#1770s France

Text

Flower Hair Pin of Rubies, Diamonds, Sapphires, Topazes, and Emeralds, ca. 1770, French.

The British Museum.

#hair pin#accessory#1770s accessory#1770s#1770#french#1770s France#the British museum#diamonds#emeralds#sapphires#topazes#rubies

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dog kennel created for Marie Antoinette by Claude I Sené, ca. 1775-1780

#18th century#europe#pets#kennels#furniture#Claude I Sené#marie antoinette#france#1770s#silk#gilded wood#velvet#versailles#I forget how I tag things

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawing boy automata(1774)

#1770s#1770's#1700s#18th century#robots#automata#creepy#french#france#french enlightenment#francophile

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Valjean’s parents, Jean and Jeanne, named their two kids Jean and Jeanne

0 notes

Note

How did cotton win over linen anyway?

In short, colonialism, slavery and the industrial revolution. In length:

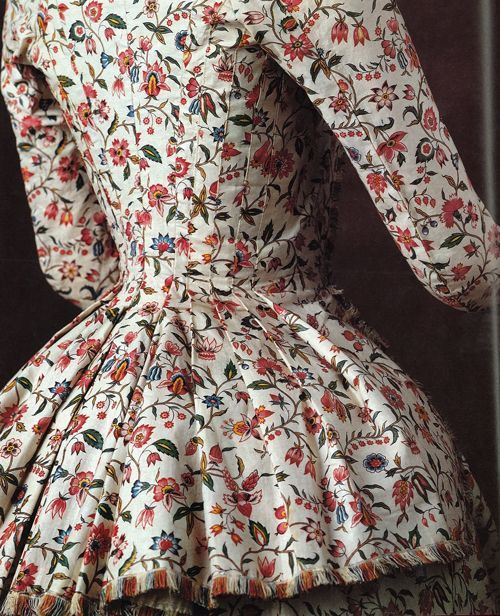

Cotton doesn't grow in Europe so before the Modern Era, cotton was rare and used in small quantities for specific purposes (lining doublets for example). The thing with cotton is, that's it can be printed with dye very easily. The colors are bright and they don't fade easily. With wool and silk fabrics, which were the more traditional fabrics for outer wear in Europe (silk for upper classes of course), patterns usually needed to be embroidered or woven to the cloth to last, which was very expensive. Wool is extremely hard to print to anything detailed that would stay even with modern technology. Silk can be printed easily today with screen printing, but before late 18th century the technique wasn't known in western world (it was invented in China a millenium ago) and the available methods didn't yeld good results.

So when in the late 17th century European trading companies were establishing trading posts in India, a huge producer of cotton fabrics, suddenly cotton was much more available in Europe. Indian calico cotton, which was sturdy and cheap and was painted or printed with colorful and intricate floral patters, chintz, especially caught on and became very fashionable. The popular Orientalism of the time also contributed to it becoming fasionable, chintz was seen as "exotic" and therefore appealing.

Here's a typical calico jacket from late 18th century. The ones in European markets often had white background, but red background was also fairly common.

The problem with this was that this was not great for the business of the European fabric producers, especially silk producers in France and wool producers in England, who before were dominating the European textile market and didn't like that they now had competition. So European countries imposed trade restrictions for Indian cotton, England banning cotton almost fully in 1721. Since the introduction of Indian cottons, there had been attempts to recreate it in Europe with little success. They didn't have nearly advanced enough fabric printing and cotton weaving techniques to match the level of Indian calico. Cotton trade with India didn't end though. The European trading companies would export Indian cottons to West African market to fund the trans-Atlantic slave trade that was growing quickly. European cottons were also imported to Africa. At first they didn't have great demand as they were so lacking compared to Indian cotton, but by the mid 1700s quality of English cotton had improved enough to be competitive.

