#nan shepherd

Text

"The mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him."

— Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photo : 站在武嶺往西南可眺台14甲線橫亙合歡山腹 by Chu Lan

Wuling 武嶺,舊名/日語:佐久間峠 Sakuma tōge or 南嶺,為台灣中央山脈北段高峰合歡東峰、合歡主峰間嶺線的鞍部,海拔3,275公尺,是台灣公路最高點,位於台14甲線31.5公里處,在太魯閣國家公園西境,為合歡山森林遊樂區一處景點,行政區劃屬南投縣仁愛鄉大同村。

在武嶺建有一座觀景台,供遊客眺望遠近風景。由於地處偏僻,少有光害,也是夜間觀星的良好地點。

formerly known as Sakuma Pass (佐久間峠, Sakuma-tōge), It's a mountain pass located in Ren'ai, Nantou, Taiwan, transversing the Central Mountain Range near the peak of Hehuanshan within Taroko National Park. It is the highest paved road in elevation in Taiwan.

Many races are held to ride to Wuling, most notably the Taiwan KOM Challenge, a non-UCI sanctioned race beginning in Qixingtan Beach and takes the eastern route. The 107 km race is regarded as an intense climb within the cycling community, with Grand Tour winner Vincenzo Nibali commenting: "I've never ridden such a long and hard climb before in my entire life." Wuling is also a popular stargazing and bird-watching location. Common birds include the Taiwan rosefinch, white-whiskered laughingthrush, and collared bush robin.

and

2023 Taiwan KOM Challenge Race Teaser video 臺灣自行車登山王挑戰

youtube

當我沒有目的地,當我並沒有要抵達任何特定的地方,而只為了與山同行而出發時,山就完全地展現了他自己,就像一個人拜訪一位朋友,除了與他在一起之外,沒有其他任何意圖。

The mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.

— Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain. 💕

#chu lan#朱蘭皮藝#fine craft artist#leather art artist#beautiful life#wuling 武嶺#taiwan 台灣#nan shepherd#the living mountain#travel in 2023#my memories

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

So simply to look on anything, such as a mountain, with the love that penetrates to its essence, is to widen the domain of being in the vastness of non-being. Man has no other reason for his existence.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

#book quotes#nan shepherd#the living mountain#literature#books and libraries#nature writing#hiking#mountains#books and reading#walking in nature

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

A book is good if the first pages make tears well up in the corners of your eyes one moment, and the next it is the corners of mouth rising into a smile. Before the book has properly begun.

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

How can I number the worlds to which the eye gives me entry? - the world of light, of colour, of shape, of shadow: of mathematical precision in the snowflake, the ice formation, the quartz crystal, the patterns of stamen and petal: of rhythm in the fluid curve and plunging line of the mountain faces. Why some blocks of stone, hacked into violent and tortured shapes, should so profoundly tranquillise the mind I do not know. Perhaps the eye imposes its own rhythm on what is only a confusion: one has to look creatively to see this mass of rock as more than jag and pinnacle - as beauty.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain, p. 102.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It is when the body is keyed to its highest potential and controlled to a profound harmony deepening into something that resembles a trance, that I discover most nearly what it is to be. I have walked out of the body and into the mountain.

- Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland

#nan shepherd#quote#climber#moutaineer#pioneer#author#mountains#scotland#british#icon#femme#woman#history

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nan Shepherd, "The Weatherhouse" from "The Grampian Quartet."

"On all hands was a breaking: earth broken by the ploughshare, buds broken by the leaf. The smooth security of seed and egg was gone. Season most terrible in all the cycle of the year, time of the dread spring deities, Dionysus and Osiris and the risen Christ, gods of growth and of resurrection, whose worship has flowered in tragedy, superb and dark, in Prometheus and Oedipus, massacre and the stake. Life that comes again is hard: a jubilation and an agony."

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The inaccessibility of this loch is part of its power. Silence belongs to it. If jeeps find it out, or a funicular railway disfigures it, part of its meaning will be gone. The good of the greatest number is not here relevant. It is necessary to be sometimes exclusive, not on behalf of rank or wealth, but of those human qualities that can apprehend loneliness.

The presence of another person does not detract from, but enhances, the silence, if the other is the right sort of hill companion. The perfect hill companion is the one whose identity is for the time being merged in that of the mountains, as you feel your own to be. Then such speech as arises is part of a common life and cannot be alien. To “make conversation,” however, is ruinous, to speak may be superfluous... I have walked myself with brilliant young people whose talk, entertaining, witty and incessant, yet left me weary and dispirited, because the hill did not speak. This does not imply that the only good talk on a hill is about the hill. All sorts of themes may be lit up from within by contact with it, as they are by contact with another mind, and so discussion may be salted. Yet to listen is better than to speak.

...often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.”

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain. Robert Macfarlane's introduction to The Living Mountain is also gorgeous, link goes to an essay by them.

Photo of Loch Avon from Wikipedia.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elise Wortley spent June 2019 walking across the granite crags of the Scottish Highlands in the footsteps of writer and poet Nan Shepherd, who trekked through the Cairngorms in the 1940s. Photo by Emily Almond Barr

Wortley’s mother “presented her with a copy of The Living Mountain by writer and poet Nan Shepherd, who can now be seen on the Scottish five pound note. In the exemplar piece of nature writing, Shepherd describes her time trekking through the Cairngorms in the 1940s.”

