#pontum

Text

Today in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Minerva pays a visit to the Muses

Hactenus aurigenae comitem Tritonia fratri 250

se dedit; inde cava circumdata nube Seriphon

deserit, a dextra Cythno Gyaroque relictis,

quaque super pontum via visa brevissima, Thebas

virgineumque Helicona petit. quo monte potita

constitit et doctas sic est adfata sorores: 255

‘fama novi fontis nostras pervenit ad aures,

dura Medusaei quem praepetis ungula rupit.

is mihi causa viae; volui mirabile factum

cernere; vidi ipsum materno sanguine nasci.’

excipit Uranie: ‘quaecumque est causa videndi 260

has tibi, diva, domos, animo gratissima nostro es.

vera tamen fama est: est Pegasus huius origo

fontis’ et ad latices deduxit Pallada sacros.

quae mirata diu factas pedis ictibus undas

silvarum lucos circumspicit antiquarum 265

antraque et innumeris distinctas floribus herbas

felicesque vocat pariter studioque locoque

Mnemonidas

"During all this time Tritonia (Minerva) had been the comrade of her brother born of the golden shower. But now, wrapped in a hollow cloud, she left Seriphus, and, passing Cythnus and Gyarus on the right, by the shortest course over the sea she made for Thebes and Helicon, home of the Muses. On this mountain she alighted, and thus addressed the sisters versed in song: “The fame of a new spring has reached my ears, which broke out under the hard hoof of the winged horse of Medusa. This is the cause of my journey: I wished to see the marvellous thing. The horse himself I saw born from his mother’s blood.” Urania replied: “Whatever cause has thee to see brought our home, O goddess, thou art most welcome to our hearts. But the tale is true, and Pegasus did indeed produce our Spring.” And she led Pallas aside to the sacred waters. She long admired the spring made by the stroke of the horse’s hoof; then looked round on the ancient woods, the grottoes, and the grass, spangled with countless flowers. She declared the daughters of Mnemosyne to be happy alike in their favourite pursuits and in their home." (Transl. Miller 1915)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laocoon

Jener bemüht sich der Knoten Gewirr mit den Händen zu trennen;

Geifer und schwärzliches Gift umströmt ihm die heiligen Binden;

Grässlich ertönt sein Jammergeschrei empor zu den Sternen,

Gleich dem Gebrülle des Stiers, wenn verwundet er von dem Altar flieht

Und von dem Nacken das Beil, das schwankend geführte, sich schüttelt.

***

Laocoon, ductus Neptuno sorte sacerdos,

sollemnis taurum ingentem mactabat ad aras.

ecce autem gemini a Tenedo tranquilla per alta

- horresco referens - immensis orbibus angues

incumbunt pelago pariterque ad litora tendunt;

pectora quorum inter fluctus arrecta iubaeque

sanguineae superant undas, pars cetera pontum

pone legit sinuatque immensa volumine terga.

fit sonitus spumante salo; iamque arva tenebant

ardentisque oculos suffecti sanguine et igni

sibila lambebant linguis vibrantibus ora.

diffugimus visu exsangues. illi agmine certo

Laocoonta petunt; et primum parva duorum

corpora natorum serpens amplexus uterque

implicat et miseros morsu depascitur artus;

post ipsum auxilio subeuntem ac tela ferentem

corripiunt spirisque ligant ingentibus; et iam

bis medium amplexi, bis collo squamea circum

terga dati superant capite et cervicibus altis.

ille simul manibus tendit divellere nodos

perfusus sanie vittas atroque veneno,

clamores simul horrendos ad sidera tollit:

qualis mugitus, fugit cum saucius aram

taurus et incertam excussit cervice securim.

at gemini lapsu delubra ad summa dracones

effugiunt saevaeque petunt Tritonidis arcem,

sub pedibusque deae clipeique sub orbe teguntur.

tum vero tremefacta novus per pectora cunctis

insinuat pavor, et scelus expendisse merentem

Laocoonta ferunt, sacrum qui cuspide robur

laeserit et tergo sceleratam intorserit hastam.

ducendum ad sedes simulacrum orandaque divae

numina conclamant.

Dividimus muros et moenia pandimus urbis.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today we also celebrate the Holy Deaconess Olympia of Constantinople. Saint Olympia was born 361 AD into a wealthy family of high ranking. Her father was the senator Anicius Secundus and through her mother, Alexandra, she was the granddaughter of the noted eparch Eulalios. After the death of her parents, Olympia inherited great wealth. She distributed this to the poor and needy, the orphaned and the widowed. She was also very generous with her donations to the churches, monasteries, hospices, and shelters for the homeless. She was appointed as a deaconess by the holy Patriarch Nectarius and provided great assistance to the hierarchs of Constantinople, including Amphilochius, the Bishop of Iconium, Onesimus of Pontum, Gregory of Nazianzus, Peter of Sebaste, Ephiphanius of Cyprus. She was great friends with all of these holy great fathers of the church. She was especially close to St. John Chrysostom. He had high regard for Olympia and he showed her goodwill and spiritual love. When the hierarch was unjustly banished, Olympia and the other deaconesses (Pentadia, Proklia, and Salbina) were deeply upset. Her generosity also greatly benefited the Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria. He, however, turned against her for her devotion to St. John Chrysostom and other monks whom he had him banished into the Egyptian desert. Olympia would provide food and shelter whenever they were in Constantinople so he began to campaign unjust accusations against her to cast doubt on her holy life. After the repose of St. John Chrysostom on September 14, 407, Olympia passed away in exile somewhere in Nicomedia on July 25, 408. Shortly before her death, Olympia gave instructions that she wanted her remains to be placed in a coffin and tossed into the sea, leaving her final resting place to divine providence. The letters of correspondence between Olympia and John Chrysostom present us with valuable insight into their Christ-centred relationship. May she intercede for us always + Source: https://orthodoxwiki.org/Olympia_the_Deaconess (at Constantinople - Κωνσταντινούπολη) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgZ9esEvNbl/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Olympias the Deaconess was the daughter of the senator Anicius Secundus, and by her mother she was the granddaughter of the noted eparch Eulalios (he is mentioned in the life of Saint Nicholas). Before her marriage to Anicius Secundus, Olympias’s mother had been married to the Armenian emperor Arsak and became widowed. When Saint Olympias was still very young, her parents betrothed her to a nobleman. The marriage was supposed to take place when Saint Olympias reached the age of maturity. The bridegroom soon died, however, and Saint Olympias did not wish to enter into another marriage, preferring a life of virginity.

After the death of her parents she became the heir to great wealth, which she began to distribute to all the needy: the poor, the orphaned and the widowed. She also gave generously to the churches, monasteries, hospices and shelters for the downtrodden and the homeless.

Holy Patriarch Nectarius (381-397) appointed Saint Olympias as a deaconess. The saint fulfilled her service honorably and without reproach.

Saint Olympias provided great assistance to hierarchs coming to Constantinople: Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium, Onesimus of Pontum, Gregory the Theologian, Saint Basil the Great’s brother Peter of Sebaste, Epiphanius of Cyprus, and she attended to them all with great love. She did not regard her wealth as her own but rather God’s, and she distributed not only to good people, but also to their enemies.

Saint John Chrysostom (November 13) had high regard for Saint Olympias, and he showed her good will and spiritual love. When this holy hierarch was unjustly banished, Saint Olympias and the other deaconesses were deeply upset. Leaving the church for the last time, Saint John Chrysostom called out to Saint Olympias and the other deaconesses Pentadia, Proklia and Salbina. He said that the matters incited against him would come to an end, but scarcely more would they see him. He asked them not to abandon the Church, but to continue serving it under his successor. The holy women, shedding tears, fell down before the saint.

Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria (385-412), had repeatedly benefited from the generosity of Saint Olympias, but turned against her for her devotion to Saint John Chrysostom. She had also taken in and fed monks, arriving in Constantinople, whom Patriarch Theophilus had banished from the Egyptian desert. He levelled unrighteous accusations against her and attempted to cast doubt on her holy life.

After the banishment of Saint John Chrysostom, someone set fire to a large church, and after this a large part of the city burned down.

All the supporters of Saint John Chrysostom came under suspicion of arson, and they were summoned for interrogation. They summoned Saint Olympias to trial, rigorously interrogating her. They fined her a large sum of money for the crime of arson, despite her innocence and a lack of evidence against her. After this the saint left Constantinople and set out to Kyzikos (on the Sea of Marmara). But her enemies did not cease their persecution. In the year 405 they sentenced her to prison at Nicomedia, where the saint underwent much grief and deprivation. Saint John Chrysostom wrote to her from his exile, consoling her in her sorrow. In the year 409 Saint Olympias entered into eternal rest.

