Text

So here's a question: what does it mean to say that so-and-so is a wonderful person when sober, but that alcohol makes them a monster?

(This question is inspired by having just finished the Netflix series Maid, where it's basically the crux of the Sean character. Soon I might be posting a review of Maid, which I found engaging but deeply flawed in the character-writing.)

Speaking as someone who at one point in my life knew tons of people both in sober states and drunk states, I've come to a pretty clear conclusion since long ago that not only is one's drunk self not a separately compartmentalized person from one's sober self, but actually what comes out of someone when they're drunk (and thus less inhibited) is if anything a truer reflection of the kind of person they really are. Lovely people I've known become lovelier when drunk; douchey people I've known become downright a-holes when drunk. I know I'm no more capable of doing something horrible to someone when drunk than when sober. I guess I can't think of anyone I've known who seems genuinely lovely when sober but horrible when drunk (the closest I've seen is that some people's tempers are shorter when drunk, which I consider a different phenomenon), but I think if I did encounter someone like that in my life, I'd be able to connect their drunk behavior and personality with at least something subtly detectable in them when they're sober, just hidden under layers of conscious beliefs and care.

I've assumed that this is true of most other milder substances (there are some, which are highly addictive and euphoria-inducing, that make people into utility monsters and thus might turn a good person into an effectively evil one, but that's a different thing).

Now it's occurring to me I could be wrong. Maybe there are certain substances for certain people that act as a magical chemical trigger in the brain to drastically change whatever governs their fundamental morality. Maybe there's a particular combination of chemicals specially attuned to turning Liskantope into a terrible person while he's affected by them, and it just doesn't happen to be alcohol. But for some people, that chemical could be alcohol, which for them acts not only as a disinhibitor but by temporarily reconfiguring something more mysterious in their brains. I don't know. Until I see evidence of that, I'm going to continue judging people who are abusive and terrible while on the bottle as (at least in part) bad people.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was delighted to see this essay, leading with "If something can be fully explained by reference to the natural world, can it still be considered miraculous?", on Freddie deBoer's list of subscriber writing links. I know I did some mild delving into this question back 15 or so years ago in my more philosophizing and actively anti-theist days. It's a topic that has always made me happy, actually, as I've long been of the mind that the most amazing things nature throws at us can and should be considered miracles even though they can be explained entirely naturalisticly (and in fact, having naturalistic explanations made them all the more beautiful to me -- the fact that the most breathtaking models of our world are the ones that reduce to laws of nature is where I feel most profoundly on the same page as Carl Sagan).

I vividly remember wanting all those years ago to get around to writing some kind of essay on it someday, but deep down I probably knew that I would never quite find the necessary writing skill. In summer-to-fall 2011, when I got enthusiastically involved with the first Unitarian Universalist congregation I knew (which, in sharp contrast to the congregation I knew a decade later, embodied the inquisitive-scientific/philosophical-thinking vibe that resonated so well with me), there was actual discussion between me and some of the people in charge of having me lead a service and deliver a sermon that I had in mind to be specifically on this topic. It never wound up materializing, but looking back I'm quite amazed that myself (a newcomer not involved with the congregation in any formal capacity) leading a sermon was even floated (it was a fairly modest-sized congregation but not tiny by any means).

Anyway, when I actually read the above-linked article, I did find it well-written and interesting, but it went a very different way with the question than I would have: I am absolutely not inclined to point to amazing natural events -- least of all ones whose naturalistic explanations are completely well understood -- and suggest that they are evidence of some intelligence in the cosmos or (worse) that humans are privileged. (And by the way, while I agree that the size ratios matching the distance ratios is an enjoyable coincidence, I think something the author didn't consider is that anything on the larger/closer-moon side of that coincidence would enable inhabitants of a planet to experience eclipses: in fact, with a slightly larger or closer moon, total eclipses could be a bit more frequent and accessible, which seems to me like something a divine intelligence who wants to privilege said inhabitants might favor.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My views on TERFs and what TERFism is really about are evolving because over most of my past decade of being aware of trans issues I had almost no direct exposure to TERF rhetoric and it felt more like a boogeyman that everyone talked about than something that was actually visible (even the few TERFish voices I've heard directly -- mainly JKR and Helen Joyce -- seem to be kind of TERF Lite). But I'm getting more and more the impression that a lot of their belief system stems from a deep-seated jealousy of male-bodied people and a grudge against nature for making them female -- not in the way that AFAB trans people might not like being physically female, but in hating being part of the smaller, physically weaker, more vulnerable sex, having to have periods and the burden of pregnancy and childbirth in order to have biological kids, etc. Their underlying (but not usually explicitly stated) feeling seems to be "Being a woman sucks!" (This is more speculative, but I imagine in many cases this even gives rise to an inferiority complex about being female, as ironic a twisting of feminism this is.) And this naturally gets channeled into resentment of male-bodied people infringing on an identity whose most salient aspect (for them) is femaleness: "These men are lucky enough not to be born women and have to deal with periods and fearing for their physical safety and tons of other disadvantages they can't even imagine, and now they have the nerve to masquerade as women without actually having to deal with any of the crap that comes as part of the package."

I find this a very human response but ultimately irrational, misguided, and harmful, and both in a rather similar way to the feelings of those who oppose student debt forgiveness on the grounds of "I worked my ass off to pay off all my student debt, so why should someone else get to have it disappear like magic?"

To be clear, some degree of resentment towards nature for playing the cruel trick of giving half of us the sex which comes with considerably more pain and challenges, and asking male-bodied people to be aware of it, is valid I think (say I, the cis man who can only sympathize). But making these disadvantages such a big part of one's identity and taking it out on other people is one of those things that I sensed as an element of pop feminism in the early 2010's which I'm glad seems to have receded quite a bit, I think partly because of the growing polarization between the trans movement and TERFism, which as I've said before, I can't help viewing as a silver lining to the situation. And the points that people above me in this thread are making about femaleness-positivity just add to the reasons I'm glad to see the strident negativity recede.

124K notes

·

View notes

Text

I read this article claiming a trend among Gen-Z-ers towards defining sexual orientation in non-concrete terms from the most recent ACX linkpost, and, while I think some worthwhile insights can be extracted from it and it's definitely worth reading, I find that either the article is very badly written or the author is quite confused about what sexual orientation has generally meant long before Zoomers came onto the scene.

If you've been following me long enough, you probably have an idea of how bothered I am by younger generations' (not by just Zoomers but also my generation directly above them) growing fixation on identity labels and increasing tendency towards defining them nebulously while simultaneously placing great importance on them (for my "nebulously" complaint, for instance go to the March 2023 part of my archive and see, like, a whole sequence of my posts on what seems to be happening with the definition of "trans" and how that affects my perception of trans activist rhetoric). But, in the case of sexual orientation, an internal experience rather than a sum of one's actions is... always how we defined it? At least, since my formative years (early '00's), so I thought? Sexual orientation (like anything called "orientation") refers to a proclivity towards something, not directly to what someone actually does as a result of that proclivity.