Read more at Smithsonian Magazine

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

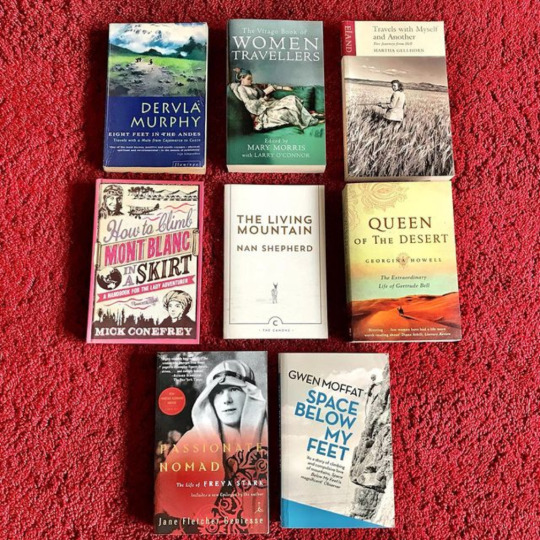

There She Goes: A Reading List on Women Adventurers

The women you'll find on top of the world.

https://longreads.com/2023/04/04/there-she-goes-a-reading-list-on-women-adventurers/

#Reading List#Travel#Unapologetic Women#Ada Blackjack#aeon#Alexandra David-Néel#Claire Turrell#David Guy#Elise Wortley#Emily Wit#Emma Garman#Harper's#History#Isabell Eberhardt#Kieran Mulvaney#longreads#Nan Shepherd#Outside#Rachel Kushner#Rahawa Haile#reading list#Rhian Sasseen#Robert Macfarlane#Simone de Beauvoir#Smithsonian Magazine#The Guardian#The New York Times Style Magazine#The Paris Review#Tricycle#women

1 note

·

View note

Text

while we're all doing screencap redraws, I had to try to capture the surreal sadness of Katya's dream sequence

#goncharov#katya goncharov#katya michailov#cybill shepherd#unreality#gonchposting#martin scorsese#matteo jwhj 0715#nan art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

"For the most appalling quality of water is its strength. I love its flash and gleam, its music, its pliancy and grace, its slap against my body; but I fear its strength. I fear it as my ancestors must have feared the natural forces that they worshipped. All the mysteries are in its movement. It slips out of holes in the earth like the ancient snake. I have seen its birth; and the more I gaze at that sure and unremitting surge of water at the very top of the mountain, the more I am baffled. We make it all so easy, any child in school can understand it – water rises in the hills, it flows and finds its own level, and man can’t live without it. But I don’t understand it. I cannot fathom its power."

— Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Ok so the other bookshelf hasn’t arrived yet but why don’t I start organising my books, it will be a fun activity and useful!”

What nobody tells you about said fun activity is that you have to make Choices about how to organise and it’s all very confusing

#I run into this problem EVERY DAMN TIME and I still hate it#I like my history books arranged a certain way so that tends to fuck up the Dewey Decimal or any other system I attempt to impose#Ok so for example what to do with primary historical sources like chronicles and collections of letters#Do I put them with the mediaeval literature section (some of which also functions as a primary historical source- i.e. the Brus)#Or do I put them with my history books (ordered by time period and country)#Or do I put them in their own tiny little category of their own- an extremely confusing and apparently irrational category#Or biographies of authors of which I only have two or three#Do I put them with my other history books or next to the literary works they wrote or on their own little section again#But since I only own maybe three it would be a weird little section just Aphra Behn James Herriot and Robert Henryson by themselves#And then what on earth do I do with C.S. Lewis' Allegory of Love#It's technically literary criticism but I don't own many books in that vein#Never mind the question of whether I should separate novels poetry and plays even if it breaks up an author's output#I don't really want to have to look for Violet Jacob or Oscar Wilde in two or three different places#And then sometimes a book doesn't fall into either of those three categories- should split Nan Shepherd's novels from the Living Mountain?#And what if it's a 'Collected Works' by an author which contains a bunch of non-fiction historical essays as well as a novel?#And don't even get me started on what I'm supposed to do with the Road to Wigan Pier#And then THEN we come to Wodehouse#Do I put Leave it to Psmith with the other Psmith books or in the midst of the Blandings books?#I want all the Psmith series together but what if some hypothetical person new to Wodehouse wandered in#And wanted to start either series at random- would they be confused at the introduction of Blandings too early?#Wouldn't they miss out on some of the best bits that come with knowing Blandings BEFORE Psmith?#I don't know who this hypothetical person is by the way#Nobody's wandering into my house and browsing my bookshelves except me so I don't know who I'm curating this for#I suppose in the back of my mind I always thought I would have kids who would one day be pulling randomly at the family bookshelves#And so that's why I've saved some of the fiction books but I'm not likely to have or even want children so what is the point#I'm not even the kind of person who regularly rereads my childhood favourites but somehow I can't bring myself to throw the kids' books out#It's an immense waste of space and a bit pretentious to have lots of books that nobody else will ever read#Honestly I'd have been happier running a public library or a bookshop I think or even having a flatmate to share books with#Ah well if this is a problem at least it's quite a nice one to have; first world problems only this evening I'll count my blessings#Earth & Stone

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What books are you currently reading? :)

hi anon!

