#Rodolfo Dirzo

Text

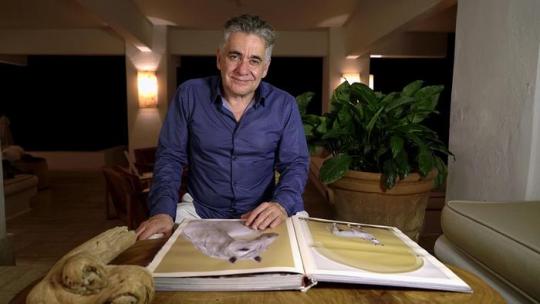

Mexican scientist, Gerardo Ceballos, winner of the 16th edition BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards in Ecology and Conservation Biology

The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Ecology and Conservation Biology has gone in this sixteenth edition to two Mexican scientists who have documented and quantified the scale of the Sixth Mass Extinction, that is, the massive loss of biodiversity brought about by human activity. Gerardo Ceballos (National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM) and Rodolfo Dirzo (Stanford University) are hailed by the committee as “trailblazing researchers in ecological science and conservation,” whose joint work in Latin America and Africa “has established that current species extinction rates in many groups of organisms are much higher than throughout the preceding two million years.” In effect, by documenting losses of animals and plants in some of the Earth’s most biodiverse habitats, both have contributed to showing that today’s biodiversity crisis is, as the citation states, “an especially rapid period of species loss occurring globally and across all groups of organisms, and the first to be tied directly to the impacts of a single species, namely, us.”

The two awardee ecologists have catalyzed the global study of “defaunation,” a term Dirzo coined to describe the alterations causing the disappearance of animals in the structure and function of ecosystems. His research, says the citation, has revealed how the elimination of a single species can trigger pernicious “cascading effects” by disrupting the web of interactions it maintains with other organisms. This, in turn, has adverse effects on human wellbeing through the reduction of the goods and services they perform. His work has helped provide the “necessary scientific basis” to further the adoption of evidence-led conservation measures.

“The experimental work done by professors Ceballos and Dirzo has led the way in quantifying the extent of species loss,” explains a Research Professor in the Department of Integrative Ecology at Doñana Biological Station (CSIC) and secretary of the award committee. “And what is truly shocking about their results is that this species extinction rate, or ‘defaunation process’, as it is known, is advancing today at a speed several orders of magnitude above the rate recorded over the last two million years. This shows that we are up against a truly intimidating challenge; one that these two researchers have documented and assessed across thousands of vertebrate, invertebrate and plant species.”

Another committee member, a Research Professor in the Department of Biogeography and Global Change at the National Museum of Natural Sciences (CSIC) in Madrid, uses an analogy to highlight the importance of the awardees' work: “Imagine we are flying in a plane sitting next to the window. And looking out, we see bits of the plane falling off. It may not nosedive straight away, but the first thought that crosses the passenger’s mind is: how long can this plane keep flying without its component parts? Something similar occurs with ecosystems. As they lose their “parts'' or species, they also lose vital functions, and it is these functions that provide essential services. The work of Dirzo and Ceballos is a valuable addition to the understanding of how such losses affect the resilience and sustainability of our ecosystems, shedding light on the urgent need for conservation actions to preserve the integrity of these systems that are critical to our survival.”

An accelerating extinction rate driven by our own species

Ceballos and Dirzo's endeavors have advanced in tandem through most of their professional careers, with results in many cases complementing one another’s. But the origin of their collaboration lies back in the early 1980s, when both were studying at the University of Wales (United Kingdom), Dirzo pursuing his doctorate courses and Ceballos completing his master’s degree. They first connected over their shared concern at the increasingly evident impact on nature of human activity. “We started having conversations not just on scientific matters, but about how worried we were about the anthropogenic impact on the natural world we were seeing all around us,” Dirzo recalls.

Further ahead, Ceballos turned his research attention to the study of wildlife and the magnitude of the advancing extinction, while Dirzo centered his efforts on ecological interactions between plants and animals, and the consequences of this extinction.

Ceballos’ work on assessing current rates of extinction led him to explore comparisons with the rates of the past. “Evolution operates as a process of species extinction and generation,” he relates. In normal periods, more species appear than disappear, such that diversity gradually expands. There have been five mass extinction events in the last 600 million years, the last of which brought the demise of the dinosaurs. All had in common that they were catastrophic – wiping out 70% or more of the world’s species – had their origins in natural disasters, like a meteorite collision, and were extremely rapid in geological terms, lasting hundreds of thousands or millions of years.”

After a detailed analysis of numerous species, a research team led by Ceballos concluded – in a paper published in Science Advances in 2015 – that vertebrate extinction rates are from 100 to 1,000 times greater than those prevailing over the last few million years. “What this means is that the vertebrate species that have died out in the past 100 years should have taken 10,000 years to become extinct. That is the magnitude of the extinction,” he explains. His work pointed one way only; to the fact that the sixth mass extinction was already upon us, a scenario that for Ceballos has three major implications: “The first is that we are losing all that biological history. The second is that we are losing living creatures that have accompanied us through time and have been key in driving forward human evolution. And the third is that all these species are assembled in ecosystems that provide us with the environmental services that support life on Earth, like the right combination of gases in the atmosphere, drinking water, fertilization… Without these environmental services civilization as we know it cannot be sustained.”

The grave impact of extinction on ecosystem services

Species extinction is the last stage in the process, but Ceballos insists that population extinction is no less worrying, since it is these populations that provide environmental services on a local or regional scale. He gives an example: “It doesn’t matter if there are jaguars in Brazil if they have died out in Mexico, because the environmental services they performed in Mexico will have disappeared with them.”

Ceballos and his colleagues explored this concept in a study of prairie dog populations, which in the 1990s were thought to be pests and were the target of eradication campaigns. Through this study, published in 1999 in the Journal of Arid Environments, they were able to prove that, rather than pests, they actually play a vital role in maintaining their ecosystem, the grasslands of the southwest of the United States and north of Mexico.

“We found that prairie dogs were essential to the upkeep of ecosystem services, because if they are lost it sets off a chain of extinctions across the many other species who depend on them.” With these rodents gone, the soil becomes less fertile, erosion increases and the scrubland advances, wiping out the plants that serve as forage for livestock. “The impact on environmental services is colossal,” he affirms.