Inventions in industrial textile machinery, specifically spinning jenny in 1780s and water frame in 1770s, would finally give England the advantages they needed to conquer the cotton market. These inventions allowed producing very cheap but good quality cotton and fabric printing, which would finally produce decent imitations of Indian calico in large quantities. Around the same time in mid 1700s, The East Indian Company had taken over Bengal and soon following most of the Indian sub-continent, effectively putting it under British colonial rule (but with a corporate rule dystopian twist). So when industrialized English cotton took over the market, The East India Company would suppress Indian textile industry to utilize Indian raw cotton production for English textile industry and then import cotton textiles back to India. In 1750s India's exports were mainly fine cotton and silk, but during the next century Indian export would become mostly raw materials. They effectively de-industrialized India to industrialize England further.

India, most notably Bengal area, had been an international textile hub for millennia, producing the finest cottons and silks with extremely advance techniques. Loosing cotton textile industry devastated Indian local economies and eradicated many traditional textile craft skills. Perhaps the most glaring example is that of Dhaka muslin. Named after the city in Bengal it was produced in, it was extremely fine and thin cotton requiring very complicated and time consuming spinning process, painstakingly meticulous hand-weaving process and a very specific breed of cotton. It was basically transparent as seen depicted in this Mughal painting from early 17th century.

It was used by e.g. the ancient Greeks, Mughal emperors and, while the methods and it's production was systematically being destroyed by the British to squash competition, it became super fashionable in Europe. It was extremely expensive, even more so than silk, which is probably why it became so popular among the rich. In 1780s Marie Antoinette famously and scandalously wore chemise a la reine made from multiple layers of Dhaka muslin. In 1790s, when the empire silhouette took over, it became even more popular, continuing to the very early 1800s, till Dhaka muslin production fully collapsed and the knowledge and skill to produce it were lost. But earlier this year, after years lasting research to revive the Dhaka muslin funded by Bangladeshi government, they actually recreated it after finding the right right cotton plant and gathering spinners and weavers skilled in traditional craft to train with it. (It's super cool and I'm making a whole post about it (it has been in the making for months now) so I won't extend this post more.)

Marie Antoinette in the famous painting with wearing Dhaka muslin in 1783, and empress Joséphine Bonaparte in 1801 also wearing Dhaka muslin.

While the trans-Atlantic slave trade was partly funded by the cotton trade and industrial English cotton, the slave trade would also be used to bolster the emerging English cotton industry by forcing African slaves to work in the cotton plantations of Southern US. This produced even more (and cheaper (again slave labor)) raw material, which allowed the quick upward scaling of the cotton factories in Britain. Cotton was what really kicked off the industrial revolution, and it started in England, because they colonized their biggest competitor India and therefore were able to take hold of the whole cotton market and fund rapid industrialization.

Eventually the availability of cotton, increase in ready-made clothing and the luxurious reputation of cotton lead to cotton underwear replacing linen underwear (and eventually sheets) (the far superior option for the reasons I talked about here) in early Victorian Era. Before Victorian era underwear was very practical, just simple rectangles and triangles sewn together. It was just meant to protect the outer clothing and the skin, and it wasn't seen anyway, so why put the relatively scarce resources into making it pretty? Well, by the mid 1800s England was basically fully industrialized and resource were not scarce anymore. Middle class was increasing during the Victorian Era and, after the hard won battles of the workers movement, the conditions of workers was improving a bit. That combined with decrease in prices of clothing, most people were able to partake in fashion. This of course led to the upper classes finding new ways to separate themselves from lower classes. One of these things was getting fancy underwear. Fine cotton kept the fancy reputation it had gained first as an exotic new commodity in late 17th century and then in Regency Era as the extremely expensive fabric of queens and empresses. Cotton also is softer than linen, and therefore was seen as more luxurious against skin. So cotton shifts became the fancier shifts. At the same time cotton drawers were becoming common additional underwear for women.

It wouldn't stay as an upper class thing, because as said cotton was cheap and available. Ready-made clothing also helped spread the fancier cotton underwear, as then you could buy fairly cheaply pretty underwear and you didn't even have to put extra effort into it's decoration. At the same time cotton industry was massive and powerful and very much eager to promote cotton underwear as it would make a very steady and long lasting demand for cotton.

