#Biodiversity journal

Text

What Is JBES Journal?

JBES Journal

JBES is the short name of the Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, an open-access scholarly research journal on Environmental Sciences and Biodiversity. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences |JBES is a fast and peer-reviewed journal and is scheduled to publish 12 issues in a year. It publishes original research papers, short communications, and review papers on the main aspects of Environmental Sciences, Biology, Atmospheric Sciences, Environmental chemistry, Earth science, Ecology, Forestry, Agroforestry, Biodiversity, Taxonomy, Ethnobotany, Vegetation survey, Bioremediation, Geosciences, Organisms, and Conservation of Natural sciences.

ISSN: 2220-6663 (Print)

ISSN: 2222-3045 (Online)

Issue: 12 in a year

Publication Speed: Fast and Continuous

Scope:

It covers all areas of Environmental science and Biodiversity including Forestry, Geography, Geosciences, Ecology, Zoology, Botany, Mineralogy, Oceanology, Oceanography, Hydrology, Limnology, Soil science, Geology & Mining, Atmospheric science, Natural history, Taxonomy, Ethno biology, Medicine, Environmental studies & Engineering, Natural resource management, Global climate change, Global warming, Environmental pollution & restoration, Bioremediation, Natural landscape, Urban planning, Sustainable development, Environmental monitoring & planning.

Editor in-Chief

Dr. M. Anowar Razvy

Email: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

The stunning biodiversity of Staithes beachfront

It looks like the surface of another planet!

#nature#nature photography#marine life#biodiversity#north yorkshire#yorkshire#rocks#nature lovers#travelphotography#travel diary#travel journal#travel#goblin core#green witch#sea#sea life#sea creatures#art inspiration#nature is beautiful

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's #LoveHornbillsDay!

Plates from Edinburgh Journal of Natural History and of the Physical Sciences via Biodiversity Heritage Library:

Vol. 1 (1835-9), XCIX.B

Vol. 2 (1839-40), XCIX

#animals in art#animal holiday#european art#birds in art#illustration#bird#birds#19th century art#Edinburgh Journal of Natural History and of the Physical Sciences#BHL#Biodiversity Heritage Library#lithograph#book plate#scientific illustration#natural history art#ornithological illustration#hornbill#hornbills#ornithology#Love Hornbills Day

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The largest living species of horseshoe crab dramatically surpasses the largest living spiders. Tachypleus tridentatus, the largest of this group, can reach sizes of 31 inches (79.5 cm) and weigh as much as 9 pounds (4 kilograms), according to research published in 2017 in the Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity(opens in new tab).

Image credit: Jaap Bleijenberg / Alamy

#jaap bleijenberg#photographer#alamy#horseshoe crab#crab#marine photography#tachypleus tridentatus#journal of asia-pacific biodiversity#nature#animal

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flowers Strips Bring All the Pollinators to the Yard

Flowers Strips Bring All the Pollinators to the Yard

The longer I garden the more I gravitate towards creating habitats for creatures that rely on plants for survival. I’ve always been more interested in functional gardens rather than gardens that are simply “plants as furniture” (as Sierra likes to say) – a manicured, weed-free lawn, a few shrubs shaped into gumdrops, sterile flowers for color – and that interest has grown into a way of life. A…

View On WordPress

#bees#biodiversity#bumblebees#cities#flowers#ground nesting bees#habitat gardens#insects#Jeff Ollerton#Journal of Hymenoptera#Munich#pollinating insects#pollinator gardens#pollinators#urban areas

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Launching a new journal: Biological Diversity

I’m happy to announce the launch of a new, not-for-profit, journal, Biological Diversity. It is published on behalf of South China Botanical Garden by the respected academic publisher, Wiley, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/29944139

Biological Diversity is a new, open access journal specializing in research that explores biodiversity conservation and the sustainable use of resources. It…

View On WordPress

#agriculture#biodiversity#biological diversity#Climate Change#diversity#editing#editor#environment#journals#publishing#rewilding

0 notes

Text

Mexican scientist, Gerardo Ceballos, winner of the 16th edition BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards in Ecology and Conservation Biology

The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Ecology and Conservation Biology has gone in this sixteenth edition to two Mexican scientists who have documented and quantified the scale of the Sixth Mass Extinction, that is, the massive loss of biodiversity brought about by human activity. Gerardo Ceballos (National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM) and Rodolfo Dirzo (Stanford University) are hailed by the committee as “trailblazing researchers in ecological science and conservation,” whose joint work in Latin America and Africa “has established that current species extinction rates in many groups of organisms are much higher than throughout the preceding two million years.” In effect, by documenting losses of animals and plants in some of the Earth’s most biodiverse habitats, both have contributed to showing that today’s biodiversity crisis is, as the citation states, “an especially rapid period of species loss occurring globally and across all groups of organisms, and the first to be tied directly to the impacts of a single species, namely, us.”