For the Mexican ecologist, the biodiversity crisis we are experiencing is of a magnitude similar to the crisis of climate change and both problems are closely interrelated: “We have to couple the issue of species extinction with the issue of climate change, and understand that it is a threat to humanity’s future.”

From deforestation to “defaunation”: the “cascading effect” of species loss

Rodolfo Dirzo states, "I was soon asking myself: these fascinating things I study, the ecology and evolution of plants and animals and their interactions, may not be around to study in future if we don’t start to do something about what is happening to natural systems.” This concern, which he shares with Ceballos, has guided Dirzo’s steps throughout his career, from Mexico to the United States.

By analogy with deforestation, he came up with the term “defaunation” to refer to the imbalance entailed by the absence of animals. “Everyone has a mental picture when they hear the word deforestation. They understand that what they are seeing is a problem, the erosion of ecosystems due to loss of vegetation. And it occurred to me that the word “defaunation” could be a way to highlight that, just as Earth’s ecosystems face a serious problem of deforestation, another serious threat lies in the depletion and possible extinction of animal species.”

The scientist began studying the effects of this phenomenon and published his findings in a chapter of the book Plant-Animal Interactions: Evolutionary Ecology in Tropical and Temperate Regions in 1991.

“Species do not live in an ecological vacuum,” he points out, insisting that it is not just species disappearances we have to worry about, but the extinction of species populations and, above all, species interactions, which should accordingly be a core focus of conservation actions.

Elephant poaching and the risk of pandemics

These effects, Dirzo explains, give rise to a phenomenon that he refers to as “winners and losers.” When these large animals die out locally, they are evidently losers, while smaller animals like rodents take advantage of their absence and therefore become winners. But these smaller animals also carry pathogens like Leptospira, Leishmania and even the bacteria that causes bubonic plague. So if populations of these pathogen-carrying animals increase, there is a greater chance that they will transmit diseases to humans. “We could be put at risk of suffering a new pandemic,” he affirms, “given the proliferation of these diseases and the current mobility of human beings.”

The researcher has verified these effects through experiments carried out in Africa. He and his team installed electrified fences in some very well-conserved parts of the savannah to stop large animals from entering. They then left other areas unfenced, so they could compare two identical ecosystems, one with large wildlife and one without. “We found that when an area is closed off to these animals, the savannah vegetation changes dramatically.” Further, the rodent population triples, as does the risk of diseases that can be transmitted to humans. In this way, he says, we get “a cascade that runs from elephant poaching to the real risk of a new human pandemic.”

In fact, it is not even necessary for a whole local population to die out for it to pose an ecological problem. If there are not enough individuals to maintain viable populations, the species in question can no longer interact with other organisms and fulfill its ecosystem function. It becomes what is known, says Dirzo, as a “living dead species.”

Hunting is just one human activity that can drive species populations totally or partially extinct and trigger such grave effects as a pandemic. Dirzo lists five key factors that drive defaunation: land use change for pasture or urban development; the overexploitation of resources; pollution – by anything from noxious chemical products to marine plastic waste; the introduction of non-native or invasive species in ecosystems where they don’t belong; and climate change. “But none of these five factors,” he adds, “operates in isolation: they are all interlinked, and this makes the challenge of dealing with biological extinction all the more complex.”

Laureate bio notes

Gerardo Ceballos (Toluca, Mexico, 1958) graduated in biology from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (Mexico) and went on to earn master’s degrees from the University of Wales (United Kingdom) and the University of Arizona (United States), where he received his PhD in 1988. The following year, he took up a position at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where he is currently a Senior Researcher at the Institute of Ecology. He is the author of 55 books and numerous scientific papers, and some 200 applied studies in conservation and management that have featured in technical reports supported by institutions like the World Bank, the U.S. Agency for International Development or the State of Mexico Government. He is one of the forces behind Mexico’s endangered species legislation and the designation of over 20 natural protected areas covering more than 1.5 million hectares.

Rodolfo Dirzo (Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1951) completed a BSc in Biology at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (Mexico) then went on to obtain an MSc and PhD from the University of Wales (United Kingdom). Between 1980 and 2004 he held various teaching and research positions at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), serving as a professor, Director of the Los Tuxtlas Biological Station and Chair of the Department of Evolutionary Ecology. In 2004 he joined the faculty at Stanford University, where he is currently Bing Professor in Environmental Science, Professor of Earth System Science, Senior Fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment and Associate Dean for Integrative Initiatives in Environmental Justice. Dirzo has also taught in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Puerto Rico.

Nominators

A total of 47 nominations were received in this edition. The awardee researchers were nominated by Gretchen Cara Daily, Bing Professor of Environmental Science at Stanford University (United States) and 2018 Frontiers of Knowledge Laureate in Ecology and Conservation Biology.

#🇲🇽#STEM#Gerardo Ceballos#Rodolfo Dirzo#extinction#animal#plants#Science Advances#ecosystems#BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards in Ecology and Conservation Biology#prairie dog#Journal of Arid Environments#livestock#climate chaange#biodiversity#defaunation#National Autonomous University of Mexico#UNAM#deforestation#elephant#pandemic#africa#living dead species#rodent#elephant poaching#hunting#Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa#Institute of Ecology#world bank#U.S. Agency for International Development

1 note

·

View note

Text

Premio Fronteras del Conocimiento a dos ecólogos mexicanos por cuantificar la magnitud de la Sexta Gran Extinción de especies

► Las investigaciones de Gerardo Ceballos y Rodolfo Dirzo establecieron que “las tasas actuales de extinción de especies en muchos grupos de organismos son mucho más altas que en los dos millones de años previos”, según resalta el acta del jurado.

De izquierda a derecha: Gerardo Ceballos y Rodolfo Dirzo. / FBBVA

El Premio Fundación BBVA Fronteras del Conocimiento en Ecología y Biología de la…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

“ A fine 2017, 15.364 scienziati di 184 paesi firmarono una dichiarazione dal titolo World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice, in cui si affermava: «abbiamo scatenato un evento di estinzione di massa, il sesto in circa 540 milioni di anni, in cui molte forme di vita attuali potrebbero essere annientate o sulla via per l’estinzione entro la fine di questo secolo». Si potrebbe essere tentati di infischiarsene. Molti, in cuor loro, magari pensano: abbiamo distrutto intere civiltà umane, perché preoccuparsi della scomparsa di un numero, seppur elevato, di specie animali e vegetali? Sopravvivremo tranquillamente.

