#1870s britain

Text

Lilac silk afternoon dress, 1872-1875, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#lilac#purple#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#19th century#Britain#1872#V&A#1870s#1870s dress#1870s extant garment#1870s britain#afternoon dress

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Everett Millais (1829-1896)

"The North-West Passage" (1874)

Oil on canvas

Pre-Raphaelite

Located in the Tate Britain, London, England

The painting depicts an elderly sailor sitting at a desk, with his daughter seated in a stool beside him. He stares out at the viewer, while she reads from a log-book. On the desk is a large chart depicting complex passageways between incompletely charted islands.

Millais exhibited the painting with the subtitle "It might be done and England should do it", a line imagined to be spoken by the aged sailor. The title and subtitle refer to the repeated failure of British expeditions to find the Northwest Passage, a navigable passageway around the north of the American continent. These expeditions "became synonymous with failure, adversity and death, with men and ships battling against hopeless odds in a frozen wilderness."

The search for the northwest passage had been undertaken repeatedly since the voyages of Henry Hudson in the early 17th century. The most significant attempt was the 1845 expedition led by John Franklin, which had disappeared, apparently without trace. Subsequent expeditions had found evidence that Franklin's two ships had become stuck in ice, and that the crews had died over a number of years from various causes, some having made unsuccessful attempts to escape across the ice. These later expeditions were also unable to navigate a route between Canada and the Arctic. Millais had the idea for the painting when a new expedition to explore the passage, the British Arctic Expedition led by George Nares, was being prepared.

#paintings#art#artwork#genre painting#genre scene#john everett millais#oil on canvas#fine art#pre raphaelite#pre raphaelism#tate britain#museum#art gallery#history#art analysis#northwest passage#exploration#1870s#late 1800s#late 19th century#interior#clothing#clothes#male portrait#portrait of a man#female portrait#portrait of a woman#father and daughter

228 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia with her sister Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, during Russian state visit in 1873.

#Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia#Empress Maria of Russia#Empress Maria Feodorovna#Empress Maria#princess dagmar of denmark#Queen Alexandra of Great Britain#Queen Alexandra of United Kingdom#Queen Alexandra#princess alexandra of denmark#Princess Alexandra of Wales#Tsarevna Maria#Princess of Wales#1870s#1873#1870s fashion#victorian#romanovs#imperial russia#Imperial Family#british royal family#british royals#British Royalty#denmark royalty#denmark royals#Dagmar of Denmark#alexandra of denmark#history colored#digital coloring#colored photography#b&w picture coloring

241 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wardrobe designed by Christopher Dresser, c. 1876

#furniture#wood#gold#woodwork#frogs#amphibians#animals#Britain#Christopher Dresser#this is so cool#fav#victorian#19th century#1870s

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer by John Atkinson Grimshaw, 1875

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Glens Falls to Chester: The Mills family in the Adirondacks

This was originally the second chapter in my family history on the Mills family, but has been adapted and changed for this blog. All the sources are noted in a bibliographic essay at the end of this post, with maps and other photos throughout. Enjoy! This was originally posted on the WordPress version of this post. It has been split in a few posts so it is more readable on here.

By 1860, the Mills family was still in Bolton. John Mills was said to be 54 years old, still a miller, and his wife Margaret, age 36, was listed as a housekeeper. There were nine children in the household. Two of them, Joseph B., age 18, and Thomas, age 14, were farm laborers, presupposing that the Mills family owned a farm in Bolton. While Hetabella, age 18, did housework, the other children seemed to be too young to be listed with occupations. They included Edward (age 12), Dory A (age 10), Mary J (age 6), John C (age 4), Margaret E (age 3) and Benjamin W. (age 3/12). Bolton was similar to what it was in 1855, still undoubtedly having an agricultural and working-class character.

Four years later, in 1864, a woman named Margaret E. Mills declared loyalty to US, withdrawing loyalty to Great Britain and Ireland. This woman is likely Margaret Bibby. Unfortunately she did not state her age or place of birth.

The following year, 1865, the Mills family had moved back to Chester. John Mills was a 60-year-old farmer with his wife Margaret, 40 years old. This is the first census which states the number of John and Margaret’s children, which numbers 12! Within the household in the frame house, were 10 children, meaning that two of her children were not in the household. The names of those two children are not currently known. This census was the first to name Robert B. Mills, a person who was 2 ½ years old. Others in the household included Hattie B. Mills (age 21), Joseph B Mills (age 20), Thomas Mills (age 18), Edward Mills (age 18), Dora A. Mills (age 14), Mary J. Mills (age 9), John C. Mills (age 7), Margaret E Mills (age 5), and William Mills (age 4). With such a big family, it is likely that Hattie (same as Hetabella) took care of the family, especially Dora, Mary, John C., Margaret E., and William, who were younger than her. Joseph B. and Thomas likely worked on the farm with their father. This can only be inferred as the census does not state this directly.

Chester seemed to the same in some respects as it was when the Mills family lived there in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Nearby to the Mills family was the family of George Bibby. He was a 46-year-old farmer born in Ireland, with a family of six: his wife Ann born in the county, age 30, has five children, now married; Helen, age 9, Katherine, age 7, Samuel, age 6, William, age 4, and George, age 1 and 8/12. Also living in the household is his father, Samuel Bibby, age 67, born in Ireland, a laborer.

Another family nearby was Thomas Bibby’s family, living in the household of the Wallaces. Hewas age 28, born in Ireland, a farmer and married to someone named Mary A. Bibby (age 25, born in Warren). There is also a family of Thomas Mills (age 59, born in Ireland, farmer) nearby who has a wife named Margaret (age 53, born in Ireland, has 12 children), John (age 23), Edward L (age 21), Margaret (age 19), Phebe (age 15), Thomas J (age 11), and Ellen Gray (sister, age 60, born in Ireland). It is not known if any of the Mills children were living with these individuals at the time, but is likely that they were living somewhere in Chester.