(There is such a rare thing as a "political lesbian" or someone who calls themself bisexual but appears to be bending over backwards to achieve that label for status points, but this has been the case for decades and isn't a youth thing.)

The author repeatedly implies (even if she wouldn't quite stand by this if pressed?) that sexual orientation up until two seconds ago was determined by the sum total of one's sexual behavior. I find this logically leads to all kinds of contradictions to common sense, starting with bisexuals for obvious statistical reasons tending to have more opposite-sex relationships even if they're equally attracted to men and women (the author even seems to acknowledge this issue at the top), sexual people very rarely or never having sexual experiences because they have other reasons to avoid them or have great difficulty finding them, and asexual people grudgingly choosing to have sex as part of a relationship with someone they're in love with (because maybe they don't positively desire sex but don't hate it either). That last is a fact about the asexual community that I remember knowing ever since I found out there was one, when I was a teenager and a lot of Zoomers had barely reached school age.

The fact that sexual orientation refers to attraction felt subjectively rather than behavior, and has referred to this for decades, seems not only obvious in practice but obvious from the standpoint of how to most reasonably define categories of people where sexuality is concerned. Of course there will always be a correlation between sexual orientation and sexual behavior, and if that correlation is weaker today, well, that's what one would expect from a generation that is a lot more averse to having sex or doing meatspace things in general than previous generations were.

It's true that a lot of the more hateful edge of homophobia has appeared, in my lifetime (and I would have thought much earlier), to be aimed at people behaving a certain way, while people who merely feel a certain way have typically been viewed as "sick and needing to be cured". So that might seem like an argument for basing identity on behavior rather than internal experiences, but then again, (1) should the gay community necessarily want to define their identity primarily based on the precise way they're most oppressed?, and (2) it's not at all obvious to me that those caught up in the stronger forms of homophobia don't tend to blur behavior with urges in their ethical judgment anyway. After all, look at how pedophilia (an orientation, experienced internally) constantly gets blurred with child molestation (an external action) due to (righteously) extremely horrified attitudes towards the latter.

Anyway, again, there are interesting ideas in the article, and if it's true that Zoomers now tend to define sexual orientation in terms of "vibes" or "aesthetic" and are divorcing it from actual sexual feelings, then the author has a point and I'm alarmed that nebulous identity -obsession is reaching new heights. But the author needs to ground this in the reality of what sexual orientation has always meant a little better for me to be able to believe her claims. And for the record, I have yet to encounter anyone of any generation, including on Tumblr, who defines sexual orientation as an aesthetic or vibe rather than being attracted to one gender or another (with the possible exception of one acquaintance my own age, in the early '10's, who openly claimed that not only her bisexuality but all bisexuality is a "fashion statement", but digging into where she was coming from on that, as offensively wrong as her view was, it doesn't seem to line up with what the phenomenon the author is talking about).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know if there's a name for this trope, but lately I've been thinking of a character that pops up from time to time in literature, which can be described as someone with quirky magical abilities used to promote the deserving and punish the wicked, playing a crucial role in the plot by doing this, but who on a more personal level has an amoral streak, or isn't particularly nice or kind, and whose methods are ethically suspect.

Willy Wonka from the original Charlie and the Chocolate Factory book, and to some extent also the Gene Wilder rendition of that character, exemplifies this for me. I saw the Wonka movie that came out around last December and found it fun and entertaining but on a fundamental level was bothered by how perfect, idealistic, and saintly they wrote the young Wonka to be (without acknowledging any dissonance between that version of him and the Wonka we already knew from the original book and movie, or indicating that some change in his character would arrive along the way).

It's hard for me to come up with other examples that direct, especially ones that aren't somewhat obscure, but maybe Yay in Questionable Content in their earlier appearances (eventually, as with most QC characters, Yay drifted towards the central gentle-hearted-with-some-quirks default), or, more questionably, the Ellimist in the Animorphs series.

(EDITED TO ADD: Two days after originally writing this post, I'm delighted to see a direct comparison between Willy Wonka and the Ellimist appear on my dash.)

In the Disney and Broadway musical version of Beauty and the Beast, I have to interpret the enchantress (basically never seen, only showing up in the prologue, but crucially setting up the entire backstory) as exactly this type of character. I'm not sure that punishing a selfish person by turning him physically into a beast and only allowing him to un-transform if he managed to form a genuine romantic relationship with someone, when he didn't understand the concept of genuine relationships in the first place, was really the best approach. But even accepting for the sake of argument that it was, I was bothered for years by the fact that she enchanted the other occupants of his castle as well, turning them into household objects so that they were essentially imprisoned along with their already unpleasant and now bitter and rage-prone master. For a long time I viewed this as a plot hole, and apparently so did a lot of other people because an awkward line or two was added to the musical version to "explain" it and a bunch of lines with an even more tortured explanation were added to the (IMO rather bad) recent Emma Watson movie adaptation. I now think this shouldn't have been treated as a plot hole, and the enchantress' decision to punish everyone along with the prince should have been left alone with no explanation added. The enchantress (really maybe better called "witch") character can simply be interpreted as falling under the "Wonka mold": she knows profound selfishness from genuine capacity to care for others but likes to punish people for the former in a way that itself doesn't have to conform to the highest standard of ethics. (Note the irony that the clumsy explanations offered, which if I remember right boil down to "the people around the Prince didn't do enough to stop him from turning into a bad person", make the witch if anything look arguably rather victim-blamey and worse and an even less perfectly just agent than before attention was called to her decision to enchant everyone.)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Its impossible for me to actually summon up that much indignation about cops sweeping up protesters blocking the highway (or train station, or seaport, vel sim). Even when i support the protesters. Highways without ppl willing and able to try and clear them of blockades are tantamount to no highways at all, and a life without highways for supply chains would be pretty bleak. Thats the whole point of activists targeting them in the first place: to hold the economy hostage as a negotiating tactic. There are limits to whst force it will be reasonable to use, but its important there be any threat of force at all. The fact we have cops charged with clearing off interstates is a good thing

Sometimes a blockade will be a proportionate measure in the service of a righteous cause. But "clear away ppl blocking the road, unless their cause is just" is not a social technology it is actually in anyones power to implement in hoc saeculo. Perhaps there is some sense in which, faced with the good kind of protesters, each individual highway patrolman should abandon his post in the service of the categorical imperative or whatever, but obviously expecting that to happen en masse and without any serious effort to make inroads among them is just asking for a miracle, and if you ask for the sea to be miraculously parted and it isnt maybe in a way it is reasonable to be angry at god about it but its pretty stupid to get all outraged at the water

