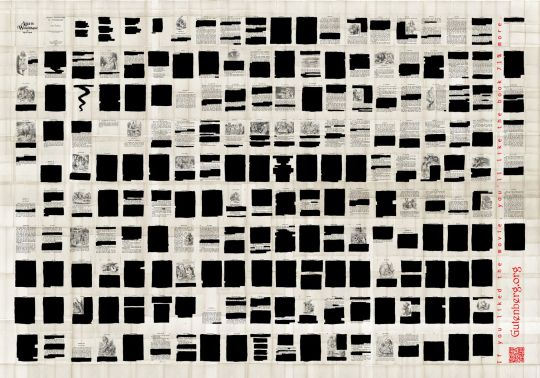

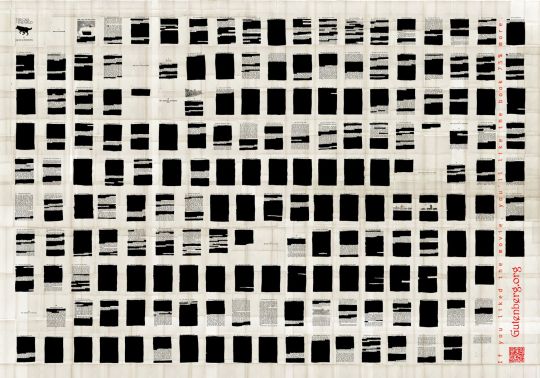

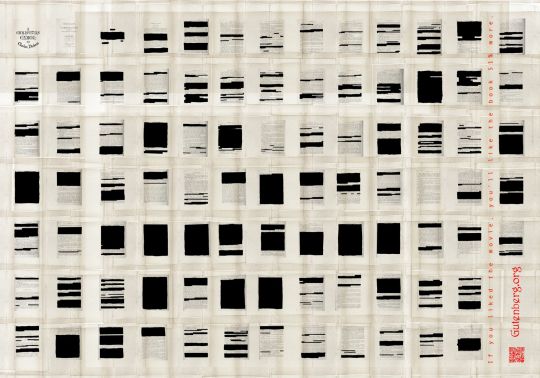

#Gutenberg Project

Text

Emily Brontë’s WUTHERING HEIGHTS; Chapter XV

Another week over—and I am so many days nearer health, and spring! I have now heard all my neighbour’s history, at different sittings, as the housekeeper could spare time from more important occupations. I’ll continue it in her own words, only a little condensed. She is, on the whole, a very fair narrator, and I don’t think I could improve her style.

* * * * *

In the evening, she said, the evening of my visit to the Heights, I knew, as well as if I saw him, that Mr. Heathcliff was about the place; and I shunned going out, because I still carried his letter in my pocket, and didn’t want to be threatened or teased any more. I had made up my mind not to give it till my master went somewhere, as I could not guess how its receipt would affect Catherine. The consequence was, that it did not reach her before the lapse of three days. The fourth was Sunday, and I brought it into her room after the family were gone to church. There was a man servant left to keep the house with me, and we generally made a practice of locking the doors during the hours of service; but on that occasion the weather was so warm and pleasant that I set them wide open, and, to fulfil my engagement, as I knew who would be coming, I told my companion that the mistress wished very much for some oranges, and he must run over to the village and get a few, to be paid for on the morrow. He departed, and I went upstairs.

Mrs. Linton sat in a loose white dress, with a light shawl over her shoulders, in the recess of the open window, as usual. Her thick, long hair had been partly removed at the beginning of her illness, and now she wore it simply combed in its natural tresses over her temples and neck. Her appearance was altered, as I had told Heathcliff; but when she was calm, there seemed unearthly beauty in the change. The flash of her eyes had been succeeded by a dreamy and melancholy softness; they no longer gave the impression of looking at the objects around her: they appeared always to gaze beyond, and far beyond—you would have said out of this world. Then, the paleness of her face—its haggard aspect having vanished as she recovered flesh—and the peculiar expression arising from her mental state, though painfully suggestive of their causes, added to the touching interest which she awakened; and—invariably to me, I know, and to any person who saw her, I should think—refuted more tangible proofs of convalescence, and stamped her as one doomed to decay.

A book lay spread on the sill before her, and the scarcely perceptible wind fluttered its leaves at intervals. I believe Linton had laid it there: for she never endeavoured to divert herself with reading, or occupation of any kind, and he would spend many an hour in trying to entice her attention to some subject which had formerly been her amusement. She was conscious of his aim, and in her better moods endured his efforts placidly, only showing their uselessness by now and then suppressing a wearied sigh, and checking him at last with the saddest of smiles and kisses. At other times, she would turn petulantly away, and hide her face in her hands, or even push him off angrily; and then he took care to let her alone, for he was certain of doing no good.

Gimmerton chapel bells were still ringing; and the full, mellow flow of the beck in the valley came soothingly on the ear. It was a sweet substitute for the yet absent murmur of the summer foliage, which drowned that music about the Grange when the trees were in leaf. At Wuthering Heights it always sounded on quiet days following a great thaw or a season of steady rain. And of Wuthering Heights Catherine was thinking as she listened: that is, if she thought or listened at all; but she had the vague, distant look I mentioned before, which expressed no recognition of material things either by ear or eye.

“There’s a letter for you, Mrs. Linton,” I said, gently inserting it in one hand that rested on her knee. “You must read it immediately, because it wants an answer. Shall I break the seal?” “Yes,” she answered, without altering the direction of her eyes. I opened it—it was very short. “Now,” I continued, “read it.” She drew away her hand, and let it fall. I replaced it in her lap, and stood waiting till it should please her to glance down; but that movement was so long delayed that at last I resumed—“Must I read it, ma’am? It is from Mr. Heathcliff.”

There was a start and a troubled gleam of recollection, and a struggle to arrange her ideas. She lifted the letter, and seemed to peruse it; and when she came to the signature she sighed: yet still I found she had not gathered its import, for, upon my desiring to hear her reply, she merely pointed to the name, and gazed at me with mournful and questioning eagerness.

“Well, he wishes to see you,” said I, guessing her need of an interpreter. “He’s in the garden by this time, and impatient to know what answer I shall bring.”