By 1870, the Mills family was still living in Chester. John Mills was a 66-year-old farmer married to Margaret, age 48. In the household was their 23-year-old son, Joseph B., a carpenter, their 21-year-old son, Edward E, a farm laborer, and their 19-year-old daughter, Dora A, a teacher. At home were the rest of the children, Mary J (age 17), John C (age 14), Maggie (age 11), Willie or William (age 7), and Robert or RBM II (age 5). Both John and Margaret noted that they had parents of foreign birth. Also on the same page was Samuel Bibby (age 73 born in Ireland), Thomas Mills (age 64, farmer, born in Ireland), his wife Margaret (age 57, born in Ireland), Thomas Bibby (age 34, born in Ireland).

As the years passed by, John and Margaret were getting older. As her Find A Grave entry reports, since she has no visible gravestone photo, she died in 1874 in Minerva, Essex County, New York. This cannot be disproved or proven by any records on the subject.

The 1875 census shows a 70-year-old John Mills still living in Chester, as a farmer, with seven children in the household. These included his son Joseph B, a 29-year-old millwright, his daughter Dora, 24-years-old, his daughter Mary, 21-years-old, his son John C, 18-years-old, his daughter Maggy, 16-years-old, his son William, 14-year-old, and his daughter Hattie, 31-years-old. The latter was married to a 37-year-old carpenter named Hannibal Hammond and had a 12-year-old child named Ellen. It is important to note that Margaret is not in the household, so from this record, her death date can be ante 1875, or more accurately sometime between 1870 and 1875. While the census takers could have missed her, considering she was in every since census since 1850 seems to indicate that she was not alive.

The families of Isaac Mills and George Bibby were also living in the area. Isaac Mills’s family consists of: Isaac (born in Ireland, age 62, farmer), Ann (wife, age 46, born in Ireland), Joseph W (age 26, born in Warren, farmer?), Edward B? (farmer? Age 24, born in Warren), Mary (age 21, born in Warren), James O (age 20, born in Warren). George Bibby’s family consists of: George (age 53, farmer, born in Ireland), Ann (wife, age 40, born in Warren), Ellen (age 20, born in Warren), Caty (age 20, born in Warren), Samuel (age 16, born in Warren), William B (age 18, born in Warren), Albert (age 8, born in Warren), Humbert, (8 11/12 months, born in Warren), and Samuel (father, age 78, born in Ireland, likely a farmer of some type). These two families may have been connected together by marriage or even Isaac could have been John Mills’s brother. Sadly, those specifics are not completely known.

In 1876, John Mills died in Minerva, Essex County, New York, apparently while he continued his job as a miller. I have contacted appropriate historical societies in hopes of gathering more information. It is possible that Mills family members were living in that area of New York, or even Bibby family members since his wife Margaret was buried there. Perhaps she was going on a trip to bisit her cousins or even her parents. We don’t know exactly but can only make historical suppositions.

To this day, the Warren County Historian’s Office has family files on the Mills and Bibby families. 17 individuals with the Mills surname living in Ireland (mainly in Cork) and two with the Bibby surname were living near or around Kilkenny at the time (1876).

By 1876, with the death of John Mills, the twelve children he fathered with his wife Margaret, were on their own. Each of them would chart their own, independent path. As Charles Frederic Goss wrote many years later, RBM I, was only 10 (or 12) when his father died. This likely had a strong psychological effect on him, as it would on anyone, especially one who is that young. It meant that those such as RBM I, his brother William, and other younger siblings had to make their own way.

By 1876, Dora was only 25-years-old, if we use the age in the 1875 census. She likely did not even know of the Packard family in Massachusetts or of a man named Cyrus Winfield Packard, who was only 24 at the time, and would later be her husband. She had not, like Cyrus, run away from home at a young age. This is not because she worked more than Cyrus, who came from a family of hard-working farmers who had roots dating back to Samuel Packard, an immigrant from England in 1638, and had moved from eastern Massachusetts, mainly in Bridgewater, to Western Massachusetts, specifically in Cummington and Plainfield. Instead, she possibly found at least some value in her life as a teacher and likely helping around the home (and probably the farm). This would serve her well in years to come.

© 2018-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#mills family#packard family#mills#packard#genealogy#family history#1870s#1638#immigration#settler colonialism#early settler#settler violence#1830s#1840s#1860s#19th century#massachusetts#ireland#britain#marriage#family#households

0 notes

Note

what are your thoughts on tertius lydgate wrt marking shifts in discourses of medicine? his position in the novel fascinated me as someone who feels very strongly about the role of doctors in society, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the matter

YES lydgate rules so hard in my personal pantheon of doctor characters. sorry this has been in my inbox for a thousand years i had was rotating.

so first of all one of the things that makes 'middlemarch' interesting is that it's a historical novel. so, when george eliot creates a doctor character for the year 1829, writing from 40 or so years later, she's using him to comment on (her perception of) changes to medical science in britain over the course of several decades. so for instance, the fact that lydgate trained in edinburgh and paris tells us immediately that we're supposed to understand him not just as a member of a newly 'respectable' profession, but specifically as having a viewpoint that is informed by radical student politics (edinburgh) and conceptions of the doctor as a social reformer (paris) as well as the research traditions of raspail and bichat. indeed this is why lydgate's crusade in town includes his ideas about sanitation and public health; in contradistinction to the other physicians, he sees his medical and scientific authority as giving him the ability and responsibility to reform the town more broadly. like his parisian counterparts, lydgate clearly sees a link between, eg, cholera and more general social and political unrest. he fashions himself as someone who can doctor the social body as much as the individual patient; given his parisian training we can place him loosely in a social-hygienist context here.

lydgate is also a pretty early example in british literature of a doctor character who's presented as a) not a charlatan and b) heroic explicitly on the basis of his medical and scientific status. british medical practitioners were subject to a new licensure requirement in 1815 i believe (i'd have to double check this date i don't read as much in 19thc britain); 'middlemarch' was written around 1870 and set in 1829–32. so, for eliot, lydgate was genuinely part of a markedly new wave of physicians—men who were licensed (read: state-approved) and occupied a new social position. lydgate is also minor aristocracy, which is part of what makes it possible for him to scoff at the town's older physicians, but much of his social position in the town is accrued in conjunction with the newly and increasingly prestigious status of his profession. this is not really a character type that would have been plausible in a realist novel set in the same country a generation or two earlier.