If you are trying to force a blockade of an economic chokepoint, and our porcine friends take exception, i think basically the way to think about it is that they are doing their job, and you need to stay focused on doing yours. Unfortunate that the two have to be at odds with each other like that but thats just life in a fallen world

#reblogging because endorsed#this is how i've always leaned towards thinking about it#protesting#police

182 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yeah to clarify, I don’t have all the sources on hand, and maybe some of these are contradicted by better research somewhere, those are just things Ive seen floating around

I think the Autism Fetishes thing personally is most likely “ tendencies for special Interest / Hyper fixations ” + “Sex Drive”+ probably a bit of “ less responsiveness to peer pressure allows for more diverse tastes to develop beyond Conventionally Attractive person with focus on face and genitals” ( at-least in general, why some more than others is a whole other bigger conversation)

The Digestive issues thing is interesting, it includes constipation or diarrhea ( as well as heartburn), which is pretty simple for an outsider to conform, but maybe a side effect of picky eating ( especially since the research is mostly on children), so it might just be a sensory thing actually in a roundabout way, This is probably the most well known “ non mental” autism thing, and has been hyper-fixated on by some Autism Moms( TM) that hope the right diet or supplements will “fix” There child

Such explanations make a lot of sense (the connection between pickiness about food and digestion issues did occur to me). I actually meant, but forgot, to mention that the one hypothesis I've ever heard implicitly relating autism to handedness would imply the opposite of what you said in your last ask about autism being correlated with left-handedness, and has to do with a certain kind of autism presenting as being severely left-brain dominant (which would then imply right-handedness). But this is an anecdote coming from what someone was told by a psychiatrist some three decades ago, so of course I'm inclined to trust what recent studies say over that.

#autism#fetishes#digestion#handedness#pretty wary of the Autism Mom epithet in general#but yes trying to “fix” one's autistic child via diet is obnoxious

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a list compiled of things that have been found to have a positive correlation with being autistic/having an autism diagnosis, I think the problem is which of these are labeled as part of/symptoms of “ autism” vs which just happen to correlate with autism, isn’t really consistent, ( I’m really not convinced “ autism” carves reality at the joints and is the categorization doctors will use in 100 years anyway)

- (Homo/bi/A)sexual and/or trans

- Fetishes

- Language issues( delayed speech/being mute/ speech impediments)

- Left handedness

- Special interests

- Digestive issues

- Difficulty identifying their emotions(alexithymia)

- Stimming( repetitive figiting as a way to relax)

- Preference for routine

- Less easily succumb to peer pressure

- Sensory processing problems( more sensitive to bright lights and/or loud noises/ intense discomfort to some other textures( edible and/or non edible)/ discomfort with making eye contact etc )

- Strong sensory pleasure from heavy pressure/certain textures

- Stronger sense of morality

- Seizures

- Poor hand eye coordination/motor skills

- Shorter foot strides

- having anxiety/depression/adhd

- Ehler Danos syndrome

- Worse at safely metabolizing BPA

- Bufotenine in urine

This is an interesting compilation! I've suspected many of these suggested correlations myself, while others (at least the last three) have never crossed my mind and/or are things I've never quite heard of. Some notes on a number of these below.

Language issues, special interests, difficulty identifying emotions, stimming, sensory-procesing problems, and preference for routine are just classic textbook features of autism, of course.

I'm not sure I've ever seen reasons for why homo- or bisexuality is correlated with autism (maybe bisexuality a bit, for extremely indirect subcultural reasons? autism is visibly overrepresented in the queer community for Reasons). I suspect asexuality is correlated slightly with autism, but at the same time, many or most autistic people I've known appear to be highly sexual. Being trans is absolutely correlated with autism (Aella found this stood out dramatically from some of her data), and this is an observation that many on the anti-trans side of today's culture wars like to point out, and I think (uh, let's hope without dragging myself into another big debate) not without reasonable concern?

I've postulated (but not out loud until now) that autism might cause certain kinds of fetishes, with theories as to why, although I don't feel comfortable even here diving into my full thinking about what might be going on here. Anyway, it's interesting that you listed that because I don't think I'd heard anyone else mention it before!

The digestive issues thing has crossed my mind as well, although my very, very speculative idea is that autistic people might on average just be hyper-aware of digestive sensations? I've again never heard anyone else claim it before.

Stronger sense of morality, as far as I know, was recently confirmed in a study that is celebrated around these subcultures. I find its conclusion believable enough, although it's hard for me to disentangle it from my general impression of everyone in younger generations framing things in starker, more black-and-white, more desperate moralistic terms, as a result of (to my view unfortunate) recent changes in our culture.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Thank you for this explanation -- I mean that sincerely, beyond polite acknowledgment, because it's helpful to me to hear from people more informed in this general arena than I am if I'm going to continue to opine on it. My thinking and argumentation on this topic were indeed sloppy, as far as distinguishing between Actually Having a condition and testing for that condition goes. I'm still not entirely convinced of where to draw the line, in the case of something like autism, between defining it in some direct, more in-the-abstract way and defining it in terms of the results of what comes out of certain tests, because it's hard for me to understand this distinction coming with a bright line rather than existing on some kind of epistemic continuum. We are trying to define Condition X (let's say, with extremely complex subjective properties coming from how brains work) as some cluster of states in thingspace: to what degree can we cut out that that cluster of things from thingspace definitionally without bringing in some kind of diagnostic tests with results viewable to outside observers? Or to put it another way, where is the line between descriptive and prescriptive definitions of these kinds of (subjective-experience, hard-to-measure) conditions?

(I mean some kind of sufficiently good and thorough test, obviously, not just any test, which is why I brought up the 15-minute ADHD test as suspected BS -- by the way, as I related in that string of old posts, some weeks later I did take a somewhat more sophisticated and thorough test whose results I trust somewhat more, and have always been willing to grudgingly accept the testing psychiatrist's conclusion that I don't actually have ADHD proper, although I would speculate that I arguably have a sort of non-central instance of ADHD as one part of the test did show up as highly abnormal.)

But you are right that there is an extremely crucial distinction here that I was ignoring, and that I need to understand this better. There's a lot of details missing from my knowledge of what people are saying about race/gender effects also, and I hope to learn more about that as well; I will mention that I come into that with some amount of skepticism of the way people frame that issue, but there's no doubt that gender at least must have some effect on the way something like autism presents.