Saint Olympias appeared in a dream to the Bishop of Nicomedia and commanded that her body be placed in a wooden coffin and cast into the sea. “Wherever the waves carry the coffin, there let my body be buried,” said the saint. The coffin was brought by the waves to a place named Brokthoi near Constantinople. The inhabitants, informed of this by God, took the holy relics of Saint Olympias and placed them in the church of the holy Apostle Thomas.

Afterwards, during an invasion of enemies, the church was burned, but the relics were preserved. Under the Patriarch Sergius (610-638), they were transferred to Constantinople and put in the women’s monastery founded by Saint Olympias. Miracles and healings occurred from her relics.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Sunday, January 14, 2024

janauary 1_january 14

The Circumcision of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT, ARCHBISHOP OF CAESAREA CAPPADOCIA

Saint Basil the Great, Archbishop of Caesarea Cappadocia, "belongs not to the Church of Caesarea alone, nor merely to his own time, nor to his own kinsmen was he merely of benefit, but rather to all lands and cities worldwide, and to all people he brought and yet brings benefit, and for Christians he always was and will be a teacher most salvific", – thus spoke the contemporary of Saint Basil, – Saint Amphylokhios, Bishop of Iconium (+ 344, Comm. 23 November).

Saint Basil was born in about the year 330 in Caesarea, the administrative center of Cappadocia. He was of illustrious lineage, famed for its eminence and wealth, and giftedly zealous for the Christian faith. During the time of persecution under Diocletian, the saint's grandfather and grandmother on his father's side had to hide away in the forests of Pontum for seven years. The mother of Saint Basil – Saint Emilia (Emily), was the daughter of a martyr. The father of Saint Basil was also named Basil: he was a lawyer and renowned rhetorician and had always lived in Caesarea. Ten children were born into the family of this elder Basil – five sons and five daughters. Out of these, five were later enumerated to the ranks of the Saints: Basil the Great; Macrina (Comm. 19 July) – was an exemplar of ascetic life, and exerted a strong influence on the life and character of Saint Basil the Great; Gregory, afterwards Bishop of Nyssa (Comm. 10 January); Peter, Bishop of Sebasteia (Comm. 9 January); and Righteous Theozua – a deaconess (Comm. 10 January). Saint Basil spent the first years of his life on an estate belonging to his parents at the River Irisa, where he was raised under the supervision of his mother, Emilia, and grandmother, Macrina. They were women of excellent refinement, preserving in memory the tradition of an earlier saint hierarch of Cappadocia – Saint Gregory Thaumatougos (Wonderworker) (+ c. 266-270, Comm. 17 November). Basil received his initial education under the supervision of his father. Then he studied under the finest teachers in Caesarea Cappadocia, and it was here that he made the acquaintance of Saint Gregory the Theologian (Bogoslov, i.e. title of Saint Gregory Nazianzus; Comm. 25 January and 30 January). Later on, Basil transferred to school at Constantinople, where he listened to eminent orators and philosophers. For his education's finishing touches, Saint Basil set off to Athens – a center of classical enlightenment.

After a four or five year stay at Athens, Basil the Great had mastered all the available disciplines: "He so thoroughly studied everything, more than others are wont to study a single subject, each science he studied to its very totality, as though he would study naught else". Philosopher, philologist, orator, jurist, naturalist, possessing profound knowledge in astronomy, mathematics and medicine, – "this was a ship, loaded down full of learning, to the extent allowed of by human nature". At Athens a close friendship developed between Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian (Nazianzus), which continued throughout all their life. Later on, in an eulogy to Basil the Great, Saint Gregory the Theologian speaks with delight about this period: "Various hopes guided us and in deed inevitably – in learning... Two paths opened up before us: the one – to our sacred temples and the teachers therein; the other – towards preceptors of disciplines beyond".

In about the year 357 Saint Basil returned to Caesarea, where for a certain while he devoted himself to rhetoric. But soon, refusing offers from Caesarea citizens wanting to entrust him with the education of their offspring, Saint Basil entered upon the path of ascetic life.

After the death of her husband, Basil's mother together with her eldest daughter Macrina and several maid-servants withdrew to the family estate at Irisa and there began to lead an ascetic life. Basil, however, having accepted Baptism from the bishop of Caesarea Dianios, was ordained a reader. As an expounder of the Sacred Scriptures, he at first read them to the people. Later on, "wanting to acquire a guide to the knowledge of truth", the saint undertook a journey into Egypt, Syria and Palestine, – to the great Christian ascetics dwelling there. Upon returning to Cappadocia, he decided to do likewise. Having given his wealth to the needy, Saint Basil settled on the opposite side of the river not far from his mother Emilia and sister Macrina, gathering around him monks living in common community. Through his letters, Basil the great attracted to the wilderness monastery his good friend Gregory the Theologian. Saints Basil and Gregory asceticised amidst strict abstinence in their hovel, without roof and without fireplace, and the food was very humble. They themselves heaved the stones, planted and watered the trees, and carried heavy loads. Their hands were constantly calloused from the hard work. For clothing Basil the great had only chiton-tunic and monastic mantle; the hairshirt he wore only at night, so that it would not be obvious. In their solitude, Saints Basil and Gregory occupied themselves in an intense study of Holy Scripture with manuscript guidances from the most ancient commentators, and in parts Origen also – from all whose works they compiled an anthology – a Philokalia. Also at this time, at the monks' request, Basil the Great wrote down a collection of rules for a virtuous life. By his preachings and example, Saint Basil the Great assisted in the spiritual perfecting of Christians in Cappadocia and Pontus, and many indeed turned to him. Monasteries were organized for men and women, and Basil sought to unite the coenobitic (koine-bios or life in common) lifestyle with that of the solitary hermit.

During the reign of Constantius (337-361) the heretical false-teachings of Arius spread about, and the Church summoned both its saints into service. Saint Basil returned to Caesarea. In the year 362 he was ordained deacon by the bishop of Antioch, Meletios; later on, in 364 he was ordained to the dignity of priest by the bishop of Caesarea, Eusebios. "But seeing, – as Gregory the Theologian relates, – that everyone exceedingly praised and honoured Basil for his wisdom and reverence, Eusebios, through human weakness, succumbed to jealousy of him, and began to show dislike for him". The monks rose up in defense of saint Basil. To avoid causing Church discord, Basil withdrew to his own monastery and concerned himself with the organisation of monasteries. With the coming to power of the emperor Valens (364-378), who was a resolute adherent of Arianism, there began for Orthodoxy the onset of a time of troubles – "the onset of the great struggle". Saint Basil then hastily returned to Caesarea at the call of bishop Eusebios. In the words of Gregory the Theologian, he was for bishop Eusebios "a good advisor, a righteous representative, an expounder of the Word of God, a staff for the aged, a faithful support in matters internal, and an activist in matter external". From this time church governance passed over to Basil, though he was subordinate to the hierarch. He preached daily, and often twice so – in the morning and in the evening. And during this time Saint Basil compiled the order of his Liturgy; he wrote a work "Discourse on the Six Days" and another in 16 Chapters on the Prophet Isaiah, yet another on the Psalms, and also a second compilation of monastic rules. Saint Basil wrote also Three Books "Against Eunomios", an Arian teacher who with the help of Aristotelian concepts had presented the Arian dogmatics in learnedly philosophic form, converting the Christian teaching into a logical scheme of rationalist concepts.

Saint Gregory the Theologian, speaking about the activity of Basil the Great during this period, points to "the caring for the destitute and the taking in of strangers, the supervision of virgins, written and unwritten monastic rule for the monasticism, the arrangement of prayers (Liturgy), the felicitous arrangement of altars and other things". Upon the death of the bishop of Caesarea Eusebios, Saint Basil in the year 370 was elevated onto his cathedra-chair. As Bishop of Caesarea, Saint Basil the Great was the newest bishop in rank of 50 in eleven provinces. Saint Athanasius the Great (Comm. 2 May), with joy and with thanks to God, welcomed the bestowing of Cappadocia with such a bishop as Basil, famed for his reverence, deep knowledge of Holy Scripture, great learning, and his efforts for the welfare of Church peace and unity. In the empire of Valens, the external government belonged to the Arians, who held various opinions on questions of the Divinity of the Son of God and hence were divided into several factions. And to these dogmatic disputes were connected questions about the Holy Spirit. In his book "Against Eunomios", Saint Basil the Great taught about the Divinity of the Holy Spirit and Its Oneness with the Father and the Son. Subsequently, for a full explanation of the Orthodox teaching on this question, – at the request of the Bishop of Iconium Saint Amphylokhios, Saint Basil wrote his book "About the Holy Spirit".