The two awardee ecologists have catalyzed the global study of “defaunation,” a term Dirzo coined to describe the alterations causing the disappearance of animals in the structure and function of ecosystems. His research, says the citation, has revealed how the elimination of a single species can trigger pernicious “cascading effects” by disrupting the web of interactions it maintains with other organisms. This, in turn, has adverse effects on human wellbeing through the reduction of the goods and services they perform. His work has helped provide the “necessary scientific basis” to further the adoption of evidence-led conservation measures.

“The experimental work done by professors Ceballos and Dirzo has led the way in quantifying the extent of species loss,” explains a Research Professor in the Department of Integrative Ecology at Doñana Biological Station (CSIC) and secretary of the award committee. “And what is truly shocking about their results is that this species extinction rate, or ‘defaunation process’, as it is known, is advancing today at a speed several orders of magnitude above the rate recorded over the last two million years. This shows that we are up against a truly intimidating challenge; one that these two researchers have documented and assessed across thousands of vertebrate, invertebrate and plant species.”

Another committee member, a Research Professor in the Department of Biogeography and Global Change at the National Museum of Natural Sciences (CSIC) in Madrid, uses an analogy to highlight the importance of the awardees' work: “Imagine we are flying in a plane sitting next to the window. And looking out, we see bits of the plane falling off. It may not nosedive straight away, but the first thought that crosses the passenger’s mind is: how long can this plane keep flying without its component parts? Something similar occurs with ecosystems. As they lose their “parts'' or species, they also lose vital functions, and it is these functions that provide essential services. The work of Dirzo and Ceballos is a valuable addition to the understanding of how such losses affect the resilience and sustainability of our ecosystems, shedding light on the urgent need for conservation actions to preserve the integrity of these systems that are critical to our survival.”

An accelerating extinction rate driven by our own species

Ceballos and Dirzo's endeavors have advanced in tandem through most of their professional careers, with results in many cases complementing one another’s. But the origin of their collaboration lies back in the early 1980s, when both were studying at the University of Wales (United Kingdom), Dirzo pursuing his doctorate courses and Ceballos completing his master’s degree. They first connected over their shared concern at the increasingly evident impact on nature of human activity. “We started having conversations not just on scientific matters, but about how worried we were about the anthropogenic impact on the natural world we were seeing all around us,” Dirzo recalls.

Further ahead, Ceballos turned his research attention to the study of wildlife and the magnitude of the advancing extinction, while Dirzo centered his efforts on ecological interactions between plants and animals, and the consequences of this extinction.

Ceballos’ work on assessing current rates of extinction led him to explore comparisons with the rates of the past. “Evolution operates as a process of species extinction and generation,” he relates. In normal periods, more species appear than disappear, such that diversity gradually expands. There have been five mass extinction events in the last 600 million years, the last of which brought the demise of the dinosaurs. All had in common that they were catastrophic – wiping out 70% or more of the world’s species – had their origins in natural disasters, like a meteorite collision, and were extremely rapid in geological terms, lasting hundreds of thousands or millions of years.”

After a detailed analysis of numerous species, a research team led by Ceballos concluded – in a paper published in Science Advances in 2015 – that vertebrate extinction rates are from 100 to 1,000 times greater than those prevailing over the last few million years. “What this means is that the vertebrate species that have died out in the past 100 years should have taken 10,000 years to become extinct. That is the magnitude of the extinction,” he explains. His work pointed one way only; to the fact that the sixth mass extinction was already upon us, a scenario that for Ceballos has three major implications: “The first is that we are losing all that biological history. The second is that we are losing living creatures that have accompanied us through time and have been key in driving forward human evolution. And the third is that all these species are assembled in ecosystems that provide us with the environmental services that support life on Earth, like the right combination of gases in the atmosphere, drinking water, fertilization… Without these environmental services civilization as we know it cannot be sustained.”

