#Journal of Hymenoptera

Text

Flowers Strips Bring All the Pollinators to the Yard

Flowers Strips Bring All the Pollinators to the Yard

The longer I garden the more I gravitate towards creating habitats for creatures that rely on plants for survival. I’ve always been more interested in functional gardens rather than gardens that are simply “plants as furniture” (as Sierra likes to say) – a manicured, weed-free lawn, a few shrubs shaped into gumdrops, sterile flowers for color – and that interest has grown into a way of life. A…

View On WordPress

#bees#biodiversity#bumblebees#cities#flowers#ground nesting bees#habitat gardens#insects#Jeff Ollerton#Journal of Hymenoptera#Munich#pollinating insects#pollinator gardens#pollinators#urban areas

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

I heard Beaver schnapps and I am now obliged to inform you of a different quirky Swedish spirit: ant schnapps, which builds on a long tradition of red wood ants and their formic acid being used in Swedish folk medicine. Carl Michael Bellman (1740-1795), a central figure in Swedish poetry, mentions ant schnapps in his work. Just goes to show that in spite of current taboos, Europeans aren't complete strangers to entomophagy, there are various other instances of insects being consumed historically and contemporarily in Europe

I did not know that! Thank you.

I now have an article to read:

740 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know that measuring the intelligence of animals is a stupidly complicated thing, but in general, what types of insects show more intelligent behaviors? Building or organizing complex structures or groups, planning long term, understanding complex situations or objects, etc.

I assume ants top the list, but any other standouts?

This is real life facts, not HBG lore, but...

Ants and bees are both extremely intelligent, even standing out among non-insects--ants can recognize themselves in mirrors, which few mammals can, and bees can solve puzzles pulling on strings to get treats that cats struggle with.

Roaches are another contender. They can't hear, but can be taught to come and go using vanilla and peppermint scents as commands!

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

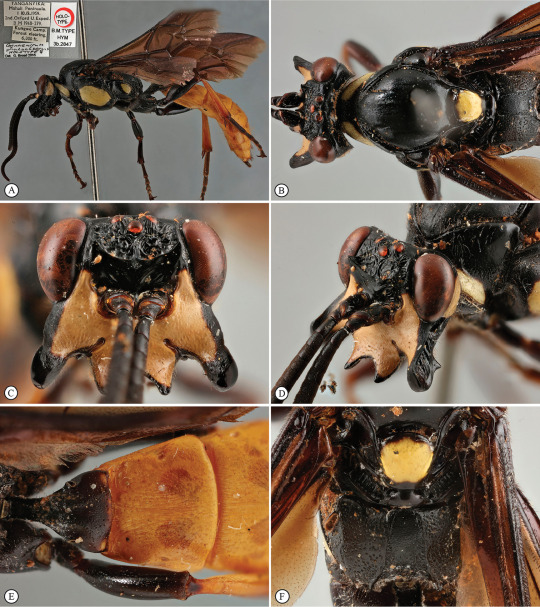

I think Genaemirum phacochoerus wins the award for weirdest Ichneumonid face ever!!!!! THIS IS WHY WASPS ARE THE BEST! The epithet actually means "warthog"!

I need to draw this wasp like..... yesterday!!!!

#Genaemirumpacochoerus#Ichneumonidae#Ichneumoninae#Wasp#Wasps#Weird#MindBlown#Apocrita#Parasitica#Hymenoptera

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invert fact #1: Fairy Flies!

Fairy Flies may be named flies, but are actually a genus of parasitoid wasps, known for encompassing both the smallest insect and smallest flying insect in the world.

The smallest flying insects, being from a genus named Kikiki, contains one single species; Kikiki huna. Some K. huna individuals have been recorded being only 150 μm! (0.15 mm). They are the smallest flying insects known (as of 2019).

Well, how about the smallest non-flying insects? Specifically, males in the genus D. echmepterygis. These boys only average 186 μm (0.186 mm), shorter than some amoebas and bacteria! They are also blind, lack wings and are tiny in comparison to females of the same species, which range closer to 550 μm (0.55 mm)

Citings for nerds (including image citations) and extra notes:

Huber J, Noyes J (2013) A new genus and species of fairyfly, Tinkerbella nana (Hymenoptera, Mymaridae), with comments on its sister genus Kikiki, and discussion on small size limits in arthropods. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 32: 17-44. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.32.4663.

Welcome to Invert facts! I am unsure how frequently I will post to this blog, but I do hope you enjoy its content. I may expand things in the future if the blog gets enough attention, but we will see how stuff goes!

