#New Orleans history

Text

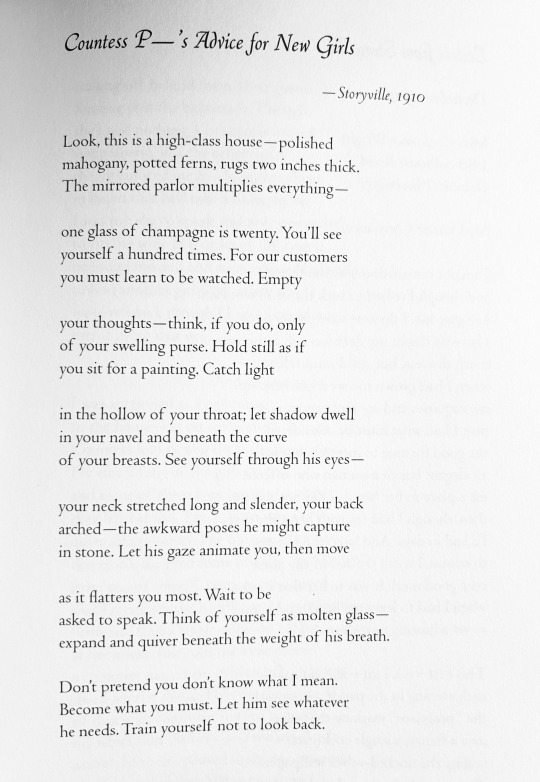

Natasha Trethewey (Bellocq’s Ophelia, 2002)

#op#natasha trethewey#poem#poetry#bellocq's ophelia#storyville portraits#storyville#new orleans#new orleans history#swer#e.j. bellocq#southern gothic

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Rhythm and blues was too good to remain a black secret for long and as the fifties dawned, certain musically adventurous white DJs started to add it to their playlists. By 1956 a quarter of the best-selling US records would be by black singers. This move was accelerated by the dramatic commercial success of some of the new black stations, exemplified by WDAI in Memphis - since 1948 the first black-owned radio station - which, as well as being home of DJs BB King and Rufus Thomas (he of the 'Funky Chicken'), was extremely profitable.

In adopting this subversive music, white DJs also started adopting black slang. This 'broadcast blackface', as Nelson George calls it, let them speak (and advertise) to both the black community and younger whites. Dewey Phillips of Memphis's WHBG was so successful at integrating his audience that the wily Sam Phillips of Sun Records chose him to broadcast Elvis Presley's first single.

The idea of the 'white negro' was still born of racism, however. George recounts the amazing tale of Vernon Winslow, a former university design teacher with a deep knowledge of jazz, who was denied a radio announcing job on New Orleans' WJMR simply because he was black. After what seemed like a successful interview, Winslow, who was quite light-skinned, was asked, 'By the way, are you a nigger?' Denied an on-air job merely because of his race, Winslow was hired for a most extraordinary job. He was to train a white DJ to sound black. Winslow had to feed a white colleague - now christened Poppa Stoppa - with the latest local slang, teaching him to say things like 'Look at the gold tooth, Ruth' and 'Wham bam, thank you ma'am'. The show became a smash. One night, frustrated by his behind-the-scenes existence, Winslow snuck a turn at the mic. He was fired immediately. WJMR kept the Poppa Stoppa name and continued using a white man, Clarence Hamman, to provide Poppa's voice. (Winslow had his revenge, though, as Doctor Daddy-O on New Orleans' WEZZ where he would become one of the country's top ten DJs.)"

- excerpt from Last Night a DJ Saved My Life by Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton

#black american history#dj history#dj tag#music history#radio history#racism#new orleans history#black music history#vernon winslow#book im reading right now

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Music is a form of prayer in New Orleans and across the sea in Haiti. It connects the living and the dead, the present with the past. Every year, in February and March, people all over the western hemisphere gather together to sing, dance, parade, and celebrate Carnival. The most famous Carnival celebration in the United States is New Orleans’ Mardi Gras.

Krewe Du Kanaval is back for its fourth year, February 9-12, celebrating the cultural connection shared by New Orleans and Haiti. This year’s theme and “bal” will honor the Warrior Women of Ayiti and Nouvelle-Orléans and feature Cimafunk & DJ Garo, RAM, 79rs Gang, DJ San Farafina, and surprise guests on Friday, February 10 at 8 p.m. in the Civic Theatre.

According to Krewe’s website, Anacaona was “The indigenous Queen of the Tainos who heroically held the Spanish at bay longer than any other and kept her kingdom under the rule of its people.” Adbaraya Toya, an elite African warrior of the Dahomey Kingdom, was captured and brought to Haiti as a slave but ended up raising the famous Haitian revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

Lastly, New Orleans’ famed “vaudou queen” Marie Laveau will be celebrated for the “rare multiracial community” she built and sustained in New Orleans.

SourceL L’Union Suite, Krewe Du Kanaval

Visit www.attawellsummer.com/forthosebefore to learn more about Black history and read new blog posts first.

Need a freelance graphic designer or illustrator? Send me an email.

