#icelandic rune poem

Text

The Runes of Hávamál

As I am working my way through the Aett’s and prepare for a talk on the use of Runes in divination and magic I’ve extended my research to examples of bind runes and staves in the textual record. My (unoriginal) idea was to see if texts such as the Hávamál referred to Odin’s acquisition of the Runes in such a way which would lead to the construction of Rune Staves. As ever I am following in the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

List of interesting ressources pertaining to norse paganism, scandinavian folklore and history, and nordic religions in general

These are sources I have personally used in the context of my research, and which I've enjoyed and found useful. Please don’t mind if I missed this or that ressource, as for this post, I focused solely on my own preferences when it comes to research. I may add on to this list via reblog if other interesting sources come to my mind after this has been posted. Good luck on your research! And as always, my question box is open if you have any questions pertaining to my experiences and thoughts on paganism.

Mythology

The Viking Spirit: An Introduction to Norse Mythology and Religion

Dictionnary of Northern Mythology

The Prose and Poetic Eddas (online)

Grottasöngr: The Song of Grotti (online)

The Poetic Edda: Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes

The Wanderer's Hávamál

The Song of Beowulf

Rauðúlfs Þáttr

The Penguin Book of Norse Myths: Gods of the Vikings (Kevin Crossley-Holland's are my favorite retellings)

Myths of the Norsemen From the Eddas and the Sagas (online) A source that's as old as the world, but still very complete and an interesting read.

The Elder Eddas of Saemung Sigfusson

Pocket Hávamál

Myths of the Pagan North: Gods of the Norsemen

Lore of the Vanir: A Brief Overview of the Vanir Gods

Anglo-Saxon and Norse Poems

Gods of the Ancient Northmen

Gods of the Ancient Northmen (online)

Two Icelandic Stories: Hreiðars Þáttr and Orms Þáttr

Two Icelandic Stories: Hreiðars Þáttr and Orms Þáttr (online)

Sagas

Two Sagas of Mythical Heroes: Hervor and Heidrek & Hrólf Kraki and His Champions (compiling the Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks and the Hrólfs saga kraka)

Icelandic Saga Database (website)

The Saga of the Jómsvíkings

The Heimskringla or the Chronicle of the Kings of Norway (online)

Stories and Ballads of the Far Past: Icelandic and Faroese

Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway

The Saga of the Volsungs: With the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok

The Saga of the Volsungs (online) Interesting analysis, but this is another pretty old source.

The Story of the Volsungs (online) Morris and Magnusson translation

The Vinland Sagas

Hákon the Good's Saga (online)

History of religious practices

The Viking Way: Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia

Nordic Religions in the Viking Age

Agricola and Germania Tacitus' account of religion in nordic countries

Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions

Tacitus on Germany (online)

Scandinavia and the Viking Age

Viking Age Iceland

Landnámabók: Book of the Settlement of Iceland (online)

The Age of the Vikings

Gesta Danorum: The Danish History (Books I-IX)

The Sea Wolves: a History of the Vikings

The Viking World

Guta Lag: The Law of the Gotlanders (online)

The Pre-Christian Religions of the North This is a four-volume series I haven't read yet, but that I wish to acquire soon! It's the next research read I have planned.

Old Norse Folklore: Tradition, Innovation, and Performance in Medieval Scandinavia

Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings

The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings by John Haywood

Landnámabók: Viking Settlers and Their Customs in Iceland

Nordic Tales: Folktales from Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland and Denmark For a little literary break from all the serious research! The stories are told in a way that can sometimes get repetitive, but it makes it easier to notice recurring patterns and themes within Scandinavian oral tradition.

Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Short Introduction

Saga Form, Oral Prehistory, and the Icelandic Social Context

An Early Meal: A Viking Age Cookbook and Culinary Oddyssey

Runes & Old Norse language

Uppland region runestones and their translations

Viking Language 1: Learn Old Norse, Runes, and Icelandic Sagas and Viking Language 2: The Old Norse Reader

Catalogue of the Manks Crosses with Runic Inscriptions

Old Norse - Old Icelandic: Concise Introduction to the Language of the Sagas

A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture

Nordic Runes: Understanding, Casting, and Interpreting the Ancient Viking Oracle

YouTube channels

Ocean Keltoi

Arith Härger

Old Halfdan

Jackson Crawford

Wolf the Red

Sigurboði Grétarsson

Grimfrost

(Reminder! The channel "The Wisdom of Odin", aka Jacob Toddson, is a known supporter of pseudo scientific theories and of the AFA, a folkist and white-supremacist organization, and he's been known to hold cult-like, dangerous rituals, as well as to use his UPG as truth and to ask for his followers to provide money for his building some kind of "real life viking hall", as supposedly asked to him by Óðinn himself. A source to avoid. But more on that here.)

Websites

The Troth

Norse Mythology for Smart People

Voluspa.org

Icelandic Saga Database

Skaldic Project

Life in Norway This is more of a tourist's ressources, but I find they publish loads of fascinating articles pertaining to Norway's history and its traditions.

#ressources#masterpost#heathenry#research#sources#norse paganism#norse gods#spirituality#polytheism#deity work#pagan#paganism#deities#norse polytheism#mythology#eddas#sagas

589 notes

·

View notes

Note

what books would you recommend for baby heathens. any recommendations for runestones?

My personal recommendations would be:

A Traveller's Guide to Modern Heathenry: An Introduction, published by Asatru UK and Pantheon: The Norse by Morgan Daimler, as well as Norse Mythology: A Guide To The Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs by John Lindow and Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend by Andy Orchard (they're easier to consume than Simek's Dictionary of Northern Mythology).

As for books about runes, it's largely going to depend on what you're after. I haven't read it myself so I can't say for certain how good it is but Asatru UK published The Traveller's Book on Runes as part of their Traveller's Collection. I'd also recommend Runes: A Handbook by M. P. Barnes, and An Introduction to English Runes by R. I. Page.

The site, Að Falla í Stafi, has a recommended list of rune books as well that is worth checking out:

https://fallaistafi.altervista.org/reading-list/

@drekisdottir has a decent bibliography on their rune site as well, so you should be able to find some decent rune related books there as well:

https://runesoftheoerp.wordpress.com/sources-for-this-website/#bibliography

The Old English, Icelandic and Norwegian Rune Poems are always worth a read as well.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germanic Paganism Sources

I can’t list these sources without first going through a million different caveats. I’m going to keep this introduction brief due to the length of this post, but be aware that these sources have been subjected to Christianization, speculation, mistranslation, etc. Many of these sources were copied down by Christian authors who may have altered the truth in order to fit their perspective. Some may have vague terms or phrases that we can no longer understand because they existed in an entirely new context. Essentially, approach all of these texts from a speculative and critical lens. This doesn’t mean we can’t decipher the truth. We can decipher the truth by comparing texts from the same time, countries, etc with each other and finding the common threads. Pairing these attestations with archaeological records is also immensely helpful and I hope to compile a list of archaeological records some time in the future. You can find many free records and studies by simply typing, for example, “anglo-saxon burials archaeological excavations.”