In conclusion, cotton has a dark and bloody history and it didn't become the standard underwear fabric for very good reasons.

Here's couple of excellent sources regarding the history of cotton industry:

The European Response to Indian Cottons, Prasannan Parthasarathi

INDIAN COTTON MILLS AND THE BRITISH ECONOMIC POLICY, 1854-1894, Rajib Lochan Sahoo

#i have fixed the wording in the beginning so it doesn't sound like i'm saying cotton in general dyed better than wool or silk#answers#fashion history#historical fashion#history#textile history#dress history#historical clothing#indian history#colonial history#indian textiles#cotton#slavery

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Robe à la Française

French, ca. 1770

The robe à la française, with open robe and petticoat, was the quintessential dress of the eighteenth century. Characteristic of 1770s costume are the piece's low neckline, fitted bodice, narrow sleeves with double layered cuffs, as well as the sack back and fullness at the hips supported by panniers. This exquisite example is constructed from a rare Chinese export silk dating from the first quarter of the eighteenth century. The textile is an ivory "bizarre" patterned damask (created by reversing the weave structure so that both the warp-float and weft-float faces of the satin are on the same surface).

As early as the late sixteenth century, Chinese craftsmen created silks for the European market, which were exported by the East India companies of England, France, and Holland. Due to the exchange of design motifs by both Eastern and Western artisans, Chinese export silks often bore little relation to traditional Chinese aesthetics. While this patterned damask closely resembles the European "bizarre" silks popular during the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the selvedge-to-selvedge width, fabric weight, and selvedge markings all indicate Chinese manufacture. To fully appreciate the sumptuousness of this dress, one might imagine the sense of movement candlelight would have created across its surface.

The MET Museum

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sophie of France by Lie Louis Perin-Salbreux, 1770-1774.

#classic art#painting#lie louis perin salbreux#french artist#18th century#portrait#female portrait#indoor portrait#princess#house of bourbon#fashion#blue dress#books#desk#chair

129 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! So this is gonna sound weird, but I’ve kinda been learning about Irish history backwards? Like, I started with the Troubles (bc of family involvement), then back to the 1916 rising which got me more interested in the people involved which took me further back and etc etc. I know I’ve been doing it “wrong” but I’m just starting to come up to the 1798. Do you happen to have any recommended readings or particular persons of interest to read? Any collections of primary sources would be more than welcome!

Secondary sources I would recommend:

The Year of Liberty by Thomas Pakenham - about the rebellion in general

The People's Rising by Daniel Gahan - about the rebellion in Wexford

The Summer Soldiers by ATQ Stewart - about the rebellion in Ulster

Wolfe Tone: Prophet of Irish Independence by Marianne Elliott - about Wolfe Tone

The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken by Mary McNeill - technically this is just about Mary Ann but I think it's pretty good for Henry Joy McCracken too because there aren't many biographies of him

Orangeism in Ireland and Britain 1795 - 1836 by Hereward Senior - obviously exercise caution on whether or not you think you can mentally handle this subject but book about loyalism during 1798

Castlereagh: War, Enlightenment, and Tyranny by John Bew - about Lord Castlereagh

2 things that I would also recommend reading about for context are the French Revolution and the British radical movement of the late 18th century. for the French Revolution 1 book I would say is good is Liberty or Death by Peter McPhee and for the British radical movement... the book The English Jacobins by Carl B Cone does a good enough job

Primary sources:

The Memoirs of Theobald Wolfe Tone by Theobald Wolfe Tone - title is pretty self explanatory. It's Tone's account of his own life + his diary

The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times by RR Madden - this is considered to be the 1st history of the rising & was written with the help of many people who lived through it, so it includes a lot of first hand accounts. HOWEVER. beware that Madden was your archetypical mid 19th century Catholic Irish nationalist and the bias created due to that shows through in every single part of these books

