#uncle tom’s cabin

Text

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” was published #OnThisDay in 1852.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Harriet Beecher Stowe

This is 1 of 12 vintage paperback classics that comprise our current giveaw@y.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nothing of tragedy can be written, can be spoken, can be conceived, that equals the frightful reality of scenes daily and hourly acting on our shores, beneath the shadow of American law."

-Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin

#harriet Beecher Stowe#uncle tom’s cabin#quote#book quote#American law inequality#inequality#fuck I don’t know how to tag this but it’s so good

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

FnA Records Announce 'Song & Dance Man: A Tribute to Warrant & Jani Lane'

‘Song & Dance Man: A Tribute to Warrant & Jani Lane‘ – featuring 19 tracks including 3 Tracks from Jani Lane’s Daughter and 1 track featuring Jani’s Brother is being released via FnA Records.

FnA Records is excited to be releasing a Tribute album, ‘Song & Dance Man: A Tribute to Warrant & Jani Lane‘, to one of their favorite bands and songwriters. This project was seven months in the making and…

View On WordPress

#Cherry Pie#Eric Oswald#FnA Records#Hunter Skeens & The Forerunners#Jani Lane#John Feist#Maddi Lane#Song & Dance Man: A Tribute to Warrant & Jani Lane#Uncle Tom’s Cabin#Warrant

1 note

·

View note

Text

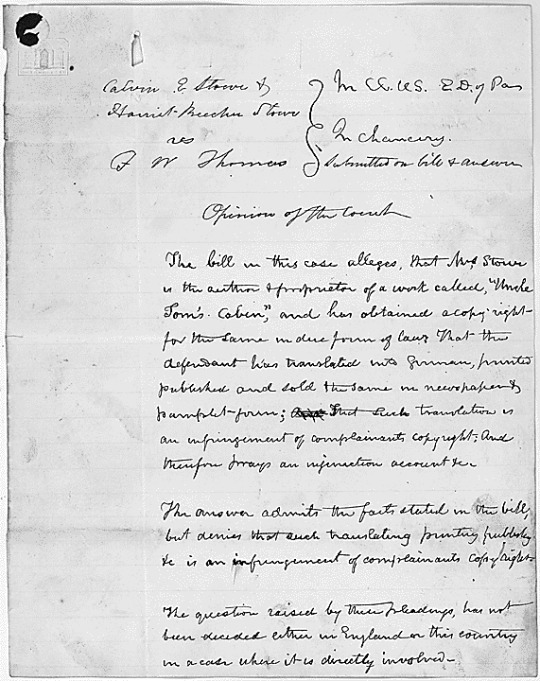

Opinion of the Court in Stowe v. Thomas

Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United StatesSeries: Equity Case FilesFile Unit: Stowe v. Thomas, Case #9 October Session 1852