#MantisMage's Invert facts#Entomology#insects#wasps#fairy flies#Invert facts#invertebrates#bugblr#biology#zoology

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New species of the stingless bee genus Plebeia (Hymenoptera: Apidae), Michael S. Engel, University of Kansas & American Museum of Natural History, Journal of Melittology

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le spinosad comme approche biologique potentielle dans la lutte contre la fourmi d'argentine dans les vergers d'agrumes californiens

See on Scoop.it - EntomoNews

Les effets du spinosad dans la lutte contre la fourmi d'argentine. Le spinosad serait une alternative au dangereux thiamétoxame (Cruiser)

Dictionnaire amoureux des fourmis - Nouveautés décembre 2023

Mis à jour le 02-Jan-2024

J. Applied Entomol, 1-11. 10.1111/jen.13203

Milosavljevic, I., N. Irvin, M. Lewis and M. Hoddle (2023).

-------

NDÉ

L'étude

Spinosad‐infused biodegradable hydrogel beads as a potential organic approach for argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Mayr) (hymenoptera: Formicidae), management in California citrus orchards - Milosavljević - Journal of Applied Entomology - 06/12/2023 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jen.13203

Traduction

Billes d'hydrogel biodégradable infusées de spinosad comme approche biologique potentielle pour la gestion de la fourmi argentine, Linepithema humile (Mayr) (hymenoptera : Formicidae), dans les vergers d'agrumes californiens.

[Image] Argentine ant workers overwhelming a competing ant species in a citrus orchard. Photo credit: Mike Lewis, UC Riverside.

via Argentine Ants | Applied Biological Control Research

https://biocontrol.ucr.edu/argentine-ants

Bernadette Cassel's insight:

https://www.scoop.it/topic/entomonews?q=spinosad

0 notes

Photo

Field journal 📔 ID: Ellipsoptera (Either E. hamata or E. marginata) Common name: Tiger beetle (either coastal tiger beetle or margined tiger beetle) 🪲 Seeing the recent @inaturalistorg post of Cicindela chinensis japonica is giving me tiger beetle envy because that one is way prettier than the species of tiger beetles we have here in Florida. 🪲 However, our Florida tiger beetles aren’t completely boring. While I wasn’t able to find out specific information about this species I observed a few summers ago, tiger beetles in general do have interesting behavior, and some of our local species possess unique traits. 🪲 Tiger beetles (of which there are 2,600 known species—but just about 100 in the US) got their name because they are very active, moving quickly and hunting aggressively. The fastest species can run up to 5 miles an hour, which is the equivalent of a human running 480 miles per hour. In fact, despite having extremely sharp vision for an insect, the tiger beetle can run so fast that it blinds itself. 🪲 They are opportunistic feeders and are most often seen eating ants but will kill and eat any insect or spider they can catch. They are great predators. Their speed and other traits also prevent them from becoming prey a lot of the time. 🪲 One defense mechanism tiger beetles display is releasing a chemical spray. The spray from one of our local tiger beetle species has been described as smelling like Juicy Fruit gum! 🪲 Another unique defense mechanism that they have keeps them safe from bats. They’re some of the few insects we know about that can detect and respond to echolocation! 🪲 This isn’t to say that tiger beetles are invincible. They are preyed upon by robber flies and can be parasitized by a few Diptera and Hymenoptera species. Furthermore, some species are threatened, sometimes to the point of extinction, by human activity. 🪲 Observed in Manatee County, Florida 🐅 🪲 🔍 #florida #bug #insect #beetle #tigerbeetle #macro #nature #naturelovers #nature_brilliance #fiftyshades_of_nature #ellipsoptera #coleoptera#coastaltigerbeetle #marginedtigerbeetle #ellipsopterahamata #ellipsopteramarginata #bradenton #bradentonarea (at Bradenton, Florida) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce6tc-QO6ro/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#florida#bug#insect#beetle#tigerbeetle#macro#nature#naturelovers#nature_brilliance#fiftyshades_of_nature#ellipsoptera#coleoptera#coastaltigerbeetle#marginedtigerbeetle#ellipsopterahamata#ellipsopteramarginata#bradenton#bradentonarea

0 notes

Link

#ants#myrmecology#tool use#Aphaenogaster#aphaenogaster subterranea#insecta#insect#hymenoptera#behavioural ecology#science#journal#oxford university press#article#scientific article#personal#lonelymyrmecologyst#i am an author in this#proud#coauthor

1 note

·

View note

Link

The rare native Australian bee, Pharohylaeus lactiferus, was seen in a rainforest near Atherton in far north Queensland, previously thought to have been extinct with the latest recorded sighting in 1923.