Credo che sia questo il pericolo maggiore: pensare che quanto stiamo facendo non riguardi direttamente la conservazione della nostra civiltà, non si parli nemmeno della sopravvivenza della nostra specie. Come potrebbe l’estinzione di piante, insetti, alghe, uccelli, mammiferi vari, influire sulla nostra sopravvivenza? Ok, è triste che i rinoceronti, i gorilla, le balene, gli elefanti, le banane, le foche monache, le lucciole, le violette si estinguano ma, alla fine, chi li ha mai visti? Viviamo in città. Per noi urbani, la natura è roba da documentari, niente a che vedere con noi. A noi interessa lo spread, il pil, l’euribor, il nasdaq, sono queste le cose che possono far crollare la civiltà come la conosciamo. Sbagliato! Lo ripeto, è l’idea – talmente diffusa da essere diventata un luogo comune – che noi umani siamo fuori dalla natura che è veramente pericolosa. L’estinzione di un numero così elevato di specie, in un tempo così breve, è qualcosa le cui conseguenze non possiamo valutare. Scrive Rodolfo Dirzo, professore a Stanford ed esperto di interazione fra le specie: «I nostri dati indicano che la Terra sta vivendo un episodio enorme di declino ed estinzione, che avrà conseguenze negative a cascata sul funzionamento degli ecosistemi e sui servizi vitali necessari a sostenere la civilizzazione. Questo “annientamento biologico” sottolinea la serietà per l’umanità del sesto evento di estinzione di massa della Terra». Ora, è vero che le cassandre non sono mai state simpatiche a nessuno, tuttavia si tende a dimenticare che Cassandra – l’originale –, la profetessa inascoltata, aveva ragione! Essere consapevoli del disastro che i nostri consumi stanno creando dovrebbe renderci tutti più attenti ai nostri comportamenti individuali, ma anche arrabbiati verso un modello di sviluppo che, per premiare pochissimi, distrugge la nostra casa comune. “

Stefano Mancuso, La nazione delle piante, Laterza (collana i Robinson / Letture), 2019¹; pp. 79-80.

#Stefano Mancuso#La nazione delle piante#natura#scienze#ecologia#sesta estinzione#estinzioni di massa#pianeta Terra#geologia#libri#eventi calamitosi#antropocene#civiltà#previsioni#futuro#umanità#divulgazione scientifica#saggistica#saggi#città#Rodolfo Dirzo#scienze naturali#Cassandra#limiti dello sviluppo#sviluppismo

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wild radishes pass on defense tricks to protect their young

Wild radishes and other plants can also go to impressive lengths to protect their young.

In a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers show that wild radish plants turn on different anti-predator genes during key phases of their lives in response to predation from caterpillars.

Moreover, the plants can also pass these “on-demand” defensive strategies on to their offspring to prepare them for the predation they are likely to experience as seedlings and adults.

Scientists have known that parent plants can pass helpful defenses to their offspring, but how plants allocate these defenses over time and across generations is poorly understood.

Understanding how plants protect themselves matters to humans for lots of reasons, says senior author Rodolfo Dirzo, professor of environmental science at Stanford University.

For example, aspirin, morphine, and the heart medication digitalis are a few of the many drugs derived from chemical defenses plants created. Plants’ natural defenses can also be exploited by humans to protect crops and for pest management.

“The history of humanity has been heavily influenced by the evolution of plant-insect interactions,” says Dirzo, who is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Plant defenses

Plants arm themselves with toxins, spines, and other chemical and physical defenses to keep plant-eating animals, known as herbivores, at bay. But defenses can be costly for plants to produce, so they often spend their resources on anti-herbivore defenses only when it benefits them most.

In plants, the genes responsible for generating anti-predator defenses are often “turned on” via a chemical “switch” called DNA methylation. DNA methylation is an example of an epigenetic (“epi” meaning “on top of”) mechanism that modifies gene behavior without altering the underlying DNA sequence of the genes themselves.

When Mar Sobral joined Dirzo’s lab as a postdoctoral scholar in 2011 she began investigating how predation can affect heritable epigenetic changes.

In a study published in March 2021 in Frontiers in Plant Science, the team showed that wild radishes were much more likely to produce flowers with pink or purple flowers if their parents were attacked by caterpillars.

“Apparently, the epigenetic changes linked to increased physical and chemical defenses can also induce changes in pigment production because they have related pathways,” says Sobral, who is now a researcher at the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela in Spain and is first author of both studies.

Voracious caterpillars

In order to delve deeper into how plants evolve and pass defenses to their offspring in response to predation, Sobral, Dirzo, and Isabelle Neylan, a former undergraduate in Dirzo’s lab, designed a multigenerational greenhouse experiment to explore interactions between wild radish plants and their top predator, the cabbage butterfly caterpillar.

In wild radishes, anti-predator defenses manifest as bristly leaf hairs and toxic mustard oil. The team wanted to know how wild radish plants allocate their physical and chemical defenses as seedlings and adults, and how heightened defenses during a particular life stage may be transmitted across generations.

The greenhouse experiment enabled the researchers to explore their questions in a controlled environment—they allowed only cabbage butterfly caterpillars to graze on the wild radish plants, and gave the plants ample light, water, nutrients, and a constant temperature.

The researchers hypothesized that wild radish plants would turn on defenses in response to caterpillar attacks. They also predicted the offspring of plants that caterpillars attacked would have more defenses and would be more likely to produce defenses when attacked by caterpillars.

Lastly, since seedlings are fragile and more likely to be lethally damaged in this life stage, the team predicted that the ability to induce defenses would be strongest in seedlings.

Wild radish call to arms

The researchers tested their predictions using 160 wild radish plants and scores of voracious caterpillars. They allowed the caterpillars to attack plants for two weeks during two key life stages—when seedlings had produced their first two leaves, and when adult plants bloomed. For comparison, a sample of control plants was kept free of caterpillar attack.