Memoirs of the different Rebellions in Ireland by Sir Richard Musgrave - this is another very early history of the rising, also written with the help of people who lived through, also including a lot of first hand accounts. HOWEVER. Musgrave is like Madden's Orange counterpart in that this book is also wildly biased and should also be read with a degree of caution

Personal Narrative of the "Irish Rebellion" of 1798, Sequel to Personal Narrative of the "Irish Rebellion" of 1798, and History and Consequences of the Battle of the Diamond by Charles Hamilton Teeling - 3 accounts of politics in Ireland in the 1790s written by someone who as a young man led the Catholic paramilitary the Defenders

The Drennan letters (a collection of letters that Belfast doctor William Drennan and his sister, Martha McTier, wrote to each other between the 1770s and 1820s), if you can find them, are another great primary source on both the United Irishmen & on what life was like back then in general, as are the McCracken letters, which I know are available free online somewhere I just can't remember where exactly I got the pdf from

There are a lot of them but if you're interested in primary sources you might also read some of the political pamphlets/books that were going around back then -- the most famous that come to mind in this context are Wolfe Tone's Argument on Behalf of the Catholics in Ireland, Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man, and Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France but there are wayyy more than that and at least some of them are on the internet archive

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pale Green Taffeta Dress, 1775-1785, French.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris.

#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#green#18th century#1775#1770s#1780s#1770s dress#1780s dress#1770s france#1780s France#mad paris#musée des arts décoratifs paris#France#French#reign: louis xvi#1776#1777#1778#1779#1780#1781#1782#1783#1784#1785#1770s extant garment#1780s extant garment

260 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1770-1780 Man’s waistcoat for habit à la française (France)

taffeta, yarn

(National Museum, Kraków)

517 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Woman’s Dress (Robe à la française). France (1760s-1770s).

Silk taffeta.

Images and text information courtesy LACMA.

394 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weapons in the American Revolution

The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) was a long and bitter conflict fought between Great Britain and its thirteen North American colonies over the Americans' liberties and, eventually, for the independence of the United States. The war, which was fought with both conventional linear tactics and guerilla-style warfare, utilized several different kinds of weapons for multiple styles of combat.

Some of the weapons used in the Revolutionary War had long been staples of European-style warfare. Variations of the flintlock musket, for instance, had been used in battle since the early 1600s and would continue to be used on Western battlefields for decades after the American Revolution had ended. Other weapons, like the groove-barreled Long Rifle, were relatively new additions to warfare; the rifle, used in a limited capacity during the Revolution, would see greater use on the later battlefields of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) and American Civil War (1861-1865). Some weapons were useful in close-quarter combat such as the bayonet, tomahawk, and saber, while artillery guns were devastating at both long and short distances. None of the weapons discussed in this article were unique to the American Revolution. However, a quick description of the types of weapons used in that conflict could help give the reader a better understanding of what it may have been like to be on a battlefield during the US War of Independence.

Flintlock Muskets

The flintlock musket was the primary weapon of 18th-century European armies and was therefore used by both sides during the American Revolution. A musket was a muzzle-loading, smoothbore weapon that fired a large lead ball with reasonably decent accuracy. By the 1770s, a typical musket weighed about 10 lbs (4.5 kg), was about 5 ft (152 cm) in length, and had a caliber of about .75 (1.9 cm). A typical lead ball weighed about an ounce (28 g). As the name 'flintlock musket' suggests, such weapons relied on a flintlock mechanism to fire. This involved a piece of flint contained within the musket's cock, or hammer. When the trigger was pulled, the hammer would swing forward, causing the flint to strike a piece of steel called the 'frizzen'. This action created a spark that would fall into a flash pan below, wherein a small charge of black powder was contained. The spark would ignite the powder, which would, in turn, discharge the bullet from the gun barrel. By the time of the revolution, flintlocks had long been the most common kind of firearm; the flintlock had been developed in France in the early 1600s to replace the earlier matchlock and wheellock mechanisms and would remain in use until the mid-19th century.