eliot herself was married to a man of science and also kept abreast of medical and scientific ideas (for example, she was extremely interested in phrenology, an influence you can see throughout 'middlemarch'), and lydgate is very much a man of the times in this respect: he diagnoses george's scarlet fever in the early stage, for example, and refuses to dispense his own prescriptions or to take money from pharmacists. these, along with his emphasis on public health and sanitation measures, mark him as not just an idealist but someone whose medical practice was genuinely steeped in current principles of scientific and ethical reform. even his embrace of bichat's tissue theory, though presented somewhat vaguely, would have signalled to a reader familiar with recent anatomical theories that lydgate was not just a fashionable thinker (bichat died in about 1802, but his work came to popularity over the next 3-4 decades in england and france) but also a precise and naturalistic one, aligning himself with a research tradition that emphasised specific, local lesions as etiological agents (compare this to the brain-localisation ideas of the phrenologists).

ultimately, lydgate's tragedy is that his medical knowledge isn't matched by any social acuity, and his match with rosamond is dissatisfying for both of them. i don't read this as eliot condemning the aspirational early stages of lydgate's career; his mistakes are all made in the interpersonal arena, with both rosamond and the raffles affair. had he played these situations smarter, who knows what he may or may not have accomplished for the residents of middlemarch. instead, he ends the book as a successful but dissatisfied physician to the wealthy, in a position of financial security and medical specialisation but without the kind of moral or political status that he sought earlier in the book by presenting himself as both a social and medical reformer. eliot thus engages, i think, another new type of doctor character: lydgate at the end of the book still has no trace of the quackery or charlatanism that characterised many previous representations of doctors, but he's also been purged of the youthful idealism that pervaded the edinburgh and paris medical education he received. the social status he attains at the end of his life is based on his wealth and the general respectability of the medical profession; treating gout doesn't give him any higher prestige than that, and certainly not the kind of moral authority or fulfillment he wanted back in middlemarch.

so, and recognising that this sort of leaves aside a lot of the psychological nuance of the novel, lydgate's storyline gets at two of the major historical points eliot is interested in. first there's the changing status of british medicine and medical practitioners. lydgate begins the novel as the self-styled hero-reformer; experiences a social fall from grace that compounds with the resistance he already faces from the other town physicians for the threat he poses to their professional status; and ends as the consummate specialist, performing the same boring, lucrative work day in and day out for wealthy londoners (note also the use of gout here to indicate a high degree of moral lassitude and overconsumption among his patients, lol). secondly, and relatedly, there's a shift in class positions going on here. lydgate's initial position in middlemarch is as minor (not wealthy) nobility; by the end of the book he's in a newly high-status professional class, has gained more wealth (though ofc not enough for rosamond), and has been forced out of the countryside. this all tracks with both the expansion of cities generally in this period, and the strengthening of the middle class / petit bourgeois (consider the 1832 reform bill).

although eliot's own views about medicine were largely concordent with the kind of positivistic naturalism of her peers (see again her interest in phrenology), part of what she does with lydgate is, i think, intended as a warning: here's a confluence of forces that have turned an idealistic public health reformer into a dissatisfied man pursuing his personal material security at the direct expense of his philanthropic and altruistic aims. it's a success story for the medical profession in many ways (financially, reputationally) but also a tragedy in the eyes of anyone who believes that physicians ought to have more responsibility to their patients and their polities than their pocketbooks. we're meant to understand medicine as not just a personal curative, but potentially a socially enlightening force---but, only if its aspirations in this direction aren't hindered by the very forces turning it into a more respectable and lucrative career for the rising professional class.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Many Faces of Ophelia

John Everett Millais • Ophelia • 1851–52 • Tate Britain, London

Millais's painting depicts Ophelia, a character from William Shakespeare's play Hamlet, singing before she drowns in a river.

Pierre Auguste Cot ( French, 1837-1883) • Ophelia (Pause for Thought) • 1870 • Private collection

Another haunting version of Ophelia belongs to the French portraitist Pierre Auguste Cot, well-known for his portraits and romantic scenes. The painting is not a direct illustration of Hamlet, but rather a glimpse into the dark and terrifying mind of Ophelia after Hamlet refused to marry her and then killed her father Polonius. What might seem to be an innocent look of a young maiden, looks downright creepy and unsettling, hinting at Ophelia’s soon-to-come decision to take her own life out of grief and madness.

Odilon Redon (French, 1840-1916) • Ophelia Among the Flowers • c. 1905-08 • National Gallery, London

Redon’s version of the story is in no way an illustration of the original text written by Shakespeare, but rather a dreamlike impression of it.

Ophelia • Sarah Bernhardt • 1880

Sarah Bernhardt's version, perhaps too idealized to be a direct reference to Shakespeare’s text but nevertheless has one important feature. If we look at the photographs of Bernhardt, we can recognize her own facial features in her depiction of Ophelia. In fact, Bernhardt did play Ophelia on stage in 1886, only six years after making the piece. During the production, she insisted on developing her role further. Instead of the death of Ophelia being indicated by a closed coffin carried out to the stage, Bernhardt was brought to the public, playing a lifeless body herself.

Paul Albert Steck ( 1866-1924) • Ophelia • 1895 • Musées de Paris

John William Waterhouse (British) • Ophelia • 1910 • Private collection

"Her clothes, stretched out, carrying her like a nymph; which time she chanted snatches of songs he sang as if knew not troubles or was born in the element of water; so to last could not, and apparel, hard upivshis, unhappy from the sounds of dragged into the quagmire of death." ~William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Paul Delaroche (French, 1797-1856) • La Jeune Martyre (The Young Martyr/Ophelia) • 1855 • Musée du Louvre, Paris

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889) • Ophelia • 1883 • Private collection.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), The Death of Ophelia (1853) • Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Theodor van der Beek (German, 1838-1921) • Ophelia • 1901 • Private collection

#ophelia#william shakespere#art#painting#fine art#art history#literary painting#hamlet#german artist#french artist#eugène delacroix#theodore van der beek#alexander cabanel#john william waterhouse#paul delaroche#paul steck#pierre auguste cot#british artist#odilon redon#sarah bernhardt#sculpture#oil on canvas#john everett millais

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

I LOVE the historical context you add to tom riddle meta. im curious. at that time how important and wealthy would tom riddle sr likely have been? i.e. how nice was the life that Tom missed out on by growing up in the orphanage instead of with his dad?