This list consists of records of various Germanic peoples, histories, as well as semi-legendary sagas and poetry. By exploring a variety of texts instead of just ethnographic works, we can understand the history, culture, customs, traditions, values, and more. These are all crucial in approaching paganism with the goal of accurate and thorough understanding. I wanted to focus primarily on sources from close to the pagan period, but I have also included current sources in the grimoires and runes section. For the contemporary study of Germanic paganism, I always recommend Stephen Flowers!

Happy researching

The Eddas

https://www.norron-mytologi.info/diverse/ThorpeThePoeticEdda.pdf

http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/EDDArestr.pdf

England

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657-images.html

https://ia804700.us.archive.org/31/items/exeterbookanthol00goll/exeterbookanthol00goll.pdf

https://langeslag.uni-goettingen.de/oddities/texts/Aecerbot.pdf

https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/0627-0735,_Beda_Venerabilis,_Ecclesiastical_History_Of_England,_EN.pdf

https://www.ragweedforge.com/rpae.html (this website also has the norwegian and icelandic rune poems)

https://www.dvusd.org/cms/lib/AZ01901092/Centricity/Domain/2897/beowulf_heaney.pdf

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/ascp/

https://ia601403.us.archive.org/12/items/bede-the-reckoning-of-time-2012/Bede%20-%20The%20Reckoning%20of%20Time%20%282012%29.pdf

Germany

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/nblng/index.htm

https://www.germanicmythology.com/works/merseburgcharms.html

Frisia

https://www.liturgies.net/saints/willibrord/alcuin.htm

Denmark

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/saxo/index.htm

Iceland

https://archive.org/details/booksettlementi00ellwgoog/page/n4/mode/2up

Finland

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/kveng/kvrune01.htm

Germania

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7524/7524-h/7524-h.htm

The Sagas

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/598/598-h/598-h.htm

http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Heimskringla%20II.pdf

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/heim/05hakon.htm

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/vlsng/index.htm

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/egil/index.htm

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/ice/is3/index.htm

https://sagadb.org/files/pdf/eyrbyggja_saga.en.pdf

https://sagadb.org/brennu-njals_saga.en

Grimoires

https://archive.org/details/GaldrabokAnIcelandicGrimoire1

https://handrit.is/manuscript/view/is/IB04-0383/9#page/3v/mode/2up

https://galdrastafir.com/#vegvisir

Runes

https://www.esonet.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Futhark-A-Handbook-of-Rune-Magic-Edred-Thorsson-1984.pdf

*Due to link limits on tumblr, i cannot link all of these. Please paste them into your browser.

*Also, sadly I could not find some of the sources I wanted for free. I will continue to update this post with new links and it will be pinned to my profile always!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

My new tattoo that I got before leaving my hometown. Old Icelandic (and Norway) poems about Týr and his rune Tiwaz that I condensed into those lines.

"Týr er einhendr áss oc ulfs Leinart oc hofa hilmir. Týr er Baldurs broðir, leidestjerna, wic han aldri."

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

In Norse beliefs, what does the snake symbolise? (Not Jormungand)

I can see why someone would think there would be a straightforward answer to this, but there really isn't. With how often snakes and dragons and stuff are depicted in Norse art they probably conveyed some kind of meaning that was understandable to others at the time, but we can only make guesses. Snakes occur in the literature a lot, but usually the meaning of their appearance is "there was a snake there." While they do seem to sometimes indicate other meanings as well, it isn't consistent through the literature and you have to examine how it's being done in context each time.

Old Icelandic literature mostly only talks about venomous snakes, so there is a constant underlying assumption that if a snake is mentioned, it's dangerous. Swedish folk tradition (it seems also Norwegian, but less well-attested as far as I can tell) also has strongly positive associations with non-venomous snakes, but I'll cover literary depictions in Old Icelandic first and briefly describe folk tradition at the end.

The most archetypal snake isn't Jörmungandr, but Fáfnir. Jörmungandr is usually just Jörmungandr and nothing else; Fáfnir is much more likely to be invoked when there's, like, a regular snake, or some gold, or something else that isn't actually Fáfnir. To be clear, we don't know that he was always pictured as a "snake" and not a "dragon" or something else. The word ormr means everything from an earthworm up to the dragon that killed Beowulf (Old English wyrm). There are other words they could use to specify (höggormr 'adder; poisonous snake,' snákr 'snake'; naðra 'adder, viper') but the latter two are used mostly in poetry, and since Norse literature rarely talks about non-poisonous snakes, there's little need to distinguish ormr from höggormr in this context. Fáfnir is symbolically polyvalent -- he can just as easily be made to stand for greed (for the Rheingold) as for knowledge/wisdom (extracted from him by Sigurðr in Fáfnismál; and eating his heart gives Sigurðr further knowledge, specifically the ability to understand the speech of birds).

Óðinn transforms into a snake in the process of stealing/reclaiming the mead of poetry. It doesn't seem a stretch to say that Norse people might have associated serpents with knowledge not normally accessible to humans, and which might be risky to acquire, such as that also associated in the myths with waking the dead in order to question them. But I'm not seeing enough that we can dispense with the "might" in that sentence.

Elsewhere in Norse literature, such as the rune poems, kennings refer to gold as "bed" or "path" of "a serpent." It can be hard to tell whether there was a widespread understanding of snakes resting on gold (maybe referring to them being subterranean?) or whether they're using poetic language to invoke Fáfnir and/or gold-hoarding lindworms (such as the one slain by Ragnarr loðbrók, whence his name loðbrók, taken from the shaggy pants he wore to protect him from the serpent's bite). Either way, because Nordic poetic language allows interchange between members of a category, any snake you see in the woods can be referred to through reference to Fenrir, and they other way around, so that serpents and gold are always connected in poetic language.

The presence of ormar can indicate decay; it can be hard to tell whether the authors in these cases are talking about snakes or worms, or maybe it's both. They frequently appear in this context together with frogs, lizards, and maggots. They're used in this way in Ólafs saga helga to imply a relationship between paganism and darkness/infestation when an idol is broken and found to be full of vermin. It might be relevant that the serpent was used as a symbol of the devil in medieval Christianity; in this way we can compare it to Ögmundar þáttr dytts in which an idol of Freyr is smashed and onlookers see an actual demon leave it. The Ólafs saga helga example is probably the most straightforward use of a snake to symbolize something else that I found.