Although the process of firing a flintlock musket sounds complicated on paper, a well-trained 18th-century soldier could typically fire three or four shots per minute. This is quite impressive, especially after considering what the loading process entails. A soldier would first take a pre-rolled musket cartridge – a paper tube containing gunpowder and a lead musket ball – and tear it open with his teeth. He would then pour a small amount of the powder into the flash pan and pour the rest down the muzzle. Next, the soldier would use a ramrod to pack the musket ball, powder, and paper of the cartridge down into the breech. Only after returning the ramrod to its place and fully cocking back the hammer was the soldier finally ready to take aim and fire.

The musket could be effectively fired from a range of about 80 yards (73 m); while it could sometimes be effective at a slightly greater range, musket balls rarely traveled more than 150 yards (137 m). The musket's accuracy largely depended, of course, on the man who wielded it. To increase the effectiveness of the weapon, 18th-century armies adopted the style of linear warfare; an individual musketeer was less likely to inflict damage than a line of soldiers firing coordinated, concentrated volleys. A typical battle line consisted of two or three ranks of soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder, with each man allowed just enough space to be able to present arms, fire, and reload. When the officer gave the order, the line of soldiers would fire in sync with one another (referred to as a musket volley); sometimes the first rank would kneel to give the second rank a better shot, thereby keeping up a higher rate of fire.

Continue reading...

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bottle Ticket for Claret, c. 1805

The word claret on this bottle ticket is the English name for the light red wine from Bordeaux in south-west France. It was processed for the English market into a strong wine with a good flavour, but which was "intoxicating and not suitable for all stomachs". The anchor here indicates that this claret was served in the wardroom or Great Cabin aboard a ship.

Bottle tickets labelled the contents of a bottle or carafe, which could also contain spirits, sauces, toilet water or spirits. Contemporary gazettes have referred to "bottle tickets" since the 1770s, but it was not until the 1790s that they were established as wine or carafe labels.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is not often that auction houses provide high resolution photos, but Kerry Taylor is a wonderful exception. This 1770 robe à la Française gown is EVERYTHING.

And I couldn't be happier given this particular gown. It's got two features I particularly squee about: gold brocade and a quilted petticoat. It's got silk for miles, and that delicate floral pattern of stripes and texture really works to the advantage of brocade. The quilted petticoat, which has been in and out in terms of fashion for some time at this point, is a gorgeous merlot hue in contrast. The note from the auction house says it's an early 19th century addition, but it still keeps with the dress's look and feel.

You'll notice we've got some wide hips here, but with a slant downward as starts happening at this time--moving toward more of a bell shape rather than the straight out panniers. Due to the shaping on the dress, I immediately thought it must be continental, and I was right. The note says it's either Spanish or Italian. You often see that lower drop at the bodice outside of England and France at this time.

A stunning gown that is both elegant and slightly understated (compared to some of its contemporaries) yet maintains a sense of decadence and sumptuousness all the same.

#fashion history#textiles#historical costuming#silk dress#costume history#costume#threadtalk#history of fashion#1770s style#1770s fashion#historic fashion#historic costume#brocade#petticoat

252 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you don't mind answering, what exactly makes something macaroni?

A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785) defines macaroni as follows:

An Italian paste made of flour and eggs; also a fop, which name arose from a club, called the maccaroni club, instituted by some of the most; dressy travelled gentlemen about town, who led the fashions, whence a man foppishly dressed, was supposed a member of that club, and by contraction stiled a maccaroni.

To put it simply a macaroni was a fop. That is a man who is too interested in fashion. Because interest in fashion was considered a frivolous female trait men who were "foppishly dressed" were often ridiculed for their gender nonconformity. The Natural History of a Macaroni describes the macaroni as follows:

There has within these few years past arrived from France and Italy a very strange animal, of the doubtful gender, in shape somewhat between a man and monkey, which has generated so much within that time, that they form at present no inconsiderable groupe in most of the public circles about town.