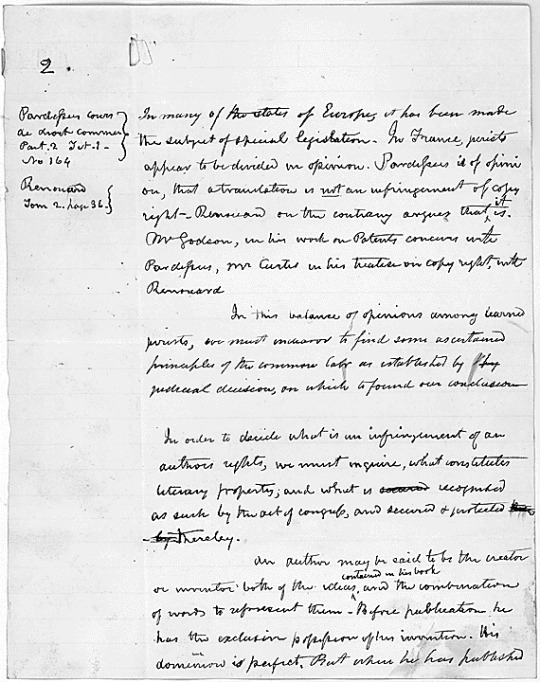

Calvin E Stowe & [bracket] In CC. US. E.D. of Penn Harriet Beecher-Stowe vs In chancery F W Thomas [end bracket] Submitted on bill & answer Opinion of the Court The bill in this case alleges that Mrs Stowe is the author & proprietor of a work called, "Uncle Tom's Cabin," and has obtained a copyright for the same in due form of law; that the defendant has translated into German, printed published and sold the same in newspaper & pamphlet form; [struck through] That such translation is an infringement of complainants copyright; And therefore prays an injunction account &c. The answer admits the facts stated in the bill, but denies that such translating printing publishing &c is an infringement of complainants copyright. The question raised by these pleadings, has not been decided either in England or this country in a case where it is directly involved2. Pardessus cours [bracket] In many of the states of Europe, it has been made the de droit commer subject of special legislation. In France, jurists appear Part. 2 [T?]. 1 to be divided in opinion. Pardessus is of opinion, that No 164 [end bracket] a translation is not an infringement of copyright, Renouard on the contrary argues that ^it^ is. Mr. Godson, in his work Renouard [bracket] on Patents concurs unto Pardessus, Mr Curtis in his Tom 2. Page 36. [end bracket] treatise on copyright unto Renouard In this balance of opinions among learned jurists, we must endeavor to find some ascertained principles of the common law as established by [struck through] judicial decision, on which to found our conclusion In order to decide what is an infringement of an authors rights, we must inquire, what constitutes literary property; and what is [struck through] recognized as such by the act of congress, and secured & protected [struck through] thereby. An author may be said to be the creator or inventor both of the ideas ^contained in his book^ and the combination of words to represent them. Before publication he has the exclusive possession of his invention. His dominion is perfect. [full transcription at link]

#archivesgov#December 24#1853#19th#harriet beecher stowe#stowe v. thomas#copyright#uncle tom's cabin

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I finished reading Uncle Tom's Cabin. A few thoughts below (some spoilers, of course).

Both the story and the dialogues are gripping in a number of areas but sometimes the tension fails to pay off and things work out a little too perfectly. While certainly a social justice tale (I hadn't realized how very explicit the author would constantly expound upon her moral motive for telling the story), it ultimately has a sort of feel-good quality, where most people are fundamentally good and things generally come out all right in the end, which seems not to be the accepted norm in today's fiction media wherever it has overt social justices messages (e.g. Orange Is the New Black). My biggest complaint about the plot was really a matter of timing: I disliked being kept hanging about George and Eliza's escape for nearly two hundred pages of focusing on Uncle Tom, only to get one more chapter thrown in wrapping up their escape arc much too neatly (there was more potential there, especially in the development of one of their pursuers who wound up staying with them to recover from bullet wounds). The timing of that arc with the main arc doesn't seem to match properly: a year has passed in Uncle Tom's life before we return to George and Eliza, who are still in the midst of their escape to Canada which seems to have only gone on for several more weeks.

(Interesting random observation: the author wasn't afraid to give different major characters the same first name. There is another character named Tom besides Uncle Tom, namely the aforementioned pursuer who got shot, and there are two Georges who each play a fairly significant role. This adds some verisimilitude to the story, but as far as I can tell, it's rare in fiction even if not rare in real life, and I can't think of many other examples of it outside of longer book series with much vaster arrays of characters such as Harry Potter and A Song of Fire and Ice, and even there it's never between two fairly prominent characters.)

The entire focus of the stories revolves around the current nature of slavery, and the author preaches her anti-slavery message very explicitly to the reader (dripping with explicit Christianity and often breaking the fourth wall in doing so). This was done powerfully enough to resonate well with me even though I grew up in a time when a universal message that slavery is evil was instilled in me from a young age so that this feels like "old news"; Stowe brought her contemporary knowledge of what slavery looks like to life in a vivid way that enriched my conception of the depths of its horrors. At the same time, I found it interesting that it felt like 80-90% of her anti-slavery message focused on the separation of families rather than other aspects of slavery.