Part of what was in the middle of my mind, in suggesting that autism must be by definition what a (good enough type of) test for it says, is a set of diagnostic criteria I ran across for PTSD (through an Ozy post a year or two ago, actually), which suggested to me that certain conditions do seem to be defined prescriptively in such a way that it's hard for me to conceive of a coherent modification to the definition without that prescriptive aspect. To put it overly-simply, from what I remember (I don't have the energy this minute to track it down), it listed a bunch of symptoms commonly associated with PTSD and categorized them in a fairly elaborate way, then said "for a diagnosis of PTSD, the patient must exhibit X or more of the items in the list under the Y category, etc.". This is clearly an imperfect and somewhat arbitrary way to carve PTSD out of the clumps of conditions in thingspace, but I'm legit sort of confused about whether there can be a way to objectively define what it means to have PTSD without this type of arbitrariness, without resorting to allowing a ton of vagueness into the definition: clearly there is some clump of states that we want to call "PTSD" which involves a "sufficient number" of these symptoms, but somehow we have to agree on a ballpark idea of what the "sufficient number" is and call everything exceeding it PTSD, otherwise we have a condition that could be interpreted to be near-nonexistent among humans or to apply to almost every human. (Contrast, I suppose, to borderline, whose most rigorous diagnostic process I learned something about during Amber Heard's trial around the same time I saw the PTSD criteria: here we have a condition that we're assuming is defined "in-and-of-itself descriptively" and that we're trying to detect through an elaborate strategically-designed series of direct personal questions given to the patient, who may have their own bias toward being or not being diagnosed.)

Anyway, if I understand you correctly, what you're saying in the broader context of this whole discussion is that diagnostic tests are often suspect, but there are other means towards figuring out if someone has something. I have often understood the default "other means" to be asking the patient about their subjective experiences, and I think the crux of our difference stems from my being much less trusting of this than you (and a lot of other people) are -- not suspecting that people lie, but suspecting that people do have their agendas and biases and, more importantly, don't know how to judge the degree of their own experiences relative to others. It occurs to me that there's a third means, though, which you touch on in your comments about ADHD: the patient, as well as people who know the patient intimately, can relate the frequent concrete, objective, externally verified, behaviors of the patient, and I'm sure that examining this (provided of course that we trust it's being related in an even-handed way) can yield a huge amount of useful information for diagnosis. I think we can agree that that may be the most valid means of diagnosing of all. (While to my perspective, of course, that's a long way from the idea that "everyone is an expert on their own brain".)

(Again, this whole response should be taken more as me musing out loud than trying to rebut any of what I'm responding to.)

I think you're very much over estimating how much professionals know about autism. Especially the average professional tasked with making diagnoses. They don't know shit dude

I definitely have the impression that your average run-of-the-mill psychiatrist or neurologist without a very specialized background in autism doesn't actually know that much about it or the intricacies of how to detect it, let alone (say) a therapist. I'm not sure if they're the ones who are even able to give diagnoses in the first place, given that the usual claim (which I've always understood to be correct) given by advocates of autism self-diagnosis is that getting diagnosed for autism requires spending thousands of dollars and many hours of time to be put through very involved tests as specialized autism centers that may be geographically unfeasible. (The only reason I'm entertaining the idea that autism could be diagnosed by non-specialists with far less trouble is that I do hear of various conditions being diagnosed that way despite the existence of rigorous tests in specialized clinics: I took a 15-minute ADHD test at a regular psychiatric clinic for instance*, and the ex I mentioned recently elsewhere got a Borderline Personality Disorder diagnosis from her therapist by request via what sounds to me like 10 minutes of the therapist asking her questions about herself during their therapy session.)

If we're talking about going to a clinic / testing center specializing in autism and going through a rigorous test evaluating whether the patient conforms to what the American Psychological Association has laid out as an intricate set of criteria for autism, then I have one question, which is probably going to sound naive, and which relates to the "diagnosis criteria is a poor checklist of stereotypes" part of the meme we were arguing over. Which is, isn't this then just tautologically the correct way to diagnose autism? Or in other words, isn't autism just defined according to a scientific model for which psychologists and neurologists have created their most official tests following their most precisely-set-out criteria? Of course, what is deemed "autism" could be modified by said scientists, which after all is the nature of science. Of course, people can argue over whether the current criteria cut autism poorly out of thingspace in ways that are biased due to differences in how autism presents across genders and ethnic/cultural backgrounds. Probably it is. But I would think that deciding that the formal diagnostic criteria for autism doesn't align with what autism Actually Is requires some delicate semantic heavy lifting, no?

And then, arguing that the larger swaths of non-professionals who are trying to determine if they have autism are still not on average even worse placed than the professionals with their perhaps flawed diagnostic criteria, in a world where the most common cultural conception of autism is still probably pretty close to "socially awkward, doesn't feel like they fit in, intense nerdy interests, personality of Sheldon Cooper", is another thing.

(I notice, by the way, that self-diagnosis advocates don't seem to mention whether the faultiness in professional diagnoses include a substantial number of people without autism being diagnosed as having autism, but it seems that should be a thing too if the professionals really "don't know shit"?)

I'm genuinely open to the idea that the dynamics around diagnoses and diagnostic criteria and how they're formed, etc., even on a philosophical level, is something I haven't understood or thought out well enough, though.

*and came out of the experience rather skeptical that the 15-minute test way of determining ADHD isn't BS

#categories#a bit all over the place#i'm feeling a bit foggy at the moment#but wanted to finally respond to this#ptsd#borderline personality disorder#depp vs. heard