The generally sorry state of affairs for the Caesarea bishop was made even worse by various circumstances: Cappadocia was divided in two under the re-arrangement of governance of provincial districts. Then, too, at Antioch, a schism occurred, occasioned by the ordination of a second bishop. There were Western bishops' negative and haughty attitudes to the attempts to draw them into the struggle with the Arians. And there was also the departure over to the Arian side by Eustathios of Sebasteia, with whom Basil had been connected by close friendship. Amidst the constant perils, Saint Basil encouraged the Orthodox, affirmed them in the faith, summoning them to bravery and endurance. The holy bishop wrote numerous letters to the Churches, bishops, clergy, and individuals. Overcoming the heretics "by the weapon of his mouth and by the arrows of his letters," as an untiring champion of Orthodoxy, Saint Basil all his life gave a challenge to the hostility and the every which way possible intrigues of the Arian heretics.

The emperor Valens, mercilessly dispatching any bishops that displeased him into exile and having implanted Arianism into other Asia Minor provinces, suddenly appeared in Cappadocia for precisely this purpose. He sent off to Saint Basil, the prefect Modestus, who began to threaten the saint with ruin, banishment, beatings, and even death by execution. "All this, – replied Basil, – for me means nothing, since one cannot be deprived of possessions that one does not have, beyond some old worn-out clothing and some books, which comprise the entirety of my wealth. For me, it would not be an exile since I am bound to no particular place, and this place in which I now dwell is not mine, and indeed any place whither I will be cast shalt be mine. Better it is to say: everywhere is the place of God, whither be naught stranger nor newcomer (Ps. 38 [39]: 13). And what tortures can ye do me? – I am so weak that merely but the very first blow will be felt. Death for me would be an act of kindness: it wilt bring me all the sooner to God, for Whom I live and do labor, and to Whom moreover I do strive". The official was bewildered by such an answer. "Perhaps, – continued the saint, – thou hast never had an encounter with a bishop; otherwise, without doubt, thou wouldst have heard such words. In all else, we are meek, the most humble of all, and not only before the mighty but also before all since such is prescribed for us by the law. But when it is a matter concerning God, and they make bold to rise up against Him, then we – being mindful of naught else, think only of Him alone, and then fire, sword, wild beasts and chains, the rending of the body, would sooner hold satisfaction for us, than to be afraid".

Reporting to Valens on the not-to-be-intimidated Saint Basil, Modestus said: "Emperor, we stand defeated by a leader of the Church". Basil the Great again showed firmness, and in front of the very person of the emperor himself and his retinue produced such a strong impression on Valens that the emperor dared not give in to the Arians demanding the exile of Basil. "On the day of Theophany, amidst an innumerable multitude of the people, Valens entered the church and mixed in amidst the throng to give the appearance of unity with the Church. When the singing of psalmody began in the church, it was like thunder to his hearing. The emperor beheld a sea of people, and in the altar and all around was splendor; in front of all was Basil, acknowledging neither by gesture nor by glance, as though in the church was occurred aught else, than that everything was intent only on God and the altar-table, and the clergy thereat in awe and reverence".

Saint Basil almost daily celebrated Divine services. He was particularly concerned about the strict fulfillment of the canons of the Church and kept attentive watch so that only worthy individuals should enter the clergy. He incessantly made the rounds of his own church, lest anywhere there be an infraction of Church discipline and setting aright any unseemliness. At Caesarea, Saint Basil built two monasteries, a men's and a women's, with a church in honor of 40 Martyrs whose relics were buried there. On the example of monks, the metropolitan clergy of the saint – even deacons and priests- lived in remarkable poverty and toil and led lives of chasteness and virtue. For his clergy, Saint Basil got an exemption from taxes. All his wealth and the income proceeds from his church he used for the benefit of the destitute; in every center of his diocese, he built a poor house at Caesarea – a home for wanderers and the homeless.

Since youth, the toil of teaching, efforts at abstinence, the concerns and sorrows of pastoral service early sapped the saint's strength. Saint Basil died on 1 January 379 at age 49. Shortly before his death, the saint blessed Saint Gregory, the Theologian, to enter the Constantinople cathedra-chair.

Upon the repose of Saint Basil, the Church immediately began to celebrate his memory. Saint Amphylokhios, Bishop of Iconium (+ 394), in his eulogy to Saint Basil the Great, said: "It is neither without reason nor by chance that holy Basil hath taken leave from the body and had repose from the world unto God on the day of the Circumcision of Jesus, celebrated betwixt the day of the Nativity and the day of the Baptism of Christ. This most blessed one, preaching and praising the Nativity and Baptism of Christ, extolling spiritual circumcision, himself forsaking the flesh, doth ascend to Christ now, especially on the sacred day of remembrance of the Circumcision of Christ. Therefore also let be established on this present day annually to honor the memory of Basil the Great festally and solemnly".

© 1996-2001 by translator Fr. S. Janos.

JOHN 21:1-14 (10TH MATINS GOSPEL)

1 After these things Jesus showed Himself again to the disciples at the Sea of Tiberias, and in this way He showed Himself: 2 Simon Peter, Thomas called the Twin, Nathanael of Cana in Galilee, the sons of Zebedee, and two others of His disciples were together. 3 Simon Peter said to them, "I am going fishing." They said to him, "We are going with you also." They went out and immediately got into the boat, and that night they caught nothing. 4 But when the morning had now come, Jesus stood on the shore; yet the disciples did not know that it was Jesus. 5 Then Jesus said to them, "Children, have you any food?" They answered Him, "No." 6 And He said to them, "Cast the net on the right side of the boat, and you will find some." So they cast, and now they were not able to draw it in because of the multitude of fish. 7 Therefore that disciple whom Jesus loved said to Peter, "It is the Lord!" Now when Simon Peter heard that it was the Lord, he put on his outer garment (for he had removed it), and plunged into the sea. 8 But the other disciples came in the little boat (for they were not far from land, but about two hundred cubits), dragging the net with fish. 9 Then, as soon as they had come to land, they saw a fire of coals there, and fish laid on it, and bread. 10 Jesus said to them, "Bring some of the fish which you have just caught." 11 Simon Peter went up and dragged the net to land, full of large fish, one hundred and fifty-three; and although there were so many, the net was not broken. 12 Jesus said to them, "Come and eat breakfast." Yet none of the disciples dared ask Him, "Who are You?"-knowing that it was the Lord. 13 Jesus then came and took the bread and gave it to them, and likewise the fish. 14 This is now the third time Jesus showed Himself to His disciples after He was raised from the dead.

MARK 1:1-8

1 The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. 2 As it is written in the Prophets:"Behold, I send My messenger before Your face, Who will prepare Your way before You." 3 The voice of one crying in the wilderness: 'Prepare the way of the LORD; Make His paths straight.' " 4 John came baptizing in the wilderness and preaching a baptism of repentance for the remission of sins. 5 Then all the land of Judea, and those from Jerusalem, went out to him and were all baptized by him in the Jordan River, confessing their sins. 6 Now John was clothed with camel's hair and with a leather belt around his waist, and he ate locusts and wild honey. 7 And he preached, saying, "There comes One after me who is mightier than I, whose sandal strap I am not worthy to stoop down and loose. 8 I baptized you with water, but He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#bible#gospel#wisdom#saints

0 notes

Text

Propertius 1.6

Non ego nunc Hadriae uereor mare noscere tecum,

I do not now know fear to experience the Adriatic sea with you,

Tulle, neque Aegaeo ducere uela salo,

Tullus, nor to spread sails on the Aegan sea,

cum quo Rhipaeos possim conscendere montes

as with you who I could climb Rhipean moountains with

ulteriusque domos uadere Memnonias;

and further than the house of the Memmon;

sed me complexae remorantur uerba puellae

but the girl's words are lingering in me

mutatoque graues saepe colore preces.

and their changing colours make prayers more serious.

illa mihi totis argutat noctibus ignes,

she babbles her passions to me during the night,

et queritur nullos esse relicta deos;

and complains that if she is abondoned 'there are no gods';

illa meam mihi iam se denegat, illa minatur

she denies that she is any longer mine to me, she threatens

quae solet ingrato tristis amica uiro.

that is usually made by an angry wife to an ungrateful man.

his ego non horam possum durare querelis:

I am not able to endure you complaints in this hour:

a pereat, si quis lentus amare potest.

a perish, if you are one of those who love harshly.