Omg thanks so much!

We don't actually know much about the Riddles. They likely lived in Yorkshire, Lancashire, or the very west of Cornwall (200 miles from Surrey as per Goblet of Fire), but I think it's more likely they lived in the North, specifically in Yorkshire. The Riddle's name is probably locational rather than profession based, and from a village called Ryedale in the North Riding of Yorkshire. It was probably mutated over time because spelling wasn't standardised or even close to standardisation when last names were beginning to become a thing (roughly 11th century in Britain).

Okay, now the reason I went into that is because I believe the Riddles were the big guys back in the day (by which I mean late medieval period c. 1100s until the late 1500s) and were the kind of wealthy landowners who employed serfdom potentially even past the Peasant's Revolt of 1381. I know a lot of people place them as merchants who made money from trade but based on their name and location (Yorkshire is famous for its sheep) I think it's more likely they were landowners. They probably had pretty solid generational wealth, potentially even being landed gentry (a class of gentry who made their money on leasing land and known as lords of the manor), although I'm fairly certain they lost most of this later. I don't think they ever were part of the peerage (the level above gentry in the British aristocracy who hold hereditary titles) but gentry usually married into peerage and vis versa so they were likely quite connected despite never being "Lords" themselves. They got their name through their association with the village as the big whigs.

Even if the Riddles had kept up serfdom for a century or so after the Peasants Revolt (entirely plausible), serfdom was abolished by Elizabeth I in 1574. Whenever they stopped working as part of the feudal system, I don't think it had major impacts on their wealth. Like I mentioned above, they were probable landed gentry, making their money by leasing out land and still profiting off the lower classes.

With the Industrial Revolution and the Agricultural Depression of the 1870s, I think they would've lost quite a bit of money, potentially even their place as landed gentry. They would've still been quite rich, but their wealth was probably in decline and they had to look elsewhere. Maybe they never succeeded in this.

The thing is, we know next to nothing about the Riddles and the family we see through Tom Riddle's eyes is one that's lost status and connections because of the scandal of Riddle Snr. having run off with Merope without being married and (rumours have it!) having a child out of wedlock. The Riddle family probably declined economically with WWII (and to a lesser extent WWI) as well, although they never got a chance to really see the era through properly due to their… untimely deaths.

I think if Tom had been raised by the Riddles, they may not have fallen so far, providing Riddle Snr. married Merope before her death, or at least had falsified documents that he did. Tom would've still grown up in declining wealth, but more than enough money still to not have to work. Life for Tom would've been far better, what without starvation, disease, poverty and later, bombs and would've remain largely untouched by the war. The Great Depression wouldn't have it so hard, and Tom, not being surrounded by so much death, would've been fundamentally altered. I'm not sure what the Riddle's reaction to Tom being magic would've been like, but I'll leave that to any writers. All in all, Tom missed out on a far better life.

Thank you so much for the ask! It really made my day!!

#tom riddle#tom marvolo riddle#hp meta#harry potter headcannons#riddle family#land ownership is a headache#also why were there so many agricultural revolutions??#tom riddle meta#harry potter meta#ask#anon ask

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Purple silk day dress, 1870-1873, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#aniline dye#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#19th century#V&A#purple#1870#1870s#wedding#1870s wedding#1870s britain#Britain#wedding dress

