#kokinshu

Text

In the mountains’ heart

Forging through the autumn leaves,

A calling stag:

When I hear his voice I feel,

Autumn is sorrowful, indeed.

0 notes

Text

i dream in the reds and oranges

and in yellows too

how wilted leaves covered

the path in front of me

relentless hope softly dying

or entering a heartbroken hibernation

i can't see any other hues

than the crimson leaves which fell

and that i once saw with you

~ season's changing, i'm busy though. i would love to be writing more

#original poem#poetry#poets corner#poets on tumblr#female poets#short poem#original poems#poemsbyme#poetic#poetsandwriters#short poetry#kokinshu#waka poetry

1 note

·

View note

Text

The 101st Poem of the Hyakunin Isshu

While watching competitive karuta online, and in person, I noticed that there is a certain poem at the outset of a match, but that’s interesting is that this is a poem that is not actually part of the Hyakunin Isshu.

Osaka (Naniwa) Bay at sunset, Quelgar’s photos, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This poem is called the joka (序歌), or preliminary poem, and…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Note

I really miss Vine. The 6-second time limit truly was a blessing in disguise.

--

The only short form shit I like is that translation of the kokinshu that's around here somewhere.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

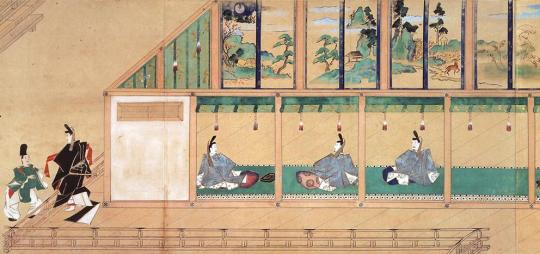

The most popular form of Japanese poetry for twelve hundred years has been the tanka. Ninety percent of the 4,500 poems in Japan's oldest anthology of poetry, the Man'yo-shu, are in this form, and of the one thousand poems in Japan's second oldest anthology, the Kokinshu, only nine are not. Since Emperor Daigo ordered the compilation of this second anthology, twenty-one collections were decreed by Imperial edict, the last compiled by order of Emperor Go-Hanazono in 1439. As a result this practice gave to tanka a most respected place in the history of Japanese literature. The tanka received Imperial patronage and produced, naturally enough, generation after generation of court poets.

To these court poets the poetry of the Kokinshu represented the height of polished technique. They made it their sacred book, one to be imitated eternally. But as time passed, many words and phrases were totally incomprehensible to the mass of readers. Those families versed in the art of tanka capitalized on the inscrutable expressions in these poems and monopolized the field. The prestige of the poetry families was heightened; moreover, the financial rewards were great. For hundreds of years the heirs of these families were initiated into the well-guarded techniques of the art. As a matter of course, poets and their poems were conservative in the extreme.

In 1871 what later became the Imperial Poetry Bureau was established under the Ministry of the Imperial Household, the commissioners of the bureau descendants of these very court poets and their disciples. The commissioners were rigid formalists absorbed in preserving tradition yet deficient in creative energy. Until the end of the second decade of the Meiji era (1868-1912), poets were completely dominated by the Poetry Bureau School, or, as it was later called, the Old School. The poets of the Old School were removed from the dynamic life of Meiji as it experienced the impact of Westernization. Their poems, deficient in real feeling, were concerned only with the beauty of nature. Suddenly aware of the rapidly progressing materialism of the new age, the Old School began to feel something of its impact and tried to adapt their art to the new era. But inadequate in talent and sensibility, they were unable to keep pace with the times, even though they introduced into tanka the telegraph and the railroad. Their newness never went beyond mere subject matter.

This stirred Japan's younger poets and students of Japanese literature to rescue the tanka through innovation. Yoshiyuki Hagino, in his 1887 essay "The Reform of Tanka," suggested its diction be modernized, its style be given greater freedom, its subject matter be made more masculine.

In February 1893, Naobumi Ochiai, a noted poet and scholar, founded the Asaka-sha (The Brotherhood of Asaka), named after the district in Tokyo. Ochiai and his collaborators, among them Tekkan Yosano, were against the Old School and were tanka-reformists. Tekkan advocated a more "manly" poetry, his proclamation causing an enthusiastic response, since it was the eve of the Sino-Japanese War and his words were markedly nationalistic. He maintained that a nation's prosperity was directly linked to its literature and that effeminate tanka was harmful to Japan, launching the soon-to-be-famous magazine Myojo. One of his disciples would be Akiko Yosano (his future wife) - it was Akiko herself who would actually establish the new style of tanka.