#New Orleans#New Orleans history#Marie Laveau#Jean-Jacques Dessalines#Haitian Revolution#Adbaraya Toya#Krewe Du Kanaval#Mardi Gras#Carnival#krewes#Haiti#Haitian-American

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

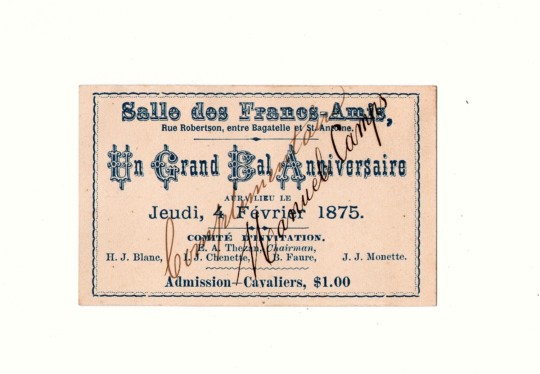

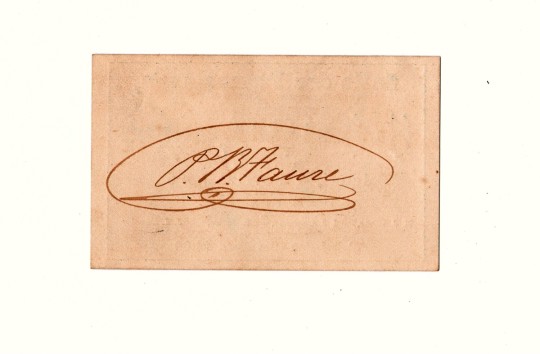

FRANC AMIS HALL / BALL INVITATION 1875

To say rare is an understatement , probably one of a kind , original Grand Ball invitation for Thursday, February 4, 1875 at the Francs Amis Hall on N. Robertson Street.

The FRANCS AMIS was a benevolent society and social dance hall probably the most important one formed by and for wealthy Creoles of color. La Société des Francs Amis (roughly, The Society of True Friends) bought this lot in 1861, and built the hall later in the 1800s (the gothic arched windows were probably early 20th century additions). Famed civil rights activist Homer Plessy, whose 1892 challenge to segregation laws in New Orleans resulted in the Supreme Court’s infamous “separate but equal” ruling of Plessy v Ferguson, was an officer of the society. Today, the Genesis Missionary Baptist Church worships in the building, which it has owned since 1963.

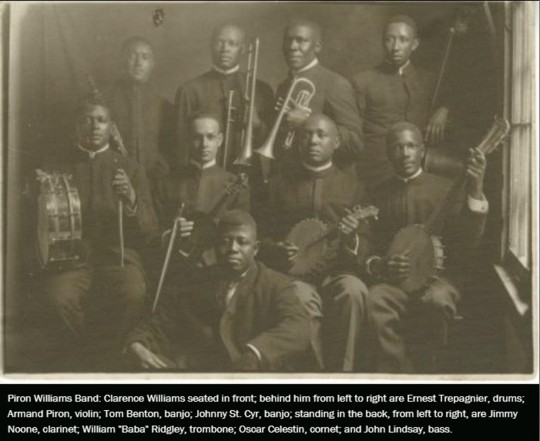

Jazz History Site / many great jazz bands played the Hall, Guitarist Johnny St. Cyr called it “a place of dignity” for downtown Creole society. It usually featured dance bands such as the John Robichaux Orchestra, the Superior Orchestra, and the Olympia Orchestra, but “hotter” uptown bands that included Pops Foster and Lee Collins reportedly played here as well. The club was popular with musicians, who earned $2.00 per engagement and ate and drank for free, according to Ricard Alexis, who played with Henry “Kid” Rena. “Wooden” Joe Nicholas, Hypolite Charles, and singer Lizzie Miles also performed here.

A hard to find piece of New Orleans, Creole of Colors, Civil Rights and Jazz History. The invitation has the name of MANUEL CAMP as a guest and the signature of J B FAURE one of the society members and part of the committee organizer of the ball.

Item No. E4983-119

Dimensions: 3.5″ x 2.25″

SOLD

#jazz history#jazz gems#jazz ephemera#ephemera#nola ephemera#francs amis#salle de francs amis#francs amis hall#creole of color#new orleans history#black creole#creoles of color#afro creole#black history#old new orleans

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jackson Square, 701 Decatur St, New Orleans (French Quarter), LA 70116

Jackson Square is the heart of the French Quarter, a place of historic significance and stunning beauty. It’s right by the Mississippi River and features a statue of Andrew Jackson, gorgeous buildings, cannons, a fountain, cannons, and the stunning St. Louis Cathedral.

Once known as the Place d’Armes, the park was named after Andrew Jackson, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans. It was the site of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. And with its proximity to the river port, the governor’s mansion and the church, it was the center of life in New Orleans

The shops around the perimeter are touristy and not very interesting. It also attracts interesting people offering psychic readings, street performances, live music, artists, etc. You can also hire a horse and carriage for a ride around the French Quarter.

The park gates are locked at night but people still hang out on the benches outside of the gates.

While it’s a very touristy area, it is a beautiful spot and the scene of Klaus & Elijah Mikaelson’s final scene on The Originals. The bench where they sat has two signs created to honor their memory. Always & forever. The signs are on the legs of the bench (under the bench). The artists and street performers have been in the area for a long time.