I’ve been making my way through the earthsea series and I’m currently about to start book 3! I’ve also just started the living mountain by nan shepherd :)

#I’m into nature books these days#i finished the tombs of atuan the other day and tenar describing the mountains made me want to read nan shepherd’s book#asks

1 note

·

View note

Note

Scottish archaeologist who has worked in Turkey and beyond and had Big Thoughts about Annalee Newitz's book here - I love your non fiction recs! 👋 have you ever read The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd? That book is home to me ❤️

more and more im convinced that you guys are way cooler than me in every conceivable way. also no i haven't!!! but im adding to my tbr now!!

im currently reading that diane ackerman book i rec'ed plus peter godfrey-smith's "other minds: the octopus, the sea, and the deep origins of consciousness" and its very good but im having trouble finishing a single book this year. i just keep starting new ones.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I always enjoy posts about women explorers and travel. Can you recommend travel books written by women or about iconic women explorers? I think you would be better qualified than most armchair enthusiasts since you are well traveled, conversant in several languages, and a rugged mountaineer and hiker.

I don’t know about being qualified more than any anyone else. Traveling and exploring isn’t quite the same as hiking or mountaineering of course but I understand your sentiment.

I can say reading about pioneering women explorers and travelers has only inspired me to get off my arse and just go and do it. Perhaps it’s being raised overseas in several cultures and exploring those fabulous countries and regions that has always left with a travel itch to scratch.

Perhaps it’s the Norwegian or the military DNA on my Anglo-Scots side that I have a strong passion for hiking and mountaineering. These days if I do any serious hiking or mountaineering, I tag along with ex-army friends who are incredibly fit and accomplished climbers and hikers.

There are many books and each is a worthy recommendation but here are a few. It’s not an exhaustive list but a good start. I only hope they give you a sense of wanderlust as they continue to inspire me.

Eight Feet in the Andes: Travels with a Mule from Ecuador to Cuzco by Dervla Murphy (1983)

Dervla Murphy’s adventures are mind boggling, and she makes it sound so easy. Even in the mid ‘60s cycling alone through Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan was a bit dodge apart from the fact that there are mountains i.e. uphill cycling. This book is not her most famous one but it’s still worth a read. I put here because it brings memory of my time traveling with my father and elder brother and sister as a 10 year old in the Andes. In 1979 Dervla Murphy and her 9 year old daughter walked with their mule Juana from Cajamarca (northern Peru) to Cusco (far to the south) following as much as possible the Camino Real (the Inca Royal road) along the spine of the second highest mountain range in the world. It took them just over 3 months. Eight Feet in the Andes is a day by day journal of that incredible journey with all its splendour, risks and adventures. The Murphys travel light, most often camping in their small tent and not always sure where their next meal will come from. They endure blizzards, precipitous paths, bogs, heat, theft and find help when most needed and generous (if often taciturn) hospitality.

Reading the book years after I had done a similar trek I realised just how more luxurious our travel was in comparison to Dervla and her daughter who were more rustic in their trekking and hiking. That’s not say we weren’t hiking rough and hard (both my father and eldest brother did their stint in the army as officers) and so I had to keep up. But still, looking back I remember I had a comfortable bed to sleep in and I was well fed. I did have similar experiences of meeting amazing Andean people who are so different from urban Peruvians. The other thing that sticks out in this book is how prescient it is to realise that trekking 15-25 miles per day with the world's most uncomplaining 9-year old in tow would be considered child abuse today. I remember crying, getting blisters, and then toughing it out because I didn’t want to let the side down. So chapeau to Rachel Murphy for being so stoic and brave. As rough as the terrain was for them, there is undoubted warmth and humour in this book.

The Virago Book of Women Travellers, edited Mary Morris & Larry O’Connor (1994)

The Virago Book of Women Travellers captures 300 years of wanderlust. Some of the women are observers of the world in which they wander and others are more active. Often they are storytellers, weaving tales about the people they encounter. Whether it is curiosity about the world or escape from personal tragedy, these women approached their journeys with wit, intelligence, compassion and empathy for the lives of others. Because it’s a collection of women and their wanderlust, it’s not the kind of book you can read cover to cover or even in one sitting. It’s a good book to dip into as the mood pleases. As such it serves as a good introduction to how varied the experiences of women travellers and writers has been. I didn’t feel guilty about skipping certain parts because I found the writing turgid and boring, but that is the nature of an anthology, some you like and others less so.

In the introduction to this anthology, Mary Morris writes that “women’s literature from Austen to Woolf is by and large a literature about waiting, usually for love”. The writers selected here are the ones who didn’t wait: they set out, by boat or bicycle, camel or dugout canoe, and sought their own adventures. The collection covers some 300 years of travel writing, beginning with the extraordinary Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), who had just - scandalously - made the journey from London to Constantinople alone, and finishing with the American writer Leila Philip, an apprentice potter in early 1980s Japan, learning the art of harvesting rice by hand with a sickle. The range, in terms of location, style and mood, is vast.