As I spoke, I observed a large dog lying on the sunny grass beneath raise its ears as if about to bark, and then smoothing them back, announce, by a wag of the tail, that some one approached whom it did not consider a stranger. Mrs. Linton bent forward, and listened breathlessly. The minute after a step traversed the hall; the open house was too tempting for Heathcliff to resist walking in: most likely he supposed that I was inclined to shirk my promise, and so resolved to trust to his own audacity. With straining eagerness Catherine gazed towards the entrance of her chamber. He did not hit the right room directly: she motioned me to admit him, but he found it out ere I could reach the door, and in a stride or two was at her side, and had her grasped in his arms.

He neither spoke nor loosed his hold for some five minutes, during which period he bestowed more kisses than ever he gave in his life before, I daresay: but then my mistress had kissed him first, and I plainly saw that he could hardly bear, for downright agony, to look into her face! The same conviction had stricken him as me, from the instant he beheld her, that there was no prospect of ultimate recovery there—she was fated, sure to die.

“Oh, Cathy! Oh, my life! how can I bear it?” was the first sentence he uttered, in a tone that did not seek to disguise his despair. And now he stared at her so earnestly that I thought the very intensity of his gaze would bring tears into his eyes; but they burned with anguish: they did not melt.

“What now?” said Catherine, leaning back, and returning his look with a suddenly clouded brow: her humour was a mere vane for constantly varying caprices. “You and Edgar have broken my heart, Heathcliff! And you both come to bewail the deed to me, as if you were the people to be pitied! I shall not pity you, not I. You have killed me—and thriven on it, I think. How strong you are! How many years do you mean to live after I am gone?”

Heathcliff had knelt on one knee to embrace her; he attempted to rise, but she seized his hair, and kept him down.

“I wish I could hold you,” she continued, bitterly, “till we were both dead! I shouldn’t care what you suffered. I care nothing for your sufferings. Why shouldn’t you suffer? I do! Will you forget me? Will you be happy when I am in the earth? Will you say twenty years hence, ‘That’s the grave of Catherine Earnshaw? I loved her long ago, and was wretched to lose her; but it is past. I’ve loved many others since: my children are dearer to me than she was; and, at death, I shall not rejoice that I am going to her: I shall be sorry that I must leave them!’ Will you say so, Heathcliff?”

“Don’t torture me till I’m as mad as yourself,” cried he, wrenching his head free, and grinding his teeth.

The two, to a cool spectator, made a strange and fearful picture. Well might Catherine deem that heaven would be a land of exile to her, unless with her mortal body she cast away her moral character also. Her present countenance had a wild vindictiveness in its white cheek, and a bloodless lip and scintillating eye; and she retained in her closed fingers a portion of the locks she had been grasping. As to her companion, while raising himself with one hand, he had taken her arm with the other; and so inadequate was his stock of gentleness to the requirements of her condition, that on his letting go I saw four distinct impressions left blue in the colourless skin.

“Are you possessed with a devil,” he pursued, savagely, “to talk in that manner to me when you are dying? Do you reflect that all those words will be branded in my memory, and eating deeper eternally after you have left me? You know you lie to say I have killed you: and, Catherine, you know that I could as soon forget you as my existence! Is it not sufficient for your infernal selfishness, that while you are at peace I shall writhe in the torments of hell?”

“I shall not be at peace,” moaned Catherine, recalled to a sense of physical weakness by the violent, unequal throbbing of her heart, which beat visibly and audibly under this excess of agitation. She said nothing further till the paroxysm was over; then she continued, more kindly—

“I’m not wishing you greater torment than I have, Heathcliff. I only wish us never to be parted: and should a word of mine distress you hereafter, think I feel the same distress underground, and for my own sake, forgive me! Come here and kneel down again! You never harmed me in your life. Nay, if you nurse anger, that will be worse to remember than my harsh words! Won’t you come here again? Do!”

Heathcliff went to the back of her chair, and leant over, but not so far as to let her see his face, which was livid with emotion. She bent round to look at him; he would not permit it: turning abruptly, he walked to the fireplace, where he stood, silent, with his back towards us. Mrs. Linton’s glance followed him suspiciously: every movement woke a new sentiment in her. After a pause and a prolonged gaze, she resumed; addressing me in accents of indignant disappointment:—

“Oh, you see, Nelly, he would not relent a moment to keep me out of the grave. That is how I’m loved! Well, never mind. That is not my Heathcliff. I shall love mine yet; and take him with me: he’s in my soul. And,” added she musingly, “the thing that irks me most is this shattered prison, after all. I’m tired of being enclosed here. I’m wearying to escape into that glorious world, and to be always there: not seeing it dimly through tears, and yearning for it through the walls of an aching heart: but really with it, and in it. Nelly, you think you are better and more fortunate than I; in full health and strength: you are sorry for me—very soon that will be altered. I shall be sorry for you. I shall be incomparably beyond and above you all. I wonder he won’t be near me!” She went on to herself. “I thought he wished it. Heathcliff, dear! you should not be sullen now. Do come to me, Heathcliff.”

In her eagerness she rose and supported herself on the arm of the chair. At that earnest appeal he turned to her, looking absolutely desperate. His eyes, wide and wet, at last flashed fiercely on her; his breast heaved convulsively. An instant they held asunder, and then how they met I hardly saw, but Catherine made a spring, and he caught her, and they were locked in an embrace from which I thought my mistress would never be released alive: in fact, to my eyes, she seemed directly insensible. He flung himself into the nearest seat, and on my approaching hurriedly to ascertain if she had fainted, he gnashed at me, and foamed like a mad dog, and gathered her to him with greedy jealousy. I did not feel as if I were in the company of a creature of my own species: it appeared that he would not understand, though I spoke to him; so I stood off, and held my tongue, in great perplexity.

A movement of Catherine’s relieved me a little presently: she put up her hand to clasp his neck, and bring her cheek to his as he held her; while he, in return, covering her with frantic caresses, said wildly—

“You teach me now how cruel you’ve been—cruel and false. Why did you despise me? Why did you betray your own heart, Cathy? I have not one word of comfort. You deserve this. You have killed yourself. Yes, you may kiss me, and cry; and wring out my kisses and tears: they’ll blight you—they’ll damn you. You loved me—then what right had you to leave me? What right—answer me—for the poor fancy you felt for Linton? Because misery and degradation, and death, and nothing that God or Satan could inflict would have parted us, you, of your own will, did it. I have not broken your heart—you have broken it; and in breaking it, you have broken mine. So much the worse for me that I am strong. Do I want to live? What kind of living will it be when you—oh, God! would you like to live with your soul in the grave?”