The researchers estimated the effectiveness of each plants’ physical defenses by counting the density of hairs on leaf samples. Their chemical defenses, in the form of mustard oil exuded from the leaves, were also collected and analyzed. Finally, the leaf tissue of both attacked and non-attacked plants were analyzed for signs of DNA methylation.

The study confirmed that DNA methylation is a chemical call to arms in wild radish plants and that attacks by hungry caterpillars trigger DNA methylation in parent plants and in their offspring.

The experiments on the offspring of attacked wild radish plants revealed wild radishes’ physical and chemical defenses were easily turned on by predation at the seedling stage. However, only chemical defenses—not physical defenses—were deployed by the adult plants in response to attack.

“There were several surprises,” says Sobral. “We didn’t expect that adult plants can be induced to produce defenses and can display the defenses they inherited from their ancestors. We assumed these processes were mainly happening at the seedling stage.”

Discovering that wild radish plants can turn on anti-predator defenses as seedlings and adults, but that adults can only use chemical defenses, was also a surprise; it was generally thought that only seedlings can turn on anti-predator defenses.

This study helps inform our understanding of the many, complex plant-insect interactions on Earth, the researchers say.

“About 50% of the species scientists have discovered and named on the planet are composed of ‘higher’ plants (such as ferns, conifers, and flowering plants) and the insects that feed on them,” Dirzo says.

And those are just the species we know about, he pointed out. “Thus, their interactions represent a central feature of Earth’s biodiversity,” he adds. “We cannot understand the diversity of life on Earth without understanding the interactions between plants and the organisms that feed on them.”

Additional coauthors are from the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas in Spain and Black Hills State University in South Dakota. Stanford funded the work.

Source: Stanford University

The post Wild radishes pass on defense tricks to protect their young appeared first on Futurity.

Wild radishes pass on defense tricks to protect their young published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Photo

Vogelsterben Deutschland 7/2018!

Die Zahl der Insekten hat in manchen Gebieten Deutschlands schon um bis zu 80% abgenommen und das hat natürlich auch Auswirkungen auf die Vogelwelt.

(By now in certain regions of Germany the the number of insects has been reduced per 80% and this affects, of course, the bird populations as well.)

In den letzten drei Jahrzehnten ging die Zahl der Vögel in der Agrarlandschaft in 28 Staaten Europas um mehr als die Hälfte zurück. (Der stille Frühling)

(Over the last three decades the number of birds in agricultural landscape has been reduced more than half in 28 European states.)

Fünf Mal gab es in den vergangenen 540 Millionen Jahren gewaltige Artensterben, zeigen Fossilienfunde. Forscher sehen eine aktuelle, menschengemachte, sechste Welle in vollem Gange. Allein seit dem Jahr 1500 seien mehr als 320 terrestrische Wirbeltiere ausgestorben, die Bestände der verbliebenen seien im Schnitt um ein Viertel geschrumpft, schreiben Wissenschaftler um Rodolfo Dirzo von der Stanford University in der Zeitschrift "Science". Nach einem Bericht der Vereinten Nationen zur Artenvielfalt sterben bis zu 130 Tier- und Pflanzenarten täglich aus.

Der Mensch im Anthropozän hat auf die Artenvielfalt also langfristig eine "ähnlich verheerende" Wirkung wie der große Meteor-Einschlag vor 65 Millionen Jahren. (X)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Tenemos Tiempo:

Urge Cambiar Radicalmente

a Nuestra Civilización

Por Esmeralda Loyden

El mundo se nos muere. O lo que somos nosotros como civilización. En una entrevista realizada al doctor mexicano Rodolfo Dirzo, actualmente profesor de la Universidad de Stanford en el departamento de Biología, me habló de que nos quedan entre 30 o 40 años para prevenir que “se venga un cambio de condición o de situación del estado ecológico de la Tierra.”

El antropoceno, el punto de no retorno

“Si la concentración de gases de efecto invernadero continúa, decía el científico, si la tasa de deforestación se mantiene, si la tasa de extracción de recursos no disminuye, si la invasión de especies exóticas pervive, si los niveles de contaminación siguen adelante, habrá un punto de no retorno.

“Estamos realmente muy cerca de ese punto en el que un pequeño empujón podría producir una situación que nosotros le llamamos ‘un nuevo estado ecológico’. Como ocurrió cuando cayó el meteoro del Chibchulub, o cuando las plantas empezaron a producir oxígeno, lo que hizo que el planeta entrara en un estado totalmente diferente.

“Las grandes eras geológicas tienen un nombre que denota que la Tierra entró en un cambio, en una situación de equilibrio, en una situación a veces llamada de ‘equilibrio diferente’; en una situación de estado estructural distinto. Hoy en día estamos hablando de que hay una nueva era geológica llamada el Antropoceno, en la que nosotros somos una fuerza biológica que puede cambiar al planeta a un estado nuevo, distinto totalmente.

“Y el asunto que estamos tratando en un consenso científico es que el tiempo que falta para que pudiera la pelota caerse al barranco no es mayor a cincuenta años. Es el momento de hacer algo; de no hacerlo, podríamos llegar a vivir una situación irreversible. A eso me refiero con un nuevo estado, que no sea reversible la situación en la que estamos. Creo que tenemos una ventana de tiempo, pero no es muy larga.”

En 2015, cerca de mil científicos de todo el planeta circularon un documento que fue firmado por muchísimos otros investigadores. “A las primeras semanas ya teníamos 300 firmas y ahora ya perdí la cuenta, porque no le doy seguimiento día tras día, pero alguien nos ha dicho que un número mágico sería llegar a un millón de firmas.

“Con eso podríamos acceder a muchos de los presidentes del mundo. Llevarles ese consenso y decirles cuál es la responsabilidad que tenemos. Está hecho para que todo mundo lo pueda leer.

“Cuando salió a la luz el consenso, lo presentamos ante el gobernador Jerry Brown, de California, y él realmente lo abrazó como un proyecto que quiere difundir ampliamente; ya lo ha llevado a China y a otros países.”

Algo habrá pasado desde entonces, avances tecnológicos de aprovechamiento de energía, reconversión, etcétera, pero continuamos viendo el derretimiento de los polos, la pérdida de biodiversidad, y sobre todo de los procesos que se vinculan con la biodiversidad ya que, al ser destruidos, todo se encaminará a un deterioro masivo de las especies de la tierra y del equilibrio de la vida que conocemos.