Akiko was the third daughter of Soshichi Ho, owner of a famous confectionary shop used by the Imperial household. The name Ho ("Phoenix" in Chinese) suggests that a remote ancestor, probably a Chinese artisan, had settled in Japan, though the famous poet and author Haruo Sato rejects this possibility. Akiko's father registered her name as Sho, merely a Chinese character, but to make the name more feminine, Akiko later added to it the suffix "ko." Since the character "Sho" can also be pronounced "Aki" in Japanese, her pen name became Akiko.

The once prosperous port of Sakai, where Akiko was from, had earlier produced many rich merchants of aristocratic taste, not the least of whom was the famous tea ceremony master Rikyu. True to local tradition, Akiko's father was more interested in art than business. At the same time he was very much concerned about the upbringing of his eight surviving children. Akiko was born two months after a boy in the family had died in an accident. Her father had believed the new child would be a male. When he discovered its sex, he was quite angry, and instead of the usual celebration seven days after the birth of a child, he left home and remained at an inn for several days. His disappointment turned into a hatred for the infant. In order to appease her husband and mother-in-law, Akiko's mother asked her younger sister to bring up the child; consequently, Akiko was raised by her aunt for three years. Akiko's mother was forced to visit her daughter only at night to escape detection by her husband and mother-in-law. When a third son was eventually born, Akiko's mother felt justified in bringing Akiko back home. At first her father disliked her, but she was so bright that he gradually became fond of her. Later his admiration increased, and recognizing her literary talents, he gave her the highest education possible for a woman in that district.

Akiko graduated high school in 1892 and had gone as far as a woman could go in terms of her education. But she still had to run her father's shop after her elder brother left Tokyo to study science. Her father had little interest in business, and her mother was in delicate health. Until she left home, Akiko was the main support of her family. It was doubly frustrating for Akiko, educated as she had been, to undergo the restraints imposed by her domineering father. A strict believer in feudalistic morality, he refused to allow her out alone even during the day, a member of the family or a servant always accompanying her. At night she was locked in her bedroom, a practice established among the rich in Sakai to ensure her virginity. Her father also tended to ignore his daughter in partiality to his sons. Later she was to give vent to her feelings in the bold unconventional tanka of Midaregami (Tangled Hair).

The word Midaregami (tangled or disheveled hair) does not imply a slovenly or unaesthetic appearance in this context. Today, when the Japanese are favoring more direct expression, evocative values of earlier terminology are lost to the younger generation. In the days before World War I, the image of a woman with even slightly disordered hair had an erotic association. H.H. Honda, in his small volume entitled The Poetry of Yosano Akiko, translates Midaregami as "Hair in Sweet Disorder."

In those earlier days Japanese women took pride in long, black, straight hair. No woman thought of cutting or curling her hair. Women born with curly hair took great pains to straighten it with steamed towels and hair irons. It was also considered a disgrace for a woman to let others see her hair disheveled, it being part of female virtue to have meticulously neat hair. Women with disheveled hair were considered loose and immoral. Still, in those pre-Taisho days, a few stray hairs or hair in slight disarray evinced an erotic resonance. Many examples of midaregami were depicted in woodprints. But Akiko raised midaregami to a further level, equating it with the emancipation of women and sexual freedom. The implications behind her use of the term, while also embodying the usual associations, braid through them a complex pattern of great beauty, sexuality, and even psychological disturbance or madness. While other authors were moving away from romanticism and more towards naturalism, Akiko ushered in a new age of romantic love, allowing again for poetry to prosper.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway so i have had to do so much art history research for this tmnt fic b/c 1. the main character is an artist and i have to plausibly narrate about the artistic process and 2. there's a bunch of art history stuff about historical art techniques too

i mean there's a limit to how much research for accuracy i'm willing to do so i'm sure a lot of the details are wrong but w/e it's fine

some of the things i've turned up in this process:

'selected poems from kokin wakashu', with commentary.

from wikipedia:

The Kokin Wakashū (古今和歌集, "Collection of Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times"), commonly abbreviated as Kokinshū (古今集), is an early anthology of the waka form of Japanese poetry, dating from the Heian period. An imperial anthology, it was conceived by Emperor Uda (r. 887–897) and published by order of his son Emperor Daigo (r. 897–930) in about 905. Its finished form dates to c. 920, though according to several historical accounts the last poem was added to the collection in 914.

The compilers of the anthology were four court poets, led by Ki no Tsurayuki and also including Ki no Tomonori (who died before its completion), Ōshikōchi no Mitsune, and Mibu no Tadamine.

[...]