In Völsunga saga, Guttormr (etymologically, his name probably isn't gutt-ormr '(something)-serpent,' but since the etymology was likely opaque to Norse-speakers they may have thought it was; Ormr is a not-uncommon male personal name) is fed snake and wolf meat, seemingly to make him acquire attributes of snakes and wolves in order to prepare him to murder Sigurðr. In Völsunga saga, Gunnarr is executed by snake pit. After living for 300 years, Örvar-Oddr is finally killed by a snake (fulfilling a prophecy). So we can easily propose an association of snakes with death, characterizations of snakes based on their deadly bite; though we can't quite call any of this symbolic because you can't ever write the actual snake out of the meaning of its own appearance.

Trolls have poisonous snakes as the reigns for their horses (which are wolves). Snakes are the "[fish] of the [land]" (where [fish] and [land] can be substituted by any specific example of a fish or land-based geographical feature, e.g. "cod of the mountain" or "herring of the field." There is a sword in Egils saga called naðr 'adder' and skaldic language refers to swords as things like 'snake of battle.'

Probably not very relevant, because it's a single isolated attestation referring to a single, specific snake, in a translated saint's saga, but in Barlaams saga ok Jósafats (the Old Icelandic translation of the Christianized version of the story of the Buddha), someone is compared to "that serpent which is called asp" because (according to the saga) they close their ears rather than listen to something they don't want to hear. i.e., the person doesn't listen to or heed things that they don't personally like.

The story of the Red and White dragons symbolizing the Welsh and the Saxons that appears in British history was known to Norse-speakers and is part of Merlínuspá.

You would think that there would be some textual discussion of serpents used in art given its frequency, but I have found only one example, in Þiðreks saga of Bern, where a highly decorative horse saddle is described as having been made with elephant bone and inscribed with an image of a naðra ('adder'). It's disappointing how little contemporary discussion of art there is in general.

We should probably mention Níðhöggr. He's described with both the words dreki 'dragon' and naðr 'adder' in Völuspá; this demonstrates the semantic bleed between words in Old Norse that isn't replicated by the words we're using in English. Apparently he can fly, so we'd more likely call him a dragon than a snake. But since dragons and snakes don't have a hard contrast in ON, we can still learn about snakes from observing this dragon. But we've already established most of the important stuff -- he's (mostly) subterranean, he's probably poisonous, he strikes (höggva), he is indicative of decay.

I am almost undoubtedly missing something important or interesting. I don't have a way to research this other than to put whatever words for 'snake' I can think of into the Dictionary of Old Norse Prose and skim the results. To save time I mostly skipped over translations of Biblical material but that might be a mistake, but seeing as I am not trying to do a whole research project on this, that's the best you're getting from me.

It's worth mentioning that Scandinavia is not exactly known for being full of poisonous snakes. They do have the European adder, and maybe there were more species during the Medieval warm period, I don't know. But a lot of the serpents mentioned in Norse mythology are geographically located far away. Völsunga saga where a lot of serpent-based lore comes from takes place in a sort of general "far away" southern Europe (traditionally, around Worms, Germany). Iceland doesn't have any snakes, so their danger may have been exaggerated in the minds of authors and audience of the texts we're looking at.

From medieval times into modern times, and definitely extending back before our earliest evidence for it, snakes had a very different characterization in Sweden. Non-poisonous snakes (especially grass snakes) were cared for, given offerings of milk, and treated like members of the family. They are called tomtormar ('tomte-snakes'?), husormar ('house-snakes'), or gårdsormar ('yard/farmstead-snakes') and the tradition seems to overlap heavily with recognition of the tomte or nisse. They brought good luck, and killing the house snake would bring grave misfortune. As far as I know, the first attestation of this is as early as St. Birgitta's account of the peoples of the Swedish countryside from the 1300's. Interpretations of this seem to vary widely, with some people arguing that it's a remnant of a pre-Christian snake cult and others arguing that the Christians who documented it exaggerated the practice and especially its religious connotations. Extremely similar practices are observed all around the Baltic; in Of Gods and Men, Algirdas Greimas wrote a bit about what he himself called the "snake cult" in Lithuania with its major holiday on January 25, which corresponds to old Midwinter (more or less the same way it does on an Icelandic calendar, where Midwinter can fall on any day from Jan 19 to 25). You can read more about tomtormar on Swedish Wikipedia; if you use Google Translate be aware that it has trouble with some folklore words like "tomten" (might translate to "Santa Claus") so keep an eye on the left side of the screen as well.

As with much of what I've talked about here, this isn't an example of symbolism. It certainly creates a potential for it, but we're still missing that important link between a body of associations or meanings and them being invoked through a symbolic usage of a snake. The snakes here don't symbolize good fortune any more than your mail carrier symbolizes the mail.

So to summarize, we have few instances of snakes that are both clearly symbolic and interperable, but we do have an idea of what Norse people thought about snakes. They lay on gold, and so are a potent symbol for greed -- Fáfnir has enough personal history for us to characterize him individually by his personal greed. They have access to the underground and probably to knowledge not accessible to humans; but they are also fierce, deadly creatures and it could be dangerous to gain that knowledge; yet there are some that are not dangerous and still have access to the world outside the human sphere. It might also have been considered possible to take on aspects of a venomous snake's nature the same way that a human could acquire traits of wolves, bears, boars, etc. Meanwhile, Christian symbolic usage of snakes was already well-developed by the time it came to Scandinavia; they represented demonic forces and this symbolism was well-positioned to induct heathenry into it and to frame it as also demonic. I'm sure there's more, but that's what I've got for now.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The idiom “let the chips fall where they may” is said to have originated with American wood choppers in the 1800s — the idea being that woodcutters had to focus on larger logs and not worry about the small pieces (“chips”) as they fell. A version of “don’t sweat the small stuff”, if you will.

HOWEVER, an Icelandic poem from 1225 CE uses the same expression referencing a type of rune casting — i.e. throwing marked chips in the air, seeing how they land and using the placement to divine how best to proceed. In this instance the expression “let the chips fall where they may” meant more along the lines of “whatever will be, will be.”