“Let me alone. Let me alone,” sobbed Catherine. “If I’ve done wrong, I’m dying for it. It is enough! You left me too: but I won’t upbraid you! I forgive you. Forgive me!”

“It is hard to forgive, and to look at those eyes, and feel those wasted hands,” he answered. “Kiss me again; and don’t let me see your eyes! I forgive what you have done to me. I love my murderer—but yours! How can I?”

They were silent—their faces hid against each other, and washed by each other’s tears. At least, I suppose the weeping was on both sides; as it seemed Heathcliff could weep on a great occasion like this.

I grew very uncomfortable, meanwhile; for the afternoon wore fast away, the man whom I had sent off returned from his errand, and I could distinguish, by the shine of the western sun up the valley, a concourse thickening outside Gimmerton chapel porch.

“Service is over,” I announced. “My master will be here in half an hour.”

Heathcliff groaned a curse, and strained Catherine closer: she never moved.

Ere long I perceived a group of the servants passing up the road towards the kitchen wing. Mr. Linton was not far behind; he opened the gate himself and sauntered slowly up, probably enjoying the lovely afternoon that breathed as soft as summer.

“Now he is here,” I exclaimed. “For heaven’s sake, hurry down! You’ll not meet any one on the front stairs. Do be quick; and stay among the trees till he is fairly in.”

“I must go, Cathy,” said Heathcliff, seeking to extricate himself from his companion’s arms. “But if I live, I’ll see you again before you are asleep. I won’t stray five yards from your window.”

“You must not go!” she answered, holding him as firmly as her strength allowed. “You shall not, I tell you.”

“For one hour,” he pleaded earnestly.

“Not for one minute,” she replied.

“I must—Linton will be up immediately,” persisted the alarmed intruder.

He would have risen, and unfixed her fingers by the act—she clung fast, gasping: there was mad resolution in her face.

“No!” she shrieked. “Oh, don’t, don’t go. It is the last time! Edgar will not hurt us. Heathcliff, I shall die! I shall die!”

“Damn the fool! There he is,” cried Heathcliff, sinking back into his seat. “Hush, my darling! Hush, hush, Catherine! I’ll stay. If he shot me so, I’d expire with a blessing on my lips.”

And there they were fast again. I heard my master mounting the stairs—the cold sweat ran from my forehead: I was horrified.

“Are you going to listen to her ravings?” I said, passionately. “She does not know what she says. Will you ruin her, because she has not wit to help herself? Get up! You could be free instantly. That is the most diabolical deed that ever you did. We are all done for—master, mistress, and servant.”

I wrung my hands, and cried out; and Mr. Linton hastened his step at the noise. In the midst of my agitation, I was sincerely glad to observe that Catherine’s arms had fallen relaxed, and her head hung down.

“She’s fainted, or dead,” I thought: “so much the better. Far better that she should be dead, than lingering a burden and a misery-maker to all about her.”

Edgar sprang to his unbidden guest, blanched with astonishment and rage. What he meant to do I cannot tell; however, the other stopped all demonstrations, at once, by placing the lifeless-looking form in his arms.

“Look there!” he said. “Unless you be a fiend, help her first—then you shall speak to me!”

He walked into the parlour, and sat down. Mr. Linton summoned me, and with great difficulty, and after resorting to many means, we managed to restore her to sensation; but she was all bewildered; she sighed, and moaned, and knew nobody. Edgar, in his anxiety for her, forgot her hated friend. I did not. I went, at the earliest opportunity, and besought him to depart; affirming that Catherine was better, and he should hear from me in the morning how she passed the night.

“I shall not refuse to go out of doors,” he answered; “but I shall stay in the garden: and, Nelly, mind you keep your word to-morrow. I shall be under those larch-trees. Mind! or I pay another visit, whether Linton be in or not.”

He sent a rapid glance through the half-open door of the chamber, and, ascertaining that what I stated was apparently true, delivered the house of his luckless presence.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE COMMUNITY (USA) for Gutenberg Project

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tues. Jan. 24, 2023: Digging Out

image courtesy of Richard Duijnstee via pixabay.com

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

Waxing Moon

No Retrogrades

Snowy and cold

Whew! Finally, we are done, for a brief shining moment with retrogrades, since Uranus went direct on Sunday the 22nd.

Which was also Chinese Lunar New Year, and we are now in the Year of the Water Rabbit.

Which is why tomorrow was chosen as the launch day for ANGEL…

View On WordPress

#Agatha Christie Reading#Alice Campbell#ANGEL HUNT#baking#Chinese Lunar New Year#Commonwealth Catalgoue#cooking#CW Mars#Dreamsacpe#Edith Sitwell#Evelyn Salter#FLOWER DRUM SONG#garage#Gutenberg Project#HADESTOWN#Heist Romance#ill#JUGGERNAUT#Kyle of Lochalsh#Legerdemain#library#London#MISS SAIGON#Nice#No Kid Hungry#Paris#review#SAD CYPRESS#snow#Train

0 notes

Text

Today's reading list

A retrospective reading list today, as I was researching the historical background for an essay. These resources were all actually incredibly relevant - it took a full day to process them, but I feel much more capable now of asserting that the points I'm making out of the literary texts will be supported by critical ones.

MacDonald, Robert. Sons of the Empire: The Frontier and the Boy Scout Movement, 1890-1918. University of Toronto Press, 1993.

A chance call with my uncle this morning reminded me that Baden-Powell and his contemporaries were overtly inspired by writers such as Kipling, so the Scouting movement is perfect for the context of what values and qualities the nineteenth/twentieth century hoped to instill in its boys.

Brown, Michael; Barry, Anna Maria and Begiato (eds). Martial Masculinities: Experiencing and Imagining the Military in the Long Nineteenth Century. Manchester University Press, 2019.

This was a great overview of what men aspired to and were expected to aspire to in this period, as well as signposting me to the next great resource. This text directly connects the ideals of masculinity to empire/war, which is perfect.

Smiles, Samuel. Self-Help; with illustrations of conduct and perseverence. John Murray, 1859, accessed via the Gutenberg Project

I want to kiss the Gutenberg project on the mouth. I've been really struggling to find books of the period which discuss how men 'ought' to be - and this is the jackpot. I found a mention of it in Martial Masculinities and managed to track it down on Gutenberg - I think it's meaty enough to be my primary source of this type, along with my critical sources for commentary.