Por su enorme importancia, reproducimos aquí el resumen del documento que circuló en 2015.

Puntos clave para tomadores de decisiones

Consenso científico sobre el mantenimiento de los sistemas ecológicos esenciales para la supervivencia de la humanidad en el siglo XXI

(Ver http: consensusforaction.standford.edu/see-scientific-consensus/execsummary_spanish_03.pdf)

La Tierra se está acercando rápidamente a un punto de quiebre. El impacto humano está causando daños alarmantes a nuestro planeta. Como científicos dedicados a estudiar la interacción entre la humanidad y la biosfera desde una amplia gama de enfoques, hemos llegado a un consenso: la evidencia de que la humanidad está dañando los sistemas ecológicos de supervivencia humana es apabullante.

Más aún, con base en la mejor información científica disponible, llegamos también al consenso de que la calidad de vida humana se deteriorará de manera sustancial hacia el año 2050 si continuamos actuando de la misma forma.

Ilustración por Cheng (Lily) Li

La evidencia científica ha identificado inequívocamente los impactos más críticos de la actividad humana:

Trastornos del clima — Anomalías climáticas cada vez más frecuentes y de magnitud creciente desde que los humanos surgieron como especie.

Extinciones biológicas — Desde la extinción de los dinosaurios no se había visto una tasa de pérdida de especies y poblaciones, en la tierra y en los mares, como ahora.

Pérdidas a gran escala de los ecosistemas — Hemos arado, pavimentado, o totalmente transformando más del 40% de la superficie terrestre sin hielo, y no existe lugar terrestre o marino que no tenga, directa o indirectamente, algún grado de influencia humana.

Contaminación — Los contaminantes en el aire, agua y tierra han alcanzado niveles nunca antes vistos, y siguen en aumento constante, causando daños a humanos y organismos silvestres de manera imprevista.

El crecimiento de la población humana y los patrones de consumo de recursos — Es probable que la población actual de 7,000 millones llegue a 9,500 millones hacia el año 2050, y que las presiones generadas por el consumo excesivo que ejercen las clases media y alta se incrementen.

Así, para cuando los niños de hoy sean adultos, los sistemas ecológicos del planeta, críticos para la prosperidad y existencia humana, podrían estar dañados irremediablemente por la magnitud, la distribución global, y el efecto combinado de los cinco factores señalados, a menos que se tomen acciones concretas e inmediatas para garantizar un futuro sostenible y de calidad.

Como miembros activos de la comunidad científica involucrados en evaluar los impactos biológicos y sociales del cambio global, hacemos esta llamada de alarma al mundo. Para asegurar la continuidad del bienestar humano, todos — individuos, empresas, líderes políticos y religiosos, científicos, y personas de todos los ámbitos— tenemos que empezar a trabajar arduamente, a partir de hoy, en la resolución de los cinco grandes problemas globales:

1. Perturbaciones del Clima

2. Extinciones Biológicas

3. Pérdida de Diversidad de Ecosistemas

4. Contaminación

5. Crecimiento Poblacional y Consumo Desigual

* Rodolfo Dirzo nació en Cuernavaca, Morelos. Se graduó en Biología en la Universidad Autónoma de Morelos, con la tesis “Mapa de vegetación de la cuenca del río Cutzamala, estados de Michoacán, Guerrero y México. Hizo su maestría y doctorado en Ecología (1980) en la Universidad de Gales, Gran Bretaña. Ha colaborado en el Instituto de Ecología de la UNAM, en donde además de dar clases de licenciatura y posgrado, fue investigador y jefe del departamento de Ecología Evolutiva. Ha sido profesor en universidades de Estados Unidos y de América Latina. Dirigió la Estación de Biología Tropical de la Reserva de los Tuxtlas y ha colaborado con la Estación Biológica de Chajul, en la Selva Lacandona de Chiapas. Sus trabajos se han enfocado a entender las relaciones ecológicas y evolutivas entre plantas y animales en los ecosistemas naturales. Fue elegido miembro del Comité Científico del Programa Internacional Biosfera-Geosfera y del Consejo Internacional de Científicos. La Organización de Estudios Tropicales de Costa Rica lo reconoció con el Oustanding Service Award, en 202. Recibió de la SEMARNAT el Premio Nacional al Mérito Ecológico, en 2003. Y el premio Universidad Nacional también en ese año.

* El fragmento de la entrevista que aquí se presenta fue obtenido de una entrevista más larga publicada en el libro Las voces de la biodiversidad en México, que circula actualmente en Internet.

0 notes

Quote

Extinction obviously matters. If a species is completely wiped out, that’s an important and irreversible loss. But that flip from present to absent, extant to extinct, is just the endpoint of a long period of loss. Before a species disappears entirely, it first disappears locally. And each of those local extinctions—or extirpations—also matters.

“If jaguars become extinct in Mexico, it doesn’t matter if there are still jaguars in Brazil for the role that jaguars play in Mexican ecosystems,” says Ceballos. “Or we might able to keep California condors alive forever, but if there are just 10 or 12 individuals, they won’t be able to survive without human intervention. We’re missing the point when we focus just on species extinction.”

He and his colleagues, Paul Ehrlich and Rodolfo Dirzo, have now tried to quantify those local losses. First, they analyzed data for some 27,600 species of land-based vertebrates, and found that a third of these are in decline. That doesn’t mean they are endangered: A third of these declining species are listed as “low concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, meaning that they aren’t in immediate peril. But that, according to Ceballos’s team, provides a false sense of security. Barn swallows, for example, still number in the millions, but those numbers are going down, and the birds are disappearing from many parts of their range. “Even these common species are declining,” says Ceballos. “Eventually, they’ll become endangered, and eventually they’ll be extinct.”

The team also analyzed detailed historical data for 177 species of mammals. In the last century, every one of these species has lost at least 30 percent of its historical range, and almost half have lost more than 80 percent. Consider the lion. If you divide the world’s land into a grid of 22,000 sectors, each containing 10,000 square kilometers, around 2,000 of those would have been home to lions at the start of the 20th century. Now, just 600 of them are. These royal beasts, which once roamed all over Africa and all the way from southern Europe to northern India, are now confined to pockets of sub-Saharan Africa, and a single Indian forest. Their numbers have fallen by 43 percent in the last two decades.