Don’t forget to get some beignets and a café au lait at Café Du Monde.

5 out of 5 stars

By Lolia S.

#Jackson Square#New Orleans#New Orleans history#French Quarter#The Originals#Klaus & Elijah Mikaelson#Saint Louis Cathedral#General Andrew Jackson

0 notes

Text

Those Delta Blues

Nothing like Delta Blues when you're missing the Big Easy

Delta Blues, also known as "race records", is a style of music that originated in the Mississippi Delta. A guitar, a harmonica and a singer are all that you needed to make music. Most songs were traditional African-American folk or field songs. Which is why you'll hear different recordings of the same songs.

Since the music of the early 1920's was marketed towards White-Americans; Black-Americans only made up small percentage of the consumer market. So when Black-Americans began recording music that would be marketed to their own people, it was labeled "race records"

The simple lyrics carry so much weight and meaning about the times and the culture. Delta Blues gives us a small glimpse of a segregated South. Msn goes to work for pennies, man comes home to a nagging wife, and so he's got to get out and have a drink. At least thats what the lyrics suggest. They sang about drink, promiscuity, depression and living in sin. For example we have the song "Me and the Devil" :

Me and the Devil

Was walkin' side by side

Me and the Devil, ooh

Was walkin' side by side

And I'm going to beat my woman

Until I get satisfied

A perfect depiction of depression and sin. Robert Johnson recorded the song just before his death, at the young age of 27.

But men weren't the only ones singing about this "fast" lifestyle. We have Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith and my favorite Ida Cox. All these women were singing songs that only men were known to do.

For example in the song Wild Woman Don't Have the Blues

I've got a disposition and a way of my own

When my man starts kicking I let him find another home

I get full of good liquor, walk the streets all night

Go home and put my man out if he don't act right

Wild women don't worry, wild women don't have the blues

Ida Cox gives women a lesson in keeping it moving with these fuck boys.

*GASP* Scandalous!

#delta blues#music history#mississippi blues#race music#folk music#black folk music#new orleans history#mississippi history#segregation history#charles patton#robert johnson#ma rainey#bessie smith#ida cox#blogger#did you know#history lessons#vintage moodboard#vintage music#vintage lifestyle#new orleans

1 note

·

View note

Text

New Orleans Drag Queens on Bourbon St,

1975

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

I tried to answer this succinctly, but it turned into an essay. (Sorry.)

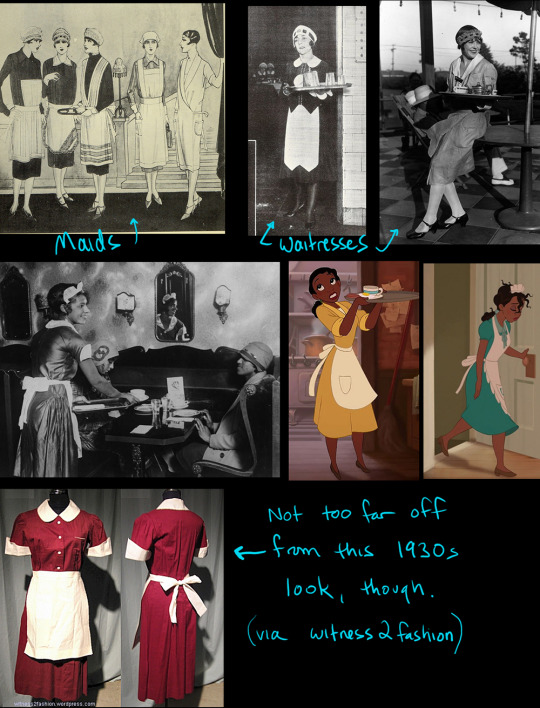

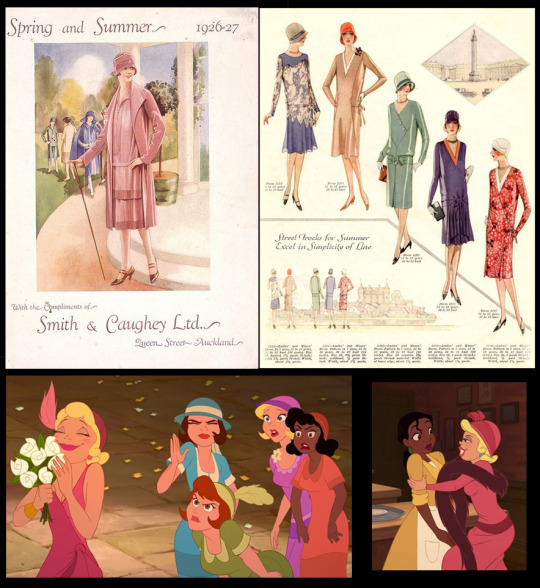

The Princess and the Frog was not accurate, strictly speaking, but dinging it for that would be like criticizing the Lion King for not being a realistic wildlife documentary. Accuracy wasn't really the point. Given the fantastical elements and fictional nations like “Maldonia”, I suppose we're meant to understand this as a bit removed from the real New Orleans. It's more a a jazz-flavored fairy tale than a historical fiction.

But for discussion's sake....