an mihi sit tanti doctas cognoscere Athenas

whether it is for to become well known with learned Athens

atque Asiae ueteres cernere diuitias,

and whether to behold the ancient wealth of Asia

ut mihi deducta faciat conuicia puppi

so that if she conduct the launching of the stern for me

Cynthia et insanis ora notet manibus,

Cynthia that is, and disfugirng my mouth in rage

osculaque opposito dicat sibi debita uento,

she says she owes kisses if the wind is against and on the opposite side

et nihil infido durius esse uiro?

and is nothing more difficult for a faithfuless man?

tu patrui meritas conare anteire secures,

you must strive to get ahead of your own uncle,

et uetera oblitis iura refer sociis.

and restore the law to our ancient allies.

nam tua non aetas umquam cessauit amori,

for your age has never had time for love,

semper at armatae cura fuit patriae.

but always served the fatherland in arms.

et tibi non umquam nostros puer iste labores

and never to you should our boy ((CUPID)) hardships

afferat et lacrimis omnia nota meis.

bring you and my well known tears.

me sine, quem semper uoluit fortuna iacere,

allow me, whom fortune always wants to fall,

hanc animam aeternae reddere nequitiae.

returning my soul to eternal iniquity.

multi longaeuo periere in amore libenter,

many men have perished in a lengthened love willingly,

in quorum numero me quoque terra tegat.

in which i also may be allowed to be placed in the earth,

non ego sum laudi, non natus idoneus armis:

I am no worthy of praise, nor in birth am I helpful in gaining glory in arms:

hanc me militiam fata subire uolunt.

they (the fates) wanted me to undergo this military life.

at tu seu mollis qua tendit Ionia, seu qua

but were, whether soft Ionia extends herself, or where

Lydia Pactoli tingit arata liquor,

Pactolus waters tint Lydian fields,

seu pedibus terras seu pontum remige carpes,

whether you cover land on foot or over sea by oar,

ibis et accepti pars eris imperii.

go and accept be part of your order.

tum tibi si qua mei ueniet non immemor hora,

then if you come to me at any hour in memories,

uiuere me duro sidere certus eris.

know that i owe my living to a cruel star.

0 notes

Text

Bridges to Pax: Chapter One

Eugene Foster had Always thought he was a regular teenager, spite his schizophrenia. When he almost dies in an alleyway, attacked by a monster who definitely shouldn't exist, his life is put into perspective, and he finds out that he belongs to a family with a history of Pontum - people who connect the magical and the human worlds, the so-called "Bridges" - and now he must continue this family tradition. With the mysterious death of his uncle and the threat of a traitor looming over him, he doesn't know if he will be able to hold on.

(ALSO ON TAPAS)

Eugene walked from one side to the other, diverting from plants here and there. The sunlight entered through the yellow stained glass, painting the greenhouse even more as if the colour of the plants and lowers still wasn't enough.

Lazuli still hadn't arrived, but lateness wasn't something rare for the Dracae. Eugene's nervousness wasn't linked to the training that would start as soon as Lazuli arrived. No, he was desperately anxious because of the piece of paper under the daisies near the door. The letter of a dead man.

The circumstances weren't great for Eugene, who had discovered his place in the universe two months ago when he as attacked by a monster in an alleyway, something that definitely shouldn't have happened. When he found out his schizophrenia wasn't real and that the world was more than it seemed. When his best friend had confessed to being a mere bodyguard and that he did not want to be in the place he occupied for seven years. When Eugene saw himself, for the first time, alone.

"Alone". There were people around him. Well, not actually people, but he wasn't in a position to complain. He asked himself if he could call them all friends, especially after receiving a desperate letter from his deceased uncle, the man who occupied his place before he passed away. Words written hastily in a notebook page asked him to not trust anyone.

The door opened, causing Eugene to stop his walk. He breathed in deeply, furrowing his brows and trying not to demonstrate his mistrust when he turned around and faced Lazuli's milky white eyes.

"Laz!" He smiled, putting his hands in his sweatshirt's pocket.

"Why are you nervous?" The Dracae asked, frowning.

"I'm not nervous." He said, staring at the ground. He let out a sigh. "It's just... a bad day, that's all."

It wasn't a lie. That had been an awful day, mainly because of the letter hidden in the greenhouse. He bit his lips, gazing at the daisies that now seemed strangely suspicious. Lazuli did not seem to notice the guilty yellow flowers, because when their eyes deviated from where Eugene looked, their face remained without expression.

(Probably not that positive, since Lazuli rarely had a facial expression)

Lazuli was the person responsible for supervising Eugene's training, physically, mentally and spiritually. Apparently, all of that was necessary for the magical people that inhabited that world to consider him a Pontum. Couldn't they be happy with a teenager risking his life? No, they wanted him to go through a boring hell known as school. Of course, it was a special school, but was it really that different? If Eugene had to be inside of a room while having classes, he decided that no, it wasn't.

Back to what we were talking about, Eugene did not know that much about Lazuli. They were the rarest kind of Dracae, they seemed to not feel any kind of emotion and had the bad habit of drip sarcasm whenever they met the Raziel brothers, which led them to a passive-aggressive that was as interesting as it was stressing. There was also that annoying habit of overestimating Eugene's abilities whenever they were in front of others as if it was a competition over who had the most powerful Pontum.

Eugene felt like a woman, being objectified like that.

"Today I'll take you to the armoury." They said, awaking Eugene from his thoughts.

"Bless you." He said, frowning. "Is that some kind of lost city, food or...?"

"Arsenal." They said, turning to the door. During the to months of training, Lazuli had got used to translate their exotic terms for Eugene, who had no kind of linguistic knowledge. He was just a painter, Dallon was the poet.

His heart ached as he remembered that name, that insisted in coming to his mind together with blue eyes and dark hair, with the rare smile that seemed to be able to end all of the world's wars. Eugene ran a hand through his blond hair, letting out a sigh, not even noticing the daises as he left the greenhouse, closing the door behind him.

He knew Dallon Jean Miguel Souto when he was nine, on the school's playground. It wasn't a very gracious moment for Eugene, who was bawling his eyes out because of a bruised knee. The other calmed him down and took him to the nurse's office. Eugene had always been an anxious child, and if Dallon hadn't taken him there, he would never have had the courage to do so.

The two became friends quickly. Dallon was a year older than Eugene, and they didn't share classes, but they always met each other during recess and played together. Dallon seemed to like pretending that he was an astronaut, and Eugene soon got used to playing the role of the alien. Well, aliens were cool, anyway.

Dallon was Eugene's first and best friend, and finding out their friendship grew because of an obligation of Dallon was absurd, and broke his heart. So many moments shared together now seemed implanted memories by a cruel magical society.

He followed Lazuli through the Pontum Sanctum's hallways without really paying attention to where he was. That place was huge, and if the two ended up in a door Eugene didn't recognize - Eugene, who kind of lived there now, considering how much time he spent there - he wouldn't be surprised.

He wasn't that excited to explore the place, not ever since he learned to do portals. He used to spend his time in the greenhouse, taking care of the plants or reading books Lazuli gave him, occupying moments that would be haunted by obscure thoughts if his imagination had too much freedom. As they say, an empty mind is devil's workshop.

Eugene sighed once again, something he did a lot, lately. He stared at the Dracae's back, covered by indigo fabric, adorned by golden details. The fashion there was certainly different from the human's, but it was interesting in its own way. Eugene noticed each one of the main five people that lived there had their own style. He didn't really know much about, you know, normal Dracae, civilians, but their style seemed... uh, ninja style.

The Dracae he knew weren't normal, by any means. They were killing machines that would give him nightmares if they weren't in the same team., Godric, his history and politics teacher was a skilled militarian trained to kill silently. Narcissa, the one responsible for his medical training, was the type of person to heal you and take care of your wounds just so that she could beat you up again. Dante was a mysterious guy, with biceps the size of Eugene's head, and if that wasn't' scary... Eugene did not know what "scary" was.

"Why are we going to the Arm... The arsenal?" He asked. "Are you going to give me a weapon?"

"People don't get weapons, Eugene, they deserve them."

"Ok... Do I deserve one?" He inquired. The Dracae stopped abruptly, causing Eugene to hit their back. He wondered if it hadn't been something he said, but Laz's hoarse voice calmed him.

"We'll find out later." They said, putting their hands in a steel door that seemed to not have a keyhole or a handle. Quite annoying, if you ask Eugene.

A blue light shone from Lazuli's fingertips, spreading through the metal just like heat. Magic was a weird sensation, to Eugene. Maybe it was for the fact that he literally learned some tricks a couple of weeks before, after a conversation in another plane of existence with his deceased grandpa. She knew her stuff.

It was a hot sensation, for Eugene. Heat running through his veins. When he used magic, he seemed to feel every and each cell of his body, which was quite uncomfortable. He was getting used to it, little by little.