So we meet independent travellers and those on the road with family, women on long epic journeys or more focussed trips, famous names and obscure, mountaineers and motorcyclists, aviators and anthropologists, those treading well-kept routes and brave pioneers, young women and old, but all intelligent and good writers. Many of the women were traveling alone during times when traveling wasn't very easy and certainly wasn't something many women did on their own, and they were traveling to places all over the world. The majority of the essays are about Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Many of the women travellers are familiar such as Dervla Murphy, Rebecca West, Beryl Markham - and the other usual suspects.

There were a few about traveling to colonial America and one about traveling to the wilds of Ohio written by Anthony Trollope's mother that was hilarious. An extract from Frances Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832) demonstrates a satirical eye her son clearly inherited: “She lived but a short distance from us, and I am sure intended to be a very good neighbour; but her violent intimacy made me dread to pass her door”. Some other pieces are les scathing and more lyrical: M. F. K. Fisher brings Dijon to life through the battling scents of the city’s famous mustard, gingerbread and the fragrant altar smoke billowing from a church door; Vita Sackville-West conjures the fading light of a picturesque Persian garden at dusk.

Many of the women faced sexism along the way and had to fight to go certain places and some even face sexual harassment on their travels. But mercifully these experiences are few and far between. There were a few many wonderful writers I stumbled across of whom I’d never heard – such as Flora Tristan, Frances Trollope, Isabelle Eberhardt (whose packed and tragically short life is worth reading up on), and many others. Maud Parrish writes exhilaratingly about adventures in Yukon and Alaska, the intriguing Mrs F D Bridges (about whom we know little as she travelled in the shadow of her husband) describes nineteenth century Mormonism compellingly. Emily Hahn, I did know about as her writings I was familiar with when I was growing up in Shanghai. Hahn writes vividly about her opium addiction in China (one of a few women to focus heavily on addictions).

However uneven anthologies can be, they still can serve as a good starting place to discover further a favourite writer and traveler. And if it can do that then an anthology will have served its purpose.

Travels With Myself and Another: Five Journeys from Hell by Martha Gellhorn (1978)

Although Martha Gellhorn was principally a war correspondent but seems to have travelled widely for most of her life. Her book was originally subtitled Five Journeys from Hell, which provides a not very subtle clue about her travel experiences. It describes her journeys in China with the unnamed other (1941), the Caribbean (1942), Africa (1962), Russia (1972) and Israel (1971). She says that this is not a proper travel book – ‘I rarely read travel books myself. I prefer to travel’. And it’s clear that she spent most of her life travelling, with an impressive list of places she has visited. It’s a difficult book to categorise, and that’s perhaps also true of its author. She clearly had a strong spirit of adventure, and as someone who covered every major conflict from the Spanish Civil War to the American invasion of Panama in 1989, she cannot have lacked courage or determination.

The writing is excellent, with lots of very funny, self-deprecating, black humour, and witty observations about the pitfalls of travelling generally. Many things infuriated Gellhorn - injustice, cruelty, stupidity - but on a personal level, nothing made her more incensed than having her name linked with that of the man she was married for less than five of her almost ninety years, Ernest Hemingway. Although Travels with Myself and Another is subtitled as a memoir, the most famous of her three husbands appears in just one essay under the initials of U.C. (Unwilling Companion), probably only because he provides extensive comic relief for a writer “who cherishes...disasters” and is immensely fond of black humour.

The only trouble is that her accounts of her journeys focus largely on her feelings of boredom, fear, exhaustion, hunger, anger and so on, with rare uplifting moments between. She also seems to have little fellow feeling for the people she comes across, and there are flashes of racism and intolerance. As her companion in China says, ‘Martha loves humanity but can’t stand people’. Still Gellhorn relishes mishaps in her journeys because that is where the story lies--and since her journeys are invariably far off the map, mishaps are always there, waiting for her acerbic descriptions.

Of all the travels that she has chosen to relive, her journey to China in 1941 is easily the most hair-raising and hysterically funny. As someone who grew up in Shanghai as a girl, China in 1941 is still firmly etched into Chinese history and culture. The legacy of the Japanese war - the sheer brutality of it which many Europeans have blithely ignored - remains a ghost in the collective memory of the Chinese and is a regular staple as a setting for its many television soap operas.

Anyway, in this book, Gellhorn is determined to witness the Sino-Japanese War first-hand shortly after Japan joins Italy and Germany in the Axis. “All I had to do is get to China,” she says blithely, and as part of her preparations for this odyssey she persuades U.C. (Ernest Hemingway) to go with her. Embarking from San Francisco to Honolulu by ship, a voyage that “lasted roughly forever,” Gellhorn and U.C. then fly from Hawaii to Hong Kong, “all day in roomy comfort”, landing at an island where passengers spend the night before arriving in Hong Kong. “Air travel,” she says, “was not always disgusting.”