Harriet Beecher Stowe clearly had a profound belief in the humanity of people of all races but also showed signs of racism popping up from time to time in talking directly to the reader and characterizes people of African descent as having a simpler, less refined, and less industrious nature, in ways that sometimes (though not always) imply that these differences are innate rather than a product of interracial history. Apparently the book has been criticized for indulging in a number of black stereotypes through several of the black characters. While the development of these stereotypes is unfortunate, I'm not sure we can fairly blame her for helping them to solidify, as it seems she was genuinely trying to base her characters off of amalgams of enslaved people that she had come in contact with.

What was gripping me the most while reading the last quarter or so of the novel was the view of the meaning of Christianity that it suggested to me, and I surprised myself, as someone who's never felt like much of a friend to Christianity, at how I was responding. Having finished the book, now I would say that it makes the most effective moral case for Christianity that I've ever encountered anywhere; certainly it does a better job of making Christian faith attractive than anything I've read by C. S. Lewis. Not that it ever bothers to argue any of the concrete claims of Christianity, mind you, not even the existence or nature of God. Rather, I'm saying it reaches me in some part of my gut which somehow gets the intuition behind why we should stand unyielding with our moral convictions because a higher power above affirms them, and that God or Righteousness or whatever you want to call it being on our side means infinitely more than whatever we'll suffer at the hands of less enlightened humans around us by refusing to budge an inch. (It's strange that I'm even typing these words on this website, where I'm usually better known for talking in a very different and much more pragmatic way about ethically contentious issues.) Stowe's religious convictions, as channeled through her character Uncle Tom, highlight what I've always called my favorite feature of Christianity: the exhortation to turn the other cheek and to love the sinner while hating the sin. It's hard for me to see Uncle Tom as anything other than a hero for resisting internal corruption even in the face of horrific oppression, refusing to be "broken in" by whipping one of his fellow slaves, and being willing to die for what he believes in rather than become a cog in the machine that he abhors. (It's very much like the climax of the original Star Wars trilogy, and there are notes of these ideas in other modern popular fantasy series, of course.) It's a shame that Uncle Tom has become known as an epithet referring to something related but quite distinct, which grew not directly from the Uncle Tom in this novel but from the evolution of the character through various stage adaptations afterwards that Stowe had nothing to do with.

As a final note, it may seem strange that I'm applauding the "turn the other cheek" idea as exemplified by Stowe's character and yet wrote this post expressing horror at the passive "be good to your master" acceptance that Jupiter Hammon preached to his fellow slaves in the 1780's. I think my main crucial issue with the Hammon speech is not that it advised remaining passive and placating one's oppressors (which, I might be inclined to agree with Hammon, however reluctantly, was probably the safest way to minimize harm in most individual's cases when escape really wasn't an option), but rather that it argued that slavery existed for the time being because it was God's will and it should be accepted for now as God's will (regardless of the fact that Hammon hoped to see the institution end, when God should will it). That message was clearly a recipe for inaction, as in reality as well as even in many theistic models of the world, things aren't just going to change on their own because of God's will without humans taking deliberate action to change them.

Neither Stowe nor her Uncle Tom character followed Hammon's idea that slavery should just be accepted for now, even if Tom (just like Hammon) at one point early on claimed not to care for his own emancipation and only hoped to see his younger fellows emancipated (although in fact Tom is later overjoyed when his master St. Claire promises to free him). Rather, Uncle Tom sees slavery for what it is, objectively a great evil, and simply believes that evil can only be fought with pacifistic good and a refusal to abandon one's deepest principles. He encourages others' escapes even though he doesn't attempt to escape himself; at the same time he is not all right with other enslaved and oppressed people violently attacking their oppressors or not seeing their oppressors' humanity. I'll acknowledge that this ultra-pacifistic approach isn't the whole story of how to resist oppression and that sometimes there is a time and place for violent aggression against one's oppressors. But still I see a lot of beauty in the approach Uncle Tom stood for, and as a character he did not deserve to be reduced to the derogatory trope that later became the popular notion of "an Uncle Tom".