Several other species that were once thought to be safe are also now endangered. Since the 1980s, the giraffe population has fallen by up to 40 percent, from at least 152,000 animals to just 98,000 in 2015. In the last decade, savanna elephant numbers have fallen by 30 percent, and 80 percent of forest elephants were slaughtered in a national park that was one of their last strongholds. Cheetahs are down to their last 7,000 individuals, and orangutans to their last 5,000.

All told, “as much as 50 percent of the number of animal individuals that once shared Earth with us are already gone, as are billions of populations,” Ceballos and his colleagues write. “While the biosphere is undergoing mass species extinction, it is also being ravaged by a much more serious and rapid wave of population declines and extinctions.”

It's a Mistake to Focus Just on Animal Extinctions - The Atlantic

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terra, sesta estinzione di massa. “La popolazione animale già dimezzata”

Terra, sesta estinzione di massa. “La popolazione animale già dimezzata” (di Rosita Rijtano su Repubblica) Dimezzato. È il numero di animali che ci circonda in poco più di un secolo: dal 1900 al 2015. Succede ovunque sul Pianeta: a sud come a nord, a est come a ovest. Branchi di giraffe, elefanti, rinoceronti e oranghi che via via si assottigliano. Fino, a volte, persino sparire da alcune aree geografiche. Uno spopolamento dalle proporzioni inimmaginate che ha ricadute sull’intero ecosistema. Sono le prime, corpose, stime della “sesta estinzione globale”, così la definiscono tre biologi dell’università di Stanford in uno studio appena pubblicato sulla rivista scientifica Pnas. Un’analisi quantitativa diretta a documentare le dimensioni del problema, inquietanti. “In tutto il mondo si sta verificando un annichilimento biologico”, sostiene Rodolfo Dirzo, noto ecologo che negli anni trascorsi ha già lavorato su quella che lui ha etichettato “defaunazione antropocentrica” e uno degli autori della ricerca. Un fenomeno che va al di là dei singoli esemplari considerati scomparsi dal mondo, in media due ogni anno. È, per esempio, il caso del Ciprinodonte Catarina (Megupsilon aporus), specie di pesce d’acqua dolce. O dei pipistrelli dell’Isola di Natale, in Australia. Le ultime notizie raccontano che anche il pinguino imperatore, in Antartide, non se la stia passando molto bene. Sarà costretto a migrare per trovare altri luoghi in cui riprodursi e cacciare, altrimenti rischia di non superare la fine del secolo. Storie di per sé significative. Eppure non bastano a darci un quadro complessivo della situazione, dicono gli studiosi: “Focalizzarsi sulle estinzioni porta alla comune, falsa, impressione che il biota della Terra (cioè quella parte che ospita gli esseri viventi ndr), non sia immediatamente minacciato. Ma stia solo attraversando una fase di maggiore perdita della biodiversità”. Ed è per chiarire questo aspetto che ha preso forma il nuovo lavoro. I ricercatori hanno analizzato la distribuzione geografica di 27,600 specie di vertebrati: uccelli, anfibi, mammiferi e rettili. A cui hanno aggiunto i dati dettagliati di un campione di 177 esemplari di mammiferi, ben studiati, dal 1900 al 2015. Utilizzando la riduzione dei luoghi in cui si possono trovare questi animali come indicatore di un numero più esiguo, sono arrivati alla conclusione che “il calo demografico è estremamente alto, anche nelle specie considerate a basso rischio”. In particolare, i risultati mostrano che più del 30% dei vertebrati è in declino sia in termini di dimensioni sia di distribuzione geografica. Non solo, dei 177 mammiferi presi in considerazione, tutti hanno perso almeno il 30% delle loro aeree di residenza. Mentre oltre il 40% ne ha abbandonato più dell’80%. “Le specie maggiormente coinvolte sono tantissime”, spiega a Repubblica Gerardo Ceballos, coordinatore della ricerca. “Alcune delle più conosciute sono il ghepardo, elefante e leone africano, rinoceronte nero, orangotango sia del Borneo che del Sumatra”. A soffrirne di più sono le zone tropicali del globo, dove la fauna ha lasciato ampi spazi liberi. Con l’Africa a fare da capofila, seguita da Australia, Asia e Europa. Le conseguenze? “La distruzione del sistema di supporto vitale da cui la nostra civiltà è totalmente dipendente per il cibo, molti prodotti industriali, e un ambiente vivibile”. Uno scenario sconfortante. A margine, però, c’è una nota positiva, avverte lo scienziato: “Dato che a trainare questo processo sono le attività umane, possiamo fare molto per minimizzare il nostro impatto e quindi le proporzioni del fenomeno”. Ridurre l’inquinamento e lo sfruttamento delle risorse, limitare i traffici delle specie in pericolo di vita, aiutare le popolazioni povere a preservare la biodiversità: sono solo alcune delle azioni da intraprendere. “È necessario un impegno internazionale”, puntualizza Ceballos. Anche perché “il cambiamento climatico sta aggravando la situazione”. E per agire “rimane una piccola finestra di tempo, che si sta chiudendo rapidamente”. Il rischio è di rimanere i soli sulla Terra.

(di Rosita Rijtano su Repubblica) Dimezzato. È il numero di animali che ci circonda in poco più di un secolo: dal 1900 al 2015. Succede ovunque sul Pianeta: a sud come a nord, a est come a ovest. Branchi di giraffe, elefanti, rinoceronti e oranghi che via via si assottigliano. Fino, a volte, persino sparire da alcune aree geografiche. Uno spopolamento dalle proporzioni inimmaginate che ha…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Clockwise from top left: A rare male king cheetah, a lion, a pangolin and a orangutan, all members of species that have experienced sharp declines in recent decades.

by Gerardo Ceballos, a researcher at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City & co-authors, Paul R. Ehrlich and Rodolfo Dirzo, both professors at Stanford University

Era of ‘Biological Annihilation’ Is Underway, Scientists Warn JULY 11,2017 READ MORE https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/11/climate/mass-extinction-animal-species.html

0 notes

Text

The vaquita marina, example of "defaunación" and crisis of the biodiversity

The vaquita marina, example of “defaunación” and crisis of the biodiversity

The vaquita marina is an example of a planetary phenomenon, “another global change, known as defaunación”, which consists of “the loss of animal life in ecosystems,” biologist Rodolfo Dirzo, a professor at the University, told Efe. of Stanford.