As a war correspondent for Collier’s, Gellhorn insists upon getting as close to the war as she can. Traveling by plane, truck, boat, and “awful little horses”, she and U.C. find the troops of the Chinese Army and their hard-drinking generals (who almost vanquish U.C. in their alcoholic prowess), Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang (“who,” Gellhorn fumes, “ was charming to U.C. and civil to me”), and, through a cloak-and-dagger encounter in a Chungking market, Chou Enlai (“this entrancing man,” Gellhorn confesses, “the one really good man we’d met in China”). Although she and U.C. barely escape cholera, hypothermia, food poisoning, and the hazards of drinking snake wine, by the end of their journey Gellhorn contracts a vicious case of “China Rot,” an ailment resembling athlete’s foot that’s highly contagious. U.C.’s commiseration is heartwarming: “Honest to God, M., you brought this on yourself. I told you not to wash.”

On their last night, hot and steaming in the humidity of Rangoon, Gellhorn is overwhelmed with gratitude that U.C. has stuck with her through “a season in hell.” She reaches out, touches his shoulder, and murmurs her thanks, “while he wrenched away, shouting “Take your filthy dirty hands off me!” “We looked at each other, laughing in our separate pools of sweat.” “The real life of the East is agony to watch and horror to share,” Gellhorn wrote somewhat melodramatically to her mother. Years later, she concludes “I was right about one thing; in the Orient a world ended.” From Gellhorn’s sharp-eyed and sharp-tongued point of view, that ending was nothing to mourn. Gellhorn is captivating, bold, reckless, romantic, and deeply, powerfully, and hypnotically inspired to help the world despite her own personal flaws.

How to Climb Mont Blanc in a Skirt: A Handbook for the Lady Adventurer by Mick Conefrey (2011)

I had second thoughts about including this book but it is easily the most readable and therefore the most accessible introduction to women explorers and travellers….and yet it’s written by a man. Hmmm. Bear with me. I was given this book as a birthday gift and dutifully I read it and even I was surprised that there were some women explorers I hadn’t known about in amongst the usual suspects of Freya Stark, Gertrude Bell and Jeanne de Clisson. The book overviews female explorers and adventurers from the 1800’s through the 2000’s. It is a collection of short anecdotes, ranging between one paragraph and three pages in length.

There aren’t traditional chapters, but the book is sectioned off by different questions. The arrangement of the book makes reading straightforward and simple. I suppose there is no correct answer to questions like “why do women adventure?” and “how do women adventure differently to men?”. Conefrey is visibly careful not to generalise. However, he does compare them a lot. Some women appear only in tandem with their husbands, some feel like an offshoot of their husband and there’s an entire chapter comparing women adventurers to either their male expedition partner or the man who did the most similar expedition or adventure, usually before the woman did it. I did find myself wondering if we needed quite so many men in a book that’s supposed to be exclusively about women.

The majority of the women who appear were doing their adventures a couple of centuries ago, when vast swathes of the world were mysterious and unknown, when it was acceptable to hire or occasionally coerce fifty locals to carry your luggage or occasionally to carry you in a bath chair, when people routinely carried an entire arsenal with them, and yes, when women were doing this kind of adventuring in all sorts of skirts.

These are not then full biographies. Some names appear again and again. Freya Stark, Gertrude Bell, Mary Kingsley as well as other ones like Rosita Forbes, Mary Hall, Ella Maillart, Annie Smith Peck, and Jeanne de Clisson. Clearly bigger stories to tell about them. They went off to places women just didn’t go to in those days and did things women just didn’t do. But the book does serve as a jumping board to explore further any explorer that captures your attention. In the end it’s something to read on an idle rainy day and can be read in bedtime-reading sized chunks. Rather than a deep trek, it’s the equivalent of a well written jog through a brief explanation of the journeys and personalities of some rather interesting women.

The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland by Nan Shepherd (1977)

If you’re Scottish then you have no excuse not knowing who Nan Shepherd was - her face has been on the Scottish five pound note. As strange as it sounds, being Anglo-Scots on my father’s side, I first heard her name when living on the other side of the world. Only when I came home to see my family clan we would walk in the Cairngorms and her spirit would be invoked with reverence and awe. For a long time in Scottish arts and letters she was known only as a minor writer of the early 20th century Scottish Renaissance. Between 1928 and 1935 she published three modernist novels – The Quarry Wood being superlative - and one book of poetry. From then until her death in 1981, she published only one more, The Living Mountain. It was written during the latter years of the World War Two but, following advice of novelist Neil Gunn, left in a drawer. No publisher would take a punt on such an unusual book, he argued. In 1977, it was unearthed and Aberdeen University Press published it. This prose-poem about the Cairngorms quickly became a cult classic among wanderers and mountaineers, as important as anything written by WH Murray.

In this masterpiece of nature writing, Nan Shepherd describes her journeys into the Cairngorm mountains of Scotland. There she encounters a world that can be breathtakingly beautiful at times and shockingly harsh at others. Her intense, poetic prose explores and records the rocks, rivers, creatures and hidden aspects of this remarkable landscape. Reading it has become a rite of passage for anyone wishing to understand the Scottish mountains, the literary equivalent of a hillwalker spending the night under the Shelter Stone at the head of Loch Avon. Both pursuits are likely to keep you up all night. From its first sentence, "Summer on the high plateau can be delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge”. The Living Mountain draws you in with the feyness of its vision, the lucidity of its prose and Shepherd’s refreshing philosophy that mountains are more than peaks to be scaled. In writing the book, her aim was to uncover the "essential nature" of the mountains, and understand her place in them.