Is it fashion-accurate to its 1926 timeframe? Ehhh, sort of. It pays homage to 20s fashion trends with cloche hats, furs and feathery headpieces, but without fully committing to it. The waistline on almost all of Tiana's clothing is too high for the 20s, and the the shapes of her fancier costumes take a lot of liberties, or deviate wildly from the style of the period.

In the 20s, dresses (including workaday stuff) tended to have a straight up-and-down shape to it - kind of a low-waisted rectangle that de-emphasized curves instead of highlighting them. There are valid reasons to play fast and loose with that, though (something I’m definitely guilty of as well). One of those reasons is communication.

For instance, speculatively, the filmmakers wrote Tiana as a hard-working waitress and wanted her to look the part, so they made the choice to clothe her in something familiar - that gingham dress of mid-century shape that we broadly associate with diner waitresses. Actual waitress uniforms of the 20s had a fair bit of overlap with maid uniforms at the time too, and I can see why they wouldn't want to risk the confusion. It's more important to communicate clearly with the larger audience than to appease a small faction of fashion nerds who'd notice or care about the precision.

I don't think it's a case of the designers failing to do their research - I'm sure they had piles of references, and maybe even consultants - but they also had to have priorities.

With her hat and coat on, she looks a lot more 1920s-shaped.

Pretty consistently, the indication of the characteristic 1920s drop waist is there, but the approach otherwise ignores the 20s silhouette. The clothes hug the body too much. This may be about appealing to a 2000s audience, visually speaking, but also could be an animation thing. Maybe both. For practical reasons, clothes in 2d animation are usually more a sort of second skin than something that wears or behaves like realistic fabric.

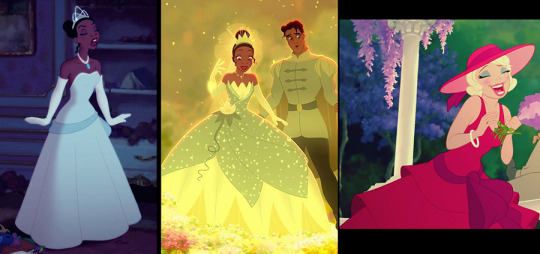

These are not in the 1920s ballpark at all. Tiana's blue gown looks like your basic Disney brand invention. Strapless things would have been extremely unusual and the overall shape is far out of step. Excusable, I guess, because it's a costume in context. Charlotte looks like she’s heading for a mimosa brunch in a modern maxi dress.

Charlotte's princess dress did seem to be calling back to the ultra-wide pannier side hoops of the 18th century - something that made a reappearance for part of the 20s, albeit in much milder form called robe de style. I'm not sure if the filmmakers were alluding to that at all, really, but either way, her dress is hilarious.

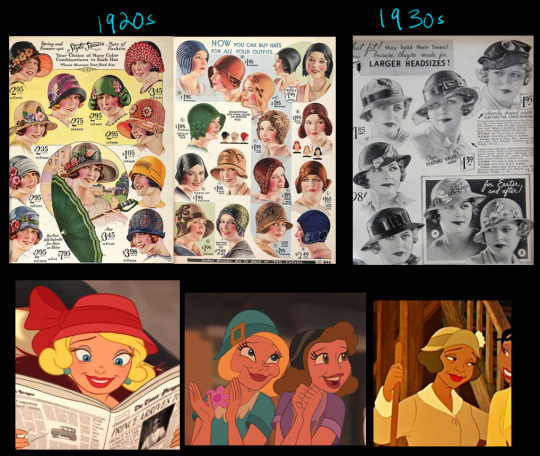

They only went about halfway with the cloche hats. The 1920s cloche really encapsulated the cranium, almost entirely covered bobbed hair, and obscured much of the face from certain angles, so it's easy to see why they've been somewhat reined in for the film. Still, it ends up looking more 1930s, where the hats started to recede away from the face, evolving in the direction of the pillbox.

Similarly, Tiana's hair is not very reminiscent of the bobbed, close-to-the-cranium style of the period, but I think that could legitimately be written off as characterization. She's not at all the type of person who'd fuss about going à la mode. Not everyone bobbed and finger-waved their hair.

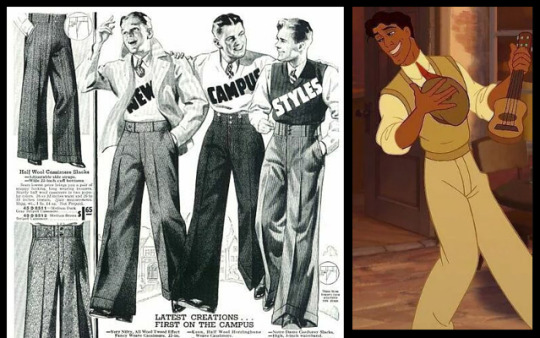

The clothes Prince Naveen is introduced in are very 1920s collegiate in spirit - the wide-leg oxford bags, the sleeveless pullover sweater, the flat cap, and high, stiff collar. The ukulele and banjolele were pretty trendy instruments at the time too.

Definitely some Josephine Baker vibes here. Also, the look of this whole fantasy sequence was reportedly inspired by the works of Aaron Douglas, a luminary painter of the Harlem Renaissance known for his depictions of the lives of African-Americans. (The mural is in Topeka, Kansas.)