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

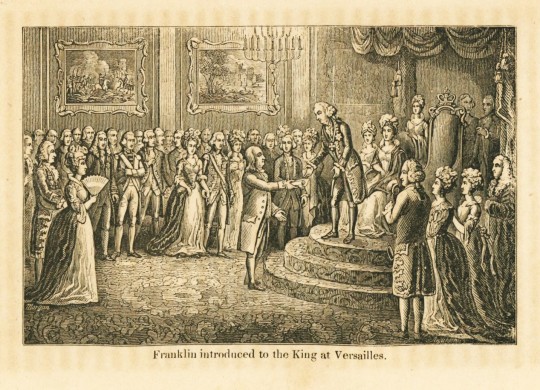

Wood Engraving Wednesday

ALEXANDER ANDERSON

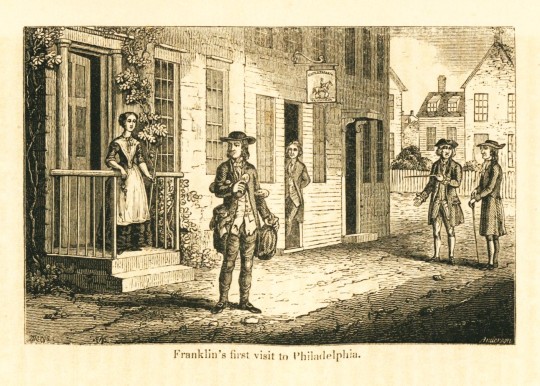

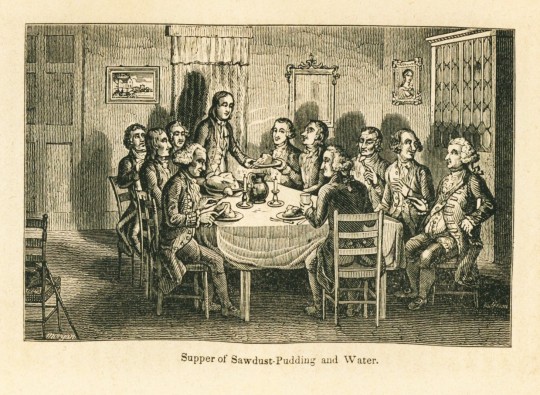

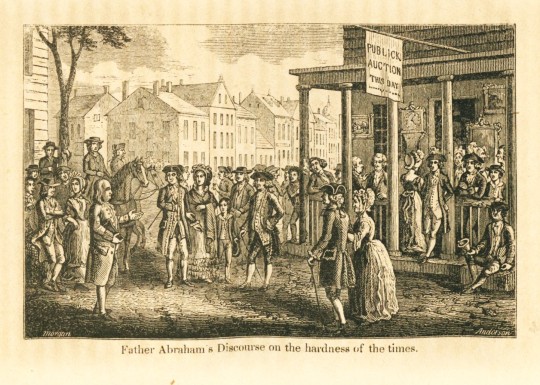

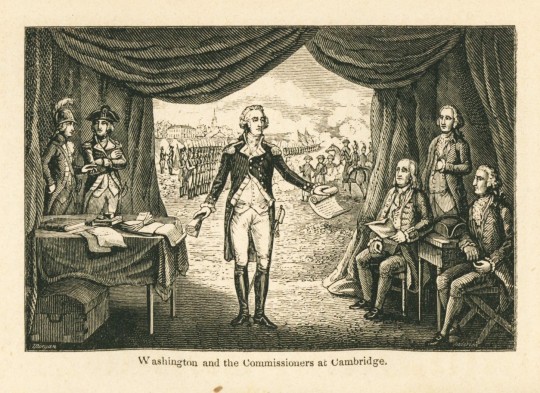

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) is well-known for popularizing the wood engraving for book illustration in Great Britain and Alexander Anderson (1775-1870) is his American counterpart as one of the earliest of American wood engravers. He trained and worked as a physician and was self-taught as an engraver. By 1820 he committed himself entirely to illustrating books with wood engravings.

Shown here are wood engravings from the 1848 biography The Life of Benjamin Franklin by O. L. Holley, published in New York by educational book publisher George F. Cooledge & Brother. The engraved title page was engraved by Anderson from an illustration by American artist Tompkins Harrison Matteson (1813-1884). The remainder of the illustrations in the book were engraved by Anderson from illustrations by Anderson's student and frequent collaborator William Penn Morgan (active 1811-1872).

View another post with illustrations by Alexander Anderson.

View more posts with wood engravings!

#Wood Engraving Wednesday#wood engravings#wood engravers#Alexander Anderson#The Life of Benjamin Franklin#George F. Cooledge & Brother#O. L. Holley#Tompkins Harrison Matteson#T. H. Matteson#William Penn Morgan#biographies#children's books

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last of the Animists: Exploring the Concept of Animism and How it Defines Nissa Revane

Prologue

Since the characterization of Nissa in the Kaladesh block is such a massive undertaking due to the density and quality of material therein, I decided at first to take a little break from my regularly scheduled programming (i.e. - having a public, frenzied, and unhinged obsession with my favorite Magic the Gathering character). However, I couldn’t stay away from the topic entirely, so here we are.

Introduction

The source of Nissa’s magic, its manifestation within Magic’s lore, and how it is represented mechanically on cards has intrigued me to no end over the years. Mechanically, I always felt that Nissa’s cards stood out more than the other two regularly-printed green planeswalkers (Garruk and Vivien). Garruk and Vivien cards often do what you would imagine a green planeswalker would do: create 3/3 green beast creature tokens, tutor creatures from your library, give overrun effects to your board, etc. The design space across these two characters’ cards always felt limited and uninspired to me. One of the things that intrigued me about Nissa, Worldwaker (read about my love for that card here) when I first encountered it in 2014 was the fact that it played around with lands rather than creatures: it animated lands into beaters, it untapped lands, it fetched lands from its owner’s library. This struck me as a unique, inspired design at the time, and it made me feel excited to use the card.

However, while yes, I have always found Nissa’s skillset a unique design for green planeswalkers – a fact that makes the desparkening all that much more disappointing to me – my primary interest in Nissa’s magic as a deranged Vorthos is how it is described in and displayed throughout the stories.

Nissa, as we are often told in post-“Nissa, Worldwaker” stories, is the last of the animists, a rare type of mage on Zendikar who can hear the voice of the world itself, but the plane of Zendikar rarely had anything nice to say; in “Nissa's Origin: Home,” Nissa’s mother, Meroe says that the soul of the land, which so often is a source of terrible nightmares for Nissa, “was never after anything other than random destruction.” Animism, we learn, is a taboo brand of magic to the Joraga (the tribe Nissa belongs to), and Numa, the Joraga chieftain, exiles Nissa because he, like many others, believes that the inherent anger of the land is due to some untold, unknown blasphemy enacted on the world by the animists. He tells Meroe, “[y]our people angered Zendikar and they paid the price. There is a reason that you are the last of the animists.” We come to understand that the reason for the plane of Zendikar’s anger is due to the Eldrazi Titans’ imprisonment on it. The world recoils in disgust at the eldritch monstrosities who eternally strive to break free of their imprisonment and consume and pervert every living thing in their way; the plane’s anger feels justified in this light, but almost no one on Zendikar understands this, not even Nissa or her mother.

So in short, animism in Magic the Gathering is the ability to connect with the soul of the world itself which allows animists like Nissa to (among other things) animate the land itself into living creatures that can fight alongside them.

However, the concept of animism has meaning beyond the lore of Magic; why did Magic’s designers label Nissa’s powers this way, and how can a real world understanding of animism help us understand Nissa in a new way?

Part I: The Animation of All Nature

Animism is a term developed all the way back in the 1870’s by British anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor as a method to describe similarities in “primitive” religions. Let’s take a quick moment to acknowledge that Tylor was a bearded white man living in colonial-era Britain using words like “primitive” to describe the religions and philosophies of people he will never meet, many of whom were currently unwilling subjects of his own government. This is an unfortunate commonality in academic studies. That aside, Tylor’s description of animism gives us our first understanding of this term. He writes in his 1871 anthropological treatise Primitive Culture that “[f]irst and foremost among the causes which transfigure into myths the facts of daily experience, is the belief in the animation of all nature, rising at its highest pitch to personification” (emphasis mine). In other, simpler words, animists personify the natural world, assigning traditionally human traits to immobile objects. The root of the current English word animate, after all, comes from the Latin animus, which means “soul, spirit, mind.” The “animation of all nature,” then, refers to the belief that what we might call objects of the natural world have their own interiority. Tylor writes elsewhere that animism is

[a]n idea of pervading life and will in nature far outside modern limits, a belief in personal souls animating even what we call inanimate bodies, a theory of transmigration of souls as well in life as after death, a sense of crowds of spiritual beings sometimes flitting through the air, but sometimes also inhabiting trees and rocks and waterfalls, and so lending their own personality to such material objects.

