its wish, at which point it made the sign of the cross and disappeared into the sea.

Another was supposedly captured in the ocean near Germany in 1531. It refused to eat and died after three days. It was described and pictured in the fourth volume of Conrad Gesner's famous Historiae animalium, published in 1551 – 58 and 1587.

The Sea Monk, or sometimes Sea Bishop, was the name given to a sea animal found off the eastern coast of the Danish island of Zealand in 1546. It has also been sighted by two fishermen and some nearby swimmers in Pula, Croatia in the year 2011 and is one of the more popular sightings of the cryptid in the Adriatic sea. It was described as a "fish" that looked superficially like a monk. It was mentioned and pictured in the fourth volume of Conrad Gesner's famous Historia Animalium. Gesner also referenced a similar monster found in the Firth of Forth, according to Boethius, and a sighting off the coast of Poland in 1531.

The sea monk was subsequently popularized in Guillaume du Bartas's epic poem La Sepmaine; ou, Creation du monde, where the poet speaks of correspondences between land and sea:

"Seas have (as well as skies) Sun, Moon, and Stars; (As well as ayre) Swallows, and Rooks, and Stares; (As well as earth) Vines, Roses, Nettles, Millions, Pinks, Gilliflowers, Mushrooms, and many millions of other Plants lants (more rare and strange than these) As very fishes living in the Seas. And also Rams, Calfs, Horses, Hares, and Hogs, Wolves, Lions, Urchins, Elephants and Dogs, Yea, Men and Mayds; and (which I more admire) The mytred Bishopand the cowled Fryer; Whereof, examples, (but a few years since) Were shew'n the Norways, and Polonian Prince."

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conrad Gessner was born #OTD (Swiss,26 Mar 1516 - 13 Dec 1565). This creature, which Gessner dubbed a "Simivulpa" ("Ape-Fox"), was the only one of the newly reported American animals included in his 1st edition of Historia animalium in 1551, considered a foundational text of modern zoology. Do you know what animal it actually was? 🤔

Hint: Gessner's illustration is based on this 1516 map icon, its earliest known European image. The caption reads: "An animal that looks like this is found here; it has a bag under its belly where it carries its offspring. One such animal was given to the King of Spain in Granada."

Another hint: This wildly inaccurate image was the result of Europeans attempting to illustrate a "new" animal based on second-hand reports of its appearance, which usually involved the "jigsaw animal" narrative. in this case, contemporary published accounts of the 1499-1500 voyage of Vicente Yáñez Pinzón (Spanish, c.1462-c.1514), during which the first known exploration of Brazil was made, described the first encounter with the animal like this: "Between these Trees he saw as strange a Monster, its foremost part resembling a Fox, the hinder a Monkey, the Feet were like a Mans, with Ears like an Owl; under whose Belly hung a great Bag, in which it carry'd the Young, which they drop not, nor forsake till they can feed themselves." [Translation from John Ogilby, America: Being the Latest, and Most Accurate Description of the New World (London, 1671), 59.]

To find out the mystery animal's true identity, click here.

#Conrad Gessner#Historia animalium#book illustration#map illustration#book plate#map icon#16th century art#natural history art#scientific illustration#zoological illustration#zoology#history of science#“New World”#Vicente Yáñez Pinzón#European art#mystery animal

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

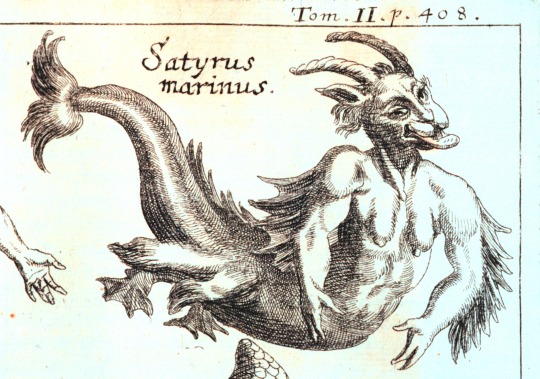

Satyrus marinus, or the marine satyr [17th century Europe]

Supposedly, a strange aquatic creature was spotted on the coast of Sibenik, a city in Illyria, which is a historical region in what is now the western Balkans (Sibenik is now a city in Croatia). The being was slightly humanoid and had two legs, each of which ended in a fish-like tail. From these tails, a wing-like membrane sprouted that ran up all the way to the creature’s arms and was compared with the wings of a bat. Although presumably, they were fins meant for swimming rather than flying. The creature had two arms, each of which ended in a hand with two fingers.