The grave impact of extinction on ecosystem services

Species extinction is the last stage in the process, but Ceballos insists that population extinction is no less worrying, since it is these populations that provide environmental services on a local or regional scale. He gives an example: “It doesn’t matter if there are jaguars in Brazil if they have died out in Mexico, because the environmental services they performed in Mexico will have disappeared with them.”

Ceballos and his colleagues explored this concept in a study of prairie dog populations, which in the 1990s were thought to be pests and were the target of eradication campaigns. Through this study, published in 1999 in the Journal of Arid Environments, they were able to prove that, rather than pests, they actually play a vital role in maintaining their ecosystem, the grasslands of the southwest of the United States and north of Mexico.

“We found that prairie dogs were essential to the upkeep of ecosystem services, because if they are lost it sets off a chain of extinctions across the many other species who depend on them.” With these rodents gone, the soil becomes less fertile, erosion increases and the scrubland advances, wiping out the plants that serve as forage for livestock. “The impact on environmental services is colossal,” he affirms.

For the Mexican ecologist, the biodiversity crisis we are experiencing is of a magnitude similar to the crisis of climate change and both problems are closely interrelated: “We have to couple the issue of species extinction with the issue of climate change, and understand that it is a threat to humanity’s future.”

From deforestation to “defaunation”: the “cascading effect” of species loss

Rodolfo Dirzo states, "I was soon asking myself: these fascinating things I study, the ecology and evolution of plants and animals and their interactions, may not be around to study in future if we don’t start to do something about what is happening to natural systems.” This concern, which he shares with Ceballos, has guided Dirzo’s steps throughout his career, from Mexico to the United States.

By analogy with deforestation, he came up with the term “defaunation” to refer to the imbalance entailed by the absence of animals. “Everyone has a mental picture when they hear the word deforestation. They understand that what they are seeing is a problem, the erosion of ecosystems due to loss of vegetation. And it occurred to me that the word “defaunation” could be a way to highlight that, just as Earth’s ecosystems face a serious problem of deforestation, another serious threat lies in the depletion and possible extinction of animal species.”

The scientist began studying the effects of this phenomenon and published his findings in a chapter of the book Plant-Animal Interactions: Evolutionary Ecology in Tropical and Temperate Regions in 1991.

“Species do not live in an ecological vacuum,” he points out, insisting that it is not just species disappearances we have to worry about, but the extinction of species populations and, above all, species interactions, which should accordingly be a core focus of conservation actions.

Elephant poaching and the risk of pandemics

These effects, Dirzo explains, give rise to a phenomenon that he refers to as “winners and losers.” When these large animals die out locally, they are evidently losers, while smaller animals like rodents take advantage of their absence and therefore become winners. But these smaller animals also carry pathogens like Leptospira, Leishmania and even the bacteria that causes bubonic plague. So if populations of these pathogen-carrying animals increase, there is a greater chance that they will transmit diseases to humans. “We could be put at risk of suffering a new pandemic,” he affirms, “given the proliferation of these diseases and the current mobility of human beings.”

The researcher has verified these effects through experiments carried out in Africa. He and his team installed electrified fences in some very well-conserved parts of the savannah to stop large animals from entering. They then left other areas unfenced, so they could compare two identical ecosystems, one with large wildlife and one without. “We found that when an area is closed off to these animals, the savannah vegetation changes dramatically.” Further, the rodent population triples, as does the risk of diseases that can be transmitted to humans. In this way, he says, we get “a cascade that runs from elephant poaching to the real risk of a new human pandemic.”

In fact, it is not even necessary for a whole local population to die out for it to pose an ecological problem. If there are not enough individuals to maintain viable populations, the species in question can no longer interact with other organisms and fulfill its ecosystem function. It becomes what is known, says Dirzo, as a “living dead species.”

Hunting is just one human activity that can drive species populations totally or partially extinct and trigger such grave effects as a pandemic. Dirzo lists five key factors that drive defaunation: land use change for pasture or urban development; the overexploitation of resources; pollution – by anything from noxious chemical products to marine plastic waste; the introduction of non-native or invasive species in ecosystems where they don’t belong; and climate change. “But none of these five factors,” he adds, “operates in isolation: they are all interlinked, and this makes the challenge of dealing with biological extinction all the more complex.”