The idea of including old as well as new poems was another important innovation, one which was widely adopted in later works, both in prose and verse. The poems of the Kokinshū were ordered temporally; the love poems, for instance, though written by many different poets across large spans of time, are ordered in such a way that the reader may understand them to depict the progression and fluctuations of a courtly love-affair. This association of one poem to the next marks this anthology as the ancestor of the renga and haikai traditions.

some of the commentary i particularly enjoyed:

よみ人しらず

題しらず

梅花たちよるばかりありしより人のとがむるかにぞしみぬる

ume no hana

tachiyoru bakari

arishi yori

hito no togamuru

ka ni zo shiminuru

Anonymous

Topic unknown

I lingered only a moment

beneath the apricot blossoms

And now I am

blamed for my

scented sleeves

In the context of its presumed source, the personal collection of Fujiwara no Kanesuke (d. 933), this is a love poem sent to a woman facetiously complaining that incense, redolent of apricot (or plum) blossoms, burnt to scent her robes, has infused his own, and that their relationship has thus been discovered by members of his household. That his complaint is facetious is attested by the evidence that he sent this poem to the woman (who knows better) by way of stating his intention not to be dissuaded. The editors of Kokinshu signal their intentions to reread this as a poem on "plum blossoms," not love, by placing it as an anonymous poem obliquely praising the seductive depth of the scent of the blossoms, in support of the poet's claim to have lingered only briefly.

and also

題しらず

ほのぼのと明石の浦の朝霧に島がくれ行く舟をしぞ思ふ

このうたは、ある人のいはく、柿本人麿が哥也

honobono to

akashi no ura no

asagiri ni

shimagakure yuku

fune wo shi zo omou

Anonymous

Topic unknown

Into the mist, glowing with dawn

across the Bay of Akashi

a boat carries my thoughts

into hiding

islands beyond

Some say that this poem was composed by Kakinomoto no Hitomaro.

Passage into Akashi Bay meant crossing the official gateway at Settsu from the Inner to the Outer Provinces, and the implied topic is border-crossing. This is one of the most often quoted and allegorically glossed poems of Kokinshu, and became one of a core of poems treated as having profoundly esoteric meanings within the "Secret Teachings of Kokinshu." Its reputation was enhanced, certainly, by the attribution to Hitomaro, venerated as one of the deities of the Way of Poetry. One Nijo School commentary suggests that the poem, generally taken as an allegory of the death of Prince Takechi, was deliberately placed by the editors in the book of travel rather than in that of mourning to free it from taboos attaching to poems of mourning.

just like, oh yeah the thing with history and with art is that they're enormously context-heavy; all of these poems were written in a certain artistic tradition, and the editors who rearranged and placed them in dialog with each other are synthesizing new interpretations of them. or just making categorization jokes.

the other thing i saw and really liked is this series of ukiyo-e prints called 'Tokaido 53 stations'. (as wikipedia says: a series of ukiyo-e woodcut prints created by Utagawa Hiroshige after his first travel along the Tōkaidō in 1832)

so the tokaido was one five 'great roads', the most important one (it linked edo and kyoto, so, yeah pretty important) and the artist traveled on it as part of some kind of ceremonial horse-gift delegation from the shogun to the emperor. that's a situation with whole other context that i don't know. anyway there were stations on the roar, you know, official inns and the like, and he ended up making a print for each station. (there's some debate over whether he actually saw each station since some of the prints are inaccurate or derivative of other illustrations & who can say to what degree that's just taking artistic liberty. one of the prints depicts a wintertime scene with snow and it's like, wait it doesn't actually snow at that location. maybe he just wanted to depict all four seasons and picked that station.)

i really liked the one of hakone and that got me to start looking where i could get a print of the thing. you can obviously go to like, art.com or walmart, or w/e and they're like oooh look you can get a premium giclée print of this!! a giclée print is just like a fancy inkjet printer, which i guess makes a certain amount of sense for prints of paintings, but these are woodblock prints. they're literally designed to be mass-produced! there's not really an 'original' of any of these, unless you consider 'first printing with original woodblocks' to be the 'originals', and all further printings to be 'reproductions'

so i went looking for anybody who was actually doing woodblock prints of these things in the modern day. that lead me to UNSODO: "UNSODO is the only publishing company in Japan that publishes woodblock prints." i don't know if that's really true or accurate but it's on their website.

they do have a bunch of HIROSHIGE prints on their store (which you might note is not an e-store; you have to email them your order information and they'll get back to you) they're ~13000 yen which is a vast difference from the $50 prints you can get at art.com but uhh these would be actual replications of the method of production, not just a laserjet given a big png of the print. you can also buy them via kyoto handcraft center for a like 90% markup for the convenience of a automated e-store, which seems like not a great deal imo.