They pretty much nailed the Art Deco. It's gorgeous. Looks somewhat inspired by the interiors of some of the Ralph Walker-designed NYC architecture, plus some French Quarter balcony flair for the final manifestation of Tiana's Place. Her dress here does resemble some gauzy mid-1920s looks, too.

------------------------------------------------

Culturally speaking...

New Orleans is an unusual place. Because some of the colonial Spanish and French laws and conventions that New Orleans evolved under persisted even after its inception into the United States; because it was such a heterogeneous hub of indigenous and immigrant peoples; and because it had a considerable population of free people of color (mostly Creole), it did not function quite like the rest of the South leading up to the Civil War, nor for a while after. Its particular coalescence of cultures made it its own unique sort of culture within the country, within the region, within the state of Louisiana even. By the early 20th century, though, regardless of the not-very-binary nature of New Orleans, Jim Crow laws were enforcing a literal black-and-white distinction, and not an evenhanded one, by far. In that aspect, the city had begun to resemble the rest of the South.

The film nods at the wealth disparity, but goes on to paint a pretty rosy picture of race and class relations at the time. Still it's not unbelievable that some people were exceptions to the rules. You could probably find a few compartments of old New Orleans society that resisted segregation or certain prejudicial norms, preferring to do things their own way. That aside, the film wasn't trying to confront these topics. Not every piece of media should have to. Sometimes breaking away from miserable period piece stereotypes is refreshing. I'm not sure it could have handled that meaningfully given the running time, narrow story focus, and intended audience, anyhow. (But you could perhaps also make a case that family films habitually underestimate younger audiences in this way.)

------------------------------------------------

Raymond the firefly I guess is the film's Cajun representation. There's not much to say about it, except perhaps to note that Evangeline is a reference to the heroine of a Longfellow poem of the same name. The poem is an epic romance set during the expulsion of the Acadians from the eastern provinces of Canada and the northernmost reaches of the American colonies (now Maine) by the British in the mid-1700s. Many exiled Acadians gradually migrated south to francophone-friendly Louisiana, settling into the prairies and bayous, where 'Acadian' truncated into the pronunciation 'Cajun'. Evangeline - who is only finally reunited with her love when he’s on his deathbed - has become an emblem of the heartbreak, separation and faithful hope of that cultural history, and there are parishes, statues and other landmarks named after the her throughout Louisiana.

------------------------------------------------

Voodoo does have a very historical presence in New Orleans, having arrived both directly from West Africa and by way of the Haitian diaspora (where it would more properly be called Vodou). While I don't think Disney's treatment of it was especially sensitive or serious, it also wasn't the grotesquely off-base sort of thing that media of the past has been known to do. It was largely whittled down to a magical plot component, but it wasn't so fully repurposed that it didn't resemble Voodoo at all either - and that's mostly owing to the characters, because it does appear the writers pulled from history there.

It’s apparently widely held that Dr. Facilier is a Baron Samedi caricature - and likely that's true, in part - but I have the impression he's also influenced by Doctor John. Not the 20th century funk musician, but the antebellum “Voodoo King” of New Orleans. Doctor John (also called Bayou John, Jean La Ficelle, and other aliases) claimed to be a Senegalese prince. He became well known as a potion man and romance-focused prognosticator to people from all corners of society. Though highly celebrated and financially successful at his peak, he seems ultimately remembered as an exploitative villain.

To my recollection, the film sort of gingerly avoids referring to Facilier as a Voodoo practitioner directly (I think he's more generically called a witch doctor in the script?) but it does seem to imply his 'friends on the other side' are a consortium of loa. It's mostly abbreviated into nebulously evil-seeming special FX, glazing over any specificity or dimensionality, but it does also loop back around as a vehicle of moral justice. Loa are all very individualistic and multi-faceted, but they do have reciprocal rules for asking favors of them.

There's also the benevolent counterpart in Mama Odie's character. Her wearing ritual whites has a definite basis in Voodoo/Vodou practice, and her depiction as a fairy godmother-like figure isn't entirely out of step with how a mambo may have been perceived...in a very general sense. They were/are ceremonial leaders and community bastions who people would seek out for help, advice and spiritual guidance. More than just emanating matronly good vibes, though, some have wielded considerable political and economic power.

(Just my opinions here. I've done a lot of reading on the subject for research but I'm no authority with any special insider understanding of Voodoo, and I really shouldn't be relied upon as an arbiter of who has or hasn't done it justice in fiction.)

------------------------------------------------

In summary--

Culturally, I think the film is respectably informed but paints a superficially genteel picture. The set pieces are gorgeous, but the story mostly delivers a sort of veneer of New Orleanishness. And as for fashion, well, it’s the 1920s run through a Disney filter. It’s very pretty, but it’s only as proximally accurate as seemed practical.

I don’t know that any of that really matters so much as whether or not it achieved what it intended, though. As a charming yarn and as a tribute to New Orleans and the Jazz age, I think it’s mostly successful. It’s also really beautifully animated!