Laureate bio notes

Gerardo Ceballos (Toluca, Mexico, 1958) graduated in biology from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (Mexico) and went on to earn master’s degrees from the University of Wales (United Kingdom) and the University of Arizona (United States), where he received his PhD in 1988. The following year, he took up a position at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where he is currently a Senior Researcher at the Institute of Ecology. He is the author of 55 books and numerous scientific papers, and some 200 applied studies in conservation and management that have featured in technical reports supported by institutions like the World Bank, the U.S. Agency for International Development or the State of Mexico Government. He is one of the forces behind Mexico’s endangered species legislation and the designation of over 20 natural protected areas covering more than 1.5 million hectares.

Rodolfo Dirzo (Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1951) completed a BSc in Biology at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (Mexico) then went on to obtain an MSc and PhD from the University of Wales (United Kingdom). Between 1980 and 2004 he held various teaching and research positions at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), serving as a professor, Director of the Los Tuxtlas Biological Station and Chair of the Department of Evolutionary Ecology. In 2004 he joined the faculty at Stanford University, where he is currently Bing Professor in Environmental Science, Professor of Earth System Science, Senior Fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment and Associate Dean for Integrative Initiatives in Environmental Justice. Dirzo has also taught in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Puerto Rico.

Nominators

A total of 47 nominations were received in this edition. The awardee researchers were nominated by Gretchen Cara Daily, Bing Professor of Environmental Science at Stanford University (United States) and 2018 Frontiers of Knowledge Laureate in Ecology and Conservation Biology.

#🇲🇽#STEM#Gerardo Ceballos#Rodolfo Dirzo#extinction#animal#plants#Science Advances#ecosystems#BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards in Ecology and Conservation Biology#prairie dog#Journal of Arid Environments#livestock#climate chaange#biodiversity#defaunation#National Autonomous University of Mexico#UNAM#deforestation#elephant#pandemic#africa#living dead species#rodent#elephant poaching#hunting#Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa#Institute of Ecology#world bank#U.S. Agency for International Development

1 note

·

View note

Text

Climat et Biodiversité au Bénin : l’ONG Save Our Planet pour une citoyenneté active

La 4e édition tant attendue de la Conférence Citoyenne pour le Climat et la Biodiversité au Bénin, organisée par l’ONG Save Our Planet, s’est ouverte le samedi 9 décembre 2023, à l’université d’Abomey-Calavi. Cet événement a rassemblé des citoyens engagés, des experts et des organisations de la société civile renommées.

En prenant la parole à l’ouverture de la conférence, Megan Valère SOSSOU,…

View On WordPress

#BENKADI BENIN#Conférence Citoyenne pour le Climat et la Biodiversité#JEVEV ONG#Journal Santé Environnement#LABIS Porto-Novo#Lemuel Express#ODDB ONG#ONG Save Our Planet#ONG SOS Biodiversity#PASCiB#RAMEC#Solidarité Laîque#VOA Citoyenne

0 notes

Text

I had a dream someone told me about these genetically modified not-crabs (as in selectively bred from crabs and other crustaceans very similar to crabs enough to be able to produce offspring capable of reproduction with them but not the same exact thing) that were made to genetically weed out crabs developing the beginnings of bony nasal passages (this was apparently something that would later become a fatal condition that put the world's crab population at risk)

My friend who works in national parks showed me a picture explaining why they're really cool but the picture had been edited for people with carcinophobia, so their claws were photoshopped over by fake white background pngs of oven mitts and they were haphazardly spot correction tooled to have shaggy black fur and were each labelled "DOGS" in big white 22pt calibri font

0 notes

Text

Promoting Literacy through Nature: Building Sustainable and Peaceful Societies

View On WordPress

#FriendsAreas#@FriendsAreas#accessible#biodiversity#books#Climate Action#climate change#conservation#environmental themes#environmental topics#fauna#flora#Friends of the Saskatoon Afforestation Areas Inc.#George Genereux Urban REgional Park#guided nature walks#inclusive#journalling#learning#literacy#mentorship#Nature#One City#poetry#resources#Richard St. Barbe Baker#Richard St. Barbe Baker AFforestation ARea#Saskatchewan#Saskatoon#SCHOOLS#senses

0 notes

Text

In 2020, for the first time since being laid in 1772, a section of a King’s College lawn the size of just half a football pitch was not mown.

Instead, it was transformed into a colourful wildflower meadow filled with poppies, cornflowers and oxeye daisies.