anyway all of that definitely had me thinking about art and artistic production and replication and the ways art is both immortal and ephemeral. something something walter benjamin the work of art in its age of technological reproducability.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A postcard published 1918-1933 featuring a colored photograph of a descendant of the plum tree said to have inspired a poem by Ki no Tsurayuki (紀貫之) (872-945) on the grounds of Hasedera Temple (長谷寺) in present-day Sakurai, Nara Prefecture:

人はいさ

心も知らず

ふるさとは

花ぞむかしの

香に匂ひける

With people, well,

you can never know their hearts;

but in my old village

the flowers brightly bloom with

the scent of the days of old

Image from the collection of the Nara Prefectural Library (see source)

Translation from “Pictures of the Heart: The Hyakunin Isshu in Word and Image” by Joshua S. Mostow, University of Hawai’i Press. 1996, page 246

#buddhist temple#奈良県#nara prefecture#桜井市#sakurai#長谷寺#hasedera#西国三十三所#plum tree#japanese literature#japanese poetry#japanese poem#紀貫之#ki no tsurayuki#和歌#waka#古今和歌集#kokin wakashu#古今集#kokinshu#百人一首#hyakunin isshu#小倉百人一首#ogura hyakunin isshu#postcard#ephemera#printed ephemera#paper ephemera

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

- Kokinshū, Book XI: Love

#yearning#longing#pining#classic literature#dark academia#kokinshū#light academia#Japanese literature#Japanese poetry#japan#heian period#heian poetry#kokinshu

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

JOMP Book Photo Challenge

20: Hello Spring!

I love traditional Japanese court poetry and the symbolism of the different seasons, especially in relation to romance.

#jompbpc#justonemorepage#hello spring#kokinshu#poetry#book photo challenge#book pages#japanese literature#mine

23 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Is the world a sadder place than it once was?

And has the change been wrought by me alone?

Anonymous, Kokinshu 948

#tale of genji#kokinshu#kokinshu 948#thought#deep thought#melancholy#sadness#literature#quote#Japanese literature#japan#poetry#japanese poetry#poem#book quote#book

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I thought to see whether I could do without you.

I cannot tell of the longing, even in jest.

Anonymous, Kokinshû 1025

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Enshrouded in mists

trees come into bud,

for spring snow falls,

flowers scatter even in villages

where no flower yet blooms.

Ki no Tsurayuki 紀貫之 (866 or 872–945?)

Kokinshū 古今集 (Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern; 905): poem 9, composed on snow falling.

Translated by the blog author.

霞たち 木の芽もはるの 雪降れば 花なき里も 花ぞ散りける Kasumi tachi / ki no me mo haru no / yuki fureba / hana naki sato mo / hana zo chirikeru

UPDATE (March 23, '21): see the link in the notes below for my Hyakunin Isshu poem-analysis-like write-up on this poem. ❄️🌸🙂

#world poetry day#Ki no Tsurayuki#紀貫之#Japanese poetry#waka poetry#waka#和歌#poetry in translation#Classical Japanese literature#Japanese literature#Kokinshu#古今集

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kokin Wakashū 古今和 歌集

ou Kokinshū 古今集 - 1ère Anthologie de waka 和歌.

VOYAGES / Livre 9

Ono no Takamura par Kikuchi Yōsai 菊池容斎 (1781 - 1878).

Poème 407 de Ono no Takamura 小野篁 ou Sangi no Takamura 参議篁 (802-853) - savant et poète.

わたの原 「和田の原」 / 八十島かけて / こぎ出ぬと / 人には告げよ / あまのつり舟

Wata no hara / Yasoshima kakete / Kogi idenu to / Hito ni wa tsugeyo / Ama no tsuri bune

Illustration du poème 407 : Ono no Takamura (Sangi Takamura) de Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760 - 1849).

Vers les octante îles

de la vaste plaine marine

je m'en vais voguant

va-t'en le lui annoncer

ô la barque du pêcheur

Traduction : René Sieffert

Illustration du poème 407 de Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1797-1861).