Its natural height is somewhat inferior to the ordinary size of men, though by the artificial height of their heels, they in general reach that standard; the face is quite effeminate, but sometimes distinguished by a little hair growing on it like a beard; the fore legs, or arms, are disproportionably long, the hind legs of a slender make.

Its dress is neither in the habit of a man or woman, but peculiar to itself, and varying with the day; at present it is principally discovered by an Indian flesh-coloured cloth, or silk, clasped all over with broad shining steel, and buttoned at the neck with a large black collar;

~ Walker’s Hibernian Magazine, July 1777, p458

The term macaroni really just means effeminate if someone or something was perceived as effeminate it was macaroni.

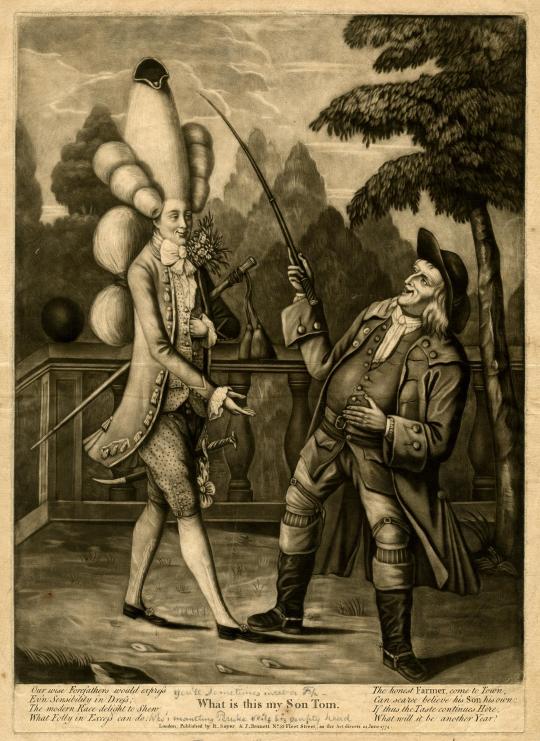

However as the term was predominantly used in the 1770s and 1780s it's associated with the fashion from those decades. So while there isn't strict rules dictating what is and isn't macaroni there are certainly some key aspects to the fashion that come up a lot in satire.

The Hair

Probably the most iconic aspect of macaroni fashion was the height of the hair. This was mocked in the satirical print What is this my son Tom. However in reality the hair was not worn that tall. Compare the caricature to Richard Cosway's self-portrait in which he is depicted wearing the fashionable style.

[Left: What is this my son Tom, print, c.1774, published by Sayer & Bennett, via The British Museum.

Right: Self-Portrait, Ivory, c.1770–75, by Richard Cosway, via The Met.]

The Suit

Menswear of the period consisted of the same basic elements; shirt, stockings, breeches, waistcoat and coat. At a time when English menswear was characterised by plain monochrome broadcloth macaroni fashion was disguised by the fabric, cut, colour and trimmings of the suit. Fashionable were the tightly cut French style suits known as habit à la française. Popular were brocaded and embroidered silks and velvets, sometimes further embellished with metallic sequins, simulated gemstones and raised metallic threads. In contrast to the black suit worn by many Englishmen, macaroni wore pastels, pea-green, pink, purple, red and deep orange.

[Left: The Illiterate Macaroni, print, c.1772, by Matthew Darly, via Lewis Walpole Library.

Middle: The Sleepy Macaroni, print, c.1772, by Matthew Darly, via Lewis Walpole Library.

Right: The Catgut Macaroni, print, c.1772, by Matthew Darly, via Lewis Walpole Library.]

The Accessories

But a macaroni's ensemble was not done without accessories. Some examples of popular accessories include red heeled shoes, shoe strings, dress swords, canes, nosegays and muffs.

[Such Things Are, watercolour, c.1787, by Captain Mercer, via Lewis Walpole Library.]

If you want to learn more about macaroni I highly recommend reading Pretty Gentleman by Peter McNeil.

67 notes

·

View notes