#uncle tom's cabin#orange is the new black#social justice#game of thrones#slavery#racism#stereotypes#christianity#star wars#c s lewis

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jim Caviezel: We're hoping this movie will be the Uncle Tom's Cabin to end modern slavery.

Me: Did he say Uncle Tom's Cabin?

[History Trivia Mode Activating]

(I was very sane. I did not info-dump all the historical trivia about the build-up to the Civil War, and that one Rose Greenhow tantrum, on my poor unsuspecting brother. Doesn't mean I didn't want to.)

#history is awesome#sound of freedom#the one thing i did mention was that it can't really be uncle tom's cabin#because pretty much the entire audience already believes that sex slavery is bad

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

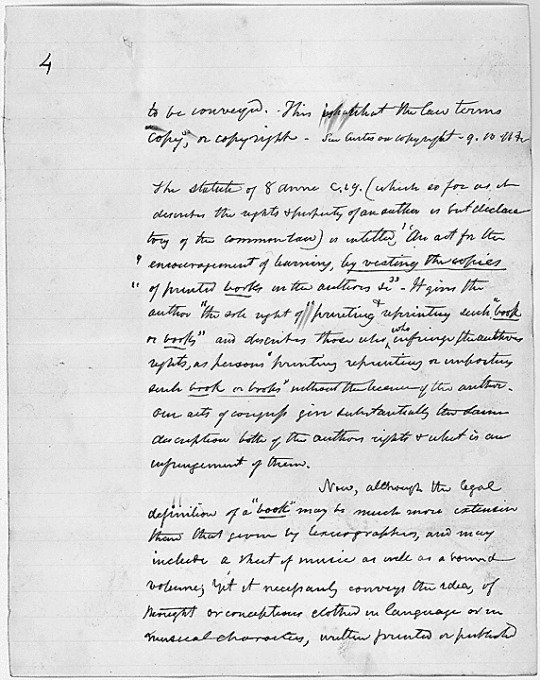

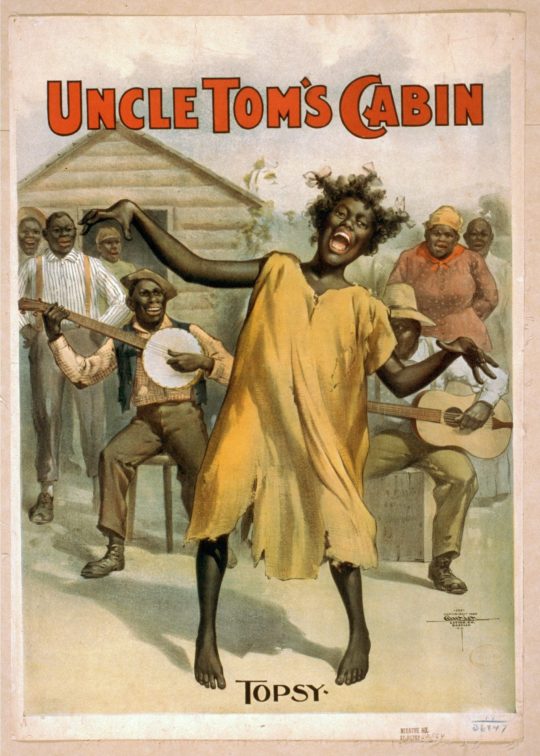

“Nothing is scarier than real American history – minstrel shows and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” - Misha Green ; Lovecraft Country Showrunner

"There is a history of white folks donning some abomination of blackness" - Little Marvin ; Them Creator & Executive Producer