So... touch wood, that should be my reading for this essay done. Now I just have to check my plan still makes sense, probably resend it to my tutor for discussion on Monday, and then wait for the Christmas holidays to hit so I can get started on writing! This term has been... a lot. But as long as I can churn out two solid essays by the beginning of January, that should be the most concentrated period of work sorted.

#reading list#masculinity#nineteenth century#studyblr#academic writing#academic reading#social history#gutenberg project

0 notes

Video

The Yellow Book

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41875

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41876

The Savoy (periodical)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Savoy_%28periodical%29

https://archive.org/details/savoy01symo/

https://archive.org/details/savoy02symo/

https://archive.org/details/savoy03symo/

#tiktok#book history#books and literature#books and writing#books and libraries#books and authors#books and reading#art#art history#1890s#19th century#the yellow book#the savoy#lit mag#literary history#literature#art magazine#books#project gutenberg#oscar wilde

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cherry Tree, white (Prunus sp.)

#my art#wha#witch hat atelier#Δ帽子#Qifrey#ive got sketches and flowers picked out for Olruggio and the apprentices too#all the flowers here have meanings too#all meanings taken from Kate Greenaway’s book on project Gutenberg#cherry tree (white) - deception

797 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yo, Quick PSA. I want to tell y'all about Standard Ebooks, ive been really loving them as of late and thought this would be of interest to my followers

Since 2015 these people have been turning public domain ebooks from project gutenberg into beautiful ebooks that have a nice cover, standardized typing and structure and work well on almost all e-readers and e-book apps.

This is by far the best way to read some of these books. Look through their catalog and see if you find something you like.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey everyone! i recently compiled a bunch of useful links to various online archives, libraries, and the like, and i wanted to share the result since i feel like a lot of these resources would be very useful to people!!

feel free (enouraged even) to repost/share this wherever you want, or even take the links for your own masterposts or compiled resources or whatever. the goal i had in mind when making this was to share knowledge, not to take credit or anything, so go wild!

fair warning this is fairly targeted towards online leftist queer spaces since those are the circles i run in but this is tumblr so figured that wouldn't be a problem lol

also, if anyone has any cool sources or links they want me to add to make it more comprehensive, just hit me up!

#original#resources#online resources#archive#internet#science#culture#history#language#queer#queer history#lgbt history#marxism#communism#anarchism#adding as many tags as i can think of lol#kind of really want this to spread i was proud of it#and i think it would be useful to others#oh more tags hold on#project gutenberg#internet archive

989 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Pierce” in Persuasion

Jane Austen does this thing where she uses certain words only for certain characters or in certain novels. Emma uses the word “blunder” more than any other book (it’s a major plot clue) and the word “supernumerary” is only used twice in her entire compendium and both times it’s near Mrs. Norris in Mansfield Park.

The novel Persuasion uses the word “pierce” exactly twice and both times it’s said by Captain Wentworth:

He stopped. A sudden recollection seemed to occur, and to give him some taste of that emotion which was reddening Anne’s cheeks and fixing her eyes on the ground. After clearing his throat, however, he proceeded thus—

“I confess that I do think there is a disparity, too great a disparity, and in a point no less essential than mind. I regard Louisa Musgrove as a very amiable, sweet-tempered girl, and not deficient in understanding, but Benwick is something more. He is a clever man, a reading man; and I confess, that I do consider his attaching himself to her with some surprise. Had it been the effect of gratitude, had he learnt to love her, because he believed her to be preferring him, it would have been another thing. But I have no reason to suppose it so. It seems, on the contrary, to have been a perfectly spontaneous, untaught feeling on his side, and this surprises me. A man like him, in his situation! with a heart pierced, wounded, almost broken! Fanny Harville was a very superior creature, and his attachment to her was indeed attachment. A man does not recover from such a devotion of the heart to such a woman. He ought not; he does not.” (Ch 20)

And the second:

“I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope.... (Ch 22)

Wentworth cannot understand how Captain Benwick can recover from the wound of losing the love of his life, because Wentworth never has. These two statements are bound by the word “pierce”.

(Thank you Project Gutenberg. I only noticed this because I use “pierce” as a search term to find the letter)

#project gutenberg#jane austen#persuasion#captain wentworth#you pierce my soul#I should do more of these and make a tag for them#Jane Austen Wordsmith#wordsmith means a skilled user of words.#that'll work#I have a few more of them

457 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love being a literary nerd who is obsessed with classic lit because even if I forget to bring a book I can always read texts with expired copyright legal and free

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emily Brontë’s WUTHERING HEIGHTS; Chapter XIII

For two months the fugitives remained absent; in those two months, Mrs. Linton encountered and conquered the worst shock of what was denominated a brain fever. No mother could have nursed an only child more devotedly than Edgar tended her. Day and night he was watching, and patiently enduring all the annoyances that irritable nerves and a shaken reason could inflict; and, though Kenneth remarked that what he saved from the grave would only recompense his care by forming the source of constant future anxiety—in fact, that his health and strength were being sacrificed to preserve a mere ruin of humanity—he knew no limits in gratitude and joy when Catherine’s life was declared out of danger; and hour after hour he would sit beside her, tracing the gradual return to bodily health, and flattering his too sanguine hopes with the illusion that her mind would settle back to its right balance also, and she would soon be entirely her former self.

The first time she left her chamber was at the commencement of the following March. Mr. Linton had put on her pillow, in the morning, a handful of golden crocuses; her eye, long stranger to any gleam of pleasure, caught them in waking, and shone delighted as she gathered them eagerly together.

“These are the earliest flowers at the Heights,” she exclaimed. “They remind me of soft thaw winds, and warm sunshine, and nearly melted snow. Edgar, is there not a south wind, and is not the snow almost gone?”

“The snow is quite gone down here, darling,” replied her husband; “and I only see two white spots on the whole range of moors: the sky is blue, and the larks are singing, and the becks and brooks are all brim full. Catherine, last spring at this time, I was longing to have you under this roof; now, I wish you were a mile or two up those hills: the air blows so sweetly, I feel that it would cure you.”

“I shall never be there but once more,” said the invalid; “and then you’ll leave me, and I shall remain for ever. Next spring you’ll long again to have me under this roof, and you’ll look back and think you were happy to-day.”