Humanity’s relationship to nature, then, becomes that of subject-subject rather than that of subject-object.

What does this say about Nissa, though? If you’re thinking that the above description is frighteningly similar to how Nissa views the world, you’d be right. While what Tylor argued back in the 1870’s was that animism is a crude belief system that would eventually evolve to the rise of world religions and later on the rejection of religion in rational society, Nissa’s practice of animism is very much alive and vibrant. It is hammered home often that Nissa deeply respects the personhood of objects, whether they be trees, animals, or even the ground itself. We see this very clearly in this long selection from the beginning of the Battle for Zendikar story “The Silent Cry”:

Every day there was something new, something Zendikar taught Nissa that surprised and delighted her. The land had hundreds of magnificent secrets, and it was sharing them with her.

She would never have guessed that the giant mantises secreted a scent meant to simulate the odor of fresh worms and thus attract small song birds—but not for the mantises to prey on, rather for the purpose of enjoying the birds' melodies. The songs were one of the few things capable of lulling the mantises into an easy sleep.

Nor would she have known that the vines draped between the close-growing, towering heart trees of the Vastwood Forest were more like arms than vines—arms that were holding hands. Each vine grew out of the trunks of two trees; it did not belong to one tree more than the other, it was shared equally between them, a tether that bound the trees. The vines connected one heart tree with its chosen companion, and allowed the two to share memories, feelings, and dreams.

These trees were linked forever; they mated for life.

And the gnarlids, the silly, beastly, sneaky gnarlids; they had a ritual that they managed to keep hidden from most everyone else on Zendikar. On the darkest nights, when there was no moon but the skies were clear, the gnarlids scaled the tallest trees, poking their heads above the canopies, and they laughed at the stars. Little breathy snickers that to anyone else listening sounded like nothing more than the leaves of the highest branches rustling in the wind. It was an inside joke meant only for them.

Equally as impressive was the tribe of humans who lived in the lowest canopy of the Vastwood's trees—not in a central encampment, but spread out through the expanse of the forest. Five or six humans shared each treehouse hamlet, and there were over a dozen hamlets. The tribe was able to stay well informed of each other's movements and needs thanks to their ancestors, who had closely studied the language of the chatter sloths. The people sent messages to each other by speaking to the nearest chatter sloth. It was only a matter of minutes before the sloth would relate the gossip to its neighbors, who would pass it along through the network of tree dwellers. Soon all humans in the tribe would know of the hamlet's news thanks to the little gossipmongers.

It’s important here that Nissa shares equal amazement with the goings on of plants and animals as she does with the ingenuity of her fellow sentient mortals; to her, they are no different. To Nissa, the “animation of all nature” is not some crude, outdated philosophy that has been surpassed by rationality. It is her everyday reality.

Of course, however, Magic the Gathering is a game of wizards battling each other, and its worlds and characters are full of wonder and, well, magic. The “animation of all nature” has another meaning to Nissa in that she can call out to the interior soul of immobile objects and, in a non-metaphorical way, personify them … as in, she can “animate” objects into living, walking, thinking, fighting creatures with a will of their own. In the first story of the Zendikar Rising arc, “In the Heart of the Skyclave,” Nissa and Nahiri, looking for a specific object of interest, are at a loss at which place to begin hunting for it in a giant, city-sized airborne dungeon when Nissa spots a lone fern:

Nissa crouched down to one of the ferns. Its leaves were as large as she was, but its flowers were tiny, delicate, and blue.

"How is it possible for plants to thrive here?" Nahiri asked, coming up behind her.

Nissa smiled. "You'd be surprised at how many things thrive in unlikely places on this plane."

"How—"

Nahiri began to speak again, but Nissa tuned her out. She rested a hand on the top of the fern, like a parent's hand on the head of a child. She closed her eyes and felt its life under her fingers, felt its struggle and its pride in surviving in such a foreboding place. Nissa smiled at that strength and that pride. And she called it forth.

She heard Nahiri give a gasp as the elemental emerged into existence. It was a tall thing, twice her height, green and vibrant as its life force, its head a mass of fronds with small chains of blue flowers entwining its arms and neck.

The dual meaning of the “animation of all nature” is on display here. Nissa very clearly acknowledges the personhood of the fern, using terms usually reserved for descriptions of the lives of people like struggle and pride, and at the same time she animates the stationary fern into a creature, a person with a will of its own and strength to match. In the end, many elements of the Zendikar Rising arc were lacking, but I always found this particular scene to be a wonderful marriage of the best parts of Magic story: great character moments tied together with a childlike wonder at the beauty and power of magic.

Part II: Infinite Possibilities

Anthropology, however, has moved far beyond its Victorian, colonialist roots. On the same note, Nissa has grown and expanded far beyond the borders of what she previously was.

In 2006, anthropologist Tim Ingold published an essay titled Rethinking the Animate, Re-Animating Thought that reevaluates the concept of animism (there are, of course, many evolutionary steps between the philosophies of 1871 and those of 2006, but for the purposes of this piece, suffice it to say that things have changed). Ingold’s primary thesis is that animism should be considered less of a primitive branch of religious thought and more of an ontological philosophy, an experience of being present in the world. In his research, Ingold provides this anecdote:

One man from among the Wemindji Cree, native hunters of northern Canada, offered the following meaning to the ethnographer Colin Scott. Life, he said, is ‘continuous birth.’ I want to nail that to my door! It goes to the heart of the matter. To elaborate: life in the animic ontology is not an emanation but a generation of being, in a world that is not pre-ordained but incipient, forever on the verge of the actual. One is continually present as witness to that moment, always moving like the crest of a wave, at which the world is about to disclose itself for what it is.

This is a lot to unpack, but let’s use this to point out the similarities and differences between the previous 1871 understanding of animism. Like Tylor’s initial exploration of the concept, Ingold’s animists still treat the world around them with same respect and reverence; they still, in other words, still interact with the world with a subject-subject relationship instead of a more rational subject-object relationship. However, instead of fixating on the spiritual aspects of animism (i.e. - the inherent soul of inanimate objects), this modern take is more of a state of being, a practice of actively engaging with the world around you.