I’d bet the idiom survived long enough to be completely divorced from the original practice of rune casting that humans forgot and unknowingly came up for a new origin story for the idiom — as though the generations in between were unwittingly playing an ancient version of the telephone game.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

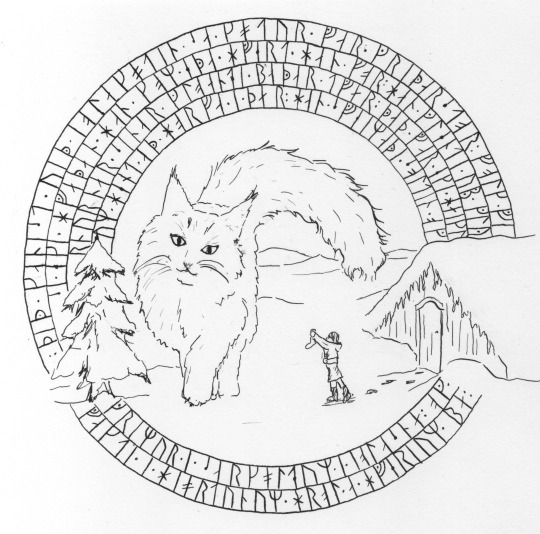

Runetober Day 12: Cat

(following the woodland magic prompts by smalltownspells)

The Yulecat is a modern Icelandic folklore figure. It is said to prey on those who did not receive a new item of clothing by Christmas day. This was probably used by farmers as an incentive for their farmhands to help with processing the wool for the year. In my picture, a child is proudly showing their new socks to the cat.

The Cat was especially made famous through a poem by Jóhannes úr Kötlum, which many might know better through the song version by Björk.

The runes I used are late medieval runes reflecting the modern Icelandic text. I used 3 stanzas from the poem:

You know the Yule-cat

that cat is very large

Folks don't know where he came from

nor where he has gone.

He opened his eyes widely

both of them are glowing

it was not for cowards

to look into them

He walked about, hungry and grim

in painfully cold yule snow

and kindled the hearts with fear

in every town

In Icelandic:

Þið kannist við jólaköttinn,

– sá köttur var gríðarstór.

Fólk vissi ekki hvaðan hann kom

eða hvert hann fór.

Hann glennti upp glyrnurnar sínar,

glóandi báðar tvær.

– Það var ekki heiglum hent

að horfa í þær.

Hann sveimaði, soltinn og grimmur,

í sárköldum jólasnæ,

og vakti í hjörtunum hroll

á hverjum bæ.

In runes:

:ᚦᛁᚧ·ᚴᛆᚿᛁᛍᛐ·ᚡᛁᚧ·ᛁᚮᛚᛆᚴᚯᛐᛁᚿ·ᛍᛆ·ᚴᚯᛐᚢᚱ·ᚡᛆᚱ·ᚵᚱᛁᚧᛆᚱᛍᛐᚮᚱ:ᚠᚮᛚᚴ·ᚡᛁᛍᛁ·ᚽᚴᛁ·ᚼᚡᛆᚧᛆᚿ·ᚼᛆᚿ·ᚴᚮᛘ·ᚽᚧᛆ·ᚼᚡᚽᚱᛐ·ᚼᛆᚿ·ᚠᚮᚱ:ᚼᛆᚿ·ᚵᛚᚽᚿᛐᛁ·ᚢᛔ·ᚵᛚᚤᚱᚿᚢᚱᚿᛆᚱ·ᛍᛁᚿᛆᚱ·ᚵᛚᚮᛆᚿᛑᛁ·ᛒᛆᚧᛆᚱ·ᛐᚡᛅᚱ:ᚦᛆᚧ·ᚡᛆᚱ·ᚽᚴᛁ·ᚼᚽᛁᚵᛚᚢᛘ·ᚼᚽᚿᛐ·ᛆᚧ·ᚼᚮᚱᚠᛆ·ᛁ·ᚦᛅᚱ:ᚼᛆᚿ·ᛍᚡᚽᛁᛘᛆᚧᛁ·ᛍᚮᛚᛐᛁᚿ·ᚮᚵ·ᚵᚱᛁᛘᚢᚱ·ᛁ·ᛍᛆᚱᚴᚯᛚᛑᚢᛘ·ᛁᚮᛚᛆᛍᚿᛅ:ᚮᚵ·ᚡᛆᚴᛐᛁ·ᛁ·ᚼᛁᚯᚱᛐᚢᚿᚢᛘ·ᚼᚱᚮᛚ·ᛆ·ᚼᚡᚽᚱᛁᚢᛘ·ᛒᛅ:

#mine#my art#runetober#drawtober#inktober#yule cat#christmas cat#jólaköttur#icelandic#runes#smalltownspells

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Runic Divination: A Modern Invention

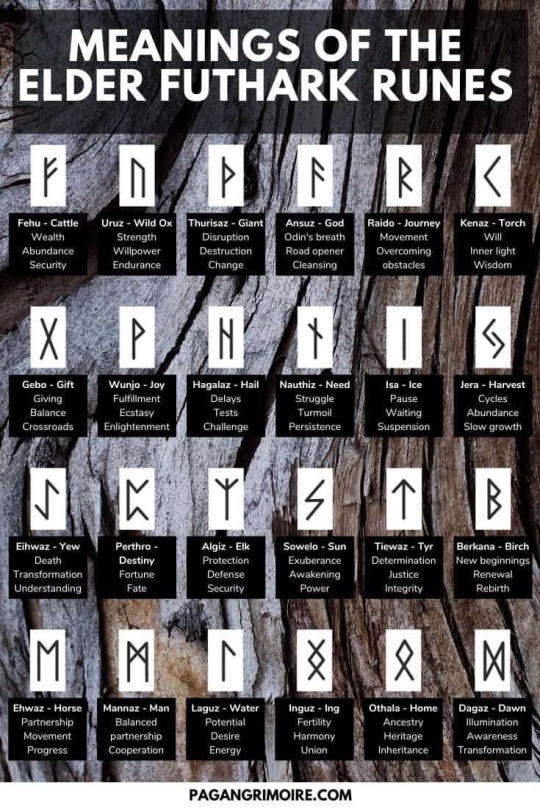

It is a popular belief (especially in certain Neo-Pagan and Heathen circles linked to Neo-Nazism and White Supremacy) that the runes of Elder Futhark:

Were the runes primarily used by the Vikings and represent a direct link to Viking ancestors

Have been used for divination for over a thousand years, representing a long and unbroken tradition, and that the way we use them now is the way the Norse used them in antiquity

Have ancient esoteric meanings that have remained unchanged through the passage of time

Unfortunately, none of these statements are true.

Around 98 AD, a Roman known as Publius Cornelius Tacitus wrote what was essentially an ethnological study of Germanic peoples entitled Germania. In Chapter X, he describes a system of divination used by one particular Germanic Tribe, an observation which later became the basis of what we consider today as runecasting and of the contemporary usage of Elder Futhark as an oracle:

"To divination and casting of lots, they pay attention beyond any other people. Their method of casting lots is a simple one: they cut a branch from a fruit-bearing tree and divide it into small pieces which they mark with certain distinctive signs and scatter at random onto a white cloth. Then, the priest of the community if the lots are consulted publicly, or the father of the family if it is done privately, after invoking the gods and with eyes raised to heaven, picks up three pieces, one at a time, and interprets them according to the signs previously marked upon them."