Linton lavished on her the kindest caresses, and tried to cheer her by the fondest words; but, vaguely regarding the flowers, she let the tears collect on her lashes and stream down her cheeks unheeding. We knew she was really better, and, therefore, decided that long confinement to a single place produced much of this despondency, and it might be partially removed by a change of scene. The master told me to light a fire in the many-weeks’ deserted parlour, and to set an easy-chair in the sunshine by the window; and then he brought her down, and she sat a long while enjoying the genial heat, and, as we expected, revived by the objects round her: which, though familiar, were free from the dreary associations investing her hated sick chamber. By evening she seemed greatly exhausted; yet no arguments could persuade her to return to that apartment, and I had to arrange the parlour sofa for her bed, till another room could be prepared. To obviate the fatigue of mounting and descending the stairs, we fitted up this, where you lie at present—on the same floor with the parlour; and she was soon strong enough to move from one to the other, leaning on Edgar’s arm. Ah, I thought myself, she might recover, so waited on as she was. And there was double cause to desire it, for on her existence depended that of another: we cherished the hope that in a little while Mr. Linton’s heart would be gladdened, and his lands secured from a stranger’s gripe, by the birth of an heir.

I should mention that Isabella sent to her brother, some six weeks from her departure, a short note, announcing her marriage with Heathcliff. It appeared dry and cold; but at the bottom was dotted in with pencil an obscure apology, and an entreaty for kind remembrance and reconciliation, if her proceeding had offended him: asserting that she could not help it then, and being done, she had now no power to repeal it. Linton did not reply to this, I believe; and, in a fortnight more, I got a long letter, which I considered odd, coming from the pen of a bride just out of the honeymoon. I’ll read it: for I keep it yet. Any relic of the dead is precious, if they were valued living.

* * * * *

DEAR ELLEN, it begins,—I came last night to Wuthering Heights, and heard, for the first time, that Catherine has been, and is yet, very ill. I must not write to her, I suppose, and my brother is either too angry or too distressed to answer what I sent him. Still, I must write to somebody, and the only choice left me is you.

Inform Edgar that I’d give the world to see his face again—that my heart returned to Thrushcross Grange in twenty-four hours after I left it, and is there at this moment, full of warm feelings for him, and Catherine! I can’t follow it though—(these words are underlined)—they need not expect me, and they may draw what conclusions they please; taking care, however, to lay nothing at the door of my weak will or deficient affection.

The remainder of the letter is for yourself alone. I want to ask you two questions: the first is,—How did you contrive to preserve the common sympathies of human nature when you resided here? I cannot recognise any sentiment which those around share with me.

The second question I have great interest in; it is this—Is Mr. Heathcliff a man? If so, is he mad? And if not, is he a devil? I sha’n’t tell my reasons for making this inquiry; but I beseech you to explain, if you can, what I have married: that is, when you call to see me; and you must call, Ellen, very soon. Don’t write, but come, and bring me something from Edgar.

Now, you shall hear how I have been received in my new home, as I am led to imagine the Heights will be. It is to amuse myself that I dwell on such subjects as the lack of external comforts: they never occupy my thoughts, except at the moment when I miss them. I should laugh and dance for joy, if I found their absence was the total of my miseries, and the rest was an unnatural dream!

The sun set behind the Grange as we turned on to the moors; by that, I judged it to be six o’clock; and my companion halted half an hour, to inspect the park, and the gardens, and, probably, the place itself, as well as he could; so it was dark when we dismounted in the paved yard of the farmhouse, and your old fellow-servant, Joseph, issued out to receive us by the light of a dip candle. He did it with a courtesy that redounded to his credit. His first act was to elevate his torch to a level with my face, squint malignantly, project his under-lip, and turn away. Then he took the two horses, and led them into the stables; reappearing for the purpose of locking the outer gate, as if we lived in an ancient castle.

Heathcliff stayed to speak to him, and I entered the kitchen—a dingy, untidy hole; I daresay you would not know it, it is so changed since it was in your charge. By the fire stood a ruffianly child, strong in limb and dirty in garb, with a look of Catherine in his eyes and about his mouth.

“This is Edgar’s legal nephew,” I reflected—“mine in a manner; I must shake hands, and—yes—I must kiss him. It is right to establish a good understanding at the beginning.”

I approached, and, attempting to take his chubby fist, said—“How do you do, my dear?”

He replied in a jargon I did not comprehend.

“Shall you and I be friends, Hareton?” was my next essay at conversation.

An oath, and a threat to set Throttler on me if I did not “frame off” rewarded my perseverance.

“Hey, Throttler, lad!” whispered the little wretch, rousing a half-bred bull-dog from its lair in a corner. “Now, wilt thou be ganging?” he asked authoritatively.

Love for my life urged a compliance; I stepped over the threshold to wait till the others should enter. Mr. Heathcliff was nowhere visible; and Joseph, whom I followed to the stables, and requested to accompany me in, after staring and muttering to himself, screwed up his nose and replied—“Mim! mim! mim! Did iver Christian body hear aught like it? Mincing un’ munching! How can I tell whet ye say?”

“I say, I wish you to come with me into the house!” I cried, thinking him deaf, yet highly disgusted at his rudeness.

“None o’ me! I getten summut else to do,” he answered, and continued his work; moving his lantern jaws meanwhile, and surveying my dress and countenance (the former a great deal too fine, but the latter, I’m sure, as sad as he could desire) with sovereign contempt.

I walked round the yard, and through a wicket, to another door, at which I took the liberty of knocking, in hopes some more civil servant might show himself. After a short suspense, it was opened by a tall, gaunt man, without neckerchief, and otherwise extremely slovenly; his features were lost in masses of shaggy hair that hung on his shoulders; and his eyes, too, were like a ghostly Catherine’s with all their beauty annihilated.

“What’s your business here?” he demanded, grimly. “Who are you?”

“My name was Isabella Linton,” I replied. “You’ve seen me before, sir. I’m lately married to Mr. Heathcliff, and he has brought me here—I suppose by your permission.”

“Is he come back, then?” asked the hermit, glaring like a hungry wolf.

“Yes—we came just now,” I said; “but he left me by the kitchen door; and when I would have gone in, your little boy played sentinel over the place, and frightened me off by the help of a bull-dog.”