The case of the vaquita marina, the smallest porpoise species in the world, of which there are 20 to 30 individuals in the Upper Gulf of California, is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Avanza pérdida de biodiversidad en el mundo

El riesgo que representa para la humanidad la pérdida de diversidad biológica resulta “tan significativo o más que el cambio climático”, aseveró el biólogo y especialista mexicano José Sarukhán, encargado de la Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Usanza de la Biodiversidad (Conabio).

De acuerdo con Sarukhán, el principal elemento de presión sobre lo que llamó “capital natural”, que se traduce en una apresurada pérdida de especies animales y floras, lo compone el desarrollo exponencial de la población humana, que se ha multiplicado desde el año 1950.

“Eso ha sido cruel, pero en numerosos estados que tienen un impacto formidable no solo por su dimensión sino por su patrimonio y fuerza política, lo que se ha acrecentado aún más es la tasa de consumo”, manifestó el catedrático en ecología por la Universidad de Gales (Reino Unido) en una entrevista con la Agencia EFE.

Según reseñó el portal Cromo, el especialista afirmó que, en comparación con una persona nacida en Estados Unidos en el año 1900, en este momento cada estadounidense “ingiere 16 veces más de todo: energía, agua, provisiones y fibras”.

“Si agregamos lo que se encuentra detrás de esto, que es el procedimiento económico asentado en que hay que maximizar la producción para que exista el máximo consumo, nos encontramos ante un contexto que no es el más hospitalario” para la vida, expresó el científico.

Las acotaciones del experto se encuentran en conformidad con los argumentos mostrados en un apartado publicado en el pasado mes de julio por la revista de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Estados Unidos (PNAS), que reporta una enérgica disminución en las poblaciones de vertebrados, indicativo de que está en camino la “sexta extinción masiva”.

Los escritores Gerardo Ceballos, Rodolfo Dirzo y Paul Ehrlich sustentan que los motores de tal catástrofe son la sobrepoblación y el sobreconsumo de los seres humanos.

Así, certifican que la pérdida intensiva de poblaciones se encuentra dañando servicios ecosistémicos decisivos para la civilización, como el abastecimiento de agua y alimentos o la ordenación del clima, y destacan que “la ventana para una acción práctica (para aquietar este fenómeno) resulta muy pequeña, posiblemente dos o tres décadas cuando mucho”.

0 notes

Text

"Aniquilación biológica mundial": El planeta entra en una sexta extinción en masa

Nuevo artículo publicado en https://www.prozesa.com/2017/07/13/aniquilacion-biologica-mundial-el-planeta-entra-en-una-sexta-extincion-en-masa/

"Aniquilación biológica mundial": El planeta entra en una sexta extinción en masa

El declive de muchas especies pueden causar un efecto cascada en las redes ecológicas mundiales, que dependen del equilibrio entre animales, plantas y microorganismos, advierten biólogos internacionales.

Durante los últimos 500 millones de años, en nuestro planeta tuvieron lugar cinco extinciones masivas, durante las cuales multitud de especies desparecieron en un corto espacio de tiempo. Ahora, un equipo internacional de biólogos advierte de que hemos entrado en "una sexta extinción en masa", que es "más grave de lo que se percibe", según un estudio publicado en la revista 'Proceedings of the National Academy of Science'. "Es un caso de una aniquilación biológica que ocurre a nivel mundial", alertó su coautor Rodolfo Dirzo, profesor de biología de la Universidad de Stanford (California, EE.UU.), de acuerdo a una nota publicada por el centro educativo. La investigación señala que hasta el 50% de animales que una vez poblaron la Tierra han desaparecido, lo que equivale a miles de millones de mamíferos, aves, reptiles y anfibios que han dejado de existir para siempre. La desaparición de la fauna "equivale a una erosión masiva de la mayor diversidad biológica en la historia de la Tierra", describe el estudio. Esta ha afectado sobre todo a mamíferos del sur y del sudeste de Asia, donde todas las especies de mamíferos grandes analizadas perdieron más del 80% de su rango geográfico. "La pérdida masiva de poblaciones y especies refleja nuestra falta de empatía con todas las especies silvestres que han sido compañeras nuestras desde nuestros orígenes", recalcó el autor principal del estudio, Gerardo Ceballos, de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. "Es un preludio de la desaparición de muchas más especies y del declive de los sistemas naturales que hacen posible la civilización", advirtió.

¿Cuál es la causa de la actual extinción?

Según explican los científicos, las anteriores extinciones masivas se debieron a cambios climáticos naturales, erupciones volcánicas o catastróficas caídas de meteoritos. Sin embargo, esta sexta extinción se debe a actividades humanas como la deforestación, la superpoblación, la contaminación, la caza furtiva y los fenómenos meteorológicos extremos vinculados al calentamiento global causado por el hombre.

Efecto cascada

Las pérdidas de especies nos privan de redes ecológicas que incluyen animales, plantas y microorganismos, lo que conduce a ecosistemas "menos resistentes", lo que podría poner en peligro la supervivencia de más especies. "La aniquilación biológica resultante obviamente tendrá graves consecuencias ecológicas, económicas y sociales" por las que la humanidad "pagará un precio muy alto", enfatiza el estudio. "Todos los indicios apuntan a ataques cada vez más poderosos sobre la biodiversidad en las próximas dos décadas, pintando un panorama sombrío del futuro de la vida, incluida la vida humana", concluyen los biológos.

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on Ziarul tau online

Tot mai multe specii pe cale de dispariţie. Omul îşi pregăteşte sfârşitul

Un studiu recent a arătat că lumea se confruntă cu o “anihilare biologică�� a animalelor, din cauza acţiunilor umanităţii şi modului în care acestea afectează Pământul.

Cercetătorii au cartografiat 27.600 de specii de păsări, amfibieni, mamifere şi reptile, aproape jumătate din speciile de vertebrate cunoscute, şi au concluzionat că planeta se confruntă cu a şasea extincţie în masă, iar aceasta arată mai rău decât se credea anterior.