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

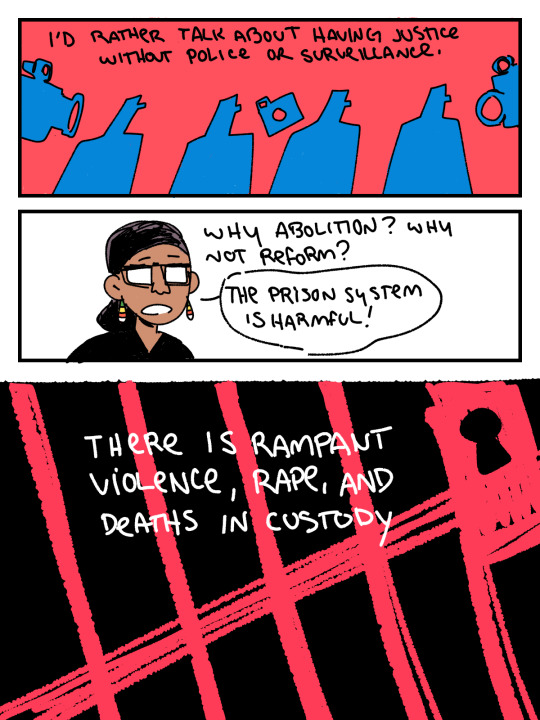

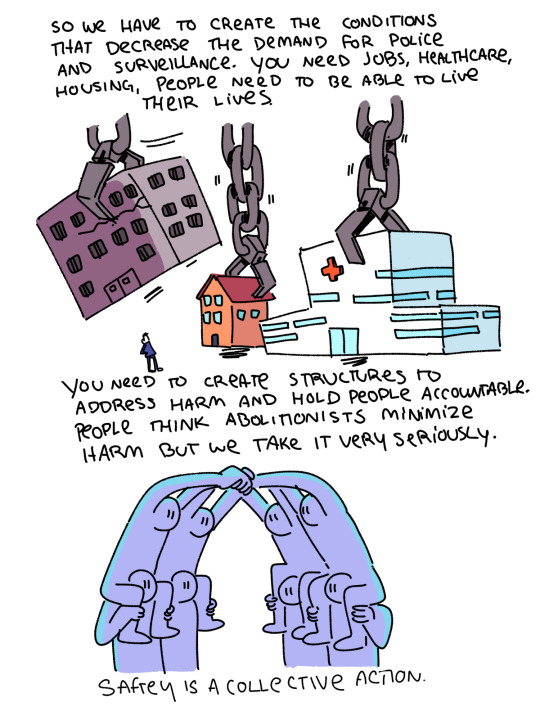

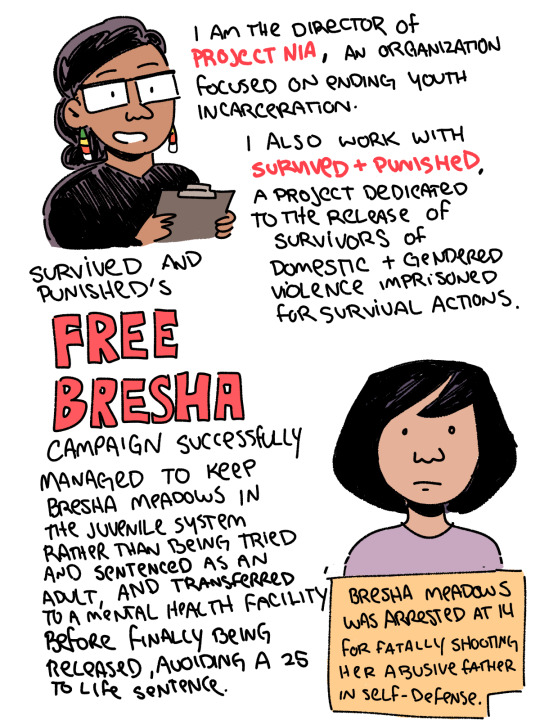

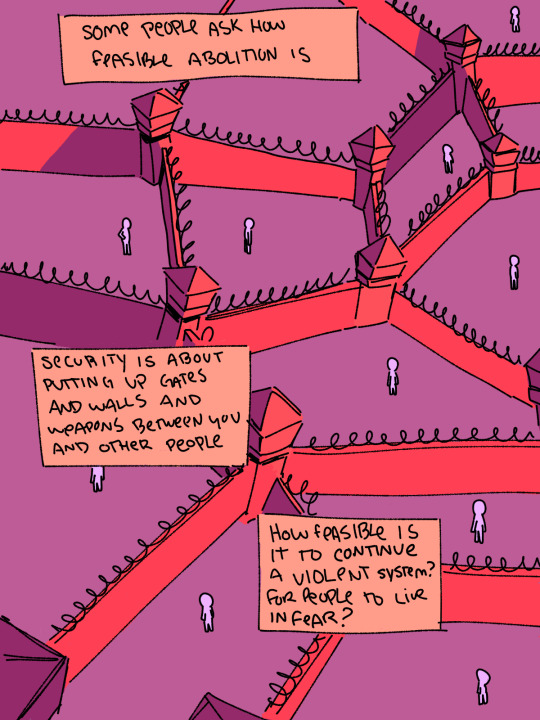

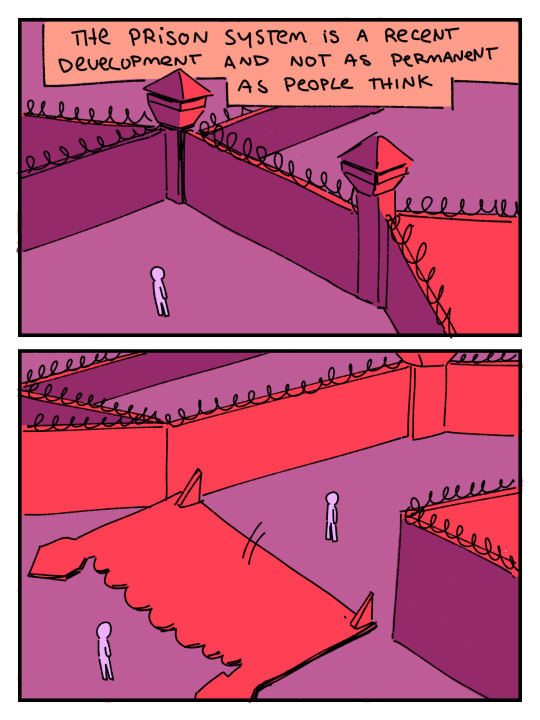

I have a lot of prison abolition sympathies -- I'm certainly closer to a prison abolitionist than a police abolitionist -- but jambeast is entirely correct here in their take and has expressed it better than I would have been able to.

who’s left- Mariame/Prison Abolition

by Flynn Nicholls

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep hearing people like Jonathan Haidt say things like, "Millennials are doing fine; it's Gen Z that's having a mental health crisis. Something has gone terribly wrong just in time for Gen Z." (Okay, others aren't exactly saying that right out, but it's kind of implied: a lot of focus on what cohort is personally struggling singles out Gen Z.) And I find this incredibly depressing, because, I mean, we millennials really aren't exactly in the most robust mental health, you know? And it's not like we aren't visibly struggling a ton? It's just, wow, I don't know many Gen Z -ers closely (they comprise the students in my classes though), and if millennials are doing so well in comparison that millennials' issues aren't even worth mentioning in context, then Gen Z must be really screwed.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think you're very much over estimating how much professionals know about autism. Especially the average professional tasked with making diagnoses. They don't know shit dude

I definitely have the impression that your average run-of-the-mill psychiatrist or neurologist without a very specialized background in autism doesn't actually know that much about it or the intricacies of how to detect it, let alone (say) a therapist. I'm not sure if they're the ones who are even able to give diagnoses in the first place, given that the usual claim (which I've always understood to be correct) given by advocates of autism self-diagnosis is that getting diagnosed for autism requires spending thousands of dollars and many hours of time to be put through very involved tests as specialized autism centers that may be geographically unfeasible. (The only reason I'm entertaining the idea that autism could be diagnosed by non-specialists with far less trouble is that I do hear of various conditions being diagnosed that way despite the existence of rigorous tests in specialized clinics: I took a 15-minute ADHD test at a regular psychiatric clinic for instance*, and the ex I mentioned recently elsewhere got a Borderline Personality Disorder diagnosis from her therapist by request via what sounds to me like 10 minutes of the therapist asking her questions about herself during their therapy session.)