“It’s well the hellish villain has kept his word!” growled my future host, searching the darkness beyond me in expectation of discovering Heathcliff; and then he indulged in a soliloquy of execrations, and threats of what he would have done had the “fiend” deceived him.

I repented having tried this second entrance, and was almost inclined to slip away before he finished cursing, but ere I could execute that intention, he ordered me in, and shut and re-fastened the door. There was a great fire, and that was all the light in the huge apartment, whose floor had grown a uniform grey; and the once brilliant pewter-dishes, which used to attract my gaze when I was a girl, partook of a similar obscurity, created by tarnish and dust. I inquired whether I might call the maid, and be conducted to a bedroom! Mr. Earnshaw vouchsafed no answer. He walked up and down, with his hands in his pockets, apparently quite forgetting my presence; and his abstraction was evidently so deep, and his whole aspect so misanthropical, that I shrank from disturbing him again.

You’ll not be surprised, Ellen, at my feeling particularly cheerless, seated in worse than solitude on that inhospitable hearth, and remembering that four miles distant lay my delightful home, containing the only people I loved on earth; and there might as well be the Atlantic to part us, instead of those four miles: I could not overpass them! I questioned with myself—where must I turn for comfort? and—mind you don’t tell Edgar, or Catherine—above every sorrow beside, this rose pre-eminent: despair at finding nobody who could or would be my ally against Heathcliff! I had sought shelter at Wuthering Heights, almost gladly, because I was secured by that arrangement from living alone with him; but he knew the people we were coming amongst, and he did not fear their intermeddling.

I sat and thought a doleful time: the clock struck eight, and nine, and still my companion paced to and fro, his head bent on his breast, and perfectly silent, unless a groan or a bitter ejaculation forced itself out at intervals. I listened to detect a woman’s voice in the house, and filled the interim with wild regrets and dismal anticipations, which, at last, spoke audibly in irrepressible sighing and weeping. I was not aware how openly I grieved, till Earnshaw halted opposite, in his measured walk, and gave me a stare of newly-awakened surprise. Taking advantage of his recovered attention, I exclaimed—“I’m tired with my journey, and I want to go to bed! Where is the maid-servant? Direct me to her, as she won’t come to me!”

“We have none,” he answered; “you must wait on yourself!”

“Where must I sleep, then?” I sobbed; I was beyond regarding self-respect, weighed down by fatigue and wretchedness.

“Joseph will show you Heathcliff’s chamber,” said he; “open that door—he’s in there.”

I was going to obey, but he suddenly arrested me, and added in the strangest tone—“Be so good as to turn your lock, and draw your bolt—don’t omit it!”

“Well!” I said. “But why, Mr. Earnshaw?” I did not relish the notion of deliberately fastening myself in with Heathcliff.

“Look here!” he replied, pulling from his waistcoat a curiously-constructed pistol, having a double-edged spring knife attached to the barrel. “That’s a great tempter to a desperate man, is it not? I cannot resist going up with this every night, and trying his door. If once I find it open he’s done for; I do it invariably, even though the minute before I have been recalling a hundred reasons that should make me refrain: it is some devil that urges me to thwart my own schemes by killing him. You fight against that devil for love as long as you may; when the time comes, not all the angels in heaven shall save him!”

I surveyed the weapon inquisitively. A hideous notion struck me: how powerful I should be possessing such an instrument! I took it from his hand, and touched the blade. He looked astonished at the expression my face assumed during a brief second: it was not horror, it was covetousness. He snatched the pistol back, jealously; shut the knife, and returned it to its concealment.

“I don’t care if you tell him,” said he. “Put him on his guard, and watch for him. You know the terms we are on, I see: his danger does not shock you.”

“What has Heathcliff done to you?” I asked. “In what has he wronged you, to warrant this appalling hatred? Wouldn’t it be wiser to bid him quit the house?”

“No!” thundered Earnshaw; “should he offer to leave me, he’s a dead man: persuade him to attempt it, and you are a murderess! Am I to lose all, without a chance of retrieval? Is Hareton to be a beggar? Oh, damnation! I will have it back; and I’ll have his gold too; and then his blood; and hell shall have his soul! It will be ten times blacker with that guest than ever it was before!”

You’ve acquainted me, Ellen, with your old master’s habits. He is clearly on the verge of madness: he was so last night at least. I shuddered to be near him, and thought on the servant’s ill-bred moroseness as comparatively agreeable. He now recommenced his moody walk, and I raised the latch, and escaped into the kitchen. Joseph was bending over the fire, peering into a large pan that swung above it; and a wooden bowl of oatmeal stood on the settle close by. The contents of the pan began to boil, and he turned to plunge his hand into the bowl; I conjectured that this preparation was probably for our supper, and, being hungry, I resolved it should be eatable; so, crying out sharply, “I’ll make the porridge!” I removed the vessel out of his reach, and proceeded to take off my hat and riding-habit. “Mr. Earnshaw,” I continued, “directs me to wait on myself: I will. I’m not going to act the lady among you, for fear I should starve.”

“Gooid Lord!” he muttered, sitting down, and stroking his ribbed stockings from the knee to the ankle. “If there’s to be fresh ortherings—just when I getten used to two maisters, if I mun hev’ a mistress set o’er my heead, it’s like time to be flitting. I niver did think to see t’ day that I mud lave th’ owld place—but I doubt it’s nigh at hand!”

This lamentation drew no notice from me: I went briskly to work, sighing to remember a period when it would have been all merry fun; but compelled speedily to drive off the remembrance. It racked me to recall past happiness and the greater peril there was of conjuring up its apparition, the quicker the thible ran round, and the faster the handfuls of meal fell into the water. Joseph beheld my style of cookery with growing indignation.

“Thear!” he ejaculated. “Hareton, thou willn’t sup thy porridge to-neeght; they’ll be naught but lumps as big as my neive. Thear, agean! I’d fling in bowl un’ all, if I wer ye! There, pale t’ guilp off, un’ then ye’ll hae done wi’t. Bang, bang. It’s a mercy t’ bothom isn’t deaved out!”

It was rather a rough mess, I own, when poured into the basins; four had been provided, and a gallon pitcher of new milk was brought from the dairy, which Hareton seized and commenced drinking and spilling from the expansive lip. I expostulated, and desired that he should have his in a mug; affirming that I could not taste the liquid treated so dirtily. The old cynic chose to be vastly offended at this nicety; assuring me, repeatedly, that “the barn was every bit as good” as I, “and every bit as wollsome,” and wondering how I could fashion to be so conceited. Meanwhile, the infant ruffian continued sucking; and glowered up at me defyingly, as he slavered into the jug.