Nature writing these days is as much about the person as the place. Refreshingly, Shepherd is not there as a personality, rather a human presence in the landscape, complete with roving eye and senses wide open. She understood nature’s ultimate indifference (it doesn’t care who you are), yet also how much she was a part of it. She had a keen sense of ecology, an understanding that to "deeply" know a place was to know something of the whole world. Her chapters, for example, move through every element of the mountains, from water to earth, on to golden eagles and down to the tiniest mountain flowers, like the genista or birdsfoot trefoil. Robert McFarlane, one of my favourite writers today, has argued that is why she is a truly universal writer.

Nan Shepherd spent a lifetime in search of the ‘essential nature’ of the Cairngorms; her quest led her to write this classic meditation on the magnificence of mountains, and on our imaginative relationship with the wild world around us. It is a very short book at around 100 pages but it can feel like a thousand when you immerse yourself in the beauty of her prose and wisdom. Bonus tip: the edition with has Robert Macfarlane’s introduction and an afterword written by Jeanette Winterson. What I love about this book is that you don’t have to travel to exotic far flung places to appreciate mountains or nature in general. For most of us it can be in easy reach from our door steps.

Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations by Georgina Howell (2007)

If you follow my blog then you know I have made a lot of posts about one of my heroines, Gertrude Bell. I’m not going to rehash all that I’ve posted here. Just type in ‘gertrude bell’ into the search box.

Gertrude Bell is commonly referred to as ‘the female Lawrence of Arabia’ and that really explains in a nutshell how she’s been screwed over by history. If we could be more fair minded and reasonable, T.E. Lawrence would be called ‘the male Gertrude Bell’ and Gertrude would have the four-hour Oscar award-winning biopic that everyone would watch at Christmas time. But always no, and because of this, T.E. Lawrence is a household name and Gertrude Bell is a footnote in his story. To this day it ticks me off that Gertrude Bell gets no mention in David Lean’s magisterial Lawrence of Arabia. It’s one of my favourite films of all time but it grates that she didn’t even feature in one scene.

Suffice it to say, Gertrude Bell was one of those rare figures for whom the expression “larger than life” is too small. In an age when women were expected to stay close to husband and hearth, she explored uncharted deserts and ascended previously unclimbed mountains…in Edwardian skirts. Bell was full of firsts. She began marching to a different drummer at Oxford University, which was scarcely comfortable with women in the 1880s. A professor asked Bell and the few other female students for their reaction to his lecture. “Green eyes flashing, Gertrude retorted loudly: `I don’t think we learned anything new today. I don’t think you added anything to what you wrote in your book,'” Howell says. She was the first woman to get a First in modern history at Oxford.

As a highly respected archaeologist, she made important archaeological discoveries in an era when the methodology involved bribing local nabobs and packing a gun lest the natives not be friendly. A linguistic polymath, she translated the love lyrics of medieval Persian poet Hafiz. She was friends and colleague of T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). She was every inch - and more - her colleague and friend’s equal in intellect and action. Bell was to achieve seniority in the British military intelligence and diplomatic service. The in-depth knowledge and contacts she acquired through long and arduous travels in then Greater Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and Arabia, shaped British imperial policy-making. More successful than Lawrence, she shaped the making of the modern east after the First World War. Indeed she ran Iraq when Britain, which won World War I, cobbled together that country out of bits and pieces of the Turkish Empire, which lost the war.

A daughter of the English industrial class, she fell in love with the parched landscapes of the Middle East and went native, albeit loading her caravans with fine china and formal gowns. She so mastered the language and culture of the Bedouins that members of the Beni Sakhr, a tribe not well-disposed toward outsiders, saluted her as one of their own. “`Mashallah! Bint Arab,’ they declared - `As God has willed it: a daughter of the desert,'” Georgina Howell writes in Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations.

I could easily point you to her own book, ‘Letters of Gertrude Bell’ which are cherished part of my library. But that might not be the best entry point into the extraordinary life of Gertrude Bell. To date Georgina Howell has probably done the best biography of this amazing woman - Janet Wallach’s Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell is another one but Howell’s is better. Bell was constantly writing letters about her adventures, and Howell quotes them extensively throughout the book - which makes Bell much more dynamic. The scope of Howell’s book is also wider - while Wallach’s book focused mainly on Bell’s work in the Middle East later in her life, Howell seems to be trying to give equal attention to all the phases of Bell’s life

So my reservations about Howell’s book should be taken with a pinch of salt. Howell’s book certainly delves into the primary sources more head on. It’s a good book but the pity is that Howell’s literary skills are not always up to those of her subject. Yet such was likely to be the case no matter who her biographer might have been.