"The armoury is a shared space. Other Representants or Pontum may be here." Lazuli said. Whenever there was a chance he could end up meeting Dallon, the Dracae made sure he would know it. He was grateful, but he also worried every time the Dracae said so, and wouldn't be able to concentrate on whatever they were doing.

The arsenal was huge. Different types of weapons hanged from the walls, from the ground to the ceiling, that seemed exaggeratedly far away. How did they take the weapons from the top? Maybe there were faeries there, that flew high up to bring them axes and lances? Weren't dwarves who made weapons? Maybe they kept them in the arsenal, too?

The place seemed to organize its weapons by type. There were different kinds of axes, with various sizes and weights grouped together; there were lances, bows and arrows, scythes, swords, rapiers, hammers, whips and etc.

So many questions popped up in Eugene's mind, he didn't notice that Lazuli had already abandoned him and was flipping through the yellowed pages of a gigantic book.

"You shouldn't stand in the middle of the way, noob." A feminine voice said.

Surprised, he turned quickly to see who was behind him, but he lost his balance easily.

His body didn't hit the ground, though. A firm hand held him from his green shirt.

Two people stared at him, one of them still holding him. Eugene knew them from a reunion a couple of weeks before. Leilani, the Mage Pontum and Aeris, the Kitsune Pontum.

Leilani let him go, smiling at him. She was the youngest of all the Pontum, being just fifteen, but she had more muscles than Eugene, who was seventeen. He scratched the back of his head, smiling shyly to her, who laughed.

"Are you always like that, noob?" She asked. "You don't need to get all shy, we don't bite!"

Aeris laughed too. "How are you, Eugene?" She asked.

"I'm fine!" He said, a little too loud, trying to look anywhere but them. "Uh... Why are you here? Not that you shouldn't be, you are Pontum, after all. It's normal for you to be in places like this, uh..."

Aeris put her hands on his shoulders, smiling gently. "Breathe, Eugene." She said, trying to calm him down. He did as he was told, as Leilani answered his question:

"We came here to train." She said. "It is hard for us to go against each other, because of time zones and shit."

"Yes," Aeris said "honestly, I was getting tired of training against Dallon. You know how it is, right, Leilani?"

"Oh, yeah!" The younger one laughed, and Eugene just couldn't face them. "Always the same tricks and attacks."

"I think he just lets us win. Have you seen him fighting for real?" Aeris laughed.

Leilani nodded. "It sucks." She said, turning to Eugene. "Do you fight with him for real or he also things you are too fragile to face his manly strength?"

"We don't fight." He said, shrinking. "Actually, the last time I saw him was in that reunion, a couple of weeks ago."

Leilani and Aeris frowned. "Well, but... didn't you go to the same school?" Leilani asked.

Eugene shook his head. "He went back to Colombia." He said, avoiding Leilani's questioning dark eyes. "We don't talk anymore. He doesn't want to have anything to do with me."

Aeris opened her mouth, but Lazuli's distant voice interrupted their conversation.

"Eugene, come here." They said, and Eugene complied.

"What are you doing?" He asked.

"Trying to find some kind of weapon you can train with." They said, crossing their arms. The two girls approached them, curiously.

"Eugene looks like a swordsman" Leilani said. "What about a rapier?"

"Eugene is not confident enough to be a swordsman." Lazuli said. "Besides, he doesn't have the strength."

"I'm not even here." He mumbled.

"An arrow, then?" Aeris suggested. "It's good for building strength."

Lazuli flipped through the pages.

"It is possible. He needs to be useful, somehow."

Eugene frowned, trying to ignore that last part. It seemed that Lazuli had no sense of how to talk to people. He sighed.

"What kind of arms do you have?" He turned to the two girls.

Leilani grinned, her eyes glimmering. "I have an axe." She said. "Do ya wanna see it?"

Eugene nodded with enthusiasm. Leilani got up on some kind of arena in the middle of the arsenal, raising her hands up.

Her eyes were filled by a white light, the same that flickered around her fingers as if they were electricity waves. It didn't take long for a huge battle axe to occupy one of her hands, at the same time a loud bang filled the room, just like thunder.

Leilani smiled wide, and Eugene felt the urge to ask: "Does that happen every time you, like.... summon your weapon?"

"Let's just say Leilani likes drama." Aeris laughed.

"Can I see yours too?" Eugene turned to her, and the woman nodded. She went to where Leilani stood and closed her eyes in concentration. With a quick flick of her wrists, two whips appeared in her hands.

"They turn into swords." She mentioned. True to her word, with another flick the whips got hard and stood in a straight form, turning into two blades.

"Can I get a cool weapon like that?" Eugene turned to Lazuli, who merely sighed:

"Those are short-range weapons. Maybe one day."

The smile vanished from Eugene's face, who felt like a kid who just asked something absurd to their parents.

"Even when you get the weapon you want, Eugene, don't give up on the bow and arrow. Archers are super cool and it can save many lives. Ok?"

"Ok." He nodded, a bit disappointed but definitely hopeful with the promise.

Eugene felt pain in muscles he barely knew that existed. The boy practically dragged himself back to the greenhouse, his legs numb and screaming from the agony simultaneously, a distasteful paradox Eugene wanted to ignore, but couldn't.

He threw himself in the only chair available, resting his head on the table full of books in front of him, his sweaty back pressed against the wood of the seat.

Leilani and Aeris did not stay for long. They said it was better to leave Laz and Eugene alone, so they could work out and train shooting with the bow and arrow.

The Dracae was not, in any way, gentle with him. Laz first taught him how to stand up - something he never knew he did wrong -, the correct posture and how to shoot an arrow - all of that without a proper bow.

In the end, they gave him a green and metallic bow so he could practice and build up strength before actually getting his weapon.

The bow was indeed pretty, with blue runes colouring the green metal. Still, Eugene thought that was the last exciting weapon ever.

"Really? I don't really like rapiers, I think they're the worst." Lazuli had said.

He raised his head, taking a look at the daisies near the door. He thought that being part of a magical society was stressing enough, but apparently, he still had to deal with his uncle's mystery on top of it all.

He massaged his temples, feeling the anxiety looming in his mind. He had no psychological strength to deal with it all.

His cellphone vibrated on the table, calling for his attention. The notification that lit up the screen told him he had been added to a new group.

Pontum Chat, that was the name. He was greeted by numerous messages of Leilani and Aeris as he opened the app.

He smiled to himself. Those two were good people. He was worried the other Pontum would be cold, perhaps hostile, but he had been lucky.

There were other Pontum besides Leilani and Aeris. There was Tristan, a mysterious and quiet guy, who prefered to avoid attention to himself. Eugene understood the feeling. Tristan was the Werewolves' Pontum, and every time Eugene saw him, he was accompanied by the race's Representant, Nikolai Volkov.

Eugene had never talked to the man, but he felt like he knew him a little. Lazuli did not hold anything back when talking about their coworkers. The Dracae had said that everyone was a close, good friend of theirs. But not Arkiel. Arkiel could choke.

Arkiel was the unsympathetic Representant of the Ghouls, creatures that fed themselves with dead magical meat. That being said, they're not the most beloved guys around, but they have a stable government and a good source of food, so no one bothers with them.

A new message arrived. Tristan welcomed him, which brought a smile to Eugene's lips. At least he wouldn't have any trouble with his colleagues. Honestly, he wasn't mature enough to deal with intrapersonal problems on top of the new job and the death of his uncle Henry. The enigma of the letter was eating at him.

He sighed, rubbing his face. It was getting late and he needed to go back home.

He quickly got up and walked to the door with large steps, getting the letter from below the daisies rapidly and hiding it into his pants.

Even far from him, Dallon could still cause him headaches. If he could, Eugene would go back in time and refuse the fucking message, would tell his friend to go fuck off and ignore him for the rest of his life.

Goddamn it.