“I shall have my supper in another room,” I said. “Have you no place you call a parlour?”

“Parlour!” he echoed, sneeringly, “parlour! Nay, we’ve noa parlours. If yah dunnut loike wer company, there’s maister’s; un’ if yah dunnut loike maister, there’s us.”

“Then I shall go upstairs,” I answered; “show me a chamber.”

I put my basin on a tray, and went myself to fetch some more milk. With great grumblings, the fellow rose, and preceded me in my ascent: we mounted to the garrets; he opened a door, now and then, to look into the apartments we passed.

“Here’s a rahm,” he said, at last, flinging back a cranky board on hinges. “It’s weel eneugh to ate a few porridge in. There’s a pack o’ corn i’ t’ corner, thear, meeterly clane; if ye’re feared o’ muckying yer grand silk cloes, spread yer hankerchir o’ t’ top on’t.”

The “rahm” was a kind of lumber-hole smelling strong of malt and grain; various sacks of which articles were piled around, leaving a wide, bare space in the middle.

“Why, man,” I exclaimed, facing him angrily, “this is not a place to sleep in. I wish to see my bed-room.”

“Bed-rume!” he repeated, in a tone of mockery. “Yah’s see all t’ bed-rumes thear is—yon’s mine.”

He pointed into the second garret, only differing from the first in being more naked about the walls, and having a large, low, curtainless bed, with an indigo-coloured quilt, at one end.

“What do I want with yours?” I retorted. “I suppose Mr. Heathcliff does not lodge at the top of the house, does he?”

“Oh! it’s Maister Hathecliff’s ye’re wanting?” cried he, as if making a new discovery. “Couldn’t ye ha’ said soa, at onst? un’ then, I mud ha’ telled ye, baht all this wark, that that’s just one ye cannut see—he allas keeps it locked, un’ nob’dy iver mells on’t but hisseln.”

“You’ve a nice house, Joseph,” I could not refrain from observing, “and pleasant inmates; and I think the concentrated essence of all the madness in the world took up its abode in my brain the day I linked my fate with theirs! However, that is not to the present purpose—there are other rooms. For heaven’s sake be quick, and let me settle somewhere!”

He made no reply to this adjuration; only plodding doggedly down the wooden steps, and halting before an apartment which, from that halt and the superior quality of its furniture, I conjectured to be the best one. There was a carpet—a good one, but the pattern was obliterated by dust; a fireplace hung with cut-paper, dropping to pieces; a handsome oak-bedstead with ample crimson curtains of rather expensive material and modern make; but they had evidently experienced rough usage: the vallances hung in festoons, wrenched from their rings, and the iron rod supporting them was bent in an arc on one side, causing the drapery to trail upon the floor. The chairs were also damaged, many of them severely; and deep indentations deformed the panels of the walls. I was endeavouring to gather resolution for entering and taking possession, when my fool of a guide announced,—“This here is t’ maister’s.” My supper by this time was cold, my appetite gone, and my patience exhausted. I insisted on being provided instantly with a place of refuge, and means of repose.

“Whear the divil?” began the religious elder. “The Lord bless us! The Lord forgie us! Whear the hell wold ye gang? ye marred, wearisome nowt! Ye’ve seen all but Hareton’s bit of a cham’er. There’s not another hoile to lig down in i’ th’ hahse!”

I was so vexed, I flung my tray and its contents on the ground; and then seated myself at the stairs’-head, hid my face in my hands, and cried.

“Ech! ech!” exclaimed Joseph. “Weel done, Miss Cathy! weel done, Miss Cathy! Howsiver, t’ maister sall just tum’le o’er them brocken pots; un’ then we’s hear summut; we’s hear how it’s to be. Gooid-for-naught madling! ye desarve pining fro’ this to Churstmas, flinging t’ precious gifts uh God under fooit i’ yer flaysome rages! But I’m mista’en if ye shew yer sperrit lang. Will Hathecliff bide sich bonny ways, think ye? I nobbut wish he may catch ye i’ that plisky. I nobbut wish he may.”

And so he went on scolding to his den beneath, taking the candle with him; and I remained in the dark. The period of reflection succeeding this silly action compelled me to admit the necessity of smothering my pride and choking my wrath, and bestirring myself to remove its effects. An unexpected aid presently appeared in the shape of Throttler, whom I now recognised as a son of our old Skulker: it had spent its whelphood at the Grange, and was given by my father to Mr. Hindley. I fancy it knew me: it pushed its nose against mine by way of salute, and then hastened to devour the porridge; while I groped from step to step, collecting the shattered earthenware, and drying the spatters of milk from the banister with my pocket-handkerchief. Our labours were scarcely over when I heard Earnshaw’s tread in the passage; my assistant tucked in his tail, and pressed to the wall; I stole into the nearest doorway. The dog’s endeavour to avoid him was unsuccessful; as I guessed by a scutter downstairs, and a prolonged, piteous yelping. I had better luck: he passed on, entered his chamber, and shut the door. Directly after Joseph came up with Hareton, to put him to bed. I had found shelter in Hareton’s room, and the old man, on seeing me, said,—“They’s rahm for boath ye un’ yer pride, now, I sud think i’ the hahse. It’s empty; ye may hev’ it all to yerseln, un’ Him as allas maks a third, i’ sich ill company!”

Gladly did I take advantage of this intimation; and the minute I flung myself into a chair, by the fire, I nodded, and slept. My slumber was deep and sweet, though over far too soon. Mr. Heathcliff awoke me; he had just come in, and demanded, in his loving manner, what I was doing there? I told him the cause of my staying up so late—that he had the key of our room in his pocket. The adjective our gave mortal offence. He swore it was not, nor ever should be, mine; and he’d—but I’ll not repeat his language, nor describe his habitual conduct: he is ingenious and unresting in seeking to gain my abhorrence! I sometimes wonder at him with an intensity that deadens my fear: yet, I assure you, a tiger or a venomous serpent could not rouse terror in me equal to that which he wakens. He told me of Catherine’s illness, and accused my brother of causing it; promising that I should be Edgar’s proxy in suffering, till he could get hold of him.