Its head resembled that of a human, but it was adorned with two small horns. The being’s skin resembled that of an eel. It was attempting to drag a boy into the sea, but it was seen by locals before it could accomplish this. The people banded together and the mob beat the creature with clubs and stones before dragging it onto dry land. It is unknown what became of the mysterious creature.

You have probably noticed that the accompanying image only barely matches the description. In fact, I believe it was added as an illustration of a general humanoid sea monster and it might have been a coincidence that it matched the description of the creature from Sibenik, because the monster from the text is never explicitly referred to as “Satyrus marinus”. The image appeared in Schott’s Physica Curiosa, a book that predated Zahn’s work by 30 years. The Satyrus marinus is mentioned here, but only briefly, and no details are given on the creature. Both authors reproduced the image from the 1642 Monstrorum Historia.

I was overjoyed to find that the Monstrorum historia does contain a passage on the marine satyr, after the other authors seemed to have no information on this enigmatic creature at all. I might be making a translation error here, since I’m not exactly fluent in Latin, but if I understand it correctly, Aldrovandus claimed that the term ‘triton’ (which originally referred to a singular character from Greek mythology, but the name was later used to refer to merpeople in general) is used as an all-encompassing term for marine human-like creatures that includes the satyrs.

Aldrovandus wrote that these aquatic satyrs were commonly assumed to be non-existent by scholars and that sightings of these creatures were actually of diving swimmers and fishermen. However, he also highlighted that there are several learned authors who believe that “marine satyrs” do exist in the sea. Supposedly, these creatures lived in the seas surrounding Sri Lanka – which was known as Taprobana by the ancient Greeks and referred to as such by Aldrovandus – where they inhabited the tropical waters. But the marine satyrs – or similar creatures – were supposedly also spotted in the Nile delta in Egypt. A group of men supposedly saw a pair of these beings emerging from the water: one of them was bearded and male, while the other had no facial hair and was assumed to be female. They received the appellation of “Nile monsters”.

There is also a claim that the local people of Dalmatia – which is part of Croatia – used to capture and kill these creatures (or similar creatures) to take their skin, as their eel-like skin was very strong and could be used to fashion shoes that would last over 15 years. There are probably some ethical complications there, but the shoes were of a high quality.

Sources:

Zahn, J., 1696, Specula physico-mathematico-historica notabilium ac mirabilium sciendorum: in qua mundi mirabilis oeconomia, nec non mirificè amplus, et magnificus ejusdem abditè reconditus, nunc autem ad lucem protractus, ac ad varias perfacili method acquirendas scientias in epitomen collectus thesaurus curiosis omnibus cosmosophis inspectandus proponitur.

Schott, G. P., 1662, Physica curiosa, sive mirabilia naturae et artis libris XIII. Which you can read here.

Aldrovandus, U., 1642, Monstrorum historia cum paralipomenis historiae omnium animalium, which you can read here.

(image source: Specula physico-mathematico-historica notabilium ac mirabilium sciendorum, Johann Zahn, 1696. Image taken from Wikipedia, as it’s a much higher quality than the scanned copy of the book which is available to me)

#mythical creatures#miscellaneous#mythology#cryptids#cryptozoology#medieval#well not actually medieval#aquatic#monsters#creatures

61 notes

·

View notes

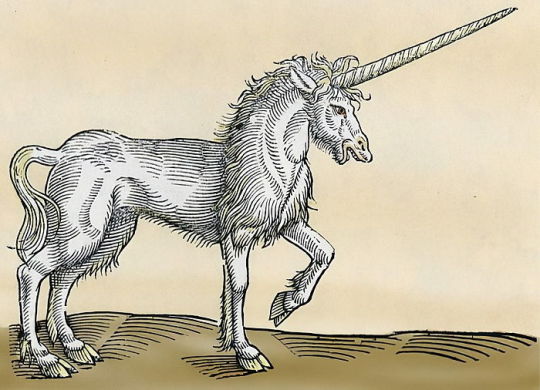

Photo

Unicorn, illustration from Historiae Animalium by Conrad Gesner, 1551

#unicorn#einhorn#fantasy#illustration#conrad gesner#culture#medieval#legend#mythology#fantasie#creature#animal#histroy#mythical#animalum#zoology#art#artwork#kunst

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🧜♀️ Conradi Gesneri medici Tigurini Historiae animalium liber IV: . Francofurti: In Bibliopolio Andreae Cambieri, anno MDCIIII [1604].