The research has been published in The Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

#bees#entomology#zoology#animals#insects#hymenoptera#james dorey at it again#hes everything i wish i could be in a bee scientist

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

[The name [Tobleronius] refers to the chocolate brand “Toblerone”, one of the favourites of the first author. The shape of T2 looks like one of the triangles that compose Toblerone bars (if one has enough imagination and love for chocolate!). Here is hoping that someday a wasp-shaped chocolate bar is produced.]

(the paper also include a genus Ohenri that is a reference to a different candy bar)

Fernandez-Triana J, Boudreault C (2018) Seventeen new genera of microgastrine parasitoid wasps (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) from tropical areas of the world. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 64: 25-140.

https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.64.25453

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, apparently ants can pass the mirror test (they'll clean off a blue dot on their head if they see themselves in a mirror, but react to no other ant's reflection, showing that they recognize themselves). I didn't think they could even see well enough to pass the mirror test (even flying insects being generally pretty near-sighted). I didn't even know they could see color!

Same species (Myrmica sabuleti) the large blue butterfly preys on, too--that is, the caterpillar that pretends to be an ant larva, so it can eat ant larvae. The caterpillar actually mimics sound--so this is also a rare insect that relies on hearing to some degree.

And this on top of ants having a phenomenal sense of smell, much better than most insects, who already rely on smell so much to begin with. Why is M. sabuleti hogging all the insect senses??

Source: Cammaerts, M., & Cammaerts, R., 2015. Are Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Capable of Self Recognition? Journal of Science.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not since 1923 have scientists gazed upon the Australian cloaked bee. That is, until recently when scientists located a few populations in the wild. But its rediscovery comes as a mixed blessing owing to its potentially threatened status.

Six. That’s it—just six.

Only six individuals of this species, Pharohylaeus lactiferus, have ever been seen until recently, and none since 1923, when one of these handsome fellows was spotted in Queensland, Australia. These rare bugs are commonly referred to as cloaked bees on account of their cloak-like abdominal segments.

Scientists, fearful that the species had gone the way of the dodo, launched a last-gasp investigation to find out. The good news is that some specimens were actually spotted, but the bad news is that they’re likely in really big trouble on account of extensive habitat loss. Entomologist James Dorey, a PhD student at Flinders University, is the lone author of a new paper describing the re-discovery of this species, which now appears in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

“It’s not often you get to cast your eyes on a creature feared to be long-gone,” wrote Dorey in a commentary published at the Conversation. “I found the cloaked bee P. lactiferus during a major east coast sampling effort of more than 225 unique sites. The discovery, and what I learnt from it, helped me find more specimens at two additional sites.”

In total, Dorey managed to find three populations of cloaked bees in New South Wales and Queensland, and he found them by sampling their favorite plant species.

“I only found P. lactiferus on two types of plant: the firewheel tree and the Illawarra flame—both of which boast exuberant red flowers,” he wrote.

All cloaked bees spotted by Dorey were found within 660 feet (201 meters) of these plants, which are only found in tropical or subtropical rainforests. The bees paid attention to these plants at the “exclusion of other available floral resources,” indicating possible floral and habitat specialization, according to the paper.

These results are concerning as it suggests the bees are suffering from population isolation; Dorey attributes the rarity of these bees to a highly fragmented habitat and the bees’ preference for these two plants. The habitat specialization of the cloaked bee suggests it has an “above-average level of vulnerability to disturbances, particularly if it needs a strict set of requirements to make it through its entire life-cycle,” wrote Dorey at the Conversation.

That habitat loss is a major factor here is hardly surprising. Australia has lost 40% of its forest and woodland areas since the onset of European colonization. And as the new research points out, the bees are particularly vulnerable to bushfires. That’s upsetting news given how vulnerable Australia is to bushfires, as witnessed by the devastating fires of 2019-20 that, among other things, wiped out or impacted an estimated 3 billion animals and destroyed sites sacred to Indigenous groups that also filled important ecological functions. Bushfire risk is also rising as the climate heats up, making catastrophic fire conditions more likely.

Australia hosts 1,654 named species of native bee. The potential loss of the cloaked bee is significant, however, in that it’s the lone representative of an entire genus: Pharohylaeus.