Ingold, in other places, argues that, while yes, animism intentionally blurs the line between what is considered ‘alive’ and what is not, the true cornerstone of an animist ontology is the process of change:

Wherever there is life there is movement … The movement of life is specifically of becoming rather than being, of renewal along a path rather than displacement in space. Every creature, as it ‘issues forth’ and trails behind, moves in its characteristic way. The sun is alive because of the way it moves through the firmament, but so too are the trees because of the particular ways their boughs sway or their leaves flutter in the wind, and because of the sounds they make in doing so.

An animist, then, in this ontology is in a responsive, conversational relationship with the world around them. They wouldn’t fixate, for example, on the personhood of a tree, but they would know how to have a positive, symbiotic relationship with the tree.

What does this new way of looking at animism have to do with Nissa Revane, though? It seemed like Tylor’s outdated definition of animism already had both Nissa’s worldview and the manifestation of her magic pegged down. What could be added? Well, like the definition of animism, like this “world that is not pre-ordained but incipient, forever on the verge of the actual,” Nissa herself has changed drastically in recent years.

If I had the time and bandwidth, I might set out to argue that, of all Magic’s heroes in the last decade, Nissa has gone through the most character growth of any of them; she has shifted through the most colors and she has gone through the most development of any other planeswalker. However, for the purposes of this piece, I’m going to focus on the most recent story (to date) that Nissa has appeared in: Grace P. Fong’s “She Who Breaks the World.” Now, I’ve made it no secret that this is my favorite piece of Magic fiction since the Ixalan days, so I’m certainly biased here, but the narrative meat in this text is rich and vibrant.

When we pick back up with Nissa in “She Who Breaks the World,” we find her at likely the lowest point we have ever seen her at. Her agonies are manyfold at this point. To start, she is still reeling from the unbearable trauma of what the Phyrexians did to her. She had set out with a strike team of her planeswalker allies to stop the Phyrexian invasion of the multiverse, but upon their failure, Nissa, along with many of the others, were captured. Her mind was chemically altered against her will to be utterly, completely submissive to the will of Elesh Norn (the Phyrexian leader, if this essay somehow reaches beyond the MTG sphere). Similarly, her body (again, against her will) was then chemically and mechanically altered to be more in line with the Phyrexian understanding of perfection. Then, Norn used Nissa’s body, mind, and animist powers to launch an invasion of the entire multiverse; Nissa ended up being instrumental in this process because it was her animist abilities that allowed Norn to directly control the Invasion Tree.

Nissa was eventually freed from the Phyrexians’ control in the aftermath of the war, her mind given back to her, and as much of the grafted metal removed from her body as could safely be removed. However, no level of healing could “cleanse the memories of what she had done” while her mind was under the domination of Phyrexia. She understandably has trouble forgiving herself for what she did, whether she had agency in the act or not.

Secondly, if that wasn’t bad enough, after she woke up with her mind intact, she discovered that she had lost her planeswalker spark. While she is not alone in this (all of the other planeswalkers currently on Zhalfir aside from Chandra lost theirs as well), it hits Nissa particularly hard because, for one Nissa has always had a deep connection to her home world of Zendikar, and secondly, Zhalfir is full of people she tried to ruthlessly kill while under the influence of Phyrexia. She cut down in cold blood dozens, if not hundreds, of these survivors’ friends and family. While the surviving Mirrans and Zhalfrins understand that she did not have control of herself during this time and forgave her, Nissa does not feel incredibly comfortable living around people she so directly harmed. She is restlessly homesick with no feasible way to get home and stuck with people she doesn’t feel worthy enough to be around. Furthermore, Nissa’s planeswalker powers are integral to the identity she has created for herself. This sense of self is just one more thing she has lost.

And lastly, there is the issue with Chandra. While they were technically a romantic couple after they kissed at the end of the previous March of the Machines story, “The Rhythms of Life,” things are still far from well between them. Apart from the tremendous guilt and shame Nissa feels from what she did to Chandra during the Phyrexian story arc (Nissa almost killed Chandra multiple times, one time even impaling her), both of them are still dealing with the fallout of their breakup as described in War of the Spark: Forsaken (even typing the name of that book makes me feel ill). Nissa wonders if Chandra can ever love her the way she needs and if that is even a reasonable thing to ask of her after all the two of them have recently gone through.

While this was a long, drawn-out summary, I think it was necessary to show what Nissa is going through on the cusp of her metamorphosis. The depression she is feeling along with what could probably be described as PTSD has left her stuck in the past. She laments the fact that she no longer hears the voice of nature. The leyline songs are completely silent, and when she calls out to the soul she knows dwells in all the objects in the world around her, nothing answers. She assumes this is punishment for what the Phyrexians made her do.

She’s wrong, however. Nissa and Chandra finally have a moment of understanding between the two of them, and as a part of this intimate moment, Nissa finally admits that her animist power no longer work; when Chandra expresses surprise at this, Nissa responds,

"They won't listen to me. I tried. Many times. But when I call out to them, it's like my voice isn't my own. Like it belongs to Phyrexia instead, like everything I've ever connected to is drowning me out."

For once, Chandra pauses. "You know," she concludes. "You have good connections, too."

"What do you mean?"

"It's true—you did bad things while they had you. But everyone you've connected with over the years with the Gatewatch, we're just happy you're still here. With us." Chandra sets fire to a chunk of moist dirt that was about to fall on Nissa, turning it into a soft rain of ash. "With me."

For the first time since she awoke in Zhalfir, Nissa smiles. Chandra, sweet Chandra, even if she doesn't realize it, has always understood and explained emotions better than Nissa ever could.

Chandra continues, "Your connections aren't drowning your voice, Nissa. They're changing it into something new, maybe something even more powerful. Infinite voices, infinite possibilities, right?"

Infinite possibilities. Nissa offers her hand to Chandra. "All right, let's try."

Gripping Chandra's fingers in hers, Nissa closes her eyes. She retreats inward and listens for her inner voice. It's hard, much harder than before, but Chandra is dutifully helping her concentrate, blasting the falling rock away before it can reach her.