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Las pardelas son un grupo de aves pelágicas de la familia Procellariidae de tamaño medio y provistas de largas alas. Existen más de 20 especies de pardelas, las más grandes del género Calonectris y muchas especies pequeñas del género Puffinus, y del reciente género Ardenna. Las aves del género Procellaria se consideraban dentro de este grupo, pero basándose en estudios recientes se descubrió que no están tan relacionados como las aves del género Pseudobulweria y Lugensa que tomaron su lugar.1 El género Puffinus puede ser dividido en un grupo de especies pequeñas cercanas al género Calonectris y otras más grandes distantes a ambos.2

Estas aves son más comunes en aguas templadas y heladas. Son pelágicas fuera de la temporada de cría. Vuelan con largas alas planeando en el aire con el mínimo esfuerzo y recorriendo grandes distancias. Algunas especies pequeñas, como la pardela pichoneta son cruciformes en vuelo, con su ala larga sostenida directamente hacia fuera de sus cuerpos.

Pueden llegar a vivir muchos años. Una pardela sombría que anida en las islas Copeland, Irlanda del Norte, era entre 2003 y 2004 el ave más antigua en libertad del mundo: se lleva control de ella después que la anillaron, ya adulta (por lo menos tenía 5 años) en julio de 1953, y fue atrapada una segunda vez en julio de 2003, teniendo por lo menos 55 años. Las pardelas sombrías migran 10 000 km hasta Sudamérica en invierno, llegando al del sur de Brasil y a Argentina; entonces la pardela sombría de las islas Copeland ha recorrido un mínimo de 1.000.000 de kilómetros en su vida, sin contar lo que vuela en el día.

Las pardelas van a las islas y a los acantilados solamente a anidar. Tienen costumbres nocturnas para anidar, prefiriendo las noches sin luna para minimizar la depredación. Anidan en madrigueras donde ponen un solo huevo blanco.

Se alimentan de pescado, calamares y alimentos similares que el océano le otorga, aunque algunos pueden seguir a los botes pesqueros para comerse las partes de la pesca que se va por la borda. La fárdela negra muchas veces sigue a las ballenas para alimentarse de los peces que se asoman a la superficie luego de su paso.

Datos científicos demuestran, su situación crítica de conservación principalmente debido a la introducción de predadores en sus lugares de cría (por ej. ratas y gatos), la contaminación lumínica, la sobrexplotación pesquera y la interacción con pesquerías industriales.3 La contaminación marina y concretamente la ingesta de plástico es otra amenaza importante pues puede provocar el bloqueo del tubo digestivo, úlceras e incluso transferir contaminantes a los tejidos de las aves. En algunas especies se han registrado 276 piezas de plástico dentro de un polluelo de 90 días, siendo el 15% de su masa corporal. Esto traducido en términos humanos, sería al equivalente en una persona a tener alrededor de 6 u 8 kilos de plástico dentro del estómago.

Las pardelas son parte de la familia Procellariidae, que también incluye a los petreles fulmares, priones y fardelas.

La pardela ha sido declarada "Ave del Año 2013" por SEO BirdLife.

Curiosidades[editar]

Claudio Eliano incluye un pequeño relato sobre la pardela en el Libro I de su obra sobre la naturaleza de los animales (en griego: Περὶ ζῴων ἰδιότητος Perí zóon idiótitos; aunque citado a veces por su título en latín, De Natura Animalium o Historia animalium). Según cuenta, esta ave vive en la isla Diomedea o Diomedia, no ataca a los bárbaros pero se mantiene alejada de ellos, en cambio, a los helenos (o griegos) los recibe amistosamente. Eliano expresa que la especial relación entre estas aves y los helenos se debe al héroe tracio Diomedes (en griego: Διομήδης); éste las tenía por compañeras de viaje, pues según cuenta el autor, se trataban de combatientes caídos durante la guerra de Troya que aun lo acompañan pero metamorfoseados en pardelas.

En el Compendio de metamorfosis de Antonino Liberal se dice que el origen de estas aves deviene de una rebelión de los daunios. Éstos fueron ayudados por Diomedes en una guerra contra los mesapios. Tras la victoria, Daunio, rey de los daunios, en agradecimiento, casó a su hija con el héroe tracio y le concedió tierras que más tarde repartió entre sus compañeros dorios. Muerto Diomedes y muerto Daunio; los daunios, envidiosos de las tierras de los dorios, instigaron una revuelta en la que acabaron masacrándolos. Zeus en compensación por esa atrocidad, transformó a los griegos asesinados en pardelas. Esta historia sirve como explicación del motivo que también expresa Eliano: que estas aves reciben a los griegos y rehúyen a los bárbaros.

En su cuaderno de bitácora, a fecha del 4 de octubre de 1492, Cristóbal Colón se refiere al avistamiento de más de cuarenta "pardeles".

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unicorn, illustration from Historiae Animalium by Conrad Gesner, 1551

0 notes