Now, it’s possible that more cloaked bees are buzzing around Australia, including in places scientists aren’t looking, such as the rainforest canopy. But that’s a potential problem, said Dorsey, as rainforests are “notoriously hard to sample.”

“P. lactiferus persists, which is wonderful,” he wrote. “Unfortunately, we can’t yet say whether or not it is threatened.”

What’s required, he says, is a “robust, extensive and targeted survey regime.” Only then will we know the true status of these rare and beautiful insects.

#rediscovery#bee#science#nature#animals#biodiversity#conservation#environment#wildlife#insect#australia#australian wildfires#endangered species#extinction#cloaked bees#pollinators#hemiptera#entomology

94 notes

·

View notes

Link

A group of solitary bees known as Svastra duplocincta. Males of this species gather together at night to roost and sleep upon plants, grasping them with their mandibles so they don’t fall off. PHOTOGRAPH BY BRUCE D TAUBERT

Excerpt from this story from National Geographic:

In the midst of the Chihuahuan Desert, straddling the border of southeastern Arizona and Sonora, Mexico, the San Bernardino Valley is an oasis of life. Following rains, especially the monsoon downpours of late summer, the area explodes with an abundance of flowers—and a bevy of bees. In fact, research by entomologist Bob Minckley shows that this area has the highest concentration of bee species in the world.

In a recent paper published in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research, Minckley and San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge manager Bill Radke found that 497 species of bees live within just over six square miles of the valley, a modest area for such a study, 10 times smaller than Washington D.C.

To put that in context, these 497 species represent 14 percent of all the nearly 4,000 bee species found in the United States—and that’s more than are found in all of New York state (and most other states), he adds.

This valley is fed by fossil water, which over thousands of years seeps south from the Chiricahua Mountains to feed gushing artesian wells, filling ponds and creeks lined with cottonwood trees and hundreds of varieties of flowering plants. Large creatures such as mountain lions, bobcats, javelina, and other mammals roam the land—and birders often visit to see some of the rare species that fly through. The Arizona side is made up of San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, and in Sonora, much of the valley is owned by Cuenca Los Ojos, a binational conservation organization.

This hot spot of bee diversity faces several threats. In 2020, the Trump Administration built 30-foot-high steel fencing along the entire border of San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, part of the 200-plus miles of border wall put up in Arizona alone. (Learn more: Sacred Arizona spring drying up as border wall construction continues.)

The wall’s construction caused an immediate and sustained reduction in the movement of animals, according to preliminary data from a series of camera traps, Traphagen says. But the most ecologically damaging aspect may be the massive quantities of water withdrawn from the refuge’s aquifer to make concrete for the base of the wall. After groundwater pumping began, several ponds went dry, leading to a state of emergency at the refuge in which staff had to relocate endangered fish, and install artificial pumps to keep ponds full. These small water bodies are home to eight species of rare desert fish, four of them endangered and found nowhere else in the United States.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is one of the funniest scientific articles I have read, from the creator of the Schmidt sting pain index about the tarantula hawk’s venom:

“Few, if any, people would be stung willingly by a tarantula hawk. I know of no examples of such bravery in the name of knowledge, for the reputation of pompilid wasps—and tarantula hawks in specific—is well known among the biological community. All stings experienced occurred during a collector’s enthusiasm in obtaining specimens and typically resulted in the stung person uttering an expletive, tossing the net into the air and screaming—such was the immediate pain. To the author the pain was instantaneous, electrifying, excruciating, and totally debilitating... Advice I have given in speaking engagements was to ‘lay down and scream’. The reasoning being that the pain is so debilitating and excruciating that the victim is at risk of further injury by tripping in a hole or over an object in the path and falling onto a cactus or into a barbed wire fence. Such is the pain, that few, if any, can maintain normal coordination or cognitive control to prevent accidental injury. Screaming is a satisfying expression that helps reduce attention to the pain of the sting itself. Once, in his dedication to the investigation of wasps, Howard Evans netted perhaps 10 tarantula hawk females from a flower and enthusiastically reached into the insect net to retrieve them. Undeterred after the first sting, he continued, receiving several more stings, until the pain was so great he lost all of them and crawled into a ditch and just bawled his eyes out.”

Justin O. Schmidt. (2004). Venom and the Good Life in Tarantula Hawks (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae): How to Eat, Not Be Eaten, and Live Long. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 77(4), 402.

#I wanted to post this on other social media but I can't figure out which would be a good one lgksjkleg#so I'm putting this here instead#bugs#insects#long post

9 notes

·

View notes