#princess and the frog#disney#1920s#new orleans#jazz#fashion#voodoo#vodou#history#animation#art deco

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Amtrak - New Orleans, LA

Amtrak engine terminal at New Orleans, on April 16, 1981, hosts three different models of diesel motive power.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

His Name Was Bélizaire

The names and histories of black people, especially enslaved people, are really hard to find in traditional documentation. The work made by Jeremy K. Simien when acquiring this painting and then have it restored and researched is incredible, since he got to not only have it attributed to the French artist Jacques Amans but finding the name of the formerly erased enslaved teenager in the painting: Bélizaire.

It was acquired by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and this fall will be on view in Gallery 756 of the American Wing.

"Bélizaire and the Frey Children", ca. 1837, Jacques Aman (attributed). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

You can read more about this painting here:

"An 1837 Portrait of an Enslaved Child, Obscured by Overpainting for a Century, Has Been Restored and Acquired by the Met", Artnet, August 15 2023.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Acquires Important Painting Attributed to Jacques Amans, Met Museum, August 14 2023.

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

This makes Tiana the Princess of Creole Cuisine!

🍽️👩🏾🦱👑

#history#princess tiana#disney#princess and the frog#leah chase#animated history#disney princess#new orleans#food#movie#historical figures#creole#american history#united states#disney world#black girl magic#african american women#food history#soft black women#soft girl#women empowerment#black history#girl power#womens history#dooky chase#black femininity#princesscore#historical women#nickys facts

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in Hip Hop History:

Mannie Fresh was born March 20, 1969

#today in hip hop history#todayinhiphophistory#hiphop#hip-hop#hip hop#hip hop music#hip hop history#music#history#hip hop culture#music history#mannie fresh#bornday#birthday#producer#music producer#1969#cash money records#new orleans

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

She also collected stories from New Orleans. In her introduction to Mules and Men, she wrote, "Florida is a place that draws people - white people from all over the world, and negroes from every Southern state surely and some the North and West."

Hurston documented 70 folktales during the Florida trip, while the New Orleans trip yielded a number of stories about Marie Laveau and voodoo traditions. Many of the folktales are told in vernacular; recording the dialect and diction of the Black communities Hurston studied. She would also go on to study folktales from the Caribbean, including Jamaica and Haiti. Sterling Allen Brown was another writer who also studied folktales and vernacular from the South.

#mules and men#zora neale hurston#book#folktales#anthropology#history#eatonville#florida#new orleans#louisiana

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruby Bridges escorted to school by U.S. Marshals, 11/4/1960. NARA ID 175539851.

#OTD: Ruby Bridges Makes History

A small step for a little girl, a great step for Civil Rights

By Miriam Kleiman, Public Affairs

On November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges changed history when she walked into William Franz Public School in New Orleans following the court-ordered desegregation of New Orleans schools.

Fifty years later, President Obama welcomed her to the White House to see Norman Rockwell’s painting of her historic first day. "The Problem We All Live With” (1963) was displayed in the West Wing in summer 2011. See the Obama White House blog: President Obama Meets Civil Rights Icon Ruby Bridges, preserved by the Obama Library.

President Obama and Ruby Bridges at the White House, 7/15/2011. NARA ID 219775135.

Video: President Obama and Ruby Bridges at the White House!

youtube

See related:

Executive Order 10730: Desegregation of Central High School (1957)

Federal Records Relating to the Brown v. Board, ReDiscovering Black History blog by Tina Ligon

Teaching with Documents: Brown v. Board

Teaching with Documents: Bios of Key Figures in Brown v. Board

Eisenhower Library: Civil Rights: Brown v, Board

#ruby bridges#civil rights#obama library#black women#desegregation#blm#black lives matter#black history#new orleans#norman rockwell#rubybridgesfoundation

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

Street musicians, New Orleans, 2017 photo by @gwenllian-in-the-abbey

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is antitrust anti-labor?

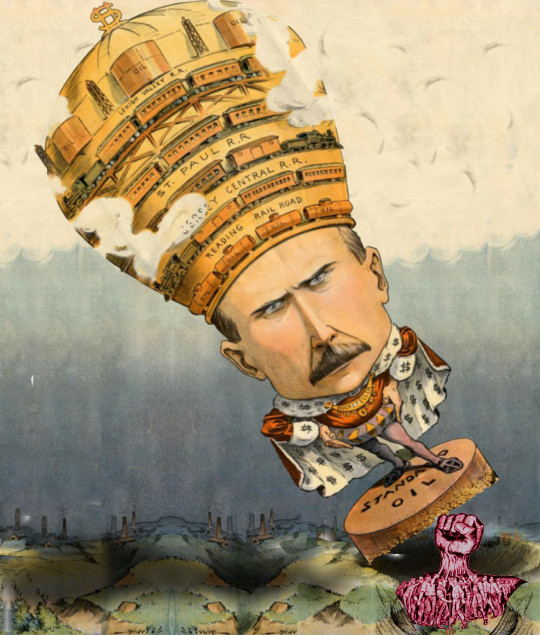

If you find the word “antitrust” has a dusty, old-fashioned feel, that’s only to be expected — after all, the word has its origins in the late 19th century, when the first billionaire was created: John D Rockefeller, who formed a “trust” with his oil industry competitors, through which they all agreed to stop competing with one another so they could concentrate on extracting more from their workers and their customers.