Aceştia au descoperit că numărul animalelor care trăiau cândva în apropierea omului a ajuns să scadă cu până la 50%, conform revistei ştiinţifice Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Autorii studiului, Rodolfo Dirzo şi Paul Ehrlich, de la Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, şi Gerard Ceballs, de la National Autonomous University of Mexico, au spus că această cifră reprezintă “o eroziune masivă a celei mai impresionante diversităţi biologice din istoria Pământului.”

Autorii consideră că lumea cauzeze pagube imense biodiversităţii şi că timpul rămas pentru a acţiona spre binele acesteia este foarte scurt, “probabil două sau trei decenii cel mult”.

Rodolfo Dirzo a spus că rezultatele studiului au arătat “o anihilare biologică la nivel global, chiar dacă unele specii mai există pe undeva pe Pământ.”.

De asemenea, studiul a descoperit că mai mult de 30% dintre speciile de vertebrate existente au decăzut în mărime sau în teritoriul pe care îl ocupă.

Studiind 177 de specii de mamifere, autorii au descoperit că toate au pierdut cel puţin 30% din aria geografică pe care o foloseau între 1990 şi 2015, iar mai mult de 40% dintre aceste specii şi-au pierdut mai mult de 80% din varietate.

În jur de 41% dintre amfibieni sunt ameninţaţi cu dispariţia şi 26% dintre toate mamiferele, conform International Union for Conservation of Nature, care ţine o listă cu speciile pe cale de dispariţie.

“Acesta este un preludiu al dispariţiei tot mai multor specii şi al declinului sistemului nostru natural care face viaţa posibilă”, a menţionat Ceballos.

Sursă: The Independent

Sursa articol jurnalul.ro

, sursa articol http://blogville.ro/tot-mai-multe-specii-pe-cale-de-disparitie-omul-isi-pregateste-sfarsitul/

0 notes

Text

Se acelera extinción masiva de animales

La extinción o decadencia masiva de animales como rinocerontes, gorilas y leones se está acelerando y apenas quedan veinte o treinta años para detener esta “aniquilación biológica” que pone en peligro “los pilares de la civilización humana”, advirtió una reciente investigación.

Según reseñó el portal Cromo, más del 30% de las categorizaciones de especies de vertebrados se encuentran en declive, tanto en conocimientos de población como de partición geográfica, indicó el estudio, divulgado en la revista Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Se trata de una matanza biológica que se origina a nivel global, inclusive aunque las especies a las que corresponden estas poblaciones existan aún en algún lugar de la Tierra”, afirmó uno de los escritores del estudio, Rodolfo Dirzo, catedrático de Biología perteneciente a la Universidad de Stanford.

“La sexta extinción masiva ya se encuentra aquí y el margen para proceder con eficacia cada vez resulta más angosto, sin duda dos o tres decenios como máximo”. Se trata de un “ataque espantoso contra las bases de la civilización humana”.

El planeta Tierra ha experimentado hasta la actualidad cinco extinciones masivas, la última de ellas la de los dinosaurios, que tuvo término hace 66 millones de años. Según la generalidad de los científicos, existe una sexta en marcha.

Para los encargados de esta nueva investigación, la extinción ya “llegó más lejos” de lo que se profesaba hasta ahora con base en ilustraciones anteriores que hacían referencia únicamente a la extinción de las especies, y no a la capacidad y el reparto de las poblaciones.

Los investigadores pertenecientes a la Universidad de Stanford y la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México se comprometieron a estudiar a las poblaciones de animales salvajes. Desplegaron un mapa sobre el reparto geográfico de más de 27 mil especies de pájaros, anfibios, mamíferos y reptiles, un prototipo que personificaba cerca de la mitad de los vertebrados terrestres conocidos.

Igualmente, examinaron el descenso de la población en un modelo de 177 especies de mamíferos, para los que orientaron sus estudios a través de datos detallados del periodo 1900-2015.

Apenas 20 mil leones

De esos cerca de 200 mamíferos, todos perdieron al menos un 30 por ciento de las fajas geográficas en las que se encontraban repartidos, y más del 40 por ciento de ellos desaprovecharon más de 80 por ciento de sus áreas.

Los mamíferos del sur y el sudeste asiático se evidenciaron principalmente afectados: todas las especies de grandes mamíferos estudiados perdieron en esa franja más de 80% de su área territorial, indicaron los investigadores.

0 notes

Text

Conozca la extinción global que se avecina

Aproximadamente unas dos especies de vertebrados se extinguen cada año en promedio. Aunque la tasa parece relativamente lenta, expertos creen que es indicativa de una “aniquilación biológica” a nivel planetario.

“Éste es el caso de una matanza biológica que se lleva a cabo en el mundo, aunque las especies a las que pertenecen estas poblaciones todavía están presentes en algún lugar de la Tierra”, apuntó el coautor Rodolfo Dirzo, profesor de Biología en la Universidad de Stanford, Palo Alto, California, Estados Unidos.

Un estudio realizado en el año 2015 y coescrito por Paul Ehrlich, profesor emérito de Biología, y colegas mostraron que la Tierra ha entrado en una era de extinción en masa sin precedentes desde que los dinosaurios murieron hace 66 millones de años. El espectro de extinción se sitúa en alrededor del 41 por ciento de todas las especies de anfibios y el 26 por ciento de todos los mamíferos, según la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza (UICN), que tiene una lista de especies amenazadas y extintas. Esta escena de desastre global es el fruto de la pérdida de hábitat, la sobreexplotación, los organismos invasivos, la contaminación, la toxificación y el cambio climático.

El más reciente análisis que fue publicado en ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’, mira más allá de las extinciones de especies para proporcionar una imagen clara de la disminución de las poblaciones y los rangos. Los científicos mapearon los rangos de 27.600 especies de aves, anfibios, mamíferos y reptiles –una muestra que representa casi la mitad de las especies de vertebrados terrestres conocidos— y analizaron las pérdidas de población en una muestra de 177 especies de mamíferos bien estudiadas entre 1990 y 2015.

Por ejemplo las regiones tropicales han tenido el mayor número de especies decrecientes, mientras que las regiones templadas han visto proporciones similares o mayores de especies que decrecen. Los mamíferos del sur y sudeste de Asia, en la que las especies grandes de mamíferos analizados han perdido más del 80 por ciento de sus rangos geográficos, se han visto especialmente afectados.

0 notes