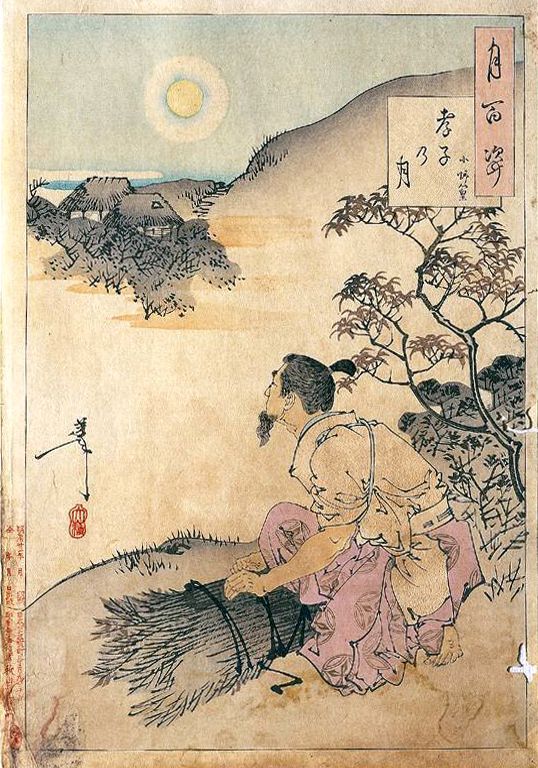

Ce poème, dans le Kokinshū 古今集, est présenté comme suit : "Alors qu'il avait été exilé dans la province d'Oki-no-kuni 隠岐国, envoyé chez quelqu'un qui demeurait en la ville pour lui annoncer qu'il s'embarquait". Les "huit fois dix îles" est une des multiples façons de désigner l'archipel. Les nombres huit, quatre-vingt, huit cent, huit mille, huit myriades ou huit cent mille s'appliquent à des choses ou des êtres trop nombreux pour être comptés, ou, à la limite, en nombre indéfini, tels les kami 神, les dieux shintō 神道 qui sont ya.o.yorozu 八百万, "huit cents myriades" . Bien que bon nombre d'anecdotes rapportent des traits d'esprit de Takamura, douze seulement de ses poèmes figurent dans les chokusen-shū 勅撰集 . Kokin Wakashū 古今和 歌集 ou Kokinshū 古今集 , IX, 407. "De 100 poètes un poème" René Sieffert.

Histoire : Ono no Takamura a été haut fonctionnaire à la cour de l'empereur Saga tennō (52) 嵯峨天皇 (786 - 842 r. 809 - 823) au IXe siècle. Lettré célèbre, en particulier pour ses compositions en chinois, avait été, en 829, adjoint à Fujiwara no Tsunetsugu 藤原常嗣 (796-840), chef de l'ambassade qui devait se rendre en Chine ; comme il s'était dérobé en se prétendant malade, on l'avait exilé dans l'archipel d'Oki-shotō 隠岐諸島. Rentré en grâce, il devint par la suite Conseiller du troisième rang de Cour.

Six de ses waka ont été inclus dans l'anthologie impériale Kokin Wakashū 古今和 歌集 ou Kokinshū 古今集 et l'un de ses poèmes a été inclus dans l'Ogura Hyakunin Isshu 小倉百人一首 (11).

Légende : Takamura a également souvent été loué comme modèle de piété filiale et de générosité. Il partageait ses allocations avec des parents et des amis qui étaient plus dans le besoin que lui et montrait un grand respect pour ses parents. L'iconographie pourrait également faire référence à Ceng Shen, un disciple important de Confucius, à qui est attribuée la compilation des 24 parangons de la piété filiale. La légende raconte que Ceng cueillait des broussailles dans la forêt quand il eut la prémonition que sa mère avait besoin de lui. Il se dépêcha de rentrer chez lui pour constater qu'elle lui avait tellement manqué qu'elle s'était mordue le doigt avec contrariété.

Illustration : "100 aspects of the moon - Moon of the filial son (Koshi no tsuki) de Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (1839 - 1892)

#poem#poetry#japan#kokin wakashu#kokinshu#waka#tanka#heian jidai#ono no takamura#kikuchi yosai#katsushika hokusai#utagawa kuniyosehi#tsukioka yoshitoshi#anthologie de poésie#poème#japon

393 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If only I could creep

into each corner

of the heart of the one

who says she loves me

and keep watch.

1038, anonymous in the Kokinshuu (Collections of Ancient and Modern Poetry, ca. 905)

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Imperial Anthology, Kokinshu 花鳥下絵和歌巻 (part 4 of 4)

Type: Handscroll

Artist: Tawaraya Sōtatsu 俵屋宗達 (fl. ca. 1600-1643)

Calligrapher: Hon'ami Kōetsu 本阿弥光悦 (1558-1637)

Historical period: Momoyama period, early 1600s

Medium: ink, gold, silver, and mica on paper

Geography: Japan

Freer Gallery of Art

80 notes

·

View notes