#writebrl#writers#writing#original#original story#my writing#my story#oc#ocs#oc shit#bridges to pax#eugene foster#lazuli bellator#aeris brennan#leilani kekoa#dallon souto#tristan kabir#pontum

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

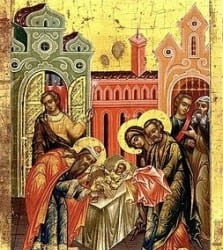

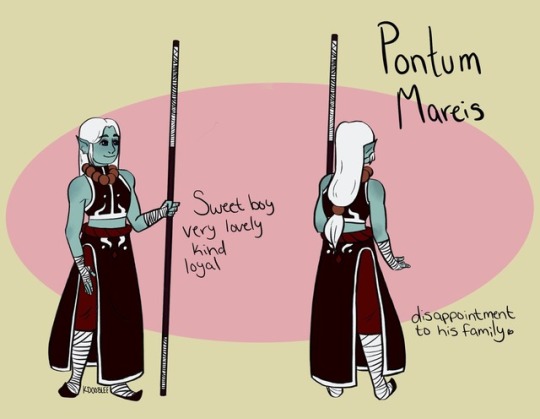

My new monk boi for d&d

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

anticum repetent iterum chaos omnia; mixtis

sidera sideribus concurrent: ignea pontum

astra petent: tellus extendere litora nolet,

excutietque fretum: fratri contraria Phoebe

ibit, et, oblicum bigas agitare per orbem

indignata, diem poscet sibi: totaque discors

machina divulsi turbabit foedera mundi.

To the ancient chaos all things will once again return.

Constellations on constellations will collide. The stars aflame

will fall upon the sea. The earth will refuse to only extend to her shores,

and will drive out the waves. Against her own brother,

The moon will go, resenting that she drives her pair on a covert circuit,

and she will demand the day for herself. And the whole

discordant machine will turn turbid the covenants of a world torn asunder.

~ Lucan, Pharsalia (Book 1.74-80)

#latin#latin language#latin translation#classical translation#poetry translation#translation#classical poetry#classical literature#classical mythology#lucan#pharsalia#latin quotes#book quotes#my own work#dys blurbs#for practice: I haven't worked with latin for a hot minute

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Laocoon (Aeneid 2.199-222)

Now, another terrifying thing happened to the Trojans,

this more severe and more wretched, and troubled our hearts.

Laocoon, chosen as priest of Neptune by lot,

was sacrificing a huge bull at the solemn altar.

But then – and I shudder to speak of it – two serpents

with vast coils were approaching over the peaceful depths of the sea;

they had come from Tenedos and were aiming for our shore.

They raised their erect chests and bloody crests between the waves,

their bodies skimmed the sea behind,

their backs were bent in huge coils.

Foaming, the sea crashed aloud – and now they were approaching our fields,

burning, their eyes were shot with blood and fire,

hissing, they moistened their mouths with rippling tongues -

We scattered at the sight, pale with fear. They made for Laocoon

in a determined battle line, and the first snake,

enveloping the small bodies of his two sons in an

embrace, devoured their wretched limbs with his fangs -

then they seized Laocoon himself as he came to help bringing weapons,

and they tied him up in their vast coils.

Twice they wound around his middle,

twice they wrapped their scaly bodies around his neck

while he tried to break the coils with his bare hands.

Drenched in blood, his ribbons black with poison,

he raised dreadful screams to the stars.

Hic aliud maius miseris multoque tremendum

obicitur magis atque improvida pectora turbat. 200

Laocoon, ductus Neptuno sorte sacerdos,

sollemnis taurum ingentem mactabat ad aras.

ecce autem gemini a Tenedo tranquilla per alta

(horresco referens) immensis orbibus angues

incumbunt pelago pariterque ad litora tendunt; 205

pectora quorum inter fluctus arrecta iubaeque

sanguineae superant undas, pars cetera pontum

pone legit sinuatque immensa volumine terga.

fit sonitus spumante salo; iamque arva tenebant

ardentisque oculos suffecti sanguine et igni 210

sibila lambebant linguis vibrantibus ora.

diffugimus visu exsangues. illi agmine certo

Laocoonta petunt; et primum parva duorum

corpora natorum serpens amplexus uterque

implicat et miseros morsu depascitur artus; 215

post ipsum auxilio subeuntem ac tela ferentem

corripiunt spirisque ligant ingentibus; et iam

bis medium amplexi, bis collo squamea circum

terga dati superant capite et cervicibus altis.

ille simul manibus tendit divellere nodos 220

perfusus sanie vittas atroque veneno,

clamores simul horrendos ad sidera tollit:

#virgil#aeneid#laocoon#latin#latin translation#translation#epic poetry#roman poetry#roman epic#ancient rome#augustus#emperor augustus#tagamemnon#dark academia#classics#poetry

51 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Even as are the generations of leaves, such are those also of men. As for the leaves, the wind scattereth some upon the earth, but the forest, as it bourgeons, putteth forth others when the season of spring is come; even so of men one generation springeth up and another passeth away.

❧

Nor is the mode of grafting and of budding the same. For where the buds push out from amid the bark, and burst their tender sheaths, a narrow slit is made just in the knot; in this from an alien tree they insert a bud, and teach it to grow into the sappy bark. Or, again, knotless boles are cut open, and with wedges a path is cleft deep into the core; then fruitful slips are let in, and in a little while, lo! a mighty tree shoots up skyward with joyous boughs, and marvels at its strange leafage and fruits not its own.

❧

From here a road leads to the waters of Tartarean Acheron. Here, thick with mire and of fathomless flood, a whirlpool seethes and belches into Cocytus all its sand. A grim ferryman guards these waters and streams, terrible in his squalor—Charon, on whose chin lies a mass of unkempt, hoary hair; his eyes are staring orbs of flame; his squalid garb hangs by a knot from his shoulders. Unaided, he poles the boat, tends the sails, and in his murky craft convoys the dead—now aged, but a god’s old age is hardy and green. Hither rushed all the throng, streaming to the banks; mothers and men and bodies of high-souled heroes, their life now done, boys and unwedded girls, and sons placed on the pyre before their fathers’ eyes; thick as the leaves of the forest that at autumn’s first frost drop and fall, and thick as the birds that from the seething deep flock shoreward, when the chill of the year drives them overseas and sends them into sunny lands. They stood, pleading to be the first ferried across, and stretched out hands in yearning for the farther shore. But the surly boatman takes now these, now those, while others he thrusts away, back from the brink.

❧

It has always been accepted, and always will be, that words stamped with the mint-mark of the day should be brought into currency. As the woods change their foliage with the decline of each year, and the earliest leaves fall, so words die out with old age; and the newly born ones thrive and prosper just like human beings in the vigour of youth. We are all destined to die, we and all our works. Perhaps the land has been dug out and an arm of the sea let in, to give protection to our fleets from the northern gales (and what a royal undertaking this was!); or a marsh, long a barren waste on which oars were plied, has been put under the plough and produces food for the neighbouring towns; or a river has been made to change a course ruinous to the cornfields and turned into a straighter channel: whatever they are, the works of men will pass away. How much less likely are the glory and grace of language to have an enduring life! Many terms that have now dropped out of use will be revived, if usage so requires, and others which are now in repute will die out; for it is usage which regulates the laws and conventions of speech.

❧

But those souls, naked and desolate,

lost their color. With chattering teeth

they heard his brutal words.

They blasphemed God, their parents,

the human race, the place, the time, the seed

of their begetting and their birth.

Then, weeping bitterly, they drew together

to the accursèd shore that waits

for everyone who fears not God.

Charon the demon, with eyes of glowing coals,

beckons to them, herds them all aboard,

striking anyone who slackens with his oar.

Just as in autumn the leaves fall away,

one, and then another, until the bough

sees all its spoil upon the ground,

so the wicked seed of Adam fling themselves

one by one from shore, at his signal,

as does a falcon at its summons.

Thus they depart over dark water,

and before they have landed on the other side

another crowd has gathered on this shore.

❧

Before I descended to anguish of Hell,

I was the name on earth of the Sovereign Good,

whose joyous rays envelop and surround me.

Later El became His name, and that is as it should be,

for mortal custom is like a leaf upon a branch,

which goes and then another comes.

Homer, from Book VI in The Iliad, trans. A. T. Murray.

Vergil, from Book II in Georgics, trans. H. R. Fairclough and G. P. Goold, lines 80-2:

Vergil, from Book VI in The Aeneid, trans. H. R. Fairclough and G. P. Goold, lines 309-12.

Horace, from ‘On the Art of Poetry’ in Classical Literary Criticism, trans. T. S. Dorsch, line 60.

Dante, from Canto III in Inferno, trans. Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander, lines 100-120.

Dante, from Canto XXVI in Paradiso, trans. Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander, lines 133-38.

❧

Vergil, ‘Georgics II’: nec longum tempus, et ingens/ exiit ad caelum ramis felicibus arbos,/ miratastque nouas frondes et non sua poma

Vergil, ‘Aeneid VI’: quam multa in siluis autumni frigore primo/ lapsa cadunt folia, aut ad terram gurgite ab alto/ quam multae glomerantur aues, ubi frigidus annus/ trans pontum fugat et terris immittit apricis.