It is important to note that, at this time, the full inventory of the Elder Futhark alphabet was not yet finalized due to the fact that the sound inventory of Proto-Norse was not yet finalized. It wasn't until around 400 AD that all 24 runes can be solidly attested to within the archaelogical record. While it is probable that some letters of Elder Futhark were likely being used at the time Tacitus wrote his Germania, but it is extremely unlikely that the symbols carved upon the wooden tiles were Elder Futhark.

Additionally, there is simply no archaelogical or historical evidence beyond Tacitus' claims suggesting that the Proto-Norse or Norse used runes as a system of divination at all. Certainly the runes were used in magical contexts; there are many examples of runes and bindrunes being used as talismans and sigils inscribed on weapons, shields, jewelry etc. within the archaelogical record, but nothing suggests that these runes were ever used for divination as we know and use it today.

It is also important to note that Elder Futhark was not the alphabet used by the Vikings, as most proponents of runecasting claim; Elder Futhark was in use from the second century to the late 8th century (700s) in Scandinavia, when it was simplified to the Younger Futhark. The Younger Futhark WAS contemporaneous to the Vikings, and roughly corresponds to the Viking Age (793-1066 CE). This disproves the claim that the Elder Futhark is a direct link to Viking Ancestors -- the Vikings were using a different alphabet. It would be more accurate to say that the Elder Futhark runes linked the Vikings to THEIR Norse, Proto-Norse, and Germanic ancestors.

Finally, the meanings associated with the runes of Elder Futhark as we know them today were actually derived in modern times from the Norwegian, Icelandic, and Anglo-Saxon rune poems. None of these poems were written in Elder Futhark. The current theory proposed by modern linguists is that the Rune Poems were mnemonic devices used to help people remember the order, names, and, most importantly, the sounds of each letter of the alphabet. In other words, the Rune Poems were the equivalent to nursery rhymes.

With this new context, the use of nursery rhymes to assign esoteric meanings or properties to each rune seems a bit odd. Consider how silly it would be if, a thousand years from now, a group of people got a hold of one of those long posters found in elementary school classrooms meant to help children remember the order of the alphabet and decided that not only did the letter A definitively meant 'apple' and B definitively meant 'book', but that we as a society used these letters in order to divine the unknown.

Additionally, if the runes were preserving supposedly ancient meanings, we would expect these meanings to remain consistent throughout time with no variations. However, if the Rune Poems were instead preserving the phonetics associated with each runic letter by linking them to words beginning with that particular sound, we would see variation in the poems due to the linguistic variation of meaning.

And variation in meaning is exactly what we can observe between the Rune Poems; for example, the specific word linked to the phoneme represented in the stanzas attributed to Uruz talk about dross, a by-product of iron smelting within The Norwegian Rune Poem, about rain within The Icelandic Rune Poem, and then finally an aurochs in The Anglo-Saxon poem. The same can be observed for the stanzas attributed to Kenaz: the Norwegian and Icelandic rune poems refer to ulcers (likely derived from the Proto-Germanic *kaunan), while the Anglo Saxon refers to a torch (likely derived from Proto-Germanic *kenaz).

As an aside -- from examining the Rune Poems and comparing them to the commonly used modern meanings attributed to each rune, it is exceedingly obvious that whoever did assign said meanings primarily used The Anglo-Saxon poem as a jumping-off point.

In summary, Elder Futhark runes as we know them do not represent esoteric, magical concepts; the modern day meanings assigned to them were derived from translations of nursery rhymes meant to help people learn the Elder Futhark alphabet and, in some cases, were not the magical meanings ascribed to them by those who originally used them. Elder Futhark was not used by the Vikings and is not a direct link to Viking ancestors as many authors claim. Finally, there is no archaeological or historical evidence to suggest the runes were used for divination, nor was there a long and unbroken tradition of runecasting. The use of Elder Futhark as a tool of divination is a purely modern invention that dates back, at most, to the 1970's. The runes as they are used today are not 'ancient' nor is there a 'tradition' of using the runes for divination spanning back centuries, representative of an 'authentic and 'sacred' and 'holy' practice linked to Vikings.

As far as I can tell, Ralph Blum was the first one to write about the runes as a system of divination. Eddred Thorsson (Otherwise known as Stephen Flowers, who studied Runology, Germanic Languages, and Medieval Studies in an academic context), a known racist and white supremacist strongly linked to 'folkish' beliefs, Odinism, Asatru, and the Neo-Nazi Asatru Folk Assembly (a hate group recognised by the Southern Poverty Law Centre), expanded upon Blum's work and incorporated many Neo-Nazi beliefs based upon volkisch & Nazi doctrine, and is responsible for the perpetuation of these three myths (and quite a few others) into the present day with the publication of his books regarding runes. The publishing rights to Flowers/Thorsson's books are held by the Asatru Folk Assembly. Much of Flowers/Thorrson's assertions regarding the usage of runes is ultimately just unverified personal gnosis unsupported by archaeological or ethnographic evidence.

The association between runes and Nazism is certainly not new. The idea that the Germanic race (and its descendants) was superior to all others was central to Nazi ideology, and German ultranationalists scoured the archaelogical record to find proof of a link to a mythic 'Aryan' Heritage. They particularly liked the Armanen pseudo-Runes (the meanings of which miraculously were revealed to a man named Guido von List in 1902 after suffering temporary blindness following cataract surgery), but ultimately they shifted their attention to the appropriation of the runes of the Elder Futhark. The most infamous rune used by the Nazis is Sowilo, the 's' rune representing the sun, which was renamed the 'Siegrune' (Victory rune) and was used as a symbol for Hitler's Schutzstaffel (ie. The SS). Other runes that were misappropriated include Othala (inheritance) which was used as a symbol for the mantra 'Blud und Boten' (Blood and Soul), and Tiwaz (Tyr), which became a symbol for war and struggle. To claim that the runes represent a long-standing tradition and link to 'the ancestors' is straight up Nazi rhetoric.

This doesn't make the runes any less useful as an oracle! Oracles and divination help us find meaning in our lives as well as help us explain the universe around us, especially when we're faced with the murky unknown or with things that cannot otherwise be explained by other models or paradigms of rationalization. Using the runes to seek out answers to otherwise 'unknowable' questions is actually a method of reframing and recontextualizing our experiences via the viewpoint of an objective outsider, providing new insight and promoting introspection. This is especially helpful if what we 'learn' might not be things we want to hear or think about, especially concerning ourselves. It also helps us elevate the subconscious into the conscious, and makes us aware of things we didn't otherwise give much thought to due to our tunnel-vision view and tendency to focus only on the things we think are important or relevant.