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/14/aiming-at-dollars/#not-men

Trusts were an incredibly successful business structure. A bunch of competing companies would be sold to a new holding company (“the trust”), and the owners of those old standalone companies would get stock in this new trust. The trust would operate as a single entity, hiking prices and suppressing wages. If anyone tried fight the trust with a new, independent company, the trust could freeze them out, by selling goods below cost, or by doing exclusive deals with key suppliers and customers, or both. Once a trust sewed up an industry, no one could compete. The trust barons were rulers for life.

The first successful trust was Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which amassed a 90% share of all US oil. Other “capitalists” got in on the game, forming the Cotton Seed Oil Trust (75% market share), the Sugar Trust (85%). Then came the Whiskey Trust and the Beef Trust. America was becoming a planned economy, run by a handful of unelected “industrialists” with lifetime appointments and the power to choose their successors.

A century after overthrowing the King, America had new kings: “kings over the production, transportation and sale of the necessities of life”. That’s how Senator John Sherman described the situation in 1890, when he was campaigning for the passage of the Sherman Act, the first “anti-trust” act. The Sherman Act wasn’t the first time American lawmakers tried to protect competition, but it was the first law passed after the failure of competition law led to the hijacking of the nation by people Sherman called the “autocrats of trade.”

https://marker.medium.com/we-should-not-endure-a-king-dfef34628153

The Sherman Act — and its successors, like the Clayton Act, are landmark laws in that they explicitly seek to protect workers and customers from corporate power. Antitrust is about making sure that no corporation gets so powerful that it’s too big to fail, nor too big to jail — that a company can’t get so big that it subverts the political process, capturing its own regulators:

https://doctorow.medium.com/small-government-fd5870a9462e

If American workers are derided as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires” who won’t join the fight against the rich because they assume they’ll soon join their ranks, then the American rich are “temporarily embarrassed aristocrats” who would welcome hereditary rule, provided they got to found one of the noble families. The goal of the American elite has always been to create a vast and durable dynasty, wealth so vast and well-insulated that even the most Habsburg-jawed failson can’t piss it away.

The American elite has always hated antitrust. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan, abetted by Robert Bork and his co-conspirators at the Chicago School of Economics gutted antitrust through something called the “consumer welfare standard,” which ended anti-monopoly enforcement except in instances where price hikes could be directly and unarguably attributed to market power, which is, basically, never.

It’s been 40 years since Reagan took antitrust out behind the Lincoln Monument and shot it in the guts, and America has turned into the kind of aristocratic kleptocracy that Sherman railed against, where “great families” control the nation’s wealth and politics and even its Supreme Court judges:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/06/clarence-thomas/#harlan-crow

Anything that can’t go on forever will eventually stop. Monopoly threatens the living standards, health, freedom and prosperity of nearly every person in America. The undeniable enshittification of the country by its guillotine-ready finance ghouls, tech bros and pharma profiteers has led to a resurgence in antitrust, and a complete renewal of the @FTC and @JusticeATR:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/party-its-1979-og-antitrust-back-baby

Key to the new and vibrant FTC is Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya, who, along with Commissioner Rebecca SlaughterFTC and Chairwoman Lina Khan, is part of the Democratic majority on the Commission. Bedoya has a background in tech and privacy and civil rights, and is a longtime advocate against predatory finance. He’s also a law professor and a sprightly scholarly writer.

Earlier this week, Bedoya gave a prepared speech for the Utah Project on Antitrust and Consumer Protection conference, entitled “Aiming at Dollars, Not Men.” It’s a banger:

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/bedoya-aiming-dollars-not-men.pdf

Criticisms of the new antitrust don’t just come from America’s oligarchs — the labor movement is skeptical of antitrust as well, and with good cause. Antitrust law prohibits collusion among businesses to raise prices, and at many junctures since the passage of the Sherman Act, judges have willfully perverted antitrust to punish labor organizers, treating workers demanding better working conditions as if they were Rockefeller and his cronies conspiring to raise prices.

This is the subject of Bedoya’s speech, whose transcript is painstakingly footnoted, and whose text makes it crystal clear that this is not what antitrust is for, and we should not tolerate its perversion in service to crushing worker power. The title comes from a 1914 remark by Democratic Congressman Thomas Konop, who said, of antitrust: “We are aiming at the gigantic trusts and combinations of capital and not at

associations of men for the betterment of their condition. We are aiming at the dollars and not at men.”

Konop was arguing for the passage of the Clayton Act, a successor to the Sherman Act, which was passed in part because judges refused to enforce the Sherman Act according to its plain language and its legislative intent, and kept using it against workers. In 1892, two years after the Sherman Act’s passage, it was used to crush the New Orleans General Strike, an interracial uprising against labor exploitation from longshoremen to printers to carpenters to hearse drivers.

Bosses went to a federal judge asking for an injunction against the strike. Though the judge admitted that the Sherman Act was designed to fight “the evils of massed capital,” he still issued the injunction.

The Sherman Act was used to clobber the Pullman Porters union, which organized Black workers who served on the Pullman cars on America’s railroads. The workers struck in 1894, after a 25% wage-cut, and they complained that they could no longer afford to eat and feed their families, so George Pullman fired them all. The workers struck, led by Eugene Debs. Pullman argued that the strike violated the Sherman Act. The Supreme Court voted 9:0 for Pullman, ordered the strike called off, and put Debs in prison.