If we're talking about going to a clinic / testing center specializing in autism and going through a rigorous test evaluating whether the patient conforms to what the American Psychological Association has laid out as an intricate set of criteria for autism, then I have one question, which is probably going to sound naive, and which relates to the "diagnosis criteria is a poor checklist of stereotypes" part of the meme we were arguing over. Which is, isn't this then just tautologically the correct way to diagnose autism? Or in other words, isn't autism just defined according to a scientific model for which psychologists and neurologists have created their most official tests following their most precisely-set-out criteria? Of course, what is deemed "autism" could be modified by said scientists, which after all is the nature of science. Of course, people can argue over whether the current criteria cut autism poorly out of thingspace in ways that are biased due to differences in how autism presents across genders and ethnic/cultural backgrounds. Probably it is. But I would think that deciding that the formal diagnostic criteria for autism doesn't align with what autism Actually Is requires some delicate semantic heavy lifting, no?

And then, arguing that the larger swaths of non-professionals who are trying to determine if they have autism are still not on average even worse placed than the professionals with their perhaps flawed diagnostic criteria, in a world where the most common cultural conception of autism is still probably pretty close to "socially awkward, doesn't feel like they fit in, intense nerdy interests, personality of Sheldon Cooper", is another thing.

(I notice, by the way, that self-diagnosis advocates don't seem to mention whether the faultiness in professional diagnoses include a substantial number of people without autism being diagnosed as having autism, but it seems that should be a thing too if the professionals really "don't know shit"?)

I'm genuinely open to the idea that the dynamics around diagnoses and diagnostic criteria and how they're formed, etc., even on a philosophical level, is something I haven't understood or thought out well enough, though.

*and came out of the experience rather skeptical that the 15-minute test way of determining ADHD isn't BS

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Google Pocket Somethingorother that shows me a hodgepodge of articles to click on when I open a new tab using my browser pointed me to this interesting Atlantic article on how much is obligatorially conveyed in typical sentences of different languages via inflection and other devices (for some reason it's behind a sort of paywall now even though I don't think it was when Pocket recommended it to me?). I recognized the article immediately because I remembered posting it to Facebook back around the time it came out in 2016, because it gave a good layperson's explanation (using intuitive terms like "busy-ness") of what having an inflective vs. analytical grammar means. The experience stuck in my mind mainly because of how one of my most active Facebook friends at the time (who remains perhaps the most athletic bending-every-topic-towards-their-special-interests-which-are-mainly-their-marginalized-victim-identities I've ever known, and whose first language is a highly inflected and non-European) commented under it that the author clearly "doesn't like the 'busier' languages very much" but that as a speaker of such a language they could attest that even if the author saw all the inflection as superfluous it was in some deeper sense necessary because "the language wouldn't really be the same without it". I'm trying my best to quote from memory, but I couldn't make any better substance or sense out of that comment than what I'm conveying here, and it struck me as a ridiculous interpretation of the author's attitudes.

On reading through the article again, I found that its author was John McWhorter. This is an example of something similar to what I mentioned the other day where I discovered Destiny and then discovered him again a few months later: I had vaguely known John McWhorter as a linguist from some point in adolescence when I checked out at least one of his books from the local library, and in 2016 I had probably glanced at the name at the bottom of the article and recognized it. But I didn't put McWhorter firmly on my mental map of Public Scholars/Intellectuals I Know until around a couple of years later when I ran into his political commentary on YouTube in conversation with Glenn Loury. (Ironically, McWhorter happens also to be extremely against bending-every-topic-to-one's-own-marginalized-victim-identities-ism, so maybe my 2016-era Facebook friend was onto something by instinctively marking him as an enemy.)

One concerning thing I noticed from the article is that McWhorter mentions the Maybrat language as having no way whatsoever to grammatically convey verb tense, and I couldn't remember having heard of the Maybrat language before, so I looked it up. The Wikipedia page shows that it goes by some other names such as Ayamaru, but I couldn't find it listed under any of its names in my Journey Through Languages Project (which I embarked on after 2016). And yet, it has some thousands of speakers and a Wikipedia page with a lot of details on its (interesting) grammar and phonology, one which I don't remember ever seeing at all. This shows that my project still missed some interesting languages -- in this case, didn't even come close by looking at a closely related language since Maybrat is a language isolate although classified as a Papuan language. I think it's clear that this occurred because the Wikipedia page on Papuan languages shows multiple classifications, and Maybrat only shows up in a 2019 one which may have been posted after I was reaching it in my "journey". But it disabuses me of my proud notion that I am one of the few people who has clicked on every single language page on Wikipedia.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I may as well share my semi-effortful (though rambly) comment on one of Ozy's recent posts criticizing Amanda Shrier on her recent anti-therapy-culture book, as I imagine more people might see or interact with it here than in that comments section. What I'm most interested in here is, what does it mean to experience the emotion of happiness?

I learned of Shrier's existence and her book from seeing her interviewed by Coleman Hughes on his podcast, and I thought throughout that interview Shrier sounded like she was made of good common sense (it helps that I'm already broadly in sympathy with wanting to push back against what we might call "very online therapy culture" which Ozy seems also to be in agreement with), with an exceptional moment here or there: for instance, at some point one of them (I think it was Coleman) seemed to imply that it's good when children are slightly scared of their parents. While there may be some empirical evidence somewhere that children who are slightly scared of their parents stay on the straight-and-narrow and have more positive life/career outcomes or something, this idea still massively creeps me out. But still, overall in conversation, Shrier comes across as reasonable. I think this sequence of posts tearing apart her parenting beliefs as expressed in her book (unless a bunch of these quotes are grossly taken out of context in some way I can't see) show that she's less reasonable "in writing" and that her more deliberate beliefs that she expresses in her work represent a pushback that is righteous initially but goes to an unfortunate far extreme in the other direction.

The part of her interview that stuck in my mind the most, actually, was her line about "We used to ask kids such-and-such; now we ask them about their feelings all the time", which wasn't something that had occurred to me before but I was open to where she was coming from. So I find the response to it in the end of this article interesting. I don't say this with much confidence, but I tend to feel more like Shrier on the issue of how often we're actually feeling the emotion of happiness, although I don't think I'm clinically depressed or at all prone to it (although I have a rather negative outlook at the moment about my future prospects and the world in general which may prevent me from feeling much wholehearted happiness, but that goes for a lot of us. I think perhaps a majority of people relate more to Shrier here. Just yesterday or so, I saw a post from a Tumblr mutual saying they haven't had a single actually *pleasant* day in years like they used to in the 2010's, only "good given the worse background situation" days. This seems to relate to the same idea. Maybe due to recent shifts in world events most of us have moved in that direction? I don't know.)