The lesson to be learned from this is that it is important to critically examine so called 'traditions', especially ones claiming to be ancient and representative of 'ancestral' practices -- oftentimes the people perpetuating such beliefs have done so for a reason. Unfortunately, because Flowers/Thorsson's work is so prevalent within the pagan community, and because so many sources regarding runic divination end up linking back to his work, the practice of runecasting and using runes for divination has become tainted with Nazi rhetoric. It is for this reason that I am highly critical of any source listing the 'meanings' of the runes.

So… what can you do about this? Don't buy Flowers/Thorrson's books, obviously. Be critical of all sources when researching runes. Evaluate whether or not this person did their own research, or simply took Flowers/Thorrson's work at face value. Laugh openly at anyone who practices Rune Yoga.

My recommendation to rune enthusiasts is to study the Rune Poems and research the etymology of each rune word and come up with your own meanings and extensions, just like you would when researching the meaning of tarot cards. By doing this, you'll probably also find that you feel even more connected to them than before.

And, above all else, make your space an unsafe space for Nazis.

ᚠᚢᚲ ᚾᚨᛉᛁᛊ

References:

Andersen, Harry. "Three Controversial Runes in the Older Futhark (2)". North-Western Language Evolution, vol. 4, no. 5, 1985, pp. 3-22.

Antonsen, Elmer H. "The Proto-Norse System and the Younger Futhark". Scandinavian Studies, vol. 35, No. 3, 1963, pp. 195-207.

Dickins, Bruce. Runic and Heroic Poems of the Old Teutonic Peoples. Cambridge University, 1915.

Hoppadietz, Ralf, and Reichenbach, Karin. "In Honor of the Forefathers: Archaelogical Reenactment between History Appropriation and an Ideological Mission. The Case of Ulfhednar." Reenactment Case Studies: Global Perspectives on Experiential History, edited by Vanessa Agnew, Sabine Stach, and Juliane Tomann. Routledge, 2023.

Imer, Lisbeth. "How the Nazis abused the history of runes." ScienceNordic. 13 October 2018. Translated by Frederik Appel Olsen. https://sciencenordic.com/denmark-forskerzonen-history/how-the-nazis-abused-the-history-of-runes/1459227. Accessed 28 January 2023.

Knirk, James E. "Runes: Origin, development of the furthark, functions, applications, and methodological considerations." The Nordic Languages, vol. 1, 2002, pp. 634-648.

Southern Poverty Law Center. "Asatru Folk Assembly." SPLC: Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/asatru-folk-assembly. Accessed 28 January 2023.

Southern Poverty Law Center. "Neo-Völkisch." SPLC: Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/neo-volkisch. Accessed 28 January 2023.

Tacitus, Cornelius Publius. Germania. AD 98. Translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb, Macmillan & Co., 1869.

#runes#runecasting#norse paganism#elder futhark#norse#witchcraft#witchblr#vikings#local queer goose here to set the record straight#fuck nazis

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Now that the contest is almost over, I’d like to share my submission to the 2022 DBD Cosmetic contest. A bit more last minute than I would’ve liked, but it’s done! I made a skin for The Plague, inspired by Hel, a goddess of the dead in Scandinavian myth. She is associated with those who die of sickness or old age. She is described as being half alive and half rotting. (The dead half is described as being blue.) There’s a lot going on with her outfit so I’ll break it down beneath the cut.

The symbol on her deer skull mask is the Aegishjalmur, also known as the Helm of Awe or the Helm of Terror. This symbol can be found in the Icelandic Huld Manuscript and is mentioned in the Poetic Edda, the Codex Regius, and the Volsunga Saga. There are several versions of Aegishjalmur in the Huld Manuscript. One of them can be found on the forehead of the wolf skull on The Plague’s belt.

The wolf skull on her belt is representative of one of her siblings - Fenrir. The Plague’s necklaces are: a serpent torc (Jormungandr, her other sibling); two bead necklaces with teeth (representative of the four survivors she goes against); and a pendant of Loki (her father). The Loki necklace is based on a pendant found in Denmark.

You can see why I put this under a cut, right? Anyway, next up, the Younger Futhark runes. They’re from the Norwegian Rune Poem and describe the rune Kaun, which is also inscribed on the skull censer four times, but in Elder Futhark because it just looks better. Kaun translates as “sore” or “ulcer,” a fitting rune for the Plague.

The Norwegian Rune Poem excerpt reads:

Kaun er barna bǫlvan;

bǫl gørver nán fǫlvan.

Ulcer [Kaun] is fatal to children;

death makes a corpse pale.

Lastly, the Jelling knotwork on the robes. Full credit, although not required, goes to Jonas Lau Markussen. He doesn’t require credit if you purchase his work, which I did, but his stuff is so amazing that I had to give him a shout out anyway. You can buy his lovely pack of historically accurate knotwork styles for a tip of at least $5.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note to self:

- Study the Old English rune poem

- Study the Old Norse rune poem

- Study the Old Icelandic rune poem

- Keep studying Elder Futhark

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

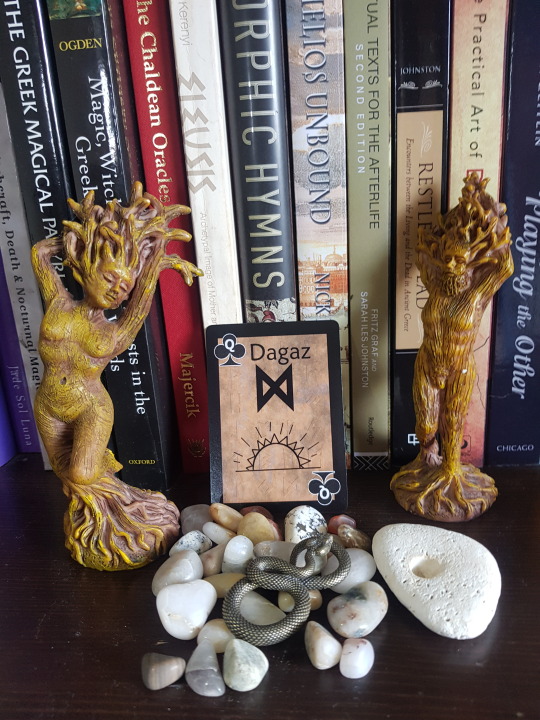

Dagaz

8th Rune of the 3rd AtetModern Letter: D

Rune Cards by Chaotic Shiny Productions

Also known asThe Germanic name: Daaz (Dagaz)The Norse name: DagrThe Anglo Saxon name: DaegThe Icslandic name: DagurThe Norwegian name: Dagr