[Researcher Dr Cicely Marshall] found that as well as being a glorious sight, the meadow had boosted biodiversity and was more resilient than lawn to our changing climate. The results are published today in the journal Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

Despite its size, the wildflower meadow supported three times more species of plants, spiders and bugs than the remaining lawn - including 14 species with conservation designations, compared with six in the lawn.

The meadow was found to have another climate benefit: it reflected 25% more sunlight than the lawn, helping to counteract what’s known as the ‘urban heat island’ effect. Cities tend to heat up more than rural areas, so reflecting more sunlight can have a cooling effect - useful in our increasingly hot summers.

“Cambridge has become more prone to drought, and last summer most of the College’s fine lawns died. It’s really expensive to maintain these lawns, which have to be re-sown if they die off. But the meadow just looked after itself,” says Marshall.

#Down With Lawns#the article has a bunch more including tips on starting your own meadow#environmental news

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

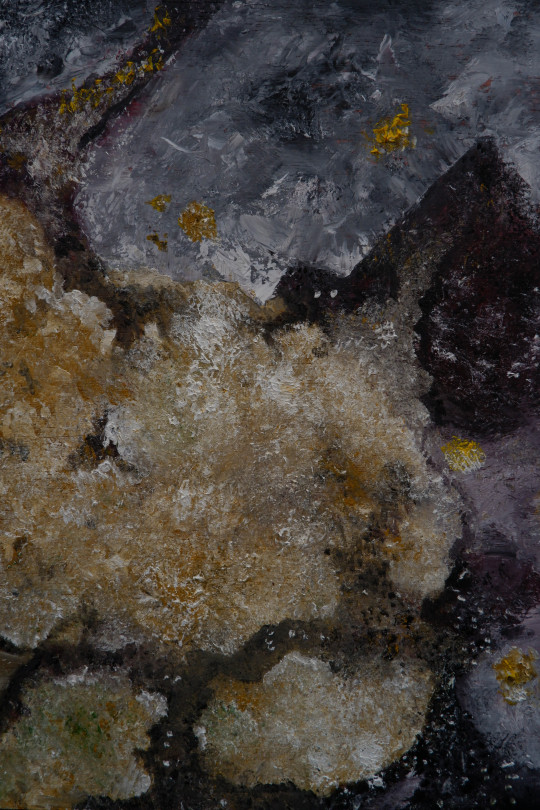

Staithes Biodiversity 2024, Oil paint on recycled wood

Based on the photographs I took whilst visiting Staithes, North Yorkshire.

#travel#travel journal#memories#north yorkshire#beachfront#biodiversity#journal#nature#marine life#yorkshire#nature is beautiful#nature lovers#sea life#seaside#sea creatures#painting#oil painting#art#artwork#my art#texture

1 note

·

View note

Text

Insular dwarfs and giants more likely to go extinct

Newswise — Leipzig/Halle. Islands are “laboratories of evolution” and home to animal species with many unique features, including dwarfs that evolved to very small sizes compared to their mainland relatives, and giants that evolved to large sizes. A team of researchers from the German Centre of Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) has now…

View On WordPress

#All Journal News#Environmental Science#Extinction;biodiversity loss;Megafauna#German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig#Newswise#Paleontology#Wildlife

0 notes

Text

Here, have a spark of hope.

The reality is that no single person can fix the entirety of the current ecological imbalance that has been literally centuries in the making at this point. Yet there are so, so many of us who care, and who are doing what we can to make a difference in whatever every day to day ways we're able. I often think of conservation efforts like the Loren Eiseley story "The Star Thrower" (aka, "the starfish story"). Amid a beach full of stranded starfish, one person cannot possibly save them all, but they can spend what time they have saving those they're able.

And this study shows that these efforts do, in fact, make a difference, not just for starfish but a myriad of species. This meta-analysis of almost 200 studies definitively proves that conservation preserves and restores biodiversity, keeping more species from going extinct. It's all too easy to get entangled in the losses, but we even more need to allow ourselves to celebrate the wins.

That success is crucial to convincing governmental entities and other stakeholders that putting funds toward conservation efforts makes a significant difference and is not only worth the investment, but worth increasing. And, on a personal level, it's necessary for those of us who care so deeply for this world to know when our efforts are having an impact, to buoy us up when the anxiety and grief over ecological destruction wears us down.

There is hope. Keep it up, folks; it's helping <3

#conservation#environment#environmentalism#extinction#endangered species#animals#wildlife#biodiversity#nature#science#scicomm#hope#solarpunk#hopepunk#hopecore#hopeposting#optimism#ecology#habitat restoration#restoration ecology

495 notes

·

View notes

Text

Humans are so cute. They think they can outsmart birds. They place nasty metal spikes on rooftops and ledges to prevent birds from nesting there.