I would suggest actually from reading the end of this article that the difference might come not from psychological make-up but from a disagreement over the definition what it means to feel happiness, where Ozy's definition aligns more with what Shrier and I would call "feeling okay".

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's got to be some Star Wars prequel trilogy parody out there in the vast world of Star Wars parodies that plays on the similarity between "youngling" and "Yuengling". Like, the scene is the aftermath of someone looting and burning down a beer shop. "Not even the Yuenglings survived." Someone has to have thought of this... right?

#shitpost#star wars#looting#alcohol#btw i don't think grocery stores sell beer in pa#but i chose pa because it's where yuengling is brewed#so had to go with beer shop

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another few words on this, which I decided to save for a later reblog because it's not directly in response to what loki-zen said.

The text by the Instagram post (which I acknowledged above as more nuanced and reasonable) is as follows:

We HAVE to move past this narrative that only doctors can diagnose you for all things. There are many times when an official diagnosis isn't viable.

Not allowing room for self-diagnosis in the world is keeping people who desperately need accommoations from getting them for reasons that are completely beyond their control.

Does this mean that some bad actors will take advantage of self-diagnosis? Yes. But why should we be denying access to people in need because a few people MIGHT take advantage?

I entirely agree with the last paragraph (it's a philosophy I strongly align with in general: don't deny a whole group things because a few might take advantage), but I think it's somewhat missing the point, at least where a lot of us skeptics of various stripes are concerned. I'm not really worried at all about bad actors claiming a "fake" autism to get accommodations or whatever. I'm concerned about good, well-intentioned people gravitating towards diagnoses of things like autism (or depression or ADHD or PTSD) for symptoms of some other neurodivergence or of Being A Person, being too eager to fit under diagnoses in general which might lead to them incorrectly thinking they're unable to do things without external help, and watering down categories and conditions which starts to trivialize the seriousness and substance of said conditions like real autism (an already overly-broad spectrum!).

I know in the context of this set of posts (and perhaps many others) I seem to be missing this mood, but it also worries me that there are lots of autistic people who are unable to get a formal diagnosis (which I do know is extremely expensive and time-consuming) or recognize themselves or be recognized as autistic, and this is also very bad. And for the record, with all other factors at default settings, if someone tells me they're autistic but lacking a formal diagnosis, I believe them. (I don't think I've ever once felt skeptical about someone's claim of autism on Tumblr, for instance, because of general lack of evidence that the individuals I run across here have a watered-down concept of autism.)

I suppose the literature I'm advised to look up points to the latter being an overwhelming (like 95%) share of the problem. Even if that's true, I believe just from direct experience that there's a swath of people (maybe not psychiatrists) whose beliefs and assumptions about this are sliding way too far in the opposite direction. I'm worried that it's primarily those people, who are already more than credulous enough about autism self-diagnosis, who are most receptive to memes with overstated messages like the above. A very diagnosis-happy subculture will continue to pull away from the rest of society on this kind of issue (one of the main effects of this is of course that they'll have even less credibility with the "doctor class" who treats formal diagnoses as sacrosanct).

My Recent Ex (honestly not that recent anymore but most people's standards, I guess, but still feels quite recent on my life's timeline), some months before she and I met, talked to her psychiatrist about the possibility that she had autism. Her reasons for suspecting she had autism were "I've always felt different from other people" (pretty much her exact words to me when I asked her this); the strongly implied backdrop to this recent chapter of her life story was that tons of her (very queer-culture, neurodivergent, mentally ill, constantly-talking-about-diagnoses) friends had suddenly started talking about autism a lot, particularly about how it's underdiagnosed in girls who are more likely to mask it, etc. Now in the almost-year I was dating her, the only characteristics that ever struck me as remotely (but very peripherally) autistic were her occasional mild trouble keeping her voice at a reasonably low volume and her dislike of inconsistent texture in tomato sauce and jello, while many of her other qualities (especially social) flew almost comically in the face of the best-known aspects of autism. She's non-NT to be sure and already at this time had diagnoses of clinical anxiety, panic disorder, fairly severe ADHD, and bipolar-eventually-replaced-by-BPD.

Anyway, when she brought up her suspicion that she had autism to her psychiatrist, he was not only dismissive but went off on a rant about "I don't understand why everyone wants to have autism nowadays". I think this was quite unprofessional of him, first of all, and secondly I absolutely loathe what we may call "performative not-understanding" (as my ex put it, "Isn't it a big part of his job to try to understand?"), so this story pisses me off at the psychiatrist and I couldn't blame my ex for not wanting to see him anymore. But I was also afraid she might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater by missing the fact that he had a point about "everyone wanting to autism nowadays", even if this wasn't the nicest way to phrase it and he should have been confining his rants about it to colleagues, not patients. And she, by pretty clearly not fitting much if any of the characteristics of autism except vague feelings of neurodivergence while still desiring yet another diagnosis to add to her collection, had kind of illustrated that point. (To her credit, she did a little more research and concluded soon afterwards that she probably didn't have autism. But tons of people aren't objectively truth-seeking or intellectually honest enough to do that.)

From theneurodivergentadult's Instagram:

Yeah it's probably not such a great use of my (or any of my followers') time to rip apart everything in this meme to justify why I object to it to the extent that I do. And some of my followers may already have a pretty good idea of where I'm coming from regardless of whether they agree.

But let's just say that it serves as a good example of the absolute epitome of the set of (sub)cultural beliefs and assumptions that these years I complain about the most, including the "internal experience supremacy" idea ("humans are the experts on their own minds" is ugh such an exasperatingly misguided conviction and this is from the same social movement that increased awareness of mental illness and therapy culture both of which kind of hinge on not always understanding one's own mind aaargh).

Really, though, I should point out that at least half of my issue with this comes from the meme format which encourages stating one's point in an absolutist fashion at the expense of nuance. The text by the Instagram post explains that we should be open to the possibility that someone is autistic without medical diagnosis, which is a reasonable position that I agree is justified by several (though definitely not all) of the points mentioned by the meme, and is a far cry from "self-diagnosed autistics are valid".

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, I see I've encased myself in another "layer" here (who could have imagined that posting something on Tumblr about the dynamics of being diagnosed with autism would attract responses worth engaging with?). Since I have a bit of time this morning, let's see if I can respond quickly while the topic is "hot" on my mind.