Horace, ‘Ars Poetica’: ut silvae foliis pronos mutantur in annos,/ prima cadunt; ita verborum vetus interit aetas,/ et iuvenum ritu florent modo nata vigentque.

Dante, ‘Inferno III’: Come d’autunno si levan *le foglie/ l’una appresso de l’altra, fin che ’l ramo/ vede a la terra tutte le sue spoglie,// similemente il mal seme d’Adamo/ gittansi di quel lito ad una ad una,/ per cenni come augel per suo richiamo.

Dante, ‘Paradiso XXVI’: e ciò convene,/ ché l’uso d’i mortali è come *fronda/ in ramo, che sen va e altra vene

❧

Homer, from Book XXI in The Iliad, trans. Robert Fitzgerald: “Ephemeral as the flamelike budding leaves,/ men flourish on the ripe wheat of the grainland,/ then in spiritless age they waste and die.”

Leopardi, ‘Pensieri XXXIX’: “In The Book of the Courtier, Balthazar Castiglione very aptly explains why old people usually disparage the present while praising the time when they were young: “Thus in my opinion, the cause of this mistaken notion among old people is that the fleeing years steal from them most human comforts; they leaven the blood of most its vital spirits, whereby the constitution is altered and the organs by which the soul exercises its powers frow weak. Hence in our old age the gentle flowers of happiness fall from our hearts as leaves from trees in autumn; and in the place of serence and lucid thoughts there comes but gloomy and cloudy sadness, attended by a thousant ills. So it is that not only the body, but also the mind, grows ever more infirm. Of past pleasures we retain only a lingering memory and the image of that fond time of tender youth in which, even as we look back upon that place once again, heaven and earth and all its creatures seem to be endlessly celebrating, and the sweet springtime of happiness seems to bloom in out thoughts as in a lush and delicte garden. So that when the sun of life enters its wintry season and with its westward descent deprives us of such pleasures, it may perhaps be useful to lose our remembrance of them as well and discover—as Themistocles said—an art that would teach us to forget. For our body’s senses are so misleading that they are often wont to beguile the mind’s judgement as well. Thus is seems to me that the plight of the aged is similar to that of those who, when departing from the harbor, fix their gaze upon the shore and think that their ship does not move, but that it is the shore that is departing. And yet quite the contrary is true: the harbor, and likewise time and its pleasures, remain fixed while we, one after another, flee on the ship of our mortality, voyaging across that stormy sea that devours and consumes all things. Not shall we ever be allowed to touch land again; rather, our ship, beaten about by opposing winds, shall in the end scuttle us upon some reef. Since a senile and weathered spirit is unsuited or unfit for most pleasures, it obviously cannot enjoy them. And just as to victims of fever whose palates are spoiled by corrupt vapors all wines, however delicate and precious they may be, seem terribly bitter, so to old people, indisposed as they are, pleasures seem cold and insipid, though desire for pleasure still exists. And although the pleasures themselves remain the same, they yet seem quite different from those that old people remember having once enjoyed. Feeling thus deprived of such pleasures, they sink into regret and denounce the present as evil, since they are unable to perceive that the cahnge lies within themselves, not in time. Instead, they call to mind the delights of the past and the times when such pleasures were to be had and they therefore prais the past as good since it seems to convey a fragrance of the delights they once felt when it was present. Since, after all, our souls feel hatred for all things that have companioned our sorrows, and love for the companion of our delights.“ [Castiglione, Book II.1]”

Isaiah 7:2: “And it was told the house of David, saying, Syria is confederate with Ephraim. And his heart was moved, and the heart of his people, as the trees of the wood are moved with the wind.” (KJV)

Vergil, Aeneid 6.282: “In the midst an elm, shadowy and vast, spreads her boughs and aged arms, the home which, men say, false Dreams hold, clinging under every leaf. And many monstrous forms besides of various beasts are stalled at the doors, Centaurs and double-shaped Scyllas, and the hundredfold Briareus, and the beast of Lerna, hissing horribly, and the Chimaera armed with flame, Gorgons and Harpies, and the shape of the three-bodied shade. Here on a sudden, in trembling terror, Aeneas grasps his sword, and turns the naked edge against their coming; and did not his wise companion warn him that these were but faint, bodiless lives, flitting under a hollow semblance of form, he would rush upon them and vainly cleave shadows with steel.”

John Milton, from Book I, lines 299-313:

“Nathless he so endur'd, till on the Beach

Of that inflamed Sea, he stood and call'd

His Legions, Angel Forms, who lay intrans't

Thick as Autumnal Leaves that strow the Brooks

In Vallombrosa, where th' Etrurian shades

High overarch't imbowr; or scatterd sedge

Afloat, when with fierce Winds Orion arm'd

Hath vext the Red-Sea Coast, whose waves orethrew

Busiris and his Memphian Chivalry,

While with perfidious hatred they pursu'd

The Sojourners of Goshen, who beheld

From the safe shore thir floating Carkases

And broken Chariot Wheels, so thick bestrown

Abject and lost lay these, covering the Flood,

Under amazement of thir hideous change.“

#homer#horace#ars poetica#the art of poetry#dante#iliad#vergil#aeneid#georgics#leopardi#castiglione#isaiah#milton#john milton#paradise lost

1 note

·

View note

Text

fert animus causas tantarum expromere rerum,

inmensumque aperitur opus, quid in arma furentem

inpulerit populum, quid pacem excusserit orbi.

inuida fatorum series summisque negatum

stare diu nimioque graues sub pondere lapsus

nec se Roma ferens. sic, cum conpage soluta

saecula tot mundi suprema coegerit hora

antiquum repetens iterum chaos, [omnia mixtis

sidera sideribus concurrent,] ignea pontum

astra petent, tellus extendere litora nolet

excutietque fretum, fratri contraria Phoebe

ibit et obliquum bigas agitare per orbem

indignata diem poscet sibi, totaque discors

machina diuolsi turbabit foedera mundi.

in se magna ruunt: laetis hunc numina rebus

crescendi posuere modum.

My spirit brings me to tell the causes of such things,

And to disclose the great work, which compelled a maddened people

To war, and drove out peace from our world.

The hateful dictates of fate long stood

Beneath a slipping and solemn weight: and, well

Rome couldn’t bear its own bulk.

Naturally, when such frameworks were dissolved

And the century’s last hour dawned

Ancient chaos returned to take its due.

All the heavens ran together, and burning

Stars sought the earth, which itself refused

To extend to its own borders. Land shook off sea, and

Phoebe, opposite her brother no longer,

Drove her two-horsed chariot through the slanting sphere

And arrogantly demanded the day for herself.

In short: the CHAOSMACHINE entire tore up the treaties of the gutted world.

See, here’s the thing: Greatness falls upon its own sword, and the gods reserve

The secrets of growth for joyful things. Not for us.

— Lucan, Pharsalia I.67-82 (translation mine)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beta Reader Wanted for LGBTQ YA Novel

Hi! I'm currently translating one my stories from portuguese to english. Because english is not my first language, I'm having a bit of trouble to evaluate if my writing is good enough.

Name: Alec

Book Title:

Genre: Fantasy

Age Group: YA

Word Count: the story is still in progress. In portuguese there are 30.000 words and I'm still translating the first chapter to english

Warning: Violence, anxiety/depression, swearing

Type of beta I'm looking for: Someone who can check my grammar mistakes, point out plot holes/inconsistencies, and things like that.

Time restraints: None, I don't really care how much time it takes, I just need help

Preferred form of contact: DM me or email me

Main account: https://www.tumblr.com/blog/astraethewitch

Writeblr account: https://www.tumblr.com/blog/astraeusthewriter

Brief summary: Eugene Foster liked to think he was a regular teenager despite his schizophrenia, but once he finds out that his mental illness actually doesn't exist and the strange creatures he's been seeing his whole life are actually real, he can't call himself a normal teen, anymore. He now has to act as the bridge - a Pontum, as they call it - between the human and the magical world while trying to find out who murdered his uncle, Henry Foster, the Pontum before him. With a letter written by a dead man and doubt in his heart, will Eugene truly be able to find out the dirty secrets the magical Counsil has been burying for years?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Monday, August 8, 2023

aout 8_july 25

The feast of the dormiton of St Anna mother of the Holy Theotokos

Saint Anna was the daughter of the priest Matthan and his wife Mary. She was of the tribe of Levi and the lineage of Aaron. According to Tradition, she died peacefully in Jerusalem at age 79, before the Annunciation to the Most Holy Theotokos.

During the reign of Saint Justinian the Emperor (527-565), a church was built in her honor at Deutera. Emperor Justinian II (685-695; 705-711) restored her church, since Saint Anna had appeared to his pregnant wife. It was at this time that her body and maphorion (veil) were transferred to Constantinople.