Howell doesn’t help herself by fretting about marginal issues like why Bell wasn’t more of a feminist. Honorary secretary of the Anti-Suffrage League, Bell organised a massive petition drive, which netted 250,000 signatures, against giving women the vote. Since Bell set so many firsts for her sex, why shouldn’t she also have been the Emily Pankhurst of her era?

Early on, Howell’s narrative gets bogged down in a recitation of Bell’s ancestors and social-set contemporaries. Many have hyphenated names bound to be lost on readers without ears trained since childhood for such aristocratic nuances. The great love of her life was Maj. Charles Hotham Montagu Doughty-Wylie of the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Friends called him Dick. When they met, he was married and she was a virgin,“For Gertrude, intrepid as she was, sex was the final frontier,” Howell writes. In her mid-40s, Bell couldn’t bring herself to cross that border with her beloved, though furtive attempts were made. He went off to serve and die in Britain’s ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, carrying only a walking stick into battle against Turkish gunners. Howell also doesn’t really address why Bell would want to take her own life. Also missing from the Howell biography is Bell’s early disdainful attitude for the Middle Eastern locals she encounters.

Overall Howell’s obvious fondness for her subject hampers her ability to construct a more objective and nuanced portrait of Gertrude Bell. Readers are, however, indebted to Howell for her decision to allow Bell to speak for herself by including quotations from many of Bell’s letters. Summing up the state of Iraqi affairs in spring 1920, Bell admits that events on the ground have overwhelmed British intentions. “We are now in the middle of a full-blown Jihad . . . Which means that it’s no longer a question of reason . . . The credit of European civilization is gone . . . How can we, who have managed our own affairs so badly, claim to teach others to manage theirs better?"

Passionate Nomad: The Life of Freya Stark by Jane Fletcher Geniesse (1999)

Like Gertrude Bell, I’ve posted a lot on Freya Stark (1893-1993). Again, one can search my blog for her posts. It has to be said that Freya Stark, much like Gertrude Bell, was not the most cuddliest women one could warm to. Both could be demanding and dominant with others by having an iron will determination that their way was best. And both were friendless with other women whilst also having the most tragic luck in their romantic lives. Needless to say both were fascinatingly complex and complicated women of renown. Ex-New York Times writer, Jean Fletcher Geniesse, makes a fine stab at giving us a biography worthy of Stark’s amazing life, warts and all. Her book is excellent and offers a psychologically astute chronicle of the adventurous life of this intrepid traveler of the Middle East.

Freya Stark lived a truly remarkable life. Born in Paris to an English father and an Italian mother of Polish/German descent, she was raised in Italy, chafing under the impositions of her vain, rather selfish mother who had left her husband to his bourgeois English life. Freya was largely self-taught, learning Arabic and Persian for fun, always fascinated by the Orient. Which was just as well as she had a miserable family life. her overbearing mother had left Freya’s father for an Italian count, who would later marry Freya’s sister. Geniesse describes this suffocating domestic atmosphere in vivid detail, arguing that it helped trigger Stark’s desire for a life of picturesque adventure.

At age 13, Stark was disfigured in a horrible industrial factory accident. Stark began studying Arabic in London and in her mid-30s. By 1927 she was on a ship bound for Lebanon. Stark immediately fell in love with the Middle East, becoming “fascinated by the ancient hatreds among” the region’s different tribes and religious sects. As an Arabist proud of her British heritage, Stark was in the difficult position of justifying British colonialism to the freedom-loving natives. During WWII, she worked for Britain’s Ministry of Information in the role of propagandist. She collaborated with native groups in Egypt and Iraq, drumming up support for the Allied powers. She quickly found she was very good at her double vocation, as intrepid explorer and eloquent letter-writer, then pursued and built on these skills through two glorious decades, achieving stellar literary fame, and moved effortlessly in the company of the high and mighty.

Stark would travel on foot, by donkey or camel into some of the most inaccessible regions of the Middle East, places that scarcely saw Westerners, let alone single Western women. She would infiltrate mosques and harems, climb mountains, uncover ruined cities, live amongst the simple people of the deserts, sleeping under the stars or in Bedouin tents. When Freya traveled, she liked to stay where the local people stayed, and ate their food, drank their water, and talked to them. She learned many different languages and dialects throughout her travels.

She was a mountain climber, scaling the Matterhorn, and other peaks. Since she didn’t take any precautions with food or water, she was constantly ill, and she survived many different diseases: typhoid, dysentery, and malaria, to name a few. Contrary to what many might think she wasn’t the best organised of travellers. She would often plan haphazardly and rely on her skill and luck to be at the place she wanted to be.

She wrote numerous travel books, becoming one of the foremost experts on Islamic history and peoples. Her early books on Yemen and the ancient cult of the Assassins won her plaudits from the public and the Royal Geographic Society. Indeed the published accounts of her travels quickly became the most popular reads of the day, not only for the thrilling adventures she undertook but also for her incredible writing. Freya Stark kept meticulous notes about her travels and the lands she explored, and these were instrumental in updating the maps used by the Royal Geographic Society and the British Government. Freya was also plagued by the same concerns as her contemporary, Gertrude Bell, and wrestled with contradictory feelings as a proud British citizen regarding the government’s policies toward a region she admired and even loved.