We can agree that it's best to acknowledge the meme format and the limitations it imposes and that a meme should only be criticized with acknowledgment of that context. Still, I feel like they could have tried a little harder, ya know? Heading the meme with something like "Why not to dismiss self-diagnosed autistics" rather than "Why self-diagnosed autistics are valid" is hardly any more characters but like ten times more reasonable and almost certainly less likely to discourage a naive reader from taking the rest of the meme seriously. Really, when I was saying the meme format "encourages" an absolutist, un-nuanced way of stating things, I was referring not only to the fact that it directly limits the number of words and so on but to the meme culture that has sprung up around memes which seems to encourage absolutist statements -- the former is just a hard limit, but the "meme culture" part is something we could work on, I think.

I sort of understood the meaning you provide for saying someone "is valid" (if asked, I would probably have translated it, in this case, as something closer to "is for all means and purposes correct about their autism status" with some vague cloudiness around that, which is close if not functionally identical to to "should be treated as correct about their autism status"). I'll admit that I often get confused and tripped up over what it means in common internet parlance "to be valid", I think particularly since the most prevalent use of that predicate seems to be an (often with no context at all) affirmation of "you are valid", which (like its close cousins "you are enough" / "I am enough" / "I feel like I'm not enough", etc.) has always struck me as a completely vapid and meaningless assertion/mantra and precisely encapsulates much of what I hate about "very online therapy culture".

Where the "experts on their own minds" assertion is concerned, although I acknowledge that there's a variant of it I can be more charitable to, it's hard for me to address it without being completely scathing as well as expressing fear of how dangerous I find it. You mention understanding it (and other things) in context. That's entirely fair, but I want to point out that my reaction to these things also comes from a context, in this case a (sub)cultural context of frequently seeing in the last few years, in a variety of object-level contexts, "each person's experience within themself is the only truly reliable arbiter of true statements about that person", packaged into very close variants of the phrase "everyone is the expert on their own mind".

The variant I can acknowledge as reasonable would be this: someone spends a million times more time with their own brain and body than any psychiatrist or doctor, and there is a danger (and perhaps very common occurrence) that a psychiatrist or doctor is so mired in their own academic knowledge of psychological/medical conditions that they lose sight of this and don't listen to their patient's testimony when it seems to contract their overly-tidy theoretical framework. This is I think more or less the interpretation you're pointing out to me. (And yes, I realize the way I just phrased it is way too long for a one-page meme.)

Here's the thing: it completely and utterly ignores the other side of the issue: that psychiatrists and doctors typically have a specialized knowledge of a condition itself that vastly outstrips that of the typical patient. (Sure, some patients have the intellectual and other resources to deeply research a condition beyond the list of common symptoms Google initially pulls up, on a level that may rival that of a particular doctor's knowledge, but such people are far from all and probably few and far between. Most people aren't as smart or in possession of as much regular online time as the typical Tumblr nerd, for instance.)

A simpler way of phrasing this, but a framing I find very, very relevant, is this: as much as we may usually know our internal experiences much better than someone else knows them, knowing the nature or even understanding the very definition of a particular condition (whether autism, depression, anxiety, PTSD, DID, etc.) is an entirely different matter, completely independent of the fact that we know our own experiences. (It's a bit like if I went around saying "I know my own home and its quirks a hundred times better than someone whose exposure to it was only a half-hour visit one time; therefore I know better than the contractor I hired who says the leakage situation can't be fixed without replacing the ceiling. He has a bias to make money anyway.") This seems like a huge, huge point of negligence behind proclamations of "everyone knows their own mind best" in the context of trying to find out if you have a particular condition.

(Very relevant to this: bravo* to the mental illness blogger Ozy for their on-the-money critique of internet mental health culture yesterday.)

In the case of autism, let's consider that, despite a dramatic increase in autism visibility in the media and general culture over the last 10-15 years, a ton of the people I run across still seem to have only a rather vague idea of what autism (already a very overly-large umbrella category even in the formal literature!) is. Their level of understanding come across as characterizing it as some sort of condition that makes people act social awkward, feel like they don't fit in, and sometimes take things too literally. For instance, I've seen a lot of folks casually attribute autism to other people either to (partially) excuse them for obnoxious behavior or to express a disgust reaction towards them, both of which I find ableist in a certain way, and this is including among highly educated, relatively socially aware people. (No less an educated intellectual than Sam Harris comes uncomfortably close to the latter uglier fallacy from time to time.) I imagine you've had a similar experience! There is a pretty prevalent baseline of little knowledge about autism, and that combined to my distrust of many people to be intellectually honest enough to try in the first place to do proper research, forms a lot of my concern.

As for checking out the literature on missed or wrong autism diagnoses, I appreciate the suggestion and none of the frustration I'm about to express is aimed directly at you, but honestly I do find such suggestions very frustrating. Where am I supposed to start (from nowhere but Google searches I guess) on looking up studies and data that somehow lead to a conclusion about the extent to which autistic (or non-autistic) people know their own minds better than psychologist experts in autism, in a way that spells out such a conclusion, and be sure that I'm thinking critically enough to understand what the misinterpretations of the data might be, or check that there aren't searchable rebuttals or that one side may be elevated for political reasons, etc.? My frustration is mostly with myself, actually, because pursuing this kind of thing has never been among my talents (I think that's apparent actually from a good look at the style of arguments I use, or don't use, when I talk about controversial things on this blog!). I agree in principle that results of some research of this kind could have a bearing on how I think about memes like the above one but have a hard time knowing if such results are truly evident.

*or brave? brava? I'm actually curious, how, in recent modern Italian, do we inflect an adjective describing someone nonbinary? The -e ending, as in Spanish, conveys ambiguity between masculine and feminine singular, but, unlike in Spanish, is also used for feminine plural.

From theneurodivergentadult's Instagram:

Yeah it's probably not such a great use of my (or any of my followers') time to rip apart everything in this meme to justify why I object to it to the extent that I do. And some of my followers may already have a pretty good idea of where I'm coming from regardless of whether they agree.

But let's just say that it serves as a good example of the absolute epitome of the set of (sub)cultural beliefs and assumptions that these years I complain about the most, including the "internal experience supremacy" idea ("humans are the experts on their own minds" is ugh such an exasperatingly misguided conviction and this is from the same social movement that increased awareness of mental illness and therapy culture both of which kind of hinge on not always understanding one's own mind aaargh).

Really, though, I should point out that at least half of my issue with this comes from the meme format which encourages stating one's point in an absolutist fashion at the expense of nuance. The text by the Instagram post explains that we should be open to the possibility that someone is autistic without medical diagnosis, which is a reasonable position that I agree is justified by several (though definitely not all) of the points mentioned by the meme, and is a far cry from "self-diagnosed autistics are valid".

#ozy#italian language#ableism#sam harris#what does it mean to be valid#my difficulties with looking up data

17 notes

·

View notes