#lovecraft country#them#da tap dance man#topsy x bopsy#blackface#minstrelsy#uncle tom's cabin#history#horror#series#american history#2020s series#quotes#misha green#little marvin#racist caricatures#pickaninny#racism as horror fuel is the greatest idea

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

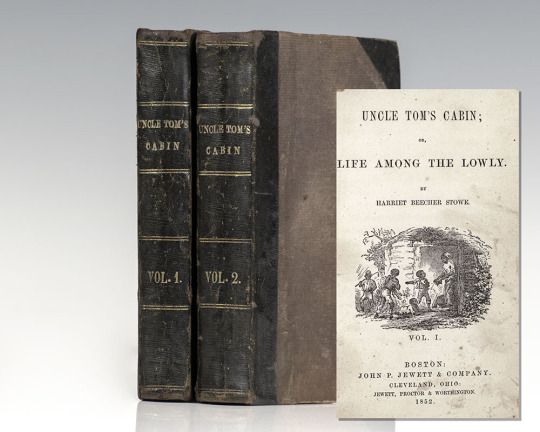

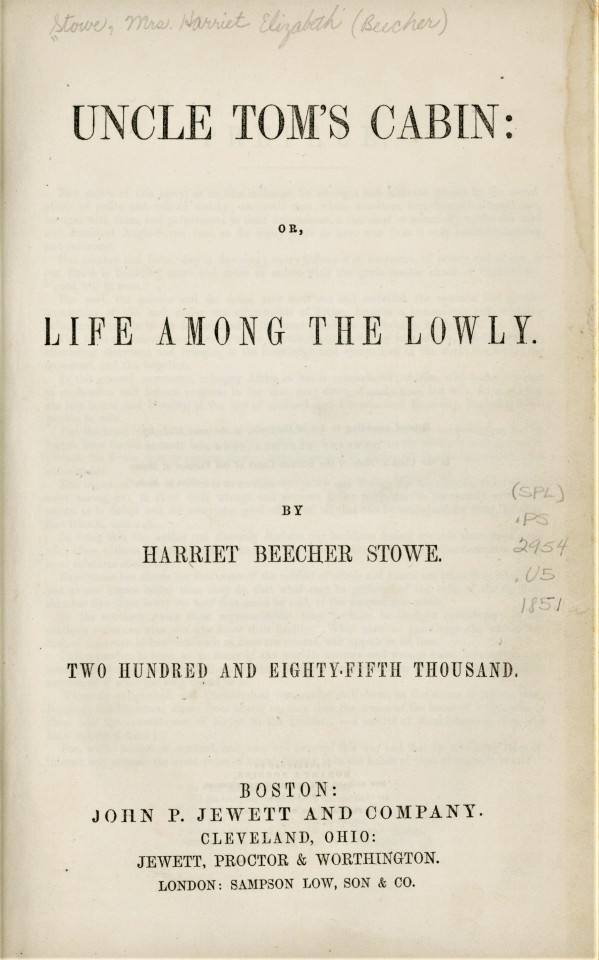

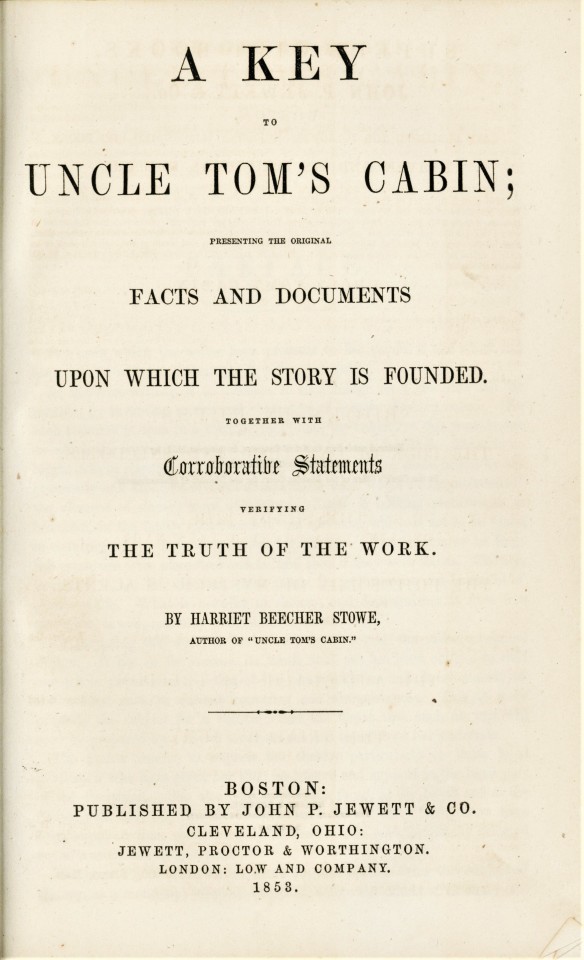

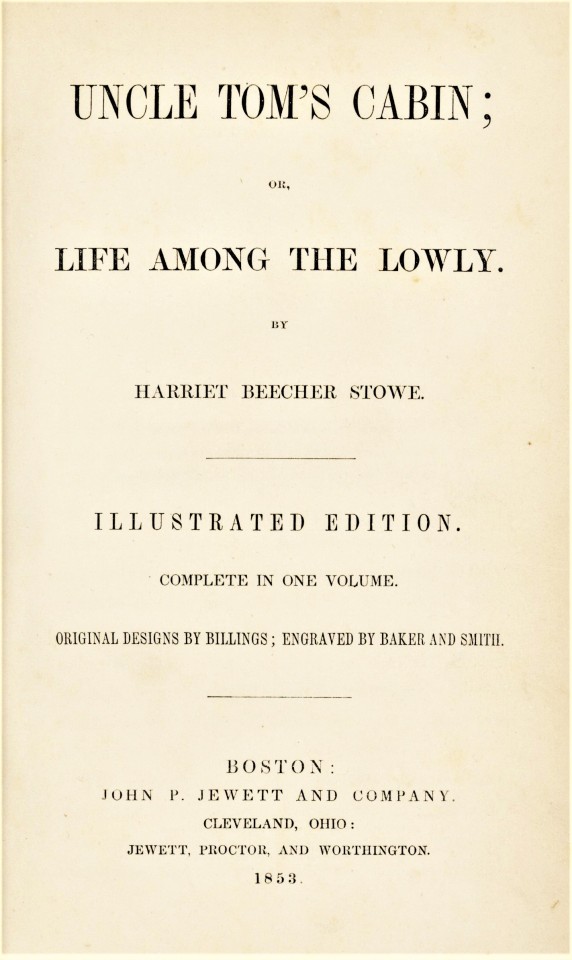

Milestone Monday

On this day, May 20 in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin was published in Boston by John P. Jewett. Its popularity was so great that the first edition went through many printings and sold 300,000 by the end of the year in the U.S. alone (1.5 million were sold in Britain in the first year). Jewett had presses in operation 24 hours a day to keep up with demand.

Our copy is one of the later printings for that year, the 285th thousand, and was published in one volume without the six full-page illustrations by Hammatt Billings engraved for the first printing. In late 1851, Jewett, along with partners Proctor and Worthington, formed a second publishing business in Cleveland, which took on the responsibility of selling Uncle Tom's Cabin in the west, which is reflected on the title page of our printing. Our particular printing was also issued later and bound with the 1853 A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin.

We also hold the first illustrated edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published by Jewett in 1853 with many illustrations by Billings engraved by Baker and Smith, and we show some of those illustrations here as well.

View more Milestone Monday posts.