Despite her growing fame, her personal life remained unfulfilling. She fell in love with a British colonial officer who “brusquely rejected” her. After the war, at the age of 54, she married a minor colonial official who, after their wedding, revealed he was a homosexual (or rather, she could no longer pretend not to see it). Because of her factory accident as a child, she had a desire for love and to be beautiful, which lead to intense jealousy of younger and prettier women.

It’s a captivating book about one of the great English-language interpreters of the Middle East, and one in which draws on the huge and expressive bulk of Freya Stark's letters to paint a personal and professional portrait of rare accomplishment. This biography is no hagiography, exposing Freya warts and all - her bravery, independence, sense of adventure and fun is all laid out alongside her tendency to imperiousness, her habit of using people who could be helpful to her, her neediness and desperate longing to be loved. Geniesse successfully explores Stark’s fascinating psychological makeup, her mixture of insecurity and total fearlessness. Throughout, the author skilfully details the people, places, and ideas that shaped her subject’s life. Although Stark could be amazingly kind to Iraqi Bedouins or Druze tribesmen, she took the smallest slights to her dignity as personal affronts.

Freya Stark comes across as a fascinating person, a woman who never let convention stand in the way of what she wanted, a true traveller keenly interested in everyone she came across, but somehow a woman who, whilst comfortable in any kind of surrounding, was never truly comfortable in herself. In all, the evocation of a world only sixty years back but so removed from ours in its rhythms and its concerns - with the intense letter writing, the extended visits to country houses, and the imperatives of empire - will keep the attention of the reader.

Overall it’s worthwhile, stylish, and thoroughly researched biography of a fascinatingly complex, often exasperating woman. Dame Freya Stark started traveling at the age of 22 and didn't quit until she was in her 90s - perhaps no finer example of wanderlust.

Space Below My Feet by Gwen Moffat (1961)

Gwen Moffat is little known amongst the general population but to the wider mountaineering community she has a rightful place as one of Britain’s foremost female climber in the post-war world. She has the distinction of being Britain’s first female professional mountain guide and also a prolific writer of over 30 books. This entertaining memoir roughly covers the years 1945-1955, when Gwen was in her twenties. Gwen Moffat is unorthodox, uncompromising, honest, charming, and a born rebel. Moffat was an Army driver in the Auxiliary Territorial Service, stationed in North Wales after the end of the Second World War, when she met a climber who introduced her to climbing in the Welsh Hills and a bohemian lifestyle. As a conscientious objector she found the army was not her cup of tea. She especially found army life too stiff and constraining the more she climbed around Wales, where she was stationed.

From that moment her entire life unfolds against a background of mountains, and she takes us with her. We follow Gwen in her hobo existence in a shack in Cornwall, in cottages in Wales and Scotland, on a fishing boat or when the money ran out, she worked as a forester, went winkle-picking on the Isle of Skye, acted as the helmsman of a schooner, and did a stint as an artist's model. To keep alive and support her little daughter in the meantime she has followed a number of other trades, all with a mountain background except for a job in a theatre: running a Youth Hostel in Wales, driving a travelling store on lonely roads in the Scottish Highlands, acting as a maid of all work in a hotel in the British Lakes.

There is no deeper truth for Gwen, just a frugal, bohemian life singularly devoted to climbing crags and mountains. Most of the action is situated in Wales and Scotland and it helps to have a rough idea of the topography as the narrative is littered with exotic toponyms referring to the innumerable cliffs, buttresses and arêtes climbed by Moffat. A few chapters deal with her climbing adventures in the Alps (Chamonix, Zermatt, Dolomites).

She is a skilled writer as she is a climber. Anyone reading her will experience a novice’s thrills during her first climbs, bare-footed, on the Welsh slabs; we go through hairbreadth escapes, and the climbing goes on: difficult, severe, very severe. When we finally part from her and her husband on the summit of the Breithorn after 12 hours on the Younggrat, she is a fully qualified guide. From time to time we are taken for exciting adventures on the Continent, to Chamonix, Zermatt and the Dolomites. To this reader however, the most fascinating parts of the book are the descriptions of the mountains Gwen Moffat knows best, the Welsh and Scottish Hills, and the enchanting island of Skye. People of all sorts come and go in the pages, but they are secondary to the main theme of a human being and her endeavours in high places.

The great attraction of Space below my Feet is the writer’s power to conjure up mountain scenes, moods and weather and her own reactions to them. This is an intensely personal book and may be frowned on by those who like their mountains to be viewed objectively. Mountains are her passion: through them she found freedom and her true self, and she feels she can best express herself climbing among them. The objective mountain worshipper is often personally inarticulate; he or she dwindles into insignificance beside the beloved object and is rather guilt-stricken about obtruding their own feelings in descriptions of climbs. Gwen Moffat though can articulate the unspoken onto the page. It’s her searing honesty and vividness as a writer that makes this book well worth reading.

Thanks for your question

#ask#question#explorers#exploration#travel#travellers#women#femme#nan shepherd#martha gellhorn#gertrude bell#freya stark#gwen moffat#dervla murphy#books#reading#wanderlust#mountaineering#hiking#trekking#personal

33 notes

·

View notes