Portions of Saint Anna’s holy relics may be found on Mount Athos: Stavronikita Monastery (part of her left hand), Saint Anna’s Skete (part of her incorrupt left foot), Koutloumousiou Monastery (part of her incorrupt right foot). Fragments of her relics may also be found in her Monastery at Lygaria, Lamia, and in the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian at Sourota. Part of the saint’s incorrupt flesh is in the collection of Saints’ relics of the International Catholic Crusaders. The church of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome has one of the saint’s wrists.

Saint Anna is also commemorated on September 9.

SAINT OLYMPIADA THE DEACONESS OF CONSTANTINIOPLE (425)

Saint Olympias the Deaconess was the daughter of the senator Anicius Secundus, and by her mother, she was the granddaughter of the noted eparch Eulalios (he is mentioned in the life of Saint Nicholas). Before her marriage to Anicius Secundus, Olympias’s mother had been married to the Armenian emperor Arsak and became widowed. When Saint Olympias was still very young, her parents betrothed her to a nobleman. The marriage was supposed to take place when Saint Olympias reached the age of maturity. However, The bridegroom soon died, and Saint Olympias did not wish to enter another marriage, preferring a life of virginity.

After the death of her parents she became the heir to great wealth, which she began to distribute to all the needy: the poor, the orphaned and the widowed. She also gave generously to the churches, monasteries, hospices and shelters for the downtrodden and the homeless.

Holy Patriarch Nectarius (381-397) appointed Saint Olympias as a deaconess. The saint fulfilled her service honorably and without reproach.

Saint Olympias provided great assistance to hierarchs coming to Constantinople: Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium, Onesimus of Pontum, Gregory the Theologian, Saint Basil the Great’s brother Peter of Sebaste, Epiphanius of Cyprus, and she attended to them all with great love. She did not regard her wealth as her own but rather God’s, and she distributed not only to good people, but also to their enemies.

Saint John Chrysostom (November 13) had high regard for Saint Olympias, and he showed her good will and spiritual love. When this holy hierarch was unjustly banished, Saint Olympias and the other deaconesses were deeply upset. Leaving the church for the last time, Saint John Chrysostom called out to Saint Olympias and the other deaconesses Pentadia, Proklia and Salbina. He said that the matters incited against him would come to an end, but scarcely more would they see him. He asked them not to abandon the Church, but to continue serving it under his successor. The holy women, shedding tears, fell down before the saint.

Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria (385-412), had repeatedly benefited from the generosity of Saint Olympias, but turned against her for her devotion to Saint John Chrysostom. She had also taken in and fed monks, arriving in Constantinople, whom Patriarch Theophilus had banished from the Egyptian desert. He levelled unrighteous accusations against her and attempted to cast doubt on her holy life.

After the banishment of Saint John Chrysostom, someone set fire to a large church, and after this a large part of the city burned down.

All the supporters of Saint John Chrysostom came under suspicion of arson, and they were summoned for interrogation. They summoned Saint Olympias to trial, rigorously interrogating her. They fined her a large sum of money for the crime of arson, despite her innocence and a lack of evidence against her. After this the saint left Constantinople and set out to Kyzikos (on the Sea of Marmara). But her enemies did not cease their persecution. In the year 405 they sentenced her to prison at Nicomedia, where the saint underwent much grief and deprivation. Saint John Chrysostom wrote to her from his exile, consoling her in her sorrow. In the year 409 Saint Olympias entered into eternal rest.

Saint Olympias appeared in a dream to the Bishop of Nicomedia and commanded that her body be placed in a wooden coffin and cast into the sea. “Wherever the waves carry the coffin, there let my body be buried,” said the saint. The coffin was brought by the waves to a place named Brokthoi near Constantinople. The inhabitants, informed of this by God, took the holy relics of Saint Olympias and placed them in the church of the holy Apostle Thomas.

Afterwards, during an invasion of enemies, the church was burned, but the relics were preserved. Under the Patriarch Sergius (610-638), they were transferred to Constantinople and put in the women’s monastery founded by Saint Olympias. Miracles and healings occurred from her relics.

Source, all texts: Orthodox Church in America_ OCA

1 CORINTHIANS 15:12-19

12 Now if Christ is preached that He has been raised from the dead, how do some among you say that there is no resurrection of the dead? 13 But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ is not risen. 14 And if Christ is not risen, then our preaching is empty and your faith is also empty. 15 Yes, and we are found false witnesses of God, because we have testified of God that He raised up Christ, whom He did not raise up-if in fact the dead do not rise. 16 For if the dead do not rise, then Christ is not risen. 17 And if Christ is not risen, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins! 18 Then also those who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. 19 If in this life only we have hope in Christ, we are of all men the most pitiable.

MATTHEW 21:18-22

18 Now in the morning, as He returned to the city, He was hungry. 19 And seeing a fig tree by the road, He came to it and found nothing on it but leaves, and said to it, "Let no fruit grow on you ever again." Immediately the fig tree withered away. 20 And when the disciples saw it, they marveled, saying, "How did the fig tree wither away so soon?" 21 So Jesus answered and said to them, "Assuredly, I say to you, if you have faith and do not doubt, you will not only do what was done to the fig tree, but also if you say to this mountain, 'Be removed and be cast into the sea,' it will be done. 22 And whatever things you ask in prayer, believing, you will receive.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#gospel#bible#saints

1 note

·

View note

Text

ante diem vii Idus Decembres MMXXI A.D.

Agricola agram et casam habet. Vir liber non ferret. Bonas iuvamus non malas. Libros magnos habeo. Magna cum cura laboro.

Filii ad silvam festinant. Nautae cum amicis navigare solent.

Meus liber non magnus est. Esne bonus? Agricola magnam sapientam habet. Nemo virorum saxum iactare audet. Amice, animum habes! Pueri puellaque parvi sunt!

Multi in nostra terra multa non habent. Pontus magnus aqua vias silvasque implet. Bonus tacet sed malus saepe calmat. Facta bonorum virorum sunt bona. Dominus viros puerosque ad bellum vocare parat. Sunt in meis agris boni agricolae. Aegrae pro templo sedere solent. Femina multos amicos nautae iuvat. Iactasne post casam tuas rosas? Pontus est altus.

Sunt multi di ventorum. In silva errare non dubito. Nemo malum exemplum dare optat. Ad divinum templum deorum festinat. Regnum viri trans pontum iacet. Puellae pulchra dona tandem dat. Magna cum cura consilium parant. Viri cum filiis in agro saepe laborat. Rosa pulchra est. Puellae, vocate agricolas ex agris.

Mundus caeli vastus tacet et Neptunus saevus undis asperis pausam dat.

Primus et Romae et imperii conditor Romulus est, filius dei, Martis, et Rhea Silviae. Romulum cum Remo fratre in Tiberinum rex, Amulius iactat, sed infantes clamant et lupa pueros iuvat. tum sub arbore Faustulus pastor parvos pueros videt et portat infantes in casam et pueros educat.

Nemo ad altum ambulat locum si timet. Si virum multi timent, multos timere debet. Nec vita nec fortuna propia est viris. Fortuna caeca est. Cogito cum meo animo. Hic dea silvarum solet nare.

0 notes

Photo

Nuovo post su https://is.gd/biZyF6

Nardò: Alberico Longo e la sua inedita (doppiamente ...) versione di un mito

di Armando Polito

Sul neretino Alberico rinvio per una nota leggera a http://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2015/02/11/una-nota-su-alberico-longo-di-nardo/ e http://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2019/10/06/nardo-alberico-longo-e-ursula/. Sulla sua morte violenta segnalo http://bitesonline.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Bites_003_Catelvetro.pdf e quanto si legge in Biblioteca modenese, a cura di Girolamo Tiraboschi, Società tipografica, Modena, 1781, v. I, pp. 443-447 (https://books.google.it/books?id=ZC1fAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA446&dq=alberico+longo+pubblicati&hl=it&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwivnZO9xonlAhUB2qQKHRTLA7sQ6AEIYTAJ#v=onepage&q=alberico%20longo%20pubblicati&f=false). Sui sentimenti che essa suscitò in chi lo stimava rinvio ad una lettera di Annibal Caro del 13 luglio 1555 indirizzata da Roma a Vincenzo Fontana (in Lettere scelte di Annibal Varo, Barbera, Firenze, 1869, pp. 90-91: https://books.google.it/books?id=LDg-AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA90&dq=alberico+longo&hl=it&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjinrPp_YflAhVPPFAKHUtLDFgQ6AEIOzAD#v=onepage&q=alberico%20longo&f=false.