In 1902, mercury-sickened hatters in Danbury, CT demanded better working conditions — after just a few years on the job, hatters would be disabled for life with mercury poisoning, with such bad tremors they couldn’t even feed themselves. 250 hatters at the DE Loewe company tried to unionize. Loewe sued them under the Sherman Act, and went to the Supreme Court, who awarded Loewe $6.8m in today’s money, which allowed Loewe to seize his former workers’ homes.

This is what sent Congress back to the drawing board to pass the Clayton Act. Though the Sherman Act was clear that it was about trustbusting, the courts kept interpreting it as a charter for union-busting. The Clayton Act explicitly permits workers to form unions, call for boycotts, and to organize sympathy strikes.

They made all this abundantly clear: writing in language so plain that judges had to understand the legislative intent. And yet…judges still managed to misread the Clayton Act, using it to block 2,100 strikes in the 1920s. It appears that passing the Clayton Act did not save a single strike that would have been killed by the bad (and bad faith) Sherman Act precedents that led to the Clayton Act in the first place.

The extent to which greedy bosses used the Clayton Act to attack their workers is genuinely ghastly. Bedoya describes one coal strike, against the Red Jacket Coal Company of Mingo, WV. The mine’s profits had grown by 600%, but workers’ wages weren’t keeping up with inflation. The miners sought a raise of $0.10 on the $0.66 they got paid for ever carload of coal they mined. The company didn’t even pay the workers with real money — just “company scrip”: coupons that could only be spent at the company store. Red Jacket gave its workers a $0.09/car raise — and raised prices at the company store by $0.25/item.

The workers struck, Red Jacket sued. The Fourth Circuit refused to apply the Clayton Act, following a precedent from a case called Duplex Printing that held that the Clayton Act only applied to people who stood “in the proximate relation of employer and employee.”

Congress was pissed. They passed the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932, with LaGuardia spitting about judges who “willfully disobeyed the law…emasculating it, taking out the meaning intended by Congress, making the law absolutely destructive of Congress’s intent.” Norris-LaGuardia creates an antitrust exemption for labor that applies “regardless of whether the disputants stand in the proximate relation of employer and employee.” So, basically: “CONGRESS TO JUDGES, GET BENT.”

And yet, judges still found ways to use antitrust as a cudgel to beat up workers. In Columbia River Packers, the court held that fishermen weren’t protected by the exemption for workers, because they were selling “commodities” (e.g. fish) not their labor. Presumably, the fish just leapt into the boats without anyone doing any work.

The willingness of enforcers to misread antitrust continued down through the ages. In 1999, the FTC destroyed the hopes of the some of the country’s most abused workers: “independent” port truckers, who worked 80 hours/week and still couldn’t pay the bills. Truckers were only paid to move trailers around the ports, but they were required to do hours and hours of unpaid work — loading containers, hauling equipment for repair, all for free. The truckers tried to organize a union — and the FTC subpoenaed the organizers for an investigation of price-fixing.

But the problem wasn’t with the laws. It was with judges who set precedents that — as LaGuardia said, “willfully disobeyed the law…emasculating it, taking out the meaning intended by Congress, making the law absolutely destructive of Congress’s intent.”

Congress passed laws to strengthen workers and judges — temporarily embarrassed aristocrats — simply acted as if the law was intended to smash workers. But by 2016, judges had it figured out. That’s when jockeys at the Camarero racetrack in Canóvana, Puerto Rico went on strike, demanding pay parity with their mainland peers — Puerto Rican jockeys got $20 to risk their lives riding, a fifth of what riders on the mainland received.

Predictably, the horse owners and racetrack sued. The jockeys lost in the lower court, and the court ordered the jockeys to pay the owners and the track a million dollars. They even sued the jockeys’ spouses, so that they could go after their paychecks to get that million bucks.

The case went to the First Circuit appeals court and Judge Sandra Lynch said: you know what, it doesn’t matter if the jockeys are employers or contractors. It doesn’t matter if they sell a commodity or their labor. The jockeys have the right to strike, period. That’s what the Clayton Act says. She overturned the lower court and threw out the fines.

As Bedoya says, antitrust is “law written to rein in the oil trust, the sugar trust, the beef trust…the gigantic trusts and combinations of capital…dollars and not at men.” Congress made that plain, “not once, not twice, but three times, each time in a louder and clearer

voice.”

Bedoya, part of the FTC’s Democratic majority, finishes: “Congress has made it clear that worker organizing and collective bargaining are not violations of the antitrust laws. When I vote, when I consider investigations and policy matters, that history will guide me.”

There's only three days left in the Kickstarter campaign for the audiobook of my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon's Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they're DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

#pluralistic#jockeys#antitrust#labor#history#judicial overreach#Alvaro Bedoya#consumer welfare standard#trustbusting#sherman act#new orleans general strike of 1892#pullman union#pullman porters#eugene debs#mad hatters#danbury hatters#clayton act#red jacket coal company#Fiorello LaGuardia#Norris-LaGuardia Act#duplex printing#Columbia River Packers#puerto rico#Camarero racetrack

219 notes

·

View notes