#Milestone Monday#milestones#Harriet Beecher Stowe#Uncle Tom's Cabin#John P. Jewett#Hammatt Billings#A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin#illustrated edition#Baker and Smith#publishing history

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was published #OnThisDay in 1852.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Augustine & Alfred

It's probably been obvious to anyone else, but I only now realised that Alfred and Augustine are named after the two brothers in Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Also, what the fuck John, that seems a little bit mean spirited. Augustine is one of your best friends and you re-named him after a slave owner.

I am also not sure if it fits?

For Augustine, okay, maybe it does. He seems pretty detached and blasé about a lot of stuff, and uses irony as his shield and to hide his true feelings. And, like his book counterpart, the moment he realises that in order to not be evil in the face of evil, one has to take direct action against evil, he dies (although getting stabbed is much more mundane than getting literally sucked into hell).

But Alfred? He seems like a pretty okay dude, gave his own life to stop people from fighting each other, a bit easily led, maybe. That seems pretty different than the oppressive, brutal classist/racist he is in the book. My only guess is that John heard "banker" and categorized him as a total asshole. Although with how much of an unrealiable narrator John is, Alfred could have just, literally, worked at a bank.

#tlt#the locked tomb#gideon the ninth#harrow the ninth#john gaius#augustine the first#alfred quinque#jod#the saint of patience#patience does not seem like a virtue of uncle toms cabin alfred...

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay i started reading iola leroy and it's the first time in the two decades since i've read uncle tom's cabin where i'm actually like "i need to reread it" because iola leroy truly feels like an answer to it? i'm very early into it still of course but it reads like an abolitionist pamphlet (which is what uncle tom's cabin is), except slightly truer to life? i've only briefly met them but both iola and her mother marie very much follow the regular archetypes for "good" women in european literature: they're beautiful, well-read, gracious and noble, more of a goal than reality (like cosette or kitty).

then the decision to focus on light-skinned/passing black women is interesting. i think it's supposed to appeal to the sentimentality of the white readers (like a good pamphlet does). like these women are so good, so nice, so close to being just like you wish to be, and yet due to arbitrary rules they're thrown into abject cruelty (i'm not there yet but it seems like this is where it's working up to). and this is what i remember the best about uncle tom's cabin as well, how noble tom was and how unjust his situation was.

#like. all of the black characters are very Good which i think is ultimately about justifying their personhood to white readers#anyways. gotta reread uncle tom's cabin if i want to make a better argument ig#on the brain#books

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish I could remember where I once read the suggestion that Hugo’s characterization of Jean Valjean might have been influenced by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s characterization of Uncle Tom.

It’s been a long time since I read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but from what I remember of it, and if Hugo really did read it, then I wouldn’t be surprised if that claim was true. I wish Stowe’s book hadn’t been hijacked by racist stage adaptations that gave the phrase “Uncle Tom” its current meaning. Then the character of Tom could be remembered as the Jean Valjean-like figure she meant him to be: a quietly strong, pious man who lives a life full of hardship and social injustice, but who resists the temptations of bitterness and hate, and instead constantly helps, protects, and sacrifices for others.

(I’m not saying there’s nothing problematic about Tom – he was written by a white woman pre-Civil War, and he probably is more of a Christlike paragon than a three-dimensional human being – but he’s not a subservient stereotype!)

At any rate, if that suggestion is true, then all the more reason for a modern Les Mis adaptation to cast a black man in the role of Valjean!

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Uncle Tom's cabin, or Slave Life in America by Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1853.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the temperatures drop and night falls earlier each evening, staying inside to read is a constant temptation! What work of #classicliterature featuring snowy nights or icy storms are you eying on your TBR this month?

#classic literature#literature#winter reads#winter reading#Frankenstein#Ethan Frome#Anton Chekhov#Anna Karenina#Uncle Tom's Cabin#In Our Time#currently reading#TBR#december TBR#book#books#booklr#studyblr#norton critical editions#norton editions

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cabin lift, now disused, one of Blackpool's architectural wonders. Tourists say, "I wonder what that's there for".

2 notes

·

View notes