It’s a classic human trick known in urban design as “evil architecture”: designing a place in a way that’s meant to deter others. Think of the city benches you see segmented by bars to stop homeless people sleeping there.

But birds are genius rebels. Not only are they undeterred by evil architecture, they actually use it to their advantage, according to a new Dutch study published in the journal Deinsea.

Crows and magpies, it turns out, are learning to rip strips of anti-bird spikes off of buildings and use them to build their nests. It’s an incredible addition to the growing body of evidence about the intelligence of birds, so wrongly maligned as stupid that “bird-brained” is still commonly used as an insult...

Magpies also use anti-bird spikes for their nests. In 2021, a hospital patient in Antwerp, Belgium, looked out the window and noticed a huge magpie’s nest in a tree in the courtyard. Biologist Auke-Florian Hiemstra of Leiden-based Naturalis Biodiversity Center, one of the study’s authors, went to collect the nest and found that it was made out of 50 meters of anti-bird strips, containing no fewer than 1,500 metal spikes.

Hiemstra describes the magpie nest as “an impregnable fortress.”

Pictured: A huge magpie nest made out of 1,500 metal spikes.

Magpies are known to build roofs over their nests to prevent other birds from stealing their eggs and young. Usually, they scrounge around in nature for thorny plants or spiky branches to form the roof. But city birds don’t need to search for the perfect branch — they can just use the anti-bird spikes that humans have so kindly put at their disposal.

“The magpies appear to be using the pins exactly the same way we do: to keep other birds away from their nest,” Hiemstra said.

Another urban magpie nest, this one from Scotland, really shows off the roof-building tactic:

Pictured: A nest from Scotland shows how urban magpies are using anti-bird spikes to construct a roof meant to protect their young and eggs from predators.

Birds had already been spotted using upward-pointing anti-bird spikes as foundations for nests. In 2016, the so-called Parkdale Pigeon became Twitter-famous for refusing to give up when humans removed her first nest and installed spikes on her chosen nesting site, the top of an LCD monitor on a subway platform in Melbourne. The avian architect rebelled and built an even better home there, using the spikes as a foundation to hold her nest more securely in place.

...Hiemstra’s study is the first to show that birds, adapting to city life, are learning to seek out and use our anti-bird spikes as their nesting material. Pretty badass, right?

The genius of birds — and other animals we underestimate

It’s a well-established fact that many bird species are highly intelligent. Members of the corvid family, which includes crows and magpies, are especially renowned for their smarts. Crows can solve complex puzzles, while magpies can pass the “mirror test” — the classic test that scientists use to determine if a species is self-aware.

Studies show that some birds have evolved cognitive skills similar to our own: They have amazing memories, remembering for months the thousands of different hiding places where they’ve stashed seeds, and they use their own experiences to predict the behavior of other birds, suggesting they’ve got some theory of mind.

And, as author Jennifer Ackerman details in The Genius of Birds, birds are brilliant at using tools. Black palm cockatoos use twigs as drumsticks, tapping out a beat on a tree trunk to get a female’s attention. Jays use sticks as spears to attack other birds...

Birds have also been known to use human tools to their advantage. When carrion crows want to crack a walnut, for example, they position the nut on a busy road, wait for a passing car to crush the shell, then swoop down to collect the nut and eat it. This behavior has been recorded several times in Japanese crows.

But what’s unique about Hiemstra’s study is that it shows birds using human tools, specifically designed to thwart birds’ plans, in order to thwart our plans instead. We humans try to keep birds away with spikes, and the birds — ingenious rebels that they are — retort: Thanks, humans!

-via Vox, July 26, 2023

#birds are literally learning how to better live/survive alongside us#this is like. actually kind of remarkable. and the technique is spreading including to other species.#is this hopepunk? it kinda feels like hopepunk to me.#animals are literally learning how to use our attempts to get rid of them against us#that's kind of amazing#and also VERY encouraging re: life's innate resilience#crows#magpie#corvid#crow#bird#bird nest#bird nerd#bird news#adaptation#urban animals#ornithology#climate adaptation#kinda#good news#hope#hope posting#hopepunk#animal intelligence#wildlife#animals are awesome

1K notes

·

View notes