Icelandic Rune PoemTranslationN/AN/ANorwegian Rune PoemTranslationN/AN/AAnglo Saxon Rune PoemTranslationDæg byþ drihtnes sond, deore mannum,mære metodes leoht, myrgþ and…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

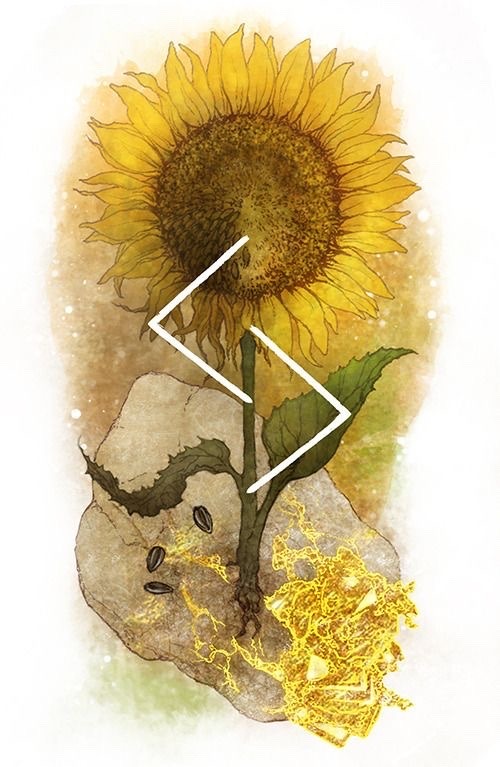

The harvest rune, Jera

(Art by Lunaria Gold)

Norwegian rune poem

Ár er gumna góðe;

get ek at orr var Fróðe.

(“Harvesttime brings bounty; I say that Frothi is generous!”)

Icelandic rune poem

Ár er gumna góði

ok gott sumar

algróinn akr

annus allvaldr.

(“Harvesttime brings profit, and a high summer and a ripened field.”)

#norse paganism#runes#personal notes#runic alphabet#mabon#autumn#fall#wheel of the year#paganism#norse mythology

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m my research around the Norse pagan sphere I’ve learned some things about runes that I didn’t know before. Here are the three main rune types there are are far more.

Elder Futhark - 2nd Century

Rune, UCS, Transliteration, IPA Proto-Germanic name Meaning

f ᚠ f /ɸ/, /f/ *fehu

"cattle; wealth"

u ᚢ u /u(ː)/ ?*ūruz

"aurochs", Wild ox (or *ûram "water/slag"?)

th,þ ᚦ þ /θ/, /ð/ ?*þurisaz

"Thurs" (see Jötunn) or *þunraz ("the god Thunraz")

a ᚨ a /a(ː)/ *ansuz "god"

r ᚱ r /r/ *raidō "ride, journey"

k ᚲ k (c) /k/ ?*kaunan

"ulcer"? (or *kenaz "torch"?)

g ᚷ g /ɡ/ *gebō "gift"

w ᚹ w /w/ *wunjō "joy"

h h ᚺ ᚻ h /h/ *hagalaz "hail" (the precipitation)

n ᚾ n /n/ *naudiz "need"

i ᛁ i /i(ː)/ *īsaz "ice"

j ᛃ j /j/ *jēra- "year, good year, harvest"

ï,ei ᛇ ï (æ) /æː/[9] *ī(h)waz "yew-tree"

p ᛈ p /p/ ?*perþ-

meaning unknown; possibly "pear-tree".

z ᛉ z /z/ ?*algiz "elk" (or "protection, defence"[10])

s s ᛊ ᛋ s /s/ *sōwilō "sun"

t ᛏ t /t/ *tīwaz "the god Tiwaz"

b ᛒ b /b/ *berkanan "birch"

e ᛖ e /e(ː)/ *ehwaz "horse"

m ᛗ m /m/ *mannaz "man"

l ᛚ l /l/ *laguz

"water, lake" (or possibly *laukaz "leek")

ŋ ŋ ᛜ ŋ /ŋ/ *ingwaz "the god Ingwaz"

d ᛞ d /d/ *dagaz "day"

o ᛟ o /o(ː)/ *ōþila-/*ōþala-

"heritage, estate, possession"

Anglo-Saxon runes

Unicode, Name, Name meaning, Transliteration IPA

ᚠ feh (feoh) wealth, cattle f /f/, [v] (word-medial allophone of /f/)

ᚢ ur (ūr) aurochs u /u(ː)/

ᚦ ðorn (þorn) thorn þ /θ/, [ð] (word-medial allophone of /θ/)

ᚩ os (ōs) heathen god (mouth in rune poem?) o /o(ː)/])

ᚱ rada (rād) riding r /r/

ᚳ cen (cēn) torch c /k/, /kʲ/, /tʃ/

ᚷ geofu (gyfu) gift g /ɡ/, [ɣ] (word-medial allophone of /ɡ/), /j/

ᚹ wyn (wynn) mirth w /w/

ᚻ hægil (hægl) hail h /h/, [x], [ç]

ᚾ næd (nēod) plight n /n/

ᛁ is (īs) ice i /i(ː)/

ᛡ/ᛄ gær (gēar) year j /j/

ᛇ ih (īw) yew tree ï /i(ː)/ [x], [ç]

ᛈ peord (peorð) (unknown) p /p/

ᛉ ilcs (eolh?) (unknown, perhaps a derivative of elk) x (otiose as a sound but still used to transliterate the Latin letter 'X' into runes)

ᛋ/ᚴ sygil (sigel) sun (sail in rune poem?)

s /s/, [z] (word-medial allophone of /s/)

ᛏ ti (Tīw) (unknown, originally god, Planet Mars in rune poem?) t /t/

ᛒ berc (beorc) birch tree b /b/

ᛖ eh (eh) steed e /e(ː)/

ᛗ mon (mann) man m /m/

ᛚ lagu (lagu) body of water (lake) l /l/

ᛝ ing (ing) Ing (Ingui-Frea?) ŋ /ŋg/, /ŋ/

ᛟ oedil (ēðel) inherited land, native country œ /ø(ː)/

ᛞ dæg (dæg) day d /d/

ᚪ ac (āc) oak tree a /ɑ(ː)/

ᚫ æsc (æsc) ash tree æ /æ(ː)/

ᛠ ear (ēar) (unknown, perhaps earth[16]) ea /æ(ː)ɑ/

ᚣ yr (ȳr) (unknown, perhaps bow[18]) y /y(ː)/

Youger Futhark - 8th~12th Century

The names of the 16 runes of the Younger futhark are recorded in the Icelandic and Norwegian rune poems. The names are:

ᚠ fé ("wealth")

ᚢ úr ("iron"/"rain")

ᚦ Thurs ("thurs", a type of entity, see jötunn)

ᚬ As/Oss ("(a) god")

ᚱ reið ("ride")

ᚴ kaun ("ulcer")

ᚼ hagall ("hail")

ᚾ/ᚿ nauðr ("need")

ᛁ ísa/íss ("ice")

ᛅ/ᛆ ár ("plenty")

ᛋ/ᛌ sól ("Sun", personified as a deity—see Sól (Germanic mythology))

ᛏ/ᛐ Týr ("Týr, a deity")

ᛒ björk/bjarkan/bjarken ("birch")

ᛘ maðr ("man, human")

ᛚ lögr ("sea")

ᛦ yr ("yew")

From comparison with Anglo-Saxon and Gothic letter names, most of these names directly continue the names of the Elder Futhark runes. The exceptions to this are:

• yr which continues the name of the unrelated Eihwaz rune;

• thurs and kaun, in which cases the Old Norse, Anglo-Saxon and Gothic traditions diverge.