Nissa is greeted by ringing deep in her ears, but she refuses to be deterred. With her connections in mind, she picks the static apart into unique melodies, the individual songs she picked up from all around the Multiverse. She arranges them, harmonizes them, and this time, when she calls to Zhalfir, her voice is amplified in chorus. She offers an apology.

The plane answers. It too was cut off from everything it knew, from the connections it had made. It, too, was scarred by Phyrexia and is growing into something new. It forgives her, and Nissa can finally forgive herself.

Magic floods her flesh, her blood, her bone. She hears Chandra laugh, delighted by their success.

I could literally talk forever about this scene, how it is also a marriage of everything I love about Magic Story, but let’s zero in on how Nissa’s change in perspective is similar to how animism has changed meanings over the past one-hundred and fifty years.

In the same way that Tylor was fixated on how “primitive” he felt animism was, how it was just a cultural stepping stone on the way to enlightenment, Nissa remained fixated on her animist powers. To her, the voices of the natural world were oftentimes more real to her than the voices of her friends. The songs of the leylines, the elementals she could animate with a whisper, the power she wielded in defense of the worldsoul … To Nissa, these were all in all.

However, what Nissa learns from Chandra in the climax of “She Who Breaks the World'' is to accept that life is exactly what Ingold calls a “continuous birth.” Nissa embraces this conversational relationship with the world around her, and nature is no longer all in all to her. Hand in hand with Chandra, Nissa now lives “in a world that is not pre-ordained but incipient, forever on the verge of the actual,” as Ingold puts it, and a world of “infinite possibilities,” as Fong puts it.

As the definition of real-world animism has shifted over the years, so too has Nissa’s magical animism. She used to obsess over her connection with nature with religious fervor, and even though Nissa worshiped no gods, her devotion to the soul of the world around her was stronger than many devout worshippers on Theros. However, in “She Who Breaks the World,” Nissa learns to recognize that she, and the rest of the world around her, is alive because she moves in her own “characteristic way.”

Epilogue

While I have certainly been burned by WotC’s treatment of Nissa in the past, I am cautiously excited for the stories that can now be told about her. Nissa is currently set up to grow and expand in interesting ways, and I hope (beyond hope) that future Magic stories starring Nissa will continue on the path that Fong set her on.

Nissa may be the last of the animists, but that doesn’t mean she can’t be the first of something else. I’m excited to see what that “something else” will be.

Bibliography

Every source quoted in this essay is linked directly before the quote in question. I was too lazy to create a reference page today. Sorry! 😬

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

December, Edward Poynter, 1870

#all of the designs from this series depicting the 12 months were turned into tiles and can be found in the poynter room at the v&a :)#december#winter#Edward Poynter#1870s#victorian#19th century#watercolor#Aestheticism#england#britain#europe#v&a

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

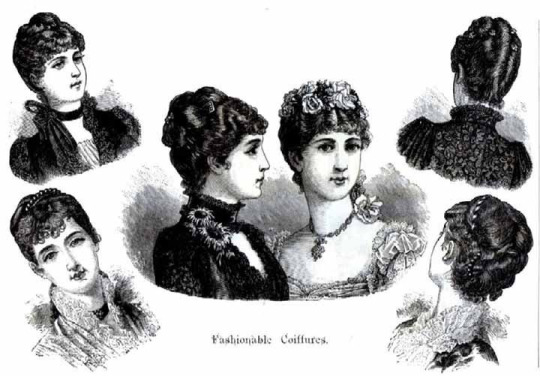

figure 1

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902) • The Ball • 1878

Figure 1: According to French fashionistas, Tissot got the hat all wrong. Apparently hats were inappropriate as evening wear, particularly at a ball. Indeed, when perusing fashion plates of the late 1870s, formal evening attire never included hats.

For formal evening events, hair was styled in elaborate braids, buns, and curls, often adorned with silk flower sprays and fancy clips and combs. Silk flowers were also sometimes used as embellishments for dresses.

A Tissot creation likely inspired by the fashion plates of the day, the evening or ball dress in figure 1 features a bow right at the buttocks followed by a cascade of layered pleats, lace, and ruffles. This style was commonly referred to as The Princess Line dress. Created in Great Britain by Charles Frederick Worth in the form of Princess Alexandra's wedding dress, it soon took off as the latest dress style craze.

French hand fan • Ivory, paper, gouache, mother-of-pearl, metal • 1860-70 • Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Figure 2

Figure 1: In the mid 1870s, the bustle evolved into a less protruding fashion feature and eventually, toward the end of the decade gave way to the mid-bustle or natural form era. This transformation took place from 1877 through approximately 1882. Compared to the large, overstuffed bustles of the early 1870s, the Mid-Bustle, or Natural Form dress created a more vertical, slimming silhouette. The waist was undefined and embellishments began at the back of the waist, or even below it.

Figure 2: It is difficult for a fashion history novice like me to define the correct occasion for this particular dress. It's perhaps a special occasion day or afternoon dress and hence less embellished. Or perhaps the modest satin bow at the hip gives it away as just a regular day dress. In one entry at Lily Absinthe's blog, she states that a semi-train is usually indicative of a day or afternoon special occasion dress. All I know for sure is that I adore the lovely vertical pleated train!

Princess Line dress • 1878-1880 (made) • Unknown designer and maker, likely from Great Britain • Virginia and Albert Museum

Blue and gold Jacquard-woven silk made with a fitted bodice and narrow skirt drawn back into drapes at the back, and rusched silk trim. It has elbow-length sleeves and a square neckline, which are both trimmed with machine-lace. This is a day or afternoon dress, likely worn at home. More views of this dress can be seen here.

Attire appropriate for a hat.

Of course, the ultra-slim silhouette of the princess dress was restrictive and necessitated increasingly tighter undergarments like corsets and girdles, further restricting movement. Poor working women who engaged in hours of manual labor could not afford either the latest fashions nor the restricted movement.

Sources:

Lily Absinthe

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute , New York City

Fashion History Timeline (FIT, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York City

V & A (Victoria & Albert Museum, London

#fashion history#late 1870s fashion history#princess line dress#james tissot#art history#french fashion history#late 1870s fashion plate#french hand fan#victorian fashion#historical fashion#victorian era#19th century fashion#the resplendent outfit blog#french fashion#historical painting

36 notes

·

View notes