I do hate him—I am wretched—I have been a fool! Beware of uttering one breath of this to any one at the Grange. I shall expect you every day—don’t disappoint me!—ISABELLA.

0 notes

Text

The immense satisfaction that comes from saying "wait, how old is this book?" when Amazon tries to sell me a very old-fashioned-looking work for 'just £1.99' and then finding it on Project Gutenberg for free instead.

#that history book from 1900 is going to be very out of date but sometimes there's some appealing element in there#and obvs many primary sources themselves are already old anyway#and old fiction too! mary shelley wrote a novel about perkin warbeck! (i need to get round to reading that one)#70000 free books you are bound to want at least one of them right?#has the author been dead for long enough that you think of them as a historical figure? their work is probably free by now!#tumblr faves Moby Dick and Dracula are there you know. Sherlock Holmes! Oscar Wilde and Jane Austen. Mary Shelley AND her mum!#protip: rename the files as you download them otherwise you'll never guess which is which as the filenames are just numbers#*slaps the roof of project gutenberg* you can fit so much out-of-copyright material in this thing.

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

I would be lost without Project Gutenberg honestly

362 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiiii mechs lore archives! i heard some stuff about carmilla turning into a cat. is that canon? (i might need the answer for big fanfic plot reasons)

Hello! Carmilla turning into a cat (or, as it's affectionately known, Catmilla) is, semi-canon, as it comes from the Forbidden Lore. I unfortunately can't give you a citation for that, as Maki has asked that the Forbidden Lore document only be circulated in her discord server. This is because the Forbidden Lore is largely off-the-cuff answers she gives to questions in the server, and is often less thought-out and more prone to change than the lore they put in their performed and published music.

I can, however, give you a citation for the inspiration for this. Carmilla of the 1872 novel is capable of turning into a catlike creature as part of her vampiric powers, which is why Dr. Carmilla can. From chapter 6 of the novel:

"I cannot call it a nightmare, for I was quite conscious of being asleep.

"But I was equally conscious of being in my room, and lying in bed, precisely as I actually was. I saw, or fancied I saw, the room and its furniture just as I had seen it last, except that it was very dark, and I saw something moving round the foot of the bed, which at first I could not accurately distinguish. But I soon saw that it was a sooty-black animal that resembled a monstrous cat. It appeared to me about four or five feet long for it measured fully the length of the hearthrug as it passed over it; and it continued to-ing and fro-ing with the lithe, sinister restlessness of a beast in a cage."

Do with that as you will! Good luck with your fic; we need more good Carmilla fic, in my professional opinion!

#mod miralines#i would 10/10 recommend reading the novel#both for its own sake and for doc c redstringing reasons#the link is to the full text on project gutenberg if anyone is interested#doctor carmilla#forbidden lore#carmilla

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know what I’m really looking forward to in s3 (or later) of The Gilded Age? Marian getting engaged and hopefully getting a copy of Dr George Napheys’ “The Physical Life Of Woman” from Aunt Agnes the night before her wedding

Aunt Agnes wouldn’t want Marian to be uninformed or unprepared for what being a wife and mother means, especially with her own experiences in that field, but of course it’s too indelicate to actually *speak* of. So here’s a radical and progressive (for the time) informative medical text written by a Philadelphia doctor that you can read for yourself in the privacy of your own room

Why do I think this will happen? Because it’s what happened to my great-grandmother the night before her wedding in 1894.

#the gilded age#the book is available on project Gutenberg and I highly recommend it#it’s a wild fucking ride and one of the most entertaining things I’ve ever read#(I don’t think I ever finished it but my fucking god it’s good)

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

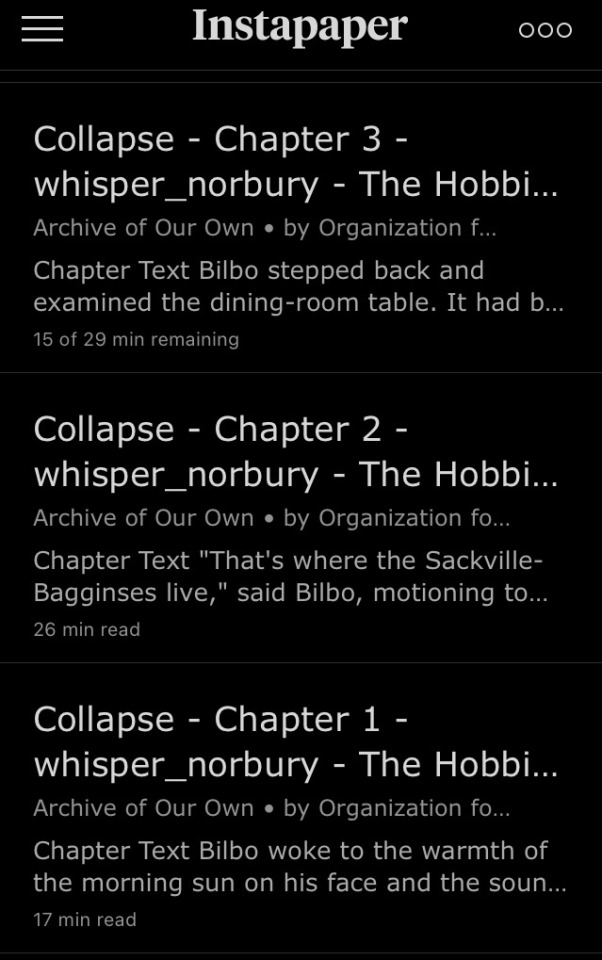

Okay, listen up.

If you have an iPhone and are worried about AO3 going down, what you need to do is go to the App Store and get Instapaper.

You can save tons of fics on there to read offline. There's even dark mode, and you can change the font style and size.

Also, there is text-to-speech, you can organize things into folders, and you can save across devices (save something on your iPhone, for example, and you can access it on your computer or iPad).

And it's free. There is a paid version, but it is just for extras - I have never seen an ad of any type on Instapaper, and I have literally had it for over a decade. Actually, I got it from one of those free app cards they used to give away at Starbucks!

You can save pages and articles and recipes and such from all over the place. Even fics from FanFiction.net (the download doesn't show the ads that tend to pop up over there now!). You can even download entire books from Project Gutenberg!

So seriously, check it out.

At times when AO3 is down, you will definitely appreciate having it!

67 notes

·

View notes