Min Kilder (My Sources):

Elder Futhark|https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elder_Futhark

Anglo-Saxon Runes|https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-Saxon_runes

Younger Futhark|https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Younger_Futhark

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been recreating meanings of the runes for my own purposes based on nothing else than original and scholarly sources… and I’d like to propose a case for the ᛉ rune (in addition to ᛒ) to be associated with Frigg/Frig/Frija based on the Anglo-Saxon rune poem.

Elk-sedge keeps its home most often in the swamps,

it grows in the water, and grimly wounds,

it burns the blood of any man who grasps it.

———

This portion of the poem is something I have yet to see in “modernized” sources. Many say it means Elk based on the Proto-Germanic word of Algiz. But the Anglo-Saxon poem is the oldest that we know of, followed by the Norwegian and Icelandic poems. Or which, they read that this rune actually means “man.”

For me, I rather like the idea of the elk-sedge. Not only does it grow in the marshlands, the fens, it also feels very familiar to the story of the mistletoe.

(To be continued)

#frija#hearth mother#frig#goddess frigga#goddess frija#hearth magic#norse goddess frigg#viking runes#ancient runes#elder futhark runes#anglo saxon runes#runicmagic#rune magick#nordic runes#rune divination#live in courage#live in frith#water magic#water cultus

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

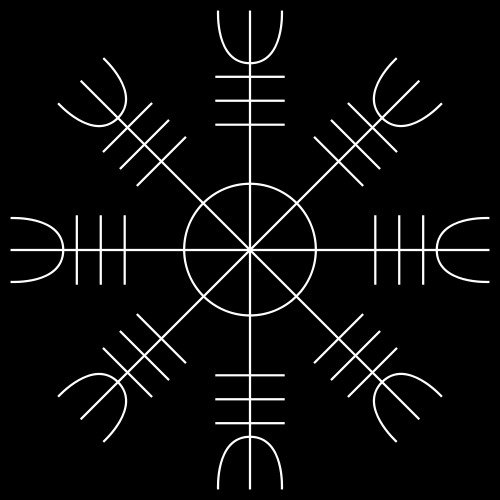

THE HELM OF AWE

Such overpowering might was apparently what this magical symbol was intended to produce. In the Fáfnismál, one of the poems in the Poetic Edda, the havoc-wreaking dragon Fafnir attributes much of his apparent invincibility to his use of the Helm of Awe:

The Helm of Awe

I wore before the sons of men

In defense of my treasure;

Amongst all, I alone was strong,

I thought to myself,

For I found no power a match for my own.

This interpretation is confirmed by a spell called “There is a Simple Helm of Awe Working” in the collection of Icelandic folktales collected by the great Jón Árnason in the nineteenth century. The spell reads:

Make a helm of awe in lead, press the lead sign between the eyebrows, and speak the formula:

Ægishjálm er ég ber

milli brúna mér!

I bear the helm of awe

between my brows!

Thus a man could meet his enemies and be sure of victory.

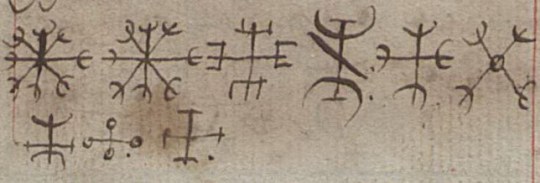

Like most ancient Germanic symbols, the form of its visual representation was far from strictly fixed. For example, the 41st spell in the Galdrabók, a seventeenth-century Icelandic grimoire, includes a drawing of the Helm of Awe with only four arms and without the sets of lines that run perpendicular to the arms.

Linguist and runologist Stephen Flowers notes that even though the references to the Helm of Awe in the Poetic Edda describe it as a physical thing charged with magical properties, the original meaning of the Old Norse hjálmr was “covering.” He goes on to theorize that:

This helm of awe was originally a kind of sphere of magical power to strike fear into the enemy. It was associated with the power of serpents to paralyze their prey before striking (hence, the connection with Fáfnir). … The helm of awe as described in the manuscript [the Galdrabók] is a power, centered in the pineal gland and emanating from it and the eyes. [In Aristotle and Neoplatonism, sources for much medieval magic, the spirit connects to the body via the pineal gland, and the eyes emit rays of spiritual power.] It is symbolized by a crosslike configuration, which in its simplest form is made up of what appear to be either four younger M-runes or older Z-runes. These figures can, however, become very complex.

The connection with the runes is particularly apt, because a number of the shapes that comprise the Helm of Awe have the same forms as certain runes. Given the centrality of the runes in Germanic magic as a whole, this correspondence is highly unlikely to have been coincidental.

The “arms” of the Helm appear to be Z-runes. The original name of this rune is unknown, but nowadays it’s often called “Algiz.” The meaning of this rune had much to do with protection and prevailing over one’s enemies, which makes it a fitting choice for inclusion in a symbol like the Helm of Awe.

The “spikes” that run perpendicular to the “arms” could be Isa runes. While the meaning of this rune is more or less unknown due to the confusing and contradictory information supplied by the primary sources, it seems reasonable to speculate that, since “Isa” means “ice,” its inclusion in the Helm of Awe could have imparted to the symbol a sense of concentration and hardening, as well as a connection to the animating spirits of wintry cold and darkness, the fearsome giants. This connection is made more likely by the fact that the dragon Fafnir occupies a role in the tales of the human hero Sigurd analogous to that occupied by the giants in the tales of the gods. Such connections are necessarily speculations, especially since the markings that may or may not be Isa runes are, graphically speaking, nothing more than straight lines, which makes them that much harder to positively identify. Nevertheless, the tenacity of the connections here is quite striking.

#helmofawe#transcendence#witchcraft#magick#magic#god#norse religion#vikings#norse runes#old norse#norse mythology#aegishjalmr#magic symbols#runes#nordic#nordic runes

3 notes

·

View notes